Abstract

Objectives

To use the latest data to estimate the prevalence and correlates of currently diagnosed depression, anxiety problems, and behavioral or conduct problems among children, and the receipt of related mental health treatment.

Study design

We analyzed data from the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) to report nationally representative prevalence estimates of each condition among children aged 3–17 years and receipt of treatment by a mental health professional. Parents/caregivers reported whether their children had ever been diagnosed with each of the 3 conditions and whether they currently have the condition. Bivariate analyses were used to examine the prevalence of conditions and treatment according to sociodemographic and health-related characteristics. The independent associations of these characteristics with both the current disorder and utilization of treatment were assessed using multivariable logistic regression.

Results

Among children aged 3–17 years, 7.1% had current anxiety problems, 7.4% had a current behavioral/ conduct problem, and 3.2% had current depression. The prevalence of each disorder was higher with older age and poorer child health or parent/caregiver mental/emotional health; condition-specific variations were observed in the association between other characteristics and the likelihood of disorder. Nearly 80% of those with depression received treatment in the previous year, compared with 59.3% of those with anxiety problems and 53.5% of those with behavioral/conduct problems. Model-adjusted effects indicated that condition severity and presence of a comorbid mental disorder were associated with treatment receipt.

Conclusions

The latest nationally representative data from the NSCH show that depression, anxiety, and behavioral/ conduct problems are prevalent among US children and adolescents. Treatment gaps remain, particularly for anxiety and behavioral/conduct problems.

Childhood mental disorders are a public health concern due to their prevalence, early onset, and impact on children, families, and communities.1,2 Mental disorders in childhood can negatively affect healthy development by interfering with children’s ability to achieve social, emotional, cognitive, and academic milestones and to function in daily settings. In addition, mental disorders account for the largest area of aggregate medical spending ($8.9 billion) among all health disorders that contribute to overall child health expenses.3 Despite evidence of high expenses related to medical care, mental health treatment utilization among children is relatively low, with a significant portion of children receiving no mental health treatment even though they may have a mental disorder.4,5

Existing national surveys indicate that between 13% and 20% of children in the US have a mental, emotional, or behavioral disorder each year, although most of these surveys have focused on adolescents (age 12–17 years) or did not assess multiple diagnoses.2 Trends across time in these data suggest that although the prevalence of some childhood mental disorders has remained relatively stable, that of several disorders (eg, depression among adolescents) has increased.6 The prevalence of specific childhood mental disorders has implications for service planning, resource allocation, and prevention and treatment programming. According to a nationally representative survey of adolescents (age 13–18 years) in the US, the most common mental disorders by lifetime prevalence are anxiety (31.9%), behavior (19.1%), and mood (14.3%).7

The purpose of the present study was to use the latest data from the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) to report nationally representative prevalence estimates of current depression, anxiety problems, and behavioral or conduct problems among children aged 3–17 years in the US and the receipt of past-year mental health treatment among those with each condition. In addition to providing the most recent estimates of childhood mental disorders, this study covers a wider range of ages than most national surveys. Although diagnoses of mental health conditions in very young children may be relatively rare, previous research on mental health treatment8,9 has included preschool-aged children because the diagnosis and treatment of these 3 conditions in infants and toddlers is particularly complex. For example, Ali et al found that preschoolers, especially those without a diagnosis, often receive medication treatment without accompanying psychosocial intervention.8 The study examined the sociodemographic and health factors associated with each of these conditions and related treatment, and provides a foundation for future studies using the recently redesigned NSCH.

Methods

We conducted secondary analyses of the 2016 NSCH, an address-based, self-administered survey funded and directed by the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau and conducted by the US Census Bureau. The multistage survey is designed to produce both national- and state-level estimates for key indicators of the physical and emotional health of US children aged 0–17 years and related family and community factors. Between July 2016 and February 2017, the 2016 NSCH sampled approximately 365 000 household addresses, resulting in 50 212 questionnaires completed via web and paper among households with children. The proportion of households known to include children that completed the topical questionnaire was 69.7%. The overall weighted response rate, which includes nonresponse to the screener to identify whether households include children, was 40.7%. An adult (parent/caregiver) who was familiar with the child’s health and health care served as the respondent; 1 child was selected at random to be the subject of the topical questionnaire in households with multiple children. Questionnaires were available in English and Spanish. The design and operation of the survey have been described in detail elsewhere.10–12

Measures

The presence of current mental disorders was assessed in all children using parent/caregiver responses to questions regarding whether a doctor or healthcare provider had ever told the parent/caregiver that the child had depression, anxiety problems, or behavioral or conduct problems (yes/no) and if so, whether the child currently had the condition. For behavioral/ conduct problems, the question also included whether educators such as teachers or school nurses had told the parent/caregiver that the child had the disorder. If the condition was current, parents/caregivers rated the severity of the condition (mild/ moderate/severe). Parents/caregivers also reported whether the child had received any treatment or counseling from a mental health professional (including psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, and clinical social workers) in the previous 12 months (yes/no).

Covariates.

We considered 12 sociodemographic and health- related characteristics as covariates that were identified a priori from the literature as being associated with mental disorders and receipt of treatment.7,13 These included 6 child-level factors: sex, age, race/ethnicity, insurance status and type (private only, public only, combined public and private, unspecified, and uninsured), respondent-reported physical health status (excellent/ very good, good, fair/poor), and presence of current comorbid mental health problems. Six household-level factors were also included: poverty level (<100% federal poverty level [FPL], 100%−199% FPL, 200%−399% FPL, and ≥400% FPL), family structure (2 married parents, 2 unmarried parents, single mother, other), household educational attainment (highest level of education attained by either parent/primary caregiver: less than high school, high school/GED/vocational training, college degree or higher), respondent mental or emotional health status (excellent/very good, good, fair/poor), geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West) and urban/rural location (not in Core-Based Statistical Area, Micropolitan, Metropolitan, and Metropolitan Principal City).

