3,5-triazines label and inhibit ascorbate peroxidases (APXs) in plants, revealing that triazine herbicides and their degradation products block APXs and reduce photosynthesis.

Abstract

Though they are rare in nature, anthropogenic 1,3,5-triazines have been used in herbicides as chemically stable scaffolds. Here, we show that small 1,3,5-triazines selectively target ascorbate peroxidases (APXs) in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), rice (Oryza sativa), maize (Zea mays), liverwort (Marchantia polymorpha), and other plant species. The alkyne-tagged 2-chloro-4-methyl-1,3,5-triazine probe KSC-3 selectively binds APX enzymes, both in crude extracts and in living cells. KSC-3 blocks APX activity, thereby reducing photosynthetic activity under moderate light stress, even in apx1 mutant plants. This suggests that APX enzymes in addition to APX1 protect the photosystem against reactive oxygen species. Profiling APX1 with KCS-3 revealed that the catabolic products of atrazine (a 1,3,5-triazine herbicide), which are common soil pollutants, also target APX1. Thus, KSC-3 is a powerful chemical probe to study APX enzymes in the plant kingdom.

Molecules based on a 1,3,5-triazine scaffold are rare in nature. Most 1,3,5-triazine compounds are anthropogenic and have only existed in the last 150 years (Seffernick and Wackett, 2016). Because it is easy to synthesize from simple precursors, 1,3,5-triazine is a modular scaffold that is often used in industrial applications, including the synthesis of medicines, resins, agrochemicals, and reactive dyes. The highly stable nature of triazine compounds leads to their persistence in the environment and exposure to organisms including algae and plants. Some plants can degrade these compounds into metabolic intermediates (LeBaron, 2011; Seffernick and Wackett, 2016), many of which accumulate in soil and streams in agricultural areas (Krutz et al., 2003). Although bioactivities have been reported for 1,3,5-triazines in plants, little is known about the direct targets of these compounds in plants, except for atrazine—an herbicide that binds to the quinone binding site in the D1 protein of PSII to inhibit photosynthesis (Gardner, 1981; Lancaster and Michel, 1999; Broser et al., 2011).

Target identification can be achieved with chemical proteomics. This approach relies on chemical probes based on reactive molecules functionalized with a reporter tag. The tag can be an affinity tag (e.g. biotin), a fluorescent tag (e.g. BODIPY [Thermo Fisher Scientific] or rhodamine), or a chemical reactive tag (e.g. azide or alkyne minitag). These minitags can be coupled to an affinity or fluorescent tag using “click chemistry,” a copper-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition reaction. The small alkyne tag minimizes the alteration to the structure of the small molecule and reduces the chances that the functionalization will perturb the interaction with the target protein, while maintaining physicochemical properties such as cell membrane permeability (Morimoto and van der Hoorn, 2016; Wright and Sieber, 2016). The (photo)reactive group in chemical probes mediates a covalent interaction with target proteins, facilitating the detection and identification of the target proteins by affinity purification coupled with mass spectrometry (MS) analysis.

Chemical proteomic technologies were developed in pharmaceutical research and are increasingly used in life sciences, including plant research. Previously, a library of Cys-reactive 1,3,5-triazine-based chemical probes were designed and tested on mammalian proteomes, identifying a covalent inhibitor for human protein disulfide isomerase, a new therapeutic target for cancer treatment (Banerjee et al., 2013; Cole et al., 2018). Here, we screened a small library of 32 alkyne-functionalized 1,3,5-triazine probes and discovered that one of these probes, KSC-3, selectively labels ASCORBATE PEROXIDASE1 (APX1), a plant-specific, cytosolic, heme-containing enzyme that sequesters hydrogen peroxide through ascorbate oxidation. We show that KSC-3 labeling inhibits APX1 activity, thereby enhancing the toxicity of hydrogen peroxide generated by light stress. Furthermore, APX1 labeling by KSC-3 is broadly applicable in plants, displaying robust signals in angiosperms, gymnosperms, and bryophytes, consistent with the conserved role of APX1 in the plant kingdom. Interestingly, atrazine degradation products inhibit the labeling of APX1 by KSC-3, revealing targets of naturally occurring herbicide degradation products in plants.

RESULTS

Screen of 1,3,5-Triazine Probes for Selective Labeling Identifies KSC-3

To examine the chemical reactivity and selectivity of 1,3,5-triazine-based probes in plants, we tested 32 1,3,5-triazine probes for labeling in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) cell culture extracts (Fig. 1A; Banerjee et al., 2013; Cole et al., 2018). All tested probes possess three features: (1) an alkyne minitag for coupling with a biotin or a fluorophore using click chemistry; (2) a chloroacetamide or chlorotriazine-reactive group that may covalently react with target proteins; and (3) a diversity element to add specificity to the probe. Chloroacetamide-rhodamine (CA-Rh) and DMSO solvent (no-probe control [NPC]) were included as a positive and a negative control for labeling, respectively.

Figure 1.

Screen for selective labeling identifies KSC-3. A, Chemical structures of the triazine scaffold library used in this study. Most compounds carry an alkyne minitag (right) and a chloroacetamide-reactive group (gray), but harbor different substituents (R, red). RB-11-cb contains a chloronitrobenzene electrophile, and KSC-3 contains a chlorotriazine electrophile. B, Screen of 32 1,3,5-triazines for labeling. Arabidopsis cell-culture extracts were labeled with 5-μM triazine probes. Alkyne-labeled proteins were coupled with Cy3-azide using click chemistry, and proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE gels. Fluorescent proteins were detected by in-gel fluorescence scanning at 488-nm excitation and 520-nm emission. Coomassie staining is provided as a loading control. CA-Rh was used as positive control. Specific signals are indicated. This experiment was performed twice with similar results.

Several probes produce specific signals when tested on extracts of Arabidopsis cell cultures. These signals are either at 55 kD (e.g. RB-11-ca, RB-2-ca, EAPCIARB, MetCIARB, KSC-4, and KSC-7) or at 28 kD (KSC-3 and EAPCIARB; Fig. 1B). Of these tested probes, KSC-3 produces the strongest signal so we continued working with this probe. Notably, KSC-3 is unique in the screened compound collection because it contains a chlorotriazine electrophile instead of a chloroacetamide group.

We next assessed the selectivity of KSC-3 labeling by increased KSC-3 concentrations or prolonged labeling times. These experiments showed that signal intensity increases with higher KSC-3 concentration without significant labeling of other proteins (Supplemental Fig. S1A). KSC-3 labeling occurs within minutes and reaches the maximum within 15 min (Supplemental Fig. S1B). We conclude that KSC-3 labeling is selective and robust and we selected labeling conditions of 50-μM KSC-3 for 1 h for all further experiments.

APX1 Is the Main Target of KSC-3 in Arabidopsis

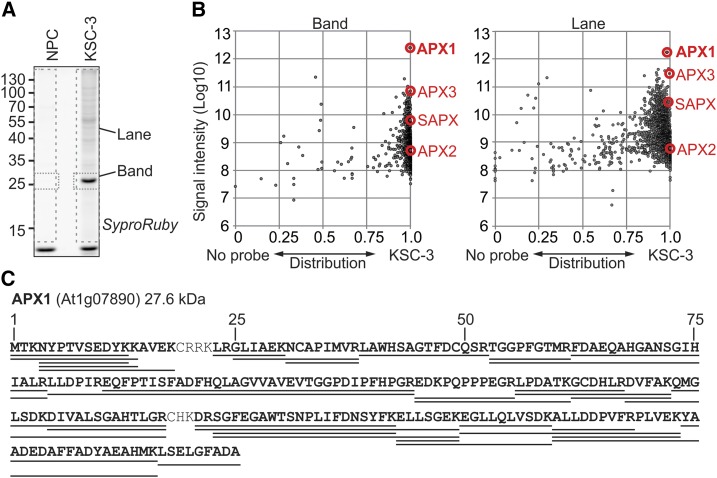

To identify the KSC-3 target, KSC-3-labeled proteins were coupled with biotin-azide using click-chemistry. Biotinylated proteins were enriched on streptavidin beads in triplicate, separated on protein gels, and stained with SYPRO-Ruby (Invitrogen). A distinct 28-kD protein band was observed in KSC-3–labeled samples but not in the NPC (Fig. 2A). We also observed additional weak signals in KSC-3–labeled samples at >40 kD. Therefore, we excised both the 28-kD region and whole lanes in triplicate and in-gel–digested the proteins with Lys-C and trypsin. Released peptides were identified by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). We detected 923 Arabidopsis proteins in at least three of the six band samples and 1,626 proteins in at least three of the six lane samples. Their total intensity was plotted against their distribution between the NPC- and the KSC-3-labeled samples. In both experiments, cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase 1 (APX1, At1g07890) was the main enriched protein with the highest intensity (Fig. 2B). Peptide coverage reached 96.8% for APX1 in the 28-kD band (Fig. 2C). We also identified APX2, APX3, and SAPX in KSC-3-labeled samples with much lower intensities (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

