Abstract

Background

Intraamniotic infection is associated with maternal morbidity and neonatal sepsis, pneumonia and death. Although antibiotic treatment is accepted as the standard of care, few studies have been conducted to examine the effectiveness of different antibiotic regimens for this infection and whether to administer antibiotics intrapartum or postpartum.

Objectives

To study the effects of different maternal antibiotic regimens for intraamniotic infection on maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (May 2002) and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2002). We updated the search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register on 30 April 2010 and added the results to the awaiting classification section of the review.

Selection criteria

Trials where there was a randomized comparison of different antibiotic regimens to treat women with a diagnosis of intraamniotic infection were included. The primary outcome was perinatal morbidity.

Data collection and analysis

Data were extracted from each publication independently by the authors.

Main results

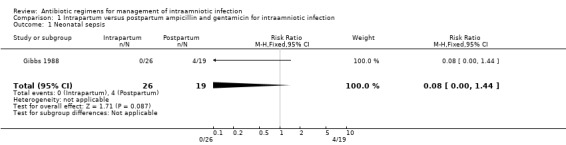

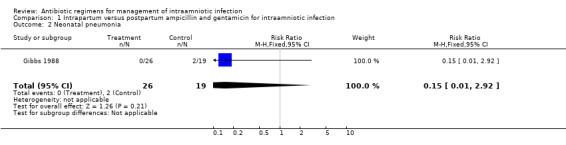

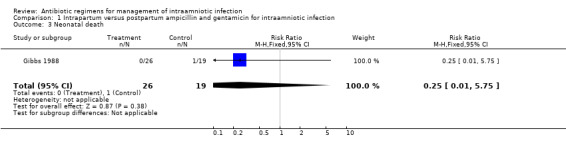

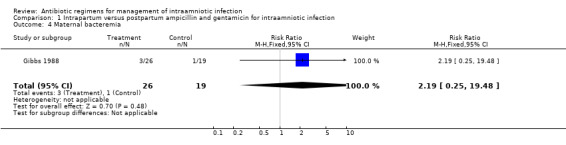

Two eligible trials (181 women) were included in this review. No trials were identified that compared antibiotic treatment with no treatment. Intrapartum treatment with antibiotics for intraamniotic infection was associated with a reduction in neonatal sepsis (relative risk (RR) 0.08; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.00, 1.44) and pneumonia (RR 0.15; CI 0.01, 2.92) compared with treatment given immediately postpartum, but these results did not reach statistical significance (number of women studied = 45). There was no difference in the incidence of maternal bacteremia (RR 2.19; CI 0.25, 19.48). There was no difference in the outcomes of neonatal sepsis (RR 2.16; CI 0.20, 23.21) or neonatal death (RR 0.72; CI 0.12, 4.16) between a regimen with and without anaerobic activity (number of women studied = 133). There was a trend towards a decrease in the incidence of post‐partum endometritis in women who received treatment with ampicillin, gentamicin and clindamycin compared with ampicillin and gentamicin alone, but this did not reach statistical significance (RR 0.54; CI 0.19, 1.49).

Authors' conclusions

The conclusions that can be drawn from this meta‐analysis are limited due to the small number of studies. For none of the outcomes was a statistically significant difference seen between the different interventions. Current consensus is for the intrapartum administration of antibiotics when the diagnosis of intraamniotic infection is made; however, the results of this review neither support nor refute this although there was a trend towards improved neonatal outcomes when antibiotics were administered intrapartum. No recommendations can be made on the most appropriate antimicrobial regimen to choose to treat intraamniotic infection.

[Note: The six citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

Plain language summary

Antibiotic regimens for management of intraamniotic infection

Antibiotics are used to prevent life‐threatening complications for mother and baby when the amniotic fluid is infected, but it is not known which antibiotic is best.

Amniotic fluid is the 'water' surrounding the baby inside the womb. If this fluid becomes infected, it can be life‐threatening for the mother and baby, and the baby should be born within 12 hours. Infection can come from bacteria entering the womb from the vagina, or from a medical procedure that penetrates the membranes ('bag' around baby and waters). Antibiotics reduce the risk of dangerous complications for both mother and baby. The review found there is not enough evidence from trials to show which antibiotic is best or whether it should be given before or after the baby is born.