Statistical Analyses

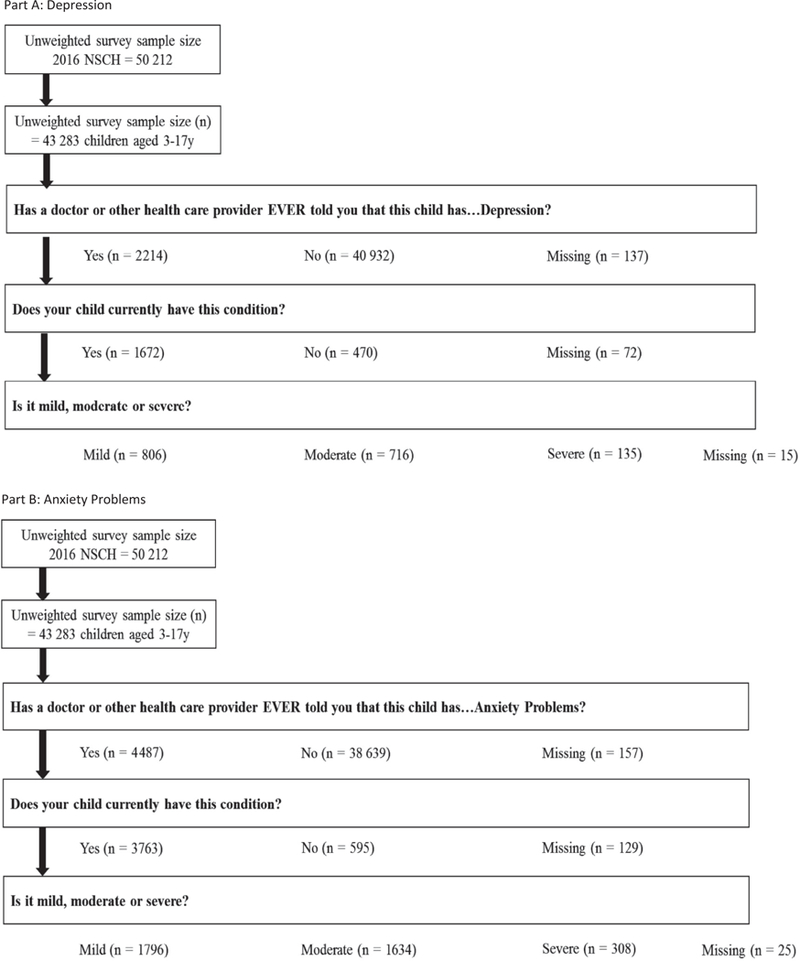

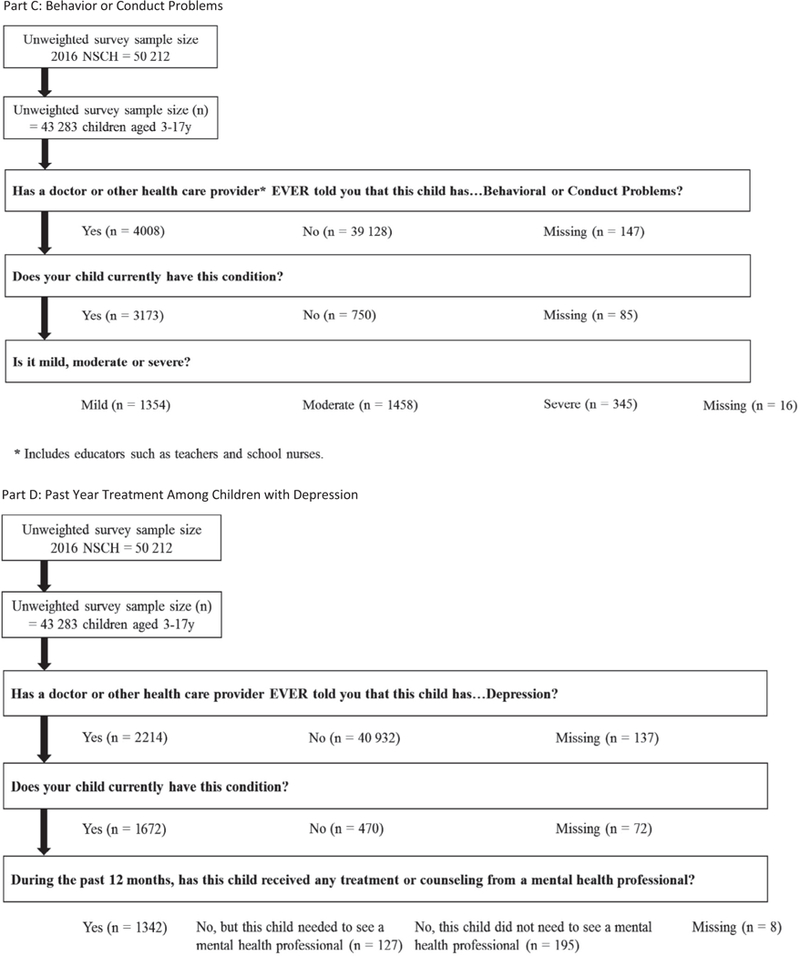

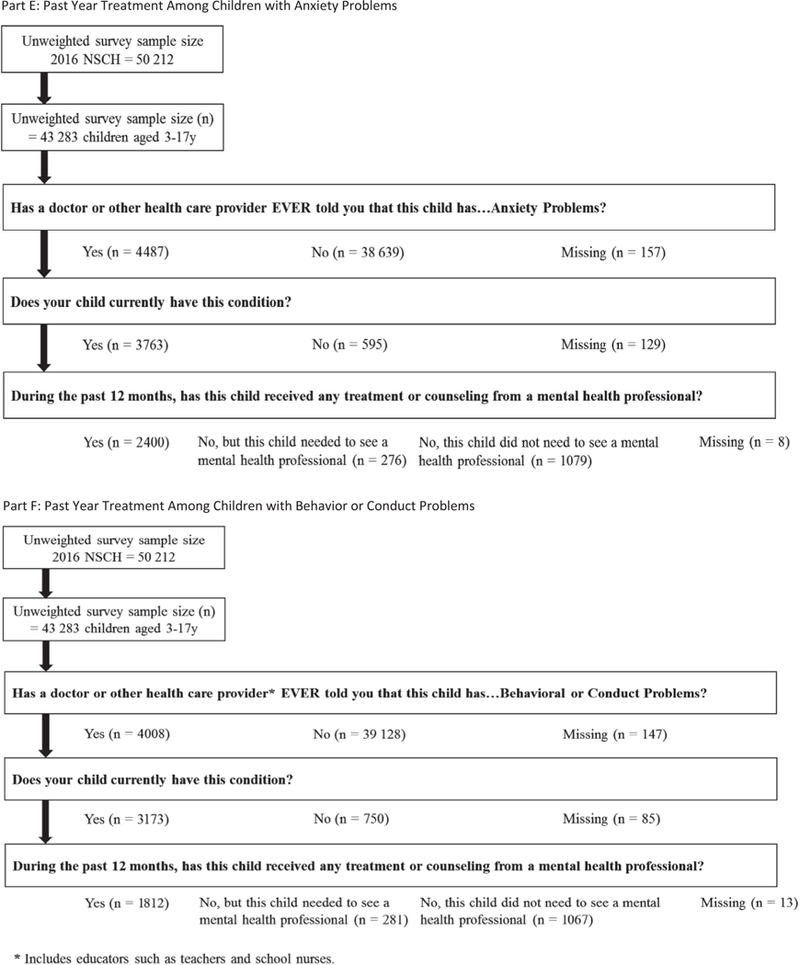

For this study, analyses were limited to 43 283 children aged 3–17 years (Figure; available at www.jpeds.com). Bivariate and multivariable analyses were conducted to assess the associations between the selected sociodemographic and health- related characteristics and current depression, anxiety problems, and behavioral/conduct problems, as well as receipt of mental health treatment or counseling among those with each of the aforementioned disorders. Next, independent associations between selected covariates and both the presence of current disorders and receipt of treatment were identified; separate multivariable logistic regression models were used to estimate predicted odds, which were converted to marginal probabilities for presentation as the adjusted prevalence ratios (aPRs)14 of having each of the 3 disorders and of receiving treatment given the presence of 1 of these conditions.

Figure.

Unweighted survey sample sizes for children 3–17 years with valid data for depression, anxiety problems, behavior or conduct problems, and receipt of related treatment, national survey of children’s health, 2016.

Children with missing data on the outcomes of interest (disorder or receipt of treatment) were excluded. The respective sample sizes for children with valid data for depression, anxiety problems, and behavioral/conduct problems, as well as treatment, are presented in the Figure. Child sex, race, and ethnicity were each missing <1% of observations and were imputed by the Census Bureau using hotdeck methods during the weighting process, and the household income-to-poverty ratio (missing 18.6% of observations) was multiply imputed using regression methods. All data were obtained from the public use data file with the exception of data for urban/rural location, which were available only from confidential restricted-access files at the Census Bureau. Analyses were conducted using SAS- callable SUDAAN version 11.0.1 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina) to adjust for the multistage sample design. Survey weights supplied by the Census Bureau were applied to account for noncoverage and nonresponse and reflect the US population of all noninstitutionalized children aged 0–17 years.

Results

Prevalence estimates for each disorder, overall and by sociodemographic and health-related characteristics, are presented in Table I. In 2016, 3.2% of US children and adolescents (approximately 1.9 million) had current depression, 7.1% (approximately 4.4 million) had a current anxiety problem, and 7.4% (approximately 4.5 million) had a current behavioral/ conduct problem. Differences in the severity and presence of comorbid disorders were observed across conditions. Among children and adolescents with current depression, 9.7% were rated by parents/caregivers has being severely affected by their condition and approximately 45% were rated as being mildly or moderately affected, respectively. Approximately 8% of children with a current anxiety problem were rated as severely affected, compared with approximately 45% who were rated mildly or moderately affected. Finally, nearly 13% of children with diagnosed behavioral/conduct problems were rated as severely affected, 40% were rated as mildly affected, and 48% were rated as moderately affected. The presence of a comorbid mental disorder was most commonly reported among those with current depression, with nearly three-quarters also reporting a current anxiety problem.

Table I.

Prevalence of currently diagnosed depression, anxiety, and behavioral/conduct problems among children aged 3–17 years, by sociodemographic and health characteristics, NSCH 2016

| Currently diagnosed with depression |

Currently diagnosed with anxiety |

Currently diagnosed with behavioral or conduct problems |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Unweighted, n |

