Abstract

In a previous study, we reported that a brief exposure to swim stress transforms an electrically induced, protein synthesis-independent early long-term potentiation (early LTP) into a protein synthesis-dependent late LTP [“reinforcement of LTP” in the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG)] (Korz and Frey, 2003). This transformation depends on activation of mineralocorticoid receptors (MRs) by corticosterone, and on intact basolateral amygdala (BLA) function. Here, we demonstrate that a brief swim experience results in lasting changes in levels of hippocampal cellular signaling molecules that are known to be involved in the induction of late LTP. Within the DG, MRs were rapidly upregulated, whereas glucocorticoid receptor (GR) levels were elevated with a 3 h delay. Levels of phosphorylated mitogen-activated protein kinase 2 (pMAPK2) and p38 MAPK, as well as phosphorylated calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (pCaMKII) were enhanced shortly after swim stress and remained elevated until 24 h, whereas levels of phosphorylated cAMP response element-binding protein (pCREB) remained unchanged. MR and GR were upregulated with a longer delay within the CA1 region, whereas levels of pMAPK2 and p38MAPK were rapidly increased, but the former returned to basal levels after 3 h. Levels of pCREB and pCaMKII were maintained in an enhanced state after swim stress. DG-LTP reinforcement requires a serotonergic but not dopaminergic heterosynaptic receptor activation that probably mediates the BLA-dependent modulation of LTP under stress. Thus, molecular alterations induced by specific stress resemble late LTP-related molecular changes. These changes, in interaction with stress-specific heterosynaptic processes, may support the transformation of early LTP into late LTP. The results contribute to the understanding of the rapid consolidation of cellular and possibly systemic memories triggered by stress.

Keywords: CaMKII, MAP kinase, early LTP, late LTP, memory, stress, glucocorticoid receptors, mineralocorticoid receptors

Introduction

Long-term potentiation (LTP) is considered to be a cellular model for learning and memory formation. Frey and Morris (1997) suggested a novel associative mechanism required for the consolidation of LTP as well as memory formation at the cellular level named “synaptic tagging.” A weak electrically activated synaptic input inducing early LTP sets a “synaptic tag” being active for a distinct time. Plasticity-related proteins, the synthesis of which was induced by temporally related modulatory heterosynaptic inputs (e.g., triggered by a strong tetanic stimulation of a second independent synaptic input) can be captured and processed by this tag leading to a transformation into a protein synthesis-dependent late LTP (LTP reinforcement) at the tagged, weakly stimulated synapse population.

The molecular basis of LTP in slice preparations in vitro obtained from the cornu ammonis 1 region (CA1) of the rat hippocampus is intensively studied (for review, see Sweatt, 2001; Lisman et al., 2002, Kelleher et al., 2004b). However, the molecular mechanisms in vivo are less well understood, particularly for the dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus. A regulation of a variety of genes encoding signal transduction molecules (Hevroni et al., 1998) and of immediate early genes involved in transcriptional processes has been identified (Abraham et al., 1991; French et al., 2001; Rodriguez et al., 2005) (for review, see Abraham and Williams, 2003). Upregulation of the phosphodiesterase PDE4B3 (Ahmed et al., 2004), α-calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein-kinase II (αCaMKII) (Davis et al., 2000), and proteins involved in spine (Yamazaki et al., 2001) and synapse morphology (Kato et al., 1997) after electrical induction of late LTP in the DG in vivo has also been reported.

Little is known about the molecular mechanisms involved in the modulation of DG-LTP by behavioral experience and stress (Abraham and Williams, 2003), although it has been pointed out that in the DG, acute stress and LTP converge on similar neuronal mechanisms (Shors and Dryver, 1994) resulting in a rapid consolidation of associative memories (Shors, 2001).

Early LTP in vivo lasting ∼4–5 h can be transformed into late-LTP by unexpected reward (Seidenbecher et al., 1997; Bergado et al., 2003) and novelty detection (Straube et al., 2003) during distinct time windows around tetanus. These kinds of LTP reinforcement under low or moderate stress conditions were dependent on β-adrenergic activation and protein-synthesis. Reinforcement by novelty experience under high acute swim stress, however, was dependent on activation of mineralocorticoid receptors (MRs) by corticosterone on protein synthesis and on an intact basolateral amygdala (BLA), but not on β-adrenergic activation (Korz and Frey, 2003, 2005). Increased dopamine (Inoue et al., 1994; Inglis and Moghaddam, 1999; Macedo et al., 2005; Yokoyama et al., 2005) as well as serotonin (5-HT) levels (De La Garza and Mahoney, 2004; Macedo et al., 2005; Yokoyama et al., 2005) within the BLA and other brain structures during stress have also been reported.

The present study was aimed at the identification of possible molecular and heterosynaptic mechanisms underlying the reinforcement by acute swim stress focusing on molecules known to be involved in the induction of late-LTP, and on stress sensitive transmitters.

Materials and Methods

Surgery and electrophysiological recording.

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with local and national regulations with respect to animal care. Male Wistar rats (8 weeks old) were anesthetized with Nembutal (40 mg/kg, i.p.). A monopolar recording electrode (insulated stainless steel, 125 μm in diameter) was implanted stereotaxically into the hilus of the DG and a bipolar stimulation electrode into the medial perforant path of the right hemisphere. During preparation, the population-spike amplitude (PSA) was optimized by delivering test pulses. The animals were allowed at least 1 week to recover from surgery.

