Abstract

Background

Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) causes ear discharge and impairs hearing.

Objectives

Assess topical antibiotics (excluding steroids) for treating chronically discharging ears with underlying eardrum perforations (CSOM).

Search methods

The Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Group Trials Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library Issue 1, 2005), MEDLINE (January 1951 to March 2005), EMBASE (January 1974 to March 2005), LILACS (January 1982 to March 2005), AMED (1985 to March 2005), CINAHL (January 1982 to March 2005), OLDMEDLINE (January 1958 to December 1965), PREMEDLINE, metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT), and article references.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials; any topical antibiotic without steroids, versus no drug treatment, aural toilet, topical antiseptics, or other topical antibiotics excluding steroids; participants with CSOM.

Data collection and analysis

One author assessed eligibility and quality, extracted data, entered data onto RevMan; two authors inputted where there was ambiguity. We contacted investigators for clarifications.

Main results

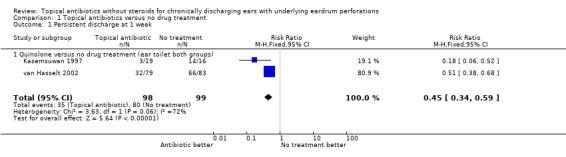

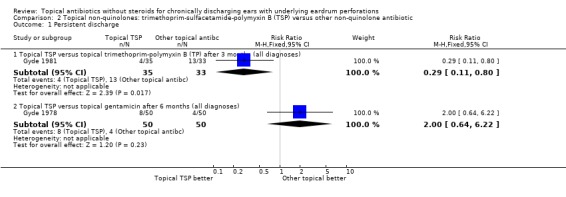

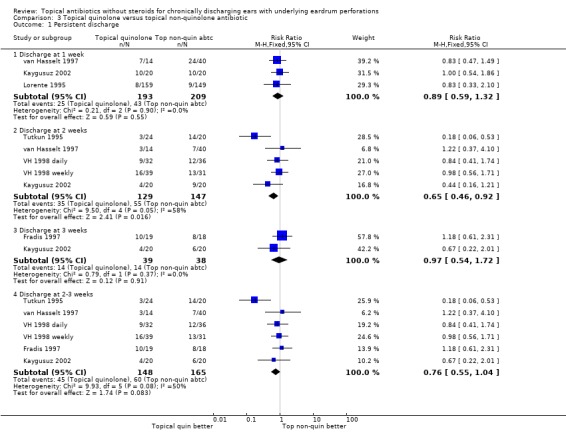

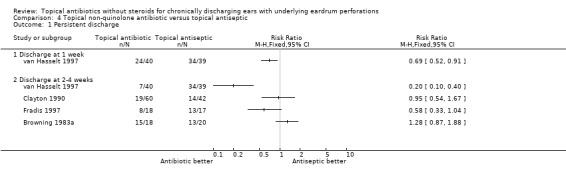

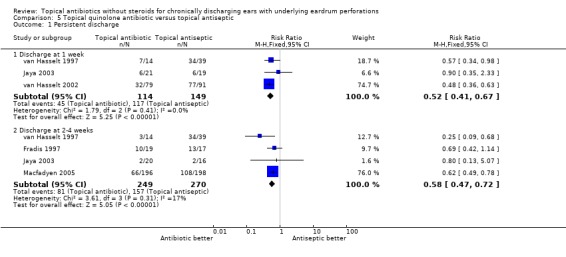

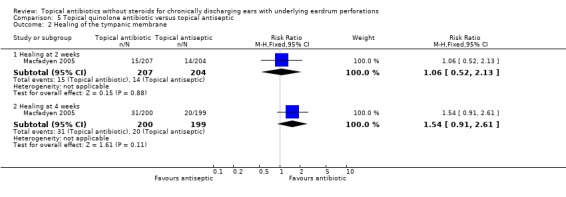

Fourteen trials (1,724 analysed participants or ears). CSOM definitions and severity varied; some included otitis externa, mastoid cavity infections and other diagnoses. Methodological quality varied; generally poorly reported, follow‐up usually short, handling of bilateral disease inconsistent. Topical quinolone antibiotics were better than no drug treatment at clearing discharge at one week: relative risk (RR) was 0.45 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.34 to 0.59) (two trials, N = 197). No statistically significant difference was found between quinolone and non‐quinolone antibiotics (without steroids) at weeks one or three: pooled RR were 0.89 (95% CI 0.59 to 1.32) (three trials, N = 402), and 0.97 (0.54 to 1.72) (two trials, N = 77), respectively. A positive trend in favour of quinolones seen at two weeks was largely due to one trial and not significant after accounting for heterogeneity: pooled RR 0.65 (0.46 to 0.92) (four trials, N = 276) using the fixed‐effect model, and 0.64 (95% CI 0.35 to 1.17) accounting for heterogeneity with the random‐effects model. Topical quinolones were significantly better at curing CSOM than antiseptics: RR 0.52 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.67) at one week (three trials, N = 263), and 0.58 (0.47 to 0.72) at two to four weeks (four trials, N = 519). Meanwhile, non‐quinolone antibiotics (without steroids) compared to antiseptics were more mixed, changing over time (four trials, N = 254). Evidence regarding safety was generally weak.

Authors' conclusions

Topical quinolone antibiotics can clear aural discharge better than no drug treatment or topical antiseptics; non‐quinolone antibiotic effects (without steroids) versus no drug or antiseptics are less clear. Studies were also inconclusive regarding any differences between quinolone and non‐quinolone antibiotics, although indirect comparisons suggest a benefit of topical quinolones cannot be ruled out. Further trials should clarify non‐quinolone antibiotic effects, assess longer‐term outcomes (for resolution, healing, hearing, or complications) and include further safety assessments, particularly to clarify the risks of ototoxicity and whether quinolones may result in fewer adverse events than other topical treatments.

Keywords: Humans; Anti‐Bacterial Agents; Anti‐Bacterial Agents/therapeutic use; Anti‐Infective Agents, Local; Anti‐Infective Agents, Local/therapeutic use; Chronic Disease; Developing Countries; Hearing Disorders; Hearing Disorders/drug therapy; Hearing Disorders/etiology; Otitis Media, Suppurative; Otitis Media, Suppurative/complications; Otitis Media, Suppurative/drug therapy; Quinolones; Quinolones/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Tympanic Membrane Perforation; Tympanic Membrane Perforation/complications; Tympanic Membrane Perforation/drug therapy

A Cochrane systematic review assessing topical antibiotics without steroids for treating chronically discharging ears with underlying eardrum perforations, in participants of any age

Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) is an infection of the middle ear with pus and a persistent perforation in the eardrum. It is a common cause of preventable hearing impairment, particularly in low and middle‐income countries. This review assesses topical antibiotics (without steroids), to clarify whether they are better than no treatment or aural toilet (cleaning of the ear discharge), or treatment with topical antiseptics and to identify which antibiotic is best. Fourteen randomised controlled trials were included (1,724 analysed participants or ears); most were poorly reported, and some included a range of diagnoses.

Quinolone antibiotic drops (considered to be the 'gold standard' topical antibiotics) are better than no drug treatment or antiseptics at drying the ear. The effects of non‐quinolone antibiotics (without steroids) when compared to antiseptics are less clear. Studies were also inconclusive regarding any differences between quinolone and non‐quinolone antibiotics, although indirect evidence suggests a benefit of quinolones cannot be ruled out. Less is known about longer‐term outcomes (producing a dry ear in the long term, preventing complications, healing the eardrum, and improving hearing), or about treating complicated CSOM. The evidence in these trials about safety is also weak. More research is needed to assess whether there may be fewer adverse events with topical quinolones than with alternative topical treatments.

Background

Chronically discharging ears associated with underlying persistent eardrum perforations (chronic suppurative otitis media, CSOM) are a common cause of preventable hearing impairment in low and middle‐income countries (McPherson 1997; WHO 1998). CSOM usually occurs in the first five years of life (although it often persists into adulthood), and is related to poor socio‐economic conditions. Therefore, while this review aims to address the global perspective of CSOM, much of the information discussed here relates to low‐income settings and may differ in developed countries (e.g. age distribution).

What is CSOM?

CSOM is one of several types of otitis media (infection of the middle ear). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines CSOM as "a stage of ear disease in which there is chronic infection of the middle ear cleft, a non‐intact tympanic membrane (i.e. perforated eardrum) and discharge (otorrhoea), for at least the preceding two weeks" (WHO 1998), although this could more strictly be considered a childhood definition. Perforations and infection can be in one ear (unilateral) or both (bilateral). A variety of underlying pathologies can cause CSOM including: an acute episode of acute otitis media that has burst the ear drum and not settled within two weeks; a recurrent episode of acute otitis media in an ear with a perforation from a previous episode of acute otitis media; or an ear with a persistent perforation with active chronic otitis media with metaplastic changes to the mucosa of the middle ear and mastoid air cell system (Browning 2003, personal correspondence). In adults, the majority of patients are likely to have CSOM with a perforation that will not spontaneously heal.

What are the effects of CSOM?

