Abstract

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), the most prevalent chronic liver disease in the world, is affected by numerous extrinsic and intrinsic factors, including lifestyle, environment, diet, genetic susceptibility, metabolic syndrome and gut microbiota. Accumulating evidence has proven that gut dysbiosis is significantly associated with the development and progression of NAFLD, and several highly variable species in gut microbiota have been identified. The gut microbiota contributes to NAFLD by abnormal regulation of the liver-gut axis, gut microbial components and microbial metabolites, and affects the secretion of bile acids. Due to the key role of the gut microbiota in NAFLD, it has been regarded as a potential target for the pharmacological and clinical treatment of NAFLD. The present review provides a systematic summary of the characterization of gut microbiota and the significant association between the gut microbiota and NAFLD. The possible mechanisms of how the gut microbiota is involved in promoting the development and progression of NAFLD were also discussed. In addition, the potential therapeutic methods for NAFLD based on the gut microbiota were summarized.

Keywords: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, gut microbiota, liver-gut axis, anti-diabetic

1. Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has become the most prevalent chronic liver disease in the world; an estimated 6–35% of the worldwide are affected and the prevalence of NAFLD has been increasing in recent years due to the improvement of living standards (1,2). It is estimated that NAFLD affects one-third of all adults in the US, and attention to NAFLD in Asian populations has also been paid over the past decades (3–6). NAFLD is characterized by the accumulation of hepatic triglyceride (TG) that exceeds 5% of the total liver weight (7–9). Hepatic steatosis is regarded as the benign beginning of NAFLD, as no severe liver injury is observed during this stage, but certain patients with hepatic steatosis progress to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), NASH-associated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (6,10). Biopsy remains the golden standard for the diagnosis of NAFLD, and in addition, various non-invasive diagnostic methods, including hepatic ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging have been used for detecting hepatic fatty infiltration. Furthermore, magnetic resonance elastography and transient elastography have been frequently used for diagnosing NAFLD with advanced fibrosis (11–13).

NAFLD is a complex disease that may be attributed to a combination of factors, including genetics, diet and gut microbiota (14,15); however, the detailed pathogenesis of NAFLD has remained to be fully elucidated. Common risk factors of NAFLD include aging, lifestyle, central obesity-associated insulin resistance (IR) and the development of metabolic syndrome (16–18). In 1998, Day and James (19) published a theory on the pathogenesis of NAFLD called the ‘two hits’ hypothesis, according to which lipid deposition in the liver was the first hit, while the subsequent second hit includes oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, lipotoxicity and mitochondrial dysfunction. It was the second hit that contributed to the development of NASH. The more recently postulated ‘multiple parallel’ hits hypothesis suggested that inflammatory mediators from various tissues, particularly the adipose and gut tissues, participate in the activation of inflammation, progression of fibrosis and the tumorigenesis (20,21). There is a clear understanding that carriers of certain common genetic variants, including patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3, transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2, membrane-bound O-acyltransferase domain-containing 7 and microsomal TG transfer protein, increase the risk of developing severe forms of NAFLD (22–25).

In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to the role of the gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. Accumulated data proved the significant effects of the gut microbiota on liver function in vivo, which may contribute to numerous physiological processes, including energy metabolism, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and NAFLD (26–28). In the present review, recent evidence for the key roles of the gut microbiota in the development and progression of NAFLD was summarized and the underlying mechanisms were discussed. In addition, the therapeutic potential of anti-diabetic drugs on NAFLD via targeting the gut microbiota was reviewed.

2. Gut microbiota

An estimated 10–100 trillion microbes exist in the human body and most of them are settled in the gut, particularly in the large intestine, reaching a maximum number of up to ~1014 and a weight of ~1.5 kg (29,30). In spite of the wide microbial diversity, only 4 bacterial phyla dominate the gut: Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria, with Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes accounting for ~90% of all gut microbes (31,32). The composition of gut microbiota is variational among different individuals. The ratio of Firmicutes vs. Bacteroidetes has been frequently reported to be associated with the susceptibility to diseases (33,34). It is difficult for traditional microbial technology to obtain a detailed list of gut microbiota, but with the adoption of 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing, an unprecedented view of the diversity of gut microbiota has been gained (34).

Normal gut microbiota may produce numerous substances that provide a benefit for the health of the host via regulation of immunity, supplementation of nutrition and homeostasis, and the gut microbiota has co-evolved with immune system in the regulation of several metabolic pathways (35–37). Accumulated evidence has indicated that the gut microbiota interacts with the liver via the so-called the ‘liver-gut axis’, and certain specific metabolites are involved, including bile acids (BAs), lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) (38). Lipid and carbohydrate metabolism involving several types of bacteria are associated with obesity-associated energy metabolism. Therefore, disorders linked to energy metabolism, including hyperlipidemia, atherosclerosis, diabetes and inflammation, may be regulated by the gut microbiota and their metabolites (35,39,40).

