Abstract

The rise of antibiotic resistance (AMR) is one of the most important public health threats worldwide.Today, increasing attention is being paid to multidrug resistant staphylococci isolated from healthcare and non-healthcare environments as the treatment of these bacteria has become increasingly difficult. In this study, we compared staphylococci isolates recovered from high frequency touched surfaces from public areas in the community and hospitals in East and West London. 281 out of 600 (46.83%) staphylococci isolates recovered were multidrug resistant, of which 49 (8.17%) were mecA positive. There was significantly higher proportion of multidrug resistant staphylococci (P = 0.0002) in East London (56.7%) compared to West London (49.96%). The most common species identified as multidrug resistant were S. epidermidis, S. haemolyticus and S. hominis, whereas penicillin, fusidic acid and erythromycin were the most frequent antibiotics the isolates were resistant to. Whole genome sequenced of mecA positive isolates revealed that S. sciuri isolates carried the mecA1 gene, which has only 84.43% homology with mecA. In addition, other frequently identified resistance genes included blaZ, qacA/B and dfrC. We have also identified a diverse range of SCCmec types, many of which were untypable due to carrying a novel combination of ccr genes or multiple ccr complexes.

Subject terms: Bacterial genetics, Mobile elements

Introduction

Exemplified by S. aureus, staphylococci are known to cause nosocomial infections1,2. Due to resistance to multiple antibiotics, treatment of staphylococci infections has become increasingly difficult3,4. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and coagulase negative staphylococci (CoNS) can spread in healthcare and community-associated areas by skin to skin and skin to contaminated surfaces contacts5–7. Previous studies have shown those non-healthcare associated environments, including recreational beaches, public buses, residential (student) and built-up areas harbour multidrug resistant S. aureus5,8,9. However, studies reporting similar findings for CoNS are fragmentary5,7,8,10–13.

The development of antimicrobial resistance in staphylococci is due to selective pressure in the presence of antibiotics or due to stress factors in the environment14. Antibiotic resistance genes can be horizontally transferred to different strains and species via mobile elements such as plasmids, bacteriophages and transposons15. An example of this is the methicillin resistance gene mecA which is located on a mobile genetic element ‘staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec)’16. The mecA gene encodes the penicillin-binding protein 2a (PBP2a) that has a low binding affinity to all beta-lactam antibiotics17. The SCCmec is diverse in its genetic structure and to date 11 different SCCmec types have been characterised. SCCmec is determined by the combination of mec (A, B, C1, C2, D, E) and the chromosome cassette recombinase (ccr) (A1/B1, A2/B2, A3/B3, A4/B4, C1, A5/B3, A1/B6, A1/B3) complexes18–20. Different SCCmec types have evolved from two different genetic lineages, including hospital-associated and community-associated clones, however, currently, these different lineages can be found both in hospital and community environments21. However community-associated SCCmec types are generally smaller in size compared to their hospital associated counterparts22.

In this study, we report the differences in the proportion of multidrug resistance in CoNS staphylococci and the carriage of the mecA gene in isolates recovered from high-frequency hand touched surfaces of inanimate objects. Whole genome sequenced (WGS) mecA positive isolates revealed new molecular characteristics of these isolates.

Results

Sample collection

A total of 600 staphylococci isolates were recovered from general public settings and hospital public areas in East (n = 224) and West London (n = 376). 182 of 600 isolates were recovered from general public settings and 418 from public areas in hospitals. Of these 97 staphylococci were recovered from public settings from East London; 85 from public areas in West London; 127 were recovered from a hospital in East London and 291 from a hospital in West London.

Identification of multidrug resistant staphylococci from high-frequency hand touched areas

281 multidrug resistant staphylococci isolates belonging to 11 species were identified. These included S. epidermidis (n = 75), S. haemolyticus (n = 61), S. hominis (n = 56) S. saprophyticus (n = 24), S. warneri (n = 16), S. capitas (n = 15), S. cohnii (n = 15), S. sciuri (n = 9), S. aureus (n = 5), S. pasteuri (n = 4) and S. equorum (n = 1). At species level S. epidermidis, S. haemolyticus and S. capitis were prevalent in West London (n = 52; n = 40; n = 13), than in East London (n = 23; n = 21; n = 2), whereas S. aureus was prevalent in East London (n = 3), than in West London (n = 2). The number of isolates of S. hominis (n = 31), S. saprophyticus (n = 16), S. cohnii (n = 13) and S. pasteuri (n = 2) recovered from these two geographic areas were largely similar. In addition, S. warneri (n = 16) was recovered from West London, but not from East London, whereas S. sciuri (n = 9) and S. equorum (n = 1) were recovered from East London, but not from West London. In total, there were 10 species of staphylococci recovered from East London, compared to 9 species from West London.

The proportion of multidrug resistant staphylococci recovered from different public areas

281 out of 600 (46.83%) were identified as multidrug resistant staphylococci as they showed resistance to two or more antibiotics23. It was found that there was significantly higher proportion of multidrug resistant staphylococci (P = 0.0002) recovered from East London (56.7%) compared to those recovered from West London (49.96%) (Table 1). There was a slight significant difference (P = 0.0458) of the proportion of multidrug resistant staphylococcal isolates from public areas in the hospitals to general public settings (49.5% and 40.66% respectively) (Table 2).

Table 1.

The proportion of multidrug resistant staphylococci and mecA positive isolates compared with the number of isolates analysed in East and West London and the proportion of antibiotics they were resistant to compared with the number of multidrug resistant staphylococci from East and West London.

| East London | West London | stats to test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of samples screened (N = 224) | Total number of samples screened (N = 376) | ||||||

| N | % of total number of samples screened | N | % of total number of samples screened | % Difference | X2 | P value | |

| Multidrug resistant staphylococci | 127 | 56.70 | 154 | 40.96 | 15.74 | 13.944 | 0.0002 |

| mecA positive | 24 | 10.71 | 27 | 7.18 | 3.53 | 2.246 | 0.1340 |

| N | % MR staphylococci | N | % of MR staphylococci | % Difference | X2 | P value | |

| Oxacillin | 38 | 29.92 | 32 | 20.78 | 9.14 | 3.097 | 0.0784 |

| Gentamicin R | 13 | 10.24 | 13 | 8.44 | 1.79 | 0.268 | 0.6049 |

| Gentamicin I | 1 | 0.79 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.79 | 1.217 | 0.27 |

| Muprcion R | 4 | 3.15 | 8 | 5.19 | 2.05 | 0.706 | 0.4006 |

| Muprcion I | 25 | 19.69 | 4 | 2.60 | 17.09 | 21.879 | <0.0001 |

| Amoxicillin | 33 | 25.98 | 45 | 29.22 | 3.24 | 0.363 | 0.5468 |

| Erythromycin R | 47 | 37.01 | 96 | 62.34 | 25.33 | 17.805 | <0.0001 |

| Erythromycin I | 1 | 0.79 | 5 | 3.25 | 2.46 | 2.006 | 0.1567 |

| Tetracycline | 36 | 28.35 | 38 | 24.68 | 3.67 | 0.481 | 0.4878 |

| Cefoxitin | 29 | 22.83 | 34 | 22.08 | 0.76 | 0.022 | 0.8809 |

| Cefepime R | 7 | 5.51 | 10 | 6.49 | 0.98 | 0.117 | 0.7321 |

| Cefepime I | 2 | 1.57 | 1 | 0.65 | 0.93 | 0.557 | 0.4556 |

| Fusidic acid | 97 | 76.38 | 106 | 68.83 | 7.55 | 1.971 | 0.1603 |

| Penicillin | 102 | 80.31 | 124 | 80.52 | 0.20 | 0.002 | 0.9648 |

| Chloramphenicol R | 1 | 0.79 | 10 | 6.49 | 5.71 | 5.992 | 0.0144 |

| Chloramphenicol I | 1 | 0.79 | 2 | 1.30 | 0.51 | 0.17 | 0.6997 |

All chi-squared test was performed with 1 degree of freedom. R = resistance; I = intermediate resistance; MR = multidrug resistant.

