Abstract

Metastatic retroperitoneal tumors constitute an end-stage disease with poor prognosis that represents a heavy global health burden. The present study aimed to explore the efficacy of irreversible electroporation ablation (IRE) therapy in patients with end-stage retroperitoneal tumors. Between April 2016 and September 2017, three patients with unresectable retroperitoneal malignant tumors were enrolled. Among these cases, ultrasound (US)-guided IRE was palliatively performed for targeting 3 tumors (1 tumor per patient) located around the abdominal aorta. Post-treatment contrast-enhanced US (CEUS) and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) scans were subsequently performed to evaluate the area adjacent to the ablation zone and determine the prognosis. During the follow-up, the cases experienced a reduction of pain (mean score of 5.8 decreased to 2.2, based on the visual analogue scale), and had an overall survival rate ranging from 2 to 11 months. Case 1 remained alive at the time of submission of this study, but case 2 died within 2 months and case 3 within 11 months due to liver metastases of the primary tumor. At the 3-week follow-up, the CEUS image for case 1 exhibited a contrast defect with a sufficient ablation margin, in accordance with the CECT at 1.5 months following IRE, exhibiting complete tumor necrosis without contrast enhancement. Overall, these results suggest that US-guided percutaneous IRE may be effective in the treatment of end-stage retroperitoneal tumors. However, further studies are required to substantiate the conclusions of the present study. The present clinical trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (ID: NCT02822066) on June 20th, 2016.

Keywords: irreversible electroporation, retroperitoneal tumor, survival, prognosis, contrast-enhanced ultrasonography, ultrasonography

Introduction

Retroperitoneal sarcoma is a lethal disease with a generally poor prognosis, and retroperitoneal tumors are usually secondary metastatic tumors from other organs. Numerous patients are able to feel an abdominal mass or distension at the end-stage of the disease. Traditional treatment strategies for locally advanced retroperitoneal tumors include surgical resection (1,2), radiation therapy (3,4) and chemotherapy (5,6). The deep site of the retroperitoneum is surrounded by gastrointestinal and urologic organs and large blood vessels, which increases the difficulty of open surgery. Irreversible electroporation (IRE) is a non-thermal ablative technique, which destroys the lipid-bilayer structure of the cell membrane to generate tiny nanopores using a series of high-voltage, low-energy-current electrical pulses, resulting in apoptosis of the target cells. Previous studies have reported on the progressive use of IRE for the treatment of solid organs, including the pancreas (7), liver (8), lung (9), kidney (10) and prostate (11), and it is particularly suitable for tumors located in large vessels, the hilar region, bile duct and ureter (12). We ever reported the novel use of IRE for the percutaneous local ablation of portal vein tumor thrombus (PVTT) without heat-sink effect and thermal injury to surrounding portal vein (PV) branches (13). However, this technique is not generally suitable for patients with cardiopulmonary dysfunction, arrhythmia or cardiac pacemaker.

The present study reports on 3 cases with metastatic retroperitoneal tumors with the primary tumor originating from other organs, who received IRE palliative therapy using 3–4 electrodes according to the tumor size, and on their short-term follow-up.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

