Abstract

The present study examined a moderated mediation model among 314 Black adolescents aged 13 to 18. The model included general coping strategies (e.g., active, distracting, avoidant and support-seeking strategies) as mediators and racial identity dimensions (racial centrality, private regard, public regard, minority, assimilationist and humanist ideologies) as moderators of the relation between perceived racial discrimination and depressive symptoms. Moderated mediation examined if the relation between perceived racial discrimination and depressive symptoms varied by the mediators and moderators. Results revealed that avoidant coping strategies mediated the relation between perceptions of racial discrimination and depressive symptoms. The results indicated that avoidant coping strategies mediated the relation between perceived racial discrimination and depressive symptoms among youth with high levels of the minority/oppressive ideology.

Keywords: racial discrimination, racial identity, coping strategies, Blacks, adolescents

Moderated Mediation Model

There is burgeoning research suggesting that perceptions of racial discrimination are harmful to African American adolescents’ mental health. Racial discrimination is defined as dominant group members’ actions that have a differential and negative effect on subordinate racial/ethnic groups (Williams, Neighbors & Jackson, 2003). Perceptions of racial discrimination have been linked to lower life satisfaction levels, decreased self-esteem, increased depressive symptoms, as well as increased anger and anxiety among Black adolescents (Seaton, Caldwell, Sellers and Jackson, 2008; Prelow, Danoff-Burg, Swenson & Pulgiano, 2004; Gaylord-Harden & Cunningham, 2009). Longitudinal research suggests that perceptions of racial discrimination have been linked to increased depressive symptoms, conduct problems, and decreased self-esteem as well as low levels of well-being among African American youth (Greene, Way & Pahl, 2006; Brody et al., 2006; Gibbons et al., 2007; Neblett, White, Ford, Philip, Nguyên & Sellers, 2008).

Given the growing research suggesting that racial discrimination is linked to negative outcomes, prior research has examined general coping strategies as mediators and moderators with perceptions of racial discrimination. Coping is defined as “conscious, volitional efforts to regulate emotion, cognition, behavior, physiology, and the environment in response to stressful events or circumstances” (Compas, Connor, Saltzman, Thomsen & Wadsworth, 2001, p. 89). Coping also includes “efforts to manage stressful events, such that coping can include anything that an individual does or thinks, regardless of how well or badly it works” (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984, p. 142). General coping strategies fall into four categories: active, distracting, support-seeking and avoidance (Compas et al., 2001). Active coping is defined as intentional efforts to improve a problem or situation that include behavioral and cognitive actions (Ayers, Sandler, West & Roosa, 1996). Distraction strategies include efforts to distract one from thinking about or engaging a problem situation (Ayers et al., 1996). Support seeking strategies consist of the tendency to use other individuals for emotional or behavioral support for a problem situation (Ayers et al., 1996). Avoidance strategies include the tendency to avoid thinking about or engaging the problem altogether (Ayers et al., 1996). One study examining mediation indicated that greater reports of racial discrimination distress were related to greater use of avoidant coping strategies (Scott & House, 2005). Adolescents who reported more self-control in response to perceptions of racial discrimination were more likely to use active and support seeking coping strategies (Scott & House, 2005). An additional study examined general coping strategies as moderators in the association between perceptions of racial discrimination and internalizing symptoms among African American youth. The results indicated that the general coping strategies did not moderate the association between perceptions of racial discrimination and anxiety and depressive symptoms (Gaylord-Harden & Cunningham, 2009).

