Abstract

Recently, studies have focused on the antihyperalgesic activity of the A3 adenosine receptor (A3AR) in several chronic pain models, but the cellular and molecular basis of this effect is still unknown. Here, we investigated the expression and functional effects of A3AR on the excitability of small- to medium-sized, capsaicin-sensitive, dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons isolated from 3- to 4-week-old rats. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction experiments and immunofluorescence analysis revealed A3AR expression in DRG neurons. Patch-clamp experiments demonstrated that 2 distinct A3AR agonists, Cl-IB-MECA and the highly selective MRS5980, inhibited Ca2+-activated K+ (KCa) currents evoked by a voltage-ramp protocol. This effect was dependent on a reduction in Ca2+ influx via N-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, as Cl-IB-MECA–induced inhibition was sensitive to the N-type blocker PD173212 but not to the L-type blocker, lacidipine. The endogenous agonist adenosine also reduced N-type Ca2+ currents, and its effect was inhibited by 56% in the presence of A3AR antagonist MRS1523, demonstrating that the majority of adenosine’s effect is mediated by this receptor subtype. Current-clamp recordings demonstrated that neuronal firing of rat DRG neurons was also significantly reduced by A3AR activation in a MRS1523-sensitive but PD173212-insensitive manner. Intracellular Ca2+ measurements confirmed the inhibitory role of A3AR on DRG neuronal firing. We conclude that pain-relieving effects observed on A3AR activation could be mediated through N-type Ca2+ channel block and action potential inhibition as independent mechanisms in isolated rat DRG neurons. These findings support A3AR-based therapy as a viable approach to alleviate pain in different pathologies.

Keywords: Dorsal root ganglion neurons, Pronociceptive Ca2+ currents, Adenosine A3 receptors, Action potential

1. Introduction

Pain control is a vast, unmet medical need with a high societal cost impact.18 Current treatments (opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antidepressants, or anticonvulsants) are frequently inadequate or associated with adverse side effects.7,18,43 Therefore, new therapeutics for managing patient pain are being developed.

Voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (VDCCs) are crucial mediators of neuropathic pain, as confirmed by the fact that α2δ ligands, ie, gabapentinoids, are a first-line treatment for this type of pain.13,55 Activation of VDCCs at a presynaptic level induces neurotransmitter release through the peripheral and central nervous system, including sensory neurons in dorsal root ganglia (DRG), which are considered the primary site of nociception. It is noteworthy that the selective N-type VDCC blocker ω-conotoxin GVIA (ω-CTX) inhibits dorsal root stimulus–evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents in lamina I dorsal horn neurons by 60%,23 suggesting that these channels exert a primary role in mediating neurotransmitter release during nociception. Furthermore, aberrant expression and/or activity of N-type VDCCs is associated with neuropathic pain,20 and ziconotide, a derivative of ω-CTX, was FDA approved in 2000 (Prialt) for intrathecal treatment of severe and refractory chronic pain.2,28,38 However, severe adverse effects are associated with a direct Ca2+ channel block; thus, a modulation of Ca2+ influx would be preferable.

Adenosine is an endogenous neuromodulator acting on 4 metabotropic receptors: the Gi-coupled A1 and A3 adenosine receptors (ARs) and the Gs-coupled A2A and A2B subtypes.15 A1AR activation inhibits pain behaviours in different models of acute or chronic pain.10 Unfortunately, the therapeutic utility of A1AR agonists is limited by their adverse cardiovascular effects. Of note, exciting preclinical observations designate the A3AR as a powerful antihyperalgesic mediator in different in vivo rodent models of experimental neuropathic pain,14,29,30,33,34,37,51,56 suggesting the use of A3AR agonists for chronic pain treatment without cardiovascular implications.

A3ARs are expressed in DRG neurons, with species-specific differences being described.44,53 However, cellular mechanisms mediating pain relief on A3AR activation remain largely unexplored. A3AR-selective ligands currently available allow for the dissection of A3AR-based molecular effects on DRG neuronal excitability.30 The recently synthetized and highly selective A3AR agonist MRS5698, and the more water-soluble congener MRS5980, proved effective in preventing allodynia and hyperalgesia associated with traumatic nerve injury, chemotherapy, and bone cancer in rodents.14,29,34 These second-generation, highly selective A3AR agonists are at least several orders of magnitude more selective than the early generation exemplified by IB-MECA and Cl-IB-MECA.29,34,51

Several early electrophysiological studies reported that adenosine and its analogues inhibit Ca2+-dependent plateau potentials and VDCC activation in isolated rat DRG neurons.11,19,36 However, AR subtypes were initially poorly characterized, with only A1AR and a “generic” A2 subtype being described based on their ability to modulate intracellular cAMP accumulation. Nevertheless, MacDonald and coworkers36 argued that neither AlAR nor A2AR seems to be responsible for Ca2+ current inhibition in rat DRG neurons, leading to the possibility that a hypothetically different AR could be involved. Building on this observation, the aim of this study was to fill a major gap by investigating whether the A3AR modulates membrane currents and excitability in isolated rat DRG neurons.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Cell cultures

Animal experiments were performed according to Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the European Union Council (September 22, 2010) and to the Italian Law on Animal Welfare (DL 26/2014). The protocol was approved by the University of Florence Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and by the Italian Ministry of Health. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to use a minimal number of animals needed to produce reliable scientific data. Sprague-Dawley rats (3–4 weeks old, Envigo, Udine, Italy) of both sexes were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled vivarium (12-hour dark/light cycle, free access to food and water) and sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Primary DRG neurons were isolated and cultured as described.16,40 Briefly, ganglia were bilaterally excised and enzymatically digested using 2 mg/mL of collagenase type 1A and 1 mg/mL of trypsin (both compounds from Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy) in Hank’s balanced salt solution (25–35 minutes at 37°C). Cells were then pelleted and resuspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated horse serum, 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin, and 2-mM l-glutamine for mechanical digestion. After centrifugation (1200g, 5 minutes), neurons were suspended in the above medium, enriched with 100 ng/mL of mouse nerve growth factor and 2.5 mM of cytosine-β-d-arabino-furanoside free base, and then plated on 13-mm or 25-mm glass coverslips coated by poly-l-lysine (8.3 mM) and laminin (5 mM). Dorsal root ganglion neurons were cultured for 1 to 2 days before being used for experiments. In a set of experiments, DRG cultures were maintained in the absence of nerve growth factor. However, no difference was found in any of the effects tested in the present research, and data were pooled.

2.1.1. Electrophysiology

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed as previously described.4,5 The following solutions were used: standard, K+-containing, extracellular solution (mM): NaCl 147; KCl 4; MgCl2 1; CaCl2 2; HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) 10; and D-glucose 10 (pH 7.4 with NaOH). Standard K+-based pipette solution (mM): K-gluconate 130; NaCl 4.8; KCl 10; MgCl2 2; CaCl2 1; Na2-ATP 2; Na2-GTP 0.3; EGTA 3; and HEPES 10 (pH 7.4 with KOH). The calculated liquid junction potential for K+-gluconate pipettes was 15.0 mV. All voltage values reported here have been adjusted accordingly. For K+-replacement experiments, extracellular K+ was substituted by equimolar Cs+ and the following, Cs+-based, pipette solution used was (mM): CsCl 120; Mg2-ATP 3; EGTA 10; and HEPES 10 (pH 7.4 with CsOH). Ca2+ currents were isolated by using Cs+-based pipette solution and by adding 1-μM tetrodotoxin (TTX), 200-nM A887826 to a 5-mM Ca2+-containing and Cs+-substituted extracellular solution to block TTX-sensitive and TTX-insensitive Na+ channels, respectively. As reported in Results, ramp experiments revealed that Cl-IB-MECA–inhibited Ca2+ currents in DRG neurons were completely prevented in the presence of extracellular Cd2+. The effect of Cd2+ was not different when applied at 100 μM, 500 μM, or 1 mM concentrations (see Supplementary Fig. 2, available at http://links.lww.com/PAIN/A733). So, when studying the effect of this compound on Ca2+ currents evoked in isolation, 100-μM Ni2+ was added to the extracellular solution to exclude T-type Ca2+ channels, which do not seem to be involved in A3AR-mediated effect. For this reason, the hypothetical, additional, involvement of T-type Ca2+ channels in A AR-mediated Ca2+ channel modulation was not investigated in the present research and will be addressed in a separate work. Na+ currents were isolated by using Cs+-based pipette solution and by adding 100-μM Cd2+ and 100-μM Ni2+ to a 5-mM Ca2+-containing and Cs+-substituted extracellular solution.

Cells were transferred to a 1-mL recording chamber mounted on the platform of an inverted microscope (Olympus CKX41, Milan, Italy) and superfused at a flow rate of 2 mL/minute by a 3-way perfusion valve controller (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). Borosilicate glass electrodes (Harvard Apparatus) were pulled with a Sutter Instruments puller (model P-87) to a final tip resistance of 1.5 to 3 MΩ. Data were acquired with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA), low-pass filtered at 10 kHz, stored, and analysed with pClamp 9.2 software (Axon Instruments). All the experiments were performed at room temperature (RT: 20–22°C). Series resistance (Rs), membrane resistance (Rm), and membrane capacitance (Cm) were routinely measured by fast hyperpolarizing voltage pulses (from −60 to −70 mV, 40-ms duration). Only cells showing a stable Cm and Rs before, during, and after drug application were included in the analysis. Immediately after seal breaking-through, cell’s resting membrane potential was determined by switching the amplifier to the current-clamp mode. A voltage-ramp protocol (800-ms depolarization from +65 to −135 mV; holding potential, or Vh, of −75 mV) was used to evoke a wide range of overall voltage-dependent currents before, during, and after drug treatments. TRPA1- or TRPV1-mediated currents were detected as inward currents activated in −60 mV (corresponding to −75 mV after liquid junction potential correction) clamped cells on superfusion of the respective agonists allyl isothiocyanate (AITC) and capsaicin, respectively, as already shown elsewhere.16,40 Voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels’ currents were evoked in Cs+-replacement conditions by a 0-mV step depolarization (200 ms, Vh = −65 mV) once every 30 seconds, a time that allowed complete recovery from eventual Ca2+ channel in-activation and minimized Ca2+ current run down. The current-to-voltage relationship of Ca2+ currents was obtained by eliciting 10 depolarizing voltage steps (200-ms duration, 10-mV increments, 5-second interval) from −50 to +50 mV starting from a Vh of −65 mV. Na+ currents were evoked in Cs+-replacement conditions by a 0-mV step depolarization (40 ms, Vh = −90 mV) once every 5 seconds.

