Abstract

Endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) plays a key role in the pathogenesis and development of tumors and protects tumor cells from radiation damage and drug‐induced stress. We previously demonstrated that EGFR confers radioresistance in human papillomavirus (HPV)‐negative human oropharyngeal carcinoma by activating ERS signaling through PERK and IRE1α. In addition, PERK confers radioresistance by activating the inflammatory cytokine NF‐κB. However, the effect of IRE1 on radiosensitivity has not yet been fully elucidated. Here, we clarified that IRE1 overexpression was associated with poor outcome in HPV‐negative patients treated with radiotherapy (P = 0.0001). In addition, a significantly higher percentage of radioresistant HPV‐negative patients than radiosensitive HPV‐negative patients exhibited high IRE expression (66.7% vs 27.8%, respectively; P = 0.001). Silencing IRE1 and XBP1 increased DNA double‐strand break (DSB) and radiation‐induced apoptosis, thereby increasing the radiosensitivity of HPV‐negative oropharyngeal carcinoma cells. IRE1‐XBP1 silencing also inhibited radiation‐induced IL‐6 expression at both the RNA and protein levels. The regulatory effect of IRE1‐XBP1 silencing on DNA DSB‐induced and radiation‐induced apoptosis was inhibited by pretreatment with IL‐6. These data indicate that IRE1 regulates radioresistance in HPV‐negative oropharyngeal carcinoma through IL‐6 activation, enhancing X‐ray‐induced DNA DSB and cell apoptosis.

Keywords: interleukin‐6, IRE1, oropharyngeal carcinoma, radiotherapy, XBP1

1. INTRODUCTION

In 2018 alone, 92 887 new cases and 51 005 deaths from oropharyngeal carcinoma occurred worldwide.1 Treatment options for oropharyngeal carcinoma include surgery alone, radiotherapy alone, or various combinations of these modalities with or without chemotherapy or targeted agents. Recurrences occur in up to 66.6% of patients.2 Currently, definitive radiotherapy with concurrent chemotherapy is the standard nonsurgical approach for the management of locally advanced oropharyngeal cancer.

A common etiological agent of head and neck cancer is human papillomavirus (HPV), which is most commonly associated with oropharyngeal carcinoma. Recent data indicate that 57‐72% of patients in Western countries are infected with HPV,3 whereas only 30% in Asia are HPV‐positive.4 However, HPV‐negative patients have worse overall survival than HPV‐positive patients in advanced stages.5 As suggested by clinical data, HPV‐negative cancers clearly respond less robustly to radiotherapy, and further exploration of the specific molecular determinants of radioresistance in HPV‐negative tumors is warranted. Therefore, in subsequent experiments, we selected HPV‐negative cell lines as our experimental system.

Accumulating evidence indicates that endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) plays a key role in the pathogenesis and development of tumors and protects tumor cells from radiation damage and drug‐induced stress. ER homeostasis is abrogated by stimuli such as radiation, drugs and inflammatory responses, leading to radioresistance. ER stress activates the unfolded protein response (UPR) to regulate cell homeostasis. The UPR comprises 3 ER transmembrane receptors: double‐stranded RNA‐activated protein kinase‐like ER kinase (PERK), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) and inositol‐requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1), which are involved in XBP1 mRNA splicing. Activated IRE1 splices a 26 nucleotide intron from ubiquitously expressed XBP1u mRNA. Removal of this intron causes a frame shift in the XBP1 coding region, resulting in the translation of the XBP‐1s isoform rather than the XBP‐1u isoform. Moreover, the XBP1u/XBP1s ratio alternatively adapts the folding capacity of the ER to the appropriate requirements.6 The transcription factor XBP‐1s translocates into the nucleus and induces the expression of chaperones that increase protein folding and participate in mRNA degradation.7 We previously demonstrated that EGFR confers radioresistance in HPV‐negative human oropharyngeal carcinoma by activating ERS signaling through the double‐stranded RNA‐activated protein kinase‐like ER kinase (PERK) and inositol‐requiring enzyme 1 alpha (IRE1α). Our further research found that PERK confers radioresistance by activating the inflammatory cytokine, nuclear factor‐κB (NF‐κB).8, 9 Madhuri C et al showed that IRE1 could induce autophagy in murine macrophage cells under irradiation.10 However, the downstream effectors of the IRE1 pathway and the resulting effects on radiosensitivity have not yet been fully elucidated.

Interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) is a cytokine that regulates inflammatory responses and inhibits apoptosis during inflammation.11 In addition, IL‐6 plays a role in immune escape and tumor progression.12 The biological effects of IL‐6 activate signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), which has been indicated to be a crucial player in the interaction between tumor cells and tumor‐associated macrophages (TAM) and is, thus, related to chemoresistance and radioresistance.13, 14 Recently, ERS signaling‐mediated PERK‐eIF2α activation was reported to be related to IL‐6 expression by dendritic cells in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell lines, ovarian cancer cells and prostate cancer cells.15 In addition, Lee et al showed that the mechanism underlying UV irradiation‐induced skin damage was associated with XBP1‐induced IL‐6 upregulation.16

Based on findings from previous studies, we hypothesized that IRE1‐XBP1 activates IL‐6 to regulate radioresistance. To explore this hypothesis in radioresistant HPV‐negative tumors, we first analyzed the effect of IRE1 on radiosensitivity in HPV‐negative oropharyngeal carcinoma patients treated with radiotherapy. Then, to explore the downstream effects of the IRE1 pathway on radiosensitivity in HPV‐negative oropharyngeal carcinoma cells, we analyzed the effect of IRE1 and IL‐6 on radiosensitivity in the Detroit562 and Fadu cell lines. Furthermore, XBP1 and IRE1 were silenced using siRNA transfection, and IL‐6 antibodies were applied to analyze the regulation of radioresistance by IRE1‐XBP1 through the IL‐6 signaling pathway in oropharyngeal carcinoma cells. In addition, the underlying mechanisms were investigated to identify new therapeutic targets to increase the efficacy of radiotherapy for HPV‐negative oropharyngeal carcinoma with radioresistance.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. The Cancer Genome Atlas database

The expression profiles of IL‐6, IRE1 (ERN1) and XBP1, as well as clinical information associated with the head and neck cancer samples, were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database and downloaded from the UCSC Xena website (http://xena.ucsc.edu/). The RNAseq data were log2(x + 1) transformed. A total of 517 primary tumor samples were included in this study. The total population consisted of 289 patients (55.9%) who received radiotherapy, 158 patients (30.6%) without radiotherapy and 70 patients (13.5%) with unknown treatment.

2.2. Patients and specimens

Pathological tumor sections were obtained from 80 patients with HPV‐negative oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) who accepted radical radiotherapy with or without concurrent chemotherapy at the First Hospital of China Medical University between 2005 and 2011. All recruited patients provided informed consent for the study. In addition, 36 patients with HPV‐negative oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma who received radical radiotherapy between 2014 and 2016 were selected, including 18 patients with radiosensitive tumors and 18 patients with radioresistant tumors. Patients with radiosensitivity were defined as those with lesions that vanished after 6 weeks of radiotherapy and those without tumor or lymph node recurrence within 2 months after radiotherapy. Patients with radioresistance were defined as those with residual lesions after 6 weeks of radiotherapy or with local or regional lymph node recurrence after 2 months of radiotherapy.8 All recruited patients provided informed consent.