In addition to general coping strategies, previous empirical research has also examined racial identity in conjunction with perceptions of racial discrimination among Black youth. Racial identity is defined as the significance and meaning that individuals ascribe to being a member of their racial group (Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley & Chavous, 1998). The bulk of this research has utilized the Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity (MMRI) when examining moderators for perceptions of racial discrimination among African American youth. The MMRI articulates individual differences in the meaning and significance that African Americans ascribe to racial identity content and is comprised of three related dimensions: centrality, regard and ideology (Sellers et al., 1998). Racial centrality refers to the extent to which an individual normatively defines her racial group membership or the significance that individuals place on race. Racial regard refers to individuals’ affective attitudes towards African Americans and is divided into two components: private regard and public regard. Private regard refers to the extent to which an individual feels positively or negatively about being a member of the African American community. Public regard refers to the extent to which an individual feels that the broader society views the African American community positively or negatively. The third dimension, racial ideology, refers to one’s philosophy regarding the ways that African Americans should behave and consists of four components: nationalist, minority, assimilationist and humanist (Sellers et al., 1998). The nationalist ideology emphasizes the uniqueness of being African American, support of African American organizations and preference for African American social environments. The minority ideology emphasizes the similarities between African American’s experiences and those of other oppressed minority groups. An assimilationist ideology emphasizes the similarities between African American and mainstream American society, and the humanist ideology emphasizes the similarities among all people regardless of race or ethnicity. Previous research examining racial identity as a moderator for perceived racial discrimination among African American youth has been mixed. For example, one study reported that the relation between perceptions of racial discrimination and depressive symptoms was non-significant for adolescents who believed that the broader society viewed African Americans negatively, which are akin to low public regard levels (Sellers, Linder, Martin & Lewis, 2006). Yet, one longitudinal study reported that none of the racial identity dimensions (e.g., centrality, regard and ideology) moderated the relation between racial discrimination and psychological well-being over a three year period among African American youth (Seaton, Neblett, Upton, Hammond & Sellers, 2011).

Though sparse, there is a growing literature examining coping strategies and racial identity as mediators and moderators for perceptions of racial discrimination among Black youth. Thus, the current study builds upon previous empirical research with examination of a moderated mediation model which included perceptions of racial discrimination, mediators (general coping strategies) and moderators (racial identity dimensions) simultaneously. In particular, it was of interest to assess if the mediating capacity of coping strategies (e.g., active, distracting, avoidant and support-seeking) was contingent on specific levels of racial identity dimensions (racial centrality, private regard, public regard, minority, assimilationist, nationalist and humanist ideologies) when examining the relation between perceived racial discrimination and depressive symptoms among Black youth. Coping strategies are conceptualized as mediators, which explain how specific relations occur and the racial identity dimensions are conceptualized as moderators, which explain under what conditions specific effects occur (Baron & Kenney, 1986). No hypotheses are offered regarding the moderated mediation model given the lack of prior empirical research examining this research question.

METHOD

Participants

The participants in this study were 314 Black adolescents ranging in age from 13–18. The sample was composed of 105 male (33%) and 209 female (67%) high school students who had an average age of 15.6 (SD = 1.3) years. The adolescents reported their racial/ethnic background as African American (70%), Afro-Latino (14%), Biracial/multiracial (7%), Caribbean Black (5%) or African (3%). When asked about their adult guardian (usually the mother), the participants reported that this person was either married/cohabitating (49%), separated/divorced/widowed (29%), or single/never married (22%). The participants also reported the following educational levels for this particular parent/guardian: less than a high school diploma (5%), high school diploma (23%), one year of college or an associate’s degree (30%), a bachelor’s degree (29%) or a graduate degree (11%).

Procedure

The recruitment process involved two separate methodologies. The initial procedure recruited adolescents from high schools in a southeastern city (N = 149; 48%). Approval was obtained from two school districts and eight schools were selected on the basis of the principals’ willingness to participate in the research study. Participation in the study was granted only if parental consent forms were returned, and the response rate ranged from 10 to 30% per classroom with an average response rate of 20%. The administration of the questionnaires occurred in small groups in the school libraries or unused classrooms. The participants were reminded that their participation was voluntary and that the results from their questionnaire would remain confidential. The interview time ranged from 30 to 60 minutes and upon completion, the participants were compensated $20 and debriefed.

The second procedure employed the use of Facebook to increase the sample (N=165; 52%). A paid advertisement was placed on Facebook that targeted African American youth between the ages of 13 and 18 who lived in the continental United States. The advertisement was run during the peak hours of adolescent consumption, typically Wednesday through Sunday between 3 and 11 PM. An interested adolescent would click on the advertisement and was directed to the initial page in Survey Monkey designed to assess if the adolescent was of African descent. If the adolescent was ineligible, they were ineligible thanked for their time. If the adolescent was eligible, they were asked to provide their residential address. All interested adolescents were mailed a packet that included parental consent forms, information sheets, adolescent assent forms and self-addressed return envelopes. Upon return of the packet, the adolescents were emailed a link for completing the survey in Survey Monkey. All of the adolescents were given a payment preference for iTunes gift cards, Walmart gift cards, Target gift cards or cash.

Measures

Demographic Information.

All adolescents completed questions requesting information about their gender, age, race, ethnicity, grade level, household composition, parental marital status, and parental education level.

The Daily Life Experiences Scale.

