Abstract

Mitochondrial dysfunction has been implicated in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer's disease (AD) brains. To unravel the mechanism(s) underlying this dysfunction, we demonstrate that phospholipases A2 (PLA2s), namely the cytosolic and the calcium-independent PLA2s (cPLA2 and iPLA2), are key enzymes mediating oligomeric amyloid-β peptide (Aβ1–42)-induced loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and increase in production of reactive oxygen species from mitochondria in astrocytes. Whereas the action of iPLA2 is immediate, the action of cPLA2 requires a lag time of ∼12–15 min, probably the time needed for initiating signaling pathways for the phosphorylation and translocation of cPLA2 to mitochondria. Western blot analysis indicated the ability of oligomeric Aβ1–42 to increase phosphorylation of cPLA2 in astrocytes through the NADPH oxidase and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. The involvement of PLA2 in Aβ1–42-mediated perturbations of mitochondrial function provides new insights to the decline in mitochondrial function, leading to impairment in ATP production and increase in oxidative stress in AD brains.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease (AD), amyloid-β peptide (Aβ), phospholipase A2 (PLA2), mitochondrial membrane potential, reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress

Introduction

One of the central hypotheses underlying the pathophysiology of Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the production of cytotoxic amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides that impairs neuronal activities, leading to decline in memory and cognitive function (Selkoe, 2001; Hardy and Selkoe, 2002; Cleary et al., 2005). The pathology of AD is also associated with increased oxidative stress (Butterfield et al., 1999; Watson et al., 2005; Chauhan and Chauhan, 2006; Glabe and Kayed, 2006), which has been regarded as an important factor contributing to the impaired brain metabolism and mitochondrial dysfunction in AD (Gibson et al., 1998; Blass, 2003; Zhu et al., 2004; Bubber et al., 2005; Caspersen et al., 2005). Recent studies have provided strong evidence for a link between cytotoxicity of Aβ peptides and increase in oxidative stress (Yatin et al., 1999; Christen, 2000; Casley et al., 2002; Canevari et al., 2004; Moreira et al., 2005; Reddy, 2006). Oligomeric Aβ is known to exert specific effects on mitochondria in astrocytes and neurons, including a direct interaction of the peptide with mitochondrial enzymes (Kaneko et al., 1995; Lustbader et al., 2004; Takuma et al., 2005), its ability to disrupt the mitochondrial membrane structure (Rodrigues et al., 2001), and induction of oxidative stress (Abramov et al., 2004). However, the underlying mechanism(s) of these Aβ-induced alterations is still not fully understood.

There is evidence that Aβ can trigger cellular pathways and activate signaling molecules, including phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (Kriem et al., 2005). PLA2 belongs to a family of enzymes responsible for hydrolysis of the sn-2 position of membrane phospholipids. Recent studies on these PLA2s have focused on three groups, namely, the group IV Ca2+-dependent cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2), the group VI Ca2+-independent PLA2 (iPLA2), and the group II secretory PLA2 (sPLA2). PLA2s are not only important for maintenance of cell membrane phospholipids but are also involved in the complex network of signaling pathways that link receptor agonists to different types of cellular functions (Murakami and Kudo, 2002). Because of their important role in maintaining the structure of subcellular membranes, different groups of PLA2s have been implicated in the pathogenesis of many neurodegenerative diseases, including AD (Stephenson et al., 1999; Colangelo et al., 2002; Sun et al., 2004; Lukiw et al., 2005). Although cPLA2 has been implicated in neuronal apoptosis mediated by Aβ (Kriem et al., 2005), the possible role of PLA2 in Aβ-mediated alterations in mitochondrial function in astrocytes has not been investigated. In fact, different forms of PLA2s are stimulated by G-protein-coupled receptor agonists (e.g., cPLA2), oxidant compounds (e.g., cPLA2 and iPLA2), and proinflammatory agents (e.g., sPLA2) (Xu et al., 2002, 2003). In this study, we present evidence for oligomeric Aβ1–42 to enhance cPLA2 phosphorylation through mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) and NADPH oxidase and for the involvement of cPLA2 and iPLA2 in mitochondrial dysfunction and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in rat primary astrocytes.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture.

Primary cortical astrocytes from newborn rat brains were obtained using a standard stratification/cell-shaking procedure (McCarthy and de Vellis, 1980). This procedure yielded confluent mixed glial cultures within 7–9 d, after which the flasks were shaken at 180 rpm at room temperature for 3 h to remove microglial cells. These astrocytes (>95% as quantified by anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein labeling) were subsequently subcultured onto coverslips coated with poly-d-lysine (0.4 mg/ml) and fed every 48 h with fresh DMEM culture medium and 10% FBS as described previously (Zhu et al., 2005). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator.

Preparation of oligomeric Aβ1–42.

Aβ1–42 was obtained from American Peptide (Sunnyvale, CA), and its oligomeric form was prepared according to the protocol described previously (Dahlgren et al., 2002). Briefly, the peptide (1 mg) in powder form was dissolved in 200 μl of hexafluoro-2-propanol, and the solution was aliquoted into Eppendorf (Hamburg, Germany) tubes. Organic solvent was removed using a speed vacuum apparatus. The Aβ film left in the tube was resuspended in DMSO and further diluted in Ham's F-12 medium to make a 100 μm solution. The solution was incubated at 4°C for 24 h before use. Aβ42–1 (American Peptide) was processed and used as a control. Electrophoretic analysis of Aβ1–42 indicated a similar profile with oligomers in the preparation as described by Dahlgren et al. (2002).

Mitochondrial potential measurement.

For experiments to measure changes in mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm), astrocytes were grown on glass coverslips to ∼60% confluence. Rhodamine 123 (Rh 123) (10 μm; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was incubated with astrocytes for 10 min at 37°C, followed by washing cells three times with warm PBS to remove excess Rh 123 (Abramov et al., 2004). Accumulation of Rh 123 in polarized mitochondria quenches the fluorescent intensity. Therefore, an increase in Rh 123 fluorescence indicates mitochondrial depolarization (Duchen and Biscoe, 1992). Fluorescence measurements were obtained at 0.5 min intervals for 30 min using a Nikon (Tokyo, Japan) TE2000-U inverted microscope with a 40×, numerical aperture 0.95 objective lens. To verify that cells still functionally respond to pharmacological alteration of Δψm and to ensure that the increased Rh 123 fluorescence values are not a result of Rh 123 release from the mitochondria through depolarization, we applied the protonophore carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxy-phenylhydrazone (FCCP) (0.5 μm) at the end of each experiment (30 min) to further depolarize the mitochondria. In the data analysis, we normalized the data to a baseline set at one for the initial Rh 123 intensity at t = 0 for quantitative comparisons.

Mitochondrial ROS measurement.

For the measurement of ROS generated from mitochondria, astrocytes were incubated with MitoSox Red (5 μm; Invitrogen) for 10 min at 37°C, followed by washing three times with warm PBS. MitoSox Red is a cell-permeable dye that targets mitochondria in non-oxidized form because of its triphenylphosphine moiety and is selectively oxidized by O2·− but not by other ROS or reactive nitrogen species, resulting in a bright red fluorescence (Ooe et al., 2005). Fluorescence measurements were obtained at intervals of 2 min for 60 min.

Measurement of arachidonic acid release from astrocytes.

