Abstract

Background

Female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers have an increased lifetime risk of developing breast and/or ovarian cancer. Hence, they face the difficult decision of choosing a preventive strategy such as risk-reducing surgeries or intensified breast screening. To help these women during their decision process, several patient decision aids (DA) were developed and evaluated in the last 15 years. Until now, there is no conclusive evidence on the effectiveness of these DA. This study aims 1) to provide the first systematic literature review about DA addressing preventive strategy decisions for female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, 2) to analyze the quality of the existing evidence, 3) to evaluate the effects of DA on decision and information related outcomes, on the actual choice for preventive measure and on health outcomes.

Methods

A systematic literature review was conducted using six electronic databases (inclusion criteria: DA addressing preventive strategies, female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, 18 to 75 years, knowledge of test result). The quality of the included randomized controlled trials (RCT) was evaluated with the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool. The quality of included one-group pretest-posttest design studies was evaluated with the ROBINS-I tool. Outcomes of included studies were extracted and qualitatively summarized.

Results

A total of 2093 records were identified. Six studies were included for further evaluation (5 RCT, 1 one-group pretest-posttest design study). One RCT was formally included, but data presentation did not allow for further analyses. The risk of bias was high in three RCT and unclear in one RCT. The risk of bias in the one-group pretest-posttest study was serious. The outcome assessment showed that the main advantages of DA are linked to the actual decision process: Female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers using a DA had less decisional conflict, were more likely to reach a decision and were more satisfied with their decision.

Conclusions

Decision aids can support female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers during their decision process by significantly improving decision related outcomes. More high-quality evidence is needed to evaluate possible effects on information related outcomes, health outcomes and the actual choice for preventive measures.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12911-019-0872-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: BRCA1 and BRCA2, Female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, Familial breast cancer, Familial ovarian cancer, Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, HBOC, Decision aid, Decision-making

Background

Approximately 0.1 to 0.3% of all women carry a mutation in one of the so-called breast cancer genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 [1–5]. These women have an increased lifetime risk of developing breast (BC) and ovarian cancer (OC). According to population-based studies, the average cumulative risks in BRCA1 mutation carriers by age 80 years are 72% for BC and 44% for OC. The corresponding estimates for BRCA2 are 69 and 17% [6].

Genetic testing and counselling for a BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation is strongly recommended for women with a family history or a personal history of BC and/or OC, which is potentially associated with hereditary mutations [7]. A positive genetic test result is followed by a series of questions and difficult, far-reaching decisions. Unaffected mutation carriers have to determine how they want to manage the elevated risk of developing cancer, considering their individual life situation and personal values. Mutation carriers with a personal history of BC and/or OC confront an even more complicated decision-making process: A woman with unilateral BC has to consider different competing risks when taking a decision, such as the risk of developing contralateral cancer, the risk of an ipsilateral relapse, the risk of developing OC, and the risks arising from the primary cancer disease.

Current strategies for female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers to manage the elevated cancer risk include an intensified breast screening program (including magnetic resonance imaging, breast ultrasound, mammography, and breast palpation by a physician) as well as risk-reducing surgeries [7]. To date there is no effective OC screening program [8, 9]. For some women with a BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation, another strategy to reduce the elevated cancer risk is chemoprevention (e.g. tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitors) [10, 11]. Furthermore, some studies indicate that the cancer risk of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers might be reduced by a healthy lifestyle (e.g. no smoking, physical activity) [12, 13].

Surgical options include risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (RR-BSO), risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy (RR-BM) and risk-reducing contralateral mastectomy (RR-CM). The latter is an option for mutation carriers after unilateral BC. The decision for a risk-reducing mastectomy (RR-M) is again followed by a series of upcoming questions, such as considering the surgical technique (e.g. complete, skin sparing or nipple sparing mastectomy) and having a breast reconstruction or not. The decision for a RR-BSO is followed by the question of whether receiving hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and, when indicated, which type of HRT should be chosen. Before choosing RR-BSO family planning should be completed.

In such complex situations, which require weighing up advantages and disadvantages of options, patient decision aids (DA) might be useful to support individual decision making. DA are tools for people seeking advice. The International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration defines them as “tools designed to help people participate in decision making about health care options. They provide information on the options and help patients clarify and communicate the personal value they associate with different features of the options” [14]. DA are generally used for complex decisions: 1) When there is more than one adequate option, 2) when no option has a clear advantage regarding health outcomes, 3) when each option has benefits, harms and uncertainties that the consumer may value differently, and – in some cases – 4) when the scientific evidence about options is limited [14, 15]. Complex decisions can be choices about medical screening, treatment or preventive options. The aim of DA is to reduce the consumers’ uncertainties and confusion, as well as to improve the quality of decisions – or as O’Connor states: “increase the likelihood that consumers will make ‘effective’ decisions” [16]. An “effective” decision is a decision that is informed, consistent with personal values, and acted upon [16].

Since a positive result of a BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene test is followed by a series of questions and difficult decisions, the need for adequate counseling is high. In this situation the use of a DA might be valuable during the decision-making process. A previous systematic literature review has shown that DA concerning different health decisions when compared to usual care, can improve the consumers’ knowledge and reduce their decisional conflict [17].

In the last 15 years several DA for female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers were developed. Although some were evaluated in randomized controlled trials (RCT) or qualitative studies, to date, there is no systematic literature review about the effectiveness of DA for female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers.

The aim of this review is to provide the first systematic literature review about the effectiveness of DA for female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, to analyze the quality of the existing evidence and to evaluate the effects of DA on decision related outcomes, information related outcomes, actual choice for preventive measure and health outcomes.

Methods

Literature search

The electronic databases MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ERIC, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews were searched. We selected these databases since they focus on health, nursing and psychology publications. The search strategy included two categories of search terms: decision-making/decision aid and BRCA1/2. The search strategy was tailored to the requirements of each individual database (see Additional file 1). Whenever feasible, we followed the PRISMA guidelines [18]. Throughout the literature search we used the definition of DA provided by the IPDAS Collaboration [14, 19]. The final database research was performed February 5th, 2019.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included original studies evaluating the effectiveness of DA for women aged 18 to 75 years, who were tested positive for a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation and know their genetic test result. Furthermore, we only included DA addressing preventive strategy decisions. Publications were excluded if they did not meet the inclusion criteria or if they addressed the question of whether to undergo genetic testing. We also excluded studies regarding the development, the structure, and the implementation of DA for female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers as well as studies evaluating other types of decision support such as decision coaching. There were no language restrictions. Publications in languages other than German, English, French and Spanish were translated by native speakers. A restriction to specific study designs was not implemented, since we wanted to give an overview of the whole existing evidence. There were no restrictions regarding the year of publication or the publication status.