Hearing impairment, aside from the disability from recurrent ear discharge, is the most frequent effect of CSOM. A school survey in Kenya found 63% of ears with CSOM had more than 30 decibels (dB) hearing loss, compared to only 3.4% of ears without outer or middle ear pathology (Hatcher 1995). Hearing impairment due to otorrhoea and a perforated eardrum will usually improve as the disease resolves. However, untreated CSOM may result in permanent hearing loss due to damage to the ossicles which transmit sound vibrations from the eardrum to the cochlea. Because otitis media occurs mostly in children during preschool years, the years in which the most dynamic phase of speech and language development occurs, there is concern that the associated hearing deficits may result in speech and language delays or permanent learning disabilities, as well as disturbances in behaviour (Klein 2000).

In addition to hearing impairment (with its associated consequences), complications of otitis media can often result in death or severe disability, especially in low‐income countries (WHO 2000), where immunity, housing conditions, and access to medical services are often poorer than in high income settings. The infection may extend and spread to the head and neck structures and to the brain. Intracranial infections include meningitis, abscesses, hydrocephalus, or thrombosis of the lateral venous sinus (from suppuration within the mastoid causing clots occluding the lumen of the vessel) (Ludman 1997). Alternatively complications may be extracranial, such as subperiosteal abscess (superficial accumulations of pus that have broken the bony mastoid cortex), facial paralysis, cholesteatoma (a destructive formation of layers of keratinising epithelium, accumulating in the middle ear and mastoid (Bluestone 1996), also described as 'active squamous (epithelial) chronic otitis media (Browning 1997)), labyrinthitis (extension to the labyrinth through the round window), or acute mastoiditis (spread of the infection to the mastoid air cells), which may spread further due to necrosis of the bony wall of the cells resulting in further life‐threatening complications (Dhillon 1999; Ludman 1997).

How much of a burden is CSOM?

Around 91% of the burden of otitis media (all types) and nearly all related deaths occur in low and middle‐income countries (World Bank 1993; WHO 2002). Reliable data on prevalence of CSOM are uncommon. One study estimated it at 1.1% in Kenyan school children (Hatcher 1995) and a review of school and community‐based studies reported a prevalence between 0.4% and 6.1% in low and middle‐income countries (Berman 1995). Data from the World Health Organization and World Bank suggest the global burden of otitis media has dropped dramatically since 1990, to approximately 6000 deaths (0.01% of all deaths) and 1,474,000 disability adjusted life years (DALYs) lost (0.1% of all DALYs) worldwide in 2001 (WHO 2002). Most of these deaths are likely to be due to chronic otitis media and its complications, because acute otitis media is usually a self‐limiting infection (Acuin 2004).

Although most of the background literature cited in this review relates to children, reliable and generalisable data for the global burden in children are not readily available; the WHO estimates therefore quoted here are for both adults and children.

What are the causes of CSOM?

The causes and risk factors associated with CSOM are unclear, and few studies have examined these for CSOM. Instead authors have extrapolated results of studies for acute otitis media and otitis media with effusion to CSOM. However these studies often have conflicting findings, and there is no proven correlation between the various host and environmental factors associated with CSOM and the factors associated with acute otitis media and otitis media with effusion. Despite this, some important factors that may be associated with CSOM include: environmental factors such as inadequate treatment (of CSOM and acute otitis media), poor access to medical care, poor socioeconomic conditions, season, exposure to tobacco smoke, overcrowding, attendance at day care centres, lack of breastfeeding, or poor nutrition or hygiene; and host factors such as altered immunity and underlying diseases (e.g. HIV/AIDS (Barnett 1992; Singh 2003), frequent upper respiratory tract infections), early onset of otitis media in the first months of life, and family history of otitis media. Some populations are at increased risk of developing CSOM, and have high rates reported, including certain ethnic groups (such as Native American tribes of Apache and Navajo, Australian Aborigines, and Inuits of Canada, Greenland and Alaska), and individuals with anatomical defects (e.g. cleft palate or submucous cleft), altered physiological defences (Eustachian tube dysfunction) or Down's syndrome (Bluestone 1998).

What management approaches are there?

The aims of treatment are to stop the discharge (and to eradicate infection), to heal the tympanic membrane, improve hearing, prevent the common problems of recurrent or new infections, and to prevent potentially life‐threatening complications. Treatment options for uncomplicated CSOM include dry mopping, ear wicking, gentle syringing, or suctioning, to clean the ear discharge (aural toilet); systemic antibiotics (e.g. oral antibiotic preparations, or intravenous antibiotics); and topical treatment with either antiseptics or antibiotics, sometimes with steroids. If complications develop, surgery is usually required to remove the infected tissue from the middle ear and mastoid air cells, and possibly repair the damaged eardrum and ossicles. Each of these treatments will be considered in the following Cochrane reviews:

aural toilet: aural toilet versus no treatment or various methods of aural toilet

systemic antibiotic treatment: systemic antibiotics versus no treatment or aural toilet, or various methods of systemic antibiotics

topical antiseptics: topical antiseptic versus no treatment or aural toilet, or various topical antiseptics

topical antibiotics without steroids (THIS REVIEW): topical antibiotic, versus no treatment or aural toilet, topical antiseptics or various topical antibiotics, excluding steroids

systemic versus topical treatments: any systemic treatment against any topical treatment excluding steroids

systemic or topical steroids: steroids, as monotherapy or combination therapy, versus no treatment or aural toilet, topical antiseptics, topical antibiotics, or systemic antibiotics

surgical treatment: surgery versus no treatment or any other treatment

A report of a WHO/Ciba Foundation workshop held in 1996, recommends administration of topical (and/or systemic) antibiotics as well as dry mopping/wicking, since wicking alone is suggested to be ineffective (as found by Smith 1996) (WHO 1998). However, the WHO guidelines still currently recommend treating CSOM by using wicking to dry the ear alone (and a five‐day follow‐up).

Topical treatment with antibiotics

A number of topical antibiotics have been used in the treatment of CSOM. However, concern exists regarding their ability to penetrate the middle ear and mastoid cavities as well as their activity against the causative bacteria (usually gram‐negative). There also remains controversy and uncertainty about the possible ototoxic effect, in particular of topical aminoglycoside antibiotics (by damaging the hair cells in the basal turn of the cochlea), particularly where the eardrum is not intact. The newer 4‐quinolone antibiotics (e.g. ciprofloxacin) are widely considered to be the 'gold standard' topical antibiotics, but are expensive and not generally available as ototopical preparations in many countries. Topical antibiotics may be superior to topical antiseptics, although this needs investigating, particularly as topical antiseptics are cheap and easily available, and are thus widely used in many low and middle‐income countries.

Objectives

To assess the effects of topical antibiotics (excluding steroids) for chronically discharging ears with underlying eardrum perforations (CSOM) in participants of any age.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Individual randomised controlled trials. Cluster randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

People of any age with a diagnosis of CSOM as defined by the trial authors.

Types of interventions

Intervention: topical (aural) antibiotics without steroids. Comparator: no intervention; aural toilet; placebo; other topical antibiotics without steroids; antiseptics. (Treatments containing steroids will not be included here, but will be considered in a separate Cochrane review, as indicated above).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Resolution of CSOM at two to four weeks, and after four weeks, according to the investigators' criteria

Secondary outcomes

Healing of perforation at two to four weeks, and after four weeks

Time to resolution of CSOM as defined by the investigators

Improvement in hearing threshold, as measured by audiometry at two to four weeks, and after four weeks

Time to re‐appearance of discharge and perforation after its previous resolution

Adverse events that

a) are fatal, life‐threatening, require inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, or result in persistent or significant disability/incapacity, such as permanent hearing loss, tinnitus or vertigo (Karbwang 1999; UMC 2003) b) result in withdrawal or discontinuation of treatment c) any other adverse events, such as ear pain, ear canal reactions and transient dizziness

Where outcomes (resolution of discharge, healing of the tympanic membrane, and hearing threshold) are reported at several time‐points within the ranges above, we took the last reported result.

Search methods for identification of studies

The Trials Search Co‐ordinator of the Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Group carried out an independent search in August 2003 and March 2005.

We attempted to identify all relevant studies regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, and in progress). Trials reported in conference proceedings or on posters have not been sought for this review, but will be sought for inclusion in an update of this review.

We searched the Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Group Trials Register (code SR‐ENT), and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), published in The Cochrane Library Issue 1, 2005, for relevant trials up to March 2005. Full details of the Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Group methods and the journals handsearched are published in The Cochrane Library in the section on Collaborative Review Groups.

CENTRAL was searched using the terms shown in Appendix 1.