Arachidonic acid (AA) release was used to assess PLA2 activity in cell membranes (Xu et al., 2002). Briefly, astrocytes in DMEM containing 0.5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (DMEM–BSA) were incubated with 0.1 μCi of [14C]AA (specific activity, 50 Ci/mol; NEN, Boston, MA) per 35 mm dish for 4 h. This incubation period resulted in incorporation of >80% of labeled AA into phospholipids (Xue et al., 1999). Excess unincorporated labeled AA was removed by washing the cells three times with DMEM–BSA. Cells were then stimulated with Aβ1–42 or phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) for 30 min at 37°C. The radioactivity was measured in both cells and culture medium using a Beckman Instruments (Fullerton, CA) LS5800 liquid scintillation counter. The sum of radioactivity in the medium and the cells was defined as total incorporation of radioactivity, and the amount of labeled AA released into the medium was expressed as a percentage of the total after subtracting background activity.

Western blot analysis.

Astrocytes were cultured in 60 mm dishes until 90% confluent. After treatment (e.g., oligomeric Aβ1–42, apocynin, extracellular signal-regulated kinase [ERK] inhibitor, U0126 [1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis(o-aminophenylmercapto)butadiene], and the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 [4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-methylsulfinylphenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl)-1H-imidazole]), cells were washed with ice-cold PBS twice, followed by adding 200 μl of cell lysate medium (62.5 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% w/v SDS, 10% glycerol, and 50 mm dithiothreitol). After collecting the cell lysate, protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay. Equivalent amounts (e.g., 40 μg) of protein for each sample were resolved in 8% SDS-PAGE in duplicates. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were incubated in Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.4, with 0.5% Tween 20 (TBS-T) containing 5% nonfat milk 1 h at room temperature. The blots were reacted with rabbit phosphorylated cPLA2 (p-cPLA2) (Ser505) or cPLA2 (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) antibodies at 4°C overnight. After washing with TBS-T, they were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG–HRP (1:2000; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 1 h at room temperature. The blots were washed three times with TBS-T, and bands were visualized using SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent detection reagents from Pierce (Rockford, IL)

Small interfering RNA.

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) directed against the rat cPLA2 mRNA sequence (PLA2G4A; GenBank accession number NM_133551) were synthesized by Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). Four Smart-selected siRNA duplexes were provided in a single pool. Lamin A/C and nonspecific siRNA duplexes were also purchased from Dharmacon. Lamin A/C siRNA duplex (D-001050-01) were used as a positive control for transfection. Nonspecific siRNA duplexes (D-001210-02) were used as a negative control. siRNA was transfected in primary astrocytes using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the protocol of the manufacturer. Briefly, siRNA duplexes were diluted in OPTI-MEM I (Invitrogen) and were incubated with the cells at 37°C. After incubation for 6 h, growth medium was replaced with fresh medium. Cells were assayed for the silencing of the targeted protein after 48 h by Western blot analysis, and the function of the enzyme was assayed by the measurement of AA release as described above.

Fluorescence microscopy.

After treatment with Aβ or inhibitors, mitochondria in live cells were fluorescently labeled with MitoTracker Red CMXRos (250 nm; Invitrogen) in warm DMEM with 10% FBS at 37°C for 30 min. After washing with fresh DMEM three times, cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde in DMEM at 37°C for 30 min and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min. PBS containing 5% BSA was applied to the cells for 1 h to block nonspecific binding. To label p-cPLA2 or cytochrome c in the cells, rabbit polyclonal anti-p-cPLA2 (1:500; Cell Signaling Technology) or mouse monoclonal anti-cytochrome c (1:200; MitoSciences, Eugene, OR) in PBS with 1% BSA was added and incubated at 4°C overnight. This was followed by fluorescent labeling with a secondary antibody (1:1000; Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG for p-cPLA2 and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG for cytochrome c; Invitrogen) at room temperature for 1 h. Secondary antibodies did not show immunostaining in the absence of the primary antibody (data not shown).

Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy was performed with a Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) Radiance 2000 system (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) coupled with an Olympus (Tokyo, Japan) IX70 inverted microscope. Confocal images were acquired with a 60×, numerical aperture 1.2 water immersion objective lens for colocalization studies of cell components. Background subtraction was done for all images before analysis. The colocalized images were obtained by suppressing all colors, except yellow, in superimposed images using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). The colocalization index between two channels was quantified by normalizing the coincident intensity to the total intensity of the corresponding channel.

Determination of cytochrome c in mitochondria and cytosol by ELISA.

After treating astrocytes with Aβ for different times up to 4 h, cells were harvested with 0.05% trypsin, and the cytosol and mitochondrial fractions were obtained using a mitochondria isolation kit (Pierce) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Cytochrome c concentrations in the cytosol and mitochondria fractions were determined using an ELISA kit (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) following the procedure recommended by the manufacturer.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. Comparisons between groups were made with one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's post hoc tests. Comparison between two groups was made with paired t test. Values of p < 0.05 are considered statistically significant.

