Abstract

This study compared the modified Soxhlet (Soxtec) and Folch extraction methods for determining the total lipid or intramuscular fat (IMF) content of aged beef samples. Ageing periods tested were 0, 5, 8, 10 and 12 weeks during which samples were held in vacuo and at ~ 1.0 °C. Prior to solvent extraction, all samples were freeze-dried and ground. The Folch method was found to result in higher IMF values and therefore higher extraction efficiency when compared to the Soxtec. A linear relationship was evident between the two methods that described 80.9% of the variation between IMF values. An interaction between ageing period and extraction method was identified, although ageing period did not independently impact on averaged IMF findings. Based on these observations and reagent toxicity not being a limiting factor, it is recommended that the Folch extraction method be used to determine beef IMF, although it is acknowledged that the Soxtec method IMF results were strongly aligned with those found using the Folch extraction method and tended towards comparability for beef aged < 5 weeks.

Keywords: Intramuscular fat, Beef, Total lipid, Ageing period, Randall method

Introduction

Intramuscular fat (IMF) refers to the total lipid or crude fat content of trimmed beef, and is important to our understanding of beef’s organoleptic and nutritional properties. Research of this association includes findings that IMF content is indicative of beef juiciness (Aldai et al. 2006), as IMF was negatively associated with drip loss; Serra et al. (2004) used trained sensory panellists to show that IMF, odour and flavour have a positive relationship in 14 days aged beef samples; and Nishimura et al. (1999) reported IMF to impact on beef tenderness as a result of myofibril disruptions caused from adipose tissue formation within endomysium structures—albeit this was observed in heavily marbled muscles. From this relationship, a 3–4% IMF lower limit for consumer acceptability for beef has been defined (Savell and Cross 1988), which interestingly proved similar to the 5% IMF limit later defined for sheep meat (Hopkins et al. 2006). It is also noteworthy that IMF provides a major source of essential fatty acids and a significant component of the nutritional value for beef products which are desired by consumers (Valsta et al. 2005). Apparent from these observations and associations, is a requirement for confidence in the results of any total lipid determination method to reliably represent the IMF status of a beef sample.

There are numerous approaches used to measure total lipid content. These often adhere to a generalised methodological pathway of (1) sample preparation; (2) solvent extraction; (3) purification of lipid fraction; and (4) data integration or calculation. Of these, solvent extraction is considered a critical phase for IMF analysis of meat samples (Sahasrabudhe and Smallbone 1983). To this end, the Folch method (Folch et al. 1957) was developed to use a chloroform–methanol–water phase system to extract lipids, but has somewhat lost favour in the scientific community because of its comparative expense (labour and reagents) and its use of more hazardous chemicals (Reuber 1979). The Soxhlet method (FOSS 2003) instead was designed to use a less toxic hydrocarbon solvent, hexane and a Soxtec extractor to isolate sample lipids, increasing sample throughput times and resource use efficiencies (Thiex et al. 2003). Differences in the results of these two methods have been reported. Indeed, Pérez-Palacios et al. (2008) reported Folch extraction efficiencies to be better than Soxhlet when testing whole muscle beef samples; Brooks et al. (1998) found minor discrepancies when comparing chlorinated and hydrocarbon solvents to determine total carcass lipid content of rats; and Segura and Lopez-Bote (2014) used pork samples to conclude that method extraction efficiency is dependent on the relative fattiness of a sample. The basis for these discrepancies was reported to be the variety of form, content and complexity of the lipid profile. Overcoming these limitations has prompted modification to these original methods and consequently created an imperative; to compare the results of these modified extraction methods when using them to quantify the total lipid content of beef samples.

In response, this study aimed to test the effects of a modified Soxhlet extraction method compared to the Folch method when determining the IMF content of aged, trimmed, freeze-dried and ground beef samples.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

A total of eight beef striploins (M. longissimus lumborum) were selected at random from the boning room of a commercial Australian abattoir. All striploins were from grass-fed assurance programs and processed as per industry norm. Each loin was divided into five equal portions that were individually vacuum-packaged and assigned to one of five ageing periods (0, 5, 8, 10 or 12 weeks). Samples were held, chilled (mean ± standard deviation: 1.49 ± 0.80 °C) with allocation randomised, and balanced so that n = 4 per ageing period per chiller and n = 40 in total. All samples were sectioned at the completion of their ageing period and held at − 80 °C until analysis so as to inhibit further oxidation.

Prior to lipid extraction, approximately 25.0 g samples were freeze-dried at − 50 °C (ScanVac CoolSafe™, LaboGene Ltd., Lynge, DEN) and ground using a sample mill (model 1095, Knifetech™, FOSS Pacific Ltd., New South Wales, AUS) to generate a homogenous sample.