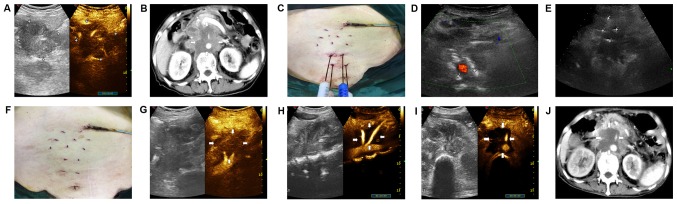

Between April 2016 and September 2017, a total of 3 patients (2 female and 1 male) who had 3 locally advanced retroperitoneal tumors received percutaneous IRE therapy. The baseline characteristics of the patients included are provided in Table I. The patients (case 1, female; case 2, female; case 3, male) were 60, 43 and 59 years old, respectively, and all had metastatic retroperitoneal tumors (case 1, ovarian cancer; case 2, gastric cancer; and case 3, pancreatic cancer), as well as a history of surgical resection or chemotherapy. On admission, the patients had complaints of waist pain for several months. The pain intensity was estimated using a visual analog scale (VAS) from 0 to 10 (where 0 represented no pain and 10 represented the worst pain imaginable) (14). Pre-operative computed tomography (CT) or contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) revealed that the tumors were between 2.0 and 6.1 cm in size. Pre-operative CEUS was generated using ultrasound machines with contrast-specific software (MyLab 70 XVG and MyLab Twice; Esaote) in case 1 revealed the course of contrast agent wash-in and wash-out as time elapsed (Fig. 1A), and pre-operative CT indicated metastatic lymph nodes of 6.1×4.3 cm in size encircling the abdominal aorta (Fig. 1B). Of note, all these metastatic tumors were situated deeply and close to important vessels, posing a risk of massive hemorrhage. The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: i) All patients had their cancer pathologically confirmed; ii) patients were intolerant to chemotherapy and were reluctant to undergo further surgery due to the high risk associated with it; iii) measurements of the following cancer-associated blood parameters were applicable: Hemoglobin level, ≥8.0 g/dl (male normal range, 12.0–16.5 g/dl; female normal range, 11.0–15.0 g/dl); platelet count, ≥50×109/l (normal range, 100–300×109/l) and international normalized ratio >1.5 (normal range, 0.8–1.2); and iv) the patients were void of severe coronary disease, acute or chronic infection or autoimmune diseases. This prospective study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University (Zhejiang, China). All of the patients and their relatives were informed about the procedures and provided their written informed consent.

Table I.

Characteristics of patients with metastatic retroperitoneal tumors.

| Case no. | Sex | Age (years) | Primary cancer | History | Location of tumor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 60 | Ovarian cancer | Oophorectomy and chemotherapy | Adjacent to abdominal aorta |

| 2 | Female | 43 | Gastric cancer | Gastrectomy | Adjacent to abdominal aorta |

| 3 | Male | 59 | Pancreatic cancer | Whipple operation | Adjacent to abdominal aorta |

Figure 1.

A 60-year-old female patient with metastatic retroperitoneal tumors was treated with IRE. (A) Pre-operative CEUS, revealing irregular arterial hyper vascularization of 6.36×6.30 cm. (B) Pre-operative CT scan revealing a tumor of 6.1×4.3 cm in size encircling the abdominal aorta. (C) The patient was placed in the supine position and US-guided electrodes were inserted parallel. (D) Grayscale sagittal US image of the retroperitoneum generated using color-flow Doppler imaging, demonstrating that the two electrodes parallelly encircled the tumor mass surrounding the abdominal aorta. (E) US-guided percutaneous IRE ablation, revealing four needles parallelly puncturing the targeted tissue. The distance between these needles was 1.85–2.13 cm. (F) Image of the post-operative abdomen revealing the needle tract. (G) Immediate post-operative image indicating the tumors with slight enhancement on CEUS. (H) CEUS 20 days after IRE revealing regular arterial hyper vascularization adjacent to the hypoechoic area, corresponding to the immediate post-operative image. (I) CEUS at 3 weeks following IRE treatment, indicating a clearly demarcated dark area without perfused tissue. (J) 6 weeks following IRE, the portal-phase axial CT image revealed tumor complete necrosis of 5.4×5.2 cm in size (vs. an initial size of 6.1×4.3×4.3 cm3), without contrast enhancement around the abdominal aorta. CE, contrast-enhanced; US, ultrasound; CT, computed tomography; IRE, irreversible electroporation.

