Abstract

Several different integrins participate in the complex interactions that promote repair of the peripheral nervous system. The role of the integrin α6β4 in peripheral nerve regeneration was investigated in mice by cre-mediated deletion of the Itgb4 (β4) gene in Schwann cells. After a crush lesion of the sciatic nerve, the recovery of motor, but not that of sensory, nerve function in β4−/− mice was delayed. Immunostaining of neurofilament-200 showed that there also is a significant reduction in the number of newly outgrowing nerve sprouts in β4−/− mice. Morphometric quantitative measurements revealed that fewer axons are myelinated in the nonlesioned β4−/− nerves. After a sciatic nerve crush lesion, β4−/− mice did not only have fewer myelinated axons compared with lesioned wild-type nerve, but their axons also showed a higher g-ratio and a thinner myelin sheath, pointing at reduced myelination. This study revealed that the β4 protein remains expressed in the early stages of peripheral regeneration, albeit at levels lower than those before the lesion was inflicted, and showed that laminin deposition is not altered in the absence of β4. These results together demonstrate that integrin α6β4 plays an essential role in axonal regeneration and subsequent myelination.

Keywords: integrin, knock-out mice, sciatic nerve, Schwann cell, myelin repair, peripheral nerve

Introduction

Integrins are a family of heterodimeric cell surface receptors that mediate the adhesion of cells to other cells or to components of the extracellular matrix (ECM), e.g., collagen, fibronectin, or laminin (van der Flier and Sonnenberg, 2001; Hynes, 2002). The adhesive interactions mediated by integrins provide cells with signals that determine their relative position to one another. Additionally, after binding to ligand, integrins transmit signals to the cell interior that affect cytoskeletal organization, protein phosphorylation, calcium oscillations, or gene expression (for review, see Giancotti and Ruoslahti, 1999). Conversely, the affinity of integrins for ligand may be modulated by the activity of other cellular receptors resulting in integrin-dependent adhesion (Ginsberg et al., 2005).

Eighteen α subunits and eight β subunits of integrins have been identified in mammals that combine to form 24 different integrin heterodimers (van der Flier and Sonnenberg, 2001). The β1 subunit can form heterodimers with 12 different α subunits and is connected with the actin cytoskeleton. In contrast, the β4 subunit only forms a heterodimer with α6 and is associated with the intermediate filament cytoskeleton. The α6β4 integrin is expressed in a variety of epithelia, e.g., in basal keratinocytes of the epidermis, in which it is an essential component of hemidesmosomes (Litjens et al., 2006). Furthermore, α6β4 is present in perineural fibroblasts and in Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system (Sonnenberg et al., 1990; Feltri et al., 1994; Niessen et al., 1994).

Integrins participate in the complex interactions that promote the repair of the peripheral nervous system (Previtali et al., 2001; Vogelezang et al., 2001). After damage of axons and the subsequent Wallerian degeneration, a process involving the removal of the disconnected axons and their myelin sheaths, proliferating Schwann cells attach to each other to form bands of Büngner, which serve as a guide for axonal regrowth. The myelinating Schwann cells wrap themselves around a single individual axon, forming a myelin sheath of variable thickness. In α7-deficient mice, motor axon regeneration was delayed after axotomy of the sciatic nerve (Werner et al., 2000), whereas in wild-type mice, axotomy of the sciatic nerve led to a strong increase in the levels of the α7β1 integrin in regenerating motor and sensory neurons (Ekström et al., 2003). After nerve injury, the α4β1 integrin was found to be expressed in dorsal root ganglion cell bodies and axonal growth cones (Vogelezang et al., 2001). Furthermore, α6β4 appeared to be downregulated in Schwann cells after injury and reexpressed during remyelination and the full assembly of the Schwann cell basal lamina (Feltri et al., 1994; Nagarajan et al., 2002). The total β1 levels did not change, but the α7 level had increased and was higher than that in the nonlesioned nerve (Nagarajan et al., 2002).

Despite the extensive research on all the integrins, it is still not known whether β4 has an effect on axonal regeneration and associated myelination in vivo. The purpose of this study was to investigate the impact of β4 deficiency on the process of axonal outgrowth and myelination induced by a lesion of the sciatic nerve in the adult wild-type and β4 conditional knock-out mice, using both functional studies and a quantitative histological analysis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Mice expressing the P0–cre transgene were crossed with the ROSA26–lacZ cre reporter (strain R26R) that contained a loxP-flanked stop sequence upstream of the lacZ gene (Soriano et al., 1999). β4flox mice were crossed with mice expressing cre recombinase under control of the Schwann cell-specific P0 promoter. To create mice with a Schwann cell-specific deletion of β4, β4flox/+ mice (Raymond et al., 2005) were crossed with P0–cre mice, and P0–cre;β4flox/+ offspring were intercrossed. Because the P0 promoter is also active in testicular cells, leading to cre expression and recombination of the floxed Itgb4 gene during gametogenesis, these crosses resulted in hemizygous P0–cre;β4flox/− mice (25%), P0–cre;β4+/− mice (25%), and P0–cre;β4flox/+ mice (25%), as well as P0–cre;β4+/+ mice (25%). The P0–cre;β4flox/+ and P0–cre;β4flox/− mice have been used for the experiment shown in Figure 1., B and C. The P0–cre;β4+/+ mice together with the P0–cre;β4flox/− mice were used in all other experiments and are referred to as wild-type mice and β4−/− mice, respectively.

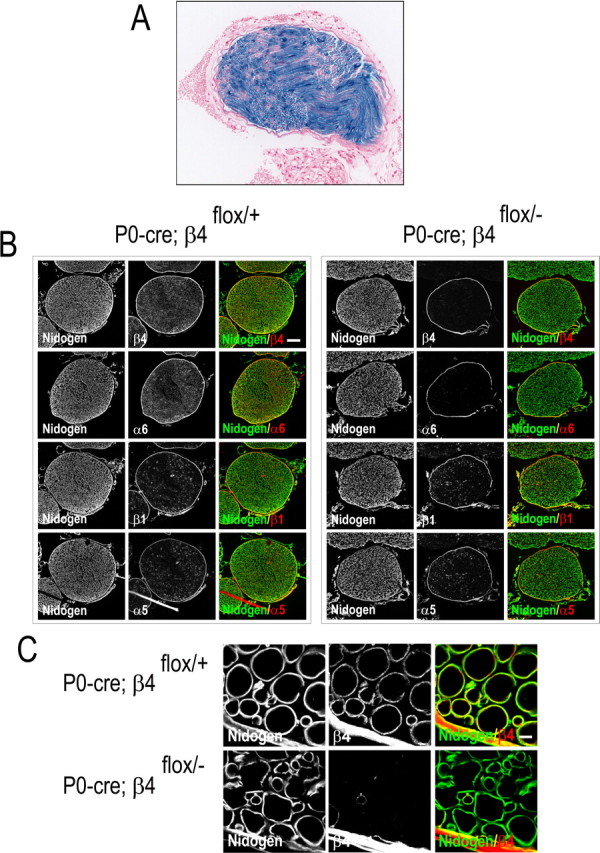

Figure 1.

A, lacZ expression is visualized by β-galactosidase activity (whole-mount X-gal staining; blue) in the branchial nerve of adult double-transgenic P0–cre;ROSA26R mice, followed by counterstaining of the sections with nuclear fast red (red). B, Immunofluorescence microscopy of the branchial nerve. Cryosections of the branchial nerves of P0–cre;β4flox/+ mice (left) and P0–cre;β4flox/− (β4−/−) mice (right) were processed for indirect immunofluorescence and visualized by confocal microscopy. Primary antibodies against proteins are indicated in the bottom corner of each image, and colors are coded according to their reactivity with FITC and Texas Red secondary antibodies. Note the clear presence of α6 and β4 on Schwann cells in the endoneurial sheath of peripheral nerve in P0–cre;β4flox/+ mice and their strong reduction in those of P0–cre;β4flox/− (β4−/−) mice. The two integrin subunits, α6 and β4, are clearly expressed in perineural fibroblasts and in the epineurium of P0–cre;β4flox/+ and P0–cre;β4flox/− (β4−/−) mice. C, Integrin β4 is present in a patchy pattern at the abaxonal Schwann cell surface in P0–cre;β4flox/+ mice (top panels in C) as shown in the endoneurial sheath at higher magnification. Scale bars: B, 80 μm; C, 5 μm.

