Abstract

Pain from traumatic rib fractures presents a source of major morbidity and mortality. Prior studies have reported 59% of patients continue to have persistent pain at 2 months post injury. Most modern analgesia modalities have short duration of effect (<72 h) and require repeated doses to achieve adequate effect. There are few studies that address long-term analgesia treatment for these injuries. Intercostal cryoneurolysis (IC) is a technique of long-term chest wall analgesia previously studied in thoracic surgery and pediatric chest wall reconstruction. This technique may also be an effective treatment for rib fracture pain. Presented is a case of successful control of rib fracture pain with IC used as an adjunct to surgical stabilization of rib fractures (SSRF). This is followed by a discussion of IC's role in the treatment of traumatic rib fracture pain.

Keywords: Rib fracture pain, Rib fracture analgesia, Intercostal cryoneurolysis, Intercostal nerve cryoablation, Rib fracture fixation, Traumatic rib fracture

Introduction

Traumatic rib fractures are associated with severe pain, which is the source of major morbidity and mortality [1,2]. Intercostal cryoneurolysis (IC) may be a useful adjunct for long-term analgesia of traumatic rib fracture pain. Cryoneurolysis causes axonotmesis resulting in numbness distal to the lesion. Regeneration of the nerve occurs along the remaining perineural structures. Presented is a case of successful control of pain associated with severely displaced rib fractures by surgical stabilization of rib fractures (SSRF) combined with IC followed by a discussion of IC for traumatic rib fracture pain.

Case report

An otherwise healthy 50-year-old active female presented to the emergency department (ED) following a fall down a steep, 70-foot embankment that occurred while hiking. A full assessment was conducted upon arrival in accordance with ATLS guidelines. She had no respiratory or hemodynamic compromise. Injuries included a left sided hemopneumothorax with associated severely displaced lateral left 3rd through 6th rib fractures (Fig. 1), a right wrist Galeazzi fracture, a comminuted left clavicle fracture, a nondisplaced left scapula fracture, a C2 vertebral body fracture with extension to the left lateral mass and right inferior articular facet, T12 and L3 superior endplate compression fractures with minimal height loss, and minimally displaced right iliac wing and sacral fractures.

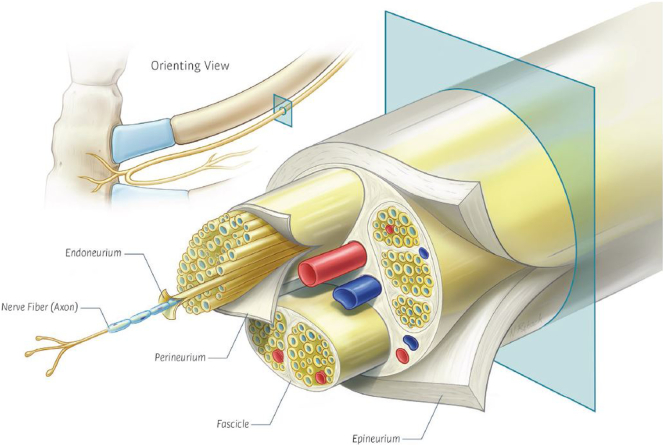

Fig. 1.

3D reconstruction of CT chest showing severely displaced fractures of left ribs 3 through 6.

In the ED, a 24 French left chest tube was placed with return of air and 50 mL of blood. She was hospitalized and started on multi-modal analgesia in accordance with our institution's rib fracture analgesia protocol including scheduled acetaminophen, gabapentin, lidocaine patches, and IV fentanyl as needed. She was taken to the operating room the following morning for open reduction and internal fixation of her right wrist fracture. Her fentanyl was converted to a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) device upon return to the hospital ward.

By the morning of post-injury day 2, she continued to be bothered by pain associated with her rib fractures. This pain required ongoing narcotic pain medication and prevented adequate participation in her prescribed pulmonary physiotherapy. We felt that non-operative treatment of her severely displaced fracture pattern may lead to chronic pain and compromised pulmonary function. We recommended that she undergo left sided IC for adjunctive pain control in addition to SSRF for anatomical chest wall fixation. After a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits, the patient gave consent to proceed.

She was taken to the operating room on post-injury day 3 for SSRF with IC. Fractures of left ribs 3 through 6 were reduced and fixated with titanium plates (L1 Rib, KLS Martin North America, Jacksonville, FL, USA). A two-port video-assisted thoracoscopy was then performed. A small retained hemothorax was evacuated. Intercostal nerves 3–7 were identified thoracoscopically and cryoablated approximately 4 cm lateral to the spine. Our technique of cryoneurolysis uses a thoracoscopically inserted cryoanalgesia probe (CRYO2, AtriCure, Mason, OH, USA) that is applied directly to the neurovascular bundle at −60 °C for 120 s per intercostal nerve. The process was repeated until all desired intercostal levels were treated (Fig. 2). A new 24 Fr chest tube was placed at the end of the procedure.

