Abstract

Drosophila has robust behavioral plasticity to avoid or prefer the odor that predicts punishment or food reward, respectively. Both types of plasticity are mediated by the mushroom body (MB) neurons in the brain, in which various signaling molecules play crucial roles. However, important yet unresolved molecules are the receptors that initiate aversive or appetitive learning cascades in the MB. We have shown previously that D1 dopamine receptor dDA1 is highly enriched in the MB neuropil. Here, we demonstrate that dDA1 is a key receptor that mediates both aversive and appetitive learning in pavlovian olfactory conditioning. We identified two mutants, dumb1 and dumb2, with abnormal dDA1 expression. When trained with the same conditioned stimuli, both dumb alleles showed negligible learning in electric shock-mediated conditioning while they exhibited moderately impaired learning in sugar-mediated conditioning. These phenotypes were not attributable to anomalous sensory modalities of dumb mutants because their olfactory acuity, shock reactivity, and sugar preference were comparable to those of control lines. Remarkably, the dumb mutant's impaired performance in both paradigms was fully rescued by reinstating dDA1 expression in the same subset of MB neurons, indicating the critical roles of the MB dDA1 in aversive as well as appetitive learning. Previous studies using dopamine receptor antagonists implicate the involvement of D1/D5 receptors in various pavlovian conditioning tasks in mammals; however, these have not been supported by the studies of D1- or D5-deficient animals. The findings described here unambiguously clarify the critical roles of D1 dopamine receptor in aversive and appetitive pavlovian conditioning.

Keywords: dopamine receptor, pavlovian conditioning, punishment, reward, mushroom body neurons, learning memory

Introduction

Pavlovian (classical) olfactory conditioning tests the animal's ability to learn and remember the odor [conditioned stimulus (CS)] associated with diverse unconditioned stimuli (US) in Drosophila and is instrumental in investigating the neural and cellular mechanisms underlying distinct learning and memory processes. When subjected to concurrent odor (CS+) and electric shock (aversive US) presentation, flies learn to avoid the CS+ odor in the absence of shock. Conversely, flies learn to prefer the CS+ odor after concurrent odor (CS+) and sugar (appetitive US) exposure. Thus, the same CS+ triggers either avoidance or preference behavior depending on previous experience of the flies. Several key questions arise regarding the underlying mechanisms. Specifically, are common or separate neural systems required for aversive versus appetitive learning and memory? What are the critical molecular and cellular events that distinguish reward versus punishment information?

Two key components are essential for both aversive and appetitive conditioning. One component is the cAMP signaling pathway. Flies defective in cAMP metabolism, such as dunce (cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase) and rutabaga [rut; calcium/calmodulin (CaM)-dependent adenylyl cyclase (AC)], or flies with altered activities of cAMP effectors protein kinase A and dCREB2 are impaired in learning and/or memory in aversive conditioning (for review, see Davis, 2005). Likewise, appetitive conditioning requires cAMP because rut mutants display poor learning (Schwaerzel et al., 2003). The other component is the mushroom body (MB) brain structure. Flies with ablated MB structures or functions are completely defective in aversive learning (de Belle and Heisenberg, 1994; Connolly et al., 1996). Moreover, synaptic output of different MB lobes is involved in memory formation or retrieval in aversive and appetitive conditioning (Dubnau et al., 2001; McGuire et al., 2003; Schwaerzel et al., 2003; Isabel et al., 2004; Krashes et al., 2007). These indicate the MB as a central neural substrate for olfactory learning and memory. This poses a fundamental question regarding the neuromodulators and their receptors that initiate the cAMP cascade in the MB for aversive and appetitive learning and their memories.

The neuromodulators that are crucial for olfactory conditioning and activate cAMP increases are dopamine and octopamine. Previous studies of Drosophila larvae and adults show that dopaminergic neuronal activities are essential for aversive, but not for appetitive, learning, whereas octopamine or octopaminergic neuronal activities are necessary only for appetitive learning (Schwaerzel et al., 2003; Schroll et al., 2006). Consistently, the activities of dopaminergic neurons projecting to the MB are mildly increased by odor stimuli and strongly by electric shock (Riemensperger et al., 2005). Moreover, duration of their activities is prolonged when the CS+ odor is presented, suggesting the role of dopamine neurons in US prediction. However, it is yet unknown whether dopamine directly activates the MB for aversive learning. To uncover the signal(s) activating the learning and memory cascade, we previously identified three receptors that are highly enriched in the MB and increase cAMP levels, and they are two dopamine receptors, dDA1 and DAMB, and an octopamine receptor, OAMB (Han et al., 1996, 1998; Kim et al., 2003). Here, we show that dDA1 is required in the MB for aversive and appetitive learning.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila stocks and culture.

Wild-type Canton-S and isogenic w1118 were used as controls. The control, deficiency, and inversion lines used in this study were obtained from the Bloomington stock center and f02676 from the Harvard Exelixis stock collection. MB247-GAL4, Elav-GAL4, and GAL80ts lines were kindly provided by Drs. S. Waddell, M. Heisenberg, and R. Davis, respectively. The X and second chromosomes of the inversion line In(3LR)234 were replaced with those of Canton-S. f02676 was backcrossed with w1118 for at least five generations. Flies were reared on standard cornmeal/agar medium at 25°C and ∼50% relative humidity on a 12 h light/dark cycle. The 4- to 7-d-old flies of mixed genders were used for behavioral tests. In appetitive conditioning, flies were starved for 22 h in Drosophila vials containing water-soaked Kimwipes before training (Kim et al., 2007).

Immunohistochemistry and molecular analyses.

Immunostaining was performed as described previously using mouse anti-dDA1 antibody (1:200 for sections; 1:1000 for whole mounts) and Alexa 555-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:1000; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) (Han et al., 1996; Kim et al., 2003). Images were taken by a DMR epifluorescent (Leica, Heidelberg, Germany) or a FluoView confocal (Olympus, Melville, NY) microscope. RNA preparation and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR were performed using Qiagen (Chatsworth, CA) kits according to the manufacturer's instruction.

Behavioral tests.

The protocol described by Beck et al. (2000) was adopted for aversive conditioning with minor modifications. Appetitive conditioning was performed as described previously (Kim et al., 2007). Briefly, 50–60 flies were exposed to a first odor (CS+) in the presence of pulses of 90 V electric shock or 2 m sucrose for 1 min, followed by 30 s air. After exposure to a second odor (CS−) without shock or sucrose for 1 min, flies were tested in a T-maze with two odors presented for 2 min. In sucrose-mediated conditioning, flies received another cycle of training with a 30 s intertraining interval. A second set of flies was simultaneously trained with the odors presented in a reversed order to counterbalance any possible odor bias in conditioning. The test was performed immediately after or at 1 h after training. The performance index (PI) was calculated by subtracting the percentage of flies that chose CS+ (incorrect choice) from the percentage of flies that chose CS− (correct choice). An average PI of two sets of flies conditioned with counterbalanced odors was used as one data point. Odorants used for conditioning were 1% 3-octanol (OCT), 0.5% benzaldehyde (BA), 2% ethyl acetate (EA), and 2% isoamyl acetate (IAA). Odorants were diluted in mineral oil and sucrose in deionized water. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

For olfactory acuity tests, flies were placed in a T-maze, with one of the arms carrying air and the other carrying an odor, into which flies dispersed from a central choice point, and allowed to choose air versus the odor for 2 min. The tests were performed with the concentrations of odorants used for conditioning and with the five-times lower concentrations. Electric shock avoidance was tested in a T-maze with two tubes lined with copper grids, in one of which flies received pulses of 90 or 30 V electric shock. Sugar preference was also tested in a T-maze with both tubes covered with filter papers, one of which had 2 or 0.2 m sucrose. Avoidance and preference scores were calculated similar to PI.