Animals were housed in a virus-free facility on a 12 h light/dark cycle and were fed a standard rodent chow. All protocols for animal use and euthanasia were reviewed by the animal care committee of The Netherlands Cancer Institute and were in accordance to the Dutch Council for Animal Care and the National Institutes of Health guidelines. Genotyping was performed by PCR using genomic DNA isolated from tail tips as described previously (Raymond et al., 2005).

Crush lesion of the sciatic nerve

For the functional studies, male (29.9 ± 1.9 g) and female (28.2 ± 1.3 g) wild-type mice and male (32.2 ± 1.3 g) and female (29.7 ± 2.2 g) β4−/− mice were used. The sciatic nerve of the right hindpaw in wild-type (n = 17) and β4−/− (n = 17) mice was subjected to a crush lesion. A standardized sciatic nerve crush lesion method has been described for rats (De Koning et al., 1986) and was adapted for mice (Van der Zee et al., 2003). In short, mice were anesthetized using a 1:1:2 mix containing Hypnorm (0.315 mg/ml fentanyl citrate plus 10 mg/ml fluanisone; Janssen Pharmaceutica), Dormicum (5 mg/ml midazolam; Roche), and distilled water. A dose of 70 μl/10 g body weight was injected intraperitoneally. After incision of the skin between the knee and the thigh, the sciatic nerve was carefully exposed and subsequently crushed during 60 s using a hemostatic forceps with a waffle-shaped mouth structure. The nerve was crushed at the sciatic notch point immediately distal from where it emerges from under the gluteus maximus. The skin was sutured, and mice were kept in cages on a heating pad for 1 h to prevent loss of body temperature.

For the histological study with neurofilament-200 (NF-200) immunostaining, a nerve crush lesion was performed 4 months later on the left sciatic nerve of these same wild-type (n = 5) and β4−/− (n = 5) mice. The distal side of the crush lesion was marked with an epineural suture (0.7 metric 6-0 blau monofil; Ethicon), placed laterally through the epineurium, for recognition of the crush site at 4 d after lesion. For the light microscopy and the electron microscopy analyses of the myelinated nerve fibers, an additional group of wild-type (n = 3) and β4−/− (n = 3) mice was subjected to a crush lesion of the right sciatic nerve and perfused after 5 d.

Motor function recovery test

The recovery of motor function, after a sciatic nerve crush lesion, was monitored by analyzing the individual mouse free-walking pattern. The walking test method has been described originally for rats (de Medinaceli et al., 1982), was modified by De Koning and Gispen (1987) (see also Van Meeteren et al., 1997), and has been applied in mice (Van der Zee et al., 2003; Wansink et al., 2004). The progress of motor function recovery in the sciatic nerve was calculated using eight footprint parameters (distance in millimeters) and a correction factor according to the following formula: SFI = [(ETOF − NTOF)/NTOF + (NPL − EPL)/EPL + (ETS − NTS)/NTS + (EIT − NIT)/NIT] × 46. The abbreviations are as follows: SFI, sciatic functional index (percentage); NTOF, normal to opposite foot; ETOF, experimental to opposite foot; NPL, normal print length; EPL, experimental print length; NTS, normal toe spreading; ETS, experimental toe spreading; NIT, normal inner toe spreading; and EIT, experimental inner toe spreading. This formula provides an SFI value of approximately −100 to −90% directly after the crush lesion (postlesion day 4; ETS and EIT are both set at 2 mm) and an SFI between −10% and +10% for nonlesioned control mice and when full recovery of motor function is obtained (de Medinaceli, 1995).

In the test procedure, each mouse was allowed to get used to the experimental environment by letting the animal walk through an inclining (10°) alley (40 × 3.5 cm) that leads into a dark box. Then, a strip of photographic paper was placed on the bottom of the alley, and, after dipping the two animal's hindpaws in photographic paper developer fluid (Polymax II RC semimatt; Eastman Kodak), the animal was again placed at the beginning of the alley to let it walk into the dark box. Subsequently, after allowing the photographic strip to dry, mouse footprints were recorded. Motor function recovery was determined on postlesion day 4 and then every second day starting from postlesion day 8.

Sensory function recovery test

The return of sensory function after a sciatic crush lesion was determined using the foot-withdrawal reflex test (De Koning et al., 1986; Van der Zee et al., 1991, 2003; Wansink et al., 2004). Mice were immobilized by hand with the soles of their feet facing the examiner. A range of small electric currents (100, 300, and 500 μA) was applied to the sole of the foot by a small connector containing two stimulation electrodes. Mice immediately retracted their uninjured paw after sensing the electric stimulus. When the stimulus was applied to the sole of their lesioned paw, the withdrawal reflex did initially not occur. During the regeneration/reinnervation process, the reflex was restored. Absence of the withdrawal reflex during stimulation at 500 μA was interpreted as no recovery, whereas mice responding with the reflex withdrawal at 100 μA current (at 3 consecutive days) were considered to have recovered. The reflex withdrawal was measured daily from postlesion day 8 until full recovery.

Perfusion, dissection, and peripheral nerve sectioning

For histological analysis and NF-200 immunostaining, mice were perfused transcardially with 15 ml of 0.1 m PBS, followed by 30 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, at postlesion day 4. The sciatic nerves were dissected, postfixed overnight, and then stored in Millonig's buffer (PBS with 0.06% NaAzide). Cryoprotection before cryostat cutting of the nerve tissue was obtained through graded sucrose solutions (7.5, 15, and 30%), each step lasting at least 2 h. The sciatic nerves were cut (10-μm-thick transverse sections) at 4 mm proximal to and at 1, 3, and 5 mm distal to the crush site (marked by the epineural suture at the distal edge). Sections were mounted on Superfrost Plus microscope slides (Menzel Gläser) and left to dry. Each slide contained a set of 10 nerve sections (10 μm thick, 30 μm apart) and was stored at −80°C until staining. Sciatic nerve longitudinal sections (10 μm thick) were cut as well.

Neurofilament-200 immunostaining

A repellant border around the sections was created with a DakoCytomation pen (to be able to apply a volume of 500 μl). The slides were placed in a humid incubation box, moistened with 500 μl of blocking buffer (PBS solution plus 0.15% glycine and 1% cold water fish skin gelatin) and incubated for 30 min at room temperature (RT). The blocking buffer was carefully removed by suction. The nerve sections were then incubated with the primary antibody, rabbit anti-NF-200 (NF-200, 1:1000; Sigma), and diluted in blocking buffer overnight at RT. The next day, the slides were rinsed three times for 5 min in PBS and 0.05% Tween 20 and incubated for 1 h at RT with a donkey anti-rabbit biotinylated secondary antibody 1:250 (Jackson ImmunoResearch) diluted in blocking buffer. The slides were rinsed again three times during 5 min with PBS and 0.05% Tween 20. The avidin–biotin complex solution (5 ml, 1:125, ABC Vectastain Elite; Sigma) was made 30 min before use, after which 400 μl was added to the slides and left for 30 min at RT. Slides were rinsed three times for 5 min in PBS. Finally, 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) substrate solution (4 mg of AEC dissolved in 1 ml of N,N-dimethylformamide and mixed with 14 ml of 0.1 m acetate buffer, pH 5.0, with added 15 μl of 30% hydrogen peroxide) was applied to the nerve sections on the slides for 8 min at RT. The coloring reaction was stopped by rinsing the sections with distilled water. Then, the tissue was entrapped in Kaiser's gelatin–glycerol, and the slides were coverslipped. Images were obtained using a Dialux 20 microscope (Leitz) connected to a digital camera attached to the computer image analysis system.

