Abstract

The complement (C) system plays an important role in myelin breakdown during Wallerian degeneration (WD). The pathway and mechanism involved are, however, not clear. In a crush injury model of the sciatic nerve, we show that C6, necessary for the assembly of the membrane attack complex (MAC), is essential for rapid WD. At 3 d after injury, pronounced WD occurred in wild-type animals, whereas the axons and myelin of C6-deficient animals appeared intact. Macrophage recruitment and activation was inhibited in C6-deficient rats. However, 7 d after injury, the distal part of the C6-deficient nerves appeared degraded. As a consequence of a delayed WD, more myelin breakdown products were present than in wild-type nerves. Reconstitution of the C6-deficient animals with C6 restored the wild-type phenotype. Treatment with rhC1INH (recombinant human complement 1 inhibitor) blocked deposition of activated C-cleaved products after injury. These experiments demonstrate that the classical pathway of the complement system is activated after acute nerve trauma and that the entire complement cascade, including MAC deposition, is essential for rapid WD and efficient clearance of myelin after acute peripheral nerve trauma.

Keywords: Wallerian degeneration, crush injury, complement, macrophage, neurodegenerative disease, neuropathy

Introduction

Wallerian degeneration (WD) is the sequence of axonal and myelin degradation that results from mechanical or metabolic damage to the nerve. The first abnormalities occur 12 h after injury and become more evident 24–48 h later (Waller, 1850; Ballin and Thomas, 1969). After degeneration of the axon, the myelin sheath collapses and initially remains within the parent Schwann cell cytoplasm. The endoneurial macrophages proliferate, become activated, and initiate myelin phagocytosis (Leonhard et al., 2002). This population is later supplemented by monocytes/macrophages recruited from the bloodstream that participate in myelin phagocytosis and removal (Mueller et al., 2001; Hirata and Kawabuchi, 2002).

Although the histology of WD is well established (Ramón y Cajal, 1991), the molecular basis is not fully understood. We have recently shown that proteins of the complement system are produced in the undamaged peripheral nerve and are activated after injury and disease (de Jonge et al., 2004).

The complement (C) system is part of the innate immune response against pathogens. It is activated via three distinct routes: the classical, the lectin, and the alternative pathways. The classical pathway is activated by the binding of C1q to nonself epitopes, either directly or via antibodies, and it is blocked by the complement regulator complement 1 inhibitor (C1INH) (Harpel and Cooper, 1975). The lectin pathway is triggered by binding of mannose binding lectin to certain carbohydrates on the pathogen surface (Fujita et al., 2004), whereas the alternative pathway starts by spontaneous low-rate hydrolysis of C3, which binds to activated factor B on a surface lacking complement inhibitors, such as factor H. Regardless of the initial recognition pathway, all three routes converge in the cleavage of C3 and subsequently of C5. This results in the formation of chemoattractants, opsonins, and C5b, which serves as an anchor for the assembly of C6, C7, C8, and C9. The complex C5b-9, also known as membrane attack complex (MAC), is inserted into the cell membrane of the pathogens, leading to cell lysis (Nauta et al., 2004).

Previous studies of WD showed that the complement system mediates myelin phagocytosis by macrophages (Bruck and Friede, 1990), whereas depletion of C3 (Dailey et al., 1998) or C5 deficiency (Liu et al., 1999) delay WD and inhibit macrophage recruitment. However, because of their multiple functions, depletion of C3 or C5 could affect different pathways. Whether C-cleaved products alone or the entire complement cascade including the MAC is needed for WD is still being debated (Barnum and Szalai, 2006). The C6-deficient (C6−/−) PVG/c− rat model (Leenaerts et al., 1994; van Dixhoorn et al., 1997; Bhole and Stahl, 2004) offers the opportunity to dissect the role of the terminal complement factors, separating the chemoattractant effect of upstream complement components from the cytolytic effect of the terminal MAC.

We analyzed the role of C6, and thus of MAC, in WD. This is relevant to the understanding of the complement-mediated events in axon loss and subsequent myelin degradation, which are common hallmarks of many neurodegenerative diseases and peripheral neuropathies (Glass, 2004).

Materials and Methods

Animals.

This study was approved by the Academic Medical Center Animal Ethics Committee and complies with the guidelines for the care of experimental animals.

Male 12-week-old PVG/c [wild type (WT)] rats were obtained from Harlan (Bicester, UK), and PVG/c− (C6−/−) rats were bred in our facility. The animals weighed between 200 and 250 g and were allowed to acclimatize for at least 2 weeks before the beginning of the study. Animals were kept in the same animal facility during the entire course of the experiment and monitored for microbiological status according to the Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Associations recommendations. Animals were housed in pairs in plastic cages. They were given rat chow and water ad libitum and kept at a room temperature of 20°C on a 12 h light/dark cycle.

Genotyping of PVG/c− (C6−/−) rats.

The C6−/− rats carry a deletion of 31 bp in the C6 gene (Bhole and Stahl, 2004). Rat genomic DNA was prepared by proteinase K degradation of ear biopsies. Genotyping was performed by PCR (32 cycles) with annealing temperature at 60°C, using the following forward (5′-tggctgcctgagtagaaggt-3′) and reverse (5′-gtgaggtcagtaccttatcccc-3′) primers. The expected size of the WT PCR product was 318 bp. As a result of a 31 bp deletion, the expected size of the C6−/− PCR product was 287 bp.

Administration of human C6 for reconstitution studies.

C6 was purified from human serum as described previously (Mead et al., 2002). It was administered intravenously in four C6−/− rats at a dose of 4 mg · kg−1 · d−1 in PBS 1 d before the crush injury (day −1) and every 24 h (days 0–2) until the nerves were removed at 3 d after injury. Four WT and four C6−/− rats were treated with equal volume of vehicle (PBS) alone. The C6 reconstituted rats will be indicated in the text as C6+.

Administration of recombinant human C1INH for inhibition studies.

Recombinant human C1INH (rhC1INH) was kindly provided by Pharming (Leiden, The Netherlands). Three WT rats were injected intravenously with one dose (500 U/kg) of rhC1INH in PBS and three with vehicle (PBS) alone immediately before the crush injury. The nerves were collected after 1 h.

Hemolytic assay.

Blood samples from WT PBS-treated, C6−/− PBS-treated, and C6−/− reconstituted with purified human C6 (C6+) rats were collected from the tail vein 1 d before the crush injury (day −1) and every day after the injury (days 1–3). All samples were collected before the treatment. Plasma was separated and stored at −80°C until used to monitor C6 activity via standard complement hemolytic assay (Morgan, 2000).

Nerve crush injury and tissue processing.

All of the surgical procedures were performed aseptically under deep isoflurane anesthesia (2.5% vol isoflurane, 1 L/min O2, and 1 L/min N2O). The left thigh was shaved and the sciatic nerve was exposed via an incision in the upper thigh. The nerve was crushed for three 10 s periods at the level of the sciatic notch using smooth, curved forceps (no. 7). The crush site was marked by a suture that did not constrict the nerve. On the right side, sham surgery was performed, which exposed the sciatic nerve but did not disturb it. A suture was also placed. The muscle and the skin were then closed with stitches. The right leg served as control. After the crush, the rats were allowed to recover for 1 h (WT, n = 2; C6−/−, n = 2), 4 h (WT, n = 2; C6−/−, n = 2), 8 h (WT, n = 2; C6−/−, n = 2), 12 h (WT, n = 2; C6−/−, n = 2), 1 d (WT, n = 5; C6−/−, n = 5), 2 d (WT, n = 5; C6−/−, n = 5), 3 d (WT, n = 5; C6−/−, n = 5), and 7 d (WT, n = 5; C6−/−, n = 5). For the C6 reconstitution study, four WT PBS-treated, four C6−/− PBS-treated, and four C6−/− reconstituted with purified human C6 (C6+) rats were used. For the rhC1INH inhibition study, three WT PBS-treated and three WT C1INH-treated were used.

