Abstract

Background

Despite effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection remains associated with higher morbidity and mortality, driven, in part, by increased inflammation. Our objective was to identify associations between levels of plasma biomarkers of chronic inflammation, microbial translocation, and monocyte activation, with occurrence of non-AIDS events.

Methods

Participants (141 cases, 310 matched controls) were selected from a longitudinal observational trial; all were virally suppressed on ART at year 1 and thereafter. Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR), lipopolysaccharide binding protein (LBP), beta-D-glucan (BDG), intestinal fatty-acid binding protein, oxidized low-density lipoproteins, and soluble CD163 were measured pre-ART, after 1-year of ART, and pre-event. At each time point, conditional logistic regression analysis assessed associations of the biomarkers with events and adjusted for relevant covariates to calculate odds ratios (ORs) according to 1 interquartile range (IQR) difference.

Results

At all time points, higher levels of suPAR were associated with increased risk of non-AIDS events (OR per 1 IQR was 1.7 before ART-initiation, OR per 1 IQR was 2.0 after 1 year of suppressive ART, and OR 2.1 pre-event). Higher levels of BDG and LBP at year 1 and pre-event (but not at baseline) were associated with increased risk of non-AIDS events. No associations were observed for other biomarkers.

Conclusions

Elevated levels of suPAR were strongly, consistently, and independently predictive of non-AIDS events at every measured time point. Interventions that target the suPAR pathway should be investigated to explore its role in the pathogenesis of non–AIDS-related outcomes in HIV infection.

Keywords: non-AIDS mortality, viral suppression, suPAR, lipopolysaccharide binding protein, beta-D-glucan

Elevated soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor levels before antiretroviral therapy initiation after 1 year of suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy and pre-event were strongly and consistently predictive of non-AIDS events (including death, malignancy, and cardiovascular events/stroke) in this matched case-control study.

Despite effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection remains associated with morbidity and mortality due to non–AIDS-defining events, such as cardiovascular disease (CVD) and non–AIDS-defining malignancies [1–3]. Elevated markers of inflammation have been shown to predict non-AIDS events, including CVD, malignancies, diabetes, lung disease, neurocognitive impairment, and frailty [4–13]. Potential contributors to inflammation include translocation of bacterial/fungal products from the gut into the systemic circulation [14–18].

Most previous studies, including one conducted by Tenorio and colleagues, have focused on a handful of inflammatory markers (interleukin [IL]-6), coagulation (D-dimer), monocyte activation (sCD14), and T-cell activation/dysfunction [3, 4, 6, 11, 13]. Recently, more specific biomarkers have emerged that reflect gut epithelial dysfunction and microbial translocation. These novel biomarkers include beta-D-glucan (BDG) [14, 19], lipopolysaccharide binding protein (LBP) [12, 15], and intestinal fatty acid binding protein (I-FABP) [17]. However, direct linkages between these novel indices and clinical events in the setting of ART-suppressed HIV infection have not been demonstrated.

Another novel biomarker that may have predictive value in this setting is the soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR), a marker for monocyte, T-cell, and plasminogen activation [20–24]. In HIV infection, the urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) expression is upregulated on activated monocytes and T lymphocytes [25]. Higher pre-ART suPAR levels were recently associated with a spectrum of incident non-AIDS comorbidities as well as all-cause mortality during 7 years of follow-up in a cohort study in Denmark [26]. However, similar to soluble (s) CD163 (another marker of monocyte activation) [9, 10, 27] and also similar to oxidized (ox) low-density lipoproteins (LDL) [28, 29], higher suPAR levels are associated with traditional risk factors for non-AIDS events, such as smoking [30]. Therefore, a thorough evaluation in a matched case-control study adjusting for relevant confounders (eg, smoking) is needed to further elucidate the role of and relationships among these biomarkers in predicting non-AIDS events.

Our objective in this study was to identify associations between levels of these plasma biomarkers of chronic inflammation, microbial translocation, coagulation, and monocyte activation, measured prior to and during suppressive ART, with occurrence of non-AIDS events.

METHODS

Cohort and Samples

All 451 participants (141 cases with non-AIDS events, 310 matched controls), identified from prior Adult Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) studies, were ART naive when enrolled into an ACTG study, had a plasma HIV-1 RNA level of <400 copies/mL at week 48 after ART initiation, and maintained a plasma HIV RNA level of <400 copies/mL at all subsequent time points (isolated values ≥400 copies/mL were allowed if preceding and subsequent values were <400 copies/mL) [13]. Participants provided written informed consent, and institutional review board approval was obtained by each ACTG site of the respective parent studies.

Cases were defined as participants who had a myocardial infarction (MI) or a stroke, a non–AIDS-defining malignancy or serious bacterial infection, or died from a nonaccidental non–AIDS-related event [13]. The core team previously reviewed events. MI diagnoses accorded with standard ACTG definitions and reporting criteria [31]; criteria for non–AIDS-defining malignancies have been described elsewhere [3]. For each case, up to 3 controls were identified who had an endpoint-free follow-up time equal to or greater than that of the case; controls were matched on age (within 10 years; median, 45 years), sex (85% male), pre-ART CD4+ T-cell count (within 50 cells/mm3; median, 215 cells/mm3), ART regimen at week 48 (whether it contained a protease inhibitor or abacavir), and parent study, as outlined elsewhere [13].

Stored plasma specimens obtained from cases and controls at the following 3 time points were evaluated: before ART initiation (hereafter, baseline), 48–64 weeks after starting ART (hereafter, year 1), and the time point immediately preceding the event for cases and a similar time point for corresponding controls (hereafter, pre-event). The year 1 time point was chosen because by 48 weeks after ART, the slope of decline in activation had stabilized [32]. Plasma samples were available for 325 participants at baseline (111 cases and 214 controls), 418 participants at year 1 (134 cases and 284 controls), and 377 participants pre-event (122 cases and 255 controls).

At each time point, as part of their ACTG study, whole blood was obtained in tubes containing EDTA. Specimens were spun at 400 ×g for 10 minutes, and plasma was pipetted and spun again at 800 ×g for 10 minutes. Plasma was aliquoted, frozen, and stored at −70°C until assayed.