MS analysis identifies APX1 as the main target of KSC-3. A, Arabidopsis cell culture extracts were labeled with or without 50-µM KSC-3 in triplicate. Alkyne-labeled proteins were biotinylated using click chemistry with biotin-azide and biotinylated proteins were purified and separated on protein gel and stained with SYPRO Ruby. Both the 28-kD band and the whole lane were excised from different lanes. Gel slices were treated with Lys-C and trypsin, and released peptides were analyzed by LC-MS/MS. B, Arabidopsis proteins that were detected in more than three of the six samples were selected. Distribution of the MS signal intensities of the identified proteins over the NPC- (left) and the KSC-3–labeled sample (right), plotted against the total MS signal intensity for the band and the lane sample. Distribution = (KSC-3/[KSC-3+NPC]). C, Peptide coverage of APX1. The identified peptides from the band samples cover 96% of the APX1 protein sequence (underlined).

We took two approaches to validate whether KSC-3 labels APX1. First, we expressed N-terminally His-tagged APX1 (His-APX1) heterogeneously in Escherichia coli. His-APX1 proteins were purified and tested for KSC-3 labeling. His-APX1 was clearly labeled with KSC-3, confirming that APX1 is a target of KSC-3 (Fig. 3A). Second, we tested if the 28-kD signal is caused by APX1, by selecting two independent apx1 knock-out (KO) mutants of Arabidopsis (Fig. 3B). In both apx1 mutants, the 28-kD signal is absent (Fig. 3B), confirming that APX1 is a main target of KSC-3 in Arabidopsis.

Figure 3.

APX1 is the main target of KSC-3. A, KSC-3 labels recombinant AtAPX1 purified from E. coli. His-tagged Arabidopsis APX1 was expressed in E. coli and purified on Ni-NTA agarose. Purified APX1 was reconstituted with hemin and ascorbic acid and labeled with 50-μM KSC-3. This experiment was performed twice with similar results. B, Labeling is absent in two independent apx1 mutants. T-DNA insertion in apx1.2a (SALK_000249C) and apx1.2b (SALK_088596) are located in the sixth or ninth exons, respectively. The diagram shows the exons (boxes) and the open reading frame (black) and the positions of the two T-DNAs. Leaf extracts of wild-type (WT) plants (ecotype Col-0) and two apx1.2 mutants were labeled with and without 50-μM KSC-3 and analyzed as described in Figure 1. This is a representative of four repetition experiments.

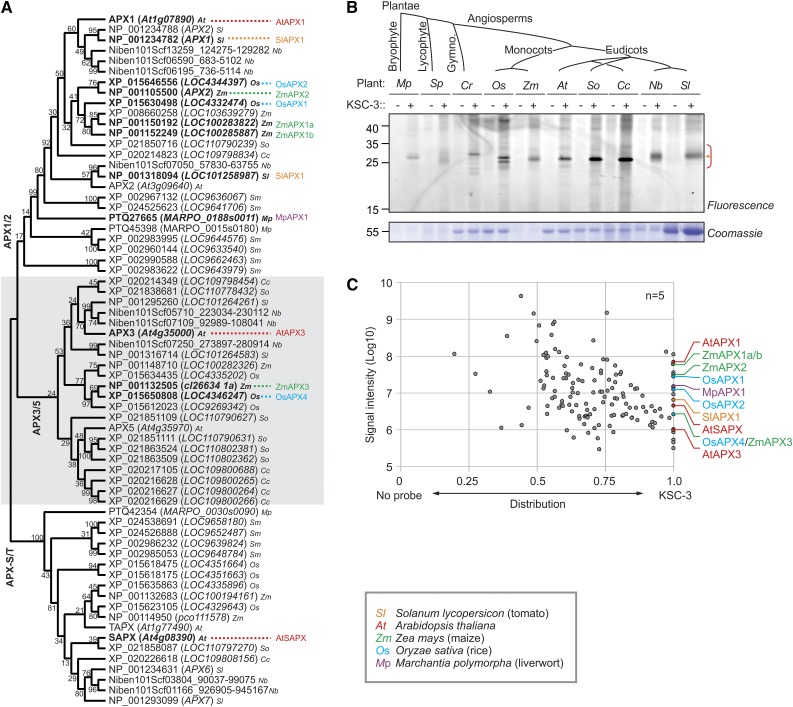

KSC-3 Labels APXs in the Other Plants

APX1 is highly conserved among the plant species (Maruta et al., 2016). Phylogenetic analysis of APX enzymes labeled by KSC-3 shows that identified APX enzymes occur in three conserved clades in the plant kingdom: APX-1/2, APX-3/5, and APX-S/T (Fig. 4A). We therefore tested if KSC-3 also targets APX proteins in plant species other than Arabidopsis. In addition to Arabidopsis, we included a model liverwort (Marchantia polymorpha), a model fern (Selaginella pulcherrima), a gymnosperm (sago palm [Cycas revoluta]), two monocots (rice [Oryza sativa] and maize [Zea mays]), and four dicots (spinach [Spinacia oleracea], pea [Cajanus cajan], tobacco [Nicotiana benthamiana], and tomato [Solanum lycopersicum]). KSC-3 labeling of leaf extracts of all 10 of these plant species results in ∼28-kD signals, consistent with the predicted molecular weight of APX1 (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

KSC-3 labels APXs in other plant species. A, Phylogenetic tree of the peroxidase domain of APX1/2/3/5/S/T homologs using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the model of Le and Gascuel (2008). The bootstrap consensus tree based on 1,000 bootstrap samplings is shown, with values next to branches corresponding to the percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together. B, Leaf extracts from various plants species were labeled with and without 50-µM KSC-3 as described in Figure 1. Similar results were obtained in an independent repetition experiment. C, Mixed proteome labeling reveals KSC-3 targets in five different plant species. Leaf extracts from five plants (Mp, Zm, Os, At, and Sl) were mixed at the same ratios and then labeled with or without 50-μM KSC-3. Alkyne-labeled proteins were biotinylated with biotin-azide using click chemistry. Biotinylated proteins were purified on streptavidin-agarose beads. On-bead digests with Lys-C and trypsin were analyzed by MS, and proteins that were detected in at least three of the five pull-down experiments were selected. Distribution of the MS signal intensities of the identified proteins over the NPC- and the KSC-3–labeled sample was plotted against the total MS signal intensity. Distribution = (KSC-3/[KSC-3+NPC]).

To confirm that KSC-3 labels putative APX1 orthologs in these plant species, we selected five plants having a well-annotated proteome database: M. polymorpha (Mp), O. sativa (Os), Z. mays (Zm), Arabidopsis (At), and S. lycopersicum (Sl). We performed MS analysis of purified KSC-3-labeled proteins to identify the signals. Instead of identifying the targets in five plant proteomes individually, we labeled a mixture of leaf extracts of five plant species and analyzed the MS data against the combined proteome database. In this way, we detected putative APX orthologs from all five species including AtAPX1, AtAPX3, and AtSAPX from Arabidopsis; SlAPX1 from tomato; OsAPX1–4 from rice; ZmAPX1a, ZmAPX1b, ZmAPX2, and ZmAPX3 from maize; and MpAPX1 from liverwort (Fig. 4C). These proteins include all the functional APX1 orthologs from the tested species (Fig. 4B). Taken together, these results show that KSC-3 targets APXs throughout the plant kingdom.