IRE procedure

The three cases received percutaneous IRE in the supine position under general anesthesia to avoid intense muscle contractions via an electroporation system (NanoKnife® system; AngioDynamics) using 3–4 19-gauge electrodes depending on the tumor size. All of the percutaneous procedures were performed by an interventional radiologist who had at least 10 years' experience in interventional medicine. Under the guidance of ultrasonography using MyLab Twice equipment (Esaote), percutaneous IRE ablation in case 1 was performed using 4 parallel 19-gauge electrodes, where the length of the tip was 0.5 cm and the between-electrode distance was fixed at 1.6–2.1 cm (Fig. 1C). Doppler color-flow imaging was used in real time to guide two needles, parallelly clamping the target mass surrounding the abdominal aorta (Fig. 1D). All of the mentioned intervals that are described were confirmed by US (Fig. 1E), and subsequently imported into the electroporation software in order to select the appropriate voltage and pulse-length delivery. Preliminary 2,700-V test pulses were given to check the tissue conductivity. Subsequently, a total of 90 pulses with a length of 70–90 msec were performed in the voltage range of 2,550–3,000 V under the setting of 1,500 V/cm. The detailed procedures for treating the target lesions are summarized in Table II. Cases 1 and 2 only received one session of IRE therapy, whereas case 3 underwent a second session of therapy at 5 months after the first IRE treatment. Inter-electrode distances in the targeting lesions ranged from 1.5 to 2.0 cm. An electrocardiograph trigger was used to monitor different types of cardiac arrhythmia. After one session of electroporation, immediate CEUS images (via the injection of 2.4 ml SonoVue mixed with 10.0 ml 0.9% sodium chloride solution) were used to examine whether any potential residual lesions existed. In the procedures for case 1, by parallelly adjusting the puncture needle to a position ~1.0 cm away from the previous site of electroporation, the parallel puncture and needle procedures were repeated three times through a total of 12 rounds in order to maximize the curative effect (Fig. 1F). Following percutaneous IRE, follow-up by CEUS, CT scan (GE Healthcare) and measurement of cancer-associated blood parameters [carcinoembryonic antigen, alpha fetoprotein and carbohydrate antigen (CA19-9)] was performed at monthly intervals. In addition, the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) quality of life (QoL) questionnaire (QLQ)-C30 (Version 3.0) is a questionnaire used for health-associated assessment, which includes 5 functional dimensions (Physical, Role, Cognitive, Emotional and Social functioning), 3 symptom dimensions (Fatigue, Pain and Nausea/Vomiting), 1global health status scale and 6 single items (Constipation, Diarrhea, Insomnia, Dyspnea, Appetite Loss and Financial Difficulties) (15). The clinical assessment of QoL in all patients was conducted at the baseline and at every three months following IRE therapy.

Table II.

Procedural specifications for each patient.

| Patient | Ablation area (cm) | Number of needles | Type of needle (gauge) | Voltage (V) | Number of pulses | Mutual distance of needles (cm) | Time of survival the (months) | Complications | Outcome | CEA (ng/ml) (normal range, 0–5 ng/ml) | AFP (ng/ml) (normal range, 0–20 ng/ml) | CA19-9 (U/ml) (normal range, 0–37 ng/ml) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Last follow-up | Pre-IRE | Post-IRE | Pre-IRE | Post-IRE | Pre-IRE | Post-IRE | |||||||||

| 1 | CT:6.1×4.3; CEUS:6.3×4.9 | CT:5.4×5.2 | 4 | 19 | 2,550–3,000 | 80–90 | 1.6; 1.8; 2.0; 2.0 | 5 | Mild pain, minor bleeding | Alive | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 7.1 | 10.8 |

| 2 | CT:2.8×2.0 | CT:2.0×1.5 | 3 | 19 | 2,400–3,000 | 80 | 1.6; 2.0; 1.5 | 2 | Mild pain | Deceased | 64.8 | 2,639.1 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 9.8 | 69.0 |

| 3 | CT:2.8×2.3 | MR:1.8×1.4; | 3 | 19 | 2,800–3,000 | 70–80 | 2.0; 2.0; 2.0 | 11 | Mild pain, minor bleeding | Deceased | 4.3 | 4.8 | 2.4 | 2.2 | >12,000 | 1,374.1 |

G, gauge; CT, computed tomography; MR, magnetic resonance; IRE, irreversible electroporation; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; AFP, alpha fetoprotein; CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9.

Results

IRE procedure characteristics and follow up

The three patients enrolled in the present study underwent palliative IRE therapy for locally advanced retroperitoneal tumors, with a mean follow-up time of 6 months post-IRE. For case 1, CEUS imaging immediately after the surgery revealed regular arterial hyper vascularization adjacent to the hypoechoic area corresponding to the CEUS images at 3 weeks post-IRE (Fig. 1G and H). Furthermore, the 3-week CEUS image exhibited a clear contrast defect with a sufficient ablation margin (Fig. 1I), which was in accordance with the contrast-enhanced CT at 1.5 months after IRE, and revealed that the tumor shrank to 5.4×5.2 cm in size (vs. 6.1×4.3×4.3 cm3 in initial size), without contrast enhancement (Fig. 1J).

