Abstract

Background

Restoring knee muscle strength after an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction remains challenging. Improvement of rehabilitation program specificity demands additional knowledge on knee muscle strength deficits associated with the graft used for ACL reconstruction.

Purpose

This study aimed to investigate the effects of graft used for ACL reconstruction on the knee muscle strength and balance assessed at six months postoperatively, based on comparisons of the isokinetic strength curves measured throughout knee extension.

Study design

Cross-sectional study

Methods

One-hundred-and-forty-four patients were assigned into three groups according to the graft used for a primary ACL reconstruction: semitendinosus (n=47), semitendinosus+gracilis (n = 75) and patellar (n=22) tendon graft. Normalized hamstring eccentric and quadriceps concentric torques, and hamstrings-to-quadriceps torque ratio (defined as the dynamic functional ratio) were bilaterally assessed during knee extension. Statistical parametric mapping was used to compare the curves of torques and ratio from 90 ° to 30 °of knee flexion between groups.

Results

The uninvolved knees presented similar strength and ratio curves in the three groups. When compared involved to uninvolved knees, hamstring strength deficit was found in hamstring tendon groups throughout knee extension (p<0.001), and quadriceps strength deficit in the three groups throughout knee extension (p<0.001). Hamstrings-to-quadriceps torque ratio was unaltered when using hamstring tendon grafts, while increased ratio was observed up to knee mid-extension when using patellar tendon graft (p<0.001).

Conclusions

These findings suggest exercises with specific range of motion and contraction type in relation to graft may be considered for implementation into postoperative rehabilitation program in order to eliminate the regional strength deficits observed after ACL reconstruction.

Level of evidence

3

Keywords: Dynamic functional ratio, hamstring eccentric strength, Movement system, quadriceps concentric strength, statistical parametric mapping

INTRODUCTION

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction aims at restoring the function of the native ACL in terms of knee stability and flexion-extension mobility.1 The most popular grafts for ACL reconstruction are those using patellar tendon (PT) or hamstring tendon (HT).2 The HT procedure presents different graft possibilities, such as semitendinosus tendon (ST) alone or in combination with the gracilis tendon (STG).1 Each type of graft presents specific functional drawbacks;3 however, regardless the graft, restoring knee muscle strength to return to sport remains challenging.

Isokinetic dynamometry is considered the gold standard to provide objective assessment of muscle strength.4 The quantification of a muscular strength deficit is mainly reported through two peak torques:2 one when the quadriceps muscles act concentrically (Qconpeak) and one when the hamstrings act eccentrically (Heccpeak).5,6 These peak torque values are used to calculate limb symmetry index between the involved (i.e. leg having undergone the surgery) and uninvolved (i.e. contralateral leg) legs to reflect muscle strength deficit in the involved leg. Peak torques are also used to compute hamstrings-to-quadriceps strength ratio (Heccpeak/Qconpeak) to reflect knee agonist-antagonist muscle strength balance. In this context, trends for weakness in quadriceps when using PT graft and in hamstrings when using HT graft are reported.2 But the superiority of one surgical technique to the other one on the postoperative knee strength cannot be demonstrated.1 Although using peak values to assess muscle strength and deficits and balance after ACL reconstruction is a standard approach, reasoning using only peak values to reflect the knee muscle strength during the full knee extension remains questionable.

Alternatively, Heimstra et al.7 defined knee muscle strength maps, expressing the strength as a function of knee angle and motion velocity. Such an approach is based on isokinetic assessments at 10 different velocities, eccentric and concentric contractions, for a knee positioning between 5 and 95 ° of knee flexion. For one patient, the strength map is generated by 2500 torque values extracted from isokinetic recordings. Detailed information provided by strength map highlight a quadriceps strength deficit throughout the knee extension regardless the type of graft in comparison with controls, as well as regional strength deficits of the quadriceps and hamstrings in relation with the autograft donor site. Such an approach points out the importance for taking into account muscle strength throughout the knee range of motion, but remains complex to be carried out for clinical assessment routinely.

A more comprehensive method than peak torques and an easier method than strength mapping may be explored to study the knee muscle strength deficit regarding the graft used for ACL reconstruction in relation with the knee range of motion. This study, therefore, aimed at investigating the effects of graft used for ACL reconstruction on the knee muscle strength and balance, based on comparisons of the strength curves measured throughout the knee extension. It was hypothesized that, at six months postoperatively, a weakness in quadriceps would be observed whatever the graft used for ACL reconstruction, while a weakness in hamstrings would be reported only when using both hamstring tendon grafts. Such deficits may lead to knee muscle strength imbalance for all types of graft.

