Abstract

Exocytosis can be directly measured in mammalian brain slices by fluorescence detection of vesicular zinc release. Detection of the low-level evoked zinc signal [Zn]t was first demonstrated at the zinc-rich hippocampal mossy fiber pathway and required the use of high-frequency presynaptic stimulation. Here, we show that release after individual action potentials can be reliably detected even at non-mossy fiber, zinc-poor synapses in the hippocampus, a major enhancement in the temporal resolution of the technique. Short-term facilitation of release properties of zinc-positive CA3–CA1 Schaffer collateral/commissural synapses in the stratum radiatum differ from those at mossy fibers but are similar to those measured for the EPSP [field EPSP (fEPSP)]. The N-type Ca2+ channel toxin ω-conotoxin GVIA inhibited both the [Zn]t and fEPSP equally, and the modulation of neurotransmitter release by neuropeptide Y, baclofen, and adenosine as revealed by [Zn]t closely resembles that measured for the fEPSP. A long-standing controversy in hippocampal synaptic plasticity involves the site of long-term depression (LTD) at these synapses. Using zinc release as a direct marker for exocytotic events and a surrogate marker for glutamate release, we demonstrate that persistent depression of presynaptic release occurs in the late expression of DHPG [(S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine]-induced LTD at this synapse. The ability to examine release dynamics with zinc fluorescence detection will facilitate exploration of the molecular pharmacology and plasticity of exocytosis at many CNS synapses.

Keywords: vesicular zinc release, FluoZin-3, plasticity, LTD, DHPG, hippocampus

Introduction

Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) play a critical role in synaptic plasticity in the CNS (Fagni et al., 2000). In the hippocampal Schaffer collateral/commissural pathway, long-lasting depression of synaptic transmission [long-term depression (LTD)] can be induced by activating mGluRs at a low frequency with synaptically released glutamate (Bolshakov and Siegelbaum, 1994; Oliet et al., 1997) or with exogenously applied (S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG), an agonist of mGluRs. Although the induction of mGluR-LTD is widely thought to be postsynaptic, a definitive site for LTD expression has not been confirmed. Evidence for internalization or redistribution of ionotropic glutamate receptors and a requirement for postsynaptic protein synthesis in cultured neurons after application of DHPG supports a postsynaptic mechanism underlying mGluR-LTD (Snyder et al., 2001; Xiao et al., 2001); however, more recent evidence, including altered paired-pulse facilitation (PPF), decreased miniature EPSC (mEPSC) frequency, and the absence of a change in postsynaptic AMPA receptor sensitivity by DHPG all favor presynaptic expression of DHPG-LTD (Fitzjohn et al., 2001; Faas et al., 2002; Rammes et al., 2003; Rouach and Nicoll, 2003; Nosyreva and Huber, 2005). Recently, a developmental switch in the mechanism of mGluR-LTD expression has been proposed, based on evidence that mGluR-LTD at neonatal synapses is mediated by presynaptic mechanisms, whereas mGluR-LTD at mature synapses may result from postsynaptic modifications (Nosyreva and Huber, 2005). Although DHPG is widely used to study mGluR-LTD and DHPG-LTD shares many features with synaptically induced mGluR-LTD, there are some unusual properties of DHPG-LTD. The DHPG-LTD expression requires sustained activation of mGluR (Watabe et al., 2002; Rouach and Nicoll, 2003; Huang and Hsu, 2006) and the induction of DHPG-LTD is independent of postsynaptic Ca2+ entry (Fitzjohn et al., 2001).

The ability to directly examine presynaptic neurotransmitter release rather than inferring changes in evoked quantal output by analysis of postsynaptic responses can provide critical information in localizing the site of plasticity at synapses. We recently introduced such a method based on fluorescence detection of vesicular zinc by an extracellular zinc indicator dye (Qian and Noebels, 2005). Zinc has been shown to coexist with glutamate within synaptic vesicles in glutamatergic synapses in the many parts of brain including the hippocampus (Frederickson et al., 2000). Fluorescence detection of exocytosis by monitoring evoked vesicular zinc signals provides a novel way to assess neurotransmitter release at the zinc-containing hippocampal mossy fiber synapse (Qian and Noebels, 2005).

In the present study, we adapted the techniques developed for the mossy fiber synapse to measure vesicular zinc release evoked by individual action potentials at CA3–CA1 synapses within the hippocampal stratum radiatum. Zinc histochemistry detects a low level of vesicular zinc-containing terminals within this region. Recent analysis reveals that these synapses can be divided into two populations, those containing vesicular zinc and those without (Sindreu et al., 2003). The release properties of these populations have never been selectively characterized. We now demonstrate that fluorescence detection of zinc release can selectively resolve neurotransmitter release dynamics in the Schaffer collateral/commissural pathway, and apply this direct measure to examine DHPG-LTD at CA3–CA1 synapses. Our experimental results demonstrate a persistent depression of neurotransmitter release during DHPG-LTD at the zinc-containing mouse hippocampal CA3–CA1 synapse.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of brain slices.

All procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health, as approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Baylor College of Medicine. Transverse brain slices [200–250 μm thickness: 200 μm, optical recording; 250 μm, extracellular recording of field EPSP (fEPSP)] were prepared from hippocampi of wild-type (C57BL/6J) and Znt3−/− (C57BL/6 × 129/SvEv) mice. For the adult mouse group, the animal age ranges between 6 and 10 weeks. For the young mouse group in the LTD experiments, the animal age is between 15 and 18 d. Znt3−/− mutant mice were generously provided by R. D. Palmiter (University of Washington, Seattle, WA). Brain slices were incubated in artificial CSF (ACSF) at 32°C for 1 h and then transferred into a submerged recording chamber mounted on an inverted microscope (Axiovert 100; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The ACSF contained the following (in mm): 119 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 2 MgSO4, 1 NaH2PO4, 11 d-glucose, 0.2 Ca-EDTA gassed with 95% O2/5% CO2 to maintain a constant pH of 7.4. The temperature of the recording chamber was controlled at 30°C.