Using the CENTRAL search terms, in combination with the search strategy for identifying trials developed by The Cochrane Collaboration (Clarke 2003), we also searched the following databases:

(1) MEDLINE (January 1951 to March 2005) (2) EMBASE (January 1974 to March 2005) (3) LILACS (www.bireme.br; January 1982 to March 2005) (4) AMED (1985 to March 2005) (5) CINAHL (January 1982 to March 2005) (6) OLDMEDLINE (January 1958 to December 1965) (7) PREMEDLINE (8) NNR (9) ZETOC

We searched the following potential sources of trials:

metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT accessible via the Internet: http://controlled‐trials.com/mrct/)

Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Group Trials Register for any relevant abstracts from conference proceedings

Reference lists of all articles/trials identified by the above methods (includes searching of bibliographies for relevant citations)

Previous published Cochrane review, 'Interventions for chronic suppurative otitis media' (Acuin 1998)

Other previously published (systematic) reviews: 'Chronic suppurative otitis media', in Clinical Evidence (Acuin 2004), and 'Systematic Review of Existing Evidence and Primary Care Guidelines on the Management of Otitis Media (Middle Ear Infection) in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Populations, March 2001 (Couzos 2001)

DARE using issues 2 and 3 of Tthe Cochrane Library 2003 ‐ searched for systematic reviews

We will explore the following potential sources of trials for future updates of this review:

Other previously published (systematic) reviews identified by the above search strategy

Organisations and individual researchers working in the field of otitis media (including authors of published trials and other experts who may know about additional trials)

Pharmaceutical companies (see published notes for list of companies contacted) to locate additional studies, unpublished data, confidential reports, and raw data of published trials

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Carolyn Macfadyen (CM) and Jose Acuin (JA) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts identified by the search strategy to identify potentially relevant trials.

CM retrieved the full papers for all potentially relevant studies, and assessed their eligibility to be included in the review using an eligibility form based on the stated inclusion criteria. We identified multiple publications from the same data set and reported these as one trial. Where outcomes are not reported, we contacted the author of the paper for this information, as the data may have been collected but not reported. We excluded studies that do not meet the inclusion criteria for this review and stated the reason in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table. Where necessary, we contacted the study authors for clarification.

JA and Carrol Gamble (CG) provided a second opinion on trials CM had selected for inclusion, and the three authors resolved any disagreements through discussion.

Data extraction and management

CM extracted data of study characteristics, including methods, participants, interventions, and outcomes, and recorded these on standard forms. JA provided further information where this had been obtained from authors of trials included in the previous review 'Interventions for chronic suppurative otitis media' (Acuin 1998). In studies where data are insufficient or missing, we contacted the authors of the original studies for additional data and/or verification of methods, to clarify any uncertainties about the data and the way in which they were collected, and to try to obtain missing data.

CSOM can occur in one or both ears for each participant, which means participants can be counted more than once if ears are used as the unit of analysis. Where outcomes were reported in number of ears only, we also attempted to obtain the values for number of participants; numbers of ears were used where this information could not be obtained. We checked the data and resolved any discrepancies by referring to the trial report, through discussion.

Where possible we extracted data to allow an intention‐to‐treat analysis (i.e. the analysis should include all the participants in the groups to which they were originally randomly assigned). If the number randomised and the numbers analysed were inconsistent, we calculated a per cent loss‐to‐follow‐up and reported this information in Table 6. For binary outcomes, we recorded total number of participants (or ears, where participant numbers were unavailable) and number with the event in each group of the trial. For continuous outcomes, for each group, we extracted the number of participants, and the arithmetic means and standard deviations. If the data were reported using geometric means, we planned to extract standard deviations on the log scale. We planned to extract medians and ranges, and report these in additional tables if any trials reported these.

Table 1.

Methodological quality of included studies

| Study ID | Sequence generation | Alloc. concealment | Balance at baseline? | Blinding | Follow‐up |

| Browning 1983a | Unclear Treatment allocation described as random, using random numbered list kept by the pharmacist, who dispensed the medication, but method of sequence code generation was not stated. The choice of antibiotic depended on sensitivity results of ear discharge isolates. Participants with Pseudomonas species isolated were randomised to topical antibiotics or antiseptics only ‐ not to oral antibiotics due to resistance. Did not discuss whether randomisation was stratified by the different diagnostic groups (and results not reported separately in trial report). | Unclear Medication was supplied in the clinic by the pharmacist using the random numbered list, after eligibility assessments by the clinicians, who were blinded (except for antiseptic). Whether treatment was concealed from the pharmacist is not discussed. | Unclear Baseline characteristics (including the distribution of participants with and without modified radical mastoidectomy) not reported. | Single blind Allocation was kept blinded from the clinicians, with the necessary exception of antiseptic, given by the otologist after aural toilet. | Inadequate 32% dropout: 24/75 participants were defaulters or non‐compliers (ie used <75% of the medication). (Numbers excluded not given by treatment group or diagnosis). Results given for the 51 participants who complied with treatment only (38 on topical antibiotics or antiseptics, included in this review). |

| Clayton 1990 | Unclear Treatment allocation described as random, with medication codes; but no further details of sequence generation method were given. Did not discuss whether randomisation was stratified by the different diagnostic groups ‐ therefore included all participants in this review. | Adequate Patients were randomly allocated treatment in a double‐blind fashion. Medication codes were known only by the pharmacy. | No The following imbalances were reported for analysed participants, after exclusions (due to failure to attend clinic or comply with treatment; exclusions were not reported by treatment group): Significant bias (P=0.0002) for more mildest disease score (score 1) in the antiseptic group (1/60) than antibiotic (11/42) ‐ scores not presented by diagnosis; More ears with otitis externa (significant) and central perforations (not reported as significant) were analysed in the antibiotic group than antiseptic (see Table 02 for numbers). | Double blinded | Inadequate Dropout rates (numbers of randomised ears that were excluded; not reported by treatment group): 25% (5/20) central perforations; 30% (9/30) mastoid cavity infections; 25.8% (23/89) otitis externa ; 26.6% (37/139) total. Patients who failed to attend clinics or to comply with treatment were excluded. |

| Fradis 1997 | Unclear Participants were randomised to treatment, with coded bottles, but method of sequence code generation not described. Participants with otorrhoea in both ears were given two different bottles. | Adequate All numbered treatment bottles were similar in appearance. Treatment bottles and code were retained in the hospital pharmacy; only the pharmacy department head knew what each bottle contained. | Yes Groups comparable for age and bacteriology (although slight imbalance in numbers of positive cultures: 18 ciprofloxacin, 16 tobramycin, 12 antiseptic/placebo). No information was given for treatment groups of cases of surgical perforation or where no perforation could be seen. | Double blind The treating physician and participants were blinded to treatment. The treatment code was only broken at the end of the study to summarise the results of the investigation. | Adequate Adequate for ears, which were the unit of analysis, but slightly inadequate for participants: 6/60 (10%) randomised ears (6/51 participants, ie 12%) were unavailable for follow‐up after three weeks. Excluded numbers by treatment group: Ciprofloxacin: 1/20 ears (5%) Tobramycin: 2/20 ears (10%) 1% Burow aluminium acetate: 3/20 ears (15%) |

| Gyde 1978 | Adequate Used Taves' method of minimisation, with type of infection as the principal criteria. Minimisation is an alternative method to stratified randomisation for treatment allocation. It is sometimes recommended for small sample sizes, and can incorporate more prognostic factors (Scott 2002). Unclear whether 'type of infection' relates to diagnosis or bacteriology ‐ therefore included all participants in this review. | Unclear Allocation concealment not mentioned, except that solutions were called 'A' (TSP) and 'B' (gentamicin) (trial was described as double blind). Taves' minimisation approach can lead to predictability of treatment allocation in some situations. | Yes Ears were balanced accross treatments for diagnosis (equal numbers per treatment) before and after crossover. Balanced for age, sex, and diagnosis, with no great differences betwen the seriousness of infections in the two groups, according to the trialists. These results are for all ears including crossed‐over cases, so some participants are counted twice (bilateral disease or crossover) and 1 was counted 4 times (bilateral disease and crossed over). But there was more bilateral disease in the TSP group (7/43 participants = 16.3%) than on gentamicin (2/48=4.2%), for all participants before crossover. | Double‐blind The solutions were called 'A' (TSP) and 'B' (gentamicin) to conserve the double blind. The treatment provider/outcome assessor was blinded until after the analysis of the results. Participants were also blinded. | Unclear No withdrawal was reported ‐ numbers analysed are the same as the reported numbers eligible for the study. But participants unable to continue the proposed length of treatment or return for follow‐up visits were excluded. Appears to be only per protocol population reported and analysed; number of excluded noncompliers was not reported. |

| Gyde 1981 | Unclear Participants were randomly assigned to one treatment group using coded medications, but method of generation of random codes was not described. Did not discuss whether randomisation was stratified by the different diagnostic groups ‐ therefore included all participants in this review. | Adequate Medications were coded and identically labelled, and used sequentially starting with the lowest number; no number was skipped or used more than once. | Mostly Comparable across treatment groups (for ears) for diagnosis. Overall results for age and bacteria were also comparable (not broken down by diagnosis). But there was a slightly higher proportion of males in the TP group (17/33 ears, 51.5%) than the TSP group (25/35 ears, 71.4%). | Double blind | Unclear No withdrawal was reported ‐ number analysed is the same as the reported number of ears eligible for the study. But participants unable to continue the proposed length of treatment or return for follow‐up visits were excluded. Appears to be only per protocol population reported and analysed; number of excluded noncompliers was not reported. |

| Jaya 2003 | Unclear Treatment allocation described as random, with coded bottles, but method of generation of random codes was not described. | Adequate Both drugs were coloured identically and were dispensed in identical bottles, labelled with code numbers only ‐ given to participants after baseline assessments. | Mostly Comparable for a range of demographic and disease related (prognostic) factors, except more participants receiving PVP‐I were male (10/19, 52.6%), than on ciprofloxacin (4/21, or 19.0%). Other prognostic criteria were assessed and found to have no significant effect on the outcomes for the compared treatments. | Double blinded The randomisation code was only decoded at the end of the study. | Adequate 10% dropout rate: 4/40 randomised participants were excluded by week 4 (1/21 ciprofloxacin; 3/19 PVP‐I ). Reasons for exclusion from the analysis were not given. |