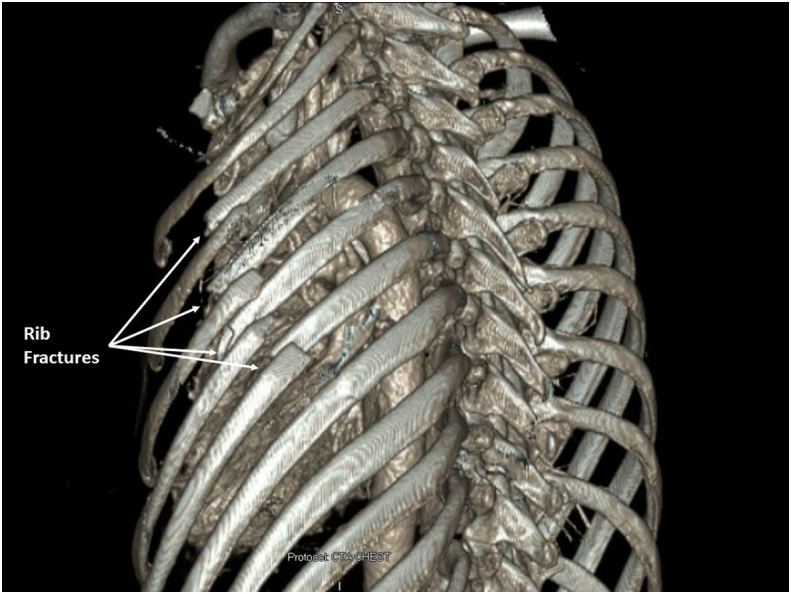

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative video assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) application of the cryoprobe to the left 4th intercostal neurovascular bundle.

The following morning, approximately 9 h after completion of surgery, the patient requested that her PCA be discontinued. Her left chest pain was rated as 0 out of 10, and she had no pain to palpation of the left chest wall. The skin overlying the left chest and inferior breast was insensate to touch. She had no difficulty with pulmonary physiotherapy with incentive spirometry values >50% of predicted and was able to produce a strong cough. She was discharged on post-operative day 4 with a prescription for 20 tablets of 5 mg Oxycodone to be taken every 4 h as needed for pain associated with her other injuries.

She was seen in trauma clinic on post-operative day 11. Her thoracic pain remained a 0 out of 10, and she had no pain to palpation. She continued to be insensate to light touch over the left chest and inferior breast. She received a prescription for a refill of Oxycodone to treat pain associated with her other injuries. At her 6-week follow-up, she continued to deny left chest wall pain on examination. Her cutaneous sensation had partially returned but was still reduced compared to the normal right side. She denied tingling or paresthesia. She was able to have forceful coughs without pain and had returned to many of her previous activities, including yoga. At her 6-month post-operative follow-up, she continued to have no chest wall pain. Her sensation had recovered to approximately 40% compared to the right, and she continued to have no tingling or paresthesia.