During recording, electrodes were connected to a swivel by a flexible cable while rats were allowed to move freely in a recording box (40 × 40 × 40 cm). The animals had ad libitum access to food and water. The responses were amplified and stored on a personal computer. Biphasic constant-current pulses (0.1 ms per one-half wave) were applied to the perforant path to evoke DG field potentials of ∼40% of the maximum PSA. Because the spike is required to induce LTP, the preparation was optimized to obtain a population spike, which, however, influences the dipole of the field EPSP (fEPSP) in the hilus. Therefore, the recording of the PSA was preferred against the EPSP. A stable baseline was registered for 1 h and early LTP was induced by weak tetanic bursts (three bursts of 15 pulses of 200 Hz with 0.1 ms duration of each stimulus and 10 s interburst interval) at the same stimulus intensity as used for the test pulses. The strong tetanus consisted of 10 bursts. Initially after 2 min and then every 15 min after tetanization, five test stimuli (10 s interpulse intervals) were applied and the mean values of field potentials were stored for the subsequent 8 h. For analysis and presentation, 1 h values were averaged over every four 15 min values. The next day, four 15 min values were averaged for a 24 h value. The 2 min value controlled for the achievement of a sufficient initial potentiation. Tetanization and experimental manipulations in most experiments took place between 10:00 and 11:00 A.M. to consider the diurnal rhythm of corticosterone titers. In one experiment, the behavioral manipulation took place 4 h after tetanus (i.e., 2:00–3:00 P.M.), around the 3 h time point, with similar corticosterone levels as the controls so that an impact of corticosterone on the results of this experiment is unlikely.

Swim-stress paradigm.

The water tank was a white, circular, plastic tank (1.82 m diameter, 58 cm high). The water level was 38 cm and the temperature at 25 ± 2°C but constant during a session. Water was made opaque using white latex fluid (Sakret, Gießen, Germany). Naive rats were set into the tank 15 min, 1 h, or 4 h after tetanus or 1 h before tetanus and remained there for 2 min. They were then towel-dried and transferred back to the recording chamber. Towel-treatment on rats has a minor effect on the corticosterone response that does not exceed that of handling (Korz and Frey, 2003). Before swimming, the electrodes were protected from water immersion with Vaseline. Control animals remained in the recording boxes.

Protein biochemistry.

The animals used for the protein biochemistry experiments were all swim naive. Fifteen minutes after swim stress the animals were killed and the right hippocampus isolated in ice-cold carbogenated artificial CSF medium. The dentate was rapidly separated from the CA1 tissue by gently teasing the tissue apart and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The tissue was prepared by homogenization (Biovortexer; Biospec Products, Bartesville, OK) in ice-cold buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) containing proteinase inhibitors (Roche Diagnostic, Mannheim, Germany) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 1 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Sample protein concentrations were established using the Bradford method (Bradford, 1976). From these values, 20 μg of total protein lysates were mixed with a commercial protein loading mix (Roti-load; Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) and then subjected to SDS-PAGE (4% stacking gel, 5–20% resolving gradient gel). Electrophoresis was run with constant current (22 mA) for 3 h with constant cooling. The fractionated proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Amersham Biosciences, Bucks, UK) for immunoblotting. Membranes were blocked for 60–120 min with nonfat milk [5% (w/v)] dissolved in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.01% (v/v) Tween 20 (TBST) (Fluka, Neu-Ulm, Germany; Sigma), pH 7.4, then incubated overnight with gentle shaking at 4°C with primary antibody. For all analyses, single antibodies were tested and then membranes were completely stripped [two 30 min washes in strip buffer containing 0.5 m glycine, 0.1% (v/v) SDS, and 1% (v/v) Tween 20, pH 2.2, and then three 10 min washes with TBST] and retested to confirm no residual activity. The antibodies for cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) assays were anti-phospho-ser-133-CREB mouse monoclonal IgG antibody and anti CREB rabbit polyclonal IgG. The antibodies for CaMKII assays were anti-phospho-thr 286-CaMKII mouse monoclonal IgG antibody and anti-CaMKII mouse monoclonal IgG. The antibodies for mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) assays were anti-phospho MAP kinase (Erk) 1/2 mouse monoclonal IgG and anti-MAP kinase 1/2 rabbit IgG (all from Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY; Biomol Feinchemikalien, Hamburg, Germany). All antibodies were diluted 1:2000 in TBST. The antibodies for the p38 MAPK assays were p38 phospho-(thr-180/tyr-182) MAP kinases, and rabbit monoclonal IgG antibody and total p38 MAPK rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), both diluted 1:2000 in TBST. For detection we used anti-mouse, anti-sheep, and anti rabbit IgG-horse radish peroxidases, diluted 1:10,000 in TBST (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA; Dianova, Hamburg, Germany), and ECL reagents for immunodetection from Amersham Biosciences. For mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid, mouse monoclonal IgGs (1:400 in TBST) were used (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid values were normalized to neurofilament 68 monoclonal antibody mouse monoclonal IgG antibody (Sigma) diluted 1:2000 in TBST. The intensities of protein bands in immunoblots were analyzed by densitometry with a Macintosh computer using the public domain National Institutes of Health (NIH) Image program developed at the NIH (Bethesda, MD). It should be noted that for data analyses, gamma threshold was set at 20% and samples were analyzed from this ratio for densitometry. The phosphorylated isoforms were normalized to the total isoform as a ratio, which was presented as a percentage value in histograms.

Hormone analysis.

A second set of animals experienced the same treatment as those with electrode implantations. Swim naive rats were decapitated 15 min after a 2 min swim and trunk blood was collected. Animals that remained in the recording box and were decapitated at the same time point as the swimming groups served as a control group. For the time course of hormone measurements, swim naive animals were decapitated 1, 3, 8, and 24 h after a 2 min swim. Blood was sampled in an Eppendorf tube and allowed to coagulate at room temperature. Then the blood was centrifuged and the serum was stored at −20°C. Samples were analyzed by radioimmunoassay.

Pharmacology.

SCH23390 (Schering 23390; Sigma), a dopamine receptor antagonist (1 μg) that has been shown not to affect PSA baseline levels (Frey et al., 2001), was dissolved in saline, and dihydroergocristine (Tocris, Bristol, UK), an unspecific 5-HT receptor antagonist (12.5 μg), was dissolved in distilled water. The drugs were applied intracerebroventricularly (5 μl over a 5 min period) immediately after tetanus. Saline-treated animals served as controls.

