Abstract

The capacity for goal-directed behavior requires not only the encoding of the response-outcome relationship but also the ability to resolve conflict induced by competing responses. Recent neuroimaging studies have identified the prefrontal cortex as critical for resolving conflict between competing responses. At present, however, much of this evidence is indirect, and the necessity of dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC) function for the resolution of conflict in goal-directed behavior has not been assessed. Here, we develop a rodent paradigm to investigate response conflict caused by the concurrent activation of a correct and incorrect response. In this paradigm, the outcome of one response also acts as a discriminative stimulus signaling that the other response is correct. Whereas rats with a functional dmPFC are able to resolve this conflict, inactivation of dmPFC using an infusion of muscimol produced a deficit by selectively interfering with their ability to inhibit the incorrect, competing response.

Keywords: dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, response conflict, rat, goal-directed behavior, response inhibition, reversible lesion

Introduction

A goal-directed action is an instrumental response (R) that, rather than being triggered directly by a stimulus, is mediated by an outcome (O) ⇒ R association (Adams and Dickinson, 1981; Colwill and Rescorla, 1985; Balleine and Dickinson, 1998). When the outcome is a current goal, the O ⇒ R association enables the thought of the goal to activate the response required to procure it. In an environment composed of complex contingencies, however, successful goal-directed action often requires the capacity to withhold a response under circumstances where its performance conflicts with our ability to achieve a specific goal (i.e., requires us to resolve the response conflict).

Investigations of the neural processes involved in the capacity to withhold activated but inappropriate conflicting responses have been largely confined to the functional neuroimaging of a variety of human cognitive tasks (e.g., the flanker, Stroop, Simon, and go/no-go tasks) (for review, see Botvinick et al., 2004). Although these studies provide only indirect, correlational evidence, together they suggest that the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and superior frontal gyrus (SFG) play crucial roles in response-conflict resolution (Carter et al., 1998; Botvinick et al., 2004; Kerns et al., 2004; Rushworth et al., 2004).