| Kasemsuwan 1997 | Unclear Treatment allocation was described as random, with coded medications, but method of generation of random codes was not specified. | Adequate Participants were randomly allocated treatment in a double blind method. The medication codes were known only in the pharmaceutical laboratory. | Unclear Baseline characteristics not reported for each group. | Double blind | Inadequate 30% dropout: 15/50 participants were excluded due to lack of attendance. Participants who received other antibiotics during the trial were also excluded. |

| Kaygusuz 2002 | Unclear Treatment allocation described as random, but randomisation method was not stated. | Unclear Allocation concealment not reported ‐ nor was blinding. | Yes for bacteriology Baseline characteristics only reported for infective organism, which was comparable accross groups. | Unclear Blinding not mentioned. | Adequate No loss to follow‐up or exclusions were reported. 80 participants were reported as included in the study and analysed. |

| Lorente 1995 | Unclear Treatment allocation described as randomised, but randomisation method was not stated. | Unclear Allocation concealment methods were not stated ‐ but trial was double blind. | Yes Comparable for age sex, otorrhoea, itching, stinging, pain, irritation, and tinnitus. | Double‐blind | Unclear Not clear how many people were originally randomised into the trial. (No exclusion was reported.) |

| Macfadyen 2005 | Adequate Treatment was prepared according to computer generated block randomisation schedule, stratified by school. | Adequate. Treatment was identical in appearance, and identically labeled and packaged in treatment boxes, identifiable by school name and trial number only. Treatment packs remained sealed until sequentially allocated to a child. | Yes Comparable for age*, sex, duration of current episode*, proportion of bilateral cases*, size of perforation*, cause of current episode, whether previous ear treatment had ever been used, and hearing level. * Logistic regression adjusting for these factors did not significantly alter the treatment effect. | Double blind Participants, care‐givers, and outcome assessors remained blind to the treatment allocated throughout the study. | Adequate Number with missing data and so excluded from analysis for resolution of discharge at four weeks: 33/427 (7.7%) total; 20/216 (9%) ciprofloxacin; 13/211 (6%) boric acid. Some of these were due to missing data for participants seen at that visit. The rest were due to withdrawals or lost to follow up: 25/427 (5.9%) total; 16/216 (7.4%) ciprofloxacin (15 lost to follow‐up; 1 consent withdrawn); 9/211 (4.3%) boric acid (all lost to follow‐up). All analyses followed the Intention To Treat principle. |

| Tutkun 1995 | Unclear Participants were randomly divided into two groups but randomisation method was not stated. | Unclear Allocation concealment not reported ‐ nor was blinding. | Unclear? Only reported baseline data for bacteriology ‐ comparable apart from "normal flora" isolated in the ciprofloxacin group only (4 cases; excluded from hearing analyses in Ozagar 1997. | Unclear Blinding not mentioned. | Unclear It is not clear how many people were originally randomised into the trial ‐ an unreported number of non‐compliers (participants who did not use the topical solutions regularly and those who had taken any other medication during the study period) were excluded from study. 4 participants were excluded from the hearing analysis (and clinical response in Ozagar 1997). |

| van Hasselt 1997 | Unclear Described as a randomised trial in 2002 paper, but randomisation method was not stated. | Unclear Allocation concealment not reported ‐ nor was blinding. | Unclear Baseline characteristics were not provided. | Unclear Blinding not mentioned. | Inadequate 28% dropout: 27/96 participants did not complete the trial. Ofloxacin: 8% dropout (1/12 participants) Neomycin/polymyxin B: 21% dropout (8/38 participants) Acetic acid/spirit: 39% dropout (18/46 participants) Only children completing the trial fully (ie attended at both review dates) were included in the analysis. |

| van Hasselt 1998 | Unclear Described as a randomised trial, but randomisation method was not stated. | Unclear Allocation concealment not reported ‐ but trial was double‐blind. | Unclear Baseline characteristics were not provided. | Double‐blind | Adequate (except week 8) Number excluded from the analysis: Week 1: 12/151 ears (8%); Week 2: 13/151 ears (9%) ; Week 8: 23/151 ears (15%). 'Defaulting ears' were excluded. |

| van Hasselt 2002 | Unclear Described as a randomised trial, but randomisation method was not stated. | Unclear Allocation concealment not reported ‐ but trial was double‐blind. | Unclear Baseline characteristics were not provided. | Double‐blind | Unclear Not clear how many people were originally randomised into the trial. |

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

CM assessed the methodological quality of all the trials identified as eligible for inclusion. CG reviewed trials where there was any ambiguity about the methods used, and JA provided further information where this had already been obtained from authors of trials included in the previous review 'Interventions for chronic suppurative otitis media' (Acuin 1998). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion. Where necessary, we contacted the study authors for further clarification.

We assessed the methodological quality of the trials in terms of generation of allocation sequence, allocation concealment, blinding and inclusion of randomised participants. We classified generation of allocation sequence, allocation concealment, and inclusion of randomised participants as adequate, inadequate and unclear as outlined by Juni 2001. Blinding is classified as double blind, single blind, or open.

Data synthesis

CM entered data into Review Manager 4.2. In studies that enrolled people with otitis externa, draining surgical cavities or acute otitis media, as well as CSOM, we only included the results for just CSOM participants if the authors reported accounting for diagnosis at randomisation (e.g. stratified by diagnosis) and presented results by diagnosis. Where information was not reported regarding whether alternative diagnostic groups were accounted for at randomisation, we included all participants (groups may be unbalanced, and decisions by trialists to report subgroups may have been linked to trend). We also included all participants where separate results were not available. See Table 7 for details. For crossover trials, we have only taken the results before participants were crossed over to the alternative treatment, where possible; otherwise results for all participants combining pre and post‐crossover data were used.

Table 2.

Participant eligibility criteria, including CSOM diagnostic criteria

| Study ID | CSOM diagnosis | Otitis exclusions | Other elig criteria | Disease duration | Bacteriology? | Mucosal appearance? | Other diagnoses? | Other diags: sep? |

| Browning 1983a | Active chronic otitis media including previous modified radical mastoidectomy participants. | 1) Cholesteatoma 2) Aural polyp | Non‐otitis inclusion criteria: 1) Over 16 years old Exclusions ‐ see otitis exclusions; no other exclusions were specified. | Not specified ‐ but all participants were secondary referrals | Yes. Sensitivity of isolated aerobic flora determined the choice of antibiotic. Participants with Pseudomonas spp were not randomised to oral (systemic) antibiotic. | Not reported | 19/51 (i.e. 37%) analysed participants had previously undergone modified radical mastoidectomy (not provided by treatment group). NB: only 38/51 on topical antibiotics or antiseptics included in this review (2 of 3 treatment groups) | No |

| Clayton 1990 | Otorrhoea caused by: a) discharging central perforation; b) mastoid cavity; c) otitis externa. | 1) Acute middle ear disease 2) Cholesteatoma 3) Clinical evidence of fungal ear infection | Exclusion criteria ‐ treatment related: 1) Topical or systemic antibiotic use in previous three weeks; 2) History of drug sensitivity to any of the agents used in the study. | Not specified ‐ but excluded acute middle ear disease | Indicated; Not required for inclusion: 11.7% had no bacteria isolated. | Yes: scoring system of severity included presence and degree of oedema obscuring the tympanic membrane or mastoid cavity, or of oedematous mucosa lining the mastoid cavity. | Included otorrhoea from mastoid cavity and otitis externa. a) Discharging central perforation: 15 ears + 5 excluded b) Mastoid cavity: 21 ears + 9 excluded c) Otitis externa: 66 ears + 23 excluded Participants who failed to attend clinic or comply with treatment were excluded (numbers not given by treatment group). | Not separate in review: randomisation not reported to stratify by diagnosis. But results were given by diagnosis separately in trial publication. |

| Fradis 1997 | CSOM was defined as a chronic inflammation of the middle ear and mastoid process with a perforated tympanic membrane and discharge. All cases had purulent disease. | 1) Prior middle‐ear surgery 2) Suspected cholesteatoma | Other inclusion criteria: 1) Signed consent 2) Discontinued all other medications two weeks before study entry. Exclusion criteria ‐ treatment related 1) History of allergy to aminoglycosides or fluoroquinolone derivatives. Exclusion criteria ‐ other 1) General health problems 2) Younger than 18 years (range was 18 to 73 years) | Disease duration: mean (range): 24 months (1 to 240 months). | Indicated; Not required for inclusion: 23/60 cultures were negative for organisms before treatment. | In 8/60 ears granulation tissue meant no perforation could be seen | a) 3/60 ears: surgical perforations; b) 8/60 ears: no perforation seen due to granulation tissue | No |

