Abstract

Amyloid-β (Aβ) toxicity has been postulated to initiate synaptic loss and subsequent neuronal degeneration seen in Alzheimer's disease (AD). We previously demonstrated that the standardized Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761, commonly used to enhance memory and by AD patients for dementia, inhibits Aβ-induced apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells. In this study, we use EGb 761 and its single constituents to associate Aβ species with Aβ-induced pathological behaviors in a model organism, Caenorhabditis elegans. We report that EGb 761 and one of its components, ginkgolide A, alleviates Aβ-induced pathological behaviors, including paralysis, and reduces chemotaxis behavior and 5-HT hypersensitivity in a transgenic C. elegans. We also show that EGb 761 inhibits Aβ oligomerization and Aβ deposits in the worms. Moreover, reducing oxidative stress is not the mechanism by which EGb 761 and ginkgolide A suppress Aβ-induced paralysis because the antioxidant l-ascorbic acid reduced intracellular levels of hydrogen peroxide to the same extent as EGb 761, but was not nearly as effective in suppressing paralysis in the transgenic C. elegans. These findings suggest that (1) EGb 761 suppresses Aβ-related pathological behaviors, (2) the protection against Aβ toxicity by EGb 761 is mediated primarily by modulating Aβ oligomeric species, and (3) ginkgolide A has therapeutic potential for prevention and treatment of AD.

Keywords: Aβ peptide, Alzheimer's disease, behavior, mutant, phenotype, serotonin

Introduction

Despite a widely accepted “amyloid cascade hypothesis” for Alzheimer's disease (AD) (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002), the current explanation for amyloid-β (Aβ) toxicity in AD still remains controversial in view of the fact that the relationship between Aβ species and Aβ-specific behavior has not been defined in vivo (Lorenzo and Yankner, 1994; Pike et al., 1995; Lambert et al., 1998). A leading theory is that Aβ oligomers are responsible for initiation of synaptic dysfunction, an early event that leads to neurodegeneration observed in AD (Walsh and Selkoe, 2004; Roselli et al., 2005; Lesne et al., 2006; Oddo et al., 2006). The evidence for or against these hypotheses is critical for specific therapeutic strategies. It has previously been demonstrated that small molecules inhibiting Aβ oligomers also reduced its toxicity (Walsh et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2005; Maezawa et al., 2006). However, most of these studies were conducted in vitro, and the use of a transgenic mice model of AD for pharmacological evaluation and mechanistic studies is time-consuming. Simple invertebrate models of neurodegenerative diseases offer experimental advantages for addressing basic cellular processes that are conserved among all animals (Link, 2005; Wu and Luo, 2005).

The standard Gingko biloba leaf extract EGb 761 has been given routinely as a prescription drug in many countries, and as a dietary supplement in the United States, for Alzheimer's dementia (Christen and Maixent, 2002). Several clinical trials have provided evidence of efficacy (Le Bars et al., 1997; Birks et al., 2002; Mix and Crews, 2002; Le Bars, 2003), comparable with Donepezil (Mazza et al., 2006), as a symptomatic treatment of mild to moderate AD, and suggestive for AD prevention (Andrieu et al., 2003). Currently, a National Institutes of Health-supported GEM (Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory) study in the United States and a GuidAge study in Europe are underway to evaluate EGb 761 as a preventive drug (DeKosky et al., 2006). Substantial experimental data indicate that EGb 761 has neuroprotective and neuromodulatory effects (Luo, 2001; Watanabe et al., 2001; Yao et al., 2001; DeFeudis, 2002). Two of its major constituents, flavonoids (24%) and terpenoids (6%), have been actively investigated for their neuroprotective properties (DeFeudis, 1998; Smith and Luo, 2003). The ginkgolides, known as potent antagonists of platelet-activating factor receptor (PAFR) (Smith et al., 1996) are unique to the G. biloba tree (Nakanishi, 1967; Ivic et al., 2003; Jaracz et al., 2004). The flavonoids are involved in antioxidative properties of EGb 761.

We and others previously described an inhibitory effect of EGb 761 on Aβ oligomerization in solution (Luo et al., 2002; Chromy et al., 2003) providing evidence that EGb 761 can alter the biochemical and biophysical properties of Aβ that may underpin its toxicity. In the present study, we use the transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans model (Link, 1995) that exhibits several pathological behaviors to associate Aβ species with Aβ-induced abnormal behaviors in the organism. The current results support the hypothesis that Aβ oligomers are the toxic species and suggest that beneficial effects of EGb 761 on the cognitive function of AD patients is, at least in part, attributable to its modulation of Aβ oligomerization.

Materials and Methods

G. biloba extract EGb 761 was provided by Schwabe Pharmaceuticals (Karlsruhe, Germany); the extract is well characterized and is the one used in the ongoing clinic trials. The flavonoid fraction (Fig. 1 C) was from Ipsen (Paris France). The individual constituents of EGb 761 ginkgolide A (GA), ginkgolide B (GB), ginkgolide C (GC), ginkgolide J (GJ) (Fig. 1 A), and bilobalide (BB) (Fig. 1 B) were obtained from Dr. I. A. Khan at the National Center for Natural Products Research (Oxford, MS). Congo red (CR), l-ascorbic acid [vitamin C (VC)] as well as other chemicals were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Stock solutions of all chemicals were made either with 100% ethanol or with distilled water only. The final concentration of ethanol did not exceed 0.01% in the food (Escherichia coli strain OP50). All chemicals for treatment of experimental animals were added directly to the OP50 food source and the working concentration was equal to 100 μg/ml for EGb 761, or 10 μg/ml for single constituents of EGb 761.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of the ginkgolides (A), the bilobalide (B), and three flavonol glycosides (C). The ginkgolides and bilobalide are specific to the G. biloba tree. Ginkgolides A, B, C, J, and bilobalide, but not ginkgolide M, are constituents of EGb 761. The flavonol glycosides quercetin, kaempferol, and isorhamnetin are present in trace amounts in EGb 761 (DeFeudis, 1998).

C. elegans strains.

(For a summary, see Table 1.) The wild-type strain N2 (Bristol) was from Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN). The construction and characterization of the transgenic nematode strains CL2006 (unc-54/Aβ1–42) and CL4176 (smg-1ts [myo-3/Aβ1–42 long 3′-untranslated region (UTR)]) and its control strain CL1175 (smg-1ts) have been described previously (Link, 1995; Link et al., 2001). The CL2006 strain constitutively produces a body-wall muscle-specific Aβ1–42, whereas the expression of muscle-specific Aβ1–42 in CL4176 depends on upshifting temperature from 16 to 23°C. The transgenic arrays in the CL2006, CL1175, and CL4176 strains all contain the dominant rol-6(su1066) morphological marker. The CL2355 strain [smg-1ts (snb-1/Aβ1–42/long 3′-UTR)] employs the promoter of the C. elegans synaptobrevin ortholog (snb-1) to drive pan-neuronal expression of Aβ1–42, which is inducible by temperature upshift. The transgenic arrays in CL2355 and the control strain CL2122 are marked with a mtl-2/green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgene that causes constitutive intestinal GFP expression. An integrated myo-3/GFP/long 3′-UTR strain (CL2179) is used as a control for CL4176. This strain has a GFP reporter tagged to the same promoter as the transgenic strains and has detectable GFP at 16°C, which is significantly stronger at higher temperatures.

Table 1.

Description of the well characterized transgenic C. elegans used in the study

| Strains | Transgene | Expression | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | Wild type | Wt movement | |

| CL4176 | myo-3/Aβ1–42 | Inducible muscle Aβ1–42 | Rapid paralysis |

| CL1175 | myo-3 | Control for CL4176 | Normal |

| CL2006 | unc-54/Aβ1–42 | Constitutive muscle Aβ1–42 | Progressive paralysis |

| CL2355 | snb-1/Aβ1–42 | Inducible neuronal Aβ1–42 | Reduced chemotaxis |

| Hypersensitive to 5-HT | |||

| CL2122 | mtl-2/GFP | Control for CL2355 | Wt movement |

| CL2179 | myo-3/GFP | GFP control for CL4176 | Wt movement |

Wt, Wild type.

C. elegans maintenance and treatment.

The wild-type (N2) and the transgenic CL2006 were propagated at 20°C, CL4176 and CL2355 and their controls at 16°C, on solid nematode growth medium (NGM) seeded with 100 μl spots of E. coli (OP50) for food. To prepare age-synchronized animals, nematodes were transferred to fresh NGM plates on reaching reproductive maturity at 3 d of age and allowed to lay eggs for 4–6 h (overnight for Western blotting of CL4176 and CL2355). Isolated hatchlings from the synchronized eggs (day 1) were cultured on fresh NGM plates in either a 20°C or a 16°C (for CL4176, CL2355, and their control strains) temperature-controlled incubator (model 2005; Sheldon Manufacturing, Cornelius, OR). The worms were fed with the drugs either from stage L1 (1 d of age) or starting from the egg.

Paralysis assays.