Laboratory Assays

In this study, we measured markers of microbial translocation (ie, LBP, BDG, I-FABP), oxLDL, and markers of inflammation/monocyte activation (suPAR, sCD163) at all 3 time points. BDG was measured by using the Fungitell assay at the Associates of Cape Cod, Inc., research laboratories (Associates of Cape Cod, Inc, East Falmouth, MA). The detection reagent is a biological cascade based on modified Limulus amebocyte lysate, a cellular extract from the North American horseshoe crab. suPAR levels were measured at the suPARnostic reference laboratory (Poznan, Poland; baseline samples) and at the Department of Medicine, Rush University (year 1 and pre-event samples) by using the suPARnostic enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit CE marked for clinical use (ViroGates, Copenhagen, Denmark), with a detection limit of 0.1 ng/mL, an intraassay variation of 2.75%, and an interassay variation of 9.17% [22, 25]. Levels of oxLDL were measured using ELISA (Mercodia Uppsala, Sweden) at the Funderburg Laboratory at Ohio State University; the intraassay variability was approximately 8% [29]. Cryopreserved plasma samples were thawed and measured in batch. Levels of IFAB, LBP, and sCD163 were measured using ELISA (Hycult Biotech Inc. cat. no. HK315, and R&D system cat. no. DC1630 and DY3078, respectively) at Case Western Reserve University, according to manufacturers’ instructions. All participating laboratories received a separated aliquot of plasma samples to avoid multiple freeze and thaw cycles, except for the suPARnostic laboratories, to which samples were forwarded after BDG measurements.

Statistical Analyses

Conditional logistic regression analysis was used to study the associations of biomarker levels (at each time point) with non-AIDS events. Effects are summarized in terms of the odds ratio (OR) per 1 interquartile range (IQR) on a log10-transformed scale [7]; each IQR was obtained from pooling cases and controls.

Adjusted models further controlled, individually, for HIV-disease measures (concurrent log-10 HIV RNA level at baseline or CD4+ T-cell counts at year 1 or pre-event), and the following potential confounders: chronic hepatitis B or C, smoking status, waist-to-hip ratio, clinician-diagnosed diabetes, clinician-diagnosed hypertension, use of antihypertensive or lipid-lowering agents, family history of MI, history of intravenous drug use [13], and estimated glomerular filtration rate [22]. Additional exploratory models adjusted for previously analyzed biomarkers interleukin-6 (IL-6), interferon-γ (IFN-γ)–inducible protein 10 (IP-10), soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor I (sTNFR-I), sTNFR-II, sCD14, D-dimer, as well as plasma CD4:CD8 ratio [13, 33]. Relationships among the biomarkers (suPAR, BDG, I-FABP, LBP, sCD163, oxLDL) and between these biomarkers and those evaluated by Tenorio et al [13] were also evaluated using Spearman correlations. This analysis was conducted among the controls because the proportion of cases in our study sample was higher than in the general population and dilution with cases may lead to results that do not reflect true associations. Changes from baseline to year 1 were assessed using the signed rank test. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4. P values <.05 were considered significant; no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons, but results were interpreted cautiously, with emphasis on effect sizes.

RESULTS

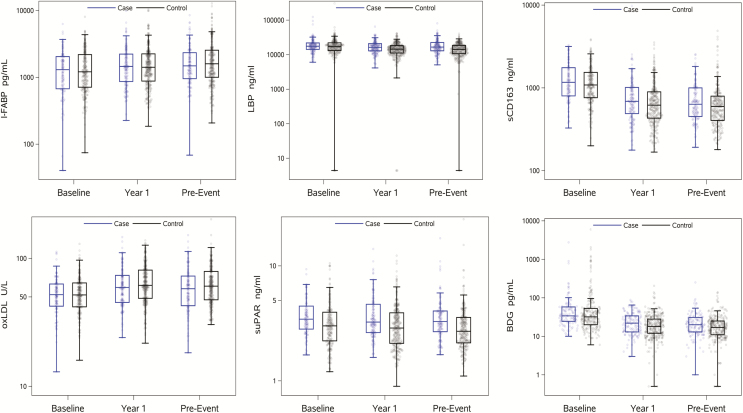

Among 141 cases, non–AIDS-defining events occurred at a median of 2.9 years (IQR, 1.7 to 4.6 years; range, 0.8 to 11.3 years) after ART initiation. Cases and the 310 controls had similar baseline demographic characteristics (Table 1). Figure 1 displays the distributions of the biomarkers at each time point, separately for cases and controls. Levels of all biomarkers changed significantly during the first year of ART in cases as well as controls (mostly decreases, all P < .01), with the exception of suPAR (P > .6 for cases and controls).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of All Cases and Controls at Baseline

| Characteristic | Case No.a (N = 141) | Control (N = 310) | Total (N = 451) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at parent study entry (years) | |||

| Range | 23–73 | 23–67 | 23–73 |

| Median (IQR) | 46 (40–53) | 44 (39–50) | 45 (39–51) |

| Regimens evaluated, by parent study | |||

| A384: (AZT + 3TC vs d4T + ddI) + (EFV vs NFV vs NFV + EFV) | 25 (18%) | 75 (24%) | 100 (22%) |

| A388: (AZT + 3TC vs d4T + 3TC) + (IDV vs NFV vs IDV + NFV) | 16 (11%) | 15 (5%) | 31 (7%) |

| A5014: NVP + [LPV/r vs (ABC + 3TC + d4T)] | 2 (1%) | 7 (2%) | 9 (2%) |

| A5095: AZT/3TC + (ABC vs EFV vs ABC + EFV) | 45 (32%) | 83 (27%) | 128 (28%) |

| A5142: (EFV + AZT/d4T + 3TC) vs (LPV/r + AZT/d4T + 3TC) vs (EFV + LPV/r) | 21 (15%) | 67 (22%) | 88 (20%) |

| A5202: (ABC/3TC vs TFV/FTC) + (ATV/r vs EFV) | 32 (23%) | 63 (20%) | 95 (21%) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 119 (84%) | 263 (85%) | 382 (85%) |

| Female | 22 (16%) | 47 (15%) | 69 (15%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White non-Hispanic | 74 (52%) | 150 (48%) | 224 (50%) |

| Black non-Hispanic | 51 (36%) | 87 (28%) | 138 (31%) |

| Hispanic (regardless of race) | 15 (11%) | 62 (20%) | 77 (17%) |

| Other | 1 (1%) | 11 (4%) | 12 (3%) |

| Baseline CD4+ T-cell count (cells/uL) | |||

| Range | 2–764 | 0–756 | 0–764 |

| Median (IQR) | 208 (87–334) | 217 (70–330) | 213 (75–331) |

| Baseline log10 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA (copies/mL)b | |||

| Range | 2.9–6.9 | 2.3–7.0 | 2.3–7.0 |

| Median (IQR) | 4.8 (4.4–5.3) | 4.8 (4.4–5.4) | 4.8 (4.4–5.4) |

| Chronic hepatitis B or C | 36 (26%) | 34 (11%) | 70 (16%) |

| Current or previous injection drug use | 20 (14%) | 30 (10%) | 50 (11%) |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | |||