Background

Clinically evident intraamniotic infection (IAI) occurs in approximately one per cent of pregnancies and is potentially a serious infectious complication, leading to increased maternal and infant morbidity and mortality (Sweet 1985). Several alternative terms for intraamniotic infection are in widespread use and include chorioamnionitis, amnionitis, uterine infection and amniotic fluid infection. Intraamniotic infection occurs when there is bacterial infection of the uterine cavity and amniotic fluid and is usually a result of ascending infection from the vagina to the uterine cavity. Infection is often polymicrobial. The principal pathogens include Escherichia coli, Bacteroides species, Group B streptococci and anaerobic streptococci. Occasionally infection is due to hematogenous dissemination of bacteria such as Listeria monocytogenes (Schuchat 1992). A third mechanism for the development of intraamniotic infection is the introduction of bacteria during an invasive procedure, for example, amniocentesis, intrauterine fetal blood transfusion, and cervical cerclage (Sweet 1985). Several risk factors have been identified for the development of intrapartum intraamniotic infection. Only the duration of labor, duration of membrane rupture, use of internal fetal monitoring devices and number of vaginal examinations are independently associated with the development of intraamniotic infection (Newton 1989; Soper 1989).

The usual presenting clinical manifestations of intraamniotic infection include fever associated with maternal and fetal tachycardia. Uterine tenderness and purulent amniotic fluid may be present also but are usually late manifestations. The membranes may or may not be intact and labor may or may not be present (Duff 1993).

There is a significant risk of both maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with intraamniotic infection. In addition to the initiation of labor, intraamniotic infection may lead to postpartum endometritis and also more serious infectious sequelae such as septic shock, adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and acute renal failure (Westover 1995). Infected fetuses can rapidly decompensate during labor. They may be born with fulminant sepsis and subsequently die in the neonatal period or be developmentally delayed. Infants exposed to intrauterine infection can present with neonatal encephalopathy and may be at an increased risk of cerebral palsy (Hagberg 2002). Delivery is indicated once a diagnosis of intraamniotic infection is established. Few data exist, however, to indicate the optimal time frame in which to effect delivery. From the available evidence, a diagnosis to delivery interval of up to twelve hours is not associated with increased neonatal morbidity (Gibbs 1980; Hauth 1985). In both of these studies, maternal parenteral antibiotic administration was commenced at diagnosis. Whether to begin parenteral antibiotic administration immediately after making the diagnosis or after delivery has been controversial. While immediate administration of antibiotics may limit maternal sepsis, intrapartum antibiotic therapy could obscure the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis and affect the management of the infant. Side effects associated with antibiotic therapy include allergic reactions, renal toxicity, antibiotic‐associated diarrhea and the consequences of the development of antimicrobial resistance. A variety of regimens, effective against the most common organisms, have been used to treat intraamniotic infection on an empirical basis. Usually treatment is with a penicillin and gentamicin with or without the addition of clindamycin, but there is no consensus on the most appropriate regimen (Sweet 1985).

Objectives

To study the effects of different maternal antibiotic regimens for intraamniotic infection on maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All trials were considered where the intention was to allocate participants randomly to one of at least two different management strategies to treat intraamniotic infection.

Types of participants

Women who were diagnosed with intraamniotic infection by the presence of fever plus at least one of: maternal tachycardia, fetal tachycardia, uterine tenderness or purulent amniotic fluid. No gestational age limit was imposed. Women were or were not in labor and the membranes were or were not intact.

Types of interventions

Trials were considered if they compared any antibiotic treatment versus no treatment, compared at least two different antibiotic drug regimens or where there was a comparison of timing of antibiotic administration (intrapartum or postpartum).

Types of outcome measures

Trials were considered if any one of the following clinical outcomes was reported, however they were defined by the authors: (i) endometritis (ii) febrile morbidity (iii) other serious infectious complication (wound infection, urinary tract infection, septic shock, adult respiratory distress syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation, renal failure) (iv) neonatal sepsis (v) stillbirth and neonatal death (vi) other serious neonatal infectious complication (pneumonia, respiratory distress syndrome, positive blood cultures and meningitis). In addition data were collected (where available) on adverse events of treatment (e.g. allergic reactions, antibiotic‐associated diarrhea, development of bacterial resistance).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (May 2002). We updated this search on 30 April 2010 and added the results to Studies awaiting classification.

