Abstract

T-type Ca2+ channels (T-channels) are involved in the control of neuronal excitability and their gating can be modulated by a variety of redox agents. Ascorbate is an endogenous redox agent that can function as both an anti- and pro-oxidant. Here, we show that ascorbate selectively inhibits native Cav3.2 T-channels in peripheral and central neurons, as well as recombinant Cav3.2 channels heterologously expressed in human embryonic kidney 293 cells, by initiating the metal-catalyzed oxidation of a specific, metal-binding histidine residue in domain 1 of the channel. Our biophysical experiments indicate that ascorbate reduces the availability of Cav3.2 channels over a wide range of membrane potentials, and inhibits Cav3.2-dependent low-threshold-Ca2+ spikes as well as burst-firing in reticular thalamic neurons at physiologically relevant concentrations. This study represents the first mechanistic demonstration of ion channel modulation by ascorbate, and suggests that ascorbate may function as an endogenous modulator of neuronal excitability.

Keywords: ascorbic, calcium current, dorsal root ganglion, DRG, low-threshold calcium channel, oxidation, thalamus

Introduction

Ascorbate (ascorbic acid, vitamin C) is a ubiquitous redox agent present at particularly high concentrations in neurons (Rice, 2000), but its interaction with the ion channels that control neuronal excitability is poorly understood. We have shown previously that T-type Ca2+ channels (T-channels) can be modulated by a variety of redox agents (Todorovic et al., 2001; Nelson et al., 2005; Joksovic et al., 2006); thus, we reasoned that ascorbate might also affect the gating of these channels. Ascorbate often functions as an antioxidant, readily scavenging reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. However, ascorbate can also function as a pro-oxidant by catalyzing the formation of several reactive oxygen species (ROS). Ascorbate generates ROS by reducing transition metals by a one-electron transfer mechanism, and oxygen by a two-electron transfer mechanism; the products of these reactions can subsequently interact to create several powerful ROS including hydroxyl radicals (·OH) (Stadtman, 1991). Collectively, this process is termed metal-catalyzed oxidation (MCO) (Stadtman, 1991; Stadtman, 1993). A unique feature of proteinaceous MCO is that only one or at most a select number of amino acids are modified. This site specificity has been attributed to the formation of ROS directly at metal binding sites, where they attack the functional groups of nearby residues. Histidine residues are particularly prone to MCO, in part because they are often structural components of metal binding sites (Stadtman, 1993). Here we present evidence that ascorbate inhibits Cav3.2, but not Cav3.1 or Cav3.3 T-channels by initiating the MCO of a unique, metal-binding histidine residue in domain 1 of the channel. Because Cav3.2 channels play an important role in tuning the excitability of several neuronal populations (White et al., 1989; Nelson et al., 2005; Vitko et al., 2005; Joksovic et al., 2006), ascorbate may function as an endogenous modulator of neuronal firing under physiological or pathological conditions.

Materials and Methods

DRG and thalamic neurons.

Acutely dissociated dorsal root ganglion (DRG) cells were prepared from adolescent rats as described previously (Nelson et al., 2005). For recording, cells were plated onto uncoated glass coverslips, placed in a culture dish, and perfused with external solution. Thalamic slices were prepared from adolescent rats as previously described (Joksovic et al., 2006). For recording, slices were placed in a recording chamber and perfused with external solution. All experiments were performed at room temperature.

HEK293 cells.

Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells were grown in DMEM/F12 media (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with fetal calf serum (10%), penicillin G (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (0.1 mg/ml). Cav3.1 (Perez-Reyes et al., 1998), human Cav3.2 (Vitko et al., 2005), Cav3.3 (Lee et al., 1999b), and GGHH (Welsby et al., 2003) plasmids were as described previously. HHGG, GHGG, HGGG, Cav3.2(H191Q), and Cav3.1(Q172H) plasmids were constructed as described previously (Kang et al., 2006) and subcloned into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen). To construct the Cav3.2(H191C) plasmid, a human Cav3.2 cDNA (GenBank accession number AF051946) contained in pcDNA3 was mutated using oligonucleotide primers and a QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, LA Jolla, CA). The primers were obtained from Operon (Alameda, CA) and used without purification. The full-length cDNA was reassembled using a fragment of the mutated clone. The sequence corresponding to this fragment, as well as the flanking regions, was verified by automated sequencing. The full-length rat Cav3.2 cDNA was generated by full-length RT-PCR using total RNA isolated from adult rat thalamic tissue and oligonucleotides 5′-GATAAGCTTATGACCGAGGGCACG-3′ and 5′-CGCTCTAGACTACACAGGCTCATC-3′. The resulting ∼7 kb PCR products were subcloned into pGEM T-Easy vector and then into pCNA 3.1 zeo(+) (Invitrogen). The full-length thalamic cDNA was confirmed by DNA sequencing and compared with the reported PubMed sequences for Cav3.2 cDNAs from multiple organisms as well as the rat Cav3.2 genomic DNA sequence. The His 191 residue examined in the present study is conserved across the Cav3.2 T-type channels in all species in the database including chicken, dog, mouse, rat and human. Cells were transiently cotransfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) at a 10:1 molar ratio with a plasmid encoding CD8 antigen and incubated with polystyrene microbeads coated with antiCD8 antibody (Invitrogen). After 48 h, cells with bound microbeads were selected for recording.

Electrophysiology.

Recording electrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass microcapillary tubes (Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA), and had resistances from 1 to 4 MΩ when filled with internal solution. Recordings were made using an Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier (Molecular Devices, Foster City, CA). Digitization of membrane voltages and currents were controlled using a Digidata 1322A interfaced with Clampex 8.2 (Molecular Devices). We analyzed data using Clampfit 8.2 (Molecular Devices) and Origin 7.0 (Microcal Software, Northampton, MA). Currents were low-pass filtered at 2–5 kHz. Series resistance and capacitance values were taken directly from readings of the amplifier after electronic subtraction of the capacitive transients. Series resistance was compensated to the maximum extent possible (usually 50–80%). Multiple independently controlled glass syringes served as reservoirs for a gravity-driven perfusion system. The external solution for DRG and HEK293 cell experiments contained (in mm) 152 tetraethylammonium (TEA)-Cl, 10 BaCl2, and 10 HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.4 with TEA-OH. The external solution for thalamic slice experiments contained (in mm) 130 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 2.5 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, and 0.001 TTX, equilibrated with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2. In some experiments, TTX was omitted to study burst firing of nucleus reticularis thalami (nRT) neurons. The internal solution for voltage-clamp experiments with DRG neurons and thalamic slices contained (in mm) 135 tetramethylammonium-OH, 40 HEPES, 10 EGTA, and 2 MgCl2, adjusted to pH 7.2 with hydrofluoric acid. The internal solution for voltage-clamp experiments with HEK293 cells contained (in mm) 110 Cs-MeSO4, 14 Cr-PO4, 10 HEPES, 9 EGTA, 5 Mg-ATP, and 0.3 Tris-GTP, adjusted to pH 7.3 with CsOH. The internal solution for current-clamp experiments with thalamic slices contained (in mm) 130 KCl, 40 HEPES, 5 MgCl2, 2 MgATP, 1 EGTA, 0.1 Na3GTP, adjusted to pH 7.3 with KOH.

