Abstract

17β-Estradiol (E2)-induced neuroprotection is dependent on mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) signaling cascades. We sought to determine whether E2 neuroprotective mechanisms are mediated by a unified signaling cascade activated by estrogen receptor (ER)–PI3K interaction within the same population of neurons or whether E2 activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and Akt are independent signaling events in different neuronal populations. Immunoprecipitation of E2-treated cortical neurons was conducted to determine a protein–protein interaction between ER and the PI3K regulatory subunit p85. Subsequently, cortical neurons were treated with E2 alone or in presence of MAPK inhibitors or PI3K inhibitors. Results of these analyses indicated a protein–protein interaction between ER and p85 that was time-dependent and consistent with the temporal profile for generation of Akt (pAkt) and ERK1/2 phosphorylation (pERK1/2). E2-induced phosphorylation of Akt, was first apparent at 10 min and maximal at 30 min. Simultaneously, E2-induced pERK1/2 was first apparent at 5–10 min and maximal at 30 min. Inhibition of PI3K completely blocked E2 activation of pAkt at 10 and 30 min and blocked E2 activation of ERK1/2 at 10 min, which revealed a PI3K-independent activation of ERK at 30 min. Double immunocytochemical labeling for pERK1/2 and pAkt demonstrated that E2 induced both signaling pathways in the same neurons. These results indicate a unified signaling mechanism for rapid E2 action that leads to the coordinated activation of both pERK1/2 and pAkt in the same population of neurons. Implications of these results for understanding estrogen mechanism of action in neurons and therapeutic development are considered.

Keywords: PI3K, MAPK, estrogen receptor, estrogen therapy, estrogen signaling, therapeutic development, Alzheimer's disease, Akt

Introduction

Estrogen effects in the CNS are multifaceted and encompass mechanisms that range from chemical, biochemical, and genomic (Brinton, 2001). Activation of these mechanisms is associated with estrogen promotion of neuronal plasticity (Woolley and McEwen, 1992; Brinton, 1993; Hao et al., 2003), increased cell survival (Brinton et al., 1997), neuronal development (Toran-Allerand, 1984, 1991; Miranda et al., 1994), regulation of apoptosis (Dubal et al., 1999; Pike, 1999; Kaja et al., 2003; Nilsen and Brinton, 2003a), and protection against toxic insults (Gustafsson, 1997; Simpkins et al., 1997; Diaz Brinton et al., 2000). The neuroprotective outcomes of 17β-estradiol (E2) fall within three broad functional categories: antioxidant, defense, and viability (Brinton, 2001). The extent of these functions has not been fully determined, but each appear to make a significant if not obligatory impact on the neuroprotective efficacy of estrogens.

Mechanistically, E2 activates a myriad of signaling cascades in neurons, including mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (Watters et al., 1997; Singer et al., 1999; Singh et al., 1999; Nilsen and Brinton, 2003b), phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) (Singh, 2001; Cardona-Gomez et al., 2002), G-protein-regulated signaling (Kelly et al., 2002), c-Fos (Rudick and Woolley, 2000), protein kinase C (PKC) (Cordey et al., 2003), and Ca2+ influx (Cordey et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2005). Each of these have been associated with E2 regulation of neuronal function and survival (Singh et al., 1994; McEwen et al., 1997; Mor et al., 1999; Woolley, 1999; Brinton, 2001; McEwen, 2001; Nilsen and Brinton, 2002, 2003a). Of these pathways, PI3K has the potential for activating a host of downstream signaling cascades (Yin et al., 1998; Simoncini et al., 2000; Alexaki et al., 2004; Ghisletti et al., 2005). In particular, PI3K recruitment plays a pivotal role in neuroprotection through downstream activation of Akt (Singh, 2001; Znamensky et al., 2003), including E2-mediated protection against β-amyloid or glutamate toxicity (Honda et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2001). In parallel, E2-dependent MAPK activation phosphorylates cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), which increases transcription of genes related to morphogenesis, including spinophilin (Zhao et al., 2005), and the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 (Nilsen and Brinton, 2003a) and Bcl-xl (Pike, 1999), required for neuroprotection. Both the phosphorylated Akt (pAkt) and phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (pERK1/2) pathways are activated within minutes of E2 exposure and have been associated with a membrane site of E2 action (Nilsen and Brinton, 2003b; Toran-Allerand et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2005).

We sought to test the hypothesis that E2 induces the coordinated activation of the pERK1/2 and pAkt signaling cascades as part of a unified signaling cascade in the same population of neurons. To test this hypothesis, we pursued the mechanism of E2 activation of the PI3K signaling pathway by first determining whether the neuronal estrogen receptors (ERs) undergo a protein–protein interaction with the PI3K regulatory subunit p85. Second, we determined the requirement for PI3K for activation of both pAkt and pERK1/2. We further determined the requirement of PI3K for E2 activation and colocalization of pAkt and pERK1/2.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals.

Neural culture materials were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Steroids were dissolved in ethanol and diluted in culture medium with final ethanol concentration of <0.001%. PD 98059 [2-(2-amino-3-methyoxyphenyl)-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one], UO126 [1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis(o-aminophenylmercapto)butadiene], UO124 [1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis(methylthio)butadiene], and wortmannin were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Concentration of E2 (10 nm), wortmannin [30 nm; IC50 of 5 nm for PI3K (Arcaro and Wymann, 1993)], PD 98059 [20 μm; IC50 of 5 μm for MAPK (Borsch-Haubold et al., 1996)], UO126 [20 μm; IC50 of 72 and 58 nm for MAP kinase kinase 1 (MEK1) and MEK2 (Duncia et al., 1998)], and UO124 (20 μm) were based on literature (Qiu et al., 1998; Simoncini et al., 2000, 2004, 2005; Zhu et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2005). The concentration of wortmannin (30 nm) and LY294004 [2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-1(4H)-benzopyran-4-one] (20 μm) used in the present study were selected to maximally inhibit PI3K >99% and to minimize nonspecific inhibition of MAPK <4% (Davies et al., 2000). Cortical neurons were preincubated with inhibitors for 30 min before starting each experiment.

Animal care.

Use of animals was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of University of Southern California (protocol number 10256). Pregnant Sprague Dawley rats were purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley (Indianapolis, IN) and housed under controlled conditions of temperature (22°C), humidity, and light (14/10 h light/dark cycle); water and food were available ad libitum.

Neuronal culture.

Primary cultures of cortical neurons were obtained from embryonic day 18 rat fetuses as described previously (Nilsen and Brinton, 2003b; Brewer et al., 2006). Briefly, cortical cells were dissected and treated with 0.02% trypsin in HBSS (Invitrogen) for 5 min at 37°C and dissociated by repeated passage through a series of fire-polished constricted Pasteur pipettes. Cells were plated on poly-d-lysine-coated 60 mm Falcon (Franklin Lakes, NJ) Petri dishes at a density of 0.5–1 × 105 cells/cm2 for biochemical study. Cells were plated on Nalge Nunc (Naperville, IL) CC2-coated four-well chamber slides at a density of 2–4 × 104 cells/cm2 for morphological study. Neurons were grown in Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10 U/ml penicillin, 10 μg/ml streptomycin, 0.5 mm glutamine, 25 μm glutamate, and 2% B27 (Invitrogen). These culture conditions are well established in multiple laboratories, including our own, to generate cultures that are >95% neuronal and ≤5% glial (Brewer et al., 2006). Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Western blotting.