All the animals were intracardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in piparazine-N-N′-bis(2-ethane sulfonic acid) (PIPES) buffer, pH 7.6. Left and right sciatic nerves were removed from each animal, and one segment of 5 mm length was collected distally from the crush site. Each segment was conventionally processed into paraffin wax for immunohistochemistry. Paraffin sections of 5 μm were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin to determine tissue quality. Luxol fast blue/cresyl violet (LFB/CV) was used as a myelin stain and Palmgren's silver method to stain the axons.

Left and right tibial nerves were removed from the 1 week recovery animals, postfixed with 1% glutaraldehyde, 1% paraformaldehyde, and 1% dextran (molecular weight, 20,000) in 0.1 m PIPES buffer, pH 7.6. They were divided into one proximal and one distal segment of 10 mm length. Each segment was conventionally processed into epoxy resin. Resin sections of 0.5 μm were stained with thionine and acridine orange to further assess degenerative morphological changes.

Protein extraction and Western blot analysis.

Frozen sciatic nerves from six rats (WT, n = 3; C6−/−, n = 3) killed at 2 d after the crush injury were homogenized using a pestle and mortar in liquid nitrogen in 20 mmol L−1 Tris, pH 7.4, 5 mmol L−1 DTT, and 0.4% SDS and 6% glycerol. The homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g, at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant fraction was collected and used for protein analysis. Protein concentrations were determined with a DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard.

Protein extracts were boiled in sample buffer for 5 min, separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane overnight at 4°C. Before blotting, the nitrocellulose membranes were stained with Ponceau red for 30 s to determine protein load. The membranes were preincubated in 50 mmol L−1 Tris-HCl, 137 mmol L−1 NaCl, containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST) and 5% nonfat dried milk for 1 h at room temperature (RT). Blots were incubated for 2 h in the primary antibody (Table 1) diluted in TBST containing 5% nonfat dried milk. After washing in TBST, the membranes were incubated for 1 h in horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody diluted 1:2000 in TBST containing 5% nonfat dried milk. Membranes were washed in TBST for 3 × 10 min, and immunoreactive (IR) bands were detected using ECL (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany).

Table 1.

Antibodies, source, and dilutions

| Antibodies | Source | Dilutions |

|---|---|---|

| Polyclonal goat anti-human C1q | DakoCytomation (Glostrup, Denmark) | 1:100,a 1:1000b |

| Polyclonal rabbit anti-human C1r | DakoCytomation | 1:100,a 1:1000b |

| Polyclonal rabbit anti-human C1s | DakoCytomation | 1:100,a 1:1000b |

| Polyclonal rabbit anti-human C3c | DakoCytomation | 1:750 |

| Polyclonal rabbit anti-human C4c | DakoCytomation | 1:100 |

| Polyclonal rabbit anti-rat C9 | B. P. Morgan | 1:300 |

| Polyclonal rabbit anti-human MBP | DakoCytomation | 1:100,a 1:50c |

| Monoclonal mouse anti-human | Sternberger (Lutherville, MD) | 1:1000 |

| Phosphorylated neurofilament (SMI31 clone) | ||

| Monoclonal mouse anti-rat CD11b (ED7 clone) | C. Dijkstra (VU University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) | 1:100 |

| Monoclonal mouse anti-rat CD68 (ED1 clone) | Serotec (Oxford, UK) | 1:100,a 1:50c |

| Monoclonal mouse anti-rat Pan (Ki-M2R clone) | Acris (Hiddenhausen, Germany) | 1:100 |

| Polyclonal rabbit anti-cow S100 | DakoCytomation | 1:400 |

aDilution used in the colorimetric immunostaining.

bDilution used in the Western blotting.

cDilution used in the fluorescence immunostaining.

Immunohistochemistry.

Paraffin wax sections were stained using a three-step immunoperoxidase method. All of the incubations were performed at RT. After deparaffination and rehydration, endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 1% H2O2 in methanol for 20 min. In all cases, antigen retrieval with microwave at 800 W for 3 min followed by 10 min at 440 W in 10 mm Tris/1 mm EDTA, pH 6.5, was used. To block the nonspecific binding sites, slides were incubated in 10% normal goat serum in Tris buffer (TBS) for 20 min. After incubation in the appropriate primary antibody diluted in 1% BSA (Table 1) for 90 min, sections were incubated for 30 min in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse from DakoCytomation (Glostrup, Denmark) diluted 1:200 in 1% BSA and 30 min in horseradish peroxidase-labeled polystreptavidin (ABC complex; DakoCytomation). To visualize peroxidase activity, the slides were incubated in 0.05% 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole in acetate buffer, pH 5, for 5 min followed by a 30 s counterstaining with hematoxylin and mounted in gelatin. For immunofluorescence, the primary antibody and either the secondary sheep anti-mouse Cy3-conjugated or goat anti-rabbit FITC-conjugated or rabbit anti-goat FITC-conjugated antibody from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) were diluted in TBS. The slides were mounted in Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Sections immunostained with secondary conjugate alone were included with every experiment as negative controls, whereas sections of rat spinal cord and lymph nodes served as positive controls.

Images were captured with a digital camera (DP12; Olympus, Zoeterwoude, The Netherlands) attached to a fluorescent microscope (Vanox AHBT3; Olympus), a light microscope (BX41; Olympus), or a microscope (Axioplan; Zeiss, Weesp, The Netherlands) connected to a laser-scanning confocal imaging system (MRC 1024; Bio-Rad) and analyzed with analysis software (AnalySIS; Soft Imaging System, Zoeterwoude, The Netherlands).

CD68-, CD11b-, and Pan-IR cell count.

CD68 (ED1 clone) antibody is a lysosomal marker commonly used for macrophages but also stains other phagocytic cells. CD11b (ED7 clone) is a marker for complement 3 receptor (CR3) on activated macrophages and Pan (Ki-M2R) is a surface antigen marker of resident-like tissue macrophages. Cells were scored positive when the ED1-, ED7-, or Ki-M2R-positive signal was associated with nuclei. Three to five nonconsecutive sections of rat sciatic nerve per animal were examined for each of the three series of immunostained slides. Each series included four groups (0, 1, 2, and 3 d) and five or four animals for each rat type (WT, C6−/−, C6+, PBS) per group. An average of three nonoverlapping fields of view including >90% of the entire nerve area was taken for each section examined. Cell number is expressed per square millimeter.

Electron microscopy.

Electron microscopy was performed on ultrathin sections of the tibial nerve from WT and C6−/− rats at 7 d after the crush injury. Sections were contrasted with uranyl acetate and lead citrate as described previously (King, 1999). Images were captured with a digital camera attached to an electron microscope (FEO 10; Philips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

Statistical analysis.

Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's correction was performed to determine statistically significant differences in the hemolytic assay (p ≤ 0.001) and in the CD68-, CD11b-, and Pan-IR cell count (p ≤ 0.05).

Results

Characterization of WT, C6-deficient (C6−/−), and C6-reconstituted (C6+) PVG/c rats

PVG/c WT rats were obtained from Harlan, and C6−/− rats were bred in our facility. Their C6 status was confirmed by genotyping analysis and standard complement hemolytic assay (CH50). Because C6−/− rats have a 31 bp deletion in exon 10 (Bhole and Stahl, 2004), primers flanking the deletion site were designed for genotyping analysis by PCR using genomic DNA isolated from the rat ears. As expected, the PCR product from C6−/− rats (287 bp) is smaller than that of WT rats (318 bp) (supplemental Fig. 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material).

