Abstract

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) (“Ecstasy”) produces neurotoxic effects, which result into an impairment of learning and memory and other neurological dysfunctions. We examined whether MDMA induces increases in tau protein phosphorylation, which are typically associated with Alzheimer's disease and other chronic neurodegenerative disorders. We injected mice with MDMA at cumulative doses of 10–50 mg/kg intraperitoneally, which are approximately equivalent to doses generally consumed by humans. MDMA enhanced the formation of reactive oxygen species and induced reactive gliosis in the hippocampus, without histological evidence of neuronal loss. An acute or 6 d treatment with MDMA increased tau protein phosphorylation in the hippocampus, revealed by both anti-phospho(Ser404)-tau and paired helical filament-1 antibodies. This increase was restricted to the CA2/CA3 subfields and lasted 1 and 7 d after acute and repeated MDMA treatment, respectively. Tau protein was phosphorylated as a result of two nonredundant mechanisms: (1) inhibition of the canonical Wnt (wingless-type MMTV integration site family) pathway, with ensuing activation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β; and (2) activation of type-5 cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk5). MDMA induced the expression of the Wnt antagonist, Dickkopf-1, and the expression of the Cdk5-activating protein, p25. In addition, the increase in tau phosphorylation was attenuated by strategies that rescued the Wnt pathway or inhibited Cdk5. Finally, an impairment in hippocampus-dependent spatial learning was induced by doses of MDMA that increased tau phosphorylation, although the impairment outlasted this biochemical event. We conclude that tau hyperphosphorylation in the hippocampus may contribute to the impairment of learning and memory associated with MDMA abuse.

Keywords: MDMA, tau phosphorylation, dickkopf-1, Cdk5, hippocampus, neurotoxicity

Introduction

Abuse of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) (“Ecstasy”) is associated with severe neurologic and psychiatric adverse events, which, in part, are related to drug-induced neurotoxicity (for review, see Lyles and Cadet, 2003; Cadet et al., 2007). MDMA is toxic to central serotonergic neurons in humans (McCann et al., 1998), nonhuman primates (Green et al., 2003), and rats (Stone et al., 1987; Johnson et al., 1993; Yeh et al., 1999) (but see Baumann et al., 2007), whereas it damages nigrostriatal and mesolimbic dopaminergic pathways in mice (Stone et al., 1987; Cadet et al., 1994, 1995; O'Callaghan and Miller, 1994; Mann et al., 1997; Logan et al., 1998; Colado et al., 2001; O'Shea et al., 2001). Evidence for MDMA neurotoxicity have also been reported in rodent hippocampus (Stone et al., 1987; Elayan et al., 1992; Sanchez et al., 2004; Miranda et al., 2007) and cerebral cortex (Colado et al., 1999; Sanchez et al., 2004; O'Shea et al., 2005; Capela et al., 2007). The toxic action of MDMA in mice usually requires acute doses >15–20 mg/kg and is mediated inter alia by hyperthermia, excitotoxicity, and formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Cadet et al., 1994, 1995, 2001; Cerruti et al., 1995; Jayanthi et al., 1999; Esteban et al., 2001)

The evidence that MDMA induces electroencephalographic (EEG) abnormalities (Dafters et al., 1999; Gamma et al., 2000) and a long-term impairment of retrospective explicit memory (Zakzanis and Young, 2001; Zakzanis and Campbell, 2006) in both continued and abstinent MDMA users calls for a more in-depth analysis for the potential pathways involved in MDMA-induced cognitive dysfunction. There is evidence for a memory-related hippocampal dysfunction in MDMA users. Functional magnetic resonance imaging in polyvalent MDMA users shows that activity related to retrieved face-profession associations from episodic memory is more spatially restricted in the left hippocampus than in matched controls (Daumann et al., 2005). In addition, MDMA users with prolonged reaction times in selective and divided attention tests fail to activate the left hippocampus normally during high verbal working memory load (Jacobsen et al., 2004).

In rodents, repetitive doses of MDMA produce oxidative stress, DNA single- and double-strand breaks, and long-lasting metabolic changes in the hippocampus, associated with an increased susceptibility to limbic seizures (Frenzilli et al., 2007). The EEG changes induced by MDMA in mice are also consistent with a long-lasting increase in limbic excitability (Giorgi et al., 2005). Together, these findings suggest that limbic neurons might be preferentially targeted by MDMA. Because cognitive dysfunctions described in MDMA users are reminiscent of those found in patients affected by degenerative dementia, we examined whether MDMA induces biochemical changes that are typically associated with the development of chronic dementia, focusing on tau protein phosphorylation. We extended the analysis to glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) and type-5 cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk5), which are the two major enzymes involved in tau protein phosphorylation (Yamaguchi et al., 1996; Pei et al., 1997, 1998, 1999).

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Male C57BL/6 mice, C3H mice (Charles River, Calco, Italy) or mutant mice homozygous for a hypomorphic allele of Dickkopf-1 (Dkk-1) (doubleridge mice) (kindly provided by Miriam H. Meisler, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI), 10 weeks old, weighing 22–24 g were used. Doubleridge mice are insertional mutant mice lacking a transcriptional enhancer in the Dkk-1 gene (Adamska et al., 2003; MacDonald et al., 2004). All mice were kept under environmentally controlled conditions (room temperature, 22°C; humidity, 40%) on a 12 h light/dark cycle with food and water ad libitum. Experiments were performed following the Guidelines for Animal Care and Use of the National Institutes of Health.

Dose regimens of MDMA in mice.

Mice were either acutely or repeatedly injected with MDMA. Acute treatment consisted of two consecutive intraperitoneal doses of 25 mg/kg racemic MDMA hydrochloride (injected with 2 h of interval). The cumulative dose of 50 mg/kg corresponds to 42 mg/kg MDMA free base. Alternatively, mice were treated for 6 d with a cumulative dose of 10 or 30 mg · kg−1 · d−1 MDMA hydrochloride (corresponding to 8.4 and 25.3 mg/kg MDMA free base, respectively), divided into two consecutive doses of 5 or 15 mg · kg−1 · d−1. We selected these doses knowing that human abusers take from 80 to 250 mg MDMA per day and that equivalent parentheral doses in experimental animals can be calculated according the relationship Dhuman = Danimal (Whuman/Wanimal)0.7, where D is the dose of drug in milligrams, and W is the body weight in kilograms (Green et al., 2003). According to this relationship, the doses selected in mice are approximately equivalent to an acute dose of 217 mg or to daily doses of 65 or 130 mg in a 70 kg human.

Experimental design.

C57BL/6 mice underwent an acute MDMA treatment (two intraperitoneal injections of racemic MDMA hydrochloride of 25 mg/kg, with 2 h of interval, cumulative dose of 50 mg/kg, corresponding to 42 mg/kg MDMA free base) or a 6 d MDMA treatment (two intraperitoneal daily injections of racemic MDMA hydrochloride of 5 or 15 mg/kg with 2 h of interval, cumulative dose of 10 or 30 mg/kg, corresponding to 8.43 or 25.3 mg/kg MDMA free base, for 6 d). Control mice were injected with saline (n = 6 for each experimental group). Mice were killed by decapitation at 1, 3, 7, 45, or 90 d after MDMA treatments. In another set of experiments, acute MDMA treatment (two intraperitoneal injections of 25 mg/kg, with 2 h of interval) was performed in Dkk-1 hypomorphic mice (doubleridge mice; n = 6) using C3H mice as wild-type controls. Control mice were injected with saline. Doubleridge and C3H mice were killed by decapitation 1 d after MDMA or saline injection.

Finally, an acute MDMA treatment (two intraperitoneal injections of 25 mg/kg, with 2 h of interval) was performed in mice pretreated with lithium chloride (1 mEq/kg, i.p. every 12 h starting 7 d before the acute MDMA treatment) and/or pretreated with the Cdk5 inhibitor roscovitine (30 nmol/2 μl dissolved in 50% DMSO, i.c.v., twice, 30 min before each MDMA injection). Control mice were injected with saline after a pretreatment with saline (every 12 h starting 7 d before saline treatment) and/or a pretreatment with 50% DMSO (2 μl, i.c.v., 30 min before each injection of saline). Intracerebroventricular injections were performed by a guide cannula implanted under ketamine (100 mg/kg, i.p.) plus xylazine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) anesthesia (coordinates: 0.8 mm posterior to the bregma, 1.4 mm lateral to the midline, 1.0 mm ventral from the surface of skull according to the atlas of Franklin and Paxinos, 1997). All animals (n = 6 for each experimental group) were killed by decapitation 1 d after MDMA or saline injection. Different groups of animals were used for histological/immunohistochemical analysis and biochemical analysis. Dissected brains were fixed in Carnoi and embedded in paraffin. Ten micrometer sections were used for histological/immunohistochemical analysis. Hippocampus and striatum were dissected from different groups of mice, and protein extracts were analyzed by Western blot analysis.

Histology and quantitative analysis.

To evaluate possible degenerating neurons, deparaffinized 10 μm sections were processed for staining with thionin (Nissl staining). After rinses in dH2O, sections were incubated 8 min in thionin. The number of surviving neurons in the pyramidal cell layer was counted by a nonstereological method for the assessment of neuronal density (neurons per cubic millimeter of tissue, Nv) using the following formula: Nv = NA/(t + D), where NA is the number of neurons per square millimeter of tissue, t is the section thickness, and D is the neuron diameter (Abercrombie, 1946). Neurons with a rounded shape similar to those observed in sections from control animals were considered to be viable. We also assessed the presence of degenerating neurons by Fluoro-Jade B staining (Schmued et al., 1997; Schmued and Hopkins, 2000). Deparaffinized sections (10 μm) were incubated for 30 min in a 0.1% (v/v) acetic acid solution containing 0.001% (w/v) Fluoro-Jade B.

To evaluate the presence of DNA fragmentation, deparaffinized 10 μm sections were processed for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated biotinylated UTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining by using the In Situ Cell Death Detection kit, POD (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany).

Immunohistochemistry.