| Range | 0.72–1.12 | 0.67–1.08 | 0.67–1.12 |

| Median (IQR) | 0.92 (0.89–0.96) | 0.92 (0.88–0.97) | 0.92 (0.89–0.97) |

| History of clinician-diagnosed diabetes | 11 (8%) | 15 (5%) | 26 (6%) |

| History of hypertension | 45 (32%) | 57 (18%) | 102 (23%) |

| Use of antihypertensive or lipid lowering agents | 31 (22%) | 41 (13%) | 72 (16%) |

| Current or past smoker | 106 (75%) | 170 (55%) | 276 (61%) |

| Family history of myocardial infarction | 30 (21%) | 45 (15%) | 75 (17%) |

Abbreviations: 3TC, lamivudine; ABC, abacavir; ATZ/r, ritonavir-boosted atazanavir; AZT, zidovudine; d4T, stavudine; ddI, didanosine; EFV, efavirenz; FTC, emtricitabine; IDV, indinavir; IQR, interquartile range; LPV/r, ritonavir-boosted lopinavir); NFV, nelfinavir; NVP, nevirapine; TFV, tenofovir.

aNon-AIDS events included death (n = 20), myocardial infarction/stroke (n = 41, including 3 fatal events), malignancy (n = 51, including 2 fatal), and serious bacterial infection (n = 37, including 3 fatal).

bIsolated human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA viral loads >400 copies/mL were observed in 6 cases and 8 controls at pre-event.

Figure 1.

Distribution of soluble markers of inflammation and coagulation among cases (blue) and controls (black) in specimens obtained at the visit before antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation (baseline), the visit approximately 1 year after ART initiation (year 1), and the visit immediately preceding the non–AIDS-defining event (pre-event). Jitter blots including median and interquartile range are displayed. For controls, all differences between baseline and year-1 were significant (ie, P < .05) except for soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor. Abbreviations: BDG, beta-D-glucan; I-FABP, intestinal fatty acid binding protein; LBP, lipopolysaccharide binding protein; oxLDL, oxidized low-density lipoproteins; sCD163, soluble CD163; suPAR, soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor.

Correlations Among Biomarkers

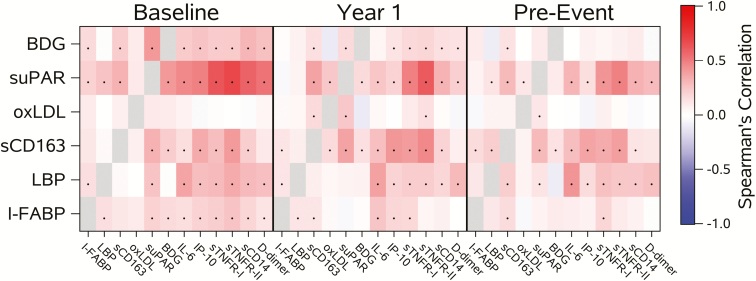

Figure 2 summarizes the Spearman correlations between biomarkers among the controls. At baseline, modest correlations were observed between suPAR and I-FABP, LBP, and sCD163 (r = 0.21 to 0.33). Baseline levels of suPAR were also correlated with BDG (r = 0.42; P < .001), and at year 1 suPAR was associated with sCD163 and oxLDL. suPAR levels were also associated with previously analyzed markers (IL-6, IP-10, sTNFR-I, sTNFR-II, sCD14, and D-dimer) with correlations between 0.47 and 0.69 at baseline, between 0.20 and 0.62 at year 1, and between 0.16 and 0.49 at pre-event. Scatterplots with corresponding correlations between biomarkers are displayed in Supplementary Figures 1–42.

Figure 2.

Heat map of Spearman correlations between biomarkers in controls. P values <.05 are indicated with a dot. Abbreviations: BDG, beta-D-glucan; I-FABP, intestinal fatty acid binding protein; LBP, lipopolysaccharide binding protein; oxLDL, oxidized low-density lipoproteins; sCD163, soluble CD163; suPAR, soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor.

Baseline (Pre-ART) Biomarker Levels and Non-AIDS Events

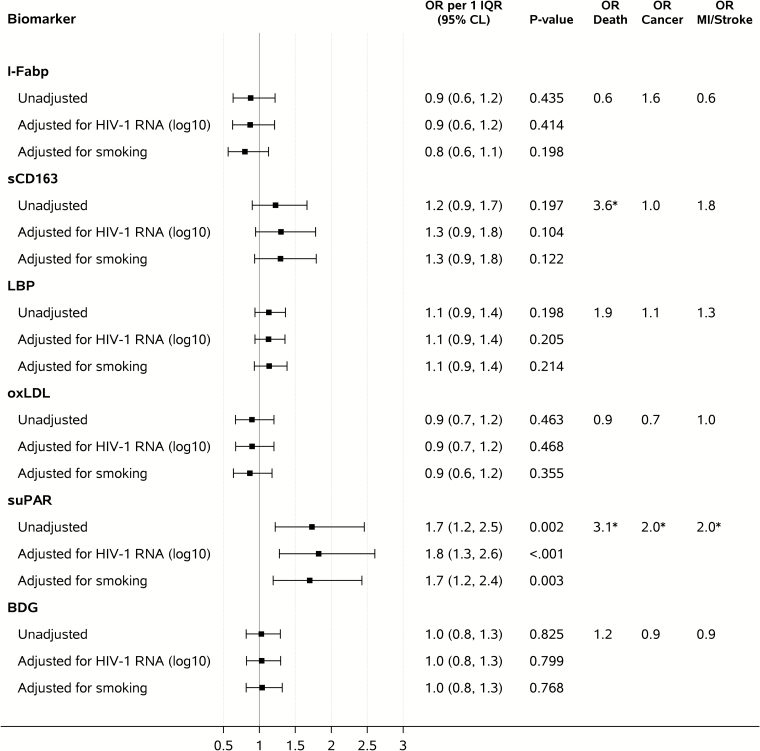

Figure 3 shows ORs for having a non–AIDS-defining event per 1 IQR of baseline biomarker level. Higher baseline levels of suPAR were associated with increased risk of non–AIDS-related events in unadjusted conditional logistic regression analysis (OR per 1 IQR, 1.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2–2.5; P = .002), while no significant associations were found for the other biomarkers examined. Subanalysis indicated that this association between suPAR and increased risk of non-AIDS events was particularly driven by those participants with CD4+ T-cell counts above the median (ie, >213 cells/µL; Supplementary Table 2). The association between suPAR and non-AIDS events remained unchanged after adjustment for confounders (Figure 3 and Supplementary Tables 1–3) and for other biomarkers determined in this cohort as part of this study and earlier (Table 2), with ORs per 1 IQR between 1.5 and 1.9. When different types of events were considered separately, higher baseline suPAR levels were associated with increased risk of death (n = 13 events; OR per 1 IQR, 3.1; 95% CI, 1.2–7.8; P = .018), malignancy (n = 26; OR per 1 IQR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.1–3.9; P = .032), and MI/stroke (n = 20; OR per 1 IQR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.0–3.8; P = .048).

