Abstract

Objective:

To assess the performance of an adapted American Diabetes Association (ADA) risk score and the concise Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINRISC) for predicting type 2 diabetes development in women with and at risk of HIV infection.

Design:

Longitudinal analysis of the Women’s Interagency HIV Study.

Methods:

The women’s Interagency HIV Study is an ongoing prospective cohort study of women with and at risk for HIV infection. Women without prevalent diabetes and 3- year data on fasting blood glucose, hemoglobin A1c, self-reported diabetes medication use, and self-reported diabetes were included. ADA and FINRISC scores were computed at baseline and their ability to predict diabetes development within 3 years was assessed [sensitivity, specificity and area under the receiver operating characteristics (AUROC) curve].

Results:

1111 HIV-positive (median age 41, 60% African American) and 454 HIV-negative women (median age 38, 63% African American) were included. ADA sensitivity did not differ between HIV-positive (77%) and HIV-negative women (81%), while specificity was better in HIV-negative women (42% vs. 49%, p=0.006). Overall ADA discrimination was suboptimal in both HIV-positive (AUROC=0.64 [95% CI: 0.58, 0.70]) and HIV-negative women (AUROC=0.67 [95% CI: 0.57, 0.77]). FINRISC sensitivity and specificity did not differ between HIV-positive (72% and 49%, respectively) and HIV-negative women (86% and 52%, respectively). Overall FINRISC discrimination was suboptimal in HIV-positive (AUROC=0.68 [95% CI: 0.62, 0.75]) and HIV-negative women (AUROC=0.78 [95% CI: 0.66, 0.90]).

Conclusions:

Model performance was suboptimal in women with and at risk of HIV, while greater misclassification was generally observed among HIV-positive women. HIV-specific risk factors known to contribute to diabetes risk should be explored in these models.

Keywords: Screening, HIV, Risk Analysis, Epidemiology, Women’s Healthcare

INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes is a common comorbidity in people living with HIV (PLWH) in the US, possibly fueling the increased risk of cardiovascular and renal disease and mortality this population is facing [1–3]. PLWH in the US are 2–4 times more likely to develop diabetes than their HIV-negative counterparts [4, 5], and have a national diabetes prevalence 4% higher than the general adult population [6]. The increased diabetes risk PLWH face has been linked to chronic inflammation, medication-induced dysglycemia, and immunosuppression [7–11]. Furthermore, traditional diabetes risk factors such as older age, minority race, and obesity have been found to have a stronger effect on diabetes risk among HIV-positive than HIV-negative persons [1]. There are 1.2 million PLWH in the US [12] and those at increased diabetes risk should be identified and treated appropriately to potentially prevent diabetes and its complications.

To minimize the harms of inappropriate glucose testing (e.g., costs, anxiety), expert groups recommend a two-stage diabetes risk screening approach – non-invasive risk assessment followed by glucose testing [13, 14]. This approach involves using non-invasive risk scores such as the American Diabetes Association (ADA) diabetes risk score [15] or the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINRISC) [16] to identify those who should be offered diagnostic glucose testing. In the general population, the ADA and FINRISC scores have been found to be effective and practical tools for identifying people with dysglycemia in clinical practice [17–21].

The ADA and FINRISC scores should be tested among PLWH to determine if they are effective diabetes risk screening tools in the setting of HIV infection. Although a recent cross-sectional study tested FINRISC among PLWH, the study did not include an HIV-negative sample for comparing tool performance [22]. Efforts have also been directed towards developing an HIV-specific diabetes risk equation [23] but a practical scoring system has not been developed. It remains unknown what risk score would most accurately identify PLWH at risk for diabetes. Thus, we aimed to assess and compare the performance of the ADA and FINRISC diabetes risk scores in a longitudinal cohort study of HIV-positive and HIV-negative women.

METHODS

Study design and population

This was a longitudinal analysis of the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS). WIHS is an ongoing multicentre prospective cohort study established in 1994 to investigate the progression of HIV in women with and at risk for HIV infection [24]. A total of 4982 women (3678 HIV-positive and 1304 HIV-negative) were enrolled in four waves: 1994–1995 (n=2623), 2001–2002 (n=1143), 2011–2013 (n=371), or 2013–2015 (n=845) from 11 US cities (Atlanta, Birmingham, Bronx, Brooklyn, Chapel Hill, Chicago, Jackson, Los Angeles, Miami, San Francisco, and Washington DC). Every six months, WIHS participants complete a comprehensive physical examination, provide biological specimens for blood testing, and complete an interviewer-administered questionnaire, which collects information on demographics, disease characteristics, and specific antiretroviral therapy (ART) use. The WIHS study protocol and consent forms have been approved by the Institutional Review Board at each study site, and all participants have provided written informed consent.