Paper coding

After removing the duplicate results, titles and abstracts were screened according to the eligibility criteria independently by two reviewers (LK, SKF). They were rejected if the reviewers determined from the title or abstract that the study did not meet the inclusion criteria. After this screening process, full texts were retrieved and further assessed for eligibility independently by two reviewers. Any disagreement was solved by discussion among the reviewers.

Quality of included studies

The quality of RCT was evaluated using the Cochrane Collaborations’ risk of bias tool [20]. This tool uses seven criteria to measure quality: 1) random sequence generation, 2) allocation concealment, 3) blinding of participants and personnel, 4) blinding of outcome assessment, 5) incomplete outcome data, 6) selective reporting and 7) other sources of bias [20]. Each criterion was judged to have a low, high or unclear risk of bias. If one criterion of a study was considered as “high risk”, the study was classified as having a high risk of bias overall. The evaluation of study quality was performed independently by two reviewers (LK, SKF). A third reviewer (VV) was consulted in case of disagreement of item ratings.

The quality of the one-group pretest-posttest design study was evaluated with the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies - of Interventions (ROBINS-I) assessment tool [21], which is recommended for quality assessment of non-randomised studies of interventions. This tool uses six bias domains to measure quality: bias 1) due to confounding, 2) due to deviations from intended interventions, 3) due to missing data, 4) in selection of participants into the study, 5) in classification of interventions and 6) in selection of the reported result. Each domain was judged to have a low, moderate, serious or critical risk of bias. If one domain of a study was considered as “critical”, the study was classified as having a critical bias overall. That means that the study should not be included in a synthesis. Only if all the domains would be rated as having a low risk of bias, the study receives an overall rating of “low”. The evaluation of the studies was performed independently by three reviewers (LK, SKF, VV). In case of disagreement of item ratings, the three reviewers discussed until they would reach accordance.

Data extraction and management

One reviewer (LK) extracted the study characteristics and outcome data from the included studies (Tables 1, 3, 4). Two reviewers (SKF, VV) compared the findings independently. We contacted authors to obtain missing data. We evaluated the effects of the DA based on the outcomes used in the trials. Hereby we categorized the outcomes in four categories: 1) decision related outcomes, 2) information related outcomes, 3) actual choice for preventive measure and 4) health outcomes. Due to the heterogeneity of the trials in study design, follow-up periods, and outcomes that hindered a meta-analysis, data were synthesized qualitatively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| RCT - Parallel group | Author | Year of publication | Country | Time of recruitment | Inclusion criteria | No. of subjects randomized | Control: Comparator | Control: No. of subjects | Intervention | Intervention: No. of subjects |

| Individualized survival curves improve satisfaction with cancer risk management decisions in women with BRCA1/2 mutations [22] | Armstrong | 2005 | USA | 2000–2003 | BRCA1- and BRCA2-positive women, with or without BC (no OC, no BC with metastases, no RR-BM + RR-BO) | 32 | Educational booklet | 13 | Educational booklet + binder with comprehension exercise, individualized survival curves and individualized BC incidence curves | 14 |

| Randomized trial of a decision aid for BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers: impact on measures of decision making and satisfaction [23] | Schwartz | 2009 | USA | 2001–2005 | BRCA1- and BRCA2-positive women, with or without BC/OC (no BC with metastases, no OC with metastases, no RR-BM) | 214 | Usual care | 114 | Usual care + interactive CD-ROM with information about BC and risk management options, tailored BC and OC risk graphs and an interactive decision task | 100 |

| Longitudinal changes in patient distress following interactive decision aid use among BRCA1/2 carriers: a randomized trial [24] | Hooker | 2011 | USA | 2001–2005 | BRCA1- and BRCA2-positive women, with or without BC/OC (no BC with metastases, no OC with metastases, no RR-BM) | 214 | Usual care | 114 | Usual care + interactive CD-ROM with information about BC and risk management options, tailored breast and ovarian cancer risk graphs and an interactive decision task | 100 |

| Effect of decision aid for breast cancer prevention on decisional conflict in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation: a multisite, randomized, controlled trial [25] | Metcalfe | 2017 | Canada | 2008–2011 | BRCA1- and BRCA2-positive women, without cancer (no RR-M, no RR-O, no tamoxifen) | 150 | Usual care | 74 | Usual care + booklet with information about BC risks, BC preventive options, guidelines, studies and a possibility to compare the options | 76 |

| RCT - Cross-over trial | Author | Year of publication | Country | Time of recruitement | Inclusion criteria | No. of subjects randomized | Control: Comparator | Group 1: No. of subjects | Intervention | Group 2: No. of subjects |

| Randomised trial of a decision aid and its timing for women being tested for a BRCA1/2 mutation [26] | Van Roosmalen | 2004 | NL | 1999–2001 | BRCA1- and BRCA2-positive women, with or without BC/OC (no distant metastases, no RR-BM + RR-BO; no chemotherapy, radiotherapy or BC/OC surgery 1 month before blood sampling) | 384 | Usual care | T2 (before gen. Testing, gets DA): 184 T3 (positive test result): 47 | Usual care + Brochure with information about treatment options + 45 min. Video with interviews mutation carriers | T2 (before gen. Testing, gets no DA): 184 T3 (positive test result, gets DA): 42 |

| One-Group Pretest-Posttest Design | Author | Year of publication | Country | Time of recruitement | Inclusion criteria | No. of subjects willing to participate | Subjects completing the pre-test questionnaire | Intervention | Subjects completing the post-test questionnaire | |

| Development and testing of a decision aid for breast cancer prevention for women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation [27] | Metcalfe | 2007 | Canada | Not specified | BRCA1- and BRCA2-positive women, without BC/OC | 21 | 21 | Brochure with information about options and outcomes, risks and benefits, a valuing exercise and suggestions for follow-up discussions with their practitioner | 20 | |

RCT randomized controlled trial, NL Netherlands, CD-ROM Compact Disc Read-Only Memory, No. number, DA decision aid, BRCA1 breast cancer gene 1, BRCA2 breast cancer gene 2, OC ovarian cancer, BC breast cancer, RR-BM risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy, RR-M risk-reducing mastectomy, RR-BO risk-reducing bilateral oophorectomy, RR-O risk-reducing oophorectomy, T2 4 weeks after blood sampling, T3 2 weeks after positive test result

Table 3.