All data are reported as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using Minitab 14 (Minitab, State College, PA). ANOVA with post hoc Tukey–Kramer or Student's t test was used for normally distributed data. If data were not normally distributed, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used.

Results

Identification of dDA1 mutants

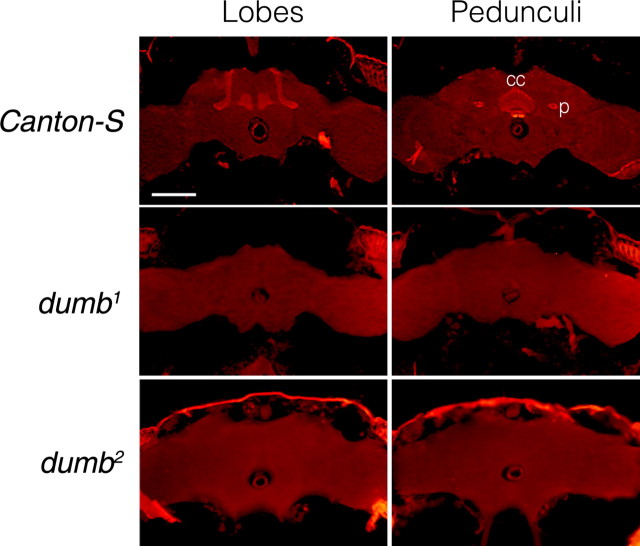

To identify dDA1 mutants, we surveyed multiple fly lines with lesions that are known to map at the chromosomal location 88A where the dDA1 gene resides. Two lines showed abnormal dDA1 immunoreactivities (IRs) in the brain. One of them is the inversion line In(3LR)234, which has the break points at 67D and 88A-88B (Craymer, 1984). The other is f02676 containing the transposable element piggyBac inserted at the first intron in the dDA1 locus (Thibault et al., 2004). Previously, we have shown that dDA1 is highly enriched in the MB lobes, the central complex, a few scattered cells in the brain, and the Apterous-positive cells in the thoracico-abdominal ganglion (Kim et al., 2003; Park et al., 2004). Both In(3LR)234 and f02676 have negligible dDA1 IRs in the MB and the central complex (Fig. 1) but intact IRs in the scattered and Apterous-positive cells (data not shown). Consistently, full-length dDA1 transcripts were detected in both lines by RT-PCR (data not shown). Thus, In(3LR)234 and f02676 appear to have lesions in the regulatory sequence for tissue-specific dDA1 expression, representing hypomorphic dDA1 alleles, and are designated as dumb1 [D1(uno) in mushroom bodies] and dumb2, respectively.

Figure 1.

dDA1 IR in the adult head sections of Canton-S, dumb1, and dumb2 flies. The frontal sections at the levels of the MB lobes (top) and pedunculi along with the central complex (bottom) are shown. dDA1 IR is visualized by red florescence. Canton-S has prominent dDA1 IR in the MB lobes and pedunculi as well as the central complex; however, no dDA1 IR is visible in those structures of dumb1 and dumb2. p, Pedunculus; cc, central complex. All images are at the same magnification. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Impaired learning of dumb mutants in aversive conditioning