Results

Oligomeric Aβ1–42 activated cPLA2 and induced the release of AA from astrocytes

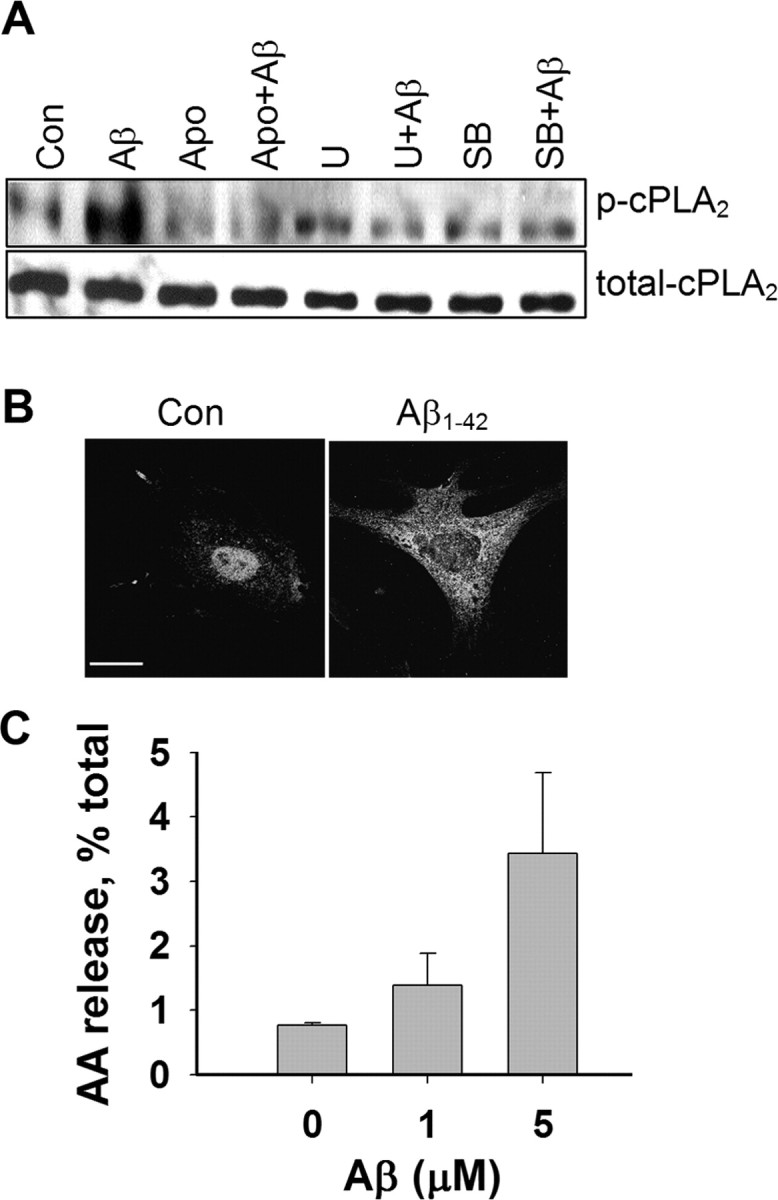

Activation of cPLA2 is characterized by its phosphorylation and translocation from cytosol to membranes (Leslie, 1997; Murakami and Kudo, 2002). In this study, Western blots using antibodies against p-cPLA2 (Ser505) were used to determine whether Aβ1–42 oligomers induce cPLA2 phosphorylation through the NADPH oxidase and MAPK pathways. As shown in Figure 1A, astrocytes treated with oligomeric Aβ1–42 for 30 min resulted in an increase in p-cPLA2. This treatment condition, however, did not cause lactate dehydrogenase release (data not shown). Because MAPK pathways have been reported to induce the phosphorylation of cPLA2 in astrocytes (Xu et al., 2002), we tested whether Aβ-mediated increase in p-cPLA2 can be inhibited by specific MAPK inhibitors, e.g., U0126 (5 μm) for extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and SB203580 (5 μm) for p38 MAPK. Results in Figure 1A show that both U0126 and SB203580 suppressed Aβ-induced p-cPLA2, whereas inhibitors alone did not alter p-cPLA2 in astrocytes. Because NADPH oxidase can serve as a source of ROS (Abramov et al., 2004) that activate MAPKs (Zhu et al., 2005), we also tested whether Aβ1–42 stimulates NADPH oxidase activation to produce ROS, resulting in phosphorylation of cPLA2 involving the MAPK pathways. For testing the role of NADPH oxidase, we used apocynin, a specific inhibitor known to inhibit the translocation of p47phox subunit of NADPH oxidase to the plasma membrane subunit (Barbieri et al., 2004). Results in Figure 1A show that apocynin (1 mm) completely inhibited Aβ-induced p-cPLA2, whereas apocynin alone did not alter basal levels of p-cPLA2 in the cells.

Figure 1.

Aβ increased the phosphorylation of cPLA2 and AA release. A, Western blot analysis shows an increase in p-cPLA2 but not cPLA2 in astrocytes after treatment with Aβ1–42 (5 μm) for 30 min. After immunohistochemical development with p-cPLA2 antibody, the membrane was stripped and reblotted with antibody for total cPLA2. For testing effects of inhibitors, astrocytes were treated with the ERK inhibitor U0126 (5 μm), the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (5 μm), and the NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin (1 mm) for 30 min before exposure to Aβ1–42 for 30 min. B, Confocal immunofluorescence images of p-cPLA2 in astrocytes before and after treatment with Aβ1–42 (5 μm) for 30 min. Scale bar, 15 μm. C, Aβ1–42 induced AA release in astrocytes.

Immunofluorescence microscopy was used to examine the reactivity of p-cPLA2 in astrocytes. As shown in Figure 1B, immunoreactivity of p-cPLA2 was found mainly around the nuclear region in control astrocytes but was increased in the cytoplasm after treatment with Aβ1–42 for 30 min. To show whether Aβ1–42-mediated increase in p-cPLA2 leads to functional activation of the enzyme, we also measured AA release. Results show that Aβ1–42 not only enhanced p-cPLA2 immunoreactivity but also induced an increase in AA release in astrocytes (Fig. 1C).

PLA2 mediated Aβ-induced mitochondrial depolarization

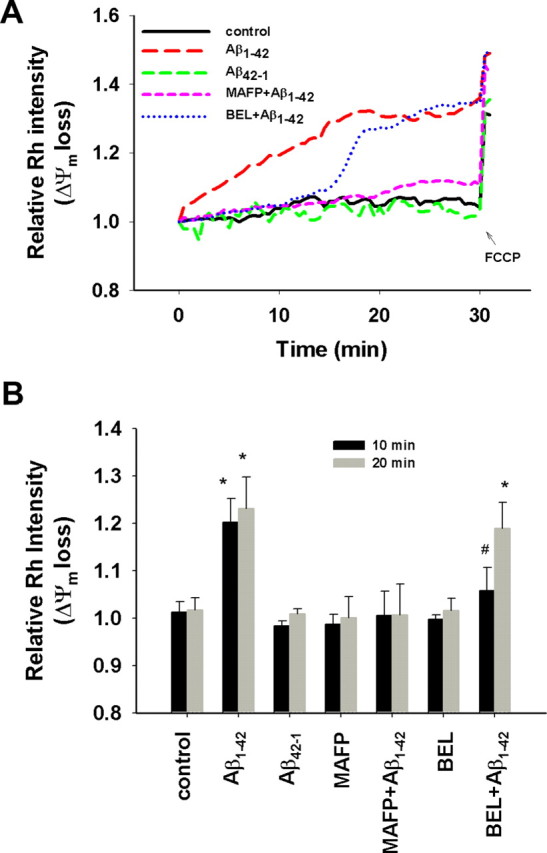

Mitochondrial depolarization was characterized by the loss of Δψm. To demonstrate the role of PLA2 in Aβ1–42-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, we applied quantitative fluorescence microscopy of Rh 123 to monitor the Δψm loss in astrocytes. Because Rh 123 in polarized mitochondria is quenched, an increase in the fluorescent intensity of Rh 123 on the loss of Δψm indicates mitochondrial depolarization (Duchen and Biscoe, 1992). Our data show that Aβ1–42 caused a significant loss of Δψm in astrocytes compared with control and with cells treated with Aβ42–1, an inactive Aβ with reversed peptide sequence (Fig. 2A). To test possible involvement of PLA2 on the Αβ-induced loss of Δψm, we used methylarachidonyl fluorophosphate (MAFP), a selective, active-site-directed irreversible inhibitor known to inhibit cPLA2 at low concentrations but both cPLA2 and iPLA2 at high concentrations (Balsinde et al., 1999). As shown in Figure 2A, MAFP (5 μm) completely suppressed the Δψm loss induced by Aβ1–42, suggesting that PLA2 activation is required for Aβ1–42 to induce Δψm loss in mitochondria in astrocytes. Bromoenol lactone (BEL), a selective, irreversible, mechanism-based inhibitor specific for iPLA2, was applied to test the involvement of iPLA2. BEL was able to suppress Aβ1–42-induced Δψm loss during the first 12–15 min (Fig. 2A). The lag time of the Δψm loss induced by Aβ1–42 in BEL-treated astrocytes suggests that iPLA2 is involved in the initial Δψm loss. Because BEL is a specific inhibitor for iPLA2 but not for cPLA2, the Δψm loss after the lag time also suggests that the activation of cPLA2 needed 12–15 min to take effect for inducing Δψm loss. Neither MAFP nor BEL treatment alone caused any effects on Δψm (data not shown). For positive controls, cells were treated with FCCP, a mitochondrial depolarization agent, at the end of each experiment to ensure that mitochondria in astrocytes remain functionally viable during the course of each experiment (Fig. 2A). Figure 2B is a histogram summarizing the relative Rh 123 intensities for all treatment groups measured at 10 and 20 min as two representative time points to distinguish the effects of MAFP and BEL. Results show the ability of MAFP to inhibit Aβ-induced Δψm loss at both 10 and 20 min, whereas inhibition of iPLA2 alone by BEL occurred only during the initial 10 min.

