Abstract

Basal forebrain neurons play an important role in memory and attention. In addition to cholinergic and GABAergic neurons, glutamatergic neurons and neurons that can corelease acetylcholine and glutamate have recently been described in the basal forebrain. Although it is well known that nerve growth factor (NGF) promotes synaptic function of cholinergic basal forebrain neurons, how NGF affects the newly identified basal forebrain neurons remains undetermined. Here, we examined the effects of NGF on synaptic transmission of medial septum and diagonal band of Broca (MS-DBB) neurons expressing different neurotransmitter phenotypes. We used MS-DBB neurons from 10- to 13-d-old rats, cultured on astrocytic microislands to promote the development of autaptic connections. Evoked and spontaneous postsynaptic currents were recorded, and neurotransmitters released were characterized pharmacologically. We found that chronic exposure to NGF significantly increased acetylcholine and glutamate release from cholinergic MS-DBB neurons, whereas glutamate and GABA transmission from noncholinergic MS-DBB neurons were not affected by NGF. Interestingly, the NGF-induced increase in neurotransmission was mediated by p75NTR. These results demonstrate a previously unidentified role of NGF and its receptor p75NTR; their interactions are crucial for cholinergic and glutamatergic transmission in the septohippocampal pathway.

Keywords: corelease, p75NTR, acetylcholine, glutamate, NGF (nerve growth factor), septum

Introduction

Neurons of the medial septum and diagonal band of Broca (MS-DBB) project to the hippocampus, modulating its activity and providing important input for cognitive functions such as memory (Winson, 1978). Until recently, the MS-DBB has been thought to consist only of cholinergic and GABAergic neurons. We now know that the MS-DBB also contains glutamatergic neurons (Colom et al., 2005) and neurons that coexpress markers for multiple neurotransmitter phenotypes (Sotty et al., 2003), indicating that some neurons have the molecular capacity to corelease multiple transmitters. Indeed, cultured basal forebrain neurons have recently been demonstrated to release acetylcholine and glutamate simultaneously (Allen et al., 2006). Nerve growth factor (NGF) is a potent neurotrophin for cholinergic MS-DBB neurons, promoting their survival, neurite outgrowth, and cholinergic phenotype expression (Hartikka and Hefti, 1988). However, with the recent discovery of glutamatergic neurons and neurons expressing multiple neurotransmitter phenotypes, NGF's role in the MS-DBB needs to be reevaluated.

The currently held view is that noncholinergic MS-DBB neurons are not affected by NGF, because few of them express receptors for NGF. In the MS-DBB, virtually all neurons expressing trkA and p75NTR are cholinergic (Sobreviela et al., 1994). In addition, NGF has shown potent survival-promoting effects on cholinergic, but not GABAergic, septal neurons (Montero and Hefti, 1988). However, effects of NGF on glutamatergic MS-DBB neurons and cholinergic neurons that corelease acetylcholine and glutamate remain unknown. Examination of this issue is important because NGF signaling is impaired from early stages of Alzheimer's disease (AD) (Salehi et al., 2003), and NGF replacement therapy has emerged as a new treatment for AD (Tuszynski et al., 2005).

The aim of this study is to investigate the effects of NGF on synaptic transmission of MS-DBB neurons releasing different neurotransmitters and to examine the mechanisms underlying the action of NGF. We demonstrate here that NGF increases both acetylcholine and glutamate transmission from cholinergic MS-DBB neurons and that these effects are mediated by p75NTR.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture.

Autaptic cultures were prepared according to Congar et al. (2002) with some modifications. All drugs were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), unless otherwise noted. Animals were treated according to protocols and guidelines approved by McGill University and the Canadian Council of Animal Care. Astrocytic microislands were first established, and then MS-DBB neurons were cultured on the microislands. Briefly, glass coverslips were treated with poly-l-ornithine and agarose and sprayed with liquid collagen (Cohesion Technology, Palo Alto, CA) using a microatomizer to create microislands permissive to cell growth. To obtain astrocytes, we extracted hippocampal tissue from 1-d-old Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River, St. Constant, Quebec, Canada) and dissociated the tissue using papain (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ). Cells were grown in flasks with media containing basal medium Eagle, glucose, Mito+ serum extender (Becton Dickinson Labware, Bedford, MA), penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, Burlington, Ontario, Canada), GlutaMAX-1 (Invitrogen), and 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Invitrogen). After 48 h of incubation (37°C/5% CO2), astrocytes were exposed to cold (4°C) media and vigorous shaking to eliminate any surviving neurons and loosely attached cells. The remaining astrocytes were allowed to further proliferate, harvested, and plated at 60,000 living cells/ml on pretreated coverslips. 5-Fluoro-2′deoxyuridine (FDU) was added to inhibit further proliferation. Next, MS-DBB neurons were obtained from 10- to 13-d-old rats, dissociated, and plated at 80,000 living cells/ml on preestablished astrocytic microislands. The neurons were cultured in media containing astrocyte-conditioned media, Neurobasal-A (Invitrogen), penicillin/streptomycin, GlutaMAX-1, B-27 (Invitrogen), and 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum. Media was changed after 24 h, at which point additional FDU was administered, and fresh media were added every seventh day.