Figure 3.

Biomarker levels at baseline and odds ratios of having a non–AIDS-defining event. Unadjusted analyses adjusted for the matching factors only. Adjusted analyses controlled also for concurrent log10 baseline human immunodeficiency virus RNA load or smoking. Abbreviations: BDG, beta-D-glucan; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; I-FABP, intestinal fatty acid binding protein; IQR, interquartile range; LBP, lipopolysaccharide binding protein; MI, myocardial infarction; OR, odds ratio; oxLDL, oxidized low-density lipoproteins; sCD163, soluble CD163; suPAR, soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor. *.01 ≤ P value < .05.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Conditional Logistic Regression Analysis for Soluble Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor Levels at Baseline, Year 1, and Pre-event and Odds Ratios of Having a Non–AIDS-Defining Event

| Type of Analysis | <25th Percentile | 25th–49th Percentile | 50th–74th Percentile | ≥75th Percentile | OR (95% CI) Associated With 1 Higher Level After log10 Transformation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | per 1 log10 | per 1 IQR | P Value | ||

| Baseline | ||||||||||

| Event no. | 15/75 (20%) | 26/76 (34%) | … | 32/75 (43%) | 33/77 (43%) | … | … | … | … | |

| Unadjusted | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.1 (1.0–4.7) | .791 | 3.6 (1.6–8.0) | .033 | 3.5 (1.5–8.0) | .055 | 11.9 (2.5, 58.2) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.5) | .002 |

| Adjusted for I-FABP (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.5 (1.1–5.5) | .889 | 4.3 (1.8–10.1) | .016 | 3.9 (1.7–9.2) | .052 | 13.2 (2.7, 65.0) | 1.8 (1.2, 2.5) | .002 |

| Adjusted for sCD163 (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.2 (1.0–4.9) | .765 | 3.8 (1.6–8.9) | .030 | 3.7 (1.5–8.9) | .050 | 13.5 (2.4, 75.6) | 1.8 (1.2, 2.6) | .003 |

| Adjusted for LBP (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.2 (1.0–4.8) | .934 | 3.4 (1.5–7.6) | .056 | 3.3 (1.5–7.7) | .068 | 10.8 (2.2, 53.0) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.4) | .003 |

| Adjusted for oxLDL (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.2 (1.0–4.7) | .823 | 3.6 (1.6–8.0) | .034 | 3.4 (1.5–7.9) | .061 | 11.6 (2.4, 56.3) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.4) | .002 |

| Adjusted for BDG (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.2 (1.0–4.8) | .766 | 3.6 (1.6–8.2) | .039 | 3.7 (1.6–8.9) | .045 | 15.3 (2.9, 81.9) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.6) | .001 |

| Adjusted for IL-6 (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.1 (1.0–4.7) | .823 | 3.1 (1.3–7.1) | .063 | 2.6 (1.1–6.2) | .278 | 6.1 (1.2, 32.0) | 1.5 (1.0, 2.2) | .032 |

| Adjusted for IP-10 (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.1 (1.0–4.6) | .804 | 3.5 (1.6–8.0) | .034 | 3.4 (1.4–8.0) | .081 | 11.7 (2.2, 62.9) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.5) | .004 |

| Adjusted for sTNFR-I (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.1 (0.9–4.5) | 1.000 | 3.2 (1.3–7.4) | .050 | 2.8 (1.1–7.1) | .241 | 8.4 (1.3, 56.0) | 1.6 (1.1, 2.4) | .028 |

| Adjusted for sTNFR-II (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.1 (0.9–4.5) | .981 | 3.2 (1.4–7.5) | .039 | 2.8 (1.1–7.1) | .255 | 9.2 (1.4, 62.0) | 1.6 (1.1, 2.5) | .022 |

| Adjusted for sCD14 (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.1 (0.9–4.5) | .880 | 3.1 (1.3–7.0) | .048 | 2.5 (1.0–6.0) | .350 | 6.2 (1.2, 33.4) | 1.5 (1.0, 2.2) | .034 |

| Adjusted for D-dimer (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.0 (0.9–4.3) | .919 | 3.0 (1.3–7.0) | .053 | 2.7 (1.1–6.4) | .200 | 7.2 (1.4, 38.2) | 1.5 (1.1, 2.2) | .020 |

| Adjusted for CD4:CD8 ratio | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.4 (1.1–5.4) | .864 | 4.1 (1.8–9.5) | .026 | 4.1 (1.7–9.7) | .033 | 14.3 (2.8, 72.3) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.6) | .001 |

| Year 1 | ||||||||||

| Event no. | 16/104 (15%) | 37/104 (36%) | … | 38/104 (37%) | 43/105 (41%) | … | … | … | … | |

| Unadjusted | 1.0 (ref.) | 3.0 (1.6–5.7) | .374 | 3.4 (1.7–6.7) | .140 | 4.1 (2.0–8.3) | .013 | 13.2 (3.7, 46.7) | 2.0 (1.4, 2.7) | <.001 |

| Adjusted for I-FABP (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 3.0 (1.6–5.7) | .374 | 3.4 (1.7–6.7) | .140 | 4.1 (2.0–8.3) | .013 | 13.2 (3.7, 46.7) | 2.0 (1.4, 2.7) | <.001 |

| Adjusted for sCD163 (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 3.0 (1.5–5.7) | .374 | 3.4 (1.7–6.9) | .143 | 4.1 (1.9–8.7) | .020 | 13.7 (3.4, 56.3) | 2.0 (1.4, 2.8) | <.001 |

| Adjusted for LBP (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.8 (1.5–5.4) | .424 | 3.3 (1.6–6.5) | .143 | 3.9 (1.9–7.9) | .017 | 13.0 (3.6, 47.2) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.7) | <.001 |

| Adjusted for oxLDL (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 3.2 (1.6–6.0) | .331 | 3.4 (1.7–6.9) | .180 | 4.5 (2.2–9.1) | .007 | 16.3 (4.4, 59.8) | 2.1 (1.5, 2.9) | <.001 |