| Gyde 1978 | 1) Otorrhoea from: a) recurrent benign chronic otitis media with tympanic membrane perforation (CSOM); b) postoperative infections (mastoidectomy or tympanoplasty) and mastoid cavity infections; c) subacute otitis media (with small or medium perforation); d) external otitis. | 1) Otorrhoea not caused by bacteria 2) 'Unsafe' ears (active atticoantral disease, accompanied by cholesteatoma with adjacent area extension) | Inclusion criteria ‐ other: 1) Adults or children ‐ includes paediatric cases (under 12 years old), and geriatric cases (over 60 years old). 2) Informed consent Exclusion criteria ‐ treatment related: 1) Known allergy to any components of the trial drugs. 2) Use of high doses of local (topical) corticosteroid preparations. 3) Previous use of ototoxic drug therapy. 4) Use of general or topical antibiotics within two weeks before study entry. 5) Unable to continue the proposed length of treatment or return for follow‐up visits due to distance or inconvenience. Exclusion criteria ‐ other: 1) Pregnant or lactating. 2) Infants under 2 months old. | Not specified | Indicated with results; Required for inclusion. | Not reported | Total 100 analysed ears before crossover; 12 ears crossed over to the alternative treatment (8/50 TSP to gentamicin; 4/50 gentamicin to TSP): a) 50 CSOM (25 TSP, 25 gentamicin); 7 ears then crossed over (2 from gentamicin to TSP, 5 from TSP to gentamicin) b) 10 postoperative and mastoid cavity infections (5 TSP, 5 gentamicin); 3 ears then crossed over (3 from TSP to gentamicin) c) 16 subacute otitis media (8 TSP, 8 gentamicin); 2 ears then crossed over (2 from gentamicin to TSP) d) 24 external otitis (12 TSP; 12 gentamicin) 0 ears crossed over. | Not separate in review: type of infection was the principal criteria for randomisation (minimisation), but unclear whether this relates to diagnosis or bacteriology. But results were given by diagnosis separately in trial publication (for number of ears). |

| Gyde 1981 | 1) Otorrhoea from a) recurrent otitis media with tympanic membrane perforation (CSOM); b) infected mastoid cavities and post‐operative tympanoplasties; c) subacute otitis media; d) external otitis. 2) Presence of gram‐negative or gram‐positive organisms from a specified list. | 1) Acute otitis media 2) 'Unsafe' ears (active atticoantral disease, with adjacent area extension) | 13/68 ears were paediatric (< 12 years old), 12/68 ears were geriatric (> 70 years old). Concurrent medications, such as analgesics and decongestants etc were allowed. Exclusion criteria ‐ treatment related: 1) History of sensitivity to any components of the trial drugs. 2) Use of extensive ototopical corticosteroid preparations within the past four weeks. 3) Previous use of ototoxic drug therapy. 4) Use of oral or parenteral antibiotics within two weeks before study entry. 5) Unable to continue the proposed length of treatment or return for follow‐up visits due to distance or inconvenience. Exclusion criteria ‐ other: 1) Pregnant or lactating. 2) Tuberculosis, fungal or viral diseases. | Disease duration (for all diagnoses) ranged from just under 1 month to 5 years. | Indicated; Required for inclusion: Presence of gram‐negative or gram‐positive organisms from a specified list. | Not reported | Numbers for analysed ears (68 total: 35 TSP, 33 TP) a) 27 CSOM (13 TSP, 14 TP); b) 6 infected mastoid cavities and post‐operative tympanoplasties (2 TSP, 4 TP); c) 4 subacute otitis media (2 TSP, 2 TP); d) 31 external otitis (18 TSP, 13 TP). | Not separate in review: randomisation not reported to stratify by diagnosis. But results were given by diagnosis separately in trial publication. |

| Jaya 2003 | Actively discharging CSOM with moderate to large central perforation (i.e. active CSOM‐tubotympanic disease). | 1) Cholesteatoma 2) Aural polyp 3) Impending complications of CSOM | Other inclusion criteria: 1) Older than 10 years Exclusion criteria ‐ treatment related: 1) Known allergy to iodine or fluoroquinolone 2) Prior systemic or topical antibiotic therapy within 10 days of study entry Exclusion criteria ‐ other 1) Debilitating illness (e.g. diabetes mellitis, tuberculosis, renal failure or AIDS) | Total duration of disease: </= 5 years: n = 13 > 5 years: n = 27 Current episode of discharge was < 2 weeks for many participants: <1 week: n = 15 1 to 4 weeks: n = 20 > 4 weeks: n = 5 The trialists reported that this duration did not significantly alter the outcome in both treatment groups. | Indicated; Not required for inclusion: 8/40 swabs did not yield potential bacterial pathogen | Status of middle ear at baseline (number of participants): 20 hyperemic 18 pale and edematous 2 granular | None specified ‐ see otitis exclusions | n/a |

| Kasemsuwan 1997 | 1) Perforated tympanic membrane for longer than 3 months; 2) Mucopurulent otorrhoea (Assessed on microscopic examination) | 1) Cholesteatoma 2) Underlying diseases | Other inclusion criteria: 1) Adult (age range was 21 to 66) Exclusion criteria ‐ treatment related: 1) Receiving antibiotics in the previous two weeks and during the study. Exclusion criteria ‐ other: 1) Pregnant women 2) Underlying diseases | Perforated tympanic membrane for longer than 3 months | Indicated; Not required for inclusion: no bacteria were isolated for 26% of participants | Not reported | Not specified ‐ see otitis exclusions | n/a |

| Kaygusuz 2002 | Chronic suppurative otitis media with: 1) perforated eardrum, and 2) discharge in the ears for > 3 months | 1) Suspected or confirmed cholesteatoma (on otoscopy) 2) Previous history of ear surgery | Other inclusion criteria: None reported other than adults with CSOM (age range was 18 to 60 years, mean, (SD) 31 (+/‐11.5) years) Exclusion criteria ‐ treatment related: 1) Allergy to aminoglycosides or fluoroquinolones Exclusion criteria ‐ other: 1) Under 18 years old 2) General health problems | Discharge for > 3 months (average duration was 44.4 years +/‐ 40.9 months; range 3 to 10 years) | Indicated; Not required for inclusion: 5.8% of pre‐treatment cultures were negative | Not reported | Not specified ‐ see otitis exclusions. | n/a |

| Lorente 1995 | Simple chronic otitis media in the suppurative phase (CSOM): purulent otitis of > 3 months duration, with perforated tympanic membrane. | 1) Cholesteatoma or attic disease 2) Otomycosis 3) Bilateral hypoacusia higher than 60 dB | Inclusion criteria ‐ other: 1) Age 18 to 65 (mean 42 years) 2) Either gender 3) No evidence of physical or psychological (psychiatric) illness, with laboratory tests (biochemical and haematological) within reference ranges 4) Consent to participate Exclusion criteria ‐ treatment related: 1) Topical or systemic antibiotic use in the previous 48 hours 2) Allergy to quinolones or aminoglycosides Exclusion criteria ‐ other: 1) Pregnant or breast feeding 2) Severe kidney or liver deficiency | Purulent otitis of > 3 months duration | Indicated: Not specified in inclusion criteria: 304 microorganisms isolated before treatment were reported | Not reported | Not specified ‐ see otitis exclusions | n/a |

| Macfadyen 2005 | 1) Purulent aural discharge for 14 days or longer, with pus seen in the external canal on otoscopy 2) Perforated tympanic membrane (on otoscopy) | Other ear problems: 1) Pre‐existing disease, e.g. otomycosis, polyp, impacted foreign body, or previous ear surgery 2) Complicated otitis media, e.g. cholesteatoma, mastoiditis, requires treatment other than study treatment 3) Anatomical abnormalities | Inclusion criteria ‐ other: 1) School children (enrolled at Kisumu rural primary schools visited) 2) Age five years or older (range was 4 to 19 years) 3) Informed consent (parental consent for affected children; school staff and parent‐teacher‐association representatives consented to school participation). Exclusion criteria ‐ treatment related: 1) Treated for ear infection or received antibiotics for any other disorder in the previous 2 weeks 2) Allergy to study drugs. | Purulent aural discharge for 14 days or longer | Assessed but results not provided Not required for inclusion | Not assessed | No ‐ see otitis exclusions | n/a |

| Tutkun 1995 | History of purulent otorrhoea lasting > 1 year | Cholesteatoma | Inclusion criteria ‐ treatment related: 1) All participants stopped taking any medication at least 10 days prior to treatment. Inclusion criteria ‐ other: 1) Informed consent. Exclusion criteria ‐ treatment related: 1) History of allergy to fluoroquinolone derivatives or aminoglycosides, or to topical agents 2) Did not use the topical solutions regularly, or had taken any other medication during the study. Exclusion criteria ‐ other: 1) Younger than 9 years 2) History of general health problems. | History of purulent otorrhoea lasting > 1 year | Indicated Not specified in inclusion criteria: 4 participants had normal flora | Not reported | Not specified | n/a |

| Van Hasselt 1997 | CSOM ('typically... affected ears were filled with mucoid pus.... Most perforations were medium or large. Granulations were present in most cases') | Not reported | Inclusion criteria ‐ other: Children Exclusion criteria: Not reported. | Not specified | Not specified | Not reported | Not specified | n/a |

| Van Hasselt 1998 | > 2 months CSOM for inclusion as an active ear (CSOM not described) | Not reported | Participants were mainly children. Exclusion criteria: 1) Uncooperative with suction cleaning | > 2 months CSOM | Not specified | Not reported | Not specified | n/a |

| Van Hasselt 2002 | CSOM (not described) | Not reported | Other eligibility criteria: Not reported | Not specified | Not specified | Not reported | Not specified | n/a |

For binary data, we combined trials using relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). We combined trials with continuous data using the weighted mean difference (WMD) and its 95% confidence interval. Where data have been reported using medians and ranges, or there is evidence of skewed data, we reported medians and ranges where possible (dividing mean by the standard deviation (SD); results of < 1.64 indicate a positive skew). If continuous data were reported using geometric means, we combined the findings on a log scale and report on the original scale.