Hemoglobin A1c (A1c) and fasting blood glucose (FBG) testing were first introduced in WIHS in October 2000. At each semi-annual visit, participants are asked if they use any anti-diabetic medication and if they had been told they have diabetes. The index visit was defined as the first visit at which FBG, A1c, self-reported antidiabetic medication use, and self-reported diabetes data were available. Participants with prevalent diabetes (defined as FBG ≥126 mg/dL or A1c ≥6.5% at the index visit; or self-reported anti-diabetic medication use or self-reported diabetes before or at the index visit) were excluded. To be included in our analysis, participants had to have data on FBG, A1c, self-reported anti-diabetic medication use, and self-reported diabetes at least once annually for three years after the index visit.

Exposures and outcome

Race, age, body mass index (BMI), and self-reported health insurance status were compared between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women at the index visit. Prediabetes prevalence, defined as either FBG of 100 to 125 mg/dL or A1c of 5.7% to 6.4%, was also compared at the index visit. In HIV-positive women, we calculated the prevalence of stavudine use, ritonavir use or any protease inhibitor use as of the index visit since these HIV medications have been linked to increased diabetes risk [4, 10]. Undetectable HIV RNA was defined as HIV-1 RNA <80 copies/mL at index visit.

The exposures of interest were ADA and FINRISC diabetes risk scores. The risk scores included the following variables: age, BMI (weight [kg]/height2 [meters]), waist circumference (measured in standing position using standardised procedures) [25], history of hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg or self-reported hypertension or as self-reported anti-hypertension medication use prior to or at index visit), history of hyperglycemia (FBG measure of 100–125 mg/dL at index visit) and family history of diabetes.

The ADA risk score was computed by summing the risk points obtained for age (<40 years [0 pts], 40 to <50 years [1 pt], 50 to <60 years [2 pts], ≥60 years [3 pts]), BMI/waist circumference (BMI<25 kg/m2 or waist <31.5 inches [0 pts], BMI 25 to <30 kg/m2 or waist 31.5 to <35 inches [1 pt], BMI 30 to <40 kg/m2 or waist 35.0 to <49 inches [2 pts], BMI ≥40 kg/m2 or waist ≥49 inches [3 pts]), history of hypertension (No [0 pts], Yes [1 pt]), and family history of diabetes (No [0 pts], Yes [1 pt]) [15]. Since all participants were women, sex did not contribute risk points (Male [1 pt], Female [0 pts]). Because WIHS lacks physical activity data, this risk factor was excluded from the ADA model.

The FINRISC score was computed by summing the risk points obtained for age (<45 years [0 pts], 45 to <55 years [2 pts], ≥55 years [3 pts]), BMI (<25 kg/m2 [0 pts], 25 to <30 kg/m2 [1 pt], >30 kg/m2 [3 pts]), waist circumference (<31.5 inches [0 pts], 31.5–34.6 inches [3 pts], >34.6 inches [4 pts]), FBG (<100 mg/dL [0 pts], 100 to <126 mg/dL [5 pts]), and history of hypertension medication use (No [0 pts], Yes [2 pts]) [16]. We used the FINRISC concise model, which excludes physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption [16].

The outcome of interest was incident diabetes, defined as the first time within three years after the index visit at which the participant reported anti-diabetic medication use (confirmed with A1c ≥6.5% or FBG ≥126 mg/dL), FBG ≥126 mg/dL (confirmed with a report of anti-diabetic medication use or a second FBG measure ≥126 mg/dL or A1c ≥6.5%), or self-report of diabetes (confirmed with a report of anti-diabetic medication use or two FBG measures ≥126 mg/dL or concurrent A1c ≥6.5% and FBG ≥126mg/dL) [5].

Statistical Analysis

Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to test for differences between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in demographic and clinical characteristics at the index visit. Pearson Chi-Square tests were used to test for associations between categorical characteristics and HIV status at the index visit.

For each woman, we calculated an ADA and a FINRISC score at index visit and determined whether diabetes developed within three years following the index visit. To categorize women as being at low or high diabetes risk, we chose risk score thresholds (low risk, high risk) that gave equal weight to sensitivity and specificity. We compared the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of the models between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women using score thresholds selected for this study with two-sample tests of proportions.

