Abstract

Objective

To promote patient-centered oncology care through an in-depth analysis of the patient experience of body image disturbance (BID) following surgery for head and neck cancer (HNC).

Study Design

Qualitative methods approach using semistructured key informant interviews.

Setting

Academic medical center.

Subjects and Methods

Participants with surgically treated HNC underwent semistructured key informant interviews and completed a sociodemographic survey. Recorded interviews were transcribed, coded, and analyzed using template analysis to inform creation of a conceptual model.

Results

Twenty-two participants with surgically treated HNC were included, of whom 16 had advanced stage disease and 15 underwent free tissue transfer. Five key themes emerged characterizing the participants’ lived experiences with BID following HNC treatment: personal dissatisfaction with appearance, other-oriented appearance concerns, appearance concealment, distress with functional impairments, and social avoidance. The participant’s perceived BID severity was modified by preoperative patient expectations, social support, and positive rational acceptance. These 5 key themes and 3 experiential modifiers form the basis of a novel, patient-centered conceptual model for understanding BID in HNC survivors.

Conclusion

A patient-centered approach to HNC care reveals that dissatisfaction with appearance, other-oriented appearance concerns, appearance concealment, distress with functional impairments, and social avoidance are key conceptual domains characterizing HNC-related BID. Recognition of these psychosocial dimensions of BID in HNC patients can inform development of HNC-specific BID patient-reported outcome measures to facilitate quantitative assessment of BID as well as the development of novel preventative and therapeutic strategies for those at risk for, or suffering from, BID.

Keywords: qualitative research, head and neck cancer, body image disturbance, survivorship, patient-reported outcomes

Head and neck cancer (HNC) arises in cosmetically and functionally critical areas including the face, neck, tongue, pharynx, and larynx. As a result, changes in highly visible and socially significant parts of the body due to HNC and its treatment are common.1–3 Disfigurement and impaired smiling, swallowing, and speaking can result in substantial psychosocial morbidity including depression,4,5 anxiety,5 suicide,6 and concerns about body image.7–9 Body image disturbance (BID) is a multidimensional phenomenon characterized by a self-perceived change in appearance, function, or both.10 BID is prevalent in HNC survivors11; associated with social isolation, stigmatization, depression, and decreased quality of life (QOL)1,3,8–10,12–14; and a key component of survivorship care.15

The disfiguring nature of HNC and its treatment has been recognized for quite some time,12,16,17 but only recently have clinicians and researchers adopted a more patient-centered approach to understanding body image.3,10,18,19 Harnessing patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs) to deliver patient-centered oncology care results in improved symptom management, enhanced QOL, and increased survival.20,21 A landmark study by Krouse et al evaluating adaptation following HNC treatment analyzed longitudinal changes in BID, helping shift the research emphasis away from characterizing disfigurement in a surgeon-centric, objective manner to one that involves a more patient-centered understanding of BID.11,22 Unfortunately, this transition toward a patient-centered understanding of BID for HNC survivors has been hampered by the lack of in-depth qualitative research.10 As a result, there are large gaps in our ability to measure HNC-related BID and deliver patient-centered preventative and therapeutic interventions for those at-risk for or suffering from BID.15 We therefore undertook this qualitative study to provide an in-depth, patient-centered description of body image concerns in HNC survivors to improve patient-centered approaches to conceptualize, measure, prevent, and treat BID in HNC patients.

Methods

Study Design

We employed qualitative methods consisting of semistructured key informant interviews with HNC survivors to examine experiences with BID. Participants also completed a sociodemographic survey. The Institutional Review Board at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) approved this study. Participants were enrolled after providing written informed consent. The design, conduct, and reporting were carried out according to COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ) Publication Guidelines.23

Study Sample

Inclusion criteria were (1) HNC diagnosis, (2) American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage I to IV disease without distant metastases, (3) ≥18 years of age, (4) curative intent surgery at MUSC 1 to 36 months prior to enrollment, (4) English speaking, and (5) expressed concerns about appearance or function following HNC treatment. Participants were recruited from a single multidisciplinary HNC clinic from July 16 to August 30, 2018. The project coordinator reviewed the electronic medical record to identify potential participants. Those meeting demographic and oncologic inclusion criteria were screened in a dedicated research space within the HNC clinic by the coordinator with an open-ended question about body image concerns. This was followed by face-to-face recruitment by a study investigator. Purposive sampling was performed to ensure representation by age, sex, race, oncologic subsite, AJCC classification, ablative surgery, reconstruction, adjuvant therapy, and time since treatment to enhance the scientific rigor of our approach and ensure comprehensive identification of body image concerns. Forty-seven potential participants were screened: 12 denied appearance or functional concerns and 13 declined due to lack of interest or time, producing a final sample of 22 participants. The sample size was not prespecified but determined by thematic saturation (ie, performance of additional interviews failed to reveal novel, previously unidentified themes).24 All recruited participants were interviewed. Participants received $20 by check.