The strain CL4176 (Drake et al., 2003; Link et al., 2003) maintained at 16°C was egg-synchronized onto the 35 × 10 mm culture plates containing either a vehicle or drug. Transgene expression was induced by upshifting the temperature from 16 to 23°C, started at the 36th hour after egg laying and lasted until the end of the paralysis assay. Paralysis was scored at 1 h intervals until the last worm became paralyzed.

Chemotaxis assays.

Chemotaxis assays (see Fig. 3 A) were performed as described by Bargmann et al. (1993). Synchronized transgenic C. elegans CL2355 and its control strain CL2122 were treated with or without 100 μg/ml EGb 761, or 10 μg/ml single components, starting from the egg. They were cultured in 16°C for 36 h, and then in 23°C for another 36 h. The worms were then collected, washed with M9 (Wood, 1988) three times, and assayed in 100 mm plates containing 1.9% agar, 1 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgSO4, and 25 mm phosphate buffer, pH 6.0. Twenty worms were placed to the center of the plate. After all animals were transferred to the center of the assay plate, 1 μl of odorant (0.1% benzaldehyde in 100% ethanol) (Sigma) along with 1 μl of 1 m sodium azide were added to the original spot. On the opposite side of the attractant, 1 μl drop of sodium azide and 1 μl of control odorant (100% ethanol) were added. Assay plates were incubated at 23°C for 1 h and chemotaxis index (CI) was scored. Chemotaxis index is defined as follows: (number of worms at the attractant location – number of worms at the control location)/total number of worms on the plate.

Figure 3.

Assays for chemotaxis behavior and serotonin sensitivity in neuronal Aβ-expressing strain CL2355. A, Schematic diagram of the chemotaxis assay. Synchronized L4 worms treated with or without drugs (20 worms for each assay) were placed in the center of an assay plate (100 × 15 mm) containing 1 μl of attractant (0.1% benzaldelhyde) plus 1 μl of 1 m sodium azide at the edge of the plate on one side (black dot), and 1 μl of control odorant (100% ethanol, *) plus 1 μl of 1 m sodium azide on the opposite edge of the plate (star). After 1 h incubation at room temperature, CI was scored as follows: CI = (number of worms at attractant − number of worms at control)/total number of worms. In each experiment, at least 60 worms from each group were analyzed. B, Chemotaxis behavior in neuronal strain CL2355 (neuronal Aβ strain) was reduced compared with the transgenic control strain CL2122 (no Aβ strain). Feeding with 100 μg/ml EGb 761 for 4 d alleviated this descent in the transgenic strain, but not in the control strains (n = 4; *p < 0.05). Error bars indicate SEM. C, Serotonin hypersensitivity in neuronal-expressing Aβ strain (CL2355) is normalized by EGb 761 and its constituents. Strain CL2355 were fed with EGb 761 (100 μg/ml), vehicle (Ctrl; 100 μg/ml), ginkgolides (GA, GB, GC, GJ) (10 μg/ml each), BB (10 μg/ml), quercetin (QC) (10 μg/ml), kaempferol (KA; 10 μg/ml) l-ascorbic acid (VC) (100 μg/ml), and CR (139 μg/ml) for 4 d. The worms were collected at 36 h after temperature upshift to 23°C. 5-HT sensitivity assay was conducted in 96-well plate containing 200 μl of 1 mm 5-HT solution. Percentage of active worms is calculated as follows: number of the active worms (after placed into serotonin solution for 5 min and still kept moving for 5 s)/total worms. A total of 60 worms of each group was used for each time (n = 3; **p < 0.01).

5-HT sensitivity assay.

Synchronized transgenic worms (CL2355) and the control strain (CL2122) fed with or without the drugs were collected at 36 h after temperature upshift. Serotonin (creatinine sulfate salt; Sigma) was dissolved in M9 buffer to 1 mm. Twenty worms in each group were washed with M9 buffer for three times and transferred into 200 μl serotonin solution in a 96-well assay plate. Worms were scored after 5 min as active or paralyzed (nonmotile for 5 s).

Western blotting of Aβ species.

The Aβ species in the transgenic C. elegans strains was identified by immunoblotting using a Tris-Tricine gel and the standard Western blotting protocol except that the polyvinylidene difluoride membranes were boiled for 5 min after the transfer. After the experimental treatments, the worms were collected by washing with distilled water, quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen, sonicated in the cell lysis buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 6 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 75 mm sucrose, 25 mm benzamide, 1 mm DTT, 1% Triton X-100), and heated with sample buffer containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol (1:1; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). To detect Aβ oligomers, samples were extracted in PBS containing proteinase inhibitor mixture (Sigma) with (for antibody A11) or without 2% SDS (for antibody NU-4). After mixing with the sample buffer, proteins were unheated and loaded on the gel. Equal amounts of the total protein (80 μg) were loaded in each lane. Antibody to Aβ1–17 (6E10; at 1:500 dilutions) was from Signet (Dedham, MA). Antibody selective against oligomers (A-11; at 1:1000 dilution) was from Biosource (Camarillo, CA) (Kayed et al., 2003). Antibody specific to Aβ oligomers (NU4; 1:3000) was generated in W. L. Klein's laboratory (Lambert, 2006). Anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG (1:5000; Signet) was used as the secondary antibody. The mean densities of the Aβ bands were analyzed by a gel documentation system (Alpha Innotech 801054; Imgen Technologies, Alexandria, VA).

Fluorescence staining of Aβ deposits.

Individual CL2006 transgenic nematodes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS, pH 7.4, for 24 h at 4°C, and permeabilized in 5% fresh β-mercaptoethanol, 1% Triton X-100, 125 mm Tris, pH 7.4, in a 37°C incubator for 24 h. The nematodes were stained with 0.125% thioflavin S (Sigma) in 50% ethanol for 2 min, destained, and mounted on slides for microscopy. Fluorescence images were acquired at the same exposure parameters using a 40× objective of the microscope (BX 60; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a digital camera (Micropublisher 5.0; QImaging, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada). The number of thioflavin S-reactive deposits in the area anterior of the pharyngeal bulb in individual animals was scored.

H2O2 assay in C. elegans.

Intracellular ROS were measured in C. elegans using 2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) as described previously (Smith and Luo, 2003). Age-synchronized C. elegans were collected at 36 h after temperature upshift (CL4176/1175) into 100 μl of PBS with 1% Tween 20 (PBST) in Eppendorf tubes in groups of 40 worms. The worms were then subjected to equally timed homogenization (Pellet Pestle Motor; MG Scientific, Pleasant Prairie, WI) and sonication (Branson Sonifier 250; VWR Scientific, Suwanee, GA) to break up the outer cuticle. Samples were collected into wells of 96-well plates. DCF-DA (final concentration, 50 μm in PBS) was added to each well at 37°C for quantification of fluorescence in an FLx800 Microplate Fluorescence Reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT) with the excitation at 485 nm and emission at 530 nm. Samples were read every 20 min for 2.5 h.

Statistical analyses.

Differences between untreated and drug-treated groups were analyzed for statistical significance by independent Student's t test of two groups using Origin 6.0 software (Microcal Software, Northampton, MA). A value of p < 0.05 is considered statistically significant. Correlation analysis was performed with the GraphPad (San Diego, CA) Prism 4.0a, using a one-tailed Pearson test.

Results

EGb 761, ginkgolide A and J alleviate Aβ-induced paralysis in the transgenic C. elegans

To determine whether EGb 761 specifically protects against Aβ-induced toxicity in vivo, we first fed EGb 761 to a transgenic C. elegans line, in which expression of human Aβ peptide in the muscle cells induces an Aβ-dependent paralysis phenotype in the worms (muscle Aβ strain, CL4176) (Link et al., 2003). Synchronized eggs from transgenic worms, or control worms were placed on OP50 food containing vehicle or EGb 761 (100 μg/ml) for 36 h at 16°C, followed by temperature upshift from 16 to 23°C to induce transgene expression. Figure 2 A is a set of photographs representing the following: the transgenic muscle Aβ expression strain (CL4176) without the temperature upshift and untreated with EGb 761 [control (Ctrl), no Aβ] (Fig. 2 A, left panel), the temperature upshifted (for 36 h) CL4176, untreated with EGb 761 (Ctrl, muscle Aβ) (Fig. 2 A, middle panel), or treated with EGb 761 (EGb, muscle Aβ) (Fig. 2 A, right panel). Worms that did not move or only moved the head, under a gentle touch with a platinum loop were scored as paralyzed. In Figure 2 A, the shape of movement and tracks left on the food (indicated with black lines) in nonparalyzed worms are obvious. The arrowheads indicate paralyzed worms (straight line shape), and the arrows indicate the moving worms (the “C” or “S” shape). At 36 h, ∼100% worms without the transgene expression were nonparalyzed (Fig. 2 A, left). At this time, only ∼20% Aβ transgene expressing worms without EGb feeding were nonparalyzed (Fig. 2 A, middle), and ∼60% transgene expressing worms fed with EGb were nonparalyzed (Fig. 2 A, right). Note the tracks left behind on the plate in the EGb 761-fed C. elegans (Fig. 2 A, right panel).

