Abstract

Place cells are hippocampal neurons whose discharge is strongly related to a rat's location in its environment. The existence of place cells has led to the proposal that they are part of an integrated neural system dedicated to spatial navigation. To further understand the relationships between place cell firing and spatial problem solving, we examined the discharge of CA1 and CA3 place cells as rats were exposed to a shortcut in a runway maze. On specific sessions, a wall section of the maze was removed so as to open a shorter novel route within the otherwise familiar maze. We found that the discharge of both CA1 and CA3 cells was strongly affected in the vicinity of the shortcut region but was much less affected farther away. In addition, CA3 fields away from the shortcut were more altered than CA1 fields. Thus, place cell firing appears to reflect more than just the animal's spatial location and may provide additional information about possible motions, or routes, within the environment. This kinematic representation appears to be spatially more extended in CA3 than in CA1, suggesting interesting computational differences between the two subregions.

Keywords: hippocampus, unit recordings, place cells, spatial processing, rat, spatial cognition

Introduction

Hippocampal place cells discharge strongly when the animal is in a cell-specific, stable region called its “firing field” and are usually silent elsewhere in the environment (O'Keefe and Dostrovsky, 1971). The ability of place cells to signal the animal's location is strong evidence for the mapping theory in which the hippocampus provides the neural substrate for a spatial representation of the animal's current environment (O'Keefe and Nadel, 1978). Supporting this hypothesis, there is clear evidence that the hippocampus is essential for successful navigation (Poucet and Benhamou, 1997). Furthermore, previous research suggests both that the behavior of the animal influences place cell activity (Markus et al., 1995; Gothard et al., 1996) and that the spatial information carried by place cells is used by the rat during navigation (O'Keefe and Speakman, 1987; Lenck-Santini et al., 2001, 2005).

The nature of the relationship between hippocampal place cell activity and the animal's spatial behavior is still a matter of debate, however. One current issue is whether place cell firing reflects just the animal's location or whether it also includes more extensive information about the environment, such as its structure. According to some models, a major function of the hippocampus is the coding of transitions between internal states, thus allowing prediction of the next state from the current state (Gaussier et al., 2002). In particular, place cell activity is deemed essential for coding the sequence of spatiotemporal events (including places) experienced by the rat (Agster et al., 2002; Fortin et al., 2002; Bower et al., 2005; Dragoi and Buzsáki, 2006). Thus, active place cells could provide information about future locations that may be reached predictably from the rat's current location. Changes in the structure of the environment that affect possible paths between one location and another would, therefore, be reflected in hippocampal place cell activity.

Previous work exploring the effects of putting an extended planar barrier into an open area revealed that when such a barrier bisects a cell's firing field, the discharge of the cell is often suppressed (Muller and Kubie, 1987). This effect appears to support the idea that the hippocampus represents changes in the constraints imposed by the local structure of the environment on the animal's movement (Poucet, 1993; Muller et al., 1996). The effects are local because the rat's movements remain unconstrained at points away from the barrier. Nevertheless, local changes in place field activity could equally reflect place cell sensitivity to the local sensory cues associated with the barrier itself (Rivard et al., 2004) (see also Hetherington and Shapiro, 1997). In search of a resolution to this ambiguity, it is of interest to examine the activity of place cells in a highly constrained environment, such as a maze, in which locations are associated with constrained paths that lead to distant and possibly visually obscured barriers. If manipulation of a barrier affects the firing of cells whose place fields are located “far” from the barrier, a purely sensory interpretation of hippocampal responses to the manipulation becomes insufficient.

In the present study, we recorded CA1 and CA3 place cells while rats were given the opportunity to take a shortcut in a highly familiar maze, thus inducing a change in the structure of the environment. Shortcutting reflects the flexibility of representation-based behavior, and we asked whether this flexibility is associated with changes in place cell firing in parts of the apparatus either close to the shortcut region or away from it.

Materials and Methods

Subjects.

Nine naive Long–Evans black hooded male rats (R. Janvier) weighing 300–350 g were housed one per cage at 20 ± 2°C, under natural lighting conditions. They had ad libitum access to water and were food deprived to 85% of ad libitum body weight. All procedures complied with both European and French institutional guidelines.

Apparatus.

The apparatus was a gray square-shaped plastic enclosure (80 cm on each side, 30 cm high). The maze was made by setting out three walls within the enclosure so as to define four connected corridors (20 × 80 cm) that together formed an M-shaped runway (Fig. 1, left). Each inner wall (60 cm long, 30 cm high) was made of three parts in gray opaque plastic (each part being 20 cm long), which were individually removable. The wooden floor was painted flat black. The apparatus was at the center of an evenly lit area surrounded by numerous distal visual cues placed in the room. A video camera and radio tuned to an FM station were fixed to the ceiling above the apparatus. A remote-controlled food dispenser was attached to the walls at each end of the M-shaped runway, delivering one 20 mg food pellet onto the apparatus floor each time it was activated. The unit recording system, TV monitor, and equipment for controlling the food dispensers was located in an adjacent room.

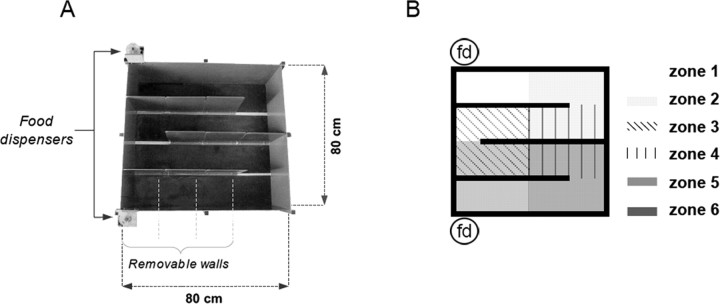

Figure 1.

A photograph of the maze and a schematic representation of the six zones used for calculating field similarity scores. A, B, Two food dispensers (fd) at the ends of the M-shaped runway were remotely controlled to keep the rat reliably running back and forth in the maze. Each inner maze wall was made of independent sections that could be separately removed. The six zones used for analyses of field similarity were defined so that analyses could be conducted whatever the field location was within the maze.

Behavioral procedures.

After 1 week of daily handling and 10 habituation sessions (5 min each) in the apparatus, rats were individually trained to commute back and forth between the two ends of the M-shaped runway. To this aim, the rat was introduced into the maze at one end and simply required to move to the other end. A single 20 mg food pellet was delivered whenever the rat visited one end of the runway after it had earned a reward at the other end. Each animal was trained in 16 min daily sessions for 4 weeks. Electrodes were implanted once the rat could consistently perform 50 correct runs between the two ends of the runway in each session.

Electrode implantation.

After behavioral training, a driveable bundle of 16 microwire electrodes was implanted surgically under sterile conditions and general anesthesia (ketamine/xylazine, 0.88 ml/kg). The electrodes were made of 25 μm nichrome wire and formed a bundle threaded through a piece of stainless steel tubing (Kubie, 1984). Each wire was attached to a pin on the outside of a rectangular connector. The tubing was attached to the center pin of the connector and served as the animal ground as well as a guide for microwires. The connector, tubing, and wires could be moved down through the hippocampus by turning drive screw assemblies cemented to the skull. The tips of the electrode bundle were implanted above the dorsal hippocampus (3.8 mm posterior, 3.0 mm lateral, and either 1.5 mm dorsoventral to dura for CA1 recordings or 2.8 mm dorsoventral to dura for CA3 recordings) (Paxinos and Watson, 2005). As a postoperative treatment rats received an injection of antibiotic (Clamoxil, 0.05 ml) and of analgesic (Tolfedine, 0.04 ml).