The frequency of discriminatory experiences was assessed with the 18-item daily life experiences (DLE) subscale of the Racism and Life Experiences Scale (RaLes) (Seaton, Yip & Sellers, 2009). Participants were presented with a list of experiences and asked to indicate how often it occurred to them in the past year “because you were Black” 0 (never) to 5 (once a week or more) and internal consistency was adequate (α = .94).

Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist (CCSC).

Adolescent coping was assessed using the Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist (Ayers et al., 1996). Participants were asked how often they responded to problems or challenging situations with responses ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (most of the time). The active subscale (α = .89) measures efforts to improve a problem situation, thoughts of ways to improve a problem or focusing on the positive aspects of one’s life to feel better about the problem. The distraction subscale (α = .65) measures efforts to distract one from thinking about a problem or engaging a problem situation. The avoidant subscale (α = .72) measures the intention to avoid thinking about the problem or avoid engaging the problem. The support-seeking subscale (α = .90) measures the use of other people to generation responses to the problem or the use of other people to process the emotions associated with the problem.

The Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity Short (MIBI-S).

A shortened version of the MIBI was utilized to assess racial centrality, racial regard and racial ideology with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) (Martin, Wout, Nguyen, Sellers & Gonzalez, 2013). The MIBI has seven subscales but only six were examined because internal consistency was unreliable for the nationalist subscale. The racial centrality subscale (α = .59) assesses the degree to which being African American is central to the respondents’ definition of themselves. The private regard subscale (α = .81) measures the extent to which respondents feel positive about being African American. The public regard subscale (α = .82) measures the respondents’ belief of how others view African Americans. The minority/oppressive ideology subscale (α = .66) measures the similarities between the oppression that African Americans face and that of other minority groups. The assimilationist ideology subscale (α = .79) measures the degree to which a person endorses the similarities between African Americans and mainstream culture. The humanist ideology subscale (α = .60) measures the degree to which a person emphasizes the humanity in all people with little regard for race, gender, class or other distinguishing characteristics.

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale.

The shortened 12-item version of the CES-D assesses the frequency of depressive symptoms experienced within the past week (Roberts, Lewinshon & Seeley, 1999). In the current study, 5 items were used (α = .78) with responses ranging from 0 (rarely) to 3 (most or all of the time).

RESULTS

Preliminary results using descriptive statistics such as means, standard deviations and zero-order correlations for each of the study variables can be found in Table 1. Initial results suggest that racial discrimination was associated with avoidant coping, racial centrality, public regard and depressive symptoms. The participants recruited on Facebook were from the Western (7%), Midwestern (12%), Northeastern (12%) and Southern (69%) regions of the country. The mean age for the Facebook sample was 16 (SD = 1.1) with more females (76%) than males (24%).

Table 1 -.

Bivariate Correlations among the Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RD | -- | |||||||||||

| ActC | .06 | -- | ||||||||||

| DC | .07 | .38** | -- | |||||||||

| AC | .14* | .56** | .32** | -- | ||||||||

| SS | −.05 | .54** | .40** | .54** | -- | |||||||

| RC | .13* | .13* | .07 | .13* | .03 | -- | ||||||

| PriR | .01 | .12* | .06 | .12* | .05 | .56** | -- | |||||

| PubR | −.28** | .11 | .21** | .11 | .15* | .18** | .32** | -- | ||||

| OM | .08 | .23** | .17** | .23** | .02 | .07 | .12 | .06 | -- | |||

| A | .07 | .35** | .19** | .35** | .12* | .27** | .33** | .05 | .00 | -- | ||

| H | −.04 | .18** | .11 | .18* | .03 | .01 | .14 | .11* | .33** | .46** | -- | |

| DS | .31** | −.00 | .16 | .26** | .08 | −.07 | −.22** | −.13* | .07 | −.09 | −.09 | -- |

| Mean | 1.49 | 2.88 | 2.36 | 2.93 | 2.43 | 4.75 | 5.89 | 3.79 | 4.81 | 5.80 | 5.52 | 12.16 |

| SD | 1.07 | .58 | .53 | .51 | .77 | 1.1 | 1.23 | 1.29 | 1.23 | 1.11 | 1.1 | 6.34 |

Note. RD = Racial Discrimination; ActC = Active Coping; DC = Distracting Coping; AC = Avoidant Coping; SS = Support Seeking; RC = Racial Centrality; PriR = Private Regard; PubR = Public Regard; OM = Oppressive Minority; A = Assimilation; H = Humanist; DS = Depressive Symptoms; SD = Standard Deviation

