Abstract

Background

Disease burden estimates related to household air pollution (HAP) relied on cross-sectional data on cooking fuel, overlooking other important sources (e.g. heating) and temporal-regional variations of exposure in geographically diverse settings. We aimed to examine the trends and variations of for cooking and heating fuel use and ventilation in 500,000 adults recruited from 10 diverse localities of China.

Methods

At baseline (2004-08) and two subsequent resurveys (2008-14), participants of China Kadoorie Biobank, aged 30-79, reported their past and current fuel use for cooking and heating and the availability of cookstove ventilation. These were compared across regions, time periods, birth cohorts, and socio-demographic factors.

Results

During 1968-2014, the proportion of self-reported solid fuel use for cooking or heating decreased by two-thirds (from 84% to 27%), whereas those having complete kitchen ventilation tripled (from 19% to 66%). By 2014, despite a continuing downward trend, many in rural areas still used solid fuels for cooking (48%) and heating (72%), often without adequate ventilation (51%), in contrast to urban residents (all <5%). The large urban-rural inequalities in solid fuel use persisted across multiple generations and also varied by socioeconomic status, especially in rural areas.

Conclusions

Despite marked progress in fuel modernization in the last 50 years, substantial rural-urban inequalities remain in the study population, especially those who were older or of lower socioeconomic status. Uptake of cleaner heating fuel and ventilation has been slow. More proactive and targeted strategies are needed to expedite universal access to clean energy for both cooking and heating.

Keywords: Household air pollution, solid fuel, cooking, heating, ventilation, China

1. Introduction

Globally about 2.7 billion individuals are currently exposed to high levels of household air pollution (HAP) due to their reliance on polluting and energy inefficient solid fuels (e.g. coal and biomass) for cooking, (Kurmi et al., 2008, Zhang and Smith, 2007, Pokhrel et al., 2015, IEA, 2015) In 2015, HAP accounted for an estimated 2.9 million premature deaths, most of which occurred in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including 0.6 million in China, (GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators, 2016) where 450 million individuals are still relying on solid fuels for cooking (IEA, 2016). These estimates were, however, largely based on national modelling data with inadequate empirical evidence to capture the large regional variation in HAP exposure and changes over time. (Bonjour et al., 2013)

Fuel use pattern has changed substantially in many fast-growing economies, including China. However, there is inadequate detailed inter-regional evidence on long-term trend and pattern of fuel use, particularly among population subgroups (e.g. by age and other socio-demographic characteristics). Several studies had attempted to examine the patterns of fuel use in China, (Duan et al., 2014, Chen et al., 2016, Liao et al., 2016) but were based on short-term observations and mostly examined cooking fuel use after 1990’s, with little information on heating fuel use and ownership of ventilated cookstoves, both of which contribute importantly to HAP exposure. Comprehensive assessment of contemporary and historical exposure to multiple sources of HAP is crucial to inform appropriate assessment of long-term health effects associated with HAP exposure and development of public health and environmental policies.

Using data from the China Kadoorie Biobank (CKB), an ongoing prospective cohort of 512,891 adults across ten diverse localities of China, (Chen et al., 2005, Chen et al., 2011) we examined the patterns of cooking and heating fuel use and ventilated cookstove ownership over time and compared them by region, birth cohort, and selected socio-demographic factors.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study participants

The design and methods of CKB have been described in detail elsewhere. (Chen et al., 2011, Chen et al., 2005) Briefly, 512,891 adults aged 30-79 years (mean 52 years; 59% female) were recruited in 2004-08 from ten localities (five rural counties [known by the name of the provinces]: Gansu, Henan, Hunan, Sichuan, Zhejiang, and five urban cities: Haikou, Harbin, Liuzhou, Qingdao, Suzhou [semi-urban]) across China, chosen from China’s nationally representative Disease Surveillance Points system (Yang et al., 1997) to represent a diverse range of socioeconomic levels, risk exposures and disease patterns. (Chen et al., 2011) At baseline, an interviewer-administered questionnaire collected information on demographic and socioeconomic status, lifestyle behaviors and medical history. Subsequently, two resurveys were undertaken in 2008 and 2013-14, involving 19,760 and 24,996 randomly selected surviving participants, respectively (see supplementary method 1 or visit http://www.ckbiobank.org for further details). (Chen et al., 2011) Ethical approval was obtained from relevant authorities in China and in the UK and all participants provided written informed consent.

2.2. Assessment of fuel use and cookstove ventilation

Throughout this study, fuels used for cooking and heating and cookstove ventilation were used as proxies for HAP exposure. At baseline, participants were asked to provide information relating to HAP exposures in each of their three most recent residences (‘baseline residence’—the residence at baseline, ‘penultimate residence’—the previous residence, ‘antepenultimate residence’—the residence before the penultimate) (see figure A1), including duration of residence, cooking frequency (daily, weekly, monthly, never/rarely cook, no kitchen), primary cooking fuel (gas, electricity, coal, wood, other) for those who reported cooking at least monthly, winter heating use (yes, no), primary heating fuel if appropriate (district heating, gas, electricity, coal, wood, other), and cookstove ventilation availability (whether there is/was a chimney or extractor attached to cookstove(s) owned: ‘complete’ for all stoves, ‘partial’ for some stoves, and ‘none’) for those with a kitchen. The same questions were repeated in subsequent resurveys assessing recent exposure (in the past 12 months) in the participants’ current residence. In most analyses, gas, electricity, and district heating (available in northern China only) were aggregated into ‘clean fuels’, as they are associated with lower emissions in the households. (Gordon et al., 2014)

Based on the information from the three most recent residences recalled at baseline (defined as the ‘informative recall period’, which could date back as far as birth), we estimated the lifelong fuel use and ventilation history (or as long as possible) for five birth cohorts in the study population (1939 or earlier, 1940-49, 1950-59, 1960-69, 1970 or later). We also derived composite indicators on long-term HAP exposure to identify participants who consistently used solid or clean fuels, or had none or complete cookstove ventilation in all three most recent residences.

2.3. Datasets used for specific analyses

Individuals (n=2,303) with a recall period greater than their age were excluded from main analyses, leaving 510,588 participants at baseline. We further excluded those who did not cook regularly (n=130,581), rather than including them in the unexposed group, for in China domestic cooking is predominantly done by females and such classification would distort the distribution of important gender-related socio-demographic characteristics (e.g. education) across exposure categories. Similarly, in the analyses on heating fuel we excluded all participants who had no heating in corresponding residences (baseline n=130,992), primarily those from Zhejiang (n=57,685), a coastal rural region, at baseline and first resurvey (where >99% participants reported that they did not use heating) and those from Haikou (n=29,632), situated in the tropical south where heating is not necessary. Lastly, we excluded those who reported using ‘other’ fuel for cooking (n=199) or heating (n=15). The final sample consisted of 377,280 participants for cooking-related, 290,280 for heating-related and 509,839 for ventilation-related analyses at baseline, with the corresponding numbers available for similar analyses on other time periods given in Figure A2.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Proportions (in percentages) of cooking and heating fuel type and cookstove ventilation availability at various residences were adjusted for age (5-year groups), gender and region structure of the CKB population as appropriate using direct standardization. They were then cross-tabulated by selected socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, regions, education level and household income), and were plotted in stacked area graphs over five periods of residence (antepenultimate, penultimate, and baseline, first and second resurveys), with the median and inter-quartile range of year started living in each residence (YSLmedian (IQR)) or year of participation in resurvey to indicate the period during which information on fuel use and ventilation availability in the study population was captured.