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

In addition, we searched the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2002). The terms chorioamnionitis, amnionitis, infection, labor and intrapartum were used.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

All potential trials were selected for eligibility according to the criteria specified in the protocol and data were extracted from each publication by two reviewers. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion. In addition to the main outcome measures listed above, information on the setting of the study (country, type of population, socioeconomic status), a description of the antibiotic regimen used (drug, dose, frequency and timing), characteristics of the pregnancies (gestational age, labor, membrane status) and definitions of outcome as well as intraamniotic infection (if provided) was collected. Trials were assessed for methodological quality using the Cochrane criteria of adequacy of allocation concealment: adequate (A), unclear (B), inadequate (C), or that allocation concealment was not used (D). Subgroup analyses to examine: (1) the effect of high quality trials (defined as adequate allocation concealment), and (2) the effect of infection occurring at term versus preterm on outcomes was performed. Information on blinding of outcome assessment and loss to follow‐up was collected. Where data were available, an intent to treat analysis was performed. The main comparison of treatment schemes was not stratified according to gestational age, membrane status, or presence and duration of labor. Separate comparisons of different antimicrobial regimens were made. Summary relative risks were calculated using a fixed effects model (or a random effects model if statistically significant heterogeneity among trials was observed).

Results

Description of studies

Fifteen trials, published between 1956 and 1998, were examined for inclusion in the review but thirteen were excluded because they were not randomized controlled trials or did not fit the selection criteria specified in the review (for a detailed description of the reasons for exclusion, see table of 'Characteristics of excluded studies'). Both trials included in the review (Gibbs 1988; Maberry 1991) were conducted in the United States. The study by Gibbs 1988 enrolled 48 women; 133 women were included in the study by Maberry 1991. Criteria listed to define the presence of intraamniotic infection were consistent. The antimicrobial agents used in the trials included ampicillin and gentamicin with the addition of clindamycin to one of the arms in the trial by Maberry 1991. All infants in the study by Gibbs 1988 received ampicillin and gentamicin for at least 72 hours after delivery; the majority of the infants in the study from Maberry 1991received ampicillin and gentamicin for at least 48 hours after delivery. For a detailed description of studies see:Characteristics of included studies. (Five reports from an updated search in April 2010 have been added to Studies awaiting classification.)

Risk of bias in included studies

In the included study by Gibbs 1988, randomization by sealed envelopes and lack of blinding weaken the study design but endpoints were well defined. The investigators and the Safety Committee agreed to stop this study after 48 patients had been enrolled based on the preliminary results; a sample size of 92 patients had been planned. Specific maternal and infant side‐effects of therapy were not sought. Follow‐up for infant infectious complications in the neonatal period appeared to be complete. Three of 22 women randomized to postpartum treatment were excluded from the analysis because of protocol violations: two women received intrapartum antibiotics and neonatal blood cultures were not collected in a third. An intent to treat analysis was not performed. In the included study by Maberry 1991, randomization was by a table of random numbers. There is no mention as to whether the study was blinded but again, endpoints were well‐defined. All women enrolled were included in the analysis.

Effects of interventions

No trials were identified that compared antibiotic treatment with no treatment. Intrapartum treatment with antibiotics for intraamniotic infection was associated with a reduction in neonatal sepsis (relative risk (RR) 0.08; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.00,1.44) and pneumonia (RR 0.15; CI 0.01, 2.92) compared with treatment given immediately postpartum, but these results did not reach statistical significance (number of women studied = 45). One neonatal death occurred in an infant whose mother received antibiotics post‐partum. There was no difference in the incidence of maternal bacteremia (RR 2.19; CI 0.25, 19.48).