| Adjusted for BDG (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 3.1 (1.6–5.9) | .251 | 3.2 (1.6–6.4) | .238 | 4.1 (2.0–8.2) | .014 | 12.3 (3.5, 43.4) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.7) | <.001 |

| Adjusted for IL-6 (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.7 (1.4–5.2) | .295 | 2.7 (1.3–5.5) | .311 | 3.4 (1.6–6.8) | .038 | 8.8 (2.4, 32.2) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.5) | .001 |

| Adjusted for IP-10 (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.9 (1.5–5.6) | .369 | 3.3 (1.7–6.7) | .141 | 4.0 (1.9–8.2) | .020 | 12.9 (3.4, 48.5) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.7) | <.001 |

| Adjusted for sTNFR-I (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.7 (1.4–5.2) | .263 | 2.8 (1.4–5.7) | .213 | 3.1 (1.4–6.6) | .111 | 7.6 (1.8, 32.4) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.5) | .006 |

| Adjusted for sTNFR-II (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.8 (1.4–5.3) | .299 | 3.0 (1.4–6.2) | .191 | 3.3 (1.5–7.5) | .086 | 10.3 (2.0, 52.5) | 1.8 (1.2, 2.8) | .005 |

| Adjusted for sCD14 (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.9 (1.5–5.6) | .376 | 3.3 (1.6–6.6) | .150 | 4.0 (1.9–8.1) | .017 | 12.1 (3.3, 44.5) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.7) | <.001 |

| Adjusted for D-dimer (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 2.8 (1.5–5.3) | .399 | 3.1 (1.5–6.2) | .182 | 3.8 (1.9–7.6) | .021 | 11.9 (3.3, 43.0) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.7) | <.001 |

| Adjusted for CD4:CD8 ratio | 1.0 (ref.) | 3.0 (1.6–5.7) | .361 | 3.4 (1.7–6.9) | .124 | 4.1 (2.0–8.2) | .017 | 12.9 (3.6, 46.1) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.7) | <.001 |

| Pre-Event | ||||||||||

| Event no. | 18/94 (19%) | 25/94 (27%) | … | 34/94 (36%) | … | 45/94 (48%) | … | … | … | … |

| Unadjusted | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.7 (0.8–3.3) | .256 | 2.6 (1.3–5.4) | .271 | 4.5 (2.2–9.3) | <.001 | 23.2 (5.2, 103) | 2.1 (1.5, 3.0) | <.001 |

| Adjusted for I-FABP (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.8 (0.9–3.5) | .303 | 2.6 (1.3–5.4) | .342 | 4.8 (2.3–10.0) | <.001 | 25.0 (5.6, 112) | 2.2 (1.5, 3.1) | <.001 |

| Adjusted for sCD163 (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.7 (0.9–3.4) | .230 | 2.7 (1.3–5.7) | .260 | 4.9 (2.2–10.6) | <.001 | 28.6 (5.5, 150) | 2.2 (1.5, 3.3) | <.001 |

| Adjusted for LBP (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.5 (0.7–3.1) | .257 | 2.3 (1.1–4.8) | .382 | 3.9 (1.9–8.1) | <.001 | 18.9 (4.1, 86.6) | 2.0 (1.4, 2.9) | <.001 |

| Adjusted for oxLDL (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.7 (0.9–3.4) | .278 | 2.8 (1.4–5.7) | .204 | 4.5 (2.2–9.2) | <.001 | 23.9 (5.3, 107) | 2.1 (1.5, 3.0) | <.001 |

| Adjusted for BDG (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.7 (0.8–3.4) | .319 | 2.5 (1.2–5.0) | .397 | 4.4 (2.2–9.2) | <.001 | 21.0 (4.6, 95.4) | 2.1 (1.4, 3.0) | <.001 |

| Adjusted for IL-6 (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.3 (0.6–2.6) | .213 | 2.0 (1.0–4.2) | .335 | 2.9 (1.4–6.3) | .007 | 9.7 (2.0, 47.2) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.5) | .005 |

| Adjusted for IP-10 (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.6 (0.8–3.3) | .284 | 2.5 (1.2–5.2) | .299 | 4.2 (2.0–8.8) | <.001 | 20.0 (4.4, 91.9) | 2.0 (1.4, 2.9) | <.001 |

| Adjusted for sTNFR-I (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.4 (0.7–2.8) | .231 | 2.2 (1.0–4.5) | .293 | 3.1 (1.4–6.8) | .006 | 10.7 (2.1, 54.9) | 1.8 (1.2, 2.6) | .005 |

| Adjusted for sTNFR-II (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.4 (0.7–2.8) | .270 | 2.2 (1.0–4.5) | .283 | 3.1 (1.4–6.9) | .011 | 10.5 (1.8, 59.5) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.6) | .008 |

| Adjusted for sCD14 (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.5 (0.8–3.1) | .317 | 2.3 (1.1–4.8) | .320 | 3.6 (1.7–7.7) | .002 | 14.6 (3.1, 68.7) | 1.9 (1.3, 2.7) | <.001 |

| Adjusted for D-dimer (log10) | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.6 (0.7–3.2) | .390 | 2.3 (1.1–4.9) | .323 | 3.5 (1.6–7.3) | .004 | 14.4 (3.2, 65.0) | 1.9 (1.3, 2.7) | <.001 |

| Adjusted for CD4:CD8 ratio | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.6 (0.8–3.2) | .238 | 2.5 (1.2–5.1) | .316 | 4.3 (2.1–8.9) | <.001 | 15.7 (3.1, 79.5) | 1.9 (1.3, 2.8) | <.001 |

Adjusted analyses controlled for all other biomarkers and CD4:CD8 ratio measured in this cohort as part of this study or earlier.

Abbreviations: BDG, beta-D-glucan; CI, confidence interval; I-FABP, intestinal fatty acid binding protein; IL-6, interleukin 6; IP-10, interferon–inducible protein 10; LBP, lipopolysaccharide binding protein; OR, odds ratio; oxLDL, oxidized low-density lipoproteins; sCD163, soluble CD163; sTNFR, soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor; suPAR, soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor.