We calculated the area under the receiver operating characteristics curves (AUROC) for HIV-positive and HIV-negative women to assess the ability of the models to discriminate those with and without diabetes; values of at least 0.8 were considered indicative of good model discrimination [26]. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated to quantify the precision in the estimated sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and AUROC for HIV-positive and HIV-negative women. Significant differences in receiving operating characteristics (ROC) curves between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women (e.g. ROC1 and ROC2) were determined as follows: .

We compared diabetes risk classification (via sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and AUROC) for ADA and FINRISC scores in HIV-positive women at different calendar periods. These were selected based on the years corresponding to early highly active ART [HAART] era (2000–2003) and late HAART era (2010–2013). Specifically, we compared risk score performance between 773 HIV-positive women who had an index visit between October 2000-March 2003 (early HAART era) and 338 HIV-positive women who had an index visit in the January 2010-January 2013 period (late HAART era). All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4.

RESULTS

From the 1,719 eligible women (1225 HIV-positive and 494 HIV-negative), 1565 (1111 HIV-positive and 454 HIV-positive) had complete data to test the ADA and FINRISC models and were included in analyses (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which presents the sample selection flow diagram). The excluded women (114 HIV-positive and 40 HIV-negative) were younger than those included, while HIV-negative women excluded were more likely to be African American than those included (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which presents demographic data of excluded women by HIV status).

Participant median age was 39.8 years and 61% were African-American. As shown in Table 1, HIV-positive women were on average three years older than HIV-negative women (41 vs. 38 years, P < 0.001). The prevalence of prediabetes was lower in HIV-positive than in HIV-negative women (25% vs. 33%, P = 0.003). More HIV-positive than HIV-negative women reported having health insurance (92% vs. 66%, P < 0.001). Forty-three percent of the HIV-positive women had a history of stavudine use, 24% had a history of ritonavir use, 41% were virally suppressed, and 50% had a median CD4 cell count between 300 and 653 cells/mm3 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics by HIV status (N=1565).

| Characteristics | HIV-positive (n=1111) |

HIV-negative (n=454) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| African-American race (N (%)) Age (years, median (IQR)) BMI (kg/m2, median (IQR)) Health insurance (N (%)) Prediabetes (N (%)) History of stavudine use (N (%)) History of any protease inhibitor use (N (%)) History of ritonavir use (N (%)) CD4 cell count (cells/mm3, median (IQR)) Undetectable HIV RNA (N (%)) |

663 (60) 41 (34, 47) 27 (24, 32) 1022 (92) 283 (25) 478 (43) 597 (54) 269 (24) 463 (300, 653) 455 (41) |

284 (63) 38 (29, 46) 28 (24, 34) 300 (66) 149 (33) NA NA NA 953 (753, 1191) NA |

0.299 <0.001 0.064 <0.001 0.003 NA NA NA <0.001 NA |

NA=not applicable; IQR=interquartile range.

The risk factor prevalence and score distribution for ADA and FINRISC by HIV status are reported in Table 2. The median ADA risk score was 3 for both HIV-positive and negative women, and the median FINRISC score was 6 for both groups. In both models, obesity was the most prevalent risk factor, present in 53% of HIV-positive and 54% of HIV-negative women according to ADA (based on BMI and waist circumference) and in 35% of HIV-positive and of 43% HIV-negative women according to FINRISC (based on BMI). According to ADA, history of hypertension was also common, present in 46% of HIV-positive and 41% of HIV-negative women; this was followed by family history of diabetes, present in nearly 30% of both women groups. Three years after the index visit, 67 (6%) HIV-positive and 23 (5%) HIV-negative women developed diabetes.

Table 2.