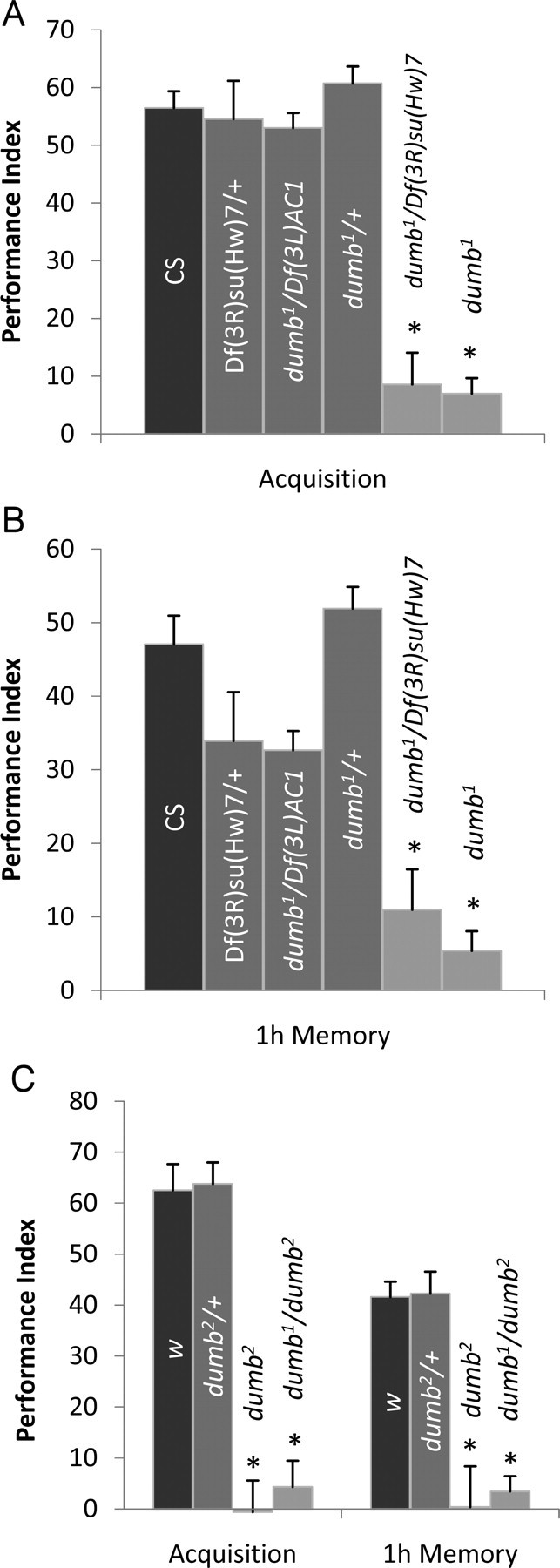

The observations that dDA1 is concentrated in the MB neuropil and can activate the cAMP pathway (Sugamori et al., 1995; Kim et al., 2003) prompted us to investigate the role of dDA1 in olfactory conditioning. When subjected to aversive conditioning using odorants BA and OCT as conditioned stimuli and electric shock as a US, dumb1 homozygous mutants showed severely impaired performance immediately after training (Fig. 2A). Performance of dumb1 did not decline at 1 h after training, suggesting that dumb1 is defective in learning rather than memory. dumb1 has two break points caused by inversion. Thus, to investigate the lesion accountable for poor performance of dumb1, we used two deficiency lines, Df(3L)AC1 and Df(3R)su(Hw)7, having deletion between chromosomes 67A2 and 67D13 and chromosomes 88A9 and 88B2, respectively, which include each break point (Pauli et al., 1995; Deak et al., 1997). Similar to dumb1, dumb1/Df(3R)su(Hw)7 trans-heterozygous mutants exhibited poor performance immediately or 1 h after training (Fig. 2A). In contrast, performance of dumb1/Df(3L)AC1 was comparable to that of Canton-S and dumb1/+ or Df(3R)su(Hw)7/+ heterozygous flies immediately after training. These data indicate that the lesion in chromosome 88A is responsible for poor learning of dumb1 mutants. The flies heterozygous for both deficiency chromosomes had slightly lower performance scores compared with those of Canton-S and dumb1/+ at 1 h after training (Fig. 2A). This could be attributable to putative memory genes in the deleted chromosomes.

Figure 2.

The learning phenotype of dumb mutants in aversive olfactory conditioning. A, B, Flies were trained with BA and OCT as CS and tested immediately after (acquisition) or 1 h after training (1 h memory). A, dumb1 homozygous and dumb1/Df(3R)su(Hw)7 trans-heterozygous mutants exhibited severely impaired learning, whereas dumb1/+, Df(3R)su(Hw)7/+, and dumb1/Df(3L)AC1, which have one copy of the dDA1 gene, showed performance similar to that of Canton-S (AVOVA; F(5,35) = 35.9; p < 0.0001; n = 6 for all groups; asterisks indicate significant difference by post hoc Tukey–Kramer tests). B, At 1 h after training, dumb1, dumb1/Df(3R)su(Hw)7, Df(3R)su(Hw)7/+, and dumb1/Df(3L)AC1 showed defective performance compared with Canton-S and dumb1/+ (ANOVA; F(5,35) = 26.04; p < 0.0001; n = 6; asterisks indicate significant difference compared with Canton-S by post hoc Student's t test). C, dumb2 homozygous and dumb1/dumb2 transheterozygous mutants showed no trace of learning and 1 h memory, whereas learning or 1 h memory performance of dumb2 heterozygous flies (dumb2/+) was similar to that of the genetic control line w1118 (w) (acquisition ANOVA: F(3,23) = 55.3, p < 0.0001; 1 h memory ANOVA: F(3,23) = 21.6, p < 0.0001; n = 6; asterisks indicate significant difference by Tukey–Kramer tests). Error bars indicate SEM.

We next asked whether the dumb1 phenotype is linked to the lesion in dDA1 by examining the independent dumb allele dumb2 and dumb1/dumb2 trans-heterozygous mutants in aversive conditioning. Like dumb1, both genotypes had negligible performance scores immediately after or 1 h after training (Fig. 2B), supporting the potential role of dDA1 in punishment-mediated olfactory learning. dumb1 and dumb2 heterozygous flies exhibited normal performance (Fig. 2A,B); thus, a single copy of dDA1 may be sufficient for mediating this process.

To test whether dumb mutants could learn better with different conditioned stimuli, we used other odorants in electric shock-mediated olfactory conditioning. When trained with EA and IAA as conditioned stimuli, dumb1 mutants also displayed severely impaired learning (PI of dumb1, 4.2 ± 1.3; PI of CS, 59.3 ± 2.4; n = 6; two-tailed Student's t test, p < 0.0001). This suggests that dDA1 is involved in aversive learning induced by diverse odor inputs. The impaired performance of dumb mutants is not attributable to anomalous sensory modalities because all dumb alleles and the control Canton-S and w1118 flies showed comparable avoidance of the CS odors and electric shock presented at two different concentrations or intensities, respectively (Tables 1–3). Thus, poor learning of dumb mutants is likely attributable to their inability to associate CS+ with US.

Table 1.

Sensory modalities including olfactory acuity and shock reactivity [n = 6 for all groups: Df(3R), Df(3R)su(Hw)7;Df(3L), Df(3L)AC1]

| CS | Df(3R)/+ | dumb1/Df(3L) | dumb1/+ | dumb1/Df(3R) | dumb1 | p values | w | dumb2/+ | dumb2 | dumb1/dumb2 | p values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odor | |||||||||||||

| avoidance | 1% OCT | 56.5 ± 4.0 | 52.6 ± 2.5 | 52.6 ± 6.6 | 63.1 ± 4.7 | 56.3 ± 1.8 | 47.8 ± 2.9 | 0.188 | 52.4 ± 4.4 | 49.4 ± 1.4 | 49.4 ± 4.0 | 52.8 ± 4.3 | 0.869 |

| 0.2% OCT | 16.1 ± 5.3 | 18.7 ± 4.6 | 17.8 ± 4.6 | 13.3 ± 5.0 | 13.6 ± 4.6 | 5.1 ± 5.8 | 0.437 | 17.2 ± 4.3 | 15.8 ± 1.5 | 17.9 ± 2.2 | 17.1 ± 2.1 | 0.959 | |

| 0.5% BA | 70.9 ± 4.3 | 76.0 ± 2.2 | 64.5 ± 3.1 | 76.9 ± 3.9 | 65.2 ± 3.7 | 65.6 ± 2.0 | 0.032 | 63.0 ± 3.0 | 65.5 ± 1.4 | 62.1 ± 3.3 | 67.8 ± 4.6 | 0.604 | |

| 0.1% BA | 10.8 ± 3.0 | 11.2 ± 2.9 | 9.7 ± 3.4 | 14.6 ± 1.5 | 12.7 ± 3.6 | 7.2 ± 3.0 | 0.608 | 16.8 ± 3.8 | 15.3 ± 1.8 | 17.0 ± 1.3 | 17.4 ± 3.9 | 0.962 | |

| Shock | |||||||||||||

| avoidance | 90 V | 69.9 ± 3.5 | 66.1 ± 4.6 | 68.8 ± 6.7 | 63.6 ± 4.4 | 66.7 ± 4.5 | 69.2 ± 2.5 | 0.927 | 57.8 ± 4.4 | 62.4 ± 4.4 | 57.5 ± 3.9 | 54.7 ± 4.0 | 0.635 |

| 30 V | 39.3 ± 3.3 | 28.5 ± 2.9 | 26.6 ± 3.2 | 29.7 ± 6.3 | 31.5 ± 3.4 | 27.0 ± 2.5 | 0.212 | 25.8 ± 4.0 | 27.1 ± 8.1 | 27.5 ± 4.3 | 24.8 ± 4.2 | 0.984 |

Table 2.

