Abstract

Relapse to drug taking induced by exposure to cues associated with drugs of abuse is a major challenge to the treatment of drug addiction. Previous studies indicate that drug seeking can be inhibited by disrupting the reconsolidation of a drug-related memory. Stress plays an important role in modulating different stages of memory including reconsolidation, but its role in the reconsolidation of a drug-related memory has not been investigated. Here, we examined the effects of stress and corticosterone on reconsolidation of a drug-related memory using a conditioned place preference (CPP) procedure. We also determined the role of glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) in the basolateral amygdala (BLA) in modulating the effects of stress on reconsolidation of this memory. We found that rats acquired morphine CPP after conditioning, and that this CPP was inhibited by stress given immediately after re-exposure to a previously morphine-paired chamber (a reconsolidation procedure). The disruptive effect of stress on reconsolidation of morphine related memory was prevented by inhibition of corticosterone synthesis with metyrapone or BLA, but not central amygdala (CeA), injections of the glucocorticoid (GR) antagonist RU38486 [(11,17)-11-[4-(dimethylamino)phenyl]-17-hydroxy-17-(1-propynyl)estra-4,9-dien-3-one]. Finally, the effect of stress on drug related memory reconsolidation was mimicked by systemic injections of corticosterone or injections of RU28362 [11,17-dihydroxy-6-methyl-17-(1-propynyl)androsta-1,4,6-triene-3-one] (a GR agonist) into BLA, but not the CeA. These results show that stress blocks reconsolidation of a drug-related memory, and this effect is mediated by activation of GRs in the BLA.

Keywords: memory, stress, morphine, corticosterone, reconsolidation, amygdala

Introduction

Drug addiction is a chronic, relapsing brain disorder (O'Brien and McLellan, 1996; Leshner, 1997). According to recent theories, abused drugs pathologically usurp the neural mechanisms of learning and memory that shape behaviors under normal circumstances (White, 1996; Hyman, 2005; Hyman et al., 2006). Indeed, repeated association of drugs use with contexts predicting drug availability leads synaptic plasticity changes in physiological mechanisms that control normal learning and memory (Shaham et al., 2003; Lu et al., 2006; Valjent et al., 2006a,b). Reactivation of consolidated memory returns this memory to a labile, sensitive state, during which it can be modified, changed or even erased (Nader, 2003). This reactivated memory often undergoes another process of consolidation, called reconsolidation, to be restabilized (Nader et al., 2000; Sara, 2000; Debiec et al., 2002; Alberini, 2005; Tronson and Taylor, 2007). Using pharmacological techniques, a growing body of studies has determined the neuronal events, including receptors, signal transduction pathways, or proteins, that mediate memory reconsolidation (Tronson et al., 2006; Tronson and Taylor, 2007). Using drugs as reinforcers, investigators reported that the β-adrenoreceptor antagonist propranolol, administered after reactivation of cocaine or morphine conditioned place preference (CPP), impairs drug seeking via disruption of reconsolidation (Bernardi et al., 2006; Robinson and Franklin, 2007). Infusion of Zif268 antisense oligodeoxynucleotides into the basolateral amygdala (BLA), before the reactivation of a well learned memory for a conditioned stimulus-cocaine association, abolishes the acquired conditioned reinforcing properties of the drug-associated stimulus (Lee et al., 2005). Likewise, cue-induced cocaine seeking and relapse are reduced by disruption of drug-memory reconsolidation (Lee et al., 2006). Morphine CPP is persistently disrupted when anisomycin, a protein synthesis inhibitor, is administered after a conditioning session (Milekic et al., 2006). When mice previously conditioned for cocaine place preference are re-exposed to cocaine in the drug-paired compartment after systemic administration of SL327 [α-[amino[(4-aminophenyl)thio]methylene]-2-(trifluoromethyl)benzeneacetonitrile], an inhibitor of ERK (extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase) activation, CPP response is abolished (Valjent et al., 2006a). Together, drug-related memory can be inhibited or erased by interrupting its reconsolidation process.

Extensive evidence from animal and human studies shows that stress and glucocorticoids play a critical but complicated role in different aspects of learning and memory (Lupien and McEwen, 1997; McGaugh and Roozendaal, 2002; Roozendaal, 2002; Nicholas et al., 2006). Stress and glucocorticoids enhance (Loscertales et al., 1998; Roozendaal, 2002) as well as impair (Newcomer et al., 1994; Diamond et al., 1996; Newcomer et al., 1999) memory consolidation. In contrast, memory retrieval is usually impaired with high circulating levels of glucocorticoids or after injections of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) agonists into different brain regions (de Quervain et al., 1998, 2000; Kuhlmann et al., 2005). However, little is known regarding the effects of stress on consolidation and reconsolidation of drug-related memories.

It is well known that glucocorticoids secreted during a stressful event enter the brain, bind to intracellular GRs, and regulate memories via activation of GRs in various regions (Roozendaal et al., 2002). Here, we examined the effects of cold-water stress and corticosterone on reconsolidation of drug-related memory using a morphine CPP procedure. We also examined the role of BLA GRs in the modulatory effects of stress on reconsolidation of this memory.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Two hundred and sixty-two Sprague Dawley male rats weighing 220–240 g were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center, Peking University Health Science Center. Rats weighed ∼300–320 g when experiments began. They were housed individually in a temperature- (23 ± 2 C°) and humidity (50 ± 5%)-controlled room with food and water available ad libitum. They were kept on a reverse 12 h light/dark cycle. All treatments of the rats were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The procedures were approved by the local Committee of Animal Use and Protection.

Drugs

All drugs used in this study were purchased from Sigma except morphine hydrochloride, which was from Qinghai Pharmaceutical. Metyrapone was dissolved in a vehicle containing 40% polyethylene glycol and 60% saline. Corticosterone, (11, 17)-11-[4-(dimethylamino)phenyl]-17-hydroxy-17-(1-propynyl)estra-4,9-dien-3-one (RU486), and 11,17-dihydroxy-6-methyl-17-(1-propynyl)androsta-1,4,6-triene-3-one (RU28362) were dissolved in saline containing 2% ethanol to reach an appropriate concentration. All drugs were freshly prepared before the experiments. Doses of drugs were based on previous reports (Roozendaal and McGaugh, 1997; de Quervain et al., 1998; Cai et al., 2006).

Surgery

Rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.), and permanent guide cannulas (23 gauge; Plastics One) were implanted bilaterally 1 mm above the BLA or CeA. The coordinates (Paxinos and Watson, 1998) for the BLA and CeA were as follows: anteroposterior (AP), −2.9 mm; mediolateral (ML), ± 5.0 mm; dorsoventral (DV), −8.5 mm; and AP, −2.9 mm; ML, ± 4.2 mm; DV, −7.8 mm, respectively. The cannulas were anchored to the skull with stainless-steel screws and dental cement. A stainless-steel style blocker was inserted into each cannula to keep them patent and prevent infection.

Intracranial injections

Injections were performed with Hamilton syringes, which were connected to 30-gauge injectors (Plastics One). RU486 or RU28362 was infused into the BLA or CeA bilaterally (0.5 μl per side) at a rate of 0.5 μl/min. The injection needle was kept in place for another 1 min (Lu et al., 2005b) to allow the drug to completely diffuse from the tips.

Conditioned place preference

The apparatus for CPP training and testing consisted of five identical three-chamber polyvinyl chloride (PVC) boxes. Two large side chambers (27.9 cm long × 21.0 cm wide × 20.9 cm high) were separated by a smaller one (12.1 cm long × 21.0 cm wide × 20.9 cm high with smooth PVC floor) with differences in floor texture (bar or grid, respectively). Three distinct chambers were separated by manual guillotine doors.