At the completion of the experiment, animals were killed with a lethal dose of pentobarbital. Just before death, positive current (15 μA for 30 s) was passed through one microwire to deposit iron that could be visualized after reaction with potassium ferrocyanide (Prussian blue). Then, rats were perfused intracardially with 0.9% saline followed by 4% formalin. The brains were removed and stored for 1 d in 3% ferrocyanide. Later, 25-μm-thick coronal sections were taken. Every fifth section was stained with cresyl violet for verification of electrode placements.

Recording methods.

Beginning 1 week after surgery, activity from each microwire was screened daily while the rat underwent additional training in the M-shaped runway. If no waveform of sufficient amplitude was found, the electrodes were lowered 25–50 μm. A period of several hours (usually 24 h) elapsed between successive screening sessions conducted in the same rat so as to guarantee electrode stability. Recordings were made only if the rat performance was adequate (i.e., at least three correct runs per minute). Ideally, recorded cells had fields distributed over different parts of the maze. Once a set of units was isolated, it was recorded for three 16 min sessions according to the testing protocol described below. Screening and recording were performed with a cable attached at one end to a commutator that allowed the rat to move ad libitum. The other end of the cable was connected to the rat headstage, which contained a field effect transistor amplifier for each wire. The signals from each electrode wire were further amplified (gain, 10,000), bandpass filtered (0.3–10 kHz), digitized (32 kHz), and stored by a Datawave Discovery acquisition system (DataWave Technologies). A light-emitting diode (LED) attached to the headstage assembly, 1 cm above the head and 1 cm behind the headstage, provided the position of the rat's head. The LED was imaged using a CCD camera fixed to the ceiling above the maze, and its position was tracked at 50 Hz with a TV-based digital spot-follower. Initially, LED position was located on a grid of 256 × 256 square pixels. However, this resolution was reduced in analysis to 32 × 32. Final pixel dimension was 45 mm.

Testing protocol.

Once a cell, or set of cells, was judged suitable for recording, it was recorded for three successive 16 min sessions. Session 1 (standard 1) was conducted while the rat performed the task with the apparatus in the standard configuration used during training. At the end of session 1, the rat was placed in a nearby waiting box with available water, while it was still connected to the recording system. During this time, the experimenter cleaned the apparatus floor and walls with water and removed a part of an inner wall, thus generating a shortcut. Removal was done out of the current rat's visual field. The rat was then introduced into the maze at the maze end farthest away from the removed wall. Session 2 (shortcut) was then conducted with the rat running the reconfigured maze for 16 min. At the end of session 2, the rat was placed in the waiting box with water available while the experimenter cleaned the apparatus and replaced the wall section that had been removed in session 2. Session 3 (standard 2) was conducted with the maze in its standard configuration. The purpose of this last standard session was to check that, whatever the changes in cell firing observed during session 2, we could ensure that the same cells had been recorded during the first two sessions by restoring the initial firing patterns. This protocol was repeated for each rat whenever a new cell or set of cells was isolated. Removing different wall sections generated six different possible shortcuts in the maze. Rats were randomly subjected to each possible shortcut across testing. Finally, the same protocol was used in a control condition, with the notable exception that during session 2 of the control condition, the opaque wall section was substituted with a transparent plastic wall instead of being removed as during regular shortcut sessions.

Unit discrimination.

Cells selected for analysis had to be well discriminated complex-spike cells with clear location-specific firing in at least one region of the environment. Moreover, because our purpose was to measure changes in the same cell across different manipulations, cells that were lost before the session series was completed, or whose waveforms changed too much between two sessions, were discarded from further analysis. The first step in off-line analysis was to define boundaries for waveform clusters. Candidate waveforms were discriminated based on characteristic features, including maximum and minimum spike voltage, spike amplitude (from peak to trough), time of occurrence of maximum and minimum spike voltages, spike duration, and voltage at several experimenter-defined points of the waveforms. Waveforms were then processed with a Plexon off-line sorter, which permits additional refinement of cluster boundaries and provides autocorrelation functions. Interspike interval histograms were built for each unit, and the whole unit was removed from analysis if the autocorrelogram revealed the existence of interspike intervals <2 ms (refractory period), which is inconsistent with good isolation. In a few specific cases, the quality of waveform isolation was further checked to discard the possibility that observed effects were caused by poor waveform discrimination. To do so, a waveform similarity score was obtained by calculating the gamma correlation between the mean waveform (defined as a series of 32 points for 1 ms) of a putative single cell that was recorded across distinct sessions. If the gamma correlation fell <0.95, the cell was discarded from the analyzed sample (gamma correlations calculated for mean waveform randomly shuffled across cells yield a mean value of 0.75). Once single units were well separated, autoscaled color-coded firing rate maps were created to visualize firing rate distributions (Muller et al., 1987). In such maps, pixels in which no spikes occurred during the whole session are displayed as yellow. The highest firing rate is coded as purple, and intermediate rates are shown as orange, red, green, and blue pixels, ranging from low to high. A firing field was defined as a set of at least six contiguous pixels with firing rate above grand mean rate. To allow comparisons among positional firing distributions across several sessions for a cell, the rate categories used for subsequent sessions were the same as for the first session.

Data presentation and analysis.

Our aim was to analyze the responses of individual firing fields to changes in maze structure induced by wall removals that allowed the animal to take shortcuts. Because many cells had more than one field in the M-runway, and because fields far from the removed wall and fields “near” the removed wall were differentially affected by the manipulation, the maze was subdivided into six equally sized and partially superimposed sectors, each centered on a given region of the maze that represented ∼25% of its total area (Fig. 1, right). The pixel coordinates, Xc and Yc, of field centroids were calculated according to the formula Xc = Σxiri/Σri and Yc = Σyiri/Σri, in which xi and yi are the positions of the ith pixel in the field, and ri is its firing rate (Fenton et al., 2000). Fields whose centroids in session 1 were in the same sector as the wall removed in session 2, and which touched that wall, were classified as near fields. Other fields were classified as far fields. The centroid was also used to measure route distance from field location to wall opening.

To estimate firing field similarity between two successive sessions, we computed a similarity score equal to the pixel-by-pixel correlation [Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient (rs)] between the positional rate distribution in the field sector for the first (standard) session and the superimposed positional rate distribution in the same sector for the second (shortcut) session. Because correlation coefficients are not normally distributed, similarity scores were converted into z-scores using the Fisher's z transformation. All statistical analyses were performed on the z-scores.

Similarity scores were separately calculated for near and far fields. For near fields, similarity scores were calculated using the sector containing the removed wall because, by definition, such fields are centered on this area. In contrast, far fields could extend across several sectors. Therefore, similarity scores for far fields were calculated by averaging, when necessary, the similarity scores for the sectors containing the field. No far field extended across more than two sectors. To estimate the number of similar and altered fields after wall removal, we used a cutoff method based on the similarity score, in which the chosen threshold discriminates fields that cannot be statistically shown to have some degree of similarity from those that can. Because sector size was 50 pixels on average, and because the calculated correlation treated each pixel as an independent sample, we considered that a correlation >0.33 reflected the level at which the firing fields displayed a minimum level of correlation at p < 0.02 (i.e., were similar). Conversely, correlations <0.33 were considered to reflect uncorrelated fields (i.e., altered fields). Using other correlation thresholds (0.28 for p < 0.05 and 0.36 for p < 0.01) altered the numbers of fields in each category but did not change the conclusions.

