Abstract

Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM) is an inherited disorder with variable genetic etiologies. Here, we focused on understanding the precise molecular pathology of a single clinical variant in DSP, the gene encoding desmoplakin. We initially identified a potentially novel missense desmoplakin variant (p.R451G) in a patient diagnosed with biventricular ACM. An extensive single-family ACM cohort was assembled, revealing a pattern of coinheritance for R451G desmoplakin and the ACM phenotype. An in vitro model system using patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cell lines showed depressed levels of desmoplakin in the absence of abnormal electrical propagation. Molecular dynamics simulations of desmoplakin R451G revealed no overt structural changes, but a significant loss of intramolecular interactions surrounding a putative calpain target site was observed. Protein degradation assays of recombinant desmoplakin R451G confirmed increased calpain vulnerability. In silico screening identified a subset of 3 additional ACM-linked desmoplakin missense mutations with apparent enhanced calpain susceptibility, predictions that were confirmed experimentally. Similar to R451G, these mutations are found in families with biventricular ACM. We conclude that augmented calpain-mediated degradation of desmoplakin represents a shared pathological mechanism for select ACM-linked missense variants. This approach for identifying variants with shared molecular pathologies may represent a powerful new strategy for understanding and treating inherited cardiomyopathies.

Keywords: Cardiology, Genetics

Keywords: Genetic diseases, Heart failure, Molecular pathology

Desmoplakin variant (p.R451G) causes arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy through enhanced vulnerability to calpain-mediated degradation.

Introduction

Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM) is an inherited disease characterized by fibrofatty replacement of the myocardium, ventricular arrhythmias, heart failure, and elevated risk of sudden cardiac death (1). Previously known as arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, the more inclusive designation of ACM reflects increasing recognition that either ventricle (or both) can be involved (2). The majority of biventricular cases feature primary right ventricular impairment, with secondary left ventricular involvement occurring in the later stages of disease progression (3). However, recent work has identified a subset of cases that present with left ventricular fibrosis, arrhythmias, and a mildly affected right ventricle (4, 5).

ACM-linked mutations have been identified in a variety of desmosomal genes, including plakophilin (PKP), junction plakoglobin (JUP), desmoglein (DSG), desmocollin (DSC), and desmoplakin (DSP). Although desmoplakin mutations comprise only approximately 5% of ACM cases (1), they have been shown in a large multicenter study to be associated with an unusually high degree of penetrance (6). Truncating mutations to desmoplakin, resulting in lower total protein levels, are linked to more severe outcomes and early occurrences of sudden cardiac death (7, 8). Additionally, of the 42 previously reported truncating mutations in desmoplakin, the majority are found in patients with left ventricular disease (7). Therefore, the presence of a truncating desmoplakin variant in an individual indicates significant future risk for developing ACM with left ventricular involvement.

In contrast with truncating mutations, missense mutations to desmoplakin do not appear to have consistent clinical phenotypes. While some of the literature reports earlier ACM presentation with increased severity as a result of missense mutations (9, 10), missense mutations in desmoplakin are not uniformly linked with left ventricular manifestation of ACM (11). The absence of a consistent clinical phenotype for missense desmoplakin variants limits the clinical value of genotyping in the management of ACM and calls for a more nuanced understanding of their molecular pathologies. We have approached the task of elucidating genotype-phenotype relationships for desmoplakin missense variants through a potentially novel combination of several complementary techniques, including genetic linkage analysis, experimental and computational biophysics, and induced pluripotent stem cell–based (iPSC-based) disease modeling.

Our efforts initially focused on a specific missense desmoplakin variant (p.R451G) identified in a human cohort. Experimental evidence led to the discovery that the desmoplakin protein encoded by DSP R451G showed enhanced calpain vulnerability. Using experimental and in silico tools, we subsequently identified 3 additional missense desmoplakin mutations that share the molecular phenotype of enhanced calpain-mediated degradation. Importantly, these 4 mutations together share the clinical phenotype of biventricular ACM. Our data point to a mechanism by which certain desmoplakin missense mutations are functionally equivalent to truncating mutations, leading to the same biventricular ACM phenotype.

In addition to identifying common pathomechanisms between missense desmoplakin variants, the success of this approach supports the potential of in vitro and in silico tools to enhance the value of clinical genetic testing, revealing common disease pathways and paving the way for precision molecular therapies.

Results

The ACM phenotype segregates with a potentially novel mutation in desmoplakin (p.R451G).

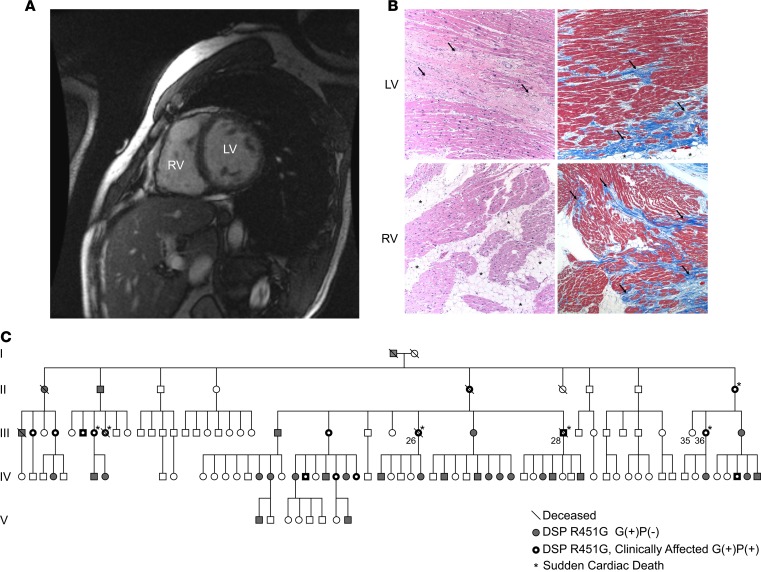

The index patient (III-28) was a 44-year-old male who suffered sudden cardiac death during vigorous exercise. The patient had a history of asymptomatic biventricular dysfunction on cardiac MRI (Figure 1A and Supplemental Video 1; supplemental material available online with this article; https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.128643DS1). Gross examination of the heart during autopsy revealed dilation of the right ventricle and severe fibrofatty scarring in the left and right ventricles. H&E and Masson’s trichrome staining of myocardial explants from a second individual (III-26) revealed extensive biventricular myocyte disarray and fibrofatty infiltration (Figure 1B). Following a positive diagnosis for ACM by the 2010 Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy (ARVC) Task Force criteria, whole-exome sequencing identified a potentially novel missense variant in the gene DSP (ENST00000379802.8; c.1596CGT>GGT; Chr. 6:7568521, GRCh38.p12) encoding desmoplakin (p.R451G).

Figure 1. Patient presenting with genetically linked ACM.

(A) Short-axis cardiac magnetic resonance image of the proband (III-28) 1 decade prior to a sudden cardiac death episode. Dilation of the left ventricle (LV) and right ventricle (RV) and RV wall thinning are clearly evident. (B) Representative images of cardiac biopsy from a second sudden death victim, individual III-26, showing hallmarks of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM), including extensive biventricular myocyte disarray and fibrofatty infiltration. Images show H&E-stained sections (left) and Masson’s trichrome–stained sections (right) from the LV (top) and RV (bottom). Original magnification, ×100. Histology of the RV free wall shows an extensive fatty infiltrate (arrows) and areas of full-thickness replacement of RV myocardium by adipose tissue. The residual muscle is present in a band-like or wave-front pattern (H&E). Trichrome staining highlights transmural fibrofatty infiltration by the fibrotic tissue in blue (arrows). Histology of the LV shows patchy fibrosis (arrows, H&E). Trichrome staining highlights patchy fibrosis (arrows) and mild subepicardial adipose tissue replacement (asterisks). (C) Extended pedigree of proband. White symbols represent unaffected individuals that also lack the DSP R451G mutation. Gray symbols represent individuals that carry the R451G mutation but do not yet show clinical phenotype [G(+)P(–)]. Black symbols with a white center represent mutation positive individuals with clinical symptoms of ACM [G(+)P(+)]. Slashes denote deceased individuals. Asterisks denote individuals who experienced a sudden cardiac death event. Analysis revealed a highly significant linkage between DSP R451G and the ACM phenotype (LOD score 7.65).

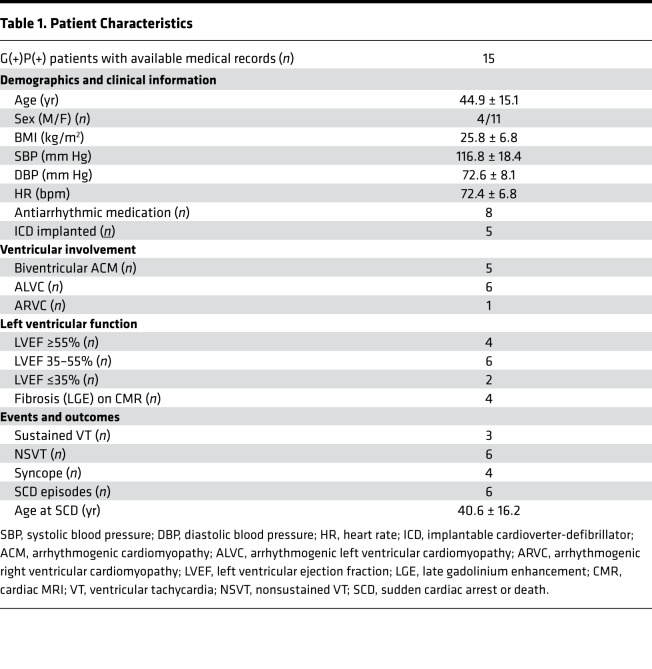

We proceeded with cascade genetic screening of 115 additional family members, 45 of whom (39%) were found to carry the desmoplakin R451G mutation [G(+)] (Figure 1C). All genetically tested individuals were asked to self-report information about their health status and cardiac symptoms and, in cases in which patients were systematically followed by a cardiologist, allow access to their medical records. None of the G(–) patients reported a history of cardiomyopathy or heart failure. We obtained access to records of 21 G(+) individuals, of whom 15 were symptomatic or phenotype positive [G(+)P(+)], based on evidence of one or more of the following: (a) ventricular dysfunction, dilation, or scarring/fat infiltration on imaging studies or autopsy reports in the absence of other causes (e.g., coronary ischemia); (b) recorded ventricular arrhythmias; (c) implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) implant; and/or (d) sudden cardiac arrest or death. Of the G(+)P(+) patients, 6 had evidence of dilated cardiomyopathy, 1 fulfilled 2010 Task Force criteria for ARVC, and 5 had biventricular involvement. The 3 remaining patients experienced ventricular arrhythmias with no evidence of structural heart disease on echocardiography or cardiac MRI. No individual exhibited any connective tissue dysplasias (wooly hair, skin, or teeth abnormalities), which can present with some ACM variants (12). The demographic, clinical, and imaging data of G(+)P(+) patients in our cohort are presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics.