Risk Factor Prevalence, Risk Scores, and Diabetes Incidence by HIV status.

| Risk factors included in models | Risk Points | HIV-positive (n=1111) |

HIV-negative (n=454) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADA model Age (N (%)) <40 years 40 to <50 years 50 to <60 years >60 years BMI/Waist circumference (N (%)) <25 kg/m2 or waist <31.5 in 25 to <30 kg/m2 or waist 31.5 to <35 in 30 to <40 kg/m2 or waist 40.0 to <50 in ≥40 kg/m2 or waist ≥50 in History of hypertension (N (%)) No Yes Family history of diabetes (N (%)) No Yes Risk Score (median (IQR))* |

0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 0 1 |

522 (47) 433 (39) 133 (12) 22 (2) 211 (19) 311 (28) 500 (45) 89 (8) 600 (54) 511 (46) 767 (69) 356 (31) 3 (2,4) |

263 (58) 127 (28) 50 (11) 9 (2) 100 (22) 104 (23) 200 (44) 45 (10) 268 (59) 186 (41) 327 (72) 127 (28) 3 (1,4) |

| FINRISC model | |||

| Age (N (%)) <45 years 45 to <55 years 55 to 65 years Body Mass Index (N (%)) <25 kg/m2 25 to <30 kg/m2 >30 kg/m2 Waist circumference (N (%)) <31.5 inches 31.5 to 34.6 inches >34.6 inches Fasting blood glucose (N (%)) <100 mg/dL 100 to <126 mg/dL History of hypertension medication use (N (%)) No Yes Risk Score (median (IQR))a |

0 2 3 0 1 3 0 3 4 0 5 0 2 |

744 (67) 300 (27) 56 (5) 356 (32) 367 (33) 389 (35) 244 (22) 289 (26) 589 (53) 1011 (91) 100 (9) 922 (83) 189 (17) 6 (4, 7) |

336 (74) 86 (19) 32 (7) 141 (31) 123 (27) 195 (43) 118 (26) 100 (22) 241 (53) 413 (91) 40 (9) 396 (87) 59 (13) 6 (3, 7) |

| Diabetes within three years, No. (%) |

67 (6) |

23 (5) |

IQR=interquartile range.

Risk score obtained by summing the risk points for all risk factors.

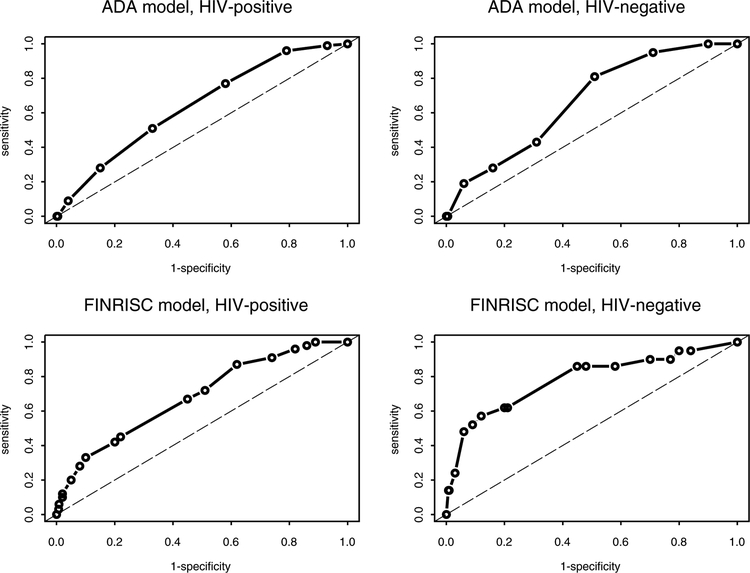

To evaluate ADA model performance, the sensitivity and specificity of all possible risk score cutoffs were explored by HIV status (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3A, which presents sensitivity and specificity values for all ADA score cutoffs). The score cutoff ADA uses to indicate high diabetes risk (≥5) had a poor sensitivity (28%) in both HIV-positive and HIV-negative women. A score of ≥3 was deemed the best performing for identifying high-risk HIV-positive (sensitivity=77%, specificity=42%) and HIV-negative (sensitivity=81%, specificity=49%) women in this study (see ROC curves in Figure 1). Using this cutoff, the ADA model classified 60% of HIV-positive and 52% of HIV-negative women as having high diabetes risk (Table 3). ADA model discrimination was suboptimal in both HIV-positive (AUROC=0.64 [0.58, 0.70]) and HIV-negative women (AUROC=0.67 [0.57, 0.77]).

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristics curves for ADA and FINRISC models by HIV status.

Table 3.