Soxhlet extraction method

This Soxhlet extraction protocol followed the method of Hopkins et al. (2014). This used an extraction unit (ST 255 Soxtec™, FOSS Analytical Solutions Pty. Ltd., Victoria, AUS) and 2.5 g freeze-dried sample placed in a porous thimble and extracted in 85 mL hexane for 60 min within individual extraction tins (FOSS 2003). The residue was allowed to evaporate for a further for 20 min, before being placed in a forced draft oven for 30 min at 105 °C so as to further remove (vaporise) any residual solvent. The variation in sample weight before and after extraction was used to calculate crude fat content as per Thiex et al. (2003), and then expressed as a percentage of fresh (wet) sample weight (IMF).

Folch extraction method

The method of Folch et al. (1957) was modified so that 0.5 g freeze-dried sample was combined with 10.0 mL chloroform:methanol (2:1 v/v) in a glass screw top test tube. Tubes were then vortexed for 30 s before being agitated for 15 min in an orbital shaker at room temperature (~ 25 °C). Following this tubes were centrifuged at 1500×g for 15 min before the majority of the chloroform:methanol solution was carefully decanted, ensuring that all solid material remained in the bottom of the tube. Tubes were then evaporated to dryness in a fume cupboard. Once dry, 10.0 mL of hexane added to each tube and these vortexed and allowed to settle before eluent was again poured off and tubes permitted to once again dry. This process was then repeated before dry tubes and residue were weighed, IMF calculated and it expressed as a percentage of fresh (wet) sample weight.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using a simple linear regression model (Genstat 19th Edition, VSN International Ltd., www.vsni.co.uk) with Soxhlet extraction method as the response variate and Folch extraction method as the fitted term. Using this same software package, data were also analysed using a linear mixed model with extraction method, ageing period and their interaction fitted as fixed effects; and with striploin, portion within striploin and their interaction as random effects. Differences between predicted means were considered to be significant when P < 0.05.

Results and discussion

The summary data shown in Table 1 demonstrates the range of IMF values observed and included in this study.

Table 1.

Summary Soxhlet and Folch extraction method data of beef M. longissimus lumborum samples aged for different chilled storage periods, up to 12 weeks

| n | Mean | Range | Median | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soxhlet method | 48 | 2.54 | 1.28–3.89 | 2.49 | 0.61 |

| Folch method | 47 | 2.84 | 1.72–4.01 | 2.90 | 0.59 |

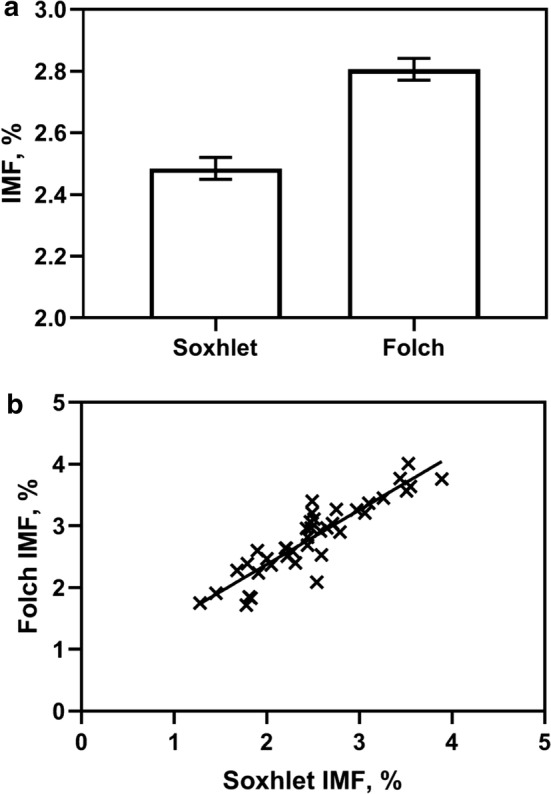

This study found beef sample IMF results to be highest when the Folch extraction method was used, comparative to the Soxhlet method (2.81 ± 0.04% vs 2.49 ± 0.04%, respectively; P < 0.001; Fig. 1a). Doing so, this observation has provided support to the conclusions of past research (Silva et al. 2015). For example, Tanamati et al. (2005) also reported the Soxhlet method to have a lower extraction efficiency than the Folch method. A suggested basis for this difference is the hexane solvent being less effective at isolating the polar lipid fraction from beef or tissue samples. The polar lipid fraction refers to lipoproteins, phospholipids and similar conjugated lipids—opposed to the neutral triglycerides, free fatty acids, mono- and diglycerides, and sterols that belong to the non-polar category (Sahasrabudhe and Smallbone 1983). Characteristic of polar lipids are their strong linkages between fats and proteins that can inhibit their extraction, unless a solvent is used with sufficient polarity to overcome these bonds, such as a miscible mixture of polar and non-polar solvents such as those found in the Folch method. That said, caution is recommended when selecting an extraction solvent as excessive polarity could suppress solubilisation of non-polar lipids, such as triacylglycerol, to the detriment of IMF representation (Iverson et al. 2001). Nonetheless, the implications of a failure to capture the polar lipid fraction on understanding the fatty acid composition of beef—specifically health claimable long chain fatty acids that are prolific within phospholipid structures—are a potential concern. This has already been demonstrated with Xiao et al. (2012) finding lower levels of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) fatty acids to be extracted when a Soxhlet extraction method was used comparative to the Bligh and Dyer method, another extraction method that similarly to the Folch method uses a chloroform based solvent.