Table 2.

The proportion of multidrug resistant staphylococci and mecA positive isolates compared with the number of isolates analysed in general public settings and in hospitals; the proportion of antibiotics they were resistant to compared with the number of multidrug resistant staphylococci from general public settings and from hospitals.

| General public settings | Public areas in hospitals | Chi-Square test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of samples Screened (n = 182) | Total number of samples Screened (n = 418) | ||||||

| n | % of total number of samples screened | n | % of total number of samples screened | % Difference | X2 | P value | |

| Multidrug resistant staphylococci | 74 | 40.66 | 207 | 49.52 | 8.86 | 3.991 | 0.0458 |

| mecA positive | 14 | 7.69 | 33 | 7.89 | 0.20 | 0.007 | 0.9332 |

| Antibiotic resistance | N | % MR Staphylococci | N | % MR staphylococci | % Difference | X2 | P value |

| Oxacillin | 24 | 32.43 | 46 | 22.22 | 10.21 | 3.097 | 0.0784 |

| Gentamicin R | 12 | 16.22 | 14 | 6.76 | 9.45 | 5.79 | 0.0161 |

| Gentamicin I | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.355 | 0.5512 |

| Mupirocin R | 2 | 2.70 | 10 | 4.83 | 2.13 | 0.603 | 0.603 |

| Mupirocin I | 6 | 8.11 | 23 | 11.11 | 3.00 | 0.528 | 0.4674 |

| Amoxicillin | 18 | 24.32 | 60 | 28.99 | 4.66 | 0.591 | 0.4421 |

| Erythromycin R | 33 | 44.59 | 110 | 53.14 | 8.55 | 1.589 | 0.2075 |

| Erythromycin I | 1 | 1.35 | 5 | 2.42 | 1.06 | 0.297 | 0.5856 |

| Tetracycline | 27 | 36.49 | 47 | 22.71 | 13.78 | 5.316 | 0.0211 |

| Cefoxitin | 9 | 12.16 | 54 | 26.09 | 13.92 | 6.06 | 0.0138 |

| Cefepime R | 7 | 9.46 | 10 | 4.83 | 4.63 | 2.049 | 0.1523 |

| Cefepime I | 2 | 2.70 | 1 | 0.48 | 2.22 | 2.542 | 0.1109 |

| Fusidic acid | 54 | 72.97 | 149 | 71.98 | 0.99 | 0.027 | 0.8706 |

| Penicillin | 56 | 75.68 | 170 | 82.13 | 6.45 | 1.436 | 0.2308 |

| Chloramphenicol R | 1 | 1.35 | 10 | 4.83 | 3.48 | 1.749 | 0.186 |

| Chloramphenicol I | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 1.45 | 1.45 | 1.081 | 0.2985 |

All chi-squared test was performed with 1 degree of freedom. R = resistance; I = intermediate resistance.

Antibiotic susceptibility of staphylococci isolates from high-frequency hand touched surfaces

All isolates were tested for their susceptibility using a panel of 11 antibiotics. Of the isolates that were shown to be multidrug resistant, 98 (34.88%) had resistance to two antibiotics; 87 (30.96%) to three antibiotics; 45 (16.01%) to four antibiotics; 15 (5.34%) to five antibiotics; 13 (4.63%) to six antibiotics; 12 (4.27%) to seven antibiotics; 9 (3.2%) to eight antibiotics and 2 (0.71%) to nine antibiotics (Fig. 1).

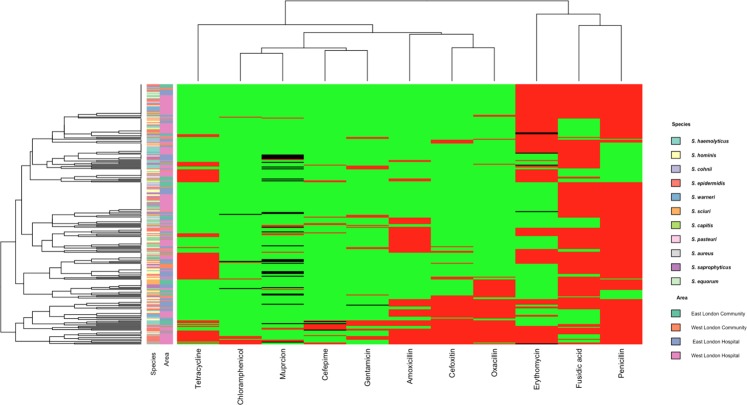

Figure 1.

Heatmap showing hierarchical clustering of isolates antibiotic resistance profiles in comparison with the species and area they were isolated from. Red tiles represent resistance, black tiles represent intermediate resistance and green represent sensitive patterns.

The most commonly found antibiotic that the staphylococci isolates were resistant to was penicillin 206 (80.42%); followed by fusidic acid 204 (72.4%) erythromycin 153 (54.45%), amoxicillin 78 (27.76%); tetracycline 74 (26.33%); oxacillin 70 (24.91%); cefoxitin 63 (22.42%); mupirocin 41 (14.59%); gentamycin 27 (9.61%); cefepime 20 (7.12%), and chloramphenicol 14 (4.98%) (Fig. 1).

Hierarchical clustering within a heat map, showed no correlation between species and area they were isolated from, to their antibiotic resistance profile (Fig. 1). The Chi-square analyses demonstrated that there was a significantly higher proportion of multidrug resistant staphylococci with erythromycin resistance (P =≤ 0.0001) and chloramphenicol resistance (P = 0.0143) from West London (62.34% and 6.49% respectively) compared to East London (37.01% and 0.79% respectively) (Table 1). The opposite was observed for mupirocin intermediate resistance with a significantly higher proportion of multidrug resistant staphylococci (P =≤ 0.0001) found in East London (19.67%) compared to West London (2.60%).

In the general public settings, there was a significantly higher proportion of isolates that had resistance to gentamycin (P = 0.00162) and tetracycline (P = 0.0211) (16.22% and 36.49% respectively) compared to public areas in hospitals (36.49% and 22.71% respectively) (Table 2). In contrast, a significantly higher proportion of multidrug resistant staphylococci (P = 0.0143) found in public areas in hospitals (26.09%) were resistant to cefoxitin compared to general public settings (12.16%).

Detection of mecA gene

The mecA gene was identified by PCR in 49 (8.17%) of total isolates recovered. There was no significant difference in the proportion of the mecA gene determined in isolates recovered from East London (10.71%) compared to those recovered from West London (7.18%) (P = 0.1340), the general public settings (7.69%) and public areas in hospitals (7.18%) (P = 0.9332). Of the isolates that were mecA positive, 44 (62.86%) were oxacillin resistant, whereas 43 (68.25%) isolates were cefoxitin resistant. Three isolates, including one each of S. hominis, S. epidermidis and S. haemolyticus that were mecA positive, were shown to be sensitive to oxacillin and 6 mecA positive isolates, all belonging to the S. sciuri species, were sensitive to cefoxitin.

Determination of MICs for oxacillin and cefoxitin

We have determined the MICs to oxacillin and cefoxitin for 49 isolates that carried the mecA gene (Table 3). Although all samples were mecA gene positive, only 44 CoNS isolates had MIC above the resistance breakpoints according to CSLI24. Five isolates, including S. hominis 372, 385, 387; S. epidermidis 465 and S. haemolyticus 361 that were mecA positive, were phenotypically sensitive to oxacillin. However, all five isolates were resistant to cefoxitin by zone diffusion assay. These isolates were recovered from public areas in hospitals. Neither CLSI nor BSAC recommend MIC standards for recording cefoxitin resistance24,25. Nevertheless, 42 out of 43 isolates in our study had MIC values of >1.5 μg/ml and were resistant to cefoxitin by a disc diffusion assay.