Year 1 and Pre-event Biomarker Levels and Non-AIDS Events

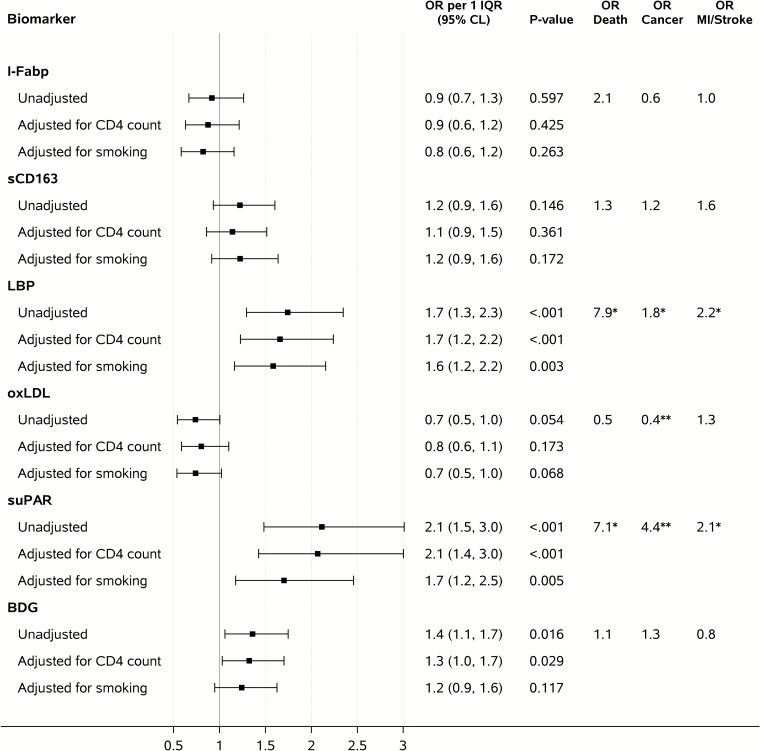

Figures 4 and 5 show ORs of having a non–AIDS-defining event per 1 IQR of year 1 (Figure 4) and pre-event (Figure 5) biomarker levels. Higher year 1 and pre-event levels of suPAR (year 1: OR per 1 IQR 2.0; pre-event: OR per 1 IQR, 2.1; both P < .001), BDG (year 1: OR per 1 IQR, 1.5; P = .008; pre-event: OR per 1 IQR, 1.4; P = .016), and LBP (year 1: OR per 1 IQR, 1.4; P = .016; pre-event: OR per 1 IQR, 1.7; P < .001) were associated with increased risk of non–AIDS-related events in unadjusted conditional logistic regression analysis, while no significant associations were found for the other biomarkers. Subanalysis indicated that the association between suPAR and increased risk of non-AIDS events was equally strong in participants above and below median CD4+ T-cell counts (Supplementary Table 2). The association between suPAR (ORs per 1 IQR, 1.8–2.0 for year 1 and 1.7–2.3 for pre-event), BDG (ORs per 1 IQR, 1.4–1.6 for year 1 and 1.2–1.4 for pre-event), and LBP (ORs per 1 IQR, 1.3–1.4 for year 1 and 1.6–1.8 for pre-event), and non-AIDS events remained largely unchanged after adjustment for potential confounders (results for suPAR in Supplementary Tables 1–3).

Figure 4.

Biomarker levels obtained at the visit approximately 1 year after antiretroviral therapy initiation (year 1) and odds ratios of having a non–AIDS-defining event. Unadjusted analyses adjusted for the matching factors only. Adjusted analyses controlled also for concurrent CD4+ T-cell count (adjustment includes quadratic and cubic terms) or smoking. Abbreviations: BDG, beta-D-glucan; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; I-FABP, intestinal fatty acid binding protein; IQR, interquartile range; LBP, lipopolysaccharide binding protein; MI, myocardial infarction; OR, odds ratio; oxLDL, oxidized low-density lipoproteins; sCD163, soluble CD163; suPAR, soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor. *.01 ≤ P value < .05, **P value < .01.

Figure 5.

Biomarker obtained at the visit immediately preceding the non–AIDS-defining event (pre-event) and odds ratios of having a non–AIDS-defining event. Adjusted analyses controlled also for concurrent CD4+ T-cell count (adjustment includes quadratic and cubic terms) or smoking. Abbreviations: BDG, beta-D-glucan; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; I-FABP, intestinal fatty acid binding protein; IQR, interquartile range; LBP, lipopolysaccharide binding protein; MI, myocardial infarction; OR, odds ratio; oxLDL, oxidized low-density lipoproteins; sCD163, soluble CD163; suPAR, soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor. *P = .01 to <.05; **P < .01.

The associations between year 1 and pre-event suPAR levels and non-AIDS events remained significant after adjusting for other biomarkers determined in this study and earlier (ORs per 1 IQR, 1.7 – 2.1 for year 1 and 1.7–2.1 pre-event; Table 2). Pre-event, the association between BDG and risk of non-AIDS events was attenuated when adjusting for IL-6 and sCD14; a similar effect was observed for LBP when adjusted for pre-event and year 1 IL-6 and D-dimer at year 1 (data not shown).

When examining component-specific analyses by type of non-AIDS events, higher year 1 suPAR levels were associated with increased risk of death (n = 14 events; OR per 1 IQR, 5.0; 95% CI, 1.5–16.5; P = .008), malignancy (n = 38; OR per 1 IQR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.1–3.4; P = .015), and MI/stroke (n = 30; OR per 1 IQR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.2–3.7; P = .011). The same was found for higher pre-event suPAR levels, with OR per 1 IQR of: 7.1; 95% CI, 1.4–34.9; P = .017 for death (n = 11 events); 4.4; 95% CI, 1.9–9.9; P < .001 for malignancy (n = 36 events); and 2.1; 95% CI, 1.2–3.7; P = .013 for MI/stroke (n = 28 events). Other biomarkers did not consistently predict each event. BDG was not associated with events in the component-specific analysis; at year 1, LBP remained associated with only death but was associated with all event types at the pre-event time point (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

In this case-control study, we measured plasma biomarkers of chronic inflammation, microbial translocation, and monocyte activation in cases with non-AIDS events and matched event-free controls. Three major findings are evident. First, elevated levels of suPAR before initiation of ART and during suppressive ART were strongly and consistently predictive of non-AIDS events. The association remained significant after adjusting for multiple traditional risk factors and other biomarkers. In particular, suPAR remained strongly predictive of mortality and also predictive of malignancy and MI/stroke across all time points. Second, elevated BDG and LBP were also predictive of non-AIDS events, but only at year 1 and pre-event, although at a lower extent than suPAR. Third, oxLDL was moderately predictive of malignancies at the year 1 and pre-event time points, while I-FABP and sCD163 were not associated with non-AIDS events in this study.

suPAR appears to be a particularly predictive and independent biomarker for non-AIDS events, even after adjusting for multiple traditional risk factors, other comorbid conditions, age, treatment regimen, treatment-mediated changes in CD4+ T-cell counts, and all other biomarkers evaluated in this cohort, including previously established markers (IL-6, sTNFR-I, sTNFR-II, sCD14, and D-dimer [13]). Collectively, these data suggest that pathways that involve suPAR predict non–AIDS-defining events even when virus replication is controlled independently of the classic markers of immunodeficiency.