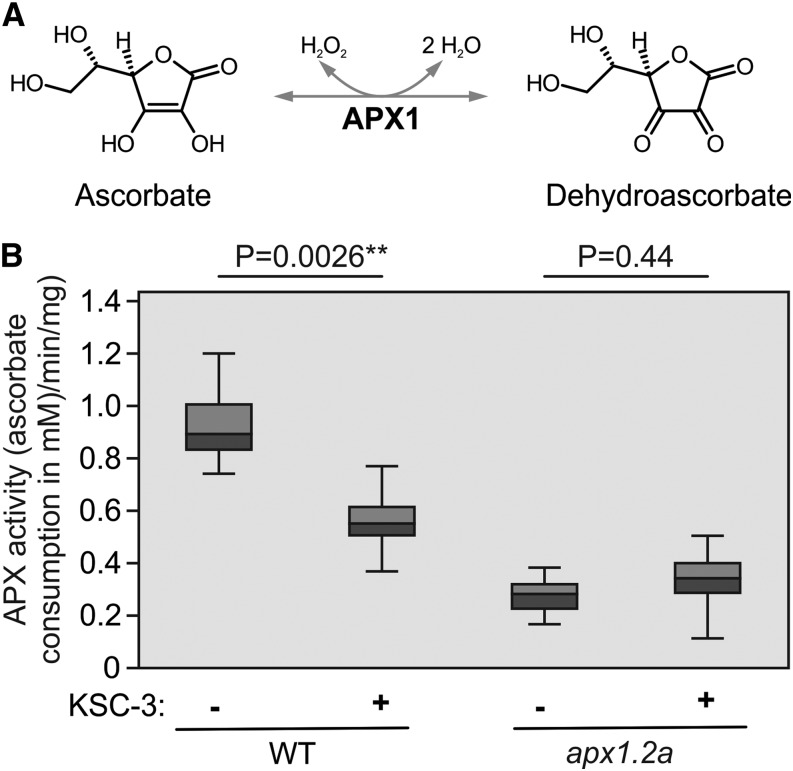

KSC-3 Inhibits Enzymatic Activity of APX1

Given its selective reactivity toward APX1, we anticipated that KSC-3 also inhibits APX1. APX1 is the major cytosolic reactive oxygen species (ROS)-scavenging enzyme that removes hydrogen peroxide using ascorbate (Fig. 5A). APX1 activity can be detected in leaf extracts as a difference in the decline in ascorbate levels between extracts of wild-type and apx1 mutant plants (Pnueli et al., 2003). Importantly, when added to leaf extracts of wild-type plants, KSC-3 causes a similar reduced decline in ascorbate levels when compared to leaf extracts from apx1 mutants (Fig. 5B), demonstrating that KSC-3 inhibits APX1.

Figure 5.

KSC-3 inhibits APX1 enzymatic activity in leaf extracts. A, Schematic illustration of the APX1-catalyzed oxidation of ascorbate into dehydroascorbate using hydrogen peroxide as substrate. B, KSC-3 suppresses total APX activity in Arabidopsis leaf extracts of wild-type (WT) plants but not in the apx1.2a mutant. Arabidopsis leaf extracts were incubated with and without 50-µM KSC-3 for 1 h and APX activity was measured by the decrease in A290, by monitoring the oxidation rate of ascorbate photometrically. APX activity is expressed in mmol ascorbate oxidized per minute per milligram total protein. Boxplots show the median with the lower and upper quartile, with the bars representing 1.5 interquartile range of n = 6 experiments. **, P < 0.01, Student’s t test. Similar results were generated in a repetition experiment.

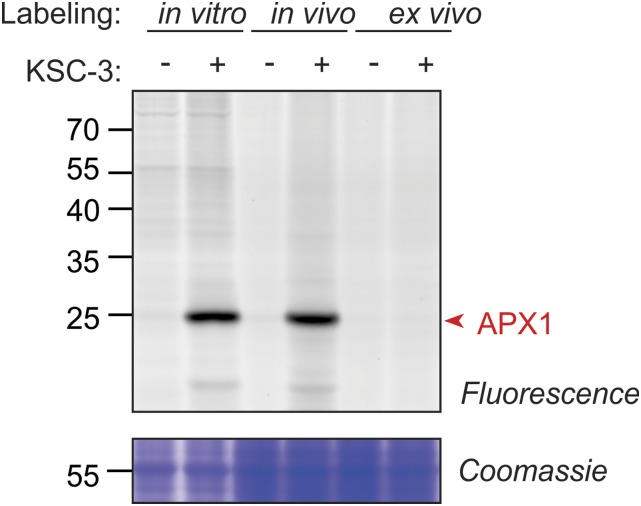

KSC-3 Also Targets APX1 In Vivo

All the preceding experiments were performed on cell culture and leaf extracts. To also test if KSC-3 can label inside living cells, we tested KSC-3 labeling of Arabidopsis cell cultures in vivo. In vivo KSC-3 labeling of a cell culture results in similar signals when compared to in vitro of a cell culture extract (Fig. 6). Because SDS prevents KSC-3 labeling ex vivo (Fig. 6), and we extract in SDS after in vivo labeling, the observed signal must come from KSC-3 labeling in vivo. This result shows that KSC-3 is membrane-permeable and can be used for in vivo labeling experiments.

Figure 6.

KSC-3 targets APX1 in living plant cells. In vivo labeling is achieved by labeling cell cultures, followed by extraction in denaturing buffer (containing SDS; middle pair of lanes). In vitro labeling is achieved by extracting the proteome with the native buffer, and labeling with the probe (left pair of lanes). Ex vivo labeling is achieved by extracting the proteome in denaturing buffer (containing SDS) and labeling with the probe (right pair of lanes). After labeling, proteins are precipitated with acetone and resuspended in denaturing buffer containing SDS and labeled proteins are coupled with Cy3-azide using click chemistry. Proteins are separated on SDS-PAGE gels and fluorescent proteins are detected by in-gel fluorescence scanning. Similar results were obtained in a repetition experiment.

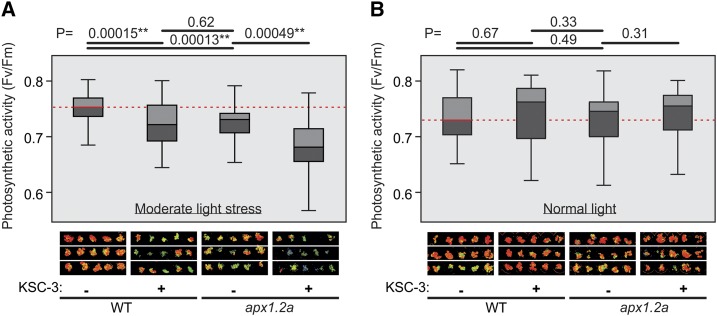

KSC-3 Treatment Phenocopies apx1 under Light Stress

The apx1 mutants have no obvious phenotype when grown under normal conditions. Under moderate light stress conditions, however, apx1 has a reduced photosynthetic activity associated with reduced protection of the chloroplast against ROS (Davletova et al., 2005). To test if KSC-3 reduces photosynthetic activity, we exposed control and KSC-3-treated wild-type and apx1 seedlings to normal light and moderate light stress. Under moderate light stress, KSC-3 treatment suppresses the photosynthetic activities to a similar level as the apx1 mutant without KSC-3 (Fig. 7A). Without light stress, KSC-3 treatment does not affect the photosynthetic activity similar to the apx1 mutants (Fig. 7B). The data shows that KSC-3 mimics the phenotype of apx1 mutants under light stress. However, KSC-3 also suppresses the photosynthetic activity in apx1 mutant seedlings under moderate light stress (Fig. 7A), indicating that other APXs targeted by KSC-3 provide additional protection of photosynthesis under moderate light stress.

Figure 7.

KSC-3 treatment mimics the apx1 mutant phenotype under light stress. A and B, Arabidopsis seedlings were grown on Murashige and Skoog agarose plates with and without 40 mg/L (219 μM) KSC-3 at (A) moderate light stress (250 μmol m−2 s−1) or (B) normal light (100 μmol m−2 s−1), respectively. Photosynthetic activity was measured in wild-type (WT) and apx1 mutant plants after 1 week using chlorophyll fluorescence imaging. Photosynthetic activity is expressed as the ratio of the rate of the photochemical activity and the total rate of absorbed energy dissipation (Fv/Fm). Shown is a representative of four independent experiments. The images below show a representative of chlorophyll fluorescence of 15 wells with seedlings. Boxplots show the median with the lower and upper quartile with the bars representing 1.5 interquartile range for n = 50 (A) or n = 36 (B) biological repeats. **, P < 0.01, Student’s t test. Similar results were obtained in repetition experiments.