Key Informant Interviews

Two male team members trained in qualitative methods (M.A.E. and E.M.G.) conducted the key informant interviews in a one-on-one in-person session in a research room. An interview guide based on current literature on HNC-related BID3,18,19,25–29 provided a preliminary framework. This interview guide was pilot tested and subsequently revised to better reflect patient language about image changes due to HNC and its treatment, types, and descriptions of functional impairments as well as the spectrum of social impact. Each participant was asked the same open-ended questions regarding appearance concerns, functional impairments, social interactions, and coping mechanisms followed by prompts as needed. Each interview was digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim, and entered into NVivo 12 (version 12, 2018; QSR International Pty Ltd, Melbourne, Australia) for coding and analysis.30 Data analysis was supplemented by field notes. Following completion of the interviews, a sociodemographic questionnaire was administered. Interview transcripts were returned to 18 of 22 participants for comment on accuracy; no inaccuracies were noted. We were unable to get in touch with 4 of 22 participants to review interview transcript comments.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Coding and qualitative data analysis were performed by M.A.E. and E.M.G. using template analysis (TA).30,31 TA is a form of thematic analysis that emphasizes hierarchical coding. TA employs a combined inductive-deductive approach that starts with a preliminary coding template, determined based on a priori themes (including personal satisfaction with appearance, other-oriented perception of appearance, functional impairments, appearance concealment and checking, and social avoidance and isolation). The preliminary coding template is combined with a subset of the data, revised, refined, and adapted in an iterative fashion as emerging themes are grouped into meaningful clusters until data are exhaustively coded. None of our a priori themes were discarded. Over the 5 versions of the template, all 5 themes were slightly renamed, new subthemes were identified, and experiential modifiers that were not a priori themes emerged. Differences in coding were adjudicated by 3 authors (M.A.E., K.R.S., and E.M.G.) until consensus was attained. Key themes and experiential modifiers emerging from TA were used to generate a conceptual model of HNC-related BID.30

Ontological Framework and Reflexivity

A critical realist approach to ontology guided our research paradigm and approach to TA.32 To minimize bias and the inherent influence of the researcher on the research, we used a team approach to reflexivity.33 Individual reflexive tools (reflexive diaries, fieldnotes, and memos detailing analytic and methodological decisions) were shared at team meetings over the study period.

Results

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical details of the 22 participants. The median duration of key informant interviews was 18 minutes (range, 6–31 minutes).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Patients (N = 22) |

|---|---|

| Age, y, median (range) | 62 (23–84) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 9 (41) |

| Male | 13 (59) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 16 (73) |

| Black | 6 (27) |

| AJCC pathologic stage, n (%) | |

| I | 2 (9) |

| II | 4 (18) |

| III | 6 (27) |

| IV | 10 (46) |

| Tumor location and histology, n (%) | |

| Oral cavity SCC | 8 (36) |

| Facial skin cutaneous | 4 (18) |

| Major salivary gland | 3 (14) |

| Maxillary sinus SCC | 3 (14) |

| Oropharynx SCC | 2 (9) |

| Larynx SCC | 1 (5) |

| CN 11 MPNST | 1 (5) |

| Ablation surgery, n (%) | |

| Glossectomy | 4 (18) |

| Mandibulectomy | 4 (18) |

| Skin or soft-tissue resection | 4 (18) |

| Maxillectomy | 3 (14) |

| Pharyngectomy | 2 (9) |

| Othera | 5 (23) |

| Reconstructive surgery, n (%) | |

| Free tissue transfer | 15 (68) |

| Local flap | 3 (14) |

| Skin graft | 3 (14) |

| Primary closure | 1 (5) |

| Adjuvant therapy, n (%) | |

| Yes | 16 (73) |

| No | 6 (27) |

| Follow-up, months from surgery, median (range) | 5 (1–21) |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; CN, cranial nerve; MPNST, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

ã Total laryngectomy (n = 1), resection of CN 11 malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (n = 1), radical parotidectomy (n = 1), submandibular gland and oral cavity composite resection (n = 1), submandibular gland and skin composite resection (n = 1).