At several months following IRE therapy, the cases exhibited improved clinical symptoms (Table III), and their overall survival (OS) ranged from 2 to 11 months. Case 1 was alive at the time of writing. Case 2 and 3 had an OS of 2 and 11 months following IRE, respectively. Regarding the tumor markers following IRE, these were all within the normal range for case 1, although case 2 exhibited an increased carcinoembryonic antigen level, from 64.8 to 2,639.1 ng/ml, and case 3 had CA19-9 levels beyond the upper limit of normal (Table II). During the follow-up, minor procedure-associated pain was immediately detectable for the 3 cases and minor bleeding was instantly reported in case 1 and 3, which did not receive any treatment. Compared with the VAS score recorded on admission to the hospital, the patients exhibited effective pain relief (mean score of 5.8 decreased to 2.2) at the last month of follow-up. Furthermore, when comparing QoL at the baseline, QoL assessment revealed that global health status improved and pain score decreased during the last follow-up (Table III). However, case 2 died within 2 months and case 3 within 11 months due to liver metastases of the primary tumor.

Table III.

Change in quality of life (before IRE-3 months after IRE).

| Difference in quality of life | ||

|---|---|---|

| EORTC Scale | Before IRE-3 months after IRE | Before IRE-last month of follow-up |

| Global health status | −12.6a | −15.2a |

| Functional scales | ||

| Physical functioning | −2.8 | −3.2 |

| Role functioning | −1.3 | 2.6 |

| Emotional functioning | −1.2 | −7.8 |

| Cognitive functioning | 3.1 | 5.2 |

| Social functioning | −7.9 | −6.2 |

| Symptom scales | ||

| Fatigue | 1.3 | 5.2 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 2.3 | 3.8 |

| Pain | 16.2b | 15.6a |

| Dyspnea | −0.8 | −2.9 |

| Insomnia | −4.9 | −3.9 |

| Appetite loss | 2.5 | 4.3 |

| Constipation | 7.3 | 6.1 |

| Diarrhea | 4.9 | 6.8 |

| Financial problems | −3.6 | −3.1 |

P<0.05 vs. the baseline.

Systematic review

In addition, to substantiate the results of the present study, a systematic literature search was performed in the PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Scoups and Cochrane Library databases for studied published until September 21st, 2017, using the following predefined search terms: ‘Irreversible electroporation’, ‘retroperitoneal’ and ‘cancer’. Of 38 relevant studies selected based on the title and abstracts screened, the full-text version of 4 studies was finally reviewed. These studies comprised 1 study based on a porcine model (16) and 3 studies on human patients (17–19). Table IV provides the basic characteristics of the included studies. A total of 12 patients with 12 tumors underwent IRE treatment using 2–3 electrodes (15–17). The mean age of the patients ranged from 45.9 to 74 years. During the 1–2-month follow-up period, minor complications, including anastomotic leak, wound infection and adverse effects including pain were observed.

Table IV.

Summary of IRE therapy of end-stage retroperitoneal tumors reported in the literature.

| Author, year | Study period | Design | Country | Subjects | Population characteristics | Tumor size (cm) | Treatment methods | Number of electrodes | Number of patients | Males/females | Age (years) | Follow-up interval (months) | Complications | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dunki et al 2014 | NA | Retrospective | United States | Porcine | 6 retroperitoneal tissues | NA | US-guided | 4 | 6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | (16) |

| Underhill et al 2016 | December 2013 to April 2015 | Retrospective | United States | Human | 2 sarcoma; 1 carcinoid; 1 giant cell tumor; 1 ovarian; 1 triton tumor; 1 adenocarcinoma | NA | NA | 3 | 7 | 1/6 | 45.9±13.6 | 1 | 1 anastomotic leak; 1 wound infection | (17) |

| Kambakamba et al, 2016 | September 2012 to December 2015 | Prospective | Switzerland | Human | 4 retroperitoneal tumors | NA | US-guided IRE | NA | 4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | (18) |

| Qin et al, 2017 | March 2016 | Retrospective | China | Human | 1 unresectable retroperitoneal malignant fibroussarcoma | 7.3×7.0×7.5 | CT and US-guided IRE | 2 | 1 | 0/1 | 74 | 2 | NA | (19) |

NA, not available; US, ultrasonography; CT, computed tomography; IRE, irreversible electroporation; US, ultrasound.

Discussion

At present, insufficient evidence is available to determine the optimal management of patients with retroperitoneal cancer, and this pathology continues to present a therapeutic challenge due to medical issues and anatomical challenges. Meng et al (20) reported a mean OS of 5.03 months using gemcitabine for the treatment of locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Huachansu, an injectable form of chansu, is a sterilized hot water extract of dried toad skin and when combined with gemcitabine, may not improve the prognosis of patients with locally advanced metastatic pancreatic cancer (20).