Deparaffinized sections were soaked in 3% hydrogen peroxide to block endogenous peroxidase activity and incubated overnight with monoclonal mouse anti-glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP) antibody (1:400; Sigma, Milan, Italy) and then for 1 h with secondary biotinylated anti-mouse antibodies (1:200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA); rabbit anti-phospho-tau (pSer404) (P-tau) (1:100; Sigma), and then for 1 h with secondary biotinylated anti-rabbit antibodies (1:200; Vector Laboratories); monoclonal mouse anti-paired helical filament (PHF) of tau (PHF-1, 1:100, pSer396 and pSer404; kindly provided by Peter Davies, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, NY) (Greenberg et al., 1992) and then for 1 h with secondary biotinylated anti-mouse antibodies (1:200; Vector Laboratories); rat polyclonal anti-Dkk-1 (1:10; R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and then for 1 h with secondary biotinylated anti-rat antibodies (1:200; Vector Laboratories). For Dkk-1 immunostaining, sections were treated with 10 mm, pH 6.0, citrate buffer, and heated in a microwave for 10 min for antigen retrieval. Control staining was performed without the primary antibodies. The immunoreaction was performed with 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride (ABC Elite kit; Vector Laboratories). P-tau and PHF-tau immunoreactivity was quantified by measuring the relative optical densities of the CA2/CA3 hippocampal subfields in the stained sections using a computer-based microdensitometer (NIH Image software).

Western blot analysis.

Hippocampus or striatum was homogenized at 4°C in ice-cold lysis buffer with a motor-driven Teflon-glass homogenizer (1700 revolutions per minute). Five microliters of homogenates were used for protein determinations. Fifty micrograms of proteins were resuspended in SDS-bromophenol blue reducing buffer and loaded per lane. Western blot analyses were performed using SDS polyacrylamide gels (10% for P-tau and PHF-tau proteins, 15% for Dkk-1 protein, and 12% for p35/p25 and Cdk5 proteins), on a minigel or maxigel apparatus (Mini or Maxi Protean II Cell; Bio-Rad, Milan, Italy). Gels were electroblotted on ImmunBlot Polyvinylidene Difluoride Membrane (Bio-Rad) for 1 h using a semidry electroblotting system (Trans-blot system SD; Bio-Rad), and filters were blocked overnight in TTBS buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl, 0.9% NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20, pH 7.4) containing 5% nonfat dry milk; for phosphorylated proteins, the blocking solution contained 3% BSA and 2% nonfat dry milk. Blots for phosphorylated proteins were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with primary rabbit polyclonal antibody for P-tau (0.5 μg/ml; Oncogene, Cambridge, MA) and with mouse monoclonal antibody anti-PHF-tau (PHF-1 pSer396 and pSer404, 1 μg/ml; kindly provided by Peter Davies, Albert Einstein College of Medicine). Blots for Dkk-1, Cdk5, and p35/25 were incubated overnight at 4°C with the respective antibodies: goat polyclonal Dkk-1 (2 μg/ml; R & D Systems), mouse monoclonal Cdk5 (1 μg/ml; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), and rabbit polyclonal p35/25 (2 μg/ml; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Tebu, France). Blots for mouse monoclonal β-actin (Sigma) were incubated for 1 h at room temperature (1:60,000). Blots for GSK-3β and P-GSK-3β were incubated overnight at 4°C with the respective antibodies: mouse monoclonal GSK-3β (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and rabbit polyclonal P-GSK-3β (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Filters were washed three times with TTBS buffer and then incubated for 1 h with secondary peroxidase-coupled antibodies (anti-rabbit at 1:7000, anti-mouse at 1:7000, or anti-goat at 1:2000; Calbiochem, Milan, Italy).

Immunostaining was revealed by enhanced chemiluminescence luminosity (GE Healthcare, Milan, Italy).

GSK-3β assay.

GSK-3β activity was measured as 32P transfer from [γ-32P]ATP to a peptide substrate by using the GSK-3β Activity Assay kit (Sigma). The kinase was immunoprecipitated from hippocampal protein extracts with an anti-GSK-3β antibody. Assays were performed at room temperature and stopped 8 min later by spotting 20 μl of the mixture onto a P81 phosphocellulose square (spotted in duplicates). The paper was washed three times in 100 mm phosphoric acid and bound radioactivity was quantified by scintillation counting (model SL 3801; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA).

Cdk5 assay.

Tissue lysates containing 500 μg of protein were diluted in lysis buffer to a volume of 500 μl and precleared with 50 μl of Protein A agarose beads (50% slurry in lysis buffer; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 4°C for 2 h. Cdk5 was immunoprecipitated with 5 μg of anti-Cdk5 IgG from precleared lysates by overnight incubation at 4°C, followed by a 3 h incubation at 4°C with 25 μl of Protein A agarose beads. Immunoprecipitates were washed twice with lysis buffer and twice with kinase buffer (20 mm Tris HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 10 μm NaF, and 1 μm Na2VO3) and resuspended in 30 μl of water. Ten microliters of kinase assay mixture [100 mm Tris HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mm MgCl2, 5 mm EDTA, 50 μm NaF, 5 μm Na2VO3, 5 mm DTT, and 50 μm NF-H peptide (VKSPAKEKAKSPVK; Sigma Genosys, Milan, Italy)] were added to 30 μl of the immunoprecipitates. Kinase assays were performed at 30°C for 60 min by adding 5 μCi [γ32P]ATP (specific activity, 3 Ci/mmol, GE Healthcare). The specificity of Cdk5 activity was assessed in the presence of roscovitine (10 μm). The reaction was stopped by adding a similar volume of 10% trichloroacetic acid. Twenty microliters of reaction mixture were transferred onto P81 phosphocellulose squares (spotted in duplicates), air dried, and washed five times for 15 min each in 75 mm phosphoric acid and once in 95% ethanol. Air-dried strips were transferred to vials and counted in a scintillation counter.

Microdialysis in freely moving mice.

Male C57BL/6 mice, 10 weeks old (Charles River), weighing 22–24 g, were used to measure the production of free radicals in the hippocampus, striatum, and cerebral cortex of freely moving mice by microdialysis after systemic injection of MDMA. Mice were implanted with microdialysis intracerebral guides (CMA/7 guide cannula; CMA/Microdialysis, Stockholm, Sweden), under ketamine (100 mg/kg, i.p.) plus xylazine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) anesthesia, in a Kopf stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). The site of implantation was the left hippocampus (coordinates: 3.0 mm posterior to the bregma, 2.8 mm lateral to the midline, 2.0–4.0 mm ventral from the surface of skull), the left striatum (coordinates: 0.6 mm anterior to the bregma, 1.7 mm lateral to the midline, 2.5–4.5 mm ventral from the surface of skull), or the cerebral cortex (coordinates: 1.8 mm anterior to the bregma, 2.2 mm lateral to the midline, 1.8–3.8 mm ventral from the surface of skull), according to the atlas of Franklin and Paxinos (1997). After surgery, mice were housed in separate cages in a temperature-controlled environment on a 12 h light/dark cycle, with access to water and food ad libitum, and allowed to recover for 4 d before the experiment. On the evening before the experiment, a probe was inserted into the intracerebral guide, after removing a dummy, and mice were transferred to a plastic bowl cage with a moving arm (CMA/120 System for Freely-Moving Animals; CMA/Microdialysis) with access to water and food ad libitum. Concentric vertical microdialysis probes 2 mm long and 0.24 mm in outer diameter having a cuprophane membrane with a molecular cutoff of 6000 Da (CMA/7 Microdialysis Probe; CMA/Microdialysis) were used. The probes were perfused continuously with artificial CSF (ACSF), at a flow rate of 1.5 μl/min, using a microinjection pump (Bioanalytical Systems, West Lafayette, IN). The ACSF contained the following (in mm): 150 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.7 CaCl2, and 0.9 MgCl2. This solution was not buffered, and the pH was tipically 6.5. On the following morning, 30 μl (20 min) of consecutive perfusate sample fractions were continuously collected by a fraction collector (CMA/142 Microfraction Collector; CMA/Microdialysis). After three sample fractions, used to determine the basal levels of ROS, mice received two injections of MDMA (25 mg/kg, i.p., 2 h apart), and sample fractions were collected for the following 2 h, after injection of MDMA. Formation of ROS was examined by monitoring 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (2,3-DHBA), a product of the reaction of salycilate (5 mm, added to ACSF) with hydroxyl radicals. Analysis of 2,3-DHBA was performed by HPLC with electrochemical detection. Twenty microliters of the perfusate were injected into an HPLC equipped with an autosampler 507 (Beckman Coulter), a programmable solvent module 126 (Beckman Coulter), an analytical C18 reverse-phase column kept at 30°C (Ultrasphere ODS 5 μm, 80 Å pore, 250 × 4.6 mm; Beckman Coulter), and a Coulochem II electrochemical detector (ESA, Chelmsford, MA). The holding potentials were set at +350 and −350 mV for the detection of 2,3-DHBA. The mobile phase consisted of 80 mm sodium phosphate, 40 mm citric acid, 0.4 mm EDTA, 3 mm 1-heptansulphonic acid, and 12.5% methanol, brought to pH 2.75 with phosphoric acid (run under isocratic conditions, at 1 ml/min).

Morris water maze test.

The Morris water maze test was performed as described by Morris (1984). The experimental apparatus consisted of a circular water tank (diameter, 97 cm; height, 60 cm) containing water at 24 ± 1°C. The target platform (diameter, 10 cm) was submerged 1 cm below the water surface and placed at the midpoint of one quadrant. The platform was located in a fixed position, equidistant from the center and the wall of the pool. The pool was located in a test room containing various prominent visual cues. The acquisition training sessions were performed either 7 or 40 d after a 6 d treatment with MDMA (10 or 30 mg · kg−1 · d−1). Each mouse was submitted to a daily session comprising five trials over 4 successive days during which the animals were left in the tank facing the wall and allowed to swim freely to the escape platform. If an animal did not find the platform within a period of 60 s, it was gently guided to it. The animal was allowed to remain on the platform for 20 s after reaching it. The starting points varied in a pseudorandomized manner. The probe trial was performed by removing the platform from the pool and allowing each mouse to swim for 60 s in the maze. The time spent in a smaller region near to the point where the platform was located was recorded on a videotape by an observer who was unaware of the treatments.