Analysis.

Statistical comparisons were made using paired or unpaired t tests or Mann–Whitney U tests where appropriate. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM and p values are reported only when statistically significant (<0.05). The percentage reductions in peak current at various ascorbate and Cu2+ concentrations were used to generate concentration–response curves. Mean values were fit to the following Hill–Langmuir function:

where PBmax is the maximal percentage inhibition of peak current, IC50 is the concentration that produces 50% inhibition, and h is the apparent Hill–Langmuir coefficient for inhibition. The fitted values are reported with >95% linear confidence limits. The voltage dependencies of activation and steady-state inactivation were described with single Boltzmann distributions of the following forms:

where Imax is the maximal activatable current, V50 is the voltage where half the current is activated or inactivated, and k is the voltage dependence (slope) of the distribution.

Results

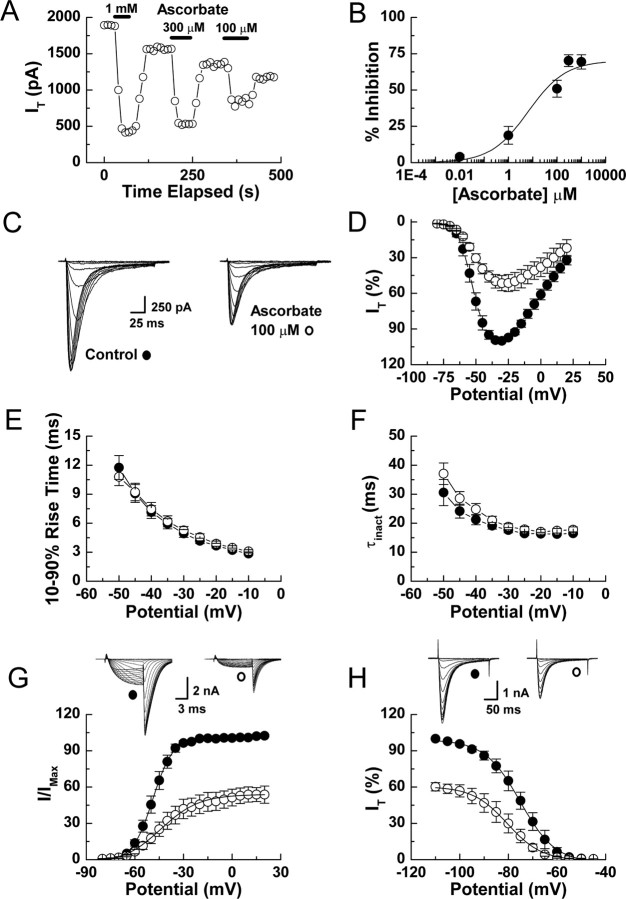

We used whole-cell patch-clamp recordings to determine the effects of ascorbate on voltage-gated Ca2+ currents present in acutely dissociated DRG neurons. Ascorbate rapidly inhibited T-currents (Fig. 1A), but had no effect on high-voltage-activated Ca2+ currents even at 50-fold higher concentrations (data not shown). T-current inhibition was dose-dependent and partial with an effective concentration (IC50) of 6.5 μm and a maximal reduction in peak current of 70% (Fig. 1B). The inhibition induced by brief exposure to ascorbate was partially reversible after washout, with ∼75–90% recovery occurring after exposures of less than a minute; the effects of prolonged exposures were significantly less reversible (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Ascorbate inhibition of rat DRG T-currents. A, Time course showing the effects of various ascorbate concentrations on T-currents from an acutely dissociated DRG neuron. T-currents were evoked by 175 ms steps from −90 to −40 mV every 10 s. B, Concentration–response curve for inhibition of DRG T-currents by ascorbate. Average data were fit with Equation 1 to generate the curve: IC50, 6.5 ± 3.9 μm; h, 0.56 ± 0.12; maximal inhibition, 70.2 ± 2.1%; (n = 4–9). C, T-currents evoked from a DRG neuron by steps from −90 to −80 through −20 mV (Δ5 mV), before and during exposure to ascorbate. D, Averaged effects of ascorbate on DRG T-currents evoked by steps from −90 mV to the indicated test potentials (n = 8). E, Averaged effects of ascorbate on the kinetics of DRG T-current activation calculated as 10–90% rise time from IV data (n = 8). F, Averaged effects of ascorbate on the kinetics of DRG T-current inactivation calculated from single exponential fits of IV data (n = 8). G, Raw traces and average effects of ascorbate on voltage-dependent activation of DRG T-currents: control, V50, −49.0 ± 0.3; k, 6.2 ± 0.2; ascorbate, V50 −44.1 ± 0.9; k, 11.9 ± 0.8 (n = 6). Data were calculated from isochronal tail currents evoked by 10 ms steps from −90 to −80 through 20 mV (Δ5 mV), where the amplitude of the tail current is a measure of the conductance activated during the preceding pulse. Average data were fit with Equation 2 to generate curves. H, Raw traces and average effects of ascorbate on steady-state inactivation of DRG T-currents: control, V50, −75.0 ± 0.3; k, 7.3 ± 0.3; ascorbate, V50, −80.4 ± 0.4; k, 7.1 ± 0.4 (n = 6). Currents were recorded at −30 mV after prepulses lasting 3.5 s to potentials from −110 to −45 mV. Average data were fit with Equation 3 to generate curves.

