The greatest chance of vanquishing neurological disease lies not with what is on the bench, but with who is working at the bench. Although great discoveries are aided by technological advance, not a single great discovery was ever made by a technology. Discovery comes from a scientist testing a hypothesis, a keen mind poised at the edge of great leaps forward whose rigorous and sometimes innovative use or design of technology has been the window through which hypothesis has been transformed into insight. As I tell the University of Southern California (USC) Science, Technology, and Research (STAR) students, “If you want to change the world, become a scientist.” There is no lack of evidence for the power of scientific discovery as the catalyst that fuels advances in the human condition, economic prosperity, and societal evolution (Marburger, 2004; Friedman, 2007; National Academy of Sciences, 2007b). None of this happens without scientists, those individuals whose brains see beyond the unseen to what could be and who then begin the long, arduous, and exciting journey from hypothesis to discovery.

Although science is multifaceted, neuroscience is singularly notable as the discipline of discovering who we are—how we build our sense of self and world–synapse by synapse until we have built trillions of them encoding the details of our identity and the measure of our consciousness. It is also the scientific discipline challenged to illuminate the mysteries of autism, halt the disintegration of self by Alzheimer's, relieve the suffering of Parkinson's, unlock the chains of addictive disease, and restore sanity to those who are captive to the voices that haunt their neural circuits.

When one looks to the future for who will take on the mantel of discovery, there are precious few, and those few are dwindling at an ever greater rate. Over the past 30 years, the United States has seen a precipitous decline in the number of American students studying science and engineering (National Academy of Sciences, 2007a; National Science Foundation, 2007). In the 1970s, the U.S. ranked third, behind Japan and Finland, in the number of students studying science and engineering. Today it ranks 23rd (Dreifus, 2004). There is no better example of the disparity between the science success of the past and the bleak prospects for the future than California. California leads the world in the number of Nobel Laureates and high-tech companies but simultaneously ranks 49th out of 50 states on a nationwide exam of science literacy (Grigg et al., 2006).

Nearly two decades ago, along with high school science educator Dorothy Moote and Dr. Rosa Hernandez, then principal of Francisco Bravo Medical Magnet High School (Bravo) (when it was just trailers in a parking lot), I embarked on an experiment in science education: the USC STAR Program (http://pharmweb.usc.edu/USCSTAR/). For me, it was an opportunity to open the door of science to those who did not see themselves as future scientists but who, having once crossed the portal, found a world of discovery in which they conducted real science that mattered, and in the process came to see their potential to become a scientist. The STAR Program is part of a collaborative science education venture between the University of Southern California, Francisco Bravo Medical Magnet High School, El Sereno Middle School, Murchison Elementary School, and the National Science Foundation USC Biomimetic MicroElectronic Systems Engineering Research Center. Collectively, we impact the science literacy of 2000–3000 students each year. Expansion over the years has allowed us to build an integrated pipeline of science education beginning in elementary school, advancing to middle school and then high school and ultimately to college and postgraduate education. Our guiding hypothesis is that young learners can be excited by discovery and by the prospect of applying those discoveries to solve real world problems. We achieve our vision through eight programmatic domains that range from intensive one-on-one mentorship in scientific research in USC laboratories, to the implementation of problem-based science curricula in the classroom, to teacher education, to science fairs for the entire high school, to $100,000 in college scholarships yearly for STAR students, to supporting them in their pursuit of postgraduate education (http://pharmweb.usc.edu/USCSTAR).

We now have two decades of experience at the high school level, whereas our efforts at the elementary and middle school levels are relatively recent, dating back 4 years. Several key insights emerged over the 20 years of the STAR program. First, integrating science research experience into the 9 month high school curriculum has been key to success. The research experience becomes part of the student's curriculum, placing them in the laboratory for the entire afternoon each day for the duration of the academic year. Second, STAR students join a USC research team and conduct their own independent research as part of an existing hypothesis-driven project. Third, most STAR students extend their academic research experience through the STAR Summer Research Program, in which they conduct research 8 h per day, 5 d per week, for 6 weeks both in the summer before their senior year of high school and then directly after graduating from high school. Fourth, mentorship is critical, in particular, “experience-dependent mentorship.” The laboratory director is pivotal to the success of the experience, because the principal investigator sets the standard of research and engagement. In addition, college-bound STAR students mentor incoming STARs under the guidance of a graduate student or postdoctoral fellow. Graduate students and postdoctoral fellows are our primary mentors at the bench, where in turn they hone mentorship skills that will serve them when they develop their own research team. Undergraduate researchers in the laboratory also act as “next step” role models toward becoming a scientist. Through experience-dependent mentorship, each phase toward developing into a scientist is modeled. In turn, STAR students are highly effective mentors and role models for elementary and middle school students. Experience-dependent mentorship and next step role models have become cornerstones in the success of the STAR Program. Underpinning this whole process is the foundation of stable long-term financial support, which is vital to sustaining an educational intervention that requires decades of commitment.