Figure 2.

Effect of EGb 761 and its constituents on Aβ-induced paralysis in muscle Aβ strain CL4176. A, Representative images of Aβ-induced paralysis in the transgenic CL4176 strain without transgene expression (no Aβ), untreated with EGb 761 (Ctrl; left panel), and in the transgenic CL4176 strain (muscle Aβ strain) fed with (EGb; right) or without EGb 761 (Ctrl; middle) at 36 h after temperature upshift. B, Time course of paralysis assays in CL4176 fed with different drugs. Synchronized eggs of CL4176 C. elegans were maintained at 16°C, on the 35 × 10 mm culture plates (∼35 eggs/plate) containing vehicle (Ctrl), EGb 761 (100 μg/ml), or CR (139 μg/ml). The hatched worms were grown for 38 h at 16°C followed by upshifting the temperature to 23°C to induce the transgene expression. The paralysis was scored at 60 min intervals. Data are expressed as percentage of nonparalyzed worms from at least three independent assays of 100 worms in each experiment. Paralysis in the transgenic strain CL4176 is attributable to Aβ expression compared with the control strain CL1175, which does not express Aβ transgene (filled triangles). C, Time course of paralysis assay in CL4176 worms fed with ginkgolide A or J (10 μg/ml for each). Paralysis was scored at 30 min intervals. Data were obtained from three different experiments with 100 worms in each group. Error bars indicate SEM. D, An illustrative diagram indicating the time duration of temperature upshift for expressing Aβ transgene, onset of paralysis, detectable Aβ, and EGb protective effect at different treatment regimens.

Figure 2 B is a time course of paralysis in the C. elegans CL4176 fed with a vehicle (0.01% ethanol; open circles), EGb 761 (EGb, 100 μg/ml; filled circles), or CR (139 μg/ml; filled squares) from day 1 till after the temperature upshift for 36 h. CL1175 (filled triangles) is a transgenic control strain that does not express Aβ. A notable delay of paralysis was observed in the transgenic worms fed with EGb 761 compared with the untreated controls. Congo red also moderately delayed paralysis. Interestingly, the worms fed with 100 μg/ml l-ascorbic acid, a known antioxidant, did not show any delay in paralysis (for clarity of the graph, data are presented only in Table 2). To further determine which constituent(s) of EGb 761 contributed to reducing Aβ-induced paralysis, transgenic C. elegans CL4176 were fed with GA, GB, GC, GJ, BB, and a flavonoid (Flav) fraction (10 μg/ml each). Among individual components tested, only GA and GJ exhibited significant delay of Aβ-induced paralysis (for clarity, the paralysis time courses for other components are not shown in Fig. 2 C) (for statistical analysis, see Table 1). Reproducibility of paralysis at a given temperature in individual trials was consistent. Because the transgene product is temperature sensitive, the onset of paralysis is related to the specific value of room temperature, at which the paralysis assays were conducted. Thus, the variation in the onset of paralysis between Figure 2, B and C, is attributed to the slight difference in room temperature on the days when the assays were performed (22 vs 23°C). Nevertheless, the difference between the worms fed with and without EGb 761 was consistently significant at both 22 and 23°C.

Table 2.

Quantitative analysis of paralysis

| Experiments | PT50 | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 5.7 ± 0.8 | |

| EGb 761 | 9.4 ± 1.3* | 0.03 |

| Ascorbic acid | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 0.17 |

| Congo red | 7.5 ± 0.8 | 0.15 |

| Control | 3.5 ± 0.3 | |

| Ginkgolide A | 7.2 ± 0.3** | 0.001 |

| Ginkgolide B | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 0.18 |

| Ginkgolide C | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 1.00 |

| Ginkgolide J | 6.8 ± 0.6* | 0.01 |

| Bilobalide B | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 0.18 |

| Flavonoids | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 0.24 |

The paralysis assays were quantified for mean time duration at which 50% worms were paralyzed (PT50) from the transgenic worms fed with or without the drugs. Values of p were obtained from nine independent assays for the worms fed with EGb 761 or Congo red, each paired with untreated controls, and from three assays for l-ascorbic acid, and single components paired with the control.

For quantitative analysis, we define PT50 as the time interval, from the onset of paralysis, at which 50% of the worms were paralyzed (i.e., PT50 of 5.7 h for control was obtained by subtracting the onset time of paralysis 27 h from the time when 50% of the worms were paralyzed at 32.7 h) (Table 1). A statistically significant delay of Aβ-induced paralysis was observed in the worms fed with EGb 761 (Table 2) (control vs EGb, p = 0.03; n = 9 assays; 40 worms in each assay group), but not in Congo red-treated animals (control vs CR, p = 0.15; n = 9 assays; 30 worms in each assay group). Among six single components of EGb 761, only ginkgolides A and J exhibited a statistically significant delay of paralysis (control vs GA, p = 0.001; control vs GJ, p = 0.01; n = 3 assays; 30 worms in each assay group). Moreover, EGb 761 feeding was found to delay paralysis through a wide range of concentrations (10–500 μg/ml) (data not shown). Paralysis was not delayed in the worms fed with EGb 761 before Aβ induction, at the time of Aβ induction, or after Aβ induction by temperature upshift (data not shown) (see diagram in Fig. 2 D), suggesting that short duration of feeding may not be sufficient to alleviate the Aβ toxicity.

EGb 761 suppresses neuronal Aβ expression-induced defect in chemotaxis behavior and 5-HT sensitivity

The paralysis phenotype in muscle of the Aβ expression strain CL4176, used above, has been established and used to illustrate several important molecular processes related to Aβ toxicity (Drake et al., 2003; Link et al., 2003). To relate Aβ toxicity with neurological functions, we characterized a behavior phenotype of the transgenic strain in which Aβ was expressed in the neuronal cells (CL2355). Two characteristic neuronal controlled behaviors, chemotaxis and 5-HT sensitivity, were assayed in these worms. The chemotaxis response in C. elegans is mediated by activation of several sensory neurons and interneurons to stimulate the motor neurons (Hobert, 2003). The CI is a measure of the fraction of worms that are able to arrive at the location of the attractants (Matsuura et al., 2005). To investigate the effect of EGb 761 on the performance of chemotaxis behavior, we applied the chemical benzaldehyde as an attractant and ethanol as a control, both containing sodium azide, which paralyzes the worms on contact (Fig. 3 A). The chemotaxis index was scored in the transgenic strain and the control strain at day 4 of age. Figure 3 B shows that the transgenic mutant CL2355 exhibits a significant reduction of CI compared with the control strain CL2122, or no Aβ strain untreated (Ctrl CIno Aβ, 0.36 ± 0.02 vs Ctrl CIAβ, 0.27 ± 0.02; n = 4; p = 0.01). EGb 761 feeding of the control strain had no effect on their CI (Ctrl CIno Aβ, 0.36 ± 0.02, vs EGb CIno Aβ, 0.35 ± 0.04; n = 4; p = 0.31), but it significantly normalizes the reduced CI in the neuronal Aβ transgenic strain (Ctrl CIAβ, 0.27 ± 0.02, vs EGb CIAβ, 0.37 ± 0.03; n = 4; p = 0.01; a total of 240 worms was used in each assay). A similar effect was observed in the transgenic worms fed with GA (Ctrl CIAβ, 0.27 ± 0.02, vs GA CIAβ, 0.34 ± 0.01; n = 4; p = 0.03).

Taking advantage of the ability of C. elegans to take up exogenous 5-HT (Sawin et al., 2000), we conducted a serotonin (5-HT) hypersensitivity assay to further determine whether 5-HT-mediated neurotransmission is affected by expressing Aβ transgene in the neurons. 5-HT is a key neurotransmitter that modulates several behaviors of C. elegans, including egg laying, locomotion, and olfactory learning (Schafer and Kenyon, 1995; Sawin et al., 2000; Nuttley et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2005). When exogenous 5-HT is applied to the nematodes, they become paralyzed as a result of the sensitivity to excessive 5-HT. This 5-HT sensitivity assay has previously been used to identify 5-HT hypersensitive mutants, which revealed the functional relationship of the genes involved in 5-HT signaling (Schafer et al., 1996; Ranganathan et al., 2001). We used this assay to test the response to 5-HT in the transgenic mutant CL2355 in comparison with the control strain CL2122. Twenty animals from each strain were placed in 200 μl of 5-HT solution (1 mm) in 96-well microtiter wells. Paralysis was scored at 5 min after exposure to 5-HT. Figure 3 C demonstrates that the transgenic neuronal line CL2355 untreated (Ctrl) was particularly sensitive to 5-HT, compared with the transgenic control CL2122 (no Aβ strain) untreated (percentage of CtrlCL2355, 35.9 ± 7.8%, vs percentage of CtrlCL2122, 73.2 ± 3.3; n = 3; p < 0.001). The neuronal Aβ worms (CL2355) then were fed with EGb 761 or its single components. Only feeding with EGb 761 (EGb vs Ctrl, 69.5 ± 4.9%, vs 35.9 ± 7.8%; n = 3; p = 0.003) and ginkgolide A (GA vs Ctrl, 65.5 ± 4.0, vs 35.9 ± 7.8%; n = 3; p = 0.005) significantly normalized the defective response to 5-HT in the transgenic strain. Neither the antioxidant l-ascorbic acid (VC), kaempferol, the flavonoid fraction of EGb 761 (KA), or CR normalized the paralysis in the neuronal Aβ strain CL2355.