An age-at-risk analysis approach was used to examine the lifetime HAP exposure pattern by birth cohorts. First, total duration of exposure to each category of HAP was estimated by summing the reported number of years in each residence with that specific exposure. Then, the age period covering the duration of exposure was stratified into 5-year age bands from 0 to 79 years. The percentages of duration in each age band being exposed to each category of each HAP indicator were calculated adjusting for gender and region by direct standardization (see supplementary method 2). Finally, we plotted these percentages, stratifying for birth cohorts against age to examine the variation of lifetime exposure patterns across different generations. Estimates in the oldest age band of the participants born in 1939 or earlier (75-79 years) are likely to be unreliable due to small sample size (n=1,305) and were therefore excluded from these analyses.

As a sensitivity analysis, we restricted to participants who provided complete lifetime exposure data and to 14,691 participants who were interviewed at baseline and at the subsequent two resurveys. All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.3.

3. Results

Of the 510,588 participants with baseline data analyzed, the mean (SD) age was 51.6 (10.7) years, and the total recall period was 39.7 (14.5) years, with 80% of the information provided covering ≥70% of adulthood (≥15 years). By combining the baseline and the subsequent two resurveys (mean [SD] prospective period: 8.0 [0.8] years), the present study captured almost 50 years of fuel use and cookstove ventilation data between 1960’s and 2014 (see figure A1).

There were marked differences in the HAP indicators between rural and urban areas. At baseline, over 85% of rural residents reported using coal or wood for cooking or heating and only about 20% had ventilation for all cookstoves. In contrast, <10% used solid fuels for cooking and 75% had ventilation for all cookstoves in urban regions. While most urban residents used gas or electricity for cooking, almost a quarter still relied on solid fuels for heating, mainly in Qingdao (60% used coal) and in Suzhou (25% used wood), which includes a semi-urban study area (see figure A3). Users of solid fuels or unventilated cookstoves were relatively older, more likely to be female, and had lower level of education and income, except that coal use was associated with lower income in urban but not rural areas (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics by household air pollution exposures in rural and urban areas a.

| Characteristics | Cooking fuel b | Heating fuel c | Cookstove ventilation d | Overall e | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clean fuels | Coal | Wood | Clean fuels | Coal | Wood | Complete | Partial | None | N | |

| RURAL AREAS | ||||||||||

| No. of participants | 29,17 | 99,272 | 68,035 | 15,455 | 91,050 | 65,968 | 58,765 | 129,910 | 95,536 | 284,573 |

| Age (mean ± SD), year | 47.5 ± 9.8 | 50.9 ± 10.1 | 54.4 ± 10.6 | 47.9 ± 10.4 | 50.3 ± 10.4 | 51.7 ± 10.8 | 49.9 ± 10.4 | 50.8 ± 10.3 | 51.2 ± 10.7 | 50.9 ± 10.5 |

| Gender, % | ||||||||||

| Female | 14.2 | 51.0 | 34.8 | 8.8 | 52.7 | 38.5 | 20.3 | 45.9 | 33.8 | 166,397 |

| Male | 17.5 | 49.5 | 33.0 | 9.2 | 53.0 | 37.8 | 21.2 | 45.4 | 33.4 | 118,176 |

| Highest attained education, % | ||||||||||

| No formal | 9.2 | 46.6 | 44.2 | 5.4 | 49.9 | 44.7 | 17.1 | 46.0 | 36.9 | 67,942 |

| Primary | 14.5 | 51.1 | 34.4 | 7.4 | 52.9 | 39.7 | 18.8 | 47.1 | 34.0 | 118,924 |

| Middle school or above | 24.3 | 53.3 | 22.5 | 12.3 | 55.8 | 31.9 | 26.5 | 41.2 | 32.4 | 97,707 |

| Household income (yuan/year), % | ||||||||||

| <10,000 | 9.4 | 46.9 | 43.7 | 6.4 | 52.0 | 41.6 | 15.6 | 46.5 | 37.9 | 113,009 |

| 10,000-19,999 | 15.8 | 53.2 | 31.0 | 8.5 | 51.8 | 39.8 | 19.5 | 46.5 | 33.9 | 82,073 |

| ≥20,000 | 29.0 | 49.7 | 21.3 | 15.2 | 54.7 | 30.1 | 29.3 | 41.8 | 28.9 | 89,491 |

| URBAN AREAS | ||||||||||

| No. of participants | 164,248 | 1,915 | 13,634 | 88,766 | 24,480 | 4,561 | 168,302 | 32,035 | 25,290 | 226,015 |

| Age (mean ± SD), year | 51.9 ± 10.5 | 56.4 ± 11.0 | 56.8 ± 10.6 | 50.7 ± 11.0 | 54.8 ± 11.5 | 54.4 ± 10.8 | 51.9 ± 10.7 | 54.7 ± 11.0 | 53.0 ± 11.4 | 52.3 ± 10.9 |

| Gender, % | ||||||||||

| Female | 90.8 | 1.7 | 7.5 | 74.6 | 21.4 | 3.9 | 74.4 | 14.4 | 11.2 | 134,725 |

| Male | 90.9 | 1.4 | 7.7 | 76.3 | 20.0 | 3.7 | 74.9 | 13.9 | 11.2 | 91,290 |

| Highest attained education, % | ||||||||||

| No formal | 81.4 | 4.4 | 14.2 | 60.1 | 31.2 | 8.6 | 61.9 | 19.9 | 18.2 | 26,864 |

| Primary | 87.8 | 2.8 | 9.4 | 64.0 | 29.5 | 6.6 | 69.1 | 16.2 | 14.6 | 45,306 |

| Middle school or above | 95.6 | 1.2 | 3.3 | 78.6 | 18.4 | 3.0 | 80.1 | 11.3 | 8.5 | 153,845 |

| Household income (yuan/year), % | ||||||||||

| <10,000 | 78.8 | 3.8 | 17.4 | 62.7 | 30.1 | 7.3 | 56.0 | 22.2 | 21.8 | 30,730 |

| 10,000-19,999 | 88.6 | 2.0 | 9.4 | 70.4 | 24.5 | 5.0 | 68.2 | 16.9 | 14.9 | 66,085 |

| ≥20,000 | 95.6 | 0.7 | 3.7 | 80.5 | 17.0 | 2.4 | 82.0 | 11.7 | 6.3 | 129,200 |

Percentages and means are adjusted for age, gender and region where appropriate, χ2 p-value of all association <0.001 in binary logistic regression. Clean fuels include gas, electricity and district heating (for heating only); row percentage is displayed.