Experiential Themes of BID

An in-depth analysis of the lived experience of HNC patients demonstrated that their body image concerns extended significantly beyond disfigurement. As shown in Table 2, 5 dominant themes of BID in surgically managed HNC patients emerged: (1) personal dissatisfaction with appearance, (2) other-oriented appearance concerns, (3) appearance concealment, (4) distress with functional impairments, and (5) social avoidance.

Table 2.

Experiential Themes of Body Image Disturbance: Representative Quotes from Semistructured Interviews.

| Theme | Subtheme | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Personal dissatisfaction with appearance | Head and neck–specific concerns | “Aside from the scar [on my neck], the only thing that bothers me is the symmetry. The alignment of my jaw is off.” (Participant 8) “The only thing that has changed for me are the scars and the swelling [on my neck], I have to deal with it. It’s hard for me.” (Participant 16) “Symmetry is a big, big, big concern and I worry if it’s ever going to match my right side of my face. With me having a surgery, I know that probably it won’t be completely like my right face but that is one of my worries. Will it ever match my right face? Will my left eye really ever match my right eye? Will my left cheek ever really match my right cheek? So yes, symmetry is one of my big concerns.” (Participant 19) |

| Global attractiveness | “I’m less attractive now. Because I don’t look like the way I used to look. My face has change dramatically. That’s not something easy which you could ease on to.” (Participant 15) “There are times where I feel less attractive as a woman. I do. Just because of how my face presents and when you go out that’s the first thing that anybody sees. They see your face.” (Participant 19) |

|

| Other-oriented appearance concerns | NA | “People look at me weird sometimes but I don’t know some of them so. . . . Just like when I go into a store or something like that people like stare at me. They give you that pity look.” (Participant 4) “I just noticed that my grandchildren, they are so young. They just like stare or, out in public. This isn’t as bad now but when I first was able to go out in public, I felt like everybody was staring at me.” (Participant 5) “People kept staring at me. It made me feel embarrassed.” (Participant 11) “Children run and even parents, they act like you are a freak or something. And you are called names and stuff just when you go out in public and I think the mental part of it is more than anything else, more so than the scars. You just have to deal with people’s judgments on everything and the way they look at you.” (Participant 15) |

| Appearance concealment | Camouflaging | “I have 3 or 4 jackets with hoods on the sweatshirt jackets with hoods and I’ll wear them even in the summertime if I have to go out to a public place. . . . I go out in public and I had my hoodie on to cover up so they don’t see it.” (Participant 1) “I adapt to my appearance, like with wearing these bandanas. When I cover it [my neck] up, I just feel a little more confident. I just feel more relaxed or I don’t feel like somebody’s staring at me.” (Participant 7) “I try covering it [my scar] because it does bother me and I don’t want anything like this. . . . I would just feel terrible, then like, I try covering it [my scar] all the time.” (Participant 13) “I usually wear scarves to hide it [neck scar] so I don’t have to show most of the scarring. But you can’t wear a scarf high enough to cover the face.” (Participant 15) |

| Suppression | “Avoid the mirrors . . . sometimes I just couldn’t look in that mirror and see myself and just put my head down and walk away out of there.” (Participant 1) “There is sometimes when I would rather not check and look, like it took me a while to look at my tongue. I didn’t want to see it.” (Participant 5) |

|

| Distress with functional impairment | NA | “But I couldn’t eat anything. That was really hard. The first time, the first part of the surgery when I couldn’t talk. It appeared that I was just there. I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t talk, I couldn’t drink anything, my face was messed up. I was feeling like I was just a skip from the grave.” (Participant 2) “Talking has changed because I like to talk and I used to talk but now I can’t very well. I don’t eat. I eat by the G-tube; nothing by mouth. I get spit and mucous dripping out of my mouth.” (Participant 12) |

| Social avoidance | Avoidance due to disfigurement | “I don’t really go out in public, you know what I am saying, get out with people. Even when my daughter has something at school, I am really reluctant to even go, even though I know everybody there and people are really nice to me, you know what I am saying, the school knows me but I just don’t want to embarrass her. . . . I’m ashamed, and going out the way I look. I mean, I don’t want to embarrass her or anybody or have anybody really just say anything.” (Participant 1) “I relate more with people now over the phone than I do in person. My depression really kicks in and I just don’t really want to go out. I just really talk to somebody on the phone than have a face to face with anybody.” (Participant 15) “It [scars on my face] really shuts you down mentally because it makes you not want to go out in public at all and be seen around anybody. I mean, I stay home twice as much now than I did before.” (Participant 15) |