Among behavior assays available to examine neuronal toxicity (including egg laying, body bend, pharyngeal pumping, locomotion/swimming, and paralysis), the serotonin sensitivity assay (swimming) was performed to determine a behavior phenotype in neuronal Aβ-expressing strain for the following reasons: (1) early work by Horvitz et al. (1982) demonstrated that exogenous 5-HT affected the wild-type C. elegans locomotion, or swimming behavior. Subsequently, it was reported that the effect was blocked in the MOD-1 mutant (a 5-HT-gated chloride channel) (Ranganathan et al., 2000), suggesting that this assay measures a 5-HT-mediated response; (2) in C. elegans, the experience-dependent behavior (an enhanced slowing of the response) is modulated by 5-HT (Sawin et al., 2000), which provides a link between the behavior plasticity and the neuronal plasticity associated with the impairment of cognitive function observed in AD; (3) among others, this phenotype exhibited the most significant difference between the control strain (CL2122) and the transgenic strain (CL2355). Thus, the Aβ-dependent behavior may provide the opportunity to elucidate 5-HT-mediated neuroprotection against Aβ neurotoxicity.

EGb 761 modulates Aβ oligomers in the transgenic C. elegans

To determine whether inhibition of Aβ oligomerization by EGb 761 underpins its mechanism for suppressing pathological behaviors in C. elegans, we analyzed Aβ species from the transgenic C. elegans fed with or without EGb 761 by Western blotting using antibodies against Aβ (6E10) or specific against Aβ oligomers (A-11 and NU-4). Figure 4 A shows Aβ-immunoreactive (6E10) bands (M r, ∼7.2–28 kDa) detected in the tissues from the transgenic worms (CL4176) fed with or without EGb 761 and the comparison chemicals. Two immunoreactive Aβ species with molecular weights at ∼20 and 28 kDa were significantly decreased in the worms fed with EGb 761 (100 μg/ml for 72 h) (Fig. 4 A, EGb, lane 3). Interestingly, a simultaneous increase of the Aβ monomers was observed in those worms. Consistent with the observation in CL4176, a similar inhibitory effect by EGb 761 was observed in the transgenic strain CL2006. In this strain, EGb 761 inhibited the same Aβ species and, at the same time, increased Aβ monomers in the same tissue extract (data not shown). In contrast, l-ascorbic acid (VC) (100 μg/ml for 72 h) did not inhibit the Aβ oligomerization or increase the monomer content as EGb 761 did, in the transgenic worm CL4176 (Fig. 4 A, lane 4). CR (139 μg/ml) inhibited the oligomerization to a lesser degree than EGb 761 but also failed to increase the Aβ monomer content in the same samples in the transgenic worms (Fig. 4 A, CR, lane 5). The mean densities of the Aβ oligomer band at ∼20 kDa as well as the Aβ monomer bands were analyzed. Statistically (Fig. 4 B), EGb 761 and Congo red significantly reduced the oligomers (Fig. 4 B, solid bars) (n = 3; control vs EGb, p = 0.04; Ctrl vs CR, p = 0.02). Most importantly, only EGb 761 significantly increased the Aβ monomers from the same C. elegans samples (Fig. 4 B, dashed bars) (n = 3; control vs EGb, p = 0.01).

Figure 4.

Aβ species in the transgenic C. elegans. A, Representative Western blot (BL) of Aβ species in the transgenic C. elegans CL4176 fed with or without EGb 761 (EGb), l-ascorbic acid (VC), and CR. The CL4176 worms maintained at 16°C were fed with a vehicle (Ctrl), EGb 761 (100 μg/ml), or l-ascorbic acid (100 μg/ml), Congo red (139 μg/ml) at day 1 of age for 72 h. The worms were collected, and equal amounts of protein were loaded on each gel lane and immunoblotted with an anti-Aβ antibody (6E10). The arrow indicates changes of Aβ oligomers and the monomers in the worms after the treatment. B, Quantification of immunoreactive Aβ oligomers (the bend at 20 kDa; filled bars) and Aβ monomers (dashed bars) by Gel Documentary System Fluochem SP (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA). Data are expressed as mean density of an indicated band from three independent experiments. Error bars represent SEM. *p < 0.05 C, Aβ species in transgenic C. elegans CL4176 fed with or without EGb 761 (100 μg/ml), GA, GB, GC, GJ, BB, and a flavonol diglycosides quercetin (QC) (10 μg/ml for each component). Aβ oligomers (top) and the protein loading control actin (bottom) are indicated. Note that immunoreactive Aβ monomers (arrow on the right) are enhanced in worms fed with GA. D, Quantification of immunoreactive Aβ oligomers (solid bars) and Aβ monomers (dashed bars) from three independent experiments. Error bars represent SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; # p < 0.05 (4 kDa monomer). E, Immunoblot using antibody A11 (anti-oligomers) in the C. elegans strains CL4176 fed with EGb 761 (100 μg/ml) or vehicle (Ctrl) for 4 d. The blot represents three independent experiments. F, Immunoblot using NU-4 (anti-Aβ oligomers) antibody in C. elegans strains CL4176 and CL2355 (-Tg) fed with EGb 761 (100 μg/ml) or vehicle (Ctrl). The blot represents two independent experiments. G, An integrated myo-3/GFP strain (CL2179), as a control for CL4176, was fed with (bottom panel) or without (top) EGb 761 in the same way as CL4176 in A. GFP fluorescence was examined at 36 h after temperature upshift, under a 20× objective on the fluorescence microscope (E800; Nikon). The images were processed by IPLab software 3.7 (Scanalytics, Fairfax, VA). No difference in GFP fluorescence density and intensity were observed in the two groups.

Neuroprotection by EGb 761 is known as a “multipotent” action (i.e., it is achieved by modulating a variety of biological pathways simultaneously because of its complex nature) (DeFeudis, 2002; Smith and Luo, 2003). We next asked whether the inhibitory effect on oligomerization by an individual constituent is sufficient to correlate with its alleviative effect on Aβ-induced paralysis. The transgenic C. elegans was fed with different single constituents and Aβ species were analyzed by Western blotting using antibody 6E10. Figure 4 C represents a noticeable shift of Aβ oligomer species to monomers by EGb 761 and ginkgolide A. Blots from three independent experiments were quantified in Figure 4 D. It shows that EGb 761 (EGb), GA, and GJ remarkably reduced the Aβ oligomers band (filled bars) (Ctrl vs EGb, **p = 0.006; Ctrl vs GA, **p = 0.006; Ctrl vs GJ, **p = 0.007). GB, GC, and GJ also significantly reduced this Aβ species, to a somehow lesser degree (Ctrl vs GB, *p = 0.04; Ctrl vs GC, *p = 0.04), compared with untreated transgenic worms (Ctrl). Only EGb 761 and GA significantly enhanced the Aβ monomers (dashed bars) (Ctrl vs EGb, #p = 0.02; Ctrl vs GA, #p = 0.03).

To confirm the properties of the Aβ species modulated by EGb 761, we used two independent antibodies A11 (Fig. 4 E) and NU4 (Fig. 4 F). Antibody A11 is selective for high molecular weight Aβ oligomers as well as other oligomeric proteins (Kayed et al., 2003). This antibody was used to reveal a temporal profile of Aβ oligomerization in mice model of AD (Oddo et al., 2006). Antibody NU-4 is a mice monoclonal antibody generated in the W. L. Klein laboratory (Lambert, 2006), which is an improved version of the previously generated low molecular weight oligomer [Aβ-derived diffusible ligand (ADDL)]-selective polyclonal rabbit antibody (M93/M94) (Lambert et al., 2001). Levels of oligomers reactive to this antibody have been reported to be 70-fold higher in the AD patient's brain compared with the control brains (Gong et al., 2003). Prevention by EGb 761 of the oligomer formation in vitro was demonstrated using this antibody (Chromy et al., 2003).