Outcomes, instruments used, and effects of decisions aids evaluated in the included RCT

| Outcomes | Instruments used for assessment | RCT using the instrument | a) Score (S.D.) or [range] b) Regression analysis |

p-value | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision related outcomes | |||||

| Decisional conflict | Decisional Conflict Scalea | Schwartz 2009 [23] | b) Intervention, subjects were undecided at randomization: B − 0.35, z − 3.6 | < 0.001 | Significant decreases in decisional conflict in initially undecided women in the DA group. |

| b) Intervention, subjects were decided at randomization: B − 0.10, z − 0.98 | 0.33 | ||||

| Metcalfe 2017 [25] | a) 3 month: Intervention 25.6 (13.2), Control 26.8 (12.6) | 0.59 | No significant effect. | ||

| a) 6 month: Intervention 24.8 (13.8), Control 24.7 (12.8) | 0.96 | ||||

| a) 12 month: Intervention 21.5 (13.7), Control 21.0 (12.3) | 0.81 | ||||

| Satisfaction with decision | Variation of Decisional Conflict Scale/Satisfaction With Decision Scalec | Armstrong 2005 [22] | a) Intervention 31.2, Control 26.2 | 0.04 | Significantly higher decision satisfaction in the DA group. |

| Satisfaction With Decision Scalea | Schwartz 2009 [23] | b) Intervention, subjects were undecided at randomization: B 0.27, z 3.1 | 0.002 | Significant increase in satisfaction with decision in initially undecided women in the DA group. | |

| b) Intervention, subjects were decided at randomization: B − 0.07, z − 0.7 | 0.48 | ||||

| Strenght of treatment preference | 15-point scalec | Metcalfe 2017 [25] | a) Subjects reporting „undecided "(score 6–10): | No significant effect. | |

| RR-M: | |||||

| 3 month: Intervention 19, Control 15 | 0.52 | ||||

| 6 month: Intervention 12, Control 15 | 0.47 | ||||

| 12 month: Intervention 10, Control 15 | 0.81 | ||||

| RR-O: | |||||

| 3 month: Intervention 8, Control 2 | 0.05 | ||||

| 6 month: Intervention 4, Control 7 | 0.33 | ||||

| 12 month: Intervention 6, Control 7 | 0.66 | ||||

| Tamoxifen: | |||||

| 3 month: Intervention 15, Control 15 | 0.89 | ||||

| 6 month: Intervention 10, Control 12 | 0.57 | ||||

| 12 month: Intervention 10, Control 6 | 0.35 | ||||

| Final decision vs. No final decision | Schwartz 2009 [23] | b) Intervention, subjects were undecided at randomization: OR 3.09, 95% CI 1.62, 5.90 | < 0.001 | Significantly increased likelihood to reach a management decision in initially undecided women in the DA group. | |

| b) Intervention, subjects were decided at randomization: OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.24, 1.29 | 0.17 | ||||

| Hooker 2011 [24] | No data are presented. | No data are presented. | |||

| Information related outcomes | |||||

| Risk perception | Knowledge questionnaire (see also Metcalfe 2007)c | Metcalfe 2017 [25] | a) 3 month: Intervention 89.9 (9.4), Control 89.9 (9.8) | 0.98 | No significant effect. |

| 6 month: Intervention 90.1 (10.4), Control 89.7 (12.4) | 0.55 | ||||

| 12 month: Intervention 92.0 (10.3), Control 91.6 (10.2) | 0.84 | ||||

| OC risk, mutation carriersd | Armstrong 2005 [22] | a) Intervention 54.0 [0–90)], Control 42.3 [0–80)] | 0.54 | No significant effect. | |

| BC, risk after RR-M, mutation carriersd | Armstrong 2005 [22] | a) Intervention 15.0 [0–25)], Control 10.3 [0–50] | 0.56 | No significant effect. | |

| BC, risk after RR-O, mutation carriersd | Armstrong 2005 [22] | a) Intervention 40.3 [0–80], Control 23.3 [0–80] | 0.20 | No significant effect. | |

| BC, risk with Tamoxifen, mutation carriersd | Armstrong 2005 [22] | a) Intervention 11.2 [0–60], Control 9.2 [0–40] | 0.26 | No significant effect. | |

| BC, risk with HRT after menopause, mutation carriersd | Armstrong 2005 [22] | a) Intervention 49.5 [0–90], Control 18.8 [0–45] | 0.13 | No significant effect. | |

| BC, risk with Raloxifene after menopause, mutation carriersd | Armstrong 2005 [22] | a) Intervention 42.5 [0–75], Control 12.5 [0–30] | 0.08 | No significant effect. | |

| BC, risk with mammography, mutation carriersd | Armstrong 2005 [22] | a) Intervention 63.8 [0–90], Control 41.7 [0–80] | 0.12 | No significant effect. | |

| OC, risk after RR-O, mutation carriersd | Armstrong 2005 [22] | a) Intervention 6.7 [0–60], Control 6.5 [0–50] | 0.65 | No significant effect. | |

| Actual treatment choice | RR-M vs. No RR-M | Schwartz 2009 [23] | b) 0–12 month, subjects obtaining RR-M: Intervention 18, Control 15, χ2 (df = 1, N = 214) = 0.96 | 0.33 | No difference in DA or control group in having a RR-M or not, but impact of the DA in timing of the RR-M (control: early after testing; DA: 6–12 month after testing). |

| b) 0–1 month, subjects obtaining RR-M: Intervention 0, Control 5, 2-tailed Fisher Exact Test | 0.06 | ||||

| b) 1–6 month, subjects obtaining RR-M: Intervention 8, Control 7, χ2 (df = 1, N = 209) = 0.44 | 0.51 | ||||

| b) 6–12 month, subjects obtaining RR-M: Intervention 10, Control 3, χ2 (df = 1, N = 194) = 3.80 | 0.05 | ||||

| Hooker 2011 [24] | No data are presented. | No data are presented. | |||

| Health outcomes | |||||

| Anxiety | Hopkins Symptom Checklist 25a | Armstrong 2005 [22] | Adjusted mean difference − 2.89e | 0.45 | No significant effect. |

| Revised Impact of Event Scale, intrusion subscaleb | Armstrong 2005 [22] | Adjusted mean difference 0.16e | 0.89 | No significant effect. | |

| Distress | Impact of Event Scalea | Hooker 2011 [24] | b) 0–1 month: B 3.95, z 2.61 | 0.01 | Women in the control group reported significantly decreased distress in the month following randomization compared to women in the DA group. From 1 to 6 months women in the DA group reported significantly reduced distress compared to women who received UC. From 6 to 12 months no significant differences between groups were found. By 12-months, the overall decrease in distress between the two groups was similar. |

| b) 1–6 month: B − 3.71, z − 2.35 | 0.02 | ||||

| b) 6–12 month: B − 1.05, z − 0.67 | 0.51 | ||||

| Metcalfe 2017 [25] | a) 3 month: Intervention 24.6 (13.9), Control 26.8 (12.8) | 0.33 | Women in the DA group showed significantly lower cancer related distress at 6 and 12 month post-randomization compared to the control group. | ||

| a) 6 month: Intervention 19.3 (13.2), Control 25.2 (14.5) | 0.01 | ||||

| a) 12 month: Intervention 17.7 (14.7), Control 22.4 (15.5) | 0.05 | ||||

| Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment Questionnaireb | Hooker 2011 [24] | b) 0–1 month: B 3.08, z 2.01 | 0.04 | At 1 month post-randomization women in the control group showed significantly decreased distress relative to the DA group. From 1 to 6 months and from 6 to 12 months, the groups did not differ significantly in their decrease of distress. | |

| b) 1–6 month: B − 1.35, z − 1.08 | 0.28 | ||||

| b) 6–12 month: B − 0.32, z − 0.25 | 0.80 | ||||

| Brief Symptom Inventory, modified scalec | Hooker 2011 [24] | b) B − 0.46, z − 0.54 | 0.59 | No significant effect. | |

