INTRODUCTION

Child sexual abuse (CSA) is associated with developing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as well as with other anxiety, mood, conduct, sexual, and substance abuse disorders. 1 Recent reviews of the literature have reported that Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT), a treatment approach that incorporates separate individual sessions for the child and the non-offending parent along with conjoint parent-child sessions is effective for treating PTSD in children. 2, 3 The trauma narrative (TN) component is a critical component of TF-CBT but therapists and parents may be hesitant to engage in detailed discussions about the trauma.4, 5 Exposure-based cognitive behavioral interventions are generally recommended for treating adults as well as youth with PTSD, 6, 3 However, there is limited evidence that the TN component is essential for treating younger children who have experienced CSA. 7, 8 It is also unclear how much treatment in general and exposure treatment in particular is optimal for young survivors of CSA.

The purpose of the present study was to examine the differential effects of TF-CBT with or without the TN component delivered in 8 vs. 16 sessions to young CSA survivors (4–11 years of age) and their non-offending parents. Specifically, the study was designed to ascertain whether the severity of the PTSD, internalizing, externalizing, depressive, and anxiety symptoms of the children along with their levels of sexualized behaviors, fear, shame, and body safety skills would be comparable across treatment conditions after completing treatment. In addition, the parents’ levels of depression, emotional distress about their children’s sexual abuse, and parenting practices were also compared.

METHOD

Sample

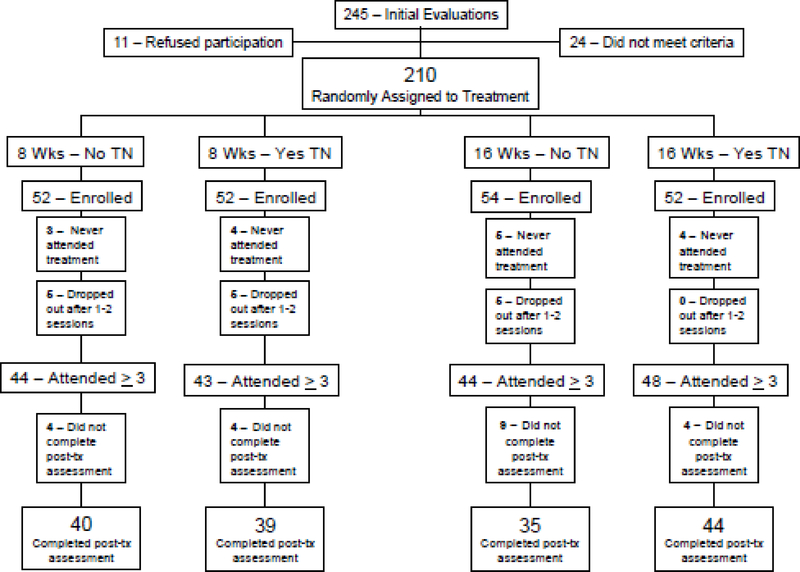

Figure 1 shows the number of children assessed at various stages of the study. Two hundred ten children, ages 4–11 years old, along with their 164 parents were randomly assigned to one of four treatment conditions: 8 sessions with no TN (8 No TN), 8 sessions with TN (8 Yes TN), 16 sessions with no TN (16 No TN), and 16 sessions with TN (16 Yes TN). The term “parent” describes any primary caregiver who accompanied, entered treatment, and provided the principal information about the child. The difference between the number of parents and children was attributable to 17 (8%) siblings being included in the study. Siblings were randomized to the same condition and the results did not differ as a function of sibling inclusion. The children were recruited from two sites (Pittsburgh, PA and Stratford, NJ).

Figure 1.

Flow chart. 8 wks=8 weekly sessions; 16 wks=16 weekly sessions; No TN=without trauma narrative; Yes TN=with trauma narrative; ≥=3 or more sessions.

To be eligible for the study, children must have experienced contact sexual abuse, which was confirmed by NJ’s Division of Youth and Family Services (DYFS), PA’s Department of Children, Youth, and Families (CYF), a law enforcement official, or a professional with recognized expertise in conducting evaluations of CSA. Children who were allegedly sexually abused by other children were only accepted into the study when their abuse was verified by an independent child abuse professional as indicated above and the abuse involved an age or size differential and some indication that the child perpetrating the abuse had utilized physical force, verbal threats and/or coercion to engage and/or maintain the child’s cooperation and silence.

Children had to have at least five PTSD symptoms, including at least one symptom representing, respectively, avoidance, re-experiencing, and hyperarousal. Children with significant developmental disabilities (IQ < 70) and those having unsupervised face-to-face contact with the identified perpetrator were excluded. A child or a parent could not have a serious medical or mental health illness (e.g., psychosis) that would interfere with his or her participation in CBT treatment. The assessment and treatment protocols were consistent across sites, and the study was approved by each site’s respective Institutional Review Board (IRB).