Electrophysiology and p75NTR labeling.

Twenty-four hours before recording, MS-DBB neurons were treated with a fluorescent p75NTR antibody, 192IgG-Cy3 (Advanced Targeting Systems, San Diego, CA) (0.3 μg/ml), to identify cholinergic neurons. Before recording, neurons were illuminated at a 530 nm excitation wavelength using a fluorescence system (PTI, Monmouth Junction, NJ) to check for the presence of Cy3 labeling in the soma. The diameter of the neuron's soma was estimated using grids in the visual field of the microscope. Electrophysiological recordings were performed on neurons cultured for 16–30 d. Extracellular solution containing (in mm) 140 NaCl, 10 glucose, 6 sucrose, 3 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, and 10 HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.3 with NaOH, was perfused at 1–2 ml/min. Neurons were visualized using a 20× water-immersion objective on an upright BX51W1 Olympus (Tokyo, Japan) microscope, Nomarski optics, and an infrared camera. Microislands were visually inspected to ensure that recordings were done on astrocytic islands that contained only one neuron. Recordings were performed using an Axopatch-1C amplifier and pClamp9 software (Molecular Devices, Foster City, CA). Pipette resistance was 4–6 MΩ. The intrapipette solution contained (in mm) 144 K-gluconate, 10 HEPES, 3 MgCl2, 2 Na2ATP, 0.3 GTP, and 0.2 EGTA, adjusted to pH 7.2 with KOH. Pipettes were visually guided to isolated neurons, and neurons were recorded using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique. Tubocurarine (10 μm), kynurenic acid (1 mm), 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3(1H,4H)-dione (DNQX) (50 μm), and/or bicuculline methiodide/chloride (50 μm) were bath applied using a six-channel pressure regulator, to identify the released neurotransmitters.

Miniature EPSCs (mEPSCs) were recorded using a modified extracellular solution containing (in mm) 140 NaCl, 10 glucose, 6 sucrose, 5 KCl, 2.8 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, and 10 HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.3 with NaOH. After confirming that a neuron was cholinergic (Cy3 label in the soma) and that it displayed an EPSC, recordings were performed in the presence of tetrodotoxin (0.5 μm) and bicuculline (10 μm). Our preliminary results revealed that autaptic neurons displayed little spontaneous events, making it extremely difficult to obtain sufficient data from each neuron. Thus, experiments were performed in the presence of a Ca2+ ionophore, ionomycin (2.5 μm), which induces transmitter release by increasing calcium influx into axon terminals (Congar et al., 2002). We observed that within minutes of ionomycin application, the frequency of mEPSCs increased and plateaued. Once the frequency of mEPSCs stabilized, a fixed number (13) of consecutive mEPSCs was taken to represent each neuron and analyzed using MiniAnalysis 6.0.3 software (Synaptosoft, Leonia, NJ).

NGF, K252a, and MLR2/3 treatments.

Mouse NGF (grade I; Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) (25 ng/ml) dissolved in Neurobasal-A was administered to one group of neurons on the first day of culture and twice weekly thereafter. Another group of neurons received only vehicle (Neurobasal-A) to serve as controls. NGF concentration of 25 ng/ml was chosen because it was previously shown to effectively increase acetylcholine release from cultured basal forebrain neurons (Auld et al., 2001) and it is similar to the concentration of NGF found in the hippocampus of adult rats in vivo (27 ng/g wet weight) (Shetty et al., 2003). In some experiments, neurons were treated with a trk inhibitor, K252a (Alomone Labs) (200 nm), or with a mixture of MLR2 and MLR3, function-blocking p75NTR antibodies (10 μg/ml). In cases in which K252a or MLR2/3 was coadministered with NGF, the inhibitor was applied 30 min before NGF. When MLR2/3 was used, neurons could not be labeled with 192IgG-Cy3 because residual MLR2/3 prevented 192IgG-Cy3 from binding to p75NTR. Therefore, in these experiments, only neurons displaying an autaptic nicotinic current were considered to be “cholinergic.” MLR2 and MLR3 were kindly provided by Dr. Mary-Louise Rogers (Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia).