Multiple immunoreactive bands were recognized by A11 in the transgenic C. elegans CL4176 (Fig. 4 E, lane 2). Among these, a major band at ∼50 kDa disappeared in the CL4176 strain fed with EGb 761 (Fig. 4 E, lane 3). The blot is representative of three independent experiments. Because A11 also recognizes oligomeric structures other than Aβ, we further performed the immunoblotting using an antibody specific to the toxic Aβ oligomers referred to as ADDL (NU-4). Figure 4 F is representative of two independent blots using antibody NU-4. An immunoreactive band at 50 kDa, presumably a 12-mer species previously found to be abundant in AD brain (Gong et al., 2003), was detected only in the transgenic strain CL4176, but not in the transgenic control strain. EGb 761 inhibited formation of this species completely (Fig. 4 F, lane 3). EGb 761 also inhibited formation of higher-order Aβ species (∼70–80 kDa, probably 16- to 18-mers) in the neuronal strain CL2355. In addition, the Aβ species detected by 6E10 and A11/NU4 do not overlap, in terms of the size, which suggests that multiple Aβ oligomers are attenuated by EGb 761. The shift from larger Aβ oligomers to monomers caused by EGb 761 is striking, but it only can be detected by 6E10, because A11 and Nu-4 do not recognize monomeric Aβ (Chromy et al., 2003; Lambert, 2006).

To determine whether EGb 761 affects the expression levels of the Aβ transgene, rather than interacting with the Aβ peptide species, an integrated myo-3/GFP strain (CL2179) with the same promoter tagged with a GFP reporter was used as a control for CL4176. To determine whether EGb 761 affects transcription of the transgenes, the strain was handled the same way as CL4176, in terms of temperature upshift regimen and EGb 761 feeding. Figure 4 G shows that comparing the worms (CL2179) fed with or without EGb, there is no visible difference in GFP fluorescence density and intensity in the two groups, suggesting that EGb 761 feeding does not affect the levels of Aβ transgene expression in the worms. Data from a microarray of the transgenic worms fed with or without EGb 761 further supported this observation (data not shown).

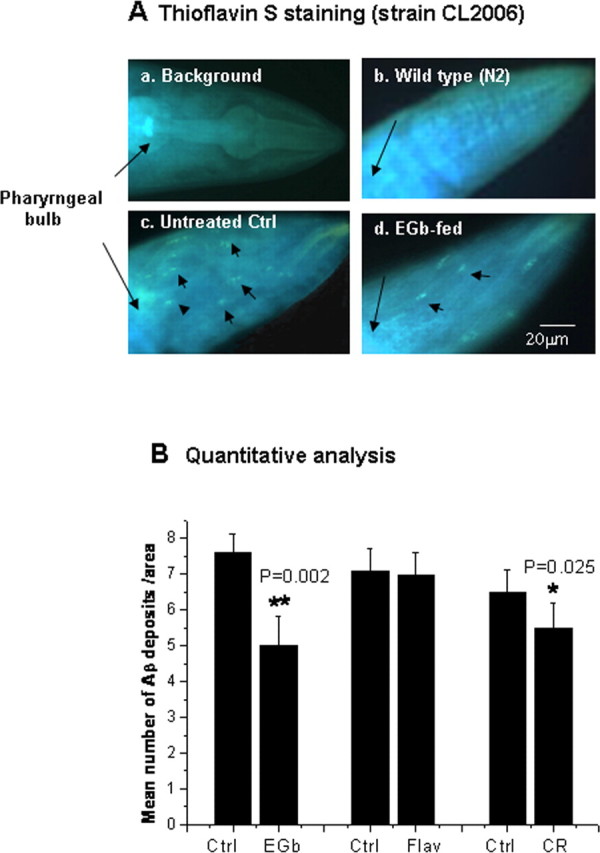

EGb 761 inhibits amyloid deposits in transgenic C. elegans

To decide whether the inhibitory effect of EGb 761 on Aβ oligomerization would affect amyloid formation, the number of amyloid deposits was scored in the worm head region, which is separated from the rest of the body by the pharyngeal bulb (black arrows). Figure 5 A shows Aβ deposits (black arrowheads) detected in the transgenic C. elegans (CL2006) (Fig. 5 Ac) but not the wild type (N2) (Fig. 5 Ab), as previously observed (Link, 1995). The number of Aβ deposits per nematode was reduced in the transgenic C. elegans CL2006 fed with EGb 761 (Fig. 5 Ad). The worms exhibit background fluorescence without thioflavin S staining (Fig. 5 Aa), which provides a guide to define the head area in the animals. Figure 5 B shows that the mean number of Aβ deposits, from 24 worms in each group, was significantly reduced in worms fed with 100 μg/ml EGb 761 (Ctrl, 7.7 ± 0.5, vs EGb, 4.9 ± 0.6; n = 24; p = 0.002) or with 200 μm Congo red (Ctrl, 6.2 ± 0.8, vs CR, 5.5 ± 1.1; n = 24; p = 0.025), but not with the flavonoid fraction of EGb 761 (Ctrl, 7.1 ± 0.9, vs Flav, 6.9 ± 1.0; n = 24; p > 0.05). These results suggest that EGb 761 inhibits Aβ oligomerization, which leads to an increase in the nontoxic Aβ monomers and the reduced amyloid deposits. Congo red, which binds to Aβ fibrils, also reduced the Aβ deposits in C. elegans.

Figure 5.

Aβ deposits in transgenic C. elegans CL2006 fed with or without drugs. A, Representative images of background fluorescence in a C. elegans without staining (a), with thioflavin S staining in the wild type (b), or in the transgenic strain CL2006 fed with (d) or without EGb 761 (c). Synchronized CL2006 worms were maintained at 20°C on NGM agar plates seeded with E. coli as the food source. The worms were fed with EGb 761 or Congo red for 2 d starting at day 4 of age. At the end of the treatment, the nematodes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized, and then stained with 0.125% thioflavin S. β-Amyloid deposits were examined using a fluorescence microscope attached to a digital camera. The numbers of deposits (arrowheads) were scored in the worm head, which is separated from the body by pharyngeal bulb (arrows). B, Quantitative analysis of β-amyloid deposits in the transgenic C. elegans CL2006 fed with different chemicals for 48 h (EGb 761, 100 μg/ml; the flavonoid fraction of EGb 761, 100 μg/ml; Congo red, 139 μg/ml). The quantity is expressed as mean number of β-amyloid deposits/anterior area of the worm (n = 24 for each analysis). Error bars indicate SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Levels of H2O2 in the transgenic C. elegans fed with EGb 761 and other chemicals

Given that numerous lines of evidence have associated oxidative stress with AD and Aβ toxicity, we hypothesized that the antioxidative properties also contribute to the protective effects of EGb 761 against Aβ toxicity. We first tested the levels of H2O2 in the transgenic control strain (CL1175) and the transgenic muscle Aβ strain (CL4176). Figure 6 A demonstrates that the untreated transgenic strain CL4176 (Ctrl) exhibits increased levels of H2O2 compared with the control strain (CL1175) that does not express Aβ (no Aβ strain, p = 0.001). Next, we asked whether feeding EGb 761 to the worms before the induction of Aβ expression would prevent the elevation of H2O2 levels in the strain CL4176. Three concentrations of EGb 761 (25, 50, and 100 μg/ml) were added to the transgenic C. elegans diet from day 1 of age until the end of the temperature upshift. Feeding EGb 761 attenuated the intracellular levels of H2O2 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6 A). Feeding 100 μg/ml EGb 761 exhibited most significant reduction (Ctrl, 100 ± 23%; EGb, 42 ± 7%; n = 6; p = 0.04). Interestingly, no significant reduction was observed in the control worms fed with EGb 761 (Fig. 6 A), suggesting that the effect of EGb 761 on attenuating H2O2 may be specific to Aβ expression. In comparison, 50 μg/ml l-ascorbic acid (VC) (Ctrl, 100 ± 3%; VC, 31 ± 3%; n = 3, p = 0.04), but not CR (139 μg/ml) (Ctrl, 100 ± 3%; CR, 101 ± 18%; n = 3; p = 0.11; total of 300 worms in each group), also showed significant attenuation of the Aβ-induced elevation of H2O2. Among single components of EGb 761 tested (10 μg/ml for each), only ginkgolide A significantly attenuated the levels of H2O2 (p = 0.047) (Fig. 6 C).

Figure 6.

Levels of ROS in transgenic C. elegans. A, Levels of H2O2 in the C. elegans fed with different concentration of EGb 761 (0, 25, 50, 100 μg/ml). Age-synchronized groups of transgenic C. elegans strain CL4176 and the control strain CL1175 maintained at 16°C for 38 h were temperature upshifted to 23°C for 38 h followed by the DCF assay for H2O2 described in Materials and Methods. Statistical significance is observed in the worms fed with 100 μg/ml EGb 761 (25 μg/ml, p = 0.13; 50 μg/ml, p = 0.09; 100 μg/ml, p = 0.03; n = 3; total of 120 worms in each group). B, Levels of H2O2 in CL4176 worms fed with vehicle (Ctrl), EGb 761 (EGb), l-ascorbic acid (VC), or CR from 1 d of age until 3 d of age. C, Levels of H2O2 in the C. elegans fed with different constituents of EGb 761 (ginkgolides GA, GB, GC, GJ). At least 60 animals from each group were analyzed for the levels of H2O2. Results are expressed as percentage of fluorescence (%DCF) relative to vehicle-treated controls, which is set as 100%. Statistical significance is represented as follows: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. Error bars indicate SEM.