Quinolone and non‐quinolone topical antibiotic treatments are not combined across trials. This was done to avoid counting patients in the antiseptic arm twice for trials that compared a quinolone with a non‐quinolone and an antiseptic. There is also clinical interest in the difference in effectiveness of quinolones compared to non‐quinolones, as quinolones are thought to be more effective and safer but more expensive.

Where heterogeneity is considered to be present, and it remained clinically appropriate to combine data, we also used the DerSimonian and Laird random‐effects model, and reported both fixed‐effect and random‐effects results.

The primary analysis is of all eligible studies. If a sufficient number of trials is available for future updates (not available for each comparison in this version of the review), we will explore whether heterogeneity can be explained using subgroup analyses or meta‐regression for the following factors: age (under 16, and adults 16 years or older), associated mopping (dividing studies into those with some form of ear toilet, and those without), co‐interventions (dividing studies into those with treatment comparison alone, and those with treatment comparison in combination with other co‐interventions), and methodological quality (initially excluding studies of the poorest quality). Sensitivity analyses will also be used to explore methodological quality (notably adequate concealment), and trial design (e.g. cluster randomisation). We will display the results for each sensitivity analysis according to the subgroups within each methods category.

The sensitivity analysis will include the following, as outlined in the statistical guidelines in the Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Group 'Guidelines for Reviewers' (CochraneENTGuideline updated November 2000).

(1) Repeat the analysis excluding unpublished studies (if any). (2) Repeat the analysis excluding studies of the lowest quality (already done if there is heterogeneity). (3) If there are one or more very large studies, we will repeat the analysis excluding these, to investigate how much they dominate the results. (4) Repeat the analysis excluding studies where people with CSOM are only a subgroup of the participants included in the study, for example, those that enrol people with otitis externa, draining surgical cavities or acute otitis media, as well as CSOM.

Within this version of the review, trials where people with CSOM are only a subgroup of the participants included in the study are identified ‐ see Table 7.

For this version of the review, we visually examined forest plots, in conjunction with the chi2 test, using a 5% level of statistical significance, and the I2 statistic. The I2 statistic describes the percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (chance). A value greater than 50% may be considered substantial heterogeneity (Deeks 2004). There were insufficient trials to investigate publication bias using funnel plots; this may be done in further updates of the review.

Results

Description of studies

Search results

The electronic searches identified 649 citations in August and September 2003, plus 698 citations in March 2005, including four unpublished trials. Three additional trials were already known to the authors: van Hasselt 1997; van Hasselt 1998; van Hasselt 2002. Macfadyen 2005 was also already known to the authors. Trials with duplicate publications were identified and referred to under the main trial publication. Full texts of 127 trials were reviewed, and 14 included as eligible for this review ‐ see breakdown of numbers below. We attempted to include all relevant studies regardless of language.

127 trials: full texts obtained for eligibility assessment (117 from the above sources, plus ten from reference lists and other searches). Of these, 85 were in English only, three had English and non‐English publications, and 39 were in non‐English languages only.

105 trials excluded: 74 English only, one English and non‐English language, 30 only available in non‐English language.

Eight trials awaiting assessment: two English only [Nawasreh 2001 is awaiting a response from the author as to whether this is the same trial as another trial already included in this review (Tutkun 1995); McKelvie 1975 is awaiting full assessment for probable inclusion], and six trials only available in non‐English language, awaiting translation to determine eligibility.

14 trials included: nine English only, two English and non‐English language, three only available in non‐English language.

The Characteristics of excluded studies table outlines reasons for excluding studies following review of their full texts. The Characteristics of included studies table provides information on the included trials; also see tables: Table 6 (Methodological quality of included studies); Table 8 (Bilateral Disease: Numbers for Ears versus Participants); Table 7 (Participant eligibility criteria, including CSOM diagnostic criteria); Table 9 (Intervention regimens used); Table 10 (Outcomes assessed).

Table 3.

Bilateral disease: numbers for ears versus participants

| Study ID | # of particpants | # of ears | % bilateral cases | Handling bilat cases | Results: pt or ears? |

| Browning 1983a | 75 randomised ‐ all treatments; not reported by group 51 analysed: 18 topical antibiotics 20 topical antiseptics * 13 systemic antibiotics; not included in this review * 19/51 (37%) were post modified radical mastoidectomy ‐ numbers and results were not presented separately. | Not reported | Not reported | One ear was chosen at random by the pharmacist (method of choice unknown). | Participants |

| Clayton 1990 | Not reported | Randomised ears: 139 total: 20 central perforation; 30 mastoid cavity; 89 otitis externa Completed (analysed) + excluded cases: Total: 102 completed (42 antiseptic; 60 antibiotic) +37 excluded; Central perforation: 15 completed (4 antiseptic; 11 antibiotic) + 5 excluded; Mastoid cavity: 21 completed (13 antiseptic; 8 antibiotic) + 9 excluded; Otitis externa: 66 completed (25 antiseptic; 41 antibiotic) + 23 excluded | Not reported | Unclear ‐ report for ears only, but baseline characteristics table uses term 'patients' instead, although totals match number of ears reported in text. | Ears? But baseline characteristics table uses term 'patients' (text uses 'ears'). |

| Fradis 1997 | 51 randomised participants; 45 analysed | 60 randomised ears (20 per treatment group) 54 analysed ears: 19 ciprofloxacin 18 tobramycin 17 Burow aluminium acetate | Randomised bilateral rates: 9/51 (17.6%) Analysed bilateral rates: 9/41 (20.0%). | Treated both ears (each ear given a different bottle in bilateral cases), and report number of ears. | Ears |

| Gyde 1978 | Randomised participants: not reported Analysed participants before crossover (all diagnoses reported only): 91 total; 43 TSP; 48 gentamicin. Analysed participants crossed over to other treatment (all diagnoses): 11/91 total; 7/43 from TSP to gentamicin; 4/48 from gentamicin to TSP. NB the trialists reported the combined crossover plus pre‐crossover numbers. | Randomised ears: not reported Analysed ears before crossover: 100 total (50 TSP; 50 gentamicin); 50 CSOM (25 TSP; 25 gentamicin); 10 post‐operative and mastoid cavity infections (5 TSP; 5 gentamicin); 16 subacute otitis media (8 TSP; 8 gentamicin); 24 otitis externa (12 TSP; 12 gentamicin). Analysed ears crossed over to other treatment: 12/100 total (8/50 from TSP to gentamicin; 4/50 from gentamicin to TSP); 7/50 CSOM (5/25 from TSP to gentamicin; 2/25 from gentamicin to TSP); 3/10 post‐operative and mastoid cavity infections (3/5 from TSP to gentamicin); 2/16 subacute otitis media (2/8 from gentamicin to TSP); 0/24 otitis externa. NB the trialists reported combined pre‐ plus post‐crossover numbers. Where possible, we have used pre‐crossover cases only. | Randomised participants: rates not reported Analysed participants bilateral rates (all diagnoses only): Before crossover: Total: 9/91 (9.9% bilateral); TSP: 7/43 (16.3% bilateral); Gentamicin: 2/48 (4.2% bilateral). Crossed over to alternative treatment: Total: 1/11 (9% bilateral); TSP to gentamicin: 1/7 (14% bilateral); Gentamicin to TSP: 0/4 (0% bilateral). ie this crossover participant is counted 4 times in the combined figures presented by the trialists (twice per treatment). | Both ears treated and analysed separately ‐ reported number of ears | Ears |

| Gyde 1981 | 60 participants were eligible and included in the analyses Not available by treatment group or diagnosis. | Eligible ears included in the analyses: 68 total (35 TSP; 33 TP); 27 CSOM (13 TSP; 14 TP); 6 post‐operative and mastoid cavity infections (2 TSP; 4 TP); 4 subacute otitis media (2 TSP; 2 TP); 31 otitis externa (18 TSP; 13 TP) | Total: 8/60 (13.33%) Not available by treatment group or diagnosis. | Treated both eligible ears and report number of ears. | Ears |

| Jaya 2003 | 40 randomised participants (21 ciprofloxacin; 19 PVP‐I ) 36 assessed at week 4 (20 ciprofloxacin; 16 PVP‐I) | Not reported; but only 40 ear swabs taken at baseline | Not reported | Unclear ‐ reported at participant level. | Participants |

| Kasemsuwan 1997 | Main text states participants: 50 randomised 35 completed study and analysed (19 ciprofloxacin; 16 normal saline) | Abstract states ears: 50 ears randomised 35 completed study and analysed | Not reported | Unclear ‐ used term 'ears' in abstract, but mostly 'patients' in main text. | Participants? 'Participant' in main text, but used term 'ears' in abstract. |