2.3. Immunohistochemistry

The method is described in detail in our previous study.17 The sections were incubated with primary anti–IRE1α antibodies (1:100 dilution; Abcam). Two blinded investigators independently examined all slides. Cytoplasmic staining in tumor cells was considered a positive result. A semiquantitative scoring criterion was used as previously described.18 Tumor samples with a final score of ≤2 were determined to be in the low group, tumor samples with a final score of 3‐4 in the moderate group, and tumor samples with a final score of 5‐6 in the high group.

2.4. Cell culture, transfection and reagents

The human oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma cell lines FaDu and Detroit562 were obtained from the ATCC and cultured in minimum essential medium containing 10% inactivated FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2.

RNA interference was performed with ON‐TargetPlus SMARTpool IRE‐1 (ERN1) and XBP1 siRNA and ON‐TargetPlus Non‐targeting siRNA (Dharmacon, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were transfected with siRNA using DharmaFECT 1 transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol.

The IRE1 inhibitor 4μ8c was purchased from Calbiochem. Tunicamycin was purchased from Abcam. Tocilizumab was purchased from Roche.

2.5. Western blot analysis

Total cellular protein was prepared with Pierce Lysis Buffer (Rockford, IL, USA) and analyzed using the Bradford method. The method applied is described in detail in our previous study.19 Primary antibodies, including antibodies against phospho‐ATM, cleaved caspase3, Rad50, Nbs1, Mre11, cleaved poly(ADP‐ribose) polymerase (PARP), IL‐6 (all 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), IRE1α, phospho‐IRE1α, XBP‐1s and γH2AX (all 1:1000; Abcam), were incubated at 4°C overnight. Anti–mouse or anti–rabbit IgG HRP‐linked secondary antibodies (1:1000 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology), were added and incubated. Target proteins were developed with Target LumiGLO (Cell Signaling Technology) and photographed using a DNR BioImaging System (DNR, Israel).

2.6. RNA preparation and real‐time quantitative PCR

Total RNA extraction was performed with an RNeasy Mini Reagent Kit (Qiagen) according to the protocol. An M‐MLV reverse transcription reagent kit (Invitrogen) was used to perform reverse transcription. Quantitative analyses of the PERK and IRE1 mRNA levels were performed with a TaqMan analysis system (Applied Biosystems).20

The following primers were used for real‐time quantitative PCR: IL‐6 forward primer, 5′‐CGTGGAAATGAGAAAAGAGTTGTG‐3′; IL‐6 reverse primer, 5′‐CCAGTTTGGTAGCATCCATCATTTCT‐3′; β‐actin forward primer, 5′‐TGGCACCCAGCACAATGAA‐3′; and β‐actin reverse primer, 5′‐CTAAGTCATAGTCCGCCTAGAAGCA‐3′.

2.7. Colony survival experiment

The method used to assess colony survival was described in detail in our previous study.8 The dose‐survival curve was drawn using the classic multi‐target single hit model: (SF) = 1 − (1 − e−D/D0) N. Each point on the survival curve represents the mean surviving fraction from at least 3 independent experiments. From the survival curve, the mean lethal dose (D0), the quasi‐threshold dose (Dq), the survival fraction at 2 Gy (SF2) and the sensitivity enhancement ratio (SER) (SER = D0 control group/D0 combination group) were calculated.

2.8. Flow cytometry

Experiments were performed according to the protocol supplied with the Annexin‐Green Apoptosis cell detection reagent kit (Cell Signaling Technology). The percentage of apoptotic cells was assessed using a FACScan flow cytometer (FACSCalibur BD; BD Biosciences). The specific experimental methods have been described previously.20

2.9. Immunofluorescence

For the detection of DNA double‐strand breaks (DSB), a γ‐H2AX assay was performed as previously described.8

2.10. Cell Counting Kit‐8 assay

The method applied was described in detail in our previous study.17 Cell proliferation was analyzed using a Cell Counting Kit‐8 (CCK‐8, Dojindo) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

2.11. ELISA

The level of the cytokine IL‐6 in cell culture supernatants was measured by ELISA according to the relevant protocols (Abcam).

2.12. Statistical analyses

Data from 3 independent experiments are expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using a t test. P‐values < 0.05 indicate statistical significance. SPSS 24 software was used to perform statistical analyses. The log‐rank test and Kaplan‐Meier curves were used for the survival analyses.

3. RESULTS

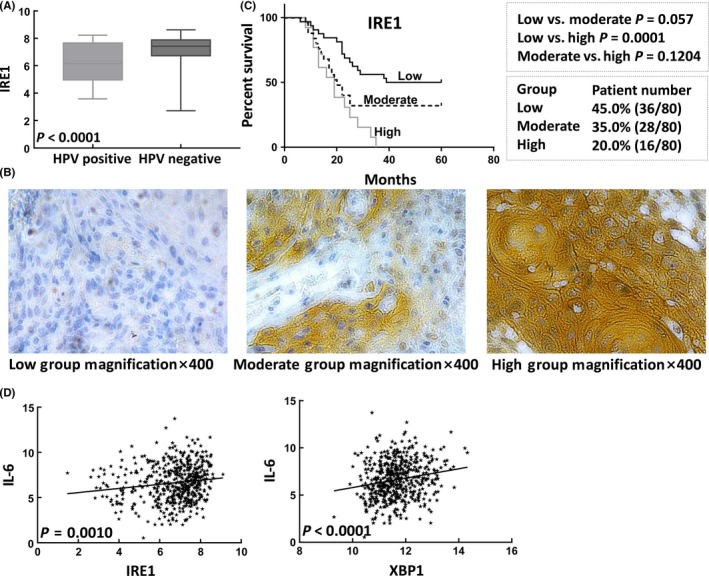

3.1. Expression of IRE‐1 in human HPV‐negative oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma induces radioresistance and is associated with interleukin‐6 expression

As suggested by clinical data, HPV‐negative patients have a worse prognosis than HPV‐positive patients and clearly respond less robustly to radiotherapy. To explore the underlying molecular determinants of radioresistance in HPV‐negative tumors, we examined the mRNA expression levels in HPV‐positive and HPV‐negative tumors. The IRE1 (P < 0.0001) expression levels were significantly elevated in HPV‐negative tumors in the TCGA database (Figure 1A). Our results showed that high expression of IRE1 predicted poor prognosis in patients treated with radiotherapy (P = 0.0001; Figure 1B). To further clarify whether the association between IRE1 and the poor clinical outcomes of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma patients was caused by radioresistance, we collected 36 HPV‐negative patients, divided them into a radioresistant group (50%) and a radiosensitive group (50%) and evaluated the IRE1 expression levels. A total of 66.7% of the patients in the radioresistant group exhibited a high IRE1 expression level, compared with 27.8% in the radiosensitive group. Fisher's exact test results showed that IRE1 overexpression was associated with radioresistance in HPV‐negative patients (P = 0.001; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) expression is associated with endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) activation in patients with oropharyngeal carcinoma treated with radiotherapy. A, Patients with human papillomavirus (HPV)‐negative tumors had significantly higher IRE1 expression levels than those with HPV‐positive tumors. B, Schematic diagram of 3 groups of IRE1 protein expression in the cytoplasm of oropharyngeal carcinoma samples. C, Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that IRE1 was a marker of poor prognosis in patients with oropharyngeal carcinoma treated with radiotherapy. D, IL‐6 expression was significantly associated with the expression of IRE1 and XBP1

Table 1.