Statistics.

The general linear model for repeated measures (GLM) was used for group comparisons of overall differences in LTP between groups with subsequent least-significant difference multiple-comparisons tests across all time points. GLM equals ANOVA but is suitable for comparing results for different sample sizes. Differences in hormone and protein levels were evaluated with Mann–Whitney U tests by comparing the values of the experimental groups of each time point with the controls. All tests were two-tailed and the level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

The effects of swim duration

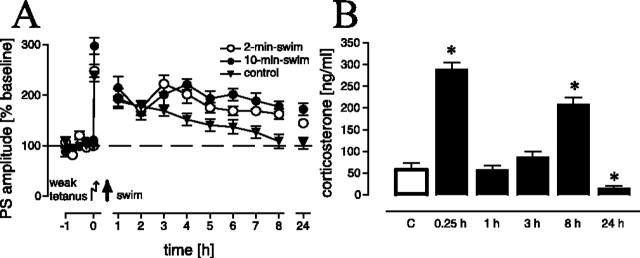

The first set of experiments addressed the question of whether different lengths of swim (i.e., the modulation of the stress experience) have different effects on LTP reinforcement, for instance, in the way that increased swim duration results in increased potentiation. We found a significant effect in the time course of LTP between the control, 2-min-swim, and 10-min-swim groups (F(2,22) = 6.09; p < 0.01). LTP was reinforced in animals from both experimental groups as compared with controls (p = 0.021 and p = 0.003, respectively) (Fig. 1A). However, between the two experimental groups, no difference in LTP could be noted (p > 0.1). Thus, the prolongation of the stress procedure did not result in additional potentiation. Therefore, in all subsequent experiments, the 2-min-swim procedure was used.

Figure 1.

A, LTP after a 2 min (n = 9) and a 10 min (n = 7) swim, 15 min after application of a weak tetanus. Swimming animals showed significantly prolonged LTP as compared with nonswimming controls (n = 10) (A). B, Time course of serum corticosterone levels after a 2 min swim. Levels are significantly increased 15 min and 8 h and significantly reduced 24 h after swimming (n = 6 for controls; n = 8 for each experimental group). Given are the means and SEM. Asterisks indicate significant differences for the respective time points as compared with controls. The data set in A (15 min group) was partially adopted from Korz and Frey (2003) and complemented additional experiments.

The effects of swim stress on corticosterone release

The measurement of the time course of corticosterone release after the brief swim experience should allow for the identification of possible vulnerable time windows in which interactions of corticosterone with other signaling systems are most probable. Time point-specific comparisons revealed only a transient increase in corticosterone after swim stress (Fig. 1B), as indicated by the elevated levels in the 15 min group as compared with controls (p < 0.01). Within 1 h, corticosterone titers return to control levels (i.e., the 1 h group showed no difference in comparison to control animals; p > 0.1) and remain at control levels for 3 h (p > 0.1). At the 8 h time point, we again observed a significant peak (p < 0.01), whereas 24 h after swim stress, the corticosterone levels dropped below the control levels (p < 0.05). A similar large increase in corticosterone (and even more) shortly before the end of the light cycle (at the 8 h time point in our study) has also been reported previously (Ishikawa et al., 1995; Zandieh Doulabi et al., 2004) and is therefore not untypical for the diurnal variation in male Wistar rats. Furthermore, daily rhythms of corticosterone in rats are quite stable in response to behavioral manipulations like food restriction (Leal and Moreira, 1997) or acute stress (Retana-Marquez et al., 2003), so the 8 h peak may be related to the daily rhythm of corticosterone. We are aware that from these data we cannot judge the effects of the diurnal rhythm, but this was not the aim of the study, which only addressed the time course of corticosterone in experimental animals to assess a time window for corticosterone-related cellular-signaling processes.

Functional time windows of LTP reinforcement

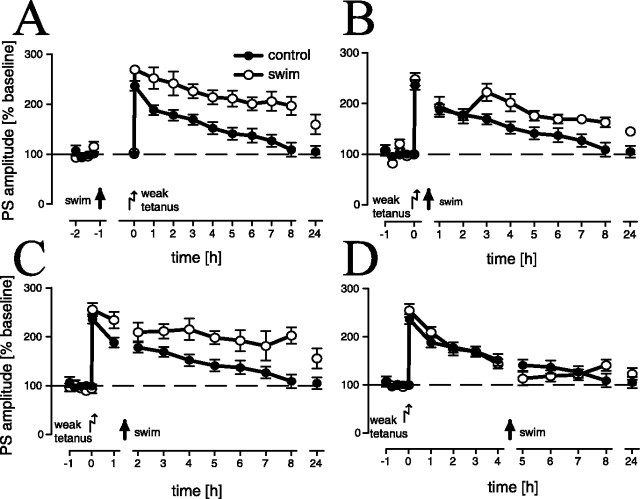

These experiments were performed to evaluate the time window around the application of the weak tetanus in which LTP is reinforced by swim stress. We noted a significant overall difference between experimental animals that swam 1 h before and 15 min, 1 h, or 4 h after application of the weak tetanus and controls (F(4,33) = 6.93; p < 0.001). LTP reinforcement could be observed in animals that swam 1 h (Fig. 2A) before (p < 0.001) and 15 min (Fig. 2B) (p = 0.023) or 1 h (Fig. 2C) after (p = 0.002) the weak tetanus, as compared with the (sampled) control group, whereas animals that swam 4 h (Fig. 2D) after the tetanus showed no difference (p > 0.1) in comparison with controls. In addition, in the 15 min (p = 0.03) and 1 h (p = 0.02) after-tetanus groups, as well as in the 1 h (p = 0.001) before-tetanus group, LTP was reinforced as compared with the 4 h after-tetanus experimental group, whereas between the three first experimental groups, no difference could be noted. Thus, the functional time window that corresponds to the time window of elevated corticosterone levels is 1 h around tetanus. We noted a slightly increased potentiation in the 1 h before-tetanus swim group (Fig. 2A) that may be related to the cellular changes induced by the swim stress; however, the initial potentiation is not statistically significantly different from controls.