Weighted, N |

Weighted, % |

95% CI | Unweighted, n |

Weighted, N |

Weighted, % |

95% CI | Unweighted, n |

Weighted, N |

Weighted, % |

95% CI |

| All children (3–17 y) | 1 934 000 | 3.2 | 2.9–3.5 | 4 355 000 | 7.1 | 6.6–7.6 | 4 509 000 | 7.4 | 6.9–7.9 | |||

| Severity of diagnosed condition | ||||||||||||

| Mild | 806 | 885 000 | 46.3 | 41.4–51.2 | 1796 | 1 949 000 | 45.2 | 41.5–48.9 | 1342 | 1 748 000 | 39.5 | 36.1–42.9 |

| Moderate | 716 | 841 000 | 44.0 | 39.1–49.0 | 1634 | 2 037 000 | 47.2 | 43.4–51.1 | 1445 | 2 110 000 | 47.6 | 44.1–51.2 |

| Severe | 135 | 185 000 | 9.7 | 6.6–14.0 | 308 | 326 000 | 7.6 | 6.2–9.2 | 335 | 572 000 | 12.9 | 10.6–15.7 |

| Current depression | N/A | 1280 | 1 402 000 | 32.3 | 29.1–35.8 | 673 | 908 000 | 20.3 | 17.7–23.2 | |||

| Current anxiety | 1280 | 1 402 000 | 73.8 | 69.4–77.8 | N/A | 1308 | 1 630 000 | 36.6 | 33.2–40.1 | |||

| Current behavioral or conduct problems | 673 | 908 000 | 47.2 | 42.3–52.2 | 1308 | 1 630 000 | 37.9 | 34.3–41.6 | N/A | |||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 715 | 932 000 | 3.0 | 0.2–2.6 | 1783 | 2 164 000 | 6.9 | 6.2–7.7 | 2205 | 3 155 000 | 10.1 | 9.3–10.9 |

| Female | 957 | 1 002 000 | 3.3 | 0.2–2.9 | 1980 | 2 191 000 | 7.3 | 6.6–8.1 | 968 | 1 354 000 | 4.5 | 4.0–5.1 |

| Age, y | ||||||||||||

| 3–5 | 7 | 9000 | *0.08 | 0.0–0.2 | 113 | 153 000 | 1.3 | 0.9–1.7 | 288 | 410 000 | 3.4 | 2.8–4.2 |

| 6–11 | 271 | 421 000 | 1.7 | 1.3–2.2 | 1115 | 1 624 000 | 6.6 | 5.7–7.6 | 1390 | 2 259 000 | 9.1 | 8.3–10.1 |

| 12–17 | 1394 | 1 504 000 | 6.1 | 5.5–6.8 | 2535 | 2 578 000 | 10.5 | 9.7–11.3 | 1495 | 1 840 000 | 7.5 | 6.7–8.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 184 | 330 000 | 2.2 | 1.6–2.9 | 375 | 915 000 | 6.0 | 4.8–7.5 | 364 | 837 000 | 5.5 | 4.5–6.7 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 1198 | 1 088 000 | 3.4 | 3.1–3.8 | 2908 | 2 713 000 | 8.6 | 8.0–9.2 | 2158 | 2 394 000 | 7.6 | 7.0–8.2 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 110 | 331 000 | 4.2 | 3.1–5.6 | 136 | 358 000 | 4.5 | 3.4–5.9 | 287 | 848 000 | 10.7 | 9.1–12.7 |

| Non-Hispanic multiracial/other | 180 | 184 000 | 2.9 | 2.3–3.6 | 344 | 368 000 | 5.7 | 4.4–7.5 | 364 | 430 000 | 6.7 | 5.3–8.5 |

| Family structure | ||||||||||||

| Two parents, married | 899 | 904 000 | 2.3 | 2.0–2.7 | 2385 | 2 504 000 | 6.4 | 5.8–7.0 | 1753 | 1 986 000 | 5.1 | 4.6–5.6 |

| Two parents, unmarried | 130 | 172 000 | 3.5 | 2.3–5.2 | 249 | 404 000 | 8.1 | 5.9–11.1 | 253 | 508 000 | 10.2 | 7.7–13.4 |

| Single mother | 404 | 585 000 | 5.9 | 5.0–7.0 | 736 | 946 000 | 9.6 | 8.4–11.0 | 674 | 1 177 000 | 12.0 | 10.6–13.6 |

| Other | 218 | 254 000 | 4.5 | 3.6–5.6 | 340 | 430 000 | 7.6 | 6.3–9.3 | 422 | 715 000 | 12.7 | 10.7–15.0 |

| Household educational attainment | ||||||||||||

| Less than high school | 53 | 262 000 | 4.6 | 3.0–7.0 | 83 | 419 000 | 7.3 | 5.3–10.1 | 111 | 499 000 | 8.7 | 6.5–11.6 |

| High school, GED, or vocational training | 266 | 422 000 | 3.6 | 2.9–4.4 | 467 | 810 000 | 6.9 | 5.7–8.3 | 524 | 988 000 | 8.4 | 7.2–9.7 |

| More than high school | 1317 | 1 191 000 | 2.9 | 2.6–3.2 | 3139 | 3 013 000 | 7.2 | 6.7–7.8 | 2438 | 2 840 000 | 6.8 | 6.3–7.4 |

| Household poverty | ||||||||||||

| <100% FPL | 273 | 625 000 | 4.8 | 3.8–6.0 | 463 | 984 000 | 7.6 | 6.3–9.0 | 557 | 1 405 000 | 10.8 | 9.4–12.4 |

| 100%−199% FPL | 334 | 420 000 | 3.1 | 2.4–3.9 | 659 | 1 010 000 | 7.4 | 6.1–9.0 | 650 | 1 024 000 | 7.5 | 6.4–8.8 |

| 200%−399% FPL | 500 | 453 000 | 2.8 | 2.2–3.4 | 1136 | 1 124 000 | 6.8 | 5.9–7.9 | 923 | 1 066 000 | 6.5 | 5.6–7.5 |

| >400% FPL | 565 | 436 000 | 2.4 | 2.0–2.8 | 1505 | 1 237 000 | 6.8 | 6.1–7.6 | 1043 | 1 014 000 | 5.6 | 5.0–6.3 |

| Insurance status | ||||||||||||

| Public only | 552 | 911 000 | 4.8 | 4.1–5.6 | 951 | 1 712 000 | 9.0 | 7.8–10.4 | 1132 | 2 170 000 | 11.5 | 10.3–12.8 |

| Private only | 905 | 735 000 | 2.1 | 1.9–2.4 | 2390 | 2 085 000 | 6.1 | 5.6–6.5 | 1598 | 1 608 000 | 4.7 | 4.3–5.1 |

| Private and public | 126 | 148 000 | 5.5 | 3.8–8.0 | 272 | 360 000 | 13.5 | 10.3–17.5 | 309 | 471 000 | 17.7 | 13.8–22.3 |

| Insurance type unspecified† | 17 | 17 000 | *1.61 | 0.8–3.2 | 37 | 43 000 | 4.0 | 2.5–6.5 | 27 | 75 000 | 7.1 | 4.1–12.1 |

| Not insured | 62 | 99 000 | 2.6 | 1.7–4.1 | 99 | 130 000 | 3.5 | 2.4–5.0 | 89 | 144 000 | 3.8 | 2.8–5.3 |

| Region | ||||||||||||

| Northeast | 303 | 280 000 | 2.9 | 2.3–3.6 | 867 | 755 000 | 7.7 | 6.8–8.8 | 574 | 675 000 | 6.9 | 5.9–8.1 |

| Midwest | 472 | 517 000 | 4.0 | 3.4–4.6 | 976 | 1 030 000 | 7.9 | 7.1–8.8 | 804 | 1 036 000 | 8.0 | 7.2–8.9 |

| South | 469 | 738 000 | 3.1 | 2.6–3.7 | 1020 | 1 560 000 | 6.6 | 5.9–7.5 | 1015 | 1 902 000 | 8.1 | 7.3–9.0 |

| West | 428 | 400 000 | 2.7 | 2.1–3.4 | 900 | 1 009 000 | 6.7 | 5.5–8.2 | 780 | 895 000 | 6.0 | 4.9–7.2 |

| Rural/urban location‡ | ||||||||||||

| Not in CBSA | 144 | 94 000 | 3.6 | 2.7–4.8 | 278 | 185 000 | 7.0 | 5.7–8.7 | 251 | 218 000 | 8.3 | 6.8–10.2 |

| Micropolitan Statistical Area | 217 | 198 000 | 4.1 | 3.2–5.3 | 449 | 354 000 | 7.5 | 6.3–8.8 | 421 | 444 000 | 9.3 | 7.9–10.9 |

| Metropolitan Statistical Area | 862 | 956 000 | 2.8 | 2.4–3.1 | 2096 | 2 501 000 | 7.2 | 6.6–7.9 | 1644 | 2 377 000 | 6.9 | 6.3–7.6 |

| Metropolitan Principal City | 449 | 687 000 | 3.6 | 2.9–4.3 | 940 | 1 315 000 | 6.8 | 5.8–7.9 | 857 | 1 470 000 | 7.6 | 6.7–8.7 |

| Health characteristics Child’s health status | ||||||||||||

| Excellent or very good | 1047 | 1 160 000 | 2.1 | 1.9–2.4 | 2772 | 2 814 000 | 5.2 | 4.8–5.6 | 2294 | 3 005 000 | 5.5 | 5.1–6.0 |

| Good | 479 | 545 000 | 9.8 | 8.1–11.7 | 779 | 1 187 000 | 21.5 | 18.0–25.4 | 684 | 1 120 000 | 20.2 | 17.2–23.5 |

| Fair or poor | 140 | 214 000 | 18.0 | 12.4–25.3 | 203 | 336 000 | 28.3 | 20.9–37.0 | 187 | 361 000 | 30.8 | 23.0–40.0 |

| Respondent mental or emotional health | ||||||||||||

| Excellent or very good | 817 | 896 000 | 1.9 | 1.7–2.3 | 2173 | 2 404 000 | 5.2 | 4.7–5.8 | 1805 | 2 456 000 | 5.3 | 4.9–5.8 |

| Good | 537 | 621 000 | 5.9 | 5.0–7.1 | 1071 | 1 206 000 | 11.5 | 10.2–12.9 | 892 | 1 271 000 | 12.1 | 10.7–13.8 |

| Fair or poor | 288 | 383 000 | 13.4 | 10.9–16.3 | 443 | 640 000 | 22.4 | 18.2–27.3 | 385 | 642 000 | 22.4 | 18.2–27.3 |

CBSA, Core-Based Statistical Area.