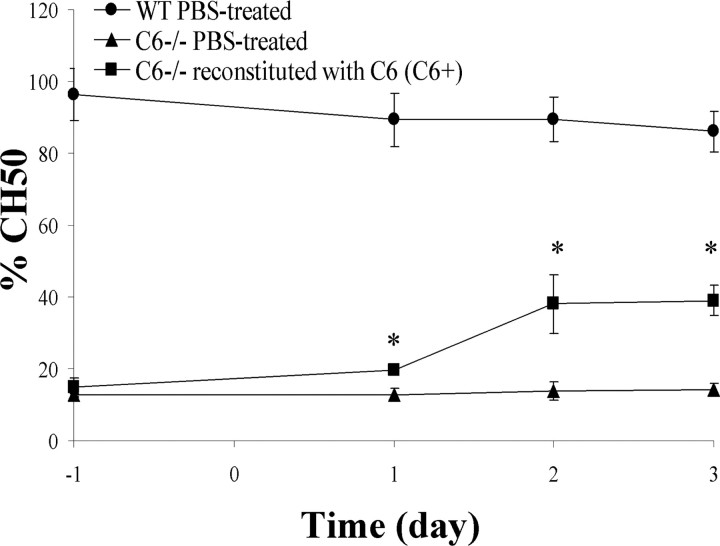

Plasma hemolytic activity (CH50) of WT, C6−/−, and C6+ rats was monitored over the entire course of the experiment. WT rats had an average basal CH50 of 96.3 ± 7.3 (day −1), which did not change significantly after PBS treatment (day 1, 89.4 ± 7.5; day 2, 89.5 ± 6.2; day 3, 86.1 ± 5.6). C6−/− rats had an average basal CH50 of 12.6 ± 0.6 (day −1) and remained at control levels after PBS treatment (day 1, 12.8 ± 1.6; day 2, 13.8 ± 2.7; day 3, 14.2 ± 1.9). To reconstitute C6 activity in C6−/− rats, C6 was purified from fresh frozen human plasma by affinity chromatography. It was administered in vivo by repeated intravenous injections at a dose of 4 mg · kg−1 · d−1. Hemolytic activity of C6−/− rat plasma increased to 40% of that of WT rats, from a basal CH50 of 15.1 ± 2.6 to 39.1 ± 4.3 at 4 d from the start of the treatment (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Hemolytic assay. Complement-dependent hemolysis in serum from WT PBS-treated, C6−/− PBS-treated, and C6−/− reconstituted with purified human C6 (C6+) rats. Treatment started 1 d (day −1) before the injury (day 0), and it was repeated at days 1 and 2 after injury. Plasma was collected immediately before the treatment at days −1, 1, 2, and 3. Values are means ± SD of four animals per group. *Statistical significance refers to p ≤ 0.001 determined by a two-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni's correction.

C6 deficiency protects from rapid WD after acute nerve trauma

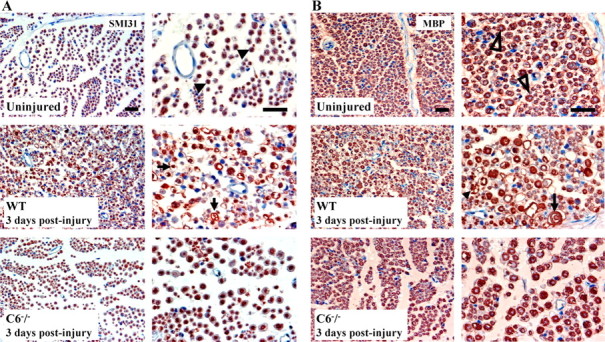

To determine the role of C6 in WD, we performed a crush injury of the sciatic nerve in WT, C6−/−, and C6+ rats. WD of the sciatic nerve after injury was monitored on paraffin sections by immunohistochemical analysis with antibodies that recognize phosphorylated neurofilament (SMI31 clone) and myelin basic protein (MBP) and by histological analysis with Palmgren's silver staining and LFB/CV. Semithin sections of tibial nerves were also analyzed.

In the WT nerves, SMI31 immunostaining showed axonal swelling and degradation at 2 d after injury (data not shown), and it was more evident after 3 d. However, the C6−/− nerves showed well preserved axons at 3 d after crush (Fig. 2A). MBP immunostaining revealed signs of myelin breakdown in WT nerves at 2 d after the injury and complete degradation after 3 d. However, the C6−/− nerves showed myelin morphology comparable with that of control nerves at 3 d after crush (Fig. 2B). Histological analysis with Palmgren's silver staining and LFB/CV confirmed the results obtained with the immunohistological assay (data not shown). Both WT and C6−/− rats treated with vehicle only served as controls. Their histology did not differ from the untreated rats (data not shown). These observations suggest that C6 deficiency protects the axons and the myelin from Wallerian degeneration at 3 d after injury.

Figure 2.

Immunohistological analysis of axons and myelin. A, Immunostaining for phosphorylated neurofilament (SMI31 clone) in cross sections of WT and C6−/− rat sciatic nerves. Note the typical punctate axonal staining in the uninjured nerve (▶). At 3 d after injury, the WT nerve shows axonal swelling and degradation (→), whereas the axons of the C6−/− nerve are still intact. B, Immunostaining for MBP in cross sections of WT and C6−/− rat sciatic nerves. Note the typical annulated staining of the myelin in the uninjured nerve (▷). At 3 d after injury, the WT nerve shows myelin degeneration (→) and degradation products (▶), whereas the myelin of the C6−/− nerve is still intact. Sections are counterstained with hematoxylin. Two magnifications of the same section are shown for each nerve type. Scale bar, 50 μm.

C6 reconstitution restores rapid WD after acute nerve trauma

Reconstitution of C6-deficient animals with C6 (C6+) resulted in rapid axonal degradation in the C6−/− nerves. Myelin breakdown was also restored at 3 d after injury in the C6−/− nerves after C6 reconstitution (supplemental Fig. 2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). The C6+ uninjured nerve was used as control and showed intact axons and myelin (data not shown). These data demonstrate that the protection of the injured nerve from WD observed in the mutant mice at 3 d after crush is a specific effect of C6 deficiency.

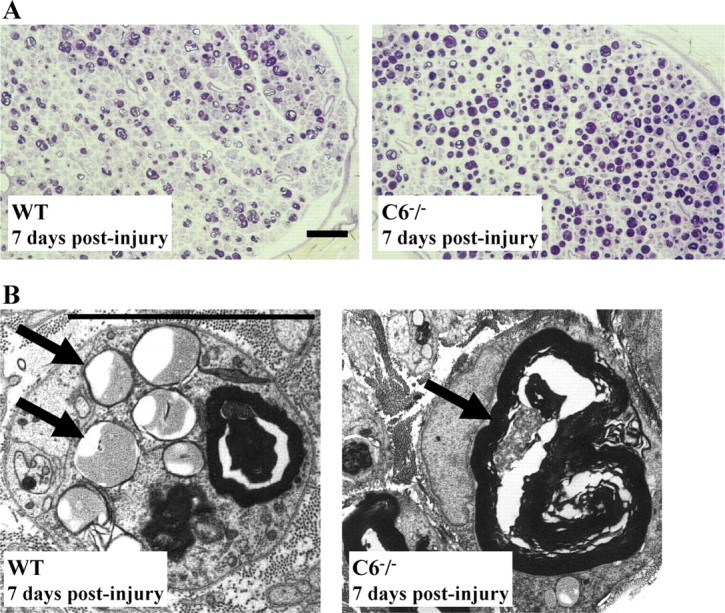

WD and myelin clearance are delayed in C6-deficient animals after acute nerve trauma

Analysis of the sciatic and tibial nerves (distal from the sciatic nerve where the crush injury was performed) at 7 d after injury showed WD in both WT and C6−/− nerves, demonstrating that Wallerian degeneration has a delayed onset in C6−/− nerves after the crush injury. As a result of delayed degeneration, more thionine-stained myelin debris was present in the C6−/− than in WT nerves (Fig. 3A). Electron microscopy revealed that complex lipids are still present in the C6−/− nerves, whereas signs of simple lipids dissolved by the dehydration processing are found in the WT nerves (Fig. 3B). These data show that, subsequent to the delayed degeneration, myelin clearance is delayed in the C6−/− nerves.