Myelin staining

For morphometric analysis of the myelinated axons in the peripheral sciatic nerve, mice were perfused transcardially with 15 ml of 0.1 m PBS, followed by 30 ml of 0.5% paraformaldehyde and 1.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, at postlesion day 5. The sciatic nerves on both sides were dissected and postfixed in the same fixation buffer for 1 h. Tissues were washed two times for 1 h and overnight in 0.1 m phosphate buffer. Postfixation was then continued for 1 h in 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 m phosphate buffer. After two washes for 1 h in 0.1 m phosphate buffer, tissues were dehydrated in an ascending series of aqueous ethanol and subsequently transferred via a mixture of propylene oxide and Epon to pure Epon 812 as embedding medium.

Light microscopy.

Semithin 1 μm sections were cut and mounted on glass slides and subsequently counterstained with toluidine blue. Digitized light microscopy (Leitz Dialux 20 microscope) images were used for quantitative analysis to determine the nerve diameter, the number of myelinated axons per 12,500 μm2, and the myelin area of each of the 60 axons measured per nerve section at 5 d after crush lesion.

Electron microscopy.

From the Epon 812-embedded peripheral sciatic nerves, ultrathin gray sections (60–80 nm) were cut, contrasted with aqueous 3% uranyl acetate, rinsed and counterstained with lead citrate, air dried, and examined in a Jeol 1010 electron microscope.

Quantitative analysis

Neurofilament-200-positive axons.

The number of NF-200-positive axons was determined in the mouse sciatic nerve 4 d after crush lesion. Counting was performed in the proximal (nonlesioned) part of the nerve (4 mm proximal to the crush site) and 1, 3, and 5 mm distal to the crush site, with three 10 μm nerve sections counted at each distance per mouse. NF-200 antibody/AEC immunostaining revealed nonlesioned axons under the microscope as relatively large- and medium-sized red dots. Newly outgrowing axonal sprouts in the distal sections appeared as small red dots. Counting was performed using a light microscope (Leitz Wetzlar dialux 20) with the 40× objective and an ocular grid containing10 × 10 squares. One square was 25 × 25 μm (625 μm2). Counting of the NF-200-positive axons in the distal nerve sections was performed in a total of 20 squares (mostly two rows of 10 squares = 12,500 μm2) per section, representing ∼10% of the total nerve bundle area. In the proximal nerve sections, 10 squares were counted, and the number was multiplied by two to obtain the average number of NF-200-positive axons per 12,500 μm2.

Myelinated axons.

An additional group of wild-type (n = 3) and β4−/− (n = 3) mice 5 d after a crush lesion was used for detailed quantitative and morphometric analysis of the myelinated axons in the nonlesioned (left paw) and in the regenerating (right paw) sciatic nerves. The PC Image digital analysis system (Bos Inc.) with a video camera attached to the light microscope was used to obtain digitized images of osmium tetroxide–toluidine blue stained transverse 1-μm-thick nerve sections to visualize the numerous individual axons and their surrounding myelin sheath. Nerve sections were taken at 3 mm distal to the crush site (or equivalent place in the nonlesioned nerves), which had been marked with a small epineural suture. First, cross-section area of the total nerve bundle was measured and digitized into six images. All myelinated axons were then counted in three images, representing ∼50% of the total nerve section per nerve per mouse and expressed as the number of myelinated axons per 12,500 μm2. Subsequently, from a total of 180 axons (in nonlesioned nerves) or 120 axons (in lesioned nerves), the individual total fiber area, the axon area, and (after subtraction) the myelin area were measured. The average axon area and myelin area per axon were calculated in each group. The g-ratio (axon area/total fiber area) was calculated for each individual axon, averaged per mouse and per group, as well as the g-ratio frequency distribution.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

To demonstrate the presence of β4 integrin, other integrin subunits, basement membrane molecules, and extracellular matrix molecules in Schwann cells or the endoneurial sheath, we applied immunofluorescence on cryosections of nonlesioned and lesioned sciatic nerves. Sections were taken at 3.0 mm distal to the crush site in lesioned nerves or the equivalent site in nonlesioned nerves and collected and embedded in cryoprotectant (Tissue-Tek O.C.T.; Sakura Finetek). The 5-μm-thick cryosections were fixed for 5 min in ice-cold acetone, blocked with 2% BSA in PBS, and incubated for 45 min with the following primary antibodies: rabbit polyclonal antibodies against β4 (described previously by Wilhelmsen et al., 2007), nidogen (kind gift from Dr. Takako Sasaki, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR), collagen IV (kind gift from Dr. E. Engvall, The Burnham Institute, La Jolla, CA), or laminin-α2 and laminin-α5 (kind gifts from Dr. Lydia Sorokin, Muenster University, Muenster, Germany), or the rat monoclonal antibodies MB1.2 and BMA5 against β1 and α5, respectively (kind gifts from Dr. Bosco Chan, University of Western Ontario, London, Canada), GoH3 against α6, 346–11A against β4 (BD Biosciences). The incubation with the primary antibody was followed by an incubation with FITC- and Texas Red-labeled secondary antibodies diluted 1:100 for 45 min.

Western blotting

For Western blotting, sciatic nerve tissue (without the epineurial layer) was obtained with the P.A.L.M. laser microdissection microscope (Zeiss) by means of a focused laser beam to excise portions of a tissue sample. The excised portions are then laser catapulted from the nerve section sample and collected. From 10–20 cryosections, each 10 μm thick, of the sciatic nerve 2.0–3.0 mm distal to the crush site, the excised portions were collected in Laemli's sample buffer with 0.5% β-mercapto-ethanol and incubated at 95°C for 5 min. Samples were loaded on a 4–12% Bis–Tris gel (Invitrogen) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, which were subsequently decorated with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against β4 (described previously by Wilhelmsen et al., 2007) and the mouse monoclonal antibody against actin (Bio-Connect). Proteins were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence kit from GE Healthcare.

Statistics

Data obtained from the wild-type and β4−/− mice are presented as means ± SEM. All counting data were obtained blind as to genotype and subsequently analyzed using the appropriate statistical tools (ANOVA with repeated measures, independent sample t test; SPSS 12.0 statistics software). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Generation of mice with a conditional inactivation of the Itgb4 gene in Schwann cells/peripheral nerves

The generation of transgenic mice carrying the cre transgene under the control of the P0 gene promoter has been described previously (Giovannini et al., 2000). To assess the activity of the P0–cre transgene and to determine its tissue specificity, P0–cre transgenic mice were crossed with mice carrying the ROSA26R–lacZ reporter (Soriano et al., 1999). These mice carry a lacZ gene, whose expression requires the excision of loxP-flanked stop sequences. Analysis of tissues from adult double-transgenic P0–cre;ROSA26R mice for the expression of lacZ indicated that the appropriate recombination had occurred in Schwann cells, which are present in the endoneurial sheath of peripheral nerves, as shown in the branchial nerve (Fig. 1A). No lacZ activity was detected in cells other than Schwann cells in several tissues, e.g., skin and kidney from these double-transgenic mice.

We then crossed the P0–cre transgenic mice with mice carrying a conditional (loxP-flanked) Itgb4 allele (Raymond et al., 2005). The P0–cre;β4flox/+ offspring were intercrossed, producing P0–cre;β4+/+ mice (referred to as wild-type mice) and P0–cre;β4flox/− mice (referred to as β4−/− mice). To assess the efficiency of the inactivation of the Itgb4 gene, we performed immunohistochemistry on cryosections of peripheral nerves with antibodies against integrin β4. Whereas in P0–cre;β4flox/+ mice (obtained from the same intercross that produced the P0–cre;β4flox/− mice) β4 was present in a patchy pattern at the abaxonal surface of the myelinating Schwann cells, facing the nidogen-positive basal lamina, only traces of β4 could be detected in the P0–cre;β4flox/− (β4−/−) mice (Fig. 1B,C at higher magnification). The expression of the α6 subunit was reduced to the same extent, indicating that the loss of α6β4 was not compensated for by the formation of extra α6β1. The lack of α6β4 was restricted to the Schwann cells in the endoneurial sheath of P0–cre;β4flox/− (β4−/−) mice, whereas strong staining of the α6 and β4 subunits was visible in perineural fibroblasts and the epineurium in both the P0–cre;β4flox/+ and P0–cre;β4flox/− mice (β4−/−). Furthermore, there were no differences in the levels of the α5 or β1 subunits in the Schwann cells of both groups (Fig. 1B). In conclusion, cre-mediated recombination in Schwann cells leads to a strong and specific reduction of α6β4, without affecting the expression of other integrins.