Adjusted for all variables above.

Includes children who were reported to have current insurance, but did not specify coverage type from a list of 5 types or provide an interpretable write-in.

Based on the combination of 3 separate geographical identifiers: CBSA, Metropolitan Statistical Area, and Metropolitan Principal City.

The prevalence of each disorder varied by sociodemo-graphic and health-related factors (χ2 test results not shown; data available on request). For example, prevalence varied by sex only for behavioral/conduct problems, for which the prevalence in boys was more than twice that in girls. Estimates also varied by age, with the prevalence of behavioral/conduct problems peaking in middle childhood (age 6–11 years), whereas depression and anxiety problems were most common among adolescents (age 12–17 years). Anxiety problems were most common among non-Hispanic white children compared with children of other racial/ethnic backgrounds, and behavior/ conduct problems were most common among non-Hispanic black children. The prevalence of both depression and behavioral/conduct problems was higher among children living in poor (<100% FPL) households compared with those living in households at ≥200% FPL. The prevalence of all 3 disorders was generally highest among children with public insurance only or some combination of public and private insurance compared with children with private insurance only, with combined public and private insurance, or without insurance. Finally, children in less than excellent or very good physical health and those living with a primary caregiver in fair or poor mental/emotional health had the highest prevalence of any of these disorders compared with children in fair or poor physical health and those living with a caregiver with good, very good, or excellent mental/emotional health. Approximately 30% of children with fair or poor physical health had an anxiety problem or a behavioral/conduct problem, and 18% had depression. Among children with a primary caregiver with fair or poor self-rated mental or emotional health, the prevalence of depression was 13% and the prevalence of anxiety or behavioral/conduct problems was 22%.

Unadjusted PRs and adjusted PRs (aPRs) for the 3 disorders are presented in Table II. Unadjusted PRs provide a complementary illustration of the associations and patterns presented in Table I. After adjustment, the strength of some of these associations was attenuated, and additional associations were observed for race/ethnicity, poverty, and insurance. Compared with non-Hispanic white children, Hispanic children were less likely to have any of the 3 mental disorders, whereas non-Hispanic black children were less likely to have depression and anxiety and were no longer more likely to have behavior/conduct problems. For anxiety and behavioral/ conduct problems, children living in poor households (<100% FPL) were less likely than those in the more advantaged house-holds to have these disorders; in addition, children in nearpoor households (100%−199% of FPL) were less likely to have behavioral/conduct problems. Compared with privately insured children, those with public insurance—either alone or in combination with some form of private coverage—were more likely to have these mental disorders. This was particularly true for behavioral or conduct problems, which were 2–3 times more commonly diagnosed in children with some form of public coverage compared with those with private insurance.

Table II.

Unadjusted PRs and aPRs of currently diagnosed depression, anxiety, and behavioral/conduct problems among children aged 3–17 years, by sociodemographic and health characteristics, NSCH 2016

| Currently diagnosed with depression |

Currently diagnosed with anxiety |

Currently diagnosed with behavioral or conduct problems |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Unadjusted PR | 95% CI | aPR* | 95% CI | Unadjusted PR | 95% CI | aPR* | 95% CI | Unadjusted PR | 95% CI | aPR* | 95% CI |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Female | 1.12 | 0.92–1.36 | 1.11 | 0.92–1.36 | 1.06 | 0.91–1.22 | 1.06 | 0.93–1.21 | 0.45 | 0.38–0.52 | 0.45 | 0.39–0.52 |

| Age, y | ||||||||||||

| 3–5 | 0.01 | 0.00–0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01–0.04 | 0.12 | 0.09–0.17 | 0.14 | 0.10–0.20 | 0.46 | 0.37–0.57 | 0.51 | 0.41–0.64 |

| 6–11 | 0.28 | 0.21–0.36 | 0.29 | 0.22–0.37 | 0.63 | 0.53–0.74 | 0.64 | 0.55–0.75 | 1.22 | 1.06–1.41 | 1.29 | 1.12–1.48 |

| 12–17 | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 0.63 | 0.46–0.86 | 0.43 | 0.30–0.62 | 0.70 | 0.55–0.89 | 0.59 | 0.45–0.76 | 0.73 | 0.59–0.90 | 0.52 | 0.42–0.66 |

| Non-Hispanic white | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.22 | 0.89–1.67 | 0.71 | 0.52–0.97 | 0.53 | 0.40–0.70 | 0.38 | 0.28–0.51 | 1.42 | 1.18–1.71 | 0.88 | 0.72–1.07 |

| Non-Hispanic multiracial/other | 0.83 | 0.64–1.08 | 0.83 | 0.63–1.10 | 0.67 | 0.51–0.89 | 0.65 | 0.53–0.81 | 0.89 | 0.69–1.14 | 0.80 | 0.65–0.99 |

| Family structure | ||||||||||||

| Two parents, married | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Two parents, unmarried | 1.50 | 0.97–2.31 | 0.99 | 0.64–1.54 | 1.27 | 0.91–1.77 | 1.10 | 0.81–1.49 | 2.01 | 1.50–2.70 | 1.48 | 1.16–1.9 |

| Single mother | 2.58 | 2.05–3.24 | 1.34 | 1.04–1.73 | 1.51 | 1.28–1.78 | 1.17 | 0.97–1.41 | 2.37 | 2.02–2.77 | 1.55 | 1.31–1.84 |

| Other | 1.96 | 1.50–2.54 | 1.12 | 0.82–1.53 | 1.19 | 0.96–1.49 | 0.93 | 0.71–1.22 | 2.51 | 2.07–3.04 | 1.60 | 1.27–2.00 |

| Household educational attainment | ||||||||||||

| Less than high school | 1.60 | 1.03–2.50 | 1.02 | 0.61–1.71 | 1.01 | 0.73–1.41 | 0.74 | 0.49–1.11 | 1.28 | 0.94–1.73 | 0.84 | 0.58–1.21 |

| High school, GED, or vocational training | 1.26 | 1.01–1.57 | 0.82 | 0.64–1.04 | 0.95 | 0.77–1.17 | 0.74 | 0.60–0.93 | 1.23 | 1.04–1.45 | 0.83 | 0.70–0.98 |

| More than high school | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Household poverty | ||||||||||||

| <100% FPL | 2.00 | 1.53–2.61 | 0.82 | 0.57–1.18 | 1.11 | 0.91–1.36 | 0.69 | 0.52–0.90 | 1.93 | 1.62–2.31 | 0.76 | 0.60–0.96 |

| 100%−199% FPL | 1.29 | 0.96–1.73 | 0.76 | 0.56–1.04 | 1.09 | 0.86–1.37 | 0.81 | 0.65–1.02 | 1.35 | 1.10–1.65 | 0.70 | 0.66–0.87 |

| 200%−399% FPL | 1.15 | 0.85–1.55 | 0.94 | 0.71–1.24 | 1.00 | 0.84–1.20 | 0.91 | 0.78–1.06 | 1.16 | 0.96–1.41 | 0.87 | 0.74–1.02 |

| ≥400% FPL | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Insurance status | ||||||||||||

| Public only | 2.25 | 1.83–2.77 | 2.00 | 1.53–2.60 | 1.49 | 1.27–1.76 | 1.68 | 1.36–2.07 | 2.47 | 2.14–2.84 | 2.17 | 1.79–2.64 |

| Private only | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Private and public | 2.60 | 1.74–3.88 | 1.81 | 1.17–2.78 | 2.23 | 1.69–2.95 | 1.88 | 1.45–2.42 | 3.79 | 2.93–4.89 | 3.16 | 2.44–4.08 |

| Insurance type unspecified† | 0.76 | 0.37–1.54 | 0.79 | 0.39–1.60 | 0.67 | 0.41–1.08 | 0.78 | 0.48–1.27 | 1.52 | 0.88–2.64 | 1.24 | 0.68–2.26 |

| Not insured | 1.24 | 0.79–1.94 | 1.05 | 0.64–1.73 | 0.57 | 0.39–0.84 | 0.65 | 0.44–0.96 | 0.82 | 0.59–1.14 | 0.84 | 0.59–1.19 |

| Rural/urban location‡ | ||||||||||||

| Not in CBSA | 1.30 | 0.95–1.78 | 0.85 | 0.61–1.21 | 0.97 | 0.78–1.22 | 0.81 | 0.64–1.02 | 1.21 | 0.97–1.51 | 0.96 | 0.77–1.20 |