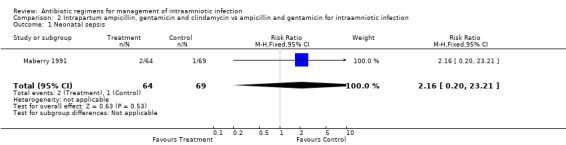

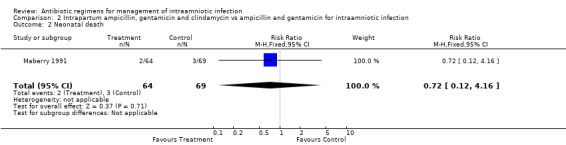

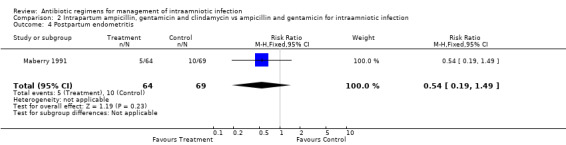

There was no evidence to support the use of a more broad‐spectrum regimen than ampicillin and gentamicin for the treatment of intraamniotic infection. There was no difference in the outcomes of neonatal sepsis (RR 2.16; CI 0.20, 23.21) or neonatal death (RR 0.72; CI 0.12, 4.16) between a regimen with and without anaerobic activity (number of women studied = 133). There was a trend towards a decrease in the incidence of post‐partum endometritis in women who received treatment with ampicillin, gentamicin and clindamycin compared with ampicillin and gentamicin alone, but this result did not reach statistical significance (RR 0.54; CI 0.19, 1.49).

Discussion

The conclusions that can be drawn from this meta‐analysis are limited due to the small number of studies and the early discontinuation of enrollment in one of them. For none of the outcomes was a statistically significant difference seen bbetweenthe different interventions. Current consensus within the clinical community is for the intrapartum administration of antibiotics when the diagnosis of intraamniotic infection is made; a combination of ampicillin and gentamicin is often recommended. The results of this review, however, neither supports nor confirms this approach although the trend in improved neonatal outcomes was when antibiotics were administered intrapartum. No recommendations can be made on the most appropriate antimicrobial regimen to choose to treat intraamniotic infection. The quality of evidence supporting the current approach is poor and current practice is not based on evidence from well‐designed cclinicaltrials, but rather on expert opinion, descriptive studies and clinical experience.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The results of this review neither support nor refute the current approach to the clinical management of intraamniotic infections.

Implications for research.

Future research should be directed at recognizing the risk factors for the development of intraamniotic infection and clarifying what interventions and preventative strategies can be effective in reducing the incidence of infection. Although the trend was towards improved neonatal outcomes when antibiotics were administered intrapartum, adverse neonatal events associated with antibiotic administration were not specifically sought. Further trials should be designed to look at longer term outcomes, including the consequences of neonatal cerebral damage, provide a thorough understanding of the pharmcokinetic profile of the drugs administered intrapartum and evaluate more comprehensively the effectiveness of different regimens.

[Note: The six citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 19 December 2014 | Amended | The Published notes section of this review has been edited to clarify that this review has been relinquished and will not be updated. A new review on this topic has now been published (Chapman 2014) in The Cochrane Library. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2001 Review first published: Issue 3, 2002

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 January 2013 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 28 July 2011 | Amended | Information about the updating of this review added to Published notes. |

| 30 April 2010 | Amended | Search updated. Five reports added to Studies awaiting classification (Berry 1994Edwards 2004; Locksmith 2003; Locksmith 2005; Pullen 2007). |

| 31 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Notes

This review has been relinquished and will not be updated. A new review team have prepared a new review on this topic, see Chapman 2014.

Acknowledgements

None.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Intrapartum versus postpartum ampicillin and gentamicin for intraamniotic infection.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Neonatal sepsis | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.08 [0.00, 1.44] |

| 2 Neonatal pneumonia | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.15 [0.01, 2.92] |

| 3 Neonatal death | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.01, 5.75] |

| 4 Maternal bacteremia | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.19 [0.25, 19.48] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intrapartum versus postpartum ampicillin and gentamicin for intraamniotic infection, Outcome 1 Neonatal sepsis.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intrapartum versus postpartum ampicillin and gentamicin for intraamniotic infection, Outcome 2 Neonatal pneumonia.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intrapartum versus postpartum ampicillin and gentamicin for intraamniotic infection, Outcome 3 Neonatal death.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intrapartum versus postpartum ampicillin and gentamicin for intraamniotic infection, Outcome 4 Maternal bacteremia.