In addition to similarity scores, we examined the type of change exhibited by fields after wall removal. We distinguished two major types of field changes. The “rate remapping” category included fields whose firing rate was changed by >50% relative to initial level (either in a positive or negative way) but whose location and shape were mostly unchanged. The “field remapping” category included other types of changes, including cells that stopped firing or switched from silent to active across successive sessions and fields that shifted position by >20 cm (a wall unit) or whose visually assessed shape was dramatically altered.

Finally, behavioral performance was measured in several ways. First, we counted the number of rewards earned by the rat, which reflects the number of correct runs (i.e., alternate visits to each runway end) during all recording sessions to get an overall performance score. During shortcut sessions, we examined how many runs were necessary before the rat used the shortcut path for the first time. We also counted the number of runs in which the rat used the shortcut, to calculate the percentage of shortcutting (number of shortcut paths × 100/overall performance score).

Results

General characteristics of cell sample

The present analyses are based on the data obtained from nine rats tested in 75 complete sequences of three sessions: standard–shortcut–standard. Average performance in the M-runway maze was 46.1 ± 0.8 correct runs per session during the first standard session and did not vary significantly across successive sessions. In a vast majority of shortcut sessions (73 of 75, 97.3%) (i.e., when the wall section was removed during session 2), rats took the shortcut on the very first run from one runway end to the other. In the remaining two sessions, the rat took the shortcut on the second run through the maze. Furthermore, the within-session percentage of shortcutting was 90.8%, thus showing that, once discovered, the shortcut path was preferentially and consistently used by the rats.

From an initial pool of 359 recorded cells, 115 cells (CA1, n = 67; CA3, n = 48) were selected for further detailed analyses. Analyzed cells had to be complex-spike pyramidal cells with waveforms >100 μV in amplitude (baseline noise, ∼30 μV) that were repeatedly recorded across all three sessions of the recording sequence. Furthermore, they had to have a clear spatial firing pattern during the first standard session, which was restored during the last standard session. The above criteria excluded putative interneurons, silent or noisy pyramidal cells, and cells whose across-session firing was unreliable to the extent that no significant conclusion could be drawn from their changes in activity. Because many analyzed cells had several fields in the maze (most usually two), the final number of fields used for analysis was 126 and 89 for CA1 and CA3, respectively. Field classification yielded 75 far and 51 near fields for CA1, and 54 far and 35 near fields for CA3.

Field changes during the shortcut session

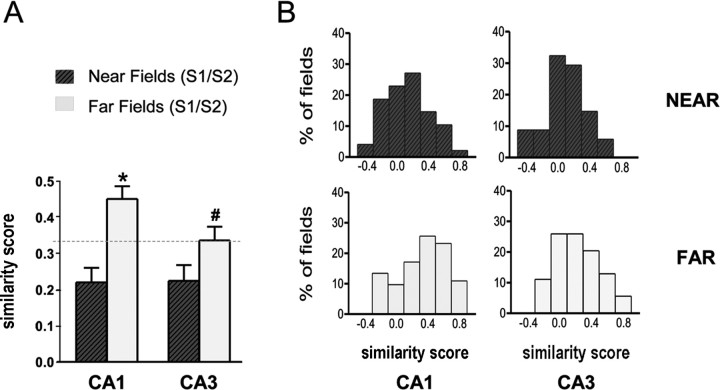

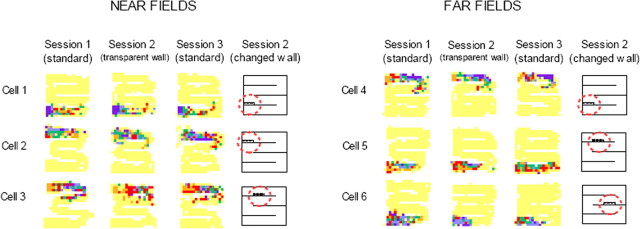

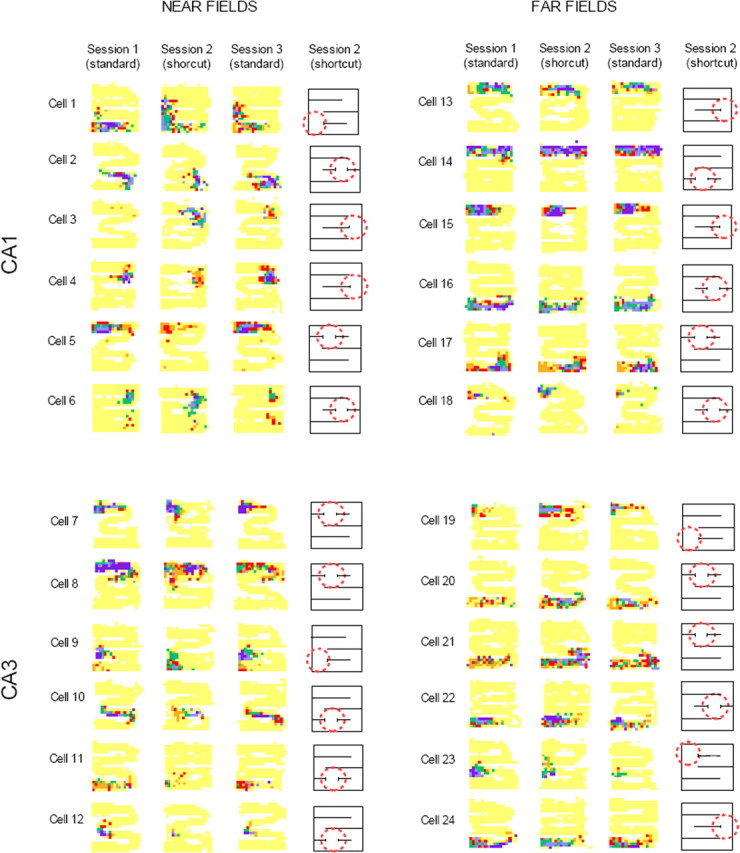

Wall removal during session 2 was associated with noticeable changes in place cell activity. Although in no instance was a complete field remapping observed, selective changes were found in most cases. In general, near fields (close to wall opening) were strongly affected, whereas far fields (away from wall opening) were affected mostly for CA3 cells. Figure 2 shows representative examples of field changes after wall removal. Figure 3 (left) shows mean similarity scores (see Materials and Methods) between sessions 1 (standard) and 2 (shortcut), separately for near fields and far fields in each hippocampal region. Figure 3 (right) shows corresponding distributions. The dashed line is set at 0.33 (see Materials and Methods) to provide a reference similarity score against which it is possible to judge the magnitude of effects induced by wall removal. Based on this reference, 67 and 74% of near fields, but only 29 and 54% of far fields, were affected by wall removal (i.e., rs < 0.33) in CA1 and CA3, respectively, therefore suggesting that wall removal had a greater impact on near fields than on far fields. In both CA1 and CA3 cells, low similarity scores indicate strong changes in near fields. In general, far fields were affected to a much lesser extent, but an interesting difference emerged between CA1 and CA3 cells, with the latter being more altered than the former.

Figure 2.

Firing rate maps for place cells across the three sessions of a recording sequence. In all maps, yellow indicates no firing, and purple indicates maximum firing (orange, red, green, and blue indicate intermediate firing rates from low to high). The same color code was used for all three sessions of a recording sequence. For each recording sequence, a schematic map of the maze is provided, showing shortcut location (dashed red circle). Near fields were more strongly affected than far fields. In addition, CA3 far fields were more affected than CA1 far fields.