Figure 3.

Histological analysis of myelin debris. A, Thionine staining of semithin cross sections of the distal ends of WT and C6−/− rat tibial nerves at 7 d after the crush injury. Note the higher density of myelin debris (purple) in the C6−/− nerve compared with the WT. Scale bar, 50 μm. B, EM images of myelin debris from sections in A. Note the myelin degraded into lipid droplets in the WT nerve and early myelin breakdown products in the C6−/− nerve (→). Scale bar, 10 μm.

The complement system is activated after acute nerve trauma

To determine the time course of complement activation after crush injury, we measured expression levels of the classical pathway complement components and monitored deposition of activated cleaved complement proteins.

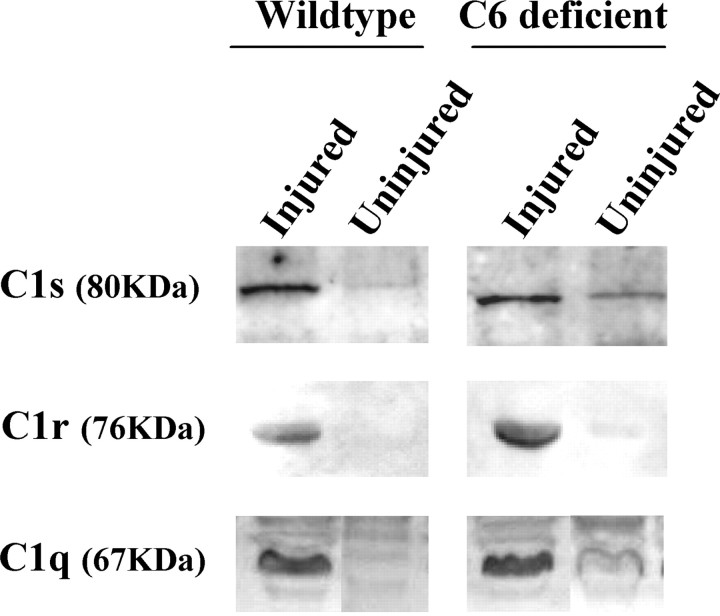

Low levels of C1s, C1q, and C1r immunoreactivity were detected in protein extracts of uninjured WT and C6−/− rat nerves, whereas high levels were seen at 2 d after the crush injury (Fig. 4). Accordingly, a high level of C1s, C1q, and C1r immunoreactivity was detected on sciatic nerve cross sections from animals killed at 3 d after the crush (supplemental Fig. 3, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Immunoreactivity for C4c and C3c (the activated cleaved products of C4 and C3) was detected in all injured nerves at 3 d after injury (Fig. 5). These results show that activation of C components upstream of C6 occurred also in C6−/− rats. However, because of the degeneration of the nerve in WT and C6+ rat nerves, but not in the C6−/− ones, direct comparisons of the amount of deposited C components on the nerve tissue is not possible. These data suggest a normal function of C proteins upstream of MAC formation in the C6−/− rat model. C activation happened as early as 1 h after the injury (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Upregulation of complement components in injured rat nerve. Western blotting analysis of WT and C6−/− rat sciatic nerves at 2 d after injury, showing higher amount of C1s, C1r, and C1q proteins in the injured nerves compared with the uninjured controls.

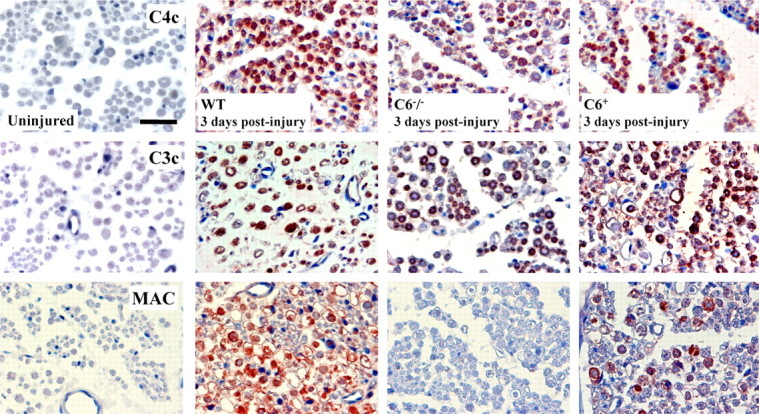

Figure 5.

Deposition of activated complement components in injured rat nerve. Immunostaining for the activated cleaved complement components C4c and C3c and the terminal cytolytic component MAC in cross sections of WT, C6−/−, and C6+ rat sciatic nerves at 3 d after injury. High immunoreactivity of C4c and C3c is detected in all injured nerves, whereas no immunoreactivity is detected in the uninjured controls. MAC immunoreactivity is present in injured WT nerves but not in the C6−/− and uninjured controls. C6 reconstitution reestablished MAC deposition in the C6+ injured nerves. Sections are counterstained with hematoxylin. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Deposition of MAC was observed in WT nerves at 12 h (data not shown) and up to 3 d after injury. MAC was localized in the axonal compartment of the nerve as shown by the complete colocalization with the neurofilament staining. Additional MAC staining was present in the nerve and probably deposited on the degrading myelin sheaths (supplemental Fig. 4, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). The C6−/− nerves were negative for MAC deposition, which was restored after C6 reconstitution (C6+), confirming lack of C6 in the deficient nerves and the ability of purified human C6 to reach the nerve from the circulation and be functional. Uninjured control nerves were always negative for MAC staining (Fig. 5).

rhC1INH blocks complement activation after acute nerve trauma

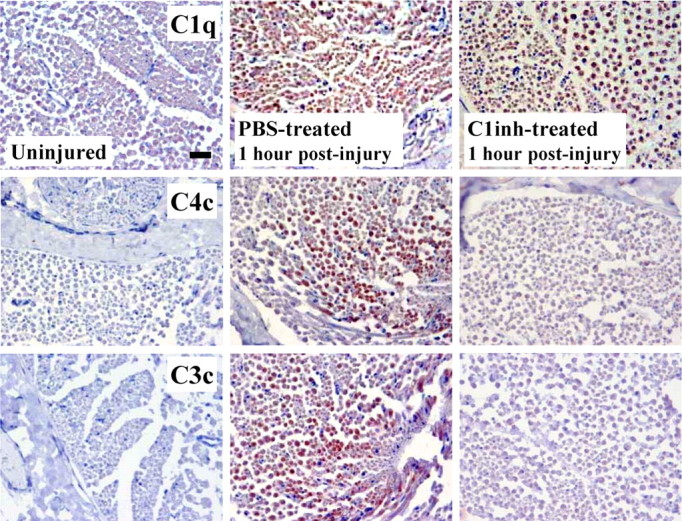

To determine which complement pathway is activated after the crush injury, we treated WT rats with rhC1INH, an inhibitor of the classical pathway. Complement activation upstream and downstream of the inhibitors' target were monitored in rhC1INH-treated rats after the injury. Detection of dense deposits of C1q (C component upstream of the rhC1INH target site) in the PBS- and rhC1INH-treated nerves confirmed upregulation of the classical pathway complement components after the injury. C4c and C3c (C components downstream of the rhC1INH target site) deposition was very high in the PBS-treated nerves and completely absent in the inhibitor-treated nerves at 1 h after injury (Fig. 6). This demonstrates that the classical pathway is activated and that, at least at this early time point, the alternative pathway does not contribute to the activation of the complement cascade after nerve injury.