suPAR showed particularly high predictive potential for non-AIDS mortality and malignancies. Previous studies have shown that HIV infection enhances cell surface expression of uPAR on monocytes and T lymphocytes [34–37]. uPAR and its soluble form suPAR are involved in numerous physiological and pathological pathways, which include the plasminogen activating pathway, regulation of pericellular proteolysis, modulation of cell adhesion, and migration and proliferation through interactions with proteins in the extracellular matrix [25]. Elevated levels of suPAR may reflect immune activation, are increased in several infectious diseases, and predict disease progression and mortality in untreated HIV infection [20, 37, 38]. One mechanism through which higher levels of suPAR modulate inflammation and tissue injury is inhibition of integrin–phosphatidylserine binding, an interaction that mediates uptake of apoptotic cells by phagocytes. Blocking this interaction impairs phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils and other dying cells [39].

Our data are in line with those from a previous study that showed that elevated baseline suPAR levels were associated with MI [20] and non-AIDS comorbidity at baseline and all-cause mortality at 7-year follow-up in HIV-infected patients on ART [26]. Those previous cohort studies did not adjust for many important confounders such as smoking. In our matched case-control study, we adjusted for multiple factors and found the ORs for suPAR were slightly attenuated after adjusting for smoking (unadjusted OR pre-event 2.1, dropped to 1.7 when adjusting for smoking). Nevertheless, our analysis demonstrated that suPAR remained a strong predictor of non-AIDS morbidity and mortality when measured before ART or during viral suppression and also after adjusting for multiple other factors.

Higher levels of BDG and LBP, 2 biomarkers of microbial translocation, were also associated with increased risk of non-AIDS events in unadjusted and in most adjusted analyses. Importantly, significant associations were only observed for the time point closest to the events during ART-mediated suppression. Associations between non-AIDS events and levels of BDG and LBP were overall less strong than those found for suPAR and were less robust following adjustments for potential confounders (eg, adjustment for smoking attenuated the association between BDG and non-AIDS events at the pre-event time point). These findings suggest that BDG and LBP may be less proximate or may be less proximate reflections than suPAR to the pathogenesis of each clinical outcome. Nevertheless, both biomarkers may be more reliable predictors of non-AIDS events than I-FABP, a marker of gut damage or repair that was not associated with non-AIDS events. While overall associations with non-AIDS events were not found for oxLDL, lower levels at year 1 and pre-event were associated with higher likelihood for developing non-AIDS malignancies, but this requires further investigation.

Limitations to this study include the case-control design, with 45% of cases with non-AIDS events despite viral suppression vs a reported incidence of 12.4 non-AIDS events per 1000 person-years in the United States [2, 40]. It was therefore impossible to generate direct estimates of positive and negative predictive values of biomarker cutoffs for non-AIDS event. While cases and controls were matched on covariates, there were some slight differences between cases and controls regarding frequencies of black race, chronic viral hepatitis, hypertension, and smoking status. Also, detailed data on exercise and diet status, as well as duration of smoking and alcohol use, were not collected. Due to the stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria of the parent clinical trials, participants with the highest risk for non–AIDS-related complications may also be underrepresented in our study population [13]. Results were also not adjusted for multiple comparisons, meaning that particularly nonconsistent results in subgroups (eg, lower oxLDL levels being associated with malignancies) should be interpreted with caution. In addition, the number of cases and controls with available samples varied among time points, as this was a follow-up case-control study using stored specimens. Finally, the population studied likely had lower CD4 counts when compared to newly diagnosed cases today with immediate modern ART. However, our subanalysis showed that predictive performance of suPAR was not diminished in those with higher CD4+ T-cell counts.

In conclusion, suPAR and, to a lesser extent, BDG and LBP were predictive of non-AIDS events and should be used in larger prospective studies aimed at predicting specific long-term morbidity and mortality in ART-treated HIV infection. I-FABP, sCD163, and oxLDL showed no associations with non-AIDS events overall. Once validated, suPAR may be used for future interventional studies aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality in ART-treated HIV infection. Interventions that target the suPAR pathway should be investigated to explore its role in the pathogenesis of non–AIDS-related outcomes in HIV infection.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Disclaimer. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Financial support. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (awards AI068634, AI068636, and AI106701). This work was further supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs and grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI036214, MH062512, AI134295, HD094646, AI036219, AI100665, MH113477, AI118422, AI007384, AI106039, and AI027763).