| Avoidance due to functional | “I avoided going out. . . . I didn’t want to talk. I didn’t want to go out and see anyone. I wasn’t going to family functions. I didn’t want anybody coming over. I just avoided everything, really.” (Participant 5) “I just don’t like going out with a new group of people that I don’t know. I just feel like they’ll be looking at you and say you don’t talk right or something like that. I say something they don’t understand but it just kind of embarrassing to me they don’t understand the way I’m talking.” (Participant 6) “I feel like it [social interactions] has changed if I’m trying to meet someone new. I’m more inclined not to talk as much because I’m self-conscious and I don’t enjoy talking because of how I sound.” (Participant 17) |

Theme 1: Personal Dissatisfaction with Appearance

Personal dissatisfaction with appearance focused on how HNC and its treatment resulted in (1) dissatisfaction with changes to the face and neck and (2) global feelings of unattractiveness. Head and neck–related dissatisfaction generally focused on unhappiness about scars, asymmetry, and swelling. As one participant explained, “I don’t want them [scars]. I knew what they had to do to me. They are taking my leg bone out and my jaw bone out” (participant 1). Others similarly described dissatisfaction with posttreatment changes to the face and neck region: “My face is more puffy. My neck is more swollen. Because the flap is there, it almost looks like I’m a stroke patient” (participant 19). Many participants explained that they felt globally less attractive because of HNC or its treatment: “I’m less attractive now. Because I don’t look like I used to look. My face has changed dramatically” (participant 15) and “I am less attractive because right now there is a big lump on my face. . . . I feel like the Phantom of the Opera” (participant 14).

Theme 2: Other-Oriented Appearance Concerns

Participants also described concern regarding how others perceived their appearance, focusing on nonverbal (eg, staring, facial expressions) and verbal reactions (eg, hurtful words). One participant summed up her experience thusly: “I know a lot of people look at me and they have something to say about the way I look and that bothers me . . . it makes me pissed off” (participant 6).

Theme 3: Appearance Concealment

Participants with body image concerns described attempts to camouflage aspects of their appearance. Camouflaging (or covering, concealing, or hiding) manifested through the use of acceptable fashion such as “jackets with hoods on the sweatshirts” (participant 1), “long sleeves or a coat or . . . turtleneck” (participant 5), or “sunglasses” (participant 10) to cover the face or neck. For other participants, concealment was more of a cognitive activity of image suppression: “When I first came home from the hospital, I avoided it [my appearance in the mirror] completely. I avoided looking at myself in the mirror because of the drooling and my chin was hanging down to here” (participant 2). Pictures were another source of image representation that patients avoided: “I don’t like to check because it just makes me feel more self-conscious with the way I look from the way I used to look. . . . I do not like my pictures taken” (participant 15).

Theme 4: Distress with Functional Impairment

Distress with head and neck–related functional impairments was common and related to challenges with speaking, eating, swallowing, oral competence, xerostomia, and facial paralysis. Speaking and eating difficulties were commonly described: “I don’t like not having teeth in my mouth where I can actually eat or chew. . . . I can’t just eat anything and a lot of times I don’t eat anything other than food from my feeding tube” (participant 1). These impairments resulted in a variety of emotional responses from participants, most often frustration: “They cut off part of my tongue that’s why I don’t talk clearly now. Sometimes people can’t understand me. It’s kind of frustrating” (participant 6). Another participant expressed their speech concerns via writing, “My voice and stuff because I can’t speak. So communication definitely. It’s been difficult for me to communicate with my family” (participant 20).

Theme 5: Social Avoidance

Social avoidance due to body image concerns was an important theme and categorized as (1) avoidance due to disfigurement and (2) avoidance due to functional impairment. Disfigurement-related avoidance was most prominent in places such as the church or grocery store, where social interactions could occur with casual acquaintances. According to one participant,

I was embarrassed to go out. . . . But to go out to church right now, I would have to answer too many questions, “What happened to you?” Like if you have breast cancer, they can’t see the scar. But the face, is the first thing they see and it’s difficult to hide. So, right now, I better not be in big a crowd. I hesitate to even go to Walmart. (Participant 2)

Function-related avoidance (eg, speaking, swallowing) was described as follows:

I just didn’t feel like going out. I just felt like everybody would be looking at my face. I was also self-conscious about my speech. I can hide my back or my arm but you can’t necessarily hide your mouth. If you talk, you feel like people notice your tongue or even my lip. So, I just wanted to avoid it all. (Participant 5)

Experiential Modifiers of Perceived BID Severity

Although nearly all participants struggled with the key themes above, participants differed in their perception of the qualitative severity of their BID. Key factors influencing the perceived severity of BID included (1) preoperative expectations, (2) social support, and (3) positive rational acceptance (Table 3).