RCT randomized controlled trial, DA decision aid, OC ovarian cancer, BC breast cancer, RR-M risk-reducing mastectomy, RR-O risk-reducing oophorectomy, HRT hormone replacement therapy

aInstrument was validated in a study

bunclear, if instrument was validated

cinstrument was not validated

drisk estimates from 0 to 100%

eUnclear comparison: The time points and groups are not specified

Table 4.

Outcomes, instruments used, and effects of decisions aids evaluated in the included one-group pretest-posttest design study

| Outcomes | Instruments used for assessment | Pretest-posttest study using the instrument | Score (S.D.) | p-value | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision related outcomes | |||||

| Decisional conflict | Decisional Conflict Scalea | Metcalfe 2007 [27] | Pre-test 36.2 (16.4), Post-test 23.0 (15.2) | 0.001 | Significantly less decisional conflict after using the DA. |

| Strenght of treatment preference | 15-point scale | Metcalfe 2007 [27] | RR-M: | Significantly fewer women in the DA group were uncertain about RR-M and RR-O. | |

| Pre-test No 14, Yes 3, Unsure 3 | |||||

| Post-test No 10, Yes 4, Unsure 6 | 0.009 | ||||

| RR-O: | |||||

| Pre-test No 5, Yes 12, Unsure 3 | |||||

| Post-test No 2, Yes 15, Unsure 3 | 0.003 | ||||

| Tamoxifen: | |||||

| Pre-test No 10, Yes 1, Unsure 9 | |||||

| Post-test No 11, Yes 5, Unsure 4 | 0.12 | ||||

| Information related outcomes | |||||

| Risk perception | BC risk, mutation carriersb | Metcalfe 2007 [27] | Pre-test 65.1 (16.1), Post-test 73.6 (13.4) | 0.05 | Significantly better risk perception after using the DA. |

| BC, risk after RR-M, mutation carriersb | Metcalfe 2007 [27] | Pre-test 71.8 (22.0), Post-test 84.2 (18.2) | 0.005 | Significantly better risk perception after using the DA. | |

| BC, risk after RR-O, mutation carriersb | Metcalfe 2007 [27] | Pre-test 43.2 (20.0), Post-test 65.0 (13.3) | 0.001 | Significantly better risk perception after using the DA. | |

| BC, risk with Tamoxifen, mutation carriersb | Metcalfe 2007 [27] | Pre-test 50.0 (19.0), Post-test 56.6 (10.0) | 0.17 | No significant difference. | |

| BC, risk with mammography, mutation carriersb | Metcalfe 2007 [27] | Pre-test 21.5 (28.0), Post-test 13.5 (22.8) | 0.11 | No significant difference. | |

| Health outcomes | |||||

| Distress | Impact of Event Scalea | Metcalfe 2007 [27] | Pre-test 22.7 (13.7), Post-test 19.9 (14.5) | 0.24 | No significant difference. |

DA decision aid, BC breast cancer, RR-M risk-reducing mastectomy, RR-O risk-reducing oophorectomy

ainstrument was validated in a study

brisk estimates from 0 to 100%

Results

Search results

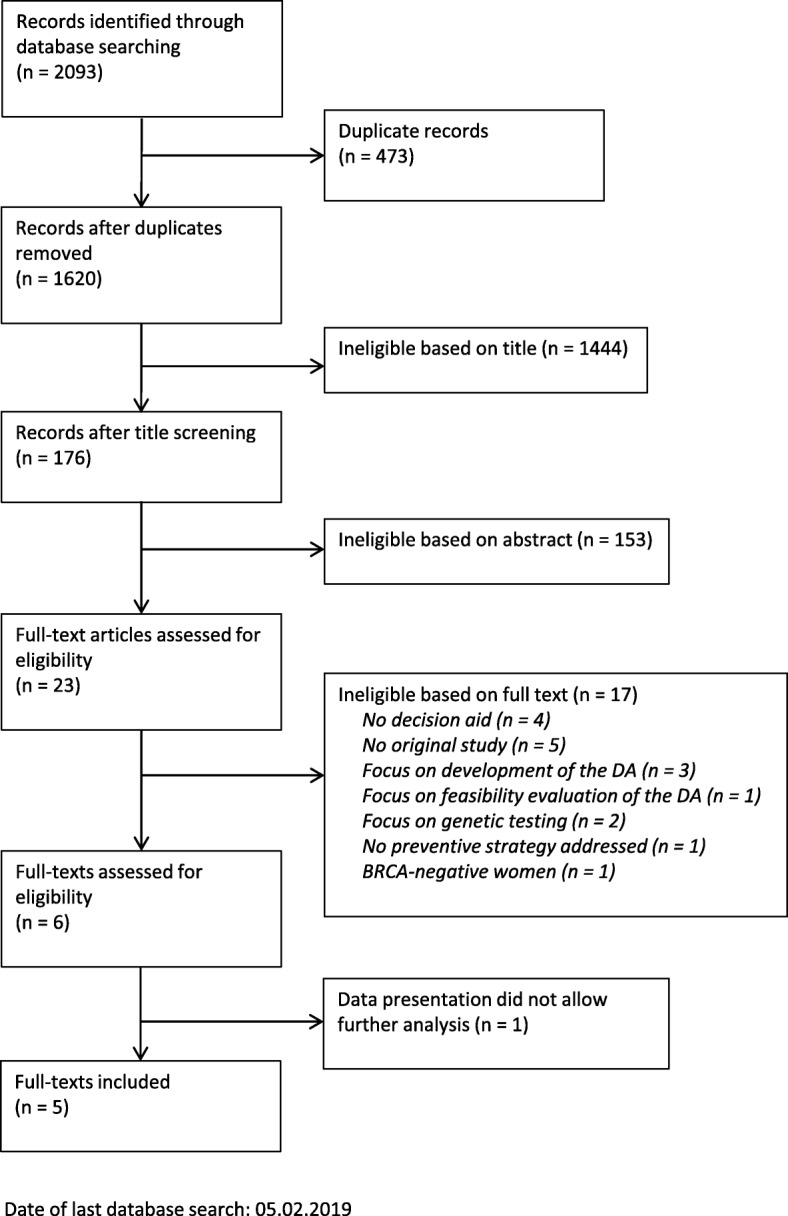

As shown in Fig. 1, a total of 2093 records were identified through database search. Of these records, six full-text studies were included in this review.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of search strategy and study selection, according to the PRISMA guidelines