| Kaygusuz 2002 | 80 participants included and analysed (20 per treatment group; i.e. 40 for this review) | 103 ears included (not reported by treatment group) | 23/80 (28.75%) | Appears to have taken success when both ears had resolved only (treatment was successful when there was no discharge). | Participants |

| Lorente 1995 | 308 analysed participants (159 ciprofloxacin; 149 gentamicin) Numbers originally randomised, not provided | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Participants |

| Macfadyen 2005 | 427 randomised participants (216 ciprofloxacin; 211 boric acid) 394 analysed for resolution at four weeks (196 ciprofloxacin; 198 boric acid) | 533 randomised ears (264 ciprofloxacin; 269 boric acid) | Rates for randomised participants: Total: 106/427 (25%) Ciprofloxacin: 48/216 (22%) Boric acid: 58/211 (27%) | Report at participant level. Both ears treated and assessed for bilateral cases ‐ success when both ears had resolved or healed. Sensitivity analysis conducted ‐ success for bilateral cases when either or both ears resolved or healed. Audiometry results were averaged over the study ear(s) for one overall reading. | Participants |

| Tutkun 1995 | 44 analysed participants (24 ciprofloxacin; 20 gentamicin) 40 analysed for hearing (20 ciprofloxacin; 20 gentamicin) (Ozagar 1994) | Not reported | Not reported | Unclear ‐ reported at participant level; bilateral disease or numbers of ears not discussed | Participants |

| van Hasselt 1997 | 96 children randomised: 12 ofloxacin; 38 neomycin/polymyxin B 46 acetic acid/spirit 69 children completed and included in analysis: 11 ofloxacin 30 neomycin/polymyxin B 28 acetic acid/spirit | Number ears randomised: not reported 93 ears included in analysis: (or 88?) 14 ofloxacin 40 neomycin/polymyxin B (35 in Van Hasselt 2002 paper) 39 acetic acid/spirit. | Randomised rates: not available Analysed participants: Total: 24/69 (34.78%) Ofloxacin: 3/11 (27.27%) Neomycin/polymyxin B: 10/30 (33.33%) (or 5/30, 16.67% from Van Hasselt 2002 publication) Acetic acid/spirit: 11/28 (39.29%) | Treated both ears and report % ears dry. CBM Report: provided number and proportion of ears dry and wet at each visit. 2002 paper: reported proportion of ears dry at two weeks. | Ears |

| van Hasselt 1998 | 107 participants randomised Number analysed: not reported | 151 randomised ears Analysed ears: 139 ears at week 1 138 ears at week 2: 32 ofloxacin twice daily; 39 ofloxacin once weekly; 36 neomycin polymyxin B twice daily; 31 neomycin polymyxin B once weekly. 128 ears at week 8. | Total randomised: 44/107 (41.12%) Analysed participants: not available | Report proportion of analysed ears dry; numbers of ears per group reported for week two only. | Ears |

| van Hasselt 2002 | Not reported | 253 analysed ears: 79 ofloxacin + HPMC 91 povidone iodine + HPMC 83 HPMC | Not reported | Reported % of number of ears dry. | Ears |

Table 4.

Intervention regimens used

| Study ID | Intervention | Strength | Dose and frequency | Duration | Ear Toilet | Concurrent meds |

| Do topical antibiotic eardrops work? | ||||||

| Quinolone versus placebo: | ||||||

| Kasemsuwan 1997 | 1) Quinolone: ciprofloxacin in saline solution 2) Placebo: normal saline solution | 1) Ciprofloxacin: 250 microgram/mL 2) Saline: n/a | Both treatments: 5 drops three times daily. | Both treatments: At least 7 days. | Both groups: Ear cleaning at each visit (treatment days 1, 4 and 7). | Excluded if received antibiotics in the previous two weeks or during the study. |

| van Hasselt 2002 | 1) Quinolone: ofloxacin in HPMC 2) Placebo: HPMC HPMC = hydroxypropyl methyl‐cellulose (hypromellose) ‐ a treatment delivery vehicle. | 1) 0.075% Ofloxacin in 1.5% HPMC 2) 1.5% HPMC | All treatments: 1 single topical application after suction cleaning. | Both treatments: Once only. | Both groups: Suction cleaning once. | Not reported. |

| Which antibiotic eardrops work best? | ||||||

| Non‐quinolone versus non‐quinolone | ||||||

| Gyde 1978 | 1) Non‐quinolone: trimethoprim‐sulfacetamide‐polymyxin B (TSP) (Burroughs Wellcome Ltd). 2) Non‐quinolone: gentamicin sulphate (Garamycine) | 1) 0.1% TSP (Trimethoprim 1 mg/mL; Polymyxin B 10,000 U/mL; Sulfacetamide 5mg/mL). 2) 0.3% gentamycin sulphate | Both treatments: 8 drops twice daily (morning and evening). | Both treatments: Depended on clinical and bacteriological response: Up to 3 weeks initially, plus 3 weeks if required. Failed ears or not dry at 6 months crossed over to the other treatment for 3 weeks; 6 month follow‐up as before: 11 participants (12 ears; 7 CSOM ears). Average duration (including crossovers) (days): All successfully treated ears: TSP 19.3 days (range 7 to 32) (N = 46); gentamicin 21.7 days (range 10 to 37) (N = 51). CSOM: TSP 16.4, gentamicin 22.8; Post‐operative or mastoid infections: TSP 24.0, gentamicin 24.3; Subacute otitis media: TSP 21.3, gentatmicin 22.7 Otitis externa: TSP 17.1, gentamicin 17.5. | Both groups: Suction and dry mopping before each treatment application. Pneumatic otoscope sometimes also used to ensure the eardrops reached the middle ear and mastoid cavity. | Two‐week washout period if used any antibiotics before study entry. Excluded if used high doses of ototopical corticosteroids, or ever used ototoxic drug therapy. |

| Gyde 1981 | 1) Non‐quinolone: Trimethoprim‐ sulfacetamide‐ polymyxin B (TSP) 2) Non‐quinolone: Trimethoprim‐ polymyxin B (TP) | 1) 0.1% TSP 2) 0.1% TP Concentrations of treatment components: Trimethoprim 1 mg/mL; Polymyxin B 10,000 U/mL; Sulfacetamide 5 mg/mL. | Both treatments: 8 drops twice daily (morning and night). | Both treatments: Up to 14 days maximum, depending on response to treatment and bacterial culture results. | Both groups: Suction and dry mopping before each treatment application. Pneumatic otoscope sometimes also used to ensure the eardrops reached the middle ear and mastoid cavity. | Two week washout period if used any antibiotics before inclusion. Excluded if used extensive ototopical corticosteroids within 4 weeks, or ever used ototoxic drug therapy. Concurrent medications such as analgesics and decongestants etc were allowed. |

| Quinolone versus non‐quinolone | ||||||

| Fradis 1997 | 1) Quinolone: ciprofloxacin hydrochloride solution 2) Non‐quinolone: tobramycin | 1) Ciprofloxacin: Not specified 2) Tobramycin: Not specified | All treatments: 5 drops, 3 time daily. | All treatments: 3 weeks. | Not specified. | All other medication discontinued two weeks before study entry. (34 participants previously received systemic antibiotics; 12 had used neomycin‐polymyxin B eardrops without success). |

| Kaygusuz 2002 | 1) Quinolone: ciprofloxacin hydrochloride 2) Non‐quinolone: tobramycin | 1) 0.3% Ciprofloxacin hydrochloride 2) 0.3% Tobramycin | All treatments: 2 drops 3 times daily. | All treatments: 3 weeks. | All groups: Aspiration once daily. | Not reported. |

| Lorente 1995 | 1) Quinolone: ciprofloxacin 2) Non‐quinolone: gentamicin | 1) 0.3% Ciprofloxacin 2) 0.3% Gentamicin | Both treatments: 5 drops (0.75 mg) 3 times daily. | Both treatments: 8 days (awaiting confirmation that this was not continued to day 30). | Not specified. | Excluded if received antibiotic treatment (topical or systemic) in the last 48 hours. |

| Tutkun 1995 | 1) Quinolone: ciprofloxacin hydrochloride 2) Non‐quinolone: gentamicin sulfate | 1) Ciprofloxacin hydrochloride: 200 microgram/mL 2) Gentamicin sulfate: 5 mg/mL | Both treatments: 5 drops 3 times daily. | Both treatments: 10 days. | Not specified. | All other medication stopped at least 10 days prior to treatment. Excluded if used any other medication during the study. |

| van Hasselt 1997 | 1) Quinolone: ofloxacin (Exocin R from Allergan) 2) Non‐quinolone: neomycin‐polymyxin B | 1) 0.3% Ofloxacin; 2) 0.5% Neomycin, 0.1% polymyxin B | All treatments: 3 drops, 3 times daily. | All treatments: 2 weeks. | All groups: Suction cleaning at the beginning of the trial, and at weeks 1 and 2 visits. | Not reported. |