p<. 05,

p<. 01

Testing Direct Relations

The first model examined whether racial discrimination and any of the coping strategies were related to depressive symptoms while treating depressive symptoms as a latent variable to correct for measurement error. The fit for the model was acceptable according to various fit indices (X2= 46.9, df = 23, X2/df = 2.04, TLI = .94, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .06). The results suggested that participants with racial discrimination experiences were more likely to display depressive symptoms, (B = .16, p < .01), and that participants who used avoidant coping strategies had high levels of depressive symptoms, (B = .31, p < .01). Lastly, individuals who used distraction coping strategies had higher depressive symptoms (B = .16, p <.05), and active coping strategies were inversely related to depressive symptoms (B = −.24, p < .01). Yet based on preliminary results and zero-order correlations, the statistically significant relations between active coping strategies, distraction coping strategies and depressive symptoms were most likely the result of suppression effects. Only avoidant, active, and distraction coping strategies were utilized in subsequent models.

Testing for Mediated Relations

Tests of mediation were performed using 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals based on 5,000 bootstrap samples, while treating depressive symptoms as a latent variable (Preacher, Rucker & Hayes, 2007). The first model examined whether the relation between racial frequency and depressive symptoms was mediated by avoidant coping strategies and the overall fit was adequate (X2 = 25.08, df = 18, X2/df = 1.39, TLI = .98, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .04). The results indicated that avoidant coping partially mediated the relation between racial discrimination and depressive symptoms, where results from Sobel’s test, (z = .02, p<.05) performed in conjunction with the 95% bias-corrected bootstrap CI for the indirect effect, [.01, .03] were both statistically significant at p <.05. Additional models examining active and distracting coping strategies indicated that they did not mediate the relation between racial discrimination and depressive symptoms.

Testing for Moderated Mediation

The last set of analyses used a latent variable modeling framework to examine a moderated mediation model using avoidant coping strategies and the racial identity dimensions, such that depressive symptoms were again treated as a latent or unobserved variable. The interaction terms for racial centrality, private regard and public regard were non-significant but the minority/oppressive, assimilationist and humanist ideologies were identified as potential moderators. Yet, chi-square difference tests of subsequent moderated mediation models showed that the assimilationist and humanist ideologies did not provide significant improvements in model fit when assimilationist and humanist ideologies were treated as moderators, and these results are not reported.