Results

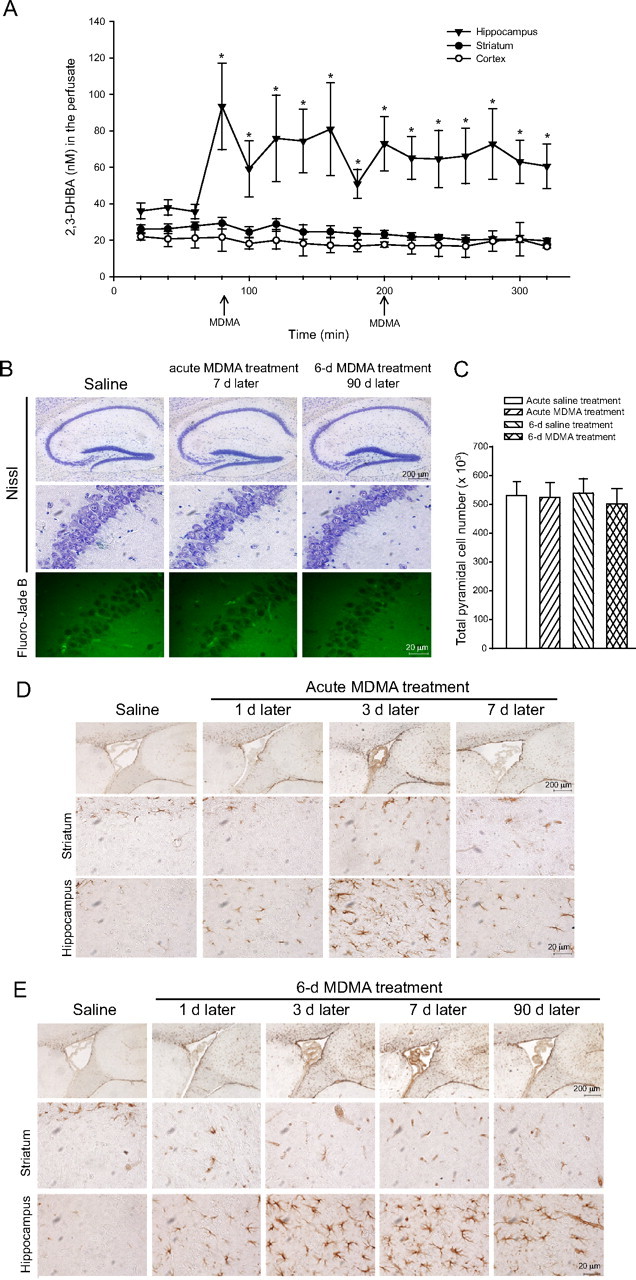

Treatment with MDMA enhanced the formation of ROS but did not cause neuronal death in the hippocampus

We assessed the formation of ROS in freely moving mice treated with MDMA by measuring the production of 2,3-DHBA from salicylic acid added in the perfusate. Treatment with MDMA (two consecutive doses of 25 mg/kg, i.p.) substantially increased ROS formation in the hippocampus but, unexpectedly, had no effect in the striatum or cerebral cortex (Fig. 1A). We next examined whether MDMA treatment caused neuronal death in mice. Mice were assessed for neuronal death by either Nissl or Fluoro-Jade B staining 7 d after an acute treatment with MDMA (cumulative dose of 50 mg/kg) or 7 d after a 6 d treatment with MDMA (cumulative dose of 30 mg · kg−1 · d−1, i.p.). No neuronal loss could be detected after acute or repeated injections of MDMA in the hippocampus (Fig. 1B,C), as well as in the striatum or cerebral cortex (data not shown). In addition, we did not find degenerating cells stained with Fluoro-Jade B in hippocampus (Fig. 1B) and in all microscopic fields examined (data not shown). No neuronal loss was seen at longer times (45 or 90 d) after a 6 d treatment with MDMA (data not shown). We did not find neurons bearing DNA fragmentation in the hippocampus, as assessed by TUNEL staining. In contrast, we consistently found reactive gliosis in the hippocampus of mice treated with MDMA. Reactive gliosis in the hippocampus was transient after an acute treatment with MDMA but lasted up to 90 d after a 6 d treatment with MDMA. No reactive gliosis was ever found in the striatum (Fig. 1D,E).

Figure 1.

Hippocampal toxicity induced by MDMA in mice. A, Assessment of ROS formation in the hippocampus, striatum, and cerebral cortex of freely moving mice injected twice intraperitoneally with 25 mg/kg MDMA (arrows). Values are means ± SEM of five to seven determinations. *p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA and Fisher's PLSD) versus values obtained before MDMA injection in the hippocampus. B, Lack of neuronal loss in the hippocampus of mice after an acute treatment (cumulative dose, 50 mg/kg., i.p.) or a 6 d treatment (30 mg/kg, i.p., once a day) with MDMA. The corresponding control groups were treated with saline. Nissl and Fluoro-Jade B staining were performed 7 d after the last injection of acute MDMA treatment, 90 d after 6 d MDMA treatment or saline. Counts of pyramidal cells in the whole hippocampus are shown in C, where values are means ± SEM of five mice per group. Reactive astrocytes in the hippocampus and striatum of mice treated with MDMA (see above) are shown in D and E, respectively. GFAP immunostaining was performed at the indicated days after the last injection of MDMA. The top horizontal lanes in D and E show the border between hippocampus and striatum around the lateral ventricle in a sagittal section. No reactive gliosis was ever found in mice treated with saline. Examples of mice killed 7 d after the last injection of saline are shown.

Induction of tau protein phosphorylation by MDMA in mice

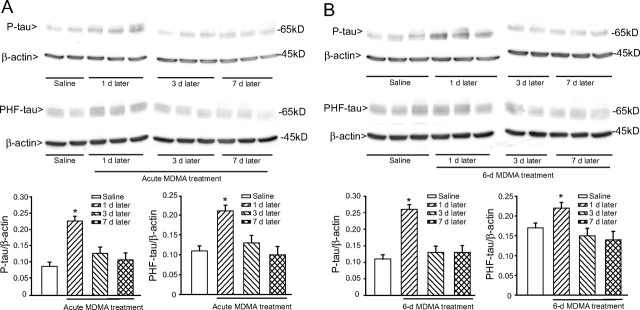

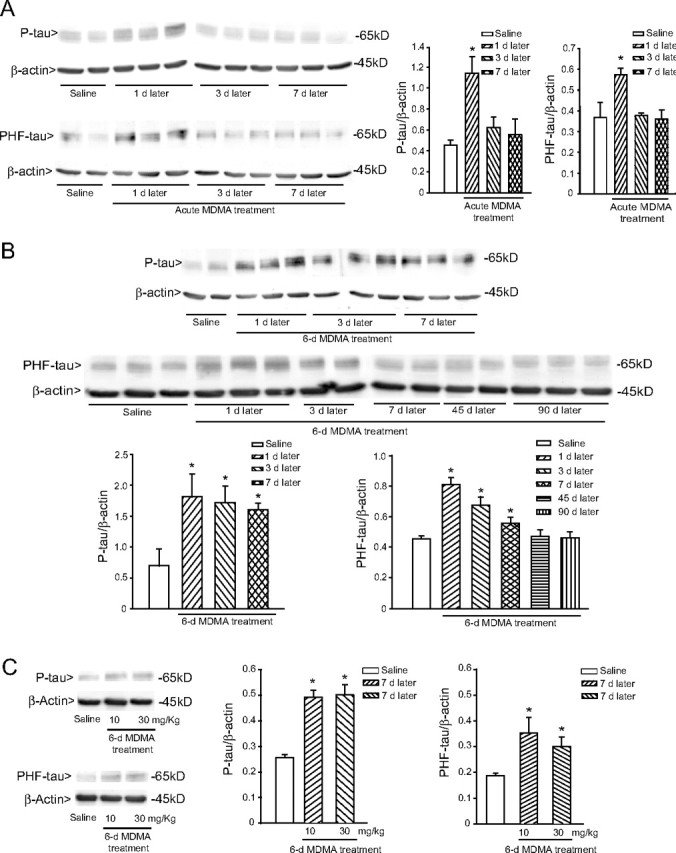

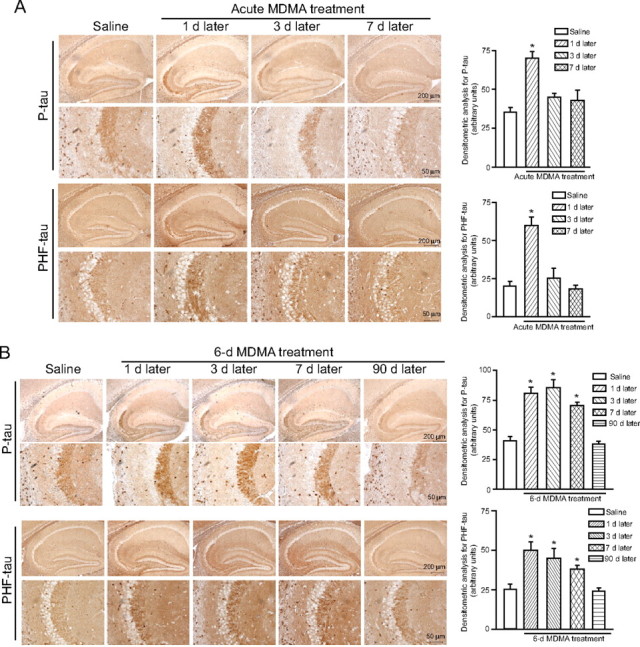

We performed immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated tau using either a polyclonal antibody detecting tau phosphorylated on Ser404 (P-tau) or the monoclonal PHF-1 antibody detecting tau phosphorylated on Ser396 and Ser404 (PHF-tau). An acute treatment with MDMA (cumulative dose of 50 mg/kg) induced a transient increase of both P-tau and PHF-tau levels in the hippocampus, which was detected after 1 d, and declined back to normal after 3 d (Fig. 2A). A 6 d treatment with 30 mg · kg−1 · d−1 MDMA induced an increase in hippocampal P-tau and PHF-tau levels, which was seen at 1, 3, and 7 d but not at 45 or 90 d, after the last administration (Fig. 2B). An increase in PHF-tau levels could be detected 1 week after a 6 d treatment with the lower dose of MDMA (10 mg · kg−1 · d−1) (Fig. 2C). Levels of P-tau or PHF-tau were also increased in the striatum of MDMA-treated mice but only at 1 d after the end of the treatment (Fig. 3A,B). We performed immunohistochemical analysis of P-tau and PHF-tau in the hippocampus of control or MDMA-treated mice. Interestingly, the increase in tau phosphorylation induced by MDMA was restricted to the stratum radiatum of the CA2 region and the stratum lucidum and stratum radiatum of the CA3 region. No increase was found in the pyramidal cell layer of the CA2/CA3 regions or in other hippocampal subfields (Fig. 4A,B). The temporal profile of the increase in P-tau and PHF-tau detected by immunohistochemistry was identical to that detected by immunoblotting after acute or repeated MDMA injections (Fig. 4A,B).