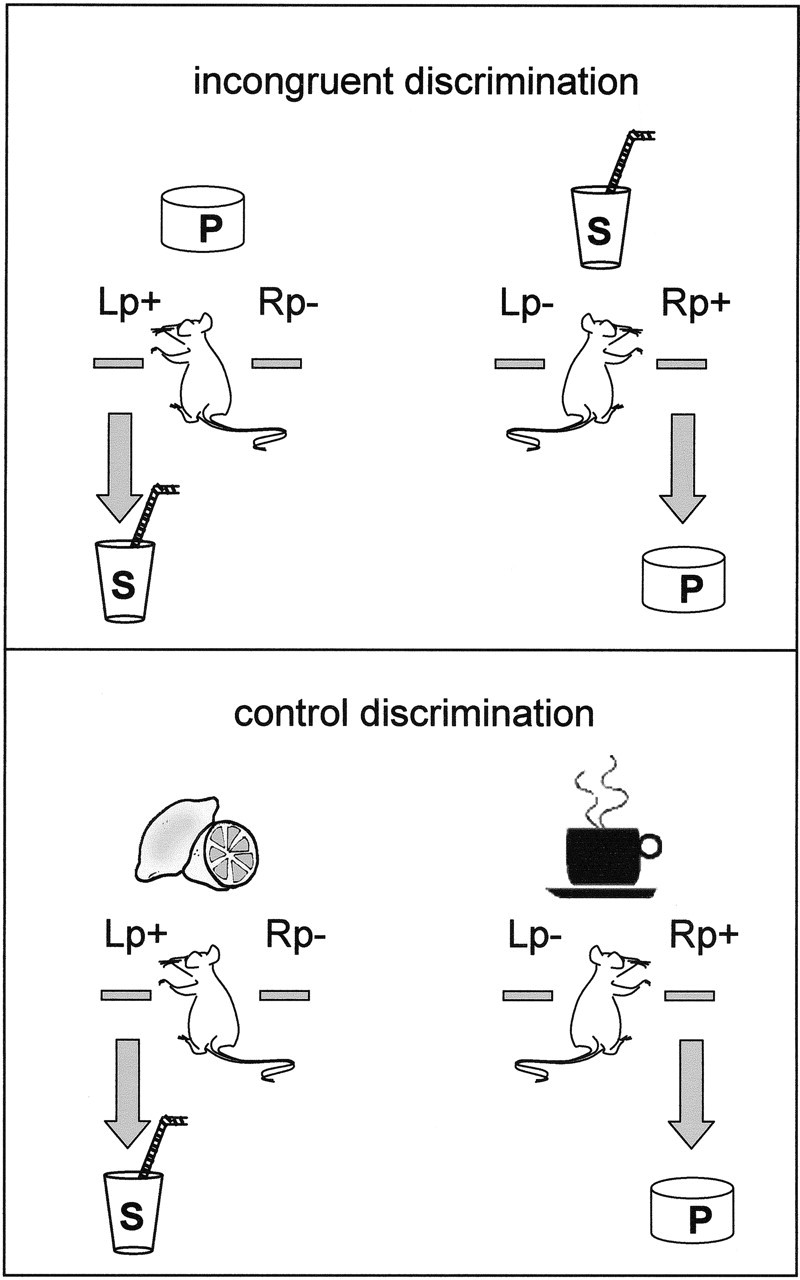

The aim of the present study was to investigate whether the ability to resolve conflict critically depends on the rodent homolog of these structures, namely the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC). To this end, we used a task that we recently developed to investigate conflict resolution in the control of goal-directed action. In this task (see Fig. 1, top panel), rats were trained on a biconditional discrimination in which food events (pellets and sucrose solution) served as discriminative stimuli signaling which of two responses would be rewarded. Conflict was induced by arranging that correct responses in each component of the discrimination were rewarded with the opposite food type as that of the discriminative stimulus. Consequently, each food stimulus should have activated not only the correct response, but also the incorrect response through the O ⇒ R association established when this food acted as the outcome in the other component of the discrimination.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the biconditional discriminations on which the incongruent group (top) and control group (bottom) were trained. In the example of the incongruent discrimination, the pellet (P) discriminative stimulus signals that the left lever press (Lp+) will be rewarded with sugar (S), whereas pressing the right lever (Rp−) will not be rewarded. In contrast, the sugar discriminative stimulus signals that pressing the right lever (Rp+) will be rewarded with a pellet and that pressing the left lever (Lp−) is be unrewarded. As a consequence, the pellet stimulus should come to elicit the correct Lp+ response, reflecting the acquisition of a P ⇒ Lp association, but also the incorrect response, Rp−, through the P ⇒ Rp association acquired when the pellet acted as an outcome for the correct Rp+ response on trials with the sugar stimulus. A corresponding conflict should also be experienced on trials with the sugar stimulus. In the example of the control discrimination, the rat has to learn that lemon signals that pressing the left lever (Lp+) will be rewarded with sugar, whereas the coffee signals that pressing the right lever (Rp+) will be rewarded with a food pellet. Therefore, the lemon should come to elicit the correct response, Lp+, through a lemon ⇒ Lp association, whereas the coffee should come to elicit the right lever press, Rp+, through a coffee ⇒ Rp association. In contrast to the incongruent group however, the coffee and lemon should not activate the incorrect response through O ⇒ R associations, as these foods only functioned as discriminative stimuli and never as outcomes.

The fact that rats readily acquired this incongruent discrimination (Dickinson and de Wit, 2003) suggests that the task engages a mechanism to resolve the conflict. In the present experiment, we investigated whether performance of the incongruent discrimination depends on the functioning of the dmPFC to resolve the conflict, possibly by inhibiting the incorrect responses mediated by the O ⇒ R association. To this end, rats were trained on this discrimination until a high level of performance was established before we reversibly inactivated the dmPFC using an infusion of the GABA receptor agonist muscimol (Martin and Ghez, 1999). We also investigated the effect of this infusion on performance of a control group trained on a standard biconditional discrimination that should not give rise to response conflict (see Fig. 1, bottom). If the dmPFC is involved in conflict resolution, inactivation of this area should have impaired the discriminative performance of the incongruent but not that of the control group.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and apparatus