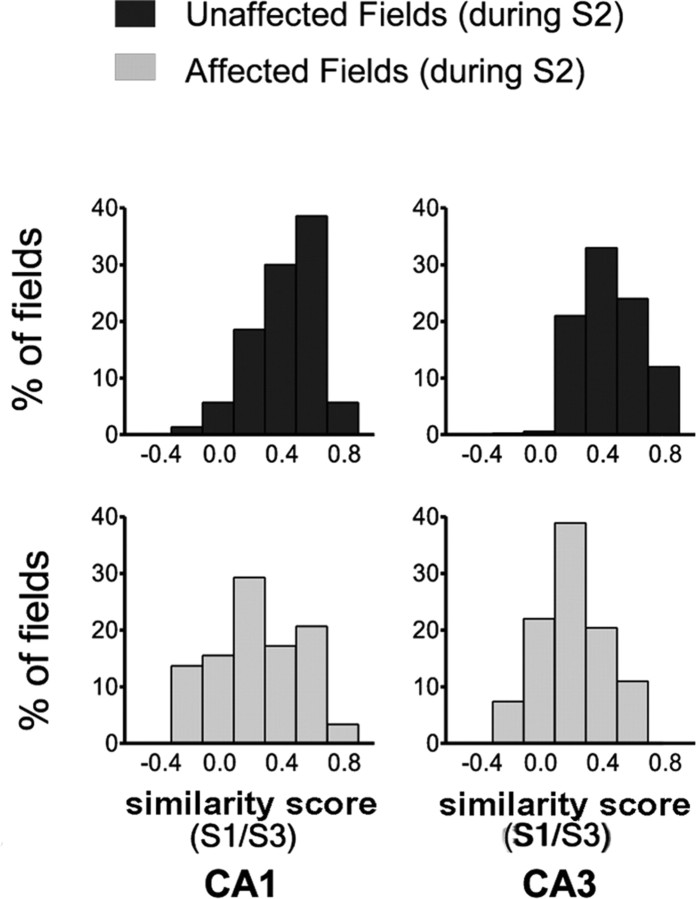

Figure 3.

Similarity scores after wall removal. A, Mean similarity scores (±SEM) for near and far fields in CA1 and CA3 cells. Correlation coefficients (rs) between the firing rate maps obtained for standard and shortcut sessions were used as an index of similarity between the spatial firing patterns. The dashed line is set at 0.33 to illustrate the threshold beyond which fields may be judged to be altered after wall removal. *p < 0.0001 compared with CA1 near fields; #p < 0.05 compared with CA1 far fields. S1, Session 1; S2, session 2. B, Distribution of similarity scores for near (top histograms) and far (bottom histograms) fields in CA1 (left) and CA3 (right) cells. Most near fields were affected by wall removal, as shown by the leftward-shifted distribution of similarity scores. In contrast, CA1 far fields were relatively preserved compared with CA3 far fields, as shown by a rightward bias in the distribution of similarity scores.

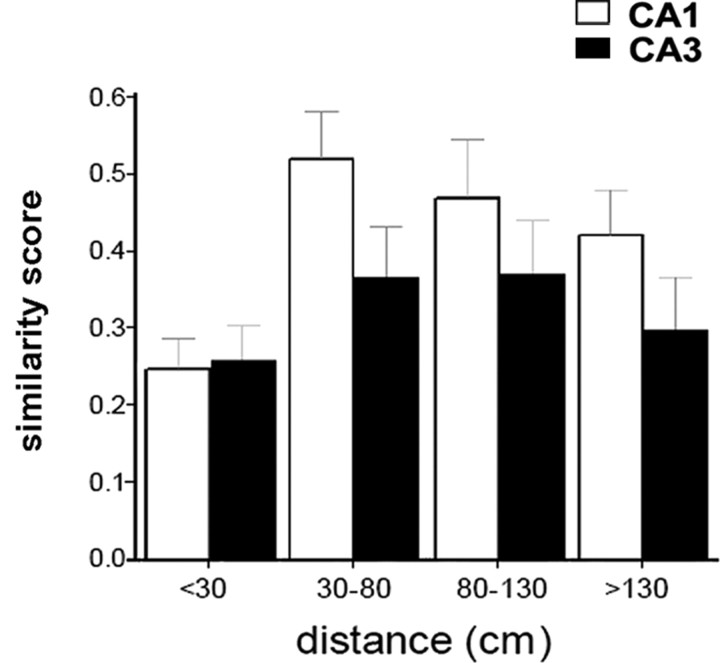

A two-way ANOVA (with anatomical subregion and distance as the two factors) was conducted on similarity scores (all statistics performed on z-scores), revealing a main effect of distance (F(1, 211) = 18.13; p < 0.0001) but no effect of subregion (F(1, 211) = 2.03, NS) and no interaction (F(1,211) = 1.66, NS). Planned comparisons revealed that similarity scores were significantly lower for near fields than for far fields in CA1 cells (t(124) = 4.49; p < 0.0001) but not in CA3 (t(87) = 2.45, NS). Furthermore, similarity scores for far fields (t(127) = 2.24; p < 0.05), but not for near fields (t(84) = 0.08, NS), were lower in CA3 compared with CA1. A similar pattern emerged from a Kolmogorov–Smirnov analysis of the distributions of similarity scores shown in Figure 3. Significant differences were found between near fields and far fields in CA1 (p < 0.001) but not in CA3. Furthermore, a significant difference was found between CA1 and CA3 for far fields (p < 0.01) but not for near fields. The greater impact of wall removal on CA3 far fields was further confirmed by plotting similarity scores as a function of route distance between field location and wall opening (Fig. 4). In such histograms, two clusters were clearly discernable for both CA1 and CA3 fields, reflecting low similarity scores for small distances (<30 cm) and higher similarity scores for larger distances (>30 cm). However, the CA3 cluster for distances >30 cm was consistently below the CA1 cluster, as confirmed by a two-way ANOVA that yielded a significant main effect of subregion (F(1, 101) = 4.61; p < 0.05), but no significant effect of distance (F(2, 101) = 0.74, NS) and no interaction between these two factors (F(2, 101) = 0.10, NS). Because fields in undersampled areas (i.e., not explored by the rat because of the shortcut) were discarded from this analysis, most fields in the 30–80 cm distance range and all of the more distant fields were in locations out of perceptual range of the wall removal (i.e., around a corner).

Figure 4.

Distribution of similarity scores (rs) as a function of field distance to the removed wall. With the exception of near fields (<30 cm), similarity scores were consistently lower for CA3 than for CA1.

Although the difference between CA1 and CA3 far fields may simply reflect a greater instability of CA3 cells rather than an effect of wall manipulation, this possibility is unlikely. First, within-session stability, obtained by breaking down standard sessions into two halves, was not different in CA1 and CA3 cells (CA1, rs = 0.51 ± 0.05; CA3, rs = 0.46 ± 0.03, t(198) = 1.55, NS). Second, similarity scores between standard sessions for far fields unaffected by the shortcut were not statistically different (CA1, rs = 0.53 ± 0.03; CA3, rs = 0.44 ± 0.05, t(75) = 1.11, NS). The overall similar stability of CA1 and CA3 fields under constant conditions strengthens the notion that the greater sensitivity of CA3 fields to wall manipulations was caused by the structural changes in the environment.