3. Gut dysbiosis and NAFLD

Although an enormous number of microbiota exist in the gut, the proportion and quantity of each species is relatively stable under normal conditions. Changes in the internal and external environment of the host, which may include diet, alcohol intake, antibiotics and genetic factors, may affect the stability of the gut microbiota, resulting in gut microbiota dysbiosis (41). Emerging evidence points out that gut microbiota dysbiosis has a significant role in the pathogenesis of human liver diseases, particularly in NAFLD and associated metabolic disorders (15).

Animal experiments provide strong evidence to support the role of gut microbiota dysbiosis in the development of obesity and NAFLD. In an earlier study, it was indicated that the microbiome in obese mice was associated with increased gain of intestinal energy from the diet. When these mice were co-housed with lean adult germ-free mice for 14 days, this feature was also observed in the previously germ-free mice (42). Membrez et al (43) indicated that the gut microbiota alters the expression of hepatic and intestinal genes involved in the inflammatory, hormonal and metabolic status in mice and improved IR, a key feature of NAFLD. Furthermore, exposure of infants to antibiotics may have a long-term effect on the composition of the gut microbiota and increase the susceptibility to adiposity and NAFLD (44). Cho et al (45) generated a mouse model of obesity to evaluate changes in the capabilities and composition of the gut microbiota by administering antibiotics at subtherapeutic doses. The results indicated that marked changes in gut microbiota components and hepatic metabolism of cholesterol and lipids occurred, along with an increased production of colonic SCFA (45). Similar studies have been performed in humans. One study performed by Vrieze et al (46) indicated that allogenic gut microbiota infusion improved the peripheral insulin sensitivity. Furthermore, low-calorie diet therapy in obese individuals decreased the relative abundance of Firmicutes and increased the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes (33).

Although the changes in the gut microbiota were not entirely consistent among studies, it is definite that the gut microbiota contributes to the development of metabolic syndrome through multiple modes, which are discussed in the chapter below and summarized in Table I (47–80).

Table I.

Summary of studies on the underlying mechanisms of gut microbiota dysbiosis in NAFLD/NASH.

| Mechanism/first author (year) | Notable results | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|

| Gut-liver axis | ||

| Zorn (2009) | The anatomical and biological functions of the intestine and liver are closely associated | (48) |

| Compare (2012) | The majority of blood supply to the liver is derived from the intestinal tract through the portal vein, and the transcription of various pro-inflammatory genes and cytokines in the liver is induced by the toxic substances entering the liver | (51) |

| Clemente (2016) | Change of gut microbes increases the exposure of the liver to pathogen-associated molecular patterns and activates the molecular mechanisms of the innate immune response, therefore contributing to the development of NAFLD | (50) |

| Poeta (2017) | Common origin of the gastrointestinal tract and liver from the ventral foregut endoderm, contributing to the definition of the gut-liver axis | (47) |

| Baffy (2018) | Gut microbiota dysbiosis increases the gut-derived bacterial products entering the liver and induces the proinflammatory response in the liver | (49) |

| SIBO | ||

| Rafiei (2018) | Bloating, dyspepsia, watery diarrhea and hepatic steatosis may all be | (52–54) |

| Sabate (2008) | symptoms of SIBO, which promotes NAFLD progression by increasing | |

| King (2004) | intestinal permeability and endotoxin absorption | |

| Wigg (2001) | SIBO increased endotoxin absorption, leading to the progression of NAFLD by | (55,57) |

| Boulange (2016) | raising TNF-α levels | |

| Ghoshal (2017) | Low-grade SIBO observed in NASH patients with the currently recognized gold standard method | (56) |

| Shanab (2011) | SIBO may have an important role in NASH by interacting with TLR-4 and inducing the expression of proinflammatory cytokine IL-8 | (58) |

| Fukunishi (2014) | SIBO is associated with endogenous ethanol production, which may impair | (59,60) |

| Ferolla (2014) | intestinal function and morphology, thereby leading to systemic inflammation and insulin resistance | |

| Microbial metabolites | ||

| D'Mello (2015) | The metabolites of the gut microbiota, including endotoxins, activate the | (61,62) |

| Mutlu (2009) | inflammatory response in the liver when they cannot be cleared by kuppfer cells | |

| Vrieze (2012) | Gut bacterial-derived endotoxins may interact with pattern recognition receptors, | (46,63) |

| Li (2016) | including TLRs, which are expressed in various cells in the liver, including macrophages and kuppfer cells | |

| Leavy (2015) | The complex formed by LPS and LBP binds with CD14 to activate the innate immune recognition system | (64) |