To determine the baseline preference, rats were initially placed in the middle chamber with the doors removed for 15 min (preconditioning test). A computer measured the time spent in the designated saline- or morphine-paired chambers during the 15 min session through interruption of infrared beams by animals. Most rats spent approximately one-third of time in each chamber (data not shown). Approximately 2% of the total rats were discarded because of a strong unconditioned preference (>540 s). Conditioning was performed using an unbiased, balanced protocol.

On the subsequent conditioning days, each rat was trained for 8 consecutive days with alternate injections of drug (morphine 5 mg/kg, s.c.) and saline (1 ml/kg, s.c.) (Bardo et al., 1995; Wang et al., 2006; Zhai et al., 2007). After each injection, rats were confined to the corresponding conditioning chambers for 45 min before returning to their home cages. The next day after conditioning, rats were tested for the expression of morphine (postconditioning test) CPP under conditions identical to those described in the preconditioning test. The place preference score (CPP score) was defined as the time spent in the morphine-paired chamber minus that spent in the morphine-unpaired (saline-paired) chamber (Harris et al., 2005).

Drug-memory reactivation

Rats were confined to the morphine-paired chamber for 10 min to selectively reactivate morphine reward memory (Milekic et al., 2006) and then given the different experimental treatments (see Experimental design).

Retesting of morphine CPP

One day (post-treatment 1) or 2 weeks (post-treatment 14) after memory reactivation, rats were retested for morphine CPP. If rats did not demonstrated morphine CPP 2 weeks after reactivation, they were administered a priming dose (3 mg/kg, s.c.) of morphine and immediately tested again (priming test).

Cold-water stress

During this procedure, rats performed a 5 min forced swim in a plastic cylindrical container, 35 × 40 cm (diameter by height), filled with ice-cold water up to a height of 30 cm (Korneyev et al., 1995).

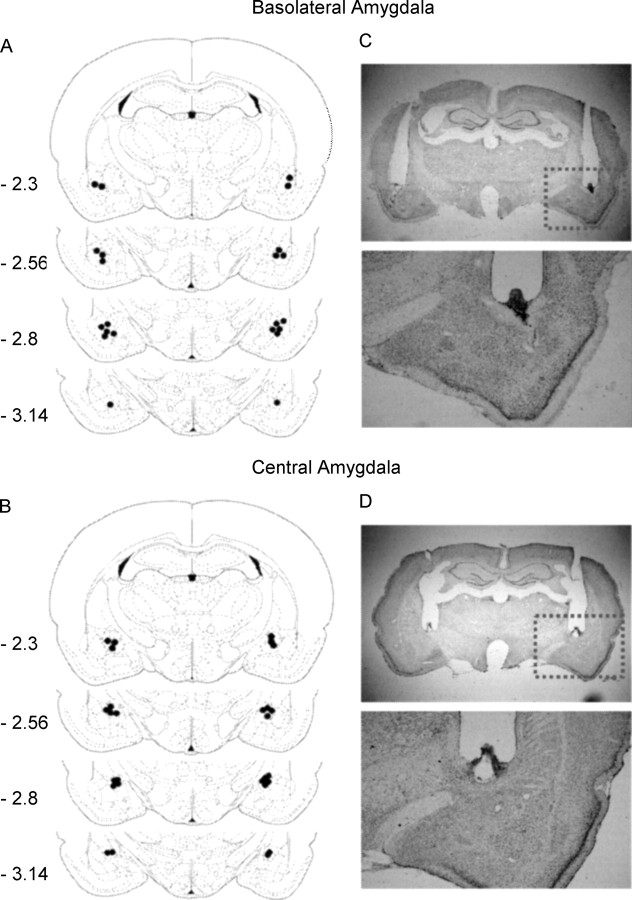

Histology

At the end of the experiments, rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, i.p.) and transcardially perfused. Cannula placements were assessed using Nissl staining with thickness of 40 μm under light microscopy. Subjects with misplaced cannulas were excluded from statistics. The locations of cannula tips from rats in part of experiment 4 (rats were microinjected RU28362 into the BLA immediately after re-exposure) are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A–D, Schematic representations of injection sites and photomicrographs of representative cannula placements in basolateral amygdala (A, C) and central amygdala (B, D).

Experimental design

Experiment 1: effect of stress on reconsolidation of morphine reward memory.

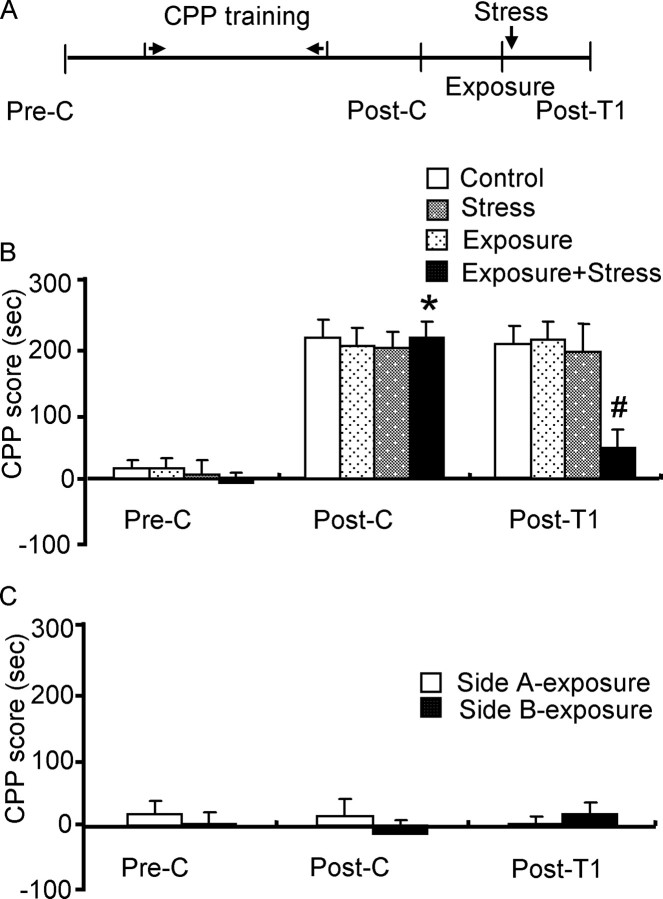

To determine the effect of stress on the reconsolidation of morphine reward memory, rats were randomly divided into four groups which were matched for CPP score and given different treatments 24 h after postconditioning: (1) rats were not given any treatment; (2) rats were re-exposed to the morphine-paired chamber for 10 min without the stress procedure; (3) rats were not re-exposed to any chamber before the stress procedure (cold-water stress for 5 min); (4) rats were exposed to the stress procedure immediately after re-exposure to previously morphine-paired chamber for 10 min. The four groups were named control, exposure, stress, and exposure plus stress, respectively (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Stress impaired reconsolidation of morphine reward memory. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. A, Behavioral procedure. B, Effect of stress on the reconsolidation of morphine reward memory. *p < 0.001 versus preconditioning or post-treatment 1 within group; #p < 0.001 versus any other group during post-treatment 1. C, Stress did not produce either preference or aversion toward both side chambers (n = 7–9 per group). Pre-C, Preconditioning; Post-C, postconditioning; Post-T1, post-treatment 1.

To exclude the possibility that postreactivation stress produced an aversive associative memory between the drug-paired context and stress, which counteracted the morphine reward memory, another two groups of rats were trained and tested for CPP as described above, except that rats always received saline injections before being placed in both side chambers during the 8 d CPP training. The next day after postconditioning, rats were exposed to stress immediately after re-exposure to one of the two side chambers (named side A and side B). Twenty-four hours after the stress task, rats were retested for the expression of CPP (see Fig. 2).