Although we are several years away from determining ultimate success in building a pipeline of scientists, we have a substantial amount of data to determine whether the STAR Program high school research experience has been successful. Our partner high school, Francisco Bravo Medical Magnet High School, is located in one of the mid- to lower-performing nine local clusters with the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), which is the second largest school district in the nation. Demographically, STAR students, like their Bravo peers, tend to be those who face lower odds of science persistence by virtue of their socioeconomic and/or racial/ethnic background. Nearly 75% of STAR students receive federally subsidized lunches, and 76% come from homes in which English is not the primary language. Young women comprise 57% of the total STAR student population. STAR enrolls proportionately more Latinos than would be expected given their share of degrees in science and engineering fields; places more high school women in engineering labs than do most undergraduate or graduate engineering programs; and draws from a predominantly lower-income student population. In other words, many STAR students are those who are not expected to succeed in college, particularly in science and/or engineering. This has long been the target population of STAR: academically engaged students who must overcome considerable challenges to persist through the science pipeline.

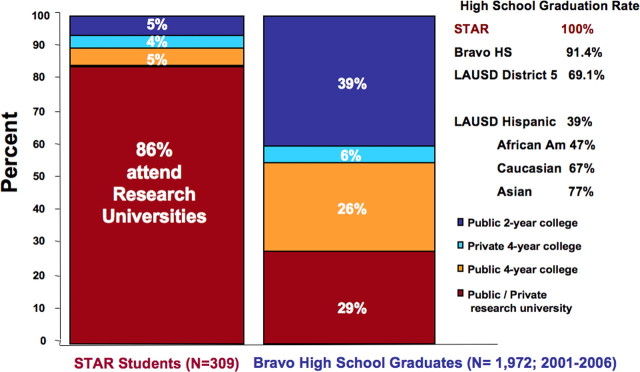

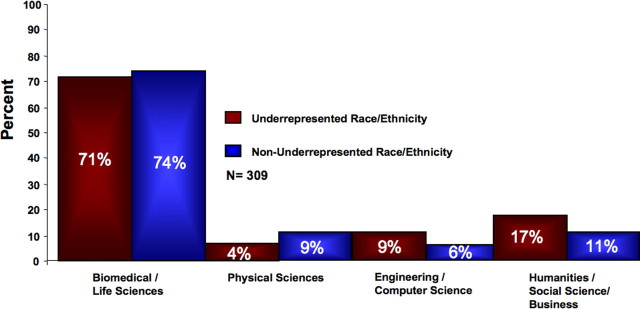

By the time STAR students graduate from high school, they are not only positioned to persist in science fields but also to succeed. STAR students graduate at the top of their class, their mean grade point average is significantly higher than their Bravo peers, 100% of STAR students attend college, and 85% (vs 29% of their peers) attend top-tier research institutions. Eighty-eight percent of STAR students declare majors in science and engineering fields; most major in the biological sciences (Fig. 1). Thus, the vast majority of STAR students stay in the science and engineering pipeline after high school graduation. Rates of college attendance and science majors are high regardless of ethnicity and gender (Fig. 2). STAR students from underrepresented racial/ethnic backgrounds attend research institutions and major in science and engineering at rates commensurate with students from represented backgrounds (Fig. 2). Collectively, the data indicate that the STAR Program is a critical conduit that begins with a high rate of participation among students who have been historically underrepresented in the pipeline, and keeps them in the pipeline—at the nation's top research universities.

Figure 1.