Sensory modalities including olfactory acuity and shock reactivity (n = 6 for all groups)

| 247/+;dumb1 | 247/+;dumb2 | 247/+;dumb1/dumb2 | 247/+;dumb1/+ | p values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odor avoidance | 1% OCT | 50.9 ± 4.1 | 53.0 ± 3.6 | 53.9 ± 3.3 | 52.0 ± 6.0 | 0.965 |

| 0.5% BA | 62.1 ± 3.2 | 56.0 ± 4.6 | 59.3 ± 2.7 | 57.6 ± 2.2 | 0.609 | |

| Shock avoidance | 90 V | 60.5 ± 2.8 | 57.3 ± 2.7 | 59.5 ± 3.3 | 56.9 ± 3.6 | 0.820 |

| 30 V | 31.3 ± 3.9 | 28.8 ± 3.5 | 26.5 ± 3.4 | 30.3 ± 3.6 | 0.798 |

Table 3.

Sensory modalities including olfactory acuity and taste perception (n = 6 for all groups)

| CS | dumb1 | dumb2 | 247/+;dumb2 | p values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugar preference | 2 m sucrose | 68.2 ± 2.9 | 70.0 ± 3.5 | 68.6 ± 2.2 | 70.4 ± 2.9 | 0.942 |

| 0.2 m sucrose | 38.1 ± 3.1 | 37.0 ± 2.9 | 39.9 ± 3.9 | 36.4 ± 3.0 | 0.881 | |

| Odor avoidance | 2% IAA | 64.4 ± 2.7 | 62.4 ± 2.8 | 60.3 ± 3.1 | 61.8 ± 3.1 | 0.798 |

| 2% EA | 64.4 ± 2.3 | 61.6 ± 3.0 | 64.3 ± 3.4 | 61.9 ± 2.9 | 0.841 |

Aversive learning requires dDA1 in the MB

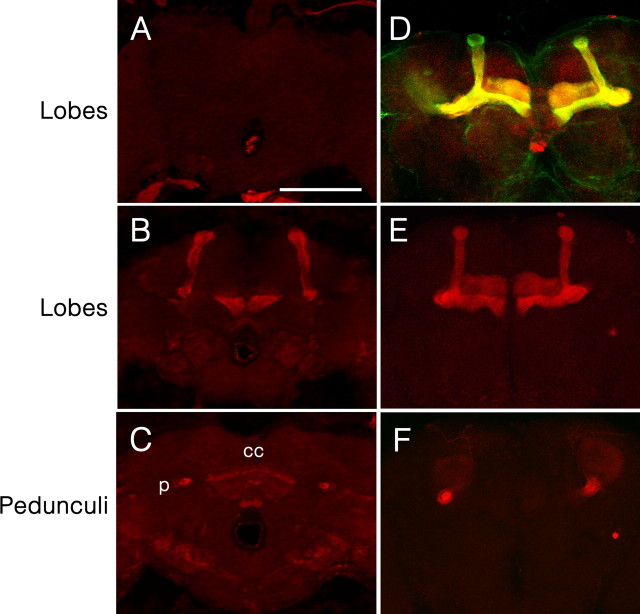

Synaptic output of dopamine neurons was previously shown to be required during training for aversive learning (Schwaerzel et al., 2003), implicating the similar requirement of dDA1 at the time of learning. To test this, we used the pan-neuronal driver Elav-GAL4 and GAL80ts, which allows the temporal control of GAL4 activities (McGuire et al., 2003). GAL80 binds to GAL4 to sequester it from activating upstream activating sequence (UAS). The temperature-sensitive GAL80ts can no longer bind to GAL4 at 30°C, allowing it to act on UAS to induce downstream gene expression. The piggyBac inserted at the first intron of the dDA1 gene in dumb2 has UAS (Thibault et al., 2004). Although the piggyBac insertion itself interferes with endogenous dDA1 expression in dumb2, UAS in piggyBac, after binding to GAL4, may induce dDA1 transcription from the second exon containing the 5′ untranslated sequence and the start codon. Thus, we crossed dumb2 with dumb1 carrying Elav-GAL4 and GAL80ts to generate Elav-GAL4,GAL80ts/+;dumb1/dumb2 flies. The Elav-GAL4,GAL80ts/+;dumb1/dumb2 kept at room temperature did not have any detectable dDA1 induction (Fig. 3A); however, when the flies were reared at 30°C for 3 d, conspicuous dDA1 IR was visible in the MB lobes and pedunculi, the central complex, and other brain areas including antennal lobes (Fig. 3B,C and data not shown). Whereas Elav-GAL4 is expressed in all neurons (Ito et al., 1998), membrane-bound GFP reporters driven by Elav-GAL4 are enriched in certain brain areas including the aforementioned structures (data not shown). Therefore, the temporal manipulation of GAL80ts and Elav-GAL4 activities was effective in restricting dDA1 expression at the adult stage in dumb mutants.

Figure 3.

Restored dDA1 expression in dumb transgenic mutants. A–C, dumb1/dumb2 trans-heterozygous mutants carrying Elav-GAL4 and GAL80ts reared at room temperature (uninduced) had no detectable dDA1 expression (A); however, when they were incubated at 30°C for 3 d (induced), dDA1 IRs were visible in the MB lobes (B) and pedunculi, the central complex, and other brain structures (C). D, GFP driven by MB247-GAL4 in the wild-type genetic background was visible in most, if not all, dDA1-positive MB neurons. E, F, dumb1/dumb2 carrying MB247-GAL4 had conspicuous dDA1 expression in the MB lobes (E) and pedunculi (F) but not in the central complex (F). p, Pedunculus; cc, central complex. All images are at the same magnification. Scale bar, 100 μm.