Experiment 2: effect of corticosterone on the reconsolidation of morphine reward memory.

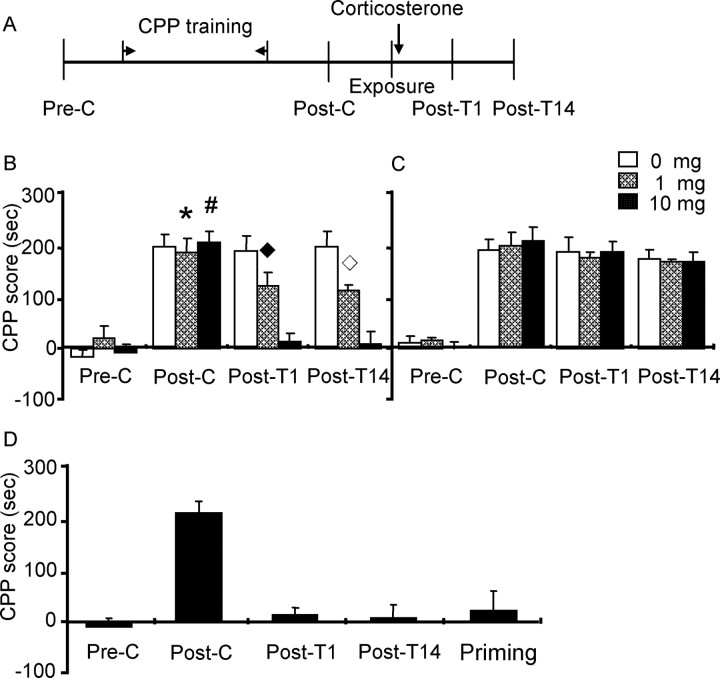

The purpose of this experiment was to investigate whether the inhibitory effect of postreactivation stress on morphine reward memory is mediated by the stress hormone corticosterone. The next day after postconditioning, three groups of rats were injected with different doses of corticosterone (0, 1, and 10 mg/kg respectively, i.p.) immediately after re-exposure to the previously morphine-paired chambers. Moreover, to determine whether the inhibitory effect of corticosterone on morphine reward memory was reactivation dependent, three additional groups of rats were given the same treatments except that they were not re-exposed to the previously morphine-paired chambers (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Corticosterone produced dose-dependent impairment in reconsolidation of morphine reward memory. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. A, Behavioral procedure. B, Systemic administration of corticosterone immediately after exposure to morphine-paired context impaired the reconsolidation of morphine reward memory. *p < 0.01 versus preconditioning, post-treatment 1, or post-treatment 14 (retesting of morphine CPP 2 weeks after post-treatment1 test) within the 1 mg corticosterone group; #p < 0.01 versus preconditioning, post-treatment, or post-treatment 14 within the 10 mg corticosterone group; ♦p < 0.05 versus any other group during post-treatment 1; ◇p < 0.05 versus any other group during post-treatment 14. C, Systemic administration of corticosterone without exposure to morphine-paired context did not impair the reconsolidation of morphine reward memory. D, The inhibitory effect of corticosterone on the expression of morphine CPP lasted for at least 14 d. When given 3 mg/kg morphine, rats in the group with 10 mg/kg corticosterone immediately after exposure did not demonstrate morphine CPP (n = 6–7 per group). Pre-C, Preconditioning; Post-C, postconditioning; Post-T1, post-treatment 1; Post-T14, post-treatment 14; Priming, priming by 3 mg/kg morphine.

Experiment 3: effect of metyrapone on stress-induced impairment of reconsolidation of morphine reward memory.

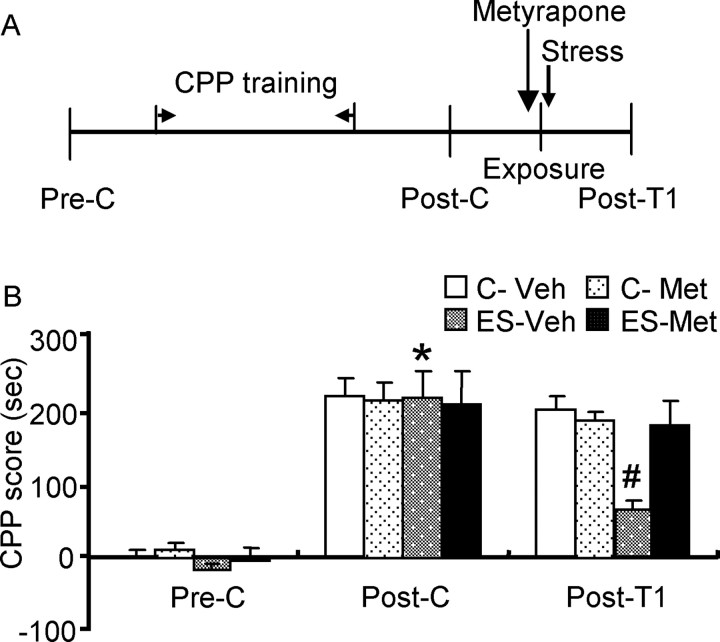

To further confirm the potential role of corticosterone in stress-induced impairment of reconsolidation of morphine reward memory, we examined whether inhibiting synthesis of corticosterone would block the effect of stress. Twenty-four hours after postconditioning, rats were given a cold-water swim stress after re-exposure to the previously morphine-paired chamber. Rats were systemically injected with metyrapone, a corticosterone synthesis inhibitor, or vehicle 40 min before stress (de Quervain et al., 1998). The other two control groups were given the same treatments, but neither experienced re-exposure to the previously morphine-paired chamber nor the stress procedure (see Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Metyrapone blocked stress-induced impairment in reconsolidation of morphine reward memory. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. A, Behavioral procedure for experiment 3. B, Metyrapone blocked the inhibitory effect of stress on reconsolidation of morphine reward memory. *p < 0.001 versus post-treatment 1 within the exposure-stress vehicle (ES-Veh) group; #p < 0.001 versus the exposure-stress metyrapone (ES-Met) group during post-treatment 1 (n = 8–9 per group). C-Veh, Control vehicle group; C-Met, control metyrapone group; Pre-C, Preconditioning; Post-C, postconditioning; Post-T1, post-treatment 1.

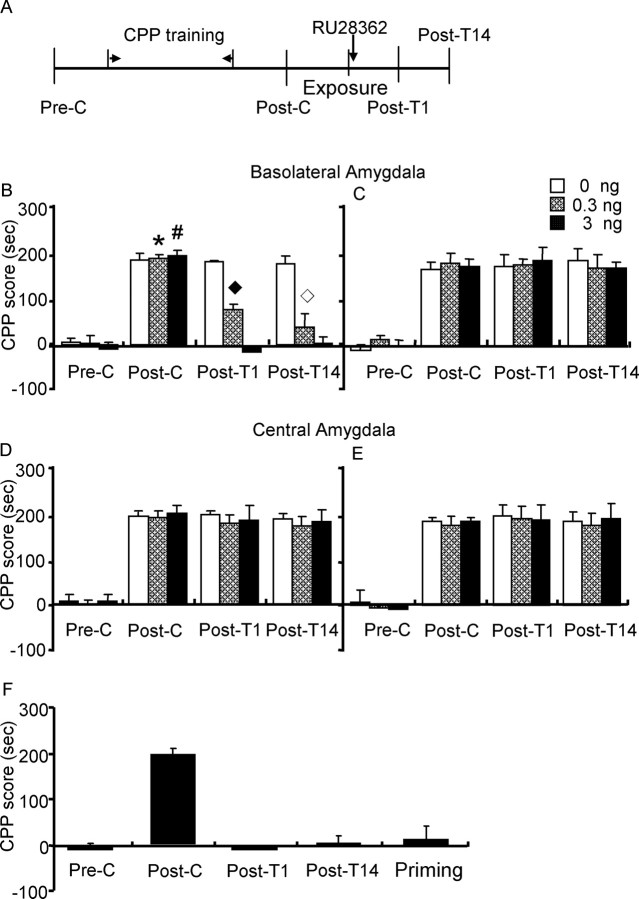

Experiment 4: effect of RU28362 in BLA on the reconsolidation of morphine reward memory.