Averaged currents were normalized to cell capacitance and expressed as pA/pF. Cell capacitance was used to estimate neuronal diameter by assuming an approximated spherical cell shape according to the calculated Cm for all biological membranes of 1 μF/cm2 and to the equation of the sphere surface: A = 4 πr2.28

Current-clamp recordings were performed as described.5 A ramp current protocol consisting in 1-second injection of 30-pA positive current from the resting membrane potential (only cells showing a Vm of at least −50 mV were chosen) was used to evoke action potential (AP) firing in a typical DRG neuron once every 30 seconds. After at least 3-minute recording of a stable baseline, Cl-IB-MECA (100 nM) was applied for 8 to 10 minutes. Action potential firing was quantified by counting the number of APs evoked by a ramp current (1 second). When the Cl-IB-MECA was applied in the presence of MRS1523 (100 nM) or PD173212 (1 μM), the A3AR antagonist or the N-type VDCC blocker was added at least 10 minutes before the agonist. Current-clamp recordings were filtered at 10 kHz and digitized at 1 kHz. All current-clamp values reported in Table 1 are the average of at least 3 episodes and have been corrected for liquid junction potential. All AP parameters refer to the first AP generated by the ramp. Resting Vm was calculated as the averaged membrane voltage measured 200 ms before ramp current injection. The rate of AP depolarization and hyperpolarization was measured as the first derivative of membrane potential over time (mV/ms). Action potential threshold was defined as the point at which the derivative first exceeded 30 mV/ms. Action potential amplitude was calculated as the difference between the peak reached by the overshoot and the threshold. Action potential time to peak was measured as the time between the threshold and the voltage peak reached by the AP. Action potential half-width was measured as the time to reach half the AP amplitude (ms). The current needed to produce the first spike was defined as “current threshold” and was measured as the minimal amount of current (pA) injected during the ramp protocol leading to the first AP initiation. The AP duration measured the difference between the time of reaching the threshold potential during the rising phase and the time when the repolarizing potential crossed the threshold value again. The fast afterhyperpolarization was measured as the difference between the voltage threshold and the minimum potential reached after the AP peak.

Table 1.

Action potential parameters measured in DRG neurons under the current-clamp mode.

| Ctrl (n = 6) | Cl-IB-MECA (n = 6) | Ctrl (n = 7) | PD173212 (n = 7) | PD173212 (n = 8) | PD173212 + Cl-IB-MECA (n = 8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting Vm (mV) | −61.2 ± 2.3 | −60.1 ± 2.1 | −63.6 ± 2.9 | −59.7 ± 3.6* | −53.3 ± 4.0 | −54.1 ± 2.6 |

| AP time to peak (ms) | 685.1 ± 100.7 | 684.6 ± 105.2 | 530.7 ± 61.9 | 504.2 ± 70.5 | 465.0 ± 73.54 | 480.1 ± 84.65 |

| AP half width (ms) | 1.7 ± ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 2.3 | 3.8 ± 2.0 | 2.6 ± 0.6 |

| AP amplitude (mV) | 65.0 ± 6.3 | 57.7 ± 7.9 | 60.6 ± 7.6 | 58.0 ± 12.4 | 57.6 ± 6.2 | 52.5 ± 5.5 |

| Current threshold (pA) | 16.0 ± 5.3 | 20.7 ± 7.4 | 4.0 ± 1.6 | 4.3 ± 2.0 | 3.3 ± 1.1 | 3.8 ± 1.1 |

| AP threshold (mV) | −15.7 ± 1.8 | −14.5 ± 1.4 | −12.7 ± 1.9 | −14.1 ± 1.5† | −14.1 ± 2.6 | −13.8 ± 2.4 |

| Current threshold (pA) | 16.0 ± 5.3 | 20.7 ± 7.4 | 4.0 ± 1.6 | 4.3 ± 2.0 | 3.3 ± 1.1 | 3.8 ± 1.1 |

| AP threshold (mV) | −15.7 ± 1.8 | −14.5 ± 1.4 | −12.7 ± 1.9 | −14.1 ± 1.5† | −14.1 ± 2.6 | −13.8 ± 2.4 |

| AP duration (ms) | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.6‡ | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.8 |

| fAHP (mV) | 41.9 ± 2.9 | 39.5 ± 4.1 | 46.0 ± 2.1 | 34.8 ± 4.4§ | 37.4 ± 3.1 | 34.3 ± 4.0 |

The following experimental groups were analyzed: Control: Ctrl vs Cl-IB-MECA (100 nM; n = 6); Ctrl vs PD173212 (1 μM; n = 7); and PD173212 vs PD173212 + Cl-IB-MECA (n = 8). All AP parameters are referred to the first action potential (AP) generated by the ramp. Resting Vm was calculated as the averaged membrane voltage measured 200 ms before ramp current injection. Action potential time to peak was measured as the time between the threshold and the voltage peak reached by the AP. Action potential half-width was measured as the time to reach half the AP amplitude. Action potential amplitude was calculated as the difference between the peak reached by the overshoot and the threshold. The current needed to produce the first spike was defined as “current threshold” and was measured as the minimal amount of current (pA) injected during the ramp protocol leading to the first AP initiation. Action potential threshold was defined as the point at which the derivative first exceeded 30 mV/ms. Action potential duration measured the difference between the time of reaching the threshold potential during the rising phase and the time when the repolarizing potential crossed the threshold value again. The fast afterhyperpolarization (fAHP) was measured as the difference between the voltage threshold and the minimum potential reached after the AP peak.

The paired Student t test, n = 7.

P = 0.0165.

P = 0.0491.

P = 0.0089.

P = 0.0168 vs respective ctrl.

AP, action potential; DRG, dorsal root ganglion.

2.2. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis

Total RNA was isolated using Nucleospin RNA (Macherey–Nagel Duren, Duren, Germany) with DNAse treatment according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The expression of A3ARs was evaluated by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using gene-specific fluorescently labeled TaqMan MGB probe (minor groove binder). For the RT-PCR of A3ARs, a predeveloped assay was used: Adora3 Rn_00563680_m1. The amount of target mRNA was normalized to the endogenous reference, GADPH Rn 01749022_g1, and to a homogenate of the rat brain taken as a positive, according to the 2−ΔΔCt method. Data are the result of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate.

2.3. Immunocytochemical analysis

Primary DRG cultures grown on 13-mm diameter coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline for 20 minutes at RT. Rabbit polyclonal A3AR-selective primary antibody (Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel; https://www.alomone.com) was diluted 1:200 in bovine serum dilution buffer (450-mM NaCl, 20-mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 15% fetal bovine serum, and 0.3% Triton X-100) and incubated for 2.5 hours at RT. Cells were then washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline and incubated for 1 hour at RT with a donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody (diluted 1:500 in bovine serum dilution buffer) conjugated to AlexaFluor 488 (Life Technologies, Invitrogen, Milan, Italy). Coverslips were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to visualize cells nuclei, digitized, and acquired by using an Olympus BX40 microscope equipped with CellSens Dimension Software (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany). Control experiments were performed by incubating fixed cells with the secondary antibody alone to exclude nonspecific binding.

2.4. Intracellular Ca2+ measurement

Intracellular cytosolic Ca2+ dynamic ([Ca2+]i) was evaluated in fura-2–loaded DRG neurons as described.8 Briefly, 104 cells were plated on round glass coverslips (25-mm diameter) and seeded for 1 to 2 days in a complete medium. Cells were loaded with 4-μM fura-2AM (Molecular Probes-Invitrogen Life technologies, San Giuliano Milanese, Italy) for 45 minutes at 37°C and then washed with the K+-containing standard extracellular solution described above. Coverslips were mounted in a perfusion chamber and placed on the stage of an inverted reflected light fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axio Vert. A1 FL-LED) equipped with fluorescence excitation (385 nm) based on LED. Before electrical field stimulation, cells were incubated for at least 5 minutes with different solutions containing the following molecules: control (standard extracellular solution), 1-μM TTX + 200-nM A887826, 30-nM Cl-IB-MECA, and 1-μM verapamil + 0.5-μM PD173212. Fura-2 fluorescence was recorded with a Tucsen Dhyana 400D CMOS camera (Tucsen Photonics, Co, Ltd, Fuzhou, China) with a frame rate of 40 Hz and a resolution of 1024 × 1020 pixels2. Ca2+ dynamic was measured by single-cell imaging analysis at 35°C.8 Images were recorded using Dhyana software SamplePro and dynamically analyzed with the open-source community software for bio-imaging Icy (Institute Pasteur, Paris, France). Ca2+ transients were induced by electrical field stimulation at 0.1-Hz frequency, 100-mV voltage, and 50-ms width duration. Preliminary experiments were performed to optimize stimulation parameters in control condition (standard extracellular solution). Frequency, voltage, and duration were chosen to obtain a high number of responder cells, defined as “spiking” cells, without signs of membrane electroporation and stable fura-2 fluorescence. A signal-to-noise ratio of at least 5 arbitrary units was considered as Ca2+ transient. Spiking DRG neurons were identified as cells showing at least 5 Ca2+ transients in 1 minute. In spiking cells, the following parameters were evaluated as the mean of at least 3 different Ca2+ transients: the ratio between the fluorescence maximal variation induced by electrical field stimulation and basal fluorescence (ΔF/F, measured as arbitrary units) and the decay time of Ca2+ transient (tau, τ). Tau was calculated according to the following equation: . According to the fitting function, the tau (τ) parameter represented the time necessary for [Ca2+]i to reach 36.8% of the maximal value. Tau was therefore reported as the decay time value (s). At least 3 Ca2+ transients for each different treatment were analysed and averaged. The cell diameter of analyzed DRG neurons was measured in pixels using ImageJ software and transformed in micrometer by a specific calibration scale.

Experiments were repeated in 4 different neuronal preparations. All DRG neurons (identified by transmitted light microscopy) found in an optical field (using 40× magnification objective) were analyzed. From 16 to 22 cells were evaluated blindly every experimental day for each experimental treatment.

2.5. Drugs

2-Chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide (Cl-IB-MECA), 5-(4-butoxy-3-chlorophenyl)-N-[[2-(4-morpholinyl)-3-pyridinyl]methyl]-3-pyridinecarboxamide (A887826), 3-propyl-6-ethyl-5-[(ethylthio)carbonyl]-2 phenyl-4-propyl-3-pyridine carboxylate (MRS1523), N-(2-methoxyphenyl)-N′-[2-(3-pyridinyl)-4-quinazolinyl]-urea (VUF5574), 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX), N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CPA), adenosine, apamin, and tetraethylammonium (TEA) were purchased from Sigma (www.sigmaaldrich.com). Tetrodotoxin (TTX) and 4-t-butyl-N-methyl-N-aralkyl-peptidylamine (PD173212) were purchased from Alomone Labs. Verapamil was purchased from Calbiochem (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The new, highly selective, A3 receptor agonist (1S,2R,3S,4R,5S)-4-(2-((5-chlorothiophen-2-yl)ethynyl)-6-(methyl-amino)-9H-purin-9-yl)-2,3-dihydroxy-N-methylbicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-1-carboxamide (MRS5980) was synthesized as reported previously.12,51 See Supplementary Figure 1 for chemical structure of AR ligands used in the present research (available at http://links.lww.com/PAIN/A733). All drugs were stored at −20°C as 103 to 104 times more concentrated stock solutions, dissolved daily in the extracellular solution to the final concentration, and applied by bath superfusion. Tetrodotoxin, apamin, and TEA stock solutions were prepared in distilled water. All other compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide. Control experiments performed in the present research demonstrated that the maximal dimethyl sulphoxide concentration used in the present work (0.1%) was inactive in modulating membrane currents in our experimental conditions in DRG neurons.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Student paired or unpaired t tests, and one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni analysis were performed, as appropriated, to determine statistical significance (set at P < 0.05). In experiments of intracellular Ca2+ measurement, 3 different parameters were measured: (1) the ratio between DRG neurons defined as “spiking” (Ca2+ transient) and “not spiking” in each experimental condition; (2) ΔF/F; and (3) tau of Ca2+ transient evoked in “spiking” cells. The effect of each treatment in changing the ratio between “spiking” and “not spiking” was evaluated using the χ2 test (PRIMER); other data (reported as mean ± SEM) were statistically analysed using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni analysis. Data were analysed using “Origin 10” or “GraphPad Prism” (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) software.