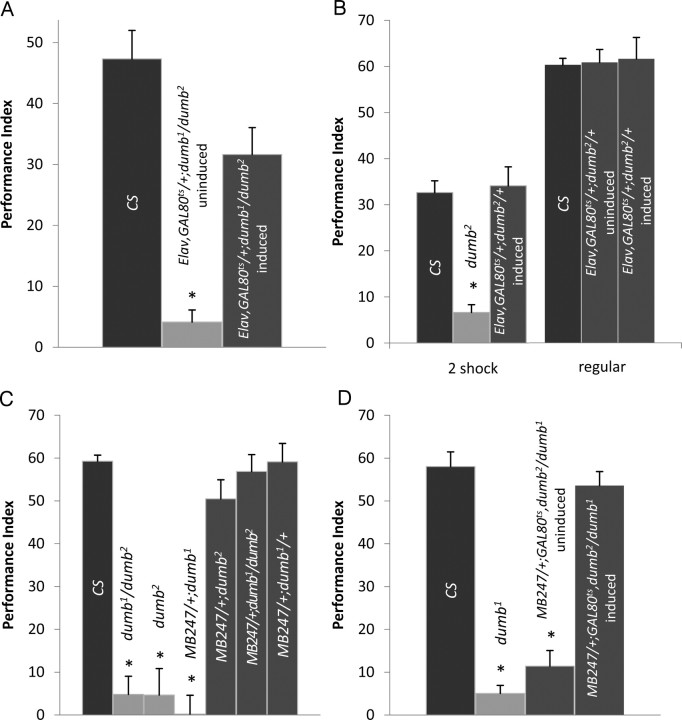

When Elav-GAL4,GAL80ts/+;dumb1/dumb2 flies reared at room temperature were subjected to electric shock-mediated conditioning, they showed poor learning; however, their performance was dramatically improved after temperature shift to 30°C (Fig. 4A). The performance score of Elav-GAL4,GAL80ts/+;dumb1/dumb2 with the restored dDA1 expression was slightly lower than that of Canton-S; nonetheless, it was not significantly different from that of Canton-S treated with the same temperature shift but was different from that of uninduced Elav-GAL4,GAL80ts/+;dumb1/dumb2 (p = 0.0009). Therefore, dDA1 is required in the adult neurons, presumably at the time of training, for aversive memory formation. Notably, the same manipulation in the dumb2 heterozygous background (Elav-GAL4,GAL80ts/+;dumb2/+) did not alter the performance scores after brief training (2 pulses of electric shock) or regular training (12 pulses of electric shock) (Fig. 4B). This indicates that the ectopically expressed dDA1 has a negligible effect on normal learning of the heterozygous flies and thus unlikely contribute to the reinstated performance of dumb1/dumb2 mutants.

Figure 4.

Rescue of the dumb mutant's phenotype in aversive learning. A, The restricted dDA1 expression in the adult nervous system rescued the learning phenotype of dumb mutants. dumb1/dumb2 carrying Elav-GAL4 and GAL80ts reared at room temperature (Elav,GAL80ts/+;dumb1/dumb2 uninduced) showed poor performance immediately after training; however, performance of the same genotype reared at 30°C for 3 d (Elav,GAL80ts/+;dumb1/dumb2 induced) was not significantly different from that of Canton-S (Kruskal–Wallis test, p = 0.0009; n = 6; the asterisk indicates significant difference by Mann–Whitney tests). B, When subjected to brief (submaximal) training with two pulses of electric shock (2 shocks), dumb2 heterozygous flies carrying Elav-GAL4 and GAL80ts that were reared at 30°C for 3 d to induce ectopic dDA1 expression (Elav,GAL80ts/+;dumb1/dumb2 induced) had the learning score comparable with that of Canton-S, whereas dumb2 homozygous mutants showed impaired learning (ANOVA; F(2,17) = 27.2; p < 0.0001; n = 6; the asterisk indicates significant difference by Tukey–Kramer tests). Likewise, the dumb2 heterozygous flies with ectopic dDA1 expression (Elav,GAL80ts/+;dumb1/dumb2 induced) had performance comparable with that of Canton-S and the same genotype without heat treatment (Elav,GAL80ts/+;dumb1/dumb2 uninduced) when subjected to regular training with 12 pulses of electric shock (regular) (ANOVA; F(2,17) = 0.04; p = 0.96; n = 6). C, The dumb transgenic mutants expressing dDA1 in the MB lobes (MB247/+;dumb2 and MB247/+;dumb1/dumb2) had the learning scores similar to those of Canton-S and MB247/+;dumb1/+, whereas all three lines with deficient dDA1 expression (dumb2, dumb1/dumb2, and MB247/+;dumb1) had significantly low learning scores (ANOVA; F(6,41) = 43.6; p < 0.0001; n = 6; asterisks indicate significant difference by Tukey–Kramer tests). D, The temporally induced dDA1 expression only in the adult MB rescued the learning phenotype of dumb mutants. dumb1/dumb2 carrying MB247-GAL4 and GAL80ts that were reared at 30°C for 3 d (MB247/+;GAL80ts,dumb2/dumb1 induced) had the learning score comparable with that of Canton-S, whereas the same genotype reared at room temperature (MB247/+;GAL80ts,dumb2/dumb1 uninduced) and dumb1 homozygous mutants had significantly low learning scores (ANOVA; F(3,23) = 77.6; p < 0.0001; n = 6; asterisks indicate significant difference by Tukey–Kramer tests). Error bars indicate SEM.

We next addressed whether the learning phenotype of dumb mutants is attributable to deficient dDA1 function in the MB rather than in the central complex or other neurons. MB247-GAL4 contains 247 bp of dMEF2 regulatory sequence that allows GAL4 expression rather specifically in a subset of the MB neurons projecting to the α/β lobes and the gamma lobes, but not the α′/β′ lobes (Schulz et al., 1996; Schwaerzel et al., 2002; Krashes et al., 2007). When MB247-GAL4/UAS-GFP in the wild-type background was stained with the dDA1 antibody, the GFP-labeled (thus MB247-GAL4-expressing) MB neurons were positive for dDA1 IRs although the relative intensities of GFP and dDA1 signals varied in the different MB lobes (Fig. 3D). Thus, MB247-GAL4 was used to reinstate dDA1 expression in the MB of dumb mutants. After staining with anti-dDA1 antibody, dDA1 expression was apparent in the MB lobes (Fig. 3E) and pedunculi (Fig. 3F) but not in other neural structures (Fig. 3E,F and data not shown) of MB247-GAL4/+;dumb1/dumb2. When subjected to electric shock-mediated conditioning, MB247-GAL4/+;dumb1/dumb2 or MB247-GAL4/+;dumb2/dumb2 had the learning scores comparable to those of Canton-S (Fig. 4C). Moreover, fully reinstated performance was observed in MB247-GAL4/+;GAL80ts,dumb2/dumb1 reared at 30°C for 3 d before training but not in MB247-GAL4/+;GAL80ts,dumb2/dumb1 reared at room temperature (Fig. 4D). Therefore, dDA1 expressed only in the subset of the adult MB neurons is necessary and sufficient to rescue the dumb mutant's impaired learning, indicating the indispensable role of the MB dDA1 in aversive memory formation.