Figure 2.

LTP is significantly reinforced after a 2 min swim, 1 h before (A) (n = 5) and 15 min (B) (n = 9) or 1 h after (C) (n = 6), but not 4 h after (D) (n = 9) a weak tetanus (sample controls, n = 10). Given are the means and SEM.

Molecular changes induced by swim stress

Because of the high affinity of the MR for corticosterone, the receptors are usually saturated even at basal levels of the hormone. To address the question how the activation of the MR can then function as a stress-related cellular signal, we tested a possible regulation on the receptor level after swim stress. In addition, we tested key molecules involved in the induction of late-LTP such as CaMKII and MAPK2 or in mediating stress effects such as CREB and p38 MAP kinase. Two hippocampal subregions were analyzed by Western blotting.

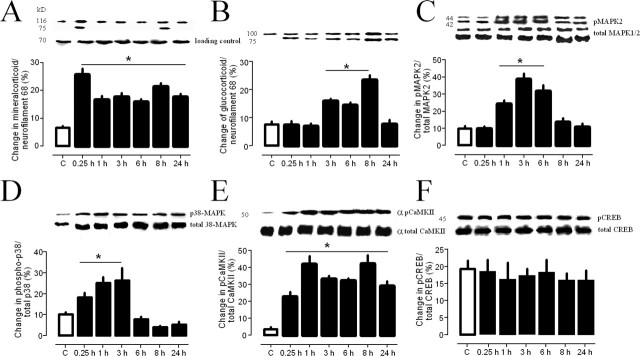

Dentate gyrus

As indicated in Figure 3A, we found a rapid increase of MR in the dentate gyrus 15 min after swim stress (p = 0.021). The levels remained elevated over 24 h as compared with controls (p < 0.05 each). The glucocorticoid receptor (GR) levels were also elevated, but with a delay of at least 1 h (Fig. 3B). The levels of the activated forms of both MAP kinases (p42/p44) were enhanced (Fig. 3C,D) but the level of the stress-related p38 MAPK was immediately increased up to the 3 h time point (p < 0.05), whereas p42 MAPK increased with a 1 h delay until the 6 h time point. The levels of phosphorylated CaMKII were increased immediately after swim stress and remained elevated over 24 h (Fig. 3E). Surprisingly we found no enhancement of phosphorylated CREB (pCREB) after swim stress (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3.

Regulation of protein levels and levels of phosphorylated proteins within the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus at different time points (n = 4, each) after a 2 min swim for mineralocorticoid receptors (A), glucocorticoids receptors (B), pMAPKs (C), p38MAPK (D), αpCaMKII (E), and pCREB (F). Given are the means and SEM. Asterisks indicate significant differences for the respective time points as compared with controls.

CA1 area

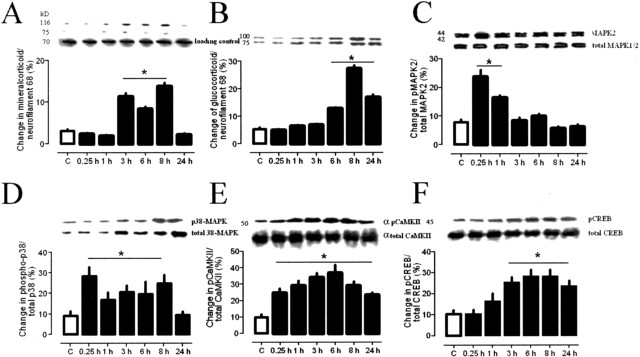

In contrast with the DG, we found a delayed increase of MR after 1 h and a similar delay of GR with a significant increase after 3 h, as compared with the DG (Fig. 4A,B). The levels of phosphorylated 42/44 and 38 MAP kinases were potentiated immediately after swim stress and returned to basal levels within 24 h (Fig. 4C,D). Similar to the dentate gyrus, pCaMKII levels were immediately increased and remained enhanced over 24 h (Fig. 4E). Again, in contrast with the DG, we found increased levels of pCREB after 1 h in the CA1 (Fig. 4F).

Figure 4.

A–F, Regulation of protein levels and levels of phosphorylated proteins within the CA1-region of the hippocampus at different time points (n = 4, each) after a 2 min swim for mineralocorticoid receptors (A), glucocorticoids receptors (B), pMAPKs (C), p38MAPK (D), αpCaMKII (E), and pCREB (F). Given are the means and SEM. Asterisks indicate significant differences for the respective time points as compared with controls.

Neurotransmitters involved in swim stress reinforced LTP

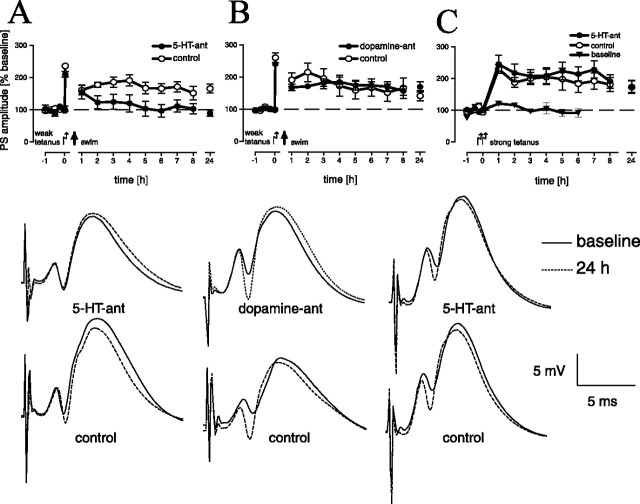

LTP reinforcement was mediated by serotonergic (Fig. 5A) but not dopaminergic (Fig. 5B) activation. A significant difference in LTP between dopamine and serotonin receptor antagonist-treated animals and the two control groups could be noted (F(3,30) = 3.01; p < 0.05). Post hoc tests revealed a significant difference in LTP between animals treated with a serotonin receptor antagonist and the (time matched) controls (p = 0.021 and 0.019, respectively), and with the dopamine receptor antagonist treated group (p = 0.018). No significant difference was detectable between the other groups. Furthermore, the serotonergic effect is stress specific, as indicated by an electrically induced late LTP that was independent of serotonergic activation (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