Figure 2.

Aβ1–42 induced mitochondrial Δψm loss. Astrocytes were pretreated with MAFP (5 μm) or BEL (5 μm) for 30 min before exposure to Aβ1–42 (5 μm) or Aβ42–1 (5 μm) at t = 0. Rh 123 intensity was measured at every 30 s interval for 30 min, and then FCCP (0.5 μm) was added at the end of 30 min. A, Δψm loss in astrocytes attributable to Aβ1–42 but not Aβ42–1 was suppressed by MAFP, a specific inhibitor of both cPLA2 and iPLA2, whereas BEL, a specific inhibitor of iPLA2, only suppressed the Δψm loss for the initial ∼12 min. B, Quantitative relative Rh 123 intensities at the two representative time points 10 and 20 min. Aβ1–42 caused significant Δψm loss compared with control (*p < 0.02), whereas Aβ42–1, MAFP, or BEL alone had no effect on Δψm. MAFP completely suppressed the Δψm loss induced by Aβ1–42, whereas BEL only suppressed the Δψm loss at the initial 10 min after exposure to Aβ1–42 (#p > 0.05). Values are mean ± SD obtained from four independent experiments.

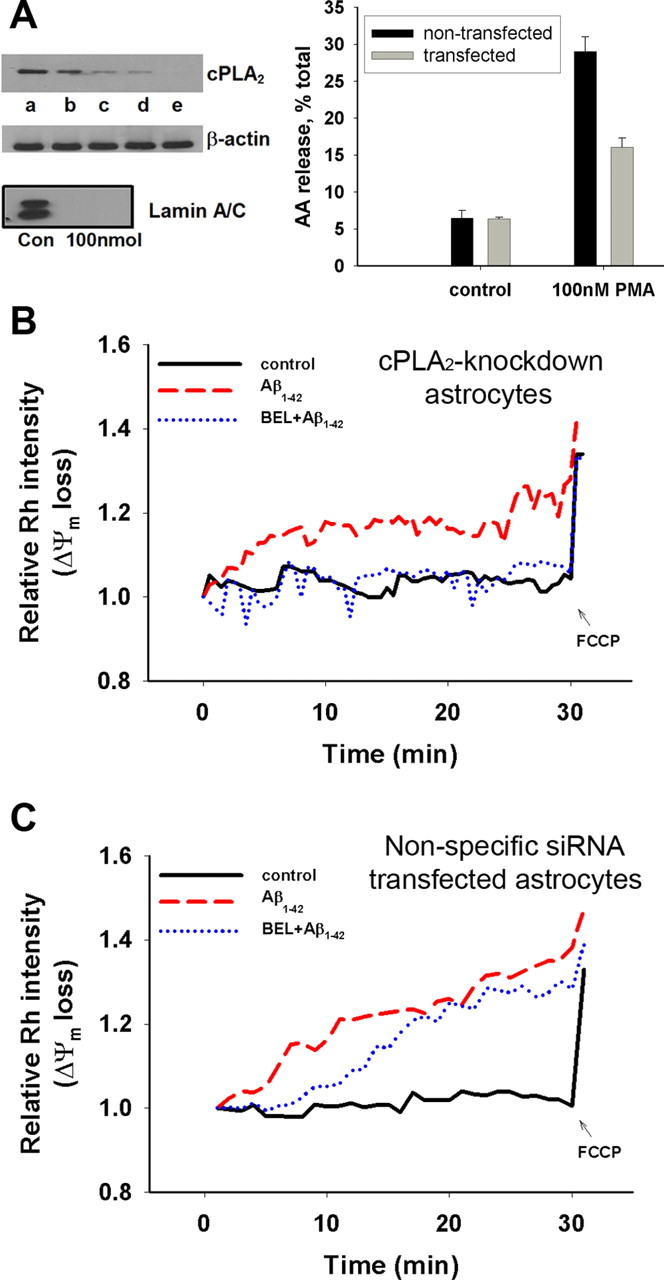

To further explore the involvement of cPLA2 in Aβ1–42-induced Δψm loss, we applied siRNA to silence cPLA2 in astrocytes. Western blot analysis showed a concentration-dependent decrease in cPLA2 in astrocytes after transfection with the siRNA duplexes compared with the nontransfected and the mock-transfected controls (Fig. 3A, left). Depletion of cPLA2 using the siRNA protocol inhibited the ability of astrocytes to respond to PMA, a PKC agonist known to stimulate cPLA2 and induce AA release (Xu et al., 2002) (Fig. 3A, right).

Figure 3.

Mitochondrial Δψm loss measured by Rh 123 in cPLA2 knockdown astrocytes. A, Left, Western blot analysis showing the efficiency of siRNA to deplete cPLA2 in astrocytes: a, nontransfected control; b, mock-transfected cells; c, astrocytes transfected with 25 nmol of the siRNA duplexes; d, astrocytes transfected with 50 nmol of the siRNA duplexes; e, astrocytes transfected with 100 nmol of the siRNA duplexes. Lamin A/C siRNA was used as positive control for transfection efficiency (bottom). Western blot analysis shows a dose-dependent decrease in cPLA2 in astrocytes after silencing with siRNA (compared with β-actin, which was used as loading control). Right, Functional assay of cPLA2 in siRNA-transfected astrocytes by measuring AA release after stimulation with PMA. B, Depletion of cPLA2 with siRNA (50 nmol) partially counteracted the Δψm loss induced by Aβ1–42 (5 μm), and the addition of BEL (5 μm) significantly suppressed the Δψm loss. C, Aβ1–42 and BEL effects on astrocytes transfected with nonspecific siRNA duplexes (50 nmol). Data represent one typical trial from four independent experiments.

Because results in Figure 2 show that BEL inhibited Aβ-induced Δψm loss only for the initial 10 min after the addition of Aβ1–42 to astrocytes that contain cPLA2 and iPLA2, we tested the effect of BEL in cPLA2 knockdown astrocytes. As expected, treatment of cPLA2 knockdown astrocytes with BEL (5 μm) completely suppressed Aβ1–42-induced Δψm loss during the entire time course of the experiment (Fig. 3B). Conversely, when astrocytes were transfected with the nonspecific siRNA duplexes (50 nmol), inhibition of Aβ-induced Δψm loss by BEL showed a lag time (Fig. 3C) similar to that observed in control astrocytes in Figure 2A. These results suggest that both iPLA2 and cPLA2 are involved in mediating Aβ1–42-induced Δψm loss in astrocytes.