Participants who never/rarely cook or reported using ‘other’ fuel were excluded (nrural = 88,091; nurban = 45,218).

Participants from Haikou (n=29,631) and Zhejiang (n=57,685) where >99% participants reported no heating, and participants from other regions who reported no heating (nrural =52,518; nurban =78,474) or using ‘other’ heating fuel were further excluded (nrural = 1,897; nurban =103).

Participants who had no kitchen at baseline were excluded (nrural = 362; nurban = 388).

Overall number of participants at baseline, after excluding 2,303 participants whose recall period was greater than their age, total N = 510,588.

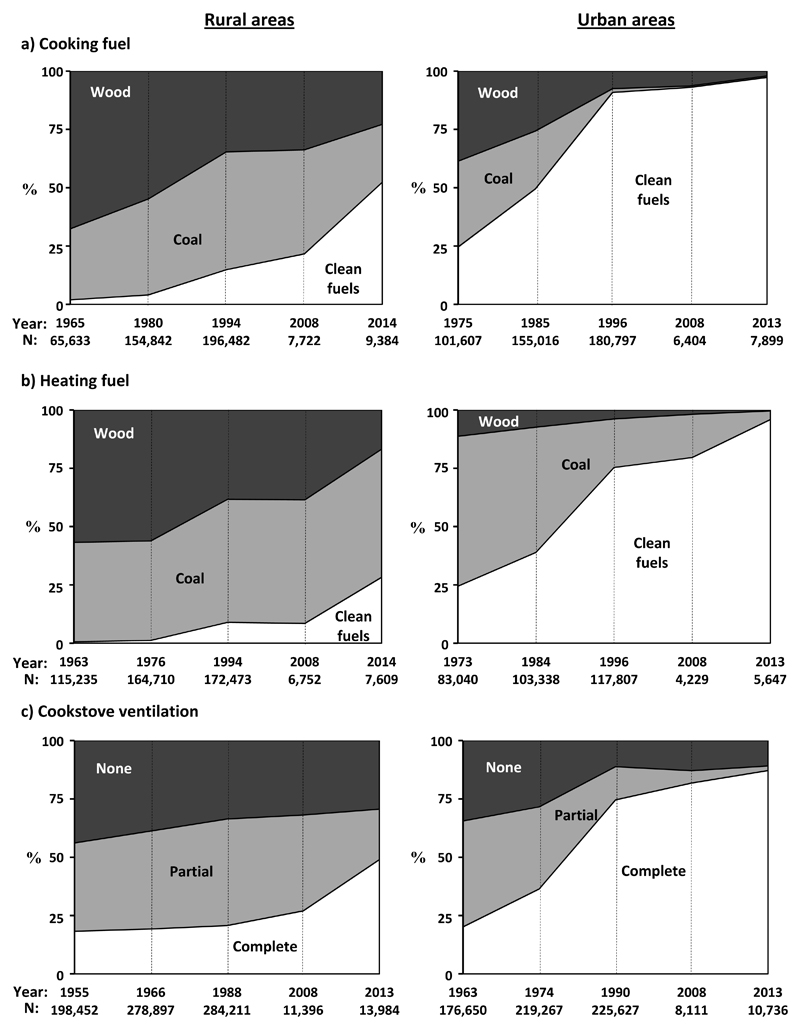

Coal and wood were the main cooking fuels in the antepenultimate residence of both rural (YSLmedian [IQR]): 1965 [1955-73], 98%) and urban (YSLmedian [IQR]: 1975 [1963-84], 74%) participants, but the urban residents adopted clean fuels more rapidly, with only 2.7% reporting always using solid fuels throughout the recall period (circa 1975-2008), as opposed to 85% among rural residents (circa 1965-2008). However, the changing pattern of clean fuel use as a primary fuel source during 2004-14 appeared to be more rapid in rural areas (Figures 1(a) and 2(a)). The pace of heating fuel modernization was much slower than that of cooking fuel. In rural areas, nearly all used solid fuels for heating in the 1960’s (antepenultimate residence YSLmedian [IQR]: 1963 [1954-71]), and >90% throughout the recall period, and still as high as 72% in 2013-14. Likewise, the majority of urban residents used solid fuels for heating in their antepenultimate residence (YSLmedian [IQR]: 1973 [1962-84]), but switched to clean fuel by the time of the second resurvey (2013-14) (Figures 1(b) and 2(b)). The long-term trends in ventilation broadly coincided with changes in cooking fuel, but the expansion of complete ventilation was slower than that of clean cooking fuel, especially in rural areas, where there was an accelerated rate of transition post-2008. In urban areas, however, the proportion of complete ventilation increased rapidly from 20% in the antepenultimate residence (YSLmedian [IQR]: 1974 [1963-84]) to >80% at the second resurvey (2013-14) (Figures 1(c) and 2(c)). The temporal pattern of types of cooking fuel and cookstove ventilation combined was consistent with that of cooking fuel. However, alongside the increase of clean fuel use, the proportion without ventilated cookstoves among clean fuel users has decreased from 37% to 9% in urban areas but has gone up from 18% to 29% in rural areas (see figure A4).

Figure 1. Temporal pattern of self-reported primary fuel type for a) cooking and b) heating; and c) presence of cookstove ventilation, in urban and rural areas.

Percentage estimates were adjusted for age, gender, and regions. X-axis labels are 1) median year started living in each of the three most recent residences recalled in baseline survey and the calendar year when 1st or 2nd resurvey was conducted; and 2) number of participants that provided information at respective time period/point. Clean fuels include gas, electricity and district heating (for heating only). Participants who never/rarely cooked, reported using ‘other’ fuel type, had no kitchen were excluded from (a); participants who had no heating or from Zhejiang and Haikou and those reported using ‘other’ fuel type were excluded from (b); participants who had no kitchen were excluded from (c).