LTP reinforcement by a 2 min swim is inhibited by blockade (dihydroergocristine) of serotonin receptors (A) (treated group, n = 8; controls, n = 9), but not by dopaminergic (Schering 23390) blockade (B) (treated group, n = 9; controls, n = 8) as compared with time-matched controls. Given are the means and SEM. The insets show representative analog traces of population spike amplitudes for indicated time points for individual animals of the different groups of experiments A–C (from left to right).

Discussion

Functional time windows

There is a sensitive time window of ∼1 h (compare Fig. 2) around tetanus in which swim stress reinforces DG-LTP and in which corticosterone levels were upregulated, respectively. We conclude from these results that hormonal and molecular changes that are directly involved or induce required processes within this time window are of special importance for the conversion of early into late LTP. Subsequent changes may be related to other neuronal processes or daily rhythms.

Molecules involved in LTP reinforcement

Mineralocorticoid receptors

The fast upregulation of MR receptors, which have been identified to being involved in swim stress-reinforced LTP (Korz and Frey, 2003), may be based on transcriptional and nontranscriptional mechanisms. Castren et al. (1995) found a glucocorticoid-induced increase of MR mRNA and protein in cultured hippocampal neurones by direct activation of the MR promoter by corticosterone indicating, at least in part, a transcriptional regulation of MR. At this, the combination of different weak enhancer glucocorticoid-responsive elements led to an MR gene expression by both types of corticosteroid receptors. In addition to the transcriptional regulation of glucocorticoid-responsive genes by homodimers (Arriza et al., 1988; de Kloet, 1991; Karst et al., 2000), a regulatory role of GR-MR-heterodimers has been described (Trapp et al., 1994). The formation of heterodimers in vitro takes place within the nucleus and depends on the concentration of corticosterone, suggesting a particular role in transcriptional activity under stress conditions (cf. Castren et al., 1995). A MAPK-dependent nontranscriptional pathway in vivo has been described by Müller Igaz et al. (2004). They found an upregulation of CaMKII- and MAPK2-mRNAs 3 h after a one-trial aversive learning, whereas the protein levels were elevated only 24 h after training, which was explained by an early transient translational suppression of the transcripts. In our study, the translation of pre-existing MR mRNA may also initially be suppressed and then, triggered by acute corticosterone signaling, induced by stress and novelty detection. The importance of translational control by MAPK signaling in the formation of hippocampus-dependent long-term memory and LTP has been pointed out by Kelleher et al. (2004a).

Mitogen-activated protein kinases

PKA, PKC, and MAPK pathways are also involved in corticosterone-induced gene transcription (Budziszewska et al., 2000), stress-related synaptic plasticity (Yang et al., 2004), and fear conditioning (Sweatt, 2001; Sananbenesi et al., 2003; Revest et al., 2005). Therefore, LTP reinforcement cannot be correlated alone to transcription caused by activated MR complexes, but possibly caused by processes downstream from the interaction sites within the MAPK pathways. Both the p38 and the p42/44 MAP kinases were enhanced within 1 h after stress within the DG, making these proteins suitable as putative candidates for these interactions. Navakkode et al. (2005) found p42/44 MAPKs to have a pivotal role in the maintenance of an associative long-term depression in the CA1 region in hippocampal slice experiments in vitro. These results may favor the role of the p42/44 over the p38 isoform in our study, pointing to different region-specific functions or different effects in dependence of the preparation (in vitro/in vivo) of the MAPK isoforms.

Calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase

CaMKII is a crucial molecule, being involved in the induction of CA1-LTP and in memory formation (Malinow et al., 1988; Lisman et al., 2002; Ahmed and Frey 2005). However, because LTP reinforcement by swim stress depends on MR and 5-HT receptor activation, an interaction of CaMKII and one or both of these receptors has to be assumed. To our knowledge, for MR receptors, such an interaction has not yet been described. At least some evidence for an interplay between serotonin receptors and CaMKII in hippocampus-dependent learning (Moyano et al., 2004; Schiapparelli et al., 2005) and serotonin-dependent changes in CaMKII autophosphorylation in the hippocampus has been discussed (Popoli et al., 1995). Thus, CaMKII in the DG may contribute to LTP reinforcement by yet unknown mechanisms during stress.

cAMP response element-binding protein

The surprising result of the lack of enhanced pCREB within the DG may be an outcome of glucocorticoid effects. Legradi et al. (1997) report that glucocorticoids suppress CREB phosphorylation, a feedback mechanism for the inhibition of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) biosynthesis in the hypothalamus. In our study, a similar, long-lasting effect seems to take place in the DG, but not the CA1. The results for the DG contrast with those of Bilang-Bleuel et al. (2002) who noted an enhancement of pCREB in the DG after swim stress. However, in this study, either stress or exposure to a cold environment were ineffective on enhancing CREB phosphorylation, pointing to a stressor-specific pCREB response. Furthermore, Shen et al. (2004) found an increase of activated p38 MAPK but not p42/44 MAPK within the hippocampus under similar swim-stress conditions. Thus, these seemingly contradictory results may be explained by the different stress procedures and/or rat strains used. These authors forced the rats to swim for 15 min in a small (20 or 24 cm in diameter) glass cylinder, which may cause an escalated stress response, whereas in our study, the animals were allowed to explore a water arena for 2 or 10 min, inducing only a transient increase in corticosterone. The first procedure is very likely distinguished through uncontrollability, whereas the second provides the possibility to escape from the situation. Uncontrollability of a stressful situation impairs LTP, in contrast to controllable stress (Shors et al., 1989).