| Ruiz (2007) | Elevated serum LBP levels and TNF-α overexpression were observed in NAFLD and NASH patients, and the serum LBP levels and TNF-α expression were higher in NASH patients than in NAFLD patients | (65) |

| Liu (2014) | Activation of the TLR4 signaling pathway significantly increases the release of a series of inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-12, and participates in multiple steps of the development and progression of NAFLD | (66) |

| Leoni (2018) | Dysregulation of proinflammatory cytokines and adipokines is almost universally | (67–70) |

| Nobili (2012) | present in NAFLD patients, which directly or indirectly (mainly through the | |

| Yoon (2014) | TLR4 signaling pathway) lead to hepatocyte injury. In addition, oxidative stress | |

| Temple (2016) | and hepa tocyte apoptosis are associated with the progression of NASH | |

| Berardis (2014) | TLR antagonists possess the effect of inhibiting the activation of inflammation, and may therefore be regarded as effective therapeutic agents for the treatment of NASH Effects of BA | (71) |

| Yu (2018) | A variety of transporters participate in the circulation of BAs between liver and | (72,73) |

| Chow (2017) | intestine; BAs promote the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins, and regulate lipids and glucose homeostasis | |

| Chavez-Talavera (2017) | BAs regulate the metabolism and inflammation through FXR and Takeda G-protein | (74,75) |

| Park (2016) | receptor 5, which possess the function of controlling the metabolism of BAs, lipids and carbohydrates, and regulating the expression of inflammatory genes | |

| Janssen (2017) | FXR is able to activate small heterodimer partner to reduce the expression of | (76,77) |

| Puri (2017) | sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1, which is a major regulator in new fat formation; inhibition of FXR leads to the abnormal lipid metabolism and development of NAFLD | |

| Zhang (2016) | Hereditary obesity, insulin resistance and NAFLD may be prevented or reversed by glycine-β-muricholic acid, an intestinal FXR antagonist, which possesses the ability to change the intestinal bacterial composition. | (78) |

| Sepe (2018) | FXR has been identified as a promising pharmacological target for NAFLD | (79,80) |

| Cruz-Ramón (2017) | considering its significant role in homeostasis of BAs, glucose and lipids |

NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; TGF, transforming growth factor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; SIBO, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth; FXR, farnesoid X receptor; TLR, Toll-like receptor; IL, interleukin; LPS, lipopolysaccharides; LBP, LPS binding protein; BA, bile acids.

4. Mechanisms of gut microbiota dysbiosis in NAFLD/NASH

Gut-liver axis

The liver and intestine originate from the ventral foregut endoderm during the process of embryonic development; therefore, an intrinsic association exists between the anatomical and biological functions of the liver and intestine (47,48). Anatomically, the liver and intestine are interconnected through the portal vein, and 70–75% of the liver's blood supply comes from the intestine through the portal vein. At the same time, an array of bacteria, bacterial metabolites and environmental toxins, which are derived from the intestine, may reach the liver through the portal vein (49). In recent years, emerging evidence has indicated that dysfunction of the gut-liver axis, including mucosa permeability alteration, bacterial overgrowth and intestinal dysbiosis, significantly contribute to the development and progression of NAFLD (50). Therefore, the systemic endotoxin concentration, increased permeability of the intestinal epithelium and endogenous ethanol levels may reflect an abnormal gut-liver axis function in hepatic diseases. In addition, all of the above-mentioned factors may trigger the production of a cascade of cytokines, activating the uncontrolled immune response and causing the release of multiple inflammatory mediators (48,51).

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

SIBO is usually defined as the presence of >105 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml in duodenal aspirate cultures (52). Dyspepsia, abdominal discomfort, watery diarrhea, bloating, nutrient malabsorption, flatulence and hepatic steatosis are all clinical manifestations of SIBO (53,54). Accumulated evidence suggested that SIBO is common in NAFLD patients and has an important role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. In 2001, Wigg et al (55) investigated SIBO in NASH patients and healthy controls. They reported that SIBO was observed in 50% of NASH patients and 22% of healthy controls, and the mean levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in NASH patients and controls were 14.2 and 7.5 pg/ml, respectively. Ghoshal et al (56) determined the amount of intestinal bacteria using quantitative jejunal aspirate culture and the glucose hydrogen breath test, and the results indicated low-grade SIBO (≥103 CFU/ml) in NASH patients compared with that in controls. These results confirmed that patients with NASH have an increased prevalence of SIBO.