Fifteen naive male hooded Listar rats, ∼2 months of age at the start of the experiment, were housed in groups of three under a reversed 12 h light/dark cycle. Training and testing took place during the dark phase in six operant chambers (30 cm long × 24 cm wide × 20 cm high) that were housed in sound-attenuating shells (MED Associates, St Albans, VT). Each chamber was equipped with two recessed magazines (5 × 5 cm) that were placed one above the other in the center of the intelligence panel. Magazine-entries were detected by interruption of an infrared photobeam. One magazine contained two adjacent wells into which ∼0.08 ml of 20% maltodextrin starch solutions (Dynamite Energy Fuel) were delivered by two software-operated syringe pumps (MED Associates) during 2 s. The starch solutions were flavored with either 1.5% decaffeinated instant coffee (Sainsbury’s, London, UK) or 5% lemon juice (Crazy Jack, London, UK). Forty-five milligram food pellets (P.J. Noyes, Lancaster, NH) were delivered by a pellet dispenser and 10% sucrose solution by a dipper into the other magazine. In half of the chambers, the magazine for the starch solutions was positioned directly above the magazine for pellets and sucrose, and for the remaining chambers the positioning was reversed. Each chamber also contained two 4.8-cm-wide retractable levers that were placed symmetrically on either side of the magazines. Each chamber was illuminated throughout the experiment by an overhead house light. The chambers were controlled by software written in Visual Basic using the Whisker control system (Cardinal and Aitken, 2001). Experiments were conducted in accordance with the United Kingdom 1986 Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act (project license PPL 80/8442).

Procedure

All animals were placed on a 22.5 h food deprivation schedule 9 d before training and were maintained on this schedule by being given free access to their maintenance diet for 1.5 h each day after completion of the experimental sessions. Tap water was always freely available.

Pretraining.

Before pretraining, the animals were randomly assigned to either the control group (n = 10) or the incongruent group (n = 5). The animals then received two sessions of magazine training during which each of four food types (sucrose solution, food pellets, coffee-flavored starch solution, and lemon-flavored starch solution) was presented 10 times in the magazines on a random time (RT) 60 s schedule with the levers withdrawn. During the second session, the schedule of the next interval of the RT schedule was suspended until a magazine entry had been detected after food delivery.

In the next two sessions, the rats were trained to lever press to receive the foods on a discrete-trial schedule. Trials started with the insertion of one lever and the first lever press was rewarded with the appropriate reward. The first magazine entry after outcome delivery marked the end of the trial and caused the levers to retract. Trials were separated by an intertrial interval (ITI) that varied randomly between 5 and 30 s. Each session consisted of 15 trials with each lever, which were presented in random order. During the final two sessions of pretraining, responding was rewarded on a discrete-trial fixed interval (FI) schedule under which the first lever press 10 s after the start of the trial was rewarded and ended the trial. Throughout the experiment, a session began with the onset of the house-light and terminated with its offset.

For three rats in the incongruent group, presses on the right and left levers were rewarded with the sucrose solution and pellets, respectively, with the remaining two animals receiving the opposite correct lever-outcome assignment. The same was true for four animals in the control group (n = 2 for each response-outcome contingency). Half of the remaining rats in the control group (n = 3) were rewarded with coffee-flavored and lemon-flavored starch solutions for right and left lever presses, respectively. The remaining rats in the control group (n = 3) again received the opposite correct lever-outcome assignment.

Discrimination training.

Discrimination training consisted of ten sessions of 30 trials each. A trial started with the delivery of a particular food type that acted as a discriminative stimulus signaling which lever press would be rewarded on that trial. The first magazine exit after the delivery of a food stimulus led to the insertion of both levers. On each trial, responding on the correct lever was rewarded on a discrete-trial 10 s FI schedule, whereas responding on the incorrect lever was never rewarded and engaged a 2 s change-over delay. The first magazine entry after reward delivery caused both levers to be retracted and initiated an ITI that varied between 1 and 3 min. Each rat was trained with the same lever press-outcome contingency as in instrumental training.