Figure 2.

Transient increase in the hippocampal levels of phosphorylated tau protein induced by MDMA in mice. A, B, Time-dependent increase in tau phosphorylation, as assessed by immunoblot analysis with P-tau and PHF-tau antibodies in mice receiving an acute treatment intraperitoneally with 50 mg/kg MDMA (A) or a 6 d treatment intraperitoneally with 30 mg · kg−1 · d−1 MDMA (B). Mice were killed at the indicated days after the last MDMA injection. Control values refer to mice killed 7 d after the last injection of saline. Saline injection had no effect on P-tau or PHF-tau at any time (data not shown). C, Immunoblot analysis of P-tau and PHF-tau levels in the hippocampus 7 d after a 6 d treatment with 10 or 30 mg · kg−1 · d−1 MDMA. Densitometric values are means ± SEM of five to six individual determinations. *p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA plus Fisher's PLSD) versus mice injected with saline.

Figure 3.

Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated tau protein in the striatum of mice treated with MDMA. Immunoblot analysis of P-tau and PHF-tau levels in the striatum of mice after an acute treatment (cumulative dose, 50 mg/kg., i.p.) or a 6 d treatment (30 mg · kg−1 · d−1, i.p.) with MDMA is shown in A and B, respectively. Mice were killed at the indicated days after the last MDMA injection. Control values refer to mice killed 7 d after the last injection of saline. Densitometric values are means ± SEM of five to six individual determinations. *p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA plus Fisher's PLSD) versus mice injected with saline.

Figure 4.

Transient increase in phosphorylated tau protein induced by MDMA in the mouse hippocampus. Immunohistochemical analysis of P-tau and PHF-tau levels in the hippocampus of mice after an acute treatment intraperitoneally with 50 mg/kg MDMA (A) or a 6 d treatment intraperitoneally with 30 mg · kg−1 · d−1 with MDMA (B). Densitometric analysis of hippocampal P-tau and PHF-tau immunostaining was performed on comparable sections from five to six mice. *p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA plus Fisher's PLSD) versus the respective control mice treated with saline. Note the selective increase in P-tau and PHF-tau in the CA2/CA3 subfields in mice treated with MDMA.

Characterization of the signaling pathways involved in the induction of tau phosphorylation by MDMA

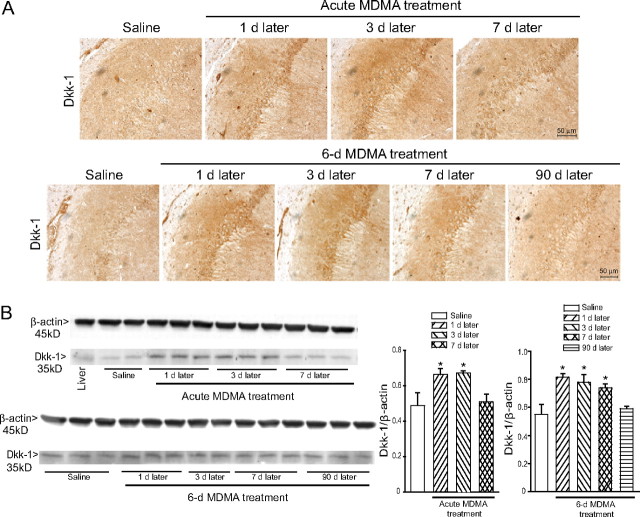

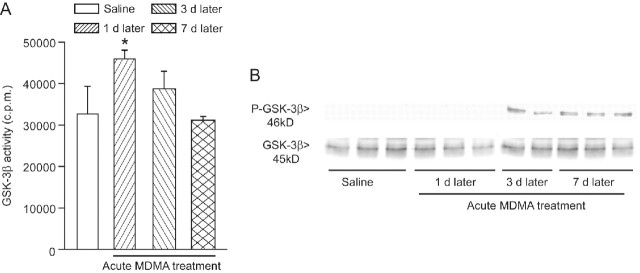

GSK-3β and Cdk5 are the two major enzymes involved in tau protein phosphorylation (Yamaguchi et al., 1996; Pei et al., 1997, 1998, 1999). GSK-3β activity is negatively regulated by the canonical Wnt (wingless-type MMTV integration site family) pathway, which, in turn, is inhibited by the secreted protein Dkk-1. Expression of Dkk-1 has been detected in the Alzheimer's brain and is causally related to tau phosphorylation in cultured neurons challenged with β-amyloid (Caricasole et al., 2004). We found an increased expression of Dkk-1 in the hippocampus at 1 and 3 d after a single injection of MDMA (50 mg/kg) and at 1, 3, and 7 d after a 6 d treatment with 30 mg · kg−1 · d−1 MDMA (Fig. 5A,B). Dkk-1 was preferentially induced in the CA2/CA3 region and was consistently found in the pyramidal cell layer, both intracellularly and extracellularly (Fig. 5A). In the striatum, a slight increase in Dkk-1 expression was exclusively observed in the first 3 d after a 6 d treatment with MDMA (data not shown). Together, these data suggest that MDMA causes a transient inhibition of the canonical Wnt pathway, which follows the induction of Dkk-1. We directly addressed this hypothesis by measuring the activity of GSK-3β in the hippocampus of mice receiving a single injection of MDMA. GSK-3β activity increased 1 d after a single injection of MDMA and returned back to normal at 3 d (Fig. 6A), when Dkk-1 expression was still increased. Interestingly, the levels of Ser9-phosphorylated(inhibited) GSK-3β were found to be increased at 3 and 7 d (but not at 1 d) after a single MDMA injection (Fig. 6B), suggesting a complex time-dependent regulation of GSK-3β activity in response to MDMA.

Figure 5.

Transient induction of the Wnt antagonist Dickkopf-1 (Dkk-1) in the hippocampus of mice treated with MDMA. Immunohistochemical (A) and immunoblot (B) analysis of Dkk-1 in the hippocampus of mice treated with MDMA. Mice received an acute treatment (50 mg/kg., i.p.) or a 6 day treatment (30 mg · kg−1 · d−1) with MDMA and were killed at the indicated days after the last injection. Control values refer to mice killed 7 d after the last injection of saline. Dkk-1 levels did not change at any other time in response to saline. In B, densitometric values are means ± SEM of six determinations. *p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA plus Fisher's PLSD) versus mice injected with saline.

Figure 6.

Transient increase in GSK-3β activity induced by MDMA in the mouse hippocampus. GSK-3β activity (A) and immunoblot analysis of GSK-3β and P-GSK-3β levels (B) in the hippocampus of mice treated with MDMA (acute treatment; cumulative dose, 50 mg/kg, i.p.). Control values refer to mice killed 7 d after an acute injection of saline. Values of counts per minute (c.p.m.) are expressed as means ± SEM of six determinations. *p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA plus Fisher's PLSD) versus control mice. Each lane of the blot is loaded with hippocampal extracts from different mice.

We also examined the expression of Cdk5, its physiological regulator p35, and the p35 cleavage product p25, which causes a sustained activation of Cdk5 (Hisanaga and Saito, 2003). Western blot analysis showed detectable levels of all three proteins in the hippocampus of control mice. The detection of p25 in untreated mice was unexpected because the protein is usually absent under control conditions and is generated from p35 cleavage only under pathological conditions that trigger calpain activity (Patrick et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2000). We found an increase in hippocampal levels of p25, p35, and Cdk5 in mice treated with MDMA. After a single MDMA injection (50 mg/kg), the increase in Cdk5, p35, and p25 levels was substantial at 1 and 3 d and declined at 7 d (supplemental Fig. 1A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). A similar temporal profile was found after a 6 d treatment with 30 mg · kg−1 · d−1 MDMA, although changes in Cdk5 expression were less prominent (supplemental Fig. 1C, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). We also assessed the enzymatic activity of Cdk5 in hippocampal extracts, finding a significant increase at 1 and 3 d, but not at 7 d, after a single MDMA injection (supplemental Fig. 1B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material).