| Micropolitan Statistical Area | 1.50 | 1.14–1.97 | 1.16 | 0.87–1.54 | 1.03 | 0.86–1.24 | 0.88 | 0.74–1.06 | 1.35 | 1.12–1.63 | 1.06 | 0.89–1.26 |

| Metropolitan Statistical Area | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Metropolitan Principal City | 1.29 | 1.02–1.63 | 1.13 | 0.90–1.42 | 0.94 | 0.78–1.13 | 0.97 | 0.81–1.15 | 1.11 | 0.94–1.30 | 0.95 | 0.81–1.12 |

| Health characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Child’s health | ||||||||||||

| Excellent or very good | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Good | 4.60 | 3.69–5.73 | 2.70 | 2.05–3.55 | 4.15 | 3.45–5.00 | 3.34 | 2.70–4.12 | 3.65 | 3.06–4.34 | 2.54 | 2.12–3.05 |

| Fair or poor | 8.44 | 5.78–12.32 | 5.78 | 3.87–8.63 | 5.47 | 4.07–7.34 | 4.80 | 3.55–6.49 | 5.58 | 4.18–7.43 | 3.94 | 2.93–5.30 |

| Respondent mental or emotional health | ||||||||||||

| Excellent or very good | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Good | 3.05 | 2.42–3.84 | 2.08 | 1.62–2.68 | 2.21 | 1.89–2.58 | 1.67 | 1.41–1.97 | 2.28 | 1.95–2.66 | 1.59 | 1.36–1.85 |

| Fair or poor | 6.89 | 5.37–8.84 | 3.62 | 2.68–4.90 | 4.30 | 3.43–5.40 | 2.88 | 2.25–3.68 | 4.21 | 3.38–5.24 | 2.39 | 1.92–2.99 |

Bold values are statistically significant results.

Adjusted for all variables above.

Includes children who were reported to have current insurance but did not specify coverage type from a list of 5 types or provide an interpretable write-in.

Based on the combination of 3 separate geographical identifiers: CBSA, Metropolitan Statistical Area, and Metropolitan Principal City.

Table III details the receipt of past-year treatment or counseling by a mental health professional among children with each of the 3 disorders. Overall, treatment receipt was more common among children with depression (78.1%), whereas the receipt of treatment for anxiety and behavioral/conduct problems was 59.3% and 53.5%, respectively. The receipt of treatment varied by selected sociodemographic and health-related characteristics among children with each disorder (χ2 test results available on request). For both anxiety problems and behavioral/ conduct problems, treatment receipt was more common among school-aged children compared with those aged 3–5 years, and among those living in the wealthiest households (≥400% FPL) compared with those living in poverty (<100% FPL). No other statistically significant differences by poverty or insurance status or type were observed. For anxiety and behavioral/conduct problems, receipt of treatment was more likely among children with greater condition severity.

Table III.

Receipt of past year mental health treatment or counseling among children ages 3–17 currently diagnosed depression, anxiety, and behavioral/conduct problems, by sociodemographic and health characteristics, NSCH 2016

| Currently Diagnosed with Depression |

Currently Diagnosed with Anxiety |

Currently Diagnosed with Behavioral or Conduct Problems |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted N |

Weighted % |

95% CI | Weighted N |

Weighted % |

95% CI | Weighted N |

Weighted % |

95% CI | ||||

| All children (3–17 y) | 1491000 | 78.0 | 73.9 | 81.7 | 2576000 | 59.3 | 55.5 | 63.1 | 2387000 | 53.5 | 49.9 | 57.0 |

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 691 000 | 75.2 | 67.9 | 81.3 | 1320000 | 61.1 | 55.5 | 66.4 | 1625000 | 52.0 | 47.8 | 56.1 |

| Female | 800000 | 80.7 | 76.2 | 84.5 | 1256000 | 57.6 | 52.2 | 62.9 | 762000 | 57.0 | 50.1 | 63.7 |

| Age, years | ||||||||||||

| 3–5y | 6000 | *66.42 | 21.4 | 93.5 | 52000 | 34.1 | 22.7 | 47.7 | 139000 | 34.6 | 26.0 | 44.3 |

| 6–11y | 307000 | 74.8 | 64.2 | 83.1 | 885000 | 54.9 | 47.1 | 62.5 | 1140000 | 50.8 | 45.5 | 56.1 |

| 12–17y | 1177000 | 79.0 | 74.4 | 83.0 | 1638000 | 63.7 | 59.7 | 67.5 | 1109000 | 60.9 | 55.7 | 65.8 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 268000 | 83.5 | 74.7 | 89.6 | 468000 | 51.5 | 39.7 | 63.2 | 419000 | 50.6 | 40.8 | 60.4 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 854000 | 78.8 | 73.4 | 83.3 | 1676000 | 61.9 | 58.4 | 65.3 | 1300000 | 54.4 | 50.3 | 58.5 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 243000 | 73.8 | 60.0 | 84.1 | 238000 | 66.8 | 53.7 | 77.7 | 463000 | 56.0 | 47.2 | 64.5 |

| Non-Hispanic multiracial/other | 126000 | 71.6 | 59.0 | 81.6 | 194000 | 52.6 | 38.3 | 66.6 | 206000 | 48.6 | 36.4 | 61.0 |

| Family Structure | ||||||||||||

| Two Parents, Married | 710000 | 79.5 | 72.9 | 84.7 | 1428000 | 57.1 | 51.8 | 62.2 | 1059000 | 53.5 | 48.7 | 58.3 |

| Two Parents, Unmarried | 121000 | 70.2 | 51.5 | 83.9 | 212000 | 52.6 | 36.1 | 68.5 | 256000 | 50.4 | 36.0 | 64.8 |

| Single Mother | 470000 | 81.5 | 74.7 | 86.9 | 634000 | 67.7 | 61.5 | 73.4 | 661000 | 56.9 | 50.5 | 63.1 |

| Other | 178000 | 72.0 | 60.7 | 81.0 | 261000 | 61.0 | 50.8 | 70.3 | 365000 | 52.6 | 43.7 | 61.3 |

| Household Educational Attainment | 0 | |||||||||||

| Less than High School | 203000 | 79.7 | 59.9 | 91.2 | 218000 | 53.0 | 36.8 | 68.5 | 301000 | 61.6 | 46.5 | 74.7 |

| High School, GED, or Vocational | 300000 | 71.8 | 61.9 | 80.0 | 445000 | 55.2 | 44.8 | 65.0 | 467000 | 47.7 | 40.4 | 55.2 |

| Training | ||||||||||||

| More than High School | 952000 | 80.5 | 76.4 | 84.1 | 1834000 | 61.0 | 56.7 | 65.0 | 1527000 | 53.9 | 49.8 | 58.0 |

| Household poverty | ||||||||||||

| <100% FPL | 418000 | 67.9 | 57.7 | 76.5 | 542000 | 55.6 | 46.1 | 64.8 | 689000 | 49.7 | 42.4 | 56.9 |

| 100–199% FPL | 342000 | 82.5 | 74.5 | 88.4 | 569000 | 56.6 | 46.6 | 66.0 | 598000 | 59.0 | 50.9 | 66.7 |

| 200–399% FPL | 370000 | 82.0 | 75.1 | 87.2 | 637000 | 56.7 | 49.4 | 63.8 | 514000 | 48.6 | 40.8 | 56.5 |

| ≥400% FPL | 361000 | 84.3 | 78.1 | 89.0 | 828000 | 66.9 | 61.9 | 71.5 | 585000 | 58.1 | 51.9 | 64.1 |

| Insurance Status | ||||||||||||

| Public Only | 690000 | 76.0 | 68.8 | 81.9 | 1023000 | 59.8 | 51.8 | 67.4 | 1177000 | 54.3 | 48.6 | 59.9 |

| PrivateOnly | 579000 | 79.6 | 73.8 | 84.3 | 1215000 | 58.3 | 54.3 | 62.3 | 809000 | 50.5 | 46.0 | 55.0 |

| Private and Public | 131000 | 89.3 | 79.1 | 94.9 | 251000 | 70.0 | 58.3 | 79.6 | 281000 | 59.8 | 46.5 | 71.8 |

| Insurance Type Unspecified† | 11000 | *65.84 | 34.1 | 87.8 | 16000 | 38.4 | 20.4 | 60.2 | 37000 | *48.76 | 24.6 | 73.5 |

| Not Insured | 72000 | 73.3 | 52.3 | 87.3 | 62000 | 47.8 | 30.6 | 65.5 | 78000 | 55.9 | 40.7 | 70.1 |

| Region | ||||||||||||

| Northeast | 217000 | 80.1 | 68.7 | 88.1 | 455000 | 60.9 | 53.8 | 67.5 | 358000 | 53.8 | 45.6 | 61.8 |