Various observational studies in NAFLD patients and experimental studies in animals have been performed to explore the detailed pathogenesis of SIBO in NAFLD. Wigg et al (55) and Boulangé et al (57) reported that SIBO increased intestinal permeability and endotoxin absorption, thereby leading to gut inflammation, dysmotility and various immunological changes in the gut, which may contribute to the development of liver injury. Shanab et al (58) proved that SIBO in patients with NASH was associated with enhanced hepatic release of interleukin-8 and expression of Toll-like receptor (TLR)4, contributing to the development and progression of NASH. Zucker rats were fed on a diet rich in LPS to simulate the endotoxin coming from the intestinal microbiota, and significantly higher levels of plasma insulin and glucose were observed after 24 weeks of feeding. These results suggested that LPS aggravated the development of IR (59). Gut-derived endogenous endotoxin, including LPS, may have an important role in the activation of Kupffer cells to produce cytokines, including TNF-α, which has been suggested to cause IR. IR increases the accumulation of hepatic TG by promoting peripheral lipolysis, TG synthesis and hepatic uptake of free FAs (59,60). From the above, it is apparent that SIBO participates in the pathogenesis of NAFLD by increasing intestinal permeability to induce inflammation and IR.

Microbial metabolites

Interactions among the gut microflora, the liver and the immune system trigger the inflammatory response pathway of the intestinal flora in the body (61). Under normal conditions, less intestinal bacterial products, including endotoxin, enter the portal circulation by permeating the normal intestinal barrier and reach the liver (62). Permeated endotoxin may be detected by pattern recognition receptors, including TLRs, which are located on Kupffer cells, and the Kupffer cells then eliminate the endotoxin in the liver (46,63). LPS is the major structural component of Gram-negative bacteria and the major component of endotoxin. LPS may be recognized by LPS-binding protein (LBP) in serum and is the major activator of the innate immune response (64). Ruiz et al (65) indicated that the serum levels of LBP were increased in obese patients with NASH compared to patients with simple steatosis (P<0.05), and the increased serum LBP level was correlated to an upregulated expression of TNF-α in the liver tissue. This result supported that endotoxin has a key role in the development of steatohepatitis in obese patients (65). Furthermore, TLR4-mutant mice induced by high fat and high fructose were more susceptible to steatohepatitis and overexpression of inflammation-associated factors than wild-type mice, which suggested that the TLR4 signaling pathway participates in the pro-inflammatory response in the liver (66). Of note, abnormal levels of adipokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines were observed in almost all NAFLD patients, and endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria and cytokine-mediated oxidative stress were indicated to promote the development of NASH via the TLR signaling pathway (67–70). Thus, TLR antagonists may be effective therapeutic agents for NASH that are worthy of further study (71).

Effects of BAs

The hepatic load of BAs is derived from the intestine and has numerous functions, including the promotion of gastrointestinal absorption of fat and fat-soluble vitamins, inhibition of overgrowth of the intestinal microflora and gain of weight (72). Therefore, BAs have an important role in the development of NAFLD. In the colon, primary BAs are transformed into secondary BAs through various bacterial-mediated modifications, including deconjugation and dihydroxylation (73). Farnesoid X receptor (FXR), a nuclear receptor known to be involved in hepatic and intestinal BA metabolism, and Takeda G-protein-coupled receptor 5 have key roles in glucose and energy metabolism and are the most significant BA receptors in the liver (74,75). Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptor 2/sphingosine kinase 2/S1P signaling lowers the hepatic lipid content by modulating the expression of nuclear receptors (including FXR) and proteins involved in lipid metabolism. The gut microbiota regulates the lipid and lipoprotein metabolism in an FXR-dependent manner, including acting on hepatic lipogenesis, as well as lipoprotein secretion, plasma clearance and intestinal cholesterol absorption. In addition, FXR reduces TG-rich lipoproteins through a variety of mechanisms. For instance, FXR reduces lipogenesis by repressing hepatic sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP)1c expression in small heterodimer partner (SHP)-79- and fibroblast growth factor 15/19-dependent manners, reduces very low-density lipoprotein secretion by repressing microsomal TG transfer protein and apolipoprotein B gene expression, and stimulates intravascular lipolysis of TG-rich lipoproteins by enhancing lipoprotein lipase activity (74). Microbiota-associated BA deconjugation may accelerate fat synthesis by activating the intestinal FXR signaling pathway and blocking the hepatic FXR-SHP signaling pathway. FXR activation may prevent the progression of NAFLD, as it reduces steatosis by inhibiting lipogenesis, decreases chemically induced hepatitis and maintains the integrity of the intestinal barrier, thus protecting the liver from bacteria-derived inflammatory signals. As these factors were put together, downregulation of hepatic FXR receptor led to enhanced lipogenesis and suppressed FA β-oxidation, thereby promoting the development of NAFLD (76,77).