Zinc fluorescence detection in stratum radiatum of the CA1 region.

A bipolar tungsten electrode was positioned in the stratum radiatum to stimulate the CA3–CA1 synapse. The stimulation pulse intensity was adjusted to 20 μA/0.1 ms to evoke a submaximal response for optical recording and to 10 μA/0.1 ms for extracellular recording of the fEPSP. A train of five pulses at 5 Hz was used to evoke the transient zinc fluorescence signal (ΔF or [Zn]t) and fEPSP in most experiments. The zinc-sensitive indicator FluoZin-3 was present in the extracellular solution at a concentration of 2 μm for fluorescence recordings. The slow zinc chelator Ca-EDTA (0.2 mm) was routinely included in all experiments to reduce basal zinc fluorescence. The glutamate receptor antagonists CNQX and d-APV were also present in the perfusate during zinc measurement to eliminate the interference of autofluorescence. A small recording area (150 μm in diameter) in the stratum radiatum of the CA1 region located ∼400 μm away from the stimulation electrode was excited at a wavelength of 488/20 nm; the emitted fluorescence was filtered by a bandpass filter of 535/25 nm and converted into electrical signals with a single photodiode. Because the zinc signal was obtained after abolishing the fEPSP, a separate set of slices was used to monitor glutamate release by field recording. Sharp glass recording electrodes (filled with 2 m NaCl) were positioned at the same distance from the stimulation electrode as for optical recording. Signals were filtered through low-pass filters with a corner frequency of 5 kHz and sampled at 10 kHz. Sample traces shown are an average of 5–10 successive traces during steady state to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. The initial slope of the fEPSP is taken as the measure of synaptic transmission. Because of a possible accumulation of extracellular zinc, basal FluoZin-3 fluorescence (F) recorded from the slice increased slowly, although the stimulus-evoked ΔF remained stable. Therefore, ΔF was measured to represent amount of transmitter release and ΔF had to be stable for at least 20 min before a manipulation was made. The short-term bleaching course of FluoZin-3 was corrected by linear extrapolation (see Fig. 1) instead of measuring actual dye bleaching time course as shown in our previous study (Qian and Noebels, 2005). Although this method of correction for bleaching is not perfect, it did not significantly affect the measurement of each individual ΔF. More importantly, it reduced the amount of light exposure by 50%, and ensured a stable ΔF over the 1.5 h period that is critical for LTD experiments. The fluorescence intensity in all figures was plotted in the arbitrary unit of photodiode output. Data in each experiment were normalized to the baseline before drug application, and then pooled and expressed as a mean ± SD.

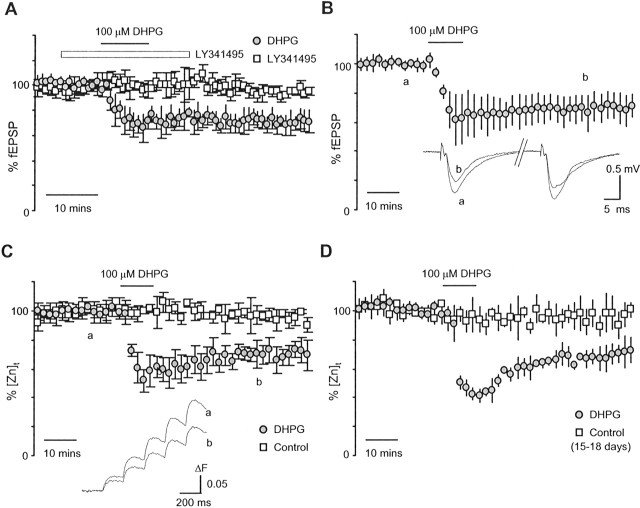

Figure 1.

Vesicular zinc release evoked by individual action potentials at the CA3–CA1 synapse. A, Schematic diagram of a hippocampal slice showing stimulating and recording sites. DG, Dentate gyrus. Inset, Sample traces of autofluorescence and fluorescence signal of FluZin-3 in response to 5 Hz stimulation. a, FluoZin-3 fluorescence trace before correction for photobleaching. b, Autofluorescence in the presence of the glutamate receptor antagonist CNQX/d-APV and FluoZin-3 fluorescence after correction of photobleaching. The time course of the photobleaching was corrected by linear extrapolation of the time course before stimulation. B, Left, Time course of the fluorescence intensity (F) and the peak amplitude of the transient fluorescence change (ΔF or [Zn]t) in response to application of CNQX/d-APV and FluoZin-3 in wild-type mice (n = 24). Blockade of postsynaptic depolarization with CNQX/d-APV eliminated the autofluorescence transient but not the FluoZin-3 signal. Right, Time course of the fluorescence intensity F and the peak amplitude of ΔF in response to application of CNQX/d-APV and FluoZin-3 in vesicular zinc transporter-deficient mice (Znt3−/−; n = 5). Lack of FluoZin-3 signal in Znt3−/− mice indicates that [Zn]t resulted from the interaction between vesicular zinc and FluoZin-3 after exocytosis of synaptic vesicles. Error bars present SD in all figures.

Pharmacological reagents.