METHODS

Patients

Between January 2011 and January 2014, 144 patients participated in this study, which was approved by the Ethical Committee ‘Sud-Est II” (IRB 00009118). Inclusion criteria were practicing physical activity at the time of ACL rupture (soccer, rugby, skiing, basketball, running, etc), having undergone a unilateral primary surgical ACL reconstruction using PT, ST or STG graft, having a contralateral knee with no history of injury, having performed 40 rehabilitative sessions supervised by a physical therapist, and having performed the isokinetic assessments at six-month ( ± 20 days) postoperatively. Exclusion criteria were having undergone additional surgery, such as meniscus repair or lateral extra-articular reconstruction, or suffering from pain at the reconstructed knee, or graft harvested in the contralateral knee.

Procedures

The isokinetic dynamometer (Contrex MJ; Dubendorf, Switzerland; Sampling rate: 256 Hz) allowed instantaneous torque recording with gravity correction and filtering (CON-TREX human kinetics software). After a six-minute warm-up on stationary bicycle, the participant was sitting with 85 ° hip angle and with the knee joint rotation axis aligned on the dynamometer rotational axis. The participant was secured to the equipment with straps across their trunk and thighs, and instructed to push/pull as hard as possible against a pad attached to the distal tibia about 3 cm proximally to the lateral malleolus and to complete the full 0–118 ° range of motion (0 ° for knee fully extended). The participant was then instructed to complete two series of knee flexion/extension under vocal encouragement. Each series was composed of repetitions for training and repetitions for test (Table 1). The duration of the recovery was set at 30 seconds between training and test repetitions, and at one minute between test and training repetitions. The uninvolved knee was the first assessed in order to make the patient confident when the involved knee was evaluated.

Table 1.

Chronological description of the isokinetic procedure to assess one leg during knee flexion and extension.

| Series | Type | Repetitions | Quadriceps | Hamstrings | Velocity (°/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Training | 4 | Concentric | Concentric | 240 |

| 1 | Test | 20 | Concentric | Concentric | 240 |

| 2 | Training | 3 | Eccentric | Eccentric | 30 |

| 2 | Test | 4 | Eccentric | Eccentric | 30 |

For each knee, the repetitions of hamstring eccentric contraction at 30 °.s-1 (Hecc) and quadriceps concentric contraction at 240.s-1 (Qcon) with the maximal torques were kept for the analysis.6,8 Preliminary analysis revealed that the common range of knee joint angle values for constant velocity was between 90 °-30 ° of knee flexion. Outcomes were then Hecc and Qcon values at each angle between 90 °-30 ° knee flexion, and expressed in Nm.kg-1, i.e torque divided by body mass, and the dynamic functional ratio (Hecc/Qcon) by dividing Hecc by Qcon at each knee joint angle between 90 °-30 ° knee flexion.

Statistical analysis

All the data are presented by mean ± standard deviation. ANOVA for one factor (graft: PT vs. ST vs. STG) were performed on quantitative variables of demographic and surgical outcomes. In case of significant effect, Tukey's post hoc tests were made. Chi² tests were applied on qualitative variable of surgical outcome. For isokinetic outcomes, ANOVA SPM{F} for one factor (graft: PT vs. ST vs. STG) and two repeated measures (Laterality: involved vs. uninvolved knees) were applied on Hecc, Qcon and Hecc/Qcon.9 In case of significant effect, post hoc comparisons were made using independent and paired t SPM{F}tests, and Bonferroni correction. All statistical tests were performed using the open-source toolbox SPM-1D (© Todd Pataky, 2014, version M0.1) in Matlab 2016a. Significant difference was fixed at p≤0.05.

RESULTS

ANOVA revealed no significant differences between groups for descriptive characteristics (Table 2), while Chi² test reported a significant relationship between groups and surgeons (p<0.001). Surgeon 2 practiced more PT and less ST grafts than expected counts, while opposite distribution was observed for Surgeon 3.

Table 2.