As Figure 1 displays, 16 (8%) children and their parents never returned after being assigned to treatment, and 15 (7%) children and their parents left after attending only one or two sessions. These 31 (15%) children and their parents were defined as dropouts. Therefore, 179 (85%) children attended at least three TF-CBT sessions. This sample of completers was used for the subsequent analyses. The sample was restricted to children and parents with 3 or more sessions because a meta-analysis of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) studies by Barkham, Shapiro, Hardy, and Rees 9 found that at least three sessions are required before benefits from therapy occur. In addition, we utilized this cut-off in our earlier study 8 and thought it particularly important in this study given the importance of having a modicum of treatment to effectively address the questions about treatment length and the inclusion of a specific TF-CBT component. However, it should be noted that we did run analyses in which all of the patients volunteering for the study were included (intent-to-treat) and compared the results from these analyses with those in which only patients with 3 or more completed treatment sessions were included. There were no statistical differences. Therefore, we chose to base our present analyses on those with 3 or more TF-CBT sessions as we had done in our previous study.

The sample of child completers was composed of 61% girls with an average age of 7.7 years (SD = 2.1). The children were 65% Caucasian, 14% African American, 7% Hispanic and 14% other ethnic origins. Sixty-one percent of the children experienced oral-genital contact and/or penile penetration. The perpetrator was a related or unrelated adult in 51% of the cases with the remaining perpetrators being older children or teens. Participating parents were most frequently the child’s biological mother (84%) who was either currently married or cohabiting with a partner (67%) and who was employed either full- or part-time (60%). Thirty-five percent of the parents reported that they had also experienced contact CSA.

Outcome Measures

Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS),10 is a semi-structured interview that was administered independently to the child and the parent to assess the presence of DSM-IV-TR PTSD11 symptoms. The number of symptoms representing the Reexperiencing, Avoidance, and Hypervigilance symptom clusters were summed.

Parent Report Measures

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) 12 is a 21-item self-report instrument that was used to measure the severity of depression in the parent.

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) 13 is a 120-item parental rating scale that was used to measure externalizing and internalizing behavioral problems in the children.

Child Sexual Behavior Inventory (CSBI) 14 is a 42-item inventory that a parent uses to rate his or her child’s sexual behavior.

Parent Emotional Reaction Questionnaire (PERQ) 15 is a 15-item self-report instrument that measures the level of parental emotional distress in relation to his/her child being sexually abused.

Parent Practices Questionnaire (PPQ) 16 is a modified 31-item self-report instrument used by a parent to describe his/her interactions with his/her child, including three questions specific to interactions with his/her children regarding CSA.7

Child Report Measures

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) 17 is a 27-item self-report instrument that measures the severity of depression in children.

Fear Thermometer (Fear) 18 consists of a pictorial representation of a thermometer which helps children rate their sexual abuse-related level of fear/discomfort.

Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC) 19 is a 39 item self-report measure of global anxiety with well established construct validity.

The Shame Questionnaire (Shame) 20 is an 8-item self-report instrument that assesses a child’s or adolescent’s feelings of shame about being abused.

What If Situations Test (WIST) 21 is a brief interview using vignettes to assess young children’s abilities to recognize and respond effectively to hypothetical abusive situations.

Procedures

TF-CBT

Although detailed descriptions of TF-CBT can be found elsewhere, 4, 5 TF-CBT includes components that spell out the acronym PRACTICE: Psychoeducation and parenting, Relaxation, Affective modulation, Cognitive coping, TN, In vivo exposure, Conjoint parent child sessions and Enhancing safety and future development. TF-CBT, with all the components including the TN component, was only provided to those participants randomly assigned to the Yes TN conditions. In the Yes TN conditions, the TN component was covered in 3–4 sessions in the 8 session condition with at least double that number of TN sessions in the 16 session condition. For all participants, treatment typically began with the therapist dividing 90 minute treatment sessions into individual meetings (45 minutes each). Later in treatment, sessions involving conjoint parent child time typically involved 30 minutes with parent and child individually to prepare for a 30 minute conjoint session. In all conditions, both children and parents received TF-CBT components involving psychoeducation about CSA and skill building (i.e., relaxation, affective modulation, cognitive coping, and body safety training) as well as parenting skills training. However, only the children randomly assigned to the two TN groups were actively encouraged to develop a detailed narrative about the sexual abuse and related experiences which they processed and reviewed with the therapist as well as their non-offending parent.