The zinc indicator FluoZin-3 was obtained from Invitrogen (San Diego, CA). DHPG, (2S)-2-amino-2-[(1S,2S)-2-carboxycycloprop-1-yl]-3(xanth-9-yl)propanoic acid (LY341495), CNQX, and d-APV were purchased from Tocris (Ellisville, MO). Adenosine and baclofen were from RBI (Natick, MA). Neuropeptide Y (NPY3–36, rat) and ω-conotoxin GVIA (ω-CgTX GVIA) were from Bachem (Torrance, CA). All other chemical reagents were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Results

Detection of evoked vesicular zinc release by individual action potentials in the stratum radiatum of the hippocampal CA1 region

Figure 1A is a schematic diagram detailing the measurement of extracellular zinc accumulation ([Zn]o) evoked by stimulating the CA3–CA1 synapse in the stratum radiatum of the hippocampal CA1 region of mouse brain slices. The top inset (Fig. 1Aa) shows the fluorescence response of the high affinity zinc indicator FluoZin-3 ([Zn]t) evoked by a stimulation protocol consisting of five pulses at 5 Hz. Over the sampling period of 2.5 s, ∼1% of the signal diminished because of photobleaching of the zinc indicator. To obtain a more accurate time course of the [Zn]t decay, dye bleaching was corrected by linear extrapolation of the baseline before stimulation as shown by the dashed line. The bottom inset (Fig. 1Ab) shows sample traces of autofluorescence, autofluorescence in the presence of CNQX/d-APV, and the fluorescence response of FluoZin-3 after correction for photobleaching. Because there was a significant amount of postsynaptic activity-dependent change of autofluorescence in the CA1 region, the glutamate receptor antagonists CNQX (10 μm) and d-APV (25 μm) were routinely added to the perfusate to eliminate the interference of autofluorescence in all zinc measurements. Figure 1B summarizes the experimental results from wild-type (+/+) and vesicular zinc transporter Znt3-deficient mutant mice (Znt3−/−). As demonstrated here, CNQX and d-APV abolished the autofluorescence transient but not the [Zn]t. The average peak amplitude of the [Zn]t was 2.1 ± 0.5% (ΔF/F) in wild-type mice (n = 24). However, no [Zn]t was observed in slices from Znt3−/− mice (n = 5). These data confirm that the [Zn]t is a result of the interaction between vesicular zinc and FluoZin-3 after action potential-induced exocytosis of synaptic vesicles. The absence of an evoked FluoZin-3 signal in Znt3−/− mice also excludes the possibility of irrelevant artifacts such as light scattering contributing to the FluoZin-3 signal.

Zinc release and glutamate release share the same short-term facilitation and Ca2+ channel reliance at the CA3–CA1 synapse

Vesicular zinc coreleased with glutamate has been demonstrated to serve as a surrogate marker for presynaptic neurotransmitter release at the intensely zinc-rich hippocampal mossy fiber synapse (Qian and Noebels, 2005). In contrast to the mossy fiber synapse, where zinc coexists with glutamate in synaptic vesicles within every mossy fiber bouton, only ∼45% of the boutons making axospinous glutamatergic synaptic contacts in the stratum radiatum of the CA1 region are zinc containing (Sindreu et al., 2003). We reasoned, however, that if zinc-positive synapses possess similar release properties as zinc-negative synapses in this pathway (see below), then [Zn]t measured at the zinc-positive synapses could be used as surrogate marker to represent neurotransmitter release at all CA3–CA1 synapses. Therefore, in the following experiments, we characterized zinc release at the zinc-positive synapse and compared it with fEPSPs obtained from the entire CA3–CA1 population.

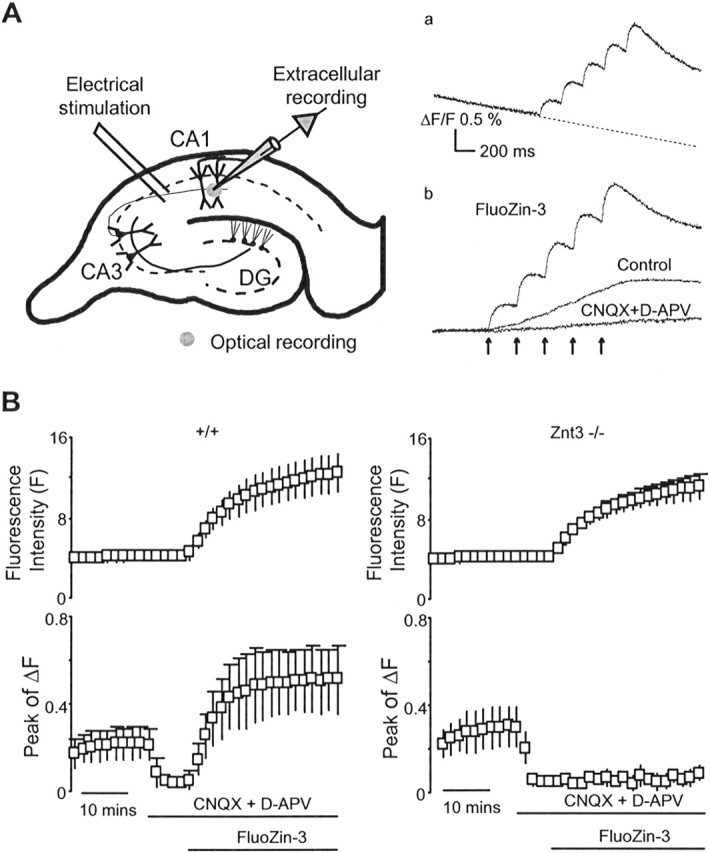

Figure 2A summarizes the short-term facilitation of zinc release and of glutamate release. In contrast to a robust short-term facilitation of the [Zn]t at mossy fiber synapses (Qian and Noebels, 2005), the CA3–CA1 synapses here exhibited only moderate short-term facilitation, and the pattern of short-term facilitation of the [Zn]t was essentially similar to that measured for the fEPSP. As summarized in Figure 2A, the amplitudes of the [Zn]t corresponding to the first through fifth action potentials were 72 ± 5, 97 ± 3, 104 ± 2, 111 ± 3, and 116 ± 4% of the mean value of all five [Zn]t (n = 26), respectively. The fEPSPs corresponding to the first through fifth action potentials were 74 ± 9, 99 ± 5, 105 ± 5, 111 ± 7, and 110 ± 6% of the average of all five fEPSPs (n = 27), respectively.