Discussion

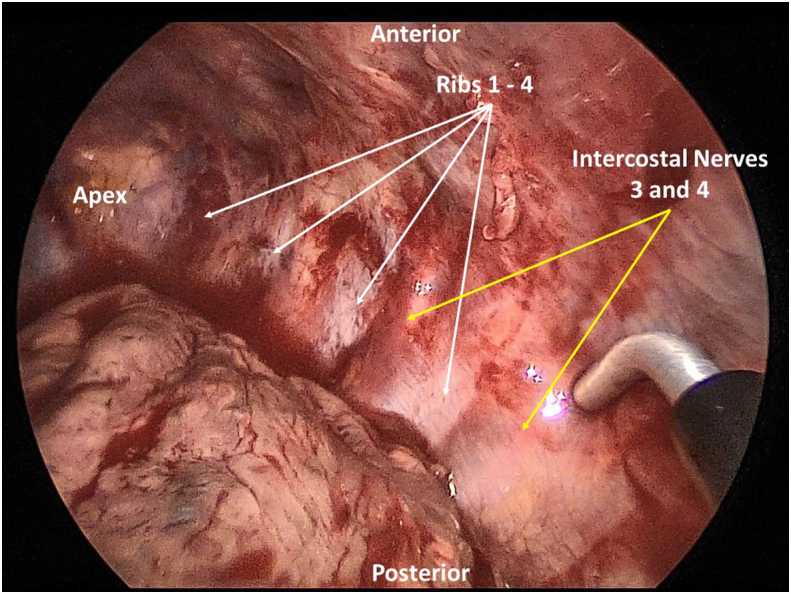

IC for control of post-thoracotomy pain was first described by Nelson et al. in 1974 [3]. Direct application of the cryoprobe to a peripheral nerve results in a Sunderland Stage II nerve injury known as axonotmesis. In this circumstance, the nerve axon and myelin sheath are destroyed but the endoneural, perineural, and epineural structures remain intact (Fig. 3). This is followed by Wallerian degeneration of the distal nerve resulting in numbness distal to the nerve lesion. Regeneration of the nerve occurs along the remaining perineural structures typically between 1 and 3 mm per day [9,10].

Fig. 3.

Anatomic diagram of an intercostal nerve with the axon and surrounding perineural structures of endoneurium, perineurium, and epineurium.

Despite initial enthusiasm, IC was largely abandoned by thoracic surgeons in the mid-1990's because of inconsistent evidence to support its efficacy, wide spread availability of thoracic epidural catheters, and reports of possible long-term neuralgia [[4], [5], [6]]. However, renewed interest for IC has come from the field of pediatric surgery. IC has been shown to provide excellent analgesia along with decreased hospital length of stay and decreased narcotic usage for patients undergoing the Nuss procedure [7,8]. IC appears to be efficacious with an excellent safety profile in these pediatric patients. Given the current opioid crisis and emphasis on minimization of narcotic prescriptions, IC could prove to be an important adjunct for control of traumatic rib fracture pain.

This case highlights several key points regarding traumatic rib fracture pain and IC. First, we found that IC performed concurrently with SSRF resulted in rapid relief of chest wall pain and de-escalation of narcotic medications which was followed by rapid return to normal activities. Trauma patients present a unique population because they experience pain and discomfort immediately after injury, prior to any surgical procedure performed. Each patient experiences their own baseline pain and serves as their own control group regarding the efficacy of analgesia methods. Since the experience of pain and level of pain tolerance are inherently subjective and can vary widely between individuals, the ability to assess and compare the individual trauma patient's pre-operative (conventional analgesia) and post-operative (cryoneurolysis analgesia) pain levels can minimize confounding variables regarding the efficacy of treatment. Second, we also found that IC was safe in that our patient had no long-term adverse outcomes. The patient was continuing to recover sensation by 6 months without dysesthesias or other negative effects. Finally, IC added no significant increase in the number or magnitude of invasive procedures to our patient's care as it was a simple extension of an already indicated procedure. Further investigation, including comparative trials, is necessary and warranted to further establish the role of IC in traumatic rib fracture pain.

Contributor Information

John D. Vossler, Email: jvossler@hawaii.edu.

Frank Z. Zhao, Email: frank.z.zhao@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Flagel B.T. Half-a-dozen ribs: the breakpoint for mortality. Surgery. 2005;138:717–725. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunham C.M., Hileman B.M., Ransom K.J., Malik R.J. Trauma patient adverse outcomes are independently associated with rib cage fracture burden and severity of lung, head, and abdominal injuries. Int. J. Burns Trauma. 2015;5:46–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson K.M. Intraoperative intercostal nerve freezing to prevent postthoracotomy pain. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1974;18:280–285. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)64357-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Cosmo G., Aceto P., Gualtieri E., Congedo E. Analgesia in thoracic surgery: review. Minerva Anestesiol. 2009;75:393–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khanbhai M., Yap K.H., Mohamed S., Dunning J. Is cryoanalgesia effective for post-thoracotomy pain? Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2014;18:202–209. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Detterbeck F.C. Efficacy of methods of intercostal nerve blockade for pain relief after thoracotomy. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2005;80:1550–1559. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graves C., Idowu O., Lee S., Padilla B., Kim S. Intraoperative cryoanalgesia for managing pain after the Nuss procedure. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2017;52:920–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keller, B. A. et al. Intercostal nerve cryoablation versus thoracic epidural catheters for postoperative analgesia following pectus excavatum repair: preliminary outcomes in twenty-six cryoablation patients. J. Pediatr. Surg. 51, 2033–2038 (2016). Evans PJ. Cryoanalgesia. The application of low temperatures to nerves to produce anaesthesia or analgesia. Anaesthesia. 1981;36(11):1003–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Detterbeck F.C. Efficacy of methods of intercostal nerve blockade for pain relief after thoracotomy. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2005;80(4):1550–1559. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans P.J. Cryoanalgesia. The application of low temperatures to nerves to produce anaesthesia or analgesia. Anaesthesia. 1981;36(11):1003–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1981.tb08673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]