3. Results

3.1. Selective A3AR activation inhibits Ca2+ currents in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons

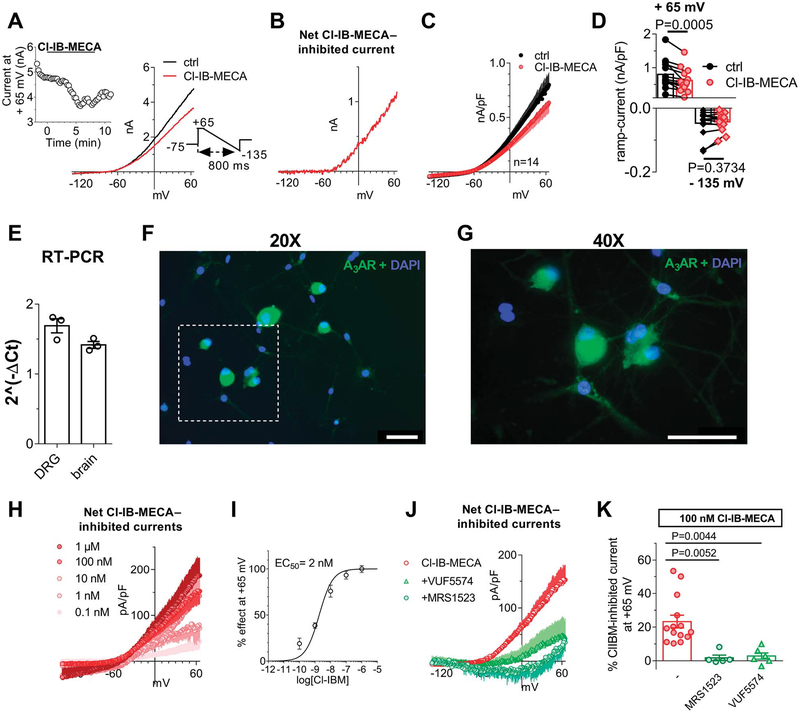

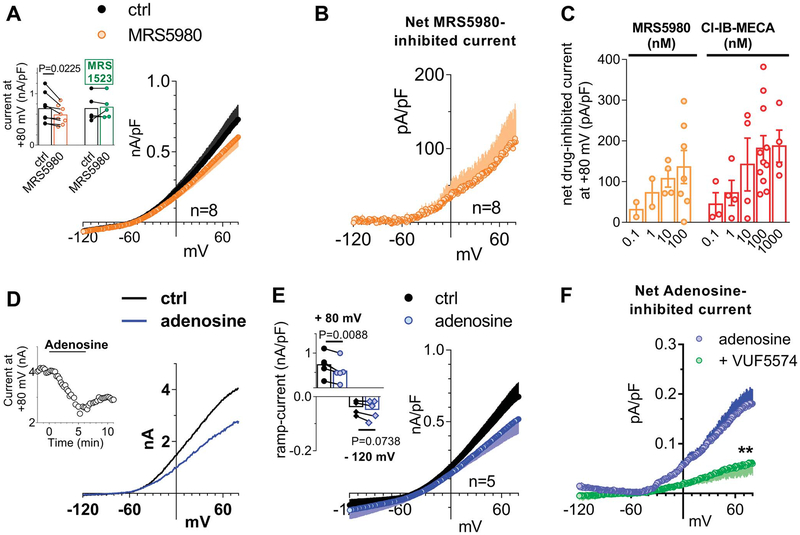

Because no data are available up to now concerning the electrophysiological effect/s of A3AR on DRG neurons, we first tested the prototypical A3AR agonist Cl-IB-MECA under “similar physiological conditions,” ie, we applied a voltage-ramp protocol (from +65 to −135 mV, 800-ms duration: see inset of Fig. 1A) in K+-containing solutions before, during, and after the superfusion of this compound. As shown in Figure 1A, the application of 100-nM Cl-IB-MECA decreased overall outward currents evoked by the voltage ramp: the effect peaked within 5 minutes and was partially reversed after drug washout. Figure 1B shows that the net Cl-IB-MECA–inhibited current was an outward current activated at potentials positive to −45 mV. Ramp current inhibition measured at +65 mV in the presence of Cl-IB-MECA was statistically significant in 14 cells investigated (Figs. 1C and D: from 799.0 ± 111.9 pA/pF in control to 617.2 ± 92.3 pA/pF in 100-nM Cl-IB-MECA, P = 0.0005, the paired Student t test), whereas no changes in inward ramp currents at −135 mV were detected (Figs. 1C and D: from −46.6 ± 10.7 pA/pF in control to −42.8 ± 7.5 pA/pF in 100-nM Cl-IB-MECA, P = 0.3734, the paired Student t test). The Cl-IB-MECA effect was observed in all cells tested, in agreement with high A3AR levels expression in DRG homogenate as revealed by RT-PCR (Fig. 1E) and immunocytochemical analysis (Figs. 1F and G). Our data are in line with previous work in the literature demonstrating the expression of this receptor subtype on rat DRG neurons, even if species-specific differences have been found.44,53 The effect was concentration dependent (Fig. 1H), with an EC50 of 2.0 nM (confidence limits: from 1.2 to 3.2 nM; Fig. 1I), and prevented by 2 different A3AR antagonists: VUF5574 (100 nM) and MRS1523 (100 nM) (Figs. 1J and K). Another highly selective A3AR agonist was tested: MRS5980, whose EC50 is described in the subnanomolar range (EC50 = 0.7 ± 0.1 nM52). This compound also concentration dependently inhibited total outward currents evoked by the ramp protocol at +65 mV in 8 cells investigated (Figs. 2A–C), and the effect was prevented by MRS1523 (inset in Fig. 2A).

Figure 1.

Selective A3AR activation inhibits ramp-evoked outward currents in cultured rat DRG neurons. (A) Left panel: original patch-clamp current traces recorded in a representative cell where a voltage-ramp protocol (+65/−135 mV, 800 ms: lower inset) was applied before (ctrl), during, and after Cl-IB-MECA (100 nM) superfusion. Upper inset: time course of ramp-evoked currents at +65 mV in the same cell. (B) Net Cl-IB-MECA–inhibited current, obtained by subtraction of the ramp recorded in Cl-IB-MECA from the control ramp, in the same cell. (C and D) Averaged ramp traces (C) and pooled data at +65 and −135 mV (D) of ramp-evoked currents measured in the absence or presence of Cl-IB-MECA in 14 cells investigated. P = 0.0005 at +65 mV; P = 0.3734 at −135 mV; the paired Student t test, n = 14. (E) Real-time polymerase chain reaction experiments demonstrated that A3AR-coding mRNA is present in rat DRG homogenates. Data were normalized to A3 receptor expression as a fraction of the house-keeping gene GADPH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) and have been obtained in 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. A brain tissue homogenate was taken as the positive control. (F and G) 20× (F) and 40× (G) magnification of A3AR immunofluorescent labelling (green) of DRG cultures. Cells nuclei were marked with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 50 μm. (H) Averaged Cl-IB-MECA–inhibited currents at different agonist concentrations (0.1–1000 nM; at least n = 4 in each experimental condition). (I) Concentration-response curve of Cl-IB-MECA effect on ramp currents measured at +65 mV (confidence limit: from 1.2 to 3.2 nM). (J and K) Net 100 nM Cl-IB-MECA–inhibited currents (J) and respective pooled data at +65 mV (K) recorded in the absence or presence of 2 different A3AR antagonists: MRS1523 (100 nM; n = 5) and VUF5574 (100 nM; n = 6). One-way ANOVA, Bonferroni posttest. ANOVA, analysis of variance; DRG, dorsal root ganglion; RT-PCR, real-time polymerase chain reaction.

Figure 2.

The newly synthetized, highly selective, A3AR agonist MRS5980 and the endogenous ligand adenosine mimic Cl-IB-MECA effect in inhibiting ramp-evoked outward currents in isolated rat DRG neurons. (A) Averaged traces of ramp-evoked currents measured before or after MRS5980 application (100 nM) in 8 cells investigated. Inset: pooled data or ramp-evoked current at +65 mV in the presence of MRS5980 alone or during coapplication with the A3AR antagonist MRS1523 (100 nM; n = 5). The paired Student t test. (B) Net MRS5980-inhibited current in 8 cells tested. (C) Comparison between net Cl-IB-MECA–or MRS5980-inhibited ramp currents measured at +65 mV at different agonists concentrations. (D) Original ramp current traces recorded in a representative cell before (ctrl), during, or after adenosine (30 μM) superfusion. Inset: time course of ramp-evoked currents at +65 mV in the same cell. (E) Pooled data of ramp-evoked currents at +65 mV or −135 mV before or after the application of adenosine in 5 cells investigated. P = 0.0088 at +65 mV; P = 0.0738 at −135 mV, the paired Student t test, n = 5. (F) Averaged adenosine-inhibited currents, obtained by subtraction of the adenosine ramp from the control ramp, recorded in the absence (n = 5) or presence of A3AR antagonist VUF5574 (100 nM, n = 6). **P = 0.0054 at + 65 mV, the unpaired Student t test. DRG, dorsal root ganglion.

The effect of both A3AR agonists was shared by the endogenous ligand adenosine (30 μM: Fig. 2D), which significantly decreased ramp currents at + 65 mV in 5 cells tested without modifying the inward component (Fig. 2E). Notably, the adenosine effect was significantly inhibited by VUF5574 (100 nM; n 5 6: Fig. 2F; **P = 0.0054, the unpaired Student t test).