Cells were washed with cold PBS and incubated in ice-cold lysis buffer consisting of 0.1% SDS, 1% Igepal CA-630 (nonionic, nondenaturing detergent), 0.2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.01% protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 30 min at 4°C. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min, and the concentration of protein in the supernatant was determined by the BCA protein assay (Sigma). Twenty micrograms of total protein from whole-cell lysates were separated under reducing and denaturing conditions by 10% SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 5% skim milk in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS–Tween) for 30 min at room temperature (RT). Membranes were then incubated with anti-pERK1/2 antibody (1:750 in PBS–Tween/1% horse serum; Cell Signaling Technologies, Beverly, MA), total ERK1/2 antibody (C-14) (1:5000 in PBS–Tween/1% horse serum; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-pAKT (1:1000 in PBS–Tween/1% horse serum; Cell Signaling Technologies), or anti-total Akt (1:500 in PBS–Tween/1% horse serum; Cell Signaling Technologies) overnight at 4°C. Membranes were then incubated in horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:5000) or horse anti-mouse IgG (1:3000) for 1 h at RT, and results were visualized by the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Alternately, results were visualized by the TMB peroxidase substrate kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Relative amounts of pERK1/2, pAkt, total ERK1/2, and total pAkt were quantified by optical density analysis using the UN-SCAN-IT gel automated digitizing system (Scion, Frederick, MD). To avoid interassay variations, optical density values of pERK and pAkt were normalized to the optical density values obtained for total ERK or AKT forms. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM for at least three independent experiments.

Immunoprecipitation.

Primary cortical neurons were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed with the following buffer: 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mm EDTA, 100 mm NaCl, 1% Igepal, 1 mm Na3VO4, 50 mm NaF, 0.1 mg/L PMSF, 0.3 mg/L aprotinin, and 0.01% protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma). The immunoprecipitating antibody (1 mg) was added to equal amounts of cortical neuron lysates (0.5–1 mg) in 500 ml of lysis buffer for 1 h at 4°C with gentle rocking. Subsequently, 40 ml of 1:1 Protein-A–agarose was added to the entire mixture and gently rocked for 1 additional hour at 4°C. The mixture was then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed, and the immunoprecipitate was washed three times with 500 ml of washing buffer containing the following: 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mm EDTA, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Igepal, 1 mm Na3VO4, 50 mm NaF, 0.1 mg/L PMSF, 0.3 mg/L aprotinin, and 0.01% protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma). Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated under reducing and denaturing conditions by 10% SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore). Nonspecific binding was blocked with 5% skim milk in PBS–Tween. Membranes were incubated with anti-ER (1:250, Ab-10; clone TE111.5D11; NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA) or anti-p85a (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) antibody. After four 10 min washes in PBS, membranes were incubated in horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:3000), and results were visualized by the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce). Relative amounts of ER and p85 were quantified by optical density analysis using the UN-SCAN-IT gel automated digitizing system (Scion).

Immunocytochemistry.

Cortical neurons cultured on gridded coverslips (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) were exposed to E2 (10 nm) at different time points and paraformaldehyde (4%) fixed. Fixed neurons were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100/PBS. Cells were incubated with anti-pERK1/2 antibody (1:300; Cell Signaling Technologies) and anti-pAkt (1:250; Cell Signaling Technologies) for 3 h at RT followed by incubation, respectively, in fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:250; Vector Laboratories) and in cyanine 3 (Cy3) (1:1000; Amersham Biosciences, Arlington Heights, IL) for 1 h at RT. Cells were mounted in Vectashield mounting medium with 4 min of 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories). Images were taken, and relative immunoreactive intensity was calculated with Slidebook Digital Imaging System (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO). The area of DAPI staining was mapped onto the FITC images to define the nucleus as the region of interest or as a mask to define the cytoplasm as the region of interest. The relative fluorescence intensities of 20 randomly selected cells were normalized to the average fluorescence intensity of control cells and presented as mean ± SEM. The cytoplasm and nucleus were analyzed independently of each other.

Unbiased analysis of pERK1/2- and pAkt-positive cortical neurons.

pERK1/2- and pAkt-positive neurons were detected and quantified using 3i Slidebook 4.1 software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations). For each condition, microscopic fields were randomly selected, and >2000 cells across three separate experiments were analyzed for pAkt and/or pERK1/2 immunoreactivity using an Axiovert 200 M Marianas Digital Microscopy Workstation (Intelligent Imaging Innovations). A binary overlay on a two-dimensional mask was used for each fluorescent marker (DAPI, FITC, and Cy3) to perform an advanced selection of a set of random regions at the same resolution for image analysis. Subsequently, morphometric measurements (area, volume, and estimated surface and perimeter) and fluorescent intensity (mean, minimum, and maximum, colocalization) were performed.

Statistics.

Statistically significant differences between groups were determined for all assays by a one-way ANOVA, followed by a Newman–Keuls post hoc analysis. Data derived from Western blot analyses represent semiquantitative estimates of the amount of a specific protein that was present in a cell extract. The data displayed in graphs are reported as means ± SEM or fold change ± SEM of the actual scanning units derived from the densitometric units normalized to internal standard for protein content.

Results

Protein–protein interaction between ER and the PI3K regulatory subunit p85

To investigate the mechanism by which E2 activates PI3K, immunoprecipitation of ER was performed, followed by Western blot for p85, the regulatory subunit of PI3K (Fig. 1A). To optimize the probability of detecting a protein–protein interaction with ER, we used an ERα-selective antibody (clone TE111.5D11) that is known to also recognize ERβ. The TE111.5D11 clone has greater affinity for ERα, but, because it was developed against the entire ER ligand binding domain (LBD), which has 50–60% homology between ERα and ERβ, it partially also recognizes ERβ (Abbondanza et al., 1993; Mosselman et al., 1996). We reasoned that the use of a LBD region-specific antibody had the probability of enriching the pool of potential ERs binding to p85.

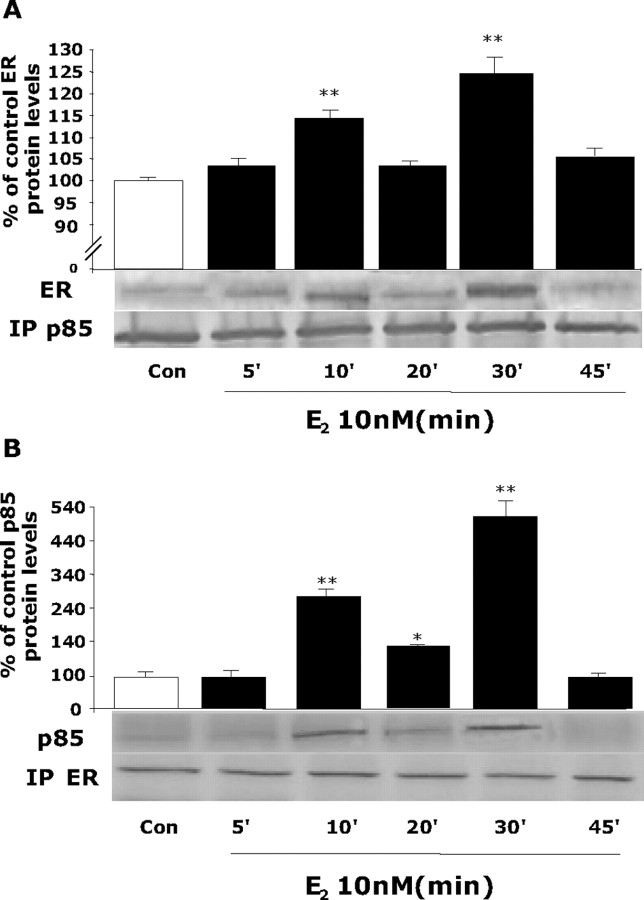

Figure 1.

Dynamic protein–protein interaction between estrogen receptor and PI3K regulatory subunit p85. Rat cortical neurons were exposed to E2 (10 nm) for specific time intervals (0, 5, 10, 20, 30, and 45 min), and lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with either anti-p85, the regulatory subunit of PI3K, or ER (clone TE111.5D11), which principally detects ERα but can partially recognize ERβ. A, Lysates immunoprecipitated with anti-p85, the regulatory subunit of PI3K, were subsequently immunoblotted for detection of ER. A dynamic pattern of p85–ER interaction was apparent in which significant immunoreactivity of ER occurred at 10 and 30 min, with intervening uncoupling at 20 and 45 min. B, To confirm these findings, the corollary experiment was performed. Cortical neuron lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-ER and subsequently immunoblotted with anti- p85. Evidence for an ER protein interaction with p85 occurred at 10 and 30 min, with maximal complexing of the proteins at the 30 min time point. The uncoupling of proteins was apparent at 20 and 45 min. Data are from a single experiment and are representative of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 versus control neurons; **p < 0.01 versus control neurons. Con, Control.