To assess the effects of ascorbate on the biophysical properties of DRG T-currents, we measured current–voltage (I–V) relationships in the presence and absence of ascorbate (Fig. 1C,D). Ascorbate significantly reduced T-currents at all potentials between −70 and 20 mV, but had no significant effect on the kinetics of current activation or inactivation (Fig. 1E,F). Ascorbate did induce a 5 mV rightward shift in half-maximal activation (V50) with a decrease in voltage dependence, as well as a 5 mV leftward shift in the V50 of inactivation, but without an effect on voltage dependence (Fig. 1G,H).

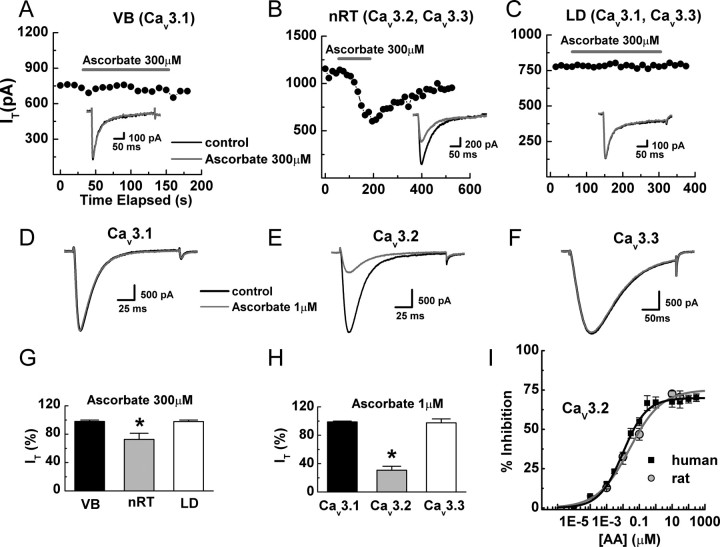

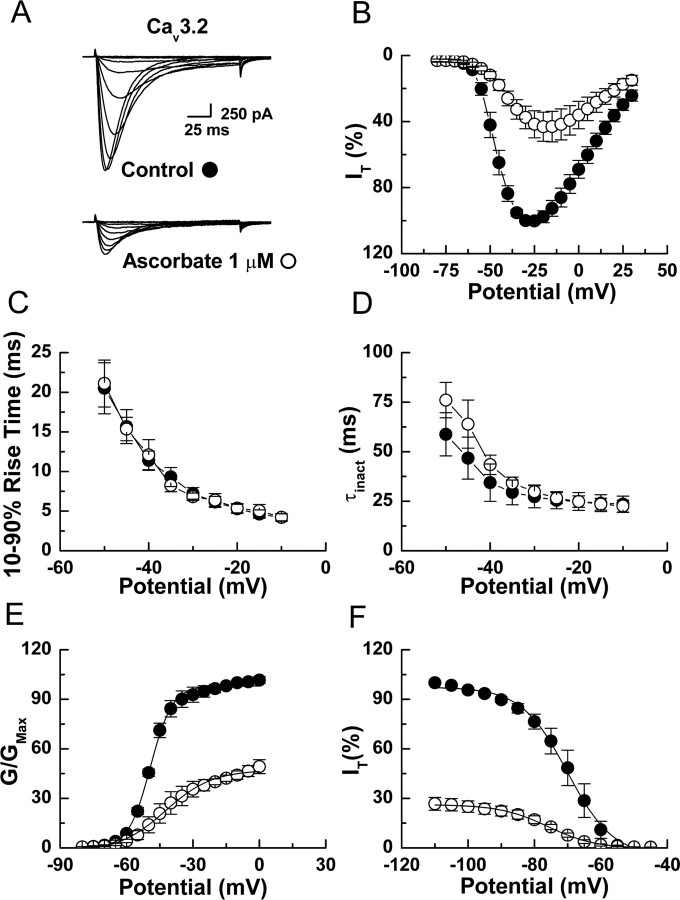

Cav3.2 is overwhelmingly the predominant T-channel isoform expressed in DRG neurons (Talley et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2003). Therefore we also examined the effects of ascorbate on intact neurons in brain slices of thalamic nuclei known to express diverse T-channels (Talley et al., 1999; Joksovic et al., 2006). Ascorbate significantly inhibited T-currents from reticular (nRT, Cav3.2 and Cav3.3), but not ventrobasal (VB, Cav3.1) or laterodorsal (LD, Cav3.1 and Cav3.3) thalamic neurons, suggesting selective inhibition of Cav3.2 (Fig. 2A–C,G). We confirmed this using both recombinant human and rat T-channels heterologously expressed in HEK293 cells. Ascorbate significantly inhibited Cav3.2 currents, but had no effect on either Cav3.1 or Cav3.3 currents even at a 1000-fold higher concentration (Fig. 2D–F,H,I). Additionally, ascorbate induced gating shifts in recombinant human Cav3.2 currents (Fig. 3) that were nearly identical to those observed in native rat DRG neurons (Fig. 1).

Figure 2.

Ascorbate inhibits Cav3.2, but not Cav3.1 or Cav3.3 T-currents in both native thalamic and recombinant HEK293 cells. A–C, Time courses and raw traces showing the differential effects of ascorbate on T-currents from representative nRT, LD, and VB thalamic neurons. D–F, Raw traces showing the differential effects of ascorbate on T-currents from recombinant Cav3.1, Cav3.2, and Cav3.3 channels expressed in HEK293 cells. G, Averaged effects of ascorbate on T-currents in thalamic nuclei expressed as a percentage of control: nRT, 72.6 ± 2.9%; p < 0.01; LD, 97.8 ± 1.4%; VB, 98.0 ± 1.6% (n = 3–9). H, Averaged effects of ascorbate on recombinant T-currents expressed as a percentage of control: Cav3.1, 98.8 ± 1.1%; Cav3.2, 30.7 ± 5.5%; p < 0.01; Cav3.3, 97.4 ± 5.6% (n = 5–8). I, Concentration–response curve for inhibition of recombinant Cav3.2 currents by ascorbate. Average data were fit with Equation 1 to generate the curve: IC50, 9.75 ± 0.01 nm; h, 0.60 ± 0.05; maximal inhibition, 69.9 ± 1.2% (n = 4–7) for the human clone and IC50, 25.10 ± 0.01 nm; h, 0.45 ± 0.08; maximal inhibition, 75.1 ± 4.0% (n = 4–7) for the rat clone. *p < 0.01.