Based on the important modulatory role of the GRs in the amygdala on learning and memory (Morimoto et al., 1996; Hamann, 2001; McGaugh, 2002; Rodrigues et al., 2004), we examined the role of GRs in subregions of the amygdala in stress-induced impairment of reconsolidation of morphine reward memory by injecting RU28362, a glucocorticoid receptor agonist, into the BLA or CeA. Twenty-four hours after postconditioning, three groups of rats were microinjected different doses of RU28362 (0, 0.3 or 3 ng per side) into BLA immediately after re-exposure to the previously morphine-paired chambers; three other groups received the same treatment but without being given the re-exposure procedure. To examine brain region/subregion specificity in the inhibitory effect of postreactivation RU28362, another six groups of rats were given the same treatments as that in BLA except that drugs were infused into the CeA (see Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Microinjection of RU28362 into the basolateral amygdala, but not into the central amygdala, impaired the reconsolidation of morphine reward memory. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. A, Behavioral procedure for experiment 4. B, Microinjection of RU28362 into the BLA immediately after exposure to the morphine-paired context impaired the reconsolidation of morphine reward memory. *p < 0.01 versus preconditioning, post-treatment 1, or post-treatment 14 within the 0.3 ng RU28362 group; #p < 0.01 versus preconditioning, post-treatment 1, or post-treatment 14 within the 3 ng RU28362 group; ♦p < 0.05 versus any other group during post-treatment 1; ◇p < 0.05 versus any other group during post-treatment 14. C, Microinjection of RU28362 into the BLA without exposure to the morphine-paired context did not impair the reconsolidation of morphine reward memory. D, E, Microinjection of RU28362 into the CeA had no effect on the reconsolidation of morphine reward memory after re-exposure to the previously morphine-paired chamber (D) or not (E). F, The inhibitory effect of RU28362 on the expression of morphine CPP lasted 14 d at least. When given 3 mg/kg morphine, rats in group with RU28362 (3 ng per side) into the BLA immediately after exposure did not demonstrate morphine CPP (n = 6–9 per group). Pre-C, Preconditioning; Post-C, postconditioning; Post-T1, post-treatment 1; Post-T14, post-treatment 14; Priming, priming by 3 mg/kg morphine.

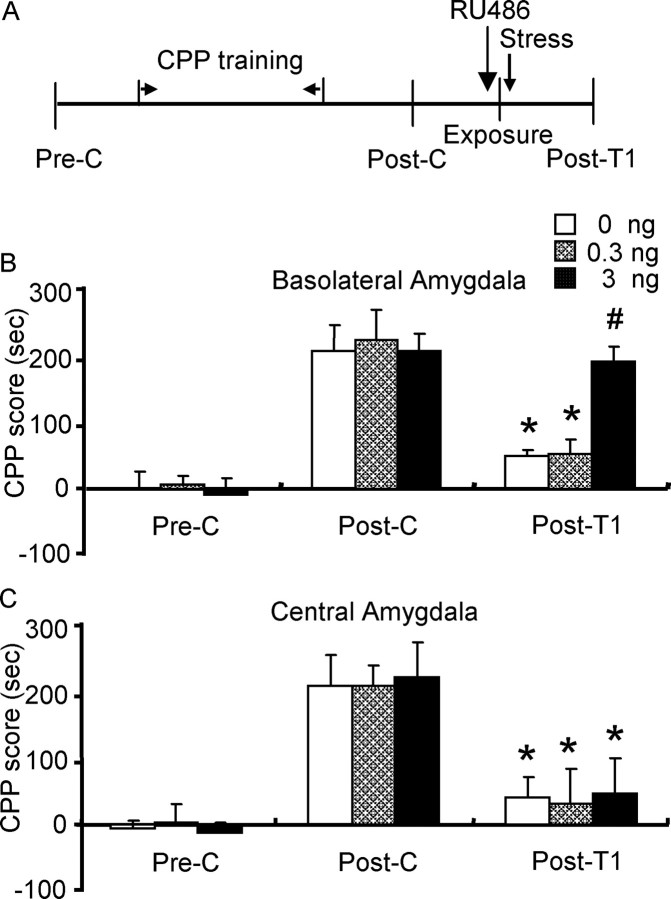

Experiment 5: effect of RU486 in the BLA on stress-induced impairment of the reconsolidation of morphine reward memory.

To further examine the role of GRs in stress-induced impairment of the reconsolidation of morphine reward memory, rats were exposed to stress after re-exposure to the previously morphine-paired chamber, and were injected different doses of RU486 (0.3, 3 ng per side) or vehicle into BLA or CeA 10 min before stress (Jin et al., 2007) (see Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

RU486 into basolateral amygdala, but not into central amygdala, blocked stress-induced impairment in reconsolidation of morphine reward memory. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. A, Behavioral procedure for experiment 5. B, High dose of RU486 (3 ng per side) blocked the inhibitory effect of stress on reconsolidation of morphine reward memory. *p < 0.001 versus the corresponding postconditioning group; #p < 0.01 versus vehicle group during post-treatment 1. No significant difference between post-treatment 1 and postconditioning within 3 ng BLA microinjection group (p = 0.83). C, Microinjection of RU486 into CeA had no effect on the effect of stress on the reconsolidation of morphine reward memory; *p < 0.001 versus the corresponding postconditioning group (n = 6–8 per group). Pre-C, Preconditioning; Post-C, postconditioning; Post-T1, post-treatment 1.

Data analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Two- or three-way mixed factorial ANOVAs were performed on the data with the between-subjects factors of exposure (exposure or no exposure) and treatment (stress or different drugs), and the within-subjects factor of test condition (preconditioning, postconditioning, or post-treatment). To test the long-term effects of corticosterone and RU28362, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to analyze the differences in CPP scores among the test conditions. All post hoc comparisons were made using Tukey's test. Results with p < 0.05 were accepted as being statistically significant.

Results

Stress impaired reconsolidation of morphine reward memory

In experiment 1, a three-way ANOVA conducted on CPP score using exposure (exposure or no exposure) and stress (stress or no stress) as the between-subjects factors and test condition (preconditioning, postconditioning or post-treatment 1) as the within-subjects factor, revealed that there was a significant interaction of exposure × stress × test condition (F(2,80) = 3.55; p = 0.03) and exposure × stress (F(1,80) = 7.32; p = 0.008). Post hoc analysis showed that after morphine CPP training, all groups acquired CPP (p < 0.001) and there were no differences in CPP scores between any two groups during postconditioning. Compared with the postconditioning test, the CPP score was significantly decreased only in the group of rats exposed to cold-water swim stress after re-exposure to the previously morphine-paired chamber (p < 0.001) in the post-treatment 1 test, as shown in Figure 2B. Thus, the inhibitory effect of stress on reconsolidation of morphine reward memory was dependent on reactivation of morphine CPP.