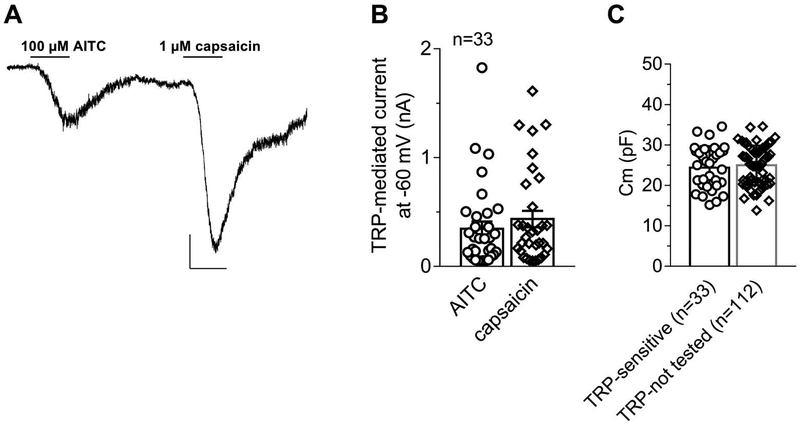

To define A3AR-responding DRG neurons as nociceptors, cells were tested for their responsiveness to the TRPA1 agonist AITC and the TRPV1 agonist capsaicin. At least 5 minutes after Cl-IB-MECA removal, cells were voltage clamped at −75 mV and the 2 TRP agonists were applied consecutively. As shown in a typical cell in Figure 3A, both compounds activated an inward current in the vast majority of cells investigated (Fig. 3B): 8 of 33 cells tested for TRP response were insensitive to 1 of the 2 TRP agonists, and 1 cell was insensitive to both compounds but still sensitive to Cl-IB-MECA. In Figure 3C, we pooled cell capacitance values measured in those 33 TRP-sensitive cells vs capacitance values measured in the residual cells analyzed in the present research but not tested for TRP responses (TRP not tested: n = 112). Of note, cell capacitance, as a measure of a spherical-approximated cell soma, was not statistically different in TRP-sensitive (25.1 ± 1.7 pF; n = 33, corresponding to a cell diameter of 28.3 μm: see Methods) vs TRP not tested (25.3 ± 1.2 pF; n = 112, corresponding to a cell diameter of 28.4 μm; the unpaired Student t test, P = 0.9825; Fig. 3C) neurons. Our results thus indicate that both groups of cells were composed of neurons with a 25-μm diameter, therefore adhering to the definition of small- to medium-sized DRG neurons defined as “nociceptors.”22,48

Figure 3.

Dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons responding to Cl-IB-MECA are nociceptors sensitive to the TRPV1 and TRPA1 agonists capsaicin and allyl isothiocyanate. (A) Original current trace recorded in a −75 mV-clamped cell after 10-minute washout of a previous Cl-IB-MECA application. Scale bars: 200 pA; 1 minute. (B) Pooled data of AITC- and capsaicin-activated currents in 33 cells investigated. (C) Pooled data of cell capacitance measured in AITC- and capsaicin-sensitive cells (“TRP-sensitive” neurons: n = 33) or in cells not exposed to capsaicin or AITC challenge (“TRP non-tested” neurons, n = 112). P = 0.8045, the unpaired Student t test. AITC, allyl isothiocyanate.

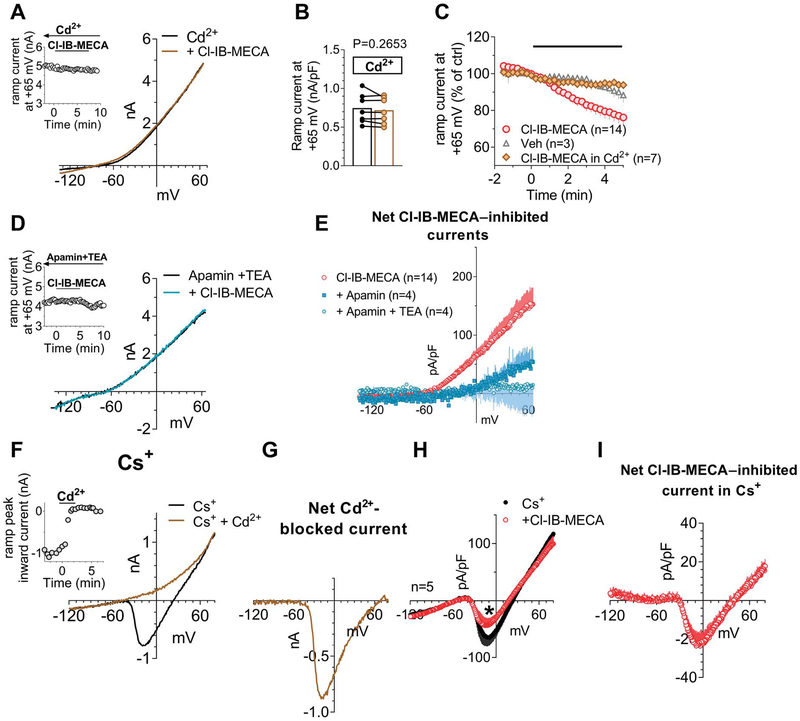

Data in the literature demonstrate that adenosine and its analogues inhibit VDCCs in rat DRG neurons11,36 with no obvious distinction between A1- vs A3-mediated effects provided to date. For this reason, we tested the hypothesis that the decreased total outward currents observed in the present work by A3AR activation might depend on a decrease of Ca2+ entry from VDCCs and, thus, reduced activation of Ca2+-activated K+ conductances (KCa). Therefore, we applied Cl-IB-MECA in the presence of the nonselective VDCC blocker Cd2+. First of all, by using our voltage-ramp protocol, we confirmed the activation of KCa channels in DRG neurons by applying extracellular Cd2+ that, per se, induced a 34.0 ± 13.3% inhibition of total outward currents evoked by the ramp protocol (from +245.7 ± 15.6 pA/pF in ctrl to 167.2 ± 26.3 pA/pF in 100-μM Cd2+ at +65 mV, n = 4, P = 0.0339; the paired Student t test; Supplementary Fig. 2C: 34.0 ± 8.7% current inhibition, available at http://links.lww.com/PAIN/A733). The effect of Cd2+ was not different when applied at 100 μM, 500 μM, or 1 mM concentrations (see Supplementary Fig. 2A–C, available at http://links.lww.com/PAIN/A733). Thus, we applied Cl-IB-MECA in the presence of Cd2+ to test whether the A3AR agonist effect was prevented in conditions of Ca2+ entry block. As shown in Figure 4A–C, Cd2+ completely prevented Cl-IB-MECA–induced decrease of outward ramp currents. Data were confirmed by applying 2 selective blockers of KCa channels: apamin (100 nM), which selectively blocks small-conductance KCa (SK channels), and TEA at low concentrations (200 μM), which selectively inhibits big-conductance KCa (BK channels). Alone or in combination, both compounds significantly or completely prevented Cl-IB-MECA–mediated inhibition of ramp-evoked outward currents (Figs. 4D and E). The above data demonstrate that BK and SK channel activation was necessary for the A3AR-mediated ramp-current inhibition in rat DRG neurons.

Figure 4.

A3AR activation in DRG neurons inhibits Ca2+-activated K+ currents by reducing Ca2+ influx from voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. (A) Original ramp current traces recorded in 1 mM Cd2+-containing extracellular solution before (ctrl) or during Cl-IB-MECA (100 nM) application in a representative cell. Inset: time course of ramp-evoked currents at +65 mV in the same cell. (B) Pooled data of ramp-evoked currents measured at +65 mV in the absence or presence of Cl-IB-MECA in Cd2+-containing extracellular solution in 7 cells investigated. P = 0.2653, the paired Student t test. (C) Averaged time course of ramp-evoked currents at +65 mV in the presence of Cl-IB-MECA (n = 14), its vehicle (Veh: 0.1% DMSO: n = 3), or Cl-IB-MECA in Cd2+ (n = 7). (D) Original ramp current traces recorded in apamin (100 nM) + tetraethylammonium (TEA, 200 μM) before (apamin + TEA) or during Cl-IB-MECA (100 nM) application in a representative cell. Inset: time course of ramp-evoked currents at +65 mV in the same cell. (E) Averaged Cl-IB-MECA–inhibited currents in the absence (n = 14) or presence of apamin alone (n = 4) or during coapplication with TEA (n = 4). (F) Original ramp current traces recorded before (ctrl) and during 1-mM Cd2+ application in a representative cell where extracellular and intracellular K+ were replaced by equimolar Cs+. Note that in these experimental conditions, a Cd2+-sensitive inward current appears, which presents an I–V relationship typical of Ca2+ currents. Inset: time course of ramp-evoked current measured at the inward peak in the same cell. (G) Net Cd2+-blocked Ca2+ current evoked by the ramp protocol in the same cell. (H) Averaged ramp-evoked currents recorded in Cs+-replacement conditions before (ctrl) or during Cl-IB-MECA (100 nM) application in 5 cells tested. *P = 0.0431, the paired Student t test. (I) Averaged Cl-IB-MECA–inhibited Ca2+ currents in Cs+-replacement experiments. DMSO, dimethyl sulphoxide; DRG, dorsal root ganglion.

Two possibilities exist to explain this phenomenon: (1) A3AR activation directly inhibits SK and BK channels; or (2) A3ARs activation inhibits Ca2+ entry from VDCCs, which, in turn, decreases SK and BK channel opening. To test the latter hypothesis, we blocked all K+ currents by replacing intracellular and extracellular K+ ions with equimolar Cs+. In these experimental conditions, an inward component arose in the ramp protocol peaking around 0 mV (Fig. 4F). This current was identified as a Ca2+ current because it was abolished by extracellular Cd2+ (Figs. 4F and G). When applying Cl-IB-MECA in Cs+-replacement conditions, a significant decrease in inward peak current was observed (Fig. 4H: from −64.3 ± 14.8 pA/pF in control to −41.1 ± 11.4 pA/pF in Cl-IB-MECA, *P = 0.0431, the paired Student t test; n = 5), thus demonstrating that A3AR activation directly inhibited Ca2+ currents.

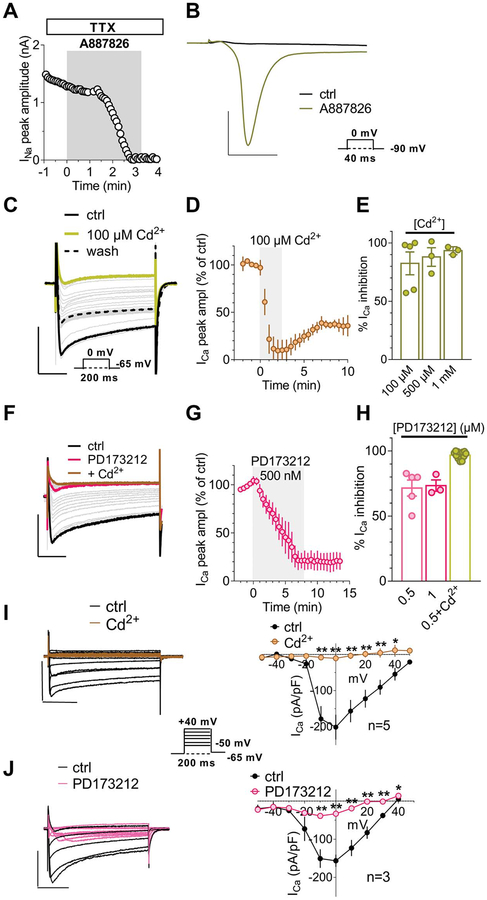

Dorsal root ganglion neurons express different subtypes of Ca2+ currents.46–48,57 To identify which of them are inhibited by the A3AR, we further isolated VDCC-mediated currents by adding the Nav1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.6, and 1.7 blocker TTX (1 μM) plus the Nav1.8 inhibitor A887826 (200 nM, to block this TTX-resistant Na+ channel) to the Cs+-containing extracellular solution. Nav1.8 is known to be expressed at high levels in DRG neurons,9 which we confirmed, because in the presence of 1-μM extracellular TTX, 200-nM A887826 completely blocked residual, TTX-resistant, Na+ currents (Figs. 5A and B). As shown in Figure 5C, under these experimental conditions, we successfully isolated Ca2+ currents activated by a 0-mV voltage step depolarization (200-ms duration), which were completely blocked by 100-μM Cd2+ (Figs. 5C–E). Such Ca2+ currents were predominantly N-type currents because application of selective N-type blocker PD173212 (500 nM: Figs. 5F and G) achieved a >80% block.25,26,50 Residual, PD173212-insensitive (up to 1 μM: Fig. 5H) Ca2+ currents in our experimental conditions were blocked by Cd2+ (Fig. 5H) and were attributed to Cd2+-sensitive L-type and, eventually, R- and/or P/Q-type VDCCs, consistently with a previous report.57

Figure 5.