Figure 3.

Ascorbate inhibition of recombinant Cav3.2 T-currents in HEK293 cells. A, Currents evoked from an HEK293 cell expressing human Cav3.2 by steps from −90 to −80 through −25 mV (Δ5 mV), before and during exposure to ascorbate. B, Averaged effects of ascorbate on Cav3.2 currents evoked by steps from −90 to −80 through 25 mV (n = 8). C, Averaged effects of ascorbate on the kinetics of Cav3.2 current activation calculated as 10–90% rise time from IV data (n = 8). D, Averaged effects of ascorbate on the kinetics of Cav3.2 current inactivation calculated from single exponential fits of IV data (n = 8). E, Average effects of ascorbate on voltage-dependent activation of Cav3.2 current: control, V50, −49.3 ± 0.3; k, 5.0 ± 0.3; ascorbate, V50, −42.5 ± 1.2; k, 10.6 ± 1.3 (n = 4). Data were calculated from isochronal tail currents evoked by 10 ms steps from −90 to −80 through 0 mV (Δ5 mV), where the amplitude of the tail current is a measure of the conductance activated during the preceding pulse. Average data were fit with Equation 2 to generate curves. F, Average effects of ascorbate on steady-state inactivation of Cav3.2 current: control, V50, −70.0 ± 0.4; k, 6.9 ± 0.4; ascorbate, V50, −76.0 ± 0.4; k, 7.2 ± 1.6 (n = 5). Currents were recorded at −30 mV after prepulses lasting 3.5 s to potentials from −110 to −45 mV. Average data were fit with Equation 3 to generate curves.

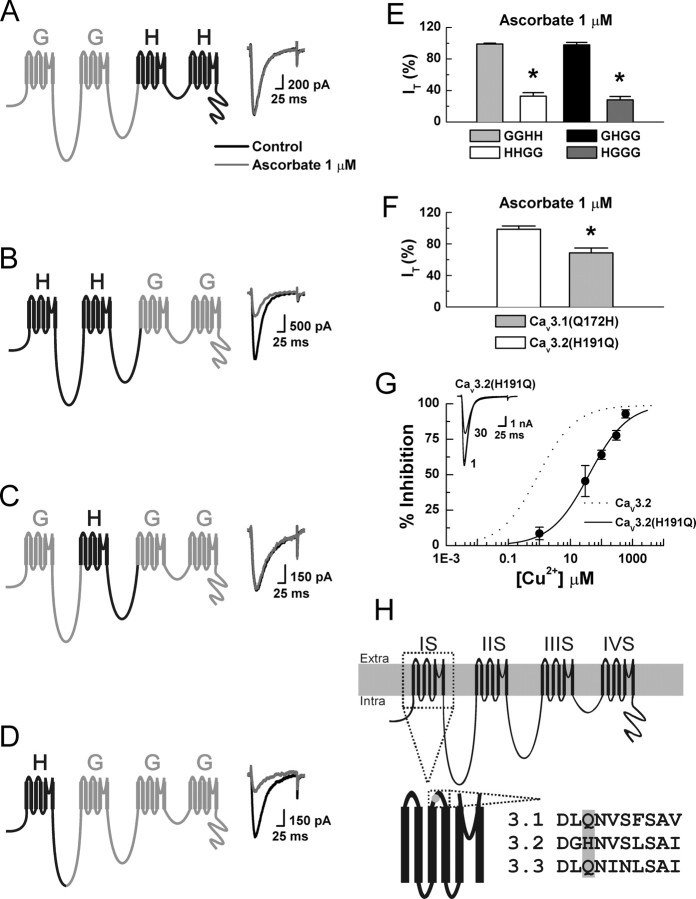

To determine the molecular substrate for ascorbate inhibition of Cav3.2, we constructed chimeras between Cav3.1 (α1G, insensitive) and Cav3.2 (α1H, sensitive) and screened for sensitivity to ascorbate. The chimeras were named using letters to represent the α-subunit donor for each of the four channel domains (Fig. 4). GGHH currents were insensitive to ascorbate, whereas HHGG currents were sensitive, indicating that critical residues are located within domains 1 or 2 of Cav3.2 (Fig. 4A,B,E). We then constructed two single-domain chimeras, exchanging either domain 1 or 2. GHGG currents were insensitive to ascorbate whereas HGGG currents were sensitive. Thus, domain 1 of Cav3.2 is required for ascorbate inhibition (Fig. 4C–E).

Figure 4.

H191 is required for the ascorbate sensitivity of Cav3.2. A–D, Currents were evoked from HEK293 cells expressing the indicated constructs by steps from −90 to −30 mV, before and during exposure to ascorbate. E, Average effects of ascorbate on the indicated constructs expressed as a percentage of control: GGHH, 99.1 ± 1.1%; HHGG, 32.7 ± 4.7%, p < 0.01; GHGG, 97.9 ± 3.1%; HGGG, 28.2 ± 4.1%, p < 0.01 (n = 5–9). F, Average effects of ascorbate on the indicated constructs expressed as % of control: Cav3.2(H191Q), 98.7 ± 4.1%; Cav3.1(Q172H), 72.6 ± 6.1%, p < 0.01 (n = 6–8). G, Raw traces and concentration–response curve for inhibition of human Cav3.2(H191Q) by Cu2+. Average data were fit with Equation 1 to generate the curve: IC50, 39.7 ± 6.4 μm; h, 0.70 ± 0.08 (n = 4–6). The dotted line represents Cav3.2 data recorded under nearly identical conditions (HEK293 cells, 10 mm Ba2+) (Jeong et al., 2003). H, Schematic diagram of Cav3.2 showing the position of H191 in the extracellular loop between transmembrane segments 3 and 4 of domain 1, as well as the amino acid sequence of the loop across T-channels. *p < 0.01.