Results

NGF selectively increased synaptic transmission from cholinergic MS-DBB neurons

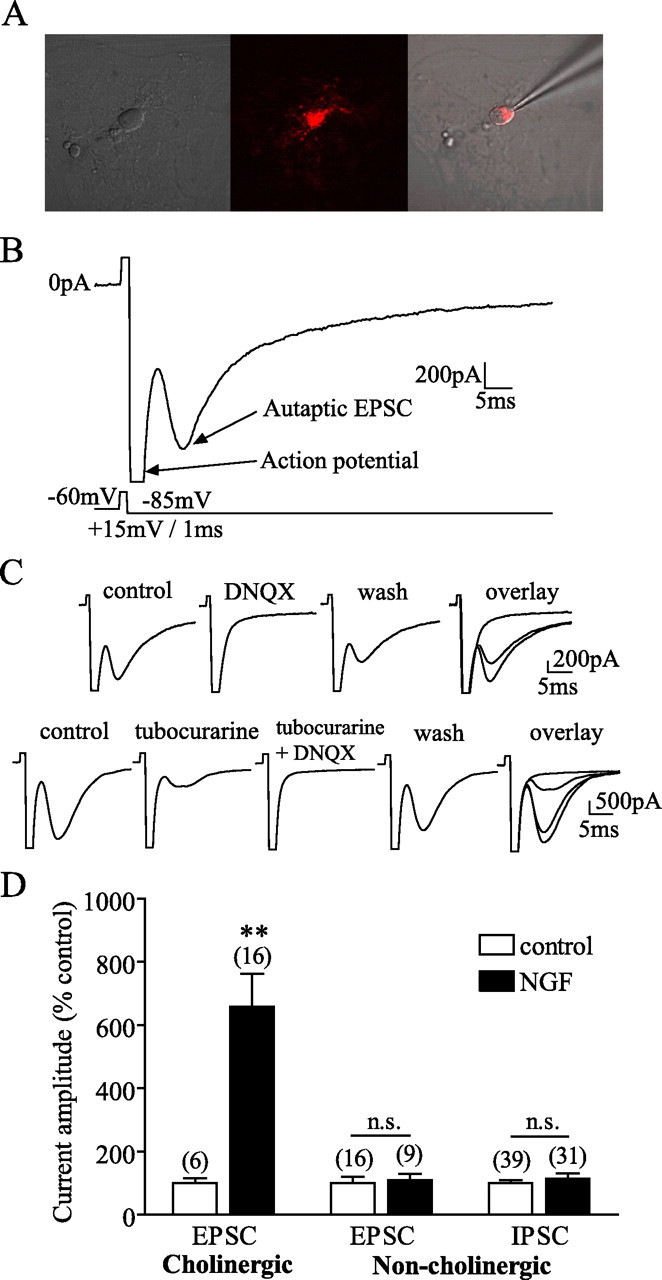

Because our aim was to examine the effects of NGF on different types of MS-DBB neurons, we first tested how NGF affects synaptic function of cholinergic versus noncholinergic MS-DBB neurons. p75NTR is selectively expressed by cholinergic neurons in the MS-DBB (Sobreviela et al., 1994), so we used 192IgG-Cy3, a fluorescent antibody against p75NTR, to facilitate the identification of cholinergic neurons as demonstrated previously (Wu et al., 2000). MS-DBB neurons labeled with the antibody were thus assumed to be “cholinergic,” and unlabeled neurons were considered “noncholinergic.” Figure 1A shows an isolated MS-DBB neuron labeled with 192IgG-Cy3. Autaptic currents were recorded by holding a neuron in voltage clamp at −60 mV, depolarizing it to +15 mV for 1 ms to evoke an action potential, and then holding it at −85 mV for 150 ms to reveal the postsynaptic autaptic current (Fig. 1B). The peak amplitude of the current was measured while the membrane was held at −85 mV. The current was considered to be an EPSC if its reversal potential was near 0 mV and an IPSC if it reversed at a potential more negative than −40 mV. We then determined the neurotransmitters released by each neuron using the following protocol. In voltage clamp, the neuron was stimulated to fire an action potential, and its membrane was held at −80 mV to observe the autaptic current, and the protocol was repeated every 60 s. Once a stable baseline for the current was obtained, drugs were applied to block currents mediated by nicotinic receptors (tubocurarine), ionotropic glutamate receptors (kynurenic acid or DNQX), or GABAA receptors (bicuculline).