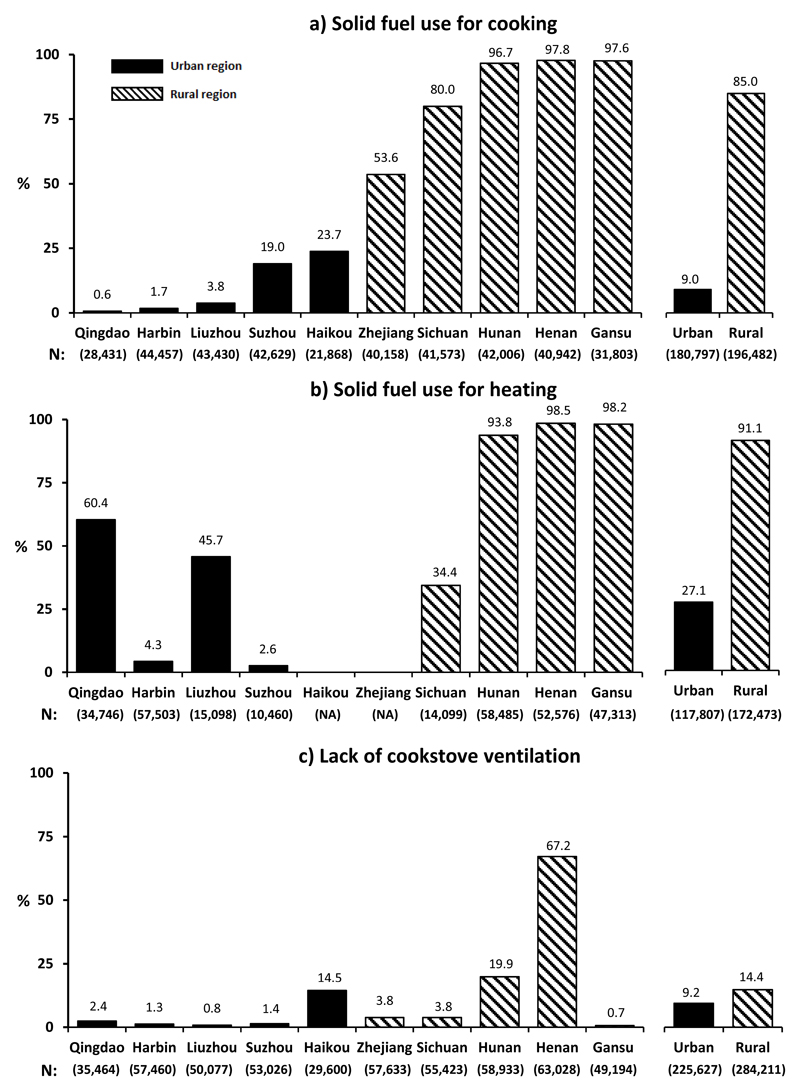

Figure 2. Regional variation of self-reported primary fuel type for a) cooking and b) heating; and c) lack of cookstove ventilation throughout the three most recent residences at baseline.

Long-term exposure was defined as the use of solid fuels or the absence of ventilated cookstoves in the three most recent residences. Percentage estimates were adjusted for age and gender. Regions are listed in descending order (from left to right) by the percentages of solid fuel use for cooking. Participants from Haikou and Zhejiang were excluded in (b).

Fuel transition was observed across participants with different socioeconomic background, but the change from solid to clean fuels during 1960’s to 2010’s was more rapid among those with high school or above education, or having the highest household income (≥35,000 yuan/year), and was more accentuated in urban areas. For illiterate rural residents and those with low household income (<10,000 yuan/year), there was a modest decrease in the proportion (-7.7 and -8.6 percentage points, respectively) with complete ventilation from 1970’s to 1990’s, but have since recovered thereafter (see figures A5-A8).

Considerable variation existed in temporal trends of HAP exposures across the ten localities, such that the site-specific rates of fuel transition or ventilation uptake differed not only in magnitude, but at times qualitatively from the overall picture. For example, in urban Qingdao a large proportion of participants reported to use coal for heating (60% in 2004-08 and 20% in 2013-14) despite the fact that gas or electricity was almost exclusively used as primary fuel for cooking during the same period. In contrast, in Suzhou (semi-urban) and Sichuan (rural), heating fuel was modernized more quickly than cooking fuel (see figures A9 and A10). In Gansu a downward trend was observed in the proportion of complete cookstove ventilation, which was contrary to the other four rural regions (see figure A11). The temporal trend of cooking fuel and cookstove ventilation in Suzhou (semi-urban) is more similar to other rural regions such as Zhejiang, which is a relatively affluent rural region, especially during the 1970’s to 1980’s (see figures A9(a), A9(h), A11(a) and A11(h)). Finally, over the past five decades the proportion reporting the use of heating increased, the majority of which was powered by electricity (data not shown). Of particular note, at the second resurvey (2013-14), 13% of the participants in Zhejiang reported to have heating (by clean fuels), but prior to that <1% had used heating in the three most recent residences at baseline or at the first resurvey.