Table 2. Patient Characteristics.

Six G(+)P(+) patients (1 male, 5 female) had sudden cardiac arrest or death at a mean age of 40.6 ± 16.2 years; for 2 of them (male/female, cousins) this was the first manifestation of ACM. Autopsies reported extensive right ventricular fatty infiltration in the first case, and severe left ventricular subendocardial fibrosis in the second. Five patients (1 male, 4 female) have received an IC (4 for primary and 1 for secondary prevention), with 1 subsequent appropriate ICD shock. T wave inversions were observed in electrocardiograms of all G(+)P(+) individuals, but no epsilon waves were noted.

In our cohort, there seemed to be no apparent pattern in disease progression. Yearly imaging studies showed stable left ventricular dysfunction for 5 years after diagnosis in 1 individual (left ventricular ejection fraction = 35%), followed by a gradual decline over the next 4 years (down to 17%). Another individual showed a substantial increase in right ventricular chamber size (right ventricular end-diastolic volume from 134 ml to 252 ml), along with de novo appearance of extensive left ventricular fibrosis (assessed by late gadolinium enhancement) on cardiac MRI, within the span of 12 months (without an obvious precipitator). A third individual followed a moderate gradual decline of left ventricular function (left ventricular ejection fraction from 45% to 28%) over 9 years (Supplemental Figure 1, A–D).

Linkage analysis using available clinical data revealed a maximum logarithm of the odds (LOD) score for coinheritance of the ACM phenotype and the p.R451G mutation to be 7.65 (θ = 0). In other words, the odds that the ACM phenotype and p.R451G are not linked are less than 1 in 10 million. Cardiac palpitations and atrial fibrillation were present in some elderly G(–) individuals, but this was not regarded as evidence of cardiomyopathy for LOD score calculations.

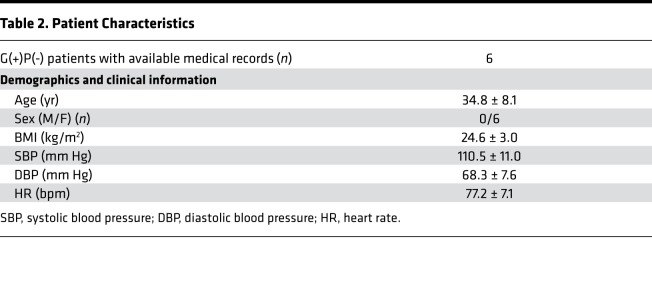

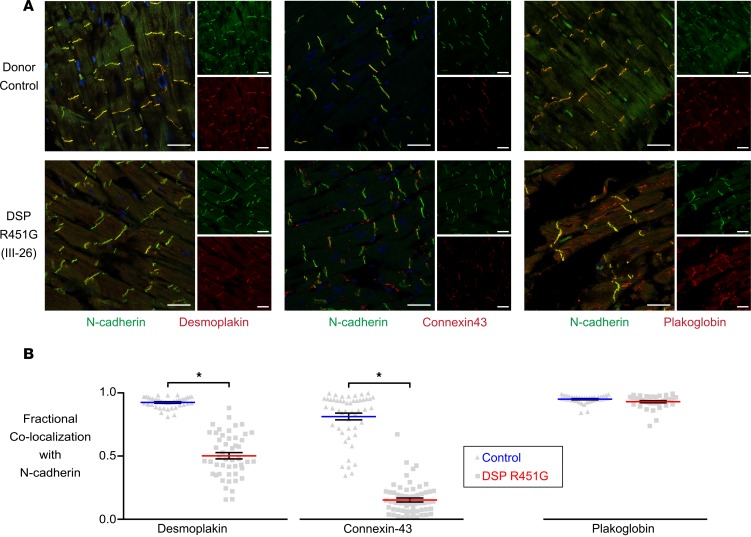

R451G individuals have reduced levels of select proteins at intercalated discs.

We used immunofluorescence to assess the subcellular localization of desmoplakin and other essential intercalated disc proteins. Left ventricular explants obtained during autopsy of individual III–26 revealed a decrease in levels of desmoplakin and connexin-43 at the intercalated disc (Figure 2A). Colocalization analysis of desmoplakin and N-cadherin (an intercalated disc marker) showed a significant reduction (42% loss) in immunoreactive signals of desmoplakin at the intercalated disc compared with a donor control (Figure 2B). Interestingly, connexin-43, an essential gap junction protein, also showed a significant reduction (65% loss) at the intercalated disc (Figure 2B). Altered desmoplakin levels at the intercalated discs have been shown to impair connexin-43 membrane localization (13). Plakoglobin, another desmosomal protein, was distributed normally with N-cadherin at the intercalated disc.

Figure 2. Significant loss of desmoplakin and connexin-43 at the intercalated discs in an R451G-positive patient with clinical ACM diagnosis.

(A) Representative immunofluorescence images from a donor control (OSU 652849) and patient III-26, who carried DSP R451G and was clinically diagnosed with ACM. Left ventricular tissue was stained with antibodies for desmoplakin (left), connexin-43 (middle), or plakoglobin (right). Tissues were costained with an antibody for N-cadherin (green), identifying intercalated discs. Scale bar: 40 μm. (B) Mander’s colocalization analysis of selected protein overlap with N-cadherin at intercalated disks. Individual III-26 had significantly lower amounts of desmoplakin (n = 42 control and n = 49 patient) and connexin-43 (n = 50 control and n = 60 patient) at intercalated discs as compared with donor controls. There was no significant loss of plakoglobin at the intercalated disk (n = 40 control and n = 37 patient). *P < 0.0001 using 2-tailed unpaired t test with Bonferroni correction. Error bars represent SEM.

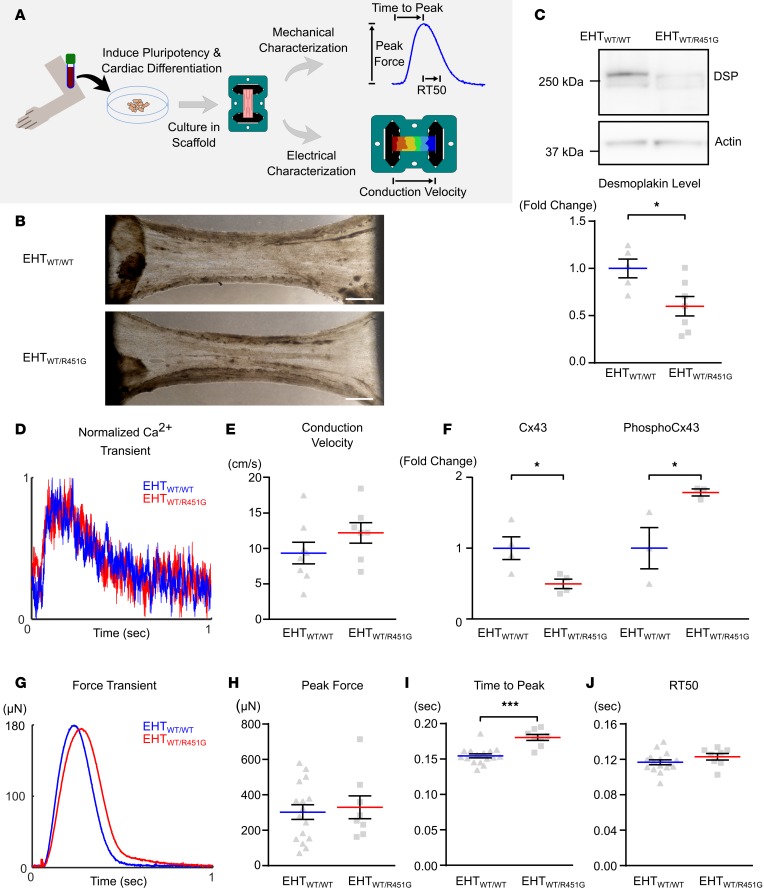

Engineered heart tissues constructed from patient-derived iPSCs exhibit reduced levels of desmoplakin in the absence of conduction velocity defects.