For the incongruent group, half of the trials started with the delivery of a drop of sucrose solution and half with the delivery of a food pellet. These foods signaled that lever presses rewarded with the opposite food type were correct. For example, a pellet stimulus signaled that pressing the left lever would be rewarded with sucrose solution, whereas pressing the right lever would not be rewarded. In contrast, sucrose solution signaled that pressing the right lever would be rewarded with a food pellet in the other component of the discrimination (Fig. 1, top). As a consequence, the presentation of the pellet at the start of a trial should have elicited not only left lever presses through its role as the stimulus signaling that this response was correct but also right lever presses through the O ⇒ R association established when the pellet acted as the outcome of this response on trials with the sucrose stimulus.

The control group was trained on a biconditional discrimination that was designed to be as complex as the incongruent discrimination but without inducing response conflict. For the rats that had previously received instrumental pretraining with food pellets and sucrose solution as the outcomes, lemon and coffee flavored starch solutions acted as the discriminative stimuli. For the remaining animals that had been trained with coffee and lemon solutions as the outcomes, food pellets and sucrose solution now acted as the discriminative stimuli. Therefore, for a subset of the control group, half of the trials started with a drop of starch solution with coffee flavor, which signaled that a right lever press but not a left lever press was correct and would be rewarded with a food pellet, whereas the remaining trials started with a drop of starch solution with lemon flavor, which signaled that a left lever press and not a right lever press would be rewarded with sugar (Fig. 1, bottom). The stimulus-outcome contingencies were arranged so that all foods were paired equally across subjects in the control group. Consequently, the control group, like the incongruent group, had to learn a biconditional discrimination in which the stimulus and outcome were different in each component. However, because the stimuli and outcomes were unique to a component, the presentation of a stimulus in one component should not have induced an incorrect, conflicting response through an O ⇒ R association established in the other component.

After instrumental training, all rats received outcome-mediated reinstatement tests. Because no outcome-mediated reinstatement effect was observed, the results from these tests are not presented.

Surgery.

Rats were anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/kg, i.p; Ketaset) and xylazine (9 mg/kg, i.p.; Rompun), supplemented with ketamine as needed (∼20 mg), and then placed in a stereotaxic frame with the incisor bar set at −3.3. Intracranial double cannulas, were implanted by drilling holes in the skull. Three stainless screws were placed around the burr hole, and bilateral 24-gauge beveled stainless steel guide cannulas (Cooper’s Needleworks, Birmingham, UK) were lowered to the following coordinates: anteroposterior, +1.25, mediolateral, ±0.75, dorsoventral, −3.0 (Paxinos and Watson, 1997). The cannulas were secured with dental cement and 29-gauge wire stylets (Cooper’s Needleworks) were inserted into the length of the guide cannulas to maintain patency. After surgery, all animals were housed individually. They were given 16 d to recover from surgery, during which period they had access to food ad libitum. At the end of this period they were food-deprived again. Water was always freely available.

Infusion procedure.

Either vehicle [sterile phosphate buffer (SPB), pH 7.2] or muscimol (dissolved in SPB, 1 mg/ml) was infused into the target area through 28-gauge internal injectors (Semat Technical, St. Albans, UK), the tips of which stuck out 0.5 mm beyond the cannula guides. All animals initially received one vehicle infusion with SPB to habituate them to the procedure. The rate of infusion was always 0.5 μl/min. Before the discrimination tests, either vehicle or muscimol was injected into the left cannula during 1 min. Subsequently, the injectors were kept in the same position for another minute. Immediately afterward, the same procedure was applied to the right cannula. Finally, the animals were allowed an additional 5 min in their holding cages before they were returned to the operant chambers for testing.

Tests of discriminative performance.

Initially, all animals received two retraining sessions on the discrimination schedules. Subsequently, half of the animals in the control group and three animals in the incongruent group received an infusion of muscimol, whereas the remaining rats received an infusion of vehicle. Immediately after the infusion procedure, all animals received a test of discriminative performance, which was of the same design as the original discrimination training, except that only four trials with each food stimulus were presented in double alternation. The following day, all animals were retested, but without any infusion before the session. On the final day, each animal received the other infusion before receiving a third test. Therefore, the comparison of performance under vehicle/no infusion/muscimol was within-subject.

Histological assessment.