Expression of IRE1 in radioresistant and radiosensitive oropharyngeal carcinoma without human papillomavirus infection

| n | Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (0‐2) | Moderate (3‐4) | High (5‐6) | ||

| Radioresistance | 18 | 1 (5.6%) | 5 (27.8) | 12 (66.7%) |

| Radiosensitivity | 18 | 5 (27.8%) | 8 (44.4%) | 5 (27.8%) |

Then we explored whether the mechanism of IRE1‐induced radioresistance was associated with IL‐6 expression and showed that the expression of IL‐6 was associated with the expression of both IRE1 (r = 0.145; r 2 = 0.021; P = 0.001) and XBP1 (r = 0.189; r 2 = 0.036; P < 0.0001) in head and neck tumors (n = 517) in the TCGA database. These results suggest that the IRE1‐XBP1 pathway may induce radioresistance in HPV‐negative tumors by upregulating IL‐6 expression. To further explore the mechanism underlying the association between the IRE1‐XBP1 signaling pathway and the expression of IL‐6, we selected HPV‐negative Detroit562 and Fadu cell lines for subsequent experiments.

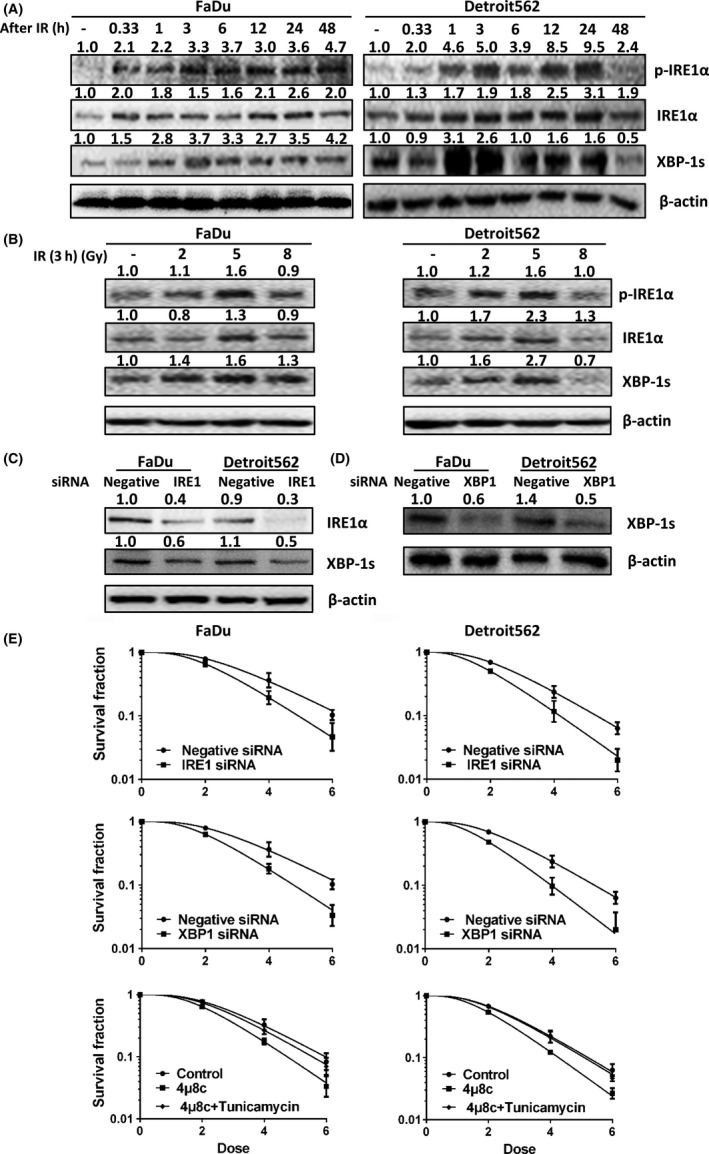

3.2. IRE‐XBP1 activation induces radioresistance in oropharyngeal carcinoma cells

X‐rays induce IRE1α activation in oropharyngeal carcinoma cells in a time‐dependent manner. The levels of phosphorylated IRE1α, total IRE1α protein and XBP‐1s in Detroit562 and Fadu cells increased 20 minutes after irradiation, peaking at 1‐3 hours and beginning to decline at 24‐48 hours. (Figure 2A). Therefore, radiation‐induced activation and sustained overexpression of IRE1‐XBP1 signaling pathway components may be associated with radioresistance. In addition, X‐rays induced IRE1‐XBP1 signaling pathway activation in a dose‐dependent manner, with a peak at 5 Gy (Figure 2B). We therefore selected 5 Gy as the radiation treatment condition in subsequent experiments. In addition, we further silenced IRE1 and XBP1 with antisense siRNA. siRNA treatment significantly inhibited IRE1 and XBP1 protein expression in Detroit562 and Fadu cells (Figure 2C,D). The results of the colony formation assay showed that silencing IRE1 and XBP1 decreased the rate of colony formation by oropharyngeal carcinoma cells after irradiation. Similarly, the effect of 4μ8c, an IRE1 inhibitor, confirmed the decreased rate of colony survival, and tunicamycin, a potent pharmacologic ER stress inducer, reversed this effect (Figure 2E; Tables 2, 3, 4). These results suggest that the inhibition of IRE‐XBP1 pathway activity reverses radioresistance in oropharyngeal carcinoma cells.

Figure 2.

Expression of IRE and XBP1 induces radioresistance in oropharyngeal carcinoma cells. A, Levels of phosphorylated IRE1α, total IRE1α protein and XBP‐1s in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) (FaDu and Detroit562) cells at different time points (20 min and 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h) after exposure to 5 Gy radiation. B, Levels of phosphorylated IRE1α, total IRE1α protein and XBP‐1s in OSCC (FaDu and Detroit562) cells exposed to different radiation doses (2, 5 and 8 Gy) at 12 h after radiation. C, Western blot results showing that transfection of IRE1 siRNA effectively inhibited IRE1α protein and XBP‐1s expression in OSCC (FaDu and Detroit562) cells. D, Western blot results showing that transfection of XBP1 siRNA effectively inhibited XBP‐1s expression in OSCC (FaDu and Detroit562) cells. E, Colony formation assay results showing that silencing of IRE1 and XBP1 and treatment with 4μ8c reduced the colony formation rates after radiotherapy and that tunicamycin reversed this effect. The band densities were quantified with ImageJ software and normalized to those of the loading control, β‐actin

Table 2.