Figure 2.

Short-term facilitation and Ca2+ channel reliance of zinc release are similar to glutamate release. A, Left, Superimposed fEPSPs evoked by the 5 Hz stimulation protocol. Right, Summary data of short-term facilitation of zinc release and glutamate release. Zinc release exhibits the same pattern of short-term facilitation as glutamate release. To quantify ΔF for each action potential, 10 traces of the [Zn]t during steady state were first averaged and then smoothed with an average time window of 10 ms, and then the ΔF corresponding to each action potential (AP) was measured. The smoothing algorithm does not alter the kinetics of the [Zn]t. B, C, The N-type Ca2+ channel blocker ω-CgTX GVIA equally inhibited the [Zn]t and fEPSP. The time course of the [Zn]t was quantified by measuring the total ΔF evoked by a 5 Hz stimulation protocol. To be better compared with the time course of the [Zn]t, a summation of all five fEPSPs within the stimulation train was quantified as the time course of fEPSP. Insets show sample traces of the [Zn]t (smoothed), first and fifth fEPSP before and after application of ω-CgTx GVIA.

To determine the Ca2+ channel subtype reliance of zinc release at these synapses, we then examined the effect of the N-type Ca2+ channel blocker ω-CgTx GVIA on the [Zn]t. Figure 2B shows the grouped time course of the [Zn]t in response to application of 1 μm ω-CgTx GVIA. The N-type Ca2+ channel blocker partially reduced the [Zn]t as shown by the time course of the [Zn]t and the sample traces taken during steady state. Figure 2C shows typical results of ω-CgTX GVIA on the fEPSP at the CA3–CA1 synapses. Blockade of N-type channels resulted in an equal reduction of both the [Zn]t and fEPSP. On average, the ΔFs corresponding to the first and fifth action potentials were reduced to 47 ± 6 and 48 ± 5% of baseline (n = 5), respectively. The corresponding fEPSPs were 48 ± 6 and 53 ± 7% of baseline (n = 5). We did not examine the contribution of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels on the [Zn]t, because blockade of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels, which contribute predominantly to the remainder of the presynaptic Ca2+ required for exocytosis at this synapse (Wheeler et al., 1994), should yield a similar result on the [Zn]t and fEPSP (see Discussion).