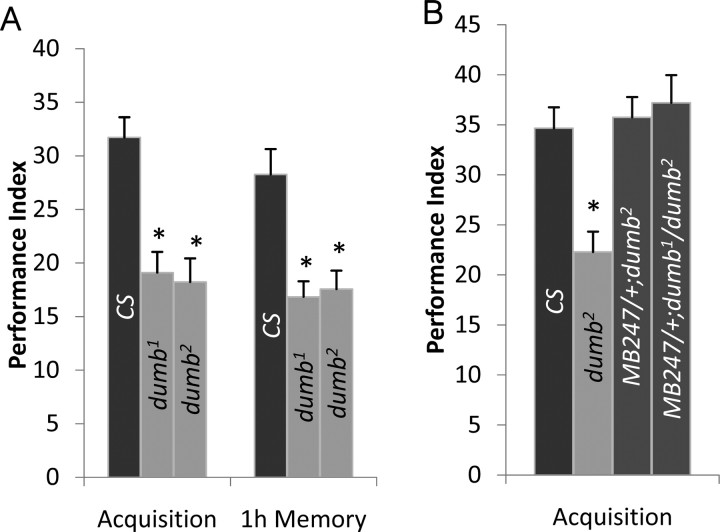

Appetitive learning requires dDA1 in the MB

Dopamine is crucial in appetitive learning in mammals; however, the previous study (Schwaerzel et al., 2003) of TH-GAL4/UAS-Shits flies suggests that this is not the case in Drosophila. To investigate this further, we tested dumb mutants in sugar-mediated olfactory conditioning. To our surprise, both dumb1 and dumb2 mutants exhibited poor performance immediately after training (Fig. 5A). Although dumb mutants' performance in appetitive learning was not as severely impaired as in aversive conditioning, it was significantly different from that of Canton-S (Fig. 5A) or w1118 (data not shown). As in electric shock-mediated conditioning, dumb mutants' performance did not decline at 1 h after training, indicating a crucial role of dDA1 in acquisition, as opposed to short-term memory, of appetitive conditioning. Moreover, dumb2 homozygous or dumb1/dumb2 trans-heterozygous mutants carrying MB247-GAL4 displayed fully reinstated learning in sugar-mediated conditioning (Fig. 5B). These data indicate that dDA1 is required in the same subset of the MB neurons for aversive and appetitive learning.

Figure 5.

Impaired learning of dumb mutants in appetitive conditioning and rescue by reinstated dDA1 expression in the MB. A, Both dumb1 and dumb2 mutants were moderately impaired in acquisition (ANOVA; F(2,17) = 14.2; p < 0.0001; n = 6) and 1 h memory (ANOVA; F(2,17) = 11.5; p < 0.005; n = 6) of sugar-mediated olfactory conditioning. B, The dDA1 expression in the MB driven by MB247-GAL4 was sufficient to rescue the learning phenotype of dumb2 homozygous (MB247/+;dumb2) and dumb1/dumb2 transheterozygous (MB247/+;dumb1/dumb2) mutants (ANOVA; F(3,50) = 10.2; p < 0.0001; n = 6 for MB247/+;dumb1/dumb2; n = 15 for other groups). Asterisks denote significant difference by Tukey–Kramer tests. Error bars indicate SEM.

Discussion

dDA1 in aversive learning

Previous research on olfactory conditioning in Drosophila has primarily focused on the intracellular components, many of which are involved in learning and/or memory processes in the MB (McGuire et al., 2005). Although those studies have revealed important insights, the receptors that initiate signaling cascades into motion in the MB are unknown. The findings presented here provide the first demonstration of a MB receptor essential for aversive learning. The role of dDA1 in this behavioral plasticity is physiological, rather than developmental. This is consistent with the observations that synaptic output of dopaminergic neurons is necessary during training (Schwaerzel et al., 2003), and the learning phenotype of rut mutants is rescued by the restricted expression of rut-AC, a potential dDA1 effector, in the adult MB (McGuire et al., 2003; Mao et al., 2004). Moreover, the dopaminergic processes projecting to the MB gamma lobe strongly respond to electric shock (US) and show altered activities after CS+ exposure (Riemensperger et al., 2005). Together, these strongly implicate dDA1 as a receptor conveying aversive US information in the MB lobes for memory formation.

Two additional neuromodulator systems are previously implicated in aversive olfactory conditioning in Drosophila. One neuromodulator system is the glutamate NMDA receptor composed of dNR1 and dNR2 subunits. Flies with decreased dNR1 expression show diminished performance in aversive conditioning (Xia et al., 2005). Although dNR1 in the MB is crucial for anesthesia-resistant and midterm memories, dNR1-dependent learning occurs outside of the MB (Lin, 2005). Another putative modulator involved in olfactory learning is Amn, which has sequence homology with mammalian neuropeptide PACAP. Although amn mutants are mostly defective in midterm memory, they are mildly impaired in learning when BA is used as CS+ and learning of BA depends on synaptic output of Amn-expressing DPM neurons projecting to the MB lobes (Keene et al., 2004). Thus, it has been suggested that putative amn-encoded neuropeptides, by binding to their receptor(s) in the MB neuropil, may mediate memory formation; however, the predicted Amn neuropeptides or their receptors remain unidentified. Therefore, dDA1 represents the only MB receptor identified to date that is essential for aversive learning. Notably, dumb mutants, similar to MB-less flies, show negligible learning (de Belle and Heisenberg, 1994). This indicates that the MB neurons absolutely require dDA1 for aversive memory formation.

dDA1 in appetitive learning

The data presented here demonstrate the crucial role of dDA1 in sugar-mediated olfactory learning as well. Interestingly, dumb mutants have diminished, yet significant, performance scores, implicating an additional receptor(s) for this type of learning. Indeed, tβh mutants lacking octopamine show severe impairment in appetitive conditioning, which is rescued by feeding octopamine before, but not after, training (Schwaerzel et al., 2003). Thus, octopamine represents another neuromodulator crucial for appetitive learning. Because the MB is a primary neural substrate for appetitive conditioning, reward memory formation is likely mediated by dDA1 and an octopamine receptor(s) in the MB.

The previous study of TH-GAL4/UAS-Shits flies, in which endocytosis of the dopamine neurons expressing TH-GAL4 can be temporally controlled by dominant-negative dynamin Shits, suggests that dopamine is not involved in appetitive conditioning (Schwaerzel et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2007). This is contrary to the learning phenotype of D1 dopamine receptor mutants dumb. Nonetheless, the discrepancy may be reconciled by several reasonable possibilities. First, TH-GAL4 used in the previous study to drive Shits may not be expressed, or expressed at low levels, in a subset of the dopamine neurons critical for appetitive learning. Second, dopamine neuronal output conveying sugar information may not be completely inhibited by Shits. Third, dopamine crucial for appetitive learning may be secreted by a dynamin-independent pathway. These possibilities may be tested by investigating pale mutants that are unable to synthesize dopamine; however, such flies die during development because of an essential role of dopamine in cuticle formation (Budnik and White, 1987). Future studies on conditional pale mutants should help resolve this issue.

Punishment and reward signals activated by dDA1 in the MB

We have shown here that dDA1 expression driven by MB247-GAL4 fully rescues the learning phenotypes of dumb mutants in electric shock- as well as sugar-mediated conditioning. This indicates that appetitive and aversive memory formations are mediated by dDA1 in the same subset of the MB neurons (∼30% of all MB neurons). This poses an intriguing question as to how those MB neurons distinguish punishment versus reward information delivered by dDA1 to generate avoidance versus preference behavioral output. The key to answering this question may be intracellular effectors in the MB neuropil. rut-AC is crucial in the MB247-GAL4-expressing MB neurons for both aversive and appetitive learning (Schwaerzel et al., 2003). Notably, rut mutants retain some learning capacities in electric shock- and sugar-mediated conditioning, whereas MB-less flies or the flies with inhibited MB synaptic output exhibit no trace of learning in both assays (de Belle and Heisenberg, 1994; Krashes et al., 2007). This implicates additional cellular components crucial for aversive and appetitive memory formation. Because dumb mutants are rather completely impaired in aversive learning, dDA1 may activate rut-AC and other cellular components in the MB to process punishment information.