STAR Students attend top-tier research universities. STAR students attend public and private top-tier research universities at substantially higher rates than do their peers. Examples of those universities include USC; Caltech (Pasadena, CA); Stanford University (Stanford, CA); Columbia University (New York, NY); University of California, Los Angeles (Los Angeles, CA); University of California, Irvine (Irvine, CA); University of California, San Diego (La Jolla, CA); and Harvard University (Cambridge, MA). STAR students are included in Bravo data and thus contribute to the 29% of the general Bravo population matriculating to research universities. Conversely, STAR students attend public 2 year colleges at markedly lower rates than their Bravo peers. All STAR students matriculate into 4 year colleges and universities, whereas the data shown for Bravo are relevant to a subset of students who go on to postsecondary education. For the 5% of STAR students attending community college for the first 1–2 years, the vast majority do so for financial reasons, whereas others use this as a strategy to gain entry to their first-choice university.

Figure 2.

STAR students from ethnically underrepresented groups make the same academic choices as their represented counterparts. The majority of STAR students enroll at top-tier universities and colleges regardless of ethnicity. This is particularly important in California, where affirmative action has drastically diminished minority representation within the University of California system. STAR students predominantly choose biomedical and life sciences as their primary major, although there is a breadth of interest in the physical sciences and engineering. Eighty percent of STAR students continue to conduct research while they are undergraduates.

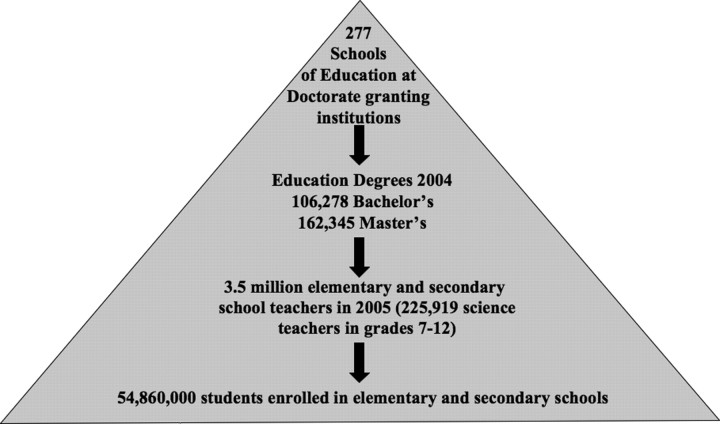

As successful as the STAR Program is at the local level, the enormity of the systemic problem is unlikely to be solved by individual scientists partnering with individual teachers and schools. Instead, successful local science education endeavors such as STAR demonstrate principles of effective science education that can and should be institutionalized on a broad scale. Approaching the science education challenge from a signaling amplification perspective, it is clear that the greatest impact can be achieved in the shortest amount of time by targeting the science, technology, engineering, and math curricula within schools of education (Fig. 3). Although there is a paucity of qualified teachers, particularly in urban schools, there is an even greater deficit in the number of qualified science and math teachers. Thus, targeting the source of teacher training (i.e., schools of education) is likely to yield the greatest impact in both the short and long term (Fig. 3). The key will be to integrate lessons from successful science education programs into the curriculum of teacher training and preparation within schools of education to change the education status quo and make a difference to the science pipeline on a national level. This will be particularly important for the education of elementary teachers, because this population can be particularly science averse, but who are key to instilling an enthusiasm for discovery and the fundamental knowledge required for later scientific development.

Figure 3.

Targeting Schools of Education to rapidly advance science competency of the greatest number of teachers and subsequently the greatest number of students. In the annual ranking of graduate programs, U.S. News and World Report listed 277 graduate programs in education at institutions that award doctoral degrees in education fields (U.S. News and World Report, 2006). Although there are many more institutions that award bachelor's and master's degrees in education [according to Snyder et al. (2006), a full 1002 postsecondary institutions in the U.S. award master's degrees in education, and 1170 award bachelor's degrees], we focused on those research-oriented, doctoral institutions where schools of education and teacher training programs could interact with major science and engineering research departments and centers. In 2005, there were 3.5 million elementary and secondary school teachers, of which 15% were science teachers (Snyder et al., 2006). In the aggregate, 3.5 million teachers impact 54.86 million learners. Thus, investing in the science and math literacy of faculty and students within schools of education has the potential to exponentially amplify the impact of science education outreach efforts by neuroscientists.