Zinc release and glutamate release are modulated identically at CA3–CA1 synapses

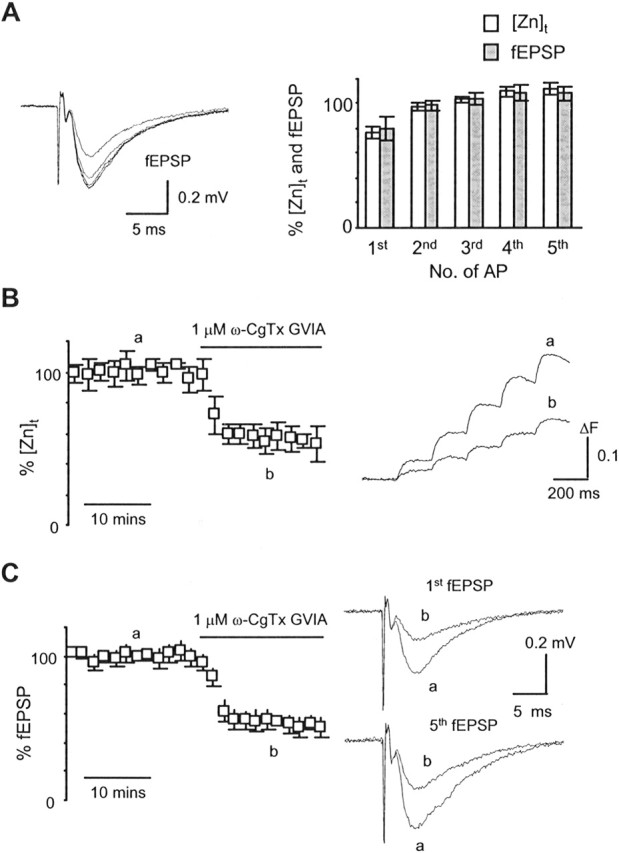

Next, we characterized the modulation of zinc release and compared it with that measured for the fEPSP. Neurotransmitter release at CA3–CA1 synapses is regulated by presynaptic receptors for NPY, GABAB, and adenosine acting via presynaptic Ca2+ channels (Qian et al., 1997; Wu and Saggau, 1997). Figure 3, A and B, shows the effect of NPY on the [Zn]t and fEPSP. Application of 1 μm NPY led to a similar effect on both [Zn]t and fEPSP. NPY inhibited the [Zn]t by 78 ± 1 and 79 ± 1% (n = 4) for the first and fifth action potentials, respectively. The average reduction of the corresponding fEPSPs was 80 ± 4 and 78 ± 1% (n = 4). Similarly, activation of presynaptic GABAB and adenosine receptors resulted in the same amount of inhibition of both the [Zn]t and fEPSP. As shown in Figure 3, C and D, baclofen (10 μm), the GABAB receptor agonist, reduced the [Zn]t by 71 ± 4 and 70 ± 5% (n = 4) for the first and fifth action potentials, respectively. The mean reduction of the corresponding fEPSPs was 76 ± 4 and 68 ± 4% (n = 4). Not surprisingly, application of 5 μm adenosine also reversibly inhibited the [Zn]t and fEPSPs to a similar extent (Fig. 3E,F). The [Zn]t during the peak effect of adenosine was 54 ± 11 and 51 ± 8% (n = 4) of baseline for the first and fifth action potentials, respectively, and the corresponding fEPSPs were 50 ± 7 and 53 ± 8% (n = 4) of baseline. These results, combined with similar short-term facilitation and Ca2+ channel reliance of neurotransmitter release, indicate that the same release machinery and regulatory mechanisms are operative at both zinc-positive and zinc-negative synapses. Therefore, [Zn]t at zinc-positive synapses in the CA1 region is a valid surrogate marker to directly access global neurotransmitter release at the CA3–CA1 synapse.

Figure 3.

Identical modulation of zinc release and glutamate release. A–F, Modulation of zinc and glutamate release by NPY, baclofen, and adenosine. The time course of the [Zn]t and fEPSP as well as ΔF for each action potential were quantified as described in Figure 2. Insets show sample traces of the [Zn]t (smoothed) and fEPSP taken at time points as marked. G, Summary data for the effects of NPY, baclofen, and adenosine on the [Zn]t and fEPSP. The identical patterns of modulation, short-term facilitation, and Ca2+ channel reliance of zinc release and glutamate release confirm that the [Zn]t is a valid surrogate marker for presynaptic neurotransmitter release at the CA3–CA1 synapse. AP, Action potential.

Persistent depression of neurotransmitter release after activation of mGluR

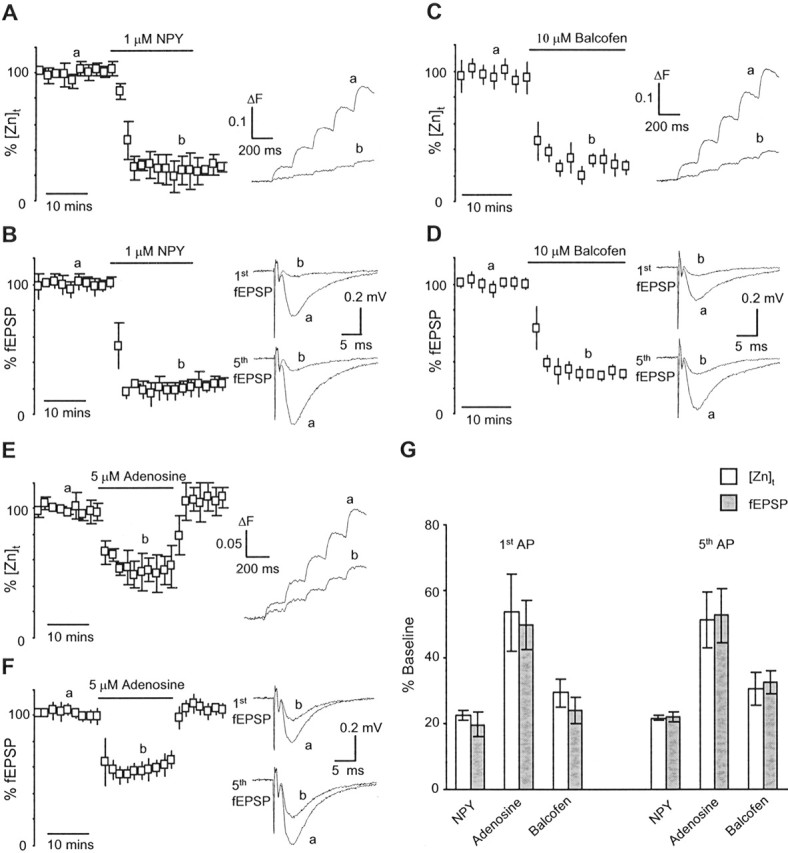

Using fluorescence detection of zinc release, we then explored the expression site of mGluR-LTD with the mGluR agonist DHPG at this synapse. To compare results with previous studies, a test protocol consisting of paired pulses with an interval of 50 ms was first used to test DHPG-LTD at the CA3–CA1 synapse. In agreement with previous reports, a 10 min application of 100 μm DHPG led to persistent depression of synaptic transmission at the CA3–CA1 synapse (n = 5) as shown in Figure 4A. The action of DHPG was completely blocked with the broad mGluR antagonist LY341495 (20 μm; n = 3), indicating the requirement for mGluR activation in DHPG-LTD. DHPG-LTD was independent of the protocols used for testing. As shown in Figure 4B, a short application of DHPG in slices receiving the same stimulation protocol used in optical recordings induced an equivalent amount of LTD. d-APV (25 μm) was routinely applied in this set of LTD experiments to eliminate a possible contribution from NMDA receptor-medicated LTD. The average fEPSP 40 min after DHPG application was 67 ± 11 and 72 ± 9% of baseline for first and fifth fEPSP, respectively (n = 10).

Figure 4.