Radiosensitization activity of Fadu and Detroit562 cells silenced IRE1 with antisense siRNA

| Fadu | Detroit562 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neg siRNA | IRE1 siRNA | Neg siRNA | IRE1 siRNA | |

| D0 | 1.70 | 1.33 | 1.46 | 1.21 |

| Dq | 1.99 | 1.73 | 1.77 | 1.40 |

| N | 4.32 | 4.25 | 4.04 | 3.24 |

| SF2 | 0.79 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.50 |

| SER | 1.28 | 1.21 | ||

| SD | ||||

| 2 Gy | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| 4 Gy | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| 6 Gy | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

Abbreviations: D0, mean lethal dose; Dq, quasi‐threshold dose; N, extrapolation number, derived directly from the fitting equation; SER, sensitization enhancement ratio; SF2, survival fraction (2 Gy).

Table 3.

Radiosensitization activity of Fadu and Detroit562 cells silenced XBP1 with antisense siRNA

| Fadu | Detroit562 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neg siRNA | XBP1 siRNA | Neg siRNA | XBP1 siRNA | |

| D0 | 1.70 | 1.31 | 1.46 | 1.13 |

| Dq | 1.99 | 1.67 | 1.77 | 1.38 |

| N | 4.32 | 4.05 | 4.04 | 3.51 |

| SF2 | 0.79 | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.48 |

| SER | 1.30 | 1.29 | ||

| SD | ||||

| 2 Gy | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| 4 Gy | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| 6 Gy | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

Abbreviations: D0, mean lethal dose; Dq, quasi‐threshold dose; N, extrapolation number, derived directly from the fitting equation; SER, sensitization enhancement ratio; SF2, survival fraction (2 Gy).

Table 4.

Radiosensitization activity of Fadu and Detroit562 cells pretreatment with 4μ8c, 4μ8c+Tunicamycin or control

| Fadu | Detroit562 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 4μ8c | 4μ8c+Tuni | Control | 4μ8c | 4μ8c+Tuni | |

| D0 | 1.60 | 2.00 | 1.40 | 1.45 | 1.68 | 1.20 |

| Dq | 1.97 | 2.62 | 1.71 | 1.76 | 1.98 | 1.56 |

| N | 4.50 | 6.87 | 4.15 | 4.00 | 4.31 | 3.98 |

| SF2 | 0.77 | 0.90 | 0.65 | 0.69 | 0.79 | 0.56 |

| SER | 0.80 | 1.19 | 0.86 | 1.21 | ||

| SD | ||||||

| 2 Gy | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| 4 Gy | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| 6 Gy | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: D0, mean lethal dose; Dq, quasi‐threshold dose; N, extrapolation number, derived directly from the fitting equation; SER, sensitization enhancement ratio; SF2, survival fraction (2 Gy).

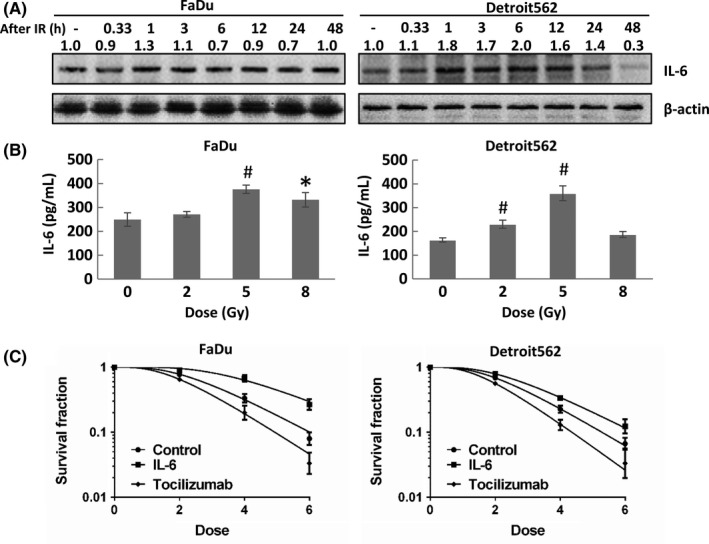

3.3. interleukin‐6 activation induces radioresistance in oropharyngeal carcinoma cells

The analysis of clinical data showed that the IRE1‐XBP1 pathway may induce radioresistance in HPV‐negative tumors by upregulating IL‐6 expression. We further explored the association between IL‐6 and radiosensitivity in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. IL‐6 overexpression was also time‐dependent after irradiation. IL‐6 expression in Detroit562 and Fadu cells increased 1 hour after irradiation, peaked at 1‐3 hours and began to decline at 24‐48 hours (Figure 3A). Consistent with the results for IRE1 expression, X‐rays induced the expression of IL‐6 in cell culture medium with a peak at 5 Gy (Figure 3B). Tocilizumab, a recombinant anti–human IL‐6R monoclonal antibody, reduced the colony formation rates after radiotherapy. In contrast, IL‐6 increased the colony formation rates under radiotherapy, suggesting that IL‐6 confers radioresistance (Figure 3C; Table 5).

Figure 3.

Expression of interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) induces radioresistance in oropharyngeal carcinoma cells. A, IL‐6 expression in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) (FaDu and Detroit562) cells at different time points (20 min and 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h) after exposure to 5 Gy radiation. B, IL‐6 expression in the cell culture medium of OSCC (FaDu and Detroit562) cells exposed to different radiation doses (2, 5 and 8 Gy) at 12 h after radiation. C, Colony formation assay results showing that tocilizumab reduced the colony formation rates after radiotherapy and that IL‐6 reversed this effect. The band densities were quantified with ImageJ software and normalized to those of the loading control, β‐actin

Table 5.

Radiosensitization activity of Fadu and Detroit562 cells pretreatment with IL‐6, tocilizumab or control

| Fadu | Detroit562 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | IL‐6 | Tocilizumab | Control | IL‐6 | Tocilizumab | |

| D0 | 1.60 | 2.00 | 1.40 | 1.45 | 1.68 | 1.20 |

| Dq | 1.97 | 2.62 | 1.71 | 1.76 | 1.98 | 1.56 |

| N | 4.50 | 6.87 | 4.15 | 4.00 | 4.31 | 3.98 |

| SF2 | 0.77 | 0.90 | 0.65 | 0.69 | 0.79 | 0.56 |

| SER | 0.80 | 1.19 | 0.86 | 1.21 | ||

| SD | ||||||

| 2 Gy | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| 4 Gy | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| 6 Gy | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: D0, mean lethal dose; Dq, quasi‐threshold dose; IL‐6, interleukin 6; N, extrapolation number, derived directly from the fitting equation; SER, sensitization enhancement ratio; SF2, survival fraction (2 Gy).