At the end of testing, rats were anesthetized with an overdose of sodium pentobarbitone (1.5 ml per animal, i.p.; Euthatal; Rhône-Mérieux, Hertfordshire, UK) and perfused transcardially with isotonic saline, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde with 0.2% saturated picric acid in 0.2 m phosphate buffer. Brains were then removed and postfixed before being transferred to a 20% sucrose solution in 0.01 m PBS for ∼24 h before being sectioned at 60 μm using a freezing microtome. Every second section was mounted, stained with cresyl violet, and placements verified under a light microscope.

Results

Histology

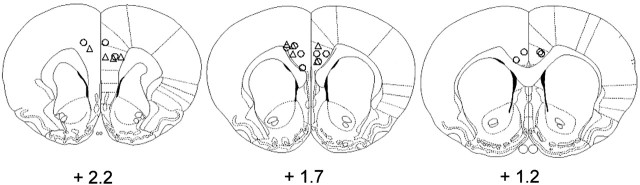

All cannulas were positioned within the dmPFC. Specifically, the tips of the cannulas were located within the ACC (predominantly in Cg2, but also in Cg1) and in the immediately adjacent prelimbic cortex (PL). However, on the basis of the histological assessment of the cannula placements, two animals with subcallosal damage and one with unilateral placement of the cannulas were excluded from the control group, leaving seven animals in this group and five in the incongruent group. All analyses in this results section were conducted to assess performance of these animals (for cannulas placements, see Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Schematics of locations of injector tips within the dmPFC of the control group (circles) and incongruent groups (triangles). The image is reprinted from Paxinos and Watson (1997).

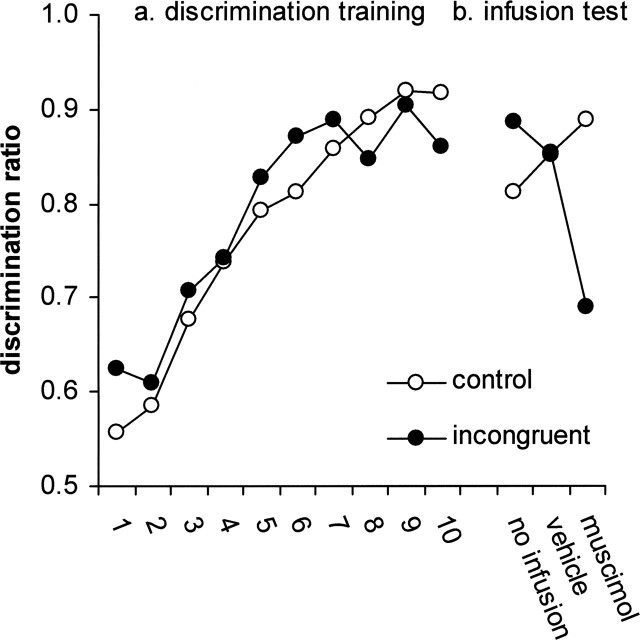

Discrimination training

Discriminative performance was assessed in terms of discrimination ratios (number of correct responses/total number of responses). Therefore, a ratio of 0.5 indicated performance at chance level and a ratio of 1.0 perfect discrimination. Figure 3 (left panel) displays discriminative performance of the incongruent and control groups during the 10 sessions of training in the absence of infusions. Discriminative control was rapidly acquired by both the control and the incongruent group. Although there was a significant effect of session [F(9,90) = 19.01; mean square error (MSE) = 0.008; p < 0.001], neither the effect of group nor the group/session interaction was significant (F values ≤1) suggesting that the performance of the two groups was similar.

Figure 3.

Discrimination training. Mean discrimination ratios for incongruent and control groups during 10 sessions of discrimination training (A) and during test sessions after no infusion, vehicle, or muscimol infusion (B).

Tests of discriminative performance

After discrimination training and surgery, all animals received tests of discriminative performance immediately after muscimol infusion, vehicle infusion, and no infusion into the dmPFC. Figure 3 (right panel) shows that the muscimol infusion selectively disrupted discriminative performance of the incongruent group. Although there was no main effect of the type of infusion on the discrimination ratios [F(2,20) = 2.98; MSE = 0.005; not significant (n.s.)], the group/infusion interaction was significant (F(2,20) = 12.39; MSE = 0.005; p < 0.001). The effect of the type of infusion was significant for the incongruent group (F(2,8) = 10.55; MSE = 0.005; p = 0.006) but not for the control group (F(2,12) = 2.47; MSE = 0.004; n.s.). Post hoc pairwise contrasts (Tukey–Kramer) showed that the discrimination ratios of the incongruent group were reduced after the Muscimol infusion relative to the ratios after the vehicle infusion and no infusion (p values <0.05), which in turn did not differ (n.s.).