The major component of Ca2+ currents recorded in DRG neurons is carried by N-type VDCC opening. (A) Time course of Na+ currents recorded in Cs+-replacement conditions in the presence of extracellular TTX (1 μM), Cd2+ (500 μM), and Ni2+ (100 μM) and activated every 5 seconds by a 0-mV step depolarization (40-ms duration, Vh = −90 mV: lower inset in (B)) before or during the application of Nav1.8 blocker A887826 (200 nM). (B) Original current traces recorded before and after 3-minute A887826 application. Scale bars: 3 nA; 10 ms. (C) Original current traces evoked in a typical DRG neuron by a 0-mV step depolarization (200 ms; Vh = −65 mV: lower inset) in the presence of extracellular TTX (1 μM), Ni2+ (100 μM), and A887826 (200 nM) before (ctrl) or during the application of 100-μM Cd2+. Scale bars: 1 nA; 50 ms. (D) Averaged time courses of Ca2+ currents, measured at the inward peak, before and during the application of the nonselective VDCC blocker 100-μM Cd2+ (n = 4). (E) Pooled data of Ca2+ current inhibition in the presence of 100-μM, 500-μM, or 1-mM Cd2+, n = 4. (F) Original current traces evoked in a typical DRG neuron by a 0-mV step depolarization (200 ms; Vh = −65 mV) in the presence of extracellular TTX (1 μM), Ni2+ (100 μM), and A887826 (200 nM) before (ctrl) or during the application of PD173212 (0.5 μM) and, subsequently, 500-μM Cd2+. Scale bars: 1 nA; 50 ms. (G) Averaged time courses of Ca2+ currents before and during the application of selective N-type Ca2+ channel blocker PD173212 (500 nM, n = 4). (H) Pooled data of Ca2+ current inhibition in the presence of 0.5-μM PD173212, 1-μM PD173212, or 0.5-μM PD173212 + 500-μM Cd2+. (I and J) Original current traces (left panels), and respective averaged I–V plots (right panels), of Ca2+ currents evoked by a series of 10 depolarizing voltage steps (from −50 to + 50 mV, 200-ms duration, Vh = −65 mV: see lower inset) before or during 500-μM Cd2+ (I) or 0.5-μM PD173212 (J) application. Scale bars: 1 nA; 50 ms. DRG, dorsal root ganglion; VDCC, voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, paired Student t-test.

Current-to-voltage (I–V plot) relationship of Ca2+ currents activated by a series of depolarizing voltage steps (from −50 to +50 mV, 10-mV increment, 200-ms duration, Vh = −65 mV: inset in Fig. 5I) was consistent with Cd2+-blocked (Fig. 5I) and PD173212-sensitive (Fig. 5J) N-type VDCC activation.

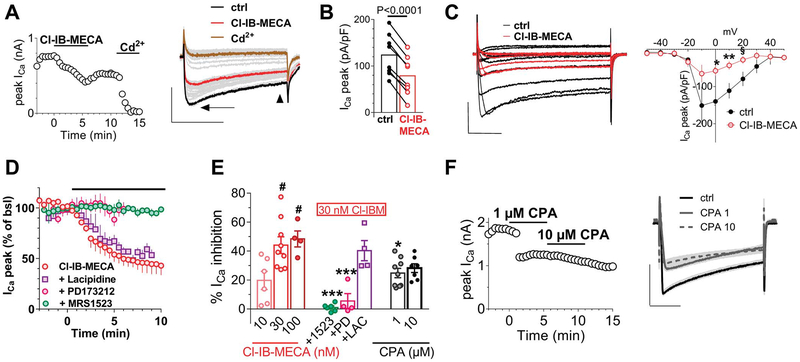

When Cl-IB-MECA was applied in these experimental conditions, a reversible decrease in total Ca2+ currents (both in the peak and steady-state component) was observed within 5 minutes of drug application (Fig. 6A). The I–V plot of such Ca2+ conductances (Fig. 6C) demonstrated that the A3AR agonist significantly inhibited VDCCs from 0 to +20 mV (the paired Student t test, n = 5). The Cl-IB-MECA effect was significant in 8 cells tested (Fig. 6B), either as peak current amplitude (arrow in the right panel of Fig. 6A or Fig. 6B) or at the steady state (arrowhead in the right panel of Fig. 6A: from 57.4 ± 14.5 to 39.8 ± 10.2 pA/pF; P = 0.0174, the paired Student t test). However, the A3AR agonist apparently did not change the Ca2+ current kinetics because the time to peak was unaffected (from 15.1 ± 2.2 to 15.7 ± 3.0 ms; P = 0.5553, the paired Student t test, data not shown). Cl-IB-MECA–mediated inhibition of VDCCs was concentration dependent with a maximal effect observed at 30 nM (Fig. 6E), in accordance with ramp experiments, and completely prevented by the A3AR antagonist MRS1523 (100 nM) and by the selective N-type channel blocker PD173212 (500 nM) but not by the selective, at least at 1-μM concentration,6 L-type blocker lacidipine (1 μM: Figs. 6D and E). The above data demonstrate that A3AR activation selectively inhibits N-type Ca2+ currents in rat DRG neurons.

Figure 6.

Cl-IB-MECA inhibits N-type Ca2+ currents in DRG neurons. (A) Left panel: time course of peak Ca2+ currents (ICa) evoked by a 0-mV step depolarization in a typical DRG neuron. Note that Cl-IB-MECA (30 nM) inhibits Ca2+ currents that were completely abolished by a subsequent 500-μM Cd2+ application. Right panel: original current traces recorded in the same cell at significant time points. Scale bars: 0.5 nA, 100 ms. Arrow indicates peak Ca2+ currents, and arrowhead indicates steady-state Ca2+ currents. (B) Pooled data of peak ICa measured in the absence or presence of Cl-IB-MECA in 8 cells investigated. P < 0.0001, the paired Student t test. (C) Left panel: original Ca2+ current traces evoked by a series of depolarizing voltage steps (inset) before (ctrl) or after Cl-IB-MECA (30 nM) application in a representative cell. Right panel: averaged I–V plot of Ca2+ currents measured at the peak in 5 cells tested. *P = 0.0106; **P = 0.0066; § P = 0.0105, the paired Student t test. Scale bars: 0.5 nA, 50 ms. (D) Averaged time courses of peak Ca2+ current, expressed as % of baseline values, measured before or after the application of Cl-IB-MECA in different experimental groups. (E) Pooled data of Cl-IB-MECA–or CPA-inhibited peak Ca2+ currents at different agonist concentrations, or in 30-nM Cl-IB-MECA during coapplication with the A3AR antagonist MRS1523 (1523, 100 nM) or with the selective N-type and L-type Ca2+ channels blockers PD173212 (PD, 0.5 μM) and lacidipine (LAC, 1 μM), respectively. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.0001 vs 30-nM Cl-IB-MECA; #P < 0.05 vs 10-nM Cl-IB-MECA, one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni posttest. (F) Left panel: time course of peak ICa evoked by a 0-mV step depolarization in a typical DRG neuron in the absence or presence of N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CPA: 1–10 μM). Right panel: original current traces recorded in the same cell at significant time points. Scale bars: 1 nA, 100 ms. ANOVA, analysis of variance; DRG, dorsal root ganglion.

In the attempt to compare A3AR- vs A1AR-mediated effects on VDCCs, we applied the A1AR-selective agonist CPA. As shown in Figures 6E and F, CPA inhibited Ca2+currents by 24.8 ± 3.2% (n = 9) and by 24.1 ± 3.0% (n = 7) at 1 and 10 μM concentrations, respectively. Of note, Ca2+ current inhibition measured in the presence of 1-μM CPA was significantly smaller compared with the Cl-IB-MECA–mediated effect (44.1 ± 5.6% inhibition in the presence of 30-nM;Cl-IB-MECA vs 24.8 ± 3.2% inhibition in the presence of 1-μM CPA, P = 0.0464, one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni posttest, Fig. 6E).

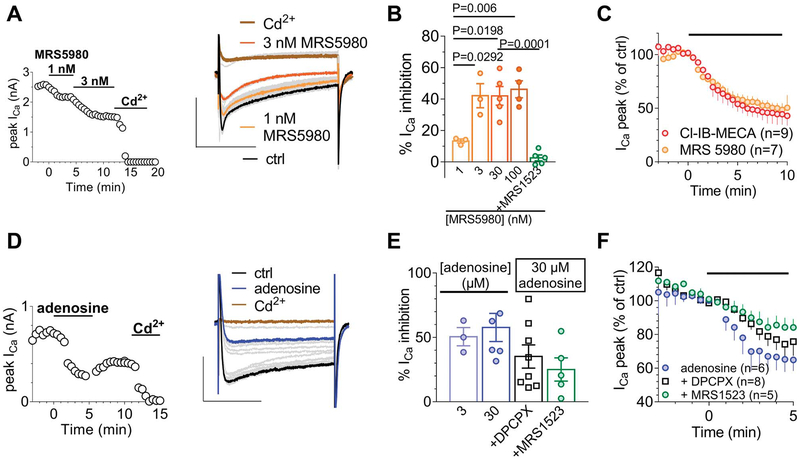

The newly synthetized A3AR agonist MRS5980 mimicked the Cl-IB-MECA effect in inhibiting Ca2+ currents (Figs. 7A and C) but with higher efficacy, showing a maximal VDCC inhibition at 3 nM concentration (Fig. 7B) compared with 30 nM for Cl-IB-MECA. Furthermore, the MRS5980-mediated effect was prevented in the presence of A3AR antagonist MRS1523 (100 nM; Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

The inhibitory effect of Cl-IB-MECA on N-type Ca2+ currents in DRG neurons is mimicked by the newly synthetized A3AR agonist MRS5980 and by adenosine. (A) Left panel: time course of peak ICa in a typical DRG neuron before and after MRS5980 (30 nM) and Cd2+ (500 μM) application. Right panel: original current traces recorded in the same cell at significant time points. Scale bars: 2 nA; 100 ms. (B) Pooled data of MRS5980-inhibited peak Ca2+ current at different agonist concentrations or in the presence of 30-nM MRS5980 + 100-nM MRS15253. One-way ANOVA; Bonferroni posttest. (C) Averaged time courses of peak ICa before or during Cl-IB-MECA (30 nM) or MRS5980 (3 nM) application. (D) Left panel: time course of peak ICa in a typical DRG neuron before and after adenosine (30 nM) and Cd2+ (500 μM) application. Right panel: original current traces recorded in the same cell at significant time points. (E) Pooled data of adenosine-inhibited peak Ca2+ currents at different agonist concentrations or in the presence of 30-μM adenosine + the A3AR antagonist MRS15253 (100 nM) or the A1AR antagonist DPCPX (500 nM). No significant difference was found between any of the experimental groups (one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni posttest). (F) Averaged time courses of peak Ca2+ current amplitude before or after adenosine (30 μM) application alone or in the presence of DPCPX (500 nM) or MRS1523 (100 nM). ANOVA, analysis of variance; DRG, dorsal root ganglion.