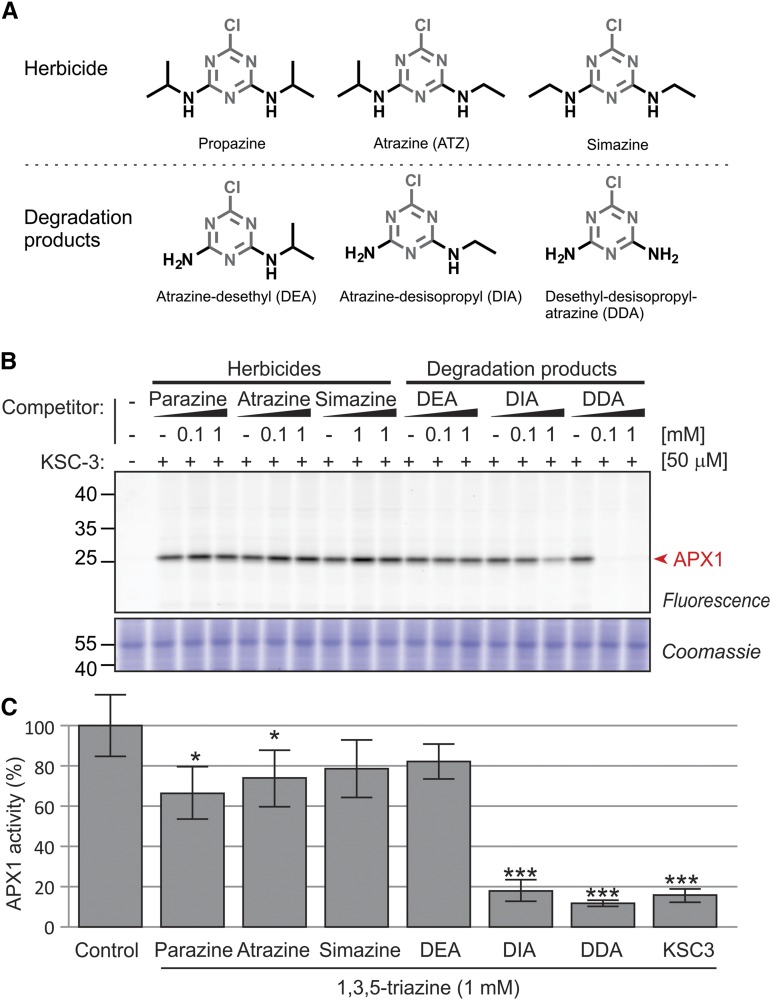

Herbicide Degradation Products Block APX1

Among 1,3,5-triazines used in research and agriculture, atrazine is one of the most commonly used and well-studied. Atrazine is a herbicide that binds to the plastoquinone binding site in the D1 protein of PSII, thereby inhibiting photosynthesis. However, it was not known whether atrazine and similar 1,3,5-triazine herbicides like parazine or simazine have additional targets. In addition, little is known about the natural degradation products (e.g. atrazine-desethyl [DEA], atrazine-desisopropyl [DIA], and atrazine-desethyl-desisopropyl [DDA]), which are often reabsorbed from the soil by plants (Rong Tan et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2018). Because of its structural similarity with KSC-3 (Fig. 8A) we tested if atrazine, parazine, simazine, DEA, DIA, or DDA can interact with APX1. Preincubation with DIA and DDA significantly suppressed APX1 labeling by KSC-3, indicating that they block APX1 (Fig. 8B). By contrast, the herbicides and DEA did not suppress APX1 labeling by KSC-3, indicating that the ethyl or propyl decoration of the triazine prohibits APX1 interaction (Fig. 8B). These results indicate that APX1 is a previously unknown target of the herbicide degradation products DIA and DDA that accumulate in agriculture.

Figure 8.

Herbicide degradation products of 1,3,5-triazine inhibit APX1. A, Structures of 1,3,5-triazine herbicides and their degradation products used in this study. B, Competitive labeling using 1,3,5-triazine herbicides and their degradation products. Arabidopsis cell culture extracts were preincubated with or without 0.1- or 1-mm triazines for 10 min and then labeled with 50-μm KSC-3 for 1 h. Similar results were obtained in a repetition experiment. C, Inhibition of purified APX1 by herbicide degradation products. Purified His-APX1 (0.25 µg) was incubated with 1-mM triazines in 2-mm ascorbate and ascorbate absorbance was monitored at 290 nm for 15 s. Error bars = sd of n = 4 replicates. P values were calculated when compared to the no-triazine-control, set at 100% APX1 activity (*, P = 0.05–0.01; ***, P < 0.01). Similar data were obtained from repetition experiments.

To test if DIA and DDA indeed inhibit APX1, we monitored the activity of purified APX1 in the presence of 1-mm 1,3,5-triazines by monitoring the rate of ascorbate peroxidation at 290-nm absorbance. This experiment confirms that DIA and DDA inhibit APX1 activity (Fig. 8C, P < 0.002). Likewise, also KSC-3 inhibits APX1 (Fig. 8C, P < 0.002). Interestingly, we also see a significant reduction of APX1 activity with parazine and atrazine, but to a lesser extent than DIA, DDA, and KSC-3, whereas simazine and DEA do not significantly affect APX1 activity (Fig. 8C). These experiments demonstrate that purified APX1 is inhibited by DIA, DDA, and KSC-3 and indicate that also triazine herbicides are weak inhibitors of APX1.

DISCUSSION

We discovered that the small 1,3,5,-triazine KSC-3 penetrates living cells and selectively targets and inhibits APXs in plants. KSC-3 reduces photosynthetic activities under light stress, consistent with the role of APX in protecting photosynthesis under light stress. Further work revealed that APX is also a target of triazine herbicide degradation products that occur in atrazine-treated fields.

Selectivity of Labeling

The selectivity of KSC-3 toward APX is remarkable in two ways. First, APX1 is the main target of KSC-3. The high selectivity of KSC-3 for APX1 is maintained at high probe concentrations, at longer incubation times, during in vivo labeling and across leaf extracts of various plant species. Second, only small decorations on the triazine are permitted for the labeling of APX1. Experiments with herbicides and their degradation products revealed that groups larger than amino or methyl groups at position 4 will prohibit the interaction with APX1. Although our discovery is that 1,3,5-triazines inhibit APXs, our data are consistent with a series of previously described small molecule APX inhibitors, including 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acid, which carries only one aromatic nitrogen (Durner and Klessig, 1995).

The mechanism of APX1 labeling by KSC-3 is currently unresolved. Theoretically, the alkyne tag of KSC-3 could react with the catalytic iron bound to the heme in APX1 (Moody and Raven, 2018), but this would not lead to covalent labeling of the protein as the iron and heme groups are not covalently linked to the enzyme. Moreover, the atrazine degradation products DIA and DDA, which also interact with APX1, lack this alkyne. The reactivity is likely mediated by the chlorotriazine group on KSC-3. Labeling studies with the 2,4-dichloro-1,3,5-triazine probe RB7 revealed that this dichloro-triazine can label proteins at Lys and Cys residues in mammalian proteomes (Shannon et al., 2014). However, only very few Lys and Cys residues are conserved across the APX1-orthologs of the different plant species (Supplemental Fig. S2). Furthermore, we identified unmodified peptides covering almost the entire APX1 protein. These data suggest that APX1 labeling is not at a single amino acid residue, or the resulting KSC-3-protein adduct is unstable during the MS preparation and ionization. One possible mechanism is the entrapment 1,3,5-triazines in the active site as a mimic of ascorbate (Macdonald et al., 2006). The active site iron ion could increase the reactivity of the triazine, which then could provoke random crosslinking to amino acid residues surrounding the KSC-3 binding site. This “suicide substrate” mechanism is reminiscent of the covalent inhibitors of cytochrome P450 enzymes (Wright et al., 2009). Resolving the mechanism by which KSC-3 binds to APX1 remains a subject for future research.