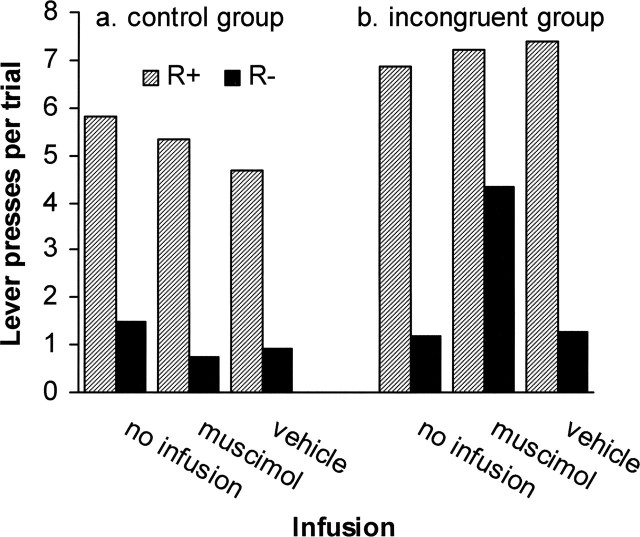

To investigate whether the degradation in performance of the incongruent group after the Muscimol infusion was attributable specifically to an increase in the number of incorrect responses, a decrease in the number of correct responses, or both, an additional analysis was conducted on the total numbers of correct and incorrect responses per trial during the infusion tests (Fig. 4). This analysis included the within-subject factor of response, which distinguished between correct (as signaled by the discriminative stimulus) and incorrect response. The overall significant group/infusion/response interaction (F(2,20) = 4.05; MSE = 1.63; p = 0.034) prompted separate analyses of the two groups. There was a significant infusion/response interaction in the incongruent group (F(2,8) = 5.35; MSE = 1.45; p = 0.034) but not in the control group (F < 1). Post hoc pairwise contrasts (Tukey-Kramer) of the incongruent group demonstrated that whereas levels of correct responding were indistinguishable during the three tests (n.s.), there was a significant increase in incorrect responding after Muscimol infusion relative to responding after vehicle and no infusion (p values <0.05).

Figure 4.

Correct versus incorrect responses during test sessions. Mean numbers of lever presses per trial on the correct and incorrect levers by the control (A) and incongruent groups (B) during test sessions after no infusion, vehicle, or muscimol infusion.

Discussion

We were successful in developing a task that models the essential features of response-conflict resolution by training rats on an incongruent discrimination in which the same events (food pellets and sugar) functioned both as discriminative stimuli and as outcomes for competing responses. When used as discriminanda, the pellet and sugar should have activated the correct response through their roles as discriminative stimuli by signaling which response would be rewarded, but also the incorrect response through their roles as outcomes. In fact, rats rapidly acquired this discrimination and, moreover, performed as well as control rats trained on a standard biconditional discrimination, which was as complex as the incongruent discrimination but should not have given rise to conflict.

Once the rats had acquired the discriminations, temporary inactivation of the dmPFC significantly impaired performance of the incongruent group. The fact that a comparable impairment was not observed in the control group demonstrates that the dmPFC inactivation affected neither the discriminative function nor the reinforcing function of the food pellets and sugar. This demonstration of the involvement of the dmPFC in response conflict resolution by the incongruent group is particularly convincing because the incongruent and control groups performed at a similar level during discrimination training and in the tests after a vehicle and no infusion. Therefore, the selective sensitivity of incongruent performance to dmPFC inactivation did not reflect the fact that this discrimination was a more difficult task than the control discrimination. Moreover, the fact that inactivation of the dmPFC produced an increase in incorrect responding while not affecting correct responding suggests that the conflict was resolved by the inhibition of inappropriate responses rather than the facilitation of correct ones. Therefore, it appears that the dmPFC plays a critical role in resolving response conflict by allowing suppression of the currently inappropriate response that is elicited through O ⇒ R associations.