To explore the contribution of A3AR-mediated inhibition of VDCCs when the endogenous agonist is present in the extracellular space, we applied adenosine (30 μM) in the absence or presence of a selective adenosine A1 or A3AR antagonist, DPCPX or MRS1523, respectively. As expected from published data,11,36 adenosine inhibited Cd2+-sensitive Ca2+ currents with a maximal effect observed at 30 μM (Fig. 7E). Of note, the effect induced by 30-mM adenosine was blocked by 39.1 ± 9.0% in the presence of DPCPX (500 nM) and by 56.6 ± 9.0% in the presence of MRS1523 (100 nM; Figs. 7E and F). No significant difference was found between DPCPX- and MRS1523-mediated inhibition of adenosine effects (one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni posttest).

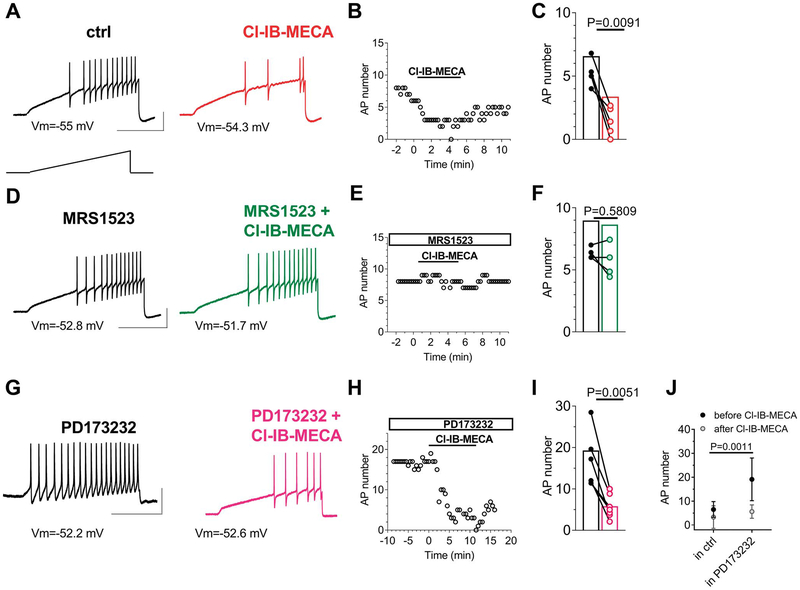

Finally, we evaluated the impact of selective A3AR activation on neuronal excitability. We induced AP firing by injecting a depolarizing ramp current from the resting membrane potential. As shown in Figure 8A, this protocol induced repetitive firing in DRG neurons, which was markedly reduced in the presence of Cl-IB-MECA (Figs. 8A and B). The effect was statistically significant in 6 cells tested (Fig. 8C) and prevented in the presence of A3AR antagonist MRS1523 (100 nM; Figs. 8D–F) but not by the N-type VDCC blocker PD173212 (1 μM; Figs. 8G–I). Of note, a two-way ANOVA comparison between the effect of Cl-IB-MECA when applied alone (Fig. 8J, left column: “in ctrl”) or applied in the presence of PD173212 (Fig. 8J, right column: “in PD173212”) highlighted that: (1) a statistical difference was found between the number of APs recorded in control conditions or in the presence of PD173212 alone (Fig. 8J, black circles: before Cl-IB-MECA: 6.5 ± 1.3 APs in ctrl, n = 6, vs 19.1 ± 3.4 APs in PD173212, n = 7; P = 0.0011), indicating that N-type VDCC block exerts a proexcitatory effect on cells firing; and (2) no difference was found in the inhibitory effect of Cl-IB-MECA when applied in the absence or presence of PD173212 (gray circles: after Cl-IB-MECA: 3.3 ± 1.9 APs in Cl-IB-MECA, n = 6, vs 5.6 ± 1.1 APs in Cl-IB-MECA + PD173212; P = 0.7109), indicating that Cl-IB-MECA effect on firing is not occluded by N-type VDCC. To corroborate the proexcitatory effect of N-type VDCC block, we applied PD173212 alone in a separate group of cells, and we observed a significant increase in AP firing (Suppl. Fig. 3, available at http://links.lww.com/PAIN/A733) accompanied by a significant cell depolarization (Suppl. Fig. 3B and C, available at http://links.lww.com/PAIN/A733; and Table 1: from −63.6 ± 2.9 mV in control to −59.7 ± 3.6 mV in 1-μM PD173212; P = 0.0165, the paired Student t test, n = 7) and lowering of AP threshold (Table 1: from −12.7 ± 1.9 mV in control to −14.1 ± 1.51 mV in 1-μM PD173212; P = 0.0491, the paired Student t test, n = 7). Furthermore, in accordance with KCa inhibition and in particular with BK channel block, we measured a significant increase in AP duration (from 3.9 ± 0.7 ms in control to 4.5 ± 0.6 ms in 1-μM PD173212; P = 0.0089, the paired Student t test, n = 7) and a reduction in fast afterhyperpolarization (from 46.0 ± 2.1 mV in control to 34.8 ± 4.4 mV in 1-μM PD173212; P = 0.0168, the paired Student t test, n = 7) on PD173212 superfusion (see Table 1). Other AP parameters (reported in Table 1) were not modified by any treatment. In the attempt to identify the mechanism by which A3AR inhibits cell firing, we tested the effect of Cl-IB-MECA on Na+ currents with no obvious differences detected in its presence (Suppl. Figs. 4A and B, available at http://links.lww.com/PAIN/A733), either on current amplitude (Suppl. Fig. 4C, available at http://links.lww.com/PAIN/A733) or time to peak (Suppl. Fig. 4D, available at http://links.lww.com/PAIN/A733).

Figure 8.

Cl-IB-MECA inhibits AP firing in DRG neurons. (A) Original AP traces evoked in a typical DRG neuron by a 1-second depolarizing ramp current injection (lower inset) recorded before (black trace) or after (red trace) 5-minute Cl-IB-MECA (100 nM) application. (B) Time course of AP number in the same cell. (C) Pooled data of AP number measured before or after 5-minute Cl-IB-MECA application in 6 cells tested. P = 0.0091, the paired Student t test. (D) Original AP traces evoked by a 1-second depolarizing ramp current injection recorded before (black trace) or after (green trace) 5-minute Cl-IB-MECA (100 nM) application in the presence of MRS1523 (100 nM). (E) Time course of AP number in the same cell. (F) Pooled data of AP number measured before or after 5-minute Cl-IB-MECA application in the presence of MRS1523 in 5 cells tested. P = 0.5809, the paired Student t test. (G) Original AP traces evoked by a 1-second depolarizing ramp current injection recorded before (black trace) or after (purple trace) 5-minute Cl-IB-MECA (100 nM) application in the presence of PD173212 (1 μM). (H) Time course of AP number in the same cell. (I) Pooled data of AP number measured before or after 5-minute Cl-IB-MECA application in the presence of PD173212 in 6 cells tested. The paired Student t test. Scale bars: 50 mV; 500 ms. (J) Comparison between the effect of Cl-IB-MECA on AP firing when applied alone (“in ctrl,” n = 6) or when applied in the presence of 1-μM PD173212 (“in PD173212,” n = 7). Treatment (Cl-IB-MECA): F(1,22) = 11.46, P = 0.0027; time (before/after): F(1,22) = 14.27, P = 0.0010; interaction: F(1,22) = 5.416, P = 0.0029; 2-way ANOVA, Bonferroni posttest. Note that there is a statistical difference (**P = 0011) between the AP number recorded before Cl-IB-MECA application in the ctrl group (“in ctrl”) or in the PD173212 group (“in PD173212”) but not between the AP number recorded after Cl-IB-MECA application in the ctrl group or in the PD173212 group (P = 0.7109). ANOVA, analysis of variance; AP, action potential; DRG, dorsal root ganglion.

3.2. Intracellular Ca2+ measurements confirmed that A3AR activation inhibits electrical field stimulation–evoked Ca2+ transients in isolated dorsal root ganglion neurons

Fura-2–loaded DRG neurons analysed by transmitted light and fluorescence showed a round morphology with an average diameter of 27.6 ± 0.3 μm (n = 318).

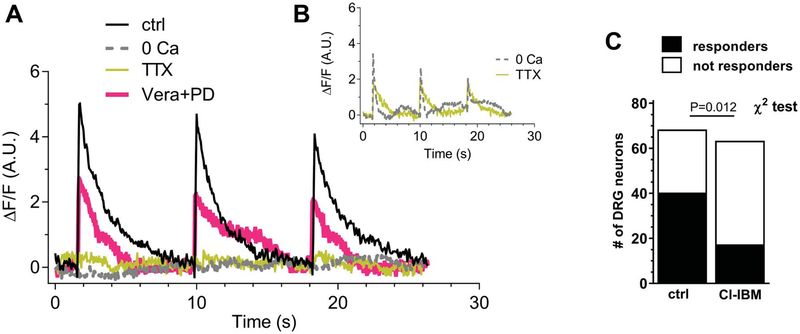

In control conditions (standard extracellular solution), 60% (40 of 68) of the DRG neurons presented electrically evoked Ca2+ transients on 0.1-Hz field stimulation. These cells were defined as “spiking” cells. The dynamic of cytosolic Ca2+ increase presented a rapid onset and a return to basal Ca2+ levels following a monoexponential kinetic. Figure 9A shows typical Ca2+ transient traces in control conditions, in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (0[Ca2+]out), in the presence of TTX + A887826, or in the presence of verapamil + PD173212.

Figure 9.

A3 receptor stimulation reduces electrically evoked and TTX-sensitive intracellular Ca2+ transients in isolated DRG neurons. (A) Typical time courses of Ca2+ transient induce in DRG neurons by 0.1-Hz electrical field stimulation in control condition (ctrl: black trace), extracellular free-Ca2+ solution (0[Ca2+]out: dotted trace), 1-μM tetrodotoxin + 200-nM A887826 (TTX: yellow trace), or verapamil (VERA; 1 μM) + PD173212 (PD; 500 nM). (B) Time courses of spiking cells recorded in 0[Ca2+]out (dotted trace) or in TTX + A887826 (gray trace). (C) Numbers of spiking or not spiking DRG neurons in control conditions or after preincubation with 30-nM Cl-IB-MECA. Statistical analysis was performed using the χ2 test. DRG, dorsal root ganglion.

In 0[Ca2+]out, only 4 of 37 (10.8%, Fig. 9B) analysed DRG neurons responded to electrical field stimulation (P = 0.003 vs control, the χ2 test, Table 2). Indeed, as shown in a typical trace in Figure 9A (dotted line), the majority of analysed cells did not show Ca2+ transients in 0[Ca2+]out. Figure 9B depicts Ca2+ transients in 1 of the 4 spiking cells in 0[Ca2+]out. In those 4 spiking cells, the ΔF/F was slightly reduced, whereas the monoexponential decay phase was significantly reduced (Table 2). We supposed that in the 4 of 37 cells oscillating in 0[Ca2+]out, the electrical field stimulation could induce a Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, as already shown,45 or, alternatively, that incomplete Ca2+ buffering was achieved.