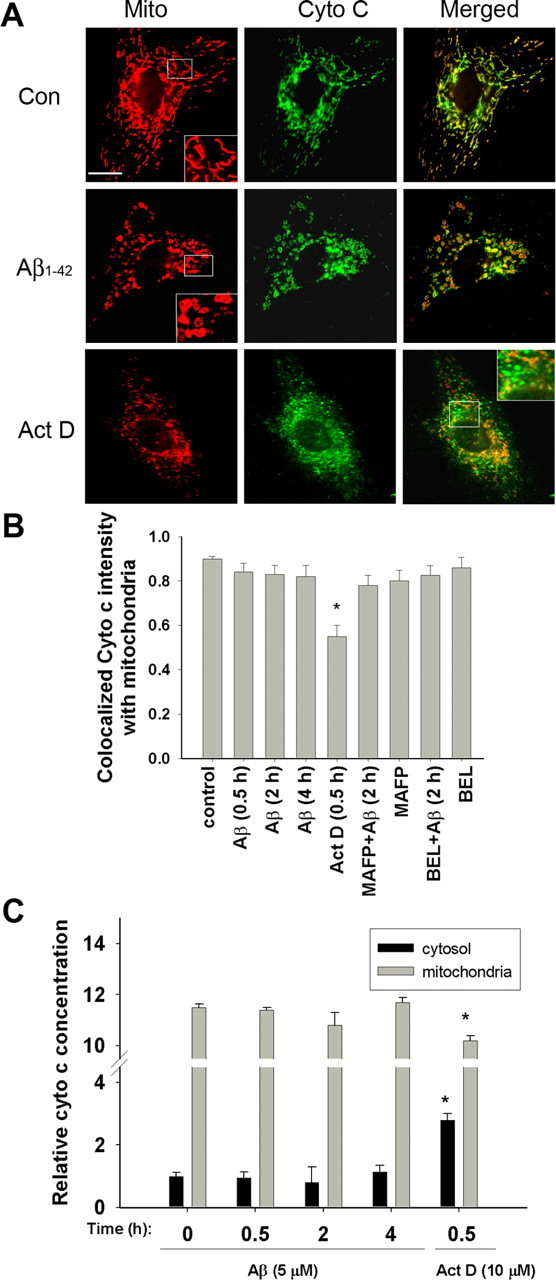

Oligomeric Aβ1–42 induced mitochondrial swelling but not cytochrome c release

Mitochondrial depolarization is usually associated with cytochrome c release, which subsequently initiates the mitochondrial-dependent apoptotic pathway. In this experiment, we used both ELISA and confocal immunofluorescence microscopy to examine cytochrome c release from mitochondria in astrocytes (Green and Reed, 1998; Krohn et al., 1999; Waterhouse et al., 2001). The presence of cytochrome c in mitochondria was confirmed by labeling cytochrome c with a specific antibody against cytochrome c and with MitoTracker Red CMXRos, which is specific for tracking mitochondria (Krohn et al., 1999). Figure 4A shows colocalization of mitochondria with cytochrome c in control astrocytes. Quantitative analysis showed that ∼90% of cytochrome c was colocalized with mitochondria at resting conditions and that this percentage remained unchanged even after Aβ1–42 treatment for up to 4 h (Fig. 4B). As a positive control, astrocytes treated with actinomycin D (10 μm) for 30 min showed diffuse labeling of cytochrome c in the cell cytoplasm, suggesting its release into the cytoplasm (Fig. 4A). Although Aβ1–42 did not induce significant mitochondrial cytochrome c release, it caused mitochondria to swell (Fig. 4A, insets). Interestingly, neither MAFP nor BEL suppressed mitochondrial swelling induced by Aβ1–42, suggesting that this morphological change is independent of PLA2 action (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Fluorescence confocal microscopy of cytochrome c and mitochondria in astrocytes. A, Astrocytes were treated without Aβ1–42 (5 μm) for 0.5, 2, and 4 h before immunostaining and confocal microscopy for cytochrome c and MitoTracker Red CMXRos. Actinomycin D (10 μm) was added to astrocytes for 30 min and used as a positive control. Inset, A magnified image to depict mitochondrial morphology. Aβ1–42 did not induce mitochondrial cytochrome c release for up to 4 h. As a positive control, mitochondrial cytochrome c release was induced by treating cells with actinomycin D. Scale bar, 15 μm. B, Quantitative analysis of merged images to depict colocalization between cytochrome c and mitochondria. Data obtained from confocal images showed that ∼90% of the cytochrome c was colocalized with mitochondria in controls. Aβ1–42 did not alter the colocalization of cytochrome c with mitochondria, indicating that cytochrome c was not released. However, treatment of astrocytes with actinomycin D caused significant (*p < 0.01) release of cytochrome c from mitochondria. Values are mean ± SD obtained from at least 36 cells from three independent experiments. C, Cytochrome c release as determined by the ELISA protocol.

To confirm that Aβ treatment does not elicit cytochrome c release from mitochondria in astrocytes, the amounts of cytochrome c in the cytosol and mitochondria were determined by ELISA and were normalized to that of an untreated control at the zero time point (Fig. 4C). Consistent with the results from confocal immunofluorescence microscopy, no obvious increase in cytochrome c was observed in the cytosol after treating astrocytes with Aβ1–42 for up to 4 h. As expected, astrocytes responded to actinomycin D, a compound known to uncouple the mitochondria respiratory chain, and released a large amount of cytochrome c into the cytosol (Fig. 4C).