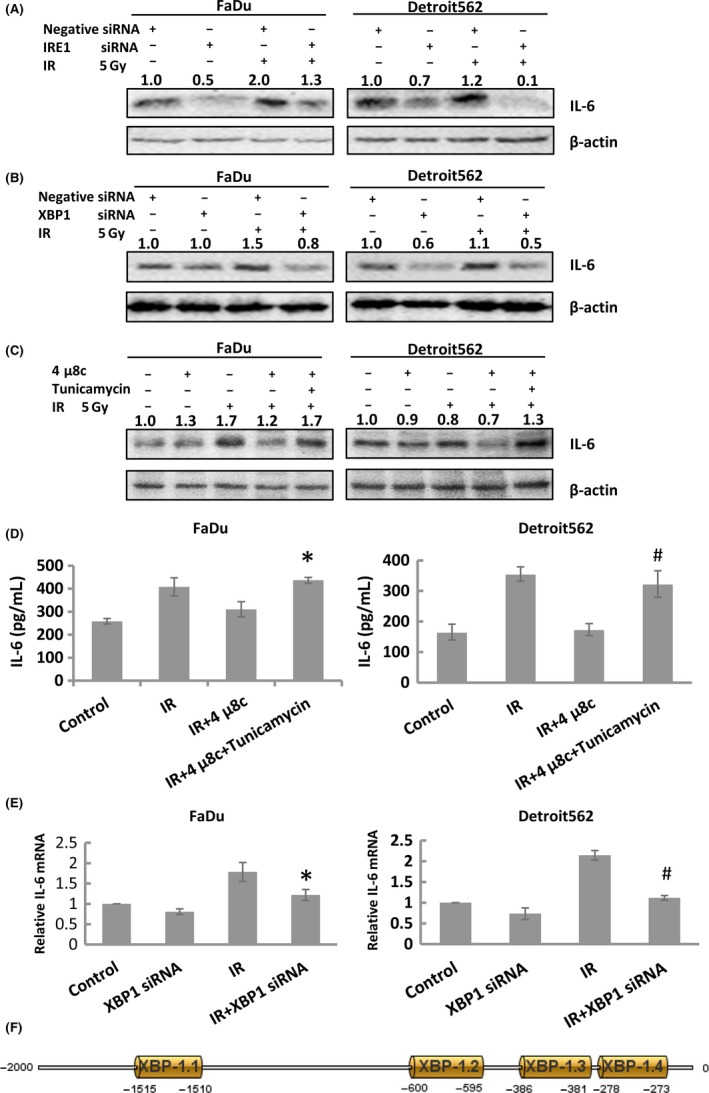

3.4. The IRE1‐XBP1 pathway mediates interleukin‐6 expression to increase radiation‐regulated oropharyngeal carcinoma cell survival

To investigate the mechanism underlying the regulation of radioresistance in oropharyngeal carcinoma cells by the IRE1‐XBP1 pathway and IL‐6, we inhibited IRE1 and XBP1 and examined the IL‐6 level. Inhibition of IRE1 and XBP1 expression decreased the IL‐6 level; this effect was reversed by tunicamycin (Figure 4A,B,C). The release of IL‐6 into the cell culture medium was inhibited by 4μ8c, and this effect was reversed by tunicamycin (Figure 4D). In addition, IL‐6 mRNA expression was inhibited by XBP1 silencing, indicating that XBP‐1s, an isoform of XBP1 spliced by activated IRE1, could act as a transcription factor to regulate IL‐6 mRNA transcription (Figure 4E). To explain this regulatory pattern, we predicted XBP‐1s binding sites in the region defined by the IL‐6 gene to 2000 bp upstream using PROMO. The IL‐6 promoter region contains a total of 4 XBP‐1 binding sites, as shown in Figure 4F.

Figure 4.

The IRE1‐XBP1 pathway regulates radioresistance in oropharyngeal carcinoma cells by activating interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) expression. A, Western blot results showing that transfection of IRE1 siRNA effectively inhibited IL‐6 expression in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) (FaDu and Detroit562) cells. B, Western blot results showing that transfection of XBP1 siRNA effectively inhibited IL‐6 expression in OSCC (FaDu and Detroit562) cells. C, Western blot results showing that 4μ8c effectively inhibited radiation‐induced IL‐6 expression in OSCC (FaDu and Detroit562) cells and that tunicamycin reversed this effect. D, Radiation‐induced IL‐6 expression in the cell culture medium was effectively inhibited by 4μ8c in OSCC (FaDu and Detroit562) cells, and tunicamycin reversed this effect. E, Radiation‐induced IL‐6 mRNA expression was effectively inhibited by XBP1 siRNA in OSCC (FaDu and Detroit562) cells, and tunicamycin reversed this effect. F, The region 2000 bp proximal to the IL‐6 transcriptional start site contained 4 XBP‐1 binding sites: XBP‐1.1 XBP‐1.2, XBP‐1.3 and XBP‐1.4. The band densities were quantified with ImageJ software and normalized to those of the loading control, β‐actin

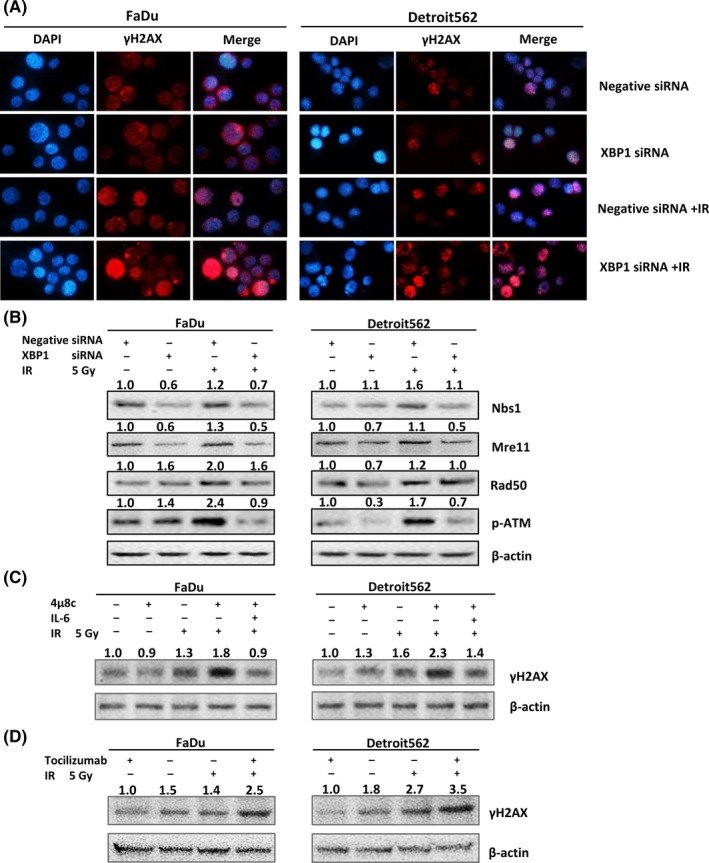

3.5. Inhibition of XBP1‐interleukin‐6 increases radiosensitivity through the activation of DNA double‐strand break formation

Our previous results showed that ERS could regulate the phosphorylation of the radiation‐induced DNA DSB‐related protein ATM in oropharyngeal carcinoma.8 We hypothesized that XBP1 inhibition could increase radiosensitivity through the activation of DNA DSB formation. The formation of γ‐H2AX foci is a marker of DNA DSB damage. Our immunofluorescence studies showed that after exposure to 5 Gy radiation for 1 hour, the number of γ‐H2AX foci in the nucleus of oropharyngeal carcinoma cells was increased. In addition, the radiation after XBP1 silencing produced a more evident effect than radiation alone (Figure 5A). Western blotting showed that XBP1 silencing inhibited radiation‐induced expression of the DNA DSB repair‐related proteins NBS1, Rad50 and Mre11, and reduced ATM phosphorylation (Figure 5B). To further confirm that the DNA DSB damage was regulated by IRE1‐XBP1 pathway‐mediated IL‐6 expression, we inhibited IRE1 with 4μ8c and pretreated cells with IL‐6. The western blot results showed that 4μ8c increased radiation (5 Gy, 12 hours)‐induced γ‐H2AX protein expression. Moreover, the above effects were inhibited by pretreatment with IL‐6 (Figure 5C). Radiation (5 Gy, 12 hours)‐induced γ‐H2AX protein expression was also inhibited by the IL‐6R antibody tocilizumab (Figure 5D). Considering that DNA DSB repair is one of the major causes of radioresistance, silencing XBP1 could reverse DNA DSB repair‐mediated radioresistance.