According to previously published reports, decreased amounts of desmoplakin at the intercalated disc may lead to a loss of functional connexin-43 and impaired electrical conduction among neighboring cells (13, 14). To test this hypothesis, we created engineered heart tissues (EHTs) grown from iPSCs of a G(+)P(+) individual and a healthy G(–)P(–) sibling (Supplemental Figure 2, A–C). In contrast to 2D monolayer culture, 3D EHTs provide a more physiological environment and allow for concurrent biomechanical and electrophysiological characterization of cardiomyocytes. Linear tissue constructs facilitated the concurrent measurement of longitudinal conduction velocity and contractile performance(Figure 3A). Western blots of EHTs showed that R451G EHTs contained significantly lower amounts of desmoplakin compared with WT EHTs (Figure 3C), mimicking patient protein expression patterns (40.0% ± 10.3% decrease, P < 0.05). However, there were no overt morphological differences induced by the R451G mutation compared with WT EHTs (Figure 3B). Using a ratiometric fluorescent calcium reporter (Fura-2), calcium transients were measured in EHTs. No significant differences in the calcium handling properties were observed (Figure 3D). Next, we assessed action potential propagation through the EHT. We found no significant change in the conduction velocity between EHTs made with iPSCs expressing R451G mutant or WT desmoplakin (12.21 ± 1.456 cm/s vs. 9.356 ± 1.525 cm/s; Figure 3E). In order to verify that conduction was happening due to propagation through gap junctions, we treated our constructs with the gap junction blocker carbenoxolone and saw a corresponding 37.9% decrease in conduction velocity in both WT and mutant EHTs (Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 3. Engineered heart tissues from patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells exhibit reduced levels of desmoplakin.

(A) Engineered heart tissues (EHTs) were created by differentiating cardiomyocytes from patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and seeding cells into decellularized porcine myocardial slices. Constructs were used to assess contractility and electrical conduction velocity. (B) EHTs were generated using cardiomyocytes differentiated from G(+)P(+) patient III-36 and G(–)P(–) sibling III-35, denoted as EHTWT/R451G and EHTWT/WT, respectively. Bright-field images of EHTs show similar matrix compaction and morphology between the 2 types. Scale bar: 1 mm. (C) Representative immunoblot of desmoplakin (DSP) protein levels in EHTs shows substantial loss in the patient-derived tissue, which was statistically significant when quantified across several samples (*P < 0.05 for 2-tailed unpaired t test; n = 5 WT and n = 7 R451G). (D) Ca2+ transients collected from EHTWT/R451G and EHTWT/WT showed no differences between the 2 tissue types. (E) Measurements of longitudinal conduction velocity in EHTs showed no differences between EHTWT/R451G and EHTWT/WT (unpaired t test; n = 7 and 8 respectively). (F) Protein levels of connexin-43 (Cx43) and phosphorylated (Ser368) Cx43 in EHTs normalized to sarcomeric actin reveals significantly reduced Cx43 and significantly elevated levels of phosphorylated Cx43 in EHTWT/R451G (*P < 0.05 for 2-tailed unpaired t test, n = 3). (G) Representative force transients collected simultaneously with above Ca2+ transients reveal a delayed time to peak force in EHTWT/R451G. (H) Maximal force produced by EHTs. (I) Time from stimulus to maximal force. (J) Time elapsed from point of maximal force to 50% relaxation (RT50). ***P < 0.001 for 2-tailed unpaired t test with Bonferroni correction (n = 16 EHTWT/WT and n = 8 EHTWT/R451G). Error bars represent SEM.

In addition to conduction velocity, we assessed the total and phosphorylated levels of connexin-43 in both WT and mutant EHTs. Notably, mutant EHTs exhibited higher levels of phosphorylated connexin-43 at Ser368 compared with WT EHTs, despite a significant reduction in total connexin-43 protein (Figure 3F). Phosphorylation of Ser368 in connexin-43 has been implicated in marking the gap junction for degradation via the ubiquitin proteolytic system, which could explain the decrease in overall connexin-43 levels (15).

We next assessed potential changes in mechanical properties of the tissues. Sarcomeres are longitudinally linked to the cell membrane via intermediate filament connections, which terminate at desmosomal plaques. Thus, we reasoned that destabilized desmosomes could lead to impaired contractile dynamics. Interestingly, we observed a significant increase in the time to peak contraction in the mutant EHTs compared with WT (0.1853 ± 0.0034 s WT vs. 0.2165 ± 0.0051 s R451G, P < 0.0001), without a corresponding difference in peak force (304.8 ± 41.47 μN WT vs. 330 ± 64.53 μN R451G, P = 0.7110) or time to 50% relaxation (0.1168 ± 0.0028 s vs. 0.123 ± 0.0036 s in WT vs. R451G, P = 0.2006, respectively; Figure 3, G–J).

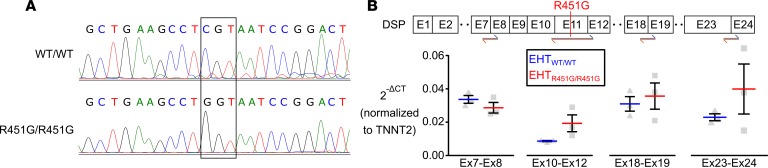

DSP mRNA levels are not reduced in homozygous R451G EHTs.

After recapitulating reduced desmoplakin levels in patient EHTs, we then investigated whether the protein loss was a result of lowered levels of mRNA transcript. In order to eliminate possible confounding secondary genetic factors, we utilized CRISPR/Cas9 to produce a potentially novel cell line homozygous for DSP R451G (R451G/R451G), derived from a commercially available (Coriell Institute for Medical Research) healthy control line (WT/WT, Figure 4A). RT-qPCR was performed on 14-day-old EHTs made with either R451G/R451G or isogenic WT/WT cardiomyocytes to probe for any differences in DSP transcripts. Primers targeted regions upstream of the R451G mutation, flanking the mutation, and downstream of the mutation. Expression levels of DSP mRNA were not significantly different between the two cell lines at any of the targeted regions (Figure 4B). This suggests that the mutation does not result in altered processing of DSP mRNA.

Figure 4. EHTs homozygous for R451G maintain normal levels of DSP mRNA.

(A) Genotyping of the control cell line (WT/WT) and the same cell line after CRISPR/Cas9 manipulation to introduce the DSP R451G mutation (ENST00000379802.8; c.1596CGT>GGT; Chr. 6:7568521, GRCh38.p12) at both alleles (R451G/R451G). (B) RT-qPCR was performed on engineered heart tissues formed from WT/WT and R451G/R451G cardiomyocytes in order to probe for DSP mRNA abundance. Several different primer pairs covering different exon junctions indicate that similar levels of DSP mRNA were expressed in both cell lines and that the introduction of c.1596CGT>GGT did not affect mRNA stability or result in alternative splicing (2-tailed unpaired t test with Bonferroni correction; n = 3). Blue and orange arrows represent regions targeted by forward and reverse primer pairs. Cycle thresholds were normalized to TNNT2 (cardiac troponin T).

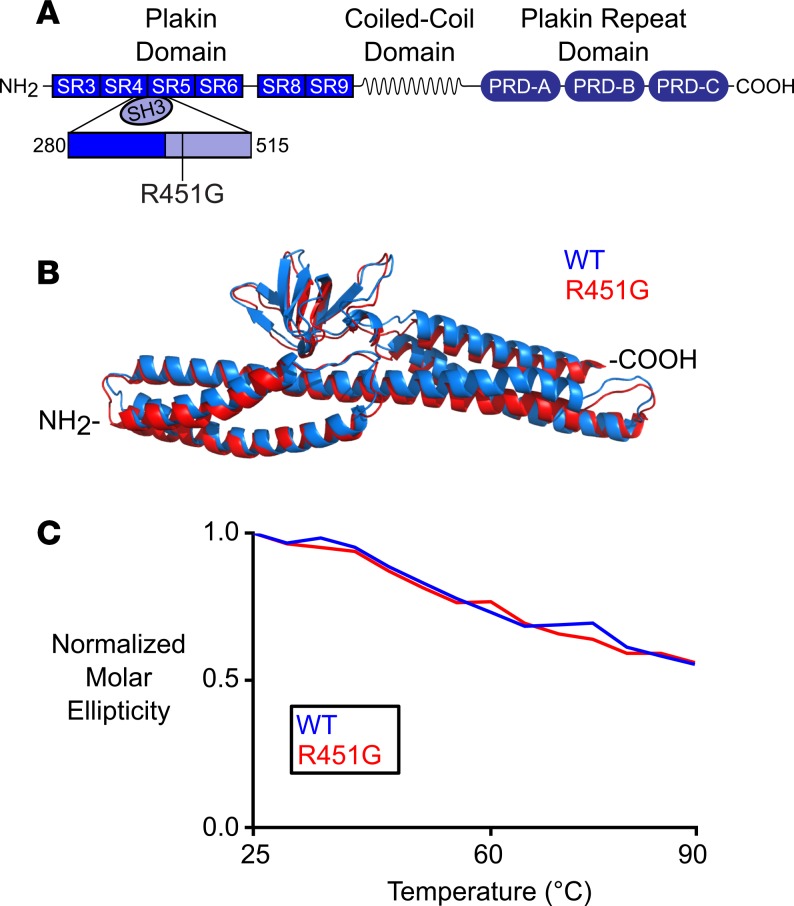

The R451G mutation does not overtly affect the structure or stability of desmoplakin.

With immunofluorescence analysis of a patient sample and EHT evidence indicating a loss of desmoplakin protein in the absence of depressed mRNA levels, we hypothesized that the R451G variant destabilizes the protein and allows increased degradation. In order to test this hypothesis, we turned to in silico modeling and biophysical structural analysis of the WT and mutant protein. Desmoplakin is a modular protein with 3 distinct regions (Figure 5A and ref. 16). The NH2-terminal third of the protein is composed of 6 α-helical spectrin repeats (SRs) and a Src homology 3 (SH3) domain. The middle portion of desmoplakin consists of a coiled-coil rod domain necessary for homodimerization, and the COOH-terminus contains 3 plakin repeat domains. The R451G variant maps to the SH3 domain, which is a known hotspot of ACM-associated mutations. 24% of pathological desmoplakin variants map to a region spanning approximately 200 amino acids within the NH2-terminus of the protein (4, 17, 18, 19, 20). However, circular dichroism experiments did not reveal any significant differences in either helical content or global protein stability between the WT and R451G constructs (Figure 5C). In addition, molecular dynamic (MD) simulations show no gross structural deviations between the WT and mutant protein (Figure 5B). A recent report by Daday et al. found the SH3 domain to remain correctly folded, despite applied forces large enough to destabilize other domains in desmoplakin (21). It is therefore not entirely surprising that desmoplakin remains macroscopically unchanged, despite a single residue substitution (21). We conclude that global protein structure stability is unaffected by the introduction of a glycine at position 451 of desmoplakin.