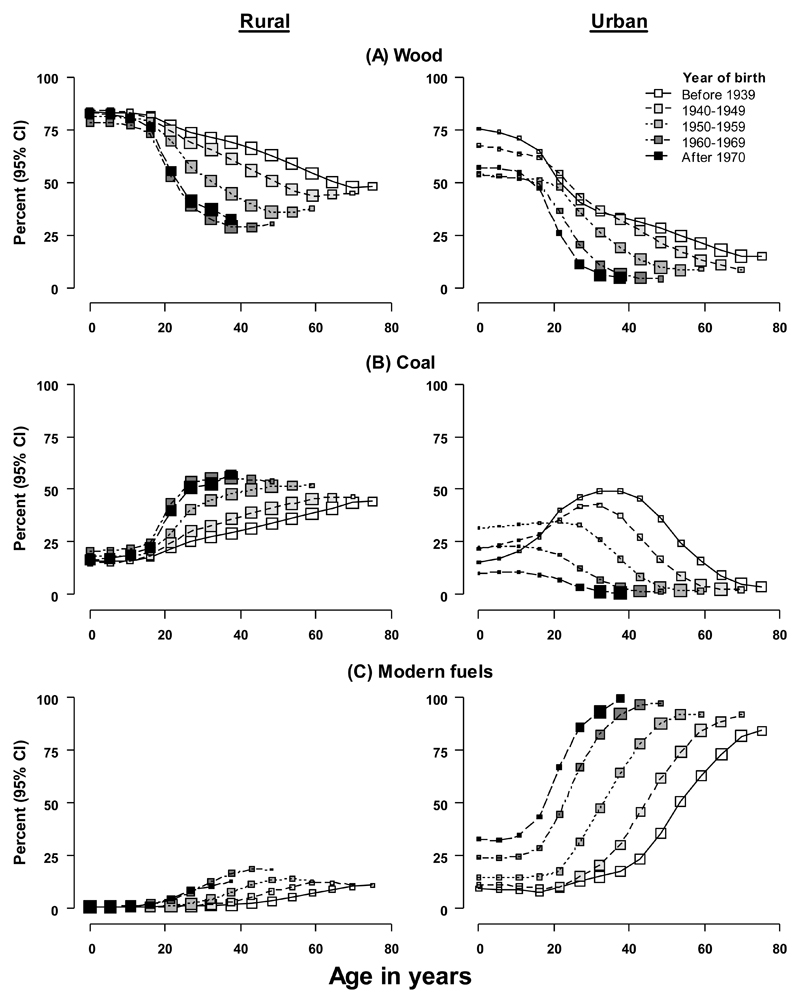

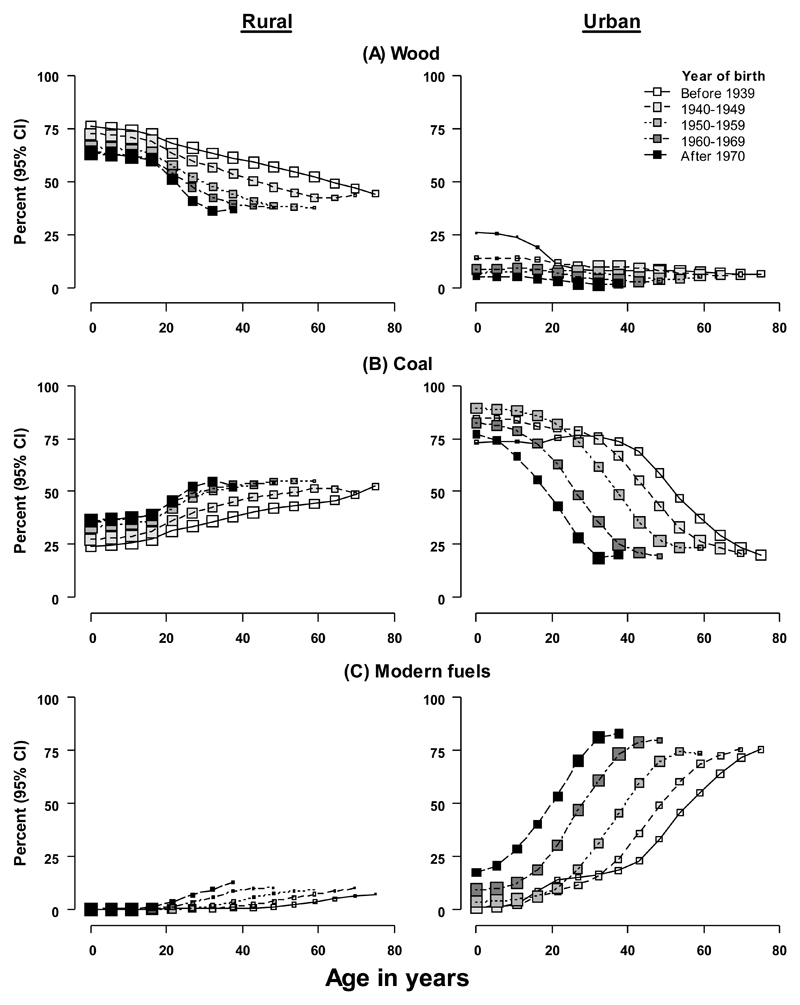

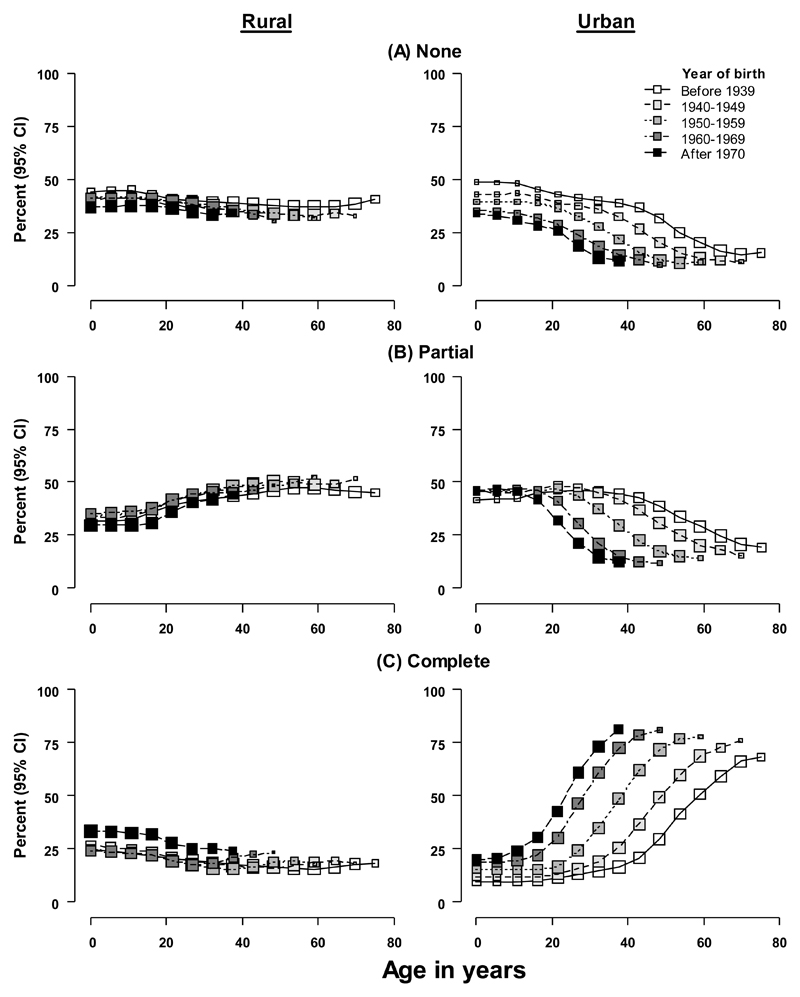

Overall, there were substantial differences across birth cohorts in both the rate of fuel transition and the age at which they changed residence and switched fuel. The younger generation moved away from solid fuels more rapidly than their older counterparts, and also at a younger age. Such intergenerational disparities widened over time in rural areas but were generally attenuated in urban areas as the older generation eventually switched fuels (Figures 3 and 4). As for cookstove ventilation, birth cohort differences were observed only in urban areas (Figure 5). Restricting to participants who provided lifetime exposure data at baseline and of the 14,961 participants who attended all three surveys showed highly consistent results (data not shown).

Figure 3. Adjusted percentage of length of age band exposed to specific cooking fuel by five birth cohorts in rural and urban areas.

Left panels: rural areas; right panels: urban areas. Percentage estimates were adjusted for gender and regions. Size of boxes is inversely proportional to the standard error of the respective age band; 95% CI are too narrow to be seen in most graphs. Clean fuels include gas and electricity. Note that the last box of each line (except for the one in ‘before 1939’, which was excluded due to the small sample size in this 75-79 age band) is the time point when the baseline survey was conducted (2004-08).

Figure 4. Adjusted percentage of length of age band exposed to specific heating fuel by five birth cohorts in rural and urban areas.

Left panels: rural areas; right panels: urban areas. Percentage estimates were adjusted for gender and regions. Size of boxes is inversely proportional to the standard error of the respective age band; 95% CI are too narrow to be seen in most graphs. Clean fuel includes gas, electricity and district heating. Note that the last box of each line (except for the one of ‘before 1939’, which was excluded due to the small sample size in this 75-79 age band) is the time point when the baseline survey was conducted (2004-08).

Figure 5. Adjusted percentage of length of age band with different degrees of cookstove ventilation by five birth cohorts in rural and urban areas.