G-protein-coupled receptors including dopamine receptors can recruit multiple effector systems through heteromeric G-proteins or through cross-interactions of diverse signaling components (Lidow et al., 2001; Pierce et al., 2002). Thus, for aversive learning, dDA1 activated by electric shock US input may recruit the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascade in addition to the cAMP pathway. The activated protein kinase A and MAP kinases may act on ion channels or cell adhesion molecules such as integrin and fasII to modify MB synaptic output, leading to avoidance behavior (Yoshihara et al., 2000; Berke and Wu, 2002; Koh et al., 2002; Selcher et al., 2002). Consistently, the flies defective in 14-3-3 and S6KII, which are involved in the MAP kinase cascade, and α-integrin and fasII mutants are poor learners in electric shock-mediated conditioning (Skoulakis and Davis, 1996; Grotewiel et al., 1998; Cheng et al., 2001; Putz et al., 2004).

For reward-mediated learning, reward US input may impinge on at least two receptors, dDA1 and an octopamine receptor, in the MB. Their simultaneous activities may recruit multiple effectors that possibly include rut-AC, MAP kinases, protein kinase C, and CaM kinase II. The biochemical changes collectively activated by these effectors may alter MB synaptic output to generate preference behavior. Interestingly, OAMB (octopamine receptor) activates the increases in intracellular calcium as well as cAMP (Han et al., 1998) and is a good candidate that can turn on the aforementioned effectors for processing reward information in the MB. The punishment and reward effectors may be at work in separate areas of the same MB neuropil or in different MB neurons or neuropils, which are differentially innervated by dopaminergic axons conveying electric shock input or by dopaminergic and octopaminergic axons conveying sugar input. At present, there is limited information on intracellular components involved in appetitive learning. Future studies in this venue will help attest this model. Together, concurrent CS+ and US received during training may activate dDA1 (for punishment US) or dDA1 and an octopamine receptor (for reward US) to induce distinctive biochemical changes, leading to avoidance or preference behavior, respectively.

D1 dopamine receptor in pavlovian conditioning

Multiple lines of evidence indicate that dopamine in the amygdala, the nucleus accumbens, and the medial prefrontal cortex in mammals is crucial for acquisition, expression, and/or extinction in aversive pavlovian conditioning (for review, see Pezze and Feldon, 2004). However, the receptors mediating the functions of dopamine are unclear. Studies using D1/D5 dopamine receptor antagonist R(+)-7-chloro-8-hydroxy-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-3-benzazepine hydrochloride (SCH23390) in rats suggest the significant roles of the D1-type receptor in the amygdala and the nucleus accumbens during acquisition in fear conditioning and conditioned taste aversion (CTA), respectively (Guarraci et al., 1999; Fenu et al., 2001). However, the mice lacking D1 or D5 receptor show normal acquisition in fear conditioning (El-Ghundi et al., 2001; Holmes et al., 2001). Likewise, D1-deficient mice show normal learning of CTA to salt (CS) paired with LiCl (US), although they do not develop CTA to sucrose (Cannon et al., 2005). The discrepant findings of the pharmacological and genetic studies may be attributable to either other receptor types affected by SCH23390 or compensatory adaptations in D1 or D5 knock-out mice. The studies reported here support the latter and clarify the indispensable role of D1 receptor in aversive pavlovian conditioning. Additionally, pharmacological studies reveal the significant role of D1-type receptors in appetitive pavlovian conditioning in mammals (Schroeder and Packard, 2000; Baker et al., 2003; Eyny and Horvitz, 2003; Dalley et al., 2005) and possibly in Aplysia (Reyes et al., 2005), although no information is available on D1 or D5 knock-out mice in this type of behavioral plasticity. Therefore, the studies described here elucidate, for the first time, the critical role of D1 receptor in appetitive pavlovian conditioning.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Science Foundation to K.-A.H. We greatly appreciate Drs. Scott Waddell, Martin Heisenberg, and Ronald Davis and the Bloomington stock center and Harvard Exelixis stock collection for providing fly lines.