Potential conflicts of interest. M. H. and M. M. L. report grants from Gilead outside the submitted work. J. E. O. is named inventor on patents on suPAR, owned by Copenhagen University Hospital Hvidovre, Denmark, and licensed to ViroGates, Denmark; and he is cofounder, Chief Scientific Officer, and shareholder in ViroGates, Denmark. M. F. and Y. L. Z. are employees of Associates of Cape Cod, Inc., the manufacturers of Fungitell, the (1,3)-beta-glucan in vitro diagnostic kit used in this study. J. R. is cofounder and shareholder of TRISAQ, a biotechnology company that develops therapies against suPAR. N. F. serves as a consultant for Gilead. C. B. M. worked as a statistical consultant for the Northwestern University Infectious Diseases Department. All other authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Palella FJ Jr , Baker RK , Moorman AC , et al. ; HIV Outpatient Study Investigators Mortality in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: changing causes of death and disease in the HIV outpatient study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006; 43:27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wester CW , Koethe JR , Shepherd BE , et al. Non-AIDS-defining events among HIV-1-infected adults receiving combination antiretroviral therapy in resource-replete versus resource-limited urban setting. AIDS 2011; 25:1471–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Krishnan S , Schouten JT , Jacobson DL , et al. ; ACTG-ALLRT Protocol Team Incidence of non-AIDS-defining cancer in antiretroviral treatment-naïve subjects after antiretroviral treatment initiation: an ACTG longitudinal linked randomized trials analysis. Oncology 2011; 80:42–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Angelidou K , Hunt PW , Landay AL , et al. Changes in inflammation but not in T cell activation precede non-AIDS-defining events in a case-control study of patients on long-term antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2017. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hunt PW. HIV and inflammation: mechanisms and consequences. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2012; 9:139–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baker JV , Neuhaus J , Duprez D , et al. ; INSIGHT SMART Study Group Changes in inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers: a randomized comparison of immediate versus deferred antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011; 56:36–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kuller LH , Tracy R , Belloso W , et al. ; INSIGHT SMART Study Group Inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers and mortality in patients with HIV infection. PLoS Med 2008; 5:e203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Musselwhite LW , Sheikh V , Norton TD , et al. Markers of endothelial dysfunction, coagulation and tissue fibrosis independently predict venous thromboembolism in HIV. AIDS 2011; 25:787–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hanna DB , Lin J , Post WS , et al. Association of macrophage inflammation biomarkers with progression of subclinical carotid artery atherosclerosis in HIV-infected women and men. J Infect Dis 2017; 215:1352–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fitch KV , Srinivasa S , Abbara S , et al. Noncalcified coronary atherosclerotic plaque and immune activation in HIV-infected women. J Infect Dis 2013; 208:1737–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Borges ÁH , Silverberg MJ , Wentworth D , et al. ; INSIGHT SMART; ESPRIT; SILCAAT Study Groups Predicting risk of cancer during HIV infection: the role of inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers. AIDS 2013; 27:1433–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Erlandson KM , Allshouse AA , Jankowski CM , et al. Association of functional impairment with inflammation and immune activation in HIV type 1-infected adults receiving effective antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2013; 208:249–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tenorio AR , Zheng Y , Bosch RJ , et al. Soluble markers of inflammation and coagulation but not T-cell activation predict non-AIDS-defining morbid events during suppressive antiretroviral treatment. J Infect Dis 2014; 210:1248–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hoenigl M , Pérez-Santiago J , Nakazawa M , et al. (1→3)-β-d-glucan: a biomarker for microbial translocation in individuals with acute or early HIV infection? Front Immunol 2016; 7:404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marchetti G , Tincati C , Silvestri G. Microbial translocation in the pathogenesis of HIV infection and AIDS. Clin Microbiol Rev 2013; 26:2–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mehraj V , Ramendra R , Costiniuk C , et al. Circulating (1→3)-beta-D-glucan as a marker of microbial translocation in HIV infection. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), Boston, MA; 2018; Poster 254. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hunt PW , Sinclair E , Rodriguez B , et al. Gut epithelial barrier dysfunction and innate immune activation predict mortality in treated HIV infection. J Infect Dis 2014; 210:1228–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Farhour Z , Mehraj V , Chen J , Ramendra R , Lu H , Routy JP. Use of (1→3)-β-d-glucan for diagnosis and management of invasive mycoses in HIV-infected patients. Mycoses 2018; 61:718–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morris A , Hillenbrand M , Finkelman M , et al. Serum (1→3)-β-D-glucan levels in HIV-infected individuals are associated with immunosuppression, inflammation, and cardiopulmonary function. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 61:462–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rasmussen LJ , Knudsen A , Katzenstein TL , et al. Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) is a novel, independent predictive marker of myocardial infarction in HIV-1-infected patients: a nested case-control study. HIV Med 2016; 17:350–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hodges GW , Bang CN , Wachtell K , Eugen-Olsen J , Jeppesen JL. suPAR: a new biomarker for cardiovascular disease? Can J Cardiol 2015; 31:1293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hayek SS , Sever S , Ko YA , et al. Soluble urokinase receptor and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1916–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Raggam RB , Wagner J , Prüller F , et al. Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor predicts mortality in patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome. J Intern Med 2014; 276:651–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hoenigl M , Raggam RB , Wagner J , et al. Diagnostic accuracy of soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) for prediction of bacteremia in patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Clin Biochem 2013; 46:225–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thunø M , Macho B , Eugen-Olsen J. suPAR: the molecular crystal ball. Dis Markers 2009; 27:157–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kirkegaard-Klitbo DM , Langkilde A , Mejer N , Andersen O , Eugen-Olsen J , Benfield T. Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor is a predictor of incident non-AIDS comorbidity and all-cause mortality in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Infect Dis 2017; 216:819–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Burdo TH , Weiffenbach A , Woods SP , Letendre S , Ellis RJ , Williams KC. Elevated sCD163 in plasma but not cerebrospinal fluid is a marker of neurocognitive impairment in HIV infection. AIDS 2013; 27:1387–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hileman CO , Turner R , Funderburg NT , Semba RD , McComsey GA. Changes in oxidized lipids drive the improvement in monocyte activation and vascular disease after statin therapy in HIV. AIDS 2016; 30:65–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zidar DA , Juchnowski S , Ferrari B , et al. Oxidized LDL levels are increased in HIV infection and may drive monocyte activation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 69:154–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Eugen-Olsen J , Ladelund S , Sørensen LT. Plasma suPAR is lowered by smoking cessation: a randomized controlled study. Eur J Clin Invest 2016; 46:305–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ribaudo HJ , Benson CA , Zheng Y , et al. ; ACTG A5001/ALLRT Protocol Team No risk of myocardial infarction associated with initial antiretroviral treatment containing abacavir: short and long-term results from ACTG A5001/ALLRT. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:929–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gandhi RT , Spritzler J , Chan E , et al. ; ACTG 384 Team Effect of baseline- and treatment-related factors on immunologic recovery after initiation of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1-positive subjects: results from ACTG 384. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006; 42:426–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hoenigl M , Chaillon A , Little SJ. CD4/CD8 cell ratio in acute HIV infection and the impact of early antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63:425–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Andersen O , Eugen-Olsen J , Kofoed K , Iversen J , Haugaard SB. Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor is a marker of dysmetabolism in HIV-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Med Virol 2008; 80:209–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sidenius N , Nebuloni M , Sala S , et al. Expression of the urokinase plasminogen activator and its receptor in HIV-1-associated central nervous system disease. J Neuroimmunol 2004; 157:133–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schneider UV , Nielsen RL , Pedersen C , Eugen-Olsen J. The prognostic value of the suPARnostic ELISA in HIV-1 infected individuals is not affected by uPAR promoter polymorphisms. BMC Infect Dis 2007; 7:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lawn SD , Myer L , Bangani N , Vogt M , Wood R. Plasma levels of soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) and early mortality risk among patients enrolling for antiretroviral treatment in South Africa. BMC Infect Dis 2007; 7:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Oliveira I , Andersen A , Furtado A , et al. Assessment of simple risk markers for early mortality among HIV-infected patients in Guinea-Bissau: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2012; 2. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen,2012-001587. Print 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Park YJ , Liu G , Tsuruta Y , Lorne E , Abraham E. Participation of the urokinase receptor in neutrophil efferocytosis. Blood 2009; 114:860–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hoenigl M , Graff-Zivin J , Little SJ. Costs per diagnosis of acute HIV infection in community-based screening strategies: a comparative analysis of four screening algorithms. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:501–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.