To explore the functional association between changes of the gut microbiota and the host's metabolic syndrome, Zhang et al (78) treated the HFD-fed mice with a potent FXR antagonist, Gly-β-muricholic acid. A marked improvement of obesity-associated metabolic disorders in the liver was observed after 8 weeks of treatment, which suggested that hepatic changes were associated with the significantly modulated gut microbiota (78). Janssen et al (76) reported that elevated BAs in plasma and liver tissue are potentially linked to changes of the gut microbial composition, NAFLD-associated hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in a mouse model, suggesting a possible mechanism through which the gut microbiota promotes the progression of NAFLD by interfering with the normal metabolism of BAs. In summary, gut microbiota dysbiosis promotes NAFLD, likely through regulating BA metabolism by the intestinal flora to target the FXR. In consideration of the key role of FXR in NAFLD, FXR has been identified as a promising pharmacological target for the treatment of abnormal liver BA and lipid metabolism diseases, including cholestasis and NAFLD (79,80).

5. Gut microbiota-based treatments for NAFLD/NASH

Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics supplementation

Studies on animal models have provided evidence that probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics possess significant modulatory effects on the intestinal microbiota. Oral administration of probiotics and prebiotics, as well as supplementation of synbiotics, contributed to the treatment of NAFLD by improving the abnormal lipid metabolism and gut microbiota dysbiosis (81). Alves et al (82) reported that prebiotic and synbiotic supplementation in rats improved hypercholesterolemia-associated hepatic changes by regulating the expression of genes involved in β-oxidation [peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-α (PPAR-α) and carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT-1)] and lipogenesis [sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c), fatty acid synthase (FAS) and malic enzyme (ME)]. Another study indicated that supplementation with probiotics (Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium) attenuated hepatic fat accumulation in rats receiving a high-fat diet (HFD), but no significant differences of intestinal permeability were observed in probiotics group compared to control (83). Raso et al (84) indicated that a HFD induced overexpression of TLR4 and CD14 at the mRNA and protein levels in a rat model. After the rats were treated with synbiotics, hepatic inflammation and IR were improved and the amount of Gram-negative Enterobacteriales and Escherichia coli in colonic mucosa was reduced. In pediatric patients with obesity NAFL and NASH, Nobili et al (85) observed that the amount of Bifidobacterium spp. was significantly decreased compared with that in a control group, suggesting that Bifidobacterium spp. may possess a protective effect against obesity and NAFLD. All of these results highlight that understanding the detailed mechanisms of gut microbiota in NAFLD and identification of beneficial bacteria are important for the exploration of microbiota-targeted therapeutic methods for NAFLD.

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT)

FMT, a method used to re-populate the gut microbiota of patients with a healthy intestinal flora, is currently being tested as a promising treatment method for various diseases (86–88). Application of FMT in the treatment of NAFLD/NASH has been widely explored. Early studies using mouse models by Zhou et al (89) and Le Roy et al (90) indicated that intrahepatic lipid accumulation, IR and increased pro-inflammatory cytokines were improved by FMT. In a randomized controlled trial, patients with metabolic syndrome received the gut microbiota from lean healthy Caucasian males via duodenal tube. Increased insulin sensitivity (median rate of glucose disappearance, 26.2 vs. 45.3 mol/kg/min; P<0.05) and gut microbial diversity (178±62 vs. 234±40 species; P<0.05) of recipients was observed after 6 weeks of FMT (46). These studies suggest that FMI may be developed as a potential therapeutic method to regulate lipid and glucose metabolism in NAFLD patients. However, the optimal FMT method and bacterial species for transplantation require to be further identified.

Anti-diabetic drugs

IR is one of the major features of T2DM (91). Over the past decade, IR and NAFLD/NASH have been widely elucidated. Patients with abundant obesity-associated rather than genetics-associated NAFLD present with severe IR. Once visceral adipose tissue becomes insufficient to store excess fat, the latter start to ectopically accumulate in key sensitive organs, including the liver, hence causing systemic IR (92). Excessive deposition of TG in the liver may promote lipid peroxidation and accumulation of reactive oxygen species, resulting in a variety of cellular stimuli with subsequent inflammatory response, hepatocellular injury and fibrosis. IR accelerated the above processes that led to the development of NAFLD to NASH, cirrhosis and even HCC. Therefore, novel anti-diabetic drugs may serve as significant candidates for the treatment of NAFLD/NASH by improving IR and gut microbiota dysbiosis (Table II) (93,94).

Table II.