Children and parents who were assigned to the No TN conditions were not encouraged to discuss and/or write about the details of the child’s sexual abuse experiences. Their sessions focused on psychoeducation about CSA and skill building exercises. However, when parents and children spontaneously shared cognitive distortions, therapists provided education to correct inaccurate and/or dysfunctional thoughts. Parents and children assigned to the 16 No TN condition were given more opportunities to review psychoeducational material and engage in skill repetition and practice, whereas the parents and children in the 16 Yes TN condition participated in additional TN sessions which focused on reviewing the details of their traumatic experiences and their associated thoughts, feelings, and sensations through the expansion of their narrative as well as other exposure activities (e.g., writing a poem or letter related to the sexual abuse).

Evaluations

The project coordinator at each site provided a detailed explanation of the study to the parents and children, and they were given an opportunity to ask any questions. After the parent and child read and signed their respective consent and assent forms, the project coordinator completed the screening questions and administered the assessment battery if appropriate. Children under the age of 7 years old were administered only the instruments appropriate for their age.

Following the initial assessment, each child was randomly assigned to one of the four treatment conditions. The families were told that they would be paid $25 for completing the initial evaluation, $25 for a 4 week evaluation, $50 for an 8 week evaluation, 16 week evaluation, and 6 and 12 month evaluations. Because the project coordinator was blind to treatment assignment, participants were told of the treatment assignment by the therapist during the first treatment session. All siblings participating in the study were assigned to the same condition. The therapists had graduate degrees in psychology, clinical social work, or a related field and had at least three years of clinical experience.

Treatment Adherence

Treatment adherence was supported through weekly intensive supervision sessions provided for the therapists by the first four authors who gave feedback based on audio-taped sessions. Randomly selected tapes from different stages of treatment were also reviewed by independent raters who were blind to the assigned treatment type further confirming that narratives were not written in the no narrative conditions.

Data analysis

Although the parents and children were randomly assigned to treatment, chi-square tests for independence, analyses of variance (ANOVA), and product-moment correlations were first calculated to ascertain whether: a) the data from the NJ and PA treatment sites were comparable with respect to the psychosocial characteristics of children and parents and the mean pre-treatment levels of the 14 outcome measures that are described below; b) the rates of “dropping out” of treatment (completing < 3 sessions) were comparable across the four treatment groups; and c) any of the psychosocial characteristics and pre-treatment outcome measures were associated with dropping out of treatment or eventually completing post-treatment evaluations after 8 nor 16 sessions. None of these characteristics or outcome measures was significantly differentiated by treatment location, dropping out of treatment, completing post-treatment evaluations, or number of treatment sessions completed. Therefore, NJ and PA data were pooled together for analytic purposes.

Prior to proceeding, we examined several characteristics of the participants. Given that the age range of the sample spanned across developmental stages, we tested age as both a covariate and also grouped the children into those who were ≤ 7 years old and those who were > 7 years old for all of our outcome measures in our mixed-model analyses of covariance (MM-ANCOVA). Age was neither a significant covariate nor yielded significant interactions with the other main effects for whether the children had been randomly assigned to receive 8 or 16 treatment sessions (length) or if there was a specific TN component in their treatment. The correlations of age as a continuous variable with the residualized gain scores for Hyperarousal, Reexperiencing, and Avoidance were, respectively, −.12 −.08, and −.02, and the respective point-biserial correlations of age group (0 = <=7, 1 = > 7) are −.04, .02, and −.03. Because the children were randomly assigned to the four groups representing number of sessions and TN, age was not significantly related to either number of sessions (8 vs. 16) or inclusion of the TN component (0 = No, 1 = Yes). Research has found that proposed covariates with correlations < .30 do no have any significant or meaningful clinical impact upon outcome; therefore we did not include age as a covariate.21 We also examined the impact of sibling pairs being assigned to the same condition by performing generalized estimating equation (GEE) ANCOVAs testing for household as either a main effect or potential covariate. In fact, MM-ANCOVAs were performed for all of our outcome measures in which the siblings were or were not included since there were no significant or clinically meaningful differences as reflected in the effect sizes. The correlation of the number of siblings with the residualized gain scores for Hyperarousal, Reexperiencing, and Avoidance were, respectively, −.06, −.11, and −.03; all of these correlation reflect trivial effect sizes. Therefore, we did not control for household in our MM-ANCOVAs.