Figure 5. Glycine substitution at residue 451 results in no overt structural defects in desmoplakin.

(A) Schematic of desmoplakin showing the location of the mutated residue (R451G). The mutation occurs near the NH2-terminus region, which is responsible for interacting with the armadillo proteins of the desmosome. (B) Overlaid structural models of WT desmoplakin and desmoplakin with the R451G mutation after a 60-ns MD simulation. (C) Circular dichroism at 222 nm, normalized to 20°C for WT and R451G desmoplakin. As temperature was increased, both proteins showed similar degradation profiles.

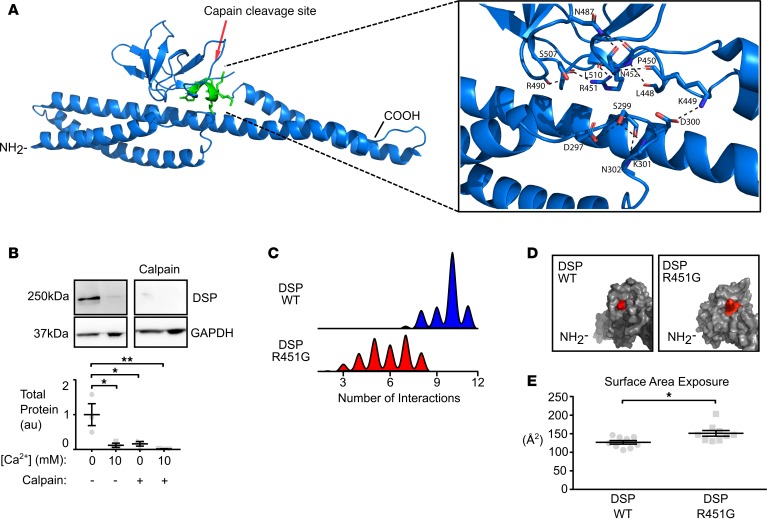

R451G desmoplakin is more sensitive to calpain-mediated degradation.

We next investigated more regulated means of protein destabilization that could lead to loss of desmoplakin protein at the intercalated disc. It has previously been shown that a missense mutation in plakophilin-2 leads to increased degradation by calpain, a calcium-dependent protease (22). We tested the hypothesis that desmoplakin is also a target for calpain-mediated degradation. Healthy human donor heart lysates exposed to exogenous calpain showed a complete loss of full-length endogenous desmoplakin compared with lysates with no treatment (Figure 6B). In addition, simply increasing the exogenous calcium levels significantly reduced full-length desmoplakin levels, presumably by activation of endogenously expressed calpain present in the myocardial lysate (Figure 6B). These data suggest that desmoplakin is indeed a target for calpain-mediated degradation.

Figure 6. Increased exposure of a calpain target site on desmoplakin due to a glycine substitution at residue 451.

(A) Ribbon model of desmoplakin showing location of affected calpain site (resides 447–451). Inset shows intramolecular interactions surrounding the putative calpain site. (B) Immunoblots of lysates from a donor control heart (OSU 294050) for changes in desmoplakin levels following the addition of exogenous Ca2+ or calpain. Addition of 10 mM Ca2+ over endogenous levels results in significant degradation of desmoplakin. Addition of exogenous calpain further reduced levels of desmoplakin at both endogenous levels and increased levels of Ca2+ (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 for 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; n = 3). (C) Histogram of the number of noncovalent interactions surrounding the calpain site, calculated from molecular dynamic simulations of WT desmoplakin (blue) and R451G desmoplakin (red). R451G produced a clear reduction in the average number of noncovalent interactions surrounding the calpain site, possibly increasing solvent accessibility degradation rate. (D) Surface model of desmoplakin showing the exposure of the affected calpain site in WT desmoplakin (left) and R451G desmoplakin (right). Red represents the exposed surface of calpain site residues. (E) Average exposed surface area of the calpain site over the length of the simulation (*P < 0.05, 2-tailed unpaired t test; n = 8). Error bars represent SEM.

To assess where calpain may target desmoplakin, we performed in silico analysis using publicly available prediction algorithms (GSP-CCD 1.0 and calpcleave; refs. 23, 24). These algorithms predicted 14 calpain target sites within the NH2-terminus of desmoplakin. We further limited our search to sites that were (a) expected to be targeted with both prediction algorithms, (b) within 7 Å of the mutation hotspot area, and (c) solvent exposed. With these criteria, only 2 sites remained, at positions 449 and 455. Although these sites are quite near each other in sequence and reside in the same loop, we focused our attention on the 449 site, due to it being a better fit for calpain targeting and the more solvent exposed of the 2 sites (Figure 6A). Within 7 Å of this site, there exist 11 intraresidue hydrogen bonds or electrostatic interactions, based on the x-ray structure (ref. 25 and Figure 6A). These noncovalent interactions constitute a 3-loop region, which functions to hold the putative calpain target site close to the SH3 domain and a loop of a neighboring SR. In an MD simulation of 100 ns, WT desmoplakin maintained, on average, 9.18 of these noncovalent bonds. In contrast, simulations on the R451G variant have only 5.83 bonds (Figure 6C). In addition, there is a wider distribution of bonds present in R451G, which may suggest increased flexibility. Thus, the putative calpain target site is not as tightly tethered to the rest of the molecule in the R451G mutant. This finding is recapitulated in examination of exposed surface area for residues 447–451; the introduction of the glycine at position 451 significantly increased the exposed surface area of that region compared with WT (Figure 6, D and E). These simulations suggest that the R451G mutation causes the putative 449 calpain target site to be hyperavailable for protease activity.

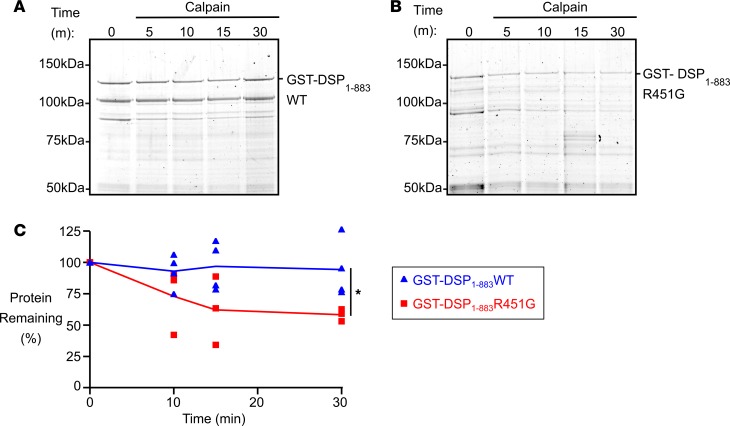

To test the MD prediction that the R451G mutation increases susceptibility of desmoplakin to calpain, we performed calpain assays using recombinant desmoplakin (amino acids 1–883) WT and mutant proteins. WT desmoplakin was stable even in the presence of calpain and 10 mM calcium (Figure 7A). In comparison, the R451G protein showed increased degradation after 10 minutes and significant loss of protein after 30-minute exposure to calpain and calcium (Figure 7, B and C). Mutant desmoplakin exhibited markedly faster degradation compared with WT. 40% of the R451G desmoplakin was lost in the first 30 minutes compared with minimal loss of the WT protein. These results, in conjunction with the MD data, support our hypothesis that the main molecular consequence of the R451G mutation is to increase calpain target site exposure and subsequently promote desmoplakin degradation.

Figure 7. Decreased stability of recombinant desmoplakin NH2-terminus with R451G mutation.

(A) A recombinant glutathione-S-transferase–tagged desmoplakin fragment consisting of the first 883 amino acids (GST-DSP1–883WT) was bacterially expressed and purified. After the fragment was incubated with calpain for 5-, 10-, 15-, or 30-minute intervals, degradation products were separated via SDS-PAGE and visualized by staining with Sypro Ruby. Very little degradation was observed. (B) The same experiment was repeated with a fragment containing the R451G amino acid substitution (GST-DSP1–883R451G). This gel shows substantial decrease of the intact fragment over time as it is exposed to calpain. (C) Quantification of gel images across repeated experiments reveals a significant increase in calpain-mediated degradation of the mutant R451G recombinant DSP protein relative to WT (*P < 0.05 for 2-tailed unpaired t test at 30-minute time point; GST-DSP1–883WT n = 4; GST-DSP1–883R451G n = 3). Error bars represent SEM.

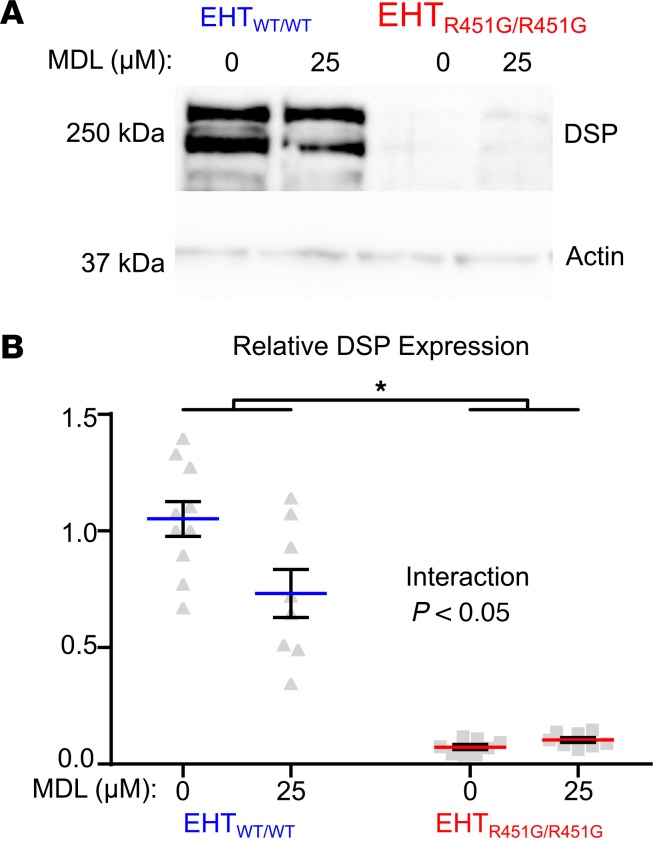

EHTs expressing mutant desmoplakin respond differently to calpain inhibition.