Left panels: rural areas; right panels: urban areas. Percentage estimates were adjusted for gender and regions. Size of boxes is inversely proportional to the standard error of the respective age band; 95% CI are too narrow to be seen in most graphs. Ventilation is defined as the presence of chimney/ extractor on cookstove in possession, with three possible categories as shown. Note that the last box of each line (except for the one of ‘before 1939’, which was excluded due to the small sample size in this 75-79 age band) is the time point when the baseline survey was conducted (2004-08).

4. Discussion

In this comprehensive assessment of regional variation and long-term trends in main cooking and heating fuel use and cookstove ventilation in a large Chinese cohort, we found a clear rural-urban disparity, with rural areas lagging behind in household fuel transition during the past five decades. Moreover, the transition in cooking fuel began much earlier than that for heating fuel, and the rate was strongly influenced by socioeconomic status. There were also significant birth cohort differences in the pattern of fuel use.

Several nationwide surveys have previously examined the frequency and patterns of solid fuel use for cooking in China. Overall, they showed a clear shift from solid to clean fuels, with the recent nationwide surveys showing almost 50% of individuals in China still relying on solid fuel for cooking in 2010 and about 40% in 2012, (Duan et al., 2014, Chen et al., 2016) similar to the estimates obtained in our study, which was not designed to be nationally representative. A recent report based on data from periodic China Health and Nutrition Surveys (CHNS) has also examined the trends in cooking fuel in about 2,000 rural household from nine provinces between 1989 and 2011.(Liao et al., 2016) In the 9th five-year plan (1996-2000), the Chinese government began to prioritize modernization and commercialization of the rural energy sector; (The Government of the People’s Republic of China, 1995) by 2010-15 the national electricity grid had achieved complete coverage in rural areas. (National Energy Administration of the People’s Republic of China, 2014) Electricity price had become increasingly affordable through continuous national subsidy. It was against this backdrop of national policy changes that a rapid reduction of primary use of solid fuels for cooking among rural Chinese residents (from 75% to 35%) was observed.(Bonjour et al., 2013) A similar magnitude of change (from 85% to 48% during the similar time period) was seen among our rural participants, more of whom were recruited from less-developed rural localities compared with CHNS. The recent (during 2006-14) rapid rise in clean fuel use (mainly electricity but not gas) in rural CKB regions to some extent confirms the increasing accessibility and affordability of electricity in rural China. Although the fuel modernization between 2008 and 2013-14 in CKB was primarily in rural areas, the large differences in fuel use in the five urban localities should not be discounted. In the more developed urban localities (e.g. Harbin and Qingdao) almost all participants had gas or electricity as their primary cooking fuel, but in Haikou and Suzhou wood remained an important fuel source as many participants were living in semi-urban communities where there was an abundant local supply of firewood.

Both globally and in China, data on heating fuel use have been scarce. (Shen et al., 2015, World Health Organisation, 2016) The cross-sectional CEERHAPS study reported a smaller proportion of rural residents using solid fuels for heating (62% in 2012 versus 72% in CKB in 2013-14), and a much higher proportion among urban residents (23% versus 4%).(Duan et al., 2014) The discrepancy regarding urban areas may be due to the inclusion of several traditionally coal-reliant provinces (e.g. Shandong) in CEERHAPS where coal-fired heating is particularly common in cities. In CKB we also found that participants from Qingdao (the largest city in Shandong) had the highest proportion of coal users among all urban localities (62% in 2004-08) (Figure A10). To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to investigate the long-term trends in heating fuel use in China. During 2004-14, we saw increased coverage of home heating, mainly powered by electricity, in the central and coastal regions to the south of Huai River (Suzhou, Liuzhou, Sichuan and Zhejiang), probably due to the increasingly affordable and accessible electricity supply especially in rural areas,(National Energy Administration of the People's Republic of China, 2014) as reflected by the increasing expenditure on electricity.(National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2006-2010) Despite this, >75% rural residents in CKB still used solid fuels for heating in 2013-14, lagging behind urban residents by approximately 40 years. Meanwhile in Qingdao, amidst the recent rapid expansion of district heating coverage in the city (up to 89% in CKB in 2013-14; 82% in 2015 according to the city government (The People's Government of Hebei Province 2016), the share of coal use for heating fell substantially from 61% in 2004-08 to 11% in 2013-14. During the period of 1982-92 China distributed 130 million improved cookstoves under the National Improved Stove Program. (Smith et al., 1993) While these cookstoves could burn fuels more efficiently, chimneys were not always installed. (Sinton et al., 2004, Gordon et al., 2014) In our study, there was a relatively modest rate of ventilated cookstove uptake in rural areas during 1955-2008, but apparently a more rapid rise post-2008. Little published evidence on the distribution of ventilated cookstoves is available, but the recent rising trend may be related to the expansion of the commercial market and recent public-private initiatives promoting improved cookstoves in China. (The People's Government of Hebei Province 2016, World Bank, 2013, Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves, 2015) The trend was generally consistent with the switch to cleaner cooking fuels in our urban participants. In our rural participants, however, the proportion of clean fuel use without ventilation increased considerably as less people used solid fuels, possibly related to cost implications. (Shen et al., 2015) It is also possible that rural residents could switch to different types of clean fuels without the need for ventilation (e.g. unvented gas stove). Consistently, in our participants from Gansu (one of the poorest regions in China) the proportion of participants with complete ventilation decreased alongside increased use of clean cooking fuel, whereas participants in Zhejiang, a more affluent rural region, we observed there was a trend for adoption in parallel.

In CKB, the disparities of HAP exposures persisted trans-generationally both within and across rural and urban areas, highlighting important birth cohort differences in adoption of clean fuels and ventilation. In the context of the theory of diffusion, clean fuels and ventilated cookstoves could be considered as innovations in a traditional, solid fuel-reliant society. (Troncoso et al., 2007) As such, younger and more affluent individuals tend to be the early adopters, subsequently followed by most others and leaving behind a small number who are reluctant to change. (Troncoso et al., 2007, Rao and Kishore, 2010) Urban residents in CKB were younger and they moved house more frequently than rural residents (shorter mean recall period, 36 versus 43 years), so they might also have more opportunity to switch to clean fuel, as it often requires structural changes in the corresponding facilities and dwelling environment. Other societal factors such as faster rate of electric grid expansion, increasing availability and affordability of clean fuels and decreasing availability of solid fuels may also explain the quicker fuel or ventilation modernization trend in urban areas. (Shen et al., 2015)

The sequentially lower prevalence of early-life exposure in younger generations underlies the epidemiological transition of decreasing HAP-related disease burden in children, but the burden in rural elderly, many of whom continued to use solid fuels, might have proportionately increased as other traditional risk factors such as infectious diseases diminish. In the light of the rapidly changing pattern of exposure, a combination of direct exposure measurement, robust exposure classification and careful statistical modelling, and applied in a life course context, is needed for better exposure classification and a more reliable assessment of the long-term health effects.