Figure 1.

NGF selectively increased synaptic transmission from cholinergic MS-DBB neurons. A, An isolated cholinergic neuron displaying 192IgG-Cy3 (red) label in the soma. B, Autaptic neurons were held in voltage clamp and stimulated to fire an action potential, resulting in neurotransmitter release and postsynaptic autaptic currents. An example of a cholinergic neuron displaying an autaptic EPSC is shown. C, Top, A cholinergic neuron exhibited an EPSC blocked by 50 μm DNQX, indicating that the neuron released glutamate. Bottom, Another cholinergic neuron displayed an EPSC that was partially reduced by 10 μm tubocurarine but completely inhibited when both tubocurarine and DNQX were applied, demonstrating that the neuron coreleased acetylcholine and glutamate. D, Cholinergic neurons cultured with NGF expressed EPSCs with larger amplitudes than control cholinergic neurons. NGF did not affect the amplitude of EPSCs or IPSCs in noncholinergic neurons. Numbers in brackets are the number of neurons, and error bars represent SEM in all figures. n.s., p > 0.05. **p < 0.01.

We found that of 52 cholinergic MS-DBB neurons, 16 displayed EPSCs mediated by glutamate, 6 showed EPSCs mediated by acetylcholine, and 20 exhibited EPSCs mediated by both glutamate and acetylcholine. The remaining 10 displayed currents mediated by both glutamate and GABA (5 neurons), by acetylcholine and GABA (1 neuron), GABA only (2 neurons), or by all three transmitters together (2 neurons). Figure 1C shows an EPSC displayed by a cholinergic neuron mediated by glutamate (completely and reversibly blocked by DNQX) (top) and an EPSC exhibited by another cholinergic neuron that contained both glutamatergic and cholinergic components (EPSC was only partially inhibited by tubocurarine but completely blocked by both tubocurarine and DNQX, indicating that the neuron coreleased acetylcholine and glutamate) (bottom). Of 66 noncholinergic MS-DBB neurons, 43 showed IPSCs mediated by GABA, whereas the remaining 23 exhibited glutamate-mediated EPSCs.

When we investigated the effects of chronic exposure to NGF on synaptic transmission of these neurons, we found that control cholinergic neurons exhibited EPSCs that were −242.8 ± 52.76 (SE) pA in amplitude (6 neurons), whereas cholinergic neurons exposed to NGF displayed EPSCs that were −1415 ± 192.9 pA (16 neurons). Thus, NGF significantly increased the amplitude of EPSCs in cholinergic neurons (t test, p = 0.0045) (Fig. 1D). In contrast, noncholinergic MS-DBB neurons were not significantly affected by NGF in the amplitude of their EPSCs (−1037 ± 233.6 pA in 16 control neurons, −1253 ± 289.7 pA in 9 NGF neurons; t test, p = 0.7674) or IPSCs (−314.0 ± 29.36 pA in 39 control neurons, −365.3 ± 44.89 pA in 31 NGF neurons; t test, p = 0.4283) (Fig. 1D), demonstrating that NGF selectively enhanced synaptic transmission from cholinergic neurons.