Notably, ascorbate inhibition of the chimeras mirrors their reported inhibition by Ni2+ (Kang et al., 2006). This is of interest because similar to ascorbate, Ni2+ is one of the few agents capable of discriminating among T-channel isoforms, as Cav3.2 is ∼20-fold more sensitive than Cav3.1 or Cav3.3 (Lee et al., 1999a; Jeong et al., 2003; Kang et al., 2006). Furthermore, mutation of a single extracellular histidine (H) residue to glutamine (Q) at position 191 (H191Q) greatly reduces the Ni2+ sensitivity of Cav3.2, indicating that H191 is part of a high-affinity Ni2+ binding site (Kang et al., 2006). Based on these observations and studies demonstrating that ascorbate-induced MCO can selectively modify histidine residues at metal-binding sites (Uchida and Kawakishi, 1990; Stadtman, 1993; Zhao et al., 1997; Hovorka et al., 2002), we hypothesized that H191 is also important for ascorbate inhibition of Cav3.2. Consistent with this, the effects of ascorbate were completely abolished in Cav3.2(H191Q) (Fig. 4F). The biophysical parameters of Cav3.2(H191Q) currents were similar to Cav3.2, but were unaffected by ascorbate, indicating the mutation disrupted ascorbate sensitivity, but not basic channel gating (data not shown). We next attempted to confer ascorbate sensitivity to Cav3.1 by performing the analogous reverse mutation (Q172H). Figure 4F shows that Cav3.1(Q172H) currents were significantly inhibited by ascorbate, confirming the requirement of H191 for sensitivity.

Similar to Ni2+, Cav3.2 is significantly more sensitive to inhibition by other divalent transition metals such as Cu2+ and Zn2+ than Cav3.1 or Cav3.3 (Jeong et al., 2003; Traboulsie et al., 2007). Hence, H191 may not be a Ni2+-exclusive binding site, and may also be critical for high-affinity Cu2+ and Zn2+ binding. Because highly redox reactive metals such as Cu2+ and Fe3+ are much more likely to play a role in MCO than relatively redox inactive metals such as Ni2+ or Zn2+ (Stadtman, 1991, 1993), we examined whether the Cu2+ sensitivity of Cav3.2 is also disrupted by the H191Q mutation. As shown in Figure 4G, Cav3.2(H191Q) was >40-fold less sensitive to Cu2+ than Cav3.2, supporting the hypothesis that H191 is part of a general high-affinity metal binding site located on the external surface of Cav3.2.

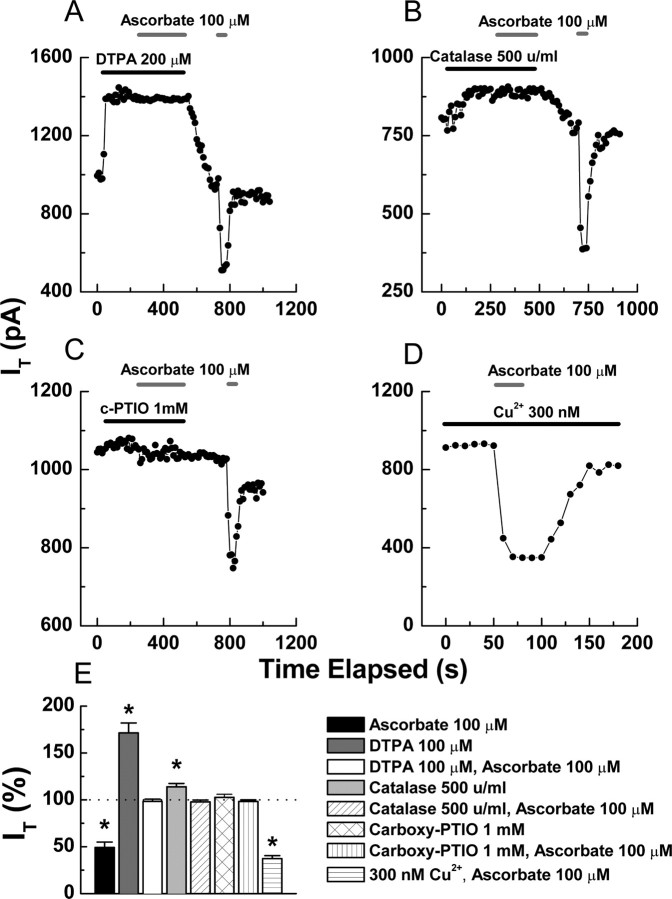

Ascorbate generates ROS through reactions that depend on transition metals. A point that has been repeatedly demonstrated by the use of metal chelators; in particular, ascorbate inhibition of T-currents in pancreatic β cells is completely abolished by previous application of the chelator diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) (Parsey and Matteson, 1993). Of note, DTPA results in a large increase in baseline T-currents, indicating that channels are subject to tonic inhibition by trace metals (Parsey and Matteson, 1993). Similarly, we found that DTPA significantly enhanced T-currents in DRG neurons, and completely occluded the effects of subsequently applied ascorbate (Fig. 5A,E). In addition to chelators, previous studies in other systems have implicated MCO as a mechanism for the effects of ascorbate by showing that catalase, which decomposes hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and thus prevents formation of ROS via MCO, protects against ascorbate (Uchida and Kawakishi, 1990; Zhao et al., 1997; Hovorka et al., 2002). We found that catalase completely prevented the inhibition of DRG T-currents by ascorbate (Fig. 5B,E), as did high concentrations of the ROS scavenger 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide (c-PTIO) (Fig. 5C,E). These results, in combination with our mutational studies, suggest that ascorbate likely modulates Cav3.2 via MCO.

Figure 5.

MCO underlies the effects of ascorbate on Cav3.2. A–C, Application of DTPA (A), catalase (B), and c-PTIO (C) occludes inhibition of T-currents by ascorbate in 3 representative DRG neurons. D, Representative time course from a DRG neuron showing that the inhibition by ascorbate is increased by the addition of 300 nm Cu2+ to the external solution. E, Averaged effects of the indicated agents on DRG T-currents expressed as a percentage of control: ascorbate, 49.2 ± 5.8, p < 0.01 (from Fig. 1B); DTPA, 171.4 ± 10.6, p < 0.01; DTPA and ascorbate, 98.4 ± 2.3; catalase, 113.8 ± 3.7, p < 0.01; catalase and ascorbate, 97.7 ± 2.1; c-PTIO, 102.6 ± 3.2; c-PTIO and ascorbate, 98.3 ± 1.6; 300 nm Cu2+ and ascorbate, 37.3 ± 4.2, p < 0.01 (n = 5–12). For these experiments, the steady-state effect of the first agent was considered a new baseline to calculate the subsequent inhibition by ascorbate. *p < 0.01.