IRE was previously performed for PVTT (13). It was determined that end-stage metastatic retroperitoneal malignant tumors were located at risky sites (12,13), including vital structures and large blood vessels. In the present case series, the three patients were palliatively treated using IRE, with favorable results, including a mean OS of >6 months. During the follow-up, minor side effects that did not receive any treatment, including pain and bleeding from needle wounds, were recorded. The patients exhibited an improved prognosis compared with that at baseline, and the post-operative QoL of all three cases was improved in the functional and symptom dimensions, as well as on the global health status scale of the EORTC QLQ-C30. However, two cases succumbed to mortality due to liver metastases from the primary tumor. Over the course of the last few decades, numerous studies have suggested that IRE is effective in prolonging the survival of patients with malignant tumors. In a multicenter prospective trial including 200 patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer treated with IRE, the median OS was 24.9 months and only 6 patients (3%) presented with local recurrence during a median follow-up of 29 months (21). Narayanan et al (22) reported a similar median OS of 27.0 months. This study reported on a case with unresectable retroperitoneal malignant fibrous sarcoma treated with CT-guided IRE using 2 electrodes. The CT scan indicated that a lesion decreased in size from 7.3×7.0×7.5 to 5.1×4.0×5.2 cm, without any obvious enhancement at 2 months post-operatively (19). In a retrospective study, Underhill et al (17) identified that patients undergoing supplemental IRE following surgical resection for retroperitoneal neoplasms had developed few complications. Therefore, IRE has emerged as an important supplementary method to accompany surgical resection for the treatment of retroperitoneal tumors.

The clinical challenge is enhanced if the retroperitoneal tumors have a large size and then usually invade proximal organs. A previous study reported that IRE may induce cellular apoptosis rather than protein denaturation and necrosis, and the tumor cells may be removed via cellular phagocytosis; subsequently, the ablation area was rapidly replaced by normal cells, which was beneficial in terms of functional recovery (23). During these procedures, structures including blood vessels, nervous tissue or bile ducts remain intact. In terms of safety, selection of appropriate probe placement, needle exposure length and pulse length is vital. A preliminary study using a porcine model indicated that probe exposure of ~2.5 cm in the liver and ~1.5 cm in the pancreas with an inter-electrode distance of 1.5–2.3 cm were acceptable (16). The accuracy of the IRE procedure is high due to real-time navigation and monitoring associated with US. Furthermore, in the present study, ablated residual lesions were easily located and rapidly identified by using CEUS. The treatment efficacy of the procedure was not affected by heat-sink effects, since IRE, as a method, is predominantly based on electrical pulse breakdown of the cell membrane (24). During the process, irreversible electroporation does not produce heat, and therefore, it is not affected by additional external temperature. Compared with thermal ablation, there are clear boundaries, which do not cause damage to adjacent normal tissue. In addition, IRE was reported to cause robust immunogenic effects, which led to increased serum interleukin-6 levels higher than those achieved through radiofrequency ablation (25). Therefore, the results of the present study highlighted that IRE may be beneficial for cases of locally advanced metastatic tumors located in proximity to major vessels.

There were certain limitations associated with the present study. First, the study had a small sample size and two of the patients were followed up until death. Furthermore, needle tract seeding is possible, but not controlled, during IRE ablation. In a previously published study, this was demonstrated to occur in 26% of the treated tumors under CT guidance in 29 patients with lesions located adjacent to major portal or hepatic veins, bile duct structures or the intestines (26). Furthermore, in the present study, confounding factors should be considered, and individual heterogeneous factors, including individual histories of therapeutic treatments and lifestyle changes, may have exaggerated the palliative treatment effects determined. Furthermore, long-term adjuvant effects may lead to selection bias (27–29). However, taking all of these limitations into consideration, the results of the present study still suggest that patients undergoing IRE therapy were at a lower risk of complications of massive hemorrhage in at risk regions, compared with those receiving other treatment options, which may provide a novel line of investigation in the future.