Table 2.

ΔF/F and decay time (τ) measured in spiking DRG neurons during electrical field stimulation, according to treatments.

| Treatment | No. of spiking cells out of analyzed cells | ΔF/F (A.U.) (spiking) | τ (decay time) (s) (spiking) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 40 out of 68 | 3.8 ± 0.47 | 1.24 ± 0.087 |

| 0[Ca2+] out | 4 out of 37 | 2.2 ± 0.81 | 0.51 ± 0.082* |

| TTX + A887826 | 12 out of 55 | 1.6 ± 0.50 | 0.98 ± 0.159 |

| Verapamil + PD173212 | 17 out of 37 | 1.6 ± 0.38† | 0.96 ± 0.101 |

| CI-IB-MECA | 17 out of 64 | 5.6 ± 0.77 | 1.33 ± 0.106‡ |

The decay time (tau, τ) was calculated according to the following equation: .

One-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni posttest.

P = 0.006 vs control.

P = 0.03.

P = 0.004 vs 0[Ca2+].

ANOVA, analysis of variance; A.U., arbitrary unit; DRG, dorsal root ganglion.

In the presence of TTX + A887826, only 12 of 55 (21.8% Fig. 9B) DRG neurons were spiking (P = 0.012 vs control, the χ2 test), and in the majority of cells, we did not observe any Ca2+ increase (Fig. 9A). Figure 9B displays the trace of 1 of 12 responder cells in TTX + A887826. Among them, either ΔF/F or tau was slightly (but not significantly) reduced (Table 2). In finding an explanation to the observation that 12 of 55 cells still oscillated in the presence of TTX plus A887826, we have to consider that A887826 block of TTX-resistant Na+ currents is dependent on Nav1.8 channels being in the open state.60 In fact, A887826 potently (IC50 = 8 nM) inhibits TTX-resistant Na+ currents in rat DRG neurons in a voltage-dependent way, being about 8-fold less potent at relatively hyperpolarized (Vm <−60 mV) membrane voltages in comparison with −40 mV-clamped cells.60 Alternatively, we can envisage that in those 12 spiking cells, field depolarization was sufficient to activate VDCCs, in line with previous observation.36

The block of L+N-type VDCCs by verapamil (1 μM) + PD173212 (500 nM) induced a significant reduction in ΔF/F (Table 1, P = 0.003, ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test) without a significant decrease in tau. The number of spiking cells under these experimental conditions was 17 of 37 cells investigated (45.9%, not significant vs control: P = 0.658, the χ2 test).

Preincubation with Cl-IB-MECA significantly decreased the number of spiking cells (17 of 64: 23%; P = 0.012, the χ2 test) as compared to control (Fig. 9C). However, Ca2+ parameters of spiking cells were not modified by this treatment (Table 2).

4. Discussion

In the present work, we investigated the expression and electrophysiological effects of A3AR in primary sensory neurons. We report here evidence of A3AR mRNA expression in the rat DRG, and we demonstrate that A3AR activation inhibits both pronociceptive N-type VDCC activation and AP firing in isolated DRG neurons. The bulk of evidence in studies of in vivo animal models indicates that adenosine is a powerful antihyperalgesic compound,10 with a crucial role recognized for A1AR activation. Of note, the A3AR has recently gained attention because its activation provides pain relief without adverse side effects.30

In this study, we demonstrated by RT-PCR that A3AR mRNA is abundant in DRG homogenate and by immunocytochemistry that A3AR protein is present on both neurons and glia. It should be noted that although it is generally accepted that A3ARs are expressed either by rat or human DRG neurons, a debate exists concerning their presence in the mouse. Based on mRNA sequencing, it appears that mouse DRG neurons do not express A3AR.44,53

We then explored the A3AR functional role in DRG neurons by performing patch-clamp recording in the absence or presence of 2 different receptor agonists: the commercially available Cl-IB-MECA and the new highly selective A3AR agonist MRS5980.12,51 Our first approach was to investigate the effects of A3AR under basal (nonpharmacologically manipulated) conditions by using a voltage-ramp protocol to activate a wide range of voltage-dependent conductances. We found that the prototypical A3AR agonist Cl-IB-MECA reduced total outward K+ currents evoked by the ramp. It is worth stressing that when tested for TRP responses, the vast majority of neurons responding to Cl-IB-MECA were also sensitive to TRPA1 and/or TRPV1 agonists, AITC and capsaicin, respectively, and presented an average cell diameter of 25 μm, thus being considered as “nociceptors.”

When analyzed in detail, the Cl-IB-MECA effect on ramp K+ currents was found to be dependent on Ca2+ channel opening because it was prevented by the nonselective VDCC blocker Cd2+. Indeed, in accordance with previous works,39,41 we demonstrated that DRG neurons express Ca2+-activated K+ channels (KCa) as indicated by the observation that extracellular Cd2+ inhibits 34.0% of total outward currents evoked by the ramp. At variance, Cl-IB-MECA, that indirectly reduces Ca2+ currents through A3AR activation, inhibits 23.3% of total ramp-evoked outward currents. Among KCa, SK and BK channels are involved in the Cl-IB-MECA effect, as demonstrated by the fact that apamin plus TEA (200 μM) prevented ramp current inhibition.

Different VDCC types in DRG neurons have been described: P/Q and N types, encoded by Cav2.1 and Cav2.2, respectively, which are mainly involved in neurotransmitter release, and R, L, and T types, encoded by Cav2.3, Cav1.1 to 1.4, and Cav3.1 to3.3, respectively.46,47,57 When VDCC-mediated currents were studied in isolation, A3AR activation selectively inhibited N-type Ca2+ channels because the Cl-IB-MECA effect was prevented by the ω-CTX analogue PD173212 but not by the L-type blocker lacidipine. We conclude that A3AR activation directly inhibits Ca2+ entry by VDCC on ramp depolarization and consequently reduces BK and SK channel opening.

It is known that A1ARs also inhibit VDCCs in DRG neurons.11 Consistently, we observed a 24.8 ± 3.2% Ca2+ current decrease in the presence of CPA. When testing the endogenous agonist effects, adenosine-mediated inhibition of Ca2+ currents was either sensitive to the A3AR blocker MRS1523 or to the A1AR antagonist DPCPX, demonstrating that these 2 AR subtypes are major mediators of adenosine effects in these cells. Of note, the CPA-mediated Ca2+ current inhibition (24.8 ± 3.2%) was significantly smaller compared with Cl-IB-MECA effect (44.1 ± 5.6%) indicating a prominent functional role of A3AR vs A1AR in this cell type.

Gi-coupled receptors, eg, A3 and A1ARs, as well as μ-opioid receptors, can inhibit VDCC activation, and the mechanism may occur through the Gβ,γ subunit binding directly to the channel protein.59 Of note, the A3AR has also been found to activate secondarily Gq proteins,27 which could also modulate VDCCs.24 Here, we describe A3AR-induced inhibition of VDCCs for the first time in DRG neurons, but we have not determined the G-protein pathway involved. Furthermore, N-type channels are known to promote nociception by providing more than 60% of the neurotransmitter release by DRG neurons to lamina I dorsal horn neurons.21,23 Previous observations demonstrate that N-type VDCCs blockers result in analgesia in a range of pain models,17,31,55 and ziconotide, the first-choice compound among ω-CTX analogues, is in clinical use as an intrathecal medication for chronic pain in the United States.1,2 Of note, a direct block of N-type Ca2+ channels, as that achieved by ziconotide or ω-CTXs, is associated with serious side effects (psychological and neuropsychiatric symptoms including depression, cognitive impairment, and hallucinations; anxiety; panic attacks; ataxia; asthenia; headache; and dysesthesia).35 Interestingly, an “indirect” VDCC modulation as that accomplished by A3AR activation could represent a suitable approach to pain control without adverse side effects.

Beyond VDCC inhibition, we also demonstrated that Cl-IB-MECA decreases the number of APs elicited by a depolarizing ramp current injection in isolated DRG neurons. This effect, also shared by μ-opioid agonists,3,49,54 could be a further crucial mechanism by which the A3AR exerts pain relief. The Cl-IB-MECA effect was blocked by the A3AR antagonist MRS1523 but was insensitive to the N-type Ca2+ channel blocker PD173212, demonstrating that A3AR-induced inhibition of cell excitability is not mediated by N-type VDCC inhibition. Indeed, we demonstrated here that a direct block of N-type Ca2+ channels by PD173212 induces an opposite effect on cell firing, ie, it increases the number of evoked APs, depolarizes cell membrane, and reduces voltage threshold. This indicates that a reduced Ca2+ influx through N-type VDCCs is proexcitatory at a somatic level. Such an effect could be secondary to a reduced activation of KCa channels as indicated by previous data showing that either BK or SK channel inhibition increases DRG excitability.32,41,61 In light of this information, it appears that A3AR signaling in sensory neurons is complex and could lead to contradictory effects: VDCC inhibition induces, on one hand, a reduction in neurotransmitter release at the presynaptic level, thus providing pain control; on the other hand, it decreases KCa opening at the somatic level, thus increasing neuronal excitability and producing a possible proalgesic effect. Indeed, multiple studies demonstrate that A3AR agonists, applied either centrally34,56,58 or peripherally,14,29,42 are potent antihyperalgesic compounds.30 This observation supports the notion that the inhibitory effect of Cl-IB-MECA on VDCCs at a presynaptic level prevails over the potentially proalgesic A3AR effect at a somatic level. Furthermore, the potentially proalgesic effect of Cl-IB-MECA at a somatic level is masked by another, still unexplored, inhibitory A3AR effect on cell firing, which could provide a therapeutic advantage of an A3AR agonist over a direct Ca2+ channel blocker. This effect remains unexplained and will be addressed in our future work; our preliminary experiments revealed no obvious differences in Na+ currents evoked in the absence or presence of Cl-IB-MECA.

Importantly, when we measured the intracellular Ca2+ rise after electrical field stimulation, we observed an overall reduction in the excitability of the DRG neuronal population in the presence of the A3AR agonist. Thus, Cl-IB-MECA significantly reduced the number of cells responding to 0.1 Hz stimulation, even if it did not change the dynamics of the Ca2+ rise (ΔF/F or tau) once Ca2+ spikes were triggered.

It must be pointed out that the above-mentioned effects may not be the only mechanism by which A3AR agonists exert antihyperalgesia. Research studies have described a peripheral A3AR effect on cytokine release during chemotherapeutic-induced neuropathic pain.29,56 Additional A3AR-mediated modulation of nociception could possibly arise from receptor stimulation at a central level, ie, in thalamic nuclei.