Fig. 1.

The intramuscular fat content (IMF) of aged beef M. longissimus lumboruma the effect of extraction method (Soxhlet and Folch) with predicted mean ± standard error (bars) plotted; and b the relationship between IMF values determined using these same extraction methods (Soxhlet and Folch) with a linear trend line included

An alternate basis for the difference between Soxhlet and Folch extraction methods could be differences in the amount and therefore the fattiness of the sample combined with the solvent. As Iverson et al. (2001) suggests, it is critical to maintain a lipid concentration to organic phase ratio—that is, as sample fat content increases, so should the volume of extraction solvent—because failure to do so will increase the risk of organic phase saturation, incomplete lipid isolation, and an underestimation of IMF values. The findings of Thiex et al. (2003) illustrate this potential masking of actual total lipid content by showing that the extraction efficiency of low fat animal feed rations was reduced when an additional 100% fat supplement was included. In terms of a beef sample, this position lends itself to the previous discussion of method difference in their extraction efficiency of polar lipids, as samples with lower total lipid content would have a higher ratio of polar to non-polar lipids (Xiao et al. 2012).

It should be acknowledged that even if there was a difference in polar lipid isolation efficiency between methods, we could expect relatively comparable IMF results because of their mutual extraction of non-polar lipid fractions. This is illustrated by the linear relationship found between Folch and Soxhlet extraction methods (P < 0.001) that accounted for 80.9 ± 0.27% of the variance (Fig. 1b). Investigations with pork resulted in comparable results, with Ragland et al. (1996) reporting a correlation coefficient of 0.84 observed between a Soxhlet method, albeit using a petroleum ether solvent rather than hexane as per this study, and a Bligh and Dyer extraction method.

The found similarity between extraction methods could result from the freeze-drying and mechanical grinding when experimental samples were prepared, prior to solvent extraction. These actions may have made sample fat stores more assessable to both extraction solvents and in the case of hexane, improved is efficiency by physically breaking the protein-fat bonds of conjugated polar lipids that would have remained intact if whole beef samples were tested (Pérez-Palacios et al. 2008). Past research using freeze-dried meat samples supports this position, having concluded that both chlorinated and hydrocarbon solvents could be used to effectively extract sample lipid fractions (Sahasrabudhe and Smallbone 1983). Furthermore, it could be inferred that a similar pathway would result from proteolytic actions known to continue through a chilled storage, ageing period (Coombs et al. 2017). This could explain the interaction between ageing period and extraction method on sample IMF values (P = 0.003; Fig. 2)—whereby IMF values determined using the Folch extraction method were shown to increase with increased ageing. That said, when extraction method data was averaged, ageing period was shown not to impact on beef IMF (P = 0.257). This outcome reflects the collective results of much past research (Mahecha et al. 2009; Ba et al. 2014; Holman et al. 2017) and doing so, provides credence to the representativeness of this study.

Fig. 2.

The effect of extraction method (Soxhlet and Folch) on the intramuscular fat content (IMF) values for beef M. longissimus lumborum samples aged for up to 12 weeks. Predicted mean ± standard error (bars) are plotted

Conclusion

From these results, the Folch extraction method was found to provide a better representation of aged beef total lipid (IMF) content and is therefore recommended. This statement is constrained to analytics where reagent toxicity, amount and throughput speed are not limiting factors. In these instances, it would be advantageous to instead use the Soxhlet method—especially as it provided comparable IMF results for beef aged < 5 weeks and its results had a strong linear relationship to Folch extraction method results.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Graham Centre for Agricultural Innovation for the Member Support Grant—Category 2 funds. The support of the NSW Department of Primary Industries (NSW DPI) and our abattoir collaborators is also acknowledged.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aldai N, Murray BE, Olivan M, Martinez A, Troy DJ, Osoro K, Najera AI. The influence of breed and mh-genotype of carcass conformation, meat physico-chemical characteristics, and the fatty acid profile of muscle from yearling bulls. Meat Sci. 2006;72:486–495. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ba HV, Park KM, Dashmaa D, Hwang IH. Effect of muscle type and vacuum chiller ageing period on the chemical composition, meat quality, sensory attributes and volatile compounds of Korean native cattle beef. Anim Sci J. 2014;85:164–173. doi: 10.1111/asj.12100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SPJ, Ratnayake WMN, Lampi BJ, Hollywood R. Measuring total lipid content in rat carcasses: a comparison of commonly employed extraction methods. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:4214–4217. doi: 10.1021/jf980052w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs CEO, Holman BWB, Friend MA, Hopkins DL. Long-term red meat preservation using chilled and frozen storage combinations: a review. Meat Sci. 2017;125:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2016.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lee M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOSS (2003) Hexane extraction of fat in feed, cereal grain and forage. FOSS, pp 1–9