After E2 treatment, ER immunoreactivity was first apparent in the p85 immunoprecipitate at 10 min, returned to baseline at 20 min, and was reestablished at 30 min when the protein–protein interaction was maximal (Fig. 1A). These results were confirmed by immunoprecipitation of p85, followed by Western blot analysis for ER (Fig. 1B). As shown in Figure 1B, immunoreactivity for p85 in the immunoprecipitate of ER was initially apparent at 10 min, maximal at 30 min, and returned to baseline by 45 min. The temporal pattern of protein–protein interaction between ER and p85 indicates a dynamic coupling and uncoupling that is first apparent in ER–p85 coupling by 10 min, followed by decoupling by 20 min, a recoupling by 30 min, and an uncoupling by 45 min. These findings suggest a dynamic shuttling of ER and p85 from uncoupled to coupled states in the presence of E2 in cortical neurons.

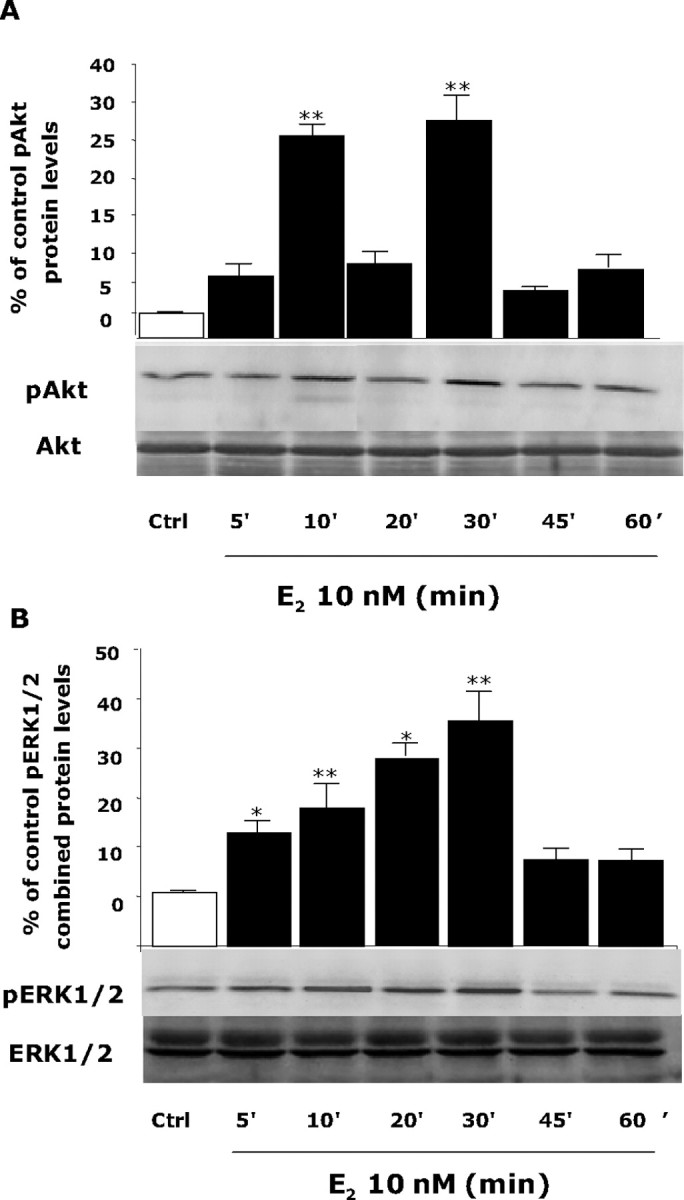

E2 increased Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in a time-dependent manner

To determine the downstream consequence of ER–p85 protein–protein interaction, rat cortical neurons were exposed to E2 (10 nm) at different time points (0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 45, and 60 min), and protein was harvested for Western blot analyses for pAkt and pERK1/2. Activation of pAkt and pERK1/2 were detected with phosphorylated residue-selective antibodies (Fig. 2A, B). Consistent with the protein–protein interaction time course between ER and p85, E2 maximally induced Akt at 10 and 30 min and was uncoupled at 20 min (Fig. 2A). In parallel to activating pAkt, E2 significantly induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation at 5 min, which peaked at 30 min (Fig. 2B). As a control, the same membranes were reblotted for total Akt and ERK1/2, and no difference in protein loading was observed (Fig. 2A, B).

Figure 2.

E2 induces Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in a time-dependent manner. Rat cortical neuron cells were exposed to E2 (10 nm) at specific time intervals (0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 45, and 60 min), and cell lysates were immunoblotted for detection of pAkt or pERK1/2. A, Western Blot analysis showed that E2-induced Akt phosphorylation was first apparent within 5 min of exposure, was maximally induced at 10 min, diminished at 20 min, and reached maximal induction again at 30 min in a temporal pattern, consistent with ER–p85 coupling with significant and maximal efficacy at 10 and 30 min. B, pERK1/2 was linearly and significantly induced at 5 min, continued to rise 10 and 20 min, reached maximal activation at 30 min, and returned to baseline at 45 min. As a loading control, membranes were reblotted for total Akt and ERK1/2. Densitometry of phosphorylated forms were normalized to either total Akt or total ERK1/2, respectively. Expression of total proteins did not change across conditions or time. Data shown are from a single experiment and are representative of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 versus control neurons; **p < 0.01 versus control neurons. Ctrl, Control.

At 10 min, inhibition of PI3K blocked E2 activation of both pAkt and pERK1/2

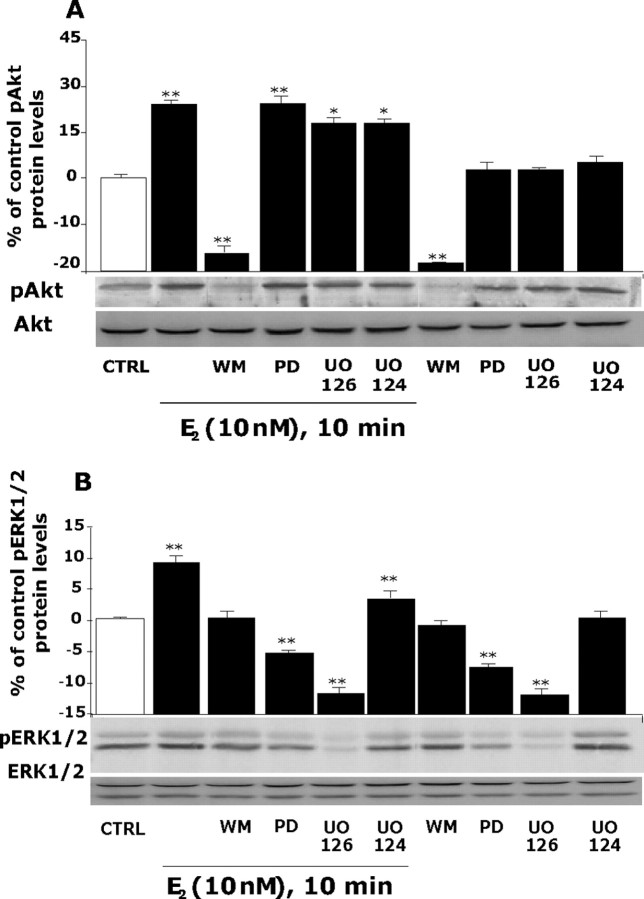

To determine whether PI3K was required for E2 activation of both pAkt and pERK1/2, cortical neurons were treated with a PI3K inhibitor, wortmannin (30 nm), two different MAPK pathway inhibitors, PD 98059 (20 μm) and UO126 (20 μm), or the UO126 negative control, UO124 (20 μm), alone or in combination with E2 (10 nm) for 10 min. To ensure that PI3K effects on pAkt and especially pERK1/2, concentrations of inhibitors that generated maximal inhibition were used to eliminate crosstalk between the PI3K and MAPK signaling pathways (Qiu et al., 1998; Zhu et al., 2004).