| Midwest | 403000 | 78.6 | 70.7 | 84.8 | 654000 | 63.6 | 58.3 | 68.6 | 635000 | 61.8 | 56.2 | 67.1 |

| South | 556000 | 76.4 | 68.6 | 82.8 | 935000 | 60.1 | 53.8 | 66.0 | 941000 | 50.0 | 44.5 | 55.5 |

| West | 316000 | 79.0 | 70.5 | 85.5 | 531000 | 52.8 | 42.2 | 63.1 | 453000 | 50.9 | 41.2 | 60.5 |

| Rural/Urban Location‡ | ||||||||||||

| Not in CBSA | 60000 | 65.7 | 49.9 | 78.7 | 101000 | 54.8 | 44.0 | 65.1 | 110000 | 51.2 | 40.8 | 61.5 |

| Micropolitan Statistical Area | 139000 | 70.3 | 57.0 | 80.9 | 199000 | 56.1 | 47.9 | 64.0 | 223000 | 50.6 | 42.4 | 58.8 |

| Metropolitan Statistical Area | 757000 | 79.7 | 73.8 | 84.5 | 1450000 | 58.1 | 53.0 | 63.0 | 1225000 | 51.9 | 47.1 | 56.8 |

| Metropolitan Principal City | 535000 | 79.7 | 72.1 | 85.6 | 827000 | 63.3 | 55.2 | 70.7 | 829000 | 57.2 | 50.4 | 63.7 |

| Health Characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Severity of diagnosed condition | ||||||||||||

| Mild | 647000 | 74.6 | 68.4 | 79.9 | 935000 | 48.3 | 43.3 | 53.3 | 757000 | 43.9 | 38.9 | 49.1 |

| Moderate | 663000 | 79.2 | 72.4 | 84.7 | 1370000 | 67.2 | 60.7 | 73.2 | 1126000 | 53.8 | 48.3 | 59.2 |

| Severe | 165000 | 89.0 | 77.2 | 95.0 | 240000 | 74.4 | 63.9 | 82.6 | 446000 | 78.0 | 69.5 | 84.6 |

| Child’s health | ||||||||||||

| Excellent or very good | 892000 | 77.5 | 71.8 | 82.4 | 1657000 | 58.9 | 55.2 | 62.5 | 1535000 | 51.4 | 47.6 | 55.3 |

| Good | 419000 | 78.4 | 71.5 | 84.0 | 695000 | 59.0 | 48.4 | 68.9 | 630000 | 56.8 | 48.0 | 65.2 |

| Fair or poor | 166000 | 79.5 | 64.3 | 89.3 | 207000 | 62.6 | 48.6 | 74.7 | 209000 | 59.9 | 46.1 | 72.3 |

| Current Depression | N/A | 1135000 | 81.7 | 77.2 | 85.5 | 752000 | 84.3 | 78.4 | 88.7 | |||

| Current Anxiety | 1135000 | 81.7 | 77.2 | 85.5 | N/A | 1191000 | 73.7 | 67.4 | 79.1 | |||

| Current Behavioral or Conduct Problems | 752000 | 84.3 | 78.4 | 88.7 | 1191000 | 73.7 | 67.4 | N/A | ||||

| Respondent Mental or Emotional Health | ||||||||||||

| Excellent or very good | 708000 | 79.5 | 72.7 | 84.9 | 1382000 | 57.6 | 52.2 | 79.1 | 1229000 | 50.3 | 45.9 | 54.8 |

| Good | 503000 | 83.5 | 78.2 | 87.7 | 769000 | 64.3 | 58.8 | 69.5 | 708000 | 56.4 | 49.8 | 62.8 |

| Fair or poor | 261000 | 68.0 | 57.6 | 77.0 | 377000 | 58.9 | 46.7 | 70.1 | 393000 | 61.5 | 49.2 | 72.5 |

CI, Confidence Interval; GED, General Equivalency Diploma; FPL, Federal Poverty Level.

Adjusted for all variables above.

Includes children who were reported to have current insurance, but did not specify coverage type from a list of five types or provide an interpretable write-in.

Based on the combination of three separate geographical identifiers: Core Based Statistical Area (CBSA), Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), and Metropolitan Principal City (MPC).

The independent associations between the selected sociodemographic and health-related characteristics and past-year mental health treatment among children with each of the 3 disorders are presented in Table IV. In general, demographic factors were not significantly associated with the likelihood of receiving treatment with the exception of age; among children with anxiety, those aged 3–5 years were less likely than adolescents to have received treatment. Compared with children living in higher-income households (≥400% FPL), poor children (<100% FPL) were less likely to have received treatment across all 3 disorders, as were near-poor children (100%−199% FPL) with anxiety problems and those living in households at 200%−399% FPL with anxiety or behavior/ conduct problems. Insurance status was not significantly associated with receipt of treatment among children with depression or behavioral/conduct problems; however, among children with anxiety problems, those with combined public and private coverage were 1.2 times more likely with those with private coverage to have received treatment. Condition severity and presence of a selected comorbid mental disorder were associated with receipt of treatment among children with each of the disorders; children with a “severe” disorder were 1.2–1.5 times more likely to have received treatment compared with those with a “mild” disorders. Among the comorbidities included, current depression appeared to have the greatest impact on treatment receipt; in those with either anxiety or a behavior/ conduct problem, concurrent depression was associated with an approximately 1.6-fold greater likelihood of receiving treatment compared with those without this comorbidity.

Table IV.

Unadjusted PRs and aPRs of receipt of past-year mental health treatment or counseling among children aged 3–17 years currently diagnosed depression, anxiety, and behavioral/conduct problems, by sociodemographic and health characteristics, NSCH 2016

| Characteristics | Currently diagnosed with depression | Currently diagnosed with anxiety | Currently diagnosed with behavioral or conduct problems |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted PR | 95% CI | aPR* | 95% CI | Unadjusted PR | 95% CI | aPR* | 95% CI | Unadjusted PR | 95% CI | aPR* | 95% CI | |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Female | 1.07 | 0.97–1.19 | 1.08 | 0.98–1.18 | 0.94 | 0.83–1.07 | 1.00 | 0.90–1.11 | 1.10 | 0.95–1.27 | 1.07 | 0.95–1.22 |

| Age, y | ||||||||||||

| 3–5 | 0.84 | 0.43–1.64 | 0.99 | 0.73–1.33 | 0.54 | 0.37–0.78 | 0.71 | 0.54–0.93 | 0.57 | 0.43–0.75 | 0.83 | 0.67–1.05 |

| 6–11 | 0.95 | 0.82–1.09 | 0.96 | 0.85–1.08 | 0.86 | 0.74–1.01 | 0.96 | 0.86–1.07 | 0.83 | 0.73–0.95 | 0.98 | 0.87–1.11 |

| 12–17 | ref | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 1.06 | 0.95–1.18 | 1.06 | 0.95–1.19 | 0.83 | 0.66–1.06 | 0.88 | 0.74–1.06 | 0.93 | 0.75–1.15 | 0.90 | 0.75–1.07 |

| Non-Hispanic white | ref | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.94 | 0.79–1.12 | 1.01 | 0.88–1.15 | 1.08 | 0.89–1.31 | 0.97 | 0.79–1.19 | 1.03 | 0.87–1.22 | 1.01 | 0.86–1.19 |

| Non-Hispanic multiracial/other | 0.91 | 0.77–1.08 | 0.93 | 0.80–1.08 | 0.85 | 0.64–1.13 | 0.80 | 0.63–1.02 | 0.89 | 0.68–1.17 | 0.84 | 0.65–1.10 |

| Family structure | ||||||||||||

| Two parents, married | ref | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ||||||

| Two parents, unmarried | 0.88 | 0.69–1.13 | 0.97 | 0.82–1.15 | 0.92 | 0.66–1.28 | 0.94 | 0.73–1.21 | 0.94 | 0.69–1.28 | 0.98 | 0.77–1.25 |

| Single mother | 1.03 | 0.92–1.14 | 1.08 | 0.98–1.20 | 1.19 | 1.05–1.35 | 1.16 | 1.03–1.31 | 1.06 | 0.92–1.23 | 1.05 | 0.91–1.22 |

| Other | 0.91 | 0.77–1.06 | 0.94 | 0.81–1.08 | 1.07 | 0.89–1.29 | 0.98 | 0.81–1.19 | 0.98 | 0.81–1.19 | 1.00 | 0.81–1.22 |

| Household educational attainment | ||||||||||||

| Less than high school | 0.99 | 0.81–1.21 | 1.00 | 0.84–1.19 | 0.87 | 0.63–1.19 | 0.92 | 0.72–1.19 | 1.14 | 0.89–1.46 | 1.13 | 0.90–1.42 |

| High school, GED, or vocational training | 0.89 | 0.78–1.02 | 0.96 | 0.86–1.07 | 0.90 | 0.74–1.10 | 0.99 | 0.85–1.14 | 0.89 | 0.74–1.05 | 0.88 | 0.75–1.04 |