Table 3.

The antibiotic resistance profile of 49 mecA positive isolates recovered from public areas in hospitals and general public settings.

| Sample ID | species | Areas in London | Oxa | Gen | Mup | Amx | Erm | Tet | Fox | Fep | Fua | Pen | Chl | Oxa MIC (μg/ml) | Fox MIC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | S. haemolyticus | ELC | R | R | S | R | S | R | R | R | S | R | S | 3 | 4 |

| 27 | S. sciuri | ELC | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | R | S | 0.5 | 0.75 |

| 33 | S. sciuri | ELC | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | R | S | 0.5 | 1 |

| 59 | S. sciuri | ELC | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | S | S | 0.75 | 1 |

| 74 | S. sciuri | ELC | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | S | S | 0.5 | 1 |

| 75 | S. sciuri | ELC | R | R | I | S | S | S | S | S | R | S | S | 0.75 | 1 |

| 93 | S. haemolyticus | ELC | R | R | I | R | S | S | R | I | S | R | S | 2 | 4 |

| 99 | S. haemolyticus | ELC | R | R | S | R | S | R | R | S | S | R | S | 3 | 4 |

| 105 | S. haemolyticus | ELC | R | R | S | R | S | R | R | R | R | R | S | 2 | 4 |

| 109 | S. sciuri | ELC | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | R | S | 1 | 1 |

| 207 | S. hominis | WLC | R | S | S | S | R | S | R | S | R | R | S | 0.5 | 6 |

| 208 | S. hominis | WLC | R | S | S | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | S | 2 | 6 |

| 209 | S. hominis | WLC | R | S | S | R | R | S | R | S | R | R | S | 1.5 | 6 |

| 211 | S. cohnii | WLC | R | S | S | S | R | S | R | R | S | R | S | 4 | 4 |

| 321 | S. epidermidis | ELH | R | S | S | R | R | S | R | S | R | R | S | 0.75 | 3 |

| 327 | S. epidermidis | ELH | R | I | S | R | S | S | R | S | R | R | S | 0.75 | 2 |

| 329 | S. epidermidis | ELH | R | S | S | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | S | 0.75 | 8 |

| 343 | S. cohnii | ELH | R | S | S | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | S | 1.5 | 12 |

| 349 | S. cohnii | ELH | R | S | S | R | R | S | R | S | R | R | S | 1.5 | 12 |

| 355 | S. epidermidis | ELH | R | S | S | R | R | S | R | S | R | R | S | 0.5 | 3 |

| 361 | S. haemolyticus | ELH | S | S | S | R | S | S | R | S | R | R | S | 0.38 | 4 |

| 372 | S. hominis | ELH | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | S | S | R | S | 0.25 | 6 |

| 373 | S. haemolyticus | ELH | R | S | S | R | S | S | R | S | S | R | S | 1 | 8 |

| 385 | S. hominis | ELH | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | S | S | R | S | 0.125 | 1.5 |

| 386 | S. hominis | ELH | R | S | S | R | R | S | R | S | R | R | S | 4 | 0.38 |

| 387 | S. hominis | ELH | S | S | R | R | R | S | R | S | R | R | S | 0.064 | 16 |

| 407 | S. epidermidis | ELH | R | S | S | R | S | S | R | S | R | R | S | 0.5 | 4 |

| 435 | S. epidermidis | WLH | R | R | S | R | S | S | R | R | R | R | S | 1 | 6 |

| 436 | S. epidermidis | WLH | R | S | S | R | R | R | R | S | S | R | S | 1.5 | 8 |

| 445 | S. haemolyticus | WLH | R | S | I | R | R | S | R | S | S | R | R | 4 | 4 |

| 465 | S. epidermidis | WLH | S | S | S | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | 0.38 | 2 |

| 475 | S. epidermidis | WLH | R | S | R | S | R | S | R | R | R | R | S | 2 | 12 |

| 479 | S. hominis | WLH | R | S | S | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | S | 1.5 | 16 |

| 492 | S. haemolyticus | WLH | R | S | S | S | S | S | R | S | S | R | S | 0.75 | 8 |

| 506 | S. haemolyticus | WLH | R | S | S | R | R | R | R | R | S | R | S | 4 | 12 |

| 538 | S. haemolyticus | WLH | R | S | S | R | I | S | R | R | R | R | R | 0.5 | 6 |

| 620 | S. hominis | WLH | R | S | S | R | S | S | R | S | S | R | S | 3 | 16 |

| 623 | S. hominis | WLH | R | S | S | R | S | S | R | S | S | R | S | 2 | 24 |

| 631 | S. epidermidis | WLH | R | R | S | R | R | S | R | I | R | R | S | 3 | 16 |

| 664 | S. epidermidis | WLH | R | S | S | R | S | S | R | S | S | R | S | 2 | 6 |

| 673 | S. epidermidis | WLH | R | R | S | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | S | 4 | 3 |

| 699 | S. warneri | WLH | R | S | S | R | S | S | R | S | S | R | S | 3 | 8 |

| 700 | S. warneri | WLH | R | S | S | R | R | S | R | S | S | R | S | 4 | 6 |

| 702 | S. warneri | WLH | R | S | S | R | R | S | R | S | S | R | S | 2 | 12 |

| 711 | S. epidermidis | WLH | R | R | S | R | R | R | R | S | S | R | R | 12 | 24 |

| 712 | S. epidermidis | WLH | R | R | S | R | R | R | R | S | S | R | R | 12 | 24 |

| 713 | S. epidermidis | WLH | R | R | S | R | R | R | R | S | S | R | R | 256 | 12 |

| 715 | S. epidermidis | WLH | R | S | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | R | R | 256 | 12 |

| 716 | S. epidermidis | WLH | R | S | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | R | R | 256 | 12 |

R = resistant; I = intermediate resistance, S = sensitive; Oxa = oxacillin; Gen = gentamycin; Mup = mupirocin; Amx = amoxicillin; Erm = erythromycin; tet = tetracycline; Fox = cefoxitin; Fen = cefepime, Fua = fusidic acid; Pen = penicillin; Chl = chloramphenicol ELC = East London Community; WLC = West London Community; ELH = East London Hospital; WLH = West London hospital.

Prevalence of antibiotic genes from WGS data

The mecA gene was found in 43 out of 49 isolates that were whole genome sequenced. Of these none of S. sciuri isolates carried the mecA gene. Instead, they carried the mecA1 gene, which had only 84.43% homology to mecA gene.

Apart from the mecA, 24 other antibiotic resistant genes were detected in 43 isolates (Fig. 2). BlaZ was the most commonly found resistance gene with 39 isolates (90.7%) followed by qacA/B with 22 (51.16%); dfrC with 18 (41.86%), norA with 17, ant(4′)-Ib with 17 (39.53%); AAC(6′)-Ie-APH(2”)-Ia with 15 (34.88%), fusB with 14 (32.56%), msrA with 13 (30.23%), ermC with 12 (27.91%), mphC with 9 (27.64%), tetK 8 (18.6%), mupA with 7 (16.28%), cat with 6 (13.95%), dfrG with 5 (11.63%), mgrA with 5 (9%), lnuA with 4 (9.30%), fusC 3 (6.98%), aph3-IIIa 3(6.98%) and, sat4A, vgaA, vatB which were all found in 1 isolate (2.33%).