Risk Model Performance Assessment by HIV status.

| ADA modela | FINRISC modelc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-positive (N=1111) |

HIV-negative (N=454) | P value | HIV-positive (N=1111) |

HIV-negative (N=454) |

P value | |

| Diabetes risk (N (%))b Low risk High risk |

450 (40) 661 (60) |

218 (48) 236 (52) |

0.006 |

533 (48) 578 (52) |

227 (50) 227 (50) |

0.517 |

| Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | 77 (67, 87) | 81 (64, 98) | 0.774 | 72 (62, 83) | 86 (71, 100) | 0.217 |

| Specificity, % (95% CI) | 42 (39, 45) | 49 (45, 54) | 0.006 | 49 (46, 52) | 52 (47, 56) | 0.447 |

| PPV, % (95% CI) | 8 (6, 10) | 7 (4, 10) | 0.689 | 9 (6, 11) | 8 (4, 11) | 0.728 |

| NPV, % (95% CI) | 96 (95, 98) | 98 (96, 100) | 0.221 | 96 (95, 98) | 99 (97, 100) | 0.093 |

| AUROC (95% CI) | 0.64 (0.58, 0.70) | 0.67 (0.57, 0.77) | 0.597 | 0.68 (0.62, 0.75) | 0.78 (0.66, 0.90) | 0.141 |

PPV=positive predictive value; NPV=negative predictive value; AUROC=area under the receiver operating characteristics curve; CI=confidence interval.

Values obtained using a score cutoff of ≥3 for both HIV-positive and HIV-negative participants.

Low risk participants were those achieving a score of <3 for ADA and <6 for FINRISC. High risk participants were those achieving a score of ≥3 for ADA and ≥6 for FINRISC.

Values obtained using a score cutoff of ≥6 for both HIV-positive and HIV-negative participants

The sensitivity and specificity of all possible FINRISC score cutoffs were also explored by HIV status (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3B, which presents sensitivity and specificity values for all FINRISC score cutoffs). The score cutoff FINRISC uses to indicate high diabetes risk (≥9) had a suboptimal sensitivity in HIV-positive (42%) and HIV-negative women (62%). A score of ≥6 was deemed the best performing for identifying high-risk HIV-positive (sensitivity=72%, specificity=49%) and HIV-negative (sensitivity=86%, specificity=52%) women in this study (see ROC curves in Figure 1). Using this cutoff, the FINRISC model classified 52% of HIV-positive and 50% of HIV-negative women as having high diabetes risk (Table 3). FINRISC model discrimination was suboptimal in both HIV-positive (AUROC=0.68 [0.62, 0.75]) and HIV-negative women (AUROC=0.78 [0.66, 0.90]).

Among the 1111 HIV-positive women, we found ADA and FINRISC model performance differed according to period of index visit (Table 4). For the ADA model, the specificity was better among women whose index visit was in 2000–2003 than among those whose index visit was in 2010–2013 (47% and 29%, respectively). The positive predictive value was also better among women whose index visit was in 2000–2003 than among those whose index visit was in 2010–2013 (10% and 5%, respectively). For the FINRISC model, the specificity of the model was better among women whose index visit was in 2000–2003 than among those whose index visit was in 2010–2013 (55% and 36%, respectively).

Table 4.

Risk prediction model performance assessment of 1111 HIV-positive women by date of index visit.

| ADA modela | FINRISC modelb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index visitc 10/00–4/03 (n=773) |

Index

visit 10/10–3/13 (n=338) |

P value |

Index

visit 10/00–4/03 (n=773) |

Index

visit 10/10–3/13 (n=338) |

P value |

|

| Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | 75 (63, 86) | 86 (67, 100) | 0.494 | 67 (55, 80) | 93 (79, 100) | 0.091 |

| Specificity, % (95% CI) | 47 (44, 51) | 29 (24, 34) | <0.001 | 55 (52, 59) | 36 (31, 41) | <0.001 |

| PPV, % (95% CI) | 10 (7, 13) | 5 (2, 8) | 0.026 | 10 (7, 14) | 6 (3, 9) | 0.063 |

| NPV, % (95% CI) | 96 (94, 98) | 98 (93, 100) | 0.541 | 96 (94, 98) | 99 (97, 100) | 0.091 |

| AUROC (95% CI) | 0.66 (0.59, 0.73) | 0.63 (0.48, 0.78) | 0.677 | 0.69 (0.62, 0.76) | 0.74 (0.62, 0.87) | 0.456 |

PPV= predictive value; NPV= negative predictive value; CI=confidence interval.

Values obtained using a score cutoff of ≥3

Values obtained using a score cutoff of ≥6

We refer to the first visit at which fasting blood glucose, hemoglobin A1c, self-reported antidiabetic medication use, and self-reported diabetes data were available as the index visit. Time frames were selected based on the years corresponding to early highly active antiretroviral therapy [HAART] era (2000–2003) and late HAART era (2010–2013).