The main characteristics of the six included studies are shown in Table 1. Five studies are RCT, four of them having a parallel group design [22–25], one conducted as a randomized cross-over trial [26]. One study is a quasi-experiment with a one-group pretest-posttest design [27]. All six studies reported various effects of the DA on decision and information related outcomes, health related outcomes, and actual choice for preventive measure. One study [26] provided outcome data of female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers at a point of time, when the women did not know their BRCA1 or BRCA2 test result yet. Despite contacting the authors and receiving more data, we still could not include the study, since the data set provided by the authors did not allow for tracing back the separate study arm in the form needed for our review.

Quality of included studies

The quality analysis of the included RCT [22–25] showed that three studies were at high risk of bias [23–25] and one was of unclear risk of bias [22] (Table 2). All analyzed RCT adequately randomized patients and had no selective outcome reporting. Only one study reported adequate allocation concealment [22]. All RCT had deficits concerning the blinding of participants, personnel, and/or outcome assessors. A detailed description of the quality assessment of the RCT is provided in Additional file 2.

Table 2.

Quality analysis of RCT according to the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool [20]

| Publication | Armstrong (2005) [22] |

Schwartz (2009) [23] |

Hooker (2011) [24] |

Metcalfe (2017) [25] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion | ||||

| Adequate sequence generation | + | + | + | + |

| Adequate allocation concealment | + | ? | ? | ? |

| Blinding of participants and personnel | (−)b | (−)c | (−)c | – |

| Blinding of outcome assessors | + | -a | -a | -a, d |

| No incomplete outcome data | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| No selective outcome reporting | + | + | + | + |

| No other sources of bias | + | + | + | + |

| RISK OF BIAS | Unclear | High | High | High |

+ Met criterion;? Unclear; − Unmet criterion; RCT: randomized controlled trial

aPatient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) with unblinded patients

bpatients and outcome assessors blinded, staff not blinded

cpatients not blinded, blinding of staff not or not completely mentioned

dresearch assistant blinded but likely that blinding has been broken

The one-group pretest-posttest design study [27] was rated as having a serious risk of bias overall. There were serious deficits in the domains confounding and measurement of outcomes, the article did not provide sufficient information to judge the domain missing data. The bias in the other domains was rated as “low”. A detailed description of the quality assessment of the one-group pretest-posttest design study is provided in Additional file 3.

Effects of the decision aids

The qualitative synthesis of the effectiveness was performed for all included six studies. A variety of outcomes were used to evaluate the effects of the DA. A summary of the outcomes, respective instruments as well as the corresponding main effects of the DA is provided in Tables 3 and 4.

Decision related outcomes

The qualitative synthesis of the evaluation studies showed that DA for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers can have significant beneficial effects on decision related outcomes. Four studies evaluated the decisional conflict [22, 23, 25, 27]: One study showed a significant decline in mean decisional conflict scores in the DA group [27], one detected significant decreases in decisional conflict in initially undecided women using the DA [23] and one showed a significant reduction in scores on seven items from the Decisional Conflict Scale in the intervention group compared to the control [22]. One study evaluating the decisional conflict showed no significant effect between the intervention and the control groups [25].

Four studies measured the strength of treatment preference [23–25, 27]. Of these four, two studies showed a significantly beneficial effect of the DA: One found an increased likelihood to reach a management decision in initially undecided women in the DA group [23], and one showed that fewer women were uncertain about RR-M and risk-reducing oophorectomy [27]. One study evaluating this outcome showed no significant effect between the intervention and the control groups [25] and one study did not present data regarding this outcome [24].

Two studies evaluated the outcome “decision satisfaction” [22, 23]. Of these, one study found a significantly beneficial effect of the DA in initially undecided women [23]. One study using a 12-item-scale that combined items from the Decisional Conflict Scale with the Satisfaction With Decision Scale found that women using the DA were significantly more satisfied with their decision compared to the control group [22, 23]. Nevertheless, when analyzing only the scores of the Satisfaction with Decision Scale, no significant differences were found.

Information related outcomes

Three studies evaluated the influence of the DA on risk perceptions of the affected women [22, 25, 27], two of them showing no significant difference between the DA and the control groups [22, 25]. One study showed a significant increase in knowledge scores [27].

Actual preventive choice

Two studies measured the actual preventive choice made by the included women [23, 24]. One study revealed that regarding the actual preventive choice of RR-M there was no significant difference between the control and the DA group [23]. However, the DA had an impact on the timing of the preventive measure. Women in the control group tended to have a RR-M early after genetic testing, thus not reaching statistical significance, whereas significantly more women using the DA tended to have the procedure 6 to 12 month after genetic testing. One study provided no data about the outcome of the actual preventive choice [24].

Health outcomes

A variety of instruments were used in the trials to determine health outcomes. Three studies measured distress [24, 25, 27] and one anxiety [22].

One study [24] measured distress using three different instruments: The Impact of Event Scale (IES) to measure cancer specific distress, a modified version of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) to measure general distress and the Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment Questionnaire (MICRA) to measure genetic testing distress. Using the IES and the MICRA, the study showed that there were significantly higher distress scores in the DA group than in the control group in the month following randomization. In a subanalysis with women who reported that they actually have used the DA, the genetic testing distress at 12-month post-randomization was significantly lower in the DA group. Using the BSI no significant differences between the two groups were found [24].

Another study using the IES showed that women in the DA group experienced significantly lower cancer related distress at 6- and 12-month post-randomization compared to the control group [25]. One study indicated no significant effect on health outcomes [22].

Discussion

This is the first systematic review of the effectiveness of DA for women with a pathogenic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation who are facing the difficult and complex decision of choosing a preventive strategy that goes well with their individual life situation and personal values. Our review gives an overview of the quality of the existing evidence and summarizes the effects of DA on decision, information and health related outcomes as well as on actual choice for preventive measures.