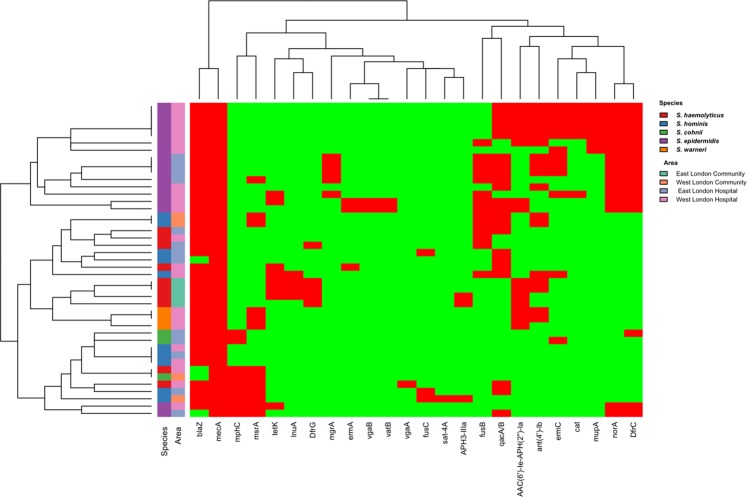

Figure 2.

Heatmap showing hierarchical clustering of isolates resistant gene profiles in comparison with the species and area they were isolated from. Red tiles indicate presence of antibiotic resistance genes; green tiles indicate absence of resistance gene.

From these 43 isolates, 3(6.98%) had two antibiotic resistant genes, 3(6.98%) had three antibiotic resistant genes, 7 (16.28%) had four antibiotic resistant genes, 2 (4.65%) had five antibiotic resistant genes, 7 (16.28%) had six antibiotic resistant genes, 2 (4.65%) had seven antibiotic resistant genes, 3(6.98%) had eight antibiotic resistant genes, 6(13.95%) had nine antibiotic resistant genes and 5 (11.63%) had ten antibiotic resistant genes (Fig. 2).

Hierarchical clustering within a heatmap of the mecA isolates resistance gene profile showed a clustering of 15 of the 17 S. epidermidis isolates as well as all S. warneri isolates and S. haemolyticus from East London community (Fig. 2). Interestingly, all S. epidermidis isolates carried the norA and dfrC genes.

Barnard Exact test analysis showed that there was a significantly higher proportion of isolates with the dfrG gene (P = 0.0054) in East London (29.41%) compared to West London (0%) (Table 4). In addition, there was a significant higher proportion of isolates with the cat (P = 0.0419) and mup genes (P = 0.0238) in West London (23.08% and 26.92% respectfully) compared to East London (both 0%).

Table 4.

The proportion of antibiotic resistance genes in isolates recovered from East and West London that possessed the mecA gene.

| Antibiotic resistance genes | East London | West London | Barnard Exact test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of samples WGS (N = 17) | Total number of isolate WGS (N = 26) | |||||

| % of total number of samples | % of total number of samples | Difference | P value | |||

| N | WGS | N | WGS | |||

| blaZ | 15 | 88.24 | 24 | 92.31 | 4.07 | 0.7224 |

| tetK | 3 | 17.65 | 11 | 19.23 | 1.58 | 0.9565 |

| ant(4′)-Ib | 5 | 29.41 | 12 | 46.15 | 16.74 | 0.3766 |

| AAC(6′)-Ie-APH(2″)-Ia | 4 | 23.53 | 11 | 42.31 | 18.78 | 0.2291 |

| aph3-IIIa | 2 | 11.76 | 1 | 3.85 | 7.91 | 0.4623 |

| lnuA | 3 | 17.65 | 1 | 3.85 | 13.8 | 0.1749 |

| DfrG | 5 | 29.41 | 0 | 0 | 29.41 | 0.0054 |

| DfrC | 6 | 35.29 | 12 | 46.15 | 10.86 | 0.7546 |

| fusB | 6 | 35.29 | 8 | 30.77 | 4.52 | 0.6665 |

| fusC | 2 | 11.76 | 1 | 3.85 | 7.92 | 0.4623 |

| qac | 9 | 52.94 | 13 | 50 | 2.94 | 0.9565 |

| msrA | 3 | 17.65 | 10 | 38.46 | 20.81 | 0.2175 |

| Sat4A | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.85 | 3.85 | 0.4872 |

| mphC | 3 | 17.65 | 5 | 19.23 | 1.58 | 0.9565 |

| norA | 5 | 29.41 | 12 | 46.15 | 16.74 | 0.3766 |

| mgrA | 4 | 23.53 | 1 | 3.85 | 19.68 | 0.0657 |

| ermA | 0 | 0 | 3 | 11.54 | 11.54 | 0.2065 |

| ermC | 4 | 23.53 | 8 | 30.77 | 7.24 | 0.7224 |

| mupA | 0 | 0 | 7 | 26.92 | 26.92 | 0.0238 |

| cat | 0 | 0 | 6 | 23.08 | 23.08 | 0.0419 |

| vgaA | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.85 | 3.85 | 0.4872 |

| vgaB | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7.69 | 7.69 | 0.3766 |

| vatB | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7.69 | 7.69 | 0.3766 |

For general public settings there was a significant higher proportion of aph2-III (P = 0.024), lnuA (P = 0.0116) and dfrG genes (P = 0.0031) (25%; 37.5% and 50% respectively) compared to public areas in hospitals (0%; 0% and 2.86% respectfully) (Table 5). The opposite was observed in isolates carrying the dfrC (P = 0.0238), and norA genes (P = 0.0238) with a significantly higher proportion found in public areas in hospitals (51.43% and 48.57% respectively) compared with general public settings (both 0%).

Table 5.

The proportion of antibiotic resistant genes in isolates recovered from general public setting and public areas in hospitals that possessed the mecA gene.

| Antibiotic resistance genes | General public settings | Public areas in hospitals | Barnard Exact test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of samples WGS (N = 8) | Total number of isolate WGS (N = 35) | |||||

| % of total number of samples | % of total number of samples | Difference | P value | |||

| N | WGS | N | WGS | |||

| blaZ | 7 | 87.5 | 32 | 91.43 | 3.93 | 1 |

| tetK | 3 | 37.5 | 5 | 14.29 | 23.21 | 0.1810 |

| ant(4′)-Ib | 4 | 50 | 12 | 37.14 | 12.86 | 0.8026 |

| AAC(6')-Ie-APH(2″)-Ia | 4 | 50 | 11 | 31.43 | 18.57 | 0.4519 |

| aph3-IIIa | 3 | 37.5 | 0 | 0 | 37.5 | 0.0024 |

| lnuA | 3 | 37.5 | 1 | 2.86 | 34.64 | 0.0116 |

| DfrG | 4 | 50 | 18 | 2.86 | 47.14 | 0.0031 |

| DfrC | 0 | 0 | 12 | 51.43 | 51.43 | 0.0238 |

| fusB | 6 | 25 | 2 | 25.71 | 0.71 | 1.0000 |

| fusC | 1 | 12.5 | 20 | 5.71 | 6.79 | 0.8026 |

| qacB | 2 | 25 | 9 | 57.14 | 32.14 | 0.1808 |

| msrA | 4 | 50 | 0 | 25.71 | 24.29 | 0.2078 |

| Sat4A | 1 | 12.5 | 7 | 0 | 12.5 | 0.1664 |

| mphC | 2 | 25 | 17 | 20 | 5 | 1.0000 |

| norA | 0 | 0 | 5 | 48.57 | 48.57 | 0.0238 |

| mgrA | 0 | 0 | 3 | 14.29 | 14.29 | 0.3686 |

| ermA | 0 | 0 | 12 | 8.57 | 8.57 | 0.5992 |

| ermC | 0 | 0 | 7 | 34.29 | 34.29 | 0.1664 |

| mupA | 0 | 0 | 6 | 20 | 20 | 0.1945 |

| cat | 0 | 0 | 1 | 17.14 | 17.14 | 0.2668 |

| vgaA | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.86 | 2.86 | 0.8160 |

| vgaB | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5.71 | 5.71 | 0.8026 |

| vatB | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5.71 | 5.71 | 0.8026 |