DISCUSSION

Early identification of PLWH at risk for diabetes can facilitate prompt initiation of preventive measures to forestall the development of diabetes and its complications. To inform such efforts, we assessed the performance of the concise FINRISC model and an adapted ADA model in a predominantly minority population of HIV-positive and HIV-negative women. Our assessment showed that performances of the concise FINRISC and adapted ADA models were broadly similar among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women. However, model performance was suboptimal in both groups, while greater misclassification was generally observed among HIV-positive women. Exploring the contribution of HIV-specific risk factors in these models could unmask performance differences and could improve risk classification in HIV-positive women.

At baseline, HIV-positive women had a lower prediabetes prevalence than HIV-negative women (25% vs. 33%); yet, a similar proportion of HIV-positive and negative women developed diabetes within three years (6% and 5%, respectively). This may be an early signal that PLWH could be moving from prediabetes to diabetes faster than HIV-negative populations. We also observed an annual diabetes incidence of ~2%, which is higher than the ~1% annual incidence observed in the US general population [27]. This is likely because over half of WIHS women have overweight or obesity compared to the 38% obesity prevalence reported in the general population [28]. Overall, HIV-positive women have a high prevalence of diabetes risk factors and may develop the disease faster than HIV-negative women.

The sensitivity (77–81%) and specificity (42–49%) of the adapted ADA model observed in this study differ from the sensitivity (89–98%) and specificity (4–40%) observed in the US general population [17]. Differences in populations, risk score cutoffs, and in risk factors included in the models (e.g. physical activity, race and dyslipidaemia) may explain these differences. The sensitivity (72–86%) and specificity (49–52%) of the concise FINRISC model observed in this study were similar to the sensitivity (79%) and specificity (49%) observed in the US general population [18]. Regarding FINRISC performance in HIV-positive populations, the model has been found to be more specific (90%) and sensitive (65%) among HIV-positive individuals from London [22] than among WIHS women in this study. In addition to population characteristics, these differences could be related to the different score cutoffs we used to improve model discrimination and the different observation periods and models tested (i.e. FINRISC concise vs. full).

The performance of the adapted ADA and the concise FINRISC models did not significantly differ between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women. However, a greater percentage of HIV-positive than negative women were misclassified as having (lower specificity) or not having diabetes (lower sensitivity). It is possible that misclassification occurred more often in HIV-positive women due to HIV-related factors that are not measured in these models. Indeed diabetes risk classification has been found to be better among HIV-positive individuals when HIV-specific risk factors are included [22]. Inclusion of HIV-specific risk factors such as CD4 cell count could potentially unmask differences in the performance of these tools and improve risk classification among HIV-positive women.

Identifying asymptomatic persons with dysglycemia through targeted screening in healthcare settings has been recommended by numerous organizations [14, 29, 30]. Though HIV clinical guidelines mirror these screening recommendations [31], risk management in HIV-positive populations has fallen below the recommended standards [32]. This is compounded by the lack of HIV-specific risk screening tools [32]. Diabetes risk screening in HIV care can help estimate, communicate and monitor risk to motivate adherence to lifestyle change or therapies, and to allocate scarce prevention resources and strategies appropriately [32]. For this, a high performing, practical risk screening tool to conduct targeted glucose testing in HIV care is needed.

These findings should be interpreted in light of the study limitations. First, we did not include men in this analysis, which limits conclusions about the performance of these tools in HIV-positive populations to women only. Second, since physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption data was not complete in WIHS, we excluded physical activity from the ADA model and used the concise FINRISC model. Third, this analysis focused on diabetes as the outcome and did not explore dysglycemia at-large (i.e. prediabetes and diabetes). Finally, we only explored diabetes risk over three years, which does not correspond with the time period FINRISC assesses (i.e. 10-year diabetes risk). The analysis may also be limited due to the small number of diabetes cases we could detect and to the lack of score validation over a shorter time interval.