Paralysis is associated with Aβ oligomers but not the level of H2O2

To determine whether there is a correlative association between the behavioral rescue and the decrease in Aβ oligomers by EGb 761 and its constituents, correlation analysis was performed. Figure 7 A shows a clear correlation between the amount of Aβ oligomers (mean density) and paralysis (PT50), with a value of the Pearson correlation coefficient r of 0.566 (p = 0.044). Among all of the compounds, GJ, GA, and EGb 761 appear to contribute the most to the correlation, in contrast with GC, GB, and BB. The latter three compounds decrease the Aβ oligomers density without improving the worms' paralysis. Figure 7 B is a plot of paralysis (PT50) versus levels of H2O2 measured by DCF fluorescence (see Materials and Methods). Paralysis is dissociated from the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS), because no correlation of the paralysis with the levels of H2O2 was found. The value of the Pearson correlation coefficient r was 0.27 (p = 0.07).

Figure 7.

Correlation analysis between paralysis (PT50) and 20 kDa Aβ oligomers (A) or with levels of H2O2 (B). Correlation analysis was performed with the GraphPad Prism 4.0a, using a one-tailed Pearson test. The linear regression line along with the 95% confidence interval is shown only for illustrative purposes.

As summarized in Table 3, chemotaxis behavior does not correlate with the mean density of the Aβ oligomers. It is possible that the chemosensory neural circuits are less sensitive to the Aβ toxicity, and thus the chemotaxis behavior may not be the best assay for the latter. However, the serotonin hypersensitivity and paralysis correlate well with the Aβ oligomers density, supporting our hypothesis that EGb 761 and its constituents alleviate the behavioral abnormalities by decreasing the levels of the toxic Aβ oligomers.

Table 3.

Summary of correlation analysis

| Behavior | Pearson r value | p value | Correlation with Aβ oligomers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paralysis | −0.566 | 0.044 | Yes |

| 5-HT sensitivity | −0.644 | 0.043 | Yes |

| Chemotaxis | −0.451 | 0.131 | No |

The data are from 10 different drugs tested in three behavior assays. Correlation of paralysis (PT50), chemotaxis (CI), and 5-HT sensitivity with the 20 kDa Aβ oligomers mean density was tested by Pearson's test (see Materials and Methods).

Discussion

In the present experiments, we sought to associate Aβ species with Aβ-specific pathological behaviors using transgenic C. elegans as a model and EGb 761 as a pharmacological modulator. We found that EGb 761 alleviated Aβ-induced paralysis, chemotaxis dysfunction, and 5-HT hypersensitivity in the transgenic C. elegans expressing Aβ. EGb 761 also modulated Aβ oligomers and attenuated levels of H2O2 in the transgenic C. elegans (CL4176). Interestingly, suppression of paralysis is associated with inhibition of Aβ oligomerization but is disassociated with the antioxidative effect (Fig. 7 A,B), suggesting that protective effects of EGb 761 against Aβ toxicity is mediated primarily by inhibition of Aβ oligomerization. If a similar mechanism is shared with other species, it may represent a rationale for the beneficial effects of EGb 761 in humans with AD-related dementia (Le Bars et al., 2000; Mazza et al., 2006) and for the enhanced cognitive function by EGb 761 in the transgenic mice model of AD (Tg2576) (Stackman et al., 2003).

EGb 761 has been known as an antioxidant that protects neuronal cells against amyloid toxicity in the cells (Bastianetto et al., 2000; Yao et al., 2001). We demonstrate here that EGb 761 and ginkgolide A suppress both Aβ oligomerization and Aβ-induced paralysis in a model organism, in a manner that does not parallel the effects of known antioxidants. We believe that the effect of EGb 761 and ginkgolide A on Aβ toxicity is specific for the following reasons.

EGb 761 modulates Aβ specific pathological behaviors (Figs. 2, 3)

C. elegans is an ideal model organism for functional analysis of the age-associated neurodegeneration because of its available genetic information as well as the simple structure of its nervous system, which consist of only 302 neurons in an adult nematode. We took advantage of an established relationship between onset of Aβ expression and paralysis phenotype in a transgenic C. elegans model (Link, 1995). The absence of endogenous Aβ production in the worms offers an opportunity to find a direct role of the Aβ involvement in pathological behaviors (Wu and Luo, 2005). In addition, predominantly intracellular expression of Aβ provides another tool to address specific role of intracellular Aβ in relation to its toxicity (Gutierrez-Zepeda and Luo, 2004). Substantial evidence implicates intracellular Aβ oligomers in early events related to AD (Kienlen-Campard et al., 2002).

For the first time, two neuronal behavior phenotypes were characterized in a neuronal Aβ-expressing strain CL2355. Both chemotaxis and 5-HT signaling phenotypes are biologically relevant to Aβ-induced toxicity. C. elegans uses six primary sensory neurons to respond to >40 different attractants and repellents (Bargmann et al., 1993). The reinforcement is mediated by 5-HT signaling in the worms (Zhang et al., 2005). Several possible mechanisms could explain the 5-HT hypersensitive phenotype of the Aβ transgene, including the following: (1) response to 5-HT, which is modulated by calcium channel-dependent calcium influx (Schafer and Kenyon, 1995), was affected by the transgene Aβ expression (Ingram, 2005); (2) reduced acetylcholine (ACh) by Aβ accumulation in the worms; ACh is a negative regulator of 5-HT sensitivity in C. elegans (Schafer et al., 1996); and (3) Aβ may directly or indirectly block 5-HT reuptake in the worms. The pathological behavior assays used here are simple and relatively reproducible compared with other behavior assays in the worms. Whether this form of pathological behavior uses molecular mechanisms common to higher animals remains to be determined. A similar approach has recently revealed polyglutamine threshold toxicity in a transgenic C. elegans model of Huntington's disease (Brignull et al., 2006).

EGb 761 and ginkgolide A inhibit Aβ oligomerization (Fig. 4 A–D)

Accumulation of Aβ oligomers seems to be one of the earliest events in the transgenic mice of AD (Oddo et al., 2006), which impairs long-term potentiation (LTP) and memory (Walsh et al., 2005; Lesne et al., 2006) and which correlates better with severity of dementia in AD patients than the density of amyloid plaques (Gong et al., 2003). Some oligomers (∼20 kDa) inhibited by EGb 761 and ginkgolide A, as observed in this study (Fig. 4 A–D), might be similar to, or identical with the neurotoxic ADDLs, or Aβ-derived diffusible ligands (Lambert et al., 1998). Previous studies showed that EGb 761 could inhibit formation of these species in solution (Luo et al., 2002; Chromy et al., 2003). The higher-order Aβ oligomers (∼50 kDa) inhibited by EGb 761 in the worms (Fig. 4 E,F) might be relevant to the species previously reported to be abundant in the AD brain (Gong et al., 2003). Our results suggest, but do not prove, that all of the oligomeric Aβ species inhibited by EGb 761 and ginkgolide A are toxic.

Based on in vitro studies, a linear pathway leading from Aβ monomers via paranuclei, oligomers, to protofibrils, and then to fibrils was proposed (Bitan et al., 2003; Urbanc et al., 2004). This pathway may provide an explanation for our observation that Congo red, although it reduced Aβ deposits (Fig. 5 B), did not significantly delay Aβ-induced paralysis (Fig. 2 B). We speculate that EGb 761 and Congo red may bind to Aβ oligomers differently. For example, EGb 761 may have a higher affinity for certain oligomeric species, whereas Congo red favors the fibril form of Aβ. Thus, Congo red probably enters the linear process of fibrillogenesis at later stages than EGb 761, which would still lead to reduced overall Aβ oligomers (Fig. 4 A) and decreased Aβ deposits (Fig. 5 B), but not the appearance of Aβ monomers or significant suppression of paralysis (Fig. 2 B) in the transgenic C. elegans. This theory agrees with the previous observation that paralysis occurs before detectable β-amyloid deposition in C. elegans (Drake et al., 2003). Therefore, the paralysis suppression by EGb 761 and ginkgolide A might be a consequence of the shift from the toxic Aβ oligomer to the nontoxic Aβ monomers (Fig. 4 A). Given its “multipotent” nature, it is also possible that EGb 761 differentially modulates different processes of oligomerization.

The unique structure of ginkgolide A provides a rationale for its specific effect

It is believed that the unique biological properties of ginkgolides arise from their unique “cage skeleton” structure. This structure may share a common motif with Congo red and/or curcumin (Yang et al., 2005), which all display affinity for amyloidogenic conformations. It is not surprising that, among all ginkgolides, only GA exhibited a correlation between reducing paralysis (Fig. 2 C) and inhibiting Aβ oligomers (Fig. 4 C,D). Biological effects of ginkgolides can markedly vary with minor differences in their chemical structure. For example, the presence of one extra hydroxyl group at position 7 converts GB, a potent PAFR antagonist (K i = 0.88 μm) into GC, a constituent with much lower activity (K i = 12.6 μm) (Vogensen et al., 2003). Indeed, GA and GJ are the components of the extract that inhibit or even eliminate the deadly effects of Aβ on LTP (Nakanishi, 2005). GB affects hippocampal LTP by inhibiting the PAFR (Kondratskaya et al., 2004). Given that very little is known about which components of EGb 761 are the most efficacious, additional analyses of specific molecular structures of ginkgolides and of their interactions with Aβ may reveal novel compound(s) to protect against AD.