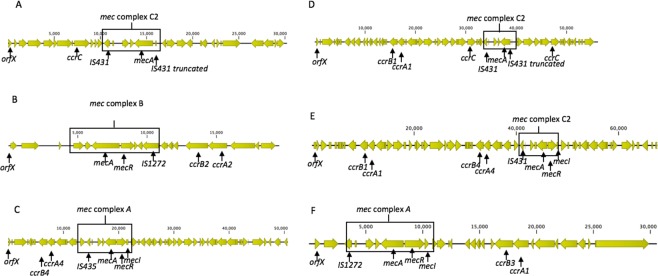

Determination of SCCmec types using WGS data

The SCCmec types were determined in 49 mecA positive isolates by mapping for genetic markers from whole genome sequencing data (Table 6). 17 (34.70%) of 49 isolates harboured previously reported SCCmec types. These included SCCmec type IV (n = 11) which was exclusively found in S. epidermidis isolates from public areas in hospitals; followed by SCCmec type V (n = 5) found in S. haemolyticus and S warneri and type VIII (n = 1) found in a S. hominis isolate. The SCCmec element was absent in the genomes of 6 (12.45%) isolates. 5 (10.20%) isolates harboured pseudo-SCCmec as they had mec complex but lacked the ccr complex and 3 (6.12%) isolates had an untypable mec complex. We could not assign SCCmec types for the remaining 21 (42.86%) isolates as they either had a novel combination of mec and ccr complexes (n = 5); or had multiple ccr complexes (n = 13) or novel ccr complexes (n = 2); or had an untypable mec complex (n = 1). A select few of these SCCmec structures is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Table 6.

The diversity of SCCmec types of the 49 coagulase negative staphylococci isolates recovered from public areas from the community and general public areas in hospitals.

| Sample no | Area | Species | mec complex | ccr complex | SCCmec type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ELC | S. haemolyticus | C2 | C | V |

| 27 | ELC | S. sciuri | No SCCmec element | ||

| 33 | ELC | S. sciuri | No SCCmec element | ||

| 59 | ELC | S. sciuri | No SCCmec element | ||

| 74 | ELC | S. sciuri | No SCCmec element | ||

| 75 | ELC | S. sciuri | No SCCmec element | ||

| 93 | ELC | S. haemolyticus | Untypable | Pseudo | |

| 99 | ELC | S. haemolyticus | C2 | C A1/B1 | Untypable |

| 105 | ELC | S. haemolyticus | C2 | C | V |

| 109 | ELC | S. sciuri | No SCCmec element | ||

| 207 | WLC | S. hominis | A | Pseudo | |

| 208 | WLC | S. hominis | A | A1/B1, A4/B4 | Untypable |

| 209 | WLC | S. hominis | A | A1/B1, A4/B4 | Untypable |

| 211 | WLC | S. cohnii | A | A1/B3 | Untypable |

| 321 | ELH | S. epidermidis | B | A2/B2 | IV |

| 327 | ELH | S. epidermidis | B | A2/B2 | IV |

| 329 | ELH | S. epidermidis | B | A2/B2 | IV |

| 343 | ELH | S. cohnii | A | A1, A3/B3 | Untypable |

| 349 | ELH | S. cohnii | A | A1, A3/B3 | Untypable |

| 355 | ELH | S. epidermidis | A | C, A2/B2 | Untypable |

| 361 | ELH | S. haemolyticus | C2 | Pseudo | |

| 372 | ELH | S. hominis | A | A1/B1 | Untypable |

| 373 | ELH | S. haemolyticus | Untypable | Pseudo | |

| 385 | ELH | S. hominis | A | C, A1/B3 | Untypable |

| 386 | ELH | S. hominis | A | A1/B1 | Untypable |

| 387 | ELH | S. hominis | C2 | A1/B1 | Untypable |

| 407 | ELH | S. epidermidis | C2 | C, A2/B2 | Untypable |

| 435 | WLH | S. epidermidis | A | C, A2/B2 | Untypable |

| 436 | WLH | S. epidermidis | B | C, A3/B3/, A4/B4 | Untypable |

| 445 | WLH | S. haemolyticus | A | A2/B2 | IV |

| 465 | WLH | S. epidermidis | B | A1/B1 | Untypable |

| 475 | WLH | S. epidermidis | A | A2/B2 | IV |

| 479 | WLH | S. hominis | A | A4/B4 | VIII |

| 492 | WLH | S. haemolyticus | Untypable | C B4/A4 | Untypable |

| 506 | WLH | S. haemolyticus | C2 | Pseudo | |

| 538 | WLH | S. haemolyticus | C2 | A4/B4 | Untypable |

| 620 | WLH | S. hominis | A | A1/B2 | Untypable |

| 623 | WLH | S. hominis | B | A1/B2 | Untypable |

| 631 | WLH | S. epidermidis | B | A2/B2 | IV |

| 664 | WLH | S. epidermidis | B | C A2/B2 | Untypable |

| 673 | WLH | S. epidermidis | C2 | C A2/B2 | Untypable |

| 699 | WLH | S. warneri | C2 | C | V |

| 700 | WLH | S warneri | C2 | C | V |

| 702 | WLH | S warneri | B | C | V |

| 711 | WLH | S. epidermidis | B | A2/B2 | IV |

| 712 | WLH | S. epidermidis | B | A2/B2 | IV |

| 713 | WLH | S. epidermidis | B | A2/B2 | IV |

| 715 | WLH | S. epidermidis | B | A2/B2 | IV |

| 716 | WLH | S. epidermidis | B | A2/B2 | IV |

ELC = East London Community; WLC = West London Community, ELH = East London Hospital; WLH = West London Hospital.

Figure 3.

A selection of SCCmec structures from staphylococci isolates recovered from high-frequency touched surfaces. (A) Isolate 1: S. haemolyticus SCCmec type V; (B) 475: S. epidermidis SCCmec type IV, (C) 479S. hominis SCCmec type VIII; (D) 99S. haemolyticus with mec C2 complex and ccrC, ccrA1/B1 complex; (E) 208S. hominis with a ccrA1/B1, ccrB4/A4 complex and (F) 211S. cohnii with a mec A complex and a ccrB3/A1 complex.

MLST typing for Staphylococcus epidermidis

MLST was determined for S. epidermidis isolates inferred from whole genome sequencing. 10 different sequence types (ST) were assigned to 17 S. epidermidis isolates (Table 7). ST2 was the most common (n = 5) sequence type, followed by ST66 (n = 3) and ST87 (n = 2). Two new sequence types were identified which have been assigned ST771 and ST779.

Table 7.

MLST types of S. epidermidis isolates.

| Sample No | Area | Sequence type (ST) |

|---|---|---|

| 321 | ELH | 66 |

| 327 | ELH | 66 |

| 329 | ELH | 66 |

| 355 | ELH | 558 |

| 407 | ELH | 59 |

| 435 | WLH | 188 |

| 436 | WLH | 771 |

| 465 | WLH | 54 |

| 475 | WLH | 5 |

| 631 | WLH | 87 |

| 664 | WLH | 779 |

| 673 | WLH | 87 |

| 711 | WLH | 2 |

| 712 | WLH | 2 |

| 713 | WLH | 2 |

| 715 | WLH | 2 |

| 716 | WLH | 2 |

ELH = East London Hospital; WLH = West London Hospital.