Two Alternative Ways to Study APX1 and Its Homologs

Our study uncovered two alternative ways to study APX1 and its homologs. For the first way, we introduced a chemical KO strategy to study the physiological role of APX enzymes in living plants. Adaptation to genetic dysfunction is an important limitation of traditional genetic studies. The absence of strong phenotypes of APX double mutants despite the role of these enzymes in ROS protection and signaling has been puzzling for years and may be caused by adaptation to genetic dysfunction (Maruta et al., 2016). Indeed, transient depletion of thylakoid APX via estradiol-induced gene silencing revealed stress signaling phenotypes that were absent in the tapx null mutants (Maruta et al., 2012). Likewise, adaptation to genetic dysfunction may have complicated the phenotypic interpretation of the previously described tapx/apx1 double mutants (Miller et al., 2007). Our work now introduces a chemical KO instrument to study the role of APX enzymes. We used this to show a further decline in photosynthesis under light stress even in the apx1 mutants, indicating that APX enzymes collectively protect photosynthesis during light stress. This chemical KO strategy will be useful to study the role of APX enzymes in living plants of different species.

The second alternative way to study APX1 is through competitive labeling with KSC-3. This strategy was used to discover that atrazine degradation products DIA and DDA interact with APX1. These compounds are generated in planta (Rong Tan et al., 2015) and by the soil microbiome (Kaufman and Blake, 1970; Behki et al., 1993) and are common in the soil of atrazine-treated agricultural fields (Krutz et al., 2003). Our discovery indicates that plants grown in atrazine-treated fields might underperform by reduced APX activity. Furthermore, our work predicts that DIA and DDA, when produced in planta, may enhance the toxicity of atrazine because atrazine itself promotes the release of ROS by inhibiting PSII (Gardner, 1981). Taken together, the ability to label APX1 using KSC-3 proved to be a useful strategy to understand the action of agrichemicals.

In conclusion, our study introduces an alternative chemical tool for studying APXs in the plant kingdom and demonstrates that chemical proteomics approach is powerful approach to identify inhibitors of enzymes and potential agrochemical targets. Taken further, the exploration of proteomes for a similar selective reactivity to chemicals can be used to discover new tools to monitor and control other enzymes. Even further, use of reactive chemicals to discover differential properties of proteins in a biological context can open many novel avenues in plant biology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemical Probe Synthesis

The synthesis of 1,3,5-triazine probes (Banerjee et al., 2013), KSC-4 to KSC-14 (Cole et al., 2018), and CA-Rh (Weerapana et al., 2008) have been described previously. KSC-3 was synthesized as follows: To a solution of cyanuric chloride (561.7 mg, 3.045 mmol) in dichloromethane (10 mL), methylmagnesium bromide (3 M, 4.06 mL) was added at −20°C and stirred for 4 h, then stirred 4 h at room temperature (RT). Crude residue was extracted via liquid–liquid extraction. Solvents were removed in vacuo and crude product was purified with flash chromatography to afford 2,4-dichloro-6-methyl-1,3,5-triazine as a yellow solid (234.8 mg, 47%) 1H NMR (500 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 2.70 (s, 3H). To a solution of 2,4-dichloro-6-methyl-1,3,5-triazine (122.8 mg, 0.7488 mmol) and diisopropylethylamine (145.2 mg, 1.1232 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (10 mL), propargylamine (61.9 µL, 1.1232 mmol) was added at RT and stirred overnight. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the crude product was purified with flash chromatography to afford the desired compound, KSC-3, as a white solid (136.7 mg, 61%). 1HNMR measurements in chloroform at 500 MHz: δ 5.65 (s, 1H), 4.28 (ddd, J = 11.0, 5.6, 2.5 Hz, 2H), 2.46 (s, 3H), 2.17 (s, 1H).

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Cell cultures of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) ecotype Landsberg erecta were maintained as described in Chandrasekar et al. (2014). Arabidopsis Heynh. ecotype Columbia was used as the wild-type line. The Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion lines apx1.2a (SALK_000249C) and apx1.2b (SALK_088596) were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre. Arabidopsis plants were grown on soil at 25°C under a day/night light regime with a 16-h photoperiod at a photon density of 100 ± 10 μmol photons m−2 s−1. Liverwort (Marchantia polymorpha) was grown as described in Honkanen et al. (2016). Fern (Selaginella pulcherrima), sago palm (Cycas revoluta), rice (Oryza sativa), maize (Zea mays), spinach (Spinacia oleracea), pea (Cajanus cajan), tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana), and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) were grown on soil under standard greenhouse conditions.

Protein Extraction

Cells of Arabidopsis cell cultures and leaves of various plant species were frozen with liquid nitrogen and ground with a mortar and pestle. Total proteins were extracted in the extraction buffer (1× phosphate-buffered saline [PBS; pH 7.4], 5 mm MgCl2, 10% [v/v] glycerol, 1% [w/v] polyvinylpolypyrrolidone [PVPP], and 0.3% [v/v] Triton X100), equivalent to three times the fresh weight of the plant tissues. The extracts were centrifuged at 15,000g for 20 min at 4°C and the supernatant containing the soluble proteins was retained. The protein concentration of the supernatant was measured using the DC Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad) and adjusted to 3 mg/mL with the extraction buffer. The resulting extracts were used for labeling. Mixed proteome were prepared by mixing 0.6-mg/mL total protein extracts from five plant species in extraction buffer (50-mm sodium P buffer [pH7.0], 2-mm l-ascorbic acid, 0.1-mm EDTA, and 2% [w/v] PVPP) at the same ratio, and used for labeling.

Labeling Plant Extracts

All probes were prepared as 0.5–5-mm stock solutions in DMSO. Equal volumes of dimethyl sulfoxide were used as an NPC. Labeling was performed as described in Chandrasekar et al. (2014). For fluorescence gel imaging, the extracts were incubated with 5–50-μm probes for 1 h at RT in the dark at a 50-μL total reaction volume. For the competition experiments, the extracts were preincubated with the corresponding chemicals at 0.1 or 1 mm for 10 min before labeling with the probe. The labeling reactions were quenched by acetone precipitation, as described in Hong and van der Hoorn (2014). The protein pellets were resuspended in 44 μL of PBS-SDS buffer (1×PBS [pH 7.4], and 1% [v/v] SDS), heated at 90°C for 10 min, and used for click-chemistry.

Heterologous APX1 Expression

The pET28a-APX1 expression vector (Yang et al., 2015) were transformed into Escherichia coli Rosetta (DE3) pLysS cells (Novagen). The bacterial cultures were grown in liquid Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C until optical density at 600 nm reached ∼0.5 and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mm. The cultures were incubated overnight at 22°C. Total proteins were extracted in the His-tag purification buffer (50-mm sodium P buffer [pH 8.0], 150-mm sodium chloride, 10-mm imidazole, 1-mm ascorbate [AsA], 10% [v/v] glycerol, and 1-mg/mL lysozyme) by incubation on ice for 1 h followed by sonication for 3 s ×3 times. The extracts were centrifuged at 15,000g for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatant containing the soluble proteins were used for the purification on Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions with minor modifications. The Ni-NTA agarose containing the recombinant proteins were washed with washing buffer (50-mm sodium P buffer [pH 8.0], 300-mm sodium chloride, 20-mm imidazole, 1-mm AsA, and 10% [v/v] glycerol). The recombinant proteins were eluted with elution buffer (50-mm sodium P buffer [pH 8.0], 300-mm sodium chloride, 250-mm imidazole, 1-mm AsA, and 10% [v/v] glycerol). The purified proteins were buffer exchanged for 50-mm sodium P (pH 7.0), 1-mm AsA with a PD SpinTrap G-25 (GE Healthcare). Preparation of reconstituted recombinant APX1 proteins were performed as described in Dalton et al. (1996) with some modification. The buffer-exchanged proteins were reconstituted with 0.1-mm Hemin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min at 4°C. The reconstituted proteins were buffer-exchanged for 50-mm sodium P (pH 7.0), with an Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Unit, 10 KD (Merck), to remove the unincorporated Hemin. The protein concentration was measured using the DC Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad) and 0.05- or 0.25-μg purified proteins were used for the labeling or activity assays, respectively.