Diabetes is an increasingly important co-morbidity in PLWH. Diabetes risk screening in HIV care can help estimate, communicate and monitor risk to motivate adherence to lifestyle change or therapies, and to allocate scarce prevention resources and strategies appropriately. To inform such efforts, we assessed the performance of the concise FINRISC model and an adapted ADA model in a predominantly minority population of HIV-positive and HIV-negative women. Our assessment showed that the performance of the models was broadly similar between women with and at risk of HIV, though greater misclassification was generally observed among women with HIV. Inclusion of HIV-specific risk factors known to contribute to diabetes risk may improve identification of HIV-positive individuals at increased diabetes risk. Long-term studies in multi-ethnic, mixed-gender longitudinal cohorts in this area are needed.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1, Figure that presents the sample selection flow diagram. doc

Supplemental Digital Content 2. Table that presents demographic data of excluded women by HIV status. doc

Supplemental Digital Content 3. Table 3A presents sensitivity and specificity values for all ADA score cutoffs. doc. Table 3B presents sensitivity and specificity values for all FINRISC score cutoffs. doc

Acknowledgements

KIG and MKA designed the study, provided guidance for statistical analyses, provided interpretation of study findings, and drafted the manuscript. MFS conducted the statistical analyses, contributed to interpretation of findings, critically revised the manuscript and approved submission. PT, CCM and IO contributed to study design, provided guidance for statistical analyses and study conduction, contributed to interpretation of findings, critically revised the manuscript and approved submission. JC, VM and KP contributed to interpretation of findings, provided guidance for study conduction, critically revised the manuscript and approved submission. GW, AS, DG, DM, RK, MC, AA, MA, and DKP contributed to interpretation of findings, critically revised the manuscript and approved submission.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases through the WIHS (U01AI103408-04). M.K.A. and KIG were partially supported by the Georgia Center for Diabetes Translation Research (P30DK111024).

Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). WIHS (Principal Investigators): UAB-MS WIHS (Mirjam-Colette Kempf and Deborah Konkle-Parker), U01-AI-103401; Atlanta WIHS (Ighovwerha Ofotokun and Gina Wingood), U01-AI-103408; Bronx WIHS (Kathryn Anastos and Anjali Sharma), U01-AI-035004; Brooklyn WIHS (Howard Minkoff and Deborah Gustafson), U01-AI-031834; Chicago WIHS (Mardge Cohen and Audrey French), U01-AI-034993; Metropolitan Washington WIHS (Seble Kassaye), U01-AI-034994; Miami WIHS (Margaret Fischl and Lisa Metsch), U01-AI-103397; UNC WIHS (Adaora Adimora), U01-AI-103390; Connie Wofsy Women’s HIV Study, Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt, Bradley Aouizerat, and Phyllis Tien), U01-AI-034989; WIHS Data Management and Analysis Center (Stephen Gange and Elizabeth Golub), U01-AI-042590; Southern California WIHS (Joel Milam), U01-HD-032632 (WIHS I – WIHS IV). The WIHS is funded primarily by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH). Targeted supplemental funding for specific projects is also provided by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health. WIHS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR000004 (UCSF CTSA), UL1-TR000454 (Atlanta CTSA), and P30-AI-050410 (UNC CFAR).