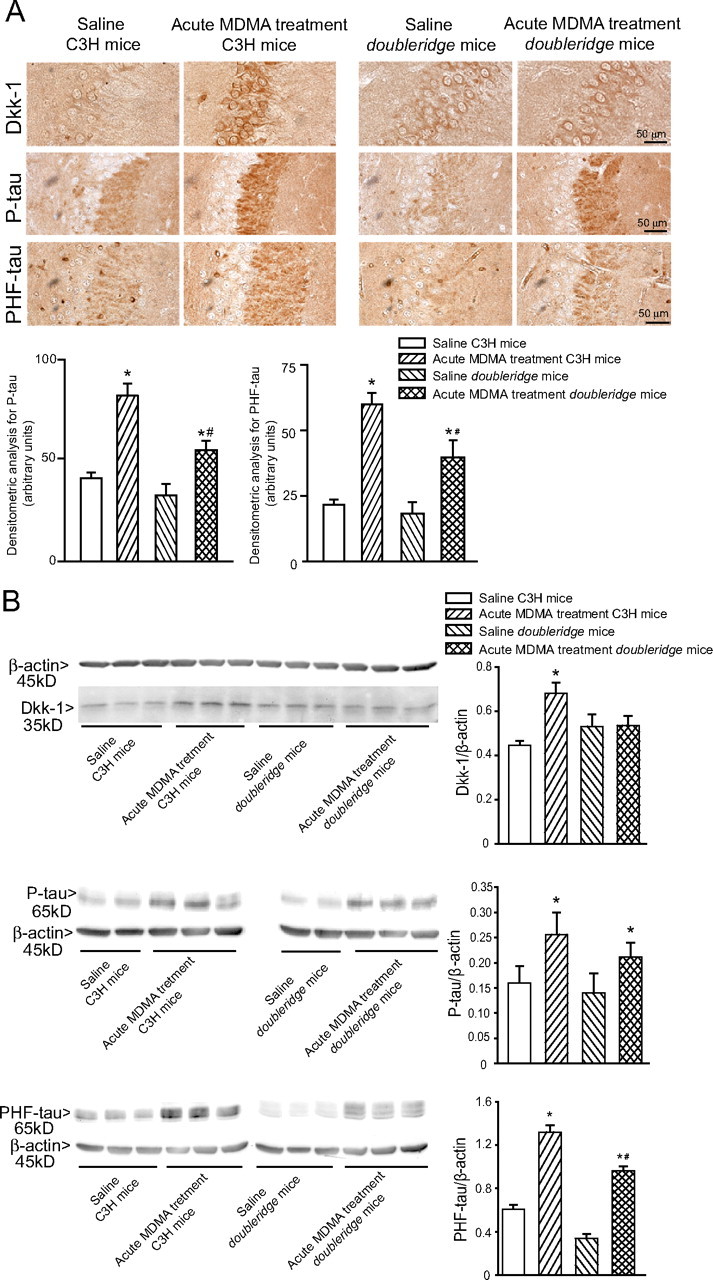

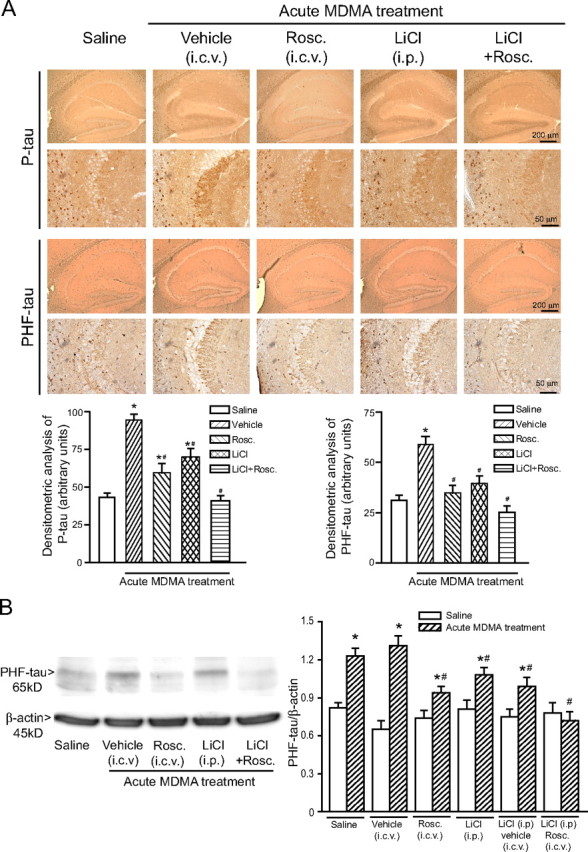

Finally, we examined the causal relationship between Dkk-1-dependent Wnt inhibition or Cdk5 activation and tau phosphorylation in response to MDMA. We used doubleridge mice, which are insertional mutant mice lacking a transcriptional enhancer in the Dkk-1 gene (Adamska et al., 2003; MacDonald et al., 2004). These mice showed a normal constitutive expression of Dkk-1 in the hippocampus but a blunted Dkk-1 expression in response to MDMA compared with C3H control mice (Fig. 7A,B). A single injection of MDMA induced a lower increase in P-tau and PHF-tau levels in the hippocampus of doubleridge mice (Fig. 7A,B). We also treated C57BL/6 mice with the Cdk5 inhibitor roscovitine and/or with lithium ions, which inhibit GSK-3β and therefore rescue the canonical Wnt pathway from the Dkk-1 blockade. Roscovitine was injected intracerebroventricularly at the dose of 30 nmol/2 μl twice, 30 min before each of the two consecutive injections of MDMA. Lithium ions were injected intraperitoneally (as LiCl, 1 mEq/kg every 12 h) in the 7 d preceding MDMA injection. Treatment with roscovitine or lithium alone reduced the increase in both P-tau and PHF-tau levels induced by MDMA, although roscovitine was more effective than lithium. A combined treatment with roscovitine and lithium completely abolished the increase in tau phosphorylation induced by an acute treatment with MDMA in the hippocampus (Fig. 8A,B). Together, these data indicate that the increase in tau protein phosphorylation induced by MDMA in the hippocampus is mediated by Cdk5 activation combined with the inhibition of the canonical Wnt pathway.

Figure 7.

MDMA induces tau protein phosphorylation to a lesser extent in Dkk-1-deficient mice. Immunohistochemical (A) and immunoblot (B) analysis of Dkk-1, P-tau, and PHF-tau in the hippocampus of wild-type C3H mice and doubleridge mice treated with saline or MDMA (acute treatment of 50 mg/kg, i.p.) and killed 24 h later. In A, densitometric analysis of hippocampal P-tau and PHF-tau immunostaining was performed on comparable sections from five to six mice. In B, values are means ± SEM of six determinations. In A and B, p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA plus Fisher's PLSD) versus the respective control mice treated with saline (*) or versus the respective groups of wild-type mice treated with MDMA (#).

Figure 8.

Drugs that rescue the canonical Wnt pathway or inhibit Cdk5 reduce tau protein phosphorylation in the hippocampus of MDMA-treated mice. Immunohistochemical analysis of P-tau and PHF-tau (A) and immunoblot analysis of PHF-tau (B) in the hippocampus of C57BL/6 mice treated with saline or MDMA (acute treatment of 50 mg/kg, i.p.) alone or combined with lithium ions and/or roscovitine (Rosc). Lithium ions were injected intraperitoneally as LiCl, at the dose of 1 mEq/kg twice a day, starting 7 d before MDMA or saline injection. Roscovitine was injected intracerebroventricular at the dose of 30 nmol/2 μl, twice, 30 min before each of the two consecutive injections of saline or MDMA. Vehicle refers to the solution used for the injection of roscovitine (saline containing 50% DMSO). Mice were killed 24 h after saline or MDMA injection. Treatment with LiCl or roscovitine had no effect on P-tau or PHF-tau levels in mice treated with saline (data not shown). Densitometric analysis of hippocampal P-tau and PHF-tau immunostaining was performed on comparable sections from five to six mice. In B, values are means ± SEM of six determinations. p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA plus Fisher's PLSD) versus control mice treated with saline (*) or versus mice treated with MDMA alone (#).

Assessment of spatial learning

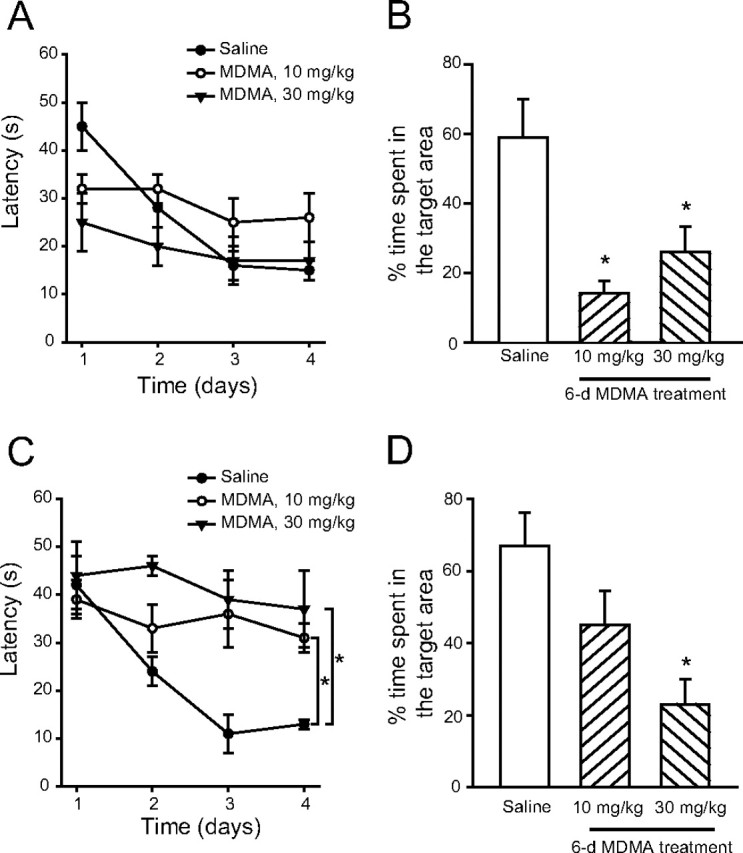

Spatial learning was assessed by the Morris water maze in mice injected daily for 6 d with saline or MDMA (10 or 30 mg/kg), 7 or 40 d after the last injection. At 7 d, mice treated with saline learned the task, as demonstrated by a significant day effect for latency (Fig. 9A). Data of MDMA-treated mice were confounded by a higher speed of these mice in the maze on day 1 of training (data not shown), which accounted for their lower latency in finding the platform (Fig. 9A). This is in agreement with the finding that mice repeatedly injected with MDMA develop a progressive hypermotility that outlasts the end of the treatment for several days (Frenzilli et al., 2007). MDMA-treated mice showed a learning deficit in the probe trial, spending less time in the target region after removal of the platform (Fig. 9B). At 40 d after treatment, when all groups of mice performed similarly on the first day of acquisition, MDMA-treated mice showed a learning deficit in the acquisition phase, with no significant difference between the two doses of the drug (Fig. 9C). Mice treated with 30 mg · kg−1 · d−1 MDMA also showed a significant learning impairment in the probe trial (Fig. 9D).

Figure 9.

Impairment of spatial learning induced by MDMA in mice. Impairment of spatial learning induced by a 6 d treatment with MDMA at a cumulative daily dose of 10 or 30 mg/kg, i.p. Spatial learning was assessed using the Morris water maze 7 d (A, B) or 40 d (C, D) after the last injection of MDMA or saline. A, C, Latencies in the acquisition phase learning; B, D, percentage time spent in the target region during probe trials. Values are means ± SEM of six mice per group. In C, *p < 0.05 (F(4,39) = 15.83 for MDMA at 10 mg/kg and 21.78 for MDMA at 30 mg/kg, two-way repeated-measures ANOVA) versus control mice treated with saline; in B and D, *p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA plus Fisher's PLSD) versus control mice.