Visual inspection of qualitative changes affecting individual fields (see Materials and Methods) revealed that near fields were more affected by wall removal than far fields in both CA1 and CA3. Approximately 70% of near fields affected by the shortcut endured drastic changes, indicative of field remapping (Fig. 2, cells 1–3 and 7–10). For the remaining 30% of the near fields, the main change was a rate remapping (i.e., a significant decrease or increase in firing rate only) (Fig. 2, cells 4–6 and 11–12). The picture was the opposite for far fields in which the main modifications concerned firing rate (80%) (Fig. 2, cells 18–22). The difference in the distributions of rate remapping and field remapping for near and far fields was highly significant (χ2 = 41.5; df = 1; p ≪ 0.001), suggesting qualitatively different effects of the shortcut on near and far fields. Finally, we asked whether field changes were immediate or delayed during shortcut sessions. We examined this issue for near fields that underwent strong changes as a result of wall removal so that it was possible to pinpoint the time of change by replaying the recording session. In all inspected cases (CA1, n = 45; CA3, n = 30), we found that field changes occurred on the rat's first encounter with the wall opening during shortcut sessions.

Analysis of field changes in relation to behavior

Because far fields were, by definition, away from the wall opening in which the path structure was strongly altered, the modifications they endured were unlikely to result from changes in the path taken by the rat in the field location. In contrast, variations in immediate behavior could possibly explain the changes observed for near fields. As an attempt to disentangle the contribution of kinematic parameters to near field modifications, we separately computed similarity scores for the standard and shortcut sessions according to whether the rat was moving leftward or rightward. This analysis was motivated by the possibility that low similarity scores for near fields could result from the interaction between a gross change in the direction followed by the rat in the shortcut region and potential cell's directional selectivity. Even when computed separately for each motion direction, however, similarity scores remained very low (leftward, rs = 0.097 ± 0.029; rightward, rs = 0.050 ± 0.024) and comparable with direction-independent similarity scores (rs = 0.086 ± 0.022, n = 60; none of the paired comparisons yielded a significant difference). In other words, near fields in the standard and shortcut sessions were different for comparable motion directions. In a subsequent qualitative analysis, we plotted all trajectories and superimposed spike locations. We then looked for path segments that overlapped during both standard and shortcut sessions (nonoverlapping locations are discarded from similarity score analyses). We found that firing was different, although path segments were comparable (Fig. 5). Finally, we selected shortcut sessions in which the animal made a significant number of errors (i.e., took the detour instead of the shortcut in >15% of the trials). Inspection of firing during erroneous paths again revealed that the firing patterns differed in the standard and shortcut sessions, although the paths were almost similar in the two sessions (Fig. 5). This observation was confirmed by a quantitative analysis of field similarity in the maze region containing the erroneous paths, which yielded low similarity scores (rs = 0.116 ± 0.082; n = 18). In sum, remapping in near fields appears to reflect more than just the direct behavioral effects of the shortcut. That far fields were also altered (at least in CA3), despite the distance from the shortcut location, provides additional support to the notion that the observed changes in cell firing result from an altered representation of the environment rather than from mere sensory or locomotor changes.

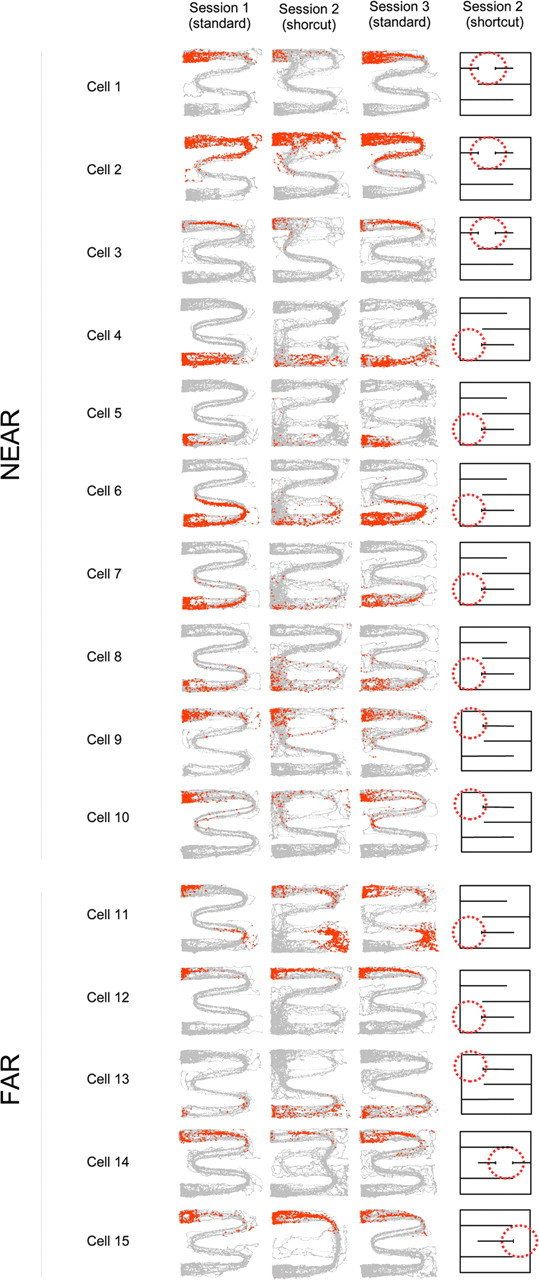

Figure 5.

Examples of firing field alterations during shortcut behavior. Each row displays the firing of one cell across the three sessions of a recording sequence in the three leftmost columns (cells 1–10 have near fields, whereas cells 11–15 have far fields). Each panel shows all the paths for the recording session, with red dots indicating the spikes from one neuron. The schematic map of the maze for each recording sequence (rightmost column) shows shortcut location (dashed red circle). Marked changes in firing can be observed in session 2 (shortcut), although paths in the standard and shortcut sessions are often overlapping. This is particularly evident when the rat erroneously takes the long path instead of the shortcut. Although firing patterns are often similar in the two standard sessions bracketing the shortcut session, there is occasionally evidence for an influence of the shortcut on the last standard session. This hysteresis effect is apparent, although paths look very similar in the two standard sessions (e.g., cells 11 and 13).

Field changes in response to a transparent wall

Because alterations of near fields during shortcut sessions may result from the visual change induced by wall removal, the procedure for session 2 was changed in a few control experiments (n = 17), so that, instead of removing an inner wall, thereby opening a shortcut, a section of the opaque plastic wall was replaced with an equivalent section in transparent plastic material. The visual change brought about by the replacement was nearly identical to the visual change experienced by the rats during regular shortcut sessions, but the maze spatial structure was left unchanged by this manipulation. We calculated the mean similarity scores between sessions 1 (standard) and 2 (transparent wall) separately for near fields (close to the replaced wall section) and far fields (Fig. 6). Compared with the reference similarity score of 0.33 (see Material and Methods), it is clear that wall replacement had little impact on either near fields (rs = 0.492 ± 0.064; n = 13) or far fields (rs = 0.454 ± 0.060; n = 23). The lack of effect of a transparent wall was not caused by the rat failing to notice the change and to direct its attention toward it, because exploration measured by dwelling time in the zone of the transparent wall during the first minute of session 2 (with the transparent wall) was significantly increased compared with the mean dwelling time in other regions (t(16) = 2.74; p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Firing rate maps for representative place cells recorded in the control condition. The color code is as in Figure 2. For each recording sequence, a schematic map of the maze is provided showing the location in the maze in which an opaque maze section was substituted with a transparent section. None of the fields were significantly affected by such substitution.