Figure 6.

Blockade of complement activation after rhC1INH treatment. Immunostaining for complement component C1q, upstream of the target of rhC1INH, and cleaved components C4c and C3c at 1 h after injury in cross sections of sciatic nerves from WT rats treated with rhC1INH or vehicle (PBS) alone. High immunoreactivity for C1q is detected in all injured nerves, confirming C1q upregulation after the crush injury. C4c and C3c immunoreactivity is detected in the PBS-treated nerves as expected, whereas no deposition is detected in the nerves from the rhC1INH-treated rats, demonstrating effective blockade of the complement cascade after crush and implicating the classical pathway in the crush injury model of Wallerian degeneration. Sections are counterstained with hematoxylin. Scale bar, 50 μm.

C6 deficiency protects the nerve from macrophage accumulation and activation at 3 d after injury

Because myelin removal in degenerating nerves mainly depends on invading, nonresident macrophages (Beuche and Friede, 1984), we monitored macrophage recruitment and activation. Sections were analyzed with the CD68 (ED1 clone) antibody, which is used as a lysosomal marker; CD11b (ED7 clone), which detects the rat CR3 present on activated macrophages (Damoiseaux et al., 1989) and essential for myelin phagocytosis (Bruck and Friede, 1990, 1991; Reichert and Rotshenker, 2003); and Pan (Ki-M2R clone) antibody, which recognizes a surface antigen on resident tissue macrophages.

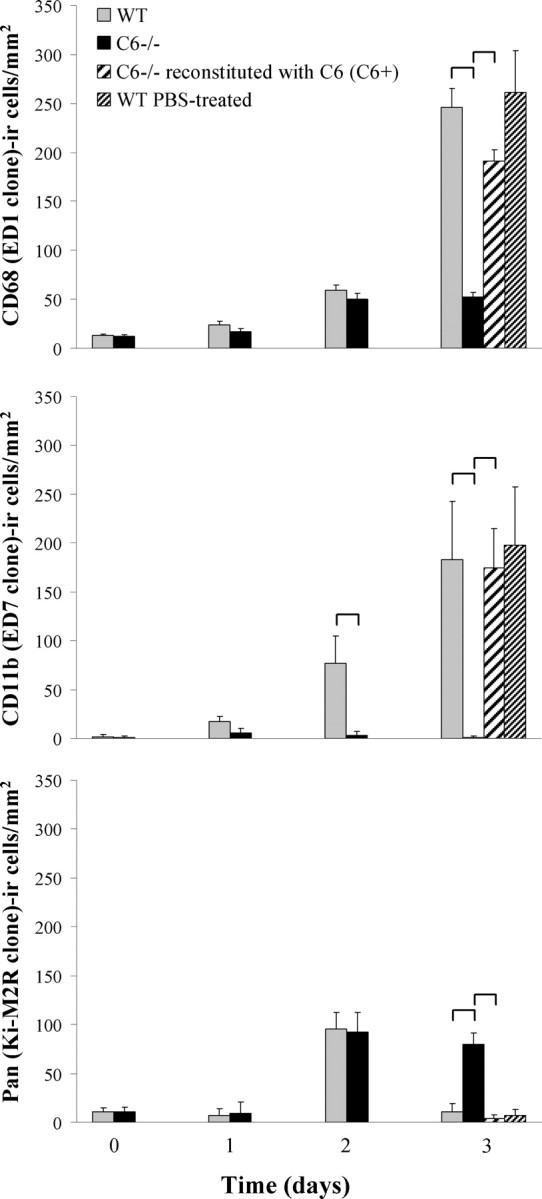

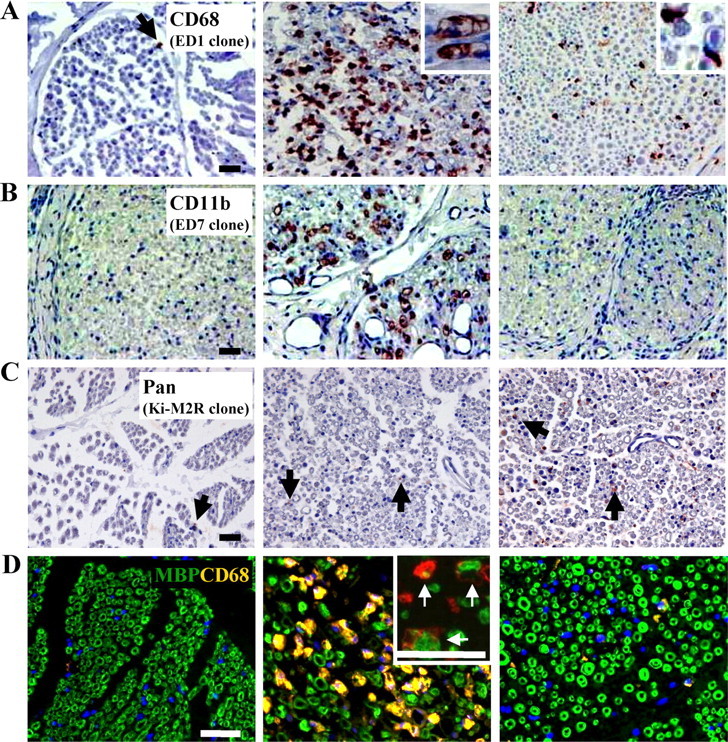

A quantitative analysis (Fig. 7) revealed only a few CD68-positive cells (WT, 13.2 ± 1.7; C6−/−, 12.6 ± 1.4) in the uninjured nerves. In both, WT and C6−/− nerves, the number of CD68-positive cells remained at control levels until 2 d after injury when they increased to 59.4 ± 4.2 and 49.8 ± 11.2, respectively. At 3 d after injury, the CD68 immunoreactivity was significantly higher in the WT crushed nerves (245.8 ± 19.6) compared with the C6−/− ones (52.4 ± 6.4). After reconstitution of the C6−/− nerves with C6, the number of CD68-positive cells increased close to WT levels (191.2 ± 9.8). Treatment of WT animals with PBS did not alter significantly the number of CD68-positive cells in the injured nerves (261.2 ± 42.9). A morphological analysis of the CD68-IR cells at 3 d after injury showed enlarged and asymmetrical cells in WT nerves, whereas they remained small and round in the C6−/− nerves (Fig. 8A; A, insets). C6 reconstitution reestablished the WT phenotype (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Quantitative analysis of macrophages. Quantification of CD68 (ED1 clone), CD11b (ED7 clone), and Pan (Ki-M2R)-IR cells in nonconsecutive sections of sciatic nerves from WT, C6−/−, C6+, and WT PBS-treated rats at 0 (uninjured nerve), 1, 2, and 3 d after injury. Values are means ± SD of four to five animals per group. Statistical significance between groups (brackets) refers to p ≤ 0.05 determined by a two-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni's correction.