Neurotransmitter systems involved in LTP reinforcement

The balance of occupied MR and GR, rather than the individual dynamics of the different receptors, determine the physiological functions regulated by these receptors (de Kloet et al., 2005). In addition, monoamine neurotransmitters can modulate densities of GR and MR within the hippocampus. Whereas most studies report increased levels of hippocampal serotonin (Connor et al., 1999; Linthorst et al., 2002; Umriukhin et al., 2002) after swim stress, which may be also functional during cognitive tasks in the water maze (Richter-Levin et al., 1994), others found no change (Kirby et al., 1997). These opposing effects may be related to the specificity of central serotonergic responses to stress and the interplay of serotonergic transmission, corticoids, and stress to different experimental designs (Chaouloff, 2000). Additionally, an increase of 5-HT levels (De La Garza and Mahoney, 2004; Macedo et al., 2005; Yokoyama et al., 2005) and 5-HT turnover in the amygdala (Kelliher et al., 2000), as well as changes in the activity of the cortical synaptosomal serotonin transporter (Racca et al., 2005), have been observed after swim stress or conditioned fear. 5-HT has been reported to increase both the GR and MR mRNA in hippocampal cells, which could be blocked by a 5HT receptor antagonist in the case of MR but not GR (Budziszewska et al., 1995; Lai et al., 2003). With moderate amounts of 5-HT, the excitatory transmission in the DG is promoted by predominant MR occupation and reduced by additional GR activation (Karten et al., 2001). Furthermore, peptidergic inputs related to stress, such as corticotropin-releasing hormone, particularly increases MR (Gesing et al., 2001; Hugin-Flores et al., 2004).

Inoue et al. (1994) found, with increasing stress intensity, an increasing number of brain structures with potentiated 5-HT and dopamine levels. A dopaminergic effect by upregulation of dopamine levels in the amygdala (Inglis and Moghaddam, 1999; Macedo et al., 2005; Yokoyama et al., 2005) can be ruled out in our case by the fact that dopaminergic blockade has no effect on LTP reinforcement. It has been shown that dopaminergic (Berger et al., 1976; Goldstein et al., 1996; Rosenkranz and Grace, 1999) and noradrenergic (Roozendaal et al., 2004) activation of the amygdala mediates the communication with the prefrontal cortex during stress so that a prefrontal contribution to LTP reinforcement is unlikely in our study. However, brain structure-specific activations remain to be identified. Recently, we have shown that an intact basolateral amygdala is required for the LTP reinforcement by swim stress (Korz and Frey, 2005), but because of the intracerebroventricular application of antagonists in our studies, it is still unclear whether the MR or the serotonergic effect is required in both structures, the hippocampus and the amygdala, or in only one of these structures.

However, the present data show that a brief stressful experience induces lasting changes in cellular signaling in the DG that partly resemble electrically induced late LTP. Mechanisms triggered by these signals in interaction with stress-specific changes may support the transformation from early into late LTP. The results contribute to the understanding of the rapid consolidation of cellular and possibly systemic memories triggered by stress.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Land Saxony-Anhalt (LSA3475A/1102M). We thank Dr. V. Stefanski (University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany) for analyzing the blood samples and G. Behnisch and J. Maiwald for excellent technical assistance.