Effects of anti-diabetic drugs on the gut microbiota in NAFLD-associated diseases.

| Patient type/first author (year) | Model | Drug | Sample used for analysis | Bacterial changes | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAFLD/NASH | |||||

| Shin (2017) | NAFLD | Metformin | Feces | ↓ Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria | (101) |

| rats | ↑ Firmicutes | ||||

| Kishida (2017) | NASH | Miglitol | Feces | ↓ Bacteroidetes | (102) |

| mice | ↑ Actinobacteria | ||||

| Obesity | |||||

| Zhang (2015) | Mice | Metformin | Feces | ↓ - | (103) |

| ↑ Firmicutes, Verrucomicrobia, Proteobacteria, | |||||

| Bacteroidetes | |||||

| Shin (2014) | Mice | Metformin | Feces | ↓ Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria | (98) |

| ↑ Verrucomicrobia | |||||

| Lee (2014) | Mice | Metformin | Feces | ↓ - | (99) |

| ↑ Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Verrucomicrobia | |||||

| Bai (2016) | Mice | Pioglitazone | Feces | ↓ Proteobacteria | (104) |

| ↑ - | |||||

| Wang (2016) | Mice | Saxagliptin | Feces | ↓ Bacteroidetes, | (105) |

| ↑ Firmicutes | |||||

| Wang (2016) | Mice | Liraglutide | Feces | ↓↑ Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria | (105) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | ↓ Actinobacteria | ||||

| Yan (2016) | Mice | Sitagliptin | Feces | ↓↑ Firmicutes | (106) |

| ↑ Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria | |||||

| Wu (2017) | Human | Metformin | Stool | ↓ Firmicutes | (107) |

| ↑ Verrucomicrobia, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria | |||||

| de la Cuesta- | Human | Metformin | Stool | ↓ - | (108) |

| Zuluaga (2017) | ↑ Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Verrucomicrobia, | ||||

| Actinobacteria | |||||

| Forslund (2015) | Human | Metformin | Stool | ↓↑ Firmicutes | (109) |

| ↑ Proteobacteria | |||||

| Zhang (2017) | Human | Acarbose | Stool | ↓↑ Firmicutes | (110) |

| ↑ Bacteroidetes |

NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; -, no related change was observed.

Metformin is currently the first-line drug against T2DM on account of its good effect to improve insulin sensitivity and reduce blood glucose (95). Previous studies suggested that metformin possesses promising potential in terms of gut-based pharmacology, including the alteration of gut microbiota and BA recirculation (96,97). Shin et al (98) reported that treatment with metformin for 6 weeks modulated the gut microbiota composition in mice with HFD-induced obesity. Lee and Ko (99) reported that metformin improved metabolic disorders, including hyperglycemia, obesity and hypercholesterolemia in mice receiving a HFD, and the composition of the gut microbiota was also changed after metformin treatment. Similarly, another anti-diabetic drug, the α-glucosidase inhibitor voglibose, reversed the increased ratio of Firmicutes vs. Bacteroidetes in the gut microbiota of mice on a HFD (100). In Table II, the detailed effects of anti-diabetic drugs on the composition of the gut microbiota in NAFLD-associated diseases reported by most of the studies published to date are summarized (98,99,101–110). While the detailed mechanisms of action of anti-diabetic drugs on the gut microbiota remain elusive, those drugs have been proven to be a promising therapeutic option to control NAFLD/NASH.

6. Conclusions

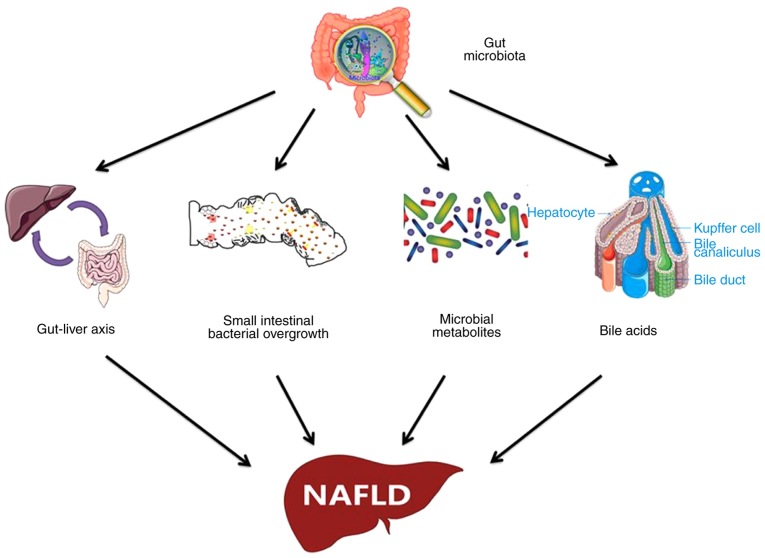

More attention should be paid to the early diagnosis and treatment of NAFLD as the most prevalent chronic liver disease worldwide. For the management of NAFLD as a multi-factorial disease, a healthy lifestyle and reasonable diet should be implemented. The gut microbiota significantly contributes to the development and progression of NAFLD, and a vast amount of evidence has been provided to shed light on the pathogenesis of the gut microbiota in NAFLD (Fig. 1). Although certain changes in the gut microbiota observed by previous studies were not specific and the compositional alterations were not absolutely consistent, it is apparent that gut microbiota-based treatment methods for NAFLD are promising. Future studies should focus on elucidating the detailed mechanisms of the gut microbiota in NAFLD and determining NAFLD-associated microbial species to thus pave the road for the development of more specific medicines and effective therapeutic methods for NAFLD based on the gut microbiota.