As expected, E2-dependent Akt phosphorylation was blocked by the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin (Fig. 3A), whereas MAPK inhibitors did not block E2-induced pAkt. Similarly, blockade of the PI3K pathway by wortmannin completely blocked E2-induced ERK1/2 activation (Fig. 3B). As anticipated, E2-induced pERK1/2 was blocked by the MAPK pathway inhibitors PD 98059 and UO126. The negative control for MEK inhibition, UO124 was without effect alone and did not block either E2-induced pAkt and pERK1/2. Pharmacological specificity at the concentrations used in this study is indicated by the lack of effect of the MAPK inhibitors PD 98059 and UO126, alone or in combination with E2, on PI3K activation of Akt (Fig. 3A). Whereas inhibition of PI3K by wortmannin blocked E2-induced phosphorylation of both pAkt and pERK (Fig. 3A, B), wortmannin alone completely blocked phosphorylation of Akt while only inhibiting the E2-inducible phosphorylation of ERK1/2. These data indicate that wortmannin is a selective inhibitor of only the PI3K-inducible component of pERK1/2 and does not affect the basal non-E2 component of MAPK.

Figure 3.

E2-induced Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation at 10 min was blocked by inhibition of PI3K. Rat cortical neurons were treated with a phosphoinositide PI3K inhibitor [wortmannin (WM)], one of two different MAPK inhibitors [PD 98059 (PD) and UO126], or the negative control (UO124), alone or in combination with E2 (10 nm) for 10 min. A, Western blot analysis indicated that inhibition of PI3K with wortmannin completely blocked E2 activation of pAkt, whereas inhibitors of the MAPK pathway were without effect. B, Inhibition of PI3K with wortmannin (30 nm) completely blocked E2 activation of pERK1/2 at 10 min. Both of the MAP kinase kinase (MEK) inhibitors PD 98059 (20 μm) and UO126 (20 μm) completely blocked E2 induction of pERK1/2. The negative control UO124 (20 μm) was without effect. No change was detected in either total AKT or ERK1/2. Data shown are from a single experiment and are representative of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 versus control neurons; **p < 0.01 versus control neurons. CTRL, Control.

At 30 min, inhibition of PI3K completely blocked E2 activation of pAkt but did not inhibit E2-dependent pERK1/2

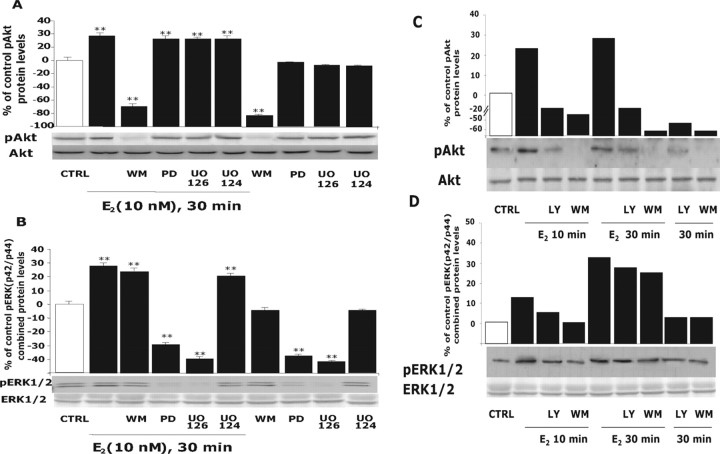

To determine the relationship between E2 activation of PI3K and subsequent activation of the early (10 min) versus late (30 min) phases of pAkt and pERK1/2, cortical neurons were treated with a PI3K inhibitor (wortmannin), two different MAPK pathway inhibitors (PD 98059 and UO126), or a negative control for UO126 (UO124), alone or with E2 (10 nm) for 30 min. As expected, E2-dependent Akt phosphorylation was completely blocked by wortmannin at 30 min, whereas MAPK inhibitors did not significantly inhibit Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of PI3K at 30 min blocked E2 activation of pAkt but not pERK1/2. Rat cortical neurons were treated with either a phosphoinositide PI3K inhibitor [30 nm wortmannin (WM)], one of two different MAPK inhibitors [20 μm PD 98059 (PD) and 20 μm UO126], or the negative control [20 μm UO124], alone or in combination with E2 (10 nm) for 30 min. A, E2 induced a significant increase in pAkt that was blocked by wortmannin at 30 min. As expected, MAPK inhibitors were without effect. B, E2 induced a significant increase in pERK1/2 at 30 min that was impervious to the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin but that showed pharmacological specificity because both MAPK inhibitors PD 98059 and UO124 completely blocked E2-induced pERK1/2. The inactive compound UO126 was with out effect. As a loading control, membranes were immunoblotted for either total Akt or ERK1/2, and the densitometry of phosphorylated forms were normalized to the respective total protein. Expression of total proteins did not change across conditions or time. Data shown are from a single experiment and are representative of three independent experiments. C, To ensure that loss of inhibitory control over E2-induced pERK was not a loss in pharmacological specificity, cortical neurons were exposed to an additional PI3K inhibitor, LY294004 (20 μm) (LY). Cortical neurons were treated with PI3K inhibitors wortmannin (30 nm) or LY294004 (20 μm), alone or in combination with E2 (10 nm) for 10 and 30 min. Western blot analysis indicated that wortmannin and LY294004 completely blocked E2 activation of pAkt at 10 and 30 min. D, Cortical neurons were treated under the same pharmacological conditions as in C. Wortmannin (30 nm) and LY294004 (20 μm) completely blocked E2 activation of pERK1/2 at 10 min as found previously and were without effect at 30 min. Thus, the loss of inhibitory control over PI3K regulation of E2-inducible pERK at 30 min is not a shift in pharmacology but is indicative of a PI3K-independent pathway. Data shown are from a single experiment and are representative of two independent experiments. CTRL, Control. **p < 0.01.

As shown previously, E2 induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation at 30 min. This phosphorylation was completely blocked at 30 min by MAPK inhibitors (PD 98059 and UO126), whereas PI3K inhibitor (wortmannin) did not significantly reduce ERK1/2 activation (5–7% reduction) (Fig. 4B), in contrast to complete inhibition of pERK1/2 by wortmannin at 10 min. Moreover, wortmannin alone did not alter the baseline level of MAPK at either 10 or 30 min.

To confirm that inhibition of PI3K at 30 min was achieved, we used a second PI3K inhibitor, LY294004, and determined the consequences of inhibiting PI3K on E2-inducible Akt and ERK1/2 activation at 10 and 30 min. Western blot analysis indicated that, like wortmannin, LY294004 completely blocked E2 activation of both pAkt (Fig. 4C) and pERK1/2 (Fig. 4D) at 10 min. At 30 min, wortmannin and LY294004 completely blocked E2 activation of Akt but did not inhibit E2 activation of pERK1/2. These data confirm previous results in which inhibition of PI3K blocked E2-inducible ERK1/2 at 10 min and not at 30 min.