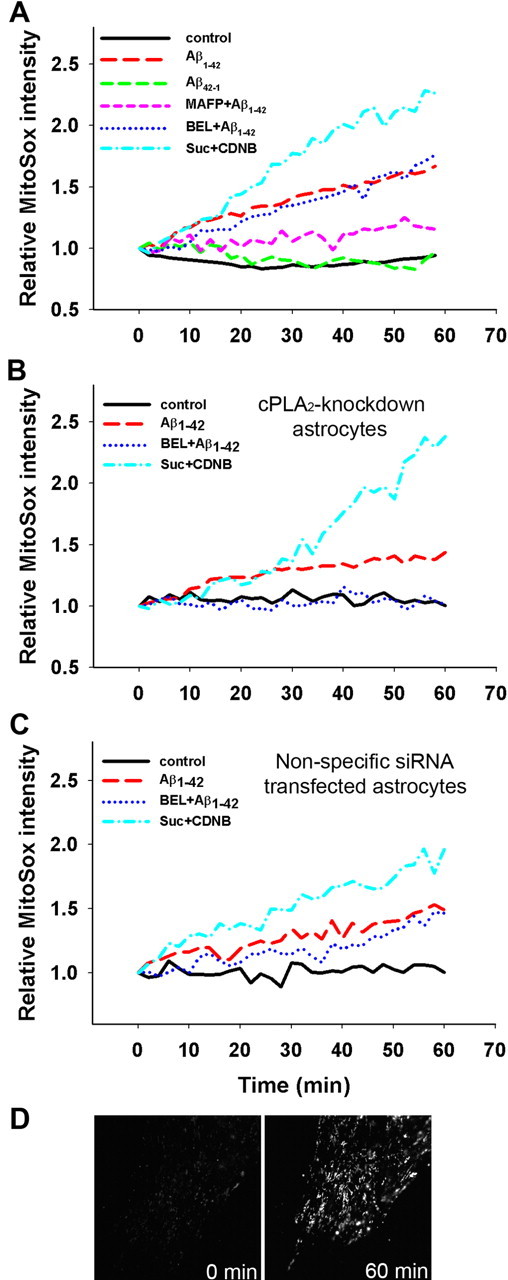

Role of PLA2 in Aβ1–42-induced mitochondrial ROS generation

Because mitochondria are considered as a principle site for ROS generation, we tested whether Aβ1–42-induced Δψm loss results in the generation of ROS from mitochondria. In this study, a highly specific mitochondrial superoxide indicator, MitoSox, was used to detect ROS production from mitochondria (Ooe et al., 2005). As shown in Figure 5A, astrocytes treated with Aβ1–42 resulted in an increase in mitochondrial ROS production compared with controls without Aβ1–42 treatment or with Aβ42–1 treatment. Furthermore, Aβ1–42-mediated increase in mitochondrial ROS production was suppressed by MAFP, whereas BEL suppressed mitochondrial ROS production only for the initial ∼10 min. MAFP and BEL alone did not promote mitochondrial ROS production (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Mitochondrial ROS production measured by MitoSox. Astrocytes were pretreated with MAFP (5 μm), or BEL (5 μm) for 30 min and then exposed to Aβ1–42 (5 μm) or Aβ42–1 (5 μm). Mitochondrial ROS production was assessed by measuring fluorescent intensity of MitoSox at 2 min intervals for 60 min. A, ROS production in control astrocytes. Aβ1–42, but not Aβ42–1, caused significant mitochondrial ROS production in astrocytes, and MAFP significantly suppressed Aβ1–42-induced ROS production. Data also show that BEL suppressed Aβ1–42-induced ROS production for the initial 10 min after addition of Aβ1–42. B, ROS production in cPLA2 knockdown astrocytes by siRNA. Addition of BEL completely suppressed Aβ1–42-induced ROS production. Data represent one typical trial from three independent experiments. C, ROS production in astrocytes transfected with nonspecific siRNA. The results were consistent with those observed using control astrocytes. D, Fluorescent micrographs of MitoSox in astrocytes. Fluorescent images were taken at 0 min (left) and 60 min (right) after Aβ1–42 (5 μm) treatment.

The effect of BEL on Aβ1–42-induced mitochondrial ROS production was further examined in astrocytes transfected with siRNA to downregulate cPLA2. As shown in Figure 5B, BEL completely inhibited mitochondrial ROS production in cPLA2 knockdown astrocytes. These results further lend support that mitochondrial ROS generation in astrocytes is mediated by both cPLA2 and iPLA2. As a positive control, astrocytes treated with succinate and 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene to enhance respiratory activity (Liu et al., 2002) resulted in a time-dependent increase in mitochondrial ROS production (Fig. 5A–C).

To demonstrate the specificity of mitochondrial superoxide detection by MitoSox, fluorescent images of MitoSox in astrocytes were compared with astrocytes labeled with MitoTracker Red CMXRos. Consistent with the property of MitoSox to target mitochondria, fluorescent images of MitoSox in astrocytes (Fig. 5D) exhibited a fluorescent pattern similar to the fluorescent images of mitochondria labeled with MitoTracker Red CMXRos in astrocytes (Fig. 4), whereas other probes for superoxide detection, such as dihydroethidium and 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, appeared to be more diffuse (data not shown).

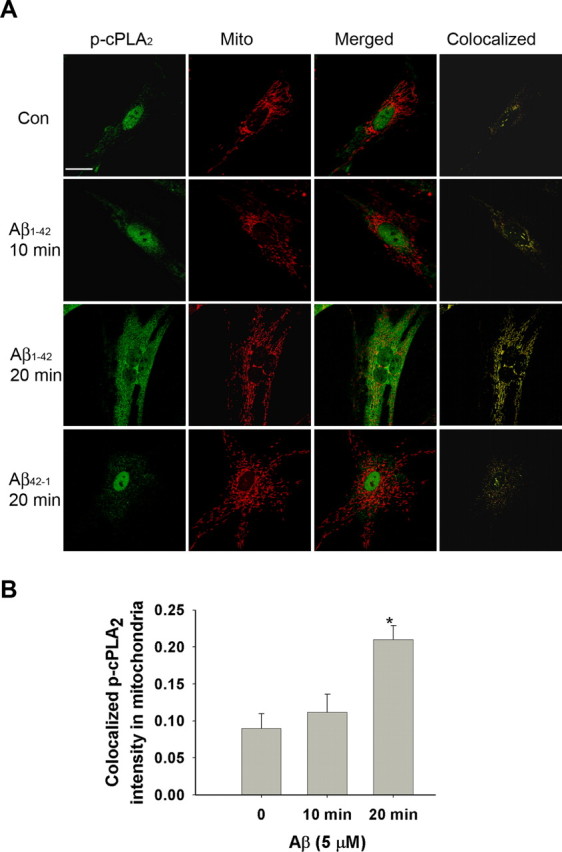

Oligomeric Aβ1–42 increased the colocalization between cPLA2 and mitochondria

To address the lag time for the action of cPLA2 on mitochondria, confocal immunofluorescent microscopy was used to study the colocalization between p-cPLA2 and mitochondria fluorescently labeled with MitoTracker. Analysis of colocalization between p-cPLA2 and mitochondria showed an obvious increase in colocalization at the 20 min but not the 10 min time point after Aβ1–42 treatment (Fig. 6A,B). The reverse Aβ peptide Aβ42–1 did not exert any effects on the colocalization.

Figure 6.

Colocalization between p-cPLA2 and mitochondria. A, A large increase in p-cPLA2 was found in the cytoplasm after treatment with Aβ1–42 for 20 min, indicating that Aβ1–42 increased phosphorylation of cPLA2. Scale bar, 15 μm. B, Quantitative analysis of colocalization between mitochondria and p-cPLA2. Data from confocal images showed that ∼10% of the p-cPLA2 was initially localized in mitochondria and remained unchanged for at least 10 min after Aβ1–42 treatment. After treatment with Aβ1–42 for 20 min, the amount of p-cPLA2 colocalized with mitochondria increased at least twofold (*p < 0.01). Values are mean ± SD obtained from at least 40 cells from three independent experiments.

Discussion

In this study, we provided evidence showing that two different groups of PLA2, namely iPLA2 and cPLA2, play a pivotal role in oligomeric Aβ1–42-induced Δψm loss and mitochondrial ROS production in astrocytes. Whereas iPLA2 exhibits an immediate action after the addition of Aβ1–42 to cells, the action of cPLA2 requires a lag time of ∼12 min to induce Δψm loss and mitochondrial ROS production. The lag time appears to reflect a relatively slower process for the phosphorylation and translocation of cPLA2 to mitochondria. Our previous study identified the role of iPLA2 and cPLA2 in oxidant damage of astrocytes, and the effects of oxidants on cPLA2 are mediated through activation of the MAPK pathways (Xu et al., 2003). Aβ has been shown to stimulate glial cells and cause neuronal death (Butterfield, 2002; Dahlgren et al., 2002; Craft et al., 2006). Abramov et al. (2004) attributed the ability of Aβ to cause ROS production in astrocytes through activation of NADPH oxidase, and, in turn, this leads to depolarization of mitochondria (Abramov et al., 2004). In this study, we demonstrated a unique mechanism that Aβ triggers the MAPK pathways involving NADPH oxidase to activate cPLA2; in turn, activated cPLA2 targets mitochondria to cause loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and promote ROS production in astrocytes (supplemental Fig. 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material).