Characteristics for the groups with semitendinosus+gracilis (STG), semitendinosus (ST) and patellar (PT) tendon grafts. Mean ± standard deviation [minimum and maximum in brackets] for quantitative variables and number for qualitative variable.

| STGa | STb | PTc | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 75 | 47 | 22 |

| Age (years) | 28.1 ± 9.8 [15,53] | 28.9 ± 10.0 [15,56] | 25.2 ± 6.2 [17,37] |

| Mass (kg) | 77.9 ± 11.8 [54,115] | 78.5 ± 10.0 [64,104] | 76.0 ± 9.6 [55,95] |

| Rupture-surgery delay (days) | 94.5 ± 76.3 [12,346] | 105.5 ± 726.7 [20,348] | 124.6 ± 83.7 [26,346] |

| Surgery-test delay (days) | 184 ± 9 [160,200] | 185 ± 9 [167,200] | 186 ± 9 [167,200] |

| Number of surgeries by surgeon (S1/S2/S3) | 37/15/23 | 21/24/2 | 13/6/3*** |

p<0.001 for significant effect of Chi² test

group with semitendinosus and gracilis tendon graft

group with semitendinosus tendon graft

group with patellar tendon graft

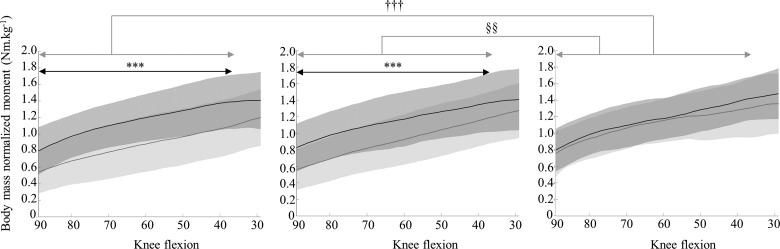

ANOVA SPM{F} revealed a significant effect of interaction group*laterality on Hecc during knee extension between 90 and 37 ° of knee flexion (p<0.05). Post hoc tests for group comparisons (Figure 1) showed that no significant difference was found between the uninvolved knee of the three groups, and, for the involved knees, PT group displayed higher Hecc than hamstring groups (p<0.001 for STG and p=0.005 for ST). For bilateral comparisons, the involved knee with hamstring grafts presented significant lower Hecc strength than the uninvolved knee (Hecc deficit between 12.9 and 31.2 % with p<0.001 for STG, and Hecc deficit between 6.2 and 27.7 % with p<0.001 for ST), while similar Hecc strength was found for both the knees in PT group.

Figure 1.

Mean ( ± standard deviation) hamstring eccentric normalized moments at 30 °.s-1 between 90 and 30 ° of knee flexion, with grey curve for involved knee, black curve for uninvolved knee, STG for semitendinosus+gracilis tendon graft, ST for semitendinosus tendon graft and PT, for patellar tendon graft.

*** indicates significant difference between involved and uninvolved knees at p<0.001, ††† indicates significant difference between STG and PT involved knees at p<0.001, and §§ indicates significant difference between ST and PT involved knees at p<0.01. Arrows indicate the knee range of motion in which significant differences were found.

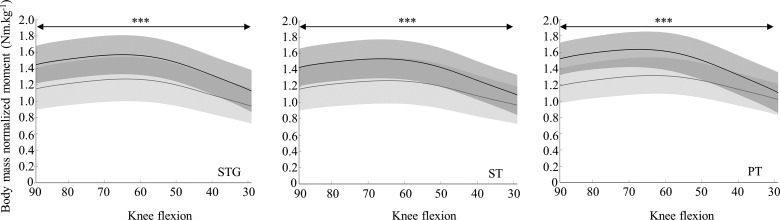

ANOVA SPM{F} revealed no significant effect of the interaction group*laterality and of the group on Qcon. Significant effect of laterality on Qcon during knee extension between 90 and 30 ° of knee flexion was found (p<0.001). For the three groups (Figure 2), Qcon was significantly lower in the involved knee than the uninvolved knee (mean deficit: 17.1 ± 2.7 %).

Figure 2.

Mean ( ± standard deviation) quadriceps concentric normalized moments at 240 °.s−1 between 90 and 30 ° of knee flexion., with grey curve for involved knee, black curve for uninvolved knee, STG for semitendinosus+gracilis tendon graft, ST for semitendinosus tendon graft and PT, for patellar tendon graft.

*** indicates significant difference between involved and uninvolved knees at p<0.001. Arrows indicate the knee range of motion in which significant differences were found.