Click Chemistry

Cyanine3 azide, 2.5-μm (Cy3-azide, Lumiprobe; 50-μm stock in DMSO) or 25-μm Azide-PEG3-biotin conjugate (Biotin-azide, Sigma-Aldrich; 500-μm stock in DMSO) and the premixture of 100-μm Tris ([(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol4-yl)methyl]amine, 3.4-mm stock in DMSO/tert-Butanol 1:4), 2-mm Tris ([2-carboxyethyl]phosphine hydrochloride, 100-mm stock in water), and 1-mm copper(II) sulfate (50-mm stock in water) were added to the protein samples up to a 50-μL total reaction volume in the stated order. The samples were allowed to react for 1 h at RT in the dark. The reactions were quenched by acetone precipitation. The protein pellets were resuspended in 2gel loading buffer (100-mm Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 200-mm dithiotreitol, 20% [v/v] glycerol, 4% [w/v] SDS, 0.02% [w/v] bromophenol blue).

Fluorescence Gel Imaging

The labeled proteins were separated on 15% protein gels and detected on the protein gels with a Typhoon FLA 9000 scanner at excitation: 488/emission: 520 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Subsequent to fluorescence imaging, the gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250. The fluorescence of the labeled proteins was quantified using the software ImageJ (U.S. National Institutes of Health).

Large-Scale Labeling and Pull-Down

The extracts from three biological replicates were incubated with 50-μm probes for 1 h at RT in the dark at a 10-mL total reaction volume. The labeling reactions were quenched by chloroform/methanol precipitation (Wessel and Flügge, 1984). The protein pellets were resuspended in 4.4 mL of PBS-SDS buffer by sonication three times for 10 s and heated at 90°C for 10 min. To preclear the endogenously biotinylated proteins from the protein samples, 500 μL of Pierce High Capacity Streptavidin Agarose (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to the samples and incubated at RT for 1 h. The supernatant was retained. Alkyne-labeled proteins were biotinylated using click chemistry with biotin-azide as described under "Click Chemistry" at a 5-mL total reaction volume. The reaction was quenched by adding 10-mm EDTA and undertaking chloroform/methanol precipitation. The pellets were resuspended in 4 mL of 1.2% (w/v) SDS dissolved in 1× PBS (pH 7.4) solution by sonication and further diluted by adding 20 mL of 1× PBS. The resulting solution was incubated with 200 μL of High Capacity Streptavidin Agarose (Pierce) at RT for 2 h. The beads containing the labeled proteins were collected by centrifugation at 1,300g for 3 min at RT. These beads were washed successively three times with 10 mL of PBS-SDS buffer and three times with 10 mL of 1× PBS buffer. The captured proteins were eluted in 50 μL of the 4gel loading buffer containing 5-mm d-Biotin (Invitrogen) by heating at 95°C for 5 min. The eluted proteins were separated on 15% protein gels and the protein gels were stained with SYPRO Ruby (Invitrogen) and detected with ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) at an excitation wavelength of 460 nm with an Y515 Di filter.

In-Gel Trypsin/Lys-C Digestion and MS

The gel bands and lanes were excised and treated with Trypsin/Lys-C Mix (Promega) as described, with minor modifications, in Shevchenko et al. (2006). Peptides were separated on an Ultimate 3000 UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and electrosprayed directly into a QExactive Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) The peptides were trapped on a C18 PepMap100 precolumn (300 µm i.d. × 5 mm, 100 Å, Thermo Fisher Scientific) using solvent A (0.1% formic acid [FA] in water) at a pressure of 500 bar, then separated on an in-house packed analytical column (75 μm i.d. packed with ReproSil-Pur 120 C18-AQ, 1.9 μm, 120 Å; Dr. Maisch). Data were acquired in a data-dependent mode. Full-scan MS spectra were acquired in the Orbitrap (scan range 350–1,500 m/z, resolution 70,000, automatic gain control target 3e6, maximum injection time 50 ms). The 10 most intense peaks were selected for higher-energy collisional dissociation fragmentation at 30% of normalized collision energy at resolution 17,500, automatic gain control target 5e4, maximum injection time 120 ms with first fixed mass at 180 m/z. Charge exclusion was selected for unassigned and 1+ ions.

On-Bead Trypsin Digestion and MS

On-beads digestion were performed as described in Weerapana et al. (2007) with minor modifications. The acidified tryptic digests were desalted on home-made 2-disc C18 StageTips (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as described in Rappsilber et al. (2007). After elution from the StageTips, samples were dried using a vacuum concentrator (Eppendorf) and the peptides were taken up in 10-μL 0.1% FA solution. Samples were analyzed on an Orbitrap Elite instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Michalski et al., 2012) that was coupled to an EASY-nLC 1000 liquid chromatography (LC) system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The LC was operated in the one-column mode. The analytical column was a fused silica capillary (75 µm × 34 cm) with an integrated PicoFrit emitter (New Objective) packed in-house with Reprosil-Pur 120 C18-AQ 1.-µm resin (Dr. Maisch). The analytical column was encased by a column oven (Sonation) and attached to a nanospray flex ion source (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The column oven temperature was adjusted to 45°C during data acquisition. The LC was equipped with two mobile phases: solvent A (0.1% FA in water) and solvent B (0.1% FA in acetonitrile). All solvents were of ultra performance LC grade (Sigma-Aldrich). Peptides were directly loaded onto the analytical column with a maximum flow rate that would not exceed the set pressure limit of 980 bar (usually ∼0.6–1.0 μL/min). Peptides were subsequently separated on the analytical column by running a 140-min gradient of solvent A and solvent B (start with 7% B; gradient 7% to 35% B for 120 min; gradient 35% to 100% B for 10 min; and 100% B for 10 min) at a flow rate of 300 nL/min. The mass spectrometer was operated using the software Xcalibur (v2.2, SP1.48; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The mass spectrometer was set in the positive ion mode. Precursor ion scanning was performed in the Orbitrap analyzer (using Fourier transform MS) in the scan range of m/z 300–1800 and at a resolution of 60,000 with the internal lock mass option turned on (lock mass was 445.120025 m/z, polysiloxane; Olsen et al., 2005). Product ion spectra were recorded in a data-dependent fashion in the ion trap (ion trap MS) in a variable scan range and at a rapid scan rate. The ionization potential (spray voltage) was set to 1.8 kV. Peptides were analyzed using a repeating cycle consisting of a full precursor ion scan (3.0 × 106 ions or 50 ms) followed by 15 product ion scans (1.0 × 104 ions or 50 ms) where peptides are isolated based on their intensity in the full survey scan (threshold of 500 counts) for MS/MS generation that permits peptide sequencing and identification. Collision-induced dissociation energy was set to 35% for the generation of MS/MS spectra. During MS/MS data acquisition, dynamic ion exclusion was set to 120 s with a maximum list of excluded ions consisting of 500 members and a repeat count of one. Ion injection time prediction, preview mode for the Fourier transform MS, monoisotopic precursor selection, and charge state screening were enabled. Only charge states higher than 1 were considered for fragmentation.

Peptide and Protein Identification Using MaxQuant

RAW spectra were submitted to an “Andromeda” (Cox et al., 2011) search in the software MaxQuant (v1.5.3.30) using the default settings (Cox and Mann, 2008). Label-free quantification and match-between-runs was activated (Cox et al., 2014). For Arabidopsis experiments, the MS/MS spectra data were searched against the UniProt Arabidopsis reference database (UP000006548_3702.fasta, 39,372 entries, downloaded 3/18/2018). For the mixed proteome experiments, we searched against all UniProt databases for the respective organisms at once (UP000006548_3702.fasta [Arabidopsis, 39,372 entries]; UP000004994_4081.fasta [S. lycopersicum, 33,952 entries]; UP000007305_4577.fasta [Z. mays, 99,369 entries]; UP000059680_39947.fasta [O. sativa ssp japonica, 48,932 entries]; UP000077202_1480154.fasta [M. polymorpha, 17,951 entries]; all downloaded 3/18/2018). All searches included a contaminants database search (as implemented in MaxQuant, 245 entries).