Two-factor, linear mixed-model repeated-measures ANOVAs were next performed with all of the 14 outcome measures. The main effects were for type of condition (8 No TN, 8 Yes TN, 16 No TN, and 16 Yes TN) and time (pre-treatment, 8 weeks, and 16 weeks) and the interaction was for type of condition by time. The identity of the children or parents was considered to represent a random effect in the repeated ANOVAs. All 14 outcome measures for the four groups significantly (ps < .05, two-tailed test) improved over time. However, none of the mean differences for the 14 outcome measures between the 8- and 16-week evaluations for the families that were treated in the 8 session groups was significant, whereas seven of the 14 outcome measures continued to improve between the 8 and 16 week assessments for the clients who were in the 16 session groups, even after applying a Bonferroni adjustment for alpha of .05 / 14 to control for the family wise error rate. Therefore, it was concluded that the 8 week outcome scores for the children/parents assigned to the 8 session groups and the 16 week outcome scores for those assigned to the 16 session groups were the appropriate post-treatment estimates for measuring response to treatment.

Two-by-two, linear MM-ANCOVAs were finally calculated in which the main effects were for length of treatment (8 weeks vs. 16 weeks) and whether the TN component was used (No vs. Yes). The covariate was the respective pre-treatment score for the outcome measure score under analysis. The subjects were again assumed to be random effects in all of the ANCOVAs. A MM-ANCOVA is robust with respect to the occurrence of randomly missing data. Consequently, all of the available data at each evaluation were employed in the mixed model analyses, regardless if a child or parent missed one of the 8 or 16 week evaluations.

A modified intent-to-treat approach was also used to assess the impact of missing data upon ANCOVA results. SAS Multiple Imputation and Multiple Imputation Analysis 23 procedures were employed to estimate the missing post-treatment outcome scores and 10 maximum-likelihood pre- and post-treatment complete sets of data were generated for each of the 14 outcome measures based on the initial number of respondents with pre-treatment scores. All of the parameter estimates from the MM-ANCOVAS with the multiple imputation datasets were similar to those that had been found without imputing missing data. Therefore, only the ANCOVA results with the complete sets of data are reported. Cohen’s d 24 statistic was calculated to estimate the magnitude of any significant mean difference that was found using formulae given by Smithson.25

RESULTS

Figure 1 shows the number of children who completed three or more sessions and a post-test K-SADS assessment in each of the treatment conditions. The mean number of TF-CBT sessions attended by the 87 children and their parents in the two 8 session conditions was 7.36 (SD = 1.33, median = 8, range = 3 – 8), whereas the mean number was 13.92 (SD = 3.34, median = 16, range 3 – 16) for the 92 children and their parents in the two 16 session conditions. Of the children/parents assigned to the 8 session conditions, 63 (72%) completed all eight treatment sessions, whereas only 50 (54%) of the children/parents assigned to the 16 session conditions completed all 16 sessions of treatment.

Pre- and Post-Treatment Changes

Paired t tests were calculated for all of the 14 outcome measures within each treatment group. Cohen’s d 23 statistic was also calculated to estimate the magnitudes of the 56 (four groups x 14 outcome measures) significant, adjusted pre- and post-treatment mean differences that were found. All of these effect sizes were large according to Cohen’s23 interpretative guidelines and were statistically comparable across the four treatment groups [F(3, 52) = 1.48, ns.] For the set of 56 mean differences, the mean d was .94 (SD = .51, median = .81).

Treatment Differences

Table 1 lists the adjusted mean post-treatment scores for the four treatment conditions along with the standard errors for the adjusted post-treatment means of the 14 outcome measures. The results of the ANCOVAs are displayed in Table 2 along with the d statistics for the significant adjusted mean differences. Table 2 includes all the measures including those for which no differences were found across the treatment conditions.

Table 1.

Adjusted Post-Treatment Means and Standard Errors of Outcome Measures by Length of Therapy and Use of Trauma Narrative

| Scale | Length of Therapy | Trauma Narrative | N | Madj | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-SADS Reexperiencing | |||||