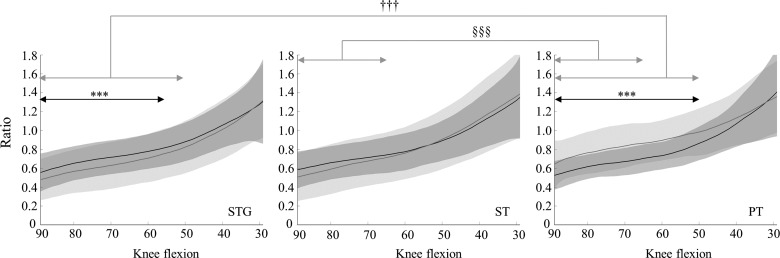

ANOVA SPM{F} revealed a significant effect of interaction group*laterality on Hecc/Qcon during knee extension between 90 and 51 ° of knee flexion (p<0.05). Post hoc tests for group comparisons (Figure 3) showed no significant differences between the uninvolved knee of the three groups. For the involved knees, STG and ST groups presented similar values (0.48 ± 0.22 and 0.51 ± 0.25 at 90 ° of knee flexion, respectively, and 1.32 ± 0.39 and 1.39 ± 0.46 at 30 ° of knee flexion, respectively). PT group presented significantly higher ratio than hamstring groups (+0.19 ± 0.01 between 90 and 50 ° of knee flexion when compared to STG with p=0.001 and +0.16 ± 0.01 between 90 and 65 ° of knee flexion when compared to ST with p=0.02. For bilateral comparisons, similar ratios for both knees were observed in ST. PT group had a significantly higher ratio in the involved knee than the uninvolved knee (+0.12 ± 0.05 between 88 and 50 ° of knee flexion, p<0.001), and STG group presented a significantly lower ratio in the involved knee than the uninvolved knee (-0.08 ± 0.01 between 90 and 57 ° of knee flexion, p<0.001).

Figure 3.

Mean ( ± standard deviation) ratio between 90 and 30 ° of knee flexion, with grey curves for involved knees, black curves for uninvolved knees. STG for semitendinosus+gracilis tendon graft, ST for semitendinosus tendon graft and PT for patellar tendon graft.

*** indicates significant difference between involved and uninvolved knees at p<0.001, ††† indicates significant difference between STG and PT involved knees at p<0.001, and §§§ indicates significant difference between ST and PT involved knees at p<0.001. Arrows indicate the knee range of motion in which significant differences were found.

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the effect of the graft used for ACL reconstruction on knee muscular strength and balance, by examining the strength curves measured throughout knee extension. The main findings indicate a hamstring eccentric strength deficit for hamstring tendon grafts and a quadriceps concentric strength deficit independent of graft type throughout knee extension at six months postoperatively. Dynamic functional ratio was unaltered when using hamstring tendon grafts, while an increase in this ratio was observed up to knee mid-extension when using patellar tendon graft.

Restoring muscle strength of the quadriceps and hamstrings is a key factor for rehabilitation after ACL reconstruction,4 particularly regaining similar muscle strength in the reconstructed knee than in the contralateral one.10 Using contralateral knee as reference requires that the level of strength for this knee corresponds to levels observed in healthy knees. In this study, the muscle strength at the contralateral knee was similar for the three groups (1.58 ± 0.24 N.kg-1 for peak quadriceps strength at 240 °.s-1 and 2.00 ± 0.24 N.kg-1 for peak hamstring strength at 30 °.s-1), but appeared slightly different than strength for control physically active participants reported in the literature (about 2.2 N.kg-1 for quadriceps at 240 °.s-1 and about 1.7 N.kg-1 for hamstrings at 30 °.s-1).7 When knowing that the contralateral knee also experienced strength impairment during the postoperative period after ACL reconstruction,11,12 the authors considered that these differences remained minimal and allowed us to use the contralateral knee as reference for the involved knee.13 Moreover, given that the three groups had similar demographic and surgical characteristics as well as similar uninvolved knee muscular strength and balance, the authors assumed that differences in strength observed at the involved knee may be in relation with the graft used for ACL reconstruction.