Discussion

Systemically injected MDMA in mice induced a transient increase in tau protein phosphorylation in the hippocampus, at doses that are approximately equivalent to those abused by humans (Green et al., 2003). Tau hyperphosphorylation was associated with a transient increase in the activity of GSK-3β and Cdk5, two enzymes that phosphorylate tau protein at multiple sites, including those (Ser396 and Ser404) that are recognized by PHF-1 antibodies (Gong et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2006a; Sengupta et al., 2006). Multiple intracellular pathways converge to regulate GSK-3β activity, including the canonical Wnt pathway. Interaction of Wnt glycoproteins with the membrane receptors Frizzled and LRP5/6 (low-density lipoprotein-receptor related proteins 5 and 6) inhibits the activity of GSK-3β by dissociating the enzyme from a multiprotein complex containing axin, adenomatous polyposis coli, and β-catenin (Hinck et al., 1994; Aberle et al., 1997; Willert and Nusse, 1998). MDMA induced the expression of Dkk-1, a secreted Wnt inhibitor (for review, see Niehrs, 2006), which is causally related to tau phosphorylation and neuronal damage in in vitro and in vivo models of neurodegenerative disorders (Caricasole et al., 2004; Cappuccio et al., 2005; Busceti et al., 2007). The dkk-1 gene is induced by the tumor-suppressing protein p53 (Wang et al., 2000), which is a major sensor of DNA damage in eukaryotic cells (Smith and Seo, 2002; Seo and Jung, 2004). A possible scenario is that MDMA induces the formation of ROS in the hippocampus (Frenzilli et al., 2007; see also present data), leading to DNA damage, p53 expression, Dkk-1 induction, and inhibition of the canonical Wnt/GSK-3β pathway. A role for Dkk-1 in MDMA-induced tau hyperphosphorylation was suggested by data obtained with Dkk-1-defective doubleridge mice or with mice treated with lithium ions, which, iter alia, rescue the Wnt pathway by inhibiting GSK-3β activity (Klein and Melton, 1996). Although GSK-3β is under the control of the canonical Wnt pathway, we found a temporal dissociation between Dkk-1 expression and GSK-3β activity in the hippocampus of MDMA-treated mice: Dkk-1 expression was higher at 1 and 3 d, whereas GSK-3β activity was higher only at 1 d after a single MDMA injection. This might reflect the activation of defensive mechanisms that limit the extent and duration of GSK-3β activation in response to MDMA. Accordingly, MDMA induced a delayed increase in Ser9-phosphorylated(inhibited)–GSK3β levels after 3 and 7 d but not after 1 d. The identity of the pathway that phosphorylates GSK-3β is unknown.

Cdk5 is a nonmitotic cyclin-dependent kinase that has been implicated in mechanisms of neurodegeneration (Patrick et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2000; Patzke and Tsai, 2002; Tseng et al., 2002; Lee and Tsai, 2003). Two related neuron-specific proteins, p35 and p39, are necessary and sufficient to activate Cdk5 on direct binding (Dhavan and Tsai, 2001). p25, which is generated from calpain-dependent p35 cleavage, overactivates Cdk5, causing neuronal damage (Patrick et al., 1999; Nath et al., 2000). Transgenic mice overexpressing p25 exhibit neurodegeneration and tau-associated pathology (Cruz et al., 2003). The increase in Cdk5 activity we found in the hippocampus of MDMA-treated mice was associated with increases in p25, p35, and Cdk5 protein levels. This was unexpected because increases in p25 levels are usually combined with reductions or no changes in p35 levels (Chen et al., 2000; Zhu et al., 2002; Cruz et al., 2003; Kerokoski et al., 2004; Crespo-Biel et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007). It is possible that MDMA treatment induces the expression of p35, which is then partially cleaved into p25. Induction of p35 has been shown in neuroblastoma cells and PC12 cells differentiating in response to retinoic acid and nerve growth factor, respectively. Under both circumstances, p35 induction follows the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway (Harada et al., 2001; Lee and Kim, 2004). Whether MDMA enhances p35 expression through the activation of the MAPK pathway and/or other signaling pathways remains to be established. We examined the role of Cdk5 in tau phosphorylation using roscovitine, a Cdk inhibitor with preferential activity at Cdk5 (Knockaert et al., 2002). In MDMA-treated mice, tau hyperphosphorylation was reduced by roscovitine alone and was abolished when roscovitine was combined with lithium. Thus, Cdk5 activation and inhibition of the canonical Wnt pathway are nonredundant mechanisms that mediate tau hyperphosphorylation in response to MDMA. However, we cannot exclude that these two mechanisms are interdependent because (1) Cdk5 enhances the transcriptional activity of the Dkk-1 inducer p53 in neurons (Wesierska-Gadek et al., 2006); and (2) overactivation of Cdk5 in transgenic mice results into an age-dependent inhibition of GSK-3β activity, which limits tau hyperphosphorylation in these mice (Plattner et al., 2006). The relative impact of these processes to the overall extent of tau hyperphosphorylation in the hippocampus of MDMA-treated mice is unknown.

Hyperphosphorylated tau causes instability of microtubules, leading to neuronal dysfunction (Alonso et al., 1994, 1996, 1997; Alonso Adel et al., 2006), and induction of tau phosphorylation by activation of GSK-3β (Liu et al., 2006b), activation of Cdk5 (Liao et al., 2004), or inhibition of protein phosphatases (Sun et al., 2003) leads to an impairment of spatial memory. In addition, transgenic mice expressing a phosphorylation-prone truncated tau show a deficit in the Morris water maze test, with no changes in spontaneous locomotor activity and no anxiety (Hrnkova et al., 2007). We searched for a correlation between tau hyperphosphorylation and learning impairment using the Morris water maze. Mice exhibited a lower performance in the probe trial, which is the gold standard for assessing hippocampus-dependent spatial learning, 1 week after a 6 d treatment with 10 or 30 mg · kg−1 · d−1 MDMA, when tau protein was hyperphosphorylated in the hippocampus. However, a learning deficit could also be detected 40 d later, when tau hyperphosphorylation was no longer visible. Thus, tau hyperphosphorylation may contribute to, but is not the only determinant of, learning impairment in response to MDMA.

Interestingly, tau hyperphosphorylation was found in the CA2/CA3 regions and not in other hippocampal subfields. There is a high density of serotonergic fibers in the CA3 region (Szyndler et al., 2002; Bjarkam et al., 2003), and a 4 d treatment with neurotoxic doses of MDMA causes a selective upregulation of 5-HT2C (formerly known as 5-HT1C) serotonin receptors in the CA3 region with no changes in other hippocampal subfields (Yau et al., 1994). Thus, the CA3 region might be a preferential target for MDMA because of the anatomical organization of monoaminergic afferent pathways. A dysfunction of CA3 neurons caused by tau hyperphosphorylation and cytoskeletal damage might compromise the transfer of the memory trace from the dentate gyrus to the CA1 region (Gruart et al., 2006), thus contributing to the cognitive impairment induced by MDMA.

In conclusion, we have shown that MDMA treatment in mice enhances tau phosphorylation, a biochemical hallmark of Alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal dementia, and other chronic neurodegenerative disorders characterized by a progressive cognitive decline (Grundke-Iqbal et al., 1986; Iqbal et al., 1989; Lee et al., 1991). This raises additional concern about the potential neurotoxicity of MDMA abuse. There are at least two important issues that remain to be addressed: (1) how is tau hyperphosphorylation related to the primary action of MDMA on dopaminergic or serotonergic axon terminals; and (2) how long is tau hyperphosphorylation lasting in relation to the dose, frequency, and duration of MDMA administration.

Footnotes

We thank Miriam H. Meisler (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI) for kindly providing doubleridge mice and Peter Davies (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, NY) for kindly providing antibody anti-PHF-tau (PHF-1).