| 8 Sessions | No | 40 | 1.79 | 0.21 | |

| Yes | 39 | 1.86 | 0.22 | ||

| 16 Sessions | No | 35 | 1.03 | 0.23 | |

| Yes | 44 | 1.45 | 0.20 | ||

| K-SADS Avoidance | |||||

| 8 Sessions | No | 40 | 1.80 | 0.19 | |

| Yes | 39 | 1.68 | 0.20 | ||

| 16 Sessions | No | 35 | 1.05 | 0.21 | |

| Yes | 44 | 1.36 | 0.18 | ||

| K-SADS Hypervigilance | |||||

| 8 Sessions | No | 40 | 1.37 | 0.20 | |

| Yes | 39 | 1.27 | 0.20 | ||

| 16 Sessions | No | 35 | 0.83 | 0.21 | |

| Yes | 44 | 1.36 | 0.19 | ||

| CBCL Internalizing | |||||

| 8 Sessions | No | 40 | 7.15 | 0.99 | |

| Yes | 38 | 6.43 | 1.02 | ||

| 16 Sessions | Yes | 38 | 6.43 | 1.02 | |

| No | 35 | 3.99 | 1.05 | ||

| Yes | 43 | 6.74 | 0.94 | ||

| CBCL Externalizing | |||||

| 8 Sessions | No | 40 | 8.59 | 0.98 | |

| Yes | 38 | 9.75 | 1.01 | ||

| 16 Sessions | No | 35 | 6.05 | 1.06 | |

| Yes | 43 | 10.36 | 0.95 | ||

| CSBI | |||||

| 8 Sessions | No | 39 | 3.72 | 0.68 | |

| PPQ | Yes | 38 | 3.52 | 0.69 | |

| 16 Sessions | No | 35 | 1.68 | 0.72 | |

| Yes | 43 | 2.99 | 0.66 | ||

| PERQ | |||||

| 8 Sessions | No | 38 | 32.21 | 1.72 | |

| Yes | 36 | 27.05 | 1.78 | ||

| 16 Sessions | No | 30 | 27.38 | 1.96 | |

| Yes | 36 | 30.46 | 1.77 | ||

| PPQ | |||||

| 8 Sessions | No | 37 | 151.03 | 2.22 | |

| Yes | 36 | 150.97 | 2.25 | ||

| 16 Sessions | No | 31 | 157.03 | 2.42 | |

| Yes | 36 | 150.58 | 2.25 | ||

| BDI-II | |||||

| 8 Sessions | No | 38 | 7.51 | 1.12 | |

| Yes | 37 | 5.93 | 1.13 | ||

| 16 Sessions | No | 31 | 5.27 | 1.24 | |

| Yes | 36 | 8.30 | 1.14 | ||

| CDI | |||||

| 8 Sessions | No | 28 | 6.50 | 1.07 | |

| Yes | 26 | 6.29 | 1.10 | ||

| 16 Sessions | No | 29 | 6.19 | 1.04 | |

| Yes | 29 | 4.65 | 1.04 | ||

| MASC | |||||

| 8 Sessions | No | 28 | 48.75 | 3.17 | |

| Yes | 26 | 37.23 | 3.30 | ||

| 16 Sessions | No | 28 | 36.58 | 3.11 | |

| Yes | 29 | 42.00 | 3.05 | ||

| Shame | |||||

| 8 Sessions | No | 35 | 3.18 | 0.53 | |

| Yes | 27 | 2.41 | 0.62 | ||

| 16 Sessions | No | 33 | 1.87 | 0.53 | |

| Yes | 29 | 2.87 | 0.57 | ||

| Fear | |||||

| 8 Sessions | No | 40 | 2.97 | 0.23 | |

| Yes | 38 | 2.16 | 0.23 | ||

| 16 Sessions | No | 36 | 2.67 | 0.24 | |

| Yes | 42 | 1.95 | 0.22 | ||

| WIST Skills | |||||

| 8 Sessions | No | 41 | 19.60 | 0.61 | |

| Yes | 39 | 19.42 | 0.62 | ||

| 16 Sessions | No | 36 | 19.90 | 0.65 | |

| Yes | 44 | 19.19 | 0.59 | ||

Note. BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II, CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist, CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory, CSBI = Child Sexual Behavior Inventory, Fear = Fear Thermometer, Shame = Shame Questionnaire, Madj = Adjusted Mean, K-SADS = Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children, MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, PERQ = Parent Emotional Reaction Questionnaire, PPQ = Parent Practices Questionnaire, SE = Standard Error of the Mean, WST = What-If-Situations Test Skills subscale

Table 2.

Mixed-Model Analyses of Covariance for Outcome Measures

| Scale | Source | (1, df) | F | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-SADS Reexperiencing | ||||