Delayed motor function recovery after a sciatic nerve crush in β4−/− mice

To investigate the role of β4 in peripheral nerve regeneration, a crush lesion was applied to the sciatic nerve of the right hindpaw in wild-type (n = 17) and β4−/− (n = 17) mice. The gradual recovery of motor function after a unilateral sciatic crush lesion was assessed by monitoring the animal's gait in a walking alley at regular time points after the lesion was applied. By measuring the footprint parameters of the regenerating hindpaw and the contralateral (nonlesioned) side, the sciatic functional index can be determined. On postlesion day 4, an SFI of approximately −85% established that the crush lesion in both animal groups was complete (data not shown). In the days after the nerve crush lesion, the motor function of the regenerating paw gradually returned in wild-type mice (Fig. 2). The first signs of motor function recovery became apparent on day 10 (index value, −58 ± 6%). Subsequently, motor function continued to improve over time, reaching almost full recovery (when SFI values range between −10% and +10%) on postlesion day 14 and thereafter still further increased to a value of 0.8 ± 3.6% on day 24 after lesion.

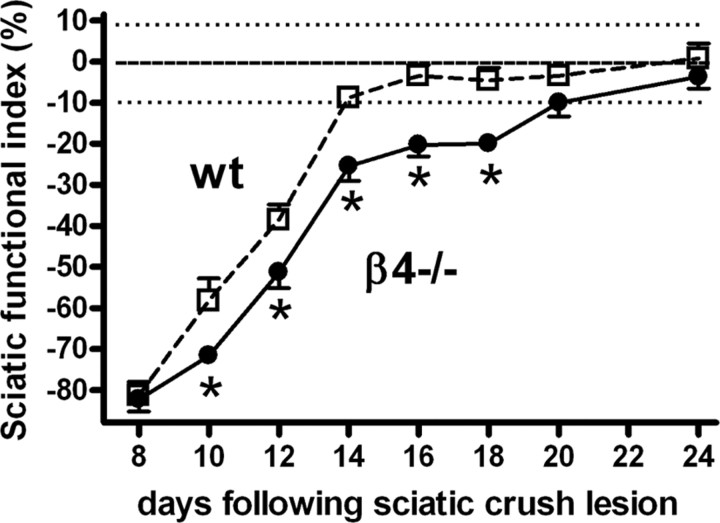

Figure 2.

Motor function recovery after unilateral sciatic nerve crush lesion. A gradual recovery of motor function was measured using the sciatic functional index based on the comparison of footprint parameters of the regenerating hindpaw with the contralateral paw. Wild-type mice (wt; white squares) reached full recovery on postlesion day 14, whereas β4−/− mice (β4−/−; black circles) did not reach full recovery until postlesion day 20. Motor function recovery was significantly delayed in β4−/− mice (F(1,32) = 12.316; p < 0.001).

In β4−/− mice, the motor function also gradually returned as shown by their gait, but recovery was delayed compared with that in wild-type mice. The first signs of recovery became apparent on postlesion days 10 and 12, with index values of −72 ± 2 and −51 ± 4%, respectively. In β4−/− mice, full recovery was not reached until postlesion day 20, with an index value of −10 ± 3%, and − 4 ± 3% at day 24 after lesion. Consequently, the recovery time of motor function in β4−/− mice was significantly longer than in wild-type animals (F(1,32) = 12.316; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Recovery of sensory function after a sciatic nerve crush is not affected in β4−/− mice

The gradual recovery of sensory function was assessed daily by applying a small current stimulus and scoring the subsequent occurrence or absence of the foot-withdrawal reflex. Figure 3 shows the results of the recovery of sensory function in the wild-type and β4−/− mice. In wild-type mice, the first signs of recovery in their lesioned hindpaw occurred as early as on postlesion day 12, with 90% of the group having recovered on day 23 (Fig. 3). The recovery of the sensory function in β4−/− mice was very similar to that of the wild-type mice. The earliest recovery in this group occurred on postlesion day 12 (one mouse), whereas half of the group responded at day 17, and 90% reached full recovery on postlesion day 24 (Fig. 3). In conclusion, the average sensory function recovery time was similar in the two groups (wild-type mice, 17.3 ± 0.9 d; β4−/− mice, 17.8 ± 0.9 d).

Figure 3.

Sensory function recovery after unilateral sciatic nerve crush lesion. The gradual recovery of sensory function shown here was determined by daily applying a small current stimulus (0.1 mA) and scoring the foot-withdrawal reflex. Wild-type mice (wt; white squares) and β4−/− mice (β4−/−; black circles) showed a similar return of sensory function, with 90% of the animals having reached full recovery at postlesion day 23–24.

Diminished number of neurofilament-200-positive axons in β4−/− regenerating nerves

NF-200 immunostaining of the proximal, nonlesioned, part of the sciatic nerves from wild-type and β4−/− mice (n = 5 each) revealed a similar staining pattern, with NF-200-positive axons appearing as large- and medium-sized red dots (Fig. 4A–D). Myelination rings were visible as white transparent areas surrounding the axons, shown here in the wild-type and β4−/− sciatic nerve sections (Fig. 4A–D). Counting NF-200-positive axons over a surface of 12,500 μm2 area of the proximal, nonlesioned, part of the sciatic nerve demonstrated a similar number of 320 ± 45 axons in wild-type and 330 ± 35 axons in β4−/− animals.

Figure 4.

Immunostaining of NF-200 in nonlesioned and lesioned sciatic nerves. Photomicrographs of transverse sections of nonlesioned sciatic nerves of wild-type (A, C) and β4−/− (B, D) mice show similar immunostaining for NF-200. The individual axons are seen as red dots of variable size. Insets in A and B show a cross-section of the entire sciatic nerve. On day 4 after a sciatic crush lesion was applied, the newly outgrowing axons are visible as small red dots in wild-type (E) and β4−/− (F) mice, here shown in transverse nerve sections located at a distance of 1 mm distal to the crush site. Although the total number of NF-200-positive axons in the proximal nonlesioned part of the nerve was similar in wild-type (wt) and β4−/− mice, quantitative analysis (G) revealed that the number of newly formed nerve sprouts during regeneration was significantly smaller in β4−/− nerves (black bars) than in wild-type nerves (wt; white bars). Longitudinal sections of nonlesioned wild-type (H) and β4−/− (I) sciatic nerves showed no differences; however, there was a clear delay in outgrowth of regenerating sprouts (arrows pointing at red NF-200-positive dots) in β4−/− mice (J) compared with wild-types (K) at 5 d after crush lesion (with the crush site toward the left of the photograph). *p < 0.009. Scale bars: (in A) A, B, 115 μm; insets in A, B, 57 μm; (in F) C–F, 100 μm; (in H) H, I, 62.5 μm; (in J) J, K, 50 μm.

On day 4 after the sciatic nerve crush lesion and at 1, 3, and 5 mm distal to the crush site, there was NF-200 staining of newly formed axonal sprouts, seen as small dark red dots in wild-type and β4−/− mice. Examples of transverse nerve sections at 1 mm distal to the crush site of wild-type and β4−/− mice are shown in Figure 4, E and F. For a quantitative analysis, the number of NF-200-positive axonal sprouts at 1, 3, and 5 mm distal to the crush site were counted in three nerve sections per distance from each mouse. The average number of axons per 12,500 μm2 area (20 squares), at all distances, are presented in Figure 4G in mice with either genotype.

When compared with that in lesioned wild-type sciatic nerves (n = 5), the number of newly outgrowing NF-200-positive axons in β4−/− nerves (n = 5) was significantly lower at all three distances (1, 3, and 5 mm) distal to the crush site 4 d after lesion (ANOVA with repeated measures, F(1,8) = 11.882; p < 0.009) (Fig. 4G). At the farthest distance (5 mm), we counted ∼30% fewer axons in β4−/− regenerating nerves than in wild-type nerves (p < 0.027) (Fig. 4G).