Figure 1.

Underlying mechanism of gut microbiota dysbiosis in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by Grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31770837) and the Qingdao People's Livelihood Science and Technology Plan (grant no. 18-6-1-68-nsh).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

QL, SSL, LZC, ZZZ, SXD and QJD contributed to the acquisition, analysis and systematization of data. QL and SSL wrote the manuscript. The manuscript was critically revised for important intellectual content by YNX and SYX. YNX and SYX conceived the present study. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Borrelli A, Bonelli P, Tuccillo FM, Goldfine ID, Evans JL, Buonaguro FM, Mancini A. Role of gut microbiota and oxidative stress in the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease to hepatocarcinoma: Current and innovative therapeutic approaches. Redox Biol. 2018;15:467–479. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rinella ME. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review. JAMA. 2015;313:2263–2273. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.5370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma M, Mitnala S, Vishnubhotla RK, Mukherjee R, Reddy DN, Rao PN. The riddle of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Progression from nonalcoholic fatty liver to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2015;5:147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farrell GC, Wong VW, Chitturi S. NAFLD in Asia-as common and important as in the West. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:307–318. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong VW. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Asia: A story of growth. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:18–23. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chitturi S, Wong VW, Farrell G. Nonalcoholic fatty liver in Asia: Firmly entrenched and rapidly gaining ground. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(Suppl 1):S163–S172. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simeone JC, Bae JP, Hoogwerf BJ, Li Q, Haupt A, Ali AK, Boardman MK, Nordstrom BL. Clinical course of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: An assessment of severity, progression, and outcomes. Clin Epidemiol. 2017;9:679–688. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S144368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Caldwell SH. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Summary of an AASLD single topic conference. Hepatology. 2003;37:1202–1219. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, Behling C, Contos MJ, Cummings OW, Ferrell LD, Liu YC, Torbenson MS, Unalp-Arida A, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41:1313–1321. doi: 10.1002/hep.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lonardo A, Byrne CD, Caldwell SH, Cortez-Pinto H, Targher G. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:1388–1389. doi: 10.1002/hep.28584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim D, Kim WR, Talwalkar JA, Kim HJ, Ehman RL. Advanced fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Noninvasive assessment with MR elastography. Radiology. 2013;268:411–419. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13121193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim D, Touros A, Kim WR. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome. Clin Liver Dis. 2018;22:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong VW, Vergniol J, Wong GL, Foucher J, Chan HL, Le Bail B, Choi PC, Kowo M, Chan AW, Merrouche W, et al. Diagnosis of fibrosis and cirrhosis using liver stiffness measurement in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:454–462. doi: 10.1002/hep.23312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL)1; European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO), corp-author EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64:1388–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leung C, Rivera L, Furness JB, Angus PW. The role of the gut microbiota in NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:412–425. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meex RCR, Watt MJ. Hepatokines: Linking nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and insulin resistance. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13:509–520. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ricketts ML, Ferguson BS. Polyphenols: Novel signaling pathways. Curr Pharm Des. 2018;24:158–170. doi: 10.2174/1381612824666171129204054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu J, Wan X, Wang Y, Zhu K, Li C, Yu C, Li Y. Serum fetuin B level increased in subjects of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A case-control study. Endocrine. 2017;56:208–211. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-1112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Day CP, James OF. Steatohepatitis: A tale of two ‘hits’? Gastroenterology. 1998;114:842–845. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tilg H, Moschen AR. Evolution of inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: The multiple parallel hits hypothesis. Hepatology. 2010;52:1836–1846. doi: 10.1002/hep.24001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tiniakos DG, Vos MB, Brunt EM. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Pathology and pathogenesis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:145–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birerdinc A, Younossi ZM. Epigenome-wide association studies provide insight into the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Ann Hepatol. 2018;17:11–13. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.7530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benedict M, Zhang X. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: An expanded review. World J Hepatol. 2017;9:715–732. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i16.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li TT, Li TH, Peng J, He B, Liu LS, Wei DH, Jiang ZS, Zheng XL, Tang ZH. TM6SF2: A novel target for plasma lipid regulation. Atherosclerosis. 