| Length | 153 | 7.46** | ||

| Trauma Narrative | 153 | 1.37 | ||

| Length X TN | 153 | 0.64 | ||

| MadjDiff: 8 Sessions > 16 Sessions | 0.44 | |||

| K-SADS Avoidance | ||||

| Length | 153 | 7.50** | ||

| Trauma Narrative | 153 | 0.24 | ||

| Length X TN | 153 | 1.17 | ||

| MadjDiff: 8 Sessions > 16 Sessions | 0.44 | |||

| K-SADS Hypervigilance | ||||

| Length | 153 | 1.28 | ||

| Trauma Narrative | 153 | 1.17 | ||

| Length X TN | 153 | 2.42 | ||

| CBCL Internalizing | ||||

| Length | 151 | 2.01 | ||

| Trauma Narrative | 151 | 0.99 | ||

| Length X TN | 151 | 2.41 | ||

| CBCL Externalizing | ||||

| Length | 151 | 0.93 | ||

| Trauma Narrative | 151 | 7.48** | ||

| Length X TN | 151 | 2.41 | ||

| MadjDiff: Yes > No | 0.45 | |||

| CSBI | ||||

| Length | 150 | 3.52 | ||

| Trauma Narrative | 150 | 0.66 | ||

| Length X TN | 150 | 1.17 | ||

| PERQ | ||||

| Length | 135 | 0.15 | ||

| Trauma Narrative | 135 | 0.33 | ||

| Length X TN | 135 | 5.21* | ||

| MadjDiff: 8 Sessions No > 8 Session Yes | 0.36 | |||

| PPQ | ||||

| Length | 135 | 0.62 | ||

| T rauma Narrative | 135 | 6.51* | ||

| Length X TN | 135 | 4.39* | ||

| MadjDiffs: No > High | 0.44 | |||

| 16 Sessions No > 8 Sessions No | 0.34 | |||

| 16 Sessions No > 8 Sessions Yes | 0.40 | |||

| 16 Sessions No > 16 Sessions Yes | 0.55 | |||

| BDI-II | ||||

| Length | 137 | 0.00 | ||

| Trauma Narrative | 137 | 0.54 | ||

| Length X TN | 137 | 2.92 | ||

| CDI | ||||

| Length | 107 | 0.84 | ||

| Trauma Narrative | 107 | 0.72 | ||

| Length X TN | 107 | 0.37 | ||

| MASC | ||||

| Length | 106 | 1.44 | ||

| Trauma Narrative | 106 | 0.87 | ||

| Length X TN | 106 | 16.98*** | ||

| MadjDiffs: 8 Sessions No > 8 Sessions Yes | 0.55 | |||

| 8 Sessions No > 16 Sessions No | 0.57 | |||

| Shame | ||||

| Length | 119 | 0.58 | ||

| Trauma Narrative | 119 | 0.04 | ||

| Length X TN | 119 | 2.31 | ||

| Fear | ||||

| Length | 151 | 1.22 | ||

| Trauma Narrative | 151 | 11.10*** | ||

| Length X TN | 151 | 0.03 | ||

| MadjDiff: No > Yes | 0.54 | |||

| WIST Skills | ||||

| Length | 155 | 0.00 | ||

| Trauma Narrative | 155 | 0.52 | ||

| Length X TN | 155 | 0.18 | ||

Note. TN = Trauma Narrative, BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II, CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist, CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory, CSBI = Child Sexual Behavior Inventory, Fear = Fear Thermometer, Shame = Shame Questionnaire, MadjDiff = Difference of Adjusted Means, K-SADS = Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children, MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, PERQ = Parent Emotional Reaction Questionnaire, PPQ = Parent Practices Questionnaire, WIST = What-If-Situations Test Skills subscale

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Parent Report Outcomes

As Table 2 shows, parents who were assigned to No TN conditions described significantly greater improvements on their PPQ scores than the parents who were assigned to Yes TN conditions. The significant interaction of Length x TN for the PPQ shown in Table 2 reveals that the parents in the 16 No TN condition described higher levels of effective parenting practices as compared to the parents in the Yes TN conditions. The children who had received the No TN conditions also were rated by their parents as having fewer externalizing problems than the children assigned to the Yes TN conditions. With respect to the PERQ, parents who were assigned to the 8 Yes TN group described themselves as being less emotionally upset by the abuse than did the parents who were assigned to the 8 No TN group at the post-treatment assessment.

Child Self-Report Outcomes

At post-treatment, on the FT, children who had received the TN component described less fear associated with thinking or talking about the abuse as compared to the children in the No TN conditions. Furthermore, on the MASC, children assigned to the 8 Yes TN condition reported less anxiety at post-treatment as compared to children assigned to the 8 No TN condition.

PTSD Outcomes

As Table 2 indicates, children who received 16 sessions were rated as having fewer symptoms of Re-experiencing and Avoidance at post-treatment than those who received 8 sessions. In both instances, the adjusted mean differences for the 8 and 16 session groups reflected a medium effect size (d = .44). However, the adjusted mean difference between the groups at 8 and 16 weeks for the Re-experiencing and Avoidance subscales represented a reduction in only one PTSD symptom, if the adjusted mean differences for both scales are summed.