Evidence for hysteresis during the final session

Fields that were unaffected by wall removal during shortcut sessions had large similarity scores between the two standard sessions that bracketed the shortcut session (CA1, 70 of 126, rs = 0.54 ± 0.03; CA3, 33 of 88, rs = 0.49 ± 0.04). In contrast, fields that did change during shortcut sessions were not all perfectly restored during the subsequent standard session. A few fields (CA1, n = 11 of 56, 20%; CA3, n = 15 of 55, 27%) that were altered in shortcut sessions were highly similar in the two standard sessions (i.e., had an rs > 0.33; distributions of similarity scores shown in Fig. 7). For these fields, similarity scores between standard sessions were large (CA1, rs = 0.64 ± 0.05; CA3, rs = 0.53 ± 0.04) and much greater than the similarity scores between the first standard and shortcut sessions (CA1, rs = 0.09 ± 0.04, t(10) = 11.89, p ≪ 0.0001; CA3, rs = 0.13 ± 0.05, t(14) = 8.72, p ≪ 0.0001). Although the remaining fields (CA1, n = 45 of 56, 80%; CA3, n = 40 of 55, 73%) bore some resemblance in the two standard sessions, the similarity scores were smaller than 0.33 and significantly reduced compared with unaltered fields (CA1, rs = 0.27 ± 0.04, t(113) = 5.43, p < 0.0001; CA3, rs = 0.22 ± 0.03, t(71) = 5.32, p < 0.0001). Furthermore, for these fields the similarity scores between the first standard session and the shortcut session (CA1, rs = 0.07 ± 0.23; CA3, rs = 0.11 ± 0.02) were smaller than between the shortcut session and the last standard session (CA1, rs = 0.26 ± 0.04, t(44) = 4.35, p < 0.0001; CA3, rs = 0.26 ± 0.04, t(39) = 3.29, p < 0.01). Because the rat was not disconnected between sessions, electrode drift was unlikely to explain these effects. Furthermore, waveform similarity between the two standard sessions (see Material and Methods) was very high for both changed (0.99 ± 0.001) and unchanged (0.99 ± 0.003) fields. Last, we computed a coefficient of variation (cv) for each cell's waveforms, which revealed that the discrimination parameters used for waveform isolation were as stringent for changed fields (cv = 0.40 ± 0.02) as they were for unchanged fields (cv = 0.37 ± 0.03) in the last standard session (t = 0.67; NS). Given the above evidence that cell waveforms were unchanged, we conclude that the observed pattern of field changes across standard sessions is highly suggestive of a hysteresis effect. Interestingly, CA3 far fields were as likely to be impacted by such hysteresis as CA3 near fields, as shown by comparable similarity scores between the two standard sessions (0.29 ± 0.03 and 0.32 ± 0.05, respectively; t(53) = 0.58, NS). In short, fields in the last standard session were influenced by the previously experienced shortcut in the immediately preceding session (Fig. 2, cells 1, 3, 8, and 19). Because no obvious difference in the paths taken by the rats during the two standard sessions was observed (Fig. 5), we suggest that this hysteresis effect is a direct consequence of the field changes induced by the shortcut session.

Figure 7.

Distribution of similarity scores during standard sessions. Although the fields that were unaffected during the shortcut session were usually highly similar in the two standard sessions that bracketed the shortcut session (top histograms), some of the fields affected by the shortcut were not completely restored in the last standard session, as shown by the leftward-shifted distribution of similarity scores (bottom histograms).

Discussion

We recorded CA1 and CA3 hippocampal place cells while rats explored a complex maze for food located at the two ends of the maze. On specific sessions, a wall section of the maze was removed so as to open a shorter novel route between the maze ends in an otherwise highly familiar environment. On these sessions, rats immediately and consistently used the newly available shortcut. Likewise, firing activity of both CA1 and CA3 cells was immediately and strongly affected in the vicinity of the shortcut region and much less so for maze parts away from it. Furthermore, CA3 firing fields far from the shortcut were much more altered than CA1 fields. Such sensitivity to newly available routes in the maze, especially when the new route appears at a distant site, indicates that place cell firing may reflect more than just the animal's spatial location and may provide additional information about the possible connections between places (Poucet, 1993).

Whereas both CA1 and CA3 cells were strongly affected for maze locations near the removed wall, CA3 cells were much more affected than CA1 cells for locations away from the shortcut region. Such selective effects were not totally unexpected for CA1 cells because, in previous experiments, barriers that were manipulated as rats explored an open space clearly influenced both the rat's trajectories and cell fields in the vicinity of the barrier without any significant and reliable effect on fields that were away from the barrier (Muller and Kubie, 1987; Rivard et al., 2004). Interestingly, such local effects were also observed in a different protocol in which rats commuted ad libitum between two connected boxes. On some occasions, one of the two boxes was substituted with a novel box. Although this change resulted in remapping in the changed box, most fields in CA1 did not remap in the unchanged box (Paz-Villagrán et al., 2004). In other words, changes in CA1 cell firing were local to the changed environment for most cells. The present results show that, in contrast to CA1 cells, firing of CA3 cells can be reliably altered even for fields away from the environmental change. The finding of both local (for CA1 and CA3 fields) and nonlocal changes (CA3 fields) indicates for the first time that maze structure may be encoded by place cells and act as a contextual cue, indicating environmental state extending beyond altered locations.

Remarkably, the effects of wall removal on place cell firing fields did not appear to be purely perceptual or motor. First, purely perceptual (visual) effects would hardly explain the results of the control condition in which a wall section in the maze was substituted with an equivalent transparent wall. The visual change induced by such substitution strongly resembled that produced by wall removal, and clear behavioral evidence indicates that animals actually noticed the change because, on their first pass near the transparent wall, they stopped running through the maze to explore the new transparent wall. Despite its salience, however, this visual change did not induce any significant change in cell firing, thus showing that the effects of wall removal cannot be simply explained by visual detection of a modification. Nevertheless, it is possible that other sensory inputs, such as somatosensory and tactile inputs, may account for the changes local to the removed barrier. Unfortunately, it is difficult to identify the precise cause of field changes resulting from local modifications of the animal's environment, because these changes are generally multimodal. However, that far fields (especially in CA3) were modified in the absence of a local change provides strong additional support to the notion that the observed modifications in place cell firing were not just reflecting perceptual changes, but may have resulted from an altered representation of the maze structure and the resulting modifications in possible motions.

A detailed analysis of field changes in relation to behavior also suggested that such changes reflected more than just the direct behavioral (motor) effects of the shortcut. This is obvious for far fields, which, in some cases, were clearly altered although the rats' locomotor patterns were mostly unchanged in their vicinity. The situation is more complicated for fields close to the shortcut location, which, in principle, could be influenced more directly by changes in immediate behavior. However, it is remarkable that clear modifications of near fields were observed even when the rats' trajectories were equated as much as possible, for example during erroneous paths. Finally, the signs of hysteresis observed across successive sessions were not compatible with purely motor effects of wall removal. Hysteresis was manifest during the last standard session in which lasting effects of shortcut exposure were observed. Such carry-over effects reflect the changes occurring during the immediately preceding shortcut session, making it unlikely that the effects of the shortcut on the hippocampal representation were strictly caused by a change in the rat's trajectory.

The modification of the initial place cell representation after exposure to the shortcut indicates that some information is stored intrinsically in the place cell network (Leutgeb et al., 2005). Interestingly, hysteresis was found for both CA1 and CA3 cells. Although this result was not entirely expected on the basis of previous reports showing greater hysteresis in CA3 than in CA1 ensemble activity (Leutgeb et al., 2005), there is evidence that CA1 cell firing can be influenced by recent history (Wills et al., 2005). Furthermore, this effect in the CA3 subregion is of special significance because only in CA3 were both near and far fields affected by the existence of a shortcut, therefore confirming greater internal consistency in CA3 than in CA1 (Lee et al., 2004a,b; Vazdarjanova and Guzowski, 2004) and suggesting more global encoding of maze structural properties in the former subregion. That CA3 far fields were altered in the long term also raises the puzzling possibility that the representations stored by the CA3 network may be both more sensitive to spatially remote changes in the environment and, paradoxically, less reversible after such changes. Presumably, extensive associative connections in CA3 would confer on this subregion the properties of an attractor-based neural network (Marr, 1971; Treves and Rolls, 1992). This network would be able to store flexibly a large number of spatial representations influenced by the rat's recent and remote experience with the varying structure of the maze (Samsonovich and McNaughton, 1997; Battaglia and Treves, 1998).