We next sought to demonstrate directly that lower desmoplakin abundance in EHTs expressing desmoplakin R451G is due to enhanced calpain-mediated degradation. Desmoplakin protein abundance was measured in EHTs made from R451G/R451G or control cells, with and without 72-hour treatment with the calpain inhibitor MDL-28170. Analysis of desmoplakin protein levels with 2-way ANOVA revealed a significant interaction between expression of desmoplakin R451G and the presence of calpain inhibitor, meaning that the effect of MDL-28170 on desmoplakin protein levels depended on genotype (Figure 8). Specifically, MDL-28170 had the effect of decreasing desmoplakin in control EHTs, while levels were unchanged in EHTs expressing only desmoplakin R451G. Thus, calpain inhibition raised desmoplakin protein levels in R451G/R451G EHTs relative to control. These results are supportive of a mechanism whereby DSP R451G affects protein stability, resulting in diminished abundance of the desmoplakin in spite of normal transcript levels.

Figure 8. Calpain inhibition results in partial rescue of desmoplakin levels in homozygous DSP R451G engineered heart tissues.

(A) Engineered heart tissues were incubated with 25 μM of the calpain inhibitor MDL-28170(MDL) or a vehicle control (DMSO) for 72 hours and then probed for desmoplakin protein levels. Loading across gels was normalized by sarcomeric actin. (Gel images are representative of PGP1 MDL n = 10; PGP1 DMSO, n = 8; HO35 MDL, n = 8; HO35 DMSO, n = 8). (B) Quantification of immunoblot showing significant interaction between genotype and drug treatment (P < 0.05) as well as significant loss of DSP between genotype (*P < 0.05) and drug treatment for 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. While desmoplakin levels in WT/WT EHTs were significantly decreased in samples exposed to MDL, this decrease was not observed in R451G/R451G EHTs.

Pathogenic ACM-linked mutants are predicted to have varying degrees of calpain susceptibility.

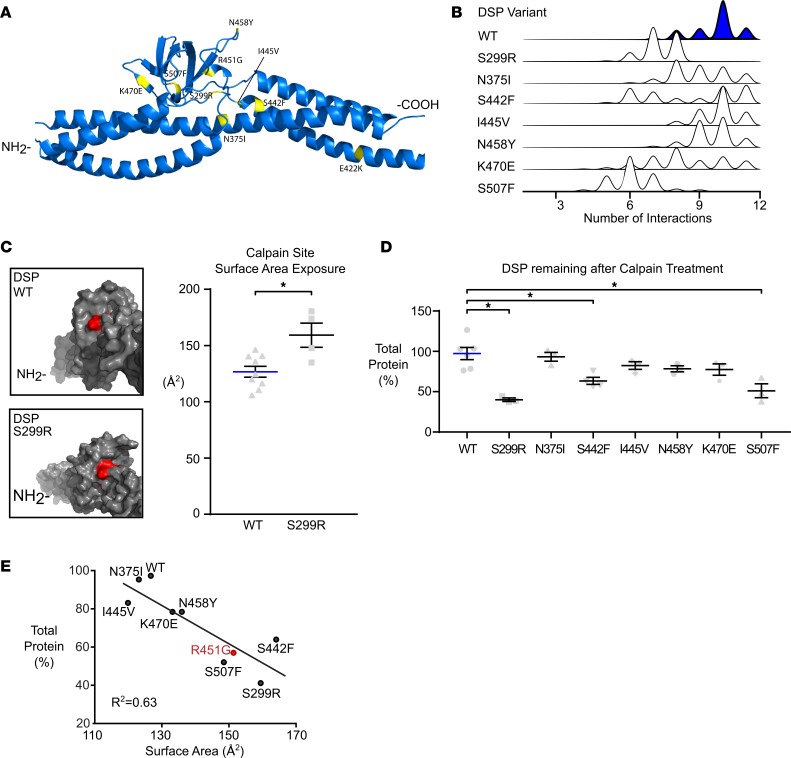

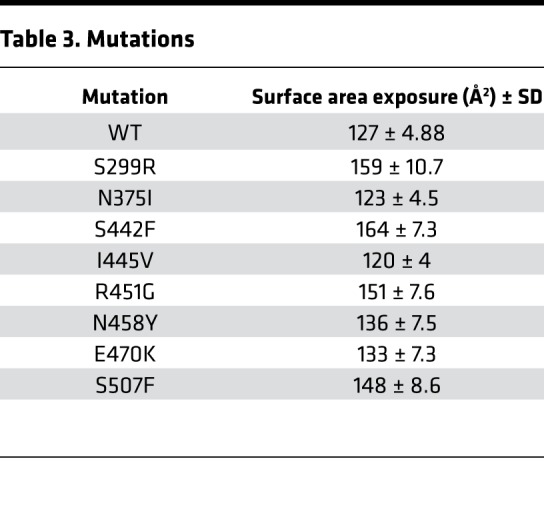

The R451G mutation occurs in a reported hotspot region of desmoplakin for ACM-linked variants (residues 280–515; Figure 9A). To see if this was the primary pathomechanism of other mutations in desmoplakin, we conducted similar predictive MD simulations on S299R, N375I, S442F, I445V, N458Y, K470E, and S507F. Simulations on 4 of the variants (N375I, I445V, N458Y, and K470E) mimic WT in both the number of interactions and surface area exposure (Figure 9, B and C, and Table 3). However, MD simulations of 3 other variants (S299R, S442F, and S507F) show both a reduced number of intermolecular interactions and an increase in the exposed surface area of the putative calpain target site (Figure 9, B and C, and Table 3). This led us to predict that S299R, S442F, and S507F would have increased susceptibility to calpain degradation.

Figure 9. Increased calpain degradation is common to other ACM-linked mutations in DSP.

(A) Model showing the location of 7 other ACM-linked desmoplakin mutations in relation to the R451G variant. Together, these mutations constitute a potential hotspot with shared molecular pathology. (B) Molecular dynamic simulations were run on these 7 additional ACM-linked mutations, and the number of intramolecular interactions around the calpain target site were calculated. Histograms showing the frequency of intramolecular interactions reveal a variety of mutation-associated changes, including reduced interactions for 3 mutants in particular (S299R, S442F, and S507F). (C) Models of desmoplakin showing the surface exposure of the affected calpain site (red) suggest that exposure in S299R desmoplakin is greater than for the WT structure. This predicted increase was statistically significant when examined across several repeat simulations (*P < 0.05, 2-tailed t test, n = 9 WT and n = 4 S299R). (D) Each of the 7 hotspot mutations was recombinantly expressed in DSP NH2-terminal fragments, purified, and incubated with calpain and Ca2+ for 30 minutes. Total protein remaining was determined for each mutation. S299R, S442F, and S507F each showed significant degradation relative to WT fragment over the same interval (*P < 0.05 for 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; WT n = 3; variants n = 3). Error bars represent SEM. (E) In order to test the predictive ability of the molecular dynamic simulations, regression analysis was performed on predicted calpain site surface area exposure and the percentage desmoplakin remaining after calpain treatment for each variant and WT. The 2 quantities were significantly correlated (R2 = 0.63, P < 0.05, linear regression analysis).

Table 3. Mutations.

Using a recombinant calpain assay, the 3 variants, S299R, S442F, and S507F, were found to degrade more rapidly and completely compared with the other mutants. Degradation rates for N375I, I445V, N458Y, and K470E variants were not significantly different from WT (Figure 9D). Thus, our results suggest that a subset of ACM-associated missense mutations within this hotspot region of desmoplakin act primarily through destabilizing molecular interactions that protect calpain target sites. The significant correlation (P < 0.05) between MD simulation parameters (exposed surface area of the calpain target site and number of intramolecular interactions) and in vitro biochemical properties (total protein remaining following calpain degradation and rate of degradation) validates the in silico predictions of calpain vulnerability (Figure 9E).

Discussion

Truncating desmoplakin mutations have been linked to a biventricular or predominantly left ventricular presentation of ACM, while missense desmoplakin mutations have proven unpredictable in terms of the affected chamber. Here, we present evidence for the first time to our knowledge that some desmoplakin missense variants mimic truncating alleles by introducing pathological vulnerability to calpain proteolysis and subsequent desmoplakin insufficiency. Furthermore, the subset of 4 calpain-vulnerable missense mutations we have identified share a biventricular ACM phenotype reminiscent of that seen for truncating mutations. In addition to revealing a potentially novel mechanism for desmoplakin variant pathogenicity, our study supports the idea that detailed biophysical understanding of mutational consequences can clarify genotype-phenotype relationships in ACM.