Because cold-water stress itself was an aversive experience, it may be argued that, during the reactivation session, an associative memory was formed between the morphine-paired context and the stressor. In this manner, the effect of postreactivation stress on the expression of morphine CPP may be attributable to the aversive effect of stress. To exclude this possibility, rats were trained for CPP using saline. After 8 d of conditioning, rats did not show any preference or aversion toward both side chambers. Rats were then exposed to stress after re-exposure to one of the side chambers. A two-way ANOVA showed that a single exposure to the cold-water stress task did not produce conditioned place aversion after re-exposure to the side chambers (p > 0.05), as shown in Figure 2C.

Corticosterone impaired reconsolidation of morphine reward memory

In experiment 2, corticosterone was systemically administered to mimic the effect of stress. A three-way ANOVA showed a significant interaction of exposure (exposure or no exposure) × corticosterone (0, 1, or 10 mg/kg) × test condition (preconditioning, postconditioning, post-treatment 1, or post-treatment 14) (F(6,122) = 3.29; p = 0.005), corticosterone × test condition (F(6,122) = 3.89; p = 0.001), and exposure × test condition (F(3,122) = 5.16; p = 0.002). Post hoc analysis showed that after morphine CPP training, all groups acquired CPP (p < 0.001), and there were no differences in CPP scores between any two groups during postconditioning. However, CPP was inhibited after post-treatment (post-treatment 1) in groups of rats receiving corticosterone after re-exposure (p = 0.04 for 1 mg/kg and p < 0.001 for10 mg/kg) (Fig. 3B); CPP was not altered in groups of rats that were administered corticosterone but not re-exposed to the previously morphine-paired chamber (Fig. 3C).

To observe the long-term effect of corticosterone on reconsolidation of morphine reward memory, rats were tested for the expression of morphine CPP 14 d after postreactivation (post-treatment 14). CPP did not recover in the groups of rats administered corticosterone (Fig. 3B). The effect of postreactivation corticosterone was not caused by the extinction of CPP because there were no significant differences in CPP scores between post-treatment 14 and postconditioning or post-treatment 1 (p > 0.05) within vehicle-exposure groups and all nonexposure groups (Fig. 3B,C). To examine whether the original drug-reward memory was persistently disrupted by postreactivation corticosterone, rats in the re-exposure group of 10 mg corticosterone were administered a priming dose of morphine (3 mg/kg, s.c.), and CPP was tested again (a priming test). A one-way ANOVA showed that there were no significant differences in CPP scores between the priming test and post-treatment 14 or preconditioning, indicating that a priming injection of morphine did not reinstate morphine CPP (Fig. 3D). Together, these results indicate that the inhibitory effect of postreactivation corticosterone on reconsolidation of morphine reward memory lasted at least 2 weeks.

Metyrapone reversed stress-induced impairment in reconsolidation of morphine reward memory

Stress and corticosterone administration showed similar effects on reconsolidation of morphine reward memory, suggesting that the inhibitory effect of postreactivation stress is related to increased corticosterone level. Thus, we hypothesized that metyrapone, a corticosterone synthesis inhibitor, would block stress-induced impairment of reconsolidation of morphine reward memory. A three-way ANOVA indicated a trend for a significant interaction of exposure (exposure or no exposure) × metyrapone (0 or 50 mg/kg) × test condition (preconditioning, postconditioning or post-treatment 1) (F(2,83) = 2.43; p = 0.09). However, there was a significant difference in CPP scores between the vehicle and metyrapone groups (F(1,83) = 4.45; p = 0.038). Post hoc analysis showed that after morphine CPP training, all groups acquired CPP (p < 0.001) and there were no differences in CPP scores between any two groups during postconditioning. The expression of CPP was inhibited after post-treatment (post-treatment 1) in rats receiving postreactivation stress (p < 0.001). Moreover, metyrapone administration before stress reversed the effect of postreactivation stress (p < 0.001, vehicle vs metyrapone during post-treatment) (Fig. 4B).

RU28362 in the BLA impaired the reconsolidation of morphine reward memory

In experiment 4, RU28362 was injected into the BLA or CeA to examine the role of GR in the effect of stress on reconsolidation of morphine reward memory. A three-way ANOVA revealed a significant interaction of exposure (exposure or no exposure) × RU28362 (0, 0.3, or 3 ng per side) × test condition (preconditioning, postconditioning, post-treatment 1, or post-treatment 14) (F(6,138) = 4.43; p < 0.001), exposure × RU28362 (F(2,138) = 3.80; p = 0.02), RU28362 × test condition (F(6,138) = 5.65; p < 0.001), and exposure × test condition (F(3,138) = 19.79; p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis showed that, after morphine CPP training, all groups acquired CPP (p < 0.001) and there were no differences in CPP scores between any two groups during postconditioning. The CPP (post-treatment 1) was inhibited in rats that were given postreactivation RU28362 into BLA (p < 0.001) (Fig. 5B,C). However, no significant effects were observed in any of the groups with microinjection of RU28362 into CeA (Fig. 5D,E).

To examine the long-term effect of RU28362 in the BLA on reconsolidation of morphine reward memory, rats were tested for the expression of morphine CPP 14 d after RU28362 administration (post-treatment 14). The CPP did not recover in groups receiving microinjection of RU28362 into BLA after re-exposure to the previously morphine-paired chambers (Fig. 5B). The effect of RU28362 in BLA was not attributable to the extinction of the CPP because there were no significant differences in CPP scores between post-treatment 14 and postconditioning or post-treatment 1 (p > 0.05) within the vehicle-exposure group (Fig. 5B) or in all nonexposure groups (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, there were no significant differences in CPP scores between post-treatment 14 and postconditioning or post-treatment 1 (p > 0.05) in all groups receiving microinjection of RU28362 into CeA (Fig. 5D,E).

Rats in the re-exposure group receiving microinjection of RU28362 (3 ng per side) into BLA were administered a priming dose of morphine (3 mg/kg) were and tested again (priming test). A one-way ANOVA showed that there was no significant difference in CPP scores between the priming test and post-treatment 14 or preconditioning, indicating that a priming dose of morphine did not reinstate CPP (Fig. 5F). Together, these results suggest that the inhibitory effect of RU28263 on reconsolidation of morphine reward memory lasted at least 2 weeks.

RU486 in BLA blocked the stress-induced impairment in reconsolidation of morphine reward memory

To provide further evidence that activation of BLA glucocorticoid receptors mediate the stress-induced impairment in reconsolidation of morphine reward memory, RU486 was microinjected into the BLA or CeA, and the effect of RU486 on the postreactivation effect of stress was examined. A two-way ANOVA showed a significant interaction of RU486 (0, 0.3, or 3 ng per side) × test condition (preconditioning, postconditioning or post-treatment 1) (F(4,34) = 6.97; p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis showed that after morphine CPP training, all groups acquired CPP (p < 0.001) and there were no differences in CPP scores between any two groups after postconditioning. After post-treatment, there was a significant difference in CPP scores between the 3 ng and vehicle (p = 0.002) or 0.3 ng group (p = 0.002), but no significant difference between the vehicle and 0.3 ng groups. This result indicates that the high but not low dose of RU486 blocked the inhibitory effect of postreactivation stress (Fig. 6B). However, no significant effects on postreactivation stress were observed in the groups receiving microinjection of RU486 into CeA (Fig. 6C).

Discussion

The main findings of present study were as follows: (1) rats acquired morphine CPP after conditioning, and the reconsolidation of morphine reward memory was disrupted by stress; (2) systemic administration of corticosterone showed effects similar to stress; corticosterone impaired reconsolidation of morphine reward memory; (3) systemically administered metyrapone blocked stress-induced impairment in the reconsolidation of morphine reward memory; (4) microinjection of RU28362 into the BLA, but not into the CeA, disrupted reconsolidation of morphine reward memory; (5) microinjection of RU486 into the BLA, but not into the CeA, blocked stress-induced impairment in reconsolidation of morphine reward memory. These findings suggest that exposure to stress, immediately after reactivation of a morphine-related memory, blocked its reconsolidation. This effect is mediated by activation of GRs in the BLA.