Our results are also relevant to the issue of how sequences of events may be represented by the rat hippocampus. Previous research has demonstrated that a sequence of places actively traversed by the rat may be later replayed either during sleep (Skaggs and McNaughton, 1996; Louie and Wilson, 2001; Lee and Wilson, 2002; O'Neill et al., 2008) or during pauses in the awake state (Foster and Wilson, 2006). Our recording protocol did not allow us to analyze sequential replay during either standard or shortcut sessions because the rat was not required to pause at the food dispenser. However, the sudden availability of a shortcut path in the maze clearly altered the sequences of locations traversed by the rat while commuting back and forth between the two maze ends. It is therefore possible that the changes in CA1 and CA3 firing reflect encoding of the new spatiotemporal sequence. Although near fields in CA1 were altered by the shortcut to a far greater extent than far fields, both near and far fields were clearly affected in CA3, again suggesting more global encoding in the former subregion. The question therefore arises as to how CA1 comes to reflect only local changes and therefore preserves a stable representation of unchanged maze parts, despite the dense projections from CA3 in which the overall representation is altered [see also Lee et al. (2004b) for a similar issue]. A plausible, yet speculative explanation might rely on the unique anatomical position of CA1, which receives both CA3 information and direct cortical sensory information relayed from entorhinal cortex (Witter and Amaral, 2004). In principle, such converging inputs in CA1 would allow a comparison of sensory information with stored information (Lee et al., 2004). That CA1 and CA3 firing can differ so much with respect to encoding of locations away from the shortcut region suggests that the direct entorhinal input overcomes, or rectifies, the information carried by the CA3 projections to result in CA1 discharge to reflect the actual structure of the maze. Noticeably, this conclusion is consistent with previous observations that CA1 firing can be preserved in the absence of CA3 input (McNaughton et al., 1989; Mizumori et al., 1989; Brun et al., 2002).

Our data, which emphasize different cell properties in CA1 and CA3, are in line with recent lesion evidence suggesting that the two subregions might serve different functions within the hippocampus (Rolls and Kesner, 2006). For example, CA3 has been demonstrated to be involved in rapid encoding of new information (Lee and Kesner, 2002, 2003; Nakazawa et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2004a), pattern completion (Gold and Kesner, 2005), and, more recently, pattern separation (Gilbert and Kesner, 2006). In contrast, CA1 is thought to be involved in sequence learning, long-term memory, and possibly spatial pattern completion (Rolls and Kesner, 2006; Renaudineau et al., 2007). Our results are consistent with at least some processes putatively supported by CA1 and CA3 subregions. Thus, stronger remapping in CA3 would be indicative of pattern separation that could be used to trigger rapid learning of novel maze structure. Conversely, more stable firing patterns in CA1 would reflect long-term memory of the maze, whereas remapped fields in the shortcut region could support memory encoding of the locally changed temporal sequence of locations.

Finally, several recent accounts of place cell firing consider location-specific discharge either to reflect encoding of spatial context (Jeffery et al., 2004) or to result from putative cortical inputs tuned to environmental boundaries a certain distance and direction from the rat (Hartley et al., 2000; Barry and Burgess, 2007). Although not incompatible with these theories, our data do not fit easily with their premises that strongly emphasize the role of currently experienced sensory cues (even though contextual cues may include nonsensory cues; Markus et al., 1995; Frank et al., 2000; Wood et al., 2000; Jeffery et al., 2004). Instead, our results indicate that, in addition to spatial locations defined by constellations of sensory cues, an important component of the place cell representation is determined by how these locations are connected with each other. Whether such coding of spatial connectivity is established on the basis of the motions that can be accomplished between places (McNaughton et al., 1996; Knierim et al., 1998), or of a more abstract representation of the sequence of places explored (Wood et al., 1999; Ferbinteanu and Shapiro, 2003), cannot be determined at present. Nevertheless, that the spatial coding accomplished by place cells goes beyond the rat's current location suggests that it contains the information required for the animal to compute optimal paths within the environment in a prospective manner (Ferbinteanu and Shapiro, 2003; Ainge et al., 2007). Extending this notion, a major function of the hippocampus might be the coding of transitions between states, whether spatial or nonspatial (Gaussier et al., 2002). Such transitions would thus allow for the building of associations between elements that are not necessarily contiguous in time and hence for the flexible use of memories needed to perform complex behaviors.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (B.P., E.S.), Ministère de l'Education Nationale (A.A., T.V.C.), and Agence Nationale de la Recherche (B.P., E.S.). We thank Brian G. Burton and several anonymous reviewers for their comments on a previous version of this manuscript, Dany Paleressompoulle for electronics and construction of the maze, Henriette Lucchessi for help in training the animals, and Paul de Saint Blanquat for help with the figures.

References

- Agster KL, Fortin NJ, Eichenbaum H. The hippocampus and disambiguation of overlapping sequences. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5760–5768. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05760.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainge JA, Tamosiunaite M, Woergoetter F, Dudchenko PA. Hippocampal CA1 place cells encode intended destination on a maze with multiple choice points. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9769–9779. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2011-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry C, Burgess N. Learning in a geometric model of place cell firing. Hippocampus. 2007;17:786–800. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia FP, Treves A. Attractor neural networks storing multiple space representations: a model for hippocampal place fields. Phys Rev E. 1998;58:7738–7753. [Google Scholar]