References

- Abraham WC, Williams JM (2003). Properties and mechanisms of LTP maintenance. Neuroscientist 9:463–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham WC, Dragunow M, Tate WP (1991). The role of immediate early genes in the stabilization of long-term potentiation. Mol Neurobiol 5:297–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed T, Frey JU (2005). Plasticity-specific phosphorylation of CaMKII, Map-kinases and CREB during late-LTP in rat hippocampal slices in vitro. Neuropharmacology 49:477–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed T, Frey S, Frey JU (2004). Regulation of the phosphodiesterase PDE4B3-isotype during long-term potentiation in the area dentata in vivo. Neuroscience 124:857–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arriza JL, Simerly RB, Swanson LW, Evans RM (1988). The neuronal mineralocorticoid receptor as a mediator of glucocorticoid response. Neuron 1:887–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergado JA, Almaguer-Melian W, Kostenko S, Frey S, Frey JU (2003). Behavioral reinforcement of long-term potentiation in rat dentate gyrus in vivo is protein synthesis-dependent. Neurosci Lett 351:56–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger B, Thierry AM, Tassin JP, Moyne MA (1976). Dopaminergic innervation of the rat prefrontal cortex: a fluorescence histochemical study. Brain Res 106:133–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilang-Bleuel A, Rech J, De Carli S, Holsboer F, Reul JMHM (2002). Forced swimming evokes a biphasic response in CREB phosphorylation in extrahypothalamic limbic and neocortical brain structures in the rat. Eur J Neurosci 15:1048–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budziszewska B, Siwanowicz J, Przegalinski E (1995). Role of the serotonergic system in the regulation of glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoid receptors in the rat hippocampus. Pol J Pharmacol 47:299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budziszewska B, Jaworska-Feil L, Kajita M, Lason W (2000). Antidepressant drugs inhibit glucocorticoid receptor-mediated gene transcription: a possible mechanism. Br J Pharmacol 130:1385–1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castren M, Trapp T, Berninger B, Castren E, Holsboer F (1995). Transcriptional induction of rat mineralocorticoid receptor gene in neurones by corticosteroids. J Mol Endocrinol 14:285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaouloff F (2000). Serotonin, stress and corticoids. J Psychopharmacol 14:139–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor TJ, Kelliher P, Harkin A, Kelly JP, Leonard BE (1999). Reboxetine attenuates forced swim test-induced behavioural and neurochemical alterations in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol 379:125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis S, Salin H, Helme-Guizon A, Dumas S, Stephan A, Corbex M, Mallet J, Laroche S (2000). Dysfunctional regulation of αCaMKII and syntaxin 1B transcription after induction of LTP in the aged rat. Eur J Neurosci 12:3276–3282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Garza R II, Mahoney JJ III (2004). A distinct neurochemical profile in WKY rats at baseline and in response to acute stress: implications for animal models of anxiety and depression. Brain Res 1021:209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet ER (1991). Brain corticosteroid receptor balance and homeostatic control. Front Neuroendocrinol 12:95–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet ER, Joëls M, Holsboer F (2005). Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 6:463–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French PJ, O'Connor V, Jones MW, Davis S, Errington ML, Voss K, Truchet B, Wotjak C, Stean T, Doyere V, Maroun M, Laroche S, Bliss TV (2001). Subfield-specific immediate early gene expression associated with hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Eur J Neurosci 13:968–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey S, Bergado-Rosado J, Seidenbecher T, Pape HC, Frey JU (2001). Reinforcement of early long-term potentiation (early LTP) in dentate gyrus by stimulation of the basolateral amygdala: heterosynaptic induction mechanisms of late-LTP. J Neurosci 21:3697–3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey U, Morris RG (1997). Synaptic tagging and long-term potentiation. Nature 385:533–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesing A, Bilang-Bleuel A, Droste SK, Linthorst AC, Holsboer F, Reul JM (2001). Psychological stress increases hippocampal mineralocorticoid receptor levels: involvement of corticotropin-releasing hormone. J Neurosci 21:4822–4829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein LE, Rasmusson AM, Bunney BS, Roth RH (1996). Role of the amygdala in the coordination of behavioral, neuroendocrine, and prefrontal cortical monoamine responses to psychological stress in the rat. J Neurosci 16:4787–4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevroni D, Rattner A, Bundman M, Lederfein D, Gabarah A, Mangelus M, Silverman MA, Kedar H, Naor C, Kornuc M, Hanoch T, Seger R, Theill LE, Nedivi E, Richter-Levin G, Citri Y (1998). Hippocampal plasticity involves extensive gene induction and multiple cellular mechanisms. J Mol Neurosci 10:75–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugin-Flores ME, Steiner T, Aubert ML, Schulz P (2004). Mineralo- and glucocorticoid receptor mRNAs are differently regulated by corticosterone in the rat hippocampus and anterior pituitary. Neuroendocrinology 79:174–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglis FM, Moghaddam B (1999). Dopaminergic innervation of the amygdala is highly responsive to stress. J Neurochem 72:1088–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Tsuchiya K, Koyama T (1994). Regional changes in dopamine and serotonin activation with various intensity of physical and psychological stress in the rat brain. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 49:911–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M, Ohdo S, Watanabe H, Hara C, Ogawa N (1995). Alteration in circadian rhythm of plasma corticosterone in rats following sociopsychological stress induced by communication box. Physiol Behav 57:41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karst H, Karten YJ, Reichardt HM, de Kloet ER, Schutz G, Joels M (2000). Corticosteroid actions in hippocampus require DNA binding of glucocorticoids receptor homodimers. Nat Neurosci 3:977–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karten YJ, Stienstra CM, Joels M (2001). Corticosteroid effects on serotonin responses in granule cells of the rat dentate gyrus. J Neuroendocrinol 13:233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato A, Ozawa F, Saitoh Y, Hirai K, Inokuchi K (1997). vesl, a gene encoding VASP/Ena family related protein, is upregulated during seizure, long-term potentiation and synaptogenesis. FEBS Lett 412:183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher RJ III, Govindarajan A, Jung HY, Kang H, Tonegawa S (2004a). Translational control by MAPK signaling in long-term synaptic plasticity and memory. Cell 116:467–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher RJ III, Govindarajan A, Tonegawa S (2004b). Translational regulatory mechanisms in persistent forms of synaptic plasticity. Neuron 44:59–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelliher P, Connor TJ, Harkin A, Sanchez C, Kelly JP, Leonard BE (2000). Varying responses to the rat forced-swim test under diurnal and nocturnal conditions. Physiol Behav 69:531–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby LG, Chou-Green JM, Davis K, Lucki I (1997). The effects of different stressors on extracellular 5-hydroxytryptamine and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid. Brain Res 760:218–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korz V, Frey JU (2003). Stress-related modulation of hippocampal long-term potentiation in rats: involvement of adrenal steroid receptors. J Neurosci 23:7281–7287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korz V, Frey JU (2005). Bidirectional modulation of hippocampal long-term potentiation under stress and no-stress conditions in basolateral-amygdala lesioned and intact rats. J Neurosci 25:7393–7400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M, McCormick JA, Chapman KE, Kelly PAT, Seckl JR, Yau JLW (2003). Differential regulation of corticosteroid receptors by monoamine neurotransmitters and antidepressant