Figure 5.

The IRE1‐XBP1 pathway regulates radioresistance in oropharyngeal carcinoma cells by upregulating interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) expression. A, Immunofluorescence experiments showed that after oropharyngeal carcinoma cells were exposed to 5 Gy radiation for 1 h, the number of γ‐H2AX foci in the nucleus increased (the blue background indicates the cell nucleus and the light red dots indicate γ‐H2AX foci). In addition, radiation after XBP1 silencing produced a more evident effect than radiation alone. B, Western blot results showing that XBP1 siRNA effectively inhibited the radiation‐induced expression of NBS1, Rad50 and Mre11 and phosphorylation of ATM in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) (FaDu and Detroit562) cells. C, Western blot results showing that 4μ8c effectively increased γ‐H2AX expression in OSCC (FaDu and Detroit562) cells and that IL‐6 reversed this effect. D, Western blot results showing that tocilizumab effectively increased γ‐H2AX expression in OSCC (FaDu and Detroit562) cells. The band densities were quantified with ImageJ software and normalized to those of the loading control, β‐actin

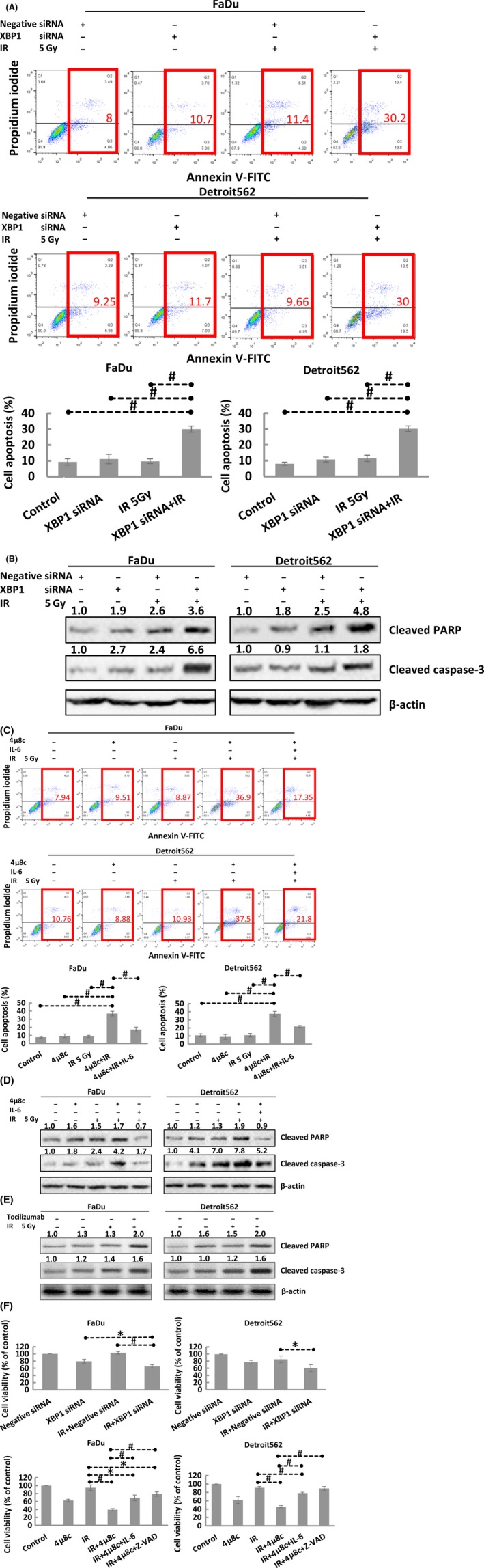

3.6. Silencing XBP1‐interleukin‐6 activates DNA double‐strand break formation, thereby increasing the apoptosis and decreasing the proliferation of oropharyngeal carcinoma cells

Radiotherapy generates secondary electrons, which induce ionization, effectively killing tumor cells by causing DNA damage through reactive oxygen species.21 Hence, the key to increasing radiosensitivity is to increase radiation‐induced cell death. Then we explored whether the IRE1‐XBP1 pathway could regulate radiosensitivity through increasing radiation‐induced apoptosis. The flow cytometry experiments showed that XBP1 silencing increased the radiation‐induced apoptosis index (Figure 6A) and enhanced the radiation‐induced expression of the apoptosis‐related proteins cleaved caspase‐3 and cleaved PARP (Figure 6B). We further applied 4μ8c to inhibit IRE1 and found that 4μ8c increased the radiation‐induced apoptosis index and the radiation‐induced expression of apoptosis‐related proteins, which was inhibited by IL‐6 (Figure 6C,D). In addition, IL‐6 inhibition increased the radiation‐induced expression of the apoptosis‐related proteins cleaved caspase‐3 and cleaved PARP (Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

A, Flow cytometric analysis showing that XBP1 silencing effectively increased the radiation‐induced cell apoptotic index in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) (FaDu and Detroit562) cells. B, Western blot results showing that transfection of XBP1 siRNA effectively increased cleaved caspase‐3 and cleaved poly(ADP‐ribose) polymerase (PARP) expression in OSCC (FaDu and Detroit562) cells. C, Flow cytometric analysis showing that 4μ8c effectively increased the radiation‐induced cell apoptotic index in OSCC (FaDu and Detroit562) cells and that interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) reversed this effect. D, Western blot results showing that 4μ8c effectively increased cleaved caspase‐3 and cleaved PARP expression in OSCC (FaDu and Detroit562) cells and that IL‐6 reversed this effect. E, Western blot results showing that tocilizumab effectively increased cleaved caspase‐3 and cleaved PARP expression in OSCC (FaDu and Detroit562) cells. F, CCK‐8 cell proliferation assay results showing that transfection of XBP1 siRNA and treatment with 4μ8c effectively reduced cell proliferation and that IL‐6 reversed this effect. The band densities were quantified with ImageJ software and normalized to those of the loading control, β‐actin

Then, we further analyzed the influence on proliferation and found that inhibition of XBP1 and IRE1 suppressed radiation‐induced cell proliferation, an effect that was reversed by IL‐6 activation and apoptosis inhibition (via Z‐VAD) (Figure 6F). The above results suggest that targeting the XBP1‐IL‐6 axis can increase the radiosensitivity of oropharyngeal carcinoma by inducing apoptosis and inhibiting cell proliferation.