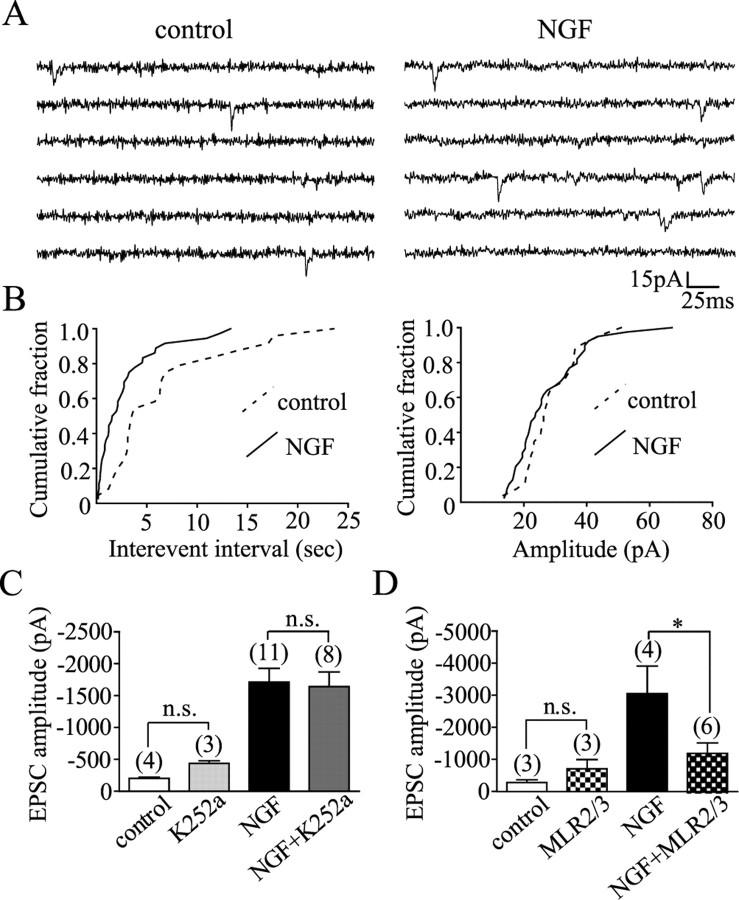

Mechanisms of NGF action

We next explored the nature of synaptic changes induced by NGF in cholinergic MS-DBB neurons. To detect mEPSCs, we held cholinergic neurons at −70 mV in voltage clamp and recorded the changes in current (Fig. 2A). We found that NGF significantly decreased the interevent interval of mEPSCs (5.53 ± 1.01 s in control vs 2.88 ± 0.56 s in NGF; Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, p = 0.0043) (Fig. 2B, left) without affecting the amplitude of mEPSCs (27.77 ± 1.78 pA in control vs 27.36 ± 1.84 pA in NGF; Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, p = 0.8931) (Fig. 2B, right). Therefore, NGF increased the frequency but not the amplitude of miniature events, indicating that NGF enhanced neurotransmitter release but not likely the density of postsynaptic receptors.

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of NGF action. A, Example traces showing mEPSCs from cholinergic neurons grown in control (left) versus NGF condition (right). B, Kolmogorov–Smirnov graphs illustrate that NGF decreased the interevent interval (left) without altering the amplitude (right) of mEPSCs in cholinergic neurons (n = 2 control, 3 NGF neurons). C, D, MLR2/3 (p75NTR-antibodies), but not K252a (trk inhibitor), prevented NGF-induced increase in the amplitude of EPSCs in cholinergic neurons. n.s., p > 0.05. *p < 0.05.

We then asked which NGF receptor, trkA or p75NTR, is involved in NGF action. We used a trk inhibitor K252a to examine the role of trkA, and a mixture of MLR2 and MLR3, monoclonal antibodies for p75NTR, to test the role of p75NTR. The MLR antibodies have been confirmed to bind rat p75NTR and to inhibit the effects of NGF mediated through p75NTR (Rogers et al., 2006). Two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni posttests revealed that K252a failed to reduce the NGF-induced increase in the amplitude of EPSCs in cholinergic neurons (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2C), whereas MLR2/3 successfully blocked the effect (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2D). We also found that K252a or MLR2/3 alone did not significantly alter the amplitude of EPSCs compared with control (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2C,D). These findings suggest that p75NTR, not trkA, mediated the NGF-induced increase in synaptic transmission from cholinergic MS-DBB neurons.

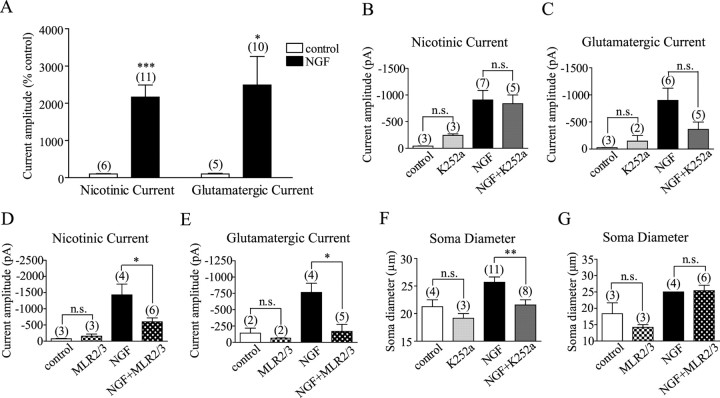

NGF increased both acetylcholine and glutamate transmission from cholinergic neurons via p75NTR

Since the majority of cholinergic MS-DBB neurons in our study were demonstrated to release acetylcholine, glutamate, or corelease the two transmitters, we examined whether NGF differentially affects acetylcholine versus glutamate transmission from these neurons. To do this, we pharmacologically isolated cholinergic and glutamatergic components of EPSCs recorded from cholinergic neurons; the EPSC component blocked by tubocurarine was considered to be a nicotinic current (indicative of cholinergic transmission), while the EPSC component sensitive to kynurenic acid or DNQX was regarded as a glutamatergic current. After comparing nicotinic and glutamatergic currents displayed by cholinergic neurons, we found that NGF increased the amplitude of nicotinic currents by 2065 ± 323.3% (n = 6 control, 11 NGF neurons, t test, p = 0.0003) and glutamatergic currents by 2390 ± 765.9% (n = 5 control, 10 NGF neurons, t test, p = 0.0496) (Fig. 3A), showing that NGF increased both acetylcholine and glutamate transmission from cholinergic MS-DBB neurons.