The effect of stress on reconsolidation of emotional memories

Numerous studies have demonstrated that stress plays an important but complex role in learning and memory. Most of those studies have focused on the effects of stress or glucocorticoids on consolidation and retrieval of normal memory and have shown an inverse U-shaped dose–response relationship with consolidation (Lupien and McEwen, 1997; Sandi et al., 1997; Roozendaal et al., 1999) and an inhibitory effect on retrieval (de Quervain et al., 1998, 2000; Roozendaal, 2002). Only a few groups have studied the effects of stress or glucocorticoids on reconsolidation of memory. Cai et al. (2006) reported that when glucocorticoids are administered immediately after reactivation of a contextual fear memory, subsequent recall is significantly diminished. However, the effect of postreactivation glucocorticoid on contextual fear memory is reversed by a reminder shock. This finding suggests that augmentation of single-trial contextual fear memory extinction is the more likely mechanism for the effects of postreactivation corticosterone on subsequent memory (Cai et al., 2006). Maroun and Akirav (2008) provided the first evidence that stress might have an inhibitory effect on the reconsolidation of memory. They found that in habituated (high arousal level) and nonhabituated (low arousal level) rats, exposure to an out-of-context stressor impaired long-term reconsolidation of objective recognition memory (Maroun and Akirav, 2007).

Our previous study was the first to demonstrate that cocaine CPP was blocked in rats experiencing stress after re-exposure to the previously drug-paired chamber, showing a potential inhibitory effect of stress on reconsolidation of drug-related memory (Zhao et al., 2007). In the present study, a potent and stable stress model (Retana-Marquez et al., 2003) was used, and rats received a cold-water stress after a single-trial reactivation of morphine reward memory. Morphine CPP was blocked in rats that were given postreactivation stress. In saline trained rats, exposure to a cold-water stress immediately after re-exposure to any chamber did not produce aversion toward the chambers. This finding suggests that the inhibitory effect of postreactivation stress on morphine reward memory was not caused by the summation of the aversive effects of stress and morphine reward on conditioned place preference for the morphine-paired chamber. Furthermore, we demonstrated that a high dose of the endogenous stress hormone, corticosterone, mimicked the effects of stress. A low dose of corticosterone after reactivation only reduced, but did not block, subsequent recall of morphine CPP.

Our findings do not support a role of stress and corticosterone in the augmentation of extinction because a single 10 min morphine-context re-exposure did not induce extinction of morphine CPP in rats pretreated with corticosterone. More importantly, a priming dose of morphine failed to reinstate morphine CPP in these rats, and morphine CPP did not recover after treatment with postreactivation corticosterone. These findings suggest that the effects of postreactivation corticosterone were attributable to impairment of reconsolidation, but not to the augmentation of extinction of morphine reward memory (Suzuki et al., 2004; Cai et al., 2006).

Previous studies have shown that duration of exposure, strength, and age of a memory may be important determinants of subsequent memory processing (Suzuki et al., 2004). Short exposure to the original learning context results in reconsolidation, whereas longer exposure leads to extinction (Pedreira and Maldonado, 2003). Regarding the effect of strength and age of memory, strong memories are more resistant to the disruptive effects of protein synthesis inhibition during reactivation, and young memory is more prone to be disrupted than an old memory (Milekic and Alberini, 2002; Suzuki et al., 2004). Training for conditioned fear memory with one footshock required 3 min, but training with three footshocks required 10 min to reconsolidate (Suzuki et al., 2004), indicating that longer re-exposure is required to reconsolidate a stronger memory. A more recent study reported that corticosterone impairs memory retrieval in rats trained for conditioned fear memory at high shock, but not at low shock, intensities (Abrari et al., 2007). This finding indicates that disruption of reconsolidation by administration of corticosterone after memory reactivation depends on training intensity (Abrari et al., 2007). However, those studies could not explain the discrepancy between the results of the study by Cai et al. (2006) and our study. Although the duration of exposure and the age of memory were similar in both studies, memory models were different (conditioned fear vs morphine reward memory); thus, it is impossible to compare the training intensity in these two studies. The proposed relationship between the susceptibility to disruption and the dominance of the trace after retrieval, which probably is an experimental manifestation of the theoretical dichotomous memory, may explain some lingering discrepancies in the literature on the effects of the blocking of consolidation after retrieval (Eisenberg et al., 2003).

Role of the BLA and glucocorticoid receptor activation in the reconsolidation of emotional memories

The BLA is part of a distributed network of neural structures implicated in the formation and storage of conditioned stimulus–unconditioned stimulus associations (Everitt et al., 1999, 2003) and in the processing of emotional events in relation to environmental stimuli that guide motivated behavior (Cardinal et al., 2002). To date, an important role of BLA in memory reconsolidation has been demonstrated in several types of memory tasks, such as fear memories (Nader et al., 2000; Duvarci et al., 2005), appetitive drug memories (Lee et al., 2005; Milekic et al., 2006), and drug-conditioned withdrawal memories (Hellemans et al., 2006).

Likewise, extensive evidence suggests that the BLA is a key region that regulates the effects of stress and glucocorticoids on memory formation, consolidation, and reconsolidation (Roozendaal and McGaugh, 1997; Roozendaal et al., 2002; Roozendaal, 2003). Lesions of the BLA, but not the CeA, block the dexamethasone-induced memory enhancement in an inhibitory avoidance task, suggesting that the BLA is a critical site for the modulatory effect of glucocorticoids on memory formation (Roozendaal and McGaugh, 1996). It has been reported that glucocorticoids in BLA, but not the CeA, contribute to memory consolidation. Post-training infusions of a GR agonist into the BLA, but not into the CeA, enhance memory performance (Roozendaal and McGaugh, 1997). Immediate postretrieval intra-BLA infusion of RU486 selectively impairs long-term auditory fear memory, suggesting that glucocorticoid receptors in the BLA are required for reconsolidation of auditory fear memory (Jin et al., 2007).

Consistent with previous studies, we showed that a GR agonist injected into the BLA, but not into the CeA, after memory reactivation mimics the effects of postreactivation stress. Moreover, we demonstrated that a GR antagonist infused into the BLA, but not into the CeA, reversed the inhibitory effect of postreactivation stress on a morphine reward memory. This finding suggests that activation of GRs in the BLA plays a critical role in the effects of postreactivation stress on drug-related memory.

Differential role of stress in reconsolidation of a drug-related memory and reinstatement of drug seeking

In this study, we found that stress and corticosterone impaired reconsolidation of a morphine related memory, a result consistent with the finding that stress impairs reconsolidation of recognition memory (Maroun and Akirav, 2007), but seemingly paradoxical to other studies. Accumulating evidence indicates that stress plays an important role in inducing craving and reinstatement of drug seeking (Sinha, 2001; Lu et al., 2003; Shaham et al., 2003; Stewart, 2003). We consider the role of stress in reinstatement and reconsolidation as two qualitatively different phenomena. One issue to consider is the temporal relationship between stress exposure and the measurement of drug seeking. In our study, stress exposure occurred immediately after memory retrieval of the morphine-paired context, and most importantly, the stress-induced memory retrieval deficit occurred the next day and persisted for at least 2 weeks. In contrast, in the stress-reinstatement model (Shaham et al., 2000; Stewart, 2000; Lu et al., 2003; Bossert et al., 2005), laboratory animals with a history of drug administration are exposed to stress after extinction of the drug-reinforced responding (Shaham and Stewart, 1995; Der-Avakian et al., 2001; Shaham et al., 2003; Ribeiro Do Couto et al., 2006). The intervening period between drug-memory acquisition and stress may play a critical role in stress-induced reinstatement of drug seeking because during this interval some neuroadaptations may occur in both reward- and stress/stress-coping circuits (Diana et al., 1998; Kalivas et al., 1998; Robinson and Berridge, 2000; Grimm et al., 2003; Lu et al., 2005a,b; Weiss, 2005; Pu et al., 2006).