- Holman BWB, Coombs CEO, Morris S, Kerr MJ, Hopkins DL. Effect of long term chilled (up to 5 weeks) then frozen (up to 12 months) storage at two different sub-zero holding temperatures on beef: 1. Meat quality and microbial loads. Meat Sci. 2017;133:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2017.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins DL, Hegarty RS, Walker PJ, Pethick DW. Relationship between animal age, intramuscular fat, cooking loss, pH, shear force and eating quality of aged meat from sheep. Anim Prod Sci. 2006;46:879–884. doi: 10.1071/EA05311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins DL, Clayton EH, Lamb TA, Van de Ven RJ, Refshauge G, Kerr MJ, Bailes K, Lewandowski P, Ponnampalam EN. The impact of supplementing lambs with algae on growth, meat traits and oxidative status. Meat Sci. 2014;98:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson SJ, Lang SLC, Cooper MH. Comparison of the Bligh and Dyer and Folch methods for total lipid determination in a broad range of marine tissue. Lipids. 2001;36:1283–1287. doi: 10.1007/s11745-001-0843-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahecha L, Nuernberg K, Nuernberg G, Ender K, Hagemann E, Dannenberger D. Effects of diet and storage on fatty acid profile, micronutrients and quality of muscle from German Simmental bulls. Meat Sci. 2009;82:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Hattori A, Takahashi K. Structural changes in intramuscular connective tissue during the fattening of Japanese black cattle: effect of marbling on beef tenderization. J Anim Sci. 1999;77:93–104. doi: 10.2527/1999.77193x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Palacios T, Ruiz J, Martín D, Muriel E, Antequera T. Comparison of different methods for total lipid quantification in meat and meat products. Food Chem. 2008;110:1025–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragland KD, Christian LL, Baas TJ. Comparison of methods for evaluation of chemical lipid content in the longissimus muscle. Ames: Iowa Stat University; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Reuber MD. Carcinogenicity of chloroform. Environ Health Perspect. 1979;31:171–182. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7931171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahasrabudhe MR, Smallbone BW. Comparative evaluation of solvent extraction methods for the determination of neutral and polar lipids in beef. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1983;60:801–805. doi: 10.1007/BF02787431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savell JW, Cross HR. The role of fat in the palatability of beef, pork, and lamb. In: National Research Council (US) Committee on Technological Options to Improve the Nutritional Attributes of Animal Products, editor. Designing foods: animal product options in the marketplace. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1988. pp. 345–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segura J, Lopez-Bote CJ. A laboratory efficient method for intramuscular fat analysis. Food Chem. 2014;145:821–825. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.08.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra X, Gil M, Gispert M, Guerrero L, Oliver MA, Sanudo C, Campo MM, Panea B, Olleta JL, Quintanilla R, Piedrafita J. Characterisation of young bulls of the Bruna dels Pirineus cattle breed (selected from old Brown Swiss) in relation to carcass, meat quality and biochemical traits. Meat Sci. 2004;66:425–436. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1740(03)00131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva SR, Teixeira A, Furnols MF. Intramuscular fat and marbling. In: Font-i-Furnols M, Candek-Potokar M, Maltin C, Prevolnik Povše M, editors. A handbook of reference methods for meat quality assessment. Ingliston: European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST); 2015. pp. 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Tanamati A, Oliveira CC, Visentainer JV, Matsushita M, de Souza NE. Comparative study of total lipids in beef using chlorinated solvent and low-toxicity solvent methods. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2005;82:393–397. doi: 10.1007/s11746-005-1083-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thiex NJ, Anderson S, Gildemeister B. Crude fat, hexanes extraction, in feed, cereal grain, and forage (Randall/Soxtec/Submersion method): collaborative study. J Assoc Off Agric Chem Int. 2003;86:899–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valsta LM, Tapanainen H, Mannisto S. Meat fats in nutrition. Meat Sci. 2005;70:525–530. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Mjøs SA, Haugsgjerd BO. Efficiencies of three common lipid extraction methods evaluated by calculating mass balances of the fatty acids. J Food Compos Anal. 2012;25:198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2011.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]