Care was taken in this study to align clinical, cellular, molecular, and genetic information in an unbroken chain of evidence to establish the pathogenicity of DSP R451G and its associated mechanism. A large ACM family provided conclusive data on the clinical phenotype and penetrance of this mutation. The observed deficiency of desmoplakin at the intercalated discs of patient tissue was recapitulated in myocardial tissue engineered from the iPSC line of an affected patient. A genetically engineered cell line homozygous for desmoplakin R451G confirmed dramatic desmoplakin loss in spite of normal levels of DSP transcript. Molecular dynamic predictions of enhanced calpain target site exposure in R451G desmoplakin were supported by significantly accelerated degradation with in vitro experiments. Calpain inhibition in EHTs expressing exclusively desmoplakin R451G showed a partial restoration of desmoplakin levels relative to control. These results document clear risk for patients carrying DSP R451G and suggest possible avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Additional questions about cell- and organ-level disease mechanisms in ACM remain, but our work does provide insights in this vein. The early phenotypes evident in patient-derived EHTs were somewhat surprising. While these EHTs recapitulated the loss of desmoplakin and connexin-43, we did not see the expected change in electrical propagation. Numerical simulations have shown that a 50% loss in gap junction conductance leads to only modest changes in conduction velocity (26), hence the observed decrease in connexin-43 may not be sufficient to induce impaired conduction. This is in line with another study, which reported arrhythmogenic potential in an ACM model system in spite of normal conduction velocity (27). EHTs expressing mutant desmoplakin exhibited slower force development compared with EHTs expressing WT desmoplakin. This is in agreement with evidence that localized regions of dyskinesia represent an early disease marker (28).

In addition to R451G, we investigated several other known pathogenic missense desmoplakin mutations (S299R, N375I, S422F, I445V, N458Y, K470E, and S507F) to see if they presented with a similar pathomechanism and resultant phenotype. Although 3 seemed to function similarly to R451G, 2 of the other variants (N458Y and K470E) were predicted not to cause any change to the putative calpain site (447–451). Work by others has shown that in fact the N458Y mutation alters desmoplakin function in an alternate way (possibly by weakening EB-1–binding interactions; ref. 13). In that study, human keratinocytes expressing these variants showed no decrease in the amount of expressed desmoplakin compared with WT controls. It appears as though variants, even within close proximity, can give rise to distinct molecular and clinical pathologies (29).

Perturbations to normal calpain-mediated degradation may be a common ACM mechanism, not limited to mutations in desmoplakin. Kirchner et al. presented evidence that a missense mutation in plakophilin-2 leads to increased degradation through calpain (22). Although this mutation appeared in a patient who met the 2010 ARVC task force criteria, linkage of the mutation to the ARVC phenotype was called into question by some due to the small size of the family in that study (22). Our work lends support to the conclusions of Kirchner et al. by demonstrating a similar mechanism in a very large kindred of sufficient size to provide unambiguous statistical linkage. Together, the two studies point to increased calpain-mediated proteolytic degradation as a primary disease mechanism for a subset of ACM patients and suggest that calpain should be targeted in research for novel therapies.

Other findings presented here further highlight the need for treatment strategies that match the diverse underlying molecular pathologies associated with ACM. Immunofluorescence imaging of cardiac tissue from an R451G patient autopsy showed no decrease in plakoglobin levels at the intercalated discs, even in a late stage with severe myocyte disarray, adipogenesis, and fibrosis (Figures 1 and 2). This conflicts with previous reports that loss of plakoglobin from the intercalated disc is a universal feature of ACM-linked desmosomal mutations (30). Our observations, together with similar findings in a mouse model of ACM (31), suggest that nuclear localization of plakoglobin and consequential aberrant Wnt/β-catenin signaling are not a necessary condition for biventricular ACM presentation. Rather, that mechanism may dominate in an alternate subset of ACM mutations. This seems to be the case in work by Asimaki et al., who found that SB216763, an inhibitor of GSK3β and thus activator of the canonical Wnt pathway, was able to correct protein mislocalization in a zebrafish model expressing mutant plakoglobin (JUP 2057del2; ref. 32). SB216763 has also shown efficacy in models expressing selected ACM-associated mutations to PKP2 or DSG2 (33). Importantly, each of these mutations were demonstrated to trigger plakoglobin mislocalization, suggesting overall that GSK3β inhibition therapy may be uniquely suited to mutations having this shared phenotype (33). This heterogeneity of molecular pathologies, including the possible susceptibility to degradation by calpain that we have uncovered, should be taken into account when exploring and testing treatment strategies for ACM.

Whole-exome sequencing of cardiomyopathy patients commonly reveals variants of unknown significance (34). A persistent clinical challenge is the differentiation between a true disease-causing mutation and one of many harmless variants. Recent work showed that 16% of healthy individuals harbor a single nucleotide polymorphism in one of the desmosomal genes (35). Current computational tools based on heuristic interpretation, such as SIFT or PolyPhen2, often mischaracterize the pathogenicity of unknown variants. For example, a meta-analysis showed that, of 209 pathogenic variants clearly linked to clinical ACM, Poly-Phen2 classified 41 of them as benign (36). While genetic linkage analysis is an effective way to classify variants by pathogenicity, it is not always feasible due to the difficulty of assembling a large kindred necessary for sufficient statistical power. Our approach, using bilateral in silico and in vitro modeling aimed at elucidating primary molecular pathomechanisms may ultimately address limitations posed by existing methods, resulting in more accurate predictions of pathogenicity for variants of unknown significance.

Foremost among the questions raised by this work is the need to identify a means of blocking calpain-mediated desmoplakin degradation with greater specificity. A calpain inhibitor, such as MDL-28170, appears to have wide-spread effects on cardiomyocyte function, such that it actually decreases desmoplakin in control cells. In desmoplakin R451G EHTs, it appears that nonspecific desmoplakin loss (as observed in control cells) was balanced by increased desmoplakin levels from lowered calpain-mediated degradation. Hence, MDL-28170 treatment resulted in only a modest relative restoration of desmoplakin levels in EHTs expressing desmoplakin R451G rather than an absolute increase. It is clear that future therapeutic strategies must interfere with calpain-desmoplakin interactions with high specificity.

The nuclear localization, if any, of desmoplakin cleavage products promoted by R451G was not considered in this study. Literature has shown that cleavage products of mutant junctophilin-2 can translocate to the nucleus, where they effect transcription (37). Our measurements of protein levels and localization did not show evidence of cleavage products translocating to the nucleus, but it is possible that some degradation products were not recognized by the antibodies used.

Another area of future work lies in developing clearer connections between clinical disease and in vitro phenotypes in iPSC-derived EHTs. Desmoplakin R451G EHTs did not exhibit any arrhythmogenic markers, such as decreased conduction velocity, or other pathological features, such as lipid droplet deposition or increased apoptosis. Other studies using human iPSCs to model ACM have failed to observe decreases in conduction velocity and only observed differences in action potential shape and presence of lipid droplet after concerted attempts to induce metabolic maturation (27, 38, 39). It therefore seems that improved metabolic maturation will be a prerequisite to observing clear functional effects of desmoplakin loss in our EHT system.

In summary, we have presented evidence that specific missense desmoplakin variants cause ACM characterized by prominent left ventricle involvement, fibrosis, and sudden death. Further, we have presented evidence that the primary effect of DSP R451G is increased susceptibility to proteolytic degradation by calpain, leading to desmoplakin insufficiency. The use of in silico simulation tools to quantify aberrant molecular behavior triggered by this mutation made it possible to identify other mutations linked to ACM that function through the same mechanism.

Methods

Clinical analysis and genetic linkage.

Whole-exome sequencing was conducted on proband samples (III-28). Following identification of the R451G mutation in desmoplakin, additional participating individuals submitted saliva samples, which underwent targeted sequencing focused at identifying the R451G variant in desmoplakin. A sample of patient genomic DNA was used to amplify exon 11 of the DSP gene by PCR using the following conditions: denaturation at 96°C for 2 minutes followed by 35 cycles of 30 seconds at 96°C, 30 seconds at 55°C, and 40 seconds at 72°C. Sanger sequencing was carried out on the products of this reaction on an Applied Biosystems 3730xL DNA Analyzer using Applied Biosystems Big Dye chemistries. ACM phenotypes were explored through medical record, history and autopsy data reviews. Linkage analysis was conducted using LINKAGE (40). The frequencies for alleles 1 and 2 were 0.804 and 0.196, as informed by the occurrence rate in the pedigree. A conservative disease penetrance of 0.5 was used, but our data suggests that the actual penetrance may be closer to 0.9 (14 of 15 mutation carriers older than 60 years of age expressed at least 1 ACM phenotype).

Procurement of human heart samples.

Heart sample harboring the desmoplakin R451G variant was obtained from patients III-26 and III-28 during autopsy. Nonfailing donor heart samples were obtained in collaboration with the Lifeline of Ohio Organ Procurement program from an organ donor without diagnosed heart failure whose heart was not suitable for transplantation. The donor heart was removed and immediately submersed in ice-cold cardioplegic solution containing 110 mM NaCl, 16 mM KCl, 16 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaHCO3, and 0.5 mM CaCl2. Tissues were either snap frozen or prepared for histological analysis, as discussed below. Biopsies from the free wall of the left and right ventricles were used in this study.

Histology and immunofluorescence.

Following fixation in formalin and paraffin embedding, thin sections from individual III-28 were stained with H&E and Masson’s trichrome. Histology analysis was performed using an Olympus BX40 light microscope with tilting binocular head. Photomicrographs were taken using the Diagnostic Instruments SPOT RT-SE Digital Camera system.

Immunofluorescence was performed on paraffin-embedded nonfailing donor hearts and biopsies from individual III-26 using standard protocols (41, 42). Prepared sections were imaged at a magnification of ×40 with a Zeiss 780 confocal fluorescent microscope. Colocalization analysis was completed using a custom MATLAB script following the Mander’s correlation coefficient method (43).

In silico calpain prediction.

Calpain target sites were predicted using GPS-CCD and calpcleave (23, 44). The 449 site was deemed the most likely cut site due to the likelihood of calpain to cleave, the proximity to the mutation hotspot, and solvent accessibility.

Computational modeling of WT and mutant desmoplakin.