Figure 8.

Immunohistological analysis of macrophages. A, CD68 staining of WT and C6−/− rat sciatic nerves at 3 d after injury. The insets show the morphology of foamy CD68-IR macrophages in the WT nerve, whereas small CD68-IR macrophages are detected in the C6−/− nerve. Little CD68 immunoreactivity is detected in the uninjured control nerve. B, CD11b staining at 3 d after injury, showing activated macrophages in the WT but not in the C6−/− nerve or uninjured controls. C, Ki-M2R staining at 3 d after injury, showing macrophages with resident-like phenotype in the C6−/− nerves, whereas little immunoreactivity is detected in the WT nerves. Sections in A–C are counterstained with hematoxylin. D, Double immunofluorescent staining for CD68 (orange/red) and MBP (green) showing CD68-IR cells engulfing myelin debris (confocal images in insets, →) in the WT nerve. The nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 50 μm.

The number of CD11b-positive cells was very low in the uninjured nerves (WT, 1.2 ± 2.5; C6−/−, 0.6 ± 1.9), but it increased in the WT nerves at 1 d (17.4 ± 2.5) and 2 d (76.5 ± 28.3) after injury, reaching 182.9 ± 59.7 after 3 d. The C6−/− nerves did not show any significant change in the number of CD11b-positive cells after injury. In the C6+ nerves, the number of CD11b-positive cells increased close to WT levels at 3 d after injury (174.8 ± 39.9). Treatment of WT animals with PBS did not alter significantly the number of CD11b-positive macrophages in the injured nerves (197.9 ± 59.9). The increase in CR3 immunoreactivity demonstrates macrophage activation in the WT nerves but not in the C6−/− nerves.

Strong immunoreactivity of CD11b was associated with large macrophages in WT, C6+, and PBS-treated nerves at 3 d after injury. In contrast, C6−/− nerves contained very few cells slightly positive for the CD11b macrophage marker (Fig. 8B). The low CR3 staining is not an inherent property of C6−/− rats, because lymph nodes of C6−/− rats contained cells that were strongly positive for CD11b (supplemental Fig. 5, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material).

The Pan macrophage marker showed a few positive cells (WT, 10.6 ± 4.4; C6−/−, 11.2 ± 4.0) in the uninjured nerves. In both WT and C6−/− nerves, the number of Pan-positive cells remained at control levels until 2 d after injury when they increased to 95.2 ± 17.0 and 92.1 ± 20.2, respectively. At 3 d after injury, the number of Pan-positive cells did not change in the C6−/− nerves, whereas it dropped to 11.2 ± 7.9 in the WT nerves, demonstrating that macrophages lose the resident-like phenotype in the WT nerves, but this is still maintained by the macrophages in the C6−/− nerves. Both the C6+ and PBS-treated nerves showed similar Pan immunoreactivity as the WT nerves (C6+, 3.7 ± 7.9; PBS, 6.8 ± 11.2). Pan-IR cells were generally very small, a morphology typical of macrophages that retain the resident-like phenotype (Fig. 8C).

Confocal images of double immunofluorescent staining of CD68 and MBP showed myelin debris in the enlarged CD68-positive cells in WT and C6+ nerves at 3 d after injury (Fig. 8D, inset), demonstrating active myelin phagocytosis by the CD68-IR cells. These data demonstrate that C6 deficiency prevents macrophage accumulation and activation in the WT nerve at 3 d after injury.

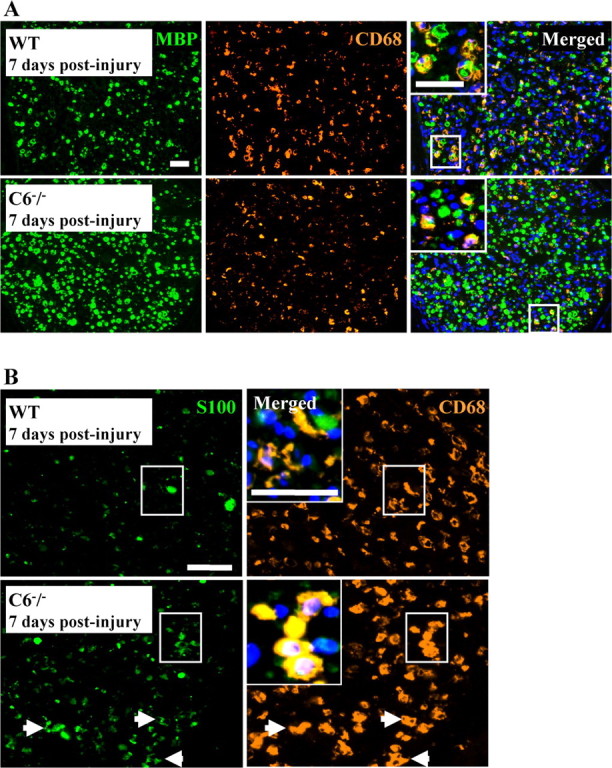

Analysis of phagocytic cells at 7 d after injury

There was no significant difference in the number of CD68-IR cells between WT (189.28 ± 40.6) and C6−/− (171.1 ± 29.4) nerves at 7 d after injury, and in both strains they contained myelin debris as shown by their colocalization with MBP (Fig. 9A). However, in the WT nerve, CD68-IR cells were also CD11b positive, suggesting that they were macrophages. In the C6−/− nerve, CD68-IR cells were negative for CD11b (data not shown). Because there is evidence that proliferating Schwann cells contribute to myelin degradation (Hirata and Kawabuchi, 2002), we stained the nerve sections with S100, a Schwann cell marker, and colocalized it with the CD68 antibody. Virtually all CD68-IR cells in the C6−/− nerves were S100 positive (Fig. 9B), whereas in the WT nerves only a minority of the CD68 cells were S100 positive. These results demonstrate that, although cells containing myelin debris are present in both strains at 7 d after injury, they differ in nature.

Figure 9.

Analysis of phagocytic Schwann cells. A, Double immunofluorescent staining for MBP (green) and CD68 (orange) of rat sciatic nerve at 7 d after the crush injury, showing higher density of myelin debris in the C6−/− nerve compared with the WT nerve, whereas the number of CD68-IR cells is similar in both nerves. Note the vacuolated morphology of CD68-IR cells in the WT nerve, typical of foamy macrophages. The merged images show colocalization of MBP and CD68 staining in both nerves (yellow and inset). B, Double immunofluorescent staining for S100 (green) and CD68 (orange) of rat sciatic nerve at 7 d after the crush injury, showing complete colocalization (yellow) in the C6−/− nerve (→ and inset), whereas in the WT only a few CD68-IR cells are also S100 positive. Note the higher S100 immunoreactivity in the C6−/− nerve compared with the WT. Nuclear staining with DAPI (blue) is included in the merged images. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Discussion

This study shows that formation of the MAC is necessary for rapid WD. Signs of WD were already detected in the WT nerves at 2 d after the injury, with extensive axonal and myelin degeneration after 3 d. This is consistent with the well documented observations of Waller (1850) and Ramón y Cajal (1991). Interestingly, no signs of WD were detected at 3 d after the crush in the C6−/− nerves, suggesting that the inability to form the MAC protects from early axonal and myelin degeneration after injury. Reconstitution of C6−/− animals with C6 restored WD at 3 d after injury, demonstrating that the difference in the early phase of WD is attributable to the lack of C6. However, WD was not permanently blocked in the C6−/− animals, because complete axonal and myelin degradation was observed at 7 d after injury.