In conclusion, the present study preliminarily identified technically effective, percutaneous IRE procedures utilizing US guidance for unresectable metastatic retroperitoneal tumors. During short-term follow-up, this may assist in providing favorable palliative care in terms of improving prognosis. However, additional large-scale pairwise comparisons with control groups and long-term studies are required to substantiate these results regarding IRE therapy.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- IRE

irreversible electroporation

- US

ultrasonography

- CEUS

contrast-enhanced ultrasound

- OS

overall survival

- CT

computed tomography

Funding

The design of the present study, data collection and analysis were supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (grant no. LY16H180004), the National S&T Major Project of China (grant nos. SQ2018ZX100301 and 2018ZX10301201), the Key Research Development Program of Zhejiang province (grant no. 2018C03018), the Key Science and Technology Program of Zhejiang province (grant no. WKJ-ZJ-1923), the Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (grant no. 2012C23094) and the Foundation of Zhejiang Health Committee (grant nos. 2014KYA086 and 2016DTB003).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated during the present study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

Study conception and design: TJ; acquisition of data: TJ, QZ, XB, GT, XC, LW; analysis and interpretation of data: QZ, GT; drafting of the manuscript: TJ, QZ; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: TJ; statistical analysis: GT; obtainment of funding: TJ, QZ, XB, XC, LW; technical or material support: TJ; study supervision: TJ. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This prospective study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University (Zhejiang, China). Informed consent for study participation were obtained.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication of the data and images (CEUS images, CT or MRI images, laboratory findings, age, sex) was obtained from all participating patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Macneill AJ, Miceli R, Strauss DC, Bonvalot S, Hohenberger P, Van Coevorden F, Rutkowski P, Callegaro D, Hayes AJ, Honoré C, et al. Post-relapse outcomes after primary extended resection of retroperitoneal sarcoma: A report from the Trans-Atlantic RPS Working Group. Cancer. 2017;123:1971–1978. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maurice MJ, Yih JM, Ammori JB, Abouassaly R. Predictors of surgical quality for retroperitoneal sarcoma: Volume matters. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:766–774. doi: 10.1002/jso.24710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mak KS, Phillips JG, Barysauskas CM, Lee LK, Mannarino EG, Van Benthuysen L, Raut CP, Mullen JT, Fairweather M, DeLaney TF, Baldini EH. Acute gastrointestinal toxicity and bowel bag dose-volume parameters for preoperative radiation therapy for retroperitoneal sarcoma. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2016;6:360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee HS, Yu JI, Lim DH, Kim SJ. Retroperitoneal liposarcoma: The role of adjuvant radiation therapy and the prognostic factors. Radiat Oncol J. 2016;34:216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.06.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alqasem K, Abukhiran I, Jasser J, Bisharat T, Ellati RT, Khzouz J, Al-Saidi I, Al-Daghamin A. Clinico-pathological outcomes of post-primary and salvage chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for mixed germ cell tumors, King Hussein Cancer Center experience. Turk J Urol. 2016;42:256–260. doi: 10.5152/tud.2016.64188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mano R, Becerra MF, Carver BS, Bosl GJ, Motzer RJ, Bajorin DF, Feldman DR, Sheinfeld J. Clinical outcome of patients with Fibrosis/Necrosis at post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for advanced germ cell tumors. J Urol. 2017;197:391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.09.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stillström D, Nilsson H, Jesse M, Peterhans M, Jonas E, Freedman J. A new technique for minimally invasive irreversible electroporation of tumors in the head and body of the pancreas. Surgical Endosc. 2017;31:1982–1985. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5173-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langan RC, Goldman DA, D'Angelica MI, Dematteo RP, Allen PJ, Balachandran VP, Jarnagin WR, Kingham TP. Recurrence patterns following irreversible electroporation for hepatic malignancies. J Surg Oncol. 2017;115:704–710. doi: 10.1002/jso.24570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song ZQ, Xu XH, Pan ZH, Yao CG, Zhou QH. Mechanisms for steep pulse irreversible electroporation technology to kill human large cell lung cancer cells L9981. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:2386–2394. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin RC, Schwartz E, Adams JA, Farah I, Derhake BM. Intra-operative anesthesia management in patients undergoing surgical irreversible electroporation of the pancreas, Liver, Kidney, and retroperitoneal tumors. Anesth Pain Med. 2015;5:e22786. doi: 10.5812/aapm.22786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheltema MJ, Postema AW, de Bruin DM, Buijs M, Engelbrecht MR, Laguna MP, Wijkstra H, de Reijke TM, de la Rosette JJMCH. Irreversible electroporation for the treatment of localized prostate cancer: A summary of imaging findings and treatment feedback. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2017;23:365–370. doi: 10.5152/dir.2017.16608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kos B, Voigt P, Miklavcic D, Moche M. Careful treatment planning enables safe ablation of liver tumors adjacent to major blood vessels by percutaneous irreversible electroporation (IRE) Radiol Oncol. 2015;49:234–241. doi: 10.1515/raon-2015-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chai W, Tian G, Jiang T. Percutaneous irreversible electroporation for portal vein tumor thrombus: A case report. Ultrasound Q. 2017;33:296–299. doi: 10.1097/RUQ.0000000000000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bijur PE, Silver W, Gallagher EJ. Reliability of the visual analog scale for measurement of acute pain. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:1153–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giesinger JM, Kuijpers W, Young T, Tomaszewski KA, Friend E, Zabernigg A, Holzner B, Aaronson NK. Thresholds for clinical importance for four key domains of the EORTC QLQ-C30: Physical functioning, emotional functioning, fatigue and pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:87. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0489-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunki-Jacobs EM, Philips P, Martin RC., II Evaluation of thermal injury to liver, pancreas and kidney during irreversible electroporation in an in vivo experimental model. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1113–1121. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Underhill CE, Walsh NJ, Bateson BP, Mentzer C, Kruse EJ. Feasibility and safety of irreversible electroporation in locally advanced pelvic and retroperitoneal tumors. Am Surg. 2016;82:e263–e265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kambakamba P, Bonvini JM, Glenck M, Castrezana López L, Pfammatter T, Clavien PA, DeOliveira ML. Intraoperative adverse events during irreversible electroporation-a call for caution. Am J Surg. 2016;212:715–721. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qin Z, Zeng J, Liu G, Long X, Fang G, Li Z, Xu K, Niu L. Irreversible electroporation ablation of an unresectable fibrous sarcoma with 2 electrodes: A case report. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2017 Jan 1; doi: 10.1177/1533034617711530. doi: 10.1177/1533034617711530 (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meng Z, Garrett CR, Shen Y, Liu L, Yang P, Huo Y, Zhao Q, Spelman AR, Ng CS, Chang DZ, Cohen L. Prospective randomised evaluation of traditional Chinese medicine combined with chemotherapy: A randomised phase II study of wild toad extract plus gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:411–416. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin RC, II, Kwon D, Chalikonda S, Sellers M, Kotz E, Scoggins CM, McMasters KM, Watkins K. Treatment of 200 locally advanced (stage III) pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients with irreversible electroporation: Safety and efficacy. Ann Surg. 2015;262:486–494. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Narayanan G, Hosein PJ, Beulaygue IC, Froud T, Scheffer HJ, Venkat SR, Echenique AM, Hevert EC, Livingstone AS, Rocha-Lima CM, et al. Percutaneous image-guided irreversible electroporation for the treatment of unresectable, locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28:342–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2016.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ansari D, Kristoffersson S, Andersson R, Bergenfeldt M. The role of irreversible electroporation (IRE) for locally advanced pancreatic cancer: A systematic review of safety and efficacy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:1165–1171. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2017.1346705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee EW, Thai S, Kee ST. Irreversible electroporation: A novel image-guided cancer therapy. Gut Liver. 2010;4(Suppl 1):S99–S104. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2010.4.S1.S99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bulvik BE, Rozenblum N, Gourevich S, Ahmed M, Andriyanov AV, Galun E, Goldberg SN. Irreversible electroporation versus radiofrequency ablation: A comparison of local and systemic effects in a Small-animal model. Radiology. 2016;280:413–424. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Distelmaier M, Barabasch A, Heil P, Kraemer NA, Isfort P, Keil S, Kuhl CK, Bruners P. Midterm safety and efficacy of irreversible electroporation of malignant liver tumors located close to major portal or hepatic veins. Radiology. 2017;285:1023–1031. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017161561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwarze JE, Jeria R, Crosby J, Villa S, Ortega C, Pommer R. Is there a reason to perform ICSI in the absence of male factor? Lessons from the latin american registry of ART. Hum Reprod Open. 2017;2017:hox013. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hox013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joong Choi C, Roh YH, Kim MC, Choi HJ, Kim YH, Jung GJ. Single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy for gall bladder polyps. JSLS. 2015;19(pii) doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2014.00183. e2014.00183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pirracchio R, Sprung CL, Payen D, Chevret S. Utility of time-dependent inverse-probability-of-treatment weights to analyze observational cohorts in the intensive care unit. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:1373–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated during the present study are included in this published article.