The Society for Neuroscience can be at the vanguard of a national effort to address the science education of educators. A three-step strategy to address the national challenge of science literacy could include the following: (1) create strategic alliances with national organizations charged with science literacy of educators to forge an initiative that targets science and math curricula within schools of education. Appropriate national organizations could include the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education, the United States Department of Education, the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education, the National Science Foundation Education, National Institutes of Health–National Center for Research Resources Science Education Partnership Awards, foundations dedicated to innovation in science education such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, an alliance of scientific societies (e.g., Society for Neuroscience, FASEB, American Chemical Society), and the National Academies of Science and Engineering. (2) Create a grant program with national agencies to support proofs of concept for science and math education involving neuroscientists and faculty within schools of education. Partnership schools would meet criteria for ability to influence schools of education across the nation and for capability to assess impact both within their own institution and the schools where their graduates are employed as teachers. Initially, a curriculum centered on neuroscience, and in particular learning and memory, could serve as proof of concept. Although the topic is of particular relevance to education, neuroscience also provides an umbrella under which many state science standards can be taught. (3) In collaboration with national agencies and foundations, creating a national scholarship program to support undergraduates and graduate students in the life, physical, social, engineering, and environmental sciences to enter the teaching profession. Partnering with schools of education will require a new paradigm of engagement in which scientists build alliances with education faculty to create the next generation of educators who understand both science and their pivotal role in inspiring generations of learners to take up the mantel of discovery.

Footnotes

Editor's Note: In 2003, the Society for Neuroscience initiated the Science Educator Award to recognize an outstanding neuroscientist who has made significant contributions to the education of the public. For a description of the award, see http://www.sfn.org/sea. Previous awardees are Eric Chudler, PhD (2003), Rochelle Schwartz-Bloom (2004), and Colin Blakemore (2005). The Journal asked the 2006 winner, Roberta Diaz Brinton, to give us her views on neuroscience education.

The science education efforts summarized herein are the result of a long-standing collaboration with STAR Program/Bravo High School Science educators Dorothy Moote, Kathleen O'Neill, Sharon Stewart, and Joseph Cocozza, as well as Francisco Bravo Medical Magnet Principals Rosa Hernandez and Maria Torres Flores. Sustained support for the STAR Program from the USC Neighborhood Outreach Program, the Kenneth T. and Eileen L. Norris Foundation, the College Access Foundation of California (to R.D.B.), and the National Science Foundation USC Biomimetic Microelectronic Systems Engineering Research Center (to M. Humayun) is most gratefully acknowledged. STAR Program assessment was conducted by Dr. Shannon Gilmartin of SKG Analysis and is gratefully acknowledged. As the recipient of the 2006 Society for Neuroscience Science Educator Award, I am honored by the recognition and the opportunity to stand with the many dedicated neuroscientists who are building our legacy.

References

- Dreifus C. A conversation with: Robert C. Richardson; The chilling of american science. The New York Times. 2004. Jul 6,

- Friedman T. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2007. The world is flat 3.0: a brief history of the twenty-first century. [Google Scholar]

- Grigg WS, Lauko MA, Brockway DM. The nation's report card: science 2005. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Marburger J., III . Washington, DC: National Science and Technology Council; 2004. Science for the 21st century. [Google Scholar]

- National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, Institute of Medicine Committee on Prospering in the Global Economy of the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies; 2007a. Rising above the gathering storm: energizing and employing America for a brighter economic future. [Google Scholar]

- National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, Institute of Medicine Committee on Prospering in the Global Economy of the 21st Century. Rising above the gathering storm: energizing and employing America for a brighter economic future. Washington, DC: The National Academies; 2007b. What might life in the United States be like if it is not competitive in science and technology? pp. 204–224. [Google Scholar]

- National Science Foundation, Division of Science Resources Statistics. Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation; 2007. Women, minorities, and persons with disabilities in science and engineering: 2007 (NSF 07-315) [Google Scholar]

- Snyder TD, Tan AG, Hoffman CM. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2006. Digest of education statistics 2005 (NCES 2006-030) [Google Scholar]

- U.S. News and World Report. America's best graduate schools 2008: teacher preparation at top education schools. 2008.