When focusing on limb symmetry strength between the involved and uninvolved knees, the current results confirmed partly that the strength deficit is in relation with the donor site morbidity.3,14 Indeed, hamstring eccentric strength deficit was associated to hamstring tendon grafts, while, quadriceps concentric strength deficit was related to patellar tendon graft (on average 16.7 ± 4.6%). Although the magnitude of these deficits was in line with those reported in the literature, the comparisons remains difficult because of differences in experimental set up (isokinetic device, velocity, knee range of motion). Nevertheless, the current study indicated that the deficits in strength existed throughout knee extension and not only for maximal strengths. Such limb asymmetry may be explained by the period of detraining associated with ACL rupture, which may induce muscle atrophy,15 alterations in muscle architecture,16 and the inability of the recovered tendon to transmit muscle force across the joint.17 However, the donor site morbidity cannot be the only cause of strength deficits because the quadriceps strength was also altered when the ACL was reconstructed using hamstring tendon grafts. Indeed, hamstring tendon grafts were associated to a similar deficit in quadriceps concentric strength than patellar tendon graft (18.3 ± 1.5% for STG, and 16.0 ± 2.9% for ST). Such a low strength capability of the quadriceps after hamstring tendon grafts may have multifactorial causes, such as rehabilitation deficit or compensatory mechanisms to protect the reconstructed knee joint.18 Consequently, due to deficits in both hamstring and quadriceps strengths, hamstring tendon grafts may present with more functional drawbacks in terms of knee muscle strength levels than patellar tendon graft for ACL reconstruction.

The functional ratio, computed by dividing the peak value of hamstring eccentric strength by the peak value of quadriceps concentric strength, is believed to be an important factor for reflecting the dynamic stabilization of the knee joint.19 No consensus currently exists on the targeted value for this functional ratio. A ratio between 0.5 and 0.8 is reported as normal by Undheim et al.4 Ageberg et al.19 recommend a high value of this ratio after ACL reconstruction to protect the knee against re-injury, with no specific value offered. Coombs & Garbutt20 and Fousekis et al.21 suggest a value near 1.0 because this value would reflect the eccentric capacity of the hamstrings to counterbalance the concentric capacity of the quadriceps to stop the knee extension. However, when knee extends, agonist muscles, i.e. quadriceps, generate high strength at the beginning of the motion, while antagonist muscles, i.e. hamstrings, generate high strength at the end of the motion. The peak strength values involved in the ratio calculation then occur at different knee joint angles.5 Modelling the hamstrings-to-quadriceps strength ratio throughout knee extension may better reflect the knee strength balance during the achievement of functional motion. For our uninvolved knees, the mean functional ratio at 90 ° of knee flexion was 0.56 ± 0.19 and increased continuously during knee extension until 1.34 ± 0.45 at 30 ° of knee flexion, suggesting that only one value cannot be representative of knee muscular strength balance involved throughout knee extension. At six months postoperatively, patients with hamstring grafts for ACL reconstruction presented similar values and closed to those observed in uninvolved knees, while patients with patellar tendon graft presented higher values up to 50 ° of knee flexion. Despite the functional consequence of this localized knee muscle imbalance is unknown, the deficit in quadriceps strength related to patellar tendon graft, discussed above, may modify the force distribution at the knee joint during motion and then jeopardize the knee joint integrity. Too high values of dynamic functional ratio up to knee mid-extension may potentially be clinical outcomes to prevent postoperative complications, which predominate after ACL reconstruction with patellar than hamstring tendon grafts.22 Consequently, due to increased ratio up to knee mid-extension, patellar tendon grafts may present more functional drawbacks in terms of knee muscle strength balance than hamstring tendon graft for ACL reconstruction.