Discussion

Antibiotic resistance is a global public health concern. Increasingly, antibiotic resistant bacteria are emerging from different ecological niches5,7,8,10–12. It has been documented that surfaces in hospitals and non-hospital areas can be potential reservoirs for antibiotic resistant staphylococci, however studies comparing general public areas and that of public areas in hospitals are fragmentary8,26. In this study we compare the levels of antibiotic resistant staphylococci in general public areas and that of public areas in hospitals in two different geographical areas in London and provide insights into the molecular characterisation of these isolates.

281 multidrug resistant staphylococci isolates belonging to 11 species were identified in this study. The most prevalent species were S. epidermidis (n = 74) and S. haemolyticus (n = 61). S. epidermidis and S. haemolyticus have previously been reported as the most common CoNS isolated from surfaces in public settings and hospitals26. Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that S. aureus (n = 5) was less prevalent on high-frequency hand touched surfaces. This may be due to the fact that S. aureus is more commonly carried in the nasal passages than on hands27. S. aureus is the most virulent species of staphylococci and the most common cause of infection in hospitalised patients28. However, S. epidermidis, S. hominis and S. haemolyticus are amongst the most frequent nosocomial pathogens responsible for minor skin infections to life-threatening diseases1,29. In addition, community associated CoNS have also been reported to cause infections30.

Amongst the staphylococci isolates we detected increased susceptibilities toward penicillin (80.42%), fusidic acid (72.4%), and erythromycin (54.45%). Xu et al. reported increased susceptibilities toward penicillin, fusidic acid, erythromycin, and cefepime among staphylococci isolates recovered from surfaces of inanimate objects in London hotel rooms7. It has been reported that in primary care in England 48.8% of antibiotics prescribed were penicillin’s and 13.4% were macrolides, lincosamide and streptogramins31. The high usage of these antibiotics might relate to why it is common to see penicillin and erythromycin resistance from staphylococci isolates from general public settings.

Areas in East and West London harboured high levels of antibiotic resistant staphylococci in proportion to the number of isolates that were examined. Significantly higher proportion (P = 0.0002) of multidrug resistant staphylococci was observed from East London (56.7%) compared to West London (49.96%). This may be due to East London having a higher population density (9.7 thousand per square km; 2017 estimate) compared to West London (8.9 thousand per square km; 2017 estimate)32. Previous studies have shown that there is a linkage in population density to the development of antibiotic resistant33.

There was no difference in distribution of these multidrug resistant isolates at species level in two geographical areas at species level, apart from that S. warneri isolates were exclusively recovered from West London, but not from East London, whereas S. sciuri and S. equorum were recovered from East London only.

In this study, we isolated high levels of multidrug resistant staphylococci in public areas in hospitals and general public settings. Statistically, there was a significantly higher proportion (P = 0.0458) of multidrug resistant staphylococci in public areas in hospitals (49.5%) compared to that in general public settings (40.66%) which was expected due to the increase use of antibiotics in hospitals than in the community34. However, the proportions of multidrug resistant bacteria isolated from general public settings in our study (46.83%) were less than that reported in similar studies from a university campus in Thailand (61%) and hotel rooms in London (86%)7,11. In this study isolates were recovered from areas in hospitals that were accessible to the general public and not just to the hospital staff or patients. These areas included reception areas, public washrooms, corridors and lifts. The high levels of multidrug resistant staphylococci recovered from these areas in hospitals suggest a cross-contamination between community-associated and hospital-associated staphylococci.

We did not detect a significant difference in the carriage of mecA gene in isolates recovered from East (10.71%) and West London (7.18%) and from general public settings (7.69%) and public areas in a hospital (7.18%). The prevalence of the mecA gene in general public settings was less than that reported from the university campus in Thailand (20.5%) and hotel rooms in London (29.6%)7,11. In this study, the prevalence of the mecA gene in hospitals (7.89%) was also less than it was reported from a hospital in Thailand (70.1%). For the latter it was expected because of the high levels of antibiotic exposure as the isolates were recovered from the hospital wards in Thailand26.

Interestingly, we found that the 6 S. sciuri isolates that were resistant to oxacillin and were mecA positive (determined by PCR), carried a homolog of mecA designated as mecA1 (Table 3). mecA1 is considered to be the ancestry gene of mecA which historically did not have resistance towards oxacillin35. A recent study has shown that S. sciuri has developed oxacillin resistance using a variety of mechanisms from diversification of the non-binding domain of native PBPs, change in the mecA promoter, acquiring the SCCmec element and the adaptation of the bacterial genetic background36.

In this study we found that there was a large diversity of antibiotic resistant genes encoding resistance to different antibiotics. Of these genes, we found blaZ (90.7%) and qacA/B (51.16%) were the most common. Previous studies on the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance genes in CoNS from clinical and environmental sources are limited but some reports have shown that blaZ is of one the most common antibiotic resistance genes found in staphylococci37,38. QacA/B has been previously reported to high prevalence from University campus in Thailand (60.4%). This gene has an important role for the survival of the bacteria within the environment as they encode multidrug efflux pump which has shown cross resistance-towards antiseptic and disinfectant compounds used to reduce bacterial contamination from surfaces39.

In addition, we also found that S. epidermidis isolates were quite similar in their antibiotic resistance profile from our hierarchy clustering analysis even if they came from different areas. This may be due to that all isolates had the fluoroquinolone efflux pump gene norA and trimethoprim resistance dihydrofolate reductase gene dfrC40,41. It is possible that these genes are essential for S. epidermidis survival, especially as norA like qacA/B has shown reduce susceptibility to antiseptic and disinfectant substances.

SCCmec was detected in 36 out of the 49 isolates that were whole genome sequenced, however SCCmec types were assigned only to 17 isolates. The most common type was SCCmec type IV (n = 11), followed by SCCmec type V (n = 5) and SCCmec type VIII (n = 1). These results are consistent with previously reported studies of clinical and environmental isolates11. In our study SCCmec type IV was exclusively found in S. epidermidis isolates. This is in keeping with others reporting a high association between SCCmec type IV and S. epidermidis42. SCCmec type V was associated with S. haemolyticus and S. warneri isolates but is mainly reported to be associated with S. haemolyticus in clinical isolates43.

The remaining SCCmec types were untypeable as they harboured a novel ccr complex or multiple ccr complexes. Multiple ccr complexes have previously been described in clinical and community associated isolates42 but to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of such SCCmec types determined in isolates recovered from the general public environments. It has been reported that multiple ccr complexes have shown to produce more stable mecA mRNA transcription compared to single elements as well as having a better cell wall integrity42. This suggests that isolates with multiple ccr complexes may have increased susceptibilities to oxacillin or cefoxitin, however not always correlate with their phenotypic data. It is possible that this adaptation helps the bacteria to survive longer periods under persistent antibiotic pressure.

MLST data showed a wide range of genetic variability among S. epidermidis isolates. ST2 was the most common sequence type identified which was consistent with previous reports studying multidrug resistant clinical isolates24,25,44. Although in our study isolates that harboured ST2 sequence types were isolated from public areas in hospitals, others reported that this sequence type was widely disseminated in clinical isolates recovered from patients24,44,45. In addition, in this study two new sequence types designated as ST771 and ST779 were identified in isolates recovered from a hospital in West London.

In conclusion, general public areas and common public areas in hospitals in London can be reservoirs for multidrug resistant staphylococci. These multidrug resistant bacteria can be found at high levels on high-frequency touched surfaces. A diverse range of SCCmec types were determined from general public settings and public areas in hospitals of which many were untypeable due to having either a novel ccr or an extra ccr complex. These SCCmec structures have not been previously reported in isolates recovered from environmental surfaces in general public settings.