The increase in the number of NF-200-positive axon sprouts at 1–3 mm from the crush site in the wild-type and the β4−/− mice (from 184 ± 15 to 220 ± 6 in wild-type mice, p < 0.049; and from 151 ± 15 to 197 ± 12 in β4−/− mice, p < 0.047) (Fig. 4G) can be attributed to branching, by which numerous small lateral outgrowths are formed (Fig. 4J,K), later followed by pruning. Sprouting was not yet complete at 5 mm from the crush site because there were fewer NF-200-positive axons than at 3 mm, with a count of 164 ± 8 in wild-type animals and 118 ± 15 in β4−/− mice (Fig. 4G). Longitudinal sections of nonlesioned wild-type (Fig. 4H) and β4−/− (Fig. 4I) sciatic nerves showed no differences between the two groups; however, a clear delay in the outgrowth of regenerating sprouts was observed in β4−/− mice (Fig. 4J) compared with wild types (Fig. 4K) at 5 d after crush lesion (arrows indicate sprouts; crush site located outside the picture toward the left).

Fewer myelinated axons in nonlesioned β4−/− nerves

Because β4 is normally expressed in (myelinating) Schwann cells, quantitative and morphometric analyses of the myelinated axons in the sciatic nerve were performed to determine whether in the (conditional) β4−/− mice the process of myelination is affected by the absence of β4. Using osmium tetroxide–toluidine blue staining of 1 μm semithin nerve cross-sections, the total tibial nerve bundle area was examined, and the total number of myelinated axons present in approximately half of the nerve bundle was counted (Fig. 5A,B,E). The overall appearance of the nonlesioned sciatic nerve cross-section was similar in wild-type and β4−/− mice (Figs. 4A,B, insets, 5A,B), with a total tibial nerve bundle area of 133,497 ± 2531 and 129,553 ± 3632 μm2, respectively.

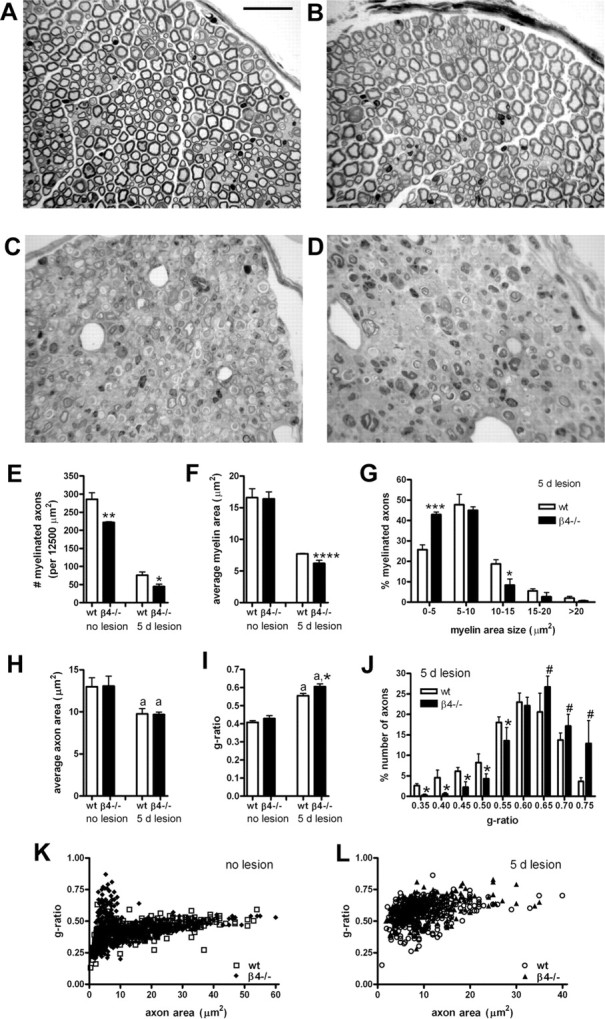

Figure 5.

Morphometry of myelinated axons in nonlesioned and lesioned sciatic nerves of wild-type and β4−/− mice. Light microscopic analysis of osmium tetroxide–toluidine blue-stained sciatic nerve sections was performed. A, B, E, Although both wild-type (A) and β4−/− (B) mice had numerous myelinated axons in their nonlesioned sciatic nerve, counting (E) revealed that the number of myelinated axons was significantly lower in the β4−/− mice. C, D, At 5 d after a crush lesion, sciatic nerve cross-sections at 3 mm distal to the crush site show morphological changes related to Wallerian degeneration and to the regeneration process in wild-type (C) and β4−/− (D) mice. E, The lesion-induced reduction in the number of myelinated axons was much stronger in β4−/− mice than in wild-type animals. F, The average myelin area per axon in nonlesioned nerves is similar in both groups. However, at 5 d after lesion, the reduction of the average myelin area per axon is significantly stronger in the regenerating β4−/− nerves (F). G, Frequency distribution of the size of the myelin area revealed fewer large myelinated areas and more thinly myelinated axons in the β4−/− nerves. H, Apart from the lesion-induced reduction, the average axon area in the two groups was not different, neither before nor after lesion. I, In nonlesioned nerves, the g-ratio (axon area/total fiber area) calculated was similar in wild-type and β4−/− mice, and a lesion-induced increase in g-ratio was apparent. The significantly higher g-ratio measured in β4−/− myelinated axons 5 d after lesion (attributable to a smaller total fiber area) (I), and the clear shift toward a higher g-ratio value in the frequency distribution graph (J), confirmed that, compared with wild types, the regenerating β4−/− nerves contain fewer thickly and more thinly myelinated axons. Scatter plots of g-ratio versus axon area for myelinated axons are from wild-type (wt) and β4−/− mice, before lesion (K; wild-type, 540 axons; β4−/−, 540 axons) and after lesion (L; wild-type, 356 axons; β4−/−, 329 axons). Scale bar: A–D, 33 μm. a, Compared with no lesion; #p < 0.06; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.025; ***p < 0.01; ****p < 0.005.

Although the total number of axons was not different in the nonlesioned nerves of wild-type and β4−/− mice, detailed counting revealed that the number of myelinated axons was significantly (22%) lower, as counted per 12,500 μm2, in the nonlesioned β4−/− nerves (p < 0.025) (Fig. 5E). The average myelin area of individual myelinated axons in these nonlesioned nerves, however, was not different in the two genotypic groups (Fig. 5F). Apparently, myelination is partly reduced during early development.

Fewer myelinated axons, a higher g-ratio, and a decreased myelin area per axon in β4−/− regenerating nerves

On day 5 after a sciatic crush lesion was applied, both wild-type and β4−/− nerves contained a much smaller number of myelinated axons, and they were mostly only thinly myelinated because of the lesion effect with Wallerian degeneration and regeneration (Fig. 5E). Strikingly, at 5 d after lesion, β4−/− nerves contained a significantly (40%) lower number of myelinated axons than the wild types (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5E). Thus, at 4 or 5 d after lesion, not only are fewer axons present (Fig. 4) but also fewer of those axons are (yet being) myelinated.

The average myelin area of the myelin sheath of the axons that are present on day 5 after lesion in β4−/− mice was also significantly (19%) smaller than that of wild-type axons (p < 0.005) (Fig. 5F). A frequency distribution graph of the myelin area depicted a clear shift to the left for β4−/− axons, as demonstrated by the fact that significantly fewer axons (p < 0.05) contained 10–15 μm2 myelin and significantly more axons (p < 0.01), 0–5 μm2 (Fig. 5G).

At 5 d after nerve damage, there was a lesion-induced reduction of the average axon area, but there were no differences between the two groups (Fig. 5H). In nonlesioned nerves, the g-ratio (axon area/total fiber area) calculated was similar for wild-type and β4−/− mice; however, at 5 d after the lesion, an increase in g-ratio was apparent (Fig. 5I). The significantly (p < 0.05) higher g-ratio measured in β4−/− myelinated axons 5 d after lesion (because of a smaller total fiber area) (Fig. 5I) and the clear shift toward a higher g-ratio value in the frequency distribution graph (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5J) confirmed that, compared with wild types, the regenerating β4−/− nerves contain fewer thickly and more thinly myelinated axons. A shift to higher g-ratio value for regenerating β4−/− nerves was also seen when the scatter plot of the g-ratio versus axon area for myelinated axons from β4−/− mice 5 d after lesion was superimposed on the one from wild-type mice (Fig. 5L). In contrast, superimposition of the scatter plot distributions for β4−/− mice and wild-type mice before the lesion showed similar patterns (Fig. 5K).