Table 3.

Experiential Modifiers of Perceived Body Image Disturbance Severity: Representative Quotes from Semistructured Interviews

| Theme | Examples |

|---|---|

| Preoperative expectations | “I didn’t realize I was going to look quite as bad as I do before I had the surgery. . . . I think in my head I thought I’d look different but I thought I was going to look really close to normal. . . . I didn’t realize the extent that that was going to be and I think that the doctor should say, look, you are never going to look like you again. There is going to be a lot of deformity.” (Participant 1) “Well, when I looked in the mirror at the wound for the first time it kind of took my breath away because I had never envisioned myself with something like that on the top of my head.” (Participant 3) “We had no clue what we were getting into. . . . No idea whatsoever. We didn’t know what the flap was going to look like. We just didn’t know anything. And I think that it would really, really help people if they knew more. . . . I guess for some reason I thought I would have surgery and afterwards could be somewhat normal. We had no idea. I didn’t realize it was going to be like this.” (Participant 4) |

| Social support | “I have a big support system, especially our church family so that helps a lot too.” (Participant 9) “I do have a group of very good friends. And we’re very close. And they look at me for who I am, not what I like. . . . You need to depend on family and friends. And have trust in the doctors.” (Participant 12) “At the beginning, it [surgical changes to her ear] bothered me a lot but my husband was good about encouraging me. I don’t think about it as much anymore. He had a lot to do with it. He really did because I used to feel just terrible.” (Participant 13) “I’m amazed by how much I’ve healed from the initial day of surgery. They [my friends and family] have been a huge support. They always tell me I’m still pretty and my face is going down and the swelling is going down and how remarkable my healing is doing so I’ve had a great support with family and friends.” (Participant 19) |

| Positive rational acceptance | “It [your appearance] is going to change drastically. It is going to be a matter of mind over matter when it does happen; you just got to get over it. You just got to stay strong.” (Participant 1) “What can you do? They [the surgeons] do what they have to do. It’s what had to happened. At least the eye is still good. I have to look at the good things and not just the bad. That’s just me. What can you do about it? I cannot sit around and cry over it all the time.” (Participant 10) “I have pretty much adjusted and look at the bigger picture of it [appearance changes], and I’m comfortable with it. . . . And my advice to future patients would be that you will see changes and there will be some types of change, but you got to be positive about it, and not let it affect you. I mean, because you can’t control it. Certain things are beyond our control.” (Participant 22) |

Theme 1: Preoperative Expectations

A disjunction between preoperative expectations and post-operative reality exacerbated BID severity. As one participant explained,

If I would have known ahead of time, I believe I wouldn’t have taken it [appearance changes] so bad. But I was stunned when I came out of the operating room and saw what had happened. I wish somebody would have given me a little heads up or something before. . . . Because that’s what bothered me the worst when I woke up and it was like a whole different me and that shook me up for a long time. What I’m saying is the doctors should give them [future patients] a heads up about what you’re going to look like or something. That will help them [future patients] in a long way. (Participant 6)

Theme 2: Social Support

Social support (particularly family and friends) was instrumental in moderating the severity of BID by positively shaping body image or mitigating negative downstream consequences.

But because of my family and close friends, they gave me strength when I had weak moments and everybody going through this needs support from their family. Because you can’t do it by yourself. . . . They said I was healing but I felt that I looked the same and that’s when my family would reemphasize what the doctors told me. So that kept me going. If they hadn’t been there to reassure me, I think I would have some kind of depression. (Participant 2)

Theme 3: Positive Rational Acceptance

Participants used positive rational acceptance (strategies to emphasize acceptance of one’s body image and positive thinking about appearance)34 to minimize the severity of BID. One participant described coming to terms with his new image this way:

I will not let this [appearance changes] affect my dealings with other people. It is a part of what I am. There is going to be a significant scar on my left scalp after the healing process and I will carry that with me the rest of my life. And it is what it is. Life goes on. (Participant 3)