We conclude that selective A3AR stimulation inhibits N-type VDCC opening, leading to a reduction in neurotransmitter release, and reduces electrically evoked excitation in isolated rat DRG neurons. Both these effects, as independent mechanisms, may be important in accounting for A3AR’s pain-relieving effect and support the notion that an A3AR-based therapy represents an important strategy to alleviate pain in different pathologies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the University of Florence (Fondi Ateneo Ricerca), from MIUR-PRIN 2015 (2015E8EMCM_002; A.M.P.), and from the NIDDK Intramural Research Program (ZIADK031117; K.J.). The authors thank Dr Niccolò Manetti for his support in electrophysiological experiments, Dr Davide Lecca from the University of Milan for kindly providing A3AR antibody, John Bennett (NIDDK) for proofreading, and Prof. Fiorella Casamenti for the use of Olympus BX40 microscope.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.painjournalonline.com).

Conflict of interest statement

D.S. is a co-founder of BioIntervene, Inc, that licensed related intellectual property from Saint Louis University. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Appendix A. Supplemental digital content

Supplemental digital content associated with this article can be found online at http://links.lww.com/PAIN/A733.

References

- [1].Adler JA, Lotz NM. Intrathecal pain management: a team-based approach. J Pain Res 2017;10:2565–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Brookes ME, Eldabe S, Batterham A. Ziconotide monotherapy: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Curr Neuropharmacol 2017;15:217–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cai Q, Qiu CY, Qiu F, Liu TT, Qu ZW, Liu YM, Hu WP. Morphine inhibits acid-sensing ion channel currents in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Brain Res 2014;1554:12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Coppi E, Maraula G, Fumagalli M, Failli P, Cellai L, Bonfanti E, Mazzoni L, Coppini R, Abbracchio MP, Pedata F, Pugliese AM. UDP-glucose enhances outward K plus currents necessary for cell differentiation and stimulates cell migration by activating the GPR17 receptor in oligodendrocyte precursors. Glia 2013;61:1155–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Coppi E, Pedata F, Gibb AJ. P2Y1 receptor modulation of Ca2+-activated K+ currents in medium-sized neurons from neonatal rat striatal slices. J Neurophysiol 2012;107:1009–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].De Peoli P, Cerbai E, Koidl B, Kierchengast M, Sartiani L, Mugelli A. Selectivity of different calcium antagonists on T- and L-type calcium currents in Guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. Pharmacol Res 2002;46: 491–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Di Cesare Mannelli L, Pacini A, Corti F, Boccella S, Luongo L, Esposito E, Cuzzocrea S, Maione S, Calignano A, Ghelardini C. Antineuropathic profile of N-palmitoylethanolamine in a rat model of oxaliplatin-induced neurotoxicity. PLoS One 2015;10:e0128080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Di Cesare Mannelli L, Zanardelli M, Landini I, Pacini A, Ghelardini C, Mini E, Bencini A, Valtancoli B, Failli P. Effect of the SOD mimetic MnL4 on in vitro and in vivo oxaliplatin toxicity: possible aid in chemotherapy induced neuropathy. Free Radic Biol Med 2016;93:67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dib-Hajj SD, Black JA, Waxman SG. Voltage-gated sodium channels: therapeutic targets for pain. Pain Med 2009;10:1260–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dickenson AH, Suzuki R, Reeve AJ. Adenosine as a potential analgesic target in inflammatory and neuropathic pains. CNS Drugs 2000;13:77–85. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Dolphin AC, Forda SR, Scott RH. Calcium-dependent currents in cultured rat dorsal-root ganglion neurons are inhibited by an adenosine analog. J Physiol 1986;373:47–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fang ZZ, Tosh DK, Tanaka N, Wang H, Krausz KW, O’Connor R, Jacobson KA, Gonzalez FJ. Metabolic mapping of A3 adenosine receptor agonist MRS5980. Biochem Pharmacol 2015;97:215–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Field MJ, Li Z, Schwarz JB. Ca2+ channel alpha2-delta ligands for the treatment of neuropathic pain. J Med Chem 2007;50:2569–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ford A, Castonguay A, Cottet M, Little JW, Chen Z, Symons-Liguori AM, Doyle T, Egan TM, Vanderah TW, De Koninck Y, Tosh DK, Jacobson KA, Salvemini D. Engagement of the GABA to KCC2 signaling pathway contributes to the analgesic effects of A3AR agonists in neuropathic pain. J Neurosci 2015;35:6057–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Linden J, Muller CE. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXI. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors-an update. Pharmacol Rev 2011;63:1–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fusi C, Materazzi S, Benemei S, Coppi E, Trevisan G, Marone IM, Minocci D, De Logu F, Tuccinardi T, Di Tommaso MR, Susini T, Moneti G, Pieraccini G, Geppetti P, Nassini R. Steroidal and non-steroidal third-generation aromatase inhibitors induce pain-like symptoms via TRPA1. Nat Commun 2014;5:5736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gandini MA, Sandoval A, Felix R. Toxins targeting voltage-activated Ca2+ channels and their potential biomedical applications. Curr Top Med Chem 2015;15:604–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Goldberg DS, McGee SJ. Pain as a global public health priority. BMC Public Health 2011;11:770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gross RA, Macdonald RL, Ryanjastrow T. 2-Chloroadenosine reduces the N-calcium current of cultured mouse sensory neurons in a pertussis toxin-sensitive manner. J Physiol 1989;411:585–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hannon HE, Atchison WD. Omega-Conotoxins as experimental tools and therapeutics in pain management. Mar Drugs 2013;11:680–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Harding LM, Beadle DJ, Bermudez I. Voltage-dependent calcium channel subtypes controlling somatic substance P release in the peripheral nervous system. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 1999;23:1103–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Harper AA, Lawson SN. Conduction-velocity is related to morphological cell type in rat dorsal-root ganglion neurons. J Physiol 1985;359:31–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Heinke B, Balzer E, Sandkuhler J. Pre- and postsynaptic contributions of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels to nociceptive transmission in rat spinal laminal neurons. Eur J Neurosci 2004;19:103–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Heneghan JF, Mitra-Ganguli T, Stanish LF, Liu LW, Zhao RB, Rittenhouse AR. The Ca2+ channel beta subunit determines whether stimulation of G(q)-coupled receptors enhances or inhibits N current. J Gen Physiol 2009;134:369–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hu LY, Ryder TR, Rafferty MF, Dooley DJ, Geer JJ, Lotarski SM, Miljanich GP, Millerman E, Rock DM, Stoehr SJ, Szoke BG, Taylor CP, Vartanian MG. Structure-activity relationship of N-methyl-N-aralkyl-peptidylamines as novel N-type calcium channel blockers. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 1999; 9:2151–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hu LY, Ryder TR, Rafferty MF, Feng MR, Lotarski SM, Rock DM, Sinz M, Stoehr SJ, Taylor CP, Weber ML, Bowersox SS, Miljanich GP, Millerman E, Wang YX, Szoke BG. Synthesis of a series of 4-benzyloxyaniline analogues as neuronal N-type calcium channel blockers with improved anticonvulsant and analgesic properties. J Med Chem 1999;42:4239–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jacobson KA, Merighi S, Varani K, Borea PA, Baraldi S, Tabrizi MA, Romagnoli R, Baraldi PG, Ciancetta A, Tosh DK, Gao ZG, Gessi S. A3 adenosine receptors as modulators of inflammation: from medicinal chemistry to therapy. Med Res Rev 2018;38:1031–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Jain KK. An evaluation of intrathecal ziconotide for the treatment of chronic pain. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2000;9:2403–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Janes K, Esposito E, Doyle T, Cuzzocrea S, Tosh DK, Jacobson KA, Salvemini D. A3 adenosine receptor agonist prevents the development of paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain by modulating spinal glial-restricted redox-dependent signaling pathways. PAIN 2014;155:2560–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Janes K, Symons-Liguori AM, Jacobson KA, Salvemini D. Identification of A3 adenosine receptor agonists as novel non-narcotic analgesics. Br J Pharmacol 2016;173:1253–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lee S Pharmacological inhibition of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels for chronic pain relief. Curr Neuropharmacol 2013;11:606–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Li W, Gao SB, Lv CX, Wu Y, Guo ZH, Ding JP, Xu T. Characterization of voltage- and Ca2+ -activated K+ channels in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Cell Physiol 2007;212:348–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Little J, Janes K, Chen Z, Wahlman C, Tosh D, Jacobson K, Salvemini D. Supraspinal adenosine A3 receptor (A3AR) activation reverses chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain through an IL-10 dependent mechanism. J Pain 2015;16:S57. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Little JW, Ford A, Symons-Liguori AM, Chen ZM, Janes K, Doyle T, Xie J, Luongo L, Tosh DK, Maione S, Bannister K, Dickenson AH, Vanderah TW, Porreca F, Jacobson KA, Salvemini D. Endogenous adenosine A3 receptor activation selectively alleviates persistent pain states. Brain 2015;138:28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lynch SS, Cheng CM, Yee JL. Intrathecal ziconotide for refractory chronic pain. Ann Pharmacother 2006;40:1293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Macdonald RL, Skerritt JH, Werz MA. Adenosine agonists reduce voltage-dependent calcium conductance of mouse sensory neurons in cell-culture. J Physiol 1986;370:75–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Maloy C, Janes K, Bryant L, Tosh D, Jacobson K, Salvemini D. A3 adenosine receptor agonists reverse established oxaliplatin-induced neuropathic pain through an IL-10 mediated mechanism of action in spinal cord. J Pain 2014;15:S60. [Google Scholar]

- [38].McDowell GC, Pope JE. Intrathecal ziconotide: dosing and administration strategies in patients with refractory chronic pain. Neuromodulation 2016;19:522–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Mongan LC, Hill MJ, Chen MX, Tate SN, Collins SD, Buckby L, Grubb BD. The distribution of small and intermediate conductance calcium-activated potassium channels in the rat sensory nervous system. Neuroscience 2005;131:161–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Nassini R, Fusi C, Materazzi S, Coppi E, Tuccinardi T, Marone IM, De Logu F, Preti D, Tonello R, Chiarugi A, Patacchini R, Geppetti P, Benemei S. The TRPA1 channel mediates the analgesic action of dipyrone and pyrazolone derivatives. Br J Pharmacol 2015;172:3397–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Pagadala P, Park CK, Bang SS, Xu ZZ, Xie RG, Liu T, Han BX, Tracey WD, Wang F, Ji RR. Loss of NR1 subunit of NMDARs in primary sensory neurons leads to hyperexcitability and pain hypersensitivity: involvement of Ca2+-activated small conductance potassium channels. J Neurosci 2013;33:13425–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Paoletta S, Tosh DK, Finley A, Gizewski ET, Moss SM, Gao ZG, Auchampach JA, Salvemini D, Jacobson KA. Rational design of sulfonated A3 adenosine receptor-selective nucleosides as pharmacological tools to study chronic neuropathic pain. J Med Chem 2013;56:5949–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Pizzo PA, Clark NM. Alleviating suffering 101-pain relief in the United States. N Engl J Med 2012;366:197–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ray P, Torck A, Quigley L, Wangzhou A, Neiman M, Rao C, Lam T, Kim JY, Kim TH, Zhang MQ, Dussor G, Price TJ. Comparative transcriptome profiling of the human and mouse dorsal root ganglia: an RNA-seq-based resource for pain and sensory neuroscience research. PAIN 2018;159:1325–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Scarlett SS, White JA, Blackmore PF, Schoenbach KH, Kolb JF. Regulation of intracellular calcium concentration by nanosecond pulsed electric fields. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009;1788:1168–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]