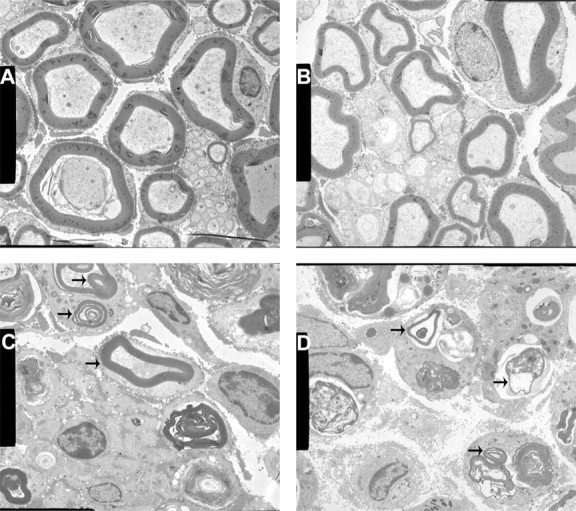

Electron micrographs of nonlesioned wild-type (Fig. 6A) and β4−/− (Fig. 6B) sciatic nerves clearly revealed that both genotypic groups contained axons with large-sized (thick), medium-sized, and small-sized (thin) myelin sheaths. As expected on day 5 after the sciatic crush lesion was applied, in both groups only few myelinated axons were visible among Wallerian degeneration debris (Fig. 6C,D). The myelin sheath surrounding these newly outgrowing axonal sprouts was quite thin in wild-type nerves (Fig. 6C,arrows), but, in the β4−/− nerves, axons contained an even thinner myelin sheath (Fig. 6D,arrows).

Figure 6.

Electron micrographs of nonlesioned and lesioned wild-type and β4−/− sciatic nerves. A, B, Both wild-type (A) and β4−/− (B) nerves had small-, medium-, and large-sized myelinated axons. Nonmyelinated axons, also surrounded by a Schwann cell, are located in the center of the micrograph. C, Five days after a crush lesion was applied, the wild-type nerve already demonstrated some myelinated axons (arrows) among Wallerian degeneration debris. D, Fewer and more thinly myelinated axons (arrows) were seen in the β4−/− nerve. Magnification: A–D, 4000×.

In conclusion, the reduction in the number of myelinated axons and the diminished extent of myelination in regenerating β4−/− nerves points to an important role of β4 in the regenerative myelination process after an induced lesion.

The β4 protein remains present after nerve injury

Immunofluorescent staining of nonlesioned wild-type sciatic nerve revealed the presence of β4 in the endoneurium (Fig. 7A, top row). In the sciatic nerve of β4−/− mice, most Schwann cells did not stain for β4, confirming the conditional knock-out approach (Figs. 7A, middle row, 8, middle panel). The faint immunostaining that can still be seen in a few Schwann cells may reflect differences in the time that the β4 protein remains stable. Importantly, immunostaining for β4 could still be detected in wild-type sciatic nerve 4 d after it was lesioned. This staining for β4, however, was much weaker than that in nonlesioned wild-type sciatic nerve. Furthermore, it was seen in all wild-type Schwann cells (Fig. 7A, bottom row) in contrast to what was observed in the sciatic nerve of β4−/− mice (Fig. 7A, middle row).

Figure 7.

Immunofluorescence and Western blotting show the presence of β4 protein in nonlesioned and in 4 d lesioned sciatic nerve. The presence of nidogen, β4, and their colocalization is shown in the endoneurium of nonlesioned wild-type (wt) nerve (A, top row). In β4−/− nerve, most Schwann cells did not stain for β4, only few cells being found to weakly express this integrin subunit. The weak expression in these cells may be caused by differences in the time that the β4 protein remains stable in the different Schwann cells (A, middle row). At 4 d after sciatic nerve crush lesion, the wild-type (wt) nerve stained weakly, but visible, for β4 in all Schwann cells (A, bottom row). Scale bar, 80 μm. In B, Western blotting demonstrates that expression of the β4 protein was strongly reduced in the lesioned wild-type (wt) nerve compared with β4 expression in the nonlesioned wild-type (wt) nerve.

Figure 8.

The distribution and expression of ECM components in the endoneurial basement membrane is normal. Cryosections of lesioned and nonlesioned nerves of wild-type and β4−/− mice were processed for immunofluorescence and visualized by confocal microscopy. Primary antibodies against proteins [Nidogen; β4, integrin subunit; Co-IV, collagen IV; Ln-α2, laminin-α2; Ln-α5, laminin-α5) are indicated in the left bottom corner of each image, and colors are coded according to their reactivity with FITC and Texas Red secondary antibodies. Note that the distribution pattern of the ECM components in nonlesioned and lesioned nerves of β4−/− mice is similar to that of nonlesioned wild-type mice. Interestingly, laminin-α5 appears to be prominent at the nodes of Ranvier. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Western blotting confirmed the reduced expression of β4 in wild-type sciatic nerve dissected at 4 d after it was lesioned and showed the near absence of β4 in the sciatic nerve of β4−/− mice nerves (Fig. 7B).

Normal laminin deposition in the absence of α6β4

Previous studies have demonstrated the importance of laminin-211 in axon myelination and regeneration in the peripheral nerve (Chen and Strickland, 2003). Considering the potential role that integrins have in basement membrane assembly through anchorage of laminin to the cell surface, we investigated whether the much lower level of α6β4 during nerve regeneration or the total absence of this integrin has an effect on the deposition of the major endoneurial ligand of α6β4, laminin-211, and laminin-511. Immunohistochemical analysis of both nonlesioned and lesioned wild-type and β4−/− sciatic nerve showed no obvious difference in the distribution and the amount of the laminin α2 and α5 chains, which form part of the laminin-211 and laminin-511 isoforms, respectively (Fig. 8). The distribution patterns of other ECM components, collagen IV and nidogen, were similar in nonlesioned and lesioned wild-type and β4−/− sciatic nerves as well (Fig. 8). Together, the data show that there is no effect of β4 on the deposition of laminin-211 or other basement membrane components. Therefore, it is likely that the delayed peripheral nerve regeneration of lesioned β4−/− sciatic nerve is not attributable to an altered pattern of ECM deposition but the result of a reduced adhesion capacity of Schwann cells to laminin isoforms.

Discussion

In this study, we show that, in the endoneurium of nonlesioned wild-type peripheral nerve, β4 is present at the abaxonal Schwann cell surface in a “patchy” pattern. Previous studies have demonstrated that, in wild-type mice shortly after a sciatic nerve crush lesion, the expression of β4 is reduced, but it is still present in small amounts. We confirm these findings and show using a conditional knock-out approach in which the Itgb4 gene is specifically inactivated in Schwann cells, that the integrin α6β4 is not strictly required for the onset of myelination, but that its loss leads to a diminished outgrowth and reduced myelination of axons, as indicated by a higher g-ratio, during peripheral nerve regeneration. Conditional knock-out of β4 resulted in a slower recovery of motor, but not of sensory, nerve function. Also, fewer axons in β4−/− mice are myelinated during development. Finally, laminin deposition is not altered in the absence of β4.

Reduced myelination

After a sciatic nerve crush lesion, the recovery of motor function, but not that of sensory function, was significantly delayed in adult β4−/− mice. In addition, the regenerating β4−/− sciatic nerves contained fewer NF-200-positive axons 4 d after lesion as shown over a length of nerve of 5 mm distal to the crush site. Although myelination of peripheral nerve axons still occurred in β4−/− mice, quantitative analysis revealed that fewer axons were myelinated in the nonlesioned β4−/− nerves. Five days after a sciatic nerve crush lesion and subsequent regeneration, morphometric measurements demonstrated that not only fewer β4−/− axons were myelinated but that the myelin sheath of β4−/− axons was thinner. Thus, myelination is reduced during regeneration of injured peripheral β4−/− nerves. Because the nerve function has fully recovered after 28 d, it is anticipated that, in time, myelin thickness will return to preinjury levels. However, additional work is required to substantiate this supposition.