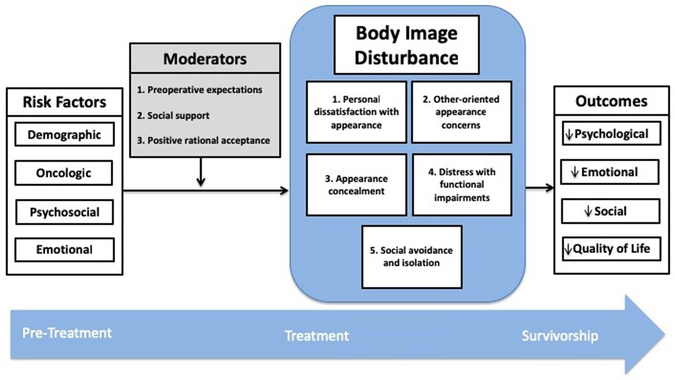

Conceptual Model

Our conceptual model of BID for patients with HNC is shown in Figure 1. This model is informed by a model from Rhoten et al10 and synthesizes our new qualitative findings about key themes and experiential modifiers of HNC-related BID with previously published risk factors for BID35–39 and its negative outcomes.2,28,40,41

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of body image disturbance in head and neck cancer patients demonstrating risk factors, key domains, experiential modifiers, and negative outcomes.

Discussion

Experiential Themes of BID

Our qualitative work suggests that HNC-specific BID is richer and more complex than prior quantitative work using PROMs of BID that were neither designed for, nor validated in, HNC patients. These studies have suggested either 210,25 or 3 domains42: (1) appearance distress, (2) functional difficulties,10,25 and (3) psychological distress associated with the change in appearance, function, or both.42 Our patient-centered qualitative approach suggests that other-oriented appearance concerns and appearance concealment are key constructs of HNC-specific BID that have not been previously characterized. Others have described observers’ response to facial disfigurement from HNC43 but not concerns HNC survivors have about how their image is perceived by others. Although appearance concealment for HNC patients with BID has been described,18,25 it has not been recognized as a salient construct within the multidimensional understanding of BID.

Experiential Modifiers of Perceived BID Severity

We found that the participant’s perception of the severity of BID was modified by preoperative patient expectations, social support, and positive rational acceptance. Positive rational acceptance has been identified as a modifier of BID in the nononcologic setting.34 Herein, we highlight its potential importance for HNC patients. Prior research has suggested that being single is a risk factor for BID in HNC patients.44 The interplay between being single and support should be explored in future work, although there is an increasing body of work recognizing the importance of caregiver dyads for HNC patients.45,46

Practical Implications and Future Directions

Our research has a number of practical implications. First, there is a sizable and clear subset of HNC patients who are dissatisfied with the discussion of body image issues.15,47 Raising awareness about the nature and extent of BID in HNC patients and providing a vocabulary and structure for clinicians to engage HNC patients with body image concerns can facilitate communication. Second, the assessment of BID in HNC patients has been limited by the lack of an HNC-specific instrument.3,10,25 Our novel empirical findings about the structure and content of body image concerns in HNC patients provides the framework for the development of a psychometrically sound, multidomain PROM to measure BID in the clinical and research realms. Third, targeted, effective interventions for HNC survivors suffering from BID remain unknown.48 Our data provide the substrate for the development of rational, patient-centered intervention.49 Based on the findings in this qualitative work and a needs assessment within our ongoing prospective cohort study, we developed and pilot tested a novel 5-session manualized cognitive behavioral therapy intervention to treat BID in HNC survivors (NCT03518671). Our intervention commences 1 month after completion of therapy and targets the cognitive, behavioral, and attitudinal components of BID. Fourth, our study highlights 3 factors (Figure 1) that represent potential therapeutic targets to influence the development of BID or its downstream negative effects on psychosocial well-being or QOL. Future work should use validated PROMs of HNC-related BID to evaluate quantitatively the strength of the association between these modifying variables and BID severity, as well as to identify strategies to manipulate these potential therapeutic targets.