Figure 3.

NGF increased both acetylcholine and glutamate transmission from cholinergic neurons via p75NTR. A, Cholinergic neurons exposed to NGF displayed larger nicotinic and glutamatergic currents than controls. B, C, K252a did not affect NGF-induced increases in nicotinic or glutamatergic currents. D, E, MLR2/3 significantly reduced the effects of NGF on nicotinic and glutamatergic currents. F, G, Cholinergic neurons grown in NGF had significantly larger cell bodies compared with controls. The effect of NGF on soma size was blocked by K252a, but not by MLR2/3. n.s., p > 0.05. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

We next aimed to test whether NGF-induced increases in acetylcholine and glutamate transmission were both mediated by p75NTR. Two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni posttests showed that inhibiting trkA activity with K252a failed to prevent NGF-mediated increases in nicotinic and glutamatergic currents (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3B,C), whereas blocking p75NTR with MLR2/3 significantly reduced the effects of NGF on both currents (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3D,E). Administering K252a or MLR2/3 per se had no significant effects on nicotinic or glutamatergic currents (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3 B–E). These results indicate that NGF increased both acetylcholine and glutamate transmission via p75NTR-mediated mechanisms.

Because K252a failed to prevent NGF-mediated increases in synaptic transmission from cholinergic neurons, we tested the effectiveness of the antagonist by examining, in the same cultures, whether K252a inhibited a well known trophic action of NGF on the soma size of cholinergic neurons (Hartikka and Hefti, 1988). We found that NGF indeed increased the soma size of cholinergic neurons (p < 0.05) and that this effect was blocked by K252a (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3F), but not by MLR2/3 (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3G), indicating that the effect of NGF on soma size was mediated by trkA.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates, for the first time, that long-term exposure to NGF increases acetylcholine release from individual cholinergic MS-DBB neurons, and that NGF enhances acetylcholine and glutamate transmission from those cholinergic neurons expressing both neurotransmitter phenotypes. We report that the effects of NGF are unique to cholinergic neurons and that the NGF-induced increase in synaptic transmission requires p75NTR-mediated signaling.

Many previous reports have demonstrated that NGF increases the expression of acetylcholine-related enzymes, such as choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), acetylcholinesterase, and vesicular acetylcholine transporter in basal forebrain cultures (Hartikka and Hefti, 1988; Takei et al., 1997). Although these studies illustrate NGF's ability to enhance cholinergic phenotype expression, they do not provide direct evidence as to whether NGF increases functional release of acetylcholine from these neurons. The few studies that have examined this issue reported, using HPLC quantification, that NGF increases spontaneous and K+-evoked acetylcholine release from high-density cultures of basal forebrain neurons (Takei et al., 1989; Auld et al., 2001). Here, we provide electrophysiological evidence that exposure to NGF indeed increases the amount of acetylcholine released by single cholinergic MS-DBB neurons. Moreover, we report that NGF does not affect glutamate or GABA release by noncholinergic MS-DBB neurons, consistent with previous studies that also found no significant effects of NGF on noncholinergic septal neurons (Montero and Hefti, 1988; Wu and Yeh, 2005). As for the nature of synaptic changes induced by NGF, we demonstrate that NGF increases the frequency but not the amplitude of miniature EPSCs, indicating that the site of change is presynaptic rather than postsynaptic. This suggests that NGF enhances neurotransmitter release by increasing the number of active synapses and/or transmitter release sites.