4. DISCUSSION

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is an important etiological agent of oropharyngeal carcinoma. As suggested by clinical trials, HPV‐negative patients respond less robustly to radiotherapy than HPV‐positive patients.22 To further explore the specific molecular determinants of radioresistance in HPV‐negative tumors, we identified differences in gene expression between HPV‐positive and HPV‐negative tumors. IRE1 expression was significantly elevated in HPV‐negative tumors. IRE1 was reported to be a potential factor in predicting unfavorable prognosis in some cancers.23, 24, 25 However, the effect of IRE1 on prognosis in human oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma has not yet been reported. Consistent with the results of previous studies, our results showed that IRE1 predicted poor prognosis. In addition, we are the first to recognize that IRE1 predicts radioresistance.

Radiation exposure damages biomacromolecules through the generation of oxidative stress.21 In turn, oxidative stress may lead to various intracellular imbalances, including DNA DSB, compromised mitochondrial function and ERS. Accumulating evidence indicates that ERS plays an important role in the development of malignant tumors. Our results showed that X‐rays induce IRE1α and XBP1s activation in oropharyngeal carcinoma cells in a time‐dependent and dose‐dependent manner. Interestingly, X‐ray‐induced IRE1α and XBP1s activation peaked at 5 Gy but decreased at 8 Gy. Similar results were reported in other studies, which showed that high‐dose radiation facilitated cell death and failed to activate the ERS.26, 27 IL‐6 activates STAT3, which has been indicated to be a crucial player in mediating chemoresistance and radioresistance.13, 14 Indeed, Matsuoka Y et al suggested that when oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is exposed to X‐ray irradiation, the increased level of IL‐6 promotes Nrf2 activation.28 The STAT3 pathway is concurrently activated. Activated Nrf2 and STAT3 then translocate into the nucleus and induce the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as Mn‐SOD, thus helping to enhance radioresistance. Consistent with these conclusions, our results showed that X‐ray‐induced IL‐6 expression in the cell culture medium peaked at 5 Gy and conferred radioresistance.

Studies have shown that ERS leads to IL‐6 overexpression. In addition, ATF6 was reported to increase IL‐6 expression.29, 30, 31, 32 After the accumulation of unfolded proteins, PERK autophosphorylation induces eIF2a phosphorylation and increases IL‐6 expression.15, 29, 32 In addition, a study suggested that the mechanism underlying UV irradiation‐induced skin damage was associated with activated XBP1 and UVB‐induced IL‐6 upregulation.16 Through investigating the mechanism underlying the regulation of the IRE1‐XBP1 pathway and IL‐6, we found that silencing IRE1‐XBP1 inhibited radiation‐induced IL‐6 expression at both the RNA and protein levels. Then, we predicted XBP1s binding sites and found that the IL‐6 promoter region contains 4 XBP‐1 binding sites. These results indicate that XBP1 can regulate IL‐6 mRNA transcription.

After tumor cells are exposed to irradiation, a series of stress response processes are activated to induce a DNA repair response in order to maintain cell homeostasis and inhibit apoptosis. To increase radiosensitivity, a reduction in the DNA repair ability is crucial.33 The Mre11‐Rad50‐Nbs1 complex plays an important role in the DNA repair pathway and participates in DNA replication, telomere stability and cell cycle checkpoint pathways.34, 35 ATM senses X‐ray‐induced DNA damage and phosphorylation to activate the cell stress response and induce DNA repair or apoptosis.36 We previously demonstrated that eIF2a silencing confers radiosensitivity through the inhibition of DNA DSB repair and the induction of apoptosis.8 In addition, we recently showed that EGFR silencing promotes apoptosis and confers radiosensitivity through the inhibition of DNA DSB repair.9 The results of our present study were similar to those of previous studies. Inhibition of the XBP1 and IL‐6 pathways increased radiosensitivity through the activation of DNA DSB formation and caused cell apoptosis in oropharyngeal carcinoma cells after radiotherapy. Moreover, our results confirmed that this effect was mediated via the regulation of the DNA DSB repair proteins NBS1, Rad50, Mre11 and phosphorylated ATM. Inhibition of XBP1‐mediated IL‐6 expression induced cell apoptosis to increase radiosensitivity.

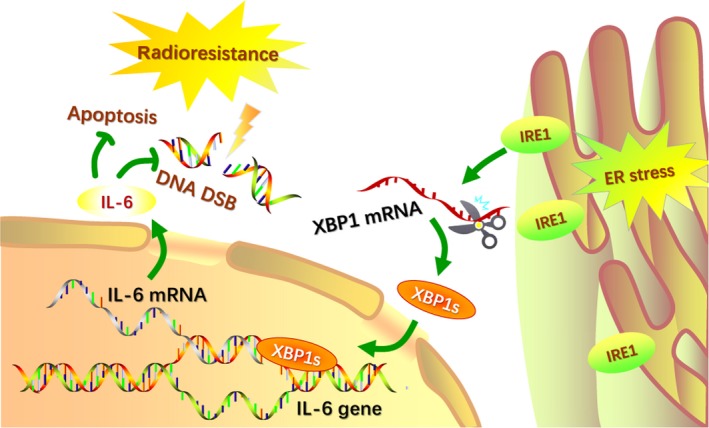

In this study, we first observed the poor prognostic impact of IRE1 overexpression and the favorable effects of IRE1 silencing on radioresistance in HPV‐negative oropharyngeal carcinoma. Then, we evaluated the positive correlation between the expression levels of IRE1, XBP1 and IL‐6. We further observed that at the cellular level, IRE1, XBP1 and IL‐6 showed abnormal, persistent overexpression after radiotherapy, suggesting that overexpression of IRE1, XBP1 and IL‐6 is associated with tumor radioresistance. To test this hypothesis, we transfected siRNA to silence IRE1 and XBP1 and used 4μ8c, an IRE1 inhibitor, and a colony formation assay to confirm that inhibition of IRE1 and XBP1 increased the radiosensitivity of cells. In addition, IL‐6 silencing and treatment with tocilizumab, an anti–IL‐6R monoclonal antibody, increased the radiosensitivity of oropharyngeal carcinoma cells. Then, we proved that IL‐6 could be regulated by the IRE1‐XBP1 pathway and predicted the binding sites of XBP1 in the IL‐6 gene promoter region. The mechanism of increased radiosensitivity is related to the inhibition of radiation‐induced IL‐6 protein expression and the related IRE1‐XBP1 pathway activation, which inhibit radiation‐induced DNA DSB repair and enhance apoptosis (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Schematic model of IRE1‐XBP1‐induced radioresistance via interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) upregulation. Exposure to X‐ray irradiation causes endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS), and increased levels of IRE1 promote the splicing of XBP1 mRNA. The activated transcription factor XBP1s translocates to the nucleus and induces the expression of IL‐6. Concurrently, the formation of DNA double‐strand breaks (DSB) is inhibited and helps decrease apoptosis, which is related to radioresistance

Based on these results, we suggest that IRE1 regulates radioresistance in HPV‐negative oropharyngeal carcinoma through IL‐6 activation, enhancing X‐ray‐induced DNA DSB damage and cell apoptosis.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Lyu X, Zhang M, Li G, Cai Y, Li G, Qiao Q. Interleukin‐6 production mediated by the IRE1‐XBP1 pathway confers radioresistance in human papillomavirus‐negative oropharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2019;110:2471–2484. 10.1111/cas.14094

Funding information

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81402521) and CSCO‐MERCK SERONO Oncology Research Foundation (Y‐MT2016‐004).