Limitations

The study’s major strength is the use of qualitative techniques to gain an in-depth understanding of patient experiences not available through quantitative research.50 Our qualitative analysis was performed using standard techniques to ensure scientific rigor and minimize subjectivity and bias.23 The study nevertheless possesses important limitations. It is a single-institution study set at a high-volume, academic center in the Southeastern United States in a primarily rural state; therefore, the applicability of our results to other regions of the United States or to institutions with different patient demographics, case complexity, provider practices, or preoperative counseling is unknown. Although we engaged in purposive sampling to recruit a representative sample based on variables thought to affect the risk of BID and continued recruiting until thematic saturation, it remains possible that had we interviewed more or different participants, additional data about key domains or modifiers of BID may have emerged, and we could have developed a different conceptual model. Because recruitment was at an academic practice, it is likely that patients had more complex ablative and reconstructive surgical procedures than if we had recruited across a diversity of practice types. It is also likely that patients with less severe body image concerns were less likely to participate in the study, which may bias our findings toward more severe descriptions of BID. However, since the goal of the study was to describe the lived experiences of HNC patients with BID, our sampling techniques are commensurate with the research objective and in line with prior qualitative work set at academic HNC centers.18,51,52

Conclusion

A patient-centered approach to HNC care reveals that dissatisfaction with appearance, other-oriented appearance concerns, appearance concealment, distress with functional impairments, and social avoidance are key conceptual domains characterizing HNC-related BID. Recognition of these psychosocial dimensions of BID in HNC patients can inform development of an HNC-specific BID PROM to facilitate quantitative assessment of BID as well as the development of novel preventative and therapeutic strategies for those at risk for or suffering from BID.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: AAO-HNS/F CORE 577381, American Cancer Society IRG-16-185-17, Biostatistics Shared Resources of the Hollings Cancer Center, P30 CA138313.

Sponsorships: None.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Competing interests: Terry A. Day, Olympus (advisory board).