Quality of included studies

Concerning the study quality three of the four RCT showed a high risk of bias, one showed an unclear risk. The strengths of the included RCT were their adequate sequence generation, their complete outcome reporting and the absence of other sources of bias. The main weakness of the identified studies was the insufficient blinding of patients and personnel. Blinding remains challenging in the field of decision support as recipients usually can recognize the assigned intervention. However, options such as providing a DA versus a non-structured set of information materials or flyers should be considered in future studies. Apart from the four RCT, one study with a one-group pretest-posttest design was included, because it fulfilled the inclusion criteria. This study showed a serious risk of bias. Its main deficits were found in the domains confounding and measurement of outcomes. The weak quality of this study is not surprising, since the one-group pretest-posttest design is often criticized because of different threats to its internal and external validity [28, 29].

In summary, the quality of the studies included in this review is compromised to some extent. The results regarding the effects of the DA must be seen in the light of this weakness.

Decision related outcomes

We found indications that the use of a DA for female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers has some advantages with respect to decision related outcomes. Three studies show that the use of a DA leads to significantly less conflict during the decision-making process [22, 23, 27]. This applies especially to women who are initially undecided. The use of a DA also significantly increases the likelihood to reach a decision in initially undecided women [23]. Finally, two studies demonstrate that mutation carriers using a DA are significantly more satisfied with their decision compared to the control group [22, 23].

Our findings are partly congruent with the results of the most recent Cochrane Collaboration review about the effectiveness of DA for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. In this review 105 RCT involving 31,043 participants were analyzed [17]. The Cochrane Collaboration review contrasts in some points with our review: It included studies about DA for various – and not only one specific – health decisions, it included only studies with an RCT design, and it excluded studies, when the relevant DA were not available. This may explain, why only two of the studies [22, 24] which were included in this review are also apparent in the Cochrane Collaboration review.

Consistent with our results, the Cochrane Collaboration review showed that the use of DA leads to a lower decisional conflict. In contrast to our results, the Cochrane Collaboration review found that the effects on satisfaction are limited. This limited effect is, according to the Cochrane Collaboration review, possibly a consequence of measurement insensitivity: Because satisfaction with usual care is already high, it is difficult to measure differences in satisfaction between DA and control groups. The studies included in the Cochrane Collaboration review used a variety of instruments to measure satisfaction, most of them were not validated. Also, in our review only one of two studies evaluating the effect of the DA on satisfaction used a validated instrument, more precisely the Satisfaction with Decision Scale. Therefore, to make a clear statement about the effects of a DA on satisfaction, more high-quality evidence is needed, including studies using validated and sensitive instruments.

Information related outcomes

The main conclusion of the Cochrane Collaboration review is that the largest benefits of DA compared to usual care, are better knowledge and risk perceptions [17]. These results contrast with our findings. In our review, regarding risk perceptions, two studies [22, 25] showed no significant effect. One study [27] showed a significant increase in knowledge scores, but due to the study design and the lack of a control group without intervention this result cannot carry much weight [28, 29]. There might be several reasons for the differing effects on knowledge. The Cochrane Collaboration included DA designed for 50 different health decisions. The target groups of these DA were heterogeneous in age and sex. We only included DA addressing preventive decisions of mostly middle-aged female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. As younger and middle-aged females have higher levels of health literacy [30, 31] and might have higher knowledge in health topics in general, it could be hypothesized that information related effects might be higher in other populations.

Metcalfe and colleagues [25] reason that they could not detect large changes in knowledge scores, because all included women in their RCT were well informed and already had very high knowledge scores at baseline. This in turn is, according to Metcalfe, a sign of the impact of successful pre- and posttest genetic counselling which ideally leads to an informed patient. This argument can be reinforced by different studies. In a systematic review of Nelson and colleagues eight studies from 2004 to 2011 reported improved accuracy of BC risk perception after genetic counseling [32]. In another systematic review Butow and colleagues are concluding, that genetic counselling is, at least in the short term, successfully enhancing the accuracy of women’s risk perception [33].

Actual preventive choice

Regarding the actual preventive choice, we found only marginal effects of the use of a DA. Although not reaching statistical significance, Schwartz and colleagues [23] demonstrated that more women in the DA group were tending to do a RR-M. Furthermore, they found out that the women in the DA group would do the procedure significantly later than the women in the control group [23]. Schwartz assumes that the delayed RR-M is a sign of a higher grade of deliberation due to the DA.

This argument is supported by a study of Howard and colleagues [34], who performed in-depth interviews with female BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers about the “right time” of considering risk-reducing surgery. According to the study, the interviewed women felt that it is necessary to take enough time to deliberate about risk-reducing surgery decisions. Otherwise, they would not feel “ready” and “able” to make these decisions.

In contrast to our results, the latest Cochrane Collaboration review on DA showed, excluding Schwartz et al. [23], a significant reduction in the number of patients in the DA group choosing major elective surgery [17]. The authors argue that people in the control groups may be more inclined towards surgery due to their deficient or missing awareness of alternatives, benefits and harms. It is important to underline that the results of the Cochrane Collaboration review are based on outcomes of different studies with groups of patients facing different health decisions, such as cardiac revascularization, bariatric surgery and orchiectomy. A direct comparison of these groups to female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers who consider various preventive options, is difficult, especially because their decision for or against risk-reducing surgery is very complex and influenced by many factors such as lifetime risk of developing cancer, family history of cancer, having children and age [35, 36].

Therefore, more high-quality evidence is needed to make a clear statement about the effects on the actual preventive choice of preventive measures by the use of a DA for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers.

Health outcomes

As for health outcomes such as anxiety or distress, two studies revealed an impact of the DA versus the control group which varied over time [24, 25]. One study [24] showed that women in the DA group had significantly higher scores in cancer specific and genetic testing distress in the month following randomization, but significantly less genetic testing distress at 12-month post-randomization. Hooker and colleagues [24] suggested that those short-term increases in distress in the DA group are a sign of ongoing deliberation and cognitive processing. This hypothesis in turn could be supported by the study of Metcalfe and colleagues [25] which demonstrated that the DA group showed significantly lower cancer related distress at 6 and 12 month post-randomization compared to the control group.

In contrast to our results, the effects of DA on health outcomes, such as general health outcomes, anxiety, depression, regret and confidence, in the latest Cochrane Collaboration review were limited [17]. In the Cochrane Collaboration review a variety of different instruments were used to investigate the effects on health outcomes. Nevertheless, the three instruments which were utilized in this review to investigate patients’ distress and showed significant changes – the BSI, the MICRA and the IES – were not part of it. This may explain the different results of the Cochrane Collaboration review on health outcomes, especially on distress, and our work.

Strengths and limitations

Our findings must be considered in the light of the strengths and limitations of this review. The main limitation is that the identified studies showed a high or unclear risk of bias. This might restrict the information value of the validity of DA effectiveness as summarized in this study.