Lyu and Zhang contributed to the work equally and should be regarded as co‐first authors.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394‐424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. D'Cruz AK, Vaish R, Dhar H. Oral cancers: current status. Oral Oncol. 2018;87:64‐69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chung CH, Zhang Q, Kong CS, et al. p16 protein expression and human papillomavirus status as prognostic biomarkers of nonoropharyngeal head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3930‐3938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huang H, Zhang B, Chen W, Zou SM, Xu ZG. Relationship between HPV‐DNA status and p16 protein expression in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma and their clinical significance. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2013;35:684‐688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lai K, Killingsworth M, Matthews S, et al. Differences in survival outcome between oropharyngeal and oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma in relation to HPV status. J Oral Pathol Med. 2017;46:574‐582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kober L, Zehe C, Bode J. Development of a novel ER stress based selection system for the isolation of highly productive clones. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109:2599‐2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081‐1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Qiao Q, Sun C, Han C, Han N, Zhang M, Li G. Endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway PERK‐eIF2alpha confers radioresistance in oropharyngeal carcinoma by activating NF‐kappaB. Cancer Sci. 2017;108:1421‐1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang M, Han N, Jiang Y, et al. EGFR confers radioresistance in human oropharyngeal carcinoma by activating endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling PERK‐eIF2alpha‐GRP94 and IRE1alpha‐XBP1‐GRP78. Cancer Med. 2018;7:6234‐6246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chaurasia M, Gupta S, Das A, Dwarakanath BS, Simonsen A, Sharma K. Radiation induces EIF2AK3/PERK and ERN1/IRE1 mediated pro–survival autophagy. Autophagy. 2019;1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hodge DR, Hurt EM, Farrar WL. The role of IL‐6 and STAT3 in inflammation and cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1990;2005:2502‐2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Multhoff G, Radons J. Radiation, inflammation, and immune responses in cancer. Front Oncol. 2012;2:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yu H, Kortylewski M, Pardoll D. Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: role of STAT3 in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:41‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Komohara Y, Jinushi M, Takeya M. Clinical significance of macrophage heterogeneity in human malignant tumors. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fucikova J, Moserova I, Truxova I, et al. High hydrostatic pressure induces immunogenic cell death in human tumor cells. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:1165‐1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee SE, Takagi Y, Nishizaka T, Baek JH, Kim HJ, Lee SH. Subclinical cutaneous inflammation remained after permeability barrier disruption enhances UV sensitivity by altering ER stress responses and topical pseudoceramide prevents them. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309:541‐550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jiang Y, Han Y, Sun C, et al. Rab23 is overexpressed in human bladder cancer and promotes cancer cell proliferation and invasion. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:8131‐8138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hara A, Okayasu I. Cyclooxygenase‐2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in human astrocytic gliomas: correlation with angiogenesis and prognostic significance. Acta Neuropathol. 2004;108:43‐48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Qiao Q, Nozaki Y, Sakoe K, Komatsu N, Kirito K. NF‐kappaB mediates aberrant activation of HIF‐1 in malignant lymphoma. Exp Hematol. 2010;38:1199‐1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Qiao Q, Jiang Y, Li G. Curcumin improves the antitumor effect of X‐ray irradiation by blocking the NF‐kappaB pathway: an in‐vitro study of lymphoma. Anticancer Drugs. 2012;23:597‐605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhou S, Ye W, Shao Q, Zhang M, Liang J. Nrf2 is a potential therapeutic target in radioresistance in human cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88:706‐715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tuttle S, Hertan L, Daurio N, et al. The chemopreventive and clinically used agent curcumin sensitizes HPV (‐) but not HPV (+) HNSCC to ionizing radiation, in vitro and in a mouse orthotopic model. Cancer Biol Ther. 2012;13:575‐584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu J, Xiao M, Li J, et al. Activation of UPR signaling pathway is associated with the malignant progression and poor prognosis in prostate cancer. Prostate. 2017;77:274‐281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen L, Li Q, She T, et al. IRE1alpha‐XBP1 signaling pathway, a potential therapeutic target in multiple myeloma. Leuk Res. 2016;49:7‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Penaranda Fajardo NM, Meijer C, Kruyt FA. The endoplasmic reticulum stress/unfolded protein response in gliomagenesis, tumor progression and as a therapeutic target in glioblastoma. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;118:1‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zong Y, Feng S, Cheng J, Yu C, Lu G. Up‐regulated ATF4 expression increases cell sensitivity to apoptosis in response to radiation. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;41:784‐794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang ZC, Wang JF, Li YB, et al. Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress in apoptosis of testicular cells induced by low‐dose radiation. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci 2013;33:551‐558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Matsuoka Y, Nakayama H, Yoshida R, et al. IL‐6 controls resistance to radiation by suppressing oxidative stress via the Nrf2‐antioxidant pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:1234‐1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mijosek V, Lasitschka F, Warth A, Zabeck H, Dalpke AH, Weitnauer M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress is a danger signal promoting innate inflammatory responses in bronchial epithelial cells. J Innate Immun. 2016;8:464‐478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Druelle C, Drullion C, Desle J, et al. ATF6alpha regulates morphological changes associated with senescence in human fibroblasts. Oncotarget. 2016;7:67699‐67715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Banuls C, Rovira‐Llopis S, Martinez de Maranon A, et al. Metabolic syndrome enhances endoplasmic reticulum, oxidative stress and leukocyte‐endothelium interactions in PCOS. Metabolism. 2017;71:153‐162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Xu J, Xiong M, Huang B, Chen H. Advanced glycation end products upregulate the endoplasmic reticulum stress in human periodontal ligament cells. J Periodontol. 2015;86:440‐447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chavaudra N, Bourhis J, Foray N. Quantified relationship between cellular radiosensitivity, DNA repair defects and chromatin relaxation: a study of 19 human tumour cell lines from different origin. Radiother Oncol. 2004;73:373‐382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lamarche BJ, Orazio NI, Weitzman MD. The MRN complex in double‐strand break repair and telomere maintenance. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:3682‐3695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Williams GJ, Lees‐Miller SP, Tainer JA. Mre11‐Rad50‐Nbs1 conformations and the control of sensing, signaling, and effector responses at DNA double‐strand breaks. DNA Repair. 2010;9:1299‐1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rhee JG, Li D, Suntharalingam M, Guo C, O'Malley BW Jr, Carney JP. Radiosensitization of head/neck squamous cell carcinoma by adenovirus‐mediated expression of the Nbs1 protein. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:273‐278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]