References

- 1.Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, van Bleek W, Leemans CR, de Bree R. Employment and return to work in head and neck cancer survivors. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fingeret MC, Yuan Y, Urbauer D, Weston J, Nipomnick S, Weber R. The nature and extent of body image concerns among surgically treated patients with head and neck cancer. Psychooncology. 2012;21:836–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fingeret MC, Teo I, Goettsch K. Body image: a critical psychosocial issue for patients with head and neck cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2015;17:422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rieke Katherine K Depression and survival in head and neck cancer patients. Oral Oncol. 2017;65:76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu Yi-Shan YS. Anxiety and depression in patients with head and neck cancer: 6-month follow-up study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1029–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osazuwa-Peters Nosayaba N Suicide risk among cancer survivors: head and neck versus other cancers. Cancer. 2018;124: 4072–4079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeBoer MF, McCormick LK, Pruyn JF, Ryckman RM, van den Borne BW. Physical and psychosocial correlates of head and neck cancer: a review of the literature. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120:427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jansen F, Snyder CF, Leemans CR, Verdonck–de Leeuw IM. Identifying cutoff scores for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the head and neck cancer–specific module EORTC QLQ-H&N35 representing unmet supportive care needs in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2016;38(suppl 1):E1493–E1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy BA, Ridner S, Wells N, Dietrich M. Quality of life research in head and neck cancer: a review of the current state of the science. Crit Rev Oncol. 2007;62:251–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rhoten BA, Murphy B, Ridner SH. Body image in patients with head and neck cancer: a review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2013;49:753–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fingeret MC, Vidrine DJ, Reece GP, Gillenwater AM, Gritz ER. Multidimensional analysis of body image concerns among newly diagnosed patients with oral cavity cancer. Head Neck. 2010;32:301–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz MR, Irish JC, Devins GM, Rodin GM, Gullane PJ. Psychosocial adjustment in head and neck cancer: the impact of disfigurement, gender and social support. Head Neck. 2003; 25:103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu T, Cooke M, McCarthy A. A qualitative study of the experience of oral cancer among taiwanese men. Int J Nurs Pract. 2009;15:326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Millsopp L, Brandom L, Humphris G, Lowe D, Stat C, Rogers S. Facial appearance after operations for oral and oropharyngeal cancer: a comparison of casenotes and patient-completed questionnaire. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;44:358–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen EEW, LaMonte SJ, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society head and neck cancer survivorship care guideline. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:203–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dropkin MJ. Compliant behavior and changed body image. Am J Nurs. 1979;79:1249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vickery LE, Latchford G, Hewison J, Bellew M, Feber T. The impact of head and neck cancer and facial disfigurement on the quality of life of patients and their partners. Head Neck. 2003;25:289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albornoz CR, Pusic AL, Reavey P, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life outcomes in head and neck reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg. 2013;40:341–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellis MA, Sterba KR, Brennan EA, Maurer S, Hill EG, Day TA, Graboyes EM. A systematic review of patient reported outcome measures assessing body image disturbance in patients with head and neck cancer [published online ahead of print February 12, 2019]. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. doi: 10.1177/0194599819829018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;34:557–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rotenstein LS, Huckman RS, Wagle NW. Making patients and doctors happier—the potential of patient-reported outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1309–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krouse JH, Krouse HJ, Fabian RL. Adaptation to surgery for head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:789–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19: 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teo I, Fronczyk KM, Guindani M, et al. Salient body image concerns of patients with cancer undergoing head and neck reconstruction. Head Neck. 2016;38:1035–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beal BT, White EK, Behera AK, et al. A novel, disease-specific self-report instrument to measure body image concerns in patients with head and neck skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teo I, Fronczyk KM, Guindani M, et al. Salient body image concerns of patients with cancer undergoing head and neck reconstruction. Head Neck. 2016;38:1035–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen SC, Yu PJ, Hong MY, et al. Communication dysfunction, body image, and symptom severity in postoperative head and neck cancer patients: factors associated with the amount of speaking after treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23: 2375–2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Costa EF, Nogueira TE, de SL, Mendonca EF, Leles CR. A qualitative study of the dimensions of patients’ perceptions of facial disfigurement after head and neck cancer surgery. Spec Care Dentist. 2014;34:114–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brooks J, McCluskey S, Turley E, King N. The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qual Res Psychol. 2015;12:202–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crabtree BF, Miller WF. A template approach to text analysis: developing and using codebooks In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Eds. Research Methods for Primary Care. Vol 3. Doing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1992:93–109. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harper D Choosing a qualitative research method In: Harper D, Thompson AR, Eds. Qualitative Research Methods in Mental Health and Psychotherapy. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011:83–98. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barry CA, Britten N, Barber N, Bradley C, Stevenson F. Using reflexivity to optimize teamwork in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 1999;9:26–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cash TF, Santos MT, Williams EF. Coping with body-image threats and challenges: validation of the body image coping strategies inventory. J Psychosom Res. 2005;58:190–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beal BT, White EK, Behera AK, et al. Patients’ body image improves after Mohs micrographic surgery for nonmelanoma head and neck skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1380–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen SC, Huang CY, Huang BS, et al. Factors associated with healthcare professional’s rating of disfigurement and self-perceived body image in female patients with head and neck cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27(2):e12710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clarke S, Newell R, Thompson A, Harcourt D, Lindenmeyer A. Appearance concerns and psychosocial adjustment following head and neck cancer: a cross-sectional study and nine-month follow-up. Psychol Health Med. 2014;19:505–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hung T, Lin C, Chi Y, et al. Body image in head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy: the impact of surgical procedures. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu H Changes of satisfaction with appearance and working status for head and neck tumour patients. J Clin Nurs. 2008; 17:1930–1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rhoten BA, Deng J, Dietrich MS, Murphy B, Ridner SH. Body image and depressive symptoms in patients with head and neck cancer: an important relationship. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:3053–3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fingeret MC, Hutcheson KA, Jensen K, Yuan Y, Urbauer D, Lewin JS. Associations among speech, eating, and body image concerns for surgical patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2013;35:354–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rhoten BA. Body image disturbance in adults treated for cancer—a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72:1001–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho J, Fingeret MC, Huang SC, Liu J, Reece GP, Markey MK. Observers’ response to facial disfigurement from head and neck cancer. Psychooncology. 2018;27:2119–2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deng J, Murphy BA, Dietrich MS, et al. Impact of secondary lymphedema after head and neck cancer treatment on symptoms, functional status, and quality of life. Head Neck. 2013; 35:1026–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sterba KR, Zapka J, Armeson KE, et al. Physical and emotional well-being and support in newly diagnosed head and neck cancer patient-caregiver dyads. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2017; 35:646–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sterba KR, Zapka J, Cranos C, Laursen A, Day TA. Quality of life in head and neck cancer patient-caregiver dyads: a systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39:238–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fingeret MC, Nipomnick S, Guindani M, Baumann D, Hanasono M, Crosby M. Body image screening for cancer patients undergoing reconstructive surgery. Psychooncology. 2014;23:898–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fingeret MC, Teo I, Epner DE. Managing body image difficulties of adult cancer patients: lessons from available research. Cancer 2014;120:633–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cash TF, Pruzinsky T. Body Image: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice. New York, NY: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davies L, Hendrickson CD, Hanson GS. Experience of US patients who self-identify as having an overdiagnosed thyroid cancer: a qualitative analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143:663–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Francis DO, Sherman AE, Hovis KL, et al. Life experience of patients with unilateral vocal fold paralysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144:433–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]