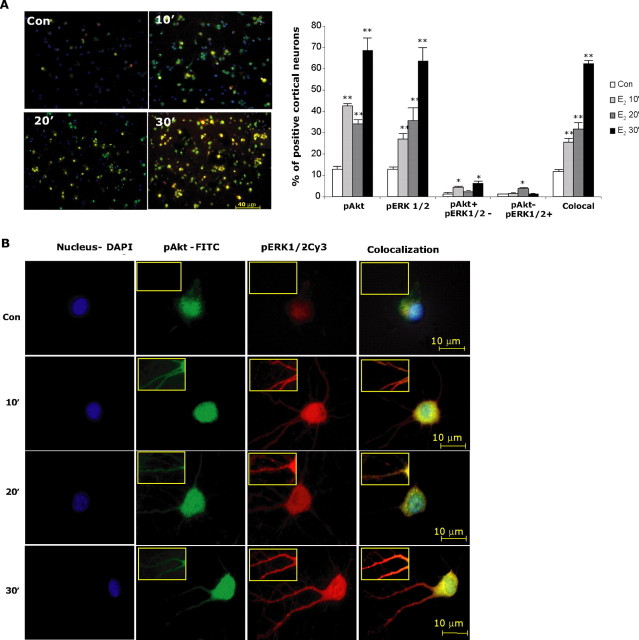

E2-dependent Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation occurred in the same population of cortical neurons in a time-dependent manner

To determine whether E2-induced pAkt and pERK1/2 occurred in the same or in independent populations of neurons, cortical neurons were exposed to E2 (10 nm) at different time points (0, 10, 20, and 30 min) and double labeled immunocytochemically for pAkt and pERK1/2 at each time point (Fig. 5A, B). For each condition, microscopic fields were randomly selected, and >2000 neurons across three separate experiments were analyzed for pAkt and/or pERK1/2 immunoreactivity (Fig. 5A). Quantitative computational threshold analysis of pAkt- and pERK1/2-positive cells was conducted blind to experimental condition (Fig. 5A). After 10 min of E2 exposure, 42% of neurons were positive for pAkt, 27% were positive for pERK1/2, and 25% were positive for both pAkt and pERK. At 20 min, the number of neurons positive for pAkt, pERK1/2, and coexpressing pAkt and pERK were essentially equal at 35%. At 30 min, when both pAkt and pERK1/2 activation were maximal, 68% of neurons were positive for pAkt and 63% of neurons were positive for pERK1/2. Also at 30 min, pERK1/2 and pAkt were coexpressed in nearly the majority of the population, with >62% of neurons simultaneously activated (Fig. 5A). These data are consistent with the Western blot data that show that E2 induced an increase in Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation at 10 and 30 min.

Figure 5.

E2-induced Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation occurs within the same cortical neurons in a time-dependent manner. Rat cortical neurons were exposed to E2 (10 nm) at different time points (0, 10, 20, and 30 min) and immunofluorescently labeled for expression of pAkt (green), pERK1/2 (red), or their coexpression (pAkt–pERK1/2 colocalization in yellow). A, Fluorescent microscopic images show relative density of pAkt- and pERK1/2-positive cells in the E2-treated group versus time 0 min. For each condition, microscopic fields were randomly selected, and >2000 neurons across three separate experiments were analyzed for pAkt and/or pERK1/2 immunoreactivity. E2-induced pAkt and pERK1/2 immunofluorescence was apparent at 10 min and maximal at 30 min, consistent with results of Western blot analyses. Quantitative analyses, shown in bar graph, indicate that the number of E2-induced pAkt-positive neurons occurred at 10 min, followed by a slight but not significant diminution at 20 min and subsequent dramatic rise to the maximal number of pAkt-positive neurons of nearly 70%. These data are consistent with those obtained with Western blot analyses. A significant increase in the number of E2-induced pERK1/2-positive neurons occurred at 10 min, followed by a slight rise at 20 min and subsequent dramatic rise to the maximal number of pERK1/2-positive neurons of 65%. These data are also consistent with those obtained with Western blot analyses. The number of cortical neurons exhibiting colocalization of E2-inducible pAkt and pERK1/2 was significantly increased above control at 10 min, rose slightly at 20 min, and exhibited the largest gain between 20 and 30 min to >60% of cortical neurons exhibiting coexpression of both pAkt and pERK1/2. Data shown are from a single experiment and are representative of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 versus control neurons; **p < 0.01 versus control neurons. B, Immunofluorescent localization of E2-induced pAkt and pERK1/2. Rat cortical neurons were exposed to E2 (10 nm) at different time points (0, 10, 20, and 30 min) and immunofluorescently labeled for expression of pAkt (green), pERK1/2 (red), or their coexpression (pAkt–pERK1/2 colocalization in yellow) and DAPI nuclear counterstain (blue). Insets are higher-magnification images to highlight pAkt and pERK1/2 localization in neuronal processes. E2 activation-induced pAkt and pERK1/2 was apparent within both the cell body and neuronal processes at 10 min of exposure to E2. At 20 min of E2 exposure, pAkt remained apparent within the cell body but was markedly diminished in the processes. In contrast, pERK remained apparent within both the cell body and the processes across the observed time points. At 30 min, pAKT immunofluorescence returned to the processes and pERK immunofluorescence was sustained. Nuclear translocation of both pAkt and pERK was apparent at 10 min, appeared to be reduced at 20 min, and reemerged at 30 min. Data shown are from a single experiment and are representative of immunofluorescent analyses derived from three independent experiments.

To determine the intracellular localization of E2-induced pAkt and pERK1/2 activation within the same cell, 12 randomly selected cortical neurons for each condition were analyzed (Fig. 5B). E2-dependent pAkt activation was localized to the nuclear zone but was also apparent throughout the cytoplasm. It is important to note that E2-induced pAkt localization changed in time-dependent manner. At 10 and 30 min, pAkt was localized in the perinuclear zone and dendritic areas. At 20 min, the pAkt signal was diminished and exclusively localized to the soma. The immunocytochemical profile of an intense and distributed pAkt signal at 10 and 30 min and a diminished pAkt signal at 20 min is consistent with the on–off pattern detected by Western Blot.

E2 activation of ERK1/2 had different kinetics and localization from pAkt (Fig. 5B). The intensity of pERK1/2 signal increased gradually from 10 to 30 min with a time-dependent increase. We further observed that E2 induced pERK translocation to the nucleus, which was consistent with previous observations from our group (Nilsen and Brinton, 2003b). Nuclear localization of pERK1/2, which was evident at the first time point of 10 min, was sustained at 20 and 30 min. In addition to the nuclear localization, pERK1/2 was widely distributed throughout the neuritic extensions branches, with maximal intensity at 30 min. At 30 min, E2 induced a maximal intensity and intracellular distribution of both pAkt and pERK1/2, with an overlapping and elevated fluorescence signal. These immunocytochemical data are consistent with results of Western blot analyses (Fig. 2A, B).

Discussion

Data presented herein demonstrate that E2 activation of PI3K is required for subsequent downstream activation of two membrane-associated signaling pathways, pAkt and pERK1/2, known to be necessary for E2-induced neuroprotection. Our findings indicate that E2 activation of PI3K is mediated by a protein–protein interaction between ER and the regulatory protein of PI3K, p85. The ER–p85 protein–protein interaction leads to Akt and ERK1/2 activation in the same cortical neurons. E2 rapidly activated Akt downstream of PI3K and induced ERK1/2 downstream of MAPK in neurons in a time-dependent manner. Akt activation was apparent after 10 min of E2 exposure and maximal at 30 min. A similar time course of activation was observed for E2 activation of ERK1/2 activation, which was evident at 5–10 min and maximal at 30 min. Quantitative immunocytochemical signal analysis indicated that E2 activation of both Akt and ERK1/2 occurred in the same population of cortical neurons.

PI3K activation of Akt was biphasic in cortical neurons. The biphasic activation pattern was consistent with the coupling and uncoupling of ER and p85 proteins. A direct relationship between PI3K activation and Akt activation was evident at both 10 and 30 min because inhibition of PI3K completely blocked E2-induced pAkt at both points. Our finding of a protein–protein interaction between ER and p85 is consistent with findings of Simoncini et al. (2000). These investigators found that ER interacts with p85 in endothelial cells in a ligand-dependent manner and was required for E2 activation of Akt. Interestingly, the kinetics of E2 activation of pAkt in cortical neurons was more rapid than that found in vascular epithelium (Simoncini et al., 2000). In neurons, several investigators have shown that E2 activation of the PI3K–Akt pathway was required for protection against glutamate and β-amyloid induced neurotoxicity (Honda et al., 2000; Singh, 2001). One mechanism by which Akt imparts protection against toxic insults is through phosphorylation of the proapoptotic protein BAD (Bcl-2-associated death protein), preventing its coupling with Bcl-2 (Datta et al., 1997).