The Ca2+-independent iPLA2 is abundant in astrocytes and has been found to be associated with mitochondria and oxidative stress (Madesh and Balasubramanian, 1997; Adibhatla et al., 2003; Gadd et al., 2006). However, the mechanism underlying the action of iPLA2 in mitochondrial dysfunction remains to be investigated further. It has been proposed that tBID (BH3 interacting domain death agonist) plus BAX (Bcl2-associated X protein) activate ROS generation, which subsequently augments iPLA2 activity, leading to translocation of certain mitochondrial proteins from the inner membrane to the outer membrane space (Brustovetsky et al., 2005). Activation of iPLA2 in isolated rat liver mitochondria has been suggested to promote opening of the permeability transition pore (PTP), rupture of the outer mitochondrial membrane, and spontaneous release of cytochrome c (Gadd et al., 2006). However, because opening of the PTP (Green and Kroemer, 1998; Green and Reed, 1998; von Ahsen et al., 2000) typically accommodates transport of small molecules <1.5 kDa, the opening of a PTP may not be sufficient for the release of large molecules, such as cytochrome c (molecular weight of ∼15 kDa). In fact, some studies have shown that cytochrome c release and caspase activation can occur before any detectable Δψm loss (Bossy-Wetzel et al., 1998; Green and Reed, 1998). In addition, although Aβ was found to induce mitochondrial swelling in astrocytes, it did not induce cytochrome c release, and mitochondrial swelling induced by Aβ1–42 was not associated with PLA2 activation.

Mitochondrial dysfunction coupled with impaired ATP production appears to be a hallmark of Aβ-induced toxicity in AD (Zhu et al., 2004). Complex mechanisms are known to regulate mitochondrial functions, leading to decline in ATP production, increase in ROS production, and apoptotic pathways (Keil et al., 2004). Our study provided new insights for Aβ to activate cPLA2 through NADPH oxidase and MAPKs, which, in turn, leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and additional ROS production in astrocytes through cPLA2 and iPLA2 (supplemental Fig. 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material).

Based on our data as well as those from Abramov et al. (2004), it is reasonable to propose two major mechanisms for Aβ to mediate ROS production, initially from NADPH oxidase and subsequently from mitochondria. Although both processes involve PLA2, detailed mechanisms remain to be elucidated. PLA2s hydrolyze membrane phospholipids and produce free fatty acids and lysophospholipids. Free fatty acids are recognized to be classical uncouplers of mitochondrial respiratory chain (Di Paola and Lorusso, 2006; Hirabara et al., 2006), and lysophospholipids possess detergent properties. AA released by PLA2 has been shown to trigger a Ca2+-dependent apoptotic pathway by opening the mitochondrial PTP (Penzo et al., 2004). Obviously, the mechanisms for PLA2 in Aβ-mediated alteration of mitochondrial membrane function and the pathophysiology of AD warrant additional investigation. Understanding this signaling pathway may provide new avenues for a potential treatment strategy for combating the progression of AD.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the University of Missouri–Columbia Research Board (J.C-M.L.) and National Institutes of Health Grant 1P01 AG18357 (G.Y.S.). We thank Dr. A. Simonyi for helpful discussions.