REFERENCES

- 1.Butt AA, McGinnis K, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Crystal S, Simberkoff M, Goetz MB, et al. HIV Infection and the Risk of Diabetes Mellitus. AIDS 2009; 23(10):1227–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medapalli R, Parikh CR, Gordon K, Brown ST, Butt AA, Gibert CL, et al. Comorbid diabetes and the risk of progressive chronic kidney disease in HIV-infected adults: Data from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 60(4):393–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adih WK, Selik RM, Hu X. Trends in diseases reported on us death certificates that mentioned HIV Infection, 1996–2006. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2011; 10(1):5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown TT, Cole SR, Li X, Kingsley LA, Palella FJ, Riddler SA, et al. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence and incidence of diabetes mellitus in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165(10):1179–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tien PC, Schneider MF, Cox C, Karim R, Cohen M, Sharma A, et al. Association of HIV infection with incident diabetes mellitus: impact of using hemoglobin A1C as a criterion for diabetes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 61(3):334–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernandez-Romieu AC, Garg S, Rosenberg ES, Thompson-Paul AM, Skarbinski J. Is diabetes prevalence higher among HIV-infected individuals compared with the general population? Evidence from MMP and NHANES 2009–2010. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2017; 5(e000304). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butt AA, Fultz SL, Kwoh CK, Kelley D, Skanderson M, Justice AC. Risk of diabetes in HIV infected veterans pre- and post-HAART and the role of HCV coinfection. Hepatology 2004; 40(1):115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salehian B, Bilas J, Bazargan M, Abbasian M. Prevalence and incidence of diabetes in HIV-infected minority patients on protease inhibitors. J Natl Med Assoc 2005; 97(8):1088–1092. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanjay K, Bharti K, Navneet A, Unnikrishnan AG. Understanding diabetes in patients with HIV/AIDS Diabetol Metab Syndr 2011; 3(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Wit S, Sabin CA, Weber R, Worm SW, Reiss P, Cazanave C, et al. Incidence and Risk Factors for New-Onset Diabetes in HIV-Infected Patients: The Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) Study. Diabetes Care 2008; 31(6):1224–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ledergerber B, Furrer H, Rickenbach M, Lehmann R, Elzi L, Hirschel B, et al. Factors Associated with the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in HIV-Infected Participants in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45(1):111–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of Diagnosed and Undiagnosed HIV Infection — United States, 2008–2012. MMWR 2015; 64:657–662. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narayan KMV, Gujral UP. Evidence Tips the Scale Toward Screening for Hyperglycemia. Diabetes Care 2015; 38(8):1399–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2017; 40(1):S1–S135.27979885 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bang H, Edwards AM, Bomback AS, Ballantyne CM, Brillon D, Callahan MA, et al. A patient self-assessment diabetes screening score:: development, validation, and comparison to other diabetes risk assessment scores. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151(11):775–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindström J, Tuomilehto J. The Diabetes Risk Score: A practical tool to predict type 2 diabetes risk. Diabetes Care 2003; 26(3):725–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bullard KM, Ali MK, Imperatore G, Geiss LS, Saydah SH, Albu JB, et al. Receipt of Glucose Testing and Performance of Two US Diabetes Screening Guidelines, 2007–2012. PLoS One 2015; 10(4):e0125249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, Hu G, Zhang L, Mayo R, Chen L. A Novel Testing Model for Opportunistic Screening of Pre-Diabetes and Diabetes among U.S. Adults. PLoS One 2015; 10(3):e0120382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kengne AP, Beulens JW, Peelen LM, Moons KG, van der Schouw YT, Schulze MB, et al. Non-invasive risk scores for prediction of type 2 diabetes (EPIC-InterAct): a validation of existing models. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2(1):19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwarz PE, Li J, Lindstrom J, Tuomilehto J. Tools for predicting the risk of type 2 diabetes in daily practice. Horm Metab Res 2009; 41(2):86–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Hu G, Chen L. Evaluation of Finnish Diabetes Risk Score in Screening Undiagnosed Diabetes and Prediabetes among U.S. Adults by Gender and Race: NHANES 1999–2010. PLoS One 2014; 9(5):e97865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mok J, Goff L, Peters B, Duncan A. Comparison of risk tools to estimate type 2 diabetes risk in an urban HIV cohort. HIV Drug Therapy Conference [Abstract]. J Int AIDS Soc 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petoumenos K, Worm SW, Fontas E, Weber R, De Wit S, Bruyand M, et al. Predicting the short-term risk of diabetes in HIV-positive patients: the Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study. J Int AIDS Soc 2012; 15(2):17426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, Sharp G, Robison E, Hessol N, et al. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2005; 12(9):1013–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Body Measurements (Anthropometry). Rockville, MD:1988. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tape TG. Interpretation of Diagnostic Tests. Available at http://gim.unmc.edu/dxtests/Default.htm Accessed July 18, 2018 In. University of Nebraska Medical Center.

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services; 2017. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics/statistics-report.html Accessed on December 19, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011–2014 NCHS data brief, no 219. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 7th edition. 2015. Available from http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas Accessed on September 25, 2017.

- 30.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Final Recommendation Statement: Abnormal Blood Glucose and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Screening. November 2016. Available at https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/screening-for-abnormal-blood-glucose-and-type-2-diabetes Accessed on November 3, 2017.

- 31.Aberg JA, Gallant JE, Ghanem KG, Emmanuel P, Zingman BS, Horberg MA, et al. Primary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with HIV: 2013 update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters B, Post F, Wierzbicki AS, Phillips A, Power L, Das S, et al. Screening for chronic comorbid diseases in people with HIV: the need for a strategic approach. HIV Med 2013; 14(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1, Figure that presents the sample selection flow diagram. doc

Supplemental Digital Content 2. Table that presents demographic data of excluded women by HIV status. doc

Supplemental Digital Content 3. Table 3A presents sensitivity and specificity values for all ADA score cutoffs. doc. Table 3B presents sensitivity and specificity values for all FINRISC score cutoffs. doc