Additional comparative genomics analyses are being conducted to decipher the genetic features of multidrug resistant staphylococci recovered from general public settings and to further our understanding of the origin and evaluation of these isolates.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection and screening of staphylococcal isolates

Samples were recovered from high-frequency hand touched surfaces of inanimate objects (door handles, stair handrails, toilet flushers, toilet seats, taps, lift buttons, chair armrests) from four locations in general public settings, two locations from East London and two locations from West London. Public settings included shopping centres (concourses, escalators lifts, public washrooms) and train stations (entry gates, public washrooms, escalators). Isolates were also recovered from a hospital setting where the general public had easy access, without being a patient or visiting a patient (reception area, public washrooms, corridors, lifts) (Table S1). From each location, 50 areas were randomly sampled using COPAN dry swabs (Copan Diagnostics Inc., USA). In total 600 isolates were screened of which 224 were from East London and 376 from West London. 182 of the isolates were from the community area and 418 from Hospital area. 97 from East London community area and 85 from West London community. 224 from East London hospital and 376 from West London hospital.

All samples were inoculated onto mannitol salt agar (MSA, Oxoid Basingstoke, UK) within 1–3 hours of recovery and incubated aerobically for 24–72 hours at 37 °C. The colonies were then screened for potential staphylococci characteristics, including performing catalase and coagulase tests. Prolex™ staph latex kits (ProLab Diagnostics, Neston, UK) was used to distinguish S. aureus and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility testing

The samples were tested for their susceptibility against a panel of 11 antibiotics by using a standard disc diffusion method46. The antibiotics tested were the following: oxacillin (1 µg), gentamicin (10 µg), mupirocin (20 µg), amoxicillin (10 µg), erythromycin (15 µg), tetracycline (10 µg), cefoxitin (30 µg), cefepime (30 µg), fusidic acid (10 µg), penicillin (1 unit) and chloramphenicol (30 µg) (Mast Group, Merseyside, UK). Antibiotic profiles of each isolate ware determined according the recommendation of the Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (BSAC)46,47.

In addition, the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) for oxacillin and cefoxitin were determined using E-tests (Biomerieux, Basingstoke, UK)46,47.

Identification of multidrug-resistance staphylococci recovered from high-frequency hand touch areas

Potential staphylococci isolates were initially identified by conventional methods, including gram staining catalase and coagulase tests. All the isolates were identified at species level using Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight mass-spectroscopy (MALDI-TOF-MS, Microflex LT, Bruker Daltonics, Coventry, UK) in a positive linear mode (2000–20,000 m/z range). Samples were prepared as described previously7. MALDI-TOF Biotyper 3.0 software (Bruker Daltonics, Coventry, UK) was used to analyse the spectra and to identify the bacterial species. Bacterial test standard Escherichia coli DH5α (Bruker Daltonics, Coventry, UK) was used for calibration and as a standard for quality control.

Detection of mecA gene

The detection of the mecA gene was carried out by PCR for all staphylococci isolates. Freshly grown samples were suspended into 40 µl of sterile distilled water and boiled at 100 °C then cooled on ice for 5 minutes. The samples were then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 1 minute and the supernatant was used for the PCR providing the DNA template.

The PCR was performed using Met1 and Met2 primers as described previously48. PCR reactions were performed in a 20 µl volume for each sample which consists of 10 µl of Phusion Master Mix;1 µl of met1, 1 µl of met2, 6 µl of sterile distilled water and 1 µl of isolates DNA template. The PCR condition for this reaction was 94 °C for 5 minutes followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 52 °C for 30 seconds and extension at 72 °C for 1 minute with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 minutes.

WGS and bioinformatic analyses

Forty-nine staphylococci mecA positive isolates were whole genome sequenced using Illumina HiSeq platform. Thirteen out of 49 isolates were whole genome sequenced by MicrobesNG (Birmingham, UK) and the remining isolates were sequenced at Fudan University, Shanghai, China.

Genomic DNA was extracted using TIANamp Bacteria DNA kit (Tiangen, China) and paired-end sequencing libraries were constructed using Nextera XT DNA Sample Preparation kits or TruSeq DNA HT Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, USA) following manufacturer’s instruction. The short read sequencing data were deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive, under the study PRJEB30498. The accession numbers for individual samples are included in Supplementary data (Table S2).

The raw reads quality was assessed using FASTQC and trimmed using trimmomatic (Version 0.35), default settings, specifying a phred cutoff of Q2049,50. The trimmed reads were de novo assembly by SPAdes 3.11 and annotated by Prokka 1.1251,52.

The species of these isolates were confirmed by 16sRNA sequencing53. 16S rRNA sequences were extracted from assembled genomes using the barrnap software (https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap) and searched against a database of known 16S ribosomal RNA sequences using NCBI BLAST tool with a cutoff for species identity of 95% similarity54.Antibiotic resistance genes were detected using the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) server55.

The diversity of SCCmec types were determined by searching against a database of known SCCmec molecular markers with NCBI BLAST with a cutoff e-value of 1e-554,56.

S. epidermidis isolates were analysed by Multi locus sequence typing (MLST) and the sequence types for each isolate were assigned using MLST2.0 online service (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/MLST/)57.

Statistical analysis

A Chi-squared test was performed to identify any significant difference in the proportion of multidrug resistant staphylococci and mecA gene in isolates recovered from general public settings and public areas in hospitals in East and West London58. A P value of >0.05 was considered to be significant. Barnard Exact test was performed to identify significance in the proportion of antibiotic resitance genes form WGS sample recovered from general public settings and public areas in hospitals in East and West London59. A two side P value of >0.05 was considered to be significant. Hirachy clustering of a heatmap for resistance gene phentype and genotype were created using the R package ‘Heatmap.plus’ (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/heatmap.plus/index.html).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Rory Cave is funded by the UEL PhD studentship awarded to HVM.

Author Contributions

H.V.M.: conceptualization and design of the study; data analysis; writing and critically reviewing the paper. R.C.: samples collection, laboratory work, data analysis, manuscript preparation. R.M.: Data analysis, critically reviewing the paper. J.C.: WGS, data analysis, critically reviewing the paper. S.W.: WGS sample prep, reviewing the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-45886-6.