Computational modeling was done using the human WT desmoplakin Protein Data Bank number 3R6N (25). The desmoplakin S299R, N375I, S442F, I445V, R451G, N458Y, K470E, and S507F mutation models were generated with the “swap residue” command in the computer program YASARA and allowed to equilibrate for at least 60 ns in explicit solvent at 310 °K, 150 mM NaCl, as previously described (45, 46). All hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions within 7 Å of the putative calpain target site in the original structure were surveyed every 25 ns, and the data were tabulated using YASARA. Cutoff distances for H-bonds was set to 3.5 Å and electrostatic interactions to 5 Å. A snapshot of each mutant was generated every 10 ns in YASARA, and the exposed surface area of residues 447–451 was calculated for each time point using Pymol (23). Calculations and statistics were performed in R v3.4.0, and data were plotted using ggplot2 (24).

Site-directed mutagenesis and recombinant protein production.

The NH2-terminus of human desmoplakin (amino acids 1–883; Addgene plasmid 32227) was directionally cloned into the pGex-4T1 vector (primers are listed in Supplemental Table 1) (47). The S299R, N375I, S442F, I445V, R451G, N458Y, K470E, and S507F mutations were individually introduced into the WT desmoplakin1–883 using the QuikChange Site-directed mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Introduction of each mutation was confirmed via sequencing. WT and mutant desmoplakin1–883 proteins were produced in bacteria as GST-fusion proteins using the pGEX-4T1 vector system according to established methods (42).

Circular dichroism.

Circular dichroism was obtained using a 3-mm quartz cuvette on a JASCO J-810 spectropolarimeter in 5°C increments from 25°C to 90°C. Experiments were completed in triplicate, using 1–3 μM protein in PBS, pH 8.0. Circular dichroism spectra were taken from 200 to 300 nm.

Calpain assays.

Two types of calpain assays were performed: type 1, using human heart lysates, and type 2, using recombinant affinity purified protein (48–51). For type 1, donor human heart tissue was homogenized with a 10 mM Tris HCl–0.32 M sucrose buffer followed by centrifugation. Lysates were diluted to 6 mg/mL with homogenization buffer and an equal volume of assay buffer (40 mM Tris HCl, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT) with and without 10 mM CaCl2 and with and without calpain (MilliporeSigma, C6108). Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes, quenched, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot.

For type 2, 25 μg purified recombinant protein was diluted in assay buffer, with 10 mM CaCl2 and calpain. Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes; 5 μg protein was removed at each time point, quenched, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by staining with Sypro Ruby total protein stain according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification of the total amount of protein remaining and the rate of degradation was calculated via densitometry obtained from ImageJ software (NIH). The rate of protein degradation was determined via the slope of the best-fit linear line. Values for at least 3 independent replicates were averaged for each desmoplakin1–883 protein.

iPSCs and EHTs.

Human iPSC lines were generated from a family member with the R451G mutation and no clinically diagnosable phenotype (III-35) and an unaffected family member with no mutation in desmoplakin (III-36). Blood was collected in accordance with the Yale and Stanford Institutional Review board. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated and then reprogrammed to iPSCs via the Sedai virus (CytoTune-iPS 2.0 Sendai Reprogramming Kits, Invitrogen) by Joseph C. Wu’s group at the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute, Stanford, California, USA. iPSCs were maintained on mouse embryonic fibroblast layers in human embryonic stem cell medium (ThermoFisher Scientific) (20% Knockout Serum Replacement, 1% glucose, 1% NEAA, 55 μM β-mercaptoethanol in DMEM/F12 basal medium containing bFGF 10 ng/ml) at 5% CO2 and 37°C. Cells were stained for pluripotency markers OCT4, SSEA-4, NANOG, TRA-1-60, and alkaline phosphatase (Supplemental Figure 2A). Karyotyping demonstrated stable chromosomal integrity in iPSC lines (Supplemental Figure 2B). An additional healthy control cell line was purchased from Coriell Institute for Medical Research (GM23338). Genetic modification was conducted on GM23338 hiPSCs to generate a homozygous R451G desmoplakin mutant line. More details are available in the Supplemental Methods.

Prior to differentiation, iPSCs were cultured on Matrigel-coated plates (BD Biosciences). Cells were maintained in mTeSR-1 media (StemCell Technologies) until they reached confluency. Once confluent, cells underwent cardiac differentiation as described previously (52). Briefly, cells were cultured in RPMI with B27 minus insulin and 20 μM CHIR99021 (Selleck Chemicals). After 24 hours, the media were replaced with fresh RPMI with B27 minus insulin. Forty-eight hours after this change, half the media were replaced with RPMI with B27 minus insulin and 5 μM Wnt Inhibitor IWP4 (Stemgent). From day 9 onward, the cells were incubated with RPMI with B27. Media were replaced every other day with fresh media. Only wells with beating clusters visible by day 10 were used for experiments.

EHTs were constructed via previously published methods outlined by Schwan et al. (52). In brief, porcine hearts were dissected and blocks of the left ventricular free wall were removed. Blocks were cryosectioned into slices parallel to the fiber direction to a thickness of 150 μm. The slices were incubated in a lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, 0.1% w/v EDTA, pH 7.4) for 2 hours before being attached to PTFE clips. Tissues were incubated in sodium dodecyl sulfate (0.5% w/v in PBS) for 40 minutes with gentle agitation. Tissues were washed 3 times in PBS before being incubated in DMEM + 10% FBS with ×1 Penicillin-Streptomycin (ThermoFisher Scientific) overnight. Cardiomyocytes were dissociated via incubation with Accutase (ThermoFisher Scientific) and seeded onto the scaffold at a density of 1.67 million cells per scaffold. EHTs were cultured for 2 weeks under electrical stimulation using a custom-built bioreactor before mechanical characterization was conducted.

Mechanical testing was performed on a custom-built setup using a force transducer (WPI KG-7) and length control via micro manipulators (Siskiyou). Tissues were tested in Tyrode’s solution (140 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 25 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, and 1.8 mM CaCl; pH adjusted to 7.3.) Calcium transients were measured using the ratiometric dye Fura-2 (MilliporeSigma). Loading of the dye was achieved using Tyrode’s solution with 17 μg/ml Fura-2 AM, 0.2% Pluronic F127, and 0.5% Cremophor EL (all from Millipore Sigma). Tissues were incubated with the Fura-2 solution for 20 minutes at room temperature and then washed with fresh Tyrode’s for 10 minutes at 37° C. The selected region was excited with a rapidly alternating sequence of 340/380 light and the response centered at 510 nm was collected by a photomultiplier tube. Custom MATLAB postprocessing routines separated the interleaved excitation response signals and computed a final ratiometric response. Conduction velocity was measured by tracking the calcium activation time, as the tissue was locally stimulated using a small bipolar electrode. As this point stimulus was moved further from the measurement region, the measured calcium upstroke was progressively delayed in time. Conduction velocity was determined as the slope of line between distance moved and upstroke delay. Contraction force characteristics, including time from stimulus to peak force, time from peak force to 50% relaxation, and magnitude of peak force were extracted from force transducer recordings.

Individual snap-frozen EHTs were homogenized in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.8, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaN3, 120 mM NaCl, 2% SDS, 1% β-mercaptoethanol lysis buffer with protease inhibitor. Lysates were analyzed via SDS-PAGE and Western blot. Total desmoplakin protein was normalized to the loading control (sarcomeric actin) and calculated as a fold change compared with the WT EHTs.

For RT-qPCR experiments, snap-frozen EHTs were homogenized in Trizol in order to isolate total RNA, and cDNA was synthesized using the iSCript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). 10 ng cDNA was used for quantitative PCR using SYBR green mix (Bio-Rad) in a total reaction volume of 15 μL. PCR was conducted on the C1000 Cfx96 Touch Real-Time PCR. Expression levels were calculated according to the ΔCT method normalized to cTnt mRNA levels. Complete primers can be found in the Supplemental Methods.

Calpain inhibition experiments were conducted via incubation of tissues for 72 hours in 25 μM MDL-28170 (MilliporeSigma) dissolved in DMSO. After incubation, EHTs were collected and homogenized for desmoplakin protein analysis.

Antibodies.

Antibodies used include N-cadherin (1:500; Pierce, 33-3900), desmoplakin (1:400 [immunofluorescence], Abcam, ab14418; 1:2000 [Western blotting], Abcam ab71690 and ab109445), plakoglobin (1:500; Abcam, ab15153), connexin-43 (1:500; Abcam, ab11370), GAPDH (1:5000; MilliporeSigma, G8795), sarcomeric actin (1:2000; MilliporeSigma, A2066), and phospho-connexin-43 Ser368 (MilliporeSigma, AB3841; 1:2000).

Statistics.

Reported whole-cell data are represented by the mean and SEM. Groups of 2 were compared with the unpaired 2-tailed Student’s t test with a Bonferroni post-hoc correction applied where noted. Multiple comparisons were done with 1- or 2-way ANOVA. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Study approval.

All protocols and consent forms were prepared in accordance with and approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board. The studies on human heart tissue were performed under the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, with oversight by and approval of the Institutional Review Boards at Yale University and The Ohio State University (protocols HIC1005006865 and 2012H0197, respectively).

Author contributions

RN, HM, NP, DLJ, YQ, NW, MAA, and SGC designed the research studies. RN, HM, TA, XL, JP, TLS, PJB, MR, and YR conducted experiments. NT, CJS, NP, YCL, SPH, TJB, and DLJ collected and analyzed clinical data. RN, HM, TA, MR, YQ, NW, MAA, and SGC performed analysis of experimental data. CES performed genetic programming of iPSCs. PMLJ provided research materials. RN, HM, NP, DLJ, YQ, NW, MAA, and SGC wrote and edited the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the NIH (1R01HL131940 to YQ, HL116778 to MAA), the National Science Foundation (REU CHE-1757874 and RUI MCB-1607024 to NW), the Department of Defense (11959515 to YQ), and the American Heart Association (17GRNT33410446 to SGC). We would also like to acknowledge funding provided by the Saving Tiny Hearts Society (to MAA) and a private research gift (to SGC).