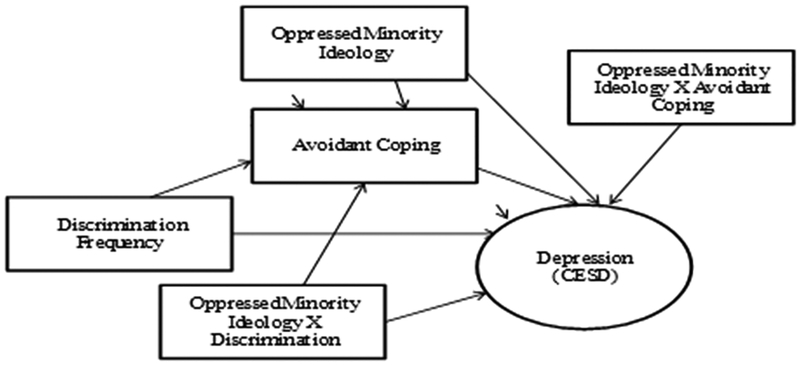

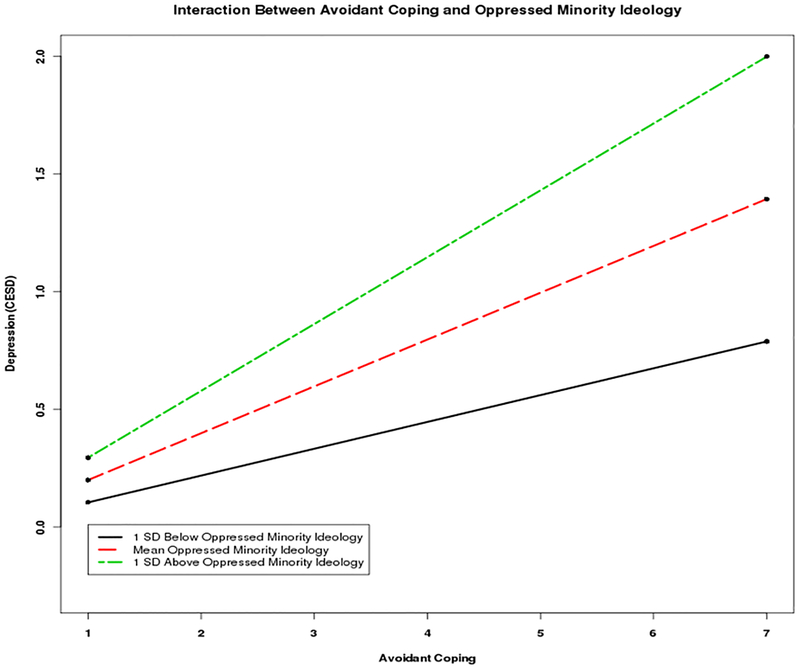

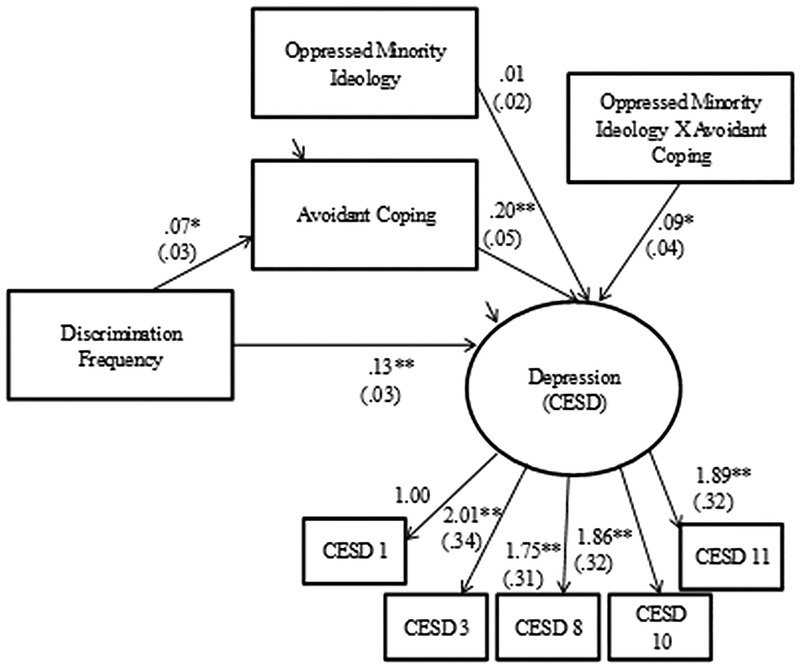

The first model used when testing for moderated mediation evaluated the minority/oppressive ideology as a moderator of the direct and indirect paths between racial discrimination and depressive symptoms (see Figure 1). This assessed whether minority/oppressive ideology moderated the “a path” (e.g., the relation between racial discrimination and avoidant coping), the “b path” (e.g., the relation between avoidant coping and depressive symptoms), or the “c path” (e.g., the direct relation between racial discrimination and depressive symptoms). The results were as follows: (X2 = 57.11, df = 27, X2/df = 2.12, TLI = .93, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .06). The results further indicated that the “b path” or the relation between avoidant coping and depressive symptoms was moderated by minority/oppressive ideology (B =.09, p =.02). This interaction and the simple slopes were probed at the mean, one standard deviation above the mean and one standard deviation below the mean of the oppressed/minority ideology (Preacher, Curran & Bauer, 2006). The results indicated that the use of avoidant coping strategies was more strongly related to depressive symptoms among participants with moderate to high levels of endorsement of minority/oppressive ideology (see Figure 2). An additional model was examined to assess conditional indirect relations while treating avoidant coping as a moderator. The findings (see Figure 3) indicated that the indirect relation between racial discrimination and depressive symptoms through avoidant coping was statistically significant at one standard deviation above the mean of the moderator minority/oppressed ideology [01, .05].

Figure 1.

Moderated Mediation Model for Avoidant Coping Strategies and Oppressed/Minority Ideology

Figure 2.

Interaction of the Relation between Avoidant Coping and Depressive Symptoms for the Oppressed/Minority Ideology

Figure 3.