Western blotting and immunostaining of cryosections from nonlesioned nerves and nerves 4 d after lesion demonstrated that α6β4 remains expressed in the early stage of peripheral regeneration, although at much lower levels than in nonlesioned nerves. Our measurements confirmed the previous findings by Nagarajan et al. (2002), who reported a 70% decrease on day 4 after lesion, followed by reexpression of β4 mRNA on day 7–14. Because they reported a return to normal (preinjury) β4 mRNA levels at 28 d after lesion, i.e., at full functional recovery, it is likely that the levels of β4 protein will also be back to normal. It is perhaps unexpected that, in β4−/− mice, an effect of the loss of α6β4 on nerve regeneration is seen at day 4 after lesion, i.e., at the time that the expression of this receptor is strongly reduced in wild-type animals. One explanation could be that the amount of α6β4 in the region where new axons actually grow out has locally already increased to normal levels. Because this increase in that case is restricted to a small part of the nerve containing outgrowing sprouts, it may have escaped detection by Western blotting and microarray assays. Furthermore, because α6β4 is a high-affinity receptor for different laminin isoforms, low levels of this receptor may already be sufficient to secure the adhesion of the Schwann cells to their basement membrane.

β4-mediated cell adhesion and axonal outgrowth

During the early growth phase of axonal regeneration, axons grow by elongation, i.e., the axons advance fast and in a straight line, and grow with branching, by which numerous small lateral outgrowths are formed. This branching or sprouting phenomenon has been reported previously (Murray, 1982; Jenq and Coggeshall, 1984; de Medinaceli, 1995; Van der Zee et al., 2003). Our quantitative analysis indeed revealed more axon sprouts at 3 mm than at 1 mm distal from the crush site but in both wild-type and β4−/− mice. Apparently, β4 does not affect branching. However, the total number of newly outgrowing NF-200-positive axon sprouts was significantly smaller in β4−/− mice at 5 mm distal to the crush on the day 4 after lesion, indicating that axonal outgrowth is reduced. Elongation and thus growth speed appear to be strongly affected by β4, although branching is not.

The reduced axonal outgrowth causes axons to reach their targets later, and, in combination with reduced myelination, the nerves to function less efficiently. Indeed, we found a significant delay in the recovery of motor function in the β4−/− mice. However, the recovery of sensory function was not significantly delayed in these mice. One explanation might be that the normally thickly myelinated motor axons are most affected by their diminished myelination in β4−/− nerves (see the shift to the left, i.e., thinly myelinated fibers), whereas in wild-type nerves, a part of the sensory axons contain a thinner myelin sheath and are therefore less affected. Another possibility is that the direction of outgrowing motor axons in wild-type mice is determined by the presence of α6β4-expressing Schwann cells and that the β4−/− Schwann cells cannot efficiently promote the outgrowth of motor axons. This difference in recovery between wild-type and β4−/− nerves is not without precedent. Previous studies have shown that myelinating Schwann cells of ventral roots and muscle nerves (both containing motor axons), but not those of dorsal roots or cutaneous nerves (both have sensory axons), express the carbohydrate epitope L2/HNK-1, which plays an important role in the reinnervation of muscles by regenerating motor neurons (Madison, 1996; Mears et al., 2003). The regeneration of sensory axons appears not to depend on the presence of the HNK-1 epitope (Mears et al., 2003). Interestingly, Madison et al. (1996) could also demonstrate regeneration of sensory afferents of only those axons that enter the muscle pathway, projecting to muscle stretch receptors. They probably respond to the same guidance factor (L2/HNK-1 expressed by Schwann cells). Intriguingly, it has been shown that, on some cells, the α6β4 integrin carries a unique carbohydrate epitope, which is recognized by the 280 monoclonal antibody (Phillips et al., 1991), and it is tempting to speculate that, when expressed on Schwann cells, this carbohydrate epitope fulfills a function, similar to that of the L2/HNK-1 epitope, in directing motor, but not so much sensory, axons.

Integrins in Schwann cell–axon interaction

Schwann cell–axon interactions are crucial for the myelination during the postnatal development of the brain and body, when axons grow out to make connections with their targets (Niessen et al., 1994; Feltri et al., 1994) (for review, see Previtali et al., 2001). That integrins play a role in this process has been shown using the conditional deletion of the integrin β1 subunit in Schwann cells, resulting in impaired radial sorting of developing axons. Also, the maintenance of extensions of Schwann cells during the premyelinating stage was less efficient (Feltri et al., 2002). The effect lasted into adulthood, because the β1 conditional knock-out mice appeared to have severely impaired motor function on the rotarod and abnormalities in posture and gait. Because some of the axons did become normally myelinated, it was suggested that dystroglycans and/or the α6β4 integrin might partially compensate for the absence of β1 (Feltri et al., 2002). Indeed, in subsequent genetic knock-out studies, it was shown that dystroglycan is also required for achieving normal myelination (Saito et al., 2003; Occhi et al., 2005). Our data suggest that there is also a function of α6β4 in myelination during development, because the number of myelinated axons in the nerves of β4−/− mice is lower than that in wild-type mice. Of interest, it has been shown recently that the integrin α6β4 forms a complex with the tetraspan protein, the peripheral myelin protein 22 (PMP22), and that in the absence of PMP22 the levels of β4 are severely reduced and myelination of peripheral nerves is delayed (Amici et al., 2006). Based on our findings with the β4−/− mice, we would like to suggest that the low levels of β4 contribute to the observed myelination defects seen in the PMP22-deficient mice.

What causes the slower axonal outgrowth in the absence of β4? It is possible that the deposition of laminins or other essential ECM proteins would be disturbed. However, we found the deposition of these proteins to be normal in β4−/− mice. Another possibility might be that α6β4 participates in cell signaling, thus controlling migration, proliferation, and/or survival (Wilhelmsen et al., 2006). For example, impaired signaling might result in a reduced elongation of axons, whereas the lack of both the adhesion and signaling function of β4 might affect the speed of myelination.

Integrins and the myelination process

How does lack of β4 influence myelination? The myelination process appears to be slower during peripheral nerve regeneration in β4−/− mice, with fewer axons being myelinated, whereas the myelin sheaths of the ones that are myelinated are thinner.

The integrin α6β4 is expressed at the abaxonal surface (basal lamina side) of the myelinating Schwann cells, which suggests that α6β4 can support the process of myelination through stable anchoring via extracellular molecules (Feltri et al., 1994; Niessen et al., 1994). The increase in β4 mRNA and, therefore, of α6β4 expression in the developing nerve, occurs well after the peak of Schwann cell proliferation and even after the peak of myelin gene expression. It appears that the function of α6β4 is best defined as supporting growth and particularly maintaining myelin sheaths (Wood and Engel, 1976). The α6β4 integrin is required for the firm adhesion of the Schwann cells to their basement membrane (Clark and Bunge, 1989; Feltri et al., 1994; Niessen et al., 1994). Bunge and coworkers suggested that Schwann cells must be anchored to their basement membrane, to account for the observed restricted movement of Schwann cells relative to the axon during myelination (Bunge et al., 1989). When Schwann cells are anchored in their correct position on the basement membrane by α6β4, regenerating axons will find their proper direction more easily.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that some β4 protein is still present immediately after peripheral nerve injury and that expression of α6β4 in Schwann cells, whose role is to anchor these cells to laminins in the basal lamina, is important for myelination and the recovery of motor nerve function, leading to successful peripheral nerve regeneration.

Footnotes

We thank Marco Giovannini (Inserm, Unité 434, Paris, France) for the P0–cre transgenic mice, Bosco Chan (University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada) for the kind gift of MB1.2 and BMA5 antibodies, Takako Sasaki (Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR) for the antibody against nidogen, Eva Engvall (The Burnham Institute, La Jolla, CA) for the collagen IV antibody, and Lydia Sorokin (Muenster University, Muenster, Germany) for the antibodies against laminin-α2 and laminin-α5, Bjorn Bakker and Iris Schaafsma (Cell Biology, Nijmegen Centre for Molecular Life Sciences, Nijmegen, The Netherlands) for peripheral nerve immunocytochemistry, and Mietske Wijers and Martin Lammens (Cell Biology, Pathology, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands) for electron microscopy expertise.