The main strengths of this study lie in the scale and diversity of our participants, covering 0.5 million adults across 10 very different urban and rural localities of China. Moreover, we simultaneously examined three key determinants of HAP exposure (cooking, heating, and ventilation), and for the first time, explored the trans- and inter-generational disparities of HAP exposure that may be relevant for informing the changing disease patterns and future assessment of health risks associated with long-term HAP exposure. Our study also has limitations. First, we relied on self-reported data in constructing the historical evolution of HAP exposures. To minimize bias, we excluded all participants with potentially unreliable recall information and also undertook sensitivity analyses in participants with complete estimated lifetime exposure data, which showed highly consistent results with the main findings. Second, we have assessed only the primary fuel type or ventilation condition (one used or experienced most frequently and for the longest period) during each residence, which is subject to misclassification due to changes of fuel type or ventilation condition. Nevertheless, with the large sample size and diversity of the CKB, the time of house moving (and hence fuel change) was unlikely to be affected by systematic error. Furthermore, the temporal trends were formulated from proportions adjusting for age, gender and locality, allowing less biased comparisons across population subgroups. The trends were also highly consistent in the randomly selected resurvey subsample. Similar to the previous multi-region studies, we have no data on mixed use of fuels, which is common in rural areas where complete transition to clean fuels is difficult. (Peng et al., 2010, Liao et al., 2016) The trend of “switching” to clean fuels in China, as found in our study, therefore has to be interpreted with caution as it may be implying a relegation of solid fuels in the households rather than exclusive use of cleaner energy sources. Likewise, the patterns of composite indicators of long-term HAP exposure might have resulted in an underestimation of exposure due to “fuel and stove stacking” phenomenon. (Rehfuess et al., 2014) As parallel use of clean and solid fuels often result in HAP exposure similar to using solid fuels alone, (Clark et al., 2013) reliance on primary fuel type data may result in underestimation of the total exposure in the population.

5. Conclusions

In our study population, many rural communities remained solid fuel-reliant despite the rapid improvement in China over the past 50 years. We have identified the trans- and inter-generational disparity across rural and urban areas, and highlighted the under-recognized slower trends of modernization of heating fuel and ventilated cookstove ownership, as well as the substantial regional variation of such time trends. Household air pollution is a major challenge not only to global health but also poverty, gender equality and climate change. (Burki, 2011) Our findings highlight the urgency of region-specific strategies to address the prolonged inequalities across rural and urban areas and socioeconomic subgroups and to promote access to clean household energy in China. Beyond China, fuel modernization in many LMICs has been comparatively slow. (Bonjour et al., 2013) Further investigation to understand the potential drivers of the recent rapid transition in rural China and to evaluate the recent effort in promoting cheap and sustainable energy and large scale distribution of new-generation ventilated low-emission stoves (World Bank, 2013, Chen et al., 2014) could provide useful insights and strategies for other LMICs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The chief acknowledgment is to the participants, the project staff, and the China National Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and its regional offices for assisting with the fieldwork. We thank Judith Mackay in Hong Kong; Yu Wang, Gonghuan Yang, Zhengfu Qiang, Lin Feng, Maigeng Zhou, Wenhua Zhao, and Yan Zhang in China CDC; Lingzhi Kong, Xiucheng Yu, and Kun Li in the Chinese Ministry of Health; and Sarah Clark, Martin Radley, Mike Hill, Hongchao Pan, and Jill Boreham in the CTSU, Oxford, for assisting with the design, planning, organization, and conduct of the study.

Funding: The present study was supported by the UK Medical research Council: Global Challenges Research Fund – Foundation Award (MR/P025080/1). KHC is a recipient of the DPhil Scholarship from the Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford. The CKB baseline survey and the first re-survey were supported by the Kadoorie Charitable Foundation in Hong Kong. The long-term follow-up has been supported by the UK Wellcome Trust [grant numbers 202922/Z/16/Z, 104085/Z/14/Z, 088158/Z/09/Z] and grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant numbers 81390540, 81390541, 81390544] and from the National Key Research and Development Program of China [grant numbers 2016YFC0900500, 2016YFC0900501, 2016YFC0900504, 2016YFC1303904]. The British Heart Foundation, UK Medical Research Council and Cancer Research provide core funding to the Clinical Trial Service Unit and Epidemiological Studies Unit at Oxford University for the project.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests declaration:

The authors declare that they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

Members of the China Kadoorie Biobank collaborative group:

International Steering Committee: Junshi Chen, Zhengming Chen (PI), Rory Collins, Liming Li (PI), Richard Peto.

International Co-ordinating Centre, Oxford: Daniel Avery, Ruth Boxall, Derrick Bennett, Yumei Chang, Yiping Chen, Zhengming Chen, Robert Clarke, Huaidong Du, Simon Gilbert, Alex Hacker, Mike Hill, Michael Holmes, Andri Iona, Christiana Kartsonaki, Rene Kerosi, Ling Kong, Om Kurmi, Garry Lancaster, Sarah Lewington, Kuang Lin, John McDonnell, Iona Millwood, Qunhua Nie, Jayakrishnan Radhakrishnan, Sajjad Rafiq, Paul Ryder, Sam Sansome, Dan Schmidt, Paul Sherliker, Rajani Sohoni, Becky Stevens, Iain Turnbull, Robin Walters, Jenny Wang, Lin Wang, Neil Wright, Ling Yang, Xiaoming Yang.

National Co-ordinating Centre, Beijing: Zheng Bian, Yu Guo, Xiao Han, Can Hou, Jun Lv, Pei Pei, Shuzhen Qu, Yunlong Tan, Canqing Yu.