Persistent depression of neurotransmitter release after mGluR activation. A, Time course of fEPSPs evoked by a pair of stimuli separated by an interval of 50 ms after a 10 min application of 100 μm DHPG. The brief application of DHPG led to a persistent depression of synaptic transmission (n = 5) that was blocked by the nonspecific mGluR antagonist LY341495 (n = 3). B, Time course of summation of fEPSPs evoked by 5 Hz stimulation protocol in response to the brief application of DHPG. The first and fifth fEPSPs were 67 ± 11 and 72 ± 9% (n = 10) of baseline and were obtained 40 min after washout of the DHPG. C, Time course of the [Zn]t in response to DHPG in adult mouse hippocampus (6–10 weeks). After DHPG application, there was a persistent depression of the [Zn]t. The first and fifth ΔF values were 70 ± 7 and 69 ± 7% (n = 5) of baseline when measured 40 min after washout of DHPG. The diminished [Zn]t was not attributable to depletion of vesicular zinc, because the [Zn]t remained at a stable level during the entire experimental period in the control group (n = 4). The persistent depression of the [Zn]t clearly indicates a presynaptic expression of DHPG-LTD. D, Time course of the [Zn]t in response to DHPG in developing brain (15–18 d). In slices from immature hippocampus, DHPG induced a greater initial depression of neurotransmitter release than in the adult group (C). However, the persistent depression of neurotransmitter release during DHPG-LTD was nearly identical in the two age groups. The first and fifth ΔF values were 67 ± 7 and 66 ± 3% (n = 5) of baseline when measured 40 min after washout of DHPG.

We then examined presynaptic neurotransmitter release during DHPG-LTD by measuring the [Zn]t in response to DHPG. As shown in Figure 4C, after an initial decrease, the [Zn]t only partially recovered 40 min after washout of DHPG and exhibited a pattern of long-term depression. The first and fifth [Zn]t were 70 ± 7 and 69 ± 7% of baseline, respectively (n = 5). The persistent reduction of the [Zn]t was not attributable to a possible deletion of vesicular zinc, because the [Zn]t in control experiments remained at a stable level throughout the entire measurement. The first and fifth [Zn]t were 97 ± 2 and 95 ± 3% (n = 4) of baseline by the end of the experiments. Our results here clearly indicate a presynaptic expression of LTD after activation of mGluR at the CA3–CA1 synapse.

Recently, a developmental switch in the mechanism of mGluR-LTD expression has been proposed, based on evidence that mGluR-LTD at neonatal synapses is mediated by presynaptic mechanisms, whereas mGluR-LTD at mature synapses may arise from postsynaptic modifications (Nosyreva and Huber, 2005). To learn whether presynaptic mechanisms of DHPG-LTD fade during brain maturation, we examined DHPG-LTD in developing mouse hippocampus. Figure 4D summarizes the results from a group of young mice aged between 15 and 18 d. When compared with the adult group (Fig. 4C), DHPG induced a greater initial depression of neurotransmitter release in immature slices. However, the amplitude of the later phase of DHPG-LTD was similar between the two age groups. On average, the first and fifth [Zn]t responses measured 40 min after DHPG application were 67 ± 7 and 66 ± 3% of baseline, respectively (n = 5). The corresponding [Zn]t responses in the same age control group were 93 ± 6 and 95 ± 7% of baseline, respectively (n = 5). These results indicate that the same presynaptic mechanism controls expression of DHPG-LTD in both developing and mature mouse brain.

Discussion

The ability to detect excytosis at zinc-containing synapses provides a novel method to analyze plasticity of the release process in hippocampal slices. Refinements in the method allow exploration of release dynamics in non-mossy fiber terminals, and here we have used the zinc fluorescence detection technique to explore the site of persistent depression of synaptic transmission at CA3–CA1 synapses after activation of mGluR with DHPG. Our results are congruent with previous conclusions based on electrophysiological and vesicle dye loading methods of the presynaptic site for LTD expression at CA3–CA1 synapses, and reveal additional properties of this heterogeneous presynaptic terminal population.

Release properties of zinc-containing synapses at the CA3–CA1 synapses

In contrast to the mossy fiber pathway, where zinc coexists with glutamate in synaptic vesicles within every mossy fiber bouton, only about one-half of the CA3–CA1 synapses in the stratum radiatum are zinc/Znt3 positive (Sindreu et al., 2003). This raises several key questions. First, where are the parent neurons of zinc containing synapses in this region? The vesicular zinc transporter gene Znt3 is strongly expressed in CA3 pyramidal neurons (Palmiter et al., 1996), consistent with its presence in fiber terminals in the Schaffer collateral pathway. The origin of zinc-negative synapses, however, is less clear, and these terminals may represent a functional subgroup of neurons residing in CA3 or elsewhere (Sindreu et al., 2003). Second, do the zinc-positive synapses in this lamina possess different release properties and plasticity compared with zinc-negative synapses? Using only conventional electrophysiological recording techniques, it is impossible to separate the zinc-positive synaptic component of the fEPSP from the one that is zinc negative; however, fluorescence detection of zinc release provides a direct way to selectively assess exocytosis at the zinc-positive subpopulation. In this study, we find that neurotransmitter release at zinc-containing synapses relies on the same presynaptic Ca2+ channel subtype ratio as zinc-negative synapses. As shown in Figure 2, inhibition of the [Zn]t by the N-type Ca2+ blocker ω-CgTx GVIA was identical to that measured electrophysiologically for the global fEPSP, implying a similar degree of N-type channel contribution to neurotransmitter release at both zinc-positive and zinc-negative synapses. In addition, presynaptic N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels are sensitive to various neuromodulators (Qian et al., 1997; Wu and Saggau, 1997). As shown in Figure 3, modulation of the [Zn]t at zinc-positive synapses by NPY, baclofen, and adenosine was indistinguishable from that measured electrophysiologically from the whole population (fEPSP). Because N-type Ca2+ channels are equally involved in release at both synapses, the similarity in modulation profile also implies that the contribution of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels to neurotransmitter release at the zinc-positive synapses is equivalent to that at zinc-negative synapses. Moreover, similar short-term facilitation of the [Zn]t and fEPSP (Fig. 2A) is consistent with the involvement of the same sets of presynaptic Ca2+ channels in the release process at both types of synapses. Together, our experimental results indicate that similar mechanisms control neurotransmitter release at both zinc-positive and zinc-negative glutamatergic synapses in the Schaffer collateral/commissural pathway.