References

- 1.Huebner J, Goldmann DA. Coagulase-negative staphylococci: role as pathogens. Annu. Rev. Med. 1999;50:223–236. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tong SYC, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL, Fowler VG. Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015;28:603–661. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00134-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambers HF, DeLeo FR. Waves of Resistance: Staphylococcus aureus in the Antibiotic Era. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:629–641. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.John JF, Harvin AM. History and evolution of antibiotic resistance in coagulase-negative staphylococci: Susceptibility profiles of new anti-staphylococcal agents. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2007;3:1143–1152. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conceição T, Diamantino F, Coelho C, de Lencastre H, Aires-de-Sousa M. Contamination of Public Buses with MRSA in Lisbon, Portugal: A Possible Transmission Route of Major MRSA Clones within the Community. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e77812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.David MZ, Daum RS. Community-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Epidemiology and Clinical Consequences of an Emerging Epidemic. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010;23:616–687. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00081-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu, Z., Mkrtchyan, H. V. & Cutler, R. R. Antibiotic resistance and mecA characterization of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from three hotels in London, UK. Front. Microbiol. 6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Roberts, M. C., Soge, O. O. & No, D. Comparison of Multi-Drug Resistant Environmental Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Recreational Beaches and High Touch Surfaces in Built Environments. Front. Microbiol. 4 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Lutz JK, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in public transportation vehicles (buses): another piece to the epidemiologic puzzle. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2014;42:1285–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mkrtchyan, H. V., Russell, C. A., Wang, N. & Cutler, R. R. Could Public Restrooms Be an Environment for Bacterial Resistomes? Plos One8 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Seng R, Leungtongkam U, Thummeepak R, Chatdumrong W, Sitthisak S. High prevalence of methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from a university environment in Thailand. Int. Microbiol. Off. J. Span. Soc. Microbiol. 2017;20:65–73. doi: 10.2436/20.1501.01.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soge OO, Meschke JS, No DB, Roberts MC. Characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp. isolated from US West Coast public marine beaches. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009;64:1148–1155. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stepanović S, Cirković I, Djukić S, Vuković D, Svabić-Vlahović M. Public transport as a reservoir of methicillin-resistant staphylococci. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2008;47:339–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poole K. Bacterial stress responses as determinants of antimicrobial resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:2069–2089. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warnes SL, Highmore CJ, Keevil CW. Horizontal Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes on Abiotic Touch Surfaces: Implications for Public Health. mBio. 2012;3:e00489–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00489-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliveira DC, Tomasz A, de Lencastre H. Secrets of success of a human pathogen: molecular evolution of pandemic clones of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2002;2:180–189. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00227-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stapleton PD, Taylor PW. Methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Sci. Prog. 2002;85:57–72. doi: 10.3184/003685002783238870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elements (IWG-SCC), I. W. G. on the C. of S. C. C. Classification of Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome mec (SCCmec): Guidelines for Reporting Novel SCCmec Elements. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4961–4967. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00579-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li S, et al. Novel Types of Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome mec Elements Identified in Clonal Complex 398 Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3046–3050. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01475-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shore AC, et al. Detection of Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome mec Type XI Carrying Highly Divergent mecA, mecI, mecR1, blaZ, and ccr Genes in Human Clinical Isolates of Clonal Complex 130 Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus∇. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3765–3773. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00187-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maree CL, Daum RS, Boyle-Vavra S, Matayoshi K, Miller LG. Community-associated Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates and Healthcare-Associated Infections1. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007;13:236–242. doi: 10.3201/eid1302.060781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.International Working Group on the Classification of Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome Classification of Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome mec (SCCmec): Guidelines for Reporting Novel SCCmec Elements. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4961–4967. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00579-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sweeney MT, Lubbers BV, Schwarz S, Watts JL. Applying definitions for multidrug resistance, extensive drug resistance and pandrug resistance to clinically significant livestock and companion animal bacterial pathogens. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018;73:1460–1463. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Widerström M, McCullough CA, Coombs GW, Monsen T, Christiansen KJ. A Multidrug-Resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis Clone (ST2) Is an Ongoing Cause of Hospital-Acquired Infection in a Western Australian Hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012;50:2147–2151. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06456-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong Y, Speer CP, Glaser K. Beyond sepsis: Staphylococcus epidermidis is an underestimated but significant contributor to neonatal morbidity. Virulence. 2018;9:621–633. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2017.1419117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seng Rathanin, Kitti Thawatchai, Thummeepak Rapee, Kongthai Phattaraporn, Leungtongkam Udomluk, Wannalerdsakun Surat, Sitthisak Sutthirat. Biofilm formation of methicillin-resistant coagulase negative staphylococci (MR-CoNS) isolated from community and hospital environments. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(8):e0184172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tammelin A, Klötz F, Hambraeus A, Ståhle E, Ransjö U. Nasal and hand carriage of Staphylococcus aureus in staff at a Department for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery: endogenous or exogenous source? Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2003;24:686–689. doi: 10.1086/502277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu GY. Molecular Pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus Infection. Pediatr. Res. 2009;65:71R–77R. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819dc44d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basaglia G, Moras L, Bearz A, Scalone S, Paoli PD. Staphylococcus cohnii septicaemia in a patient with colon cancer. J. Med. Microbiol. 2003;52:101–102. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chu VH, et al. Emergence of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci as a Cause of Native Valve Endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;46:232–242. doi: 10.1086/524666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dolk FCK, Pouwels KB, Smith DRM, Robotham JV, Smieszek T. Antibiotics in primary care in England: which antibiotics are prescribed and for which conditions? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018;73:ii2–ii10. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park, N. Lower layer Super Output Area population estimates (supporting information) - Office for National Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Available at, https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/lowersuperoutputareamidyearpopulationestimates, (Accessed: 4th December 2018) (2017).

- 33.Bruinsma N, et al. Influence of population density on antibiotic resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003;51:385–390. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cantón R, Morosini M-I. Emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance following exposure to antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011;35:977–991. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ito T, et al. Guidelines for Reporting Novel mecA Gene Homologues. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:4997–4999. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01199-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rolo J, et al. Evidence for the evolutionary steps leading to mecA-mediated β-lactam resistance in staphylococci. PLOS Genet. 2017;13:e1006674. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klibi Amira, Maaroufi Abderrazek, Torres Carmen, Jouini Ahlem. Detection and characterization of methicillin-resistant and susceptible coagulase-negative staphylococci in milk from cows with clinical mastitis in Tunisia. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2018;52(6):930–935. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pedroso SHSP, et al. Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Isolated from Human Bloodstream Infections Showed Multidrug Resistance Profile. Microb. Drug Resist. Larchmt. N. 2018;24:635–647. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2017.0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang C, et al. Distribution of antiseptic-resistance genes qacA/B in clinical isolates of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in China. J. Hosp. Infect. 2008;69:393–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Costa SS, Viveiros M, Pomba C, Couto I. Active antimicrobial efflux in Staphylococcus epidermidis: building up of resistance to fluoroquinolones and biocides in a major opportunistic pathogen. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018;73:320–324. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Totake K, Kobayashi N, Odaka T. Trimethoprim resistance and susceptibility genes in Staphylococcus epidermidis. Microbiol. Immunol. 1998;42:497–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1998.tb02315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen, X.-P. et al. Extreme diversity and multiple SCCmec elements in coagulase-negative Staphylococcus found in the Clinic and Community in Beijing, China. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Zong, Z., Peng, C. & Lü, X. Diversity of SCCmec Elements in Methicillin-Resistant Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Clinical Isolates. Plos One6 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Deplano A, et al. National surveillance of Staphylococcus epidermidis recovered from bloodstream infections in Belgian hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016;71:1815–1819. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Du X, et al. Molecular Analysis of Staphylococcus epidermidis Strains Isolated from Community and Hospital Environments in China. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e62742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andrews JM, Howe RA. BSAC standardized disc susceptibility testing method (version 10) J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011;66:2726–2757. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.CSLI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2017).

- 48.Hanssen A-M, Kjeldsen G, Sollid JUE. Local Variants of Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome mec in Sporadic Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Methicillin-Resistant Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci: Evidence of Horizontal Gene Transfer? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:285–296. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.1.285-296.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andrews, S. FastQC A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. In 175–176 (Babraham Institute, Cambridge, UK., 2011).

- 50.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bankevich A, et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Janda JM, Abbott SL. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing for Bacterial Identification in the Diagnostic Laboratory: Pluses, Perils, and Pitfalls. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007;45:2761–2764. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01228-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jia B, et al. CARD 2017: expansion and model-centric curation of the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D566–D573. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Monecke S, et al. Diversity of SCCmec Elements in Staphylococcus aureus as Observed in South-Eastern Germany. PLOS ONE. 2016;11:e0162654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thomas JC, et al. Improved multilocus sequence typing scheme for Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007;45:616–619. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01934-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Campbell I. Chi-squared and Fisher-Irwin tests of two-by-two tables with small sample recommendations. Stat. Med. 2007;26:3661–3675. doi: 10.1002/sim.2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barnard GA. A New Test for 2 × 2 Tables. Nature. 1945;156:177. doi: 10.1038/156177a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.