The fact that the antioxidant l-ascorbic acid lowered the levels of H2O2 (Fig. 6 B), but did not inhibit Aβ oligomerization (Fig. 4 A–C) nor suppressed paralysis (Table 2), suggests that a mechanism(s) other than the relief from antioxidative stress is operative in the ginkgolide-mediated protection against Aβ toxicity in C. elegans. This finding is consistent with the in vitro observation that no correlation exists between relative potencies of polyphenols in inhibiting Aβ fibrils formation and in their oxidative features (Ono and Yamada, 2006). However, the dissociation of antioxidative effect from delaying paralysis does not rule out the contribution of oxidative damage in Aβ-dependent abnormal behaviors. Recent reports demonstrate that Aβ-induced, and a pro-aggregation-protein-induced paralysis in transgenic C. elegans were reduced by slowing aging (Cohen et al., 2006), or by coexpression of a stress response protein, the small heat shock protein 16 (sHSP-16) (Link et al., 2006) in the worms, respectively. EGb 761 attenuated the expression of sHSP-16 protein in the wild-type worms exposed to oxidative stress (Strayer et al., 2003). A possible explanation is that EGb 761 might act in a manner similar to that of sHSP-16 in protecting against the deleterious process, which would lead to a decreased need for sHSP-16 expression. The antioxidative action of EGb 761 (Fig. 6 B) may contribute to the beneficial effect in AD (Zandi et al., 2004), without being manifested in C. elegans.

Together, the neuroprotective effects of EGb 761 and ginkgolides on transgenic C. elegans behaviors provide strong evidence that formation of intracellular Aβ1–42 oligomers is directly associated with Aβ toxicity, supporting the view that the Aβ oligomers are the toxic species in AD (Kayed et al., 2003; Walsh and Selkoe, 2004). It is likely that the sequence of events manifested in the behavior of the transgenic worms, as well as the pharmacological efficacy, share the similar mechanisms with the cognitive impairment in mammals.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01AT001928-03A1 (Y.L.) from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine and by Ipsen (Paris, France). We thank Dr. Dominic Walsh of University College Dublin (Dublin, Ireland) for helpful discussion and Zhiming Cao for technical assistance.

References

- Andrieu et al., 2003.Andrieu S, Gillette S, Amouyal K, Nourhashemi F, Reynish E, Ousset PJ, Albarede JL, Vellas B, Grandjean H. Association of Alzheimer's disease onset with Ginkgo biloba and other symptomatic cognitive treatments in a population of women aged 75 years and older from the EPIDOS study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:372–377. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.4.m372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann et al., 1993.Bargmann CI, Hartwieg E, Horvitz HR. Odorant-selective genes and neurons mediate olfaction in C. elegans . Cell. 1993;74:515–527. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80053-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastianetto et al., 2000.Bastianetto S, Ramassamy C, Dore S, Christen Y, Poirier J, Quirion R. The Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761) protects hippocampal neurons against cell death induced by beta-amyloid. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:1882–1890. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birks et al., 2002.Birks J, Grimley EV, Van Dongen M. Ginkgo biloba for cognitive impairment and dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;4:CD003120. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitan et al., 2003.Bitan G, Kirkitadze MD, Lomakin A, Vollers SS, Benedek GB, Teplow DB. Amyloid beta-protein (Abeta) assembly: Abeta 40 and Abeta 42 oligomerize through distinct pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:330–335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222681699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brignull et al., 2006.Brignull HR, Moore FE, Tang SJ, Morimoto RI. Polyglutamine proteins at the pathogenic threshold display neuron-specific aggregation in a pan-neuronal Caenorhabditis elegans model. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7597–7606. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0990-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christen and Maixent, 2002.Christen Y, Maixent JM. What is Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761? An overview—from molecular biology to clinical medicine. Cell and Mol Biol. 2002;48:601–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chromy et al., 2003.Chromy BA, Nowak RJ, Lambert MP, Viola KL, Chang L, Velasco PT, Jones BW, Fernandez SJ, Lacor PN, Horowitz P, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL. Self-assembly of Abeta(1–42) into globular neurotoxins. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12749–12760. doi: 10.1021/bi030029q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen et al., 2006.Cohen E, Bieschke J, Perciavalle RM, Kelly JW, Dillin A. Opposing activities protect against age-onset proteotoxicity. Science. 2006;313:1604–1610. doi: 10.1126/science.1124646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFeudis, 1998.DeFeudis FV. Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761): from chemistry to clinic. Weisbaden, Germany: Ullstein Medical; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- DeFeudis, 2002.DeFeudis FV. Effects of Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb761) on gene expression: possible relevance to neurological disorders and age-associated cognitive impairment. Drug Dev Res. 2002;57:214–235. [Google Scholar]