Another limitation is that this review only provides a qualitative summary of the outcome results of the included RCT. A meta-analysis was not possible because the identified studies were heterogeneous in terms of study design, time frame between genetic test result disclosure and delivery of the decision aid, follow-up periods and the choice of outcomes. Moreover, we could not access all the required data from all studies [22–24], despite contacting the authors.

The strengths of this review are its clear search protocol, the inclusion of six different databases and the involvement of three different reviewers. The critical quality assessment based on the well-established Cochrane Collaborations’ risk of bias tool and the ROBINS-I tool ensures a transparent judgement of studies. We included all types of studies and outcomes in our review, which allows to provide a complete overview of the effectiveness of DA for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Moreover, we sent author request to obtain data in other formats so that they might be included in our review.

Conclusions

This is the first systematic review of the effectiveness of DA for women with a pathogenic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Our work indicates that DA may support female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers during their decision process for choosing a preventive measure. This is mainly achieved by improving decision related outcomes. More high-quality evidence is needed to evaluate possible advantages or disadvantages on information related and health outcomes as well as on the actual choice for preventive measures. To provide high-quality evidence and to reach a higher comparability of study results it is important that future research focuses on 1) low-biased study designs and 2) the use of well-established and validated instruments to assess outcomes.

Additional files

Full search strategy for each database. (DOCX 17 kb)

Quality of randomized controlled trials / Rationale. (XLSX 15 kb)

Quality of pretest-posttest study / Rationale. (XLSX 14 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank Dirk Müller (Institute for Health Economics and Clinical Epidemiology, University of Cologne) for useful discussions concerning the search process and the analyses. We thank Arim Shukri (Institute for Health Economics and Clinical Epidemiology, University of Cologne) for useful discussions concerning the analyses. We thank all authors who responded to our request for additional information.

Abbreviations

- BC

Breast cancer

- BRCA1

Breast cancer gene 1

- BRCA2

Breast cancer gene 2

- BSI

Brief Symptom Inventory

- CD-ROM

Compact Disc Read-Only Memory

- DA

Decision aid(s)

- HRT

Hormone replacement therapy

- IES

Impact of Event Scale

- IPDAS

International Patient Decision Aids Standards

- MICRA

Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment Questionnaire

- NL

Netherlands

- OC

Ovarian cancer

- PROM

Patient-reported outcome measures

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial(s)

- RR-BM

Risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy

- RR-BSO

Risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

- RR-CM

Risk-reducing contralateral mastectomy

- RR-M

Risk-reducing mastectomy

- RR-O

Risk-reducing oophorectomy

Authors’ contributions

LK was responsible for the development of the research question, the search strategy and the inclusion and exclusion criteria and the evaluation of the effects of the included studies. She contributed to the screening of titles, abstracts and full texts, and to the evaluation of the quality of the included studies. She was responsible for drafting the manuscript and prepared all tables and figures. VV contributed to the evaluation of the quality of the included studies, to the completion of the manuscript and reviewed the manuscript before submission. SS contributed to the completion of the manuscript and reviewed the manuscript before submission. SK-F contributed to the development of the search strategy and the inclusion and exclusion criteria, to the screening of titles, abstracts and full texts, and to the evaluation of the quality of the included studies. She contributed to the completion of the manuscript and reviewed the manuscript before submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Landeszentrum Gesundheit Nordrhein-Westfalen (LZG.NRW), Bochum, Germany. The funding body had no influence on the design of the study, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and the writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Lisa Krassuski, Email: lisa.krassuski@tu-dortmund.de.

Sibylle Kautz-Freimuth, Email: sibylle.kautz-freimuth@uk-koeln.de.

References

- 1.Balmana J., Diez O., Castiglione M. BRCA in breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Recommendations. Annals of Oncology. 2009;20(Supplement 4):iv19–iv20. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moyer Virginia A. Risk Assessment, Genetic Counseling, and Genetic Testing for BRCA-Related Cancer in Women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014;160(4):271–281. doi: 10.7326/M13-2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peto J, Collins N, Barfoot R, Seal S, Warren W, Rahman N, et al. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations in patients with early-onset breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.11.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antoniou A C, Pharoah P D P, McMullan G, Day N E, Stratton M R, Peto J, Ponder B J, Easton D F. A comprehensive model for familial breast cancer incorporating BRCA1, BRCA2 and other genes. British Journal of Cancer. 2002;86(1):76–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antoniou AC, Gayther SA, Stratton JF, Ponder BA, Easton DF. Risk models for familial ovarian and breast cancer. Genet Epidemiol. 2000. 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2272(200002)18:2<173::AID-GEPI6>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kuchenbaecker Karoline B., Hopper John L., Barnes Daniel R., Phillips Kelly-Anne, Mooij Thea M., Roos-Blom Marie-José, Jervis Sarah, van Leeuwen Flora E., Milne Roger L., Andrieu Nadine, Goldgar David E., Terry Mary Beth, Rookus Matti A., Easton Douglas F., Antoniou Antonis C., McGuffog Lesley, Evans D. Gareth, Barrowdale Daniel, Frost Debra, Adlard Julian, Ong Kai-ren, Izatt Louise, Tischkowitz Marc, Eeles Ros, Davidson Rosemarie, Hodgson Shirley, Ellis Steve, Nogues Catherine, Lasset Christine, Stoppa-Lyonnet Dominique, Fricker Jean-Pierre, Faivre Laurence, Berthet Pascaline, Hooning Maartje J., van der Kolk Lizet E., Kets Carolien M., Adank Muriel A., John Esther M., Chung Wendy K., Andrulis Irene L., Southey Melissa, Daly Mary B., Buys Saundra S., Osorio Ana, Engel Christoph, Kast Karin, Schmutzler Rita K., Caldes Trinidad, Jakubowska Anna, Simard Jacques, Friedlander Michael L., McLachlan Sue-Anne, Machackova Eva, Foretova Lenka, Tan Yen Y., Singer Christian F., Olah Edith, Gerdes Anne-Marie, Arver Brita, Olsson Håkan. Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. JAMA. 2017;317(23):2402. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft DK, AWMF) S3-Leitlinie Früherkennung, Diagnose, Therapie und Nachsorge des Mammakarzinoms, Langversion 4.1, AWMF-Registernummer: 32-045OL. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft DK, AWMF) S3-Leitlinie Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge maligner Ovarialtumoren, Langversion 3.01 (Konsultationsfassung), AWMF-Registernummer: 032/035OL. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Ovarian cancers: evolving paradigms in research and care. 2016. 10.17226/21841. [PubMed]

- 10.Metcalfe Kelly, Lynch Henry T., Ghadirian Parviz, Tung Nadine, Olivotto Ivo, Warner Ellen, Olopade Olufunmilayo I., Eisen Andrea, Weber Barbara, McLennan Jane, Sun Ping, Foulkes William D., Narod Steven A. Contralateral Breast Cancer inBRCA1andBRCA2Mutation Carriers. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(12):2328–2335. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.AGO Breast Committee. Diagnosis and Treatmentof Patients with early and advanced Breast Cancer. Guidelines Breast Version 2019.1. https://www.ago-online.de/fileadmin/downloads/leitlinien/mamma/2019-03/EN/Updated_Guidelines_2019.pdf. Accessed 6 June 2019.