| More than high school | ref | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ||||||

| Household poverty | ||||||||||||

| <100% FPL | 0.80 | 0.69–0.94 | 0.72 | 0.57–0.90 | 0.83 | 0.69–1.00 | 0.67 | 0.53–0.84 | 0.85 | 0.71–1.03 | 0.74 | 0.59–0.94 |

| 100%−199% FPL | 0.98 | 0.88–1.09 | 0.93 | 0.82–1.04 | 0.85 | 0.70–1.02 | 0.80 | 0.68–0.93 | 1.02 | 0.86–1.21 | 0.95 | 0.81–1.12 |

| 200%−399% FPL | 0.97 | 0.88–1.07 | 0.97 | 0.89–1.06 | 0.85 | 0.73–0.98 | 0.83 | 0.74–0.93 | 0.84 | 0.69–1.02 | 0.81 | 0.70–0.93 |

| ≥400% FPL | ref | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ||||||

| Insurance status | ||||||||||||

| Public only | 0.95 | 0.86–1.06 | 1.09 | 0.95–1.25 | 1.03 | 0.88–1.19 | 1.11 | 0.95–1.30 | 1.08 | 0.94–1.23 | 1.10 | 0.92–1.31 |

| Private only | ref | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ||||||

| Private and public | 1.12 | 1.01–1.25 | 1.15 | 0.99–1.34 | 1.20 | 1.01–1.42 | 1.24 | 1.05–1.46 | 1.19 | 0.94–1.50 | 1.11 | 0.91–1.35 |

| Insurance type unspecified† | 0.83 | 0.53–1.30 | 1.05 | 0.77–1.44 | 0.66 | 0.38–1.14 | 0.89 | 0.43–1.11 | 0.97 | 0.55–1.68 | 1.05 | 0.63–1.77 |

| Not insured | 0.92 | 0.71–1.19 | 1.05 | 0.86–1.30 | 0.82 | 0.56–1.21 | 0.87 | 0.65–1.15 | 1.11 | 0.83–1.47 | 1.01 | 0.73–1.38 |

| Rural/urban location‡ | ||||||||||||

| Not in CBSA | 0.82 | 0.65–1.04 | 0.93 | 0.79–1.10 | 0.94 | 0.76–1.17 | 1.02 | 0.85–1.23 | 0.99 | 0.79–1.23 | 1.01 | 0.81–1.27 |

| Micropolitan Statistical Area | 0.88 | 0.73–1.06 | 0.93 | 0.81–1.08 | 0.97 | 0.82–1.14 | 0.90 | 0.76–1.06 | 0.97 | 0.81–1.18 | 1.01 | 0.84–1.20 |

| Metropolitan Statistical Area | ref | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ||||||

| Metropolitan Principal City | 1.00 | 0.90–1.11 | 1.01 | 0.92–1.11 | 1.09 | 0.94–1.27 | 1.07 | 0.95–1.19 | 1.10 | 0.95–1.28 | 1.09 | 0.95–1.24 |

| Health characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Severity of diagnosed condition | ||||||||||||

| Mild | ref | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ||||||

| Moderate | 1.06 | 0.95–1.18 | 1.04 | 0.95–1.14 | 1.39 | 1.21–1.60 | 1.27 | 1.14–1.43 | 1.22 | 1.05–1.43 | 1.13 | 0.99–1.28 |

| Severe | 1.19 | 1.05–1.35 | 1.17 | 1.05–1.29 | 1.54 | 1.31–1.81 | 1.23 | 1.02–1.48 | 1.78 | 1.53–2.07 | 1.50 | 1.26–1.80 |

| Current depression | NA | 1.67 | 1.50–1.87 | 1.56 | 1.40–1.74 | 1.85 | 1.67–2.06 | 1.60 | 1.40–1.83 | |||

| Current anxiety | 1.22 | 1.06–1.40 | 1.12 | 1.00–1.25 | NA | 1.78 | 1.56–2.02 | 1.42 | 1.26–1.61 | |||

| Current behavioral or conduct | 1.16 | 1.05–1.28 | 1.21 | 1.09–1.33 | 1.45 | 1.28–1.64 | 1.33 | 1.19–1.48 | N/A | |||

| problem | ||||||||||||

| Child’s health | ||||||||||||

| Excellent or very good | ref | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ||||||

| Good | 1.01 | 0.91–1.12 | 0.96 | 0.87–1.06 | 1.00 | 0.83–1.21 | 0.93 | 0.80–1.07 | 1.10 | 0.93–1.31 | 0.90 | 0.77–1.06 |

| Fair or poor | 1.03 | 0.86–1.22 | 1.04 | 0.91–1.20 | 1.06 | 0.85–1.33 | 0.87 | 0.67–1.13 | 1.16 | 0.92–1.47 | 0.80 | 0.60–1.06 |

| Respondent’s mental or emotional | ||||||||||||

| health | ||||||||||||

| Excellent or very good | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Good | 1.05 | 0.95–1.16 | 1.06 | 0.96–1.16 | 1.12 | 0.99–1.27 | 1.00 | 0.90–1.11 | 1.12 | 0.97–1.30 | 1.04 | 0.92–1.17 |

| Fair or poor | 0.86 | 0.73–1.01 | 0.91 | 0.79–1.04 | 1.02 | 0.82–1.28 | 0.96 | 0.80–1.16 | 1.22 | 0.99–1.51 | 1.05 | 0.84–1.30 |

Bold values are statistically significant results.

Adjusted for all variables above.

Includes children who were reported to have current insurance, but did not specify coverage type from a list of 5 types or provide an interpretable write-in.

Based on the combination of 3 separate geographical identifiers: CBSA, Metropolitan Statistical Area, and Metropolitan Principal City.

Discussion

Using the most recent nationally representative data from the redesigned NSCH, our findings affirm that depression, anxiety problems, and behavioral/conduct problems remain common among children and extend what is known about the prevalence among children as well as subpopulations in whom treatment gaps persist. Consistent with existing epidemiologic studies, behavioral or conduct problems were more common in boys than in girls, and both anxiety and behavioral/ conduct problems were more common than depression.15,16 Regarding comorbid mental disorders, we found that nearly 3 in 4 children with depression had concurrent anxiety, whereas 1 in 3 children with anxiety had concurrent depression. These disorders share a common etiology, and longitudinal studies have identified childhood anxiety as a risk factor for developing depression.17,18 The data also highlight significant associations between childhood mental disorders and children’s overall health, as well as parents/caregivers’ mental and emotional health.

The prevalence estimates for both anxiety and behavior/ conduct problems in this study were higher than those reported previously from other surveys.2,19,20 For example, prevalence estimates based on data from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey (an in-person survey) and the 2011–2012 NSCH (a telephone survey) were only one-half those reported herein, although estimates for depression were comparable. Differences in data collection mode and questionnaire wording may explain some of the differences; for example, the inclusion of behavioral/conduct diagnoses by educators in the present study might have affected prevalence estimates, particularly for mild/moderate cases.

This study highlights differences in the receipt of treatment among those with each of these disorders. Treatment guidelines, particularly regarding prescription medication, for children with mental disorders are more firmly established for depression than for anxiety and behavioral/conduct problems.21,22 In addition, anxiety and behavioral/conduct problems can sometimes be addressed in primary or educational settings, focusing on parenting behavior and behavioral management strategies rather than on direct provision of treatment to the child.23 These differences, along with identification of condition severity, co-occurrence of disorders, and higher household income as the main predictors of treatment receipt, highlight the complexity of treatment provision and utilization for children with mental disorders.

Although children’s overall health and parents/caregivers’ mental and emotional health were related to disorder prevalence, these health-related factors were not significantly associated with receipt of treatment. These findings are consistent with the literature24–27 documenting a greater risk of mental health problems among children with parents with a mental health problem, which maybe due to shared genetic and biological predispositions as well as with environmental factors and the parent-child relationship. Although most research suggests that caregivers’ mental health status can impact children’s mental health, it is possible that bidirectional effects also may occur wherein a child’s mental and behavioral health may impact that of their parents/caregivers. On the other hand, treatment utilization in children might be directly associated not with the parents’ mental health, but rather with structural constraints and barriers associated with the parents’ perceptions of mental health problems and services,28 perhaps benefiting from their own treatment utilization.29 Future research is needed to explore types of treatments received beyond the specialty mental health services described herein, settings in which those services are received, and related barriers and facilitating factors associated with treatment access and utilization.