Another issue to consider is that the neurobiological mechanisms mediating the effect of stress on memory reconsolidation and reinstatement are most likely different. We found that corticosterone played an essential role in mediating the inhibitory effect of stress on reconsolidation of a morphine-related memory. In contrast, stress-induced reinstatement of drug seeking is independent of activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and corticosterone release (Shaham et al., 1997; Erb et al., 1998; Le et al., 2000).

Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrated that established drug-related memories are disrupted by exposure to stress or corticosterone after memory reactivation via inhibition of its reconsolidation. Furthermore, our results indicate that the BLA is a critical brain region involved in integrating the influences of corticosterone on drug-related memory. Glucocorticoid administration in humans has been shown previously to be a relevant pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders characterized by emotional memories, such as post-traumatic stress disorder and phobias (Aerni et al., 2004; Soravia et al., 2006; de Quervain and Margraf, 2008). Our results suggest a potential therapeutic value of glucocorticoids in the treatment of drug addiction.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by National Basic Research Program of China Grants 2007CB512302 and 2003CB 515400, the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (Program 863, 2006AA02Z4D1), and Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 30570576, 30670713, and 30725016. We thank Drs. Yanping Bao and Haifeng Zhai for the technical assistance and Dr. Yavin Shaham for comments on this manuscript.