Presynaptic expression of DHPG-LTD at the mouse CA3–CA1 synapse

Contrasting results have been obtained in previous studies for the expression site of mGluR-LTD at the CA3–CA1 synapse. The presynaptic expression of mGluR-LTD is supported by evidence of altered PPF or decreased mEPSC frequency during synaptically induced mGluR-LTD or DHPG-LTD (Oliet et al., 1997; Fitzjohn et al., 2001; Faas et al., 2002; Rouach and Nicoll, 2003; Nosyreva and Huber, 2005). Although an increase in the PPF or a decrease in mEPSC frequency has been taken as an indication of reduced neurotransmitter release, the internalization of postsynaptic AMPA receptors could also lead to a similar apparent change in the PPF or mEPSC frequency. The reverse process has been found in LTP (Poncer and Malinow, 2001), and indeed, the internalization or redistribution of AMPA receptors after application of DHPG has been reported in cultured hippocampal neurons (Snyder et al., 2001; Xiao et al., 2001). In slice preparations, mixed results have been obtained. Initially, DHPG was found to reduce synaptic transmission without altering the postsynaptic membrane sensitivity of glutamate in hippocampal CA1 neurons during DHPG-LTD, favoring a presynaptic mechanism (Rammes et al., 2003). Recently, however, a quantitative study of AMPA receptor expression in hippocampal slices revealed a reduction of AMPA receptor surface expression after application of DHPG in adolescent rats (but not immature) brains (Nosyreva and Huber, 2005). Additional evidence has been obtained with another surrogate marker for release, the membrane-labeling dye FM 1-43, which was used to label synaptic vesicle membrane during the cycling of presynaptic vesicles to allow comparison of the extent of labeling before and after LTD induction (Zakharenko et al., 2002). They found a decrease in vesicle cycling after LTD induction, which was the first result that did not rely on postsynaptic membrane response properties to support the evidence for the presynaptic expression of mGluR-LTD. However, there is an inherent sampling limitation linked with this method. In that study, a single evaluation of the vesicle cycling process lasts 20 min and consists of 2 min, 10 Hz burst stimulation for dye staining and 4.5 min, 1.5 Hz stimulation for dye destaining. Therefore, the time course of changes in vesicle cycling after induction could not be repetitively quantified, and the release profile was based on a single assay. In contrast, the zinc fluorescence imaging technique used in our study allows constant monitoring of neurotransmitter release throughout the entire experimental time period. The persistent reduction of zinc release after application of DHPG we observed provides new and convincing evidence for a presynaptic expression of DHPG-LTD. Nevertheless, our results do not rule out a parallel postsynaptic mechanism that may also occur at release-silent synapses brought on by DHPG.

Mechanism of presynaptic depression

A general agreement has been reached that mGluR-LTD is initially induced postsynaptically (Bolshakov and Siegelbaum, 1994; Oliet et al., 1997; Watabe et al., 2002), thereby suggesting a retrograde signal mediating the presynaptic expression of mGluR-LTD. The molecule responsible for signaling a presynaptic change in release probability during the late phase of DHPG-LTD is still unidentified. Given the fact that postsynaptic AMPA and NMDA receptors were blocked with CNQX and d-APV to eliminate the interference of autofluorescence in our zinc measurement, the generation of such a retrograde messenger must be independent of a postsynaptic Ca2+ triggered signal contributed via Ca2+ entry through either NMDA receptors or voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. In the Fitzjohn et al. (2001) study, DHPG was shown to induce LTD in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. This result implies that postsynaptic Ca2+ entry via NMDA or voltage-dependent calcium channels is not required for DHPG-LTD, consistent with our conclusion. Because postsynaptic Ca2+ entry is required for synaptically induced mGluR-LTD (Bolshakov and Siegelbaum, 1994; Oliet et al., 1997; Otani and Connor, 1998), our result raises the possibility that DHPG-LTD may have a different mechanism. Because of the significant autofluorescence, it is not currently possible to precisely monitor zinc released by action potentials without blocking postsynaptic activity, and we were therefore unable to verify the presynaptic expression of mGluR-LTD induced solely by synaptic activity. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 4, C and D, we found that the persistent depression of neurotransmitter release after application of DHPG was nearly identical in developing and mature mouse brain. Therefore, we were unable to confirm a developmental switch of the mGluR-LTD mechanism as reported in adolescent rats (Nosyreva and Huber, 2005). It is unclear whether the discrepancy between these two studies might be attributable to the species difference of experimental animals.

Vesicular zinc exocytosis at non-mossy fiber terminals

Zinc, as an essential divalent metal in the brain, exists in various forms throughout many subcellular compartments of the CNS (Frederickson et al., 2005). Previous studies of vesicular zinc exocytosis at synapses have naturally focused on the zinc-rich mossy fiber pathway in the hippocampus (Thompson et al., 2000; Li et al., 2001; Ueno et al., 2002; Kay, 2003; Qian and Noebels, 2005). Little attention has been paid to neuronal circuits with weak histochemical vesicular zinc staining, although the widespread presence of mRNA for Znt3, the gene underlying zinc transport into synaptic vesicles suggests that many glutamate synapses other than the mossy fiber synapse may also have zinc available for release (Palmiter et al., 1996). Because of differences in dye concentration and stimulus strength required to resolve vesicular zinc exocytosis in the CA1 region, the amplitudes of ΔF/F are not directly comparable with those reported at mossy fiber synapses (Qian and Noebels, 2005). Our zinc signal neither reflects absolute levels of zinc, nor distinguishes between free zinc and the externalization of membrane-bound zinc in the synaptic cleft as discussed by Kay (2006). In summary, the enhanced ability to resolve exocytosis of vesicular zinc evoked by action potentials opens the exploration of presynaptic release dynamics at many other zinc-containing neuronal circuits in the CNS.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health–National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS29709.