Comparison 2. Intrapartum ampicillin, gentamicin and clindamycin vs ampicillin and gentamicin for intraamniotic infection.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Neonatal sepsis | 1 | 133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.16 [0.20, 23.21] |

| 2 Neonatal death | 1 | 133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.12, 4.16] |

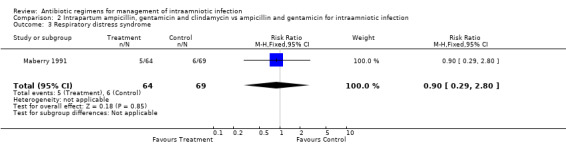

| 3 Respiratory distress syndrome | 1 | 133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.29, 2.80] |

| 4 Postpartum endometritis | 1 | 133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.19, 1.49] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Intrapartum ampicillin, gentamicin and clindamycin vs ampicillin and gentamicin for intraamniotic infection, Outcome 1 Neonatal sepsis.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Intrapartum ampicillin, gentamicin and clindamycin vs ampicillin and gentamicin for intraamniotic infection, Outcome 2 Neonatal death.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Intrapartum ampicillin, gentamicin and clindamycin vs ampicillin and gentamicin for intraamniotic infection, Outcome 3 Respiratory distress syndrome.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Intrapartum ampicillin, gentamicin and clindamycin vs ampicillin and gentamicin for intraamniotic infection, Outcome 4 Postpartum endometritis.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Gibbs 1988.

| Methods | Randomized study. Study period: May 5, 1987 to November 8, 1987. Not intention to treat. | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: maternal fever > 100 degrees F and ruptured membranes plus two or more of: maternal or fetal tachycardia, uterine tenderness, purulent or foul amniotic fluid or maternal leukocytosis. Exclusion criteria: < 34 weeks gestation, cervix < 4 cm at the time of diagnosis. | |

| Interventions | Group 1: Intrapartum treatment with ampicillin 2g iv q6h and gentamicin 1.5 mg/kg iv q8h. Group 2: Postpartum treatment with above regimen. | |

| Outcomes | Neonatal sepsis (positive blood culture): Group 1: 0/26 vs Group 2: 4/19. Neonatal pneumonia: Group 1: 0/26 vs Group 2: 2/19. Neonatal Death: Group 1: 0/26 vs Group 2: 1/19. Maternal Bacteremia: Group 1: 3/26 vs Group 2: 1/19. | |

| Notes | Power calculation for alpha error 0.05 required 46 in each arm; interim analysis forced closure of study. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Maberry 1991.

| Methods | Women admitted between December 1987 and January 1989 with intraamniotic infection were randomized to one of two arms. | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: laboring patients, gestational age > 24 weeks, amniotic infection diagnosed based on maternal fever > 38 degrees C plus one of: fetal or maternal tachycardia, uterine tenderness, foul amniotic fluid. Exclusion criteria: penicillin allergy, on antibiotics at time of admission. | |

| Interventions | Group 1: ampicillin/gentamicin/clindamycin. Group 2: ampicillin and gentamicin. | |

| Outcomes | Endometritis (fever > 38 degrees C on two occasions: Group 1: 5/64 vs 10/69. Neonatal death: Group 1: 2/64 vs Group 2: 3/69. Neonatal sepsis: Group 1: 2/64 vs Group 2: 1/69. Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Group 1: 5/64 vs Group 2: 6/69. Intraventricular Hemorrhage: Group 1: 0/64 vs Group 2: 2/69. | |

| Notes | No cases of wound infection, pelvic abscesses, septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis, or necrotizing enterocolitis. No stratification for gestational age. Average stay in hospital 4 days for both groups. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

g = gram iv = intravenous mg/kg = milligram per kilogram q6h = every 6 hours q8h = every 8 hours vs = versus

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Berry 1992 | No criteria are listed to define the diagnosis of intraamniotic infection. |

| Creatsas 1980 | This was a randomized trial examining the concentration of ampicillin and gentamicin in maternal serum, amniotic fluid and cord serum. |

| Gibbs 1980 | A retrospective chart review. All patients were managed with the same antibiotic regimen. |

| Gillstrap 1988 | This was a retrospective chart review, not a randomized trial. Also, the diagnosis of intraamniotic infection was based only on the presence of fever > 38 degrees C in labor. |

| Hauth 1985 | This is a retrospective chart review. It contains no information on antibiotic regimens utilized. |