The contaminants database contains known MS contaminants and was included to estimate the level of contamination. Andromeda searches allowed oxidation of Met residues (16 D) and acetylation of the protein N terminus (42 D) as dynamic modifications and the static modification of Cys (57 D, alkylation with iodoacetamide). Enzyme specificity was set to “Trypsin/P” with two missed cleavages allowed. The instrument type in Andromeda searches was set to “Orbitrap” and the precursor mass tolerance was set to ±20 ppm (first search) and ±4.5 ppm (main search). The MS/MS match tolerance was set to ±0.5 D. The peptide spectrum match false discovery rate and the protein false discovery rate were set to 0.01 (based on target-decoy approach). Minimum peptide length was seven amino acids. For protein quantification, unique and razor peptides were allowed. Modified peptides were allowed for quantification. The minimum score for modified peptides was 40. Label-free protein quantification was switched on, and unique and razor peptides were considered for quantification with a minimum ratio count of 2. Retention times were recalibrated based on the built-in nonlinear time-rescaling algorithm. MS/MS identifications were transferred between LC-MS/MS runs with the “match between runs” option in which the maximal match time window was set to 0.7 min and the alignment time window set to 20 min. The quantification is based on the “value at maximum” of the extracted ion current. At least two quantitation events were required for a quantifiable protein. Further analysis and filtering of the results was done in the software Perseus (v1.5.5.3; Tyanova et al., 2016). For quantification, we combined related biological replicates to categorical groups and investigated only those proteins that were found in at least one categorical group in a minimum of four out of five biological replicates. Comparison of protein group quantities (relative quantification) between different MS runs is based solely on the label-free quantifications as calculated by the software MaxQuant, using the “MaxLFQ” algorithm (Cox et al., 2014).

Phylogenetic Analysis of APX Homologs

Homologs of Arabidopsis APX1/2/3/5/S/T were retrieved from GenBank (A. thaliana RefSeq proteins) and from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (S. lycopersicum Heinz 1706 annotation release 103, O. sativa Japonica group Nipponbare annotation release 102, Z. mays B73 annotation release 102, M. polymorpha strain Tak-1, S. oleracea cv Sp75 annotation release 100, C. cajan annotation release 100, and Selaginella moellendorffii annotation release 100). N. benthamiana APX homologs were extracted from the reannotated gene-models (Kourelis et al., 2018) and manually verified against the draft genome of N. benthamiana (Bombarely et al., 2012). The peroxidase-domain (PF00141) was extracted and aligned using the software Clustal Omega (Sievers et al., 2011). The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Le_Gascuel_2008 model (Le and Gascuel, 2008). The bootstrap consensus tree inferred from 1,000 replicates is taken to represent the evolutionary history of the taxa analyzed (Felsenstein, 1985). The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) are shown next to the branches. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying “Neighbor-Join” and “BioNJ” algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using a Jones–Taylor–Thornton model, and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. A discrete Gamma distribution was used to model evolutionary rate differences among sites (five categories [+G, parameter = 0.9163]). The rate variation model allowed for some sites to be evolutionarily invariable ([+I], 6.90% sites). The analysis involved 66 amino acid sequences. All positions with <80% site coverage were eliminated. That is, <20% alignment gaps, missing data, and ambiguous bases were allowed at any position. There was a total of 203 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in the software MEGA X (Kumar et al., 2018).

APX Activity Assay

APX activity was measured using the spectrophotometric method described in Nakano and Asada (1981) with some modifications. Leaves of four-week–old Arabidopsis plants were frozen with liquid nitrogen and ground with a mortar and pestle. Total proteins were extracted in the extraction buffer (50-mm sodium P buffer [pH 7.0], 2-mm l-ascorbic acid, 0.1-mm EDTA, 10% [w/v] glycerol, and 2% [w/v] PVPP) equivalent to 10 times the fresh weight of the plant tissues. The extracts were centrifuged at 13,000g for 20 min at 4°C and the supernatant containing the soluble proteins were retained. The protein concentration of the supernatant was measured using a DC Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad) and adjusted to 0.05 mg/mL with the extraction buffer. The extracts were incubated with 50-μm KSC-3 or 1% DMSO for 1 h at RT in the dark. The enzymatic reaction was initiated by adding 0.1 mg of labeled protein extracts to the reaction buffer (50-mm potassium P buffer at pH 7.0; 1-mm H2O2, 0.5-mm ascorbate; and 0.1-mm EDTA) on the 96-well UV plate (Costar) at a 200-μL total reaction volume. The decrease in absorbance as ascorbate are oxidized was recorded using an Infinite M200 plate reader (Tecan) at 290 nm (extinction coefficient of ascorbate [E] = 2.8 mM−1 cm−1) at an interval of 30 s up to 90 s; the APX activity is expressed in mmol ascorbate oxidized per min per mg total protein.

APX activity of recombinant protein was measured using the spectrophotometric method described in Dalton et al. (1996) with some modifications. The recombinant proteins were preincubated with the corresponding chemicals at 1 mm for 10 min at RT before the enzymatic assay. The enzymatic reactions were initiated by addition of the protein solution to the reaction buffer (50-mm potassium P buffer at pH 7.0, 1-mm H2O2, and 2-mm ascorbate) on the 96-well UV plate (Costar) in a 200-μL total reaction volume. The decrease in absorbance was recorded using the model no. M200 plate reader (Infinite) at 290 nm (extinction coefficient of ascorbate [E] = 2.8 mM−1 cm−1) for 18 s.

KSC-3 Phytotoxicity Assay of Arabidopsis Plants

Arabidopsis plants were grown on the Murashige and Skoog agarose plate (one-third strength Murashige and Skoog-modified basal salt mixture [Sigma-Aldrich] containing 0.8% multipurpose agarose [Sigma-Aldrich]) containing 219 μm (40 mg/L) KSC-3 or equal amount of DMSO solvent in 96-well microtiter plates for one week at 25°C under a day/night light regime with a 16-h photoperiod at a photon density of 100 ± 10 μmol photons m−2 s−1 or 250 ± 10 μmol m−2 s−1. The Fv/Fm ratio was measured using a CF Imager chlorophyll fluorescence imaging system (Technologica) as described in Trösch et al. (2015) with minor modifications. The Arabidopsis plants were dark-adapted for 30 min and subsequently recorded under saturating light pulses of 6,000 μmol photons m−2 s−1. The Fv/Fm ratio values were determined by the CF Imager’s software.

Accession Numbers

The MS proteomics data for the on-bead digestions have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE (Vizcaíno et al., 2016) partner repository (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/) with the dataset identifier PXD012497. Accession codes of the main studied proteins are APX1 (At1g07890), APX2 (At3g09640), APX3 (At4g35000), and SAPX (At4g08390).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Selective labeling by KSC-3 at high probe concentration and prolonged labeling time.

Supplemental Figure S2. Alignment of the enriched APX proteins.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jianru Zuo for sending materials for expressing APX1. We also thank Prof. Paul Jarvis, Dr. Qihua Ling, Dr. Ane Kjerstie Vie, Dr. Balakumaran Chandrasekar, Dr. Sophie Oliver, and Dr. Samantha Hall for their suggestions and technical support.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Strategic Young Investigator Overseas Visit Program for Enhanced Brain Circulation of the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS grant to K.M.), the John Fell Fund (to K.M.), the European Research Council (ERC Consolidator grant 616449 “GreenProteases” to K.M., J.K., and R.H.), the Clarendon Fund (to J.K.), the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC grants BB/R017913/1 and BB/S003193/1 to R.H.), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH grants 1R01GM117004 and 1R01GM118431-01A1 to E.W.).