| VH 1998 daily | 1) Quinolone: ofloxacin 2) Non‐quinolone: neomycin‐ polymyxin B | 1) 0.3% Ofloxacin 2) Neomycin‐ polymyxin B: not specified | Both treatments: 6 drops twice daily. | All treatments: 2 weeks. | All groups: Once weekly suction cleaning. | Not reported. |

| VH 1998 weekly | 1) Quinolone: ofloxacin 2) Non‐quinolone: neomycin‐ polymyxin B | 1) 0.3% Ofloxacin 2) Neomycin‐ polymyxin B: not specified | Both treatments: Once weekly. | All treatments: 2 weeks. | All groups: Once weekly suction cleaning. | Not reported. |

| Do topical antibiotics work better than topical antiseptics? | ||||||

| Non‐quinolone versus antiseptic | ||||||

| Browning 1983a | 1) Non‐quinolone: chloramphenicol (Chloromycetin), or gentamicin (Genticin) (self treated). Choice of antibiotics depended on sensitivity of bacterial isolated at baseline. 2) Antiseptics: insufflation of boric acid and iodine powder after aural toilet (otologist treated). | 1) Antibiotics: not specified 2) Antiseptic: not specified | 1) Topical Antibiotics (self treat): a) Chloramphenicol: 1 or 2 drops, 3 times daily; b) gentamicin: 3 or 4 drops, 4 times daily. 2) Antiseptic: once weekly (insufflation after aural toilet, by otologist) (dose not reported). | All treatments: 4 weeks. | All groups: Weekly aural toilet by otologist, using microscopic vision and suction aspiration when necessary. | Not reported. |

| Clayton 1990 | 1) Non‐quinolone: gentamicin sulphate 2) Antiseptic: aluminium acetate | 1) 0.3% Gentamicin sulphate 2) 8% Aluminium acetate | All treatments: 5 drops, 3 times daily. | All treatments: 3 weeks. | All groups: Self mopping before each treatment administration. | No antibiotics in the preceding 3 weeks. |

| Fradis 1997 | 2) Non‐quinolone: tobramycin 3) Antiseptic: Burow aluminium acetate solution | 2) Tobramycin: Not specified 3) 1% Aluminium acetate (weak antiseptic, used as a "placebo" by the trialists). | All treatments: 5 drops, 3 times daily. | All treatments: 3 weeks. | Not specified. | All other medication discontinued two weeks before study entry. (34 participants previously received systemic antibiotics; 12 had used neomycin‐polymyxin B eardrops without success). |

| van Hasselt 1997 | 2) Non‐quinolone: neomycin‐polymyxin B 3) Antiseptic: acetic acid in spirit and glycerin | 2) 0.5% Neomycin, 0.1% polymyxin B 3) 2% Acetic acid in 25% spirit and 30% glycerin | All treatments: 3 drops, 3 times daily. | All treatments: 2 weeks. | All groups: Suction cleaning at the beginning of the trial, and at weeks 1 & 2 visits. | Not reported. |

| Quinolone versus antiseptic | ||||||

| Fradis 1997 | 1) Quinolone: ciprofloxacin hydrochloride solution 3) Antiseptic: Burow aluminium acetate solution | 1) Ciprofloxacin: Not specified 3) 1% Aluminium acetate (weak antiseptic, designated as the "placebo group" by the trialists). | All treatments: 5 drops, 3 time daily. | All treatments: 3 weeks. | Not specified. | All other medication discontinued two weeks before study entry. (34 participants previously received systemic antibiotics; 12 had used neomycin‐polymyxin B eardrops without success). |

| Jaya 2003 | 1) Quinolone: ciprofloxacin hydrochloride 2) Antiseptic: povidone (polyvinyl pyrrolidone)‐ iodine (PVP‐I, Betadine) | 1) 0.3% Ciprofloxacin hydrochloride 2) 5% Povidone iodine | All treatments: 3 drops three times daily. | All treatments: 10 days. | Both groups: Dry mopping before each treatment occasion. Aural suctioning performed before initial treatment for all participants, and at subsequent weekly visits if discharge was present. | No prior systemic or topical antibiotic therapy within 10 days of study entry. |

| Macfadyen 2005 | 1) Quinolone: ciprofloxacin hydrochloride (Ciloxan, from Alcon) 2) Antiseptic: boric acid in alcohol (powder from UK but manufactured locally) | 1) 0.3% Ciprofloxacin hydrochloride 2) 2% Boric acid in 45% alcohol | Both treatments: Drops given twice daily (morning registration and lunch time). Child‐to‐child treatment: older children trained to clean and treat infected ears (at school), under supervision of trained teachers. | Both treatments: 10 consecutive school days (ie excluding weekends). | Both groups: Dry mopping before each treatment administration. Dry mop only for weeks 2‐4 if persistent discharge at week 2. | Excluded if treated for ear infection or received antibiotics for any other disorder in the previous 2 weeks. |

| van Hasselt 1997 | 1) Quinolone: ofloxacin (Exocin R, from Allergan) 3) Antiseptic: acetic acid in spirit and glycerin | 1) 0.3% Ofloxacin 3) 2% Acetic acid in 25% spirit and 30% glycerin | All treatments: 3 drops, 3 times daily. | All treatments: 2 weeks. | All groups: Suction cleaning at the beginning of the trial, and at weeks 1 & 2 visits. | Not reported. |

| van Hasselt 2002 | 1) Quinolone: ofloxacin in HPMC 2) Antiseptic: povidone iodine in HPMC HPMC = hydroxypropyl methyl‐cellulose (hypromellose) ‐ a treatment delivery vehicle. | 1) 0.075% Ofloxacin in 1.5% HPMC 2) 1% Povidone iodine in 1.5% HPMC | All treatments: 1 single topical application after suction cleaning. | Both treatments: Once only. | All groups: Suction cleaning once. | Not reported. |

Table 5.

Outcomes assessed

| Study ID | CSOM Resolution | Healing | Time to resolution | Time to reappearance | Hearing improvement | Safety | Other outcomes? | Other notes | Participant or ears? |

| Browning 1983a | 1) Participants with active, mucoid or inactive ears after 4 weeks of treatment. | Participant | |||||||

| Clayton 1990 | 1) Improved ears (i.e. dry or discharge improved by a score of 2 or more) at treatment days 9 and 21. Scoring system for severity of infection: degree of otorrhoea and of oedema or oedematous mucosa. Numbers with complete cure not reported. Presented results for day 21 only. | 1) Antibiotic or antiseptic resistant bacterial strains at treatment days 9 and 21. (Reported resistant strains for 21 days.) 2) Compliance to treatment, monitored at assessments every 3 days. | Resolution reported as 'improved' or 'not improved'; complete cure not reported. Excluded participants who failed to attend clinics or failed to comply with treatment (exclusions per diagnosis reported but not by treatment group). | Unclear ‐ ears? | |||||

| Fradis 1997 | 1) Clinical efficacy: cessation of otorrhoea on microscopic examination 24 hours after end of 3 weeks treatment. Reported as cure, improvement or failure ‐ improvement has been grouped with failure for this review. | ** 1) Hearing assessment: audiology assessed before and 24 hours after 3 weeks treatment. Results were not reported. ** | 1a) Bacteriological efficacy: eradication, persistence or superinfection, 24 hours after end of treatment; Reported pre and post‐treatment microorganisms isolated (including fungi, Candida). 1b) Sensitivity of pre and post (24 hrs)‐treatment bacteria to ciprofloxacin and tobramycin. | Ears | |||||

| Gyde 1978 | 1) Ears with clinical cure or failure at 6 months: Success: dry ear within 3 weeks of treatment, or sufficiently improved after 3 weeks that 3 weeks further therapy allowed the discharge to stop; with negative post‐treatment culture; and no return of the same strain of causative organism within 6 months of stopping treatment. Failure: evidence of exudate after 3 weeks, with a positive culture and little hope of further improvement. Failures at 6 months were allocated the alternative treatment, and followed‐up for 6 months as before. Results at 6 months, before crossover, have been taken for this review. | 1) Mean duration of treatment (days). Reported for successful ears only; includes crossed over treatment times. | 1) Relapse | 1) Hearing assessment in 50 participants: pre and post‐treatment audiometry, with a follow‐up audiogram by a certified audiologist. Results for average hearing loss before and after treatment, average improvement, and variation in improvement, are reported for each treatment group and treatment + 'intervention' (unclear what this is ‐ possibly surgery). Post‐treatment observations were 3 to 12 months after medical treatment or surgery, to detect any delayed ototoxicity. Audiometry (or an assessment of impedence, or both) assessed for a subset of 50 subjects only. Results were not reported separately by diagnosis; all analysed cases are included in this review. | 1) Ototoxicity: pre and post‐treatment audiometry, with a follow‐up audiogram by a certified audiologist. Post‐treatment observations were 3 to 12 months after medical treatment or surgery, to detect any delayed ototoxicity. Audiometry (or an assessment of impedence, or both) assessed for a subset of 50 subjects only (not reported separately by diagnosis). 2) Adverse reactions: open‐ended question with further questioning for intensity of reaction. No specific or suggestive questions were asked. | 1) Bacteriology ‐ reported cure, improvement or failure according to pre‐treatment bacteria cultured; Results include crossed over cases. | Negative bacterial culture was included in the definition of cure. | Ears | |