This study specifically addresses the current controversial issue of whether or not formation of the MAC is needed in the complement-mediated destruction of nervous tissue that occurs in numerous diseases of the central and peripheral nervous system (Bonifati and Kishore, 2007). Our results demonstrate that the ability to assemble the MAC is crucial in the initial events leading to axon loss and myelin breakdown. This work supports previous studies by Mead et al. (2002, 2004), who showed delayed demyelination in C6−/− rats affected by antibody-mediated experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (ADEAE), a model of multiple sclerosis, and enhanced axonal injury and demyelination in ADEAE mice deficient in the MAC inhibitory regulator CD59.

Because the C6−/− animals have normal function in the upstream members of the complement cascade, we can discriminate between the specific role of MAC and other functions of the complement proteins like opsonization and chemotaxis during WD. Deposition of the MAC occurred at multiple sites in the nerve including the axonal compartment, as demonstrated by its colocalization with the neurofilament staining. Accumulation of MAC deposits on nervous tissue can damage membranes; a devastating event for the fate of a nerve is the uncontrolled calcium influx through the MAC-derived pores (Schlaepfer and Bunge, 1973). Calcium activates calpains, calcium-dependent proteases that cleave cytoskeletal proteins including neurofilament, resulting in structural disorganization of the nerve. Calpain inhibitors were protective against axonal cytoskeletal loss in a model of complement-mediated motor nerve terminal injury (O'Hanlon et al., 2003). MAC deposits have been found on damaged nerve terminal axons and surrounding perisynaptic Schwann cells in a mouse model of neuropathy and the damage was exacerbated in tissues from mice lacking CD59, in which MAC formation is increased (Halstead et al., 2004). A follow-up study showed that inhibition of complement activation with APT070 blocked MAC formation and rescued axonal and perisynaptic Schwann cell integrity (Halstead et al., 2005).

Systemic treatment with rhC1INH blocked the classical pathway and reduced acute damage in the treated injured nerve. However, because of its short half-life, long-term experiments were not possible. This experiment demonstrates involvement of the classical pathway of the complement system in WD after acute nerve trauma but does not exclude a later contribution of the alternative pathway.

Recruitment of macrophages is a known function of activated complement components. The analysis of macrophages in WT rat nerves before and after the injury confirmed the pattern described previously (Beuche and Friede, 1984; Bendszus and Stoll, 2003; Omura et al., 2005). In the control uninjured nerve, a small number of endoneurial macrophages is present. These consist of both long-term and short-term resident macrophages (Mueller et al., 2001). The slight increase in CD68-positive cells in both WT and C6−/− nerves as early as 2 d after injury is probably attributable to proliferation and differentiation of the endoneurial macrophage population that still retains the resident-like (Pan-positive) phenotype but starts to express the CD68 lysosomal marker. These macrophages have the potential to phagocytose myelin (Leonhard et al., 2002). At this time point, in WT nerve, macrophages express high levels of the CR3 receptor, which is essential for myelin phagocytosis (Bruck and Friede, 1990, 1991; Reichert and Rotshenker, 2003), whereas in the C6−/− nerves CR3 expression is virtually undetectable, consistent with the small and round morphology typical of inactive macrophages. At 3 d after the crush, the pattern of expression of all three (CD68, CD11b, and Pan) macrophage markers differs between the two strains. In WT nerves, considerable increase in CD68-positive cells occurs. These cells maintain the activated (CD11b-positive) but lose the resident-like (Pan-positive) phenotype, and contain vacuoles and myelin debris within lysosomes. At 7 d after injury, CD68 immunoreactivity is still very high in the WT nerve. Most of these cells are macrophages and still maintain the activated phenotype (CD11b-positive). At this time point, myelin is almost completely removed.

The C6−/− rats show a different pattern of macrophage response. After the initial (2 d) increase, no further accumulation of macrophages occurs at 3 d after injury. Cells maintain the resident-like phenotype (Pan-positive) and no evidence of myelin activation (CD11b-immunoreactivity) or phagocytosis (MBP-CD68 colocalization) was observed, explaining the integrity of the myelin sheath. This lack of macrophage activation is dependent on C6 because reconstituting the C6−/− animals restored the WT phenotype. Thus, a C6-dependent factor, MAC formation, and not C3 as suggested previously (Dailey et al., 1998), is essential for efficient macrophage accumulation and activation during WD. In the C6−/− ADEAE rat model, which is protected from demyelination at least up to 14 d after disease induction, macrophages accumulate in the nerve but they fail to engulf myelin (Mead et al., 2002).

At 7 d after injury, the C6−/− nerve, which has degenerated by this time, shows extensive CD68 immunoreactivity. These cells are probably Schwann cells, because they are positive for the Schwann cell marker S100 and negative for the CD11b and Pan macrophage markers. CD68-positive phagocytic Schwann cells have been described previously (Liu et al., 1995), and our in vitro-cultured Schwann cells are also occasionally CD68 positive (data not shown). These CD68/S100-positive cells contained myelin debris, suggesting that Schwann cells can digest myelin in the absence of macrophages in vivo, which is in line with the in vitro data (Fernandez-Valle et al., 1995).

We propose the following model (supplemental Fig. 6, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). After crush, C1q binds axonal and myelin epitopes exposed by the mechanical injury, activating the classical pathway. The damaged nerve is then opsonized by C4b, C3b, and C5b, which act as opsonins for macrophages. In the WT animals, formation of MAC creates pores on the axolemma allowing influx of calcium, into the axon. This activates calpains contributing to the rapid damage of the nerve. The MAC-induced neuronal debris is also targeted by C1q, creating a positive-feedback loop resulting in increased opsonization and macrophage recruitment and activation leading to rapid degeneration. In the C6−/− rats, the crush-derived debris is the only target for opsonization and not sufficient for efficient activation of macrophages to acquire the phagocytic phenotype. WD and myelin removal in the absence of C6 is performed in a slow, opsonin-independent manner by proliferating Schwann cells.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the classical pathway of the complement system is activated after acute nerve trauma and that the entire complement cascade, including MAC deposition, is essential for rapid WD and efficient clearance of myelin after acute peripheral nerve trauma.

Wallerian degeneration is a process common to many injury- and noninjury-related disorders of the peripheral and central nervous system. (Coleman and Perry, 2002). It results in axon loss, which is the major determinant of disability in such disorders. Understanding the mechanisms of axonal degradation could lead to new therapies aimed at delaying or preventing axon loss. Our study shows that activation of complement, specifically MAC, is responsible for the early events of axonal degradation during WD. Complement inhibition or blockade of calcium-dependent proteases could protect the axon from the initial degradation.

Complement blockade (Halstead et al., 2005), calcium depletion, and calpain inhibition (O'Hanlon et al., 2003) have been shown previously to limit nerve terminal and axonal injury in a model of acquired peripheral neuropathy. We propose that complement inhibition could directly prevent axonal damage and indirectly inhibit macrophage accumulation in the nerve, ameliorating the disease outcome.

In some neurodegenerative diseases like multiple sclerosis, axonal damage has only recently emerged as a substantial determinant of pathology (Papadopoulos et al., 2006). Delaying axonal degeneration could give a chance for more axons to survive a period of demyelination, arresting the decline from the relapsing–remitting to the progressive phase of the disease. Traumatic brain and spinal cord injuries are characterized by diffuse axon loss and complement activation (Leinhase et al., 2006). Pathology secondary to the primary mechanical damage appears to be a major determinant of clinical outcome (Graham et al., 2000). The secondary axonal damage occurs hours after the initial insult, opening a window of opportunity for therapy aimed at rescuing the axons. Inhibition of complement activation could prevent spreading of secondary axon loss.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant from the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research) to F.B. We thank our colleagues of the Neurogenetics Laboratory, Drs. M. Daha and I. N. van Schaik for stimulating discussions and comments on this manuscript. We thank Dr. C. Dijkstra for the CD11b (ED7 clone) antibody.