- DeKosky et al., 2006.DeKosky ST, Fitzpatrick A, Ives DG, Saxton J, Williamson J, Lopez OL, Burke G, Fried L, Kuller LH, Robbins J, Tracy R, Woolard N, Dunn L, Kronmal R, Nahin R, Furberg C. The Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory (GEM) study: design and baseline data of a randomized trial of Ginkgo biloba extract in prevention of dementia. Contemp Clin Trials. 2006;27:238–253. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake et al., 2003.Drake J, Link CD, Butterfield DA. Oxidative stress precedes fibrillar deposition of Alzheimer's disease amyloid beta-peptide (1–42) in a transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans model. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:415–420. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00225-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong et al., 2003.Gong Y, Chang L, Viola KL, Lacor PN, Lambert MP, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL. Alzheimer's disease-affected brain: presence of oligomeric A beta ligands (ADDLs) suggests a molecular basis for reversible memory loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10417–10422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834302100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Zepeda and Luo, 2004.Gutierrez-Zepeda A, Luo Y. Testing the amyloid toxicity hypothesis of alzheimer's disease in transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans model. Front Biosci. 2004;9:3333–3338. doi: 10.2741/1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy and Selkoe, 2002.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobert, 2003.Hobert O. Behavioral plasticity in C. elegans: paradigms, circuits, genes. J Neurobiol. 2003;54:203–223. doi: 10.1002/neu.10168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz et al., 1982.Horvitz HR, Chalfie M, Trent C, Sulston JE, Evans PD. Serotonin and octopamine in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans . Science. 1982;216:1012–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.6805073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, 2005.Ingram VM. The role of Alzheimer Abeta peptides in ion transport across cell membranes. Subcell Biochem. 2005;38:339–349. doi: 10.1007/0-387-23226-5_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivic et al., 2003.Ivic L, Sands TT, Fishkin N, Nakanishi K, Kriegstein AR, Stromgaard K. Terpene trilactones from Ginkgo biloba are antagonists of cortical glycine and GABA(A) receptors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49279–49285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaracz et al., 2004.Jaracz S, Malik S, Nakanishi K. Isolation of ginkgolides A, B, C, J and bilobalide from G. biloba extracts. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:2897–2902. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed et al., 2003.Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kienlen-Campard et al., 2002.Kienlen-Campard P, Miolet S, Tasiaux B, Octave JN. Intracellular amyloid-beta 1–42, but not extracellular soluble amyloid-beta peptides, induces neuronal apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15666–15670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200887200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondratskaya et al., 2004.Kondratskaya EL, Pankratov YV, Lalo UV, Chatterjee SS, Krishtal OA. Inhibition of hippocampal LTP by ginkgolide B is mediated by its blocking action on PAF rather than glycine receptors. Neurochem Int. 2004;44:171–177. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(03)00126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, 2006.Lambert MP. Monoclonal antibodies that target pathological assemblies of Aβ. J Neurochem. 2006 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04157.x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert et al., 1998.Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, Morgan TE, Rozovsky I, Trommer B, Viola KL, Wals P, Zhang C, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Abeta1–42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert et al., 2001.Lambert MP, Viola KL, Chromy BA, Chang L, Morgan TE, Yu J, Venton DL, Krafft GA, Finch CE, Klein WL. Vaccination with soluble Abeta oligomers generates toxicity-neutralizing antibodies. J Neurochem. 2001;79:595–605. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bars, 2003.Le Bars PL. Magnitude of effect and special approach to Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761 in cognitive disorders. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36(Suppl 1):S44–S49. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bars et al., 1997.Le Bars PL, Katz MM, Berman N, Itil TM, Freedman AM, Schatzberg AF. A placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial of an extract of Ginkgo biloba for dementia. North Am EGb Study Group. JAMA. 1997;278:1327–1332. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.16.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bars et al., 2000.Le Bars PL, Kieser M, Itil KZ. A 26-week analysis of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761 in dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2000;11:230–237. doi: 10.1159/000017242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesne et al., 2006.Lesne S, Koh MT, Kotilinek L, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Yang A, Gallagher M, Ashe KH. A specific amyloid-beta protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 2006;440:352–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link, 1995.Link CD. Expression of human beta-amyloid peptide in transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9368–9372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link, 2005.Link CD. Invertebrate models of Alzheimer's disease. Genes Brain Behav. 2005;4:147–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2004.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link et al., 2001.Link CD, Johnson CJ, Fonte V, Paupard M, Hall DH, Styren S, Mathis CA, Klunk WE. Visualization of fibrillar amyloid deposits in living, transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans animals using the sensitive amyloid dye, X-34. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:217–226. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link et al., 2003.Link CD, Taft A, Kapulkin V, Duke K, Kim S, Fei Q, Wood DE, Sahagan BG. Gene expression analysis in a transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans Alzheimer's disease model. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:397–413. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link et al., 2006.Link CD, Fonte V, Hiester B, Yerg J, Ferguson J, Csontos S, Silverman MA, Stein GH. Conversion of green fluorescent protein into a toxic, aggregation-prone protein by C-terminal addition of a short peptide. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1808–1816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505581200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo and Yankner, 1994.Lorenzo A, Yankner BA. Beta-amyloid neurotoxicity requires fibril formation and is inhibited by Congo red. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12243–12247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, 2001.Luo Y. Ginkgo biloba neuroprotection: therapeutic implications in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2001;3:401–407. doi: 10.3233/jad-2001-3407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo et al., 2002.Luo Y, Smith JV, Paramasivam V, Burdick A, Curry KJ, Buford JP, Khan I, Netzer WJ, Xu H, Butko P. Inhibition of amyloid-beta aggregation and caspase-3 activation by the Ginkgo biloba extract EGb761. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12197–12202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182425199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maezawa et al., 2006.Maezawa I, Hong HS, Wu HC, Battina SK, Rana S, Iwamoto T, Radke GA, Pettersson E, Martin GM, Hua DH, Jin LW. A novel tricyclic pyrone compound ameliorates cell death associated with intracellular amyloid-beta oligomeric complexes. J Neurochem. 2006;98:57–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura et al., 2005.Matsuura T, Sato T, Shingai R. Interactions between Caenorhabditis elegans individuals during chemotactic response. Zoolog Sci. 2005;22:1095–1103. doi: 10.2108/zsj.22.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza et al., 2006.Mazza M, Capuano A, Bria P, Mazza S. Ginkgo biloba and donepezil: a comparison in the treatment of Alzheimer's dementia in a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:981–985. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mix and Crews Jr, 2002.Mix JA, Crews WD., Jr A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761(R) in a sample of cognitively intact older adults: neuropsychological findings. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2002;17:267–277. doi: 10.1002/hup.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi, 1967.Nakanishi K. The ginkgolides. Pure Appl Chem. 1967;14:89–113. doi: 10.1351/pac196714010089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi, 2005.Nakanishi K. Terpene trilactones from Gingko biloba: from ancient times to the 21st century. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:4987–5000. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttley et al., 2002.Nuttley WM, Atkinson-Leadbeater KP, Van Der Kooy D. Serotonin mediates food-odor associative learning in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12449–12454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192101699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo et al., 2006.Oddo S, Caccamo A, Tran L, Lambert MP, Glabe CG, Klein WL, LaFerla FM. Temporal profile of amyloid-beta (Abeta) oligomerization in an in vivo model of Alzheimer disease. A link between Abeta and tau pathology. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1599–1604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono and Yamada, 2006.Ono K, Yamada M. Antioxidant compounds have potent anti-fibrillogenic and fibril-destabilizing effects for alpha-synuclein fibrils in vitro. J Neurochem. 2006;97:105–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike et al., 1995.Pike CJ, Walencewicz-Wasserman AJ, Kosmoski J, Cribbs DH, Glabe CG, Cotman CW. Structure-activity analyses of beta-amyloid peptides: contributions of the beta 25–35 region to aggregation and neurotoxicity. J Neurochem. 1995;64:253–265. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64010253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan et al., 2000.Ranganathan R, Cannon SC, Horvitz HR. MOD-1 is a serotonin-gated chloride channel that modulates locomotory behaviour in C. elegans . Nature. 2000;408:470–475. doi: 10.1038/35044083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan et al., 2001.Ranganathan R, Sawin ER, Trent C, Horvitz HR. Mutations in the Caenorhabditis elegans serotonin reuptake transporter MOD-5 reveal serotonin-dependent and -independent activities of fluoxetine. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5871–5884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-05871.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli et al., 2005.Roselli F, Tirard M, Lu J, Hutzler P, Lamberti P, Livrea P, Morabito M, Almeida OF. Soluble beta-amyloid1–40 induces NMDA-dependent degradation of postsynaptic density-95 at glutamatergic synapses. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11061–11070. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3034-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawin et al., 2000.Sawin ER, Ranganathan R, Horvitz HR. C. elegans locomotory rate is modulated by the environment through a dopaminergic pathway and by experience through a serotonergic pathway. Neuron. 2000;26:619–631. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer and Kenyon, 1995.Schafer WR, Kenyon CJ. A calcium-channel homologue required for adaptation to dopamine and serotonin in Caenorhabditis elegans . Nature. 1995;375:73–78. doi: 10.1038/375073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer et al., 1996.Schafer WR, Sanchez BM, Kenyon CJ. Genes affecting sensitivity to serotonin in Caenorhabditis elegans . Genetics. 1996;143:1219–1230. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.3.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith and Luo, 2003.Smith JV, Luo Y. Elevation of oxidative free radicals in Alzheimer's disease models can be attenuated by Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761. J Alzheimers Dis. 2003;5:287–300. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith et al., 1996.Smith PF, Maclennan K, Darlington CL. The neuroprotective properties of the Ginkgo biloba leaf: a review of the possible relationship to platelet-activating factor (PAF) J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;50:131–139. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(96)01379-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stackman et al., 2003.Stackman RW, Eckenstein F, Frei B, Kulhanek D, Nowlin J, Quinn JF. Prevention of age-related spatial memory deficits in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease by chronic Ginkgo biloba treatment. Exp Neurol. 2003;184:510–520. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00399-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strayer et al., 2003.Strayer A, Wu Z, Christen Y, Link CD, Luo Y. Expression of the small heat-shock protein Hsp16-2 in Caenorhabditis elegans is suppressed by Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761. FASEB J. 2003;17:2305–2307. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0376fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanc et al., 2004.Urbanc B, Cruz L, Yun S, Buldyrev SV, Bitan G, Teplow DB, Stanley HE. In silico study of amyloid {beta}-protein folding and oligomerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:17345–17350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408153101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogensen et al., 2003.Vogensen SB, Stromgaard K, Shindou H, Jaracz S, Suehiro M, Ishii S, Shimizu T, Nakanishi K. Preparation of 7-substituted ginkgolide derivatives: potent platelet activating factor (PAF) receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 2003;46:601–608. doi: 10.1021/jm0203985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh and Selkoe, 2004.Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. Oligomers on the brain: the emerging role of soluble protein aggregates in neurodegeneration. Protein Pept Lett. 2004;11:213–228. doi: 10.2174/0929866043407174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh et al., 2005.Walsh DM, Townsend M, Podlisny MB, Shankar GM, Fadeeva JV, Agnaf OE, Hartley DM, Selkoe DJ. Certain inhibitors of synthetic amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) fibrillogenesis block oligomerization of natural Aβ and thereby rescue long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2455–2462. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4391-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe et al., 2001.Watanabe CM, Wolffram S, Ader P, Rimbach G, Packer L, Maguire JJ, Schultz PG, Gohil K. The in vivo neuromodulatory effects of the herbal medicine Ginkgo biloba . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6577–6580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111126298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, 1988.Wood W. The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wu and Luo, 2005.Wu Y, Luo Y. Transgenic C. elegans as a model in Alzheimer's research. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2005;2:37–45. doi: 10.2174/1567205052772768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang et al., 2005.Yang F, Lim GP, Begum AN, Ubeda OJ, Simmons MR, Ambegaokar SS, Chen PP, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Frautschy SA, Cole GM. Curcumin inhibits formation of amyloid beta oligomers and fibrils, binds plaques, and reduces amyloid in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5892–5901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao et al., 2001.Yao Z, Drieu K, Papadopoulos V. The Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761 rescues the PC12 neuronal cells from beta-amyloid-induced cell death by inhibiting the formation of beta-amyloid-derived diffusible neurotoxic ligands. Brain Res. 2001;889:181–190. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandi et al., 2004.Zandi PP, Anthony JC, Khachaturian AS, Stone SV, Gustafson D, Tschanz JT, Norton MC, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Breitner JC. Reduced risk of Alzheimer disease in users of antioxidant vitamin supplements: the Cache County Study. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:82–88. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al., 2005.Zhang Y, Lu H, Bargmann CI. Pathogenic bacteria induce aversive olfactory learning in Caenorhabditis elegans . Nature. 2005;438:179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature04216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]