A major proportion (20/52) of cholinergic MS-DBB neurons in our study expressed EPSCs mediated by both acetylcholine and glutamate, indicating that many cholinergic neurons can functionally corelease acetylcholine and glutamate. Using similar methods, Allen et al. (2006) also found that all (6/6) magnocellular basal forebrain neurons that released glutamate coreleased acetylcholine. Despite these in vitro results, whether MS-DBB neurons corelease multiple neurotransmitters in vivo remains unknown. Previous studies using in situ techniques have estimated that 4–36% of cholinergic MS-DBB neurons coexpress glutamatergic phenotype (Sotty et al., 2003; Colom et al., 2005). The expression of corelease has been proposed to be regulated by multiple factors, including developmental stage, excitability state, and exposure to neurotrophins (Gutierrez, 2005). Interestingly, we observed that 29% of cholinergic MS-DBB neurons coreleased acetylcholine and glutamate in control versus 48% in NGF. To demonstrate functional corelease in vivo, a study using paired recordings of synaptically connected MS-DBB neurons in the acute slice should be done to help resolve the issue. Nonetheless, our results show that under a condition in which many cholinergic MS-DBB neurons coexpress glutamatergic phenotype, NGF enhances not only acetylcholine but also glutamate transmission from these neurons. It is unclear why many p75NTR-bearing “cholinergic” neurons in our study failed to display observable acetylcholine-mediated autaptic currents. A possible explanation may be that the density of postsynaptic nicotinic receptors was too low in some neurons to allow detection of acetylcholine being released (Allen et al., 2006), or some cholinergic neurons simply did not establish functional cholinergic synapses.

We demonstrate that NGF enhances synaptic transmission from cholinergic MS-DBB neurons via p75NTR. Few studies have looked at the NGF receptor involved in the chronic (multiday) effects of NGF on cholinergic transmission in basal forebrain neurons. Knusel and Hefti (1991) showed that 5 d exposure to NGF increased ChAT activity in embryonic basal forebrain neurons via trkA. Madziar et al. (2005) reported that 3 d NGF treatment increased acetylcholine content in embryonic septal neurons via PI3K–Akt pathway. It is important to note that in contrast to these studies, we measured functional release of acetylcholine from single neurons and used more mature MS-DBB neurons (postnatal day 10–13 neurons) and longer exposure times to NGF (16–30 d). It is possible that the mechanisms underlying NGF's effects on ChAT activity may differ from those involved in regulating acetylcholine release, and mechanisms may also change with development and with different NGF treatments. It has been suggested that K252a's ineffectiveness may be attributable to the lack of trkA expression in some cholinergic neurons. However, this is highly unlikely because our results clearly demonstrate that different effects of NGF were mediated by different NGF receptors in the same neurons, indicating that the cholinergic neurons expressed both p75NTR and trkA. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that virtually all (>95%) cholinergic neurons express trkA in the rat MS-DBB (Sobreviela et al., 1994). Our finding that p75NTR, not trk, is involved in the effect of a neurotrophin on synaptic transmission is not without precedent. NGF has been shown to increase, via p75NTR-mediated mechanisms, glutamate release from cerebellar neurons (Numakawa et al., 2003) and dopamine release from mesencephalic neurons (Blochl and Sirrenberg, 1996). BDNF has also been demonstrated to increase acetylcholine release from sympathetic neurons through p75NTR (Yang et al., 2002).

Our findings have several important functional implications. Accumulating evidence suggests that dysfunctional NGF signaling is implicated in Alzheimer's disease (AD). Individuals with early to late stages of AD display reductions in trkA and p75NTR expression that are correlated with their performance on memory tests (Salehi et al., 2003). In addition, NGF replacement therapy has emerged as a potential treatment for AD. In a recent phase-1 clinical trial, implanting NGF-producing fibroblasts into the basal forebrain of AD patients has been found to significantly slow the rate of cognitive decline and increase cortical glucose uptake (Tuszynski et al., 2005). Our findings suggest that dysfunctional NGF signaling in AD may cause reductions in both acetylcholine and glutamate release from septal cholinergic neurons, and that both changes may contribute to the cognitive deficits associated with AD. Conversely, increasing NGF levels in the brain may enhance both cholinergic and glutamatergic transmission in the septohippocampal circuit, improving cognitive functions.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and Alzheimer's Society of Canada. We thank Dr. Mary-Louise Rogers at Flinders University (Adelaide, Australia) for the p75NTR-antibodies, MLR2, and MLR3.