The dmPFC has previously been shown to play an important role in the acquisition of goal-directed behavior in rats. Pretraining lesions of the PL area of the dmPFC, although not impairing the simple acquisition of instrumental responses, render these responses insensitive to devaluation of the outcome. On the basis of these results it has been speculated that in the absence of a functioning PL area, instrumental responding is acquired by a simple stimulus-response/reinforcement mechanism (Balleine and Dickinson, 1998; Corbit and Balleine, 2003). It is now clear, however, that post-training lesions do not impact on the sensitivity to outcome devaluation, implying that an intact dmPFC is only necessary for the acquisition of goal-directed responses but not for their performance once acquired (Ostlund and Balleine, 2005). In this respect, the role of the dmPFC during acquisition differs from its role in conflict resolution observed in the present study, which was manifest after the acquisition of the discrimination. However, we cannot be certain to what extent the dmPFC areas mediating the acquisition of goal-directed behavior overlap with those involved in conflict resolution; the lesions made in previous studies and that were effective in abolishing goal-directed learning, although not performance, were generally more ventral than the site of infusion in the current study.

A variety of other deficits have been observed after mPFC dysfunction in rats (Dalley et al., 2004). For example, various authors (Walton et al., 2002; Schweimer and Hauber, 2005) have implicated the mPFC area in effort-related decision making through which a low-cost response leading to a small reward is inhibited to perform a high-cost response leading to a large reward. In addition, the mPFC has been implicated in rule-shifting tasks (Joel et al., 1997; Ragozzino et al., 1999; Birrell and Brown, 2000). For example, lesions of the mPFC impaired performance when rats were required to switch between a response versus place discrimination (Ragozzino et al., 1999). Finally, our results concur with the demonstration by Haddon and Killcross (2006) that lesions of the mPFC disrupt the ability of rats to use contextual cues to select among competing responses.

Most theories of PFC function come from research on human and primate cognition. In a currently influential guided activation theory of human PFC function, Miller and Cohen (2001) argued that the PFC maintains activated goal representations that then guide the flow of activity in other brain structures that mediate between stimulus input and response output. This guidance enables the PFC to resolve conflict by augmenting activity in neural pathways that control the correct or appropriate responses for achieving the represented goal. Activity in pathways mediating alternative inappropriate responses is then suppressed through a mechanism of local mutual inhibition. In contrast to this theoretical perspective, we found that the dmPFC appeared to resolve the conflict by inhibiting the performance of the inappropriate or unrewarded response rather than by affecting the ability of the rats to maintain performance of the appropriate or rewarded response.

Alternatively, dynamic filtering theory (Shimamura, 2000) posits that the PFC is specifically involved in the allocation of attention to task-relevant stimulus features. This theory could explain the conflict resolution by the incongruent group if the rats adopted the strategy of attending to different features of the foods depending on their role as a discriminative stimulus or as an outcome. For example, rats could have associated the motivational properties of the outcomes with the responses that earned them (e.g., pellet outcome ⇒ left press) while associating the sensory properties of the discriminative stimuli with the correct responses (e.g., pellet stimulus ⇒ right press) (Dickinson and de Wit, 2003). Consequently, if the dmPFC enabled the rats to attend to and therefore learn selectively about the sensory properties of the pellets and sucrose solution in their role as discriminative stimuli, then the presentation of these stimuli at the start of a trial should not have activated their motivational encoding as an outcome, thereby removing the source of response conflict.

Finally, it is worth noting that, although the effects of muscimol in the current study cannot be localized to any one region of the mPFC, some suggestions can be proposed on the basis of recent arguments from primate research. For example, Rushworth et al. (2004) have proposed that the SFG in primates, an area corresponding roughly to the dorsal part of the PL cortex in rats, is critical for the resolution of response conflict. Furthermore, Hadland et al. (2003) and Hadland et al. (2003) Rushworth et al. (2004) have argued that this function is not shared by the ACC, proposing instead that the ACC is involved in reward-guided action selection rather than response conflict. This account therefore predicts a selective impairment of performance of the incongruent group after dmPFC inactivation because disruption of response selection by the food outcomes through O ⇒ R representations should, if anything, have eliminated the response conflict in the incongruent group and therefore have improved performance. These arguments suggest, therefore, that the effects of the muscimol infusion on response conflict in the current study may have been localized to the dorsal PL, a suggestion that remains to be assessed.