Moderated Mediation Results for Avoidant Coping and Oppressed/Minority Ideology

DISCUSSION

The results of the moderated mediation model suggest that avoidant coping strategies mediate the influence of experiences of racial discrimination on depressive symptoms for Black youth who espouse moderate to high levels of the minority/oppressive ideology. This ideology emphasizes the similarities between the oppressive experiences of African Americans and other minority groups (Sellers et al., 1998). Is adopting the minority/oppressive ideology linked to the use of avoidant techniques or is the use of avoidant techniques linked to adoption of the minority/oppressive ideology? One mechanism for the racial ideology predicting coping strategy relation concerns racial socialization messages. Previous research suggests that some African American parents engage in racial socialization techniques and an important dimension is preparation for bias (Hughes, Rodriguez, Smith, Johnson, Stevenson & Spicer, 2006). Preparation for bias includes the idea that parents discuss with their children the expectation that they might be treated negatively based on their racial/ethnic group membership (Hughes et al., 2006). Previous research has indicated a relation between specific parental racial socialization techniques and adolescent racial ideologies among African American youth though a significant relation was not found for minority/oppressive ideology (Neblett, Smalls, Ford, Nguyên & Sellers, 2009). Additionally, prior work also suggests that the more racial socialization messages African American youth received, the more self-stigmatized they reported feeling (Brega & Coleman, 1999). The authors did not have statistical power to determine whether specific types of messages (e.g., preparation for bias) were linked to increased stigmatization compared to others (Brega & Coleman, 1999). Consequently, this stigmatization might foster the use of avoidant rather than active coping strategies as Black youth rationalize discriminatory treatment in the context of general oppression, which is akin to the minority/oppressive ideology.

Alternatively, one mechanism for the coping strategy predicting racial ideology concerns the racial context of Black youth. A significant majority of African American youth attends racially segregated high schools and resides in racially segregated neighborhoods (Williams & Collins, 2004; Logan, 2002). It is possible that African American youth gradually develop the use of avoidant techniques in response to racially discriminatory treatment, which might be infrequent given their racial context. Yet, as African American youth age they perceive more incidents of racial discrimination (Seaton et al., 2008) and might begin to interpret these experiences in the context of the minority/oppressive ideology. Racial context might be an important variable to consider in the relation between perceptions of racial discrimination, coping strategies and racial identity. Future research should examine the longitudinal relations among perceptions of racial discrimination, racial ideology and coping strategies among African American youth.

Another significant finding indicates that avoidant coping strategies partially mediate the relation between discrimination frequency and depressive symptoms. One of the main questions raised by the present findings is why avoidant coping strategies are significant, since they appear to enhance the relation between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms. A possible explanation concerns the fact that African American youth may utilize avoidant coping strategies when they perceive problems as beyond their control. Given that prior research reported that Black youth used active and support seeking strategies when they felt in control (Scott & House, 2005), it is possible that lack of control might prompt the use of avoidant coping strategies. Given the unpredictable nature of racial discrimination, Black youth might perceive racially discriminatory treatment as beyond their control and subsequently engage in avoidant behavior. This might be especially likely given the findings from the moderated mediation model regarding the use of avoidant coping strategies in conjunction with the minority/oppressive ideology. It is possible that Black youth recognize oppression as being experienced by multiple minority groups not just African Americans. For this reason, Black youth may view oppressive or racially discriminatory behavior as beyond their control and engage in avoidant coping strategies as a coping mechanism. Future research should examine the full range of coping strategies (e.g., general and racial) used by Black youth in the face of racially discriminatory encounters.

There are a few limitations in the present study that need to be considered. The cross-sectional nature of the study prevents causality and precludes the ability to determine the direction of influence between racial discrimination, depressive symptoms, and avoidant coping. More specifically, the results support the notion that perceived discrimination is linked to depressive symptoms but the reverse relations may also be true. Yet, prior longitudinal research consistently suggests that racial discrimination predicts diminished psychological well-being among African American adolescents (Brody et al., 2006; Gibbons et al., 2007; Greene et al., 2006) rather than diminished psychological well-being predicting perceptions of racial discrimination. An additional limitation concerns the measurement of racial discrimination, which is a critical area for the discrimination literature (see Williams and Mohammed, 2009). The instrument in the present study utilizes an annual time period, but smaller time periods and experiential sampling designs might capture discriminatory experiences more precisely. Lastly, the current research utilized a convenience sample of African American adolescents so the present results may not be generalized to African American youth in other settings.