References

- Allen TG, Abogadie FC, Brown DA. Simultaneous release of glutamate and acetylcholine from single magnocellular “cholinergic” basal forebrain neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1588–1595. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3979-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auld DS, Mennicken F, Day JC, Quirion R. Neurotrophins differentially enhance acetylcholine release, acetylcholine content and choline acetyltransferase activity in basal forebrain neurons. J Neurochem. 2001;77:253–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.t01-1-00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blochl A, Sirrenberg C. Neurotrophins stimulate the release of dopamine from rat mesencephalic neurons via Trk and p75Lntr receptors. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21100–21107. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.35.21100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colom LV, Castaneda MT, Reyna T, Hernandez S, Garrido-Sanabria E. Characterization of medial septal glutamatergic neurons and their projection to the hippocampus. Synapse. 2005;58:151–164. doi: 10.1002/syn.20184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congar P, Bergevin A, Trudeau LE. D2 receptors inhibit the secretory process downstream from calcium influx in dopaminergic neurons: implication of K+ channels. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:1046–1056. doi: 10.1152/jn.00459.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez R. The dual glutamatergic-GABAergic phenotype of hippocampal granule cells. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartikka J, Hefti F. Development of septal cholinergic neurons in culture: plating density and glial cells modulate effects of NGF on survival, fiber growth, and expression of transmitter-specific enzymes. J Neurosci. 1988;8:2967–2985. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-08-02967.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knusel B, Hefti F. K-252b is a selective and nontoxic inhibitor of nerve growth factor action on cultured brain neurons. J Neurochem. 1991;57:955–962. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb08243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madziar B, Lopez-Coviella I, Zemelko V, Berse B. Regulation of cholinergic gene expression by nerve growth factor depends on the phosphatidylinositol-3′-kinase pathway. J Neurochem. 2005;92:767–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero CN, Hefti F. Rescue of lesioned septal cholinergic neurons by nerve growth factor: specificity and requirement for chronic treatment. J Neurosci. 1988;8:2986–2999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-08-02986.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numakawa T, Nakayama H, Suzuki S, Kubo T, Nara F, Numakawa Y, Yokomaku D, Araki T, Ishimoto T, Ogura A, Taguchi T. Nerve growth factor-induced glutamate release is via p75 receptor, ceramide, and Ca(2+) from ryanodine receptor in developing cerebellar neurons. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41259–41269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers ML, Atmosukarto I, Berhanu DA, Matusica D, Macardle P, Rush RA. Functional monoclonal antibodies to p75 neurotrophin receptor raised in knockout mice. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;158:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi A, Delcroix JD, Mobley WC. Traffic at the intersection of neurotrophic factor signaling and neurodegeneration. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:73–80. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(02)00038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty AK, Zaman V, Shetty GA. Hippocampal neurotrophin levels in a kainate model of temporal lobe epilepsy: a lack of correlation between brain-derived neurotrophic factor content and progression of aberrant dentate mossy fiber sprouting. J Neurochem. 2003;87:147–159. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobreviela T, Clary DO, Reichardt LF, Brandabur MM, Kordower JH, Mufson EJ. TrkA-immunoreactive profiles in the central nervous system: colocalization with neurons containing p75 nerve growth factor receptor, choline acetyltransferase, and serotonin. J Comp Neurol. 1994;350:587–611. doi: 10.1002/cne.903500407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotty F, Danik M, Manseau F, Laplante F, Quirion R, Williams S. Distinct electrophysiological properties of glutamatergic, cholinergic and GABAergic rat septohippocampal neurons: novel implications for hippocampal rhythmicity. J Physiol (Lond) 2003;551:927–943. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.046847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei N, Tsukui H, Hatanaka H. Intracellular storage and evoked release of acetylcholine from postnatal rat basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in culture with nerve growth factor. J Neurochem. 1989;53:1405–1410. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb08531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei N, Kuramoto H, Endo Y, Hatanaka H. NGF and BDNF increase the immunoreactivity of vesicular acetylcholine transporter in cultured neurons from the embryonic rat septum. Neurosci Lett. 1997;226:207–209. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00284-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuszynski MH, Thal L, Pay M, Salmon DP, HS U, Bakay R, Patel P, Blesch A, Vahlsing HL, Ho G, Tong G, Potkin SG, Fallon J, Hansen L, Mufson EJ, Kordower JH, Gall C, Conner J. A phase 1 clinical trial of nerve growth factor gene therapy for Alzheimer disease. Nat Med. 2005;11:551–555. doi: 10.1038/nm1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winson J. Loss of hippocampal theta rhythm results in spatial memory deficit in the rat. Science. 1978;201:160–163. doi: 10.1126/science.663646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CW, Yeh HH. Nerve growth factor rapidly increases muscarinic tone in mouse medial septum/diagonal band of Broca. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4232–4242. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4957-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Shanabrough M, Leranth C, Alreja M. Cholinergic excitation of septohippocampal GABA but not cholinergic neurons: implications for learning and memory. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3900–3908. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03900.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Slonimsky JD, Birren SJ. A rapid switch in sympathetic neurotransmitter release properties mediated by the p75 receptor. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:539–545. doi: 10.1038/nn0602-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]