References

- Baker RM, Shah MJ, Sclafani A, Bodnar RJ. Dopamine D1 and D2 antagonists reduce the acquisition and expression of flavor-preferences conditioned by fructose in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75:55–65. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CDO, Schroeder B, Davis RL. Learning performance of normal and mutant Drosophila after repeated conditioning trials with discrete stimuli. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2944–2953. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02944.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke B, Wu CF. Regional calcium regulation within cultured Drosophila neurons: effects of altered cAMP metabolism by the learning mutations dunce and rutabaga. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4437–4447. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04437.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budnik V, White K. Genetic dissection of dopamine and serotonin synthesis in the nervous system of Drosophila melanogaster. J Neurogenet. 1987;4:309–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon CM, Scannell CA, Palmiter RD. Mice lacking dopamine D1 receptors express normal lithium chloride-induced conditioned taste aversion for salt but not sucrose. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2600–2604. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Endo K, Wu K, Rodan AR, Heberlein U, Davis RL. Drosophila fasciclinII is required for the formation of odor memories and for normal sensitivity to alcohol. Cell. 2001;105:757–768. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly JB, Roberts IJH, Armstrong JD, Kaiser K, Forte M, Tully T, O'Kane CJ. Associative learning disrupted by impaired Gs signaling in Drosophila mushroom bodies. Science. 1996;274:2104–2107. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craymer L. New mutants report. Dros Inf Serv. 1984;60:234–236. [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Laane K, Theobald DE, Armstrong HC, Corlett PR, Chudasama Y, Robbins TW. Time-limited modulation of appetitive Pavlovian memory by D1 and NMDA receptors in the nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6189–6194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502080102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RL. Olfactory memory formation in Drosophila: from molecular to systems neuroscience. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:275–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Belle JS, Heisenberg M. Associative odor learning in Drosophila abolished by chemical ablation of mushroom bodies. Science. 1994;263:692–695. doi: 10.1126/science.8303280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deak P, Omar MM, Saunders RDC, Pal M, Komonyi O, Szidonya J, Maroy P, Zhang Y, Ashburner M, Benos P, Savakis C, Siden-Kiamos I, Louis C, Bolshakov VN, Kafatos FC, Madueno E, Modolell J, Glover DM. P-element insertion alleles of essential genes on the third chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster: correlation of physical and cytogenetic maps in chromosomal region 86E–87F. Genetics. 1997;147:1697–1722. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.4.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubnau J, Grady L, Kitamoto T, Tully T. Disruption of neurotransmission in Drosophila mushroom body blocks retrieval but not acquisition of memory. Nature. 2001;411:476–480. doi: 10.1038/35078077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Ghundi M, O'Dowd BF, George SR. Prolonged fear responses in mice lacking dopamine D1 receptor. Brain Res. 2001;892:86–93. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyny YS, Horvitz JC. Opposing roles of D1 and D2 receptors in appetitive conditioning. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1584–1587. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01584.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenu S, Bassareo V, Di Chiara G. A role for dopamine D1 receptors of the nucleus accumbens shell in conditioned taste aversion learning. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6897–6904. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06897.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotewiel MS, Beck CDO, Wu KH, Zhu X-R, Davis RL. Integrin-mediated short-term memory in Drosophila. Nature. 1998;391:455–460. doi: 10.1038/35079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarraci FA, Frohardt RJ, Kapp BS. Amygdaloid D1 dopamine receptor involvement in Pavlovian fear conditioning. Brain Res. 1999;827:28–40. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han KA, Millar NS, Grotewiel MS, Davis RL. DAMB, a novel dopamine receptor expressed specifically in Drosophila mushroom bodies. Neuron. 1996;16:1127–1135. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han K-A, Millar NS, Davis RL. A novel octopamine receptor with preferential expression in Drosophila mushroom bodies. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3650–3658. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03650.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A, Hollon TR, Gleason TC, Liu Z, Dreiling J, Sibley DR, Crawley JN. Behavioral characterization of dopamine D5 receptor null mutant mice. Behav Neurosci. 2001;115:1129–1144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isabel G, Pascual A, Preat T. Exclusive consolidated memory phases in Drosophila. Science. 2004;304:1024–1027. doi: 10.1126/science.1094932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Suzuki K, Estes P, Ramaswami M, Yamamoto D, Strausfeld NJ. The organization of extrinsic neurons and their implications in the functional roles of the mushroom bodies in Drosophila melanogaster Meigen. Learn Mem. 1998;5:52–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene AC, Stratmann M, Keller A, Perrat PN, Vosshall LB, Waddell S. Diverse odor-conditioned memories require uniquely timed dorsal paired medial neuron output. Neuron. 2004;44:521–533. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YC, Lee HG, Seong CS, Han KA. Expression of a D1 dopamine receptor dDA1/DmDOP1 in the central nervous system of Drosophila melanogaster. Gene Expr Patterns. 2003;3:237–245. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(02)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YC, Lee HG, Han KA. Classical reward conditioning in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:201–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh YH, Ruiz-Canada C, Gorczyca M, Budnik V. The Ras1-mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway regulates synaptic plasticity through fasciclin II-mediated cell adhesion. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2496–2504. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02496.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krashes MJ, Keene AC, Leung B, Armstrong JD, Waddell S. Sequential use of mushroom body neuron subsets during Drosophila odor memory processing. Neuron. 2007;53:103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidow MS, Roberts A, Zhang L, Koh P-O, Lezcano N, Bergson C. Receptor crosstalk protein, calcyon, regulates affinity state of dopamine D1 receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;427:187–193. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin WY. NMDA receptors are required in memory formation in Drosophila mushroom body. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334:779–786. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Z, Roman G, Zong L, Davis RL. Pharmacogenetic rescue in time and space of the rutabaga memory impairment by using Gene-Switch. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:198–203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306128101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire SE, Le PT, Osborn AJ, Matsumoto K, Davis RL. Spatiotemporal rescue of memory dysfunction in Drosophila. Science. 2003;302:1765–1768. doi: 10.1126/science.1089035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire SE, Deshazer M, Davis RL. Thirty years of olfactory learning and memory research in Drosophila melanogaster. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;76:328–347. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D, Han M, Kim Y-C, Han K-A, Taghert PH. Ap-let neurons–a peptidergic circuit potentially controlling ecdysial behavior in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 2004;269:95–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauli D, Oliver B, Mahowald AP. Identification of regions interacting with ovo(D) mutations: potential new genes involved in germline sex determination or differentiation in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1995;139:713–732. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.2.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezze MA, Feldon J. Mesolimbic dopaminergic pathways in fear conditioning. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;74:301–320. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce KL, Premont RT, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:639–650. doi: 10.1038/nrm908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putz G, Bertolucci F, Raabe T, Zars T, Heisenberg M. The S6KII (rsk) gene of Drosophila melanogaster differentially affects an operant and a classical learning task. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9745–9751. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3211-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes FD, Mozzachiodi R, Baxter DA, Byrne JH. Reinforcement in an in vitro analog of appetitive classical conditioning of feeding behavior in Aplysia: blockade by a dopamine antagonist. Learn Mem. 2005;12:216–220. doi: 10.1101/lm.92905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemensperger T, Voller T, Stock P, Buchner E, Fiala A. Punishment prediction by dopaminergic neurons in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1953–1960. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JP, Packard MG. Role of dopamine receptor subtypes in the acquisition of a testosterone conditioned place preference in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2000;282:17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00839-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroll C, Riemensperger T, Bucher D, Ehmer J, Voller T, Erbguth K, Gerber B, Hendel T, Nagel G, Buchner E, Fiala A. Light-induced activation of distinct modulatory neurons triggers appetitive or aversive learning in Drosophila larvae. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1741–1747. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz RA, Chromey C, Lu MF, Zhao B, Olson EN. Expression of the D-MEF2 transcription in the Drosophila brain suggests a role in neuronal cell differentiation. Oncogene. 1996;12:1827–1831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaerzel M, Heisenberg M, Zars T. Extinction antagonizes olfactory memory at the subcellular level. Neuron. 2002;35:951–960. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00832-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaerzel M, Monastirioti M, Scholz H, Friggi-Grelin F, Birman S, Heisenberg M. Dopamine and octopamine differentiate between aversive and appetitive olfactory memories in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10495–10502. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-33-10495.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selcher JC, Weeber EJ, Varga AW, Sweatt JD, Swank M. Protein kinase signal transduction cascades in mammalian associative conditioning. Neuroscientist. 2002;8:122–131. doi: 10.1177/107385840200800208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoulakis EMC, Davis RL. Olfactory learning deficits in mutants for leonardo, a Drosophila gene encoding a 14-3-3 protein. Neuron. 1996;17:931–944. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugamori KS, Demchyshyn LL, McConkey F, Forte MA, Niznik HB. A primordial dopamine D1-like adenylyl cyclase-linked receptor from Drosophila melanogaster displaying poor affinity for benzazepines. FEBS Lett. 1995;362:131–138. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00224-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibault ST, Singer MA, Miyazaki WY, Milash B, Dompe NA, Singh CM, Buchholz R, Demsky M, Fawcett R, Francis-Lang HL, Ryner L, Cheung LM, Chong A, Erickson C, Fisher WW, Greer K, Hartouni SR, Howie E, Jakkula L, Joo D, et al. A complementary transposon tool kit for Drosophila melanogaster using P and piggyBac. Nat Genet. 2004;36:283–287. doi: 10.1038/ng1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia S, Miyashita T, Fu T-F, Lin W-Y, Wu C-L, Pyzocha L, Lin I-R, Saitoe M, Tully T, Chiang A-S. NMDA receptors mediate olfactory learning and memory in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2005;15:603–615. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara M, Suzuki K, Kidokoro Y. Two independent pathways mediated by cAMP and protein kinase A enhance spontaneous transmitter release at Drosophila neuromuscular junctions. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8315–8322. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-08315.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]