References

- Ballin RH, Thomas PK. Changes at the nodes of Ranvier during Wallerian degeneration: an electron microscope study. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1969;14:237–249. doi: 10.1007/BF00685303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnum SR, Szalai AJ. Complement and demyelinating disease: no MAC needed? Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2006;52:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendszus M, Stoll G. Caught in the act: in vivo mapping of macrophage infiltration in nerve injury by magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10892–10896. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10892.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuche W, Friede RL. The role of non-resident cells in Wallerian degeneration. J Neurocytol. 1984;13:767–796. doi: 10.1007/BF01148493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhole D, Stahl GL. Molecular basis for complement component 6 (C6) deficiency in rats and mice. Immunobiology. 2004;209:559–568. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifati DM, Kishore U. Role of complement in neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruck W, Friede RL. Anti-macrophage CR3 antibody blocks myelin phagocytosis by macrophages in vitro. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1990;80:415–418. doi: 10.1007/BF00307696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruck W, Friede RL. The role of complement in myelin phagocytosis during PNS Wallerian degeneration. J Neurol Sci. 1991;103:182–187. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(91)90162-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman MP, Perry VH. Axon pathology in neurological disease: a neglected therapeutic target. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:532–537. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey AT, Avellino AM, Benthem L, Silver J, Kliot M. Complement depletion reduces macrophage infiltration and activation during Wallerian degeneration and axonal regeneration. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6713–6722. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06713.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damoiseaux JG, Dopp EA, Neefjes JJ, Beelen RH, Dijkstra CD. Heterogeneity of macrophages in the rat evidenced by variability in determinants: two new anti-rat macrophage antibodies against a heterodimer of 160 and 95 kd (CD11/CD18) J Leukoc Biol. 1989;46:556–564. doi: 10.1002/jlb.46.6.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge RR, van Schaik IN, Vreijling JP, Troost D, Baas F. Expression of complement components in the peripheral nervous system. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:295–302. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Valle C, Bunge RP, Bunge MB. Schwann cells degrade myelin and proliferate in the absence of macrophages: evidence from in vitro studies of Wallerian degeneration. J Neurocytol. 1995;24:667–679. doi: 10.1007/BF01179817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita T, Matsushita M, Endo Y. The lectin-complement pathway—its role in innate immunity and evolution. Immunol Rev. 2004;198:185–202. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass JD. Wallerian degeneration as a window to peripheral neuropathy. J Neurol Sci. 2004;220:123–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham DI, McIntosh TK, Maxwell WL, Nicoll JA. Recent advances in neurotrauma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:641–651. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.8.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstead SK, O'Hanlon GM, Humphreys PD, Morrison DB, Morgan BP, Todd AJ, Plomp JJ, Willison HJ. Anti-disialoside antibodies kill perisynaptic Schwann cells and damage motor nerve terminals via membrane attack complex in a murine model of neuropathy. Brain. 2004;127:2109–2123. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstead SK, Humphreys PD, Goodfellow JA, Wagner ER, Smith RA, Willison HJ. Complement inhibition abrogates nerve terminal injury in Miller Fisher syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:203–210. doi: 10.1002/ana.20546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpel PC, Cooper NR. Studies on human plasma C1 inactivator-enzyme interactions. I. Mechanisms of interaction with C1s, plasmin, and trypsin. J Clin Invest. 1975;55:593–604. doi: 10.1172/JCI107967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata K, Kawabuchi M. Myelin phagocytosis by macrophages and nonmacrophages during Wallerian degeneration. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;57:541–547. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RHM. Atlas of peripheral nerve pathology. New York: Oxford UP; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Leenaerts PL, Stad RK, Hall BM, Van Damme BJ, Vanrenterghem Y, Daha MR. Hereditary C6 deficiency in a strain of PVG/c rats. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;97:478–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinhase I, Schmidt OI, Thurman JM, Hossini AM, Rozanski M, Taha ME, Scheffler A, John T, Smith WR, Holers VM, Stahel PF. Pharmacological complement inhibition at the C3 convertase level promotes neuronal survival, neuroprotective intracerebral gene expression, and neurological outcome after traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2006;199:454–464. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhard C, Muller M, Hickey WF, Ringelstein EB, Kiefer R. Lesion response of long-term and recently immigrated resident endoneurial macrophages in peripheral nerve explants cultures from bone marrow chimeric mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:1654–1660. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HM, Yang LH, Yang YJ. Schwann cell properties: 3. C-fos expression, bFGF production, phagocytosis and proliferation during Wallerian degeneration. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1995;54:487–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Lioudyno M, Tao R, Eriksson P, Svensson M, Aldskogius H. Hereditary absence of complement C5 in adult mice influences Wallerian degeneration, but not retrograde responses, following injury to peripheral nerve. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 1999;4:123–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead RJ, Singhrao SK, Neal JW, Lassmann H, Morgan BP. The membrane attack complex of complement causes severe demyelination associated with acute axonal injury. J Immunol. 2002;168:458–465. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead RJ, Neal JW, Griffiths MR, Linington C, Botto M, Lassmann H, Morgan BP. Deficiency of the complement regulator CD59a enhances disease severity, demyelination and axonal injury in murine acute experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Lab Invest. 2004;84:21–28. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan BP. Measurement of complement hemolytic activity, generation of complement-depleted sera, and production of hemolytic intermediates. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;150:61–71. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-056-X:61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller M, Wacker K, Ringelstein EB, Hickey WF, Imai Y, Kiefer R. Rapid response of identified resident endoneurial macrophages to nerve injury. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:2187–2197. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63070-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauta AJ, Roos A, Daha MR. A regulatory role for complement in innate immunity and autoimmunity. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2004;134:310–323. doi: 10.1159/000079261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hanlon GM, Humphreys PD, Goldman RS, Halstead SK, Bullens RW, Plomp JJ, Ushkaryov Y, Willison HJ. Calpain inhibitors protect against axonal degeneration in a model of anti-ganglioside antibody-mediated motor nerve terminal injury. Brain. 2003;126:2497–2509. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omura T, Omura K, Sano M, Sawada T, Hasegawa T, Nagano A. Spatiotemporal quantification of recruit and resident macrophages after crush nerve injury utilizing immunohistochemistry. Brain Res. 2005;1057:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos D, Pham-Dinh D, Reynolds R. Axon loss is responsible for chronic neurological deficit following inflammatory demyelination in the rat. Exp Neurol. 2006;197:373–385. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramón y Cajal S. Cajal's degeneration and regeneration of the nervous system. New York: Oxford UP; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Reichert F, Rotshenker S. Complement-receptor-3 and scavenger-receptor-AI/II mediated myelin phagocytosis in microglia and macrophages. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;12:65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0969-9961(02)00008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaepfer WW, Bunge RP. Effects of calcium ion concentration on the degeneration of amputated axons in tissue culture. J Cell Biol. 1973;59:456–470. doi: 10.1083/jcb.59.2.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dixhoorn MG, Timmerman JJ, Gijlswijk-Janssen DJ, Muizert Y, Verweij C, Discipio RG, Daha MR. Characterization of complement C6 deficiency in a PVG/c rat strain. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;109:387–396. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4551354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller A. Experiments on the section of glossopharyngeal and hypoglossal nerves of the frog and observations on the alterations produced thereby in the structure of their primitive fibers. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1850;140:423–429. [Google Scholar]