In general, electrophysiological solutions contain several trace metal contaminants, with Zn2+ predominating (Li et al., 1996; Paoletti et al., 1997; Thio and Zhang, 2006). This implies that the observed increase in Cav3.2 currents after the addition of DTPA largely results from relief of tonic Zn2+ inhibition. This is interesting because Zn2+ is relatively redox inactive and does not readily participate in MCO; in fact, total replacement of Cu2+ with Zn2+ can protect against MCO in some systems (Chevion, 1988). However, histidine residues have significantly higher affinity for Cu2+ than Zn2+ (Sundberg and Martin, 1974), thus many Zn2+–binding proteins are nonetheless susceptible to modification by MCO in the presence of even trace amounts of Cu2+. This was specifically demonstrated by Hovorka et al. (2002), who showed that Zn2+-insulin was less susceptible to MCO as the Cu2+/Zn2+ ratio was decreased from 1:1 to 1:10, but that even a 1:1000 ratio was unable to protect against ascorbate completely. Along these lines, we found that increasing the Cu2+/Zn2+ ratio in our extracellular solution by adding 300 nm Cu2+, resulted in a significant increase (12%) in the inhibition produced by ascorbate (Fig. 5D,E).

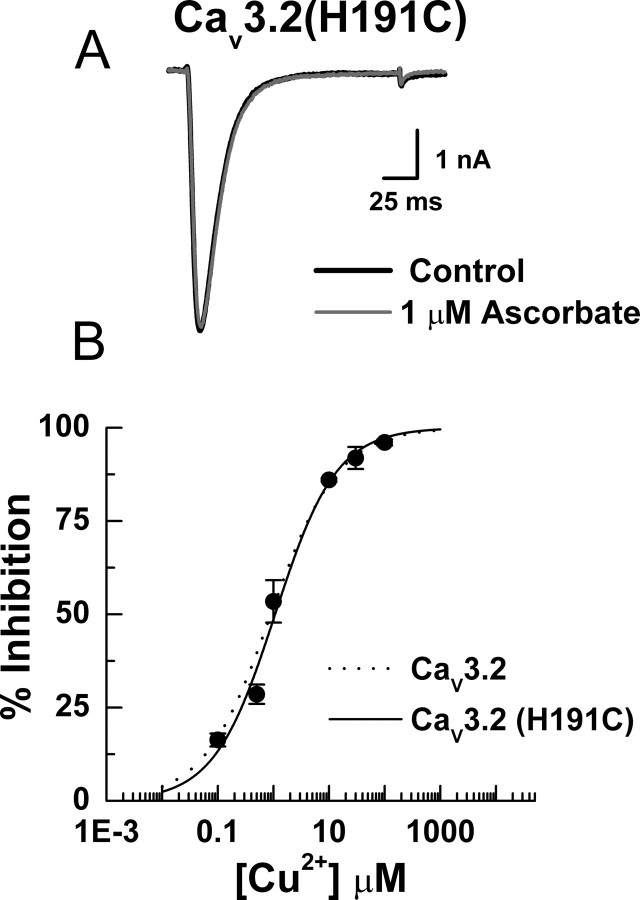

Collectively, our data indicate that H191 is a critical component of a high-affinity metal binding site located on the external surface of Cav3.2, and that ascorbate inhibits Cav3.2 via interaction with trace metal contaminants bound at this site, likely resulting in MCO. It is less clear which specific amino acid(s) are modified. H191 may be the residue modified by ROS, but because the affinity of metals for any single amino acid is relatively low, H191 is more likely only one part of a multiresidue binding site. Thus, it is possible that the ascorbate insensitivity of Cav3.2(H191Q) results solely from the disruption of metal binding, which prevents subsequent MCO of a neighboring residue in the binding site. To investigate this, we made another point mutation, Cav3.2(H191C), because cysteine residues have metal binding abilities comparable to histidines, but are less sensitive to MCO. Figure 6 shows that Cav3.2(H191C) channels were ascorbate-insensitive, but highly Cu2+-sensitive, strongly suggesting that the effects of ascorbate on Cav3.2 are the result of the MCO of H191 and not a neighboring residue.

Figure 6.

Cav3.2(H191C) is ascorbate-insensitive, but Cu2+-sensitive. A, Raw traces showing the lack of ascorbate effect on Cav3.2(H191C) currents in an HEK293 cell. Similar results were obtained in experiments from five additional cells (peak current in the presence of ascorbate was 96.2 ± 1.2% of control). B, Concentration–response curve for inhibition of Cav3.2(H191C) by Cu2+. Average data were fit with Equation 1 to generate the curve: IC50, 1.07 ± 0.16 μm; h, 0.79 ± 0.09 (n = 4–7). The dotted line represents Cav3.2 data recorded under nearly identical conditions (HEK293 cells, 10 mm Ba2+) (Jeong et al., 2003).

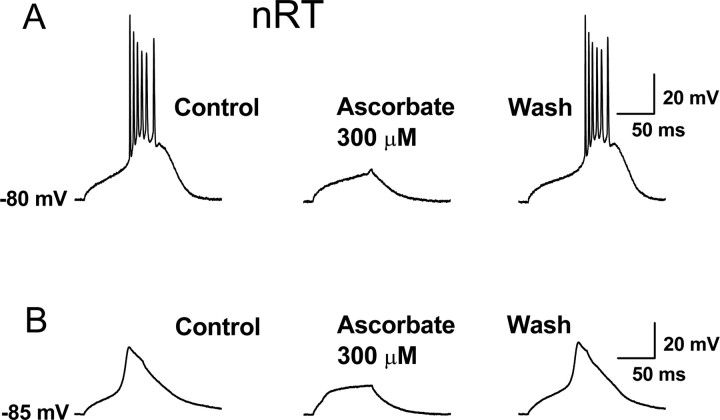

Last, we examined the ability of ascorbate to modulate Cav3.2-dependent neuronal excitability in nRT neurons in intact brain slices. The ability of thalamic neurons to fire low-threshold Ca2+ spikes (LTSs) is dependent on T-currents and contributes to the ability of these neurons to fire bursts of action potentials (APs) in response to small membrane depolarizations such as those caused by excitatory postsynaptic potentials (Perez-Reyes, 2003). As shown in Figure 7, application of ascorbate at physiologically relevant concentrations (Rice, 2000) reversibly inhibited both the isolated LTSs as well as burst-firing in current-clamp recordings from nRT neurons, suggesting that ascorbate may function as an endogenous modulator of nRT excitability.

Figure 7.