This study presents some limitations that warrant discussion. The first limitation concerned the retrospective nature of this work, which challenges the control for potential confounding factors. The uneven group size may generate statistical issues; the wide range of ages in the groups may limit the generalization of these findings to younger population; and the comparison of the current findings with those from prospective comparative and randomized studies demands caution. Another limitation was the lack of detailed information on the rehabilitation program performed by the patients with reconstructed-ACL knees. The nature of the rehabilitative exercises and their progressive implementation may influence the restoration of knee muscle strength and balance. As the uninvolved knees in the three groups presented similar knee muscle strength and balance, it was assumed that differences observed for involved knees were related to the type of graft used for ACL reconstruction. This study was however the first to base the comparisons between grafts on knee strength and balance continuously recorded during knee extension, which was an innovative method. The findings highlighted regional strength deficits in relation with the autograft donor site. Further studied needed to link the knee muscle strength abilities at six months postoperatively with the rate of return to sport, and to explore the effects of additional repairs on isokinetic results.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings of this study reveal that, at six months postoperatively, hamstring tendon graft was associated with both hamstring and quadriceps strength deficits throughout leg extension, while the patellar tendon graft was associated with quadriceps strength deficit only. Similar weakness in agonist and antagonist knee muscles after hamstring tendon grafts resulted in unaltered knee muscular strength balance throughout knee extension, whereas strength deficit in quadriceps muscle with no alteration in hamstring strength generated knee muscular strength imbalance up to knee mid-extension in subjects with patellar tendon grafts. Analyzing knee muscle strength throughout leg extension provides information on regional strength deficit in relation with the graft used for ACL reconstruction, which may help to adapt rehabilitation and return to sport programs to the type of graft used for ACL reconstruction, and then improve restoration of knee muscle strength to reduce the potential risk for knee re-injury.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dauty M Tortellier L Rochcongar P. Isokinetic and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring or patellar tendon graft: Analysis of literature. Int J Sports Med. 2005;26:599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xergia S McClelland J Kvist J, et al. The influence of graft choice on isokinetic muscle strength 4-24 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19:768-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jamil T Ansari U Najabat A, et al. A review on biomechanical and treatment aspects associated with anterior cruciate ligament. Inn Res Biomed Eng. 2017;38:13-25. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Undheim MB Cosgrave C King E, et al. Isokinetic muscle strength and readiness to return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: is there an association? A systematic review and a protocol recommendation. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:1305–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dauty M Menu P Finasson-Chailloux A. Cutoffs of isokinetics strength ratio and hamstring strain prediction in professional soccer players. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2018;28:276–281; 10.1111/sms.12890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croisier JL Forthomme B Namurois MH, et al. Hamstring muscle strain recurrence and strength performance disorders. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiemstra LA Webber S Macdonald PB, et al. Knee strength deficits after hamstring tendon and patellar tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Med Sci Sports Exer. 2000;32:1472–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masson E Delmeule T Petit H, et al. A set protocol to determine reference thresholds for isokinetic knee ratios: Application in the Bordeaux Girondins Football Club. J Traumatol Sport. 2016;33:134–144. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pataky TC. Generalized n-dimensional biomechanical field analysis using statistical parametric mapping. J Biomech. 2010;42:1976-1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myer GD Paterno MV Ford KR., et al. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: criteria-based progression through the return-to-sport phase. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:385–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mirkov DM Knezevic OM Maffiuletti NA, et al. Contralateral limb deficit after ACL-reconstructio: an analysis of early and late phase of rate of force development. J Sports Sci. 2017;35:435-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pairot de Fontenay B Argaud S Blache Y, et al. Contralateral limb deficit seven months after ACL-reconstruction: an analysis of single-leg hop tests. Knee. 2015;22:309-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petschnig R Baron R Albrecht M. The relationship between isokinetic quadriceps strength test and hop tests for distance and one-legged vertical jump test following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28:23-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dagnoni ID Bilibiu J Stiehler S, et al. Flexor-extensor relationship knee after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Fisioter Mov. 2014;27:201-209. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiemstra LA Webber S MacDonald PB, et al. Hamstring and quadriceps strength balance in normal and hamstring anterior cruciate ligament-reconstructed subjects. Clin J Sport Med. 2004;14:274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Timmins RG Bourne MN Shield AJ, et al. Biceps femoris architecture and strength in athletes with a previous anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48:337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suydam SM Cortes DH Axe MJ., et al. Semitendinosus tendon for ACL reconstruction. Regrowth and mechanical property recovery. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5:2325967117712944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudroff T. Functional capability is enhanced with semitendinosus than patellar tendon ACL repair. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1486–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ageberg E Roos HP Silbernagel KG, et al. Knee extension and flexion muscle power after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon graft or hamstring tendons graft: a cross-sectional comparison 3 years post surgery. Knee Sur Sports Traumat Arthrosc. 2009;17:162-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coombs R Garbutt G. Developments in the use of the hamstring/quadriceps ratio for the assessment of muscle balance. J Sports Sci Med. 2002;1:56-62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fousekis K Tsepis E Poulmedis P, et al. Intrinsic risk factors of non-contact quadriceps and hamstring strains in soccer: a prospective study of 100 professional players. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:709–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuette HB Kraeutler MJ Houck DA, et al. Bone–patellar tendon–bone versus hamstring tendon autografts for primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5:2325967117736484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]