References

- Abrari K, Rashidy-Pour A, Semnanian S, Fathollahi Y. Administration of corticosterone after memory reactivation disrupts subsequent retrieval of a contextual conditioned fear memory: dependence upon training intensity. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2007;14:14. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aerni A, Traber R, Hock C, Roozendaal B, Schelling G, Papassotiropoulos A, Nitsch RM, Schnyder U, de Quervain DJ. Low-dose cortisol for symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1488–1490. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberini CM. Mechanisms of memory stabilization: are consolidation and reconsolidation similar or distinct processes? Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardo MT, Rowlett JK, Harris MJ. Conditioned place preference using opiate and stimulant drugs: a meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1995;19:39–51. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)00021-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi RE, Lattal KM, Berger SP. Postretrieval propranolol disrupts a cocaine conditioned place preference. NeuroReport. 2006;17:1443–1447. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000233098.20655.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossert JM, Ghitza UE, Lu L, Epstein DH, Shaham Y. Neurobiology of relapse to heroin and cocaine seeking: an update and clinical implications. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;526:36–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai WH, Blundell J, Han J, Greene RW, Powell CM. Postreactivation glucocorticoids impair recall of established fear memory. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9560–9566. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2397-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal RN, Parkinson JA, Hall J, Everitt BJ. Emotion and motivation: the role of the amygdala, ventral striatum, and prefrontal cortex. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26:321–352. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Quervain DJ, Margraf J. Glucocorticoids for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder and phobias: a novel therapeutic approach. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;583:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Quervain DJ, Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL. Stress and glucocorticoids impair retrieval of long-term spatial memory. Nature. 1998;394:787–790. doi: 10.1038/29542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Quervain DJ, Roozendaal B, Nitsch RM, McGaugh JL, Hock C. Acute cortisone administration impairs retrieval of long-term declarative memory in humans. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:313–314. doi: 10.1038/73873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debiec J, LeDoux JE, Nader K. Cellular and systems reconsolidation in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2002;36:527–538. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Der-Avakian A, Durkan BT, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Stress-induced reinstatement of a morphine conditioned place preference. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2001;27:666–8. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond DM, Fleshner M, Ingersoll N, Rose GM. Psychological stress impairs spatial working memory: relevance to electrophysiological studies of hippocampal function. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110:661–672. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.4.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diana M, Melis M, Muntoni AL, Gessa GL. Mesolimbic dopaminergic decline after cannabinoid withdrawal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10269–10273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvarci S, Nader K, LeDoux JE. Activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase- mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade in the amygdala is required for memory reconsolidation of auditory fear conditioning. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:283–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg M, Kobilo T, Berman DE, Dudai Y. Stability of retrieved memory: inverse correlation with trace dominance. Science. 2003;301:1102–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1086881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Shaham Y, Stewart J. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor and corticosterone in stress- and cocaine-induced relapse to cocaine seeking in rats. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5529–5536. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05529.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Parkinson JA, Olmstead MC, Arroyo M, Robledo P, Robbins TW. Associative processes in addiction and reward. The role of amygdala-ventral striatal subsystems. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;877:412–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Cardinal RN, Parkinson JA, Robbins TW. Appetitive behavior: impact of amygdala-dependent mechanisms of emotional learning. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;985:233–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm JW, Lu L, Hayashi T, Hope BT, Su TP, Shaham Y. Time-dependent increases in brain-derived neurotrophic factor protein levels within the mesolimbic dopamine system after withdrawal from cocaine: implications for incubation of cocaine craving. J Neurosci. 2003;23:742–747. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00742.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann S. Cognitive and neural mechanisms of emotional memory. Trends Cogn Sci. 2001;5:394–400. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01707-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris GC, Wimmer M, Aston-Jones G. A role for lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons in reward seeking. Nature. 2005;437:556–559. doi: 10.1038/nature04071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans KG, Everitt BJ, Lee JL. Disrupting reconsolidation of conditioned withdrawal memories in the basolateral amygdala reduces suppression of heroin seeking in rats. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12694–12699. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3101-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SE. Addiction: a disease of learning and memory. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1414–1422. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ. Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:565–598. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin XC, Lu YF, Yang XF, Ma L, Li BM. Glucocorticoid receptors in the basolateral nucleus of amygdala are required for postreactivation reconsolidation of auditory fear memory. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:3702–3712. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Pierce RC, Cornish J, Sorg BA. A role for sensitization in craving and relapse in cocaine addiction. J Psychopharmacol. 1998;12:49–53. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korneyev A, Binder L, Bernardis J. Rapid reversible phosphorylation of rat brain tau proteins in response to cold water stress. Neurosci Lett. 1995;191:19–22. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11546-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann S, Piel M, Wolf OT. Impaired memory retrieval after psychosocial stress in healthy young men. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2977–2982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5139-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Harding S, Watchus W, Juzytsch W, Shalev U, Shaham Y. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in stress-induced relapse to alcohol-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2000;150:317–324. doi: 10.1007/s002130000411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JL, Di Ciano P, Thomas KL, Everitt BJ. Disrupting reconsolidation of drug memories reduces cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuron. 2005;47:795–801. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JL, Milton AL, Everitt BJ. Cue-induced cocaine seeking and relapse are reduced by disruption of drug memory reconsolidation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5881–5887. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0323-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshner AI. Addiction is a brain disease, and it matters. Science. 1997;278:45–47. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loscertales M, Rose SP, Daisley JN, Sandi C. Piracetam facilitates long-term memory for a passive avoidance task in chicks through a mechanism that requires a brain corticosteroid action. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:2238–2243. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Shepard JD, Hall FS, Shaham Y. Effect of environmental stressors on opiate and psychostimulant reinforcement, reinstatement and discrimination in rats: a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:457–491. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Dempsey J, Shaham Y, Hope BT. Differential long-term neuroadaptations of glutamate receptors in the basolateral and central amygdala after withdrawal from cocaine self-administration in rats. J Neurochem. 2005a;94:161–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Hope BT, Dempsey J, Liu SY, Bossert JM, Shaham Y. Central amygdala ERK signaling pathway is critical to incubation of cocaine craving. Nat Neurosci. 2005b;8:212–219. doi: 10.1038/nn1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Koya E, Zhai H, Hope BT, Shaham Y. Role of ERK in cocaine addiction. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:695–703. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, McEwen BS. The acute effects of corticosteroids on cognition: integration of animal and human model studies. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;24:1–27. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroun M, Akirav I. Arousal and stress effects on consolidation and reconsolidation of recognition memory. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:394–405. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh JL. Memory consolidation and the amygdala: a systems perspective. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:456. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh JL, Roozendaal B. Role of adrenal stress hormones in forming lasting memories in the brain. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:205–210. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milekic MH, Alberini CM. Temporally graded requirement for protein synthesis following memory reactivation. Neuron. 2002;36:521–525. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00976-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milekic MH, Brown SD, Castellini C, Alberini CM. Persistent disruption of an established morphine conditioned place preference. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3010–3020. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4818-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto M, Morita N, Ozawa H, Yokoyama K, Kawata M. Distribution of glucocorticoid receptor immunoreactivity and mRNA in the rat brain: an immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization study. Neurosci Res. 1996;26:235–269. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(96)01105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader K. Memory traces unbound. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:65–72. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(02)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader K, Schafe GE, Le Doux JE. Fear memories require protein synthesis in the amygdala for reconsolidation after retrieval. Nature. 2000;406:722–726. doi: 10.1038/35021052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer JW, Craft S, Hershey T, Askins K, Bardgett ME. Glucocorticoid-induced impairment in declarative memory performance in adult humans. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2047–2053. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-02047.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer JW, Selke G, Melson AK, Hershey T, Craft S, Richards K, Alderson AL. Decreased memory performance in healthy humans induced by stress-level cortisol treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:527–533. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.6.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas A, Munhoz CD, Ferguson D, Campbell L, Sapolsky R. Enhancing cognition after stress with gene therapy. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11637–11643. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3122-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien CP, McLellan AT. Myths about the treatment of addiction. Lancet. 1996;347:237–240. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. Ed 4. London: Academic; 1998. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedreira ME, Maldonado H. Protein synthesis subserves reconsolidation or extinction depending on reminder duration. Neuron. 2003;38:863–869. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00352-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu L, Liu QS, Poo MM. BDNF-dependent synaptic sensitization in midbrain dopamine neurons after cocaine withdrawal. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:605–607. doi: 10.1038/nn1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retana-Marquez S, Bonilla-Jaime H, Vazquez-Palacios G, Dominguez-Salazar E, Martinez-Garcia R, Velazquez-Moctezuma J. Body weight gain and diurnal differences of corticosterone changes in response to acute and chronic stress in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28:207–227. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro Do Couto B, Aguilar MA, Manzanedo C, Rodriguez-Arias M, Armario A, Minarro J. Social stress is as effective as physical stress in reinstating morphine-induced place preference in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;185:459–470. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0345-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MJ, Franklin KB. Central but not peripheral beta-adrenergic antagonism blocks reconsolidation for a morphine place preference. Behav Brain Res. 2007;182:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The psychology and neurobiology of addiction: an incentive-sensitization view. Addiction. 2000;95(Suppl 2):S91–S117. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues SM, Schafe GE, LeDoux JE. Molecular mechanisms underlying emotional learning and memory in the lateral amygdala. Neuron. 2004;44:75–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B. Stress and memory: opposing effects of glucocorticoids on memory consolidation and memory retrieval. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2002;78:578–595. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2002.4080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B. Systems mediating acute glucocorticoid effects on memory consolidation and retrieval. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:1213–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL. Amygdaloid nuclei lesions differentially affect glucocorticoid-induced memory enhancement in an inhibitory avoidance task. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1996;65:1–8. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1996.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL. Glucocorticoid receptor agonist and antagonist administration into the basolateral but not central amygdala modulates memory storage. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1997;67:176–179. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1996.3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, Williams CL, McGaugh JL. Glucocorticoid receptor activation in the rat nucleus of the solitary tract facilitates memory consolidation: involvement of the basolateral amygdala. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:1317–1323. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, Quirarte GL, McGaugh JL. Glucocorticoids interact with the basolateral amygdala beta-adrenoceptor–cAMP/cAMP/PKA system in influencing memory consolidation. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15:553–560. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandi C, Loscertales M, Guaza C. Experience-dependent facilitating effect of corticosterone on spatial memory formation in the water maze. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:637–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sara SJ. Retrieval and reconsolidation: toward a neurobiology of remembering. Learn Mem. 2000;7:73–84. doi: 10.1101/lm.7.2.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Stewart J. Stress reinstates heroin-seeking in drug-free animals: an effect mimicking heroin, not withdrawal. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;119:334–341. doi: 10.1007/BF02246300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Funk D, Erb S, Brown TJ, Walker CD, Stewart J. Corticotropin-releasing factor, but not corticosterone, is involved in stress-induced relapse to heroin-seeking in rats. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2605–2614. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02605.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Erb S, Stewart J. Stress-induced relapse to heroin and cocaine seeking in rats: a review. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;33:13–33. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Shalev U, Lu L, De Wit H, Stewart J. The reinstatement model of drug relapse: history, methodology and major findings. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:3–20. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;158:343–359. doi: 10.1007/s002130100917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soravia LM, Heinrichs M, Aerni A, Maroni C, Schelling G, Ehlert U, Roozendaal B, de Quervain DJ. Glucocorticoids reduce phobic fear in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5585–5590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509184103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. Pathways to relapse: the neurobiology of drug- and stress-induced relapse to drug-taking. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2000;25:125–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. Stress and relapse to drug seeking: studies in laboratory animals shed light on mechanisms and sources of long-term vulnerability. Am J Addict. 2003;12:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Josselyn SA, Frankland PW, Masushige S, Silva AJ, Kida S. Memory reconsolidation and extinction have distinct temporal and biochemical signatures. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4787–4795. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5491-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronson NC, Taylor JR. Molecular mechanisms of memory reconsolidation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:262–275. doi: 10.1038/nrn2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronson NC, Wiseman SL, Olausson P, Taylor JR. Bidirectional behavioral plasticity of memory reconsolidation depends on amygdalar protein kinase A. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:167–169. doi: 10.1038/nn1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Corbille AG, Bertran-Gonzalez J, Herve D, Girault JA. Inhibition of ERK pathway or protein synthesis during reexposure to drugs of abuse erases previously learned place preference. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006a;103:2932–2937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511030103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Aubier B, Corbille AG, Brami-Cherrier K, Caboche J, Topilko P, Girault JA, Herve D. Plasticity-associated gene Krox24/Zif268 is required for long-lasting behavioral effects of cocaine. J Neurosci. 2006b;26:4956–4960. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4601-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Fang Q, Liu Z, Lu L. Region-specific effects of brain corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 1 blockade on footshock-stress- or drug-priming-induced reinstatement of morphine conditioned place preference in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;185:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0262-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss F. Neurobiology of craving, conditioned reward and relapse. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2005;5:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White NM. Addictive drugs as reinforcers: multiple partial actions on memory systems. Addiction. 1996;91:921–949. discussion 951–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai HF, Zhang ZY, Zhao M, Qiu Y, Ghitza UE, Lu L. Conditioned drug reward enhances subsequent spatial learning and memory in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;195:193–201. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0893-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Zhang ZY, Zhai HF, Qiu Y, Lu L. Effects of stress during reactivation on rewarding memory. NeuroReport. 2007;18:1153–1156. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3281ac212e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]