References

- Abercrombie, 1946.Abercrombie M. Estimation of nuclear population from microtome sections. Anat Rec. 1946;94:239–247. doi: 10.1002/ar.1090940210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aberle et al., 1997.Aberle H, Bauer A, Stappert J, Kispert A, Kemler R. β-Catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16:3797–3804. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamska et al., 2003.Adamska M, MacDonald BT, Meisler MH. Doubleridge, a mouse mutant with defective compaction of the apical ectodermal ridge and normal dorsal-ventral patterning of the limb. Dev Biol. 2003;255:350–362. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso et al., 1994.Alonso AC, Zaidi T, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Role of abnormally phosphorylated tau in the breakdown of microtubules in Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5562–5566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso et al., 1996.Alonso AC, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Alzheimer's disease hyperphosphorylated tau sequesters normal tau into tangles of filaments and disassembles microtubules. Nat Med. 1996;2:783–787. doi: 10.1038/nm0796-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso et al., 1997.Alonso AD, Grundke-Iqbal I, Barra HS, Iqbal K. Abnormal phosphorylation of tau and the mechanism of Alzheimer neurofibrillary degeneration: sequestration of microtubule-associated proteins 1 and 2 and the disassembly of microtubules by the abnormal tau. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:298–303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso Adel et al., 2006.Alonso Adel C, Li B, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Polymerization of hyperphosphorylated tau into filaments eliminates its inhibitory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8864–8869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603214103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann et al., 2007.Baumann MH, Wang X, Rothman RB. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) neurotoxicity in rats: a reappraisal of past and present findings. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;189:407–424. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0322-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjarkam et al., 2003.Bjarkam CR, Sorensen JC, Geneser FA. Distribution and morphology of serotonin-immunoreactive axons in the hippocampal region of the New Zealand white rabbit. I. Area dentata and hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2003;13:21–37. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busceti et al., 2007.Busceti CL, Biagioni F, Aronica E, Riozzi B, Storto M, Battaglia G, Giorgi FS, Gradini R, Fornai F, Caricasole, Nicoletti F, Bruno V. Induction of the Wnt inhibitor, Dickkopf-1, is associated with neurodegeneration related to temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2007;48:694–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet et al., 1994.Cadet JL, Ladenheim B, Baum I, Carlson E, Epstein C. CuZn-superoxide dismutase (CuZnSOD) transgenic mice show resistance to the lethal effects of methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) and of methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) Brain Res. 1994;655:259–262. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91624-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet et al., 1995.Cadet JL, Ladenheim B, Hirata H, Rothman RB, Ali S, Carlson E, Epstein C, Moran TH. Superoxide radicals mediate the biochemical effects of methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA): evidence from using CuZn-superoxide dismutase transgenic mice. Synapse. 1995;21:169–176. doi: 10.1002/syn.890210210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet et al., 2001.Cadet JL, Thiriet N, Jayanthi S. Involvement of free radicals in MDMA-induced neurotoxicity in mice. Ann Med Interne (Paris) 2001;152(Suppl 3):IS57–IS59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet et al., 2007.Cadet JL, Krasnova IN, Jayanthi S, Lyles J. Neurotoxicity of substituted amphetamines: molecular and cellular mechanisms. Neurotox Res. 2007;11:183–202. doi: 10.1007/BF03033567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capela et al., 2007.Capela JP, Fernandes E, Remião F, Bastos ML, Meisel A, Carvalho F. Ecstasy induces apoptosis via 5-HT(2A)-receptor stimulation in cortical neurons. Neurotoxicology. 2007;28:868–875. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccio et al., 2005.Cappuccio I, Calderone A, Busceti CL, Biagioni F, Pontarelli F, Bruno V, Storto M, Terstappen GT, Gaviraghi G, Fornai F, Battaglia G, Melchiorri D, Zukin RS, Nicoletti F, Caricasole A. Induction of Dickkopf-1, a negative modulator of the Wnt pathway, is required for the development of ischemic neuronal death. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2647–2657. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5230-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caricasole et al., 2004.Caricasole A, Copani A, Caraci F, Aronica E, Rozemuller AJ, Caruso A, Storto M, Gaviraghi G, Terstappen GC, Nicoletti F. Induction of Dickkopf-1, a negative modulator of the Wnt pathway, is associated with neuronal degeneration in Alzheimer's brain. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6021–6027. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1381-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerruti et al., 1995.Cerruti C, Sheng P, Ladenheim B, Epstein CJ, Cadet JL. Involvement of oxidative and l-arginine-NO pathways in the neurotoxicity of drugs of abuse in vitro. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1995;22:381–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1995.tb02025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen et al., 2000.Chen J, Zhang Y, Kelz MB, Steffen C, Ang ES, Zeng L, Nestler EJ. Induction of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 in the hippocampus by chronic electroconvulsive seizures: role of ΔFosB. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8965–8971. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-08965.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colado et al., 1999.Colado MI, Granados R, O'Shea E, Esteban B, Green AR. The acute effect in rats of 3,4-methylenedioxyethamphetamine (MDEA, “eve”) on body temperature and long term degeneration of 5-HT neurones in brain: a comparison with MDMA (“ecstasy”) Pharmacol Toxicol. 1999;84:261–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1999.tb01492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colado et al., 2001.Colado MI, Camarero J, Mechan AO, Sanchez V, Esteban B, Elliott JM, Green AR. A study of the mechanisms involved in the neurotoxic action of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”) on dopamine neurones in mouse brain. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:1711–1723. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Biel et al., 2007.Crespo-Biel N, Camins A, Pelegrí C, Vilaplana J, Pallàs M, Canudas AM. 3-Nitropropionic acid activates calpain/cdk5 pathway in rat striatum. Neurosci Lett. 2007;421:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz et al., 2003.Cruz JC, Tseng HC, Goldman JA, Shih H, Tsai LH. Aberrant Cdk5 activation by p25 triggers pathological events leading to neurodegeneration and neurofibrillary tangles. Neuron. 2003;40:471–483. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00627-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafters et al., 1999.Dafters RI, Duffy F, O'Donnell PJ, Bouquet C. Level of use of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or Ecstasy) in humans correlates with EEG power and coherence. Psychopharmacology. 1999;145:82–90. doi: 10.1007/s002130051035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daumann et al., 2005.Daumann J, Fischermann T, Heekeren K, Henke K, Thron A, Gouzoulis-Mayfrank E. Memory-related hippocampal dysfunction in poly-drug ecstasy (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) users. Psychopharmacology. 2005;180:607–611. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhavan and Tsai, 2001.Dhavan R, Tsai LH. A decade of CDK5. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:749–759. doi: 10.1038/35096019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elayan et al., 1992.Elayan I, Gibb JW, Hanson GR, Foltz RL, Lim HK, Johnson M. Long-term alteration in the central monoaminergic systems of the rat by 2,4,5-trihydroxyamphetamine but not by 2-hydroxy-4,5-methylenedioxymethamphetamine or 2-hydroxy-4,5-methylenedioxyamphetamine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;221:281–288. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90714-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban et al., 2001.Esteban B, O'Shea E, Camarero J, Sanchez V, Green AR, Colado MI. 3,4-Methylendioxymethamphetamine induces monoamine release, but not toxicity, when administered centrally at a concentration occurring following a peripherally injected neurotoxic dose. Psychopharmacology. 2001;154:251–260. doi: 10.1007/s002130000645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin and Paxinos, 1997.Franklin KBJ, Paxinos G. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Ed 2. New York: Academic; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Frenzilli et al., 2007.Frenzilli G, Ferrucci M, Giorgi FS, Blandini F, Nigro M, Ruggieri S, Murri L, Paparelli A, Fornai F. DNA fragmentation and oxidative stress in the hippocampal formation: a bridge between 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy) intake and long-lasting behavioural alterations. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18:471–481. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282d518aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamma et al., 2000.Gamma A, Frei E, Lehmann D, Pascual-Marqui RD, Hell D, Vollenweider FX. Mood state and brain electric activity in ecstasy users. NeuroReport. 2000;11:157–162. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200001170-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi et al., 2005.Giorgi FS, Pizzanelli C, Ferrucci M, Lazzeri G, Faetti M, Giusiani M, Pontarelli F, Busceti CL, Murri L, Fornai F. Previous exposure to (±)3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine produces long-lasting alteration in limbic brain excitability measured by electroencephalogram spectrum analysis, brain metabolism and seizure susceptibility. Neuroscience. 2005;136:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong et al., 2006.Gong CX, Liu F, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Dysregulation of protein phosphorylation/dephosphorylation in Alzheimer's disease: a therapeutic target. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2006;2006:31825. doi: 10.1155/JBB/2006/31825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green et al., 2003.Green AR, Mechan AO, Elliott JM, O'Shea E, Colado MI. The pharmacology and clinical pharmacology of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”) Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55:463–508. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg et al., 1992.Greenberg SG, Davies P, Schein JD, Binder LI. Hydrofluoric acid-treated tau PHF proteins display the same biochemical properties as normal tau. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:564–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruart et al., 2006.Gruart A, Munoz MD, Delgado-Garcia JM. Involvement of the CA3-CA1 synapse in the acquisition of associative learning in behaving mice. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1077–1087. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2834-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundke-Iqbal et al., 1986.Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Tung YC, Quinlan M, Wisniewski HM, Binder LI. Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4913–4917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada et al., 2001.Harada T, Morooka T, Ogawa S, Nishida E. ERK induces p35, a neuron-specific activator of Cdk5, through induction of Egr1. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:453–459. doi: 10.1038/35074516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinck et al., 1994.Hinck L, Nelson WJ, Papkoff J. Wnt-1 modulates cell-cell adhesion in mammalian cells by stabilizing β-catenin binding to the cell adhesion protein cadherin. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:729–741. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.5.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisanaga and Saito, 2003.Hisanaga S, Saito T. The regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 activity through the metabolism of p35 or p39 Cdk5 activator. Neurosignals. 2003;12:221–229. doi: 10.1159/000074624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrnkova et al., 2007.Hrnkova M, Zilka N, Minichova Z, Koson P, Novak M. Neurodegeneration caused by expression of human truncated tau leads to progressive neurobehavioural impairment in transgenic rats. Brain Res. 2007;1130:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.10.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal et al., 1989.Iqbal K, Grundke-Iqbal I, Smith AJ, George L, Tung YC, Zaidi T. Identification and localization of a tau peptide to paired helical filaments of Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5646–5650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen et al., 2004.Jacobsen LK, Mencl WE, Pugh KR, Skudlarski P, Krystal JH. Preliminary evidence of hippocampal dysfunction in adolescent MDMA (“ecstasy”) users: possible relationship to neurotoxic effects. Psychopharmacology. 2004;173:383–390. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1679-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayanthi et al., 1999.Jayanthi S, Ladenheim B, Andrews AM, Cadet JL. Overexpression of human copper/zinc superoxide dismutase in transgenic mice attenuates oxidative stress caused by methylenedioxymethamphetamine (Ecstasy) Neuroscience. 1999;91:1379–1387. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00698-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson et al., 1993.Johnson M, Bush LG, Hanson GR, Gibb JW. Effects of ritanserin on the 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-induced decreasein striatal serotonin concentration and on the increase in striatal neurotens in and dynorphin A concentrations. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;46:770–772. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90568-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerokoski et al., 2004.Kerokoski P, Suuronen T, Salminen A, Soininen H, Pirttilä T. Both N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) and non-NMDA receptors mediate glutamate-induced cleavage of the cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (cdk5) activator p35 in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2004;368:181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein and Melton, 1996.Klein SP, Melton DA. A molecular mechanism for the effect of lithium on development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8455–8459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knockaert et al., 2002.Knockaert M, Greengard P, Meijer L. Pharmacological inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2002;23:417–425. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(02)02071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee and Kim, 2004.Lee JH, Kim KT. Induction of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 and its activator p35 through the extracellular-signal-regulated kinase and protein kinase A pathways during retinoic-acid mediated neuronal differentiation in human neuroblastoma SK-N-BE(2)C cells. J Neurochem. 2004;91:634–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee and Tsai, 2003.Lee MS, Tsai LH. Cdk5: one of the links between senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles? J Alzheimers Dis. 2003;5:127–137. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee et al., 2000.Lee MS, Kwon YT, Li M, Peng J, Friedlander RM, Tsai LH. Neurotoxicity induces cleavage of p35 to p25 by calpain. Nature. 2000;405:360–364. doi: 10.1038/35012636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee et al., 1991.Lee VM, Balin BJ, Otvos L, Jr, Trojanowski JQ. A68: a major subunit of paired helical filaments and derivatized forms of normal Tau. Science. 1991;251:675–678. doi: 10.1126/science.1899488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao et al., 2004.Liao X, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Wang J. The effect of cdk-5 overexpression on tau phosphorylation and spatial memory of rat. Sci China C Life Sci. 2004;47:251–257. doi: 10.1007/BF03182770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu et al., 2006a.Liu F, Liang Z, Shi J, Yin D, El-Akkad E, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Gong CX. PKA modulates GSK-3beta- and cdk5-catalyzed phosphorylation of tau in site- and kinase-specific manners. FEBS Lett. 2006a;580:6269–6274. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu et al., 2006b.Liu SJ, Zhang AH, Li HL, Wang Q, Deng HM, Netzer WJ, Xu H, Wang JZ. Overactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by inhibition of phosphoinositol-3 kinase and protein kinase C leads to hyperphosphorylation of tau and impairment of spatial memory. J Neurochem. 2006b;87:1333–1344. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan et al., 1998.Logan BJ, Laverty R, Sanderson WD, Yee YB. Differences between rats and mice in MDMA (methylendioxynethylamphetamine) neurotoxicity. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;152:227–234. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90717-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles and Cadet, 2003.Lyles J, Cadet JL. Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, Ecstasy) neurotoxicity: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2003;42:155–168. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(03)00173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald et al., 2004.MacDonald BT, Adamska M, Meisler MH. Hypomorphic expression of Dkk1 in the doubleridge mouse: dose dependence and compensatory interactions with Lrp6. Development. 2004;131:2543–2552. doi: 10.1242/dev.01126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann et al., 1997.Mann H, Ladenheim B, Hirata H, Moran TH, Cadet JL. Differential toxic effects of methamphetamine (METH) and methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in multidrug-resistant (mdr1a) knockout mice. Brain Res. 1997;769:340–346. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00754-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann et al., 1998.McCann UD, Szabo Z, Scheffel U, Dannals RF, Ricaurte GA. Positron emission tomographic evidence of toxic effect of MDMA (“Ecstasy”) on brain serotonin neurons in human beings. Lancet. 1998;352:1433–1437. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04329-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda et al., 2007.Miranda M, Bosch-Morell F, Johnsen-Soriano S, Barcia J, Almansa I, Asensio S, Araiz J, Messeguer A, Romero FJ. Oxidative stress in rat retina and hippocampus after chronic MDMA (“ecstasy”) administration. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:1156–1162. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9285-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, 1984.Morris R. Developments of a water-maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. J Neurosci Methods. 1984;11:47–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath et al., 2000.Nath R, Davis M, Probert AW, Kupina NC, Ren X, Schielke GP, Wang KK. Processing of cdk5 activator p35 to its truncated form (p25) by calpain in acutely injured neuronal cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;274:16–21. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehrs, 2006.Niehrs C. Function and biological roles of the Dickkopf family of Wnt modulators. Oncogene. 2006;25:7469–7481. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Callaghan and Miller, 1994.O'Callaghan JP, Miller DB. Neurotoxicity profiles of substituted amphetamines in the C57BL/6J mouse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270:741–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea et al., 2001.O'Shea A, Esteban B, Camarero J, Green AR, Colado MI. Effect of GBR 12909 and fluoxetine on the acute and long term changes induced by MDMA (“ecstasy”) on the 5-HT and dopamine concentrations in mouse brain. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea et al., 2005.O'Shea E, Sanchez V, Orio L, Escobedo I, Green AR, Colado MI. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine increases pro-interleukin-1beta production and caspase-1 protease activity in frontal cortex, but not in hypothalamus, of Dark Agouti rats: role of interleukin-1beta in neurotoxicity. Neuroscience. 2005;135:1095–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick et al., 1999.Patrick GN, Zukerberg L, Nikolic M, de la Monte S, Dikkes P, Tsai LH. Conversion of p35 to p25 deregulates Cdk5 activity and promotes neurodegeneration. Nature. 1999;402:615–622. doi: 10.1038/45159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patzke and Tsai, 2002.Patzke H, Tsai LH. Cdk5 sinks into ALS. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:8–10. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)02000-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei et al., 1997.Pei JJ, Tanaka T, Tung YC, Braak E, Iqbal K, Grundke-Iqbal I. Distribution, levels, and activity of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in the Alzheimer disease brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:70–78. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199701000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei et al., 1998.Pei JJ, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Bogdanovic N, Winblad B, Cowburn RF. Accumulation of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (cdk5) in neurons with early stages of Alzheimer's disease neurofibrillary degeneration. Brain Res. 1998;797:267–277. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei et al., 1999.Pei JJ, Braak E, Braak H, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Winblad B, Cowburn RF. Distribution of active glycogen synthase kinase 3beta (GSK-3beta) in brains staged for Alzheimer disease neurofibrillary changes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:1010–1019. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199909000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plattner et al., 2006.Plattner F, Angelo M, Giese KP. The roles of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 and glycogen synthase kinase 3 in tau hyperphosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25457–25465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603469200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez et al., 2004.Sanchez V, O'Shea E, Saadat KS, Elliott JM, Colado MI, Green AR. Effect of repeated (“binge”) dosing of MDMA to rats housed at normal and high temperature on neurotoxic damage to cerebral 5-HT and dopamine neurones. J Psychopharmacol. 2004;18:412–416. doi: 10.1177/026988110401800312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmued and Hopkins, 2000.Schmued LC, Hopkins KJ. Fluoro-Jade B: a high affinity fluorescent marker for the localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain Res. 2000;874:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmued et al., 1997.Schmued LC, Albertson C, Slikker W., Jr Fluoro-Jade B: a novel fluorochrome for the sensitive and reliable histochemical localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain Res. 1997;751:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01387-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta et al., 2006.Sengupta A, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Regulation of phosphorylation of tau by protein kinases in rat brain. Neurochem Res. 2006;31:1473–1480. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9205-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo and Jung, 2004.Seo YR, Jung HJ. The potential roles of p53 tumor suppressor in nucleotide excision repair (NER) and base excision repair (BER) Exp Mol Med. 2004;36:505–509. doi: 10.1038/emm.2004.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith and Seo, 2002.Smith ML, Seo YR. p53 regulation of DNA excision repair pathways. Mutagenesis. 2002;17:149–156. doi: 10.1093/mutage/17.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone et al., 1987.Stone DM, Hanson GR, Gibb JW. Differences in the central serotonergic effects of methylendioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in mice and rats. Neuropharmacology. 1987;26:1657–1661. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(87)90017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun et al., 2003.Sun L, Liu SY, Zhou XW, Wang XC, Liu R, Wang Q, Wang JZ. Inhibition of protein phosphatase 2A- and protein phosphatase 1-induced tau hyperphosphorylation and impairment of spatial memory retention in rats. Neuroscience. 2003;118:1175–1182. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00697-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szyndler et al., 2002.Szyndler J, Wierzba-Bobrowicz T, Maciejak P, Siemiatkowski M, Rok P, Lehner M, Czlonkowska AI, Bidzinski A, Wislowska A, Zienowicz M, Plaznik A. Pentylenetetrazol-kindling of seizures selectively decreases [3H]-citalopram binding in the CA-3 area of rat hippocampus. Neurosci Lett. 2002;335:49–53. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng et al., 2002.Tseng HC, Zhou Y, Shen Y, Tsai LH. A survey of Cdk5 activator p35 and p25 levels in Alzheimer's disease brains. FEBS Lett. 2002;523:58–62. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02934-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang et al., 2000.Wang J, Shou J, Chen X. Dickkopf-1, an inhibitor of the Wnt signaling pathway, is induced by p53. Oncogene. 2000;19:1843–1848. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang et al., 2007.Wang Y, White MG, Akay C, Chodroff RA, Robinson J, Lindl KA, Dichter MA, Qian Y, Mao Z, Kolson DL, Jordan-Sciutto KL. Activation of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 by calpains contributes to human immunodeficiency virus-induced neurotoxicity. J Neurochem. 2007;103:439–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesierska-Gadek et al., 2006.Wesierska-Gadek J, Strosznajder JB, Schmid G. Interplay between the p53 tumor suppressor protein family and Cdk5: novel therapeutic approaches for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases using selective Cdk inhibitors. Mol Neurobiol. 2006;34:27–50. doi: 10.1385/mn:34:1:27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willert and Nusse, 1998.Willert K, Nusse R. β-Catenin: a key mediator of Wnt signaling. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi et al., 1996.Yamaguchi H, Ishiguro K, Uchida T, Takashima A, Lemere CA, Imahori K. Preferential labeling of Alzheimer neurofibrillary tangles with antisera for tau protein kinase (TPK) I/glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta and cyclin-dependent kinase 5, a component of TPK II. Acta Neuropathol. 1996;92:232–241. doi: 10.1007/s004010050513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau et al., 1994.Yau JL, Kelly PA, Sharkey J, Seckl JR. Chronic 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine administration decreases glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptor, but increases 5-hydroxytryptamine1C receptor gene expression in the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1994;61:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh et al., 1999.Yeh SY, Dersch C, Rothman R, Cadet JL. Effects of antihistamines on 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-induced depletion of serotonin in rats. Synapse. 1999;33:207–217. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(19990901)33:3<207::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakzanis and Campbell, 2006.Zakzanis KK, Campbell Z. Memory impairment in now abstinent MDMA users and continued users: a longitudinal follow-up. Neurology. 2006;66:740–741. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000200957.97779.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakzanis and Young, 2001.Zakzanis KK, Young DA. Memory impairment in abstinent MDMA (“Ecstasy”) users: a longitudinal investigation. Neurology. 2001;56:966–969. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.7.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu et al., 2002.Zhu Y, Lin L, Kim S, Quaglino D, Lockshin RA, Zakeri Z. Cyclin dependent kinase 5 and its interacting proteins in cell death induced in vivo by cyclophosphamide in developing mouse embryos. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:421–430. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]