Previous studies from our group demonstrated that activation of L-type calcium channels was an upstream requirement for E2 activation of the Src–MAPK signaling pathway (Wu et al., 2005). In other systems, L-type calcium channel activation via the PI3K pathway mediated IGF-1- and angiotensin II-induced activation of L-type Ca2+ channels in neurons and myocytes, respectively (Blair and Marshall, 1997; Quignard et al., 2001; Sanna et al., 2002). Interestingly, IGF receptor-mediated neuron survival required PI3K–Akt-mediated L-type Ca2+ channel activation (Blair et al., 1999). Our previous findings demonstrated that, in hippocampal neurons, E2-induced Ca2+ influx led to a rise in both dendritic and nuclear Ca2+(Zhao et al., 2005). The rise in nuclear Ca2+ led to CREB activation (Zhao et al., 2005). We further found that E2-induced Ca2+ influx was via L-type Ca2+ channels, which were required for downstream activation of Src–ERK–CREB signaling pathway and Bcl-2 expression (Wu et al., 2005). Our working hypothesis is that E2-induced activation of L-type Ca2+ channels is through PI3K activation of PKC. Our laboratory and others have demonstrated an E2 time-dependent interaction between PKC, Ca2+ influx, and ERK1/2 activation (Cordey et al., 2003; Setalo et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2005). PI3K activation of PKC is well documented through phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (Wymann and Pirola, 1998) and diacylglycerol (Standaert et al., 1996), as well as Akt/protein kinase B.

The data indicate both PI3K-dependent and -independent forms of E2-inducible pERK1/2. E2 activation of pERK1/2 at 10 min is PI3K dependent, whereas activation of pERK1/2 at 30 min is PI3K independent. Inhibitors of PI3K completely blocked E2-induced ERK1/2 activation at 10 min yet did not inhibit E2-inducible pERK1/2 at 30 min. The coupling of ER–p85 protein at 10 min and the rise of pERK1/2, which was blocked in the presence of PI3K inhibitors at 10 min, are consistent with a requirement of PI3K for downstream activation of ERK1/2 at the early time point. Subsequent to this early response when ER–p85 proteins were uncoupled, a PI3K-independent E2-inducible pERK1/2 was manifested. It is important to note that wortmannin inhibits PI3K activity by binding within the ATP binding pocket of PI3K catalytic subunit (Walker et al., 2000) and competes with phosphatidylinositol(4,5)–P2 binding enzyme complex (Wymann et al., 1996) through a covalent bond that irreversibly inhibits the catalytic subunit p110 without modifying the p85 structure (Ui et al., 1995). It remains to be determined whether our finding of a PI3K-dependent and -independent component of E2-inducible pERK1/2 is an artifact of blocking an E2 preferred signaling pathway or whether the conditions of these experiments unmasked a bona fide alternate route of E2 activation of pERK1/2.

Although the pharmacological analyses indicated the requirement of PI3K for E2 activation of both early inducible pERK1/2 and Akt, there was a 5 min delay in detecting the earliest generation of pAkt and pERK1/2 and detection of the ER–p85 complex. The ER–p85 complex was first evident at 10 min, whereas E2 activation of ERK was significantly increased at 5 min and pAkt showed a modest rise. Two potential reasons exist for the difference in time course of activation between the ERK signal and the detection of the ER–p85 interaction: (1) different sensitivity in detection threshold for the antibodies with the pERK antibody having greater sensitivity than the antibody binding to p85 or ER and (2) pERK is activated independently of PI3K. To address option 2, we conducted an experiment in which we assessed the impact of blocking PI3K on both Akt and ERK activation at 5 min (data not shown). Results of those experiments indicated that wortmannin blocked activation of both pAkt and pERK activation at 5 min. Pharmacologically, the data indicate that inhibition of PI3K activation inhibits both E2-inducible pAkt and pERK. This finding supports the supposition that the inability to detect significant protein interaction at 5 min is a function of sensitivity of detection rather than an alternate upstream activator. This hypothesis is partially supported by the findings of Simoncini et al. (2003) who reported that, in vascular epithelial cells, ER recruits a small fraction of the available PI3K by 30 min of E2 exposure. Given that ER is in low abundance and that ER recruits a small fraction of the available pool of p85, detection may require an accumulation of ER–p85 complexes that reach detectable abundance by 10 min. Although the data do not directly demonstrate causality between the protein interaction between ER and p85 and subsequent activation of ERK and Akt, the data do demonstrate causality between activation of PI3K and E2 activation of both ERK and Akt. The present findings are consistent with the postulate that ER interacts with the regulatory p85 subunit of PI3K, which determines the translocation of the catalytic p110 domain to the membrane and subsequent interaction with PI3K substrates, and further that the ER/p85 protein interaction is a critical and necessary step required for PI3K-dependent activation of ERK and Akt.

Results of double-labeling immunocytochemical analyses indicated an increase in the absolute number of neurons that expressed Akt and pERK1/2. Moreover, colocalization within the same neurons showed a comparable rise over time. Colocalization of both the pERK1/2 and pAkt was greatest at 30 min, when activation of these signaling pathways was also maximal. At 30 min, 68% of cortical neurons exhibited expression of both pAkt and pERK1/2. This finding suggests that, regardless of the complexity of activation, PI3K activation of these two signaling pathways and their cellular localization are tightly coupled in cortical neurons.