DISCUSSION

The overall pattern of results indicate that for children 4–11 years of age with a history of CSA and their non-offending parents, TF-CBT was effective in enhancing a broad spectrum of affective and behavioral functioning as well as parenting and child personal safety skills. The pre- to post-treatment changes in all four groups represented “moderate to large” effect sizes, suggesting that all of the TF-CBT conditions were efficacious. However, some differential responses were found across groups depending on the outcome of interest. For example, parents in the 16 No TN group reported significantly greater improvements in parenting practices than those assigned to the Yes TN groups. Children who were treated without the TN component were rated by their parents as having less severe externalizing behavior problems than those who were treated with the TN component. Because the therapists and parents in the No TN groups devoted more time to the parent training component, this might have resulted in the greater improvements in both parenting practices and their children’s externalizing behaviors. In the Yes TN groups, a substantial proportion of the parent’s time was devoted to reviewing the child’s narrative and preparing for conjoint parent-child sessions, thereby reducing time spent on parenting skills.

Interestingly, parents in the 8 Yes TN group described less abuse-specific emotional distress after treatment than the parents in the 8 No TN group. This finding suggests that the focus on reviewing and processing parental thoughts and feelings as well as the child’s trauma narrative might have led to reduced parental abuse-specific distress. Regardless of treatment length, the levels of abuse-related fear were less for the children who had been assigned to the Yes TN groups. Similarly, the children assigned to the 8 Yes TN group reported significantly less anxiety as compared to children assigned to the 8 No TN group. Taken together, these findings suggest that the 8 Yes TN group appeared to be the most efficient and efficacious means of addressing parental abuse-specific distress as well as children’s abuse-related fear and general anxiety.

With respect to PTSD symptoms, longer length of treatment was associated with a decrease in the number of avoidance and re-experiencing symptoms. However, the addition of 8 more sessions yielded a decrease in approximately only one PTSD symptom.

A recent study examining the change processes associated with the implementation of TF-CBT demonstrated that “processing” as reflected in children’s trauma-related statements and understanding was the critical mechanism for producing positive outcomes.26 As noted above, trauma processing may be achieved fastest in the 8 Yes TN condition, but it may also be achieved with more treatment sessions without the TN component (i.e., 16 No TN). From a clinical perspective, this may explain why children across all conditions responded well to treatment as participants assigned to all conditions experienced some level of education, exposure and processing. Although children assigned to the No TN groups were not encouraged to talk or write in detail about their sexually abusive experiences, the CSA education, body safety, and other coping skills components

led to some exposure and processing of their abusive experiences. In addition, for practical and ethical reasons, across all conditions, when children presented with sleep and/or school refusal problems, in collaboration with the caregivers, therapists developed a behavior management plan that gradually exposed children to the feared situations (e.g. school, darkness, sleeping in their room alone). Thus, children in the No TN conditions experienced some in vivo exposure and processing in this context as well. Furthermore, when children in the No TN conditions spontaneously shared cognitive distortions, therapists offered corrective psychoeducation which very likely led to improved cognitive processing. Still, in the Yes TN conditions child and parental cognitive distortions were elicited and likely identified and corrected more efficiently. Moreover, many children assigned to the Yes TN conditions reported that talking about the sexual abuse specifically was the most helpful part of therapy, thus replicating similar reports by older children in a previous study. 27

The findings of the current investigation should be interpreted with caution given the relatively small cell sizes and the other design and measurement limitations described above. In addition, the present findings may only generalize to young children who have experienced CSA. The normal cognitive and developmental limitations of children 4 to 11 years old may explain why the inclusion of TN sessions did not produce dramatic differences across groups. On the other hand, the PTSD measure may not have been sensitive enough to developmental manifestations of PTSD to detect subtle differences in active treatments. Also, because of the sample’s young age, some of the outcome measures could not be administered to all of the children limiting the statistical power of some of the analyses.

Future treatment outcome research should examine children presenting comorbid conditions, the role of parental involvement and the degree of trauma focus necessary to produce optimal outcomes across domains. The findings of recent research demonstrated that standard CBT produced poorer outcomes for depressed adolescents with a history of CSA as compared with those with no such history. 28 These results suggest that Trauma-focused CBT may improve outcomes for those depressed adolescents with a CSA history. The results of a recent adult study examining cognitive processing therapy (CPT) for adults experiencing PTSD suggested that CPT with or without a written narrative produced similar outcomes. 29 However, it should be noted that similar to this investigation, CPT with or without a narrative has a clear trauma focus. Our prior and current TF-CBT research findings suggest a trauma focus may be important to enhance a child’s understanding of a traumatic event and optimize outcomes, 8 but such a focus may not necessarily require a detailed written narrative in all cases to achieve PTSD recovery. Rather there may be alternative TF-CBT methods and varying lengths of treatment needed to attain optimal outcomes depending on children’s initial symptom presentations. Our current and previous treatment outcome findings8 do appear to be consistent with the adult PTSD treatment literature that has documented the greater efficacy of alternative CBT approaches over supportive counseling regardless of whether specific imaginal exposure exercises are utilized.30 In general, the current findings seem to suggest the value of tailoring children’s treatment plans to optimally address their symptom presentations. In so doing, the trauma narrative and processing component might be emphasized for those children presenting primarily with fear and anxiety, while trauma-focused parenting and coping skill building might be the initial focus for those with significant externalizing behavior problems.