- 12.Peplonska Beata, Bukowska Agnieszka, Wieczorek Edyta, Przybek Monika, Zienolddiny Shanbeh, Reszka Edyta. Rotating night work, lifestyle factors, obesity and promoter methylation in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes among nurses and midwives. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(6):e0178792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grill Sabine, Yahiaoui-Doktor Maryam, Dukatz Ricarda, Lammert Jacqueline, Ullrich Mirjam, Engel Christoph, Pfeifer Katharina, Basrai Maryam, Siniatchkin Michael, Schmidt Thorsten, Weisser Burkhard, Rhiem Kerstin, Ditsch Nina, Schmutzler Rita, Bischoff Stephan C., Halle Martin, Kiechle Marion. Smoking and physical inactivity increase cancer prevalence in BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 mutation carriers: results from a retrospective observational analysis. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2017;296(6):1135–1144. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4546-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration. What are patient decision aids? 2017. http://ipdas.ohri.ca/what.html. Accessed 4 Feb 2019.

- 15.Stacey D, Legare F, Col NF, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Eden KB, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014. 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.O'Connor Annette M. Validation of a Decisional Conflict Scale. Medical Decision Making. 1995;15(1):25–30. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stacey D, Legare F, Lewis K, Barry MJ, Bennett CL, Eden KB, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017. 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Moher David, Liberati Alessandro, Tetzlaff Jennifer, Altman Douglas G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.IPDAS Collaboration . IPDAS 2005: criteria for judging the quality of patient decision aids. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins J, Altman D, Sterne J. Part 2, chapter 8: assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: JPT H, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, Savovic J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016. 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Armstrong Katrina, Weber Barbara, Ubel Peter A., Peters Nikki, Holmes John, Schwartz J. Sanford. Individualized Survival Curves Improve Satisfaction With Cancer Risk Management Decisions in Women WithBRCA1/2Mutations. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(36):9319–9328. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz Marc D., Valdimarsdottir Heiddis B., DeMarco Tiffani A., Peshkin Beth N., Lawrence William, Rispoli Jessica, Brown Karen, Isaacs Claudine, O'Neill Suzanne, Shelby Rebecca, Grumet Sherry C., McGovern Margaret M., Garnett Sarah, Bremer Heather, Leaman Suzanne, O'Mara Kathryn, Kelleher Sarah, Komaridis Kathryn. Randomized trial of a decision aid for BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers: Impact on measures of decision making and satisfaction. Health Psychology. 2009;28(1):11–19. doi: 10.1037/a0013147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hooker Gillian W., Leventhal Kara-Grace, DeMarco Tiffani, Peshkin Beth N., Finch Clinton, Wahl Erica, Joines Jessica Rispoli, Brown Karen, Valdimarsdottir Heiddis, Schwartz Marc D. Longitudinal Changes in Patient Distress following Interactive Decision Aid Use among BRCA1/2 Carriers. Medical Decision Making. 2010;31(3):412–421. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10381283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metcalfe Kelly A., Dennis Cindy-Lee, Poll Aletta, Armel Susan, Demsky Rochelle, Carlsson Lindsay, Nanda Sonia, Kiss Alexander, Narod Steven A. Effect of decision aid for breast cancer prevention on decisional conflict in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation: a multisite, randomized, controlled trial. Genetics in Medicine. 2016;19(3):330–336. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Roosmalen M S, Stalmeier P F M, Verhoef L C G, Hoekstra-Weebers J E H M, Oosterwijk J C, Hoogerbrugge N, Moog U, van Daal W A J. Randomised trial of a decision aid and its timing for women being tested for a BRCA1/2 mutation. British Journal of Cancer. 2004;90(2):333–342. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metcalfe KA, Poll A, O’Connor A, Gershman S, Armel S, Finch A, Demsky R, Rosen B, Narod SA. Development and testing of a decision aid for breast cancer prevention for women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Clinical Genetics. 2007;72(3):208–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knapp Thomas R. Why Is the One-Group Pretest–Posttest Design Still Used? Clinical Nursing Research. 2016;25(5):467–472. doi: 10.1177/1054773816666280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oxford University Press . One-group pretest-posttest design. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clouston SAP, Manganello JA, Richards M. A life course approach to health literacy: the role of gender, educational attainment and lifetime cognitive capability. Age Ageing. 2017. 10.1093/ageing/afw229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Kutner MGE, Jin Y, Paulsen C. The health literacy of America’s adults: results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson Heidi D., Pappas Miranda, Zakher Bernadette, Mitchell Jennifer Priest, Okinaka-Hu Leila, Fu Rongwei. Risk Assessment, Genetic Counseling, and Genetic Testing for BRCA-Related Cancer in Women: A Systematic Review to Update the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014;160(4):255–266. doi: 10.7326/M13-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butow PN, Lobb EA, Meiser B, Barratt A, Tucker KM. Psychological outcomes and risk perception after genetic testing and counselling in breast cancer: a systematic review. Med J Aust. 2003;178:2. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howard AF, Bottorff JL, Balneaves LG, Kim-Sing C. Women’s constructions of the ‘right time’ to consider decisions about risk-reducing mastectomy and risk-reducing oophorectomy. BMC Womens Health. 2010. 10.1186/1472-6874-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Evans D. G. R., Lalloo F., Ashcroft L., Shenton A., Clancy T., Baildam A. D., Brain A., Hopwood P., Howell A. Uptake of Risk-Reducing Surgery in Unaffected Women at High Risk of Breast and Ovarian Cancer Is Risk, Age, and Time Dependent. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2009;18(8):2318–2324. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradbury Angela R, Ibe Comfort N, Dignam James J, Cummings Shelly A, Verp Marion, White Melody A, Artioli Grazia, Dudlicek Laura, Olopade Olufunmilayo I. Uptake and timing of bilateral prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Genetics in Medicine. 2008;10(3):161–166. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318163487d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Full search strategy for each database. (DOCX 17 kb)

Quality of randomized controlled trials / Rationale. (XLSX 15 kb)

Quality of pretest-posttest study / Rationale. (XLSX 14 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.