| Koh 1979 | This is a retrospective study. There is no information on antibiotic drug regimens utilized. |

| Krohn 1998 | This is a retrospective case control study. The study was examining demographic and lifestyle characteristics in women diagnosed with intraamniotic infection. |

| McCredie‐Smith 1956 | This is a quasi‐randomized trial. The criteria for intraamniotic infection included fetal tachycardia alone, which probably led to women being included who were not infected. This would make detection of a difference with treatment difficult. Further, the antibiotics used in this trial can cause maternal and neonatal toxicity and are not utilized by obstetricians today. |

| Mitra 1997 | This study does not compare two different antibiotic regimens for the management of intraamniotic infection. Women were treated postpartum with the same drug regimen (gentamicin and clindamycin) but with either once daily or three times daily gentamicin. |

| Scalambrino 1989 | The authors do not define the parameters upon which the diagnosis of intraamniotic infection is based. In fact, they refer only to the presence of fever > 38 as their inclusion criteria and list 'cure' as their main outcome, defined as defervescence and disappearance of all signs and symptoms of infection. |

| Sperling 1987 | This is a prospective cohort study, not a randomized trial. Also, the criteria to diagnose intraamniotic infection included only a maternal fever > 100 F. |

| Stovall 1988 | This is retrospective case control study examining whether or not a short course of parenteral antibiotics without the addition of an oral agent is comparable to then‐standard extended parenteral treatment regimens. |

Contributions of authors

Laura Hopkins was responsible for designing the protocol, assessing eligibility of studies, data abstraction and writing the first draft of the review. Fiona Smaill assisted with assessing eligibility of studies, data abstraction, writing the first draft of the review and revising it in response to the editorial feedback. The published version has not been approved by Laura Hopkins.

Declarations of interest

None known.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Gibbs 1988 {published data only}

- Gibbs R, Dinsmoor MD, Newton E, Ramamurthy R. A randomized trial of intrapartum versus immediate postpartum treatment of women with intra‐amniotic infection. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1988;72(6):823‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maberry 1991 {published data only}

- Maberry M, Gilstrap L, Bawdon R, Little B, Dax J. Anaerobic coverage for intra‐amniotic infection: maternal and perinatal impact. American Journal of Perinatology 1991;8(5):338‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maberry M, Gilstrap L, Burris J, Bawdon R, Leveno K. A randomized comparative study of triple antibiotic therapy in the management of acute chorioamnionitis. Proceedings of 9th Annual Meeting of the Society of Perinatal Obstetricians; 1989; New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. 1989:465.

References to studies excluded from this review

Berry 1992 {published data only}

- Berry C, Hansen K, McCaul J. Single dose antibiotic therapy for clinical chorioamnionitis prior to vaginal delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1992;166:441. [Google Scholar]

Creatsas 1980 {published data only}

- Creatsas G, Pavlatos M, Lolis D, Kaskarelis D. Ampicillin and gentamicin in the treatment of fetal intrauterine infections. Journal of Perinatal Medicine 1980;8:13‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gibbs 1980 {published data only}

- Gibbs R, Castillo M, Rodgers P. Management of acute chorioamnionitis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1980;136(6):709‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gillstrap 1988 {published data only}

- Gilstrap L, Leveno K, Cox S, Burris J, Mashburn M, Rosenfeld C. Intrapartum treatment of acute chorioamnionitis: impact on neonatal sepsis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1988;159(3):579‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hauth 1985 {published data only}

- Hauth J, Gilstrap L, Hankins G, Connor K. Term maternal and neonatal complications of acute chorioamnionitis. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1985;66(1):59‐62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Koh 1979 {published data only}

- Koh K, Chan F, Monfared A, Ledger W, Paul R. The changing perinatal and maternal outcome in chorioamnionitis. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1979;53(6):730‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Krohn 1998 {published data only}

- Krohn M, Hitti J. Characteristics of women with clinical intraamniotic infection who deliver preterm compared with term. American Journal of Epidemiology 1998;147(2):111‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McCredie‐Smith 1956 {published data only}

- McCredie Smith J, Jennison R, Langley F. Perinatal infection and perinatal death: clinical aspects. Lancet 1956;2:903‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mitra 1997 {published data only}