The finding that after adjustment, children from low- income families were less likely to be diagnosed and treated for mental disorders is notable given previous research from various disciplines demonstrating the wide-ranging negative effects of poverty on mental and emotional health in children (and adults).30 Our results likely reflect the use of a measure of diagnosed mental health conditions, which by definition suggests access to a provider who is able to make such a determination. In fact, we found that irrespective of disorder, children from poor households were less likely to receive treatment from a mental health professional. Care for pediatric depression, anxiety, and behavioral/conduct problems is commonly sought in pediatric primary care settings,31,32 and low-income parents may be more likely to seek care in such settings. The NSCH items do not capture data regarding such treatment. In previous studies, providers in these settings have reported several barriers to the provision of this care, including a lack of training in treating child behavioral health problems and a lack of confidence in treating children who need counseling.33 Even with training, pediatricians frequently report challenges in providing access to behavioral health care in these settings.34

Finally, consistent with previous research,2,13,35 we noted significant differences in the likelihood of both diagnoses and receipt of related treatment by race and ethnicity that we attribute to a combination of factors, including access to care, resiliency, and the potential for diagnostic bias. Limitations in the access to care more broadly among Hispanic and African American children may suggest that these children are less likely to be seen by health providers and diagnosed with the conditions examined in this study.36 On the other hand, resiliency factors, such as family closeness, may protect these youth from other risk factors associated with these diagnoses.37 Furthermore, racial and ethnic inequities in diagnosis, such as bias related to conduct problems, also may help explain the higher prevalence of behavioral/conduct problems among African American children.38

Several limitations of the data should be noted. First, data on both diagnoses and treatment are based on parent/caregiver report and maybe subject to recall bias. However, research has shown good agreement between parental report and clinical records in a range of both past-year and lifetime diagnoses and health events.39 In addition, Kentgen et al found high test-retest reliability for maternal reports of diagnosed mental health conditions among their children,40 suggesting that parents’ reports of diagnoses may be less problematic. Second, the wording of survey items differed among the 3 disorders, thereby limiting comparability, because parents might have interpreted questions about anxiety and behavior/conduct “problems” differently than those about depression that did not include this qualifier. Third, detailed information about the setting, type, or duration of treatment or counseling was not reported, and thus estimates may vary depending on parents’ perceptions of the types of services received. In addition, we are unable to examine whether the care that children are receiving is consistent with evidence-based recommendations for each of these disorders. Finally, the weighted response rate for the survey was 40.7%, which may have resulted in nonresponse bias; however, nonresponse bias analyses suggest that the application of survey weights to these analyses attenuated resulting bias.41

This study provides the latest nationally representative estimates of both multiple diagnosed mental disorders and receipt of related treatment across the US pediatric population. Depression, anxiety, and behavioral/conduct problems remain prevalent among US children, although significant disparities persist with respect to receipt of related treatment. Future research to better understand the factors associated with and implications of observed differences in treatment receipt by condition could inform programmatic opportunities to support diagnostic and treatment services.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the US Department of Health and Human Services, the Health Resources and Services Administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, nor does mention of the department or agency names imply endorsement by the US government.

Glossary

- aPR

Adjusted prevalence ratio

- FPL

Federal poverty level

- NSCH

National Survey of Children’s Health

- PR

Prevalence ratio

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.O’Connell ME, Boat T, Warner KE. eds. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: progress and possibilities. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perou R, Bitsko RH, Blumberg SJ, Pastor P, Ghandour RM, Gfroerer JC, et al. Mental health surveillance among children—United States, 2005–2011. MMWR Suppl 2013;62:1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soni A The five most costly children’s conditions, 2006: estimates for the US civilian noninstitutionalized children, ages 0–17. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality statistical brief #242; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merikangas KR, He JP, Brody D, Fisher PW, Bourdon K, Koretz DS. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001–2004 NHANES. Pediatrics 2010;125:75–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon AE, Pastor PN, Reuben CA, Huang LN, Goldstrom ID. Use of mental health services by children ages 6 to 11 with emotional or behavioral difficulties. Psychiatr Serv 2015;66:930–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Han B. National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics 2016;138:e20161878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication—Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A).J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;49:980–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ali MM, Teich J, Lynch S, Mutter R. Utilization of mental health services by preschool-aged children with private insurance coverage. Adm Policy Ment Health 2018;45:731–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sultan RS, Correll CU, Schoenbaum M, King M, Walkup JT, Olfson M. National patterns of commonly prescribed psychotropic medications to young people. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2018;28:158–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghandour RM, Jones JR, Lebrun-Harris LA, Minnaert J, Blumberg SJ, Fields J, et al. The design and implementation of the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health. Matern Child Health J 2018;22:1093–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department ofHealth and Human Services. Fre- quentlyasked questions: 2016 National Surveyof Children’s Health; Washington (DC); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Census Bureau. 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health: methodology report. Washington (DC): US Census Bureau; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghandour RM, Kogan MD, Blumberg SJ, Jones JR, Perrin JM. Mental health conditions among school-aged children: geographic and sociodemographic patterns in prevalence and treatment. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2012;33:42–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bieler GS, Brown GG, Williams RL, Brogan DJ. Estimating model- adjusted risks, risk differences, and risk ratios from complex survey data. Am J Epidemiol 2010;171:618–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beesdo-Baum K, Knappe S. Developmental epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2012;21:457–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zahn-Waxler C, Shirtcliff EA, Marceau K Disorders of childhood and ado¬lescence: gender and psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2008;4:275–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merikangas KR, Avenevoli S. Epidemiology of mood and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents In: Tsaung MT, Tohen M, eds. Text-book in psychiatric epidemiology. New York (NY): Wiley-Liss; 2002, p. 657–704. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Axelson DA, Birmaher B. Relationship between anxiety and depressive disorders in childhood and adolescence. Depress Anxiety 2001;14:67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Visser SN, Deubler EL, Bitsko RH, Holbrook JR, Danielson ML. Demographic differences among a national sample of US youth with behavioral disorders. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2016;55:1358–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. Data resource center for child and adolescent health. Available at: www.childhealthdata.org Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 21.Higa-McMillan CK, Francis SE, Rith-Najarian L, Chorpita BF. Evidence base update: 50 years of research on treatment for child and adolescent anxiety. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2016;45:91–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z, Whiteside SPH, Sim L, Farah W, Morrow AS, Alsawas M, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of cognitive behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy for childhood anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171:1049–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheung AH, Kozloff N, Sacks D. Pediatric depression: an evidence-based update on treatment interventions. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2013;15:381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennett AC, Brewer KC, Rankin KM. The association of child mental health conditions and parent mental health status among US children, 2007. Matern Child Health J 2012;16:1266–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Connell AM, Goodman SH. The association between psychopathology in fathers versus mothers and children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2002;128:746–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lieb R, Isensee B, Hofler M, Pfister H, Wittchen HU. Parental major depression and the risk of depression and other mental disorders in off-spring: a prospective-longitudinal community study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:365–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manning C, Gregoire A. Effects of parental mental illness on children. Psychiatry 2009;8:7–9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Owens PL, Hoagwood K, Horwitz SM, Leaf PJ, Poduska JM, Kellam SG, et al. Barriers to children’s mental health services. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002;41:731–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sherman LJ, Ali MM. Mothers’ mental health treatment associated with greater adolescent mental health service use for depression. J Child Fam Stud 2017;26:2762–71. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hodgkinson S, Godoy L, Beers LS, Lewin A. Improving mental health access for low-income children and families in the primary care setting. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20151175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olfson M, Blanco C, Wang S, Laje G, Correll CU. National trends in the mental health care of children, adolescents, and adults by office-based physicians. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71:81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olfson M, Druss BG, Marcus SC. Trends in mental health care among children and adolescents. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2029–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horwitz SM, Storfer-Isser A, Kerker BD, Szilagyi M, Garner A, O’Connor KG, et al. Barriers to the identification and management of psychosocial problems: changes from 2004 to 2013. Acad Pediatr 2015;15:613–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cama S, Malowney M, Smith AJB, Spottswood M, Cheng E, Ostrowsky L, et al. Availability of outpatient mental health care by pediatricians and child psychiatrists in five US cities. Int J Health Serv 2017;47:621–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marrast L, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Racial and ethnic disparities in mental health care for children and young adults: a national study. Int J Health Serv 2016;46:810–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang TF, Shi L, Nie X, Zhu J. Race/ethnicity, insurance, income and access to care: the influence of health status. Int J Equity Health 2013;12:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Donnell L, O’Donnell C, Wardlaw DM, Stueve A. Risk and resiliency factors influencing suicidality among urban African American and Latino youth. Am J Community Psychol 2004;33:37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mizock L, Harkins D. Diagnostic bias and conduct disorder: improving culturally sensitive diagnosis. Child Youth Serv 2011;32:243–53. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pless CE, Pless IB. How well they remember: the accuracy of parent reports. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995;149:53–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kentgen LM, Klein RG, Mannuzza S, Davies M. Test-retest reliability of maternal reports of lifetime mental disorders in their children. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1997;25:389–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.U.S. Census Bureau. 2016 national surveyofchildren’s health: nonresponse bias analysis. Washington (DC); 2017.