drugs in primary hippocampal culture. Neuroscience 118:975–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal AM, Moreira AC (1997). Daily variation of plasma testosterone, androstenedione, and corticosterone in rats under food restriction. Horm Behav 31:97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legradi G, Holzer D, Kapcala LP, Lechan RM (1997). Glucocorticoids inhibit stress-induced phosphorylation of CREB in corticotrophin-releasing hormone neurons of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Neuroendocrinology 66:86–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linthorst AC, Penalva RG, Flachskamm C, Holsboer F, Reul JM (2002). Forced swim stress activates rat hippocampal serotonergic neurotransmission involving a corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor-dependent mechanism. Eur J Neurosci 16:2441–2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman J, Schulman H, Cline H (2002). The molecular basis of CaMKII function in synaptic and behavioural memory. Nat Rev Neurosci 3:175–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macedo CE, Martinez RC, de Souza Silva MA, Brandao ML (2005). Increases in extracellular levels of 5-HT and dopamine in the basolateral, but not in the central, nucleus of amygdala induced by aversive stimulation of the inferior colliculus. Eur J Neurosci 21:1131–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinow R, Madison DV, Tsien RW (1988). Persistent protein kinase activity underlying long-term potentiation. Nature 335:820–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyano S, Del Rio J, Frechilla D (2004). Role of hippocampal CaMKII in serotonin 5-HT (1A) receptor-mediated learning deficit in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 29:2216–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller Igaz L, Bekinschtein P, Izquierdo I, Medina JH (2004). One-trial aversive learning induces late changes in hippocampal CaMKIIα, Homer 1a, Syntaxin 1a and ERK2 protein levels. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 132:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navakkode S, Sajikumar S, Frey JU (2005). Mitogen-activated protein kinase-mediated reinforcement of hippocampal early long-term depression by the type IV-specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor rolipram and its effect on synaptic tagging. J Neurosci 25:10664–10670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popoli M, Vocaturo C, Perez J, Smeraldi E, Racagni G (1995). Presynaptic Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II: autophosphorylation and activity increase in the hippocampus after long-term blockade of serotonin reuptake. Mol Pharmacol 48:623–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racca S, Spaccamiglio A, Esculapio P, Abbadessa G, Cangemi L, DiCarlo F, Portaleone P (2005). Effects of swim stress and α-MSH acute pre-treatment on brain 5-HT transporter and corticosterone receptor. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 81:894–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retana-Marquez S, Bonilla-Jaime H, Vazquez-Palacios G, Dominguez-Salazar E, Martinez-Garcia R, Velazquez-Moctezuma J (2003). Body weight gain and diurnal differences of corticosterone changes in response to acute and chronic stress in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology 28:207–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revest JM, Di Blasi F, Kitchener P, Rouge-Pont F, Desmedt A, Turiault M, Tronche F, Piazza PV (2005). The MAPK pathway and Egr-1 mediate stress-related behavioral effects of glucocorticoids. Nat Neurosci 8:664–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter-Levin G, Greenberger V, Segal M (1994). The effects of general and restricted serotonergic lesions on hippocampal electrophysiology and behaviour. Brain Res 642:111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez JJ, Davies HA, Silva AT, De Souza IE, Peddie CJ, Colyer FM, Lancashire CL, Fine A, Errington ML, Bliss TV, Stewart MG (2005). Long-term potentiation in the rat dentate gyrus is associated with enhanced Arc/Arg3.1 protein expression in spines, dendrites and glia. Eur J Neurosci 21:2384–2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, McReynolds JM, McGaugh JL (2004). The basolateral amygdala interacts with the medial prefrontal cortex in regulating glucocorticoid effects on working memory impairment. J Neurosci 24:1385–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkranz JA, Grace AA (1999). Modulation of basolateral amygdala neuronal firing and afferent drive by dopamine receptor activation in vivo. J Neurosci 19:11027–11039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sananbenesi F, Fischer A, Schrick C, Spiess J, Radulovic J (2003). Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in the hippocampus and its modulation by corticotrophin-releasing factor receptor 2: a possible link between stress and fear memory. J Neurosci 23:11436–11443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiapparelli L, Del Rio J, Frechilla D (2005). Serotonin 5-HT receptor blockade enhances Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II function and membrane expression of AMPA receptor subunits in the rat hippocampus: implications for memory formation. J Neurochem 94:884–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidenbecher T, Reymann KG, Balschun D (1997). A post-tetanic time window for the reinforcement of long-term potentiation by appetitive and aversive stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:1494–1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen CP, Tsimberg Y, Salvadore C, Meller E (2004). Activation of Erk and Jnk MAPK pathways by acute swim stress in rat brain regions. BMC Neurosci 5:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shors TJ (2001). Acute stress rapidly and persistently enhances memory formation in the male rat. Neurobiol Learn Mem 75:10–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shors TJ, Dryver E (1994). Effects of stress and long-term potentiation (LTP) on subsequent LTP and the theta burst response in the dentate gyrus. Brain Res 666:232–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shors TJ, Seib TB, Levine S, Thompson RF (1989). Inescapable versus escapable shock modulates long-term potentiation in the rat hippocampus. Science 244:224–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straube T, Korz V, Balschun D, Frey JU (2003). Requirement of β-adrenergic receptor activation and protein synthesis for LTP-reinforcement by novelty in rat dentate gyrus. J Physiol (Lond) 552:953–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweatt JD (2001). The neuronal MAP kinase cascade: a biochemical signal integration system subserving synaptic plasticity and memory. J Neurochem 76:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp T, Rupprecht R, Castrén M, Reul JMHM, Holsboer F (1994). Heterdimerization between mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptor: a new principle of glucocorticoid action n the CNS. Neuron 13:1457–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umriukhin AE, Wigger A, Singewald N, Landgraf R (2002). Hypothalamic and hippocampal release of serotonin in rats bred for hyper- or hypo-anxiety. Stress 5:299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki M, Matsuo R, Fukazawa Y, Ozawa F, Inokuchi K (2001). Regulated expression of an actin-associated protein, synaptopodin, during long-term potentiation. J Neurochem 79:192–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CH, Huang CC, Hsu KS (2004). Behavioral stress modifies hippocampal synaptic plasticity through corticosterone-induced sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. J Neurosci 24:11029–11034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama M, Suzuki E, Sato T, Maruta S, Watanabe S, Myaoka H (2005). Amygdalic levels of dopamine and serotonin rise upon exposure to conditioned fear stress without elevation of glutamate. Neurosci Lett 379:37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandieh Doulabi B, Platvoet-Ter Schiphorst M, Kalsbeek E, Fliers E, Bakker O, Wiersinga WM (2004). Diural variation in rat liver thyroid hormone receptor (TR)-α messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is dependent on the biological clock in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, whereas diurnal variation of TRβ1 mRNA is modified by food intake. Endocrinology 145:1284–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]