- Bower MR, Euston DR, McNaughton BL. Sequential-context-dependent hippocampal activity is not necessary to learn sequences with repeated elements. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1313–1323. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2901-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun VH, Otnass MK, Molden S, Steffenach HA, Witter MP, Moser MB, Moser EI. Place cells and place recognition maintained by direct entorhinal-hippocampal circuitry. Science. 2002;296:2243–2246. doi: 10.1126/science.1071089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragoi G, Buzsáki G. Temporal encoding of place sequences by hippocampal cell assemblies. Neuron. 2006;50:145–157. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton AA, Csizmadia G, Muller RU. Conjoint control of hippocampal place cell firing by two visual stimuli. I. The effects of moving the stimuli on firing field positions. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:191–209. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.2.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferbinteanu J, Shapiro ML. Prospective and retrospective memory coding in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2003;40:1227–1239. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00752-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin NJ, Agster KL, Eichenbaum HB. Critical role of the hippocampus in memory for sequences of events. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:458–462. doi: 10.1038/nn834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster DJ, Wilson MA. Reverse replay of behavioural sequences in hippocampal place cells during the awake state. Nature. 2006;440:680–683. doi: 10.1038/nature04587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank LM, Brown EN, Wilson M. Trajectory encoding in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. Neuron. 2000;27:169–178. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaussier P, Revel A, Banquet JP, Babeau V. From view cells and place cells to cognitive map learning: processing stages of the hippocampal system. Biol Cybern. 2002;86:15–28. doi: 10.1007/s004220100269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PE, Kesner RP. The role of dorsal CA3 hippocampal subregion in spatial working memory and pattern separation. Behav Brain Res. 2006;169:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold AE, Kesner RP. The role of the CA3 subregion of the dorsal hippocampus in spatial pattern completion in the rat. Hippocampus. 2005;15:808–814. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothard KM, Skaggs WE, Moore KM, McNaughton BL. Binding of hippocampal CA1 neural activity to multiple reference frames in a landmark-based navigation task. J Neurosci. 1996;16:823–835. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00823.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley T, Burgess N, Lever C, Cacucci F, O'Keefe J. Modeling place fields in terms of the cortical inputs to the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2000;10:369–379. doi: 10.1002/1098-1063(2000)10:4<369::AID-HIPO3>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington PA, Shapiro ML. Hippocampal place fields are altered by the removal of single visual cues in a distance-dependent manner. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111:20–34. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery KJ, Anderson MI, Hayman R, Chakraborty S. A proposed architecture for the neural representation of spatial context. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28:201–218. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knierim JJ, Kudrimoti HS, McNaughton BL. Interactions between idiothetic cues and external landmarks in the control of place cells and head direction cells. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:425–446. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubie JL. A driveable bundle of microwires for collecting single-unit data from freely moving rats. Physiol Behav. 1984;32:115–118. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(84)90080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AK, Wilson MA. Memory of sequential experience in the hippocampus during slow wave sleep. Neuron. 2002;36:1183–1194. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Kesner RP. Differential contribution of NMDA receptors in hippocampal subregions to spatial working memory. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:162–168. doi: 10.1038/nn790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Kesner RP. Differential roles of dorsal hippocampal subregions in spatial working memory with short versus intermediate delay. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:1044–1053. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.5.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Rao G, Knierim JJ. A double dissociation between hippocampal subfields: differential time time course of CA3 and CA1 place cells for processing changed environments. Neuron. 2004a;42:803–815. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Yoganarasimha D, Rao G, Knierim JJ. Comparison of population coherence of place cells in hippocampal subfields CA1 and CA3. Nature. 2004b;430:456–459. doi: 10.1038/nature02739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenck-Santini PP, Save E, Poucet B. Evidence for a relationship between the firing patterns of hippocampal place cells and rat's performance in a spatial memory task. Hippocampus. 2001;11:377–390. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenck-Santini PP, Rivard B, Muller RU, Poucet B. Study of CA1 place cell activity and exploratory behavior following spatial and nonspatial changes in the environment. Hippocampus. 2005;15:356–369. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutgeb JK, Leutgeb S, Treves A, Meyer R, Barnes CA, McNaughton BL, Moser MB, Moser EI. Progressive transformation of hippocampal neuronal representations in “morphed” environments. Neuron. 2005;48:345–358. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie K, Wilson MA. Temporally structured replay of awake hippocampal ensemble activity during rapid eye movement sleep. Neuron. 2001;29:145–156. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00186-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus EJ, Qin YL, Leonard B, Skaggs WE, McNaughton BL, Barnes CA. Interactions between location and task affect the spatial and directional firing of hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7079–7094. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07079.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr D. Simple memory: a theory for archicortex. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1971;262:23–81. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1971.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton BL, Barnes CA, Meltzer J, Sutherland RJ. Hippocampal granule cells are necessary for normal spatial learning but not for spatially-selective pyramidal cell discharge. Exp Brain Res. 1989;76:485–496. doi: 10.1007/BF00248904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton BL, Barnes CA, Gerrard JL, Gothard K, Jung MW, Knierim JJ, Kudrimoti H, Qin Y, Skaggs WE, Suster M, Weaver KL. Deciphering the hippocampal polyglot: the hippocampus as a path integration system. J Exp Biol. 1996;199:173–185. doi: 10.1242/jeb.199.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizumori SJ, McNaughton BL, Barnes CA, Fox KB. Preserved spatial coding in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells during reversible suppression of CA3c output: evidence for pattern completion in hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1989;9:3915–3928. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-11-03915.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller RU, Kubie JL. The effects of changes in the environment on the spatial firing of hippocampal complex-spike cells. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1951–1968. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-07-01951.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller RU, Kubie JL, Ranck JB., Jr Spatial firing patterns of hippocampal complex-spike cells in a fixed environment. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1935–1950. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-07-01935.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller RU, Stead M, Pach J. The hippocampus as a cognitive graph. J Gen Physiol. 1996;107:663–694. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.6.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa K, Sun LD, Quirk MC, Rondi-Reig L, Wilson MA, Tonegawa S. Hippocampal CA3 NMDA receptors are crucial for memory acquisition of one-time experience. Neuron. 2003;38:305–315. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe J, Dostrovsky J. The hippocampus as a spatial map. Preliminary evidence from unit activity in the freely moving rat. Brain Res. 1971;34:171–175. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe J, Nadel L. Hippocampus as a cognitive map. Oxford, UK: Clarendon; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe J, Speakman A. Single unit activity in the rat hippocampus during a spatial memory task. Exp Brain Res. 1987;68:1–27. doi: 10.1007/BF00255230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill J, Senior TJ, Allen K, Huxter JR, Csicsvari J. Reactivation of experience-dependent cell assembly patterns in the hippocampus. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:209–215. doi: 10.1038/nn2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Ed 5. Sydney: Academic; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz-Villagrán V, Save E, Poucet B. Independent coding of connected environments by place cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:1379–1390. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poucet B. Spatial cognitive maps in animals: new hypotheses on their structure and neural mechanisms. Psychol Rev. 1993;100:163–182. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.100.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poucet B, Benhamou S. The neuropsychology of spatial cognition in the rat. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1997;11:101–120. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v11.i2-3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renaudineau S, Poucet B, Save E. Flexible use of proximal objects and distal cues by hippocampal place cells. Hippocampus. 2007;17:381–395. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivard B, Li Y, Lenck-Santini PP, Poucet B, Muller RU. Representation of objects in space by two classes of hippocampal pyramidal cell. J Gen Physiol. 2004;124:9–25. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET, Kesner RP. A computational theory of hippocampal function and empirical tests of the theory. Prog Neurobiol. 2006;79:1–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samsonovich A, McNaughton BL. Path integration and cognitive mapping in a continuous attractor neural network model. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5900–5920. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05900.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaggs WE, McNaughton BL. Replay of neuronal firing sequences in rat hippocampus during sleep following spatial experience. Science. 1996;271:1870–1873. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5257.1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treves A, Rolls ET. Computational constraints suggest the need for two distinct input systems to the hippocampal CA3 network. Hippocampus. 1992;2:189–199. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450020209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazdarjanova A, Guzowski JF. Differences in hippocampal neuronal population responses to modifications of an environmental context: evidence for distinct, yet complementary, functions of CA3 and CA1 ensembles. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6489–6496. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0350-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TJ, Lever C, Cacucci F, Burgess N, O'Keefe J. Attractor dynamics in the hippocampal representation of the local environment. Science. 2005;308:873–876. doi: 10.1126/science.1108905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witter MP, Amaral DG. Hippocampal formation. In: Paxinos GT, editor. The rat nervous system. Ed 3. San Diego: Academic; 2004. pp. 635–704. [Google Scholar]

- Wood ER, Dudchenko PA, Eichenbaum H. The global record of memory in hippocampal neuronal activity. Nature. 1999;397:613–616. doi: 10.1038/17605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood ER, Dudchenko PA, Robitsek RJ, Eichenbaum H. Hippocampal neurons encode information about different types of memory episodes occurring in the same location. Neuron. 2000;27:623–633. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]