References

- Amici SA, Dunn WA, Jr, Murphy AJ, Adams NC, Gale NW, Valenzuela DM, Yancopoulos GD, Notterpek L. Peripheral myelin protein 22 is in complex with α6β4 integrin, and its absence alters the Schwann cell basal lamina. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1179–1189. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2618-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunge RP, Bunge MB, Bates M. Movements of the Schwann cell nucleus implicates progression of the inner (axon-related) Schwann cell process during myelination. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:273–284. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZL, Strickland S. Laminin gamma1 is critical for Schwann cell differentiation, axon myelination, and regeneration in the peripheral nerve. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:889–899. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MB, Bunge MB. Cultured Schwann cells assemble normal-appearing basal laminae only when they ensheathe axons. Dev Biol. 1989;133:393–404. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Koning P, Gispen WH. Org 2766 improves functional and electrophysiological aspects of regenerating sciatic nerve in the rat. Peptides. 1987;8:415–422. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(87)90003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Koning P, Brakkee JH, Gispen WH. Methods for producing a reproductive crush in the sciatic and tibial nerve of the rat and rapid precise testing of return of sensory function. Beneficial effect of melanocortins. J Neurol Sci. 1986;74:237–246. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(86)90109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Medinaceli L. Interpreting nerve morphometry data after experimental traumatic lesions. J Neurosci Methods. 1995;58:29–37. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)00156-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Medinaceli L, Freed WJ, Wyatt RJ. An index of the functional condition of rat sciatic nerve based on measurements made from walking tracks. Exp Neurol. 1982;77:634–643. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(82)90234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekström PA, Mayer U, Panjwani A, Pountney D, Pizzey J, Tonge DA. Involvement of α7β1 integrin in the conditioning-lesion effect on sensory axon regeneration. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;22:383–395. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(02)00034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltri ML, Scherer SS, Nemni R, Kamholz J, Vogelbacker H, Scott MO, Canal N, Quaranta V, Wrabetz L. β4 integrin expression in myelinating Schwann cells is polarized, developmentally regulated and axonally dependent. Development. 1994;120:1287–1301. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.5.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltri ML, Graus Porta D, Previtali SC, Nodari A, Migliavacca B, Cassetti A, Littlewood-Evans A, Reichardt LF, Messing A, Quattrini A, Mueller U, Wrabetz L. Conditional disruption of β1 integrin in Schwann cells impedes interactions with axons. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:199–209. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancotti FG, Ruoslahti E. Integrin signalling. Science. 1999;285:1028–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg MH, Partridge A, Shattil SJ. Integrin regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannini M, Robanus-Maandag E, van der Valk M, Niwa-Kawakita M, Abramowski V, Goutebroze L, Woodruff JM, Berns A, Thomas G. Conditional bi-allelic Nf2 mutation in the mouse promotes manifestations of human neurofibromatosis type 2. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1617–1630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenq CB, Coggeshall RE. Effects of sciatic nerve regeneration on axonal populations in tributary nerves. Brain Res. 1984;295:91–100. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90819-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litjens SH, de Pereda JM, Sonnenberg A. Current insights into the formation and breakdown of hemidesmosomes. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:376–383. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison RD, Archibald SJ, Brushart TM. Reinnervation accuracy of the rat femoral nerve by motor and sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5698–5703. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05698.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mears S, Schachner M, Brushart TM. Antibodies to myelin-associated glycoprotein accelerate preferential motor reinnervation. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2003;8:91–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8027.2003.03012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray M. A quantitative study of regenerative sprouting by optic axons in goldfish. J Comp Neurol. 1982;209:352–362. doi: 10.1002/cne.902090405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan R, Le N, Mahoney H, Araki T, Milbrandt J. Deciphering peripheral nerve myelination by using Schwann cell expression profiling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8998–9003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132080999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niessen CM, Cremona O, Daams H, Ferraresi S, Sonnenberg A, Marchisio PC. Expression of the integrin α6β4 in peripheral nerves: localization in Schwann and perineural cells and different variants of the β4 subunit. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:543–552. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.2.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Occhi S, Zambroni D, Del Carro U, Amadio S, Sirkowski EE, Scherer SS, Campbell KP, Moore SA, Chen ZL, Strickland S, Di Muzio A, Uncini A, Wrabetz L, Feltri ML. Both laminin and Schwann cell dystroglycan are necessary for proper clustering of sodium channels at nodes of Ranvier. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9418–9427. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2068-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JH, McKinney L, Azuma M, Spits H, Lanier LL. A novel beta 4, alpha 6 integrin-associated epithelial cell antigen involved in natural killer cell and antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte cytotoxicity. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1571–1581. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.6.1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Previtali SC, Feltri ML, Archelos JJ, Quattrini A, Wrabetz L, Hartung HP. Role of integrins in the peripheral nervous system. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;64:35–49. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond K, Kreft M, Janssen H, Calafat J, Sonnenberg A. Keratinocytes display normal proliferation, survival and differentation in conditional β4-integrin knockout mice. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1045–1060. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito F, Moore SA, Barresi R, Henry MD, Messing A, Ross-Barta SE, Cohn RD, Williamson RA, Sluka KA, Sherman DL, Brophy PJ, Schmelzer JD, Low PA, Wrabetz L, Feltri ML, Campbell KP. Unique role of dystroglycan in peripheral nerve myelination, nodal structure, and sodium channel stabilization. Neuron. 2003;38:747–758. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenberg A, Linders CJ, Daams JH, Kennel SJ. The α6β1 (VLA-6) and α6β4 protein complexes: tissue distribution and biochemical properties. J Cell Sci. 1990;96:207–217. doi: 10.1242/jcs.96.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Flier A, Sonnenberg A. Function and interactions of integrins. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;305:285–298. doi: 10.1007/s004410100417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Zee CE, Brakkee JH, Gispen WH. Putative neurotrophic factors and functional recovery from peripheral nerve damage in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;103:1041–1046. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12297.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Zee CE, Man TY, Van Lieshout EM, Van der Heijden I, Van Bree M, Hendriks WJ. Delayed peripheral nerve regeneration and central nervous system collateral sprouting in leucocyte common antigen-related protein tyrosine phosphatase deficient mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:991–1005. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meeteren NL, Brakkee JH, Hamers FP, Helders PJ, Gispen WH. Exercise training improves functional recovery and motor nerve conduction velocity after sciatic nerve crush lesion in the rat. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:70–77. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelezang MG, Liu Z, Relvas JB, Raivich G, Scherer SS, ffrench-Constant C. α4 integrin is expressed during peripheral nerve regeneration and enhances neurite outgrowth. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6732–6744. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06732.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink DG, Peters W, Schaafsma I, Sutmuller RP, Oerlemans F, Adema GJ, Wieringa B, van der Zee CE, Hendriks W. Mild impairment in motor nerve repair in mice lacking PTP-BL tyrosine phosphatase activity. Physiol Genomics. 2004;19:50–60. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00079.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner A, Willem M, Jones LL, Kreutzberg GW, Mayer U, Raivich G. Impaired axonal regeneration in α7 integrin deficient mice. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1822–1830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01822.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsen K, Litjens SH, Sonnenberg A. Multiple functions of the integrin α6β4 in epidermal homeostasis and tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2877–2886. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.8.2877-2886.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsen K, Litjens SH, Kuikman I, Margadant C, van Rheenen J, Sonnenberg A. Serine phosphorylation of the integrin β4 subunit is necessary for epidermal growth factor receptor induced hemidesmosome disruption. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3512–3522. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-04-0306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JG, Engel EL. Peripheral nerve glycoproteins and myelin fine structure during development of rat sciatic nerve. J Neurocytol. 1976;5:605–615. doi: 10.1007/BF01175573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]