CONCLUSIONS

The alternative TF-CBT formats examined in this investigation all produced positive outcomes, with some differential responses depending on the outcome of interest. The TN component appears to be particularly important in effectively and efficiently reducing a child’s abuse-related fear and general anxiety as well as alleviating parental abuse-specific distress. On the other hand, 16 sessions of TF-CBT treatment without the TN component appears to lead to the most improvement with respect to parenting practices and fewer externalizing child behavior problems.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grants from NIMH (R01-MH064776 and R01-MH064635.). The authors would like to express special thanks to the research coordinators, study therapists, research and administrative assistants, and all of the parents and children who participated in the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beitchman JH, Zucker KJ, Hood JE, et al. A review of the short-term effects of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1992;15:537–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silverman WK, Ortiz CD, Viswesvaran C, et al. Evidence-based psychosocial treatment for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events. J Clin ChildAdol Psychol. 2008;37:156–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saunders BE, Berliner L, Hanson RF. (Eds). Child Physical and Sexual Abuse: Guidelines for Treatment (Revised Report: April 26, 2004).2004Charleston, SC: National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen J, Mannarino AP, Deblinger E. Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deblinger E, Heflin AH. Treating sexually abused children and their nonoffending parents. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothbaum BO, Meadows EA, Resick P, Foy D. Cognitive behavioral therapy In Foa EB, Keane TM, & Friedman MJ (Eds). Effective Treatments for PTSD (pp. 60–83). New York: Guilford Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deblinger E, Stauffer L, Steer R. Comparative efficacies of supportive and cognitive behavioral group therapies for children who were sexually abused and their nonoffending mothers. Child Maltreat. 2001;6:332–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen JA, Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Steer RA. A multi-site, randomized controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiat. 2004;43: 393–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barkham M, Shapiro DA, Hardy GE, Rees A. Psychotherapy in two-plus-one sessions: Outcomes in a randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral and psychodynamic-interpersonal therapy for subsyndromal depression. J Consul Clin Psychol. 1999;67:201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington: DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory (2nd ed.). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Achenbach TM. Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4–18 YSR and TRF profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedrich WN, Grambsch P, Damon L, et al. The Child Sexual Behavior Inventory: Normative and clinical comparisons. Psychol Assess.1992; 4:303–311. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. A treatment outcome study for sexually abused preschooler children: Initial findings. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. 1996;35:42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strayhorn JM, Weidman CS. A parent practices scale and its relation to parent and child mental health. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. 1988;27:613–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovacs M Children’s Depression Inventory. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hersen M, Bellack AS. Dictionary of behavioral assessment techniques. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.March JS, Parker JDA, Sullivan K, et al. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children: Factor structure, reliability and validity. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry, 1997;36: 554–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feiring C, Taska L, Lewis M. Age and gender differences in children’s and adolescents’ adaptation to sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1999;23:115–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarno JA, Wurtele SK. Effects of a personal safety skills program on preschooler’s knowledge, skills and perceptions of sexual abuse. Child Maltreat. 1997;2:35–45. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allison DB. When is it worth measuring a covariate in a randomized trial? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:339–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.SAS Institute, Inc. SAS/STAT software: Changes and enhancements, release 8.2. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen J A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smithson M Confidence intervals: Quantitative applications in the social sciences, No. 140. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayes AM, Webb C, Grasso D, et al. Processes that inhibit and facilitate change in trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for youth exposed to interpersonal trauma. 2009. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- 27.Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Cohen JA, Steer RA. Follow-up study of a multisite, randomized, controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms: Examining predictors of treatment response. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. 2006;45:1474–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barbe RP, Bridge JA, Birmaher B, et al. Lifetime history of sexual abuse, clinical presentation, and outcome in a clinical trial for adolescent depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Resick PA, Galovski TE, Uhlmansiek MO, et al. A randomized clinical trial to dismantle components of cognitive processing therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in female victims of interpersonal violence. J Consul Clin Psychol. 2008;76:243–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vickerman KA, Margolin G Rape treatment outcome research: Empirical findings and state of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(5), 431–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]