References

- Abramov AY, Canevari L, Duchen MR. β-Amyloid peptides induce mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in astrocytes and death of neurons through activation of NADPH oxidase. J Neurosci. 2004;24:565–575. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4042-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF, Dempsey RJ. Phospholipase A2, hydroxyl radicals, and lipid peroxidation in transient cerebral ischemia. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2003;5:647–654. doi: 10.1089/152308603770310329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsinde J, Balboa MA, Insel PA, Dennis EA. Regulation and inhibition of phospholipase A2. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1999;39:175–189. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri SS, Cavalca V, Eligini S, Brambilla M, Caiani A, Tremoli E, Colli S. Apocynin prevents cyclooxygenase 2 expression in human monocytes through NADPH oxidase and glutathione redox-dependent mechanisms. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blass JP. Cerebrometabolic abnormalities in Alzheimer's disease. Neurol Res. 2003;25:556–566. doi: 10.1179/016164103101201995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossy-Wetzel E, Newmeyer DD, Green DR. Mitochondrial cytochrome c release in apoptosis occurs upstream of DEVD-specific caspase activation and independently of mitochondrial transmembrane depolarization. EMBO J. 1998;17:37–49. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brustovetsky T, Antonsson B, Jemmerson R, Dubinsky JM, Brustovetsky N. Activation of calcium-independent phospholipase A (iPLA) in brain mitochondria and release of apoptogenic factors by BAX and truncated BID. J Neurochem. 2005;94:980–994. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubber P, Haroutunian V, Fisch G, Blass JP, Gibson GE. Mitochondrial abnormalities in Alzheimer brain: mechanistic implications. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:695–703. doi: 10.1002/ana.20474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield DA. Amyloid β-peptide (1–42)-induced oxidative stress and neurotoxicity: implications for neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease brain. A review. Free Radic Res. 2002;36:1307–1313. doi: 10.1080/1071576021000049890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield DA, Howard B, Yatin S, Koppal T, Drake J, Hensley K, Aksenov M, Aksenova M, Subramaniam R, Varadarajan S, Harris-White ME, Pedigo NW, Jr, Carney JM. Elevated oxidative stress in models of normal brain aging and Alzheimer's disease. Life Sci. 1999;65:1883–1892. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canevari L, Abramov AY, Duchen MR. Toxicity of amyloid β peptide: tales of calcium, mitochondria, and oxidative stress. Neurochem Res. 2004;29:637–650. doi: 10.1023/b:nere.0000014834.06405.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casley CS, Canevari L, Land JM, Clark JB, Sharpe MA. β-amyloid inhibits integrated mitochondrial respiration and key enzyme activities. J Neurochem. 2002;80:91–100. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspersen C, Wang N, Yao J, Sosunov A, Chen X, Lustbader JW, Xu HW, Stern D, McKhann G, Yan SD. Mitochondrial Aβ: a potential focal point for neuronal metabolic dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. FASEB J. 2005;19:2040–2041. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3735fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan V, Chauhan A. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease. Pathophysiology. 2006;13:195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christen Y. Oxidative stress and Alzheimer disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:621S–629S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.2.621s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary JP, Walsh DM, Hofmeister JJ, Shankar GM, Kuskowski MA, Selkoe DJ, Ashe KH. Natural oligomers of the amyloid-β protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:79–84. doi: 10.1038/nn1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colangelo V, Schurr J, Ball MJ, Pelaez RP, Bazan NG, Lukiw WJ. Gene expression profiling of 12633 genes in Alzheimer hippocampal CA1: transcription and neurotrophic factor down-regulation and up-regulation of apoptotic and pro-inflammatory signaling. J Neurosci Res. 2002;70:462–473. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft JM, Watterson DM, Van Eldik LJ. Human amyloid β-induced neuroinflammation is an early event in neurodegeneration. Glia. 2006;53:484–490. doi: 10.1002/glia.20306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren KN, Manelli AM, Stine WB, Jr, Baker LK, Krafft GA, LaDu MJ. Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-β peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32046–32053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paola M, Lorusso M. Interaction of free fatty acids with mitochondria: coupling, uncoupling and permeability transition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:1330–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen MR, Biscoe TJ. Relative mitochondrial membrane potential and [Ca2+]i in type I cells isolated from the rabbit carotid body. J Physiol (Lond) 1992;450:33–61. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadd ME, Broekemeier KM, Crouser ED, Kumar J, Graff G, Pfeiffer DR. Mitochondrial iPLA2 activity modulates the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria and influences the permeability transition. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6931–6939. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510845200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson GE, Sheu KF, Blass JP. Abnormalities of mitochondrial enzymes in Alzheimer disease. J Neural Transm. 1998;105:855–870. doi: 10.1007/s007020050099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glabe CG, Kayed R. Common structure and toxic function of amyloid oligomers implies a common mechanism of pathogenesis. Neurology. 2006;66:S74–S78. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000192103.24796.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green D, Kroemer G. The central executioners of apoptosis: caspases or mitochondria? Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:267–271. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DR, Reed JC. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science. 1998;281:1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirabara SM, Silveira LR, Alberici LC, Leandro CV, Lambertucci RH, Polimeno GC, Cury Boaventura MF, Procopio J, Vercesi AE, Curi R. Acute effect of fatty acids on metabolism and mitochondrial coupling in skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko I, Yamada N, Sakuraba Y, Kamenosono M, Tutumi S. Suppression of mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase, a primary target of β-amyloid, and its derivative racemized at Ser residue. J Neurochem. 1995;65:2585–2593. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65062585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil U, Bonert A, Marques CA, Scherping I, Weyermann J, Strosznajder JB, Muller-Spahn F, Haass C, Czech C, Pradier L, Muller WE, Eckert A. Amyloid β-induced changes in nitric oxide production and mitochondrial activity lead to apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:50310–50320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405600200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriem B, Sponne I, Fifre A, Malaplate-Armand C, Lozac'h-Pillot K, Koziel V, Yen-Potin FT, Bihain B, Oster T, Olivier JL, Pillot T. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 mediates neuronal apoptosis induced by soluble oligomers of the amyloid-β peptide. FASEB J. 2005;19:85–87. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1807fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krohn AJ, Wahlbrink T, Prehn JH. Mitochondrial depolarization is not required for neuronal apoptosis. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7394–7404. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07394.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie CC. Properties and regulation of cytosolic phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16709–16712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.16709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Fiskum G, Schubert D. Generation of reactive oxygen species by the mitochondrial electron transport chain. J Neurochem. 2002;80:780–787. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2002.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukiw WJ, Cui JG, Marcheselli VL, Bodker M, Botkjaer A, Gotlinger K, Serhan CN, Bazan NG. A role for docosahexaenoic acid-derived neuroprotectin D1 in neural cell survival and Alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2774–2783. doi: 10.1172/JCI25420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustbader JW, Cirilli M, Lin C, Xu HW, Takuma K, Wang N, Caspersen C, Chen X, Pollak S, Chaney M, Trinchese F, Liu S, Gunn-Moore F, Lue LF, Walker DG, Kuppusamy P, Zewier ZL, Arancio O, Stern D, Yan SS, et al. ABAD directly links Aβ to mitochondrial toxicity in Alzheimer's disease. Science. 2004;304:448–452. doi: 10.1126/science.1091230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madesh M, Balasubramanian KA. Activation of liver mitochondrial phospholipase A2 by superoxide. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;346:187–192. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy KDA, de Vellis J. Preparation of separate astroglial and oligodendroglial cell cultures from rat cerebral tissue. J Cell Biol. 1980;85:890–902. doi: 10.1083/jcb.85.3.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira PI, Honda K, Liu Q, Santos MS, Oliveira CR, Aliev G, Nunomura A, Zhu X, Smith MA, Perry G. Oxidative stress: the old enemy in Alzheimer's disease pathophysiology. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2005;2:403–408. doi: 10.2174/156720505774330537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Kudo I. Phospholipase A2. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2002;131:285–292. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooe H, Taira T, Iguchi-Ariga SM, Ariga H. Induction of reactive oxygen species by bisphenol A and abrogation of bisphenol A-induced cell injury by DJ-1. Toxicol Sci. 2005;88:114–126. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzo D, Petronilli V, Angelin A, Cusan C, Colonna R, Scorrano L, Pagano F, Prato M, Di Lisa F, Bernardi P. Arachidonic acid released by phospholipase A2 activation triggers Ca2+-dependent apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25219–25225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310381200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy PH. Amyloid precursor protein-mediated free radicals and oxidative damage: implications for the development and progression of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 2006;96:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues CM, Sola S, Brito MA, Brondino CD, Brites D, Moura JJ. Amyloid β-peptide disrupts mitochondrial membrane lipid and protein structure: protective role of tauroursodeoxycholate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;281:468–474. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. Clearing the brain's amyloid cobwebs. Neuron. 2001;32:177–180. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00475-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson D, Rash K, Smalstig B, Roberts E, Johnstone E, Sharp J, Panetta J, Little S, Kramer R, Clemens J. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 is induced in reactive glia following different forms of neurodegeneration. Glia. 1999;27:110–128. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199908)27:2<110::aid-glia2>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun GY, Xu J, Jensen MD, Simonyi A. Phospholipase A2 in the central nervous system: implications for neurodegenerative diseases. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:205–213. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R300016-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takuma K, Yao J, Huang J, Xu H, Chen X, Luddy J, Trillat AC, Stern DM, Arancio O, Yan SS. ABAD enhances Aβ-induced cell stress via mitochondrial dysfunction. FASEB J. 2005;19:597–598. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2582fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Ahsen O, Renken C, Perkins G, Kluck RM, Bossy-Wetzel E, Newmeyer DD. Preservation of mitochondrial structure and function after Bid- or Bax-mediated cytochrome c release. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:1027–1036. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse NJ, Goldstein JC, von Ahsen O, Schuler M, Newmeyer DD, Green DR. Cytochrome c maintains mitochondrial transmembrane potential and ATP generation after outer mitochondrial membrane permeabilization during the apoptotic process. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:319–328. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.2.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Castano E, Kokjohn TA, Kuo YM, Lyubchenko Y, Pinsky D, Connolly ES, Jr, Esh C, Luehrs DC, Stine WB, Rowse LM, Emmerling MR, Roher AE. Physicochemical characteristics of soluble oligomeric Aβ and their pathologic role in Alzheimer's disease. Neurol Res. 2005;27:869–881. doi: 10.1179/016164105X49436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Weng YI, Simonyi A, Krugh BW, Liao Z, Weisman GA, Sun GY. Role of PKC and MAPK in cytosolic PLA2 phosphorylation and arachadonic acid release in primary murine astrocytes. J Neurochem. 2002;83:259–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Yu S, Sun AY, Sun GY. Oxidant-mediated AA release from astrocytes involves cPLA2 and iPLA2. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:1531–1543. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue D, Xu J, McGuire SO, Devitre D, Sun GY. Studies on the cytosolic phospholipase A2 in immortalized astrocytes (DITNC) revealed new properties of the calcium ionophore, A23187. Neurochem Res. 1999;24:1285–1291. doi: 10.1023/a:1020981224876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatin SM, Varadarajan S, Link CD, Butterfield DA. In vitro and in vivo oxidative stress associated with Alzheimer's amyloid β-peptide (1–42) Neurobiol Aging. 1999;20:325–330. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00056-1. 339–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu D, Tan KS, Zhang X, Sun AY, Sun GY, Lee JC. Hydrogen peroxide alters membrane and cytoskeleton properties and increases intercellular connections in astrocytes. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3695–3703. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Smith MA, Perry G, Aliev G. Mitochondrial failures in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2004;19:345–352. doi: 10.1177/153331750401900611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]