10 Regional Co-ordinating Centres:

Qingdao Qingdao CDC: Zengchang Pang, Ruqin Gao, Shanpeng Li, Shaojie Wang, Yongmei Liu, Ranran Du, Yajing Zang, Liang Cheng, Xiaocao Tian, Hua Zhang, Yaoming Zhai, Feng Ning, Xiaohui Sun, Feifei Li. Licang CDC: Silu Lv, Junzheng Wang, Wei Hou. Heilongjiang Provincial CDC: Mingyuan Zeng, Ge Jiang, Xue Zhou. Nangang CDC: Liqiu Yang, Hui He, Bo Yu, Yanjie Li, Qinai Xu,Quan Kang, Ziyan Guo. Hainan Provincial CDC: Dan Wang, Ximin Hu, Hongmei Wang, Jinyan Chen, Yan Fu, Zhenwang Fu, Xiaohuan Wang. Meilan CDC: Min Weng, Zhendong Guo, Shukuan Wu,Yilei Li, Huimei Li, Zhifang Fu. Jiangsu Provincial CDC: Ming Wu, Yonglin Zhou, Jinyi Zhou, Ran Tao, Jie Yang, Jian Su. Suzhou CDC:Fang liu, Jun Zhang, Yihe Hu, Yan Lu, , Liangcai Ma, Aiyu Tang, Shuo Zhang, Jianrong Jin, Jingchao Liu. Guangxi Provincial CDC: Zhenzhu Tang, Naying Chen, Ying Huang. Liuzhou CDC: Mingqiang Li, Jinhuai Meng, Rong Pan, Qilian Jiang, Jian Lan,Yun Liu, Liuping Wei, Liyuan Zhou, Ningyu Chen Ping Wang, Fanwen Meng, Yulu Qin,, Sisi Wang. Sichuan Provincial CDC: Xianping Wu, Ningmei Zhang, Xiaofang Chen,Weiwei Zhou. Pengzhou CDC: Guojin Luo, Jianguo Li, Xiaofang Chen, Xunfu Zhong, Jiaqiu Liu, Qiang Sun. Gansu Provincial CDC: Pengfei Ge, Xiaolan Ren, Caixia Dong. Maiji CDC: Hui Zhang, Enke Mao, Xiaoping Wang, Tao Wang, Xi zhang.Henan Provincial CDC: Ding Zhang, Gang Zhou, Shixian Feng, Liang Chang, Lei Fan. Huixian CDC: Yulian Gao, Tianyou He, Huarong Sun, Pan He, Chen Hu, Xukui Zhang, Huifang Wu, Pan He. Zhejiang Provincial CDC: Min Yu, Ruying Hu, Hao Wang. Tongxiang CDC: Yijian Qian, Chunmei Wang, Kaixu Xie, Lingli Chen, Yidan Zhang, Dongxia Pan, Qijun Gu. Hunan Provincial CDC: Yuelong Huang, Biyun Chen, Li Yin, , Huilin Liu, Zhongxi Fu, Qiaohua Xu. Liuyang CDC: Xin Xu, Hao Zhang, Huajun Long, Xianzhi Li, Libo Zhang, Zhe Qiu.

References

- Bonjour S, Adair-Rohani H, Wolf J, Bruce NG, Mehta S, Pruss-Ustun A, Lahiff M, Rehfuess EA, Mishra V, Smith KR. Solid fuel use for household cooking: country and regional estimates for 1980-2010. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121:784–90. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burki TK. Burning issues: tackling indoor air pollution. The Lancet. 2011;377:1559–1560. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60626-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Hu W, Feng Y, Sweeney S. Status and prospects of rural biogas development in China. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2014;39:679–685. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Shen H, Zhong Q, Chen H, Huang T, Liu J, Cheng H, Zeng EY, Smith KR, Tao S. Transition of household cookfuels in China from 2010 to 2012. Applied Energy. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Chen J, Collins R, Guo Y, Peto R, Wu F, Li L, China kadoorie biobank collaborative G China Kadoorie Biobank of 0.5 million people: survey methods, baseline characteristics and long-term follow-up. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:1652–66. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Lee L, Chen J, Collins R, Wu F, Guo Y, Linksted P, Peto R. Cohort profile: the Kadoorie Study of Chronic Disease in China (KSCDC) Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:1243–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark ML, Peel JL, Balakrishnan K, Breysse PN, Chillrud SN, Naeher LP, Rodes CE, Vette AF, Balbus JM. Health and household air pollution from solid fuel use: the need for improved exposure assessment. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121:1120–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1206429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan X, Jiang Y, Wang B, Zhao X, Shen G, Cao S, Huang N, Qian Y, Chen Y, Wang L. Household fuel use for cooking and heating in China: Results from the first Chinese Environmental Exposure-Related Human Activity Patterns Survey (CEERHAPS) Applied Energy. 2014;136:692–703. [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet. 2016;388:1659–1724. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves. China pilot projects & workshop set the stage for deeper collaboration. Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon SB, Bruce NG, Grigg J, Hibberd PL, Kurmi OP, Lam K-BH, Mortimer K, Asante KP, Balakrishnan K, Balmes J, Bar-Zeev N, et al. Respiratory risks from household air pollution in low and middle income countries. The Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:823–860. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70168-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2015. Paris, France: International Energy Agency; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2016. Paris, France: International Energy Agency; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kurmi OP, Semple S, Steiner M, Henderson GD, Ayres JG. Particulate matter exposure during domestic work in Nepal. Ann Occup Hyg. 2008;52:509–17. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/men026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao H, Tang X, Wei Y-M. Solid fuel use in rural China and its health effects. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2016;60:900–908. [Google Scholar]

- National bureau of statistics of china. China yearbook of rural household survey 2005-2010. Beijing: 2006–2010. [Google Scholar]

- National energy administration of the people's republic of china. The electricity-access challenge of 1.5million people have been resolved in 2013. National Energy Administration of the People's Republic of China; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Peng W, Hisham Z, Pan J. Household level fuel switching in rural Hubei. Energy for Sustainable Development. 2010;14:238–244. [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel AK, Bates MN, Acharya J, Valentiner-Branth P, Chandyo RK, Shrestha PS, Raut AK, Smith KR. PM2.5 in household kitchens of Bhaktapur, Nepal, using four different cooking fuels. Atmos Environ. 2015;113:159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Rao KU, Kishore VVN. A review of technology diffusion models with special reference to renewable energy technologies. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2010;14:1070–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Rehfuess EA, Puzzolo E, Stanistreet D, Pope D, Bruce NG. Enablers and barriers to large-scale uptake of improved solid fuel stoves: a systematic review. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:120–30. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1306639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen G, Lin W, Chen Y, Yue D, Liu Z, Yang C. Factors influencing the adoption and sustainable use of clean fuels and cookstoves in China - a Chinese literature review. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2015;51:741–750. [Google Scholar]

- Sinton JE, Smith KR, Zhang J, Ma Y. An assessment of programs to promote improved household stoves in China. Energy Sustain Dev. 2004;8:33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, Shuhua G, Kun H, Daxiong Q. One Hundred Million Improved Cookstoves in China: How Was It Done? World Dev. 1993;21:947–61. [Google Scholar]

- The government of the people's republic of china. The Ninth Five Year Plan on National Economy and Social Development and Long-Range Objectives to the Year 2010. Beijing: The Government of the People's Republic of China; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- The people's Government of hebei province. New urabnisation and rural-urban coordinated pilot region development plan of Hebei Province (2016-2020) The People's Government of Hebei Province; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Troncoso K, Castillo A, Masera O, Merino L. Social perceptions about a technological innovation for fuelwood cooking: Case study in rural Mexico. Energy Policy. 2007;35:2799–2810. [Google Scholar]

- World bank. East Asia and Pacific Clean Stove initiative Series. Washington, DC, USA: World Bank; 2013. China: accelerating household access to clean cooking and heating. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Burning Opportunity: Clean Household Energy for Health, Sustainable development, and Wellbeing of Women and Children Executive Summary. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yang GH, Stroup DF, Thacker SB. National public health surveillance in China: implications for public health in China and the United States. Biomed Environ Sci. 1997;10:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JJ, Smith KR. Household air pollution from coal and biomass fuels in China: measurements, health impacts, and interventions. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:848–55. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.