- Mitra A, Whitten K, Laurent S, Anderson W. A randomized prospective study comparing once‐daily gentamicin versus thrice‐daily gentamicin in the treatment of puerperal infection. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1997;177(1):786‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Scalambrino 1989 {published data only}

- Scalambrino S, Mangioni C, Milani R, Regallo M, Norchi S, Negri L, et al. Sulbactam/ampicillin versus cefotetan in the treatment of obstetric and gynecologic infections. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 1989;2 (Suppl):21‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sperling 1987 {published data only}

- Sperling F, Ramamurthy R, Gibbs R. A comparison of intrapartum versus immediate postpartum treatment of intra‐amniotic infection. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1987;70(6):861‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stovall 1988 {published data only}

- Stovall T, Ambrose S, Ling F, Anderson G. Short‐course antibiotic therapy for the treatment of chorioamnionitis and postpartum endomyometritis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1988;159(2):404‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Berry 1994 {published data only}

- Berry C, Hansen KA, McCaul JF. Abbreviated antibiotic therapy for clinical chorioamnionitis: a randomized trial. Journal of Maternal‐Fetal Medicine 1994;3(5):216‐8. [Google Scholar]

Budanov 2000 {published data only}

- Budanov PV, Baev OR, Musaev ZM. Features of antibacterial therapy intraamniotic infections. XVI FIGO World Congress of Obstetrics & Gynecology (Book 1); 2000 Sept 3‐8; Washington DC, USA. 2000:66.

Edwards 2004 {published data only}

- Edwards RK, Duff P. One additional dose of antibiotics is sufficient postpartum therapy for chorioamnionitis [abstract]. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2004;12(3/4):167. [Google Scholar]

Locksmith 2003 {published data only}

- Locksmith G, Chin A, Vu T, Shattuck K, Hankins G. High versus standard dosing of gentamicin in women with chorioamnionitis: a randomized, controlled, pharmacokinetic analysis [abstract]. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2003;189(6 Suppl 1):S103. [Google Scholar]

Locksmith 2005 {published data only}

- Locksmith GJ, Chin A, Vu T, Shattuck KE, Hankins GDV. High compared with standard gentamicin dosing for chorioamnionitis: a comparison of maternal and fetal serum drug levels. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2005;105:473‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pullen 2007 {published data only}

- Pullen K, Zamah M, Fuh K, Caughey A, Benitz W, Lyell D, et al. Once daily vs. 8 hour gentamicin dosing for chorioamnionitis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2007;197(6 Suppl 1):S68. [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Chapman 2014

- Chapman E, Reveiz L, Illanes E, Bonfill Cosp X. Antibiotic regimens for management of intra‐amniotic infection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 12. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010976.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Duff 1993

- Duff P. Antibiotic selection for infections in obstetric patients. Seminars in Perinatology 1993;17(6):367‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hagberg 2002

- Hagberg H, Wennerholm UB, Savman K. Sequelae of chorioamnionitis. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases 2002;15(3):301‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Newton 1989

- Newton ER, Prihoda TJ, Gibbs RS. Logistic regression analysis of risk factors for intra‐amniotic infection. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1989;73:571‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schuchat 1992

- Schuchat A, Deaver DA, Wenger JD, Plikaytis BD, Mascola L, Pinner RW, et al. Role of foods in sporadic listeriosis: Case‐control study of dietary risk factors. Journal of the American Medical Association 1992;267:2041‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Soper 1989

- Soper DE, Mayhall G, Dalton HP. Risk factors for intra‐amniotic infection: A prospective epidemiologic study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1989;161:562‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sweet 1985

- Sweet RL, Gibbs RS. Intraamniotic infections (intrauterine infection in late pregnancy). Infectious Diseases of the Female Genital Tract. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1985:236‐76. [Google Scholar]

Westover 1995

- Westover T, Knuppel R. Modern management of clinical chorioamnionitis. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology 1995;3:123‐32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Smaill 1995

- Smaill F. Intrapartum vs postpartum treatment of amniotic infection [revised 04 October 1993]. In: Enkin MW, Keirse MJNC, Renfrew MJ, Neilson JP, Crowther C (eds.) Pregnancy and Childbirth Module. In: The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database [database on disk and CDROM]. The Cochrane Collaboration; Issue 2, Oxford: Update Software; 1995.