References

- Bolshakov VY, Siegelbaum SA (1994). Postsynaptic induction and presynaptic expression of hippocampal long-term depression. Science 264:1148–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faas GC, Adwanikar H, Gereau RW, Saggau P (2002). Modulation of presynaptic calcium transients by metabotropic glutamate receptor activation: a differential role in acute depression of synaptic transmission and long-term depression. J Neurosci 22:6885–6890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagni L, Chavis P, Ango F, Bockaert J (2000). Complex interactions between mGluRs, intracellular Ca2+ stores and ion channels in neurons. Trends Neurosci 23:80–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzjohn SM, Palmer MJ, May JE, Neeson A, Morris SA, Collingridge GL (2001). A characterisation of long-term depression induced by metabotropic glutamate receptor activation in the rat hippocampus in vitro. J Physiol (Lond) 537:421–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson CJ, Suh SW, Silva D, Frederickson CJ, Thompson RB (2000). Importance of zinc in the central nervous system: the zinc-containing neuron. J Nutr 130:1471S–1483S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson CJ, Koh JY, Bush AI (2005). The neurobiology of zinc in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 6:449–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CC, Hsu KS (2006). Sustained activation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 and protein tyrosine phosphatases mediate the expression of (S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine-induced long-term depression in the hippocampal CA1 region. J Neurochem 96:179–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay AR (2003). Evidence for chelatable zinc in the extracellular space of the hippocampus, but little evidence for synaptic release of Zn. J Neurosci 23:6847–6855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay AR (2006). Imaging synaptic zinc: promises and perils. Trends Neurosci 29:200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Hough CJ, Suh SW, Sarvey JM, Frederickson CJ (2001). Rapid translocation of Zn2+ from presynaptic terminals into postsynaptic hippocampal neurons after physiological stimulation. J Neurophysiol 86:2597–2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosyreva ED, Huber KM (2005). Developmental switch in synaptic mechanisms of hippocampal metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent long-term depression. J Neurosci 25:2992–3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliet SH, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA (1997). Two distinct forms of long-term depression coexist in CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells. Neuron 18:969–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani S, Connor JA (1998). Requirement of rapid Ca2+ entry and synaptic activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors for the induction of long-term depression in adult rat hippocampus. J Physiol (Lond) 511:761–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmiter RD, Cole TB, Quaife CJ, Findley SD (1996). ZnT-3, a putative transporter of zinc into synaptic vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:14934–14939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poncer JC, Malinow R (2001). Postsynaptic conversion of silent synapses during LTP affects synaptic gain and transmission dynamics. Nat Neurosci 4:989–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J, Noebels JL (2005). Visualization of transmitter release with zinc fluorescence detection at the mouse hippocampal mossy fibre synapse. J Physiol (Lond) 566:747–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J, Colmers WF, Saggau P (1997). Inhibition of synaptic transmission by neuropeptide Y in rat hippocampal area CA1: modulation of presynaptic Ca2+ entry. J Neurosci 17:8169–8177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rammes G, Palmer M, Eder M, Dodt HU, Zieglgansberger W, Collingridge GL (2003). Activation of mGlu receptors induces LTD without affecting postsynaptic sensitivity of CA1 neurons in rat hippocampal slices. J Physiol (Lond) 546:455–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouach N, Nicoll RA (2003). Endocannabinoids contribute to short-term but not long-term mGluR-induced depression in the hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci 18:1017–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindreu CB, Varoqui H, Erickson JD, Perez-Clausell J (2003). Boutons containing vesicular zinc define a subpopulation of synapses with low AMPAR content in rat hippocampus. Cereb Cortex 13:823–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder EM, Philpot BD, Huber KM, Dong X, Fallon JR, Bear MF (2001). Internalization of ionotropic glutamate receptors in response to mGluR activation. Nat Neurosci 4:1079–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RB, Whetsell Jr WO, Maliwal BP, Fierke CA, Frederickson CJ (2000). Fluorescence microscopy of stimulated Zn(II) release from organotypic cultures of mammalian hippocampus using a carbonic anhydrase-based biosensor system. J Neurosci Methods 96:35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno S, Tsukamoto M, Hirano T, Kikuchi K, Yamada MK, Nishiyama N, Nagano T, Matsuki N, Ikegaya Y (2002). Mossy fiber Zn2+ spillover modulates heterosynaptic N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor activity in hippocampal CA3 circuits. J Cell Biol 158:215–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabe AM, Carlisle HJ, O'Dell TJ (2002). Postsynaptic induction and presynaptic expression of group 1 mGluR-dependent LTD in the hippocampal CA1 region. J Neurophysiol 87:1395–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DB, Randall A, Tsien RW (1994). Roles of N-type and Q-type Ca2+ channels in supporting hippocampal synaptic transmission. Science 264:107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LG, Saggau P (1997). Presynaptic inhibition of elicited neurotransmitter release. Trends Neurosci 20:204–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao MY, Zhou Q, Nicoll RA (2001). Metabotropic glutamate receptor activation causes a rapid redistribution of AMPA receptors. Neuropharmacology 41:664–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharenko SS, Zablow L, Siegelbaum SA (2002). Altered presynaptic vesicle release and cycling during mGluR-dependent LTD. Neuron 35:1099–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]