Whatever the mechanism by which the rat dmPFC resolves response conflict, the incongruent task developed here offers a valuable tool for the investigation of conflict resolution in goal-directed behavior. We have demonstrated that the rat dmPFC is critically involved in conflict resolution through suppression of the currently inappropriate response, a finding that accords with findings from human imaging studies of prefrontal executive function.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Merck Sharp & Dohme Educational Sponsorship Program, the University of Cambridge Institute for Behavioral and Clinical Neuroscience with grants from the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust, and Grant MH56446 from the National Institute of Mental Health. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Patricia Di Ciano and Mike Aitken.

References

- Adams CD, Dickinson A (1981). Instrumental responding following reinforcer devaluation. Q J Exp Psychol B 33:109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Balleine BW, Dickinson A (1998). Goal-directed instrumental action: contingency and incentive learning and their cortical substrates. Neuropharmacology 37:407–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrell JM, Brown VJ (2000). Medial frontal cortex mediates perceptual attentional set shifting in the rat. J Neurosci 20:4320–4324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM, Cohen JD, Carter CS (2004). Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: an update. Trends Cogn Sci 8:539–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal RN, Aitken MRF (2001). In: Whisker computer software, version 2.4 :.

- Carter CS, Braver TS, Barch DM, Botvinick MM, Noll D, Cohen JD (1998). Anterior cingulate cortex, error detection, and the online monitoring of performance. Science 280:747–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwill RM, Rescorla RA (1985). Postconditioning devaluation of a reinforcer affects instrumental responding. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process 11:120–132. [Google Scholar]

- Corbit LH, Balleine BW (2003). The role of prelimbic cortex in instrumental conditioning. Behav Brain Res 146:145–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Cardinal RN, Robbins T (2004). Prefrontal executive and cognitive functions in rodents: neural and neurochemical substrates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 28:771–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson A, de Wit S (2003). The interaction between discriminative stimuli and outcomes during instrumental learning. Q J Exp Psychol B 56:127–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddon JE, Killcross AS (2005). Medial prefrontal cortex lesions abolish contextual control of competing responses. J Exp Anal Behav 84:485–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadland KA, Rushworth MF, Gaffan D, Passingham RE (2003). The anterior cingulate and reward-guided selection of actions. J Neurophysiol 89:1161–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joel D, Weiner I, Feldon J (1997). Electrolytic lesions of the medial prefrontal cortex in rats disrupt performance on an analog of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, but do not disrupt latent inhibition: implications for animal models of schizophrenia. Behav Brain Res 85:187–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns JG., Cohen JD., MacDonald AW. III, Cho RY., Stenger VA., Carter CS. (2004). Anterior cingulate conflict monitoring and adjustments in control. Science 303:1023–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JH, Ghez C (1999). Pharmacological inactivation in the analysis of the central control of movement. J Neurosci Methods 86:145–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EK, Cohen JD (2001). An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu Rev Neurosci 24:167–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostlund SB, Balleine BW (2005). Lesions of medial prefrontal cortex disrupt the acquisition but not the expression of goal-directed learning. J Neurosci 25:7763–7770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C (1997). In: The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates, compact Ed 3 San Diego: Academic.

- Ragozzino ME, Detrick S, Kesner RP (1999). Involvement of the prelimbic-infralimbic areas of the rodent prefrontal cortex in behavioral flexibility for place and response learning. J Neurosci 19:4585–4594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushworth MF, Walton ME, Kennerley SW, Bannerman DM (2004). Action sets and decisions in the medial frontal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci 8:410–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweimer J, Hauber W (2005). Involvement of the rat anterior cingulate cortex in control of instrumental responses guided by reward expectancy. Learn Mem 12:334–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura AP (2000). The role of the prefrontal cortex in dynamic filtering. Psychobiology 28:207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Walton ME, Bannerman DM, Rushworth MF (2002). The role of rat medial frontal cortex in effort-based decision making. J Neurosci 22:10996–11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]