In conclusion, we sought to determine whether a single mechanism could serve as a unifying mechanism for E2 activation of Akt and MAPK, two signaling cascades demonstrated to be required for estrogen-inducible neuroprotection against degenerative insults (McEwen, 1992; Toran-Allerand et al., 1999; Brinton, 2001; Nilsen et al., 2002; Yi et al., 2005). Results of this investigation demonstrate that a protein–protein interaction between estrogen receptor and the regulatory subunit p85 of PI3K leads to activation of both the Akt and MAPK signaling pathways in cortical neurons. Moreover, E2 activation of Akt and MAPK occurred in the same neurons via a PI3K-dependent mechanism. Functionally, activation of Akt and MAPK provides a coordinated response that results in inactivation of the proapoptotic protein BAD and activation of antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-II and Bcl-x (Pike, 1999; Singh, 2001; Nilsen and Brinton, 2003a; Simpkins et al., 2005). Moreover, E2 activation of ERK-dependent responses associated with memory function, such as morphogenesis, CREB activation, and long-term potentiation, creates a coordinated response network that promotes survival of neurons while simultaneously promoting their function and neural network integration. From a translational perspective, activation of PI3K, Akt, and MAPK signaling cascades in neurons provide a unified mechanistic understanding of estrogen outcomes in neocortex and could serve as an initial in vitro screen for additional development of therapeutics to promote estrogen responses in hippocampus and cortex.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Aging, National Institute of Mental Health, the Kenneth T. and Eileen L. Norris Foundation, and the L. K. Whittier Foundation (R.D.B.). We thank Rana Masri for help in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- Abbondanza et al., 1993.Abbondanza C, de Falco A, Nigro V, Medici N, Armetta I, Molinari AM, Moncharmont B, Puca GA. Characterization and epitope mapping of a new panel of monoclonal antibodies to estradiol receptor. Steroids. 1993;58:4–12. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(93)90011-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexaki et al., 2004.Alexaki VI, Charalampopoulos I, Kampa M, Vassalou H, Theodoropoulos P, Stathopoulos EN, Hatzoglou A, Gravanis A, Castanas E. Estrogen exerts neuroprotective effects via membrane estrogen receptors and rapid Akt/NOS activation. FASEB J. 2004;18:1594–1596. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1495fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcaro and Wymann, 1993.Arcaro A, Wymann MP. Wortmannin is a potent phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor: the role of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate in neutrophil responses. Biochem J. 1993;296:297–301. doi: 10.1042/bj2960297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair and Marshall, 1997.Blair LA, Marshall J. IGF-1 modulates N and L calcium channels in a PI 3-kinase-dependent manner. Neuron. 1997;19:421–429. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80950-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair et al., 1999.Blair LA, Bence-Hanulec KK, Mehta S, Franke T, Kaplan D, Marshall J. Akt-dependent potentiation of L-channels by insulin-like growth factor-1 is required for neuronal survival. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1940–1951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-01940.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsch-Haubold et al., 1996.Borsch-Haubold AG, Kramer RM, Watson SP. Inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase does not impair primary activation of human platelets. Biochem J. 1996;318:207–212. doi: 10.1042/bj3180207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer et al., 2006.Brewer G, Reichensperger JD, Brinton RD. Prevention of age-related dysregulation of calcium dynamics by estrogen in neurons. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:306–317. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinton, 1993.Brinton RD. 17β-Estradiol induction of filopodial growth in cultured hippocampal neurons within minutes of exposure. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1993;4:36–46. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1993.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinton, 2001.Brinton RD. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of estrogen regulation of memory function and neuroprotection against Alzheimer's disease: recent insights and remaining challenges. Learn Mem. 2001;8:121–133. doi: 10.1101/lm.39601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinton et al., 1997.Brinton RD, Tran J, Proffitt P, Montoya M. 17beta-Estradiol enhances the outgrowth and survival of neocortical neurons in culture. Neurochem Res. 1997;22:1339–1351. doi: 10.1023/a:1022015005508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona-Gomez et al., 2002.Cardona-Gomez GP, Mendez P, Garcia-Segura LM. Synergistic interaction of estradiol and insulin-like growth factor-I in the activation of PI3K/Akt signaling in the adult rat hypothalamus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2002;107:80–88. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00449-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordey et al., 2003.Cordey M, Gundimeda U, Gopalakrishna R, Pike CJ. Estrogen activates protein kinase C in neurons: role in neuroprotection. J Neurochem. 2003;84:1340–1348. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta et al., 1997.Datta SR, Dudek H, Tao X, Masters S, Fu H, Gotoh Y, Greenberg ME. Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell. 1997;91:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies et al., 2000.Davies SP, Reddy H, Caivano M, Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem J. 2000;351:95–105. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz Brinton et al., 2000.Diaz Brinton R, Chen S, Montoya M, Hsieh D, Minaya J, Kim J, Chu HP. The women's health initiative estrogen replacement therapy is neurotrophic and neuroprotective. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:475–496. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubal et al., 1999.Dubal DB, Shughrue PJ, Wilson ME, Merchenthaler I, Wise PM. Estradiol modulates bcl-2 in cerebral ischemia: a potential role for estrogen receptors. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6385–6393. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06385.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncia et al., 1998.Duncia JV, Santella JB, III, Higley CA, Pitts WJ, Wityak J, Frietze WE, Rankin FW, Sun JH, Earl RA, Tabaka AC, Teleha CA, Blom KF, Favata MF, Manos EJ, Daulerio AJ, Stradley DA, Horiuchi K, Copeland RA, Scherle PA, Trzaskos JM, et al. MEK inhibitors: the chemistry and biological activity of U0126, its analogs, and cyclization products. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1998;8:2839–2844. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00522-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghisletti et al., 2005.Ghisletti S, Meda C, Maggi A, Vegeto E. 17beta-estradiol inhibits inflammatory gene expression by controlling NF-kappaB intracellular localization. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2957–2968. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.8.2957-2968.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, 1997.Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptor beta—getting in on the action? Nat Med. 1997;3:493–494. doi: 10.1038/nm0597-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao et al., 2003.Hao J, Janssen WG, Tang Y, Roberts JA, McKay H, Lasley B, Allen PB, Greengard P, Rapp PR, Kordower JH, Hof PR, Morrison JH. Estrogen increases the number of spinophilin-immunoreactive spines in the hippocampus of young and aged female rhesus monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 2003;465:540–550. doi: 10.1002/cne.10837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda et al., 2000.Honda K, Sawada H, Kihara T, Urushitani M, Nakamizo T, Akaike A, Shimohama S. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase mediates neuroprotection by estrogen in cultured cortical neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2000;60:321–327. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(20000501)60:3<321::AID-JNR6>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaja et al., 2003.Kaja S, Yang SH, Wei J, Fujitani K, Liu R, Brun-Zinkernagel AM, Simpkins JW, Inokuchi K, Koulen P. Estrogen protects the inner retina from apoptosis and ischemia-induced loss of Vesl-1L/Homer 1c immunoreactive synaptic connections. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3155–3162. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly et al., 2002.Kelly MJ, Qiu J, Wagner EJ, Ronnekleiv OK. Rapid effects of estrogen on G protein-coupled receptor activation of potassium channels in the central nervous system (CNS) J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;83:187–193. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(02)00249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, 1992.McEwen BS. Non-genomic and genomic effects of steroids on neural activity. Trends Pharmacol. 1992;12:141–147. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90531-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, 2001.McEwen BS. Invited review: estrogens effects on the brain: multiple sites and molecular mechanisms. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:2785–2801. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.6.2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen et al., 1997.McEwen BS, Alves SE, Bulloch K, Weiland NG. Ovarian steroids and the brain: implications for cognition and aging. Neurology. 1997;48:S8–S15. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5_suppl_7.8s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda et al., 1994.Miranda RC, Sohrabji F, Toran-Allerand D. Interactions of estrogen with the neurotrophins and their receptors during neural development. Horm Behav. 1994;28:367–375. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1994.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor et al., 1999.Mor G, Nilsen J, Horvath T, Bechmann I, Brown S, Garcia-Segura LM, Naftolin F. Estrogen and microglia: a regulatory system that affects the brain. J Neurobiol. 1999;40:484–496. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19990915)40:4<484::aid-neu6>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosselman et al., 1996.Mosselman S, Polman J, Dijkema R. ER beta: identification and characterization of a novel human estrogen receptor. FEBS Lett. 1996;392:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00782-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen and Brinton, 2002.Nilsen J, Brinton RD. Impact of progestins on estradiol-potentiation of the glutamate calcium response. NeuroReport. 2002;13:825–830. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200205070-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen et al., 2002.Nilsen J, Chen S, Brinton RD. Dual action of estrogen on glutamate-induced calcium signaling: mechanisms requiring interaction between estrogen receptors and src/mitogen activated protein kinase pathway. Brain Res. 2002;930:216–234. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02254-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen and Brinton, 2003a.Nilsen J, Brinton RD. Mechanism of estrogen-mediated neuroprotection: regulation of mitochondrial calcium and Bcl-2 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003a;100:2842–2847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0438041100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen and Brinton, 2003b.Nilsen J, Brinton RD. Divergent impact of progesterone and medroxyprogesterone acetate (Provera) on nuclear mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003b;100:10506–10511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1334098100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike, 1999.Pike CJ. Estrogen modulates neuronal Bcl-xL expression and beta-amyloid-induced apoptosis: relevance to Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 1999;72:1552–1563. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.721552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu et al., 1998.Qiu YH, Zhao X, Hayes RL, Perez-Polo JR, Pike BR, Huang L, Clifton GL, Yang K. Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase by brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene transfection in septo-hippocampal cultures. J Neurosci Res. 1998;52:192–200. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980415)52:2<192::AID-JNR7>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quignard et al., 2001.Quignard JF, Mironneau J, Carricaburu V, Fournier B, Babich A, Nurnberg B, Mironneau C, Macrez N. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma mediates angiotensin II-induced stimulation of L-type calcium channels in vascular myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32545–32551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102582200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudick and Woolley, 2000.Rudick CN, Woolley CS. Estradiol induces a phasic Fos response in the hippocampal CA1 and CA3 regions of adult female rats. Hippocampus. 2000;10:274–283. doi: 10.1002/1098-1063(2000)10:3<274::AID-HIPO8>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna et al., 2002.Sanna PP, Cammalleri M, Berton F, Simpson C, Lutjens R, Bloom FE, Francesconi W. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is required for the expression but not for the induction or the maintenance of long-term potentiation in the hippocampal CA1 region. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3359–3365. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03359.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setalo et al., 2005.Setalo G, Jr, Singh M, Nethrapalli IS, Toran-Allerand CD. Protein kinase C activity is necessary for estrogen-induced Erk phosphorylation in neocortical explants. Neurochem Res. 2005;30:779–790. doi: 10.1007/s11064-005-6871-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoncini et al., 2000.Simoncini T, Hafezi-Moghadam A, Brazil DP, Ley K, Chin WW, Liao JK. Interaction of oestrogen receptor with the regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase. Nature. 2000;407:538–541. doi: 10.1038/35035131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoncini et al., 2003.Simoncini T, Rabkin E, Liao JK. Molecular basis of cell membrane estrogen receptor interaction with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in endothelial cells, arteriosclerosis, thrombosis and vascular biology. 2003;23:198–203. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000053846.71621.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoncini et al., 2004.Simoncini T, Mannella P, Fornari L, Caruso A, Willis MY, Garibaldi S, Baldacci C, Genazzani AR. Differential signal transduction of progesterone and medroxyprogesterone acetate in human endothelial cells. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5745–5756. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoncini et al., 2005.Simoncini T, Fornari L, Mannella P, Varone G, Caruso A, Garibaldi S, Genazzani AR. Differential estrogen signaling in endothelial cells upon pulsed or continuous administration. Maturitas. 2005;50:247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpkins et al., 1997.Simpkins JW, Rajakumar G, Zhang YQ, Simpkins CE, Greenwald D, Yu CJ, Bodor N, Day AL. Estrogens may reduce mortality and ischemic damage caused by middle cerebral artery occlusion in the female rat. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:724–730. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.5.0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpkins et al., 2005.Simpkins JW, Wang J, Wang X, Perez E, Prokai L, Dykens JA. Mitochondria play a central role in estrogen-induced neuroprotection. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2005;4:69–83. doi: 10.2174/1568007053005073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer et al., 1999.Singer CA, Figueroa-Masot XA, Batchelor RH, Dorsa DM. The mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway mediates estrogen neuroprotection after glutamate toxicity in primary cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2455–2463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-07-02455.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, 2001.Singh M. Ovarian hormones elicit phosphorylation of Akt and extracellular-signal regulated kinase in explants of the cerebral cortex. Endocrine. 2001;14:407–415. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:14:3:407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh et al., 1994.Singh M, Meyer EM, Millard WJ, Simpkins JW. Ovarian steroid deprivation results in a reversible learning impairment and compromised cholinergic function in female Sprague-Dawley rats. Brain Res. 1994;644:305–312. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91694-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh et al., 1999.Singh M, Setalo G, Jr, Guan X, Warren M, Toran-Allerand CD. Estrogen-induced activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in cerebral cortical explants: convergence of estrogen and neurotrophin signaling pathways. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1179–1188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-04-01179.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standaert et al., 1996.Standaert ML, Avignon A, Yamada K, Bandyopadhyay G, Farese RV. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor, wortmannin, inhibits insulin-induced activation of phosphatidylcholine hydrolysis and associated protein kinase C translocation in rat adipocytes. Biochem J. 1996;313:1039–1046. doi: 10.1042/bj3131039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toran-Allerand, 1984.Toran-Allerand CD. On the genesis of sexual differentiation of the general nervous system: morphogenetic consequences of steroidal exposure and possible role of alpha-fetoprotein. Prog Brain Res. 1984;61:63–98. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)64429-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toran-Allerand, 1991.Toran-Allerand CD. Organotypic culture of the developing cerebral cortex and hypothalamus: relevance to sexual differentiation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1991;16:7–24. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(91)90068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toran-Allerand et al., 1999.Toran-Allerand CD, Singh M, Setalo G., Jr Novel mechanisms of estrogen action in the brain: new players in an old story. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1999;20:97–121. doi: 10.1006/frne.1999.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toran-Allerand et al., 2002.Toran-Allerand CD, Guan X, MacLusky NJ, Horvath TL, Diano S, Singh M, Connolly ES, Jr, Nethrapalli IS, Tinnikov AA. ER-X: a novel, plasma membrane-associated, putative estrogen receptor that is regulated during development and after ischemic brain injury. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8391–8401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08391.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toran-Allerand et al., 2005.Toran-Allerand CD, Tinnikov AA, Singh RJ, Nethrapalli IS. 17α-Estradiol: a brain active estrogen? Endocrinology. 2005;146:3843–3850. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ui et al., 1995.Ui M, Okada T, Hazeki K, Hazeki O. Wortmannin as a unique probe for an intracellular signalling protein, phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:303–307. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker et al., 2000.Walker EH, Pacold ME, Perisic O, Stephens L, Hawkins PT, Wymann MP, Williams RL. Structural determinants of phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibition by wortmannin, LY294002, quercetin, myricetin, and staurosporine. Mol Cell. 2000;6:909–919. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(05)00089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watters et al., 1997.Watters JJ, Campbell JS, Cunningham MJ, Krebs EG, Dorsa DM. Rapid membrane effects of steroids in neuroblastoma cells: effects of estrogen on mitogen activated protein kinase signalling cascade and c-fos immediate early gene transcription. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4030–4033. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.9.5489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley, 1999.Woolley CS. Effects of estrogen in the CNS. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:349–354. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley and McEwen, 1992.Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Estradiol mediates fluctuation in hippocampal synapse density during the estrous cycle in the adult rat. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2549–2554. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02549.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu et al., 2005.Wu TW, Wang JM, Chen S, Brinton RD. 17Beta-estradiol induced Ca2+ influx via L-type calcium channels activates the Src/ERK/cyclic-AMP response element binding protein signal pathway and BCL-2 expression in rat hippocampal neurons: a potential initiation mechanism for estrogen-induced neuroprotection. Neuroscience. 2005;135:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wymann and Pirola, 1998.Wymann MP, Pirola L. Structure and function of phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1436:127–150. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wymann et al., 1996.Wymann MP, Bulgarelli-Leva G, Zvelebil MJ, Pirola L, Vanhaesebroeck B, Waterfield MD, Panayotou G. Wortmannin inactivates phosphoinositide 3-kinase by covalent modification of Lys-802, a residue involved in the phosphate transfer reaction. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1722–1733. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi et al., 2005.Yi KD, Chung J, Pang P, Simpkins JW. Role of protein phosphatases in estrogen-mediated neuroprotection. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7191–7198. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1328-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin et al., 1998.Yin Y, Terauchi Y, Solomon GG, Aizawa S, Rangarajan PN, Yazaki Y, Kadowaki T, Barrett JC. Involvement of p85 in p53-dependent apoptotic response to oxidative stress. Nature. 1998;391:707–710. doi: 10.1038/35648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao et al., 2005.Zhao L, Chen S, Ming Wang J, Brinton RD. 17β-Estradiol induces Ca2+ influx, dendritic and nuclear Ca2+ rise and subsequent cyclic AMP response element-binding protein activation in hippocampal neurons: a potential initiation mechanism for estrogen neurotrophism. Neuroscience. 2005;132:299–311. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu et al., 2004.Zhu Y, Culmsee C, Klumpp S, Krieglstein J. Neuroprotection by transforming growth factor-beta1 involves activation of nuclear factor-kappaB through phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase/Akt and mitogen-activated protein kinase-extracellular-signal regulated kinase1,2 signaling pathways. Neuroscience. 2004;123:897–906. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Znamensky et al., 2003.Znamensky V, Akama KT, McEwen BS, Milner TA. Estrogen levels regulate the subcellular distribution of phosphorylated Akt in hippocampal CA1 dendrites. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2340–2347. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02340.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]