The current research extends the racial discrimination literature with a simultaneous examination of coping strategies and racial identity dimensions among African American adolescents. The findings suggest that avoidant coping strategies are utilized in the context of the minority/oppressive ideology rather than the other racial identity dimensions. Additionally, Black youth mainly utilize avoidant coping strategies, which are negatively linked to mental health. Yet, the moderated mediation model was not significant for any other general coping strategies or racial identity dimensions. Seemingly, there is a complex relation between racial discrimination, racial identity and coping strategies among Black youth. It is hoped that future research will further illuminate these complex processes during this developmental period.

Author Acknowledgments

This project was partially funded by the generous support of the GlaxoSmithKline Foundation to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Program on Ethnicity, Culture and Health Outcomes (ECHO). We gratefully acknowledge all past and present members of the Racial Experiences of Youth Laboratory (REYLAB) for their assistance with special thanks to Whitney Adams, Tamara Davis, Taylor Hargrove, Chazle’ Lassiter, Denise Mitchell, Paris Scott and Kimberly Williams.

Footnotes

Manuscript in press at Child Development. Do not cite without 1st author’s permission.

Contributor Information

Eleanor K. Seaton, Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Rachel Upton, American Institutes for Research.

Adrianne Gilbert, Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Vanessa Volpe, Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

- Ayers TS, Sandler IN, West SG, & Roosa MW (1996). A dispositional and situational assessment of children’s coping: Testing alternative models of coping. Journal of Personality, 64, 923–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00949.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brega AG, & Coleman LM (1999). Effects of religiosity and racial socialization on subjective stigmatization in African-American adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 22, 223–242. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y, Murry VM, Ge X, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M & Cutrona CE (2006). Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development, 77, 1170–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, & Wadsworth ME (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 87–127. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord-Harden NK & Cunningham JA (2009). The impact of racial discrimination and coping strategies on internalizing symptoms in African American youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 532–543. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9377-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Yeh HC, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Cutrona C, Simons RL & Brody GH (2007). Early experience with racial discrimination and conduct disorder as predictors of subsequent drug use: A critical period hypothesis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88, 27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N & Pahl K (2006). Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology, 42, 218–238. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC & Spicer P (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42, 747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, & Folkman S (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Logan JR (2002). Choosing segregation: Racial imbalance in American public schools, 1990–2000. Albany, NY: Lewis Mumford Center for Comparative Urban and Regional Research. [Google Scholar]

- Martin PP, Wout D, Nguyen H, Sellers RM, & Gonzalez R (2013). Investigating the psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity in two samples: The development of the MIBI-S. Unpublished manuscript.

- Neblett EW, White RL, Ford KR, Philip CL, Nguyên HX, & Sellers RM (2008). Patterns of racial socialization and psychological adjustment: Can parental communications about race reduce the impact of racial discrimination? Journal of Research on Adolescence, 18, 477–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2008.00568.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Smalls CP, Ford KR, Nguyên HX, Sellers RM (2009). Racial socialization and racial identity: African American parents’ messages about race as precursors to identity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 189–203. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9359-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, & Bauer DJ (2006). Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31, 437–448. doi: 10.3102/10769986031004437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, & Hayes AF (2007). Assessing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42, 185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prelow HM, Danoff-Burg S, Swenson RR, & Pulgiano D (2004). The impact of ecological risk and perceived discrimination on the psychological adjustment of African American and European American Youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 32, 375–389. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Lewinshon PM & Seeley JR (1991). Screening for adolescent depression: A comparison of depression scales. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30, 58–66. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199101000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott LD & House LE (2005). Relationship of distress and perceived control to coping with perceived racial discrimination among Black youth. Journal of Black Psychology, 31, 254–272. doi: 10.1177/0095798405278494 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Caldwell CH, Sellers RM & Jackson JS (2008). The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1288–1297. doi: 10.1037/a0012747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Yip T, & Sellers RM (2009). A longitudinal examination of racial identity and racial discrimination among African American adolescents. Child Development, 80, 406–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01268.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Neblett E, Upton RD, Powell Hammond W. & Sellers RM (2011). The moderating capacity of racial identity between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being over time among African American youth. Child Development, 82, 1850–1867. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01651.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Smith M, Shelton JN, Rowley SJ, & Chavous TM (1998). Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2, 18–39. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Linder NC, Martin PM, & Lewis RL (2006). Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16, 187–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00128.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR & Collins C (2001). Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports, 116, 404–415. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, & Jackson JS (2003). Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 200–208. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, & Mohammed SA (2009). Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32, 20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]