Ascorbate inhibition of LTSs and burst firing in nRT neurons. A, Representative current-clamp trace from an nRT neuron (the LTS was evoked by a 250 ms, 100 pA current injection at the indicated membrane potential). Application of ascorbate reversibly reduced the amplitude of the LTS and abolished the resulting burst of APs. In similar experiments from five cells, ascorbate reduced the average number of APs crowning the LTS from 4.6 ± 0.7 to 2.4 ± 1.1 (p < 0.01). B, Ascorbate reversibly inhibited the isolated LTS in another nRT neuron. The protocol was similar to that in A, but with the addition of 1 μm TTX to block APs. In similar experiments from six cells, ascorbate reduced the amplitude of the LTS by 44.6 ± 11.4% (p < 0.01).

Discussion

Our results demonstrate the remarkably specific inhibition of Cav3.2 channels by ascorbate. Indeed, ascorbate is the most selective agent capable of discriminating among T-channel isoforms yet described. Thus, ascorbate may be a useful pharmacological tool for identifying the contribution of Cav3.2 current to total Ca2+ current, as well as to cellular excitability.

Additionally, our findings suggest that MCO is the likely molecular mechanism for inhibition of Cav3.2 channels by ascorbate. Several reaction products can result from the MCO of histidine, but the most common is 2-oxo-histidine, which is created by oxidation at the C-2 position of histidine's imidazole ring (Uchida and Kawakishi, 1990; Stadtman, 1993; Schoneich, 2006). The formation of 2-oxo-histidine has been demonstrated in small peptides in vitro and in vivo using high-resolution mass spectrometry (Schoneich, 2006). However, current technology is limited to small peptides and is unable to detect such small covalent modifications in larger proteins such as Ca2+ channels. Despite being unable to demonstrate the precise reaction product, our data collectively implicate MCO as the mechanism underlying the effects of ascorbate on Cav3.2.

One particularly interesting observation of this study was the significantly increased inhibitory potency of ascorbate against both recombinant human and rat Cav3.2 channels compared with native rat Cav3.2 channels. This discrepancy may be attributable to the interaction of native Cav3.2 channels with accessory subunits or other regulatory proteins, or the presence of endogenous redox buffers that are absent or altered in heterologous systems.

Another intriguing aspect of our findings concerns the observation that the effects of brief applications of ascorbate are at least partially reversible, which is interesting given the fact that MCO is a covalent modification. However, there are numerous biological examples of reversible covalent modification serving as a mechanism for the regulation of protein function (Rakitzis, 1990; Veal et al., 2007), including modulation of ion channel gating, as exemplified by the activation of TRPA1 channels by natural isothiocyanate-containing compounds (Hinman et al., 2006). Additionally, there are several reactions involving reversible covalent modifications of histidine residues in other systems (including several mediated by ascorbate), despite the fact that the reversibility is predicted to be energetically unfavorable (Farver et al., 1998; Njus et al., 2001). It is possible that endogenous enzymes with the ability to reverse the effects of MCO exist within neurons; however, additional experiments will be necessary to evaluate this possibility.

Ascorbate can function as a neuromodulator, is concentrated in both extra (100–500 μm) and intracellular (up to 10 mm) brain spaces, and can undergo dynamic changes in a variety of physiological and pathophysiological conditions (Rice, 2000). Thus, it is interesting to speculate on the functional significance of Cav3.2 modulation by ascorbate, especially considering Cav3.2-dependent LTSs are crucial to the synchronization of low-amplitude oscillations in the loop of mutually interconnected nRT, thalamic relay, and cortical neurons (Perez-Reyes, 2003). Additionally, modulation of Cav3.2 by genetic or pharmacological means has been shown to modulate LTSs and burst firing in nRT neurons as evidenced by altered excitability in both current-clamp recordings (Joksovic et al., 2006) and in silico simulations (Vitko et al., 2005). Thus, modulation of these channels by ascorbate under conditions that favor MCO may have important consequences for a variety of physiological processes and pathological conditions. Such conditions may include those associated with neuronal injury, epilepsy, Alzheimer's disease, Menke's disease, and Wilson's disease, where there are documented increases in extracellular (free) redox-reactive transition metals such as Cu2+ and Fe3+ (Strausak et al., 2001; Bush, 2003; Mathie et al., 2006). High levels of Cu2+ (200–400 μm) can also be released from synaptic terminals onto postsynaptic cells known to contain Cav3.2 channels in such brain areas as the hippocampus and olfactory bulb (Mathie et al., 2006). Future studies are necessary to investigate these possibilities, as well as to determine whether other ion channels such as NR1/NR2A NMDA receptors that are known to contain high-affinity metal binding sites (Herin and Aizenman, 2004), show inhibition by ascorbate (Majewska and Bell, 1990; Majewska et al., 1990), and undergo covalent modification by free radicals (Aizenman et al., 1990) are subject to similar regulation.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NS054521 (M.T.N.), HL36977 (P.Q.B.), MH077791 and NS057105 (C.F.Z.), NS38691 (E.P.-R.), and GM075299 (S.M.T.), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (T.P.S.), and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (L.S.D.). We thank Le Banh of the University of Virginia for helpful comments on this manuscript.