Version 1. 06/13/2019

In-Press Preview

Version 2. 07/25/2019

Electronic publication

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: SGC is founder of and holds equity in Propria LLC. DLJ has received consulting fees from MyoKardia, Abbott, and Alnylam.

Copyright: © 2019 American Society for Clinical Investigation

Reference information: JCI Insight. 2019;4(14):e128643. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.128643.

Contributor Information

Ronald Ng, Email: ronald.ng@yale.edu.

Nikolaos Papoutsidakis, Email: nikolaos.papoutsidakis@yale.edu.

Taylor Albertelli, Email: alberttl@dukes.jmu.edu.

Nicole Tsai, Email: nicoletsaiy@gmail.com.

Xia Li, Email: xia.li@yale.edu.

Jinkyu Park, Email: jinkyu.park@yale.edu.

Tyler L. Stevens, Email: stevens.1006@buckeyemail.osu.edu.

Prameela J. Bobbili, Email: PrameelaJyothi.Bobbili@osumc.edu.

Muhammad Riaz, Email: muhammad.riaz@yale.edu.

Yongming Ren, Email: renyongming@gmail.com.

Christopher E. Stoddard, Email: stoddard@uchc.edu.

Paul M.L. Janssen, Email: janssen.10@osu.edu.

T. Jared Bunch, Email: jared.bunch@imail.org.

Stephen P. Hall, Email: Shall@palousemedical.com.

Ying-Chun Lo, Email: yingchun.lo.5@gmail.com.

Daniel L. Jacoby, Email: daniel.jacoby@yale.edu.

Yibing Qyang, Email: yibing.qyang@yale.edu.

Nathan Wright, Email: wrightnt@jmu.edu.

Maegen A. Ackermann, Email: Maegen.Ackermann@osumc.edu.

Stuart G. Campbell, Email: stuart.campbell@yale.edu.

References

- 1.Corrado D, Link MS, Calkins H. Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(1):61–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1509267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crossley GH, et al. The Heart Rhythm Society (HRS)/American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Expert Consensus Statement on the perioperative management of patients with implantable defibrillators, pacemakers and arrhythmia monitors: facilities and patient management this document was developed as a joint project with the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), and in collaboration with the American Heart Association (AHA), and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Heart Rhythm. 2011;8(7):1114–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corrado D, et al. Spectrum of clinicopathologic manifestations of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: a multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30(6):1512–1520. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00332-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sen-Chowdhry S, et al. Left-dominant arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy: an under-recognized clinical entity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(25):2175–2187. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sen-Chowdhry S, Syrris P, Ward D, Asimaki A, Sevdalis E, McKenna WJ. Clinical and genetic characterization of families with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy provides novel insights into patterns of disease expression. Circulation. 2007;115(13):1710–1720. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.660241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhonsale A, et al. Impact of genotype on clinical course in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy-associated mutation carriers. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(14):847–855. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.López-Ayala JM, et al. Desmoplakin truncations and arrhythmogenic left ventricular cardiomyopathy: characterizing a phenotype. Europace. 2014;16(12):1838–1846. doi: 10.1093/europace/euu128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauce B, et al. Clinical profile of four families with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy caused by dominant desmoplakin mutations. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(16):1666–1675. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castelletti S, et al. Desmoplakin missense and non-missense mutations in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: Genotype-phenotype correlation. Int J Cardiol. 2017;249:268–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alcalde M, et al. Stop-gain mutations in PKP2 are associated with a later age of onset of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fressart V, et al. Desmosomal gene analysis in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy: spectrum of mutations and clinical impact in practice. Europace. 2010;12(6):861–868. doi: 10.1093/europace/euq104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rasmussen TB, et al. Protein expression studies of desmoplakin mutations in cardiomyopathy patients reveal different molecular disease mechanisms. Clin Genet. 2013;84(1):20–30. doi: 10.1111/cge.12056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel DM, Dubash AD, Kreitzer G, Green KJ. Disease mutations in desmoplakin inhibit Cx43 membrane targeting mediated by desmoplakin-EB1 interactions. J Cell Biol. 2014;206(6):779–797. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201312110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eloff BC, Lerner DL, Yamada KA, Schuessler RB, Saffitz JE, Rosenbaum DS. High resolution optical mapping reveals conduction slowing in connexin43 deficient mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;51(4):681–690. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(01)00341-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smyth JW, et al. A 14-3-3 mode-1 binding motif initiates gap junction internalization during acute cardiac ischemia. Traffic. 2014;15(6):684–699. doi: 10.1111/tra.12169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green KJ, et al. Structure of the human desmoplakins. Implications for function in the desmosomal plaque. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(5):2603–2612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rampazzo A, et al. Mutation in human desmoplakin domain binding to plakoglobin causes a dominant form of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71(5):1200–1206. doi: 10.1086/344208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan BY, et al. Shared desmosome gene findings in early and late onset arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2010;3(6):663–673. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9224-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.den Haan AD, et al. Comprehensive desmosome mutation analysis in North Americans with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2(5):428–435. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.858217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basso C, et al. Ultrastructural evidence of intercalated disc remodelling in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: an electron microscopy investigation on endomyocardial biopsies. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(15):1847–1854. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daday C, Kolšek K, Gräter F. The mechano-sensing role of the unique SH3 insertion in plakin domains revealed by Molecular Dynamics simulations. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):11669. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11017-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirchner F, et al. Molecular insights into arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy caused by plakophilin-2 missense mutations. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2012;5(4):400–411. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.961854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. [No authors listed]. The {PyMOL} Molecular Graphics System Version~1.8. Schrödinger, LLC. https://www.schrodinger.com/pymol Accessed July 10, 2019.

- 24. Wickham H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi HJ, Weis WI. Crystal structure of a rigid four-spectrin-repeat fragment of the human desmoplakin plakin domain. J Mol Biol. 2011;409(5):800–812. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilders R. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: considerations from in silico experiments. Front Physiol. 2012;3:168. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blazeski A, Kostecki GM, Tung L. Engineered heart slices for electrophysiological and contractile studies. Biomaterials. 2015;55:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalal D, et al. Morphologic variants of familial arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy a genetics-magnetic resonance imaging correlation study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(15):1289–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ertz-Berger BR, et al. Changes in the chemical and dynamic properties of cardiac troponin T cause discrete cardiomyopathies in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(50):18219–18224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509181102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asimaki A, et al. A new diagnostic test for arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1075–1084. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lyon RC, et al. Connexin defects underlie arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in a novel mouse model. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(5):1134–1150. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asimaki A, et al. Identification of a new modulator of the intercalated disc in a zebrafish model of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(240):240ra74. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chelko SP, et al. Central role for GSK3β in the pathogenesis of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. JCI Insight. 2016;1(5):e85923. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.85923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Driest SL, Ommen SR, Tajik AJ, Gersh BJ, Ackerman MJ. Yield of genetic testing in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(6):739–744. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)61527-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kapplinger JD, et al. Distinguishing arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia-associated mutations from background genetic noise. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(23):2317–2327. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andreasen C, et al. New population-based exome data are questioning the pathogenicity of previously cardiomyopathy-associated genetic variants. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21(9):918–928. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo A, et al. E-C coupling structural protein junctophilin-2 encodes a stress-adaptive transcription regulator. Science. 2018;362(6421):eaan3303. doi: 10.1126/science.aan3303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caspi O, et al. Modeling of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy with human induced pluripotent stem cells. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2013;6(6):557–568. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim C, et al. Studying arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia with patient-specific iPSCs. Nature. 2013;494(7435):105–110. doi: 10.1038/nature11799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ott J. Estimation of the recombination fraction in human pedigrees: efficient computation of the likelihood for human linkage studies. Am J Hum Genet. 1974;26(5):588–597. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ackermann MA, et al. TGF-β1 affects cell-cell adhesion in the heart in an NCAM1-dependent mechanism. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2017;112:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu LR, et al. Deregulated Ca2+ cycling underlies the development of arrhythmia and heart disease due to mutant obscurin. Sci Adv. 2017;3(6):e1603081. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1603081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunn KW, Kamocka MM, McDonald JH. A practical guide to evaluating colocalization in biological microscopy. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2011;300(4):C723–C742. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00462.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Friedrich P, Tompa P, Farkas A. The calpain-system of Drosophila melanogaster: coming of age. Bioessays. 2004;26(10):1088–1096. doi: 10.1002/bies.20106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ackermann MA, et al. Novel obscurins mediate cardiomyocyte adhesion and size via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2017;111:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rudloff MW, Woosley AN, Wright NT. Biophysical characterization of naturally occurring titin M10 mutations. Protein Sci. 2015;24(6):946–955. doi: 10.1002/pro.2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Godsel LM, et al. Desmoplakin assembly dynamics in four dimensions: multiple phases differentially regulated by intermediate filaments and actin. J Cell Biol. 2005;171(6):1045–1059. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schafer DP, Jha S, Liu F, Akella T, McCullough LD, Rasband MN. Disruption of the axon initial segment cytoskeleton is a new mechanism for neuronal injury. J Neurosci. 2009;29(42):13242–13254. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3376-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith SA, et al. Dysfunction of the β2-spectrin-based pathway in human heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;310(11):H1583–H1591. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00875.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pfaff M, Du X, Ginsberg MH. Calpain cleavage of integrin beta cytoplasmic domains. FEBS Lett. 1999;460(1):17–22. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang CF, Huang YS. Calpain 2 activated through N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor signaling cleaves CPEB3 and abrogates CPEB3-repressed translation in neurons. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32(16):3321–3332. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00296-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwan J, et al. Anisotropic engineered heart tissue made from laser-cut decellularized myocardium. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32068. doi: 10.1038/srep32068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.