References

- Banerjee R, Pace NJ, Brown DR, Weerapana E (2013) 1,3,5-Triazine as a modular scaffold for covalent inhibitors with streamlined target identification. J Am Chem Soc 135: 2497–2500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behki R, Topp E, Dick W, Germon P (1993) Metabolism of the herbicide atrazine by Rhodococcus strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 59: 1955–1959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombarely A, Rosli HG, Vrebalov J, Moffett P, Mueller LA, Martin GB (2012) A draft genome sequence of Nicotiana benthamiana to enhance molecular plant-microbe biology research. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 25: 1523–1530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broser M, Glöckner C, Gabdulkhakov A, Guskov A, Buchta J, Kern J, Müh F, Dau H, Saenger W, Zouni A (2011) Structural basis of cyanobacterial photosystem II Inhibition by the herbicide terbutryn. J Biol Chem 286: 15964–15972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekar B, Colby T, Emran Khan Emon A, Jiang J, Hong TN, Villamor JG, Harzen A, Overkleeft HS, van der Hoorn RAL (2014) Broad-range glycosidase activity profiling. Mol Cell Proteomics 13: 2787–2800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole KS, Grandjean JMD, Chen K, Witt CH, O’Day J, Shoulders MD, Wiseman RL, Weerapana E (2018) Characterization of an A-site selective protein disulfide isomerase A1 inhibitor. Biochemistry 57: 2035–2043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Mann M (2008) MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol 26: 1367–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Neuhauser N, Michalski A, Scheltema RA, Olsen JV, Mann M (2011) Andromeda: A peptide search engine integrated into the MaxQuant environment. J Proteome Res 10: 1794–1805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Hein MY, Luber CA, Paron I, Nagaraj N, Mann M (2014) Accurate proteome-wide label-free quantification by delayed normalization and maximal peptide ratio extraction, termed MaxLFQ. Mol Cell Proteomics 13: 2513–2526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton DA, Diaz del Castillo L, Kahn ML, Joyner SL, Chatfield JM (1996) Heterologous expression and characterization of soybean cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase. Arch Biochem Biophys 328: 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davletova S, Rizhsky L, Liang H, Shengqiang Z, Oliver DJ, Coutu J, Shulaev V, Schlauch K, Mittler R (2005) Cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase 1 is a central component of the reactive oxygen gene network of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17: 268–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durner J, Klessig DF (1995) Inhibition of ascorbate peroxidase by salicylic acid and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acid, two inducers of plant defense responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 11312–11316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. (1985) Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39: 783–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner G. (1981) Azidoatrazine: Photoaffinity label for the site of triazine herbicide action in chloroplasts. Science 211: 937–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong TN, van der Hoorn RAL (2014) DIGE-ABPP by click chemistry: Pairwise comparison of serine hydrolase activities from the apoplast of infected plants. Methods Mol Biol 1127: 183–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honkanen S, Jones VAS, Morieri G, Champion C, Hetherington AJ, Kelly S, Proust H, Saint-Marcoux D, Prescott H, Dolan L (2016) The mechanism forming the cell surface of tip-growing rooting cells is conserved among land plants. Curr Biol 26: 3238–3244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman DD, Blake J (1970) Degradation of atrazine by soil fungi. Soil Biol Biochem 2: 73–80 [Google Scholar]

- Kourelis J, Kaschani F, Grosse-Holz FM, Homma F, Kaiser M, Van der Hoorn RAL (2018) Re-annotated Nicotiana benthamiana gene models for enhanced proteomics and reverse genetics. bioRxiv 373506 [Google Scholar]

- Krutz LJ, Senseman SA, McInnes KJ, Zuberer DA, Tierney DP (2003) Adsorption and desorption of atrazine, desethylatrazine, deisopropylatrazine, and hydroxyatrazine in vegetated filter strip and cultivated soil. J Agric Food Chem 51: 7379–7384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K (2018) MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol 35: 1547–1549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster CRD, Michel H (1999) Refined crystal structures of reaction centres from Rhodopseudomonas viridis in complexes with the herbicide atrazine and two chiral atrazine derivatives also lead to a new model of the bound carotenoid. J Mol Biol 286: 883–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le SQ, Gascuel O (2008) An improved general amino acid replacement matrix. Mol Biol Evol 25: 1307–1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBaron HM. (2011) The Triazine Herbicides. Elsevier, New York [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald IK, Badyal SK, Ghamsari L, Moody PC, Raven EL (2006) Interaction of ascorbate peroxidase with substrates: A mechanistic and structural analysis. Biochemistry 45: 7808–7817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruta T, Noshi M, Tanouchi A, Tamoi M, Yabuta Y, Yoshimura K, Ishikawa T, Shigeoka S (2012) H2O2-triggered retrograde signaling from chloroplasts to nucleus plays specific role in response to stress. J Biol Chem 287: 11717–11729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruta T, Sawa Y, Shigeoka S, Ishikawa T (2016) Diversity and evolution of ascorbate peroxidase functions in chloroplasts: More than just a classical antioxidant enzyme? Plant Cell Physiol 57: 1377–1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalski A, Damoc E, Lange O, Denisov E, Nolting D, Müller M, Viner R, Schwartz J, Remes P, Belford M, et al. (2012) Ultra high resolution linear ion trap Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Orbitrap Elite) facilitates top down LC MS/MS and versatile peptide fragmentation modes. Mol Cell Proteomics 11: O111.013698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Suzuki N, Rizhsky L, Hegie A, Koussevitzky S, Mittler R (2007) Double mutants deficient in cytosolic and thylakoid ascorbate peroxidase reveal a complex mode of interaction between reactive oxygen species, plant development, and response to abiotic stresses. Plant Physiol 144: 1777–1785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody PCE, Raven EL (2018) The nature and reactivity of ferryl heme in compounds I and II. Acc Chem Res 51: 427–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto K, van der Hoorn RAL (2016) The increasing impact of activity-based protein profiling in plant science. Plant Cell Physiol 57: 446–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y, Asada K (1981) Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol 22: 867–880 [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JV, de Godoy LM, Li G, Macek B, Mortensen P, Pesch R, Makarov A, Lange O, Horning S, Mann M (2005) Parts per million mass accuracy on an Orbitrap mass spectrometer via lock mass injection into a C-trap. Mol Cell Proteomics 4: 2010–2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pnueli L, Liang H, Rozenberg M, Mittler R (2003) Growth suppression, altered stomatal responses, and augmented induction of heat shock proteins in cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase (Apx1)-deficient Arabidopsis plants. Plant J 34: 187–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappsilber J, Mann M, Ishihama Y (2007) Protocol for micro-purification, enrichment, pre-fractionation and storage of peptides for proteomics using StageTips. Nat Protoc 2: 1896–1906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong Tan L, Chen Lu Y, Jing Zhang J, Luo F, Yang H (2015) A collection of cytochrome P450 monooxygenase genes involved in modification and detoxification of herbicide atrazine in rice (Oryza sativa) plants. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 119: 25–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seffernick JL, Wackett LP (2016) Ancient evolution and recent evolution converge for the biodegradation of cyanuric acid and related triazines. Appl Environ Microbiol 82: 1638–1645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon DA, Banerjee R, Webster ER, Bak DW, Wang C, Weerapana E (2014) Investigating the proteome reactivity and selectivity of aryl halides. J Am Chem Soc 136: 3330–3333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko A, Tomas H, Havlis J, Olsen JV, Mann M (2006) In-gel digestion for mass spectrometric characterization of proteins and proteomes. Nat Protoc 1: 2856–2860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Söding J, et al. (2011) Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol 7: 539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Kumar V, Chauhan A, Datta S, Wani AB, Singh N, Singh J (2018) Toxicity, degradation and analysis of the herbicide atrazine. Environ Chem Lett 16: 211–237 [Google Scholar]

- Trösch R, Töpel M, Flores-Pérez Ú, Jarvis P (2015) Genetic and physical interaction studies reveal functional similarities between ALB3 and ALB4 in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 169: 1292–1306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyanova S, Temu T, Sinitcyn P, Carlson A, Hein MY, Geiger T, Mann M, Cox J (2016) The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat Methods 13: 731–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaíno JA, Csordas A, Del-Toro N, Dianes JA, Griss J, Lavidas I, Mayer G, Perez-Riverol Y, Reisinger F, Ternent T, et al. (2016) 2016 update of the PRIDE database and its related tools. Nucleic Acids Res 44: 11033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerapana E, Speers AE, Cravatt BF (2007) Tandem orthogonal proteolysis-activity-based protein profiling (TOP-ABPP)—a general method for mapping sites of probe modification in proteomes. Nat Protoc 2: 1414–1425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerapana E, Simon GM, Cravatt BF (2008) Disparate proteome reactivity profiles of carbon electrophiles. Nat Chem Biol 4: 405–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessel D, Flügge UI (1984) A method for the quantitative recovery of protein in dilute solution in the presence of detergents and lipids. Anal Biochem 138: 141–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright MH, Sieber SA (2016) Chemical proteomics approaches for identifying the cellular targets of natural products. Nat Prod Rep 33: 681–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AT, Song JD, Cravatt BF (2009) A suite of activity-based probes for human cytochrome P450 enzymes. J Am Chem Soc 131: 10692–10700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Mu J, Chen L, Feng J, Hu J, Li L, Zhou JM, Zuo J (2015) S-nitrosylation positively regulates ascorbate peroxidase activity during plant stress responses. Plant Physiol 167: 1604–1615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]