References

- Aizenman E, Hartnett KA, Reynolds IJ. Oxygen free radicals regulate NMDA receptor function via a redox modulatory site. Neuron. 1990;5:841–846. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90343-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush AI. The metallobiology of Alzheimer's disease. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:207–214. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Lamping KG, Nuno DW, Barresi R, Prouty SJ, Lavoie JL, Cribbs LL, England SK, Sigmund CD, Weiss RM, Williamson RA, Hill JA, Campbell KP. Abnormal coronary function in mice deficient in alpha1H T-type Ca2+ channels. Science. 2003;302:1416–1418. doi: 10.1126/science.1089268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevion M. A site-specific mechanism for free radical induced biological damage: The essential role of redox-active transition metals. Free Radic Biol Med. 1988;5:27–37. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(88)90059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farver O, Eady RR, Abraham ZH, Pecht I. The intramolecular electron transfer between copper sites of nitrite reductase: A comparison with ascorbate oxidase. FEBS Lett. 1998;436:239–242. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herin GA, Aizenman E. Amino terminal domain regulation of NMDA receptor function. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;500:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinman A, Chuang HH, Bautista DM, Julius D. TRP channel activation by reversible covalent modification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19564–19568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609598103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovorka SW, Biesiada H, Williams TD, Huhmer A, Schoneich C. High sensitivity of Zn2+ insulin to metal-catalyzed oxidation: Detection of 2-oxo-histidine by tandem mass spectrometry. Pharm Res. 2002;19:530–537. doi: 10.1023/a:1015164200431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong SW, Park BG, Park JY, Lee JW, Lee JH. Divalent metals differentially block cloned T-type calcium channels. NeuroReport. 2003;14:1537–1540. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200308060-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joksovic PM, Nelson MT, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Patel MK, Perez-Reyes E, Campbell KP, Chen CC, Todorovic SM. CaV3.2 is the major molecular substrate for redox regulation of T-type Ca2+ channels in the rat and mouse thalamus. J Physiol (Lond) 2006;574:415–430. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.110395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HW, Park JY, Jeong SW, Kim JA, Moon HJ, Perez-Reyes E, Lee JH. A molecular determinant of nickel inhibition in Cav3.2 T-type calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4823–4830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Gomora JC, Cribbs LL, Perez-Reyes E. Nickel block of three cloned T-type calcium channels: Low concentrations selectively block α1H. Biophys J. 1999a;77:3034–3042. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77134-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Daud AN, Cribbs LL, Lacerda AE, Pereverzev A, Klockner U, Schneider T, Perez-Reyes E. Cloning and expression of a novel member of the low voltage-activated T-type calcium channel family. J Neurosci. 1999b;19:1912–1921. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-01912.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Peoples RW, Weight FF. Proton potentiation of ATP-gated ion channel responses to ATP and Zn2+ in rat nodose ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:3048–3058. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.5.3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewska MD, Bell JA. Ascorbic acid protects neurons from injury induced by glutamate and NMDA. NeuroReport. 1990;1:194–196. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199011000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewska MD, Bell JA, London ED. Regulation of the NMDA receptor by redox phenomena: Inhibitory role of ascorbate. Brain Res. 1990;537:328–332. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90379-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathie A, Sutton GL, Clarke CE, Veale EL. Zinc and copper: Pharmacological probes and endogenous modulators of neuronal excitability. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111:567–583. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Joksovic PM, Perez-Reyes E, Todorovic SM. The endogenous redox agent L-cysteine induces T-type Ca2+ channel-dependent sensitization of a novel subpopulation of rat peripheral nociceptors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8766–8775. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2527-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njus D, Wigle M, Kelley PM, Kipp BH, Schlegel HB. Mechanism of ascorbic acid oxidation by cytochrome b(561) Biochemistry. 2001;40:11905–11911. doi: 10.1021/bi010403r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti P, Ascher P, Neyton J. High-affinity zinc inhibition of NMDA NR1-NR2A receptors. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5711–5725. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05711.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsey RV, Matteson DR. Ascorbic acid modulation of calcium channels in pancreatic beta cells. J Gen Physiol. 1993;102:503–523. doi: 10.1085/jgp.102.3.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E. Molecular physiology of low-voltage-activated t-type calcium channels. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:117–161. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E, Cribbs LL, Daud A, Lacerda AE, Barclay J, Williamson MP, Fox M, Rees M, Lee JH. Molecular characterization of a neuronal low-voltage-activated T-type calcium channel. Nature. 1998;391:896–900. doi: 10.1038/36110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakitzis ET. Utilization of the free energy of the reversible binding of protein and modifying agent towards the rate-enhancement of protein covalent modification. Biochem J. 1990;269:835–838. doi: 10.1042/bj2690835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ME. Ascorbate regulation and its neuroprotective role in the brain. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01543-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoneich C. Protein modification in aging: an update. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41:807–812. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadtman ER. Ascorbic acid and oxidative inactivation of proteins. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:1125S–1128S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.6.1125s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadtman ER. Oxidation of free amino acids and amino acid residues in proteins by radiolysis and by metal-catalyzed reactions. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:797–821. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.004053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strausak D, Mercer JF, Dieter HH, Stremmel W, Multhaup G. Copper in disorders with neurological symptoms: Alzheimer's, Menkes, and Wilson diseases. Brain Res Bull. 2001;55:175–185. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00454-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg RJ, Martin BR. Interactions of histidine and other imidazole derivatives with transition metal ions in chemical and biological systems. Chem Rev. 1974;74:471–517. [Google Scholar]

- Talley EM, Cribbs LL, Lee JH, Daud A, Perez-Reyes E, Bayliss DA. Differential distribution of three members of a gene family encoding low voltage-activated (T-type) calcium channels. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1895–1911. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-01895.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thio LL, Zhang HX. Modulation of inhibitory glycine receptors in cultured embryonic mouse hippocampal neurons by zinc, thiol containing redox agents and carnosine. Neuroscience. 2006;139:1315–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic SM, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Meyenburg A, Mennerick S, Perez-Reyes E, Romano C, Olney JW, Zorumski CF. Redox modulation of T-type calcium channels in rat peripheral nociceptors. Neuron. 2001;31:75–85. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traboulsie A, Chemin J, Chevalier M, Quignard JF, Nargeot J, Lory P. Subunit-specific modulation of T-type calcium channels by zinc. J Physiol (Lond) 2007;578:159–171. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.114496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida K, Kawakishi S. Site-specific oxidation of angiotensin I by copper(II) and L-ascorbate: conversion of histidine residues to 2-imidazolones. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1990;283:20–26. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90606-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veal EA, Day AM, Morgan BA. Hydrogen peroxide sensing and signaling. Mol Cell. 2007;26:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitko I, Chen Y, Arias JM, Shen Y, Wu XR, Perez-Reyes E. Functional characterization and neuronal modeling of the effects of childhood absence epilepsy variants of CACNA1H, a T-type calcium channel. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4844–4855. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0847-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsby PJ, Wang H, Wolfe JT, Colbran RJ, Johnson ML, Barrett PQ. A mechanism for the direct regulation of T-type calcium channels by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10116–10121. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-31-10116.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White G, Lovinger DM, Weight FF. Transient low-threshold Ca2+ current triggers burst firing through an afterdepolarizing potential in an adult mammalian neuron. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6802–6806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F, Ghezzo-Schoneich E, Aced GI, Hong J, Milby T, Schoneich C. Metal-catalyzed oxidation of histidine in human growth hormone. mechanism, isotope effects, and inhibition by a mild denaturing alcohol. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9019–9029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]