2018;268:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Del Campo JA, Gallego-Durán R, Gallego P, Grande L. Genetic and epigenetic regulation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:E911. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park JS, Seo JH, Youn HS. Gut microbiota and clinical disease: Obesity and nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2013;16:22–27. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2013.16.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, Nielsen T, Pons N, Levenez F, Yamada T, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santacruz A, Collado MC, García-Valdés L, Segura MT, Martín-Lagos JA, Anjos T, Martí-Romero M, Lopez RM, Florido J, Sanz Y. Gut microbiota composition is associated with body weight, weight gain and biochemical parameters in pregnant women. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:83–92. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510000176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ursell LK, Clemente JC, Rideout JR, Gevers D, Caporaso JG, Knight R. The interpersonal and intrapersonal diversity of human-associated microbiota in key body sites. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1204–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neish AS. Microbes in gastrointestinal health and disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:65–80. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mokhtari Z, Gibson DL, Hekmatdoost A. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, the gut microbiome, and diet. Adv Nutr. 2017;8:240–252. doi: 10.3945/an.116.013151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clemente JC, Ursell LK, Parfrey LW, Knight R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: An integrative view. Cell. 2012;148:1258–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444:1022–1023. doi: 10.1038/4441022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang X, Chen Y, Zhu J, Zhang M, Ho CT, Huang Q, Cao J. Metagenomics analysis of gut microbiota in a high fat diet-induced obesity mouse model fed with (−)-epigallocatechin 3-O-(3-O-Methyl) gallate (EGCG3′'Me) Mol Nutr Food Res. 2018;62:e1800274. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201800274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Devillard E, McIntosh FM, Duncan SH, Wallace RJ. Metabolism of linoleic acid by human gut bacteria: Different routes for biosynthesis of conjugated linoleic acid. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:2566–2570. doi: 10.1128/JB.01359-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li X, Li C. Analysis of changes in intestinal flora and intravascular inflammation and coronary heart disease in obese patients. Exp Ther Med. 2018;15:4538–4542. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.5987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li CY, Dempsey JL, Wang D, Lee S, Weigel KM, Fei Q, Bhatt DK, Prasad B, Raftery D, Gu H, Cui JY. PBDEs altered gut microbiome and bile acid homeostasis in Male C57BL/6 mice. Drug Metab Dispos. 2018;46:1226–1240. doi: 10.1124/dmd.118.081547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zununi Vahed S, Moghaddas Sani H, Rahbar Saadat Y, Barzegari A, Omidi Y. Type 1 diabetes: Through the lens of human genome and metagenome interplay. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;104:332–342. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baddini Feitoza A, Fernandes Pereira A, Ferreira da Costa N, Gonçalves Ribeiro B. Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA): Effect modulation of body composition and lipid profile. Nutr Hosp. 2009;24:422–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang C, Björkman A, Cai K, Liu G, Wang C, Li Y, Xia H, Sun L, Kristiansen K, Wang J, et al. Impact of a 3-months vegetarian diet on the gut microbiota and immune repertoire. Front Immunol. 2018;9:908. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shin NR, Whon TW, Bae JW. Proteobacteria: Microbial signature of dysbiosis in gut microbiota. Trends Biotechnol. 2015;33:496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444:1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Membrez M, Blancher F, Jaquet M, Bibiloni R, Cani PD, Burcelin RG, Corthesy I, Corthesy I, Macé K, Chou CJ. Gut microbiota modulation with norfloxacin and ampicillin enhances glucose tolerance in mice. FASEB J. 2008;22:2416–2426. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-102723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Azad MB, Bridgman SL, Becker AB, Kozyrskyj AL. Infant antibiotic exposure and the development of childhood overweight and central adiposity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014;38:1290–1298. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cho I, Yamanishi S, Cox L, Methé BA, Zavadil J, Li K, Gao Z, Mahana D, Raju K, Teitler I, et al. Antibiotics in early life alter the murine colonic microbiome and adiposity. Nature. 2012;488:621–626. doi: 10.1038/nature11400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vrieze A, Van Nood E, Holleman F, Salojärvi J, Kootte RS, Bartelsman JF, Dallinga-Thie GM, Ackermans MT, Serlie MJ, Oozeer R, et al. Transfer of intestinal microbiota from lean donors increases insulin sensitivity in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:913–916.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poeta M, Pierri L, Vajro P. Gut-liver axis derangement in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Children (Basel) 2017;4:E66. doi: 10.3390/children4080066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zorn AM, Wells JM. Vertebrate endoderm development and organ formation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:221–251. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baffy G. Potential mechanisms linking gut microbiota and portal hypertension. Liver Int. 2019;39:598–609. doi: 10.1111/liv.13986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clemente MG, Mandato C, Poeta M, Vajro P. Pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Recent solutions, unresolved issues, and future research directions. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8078–8093. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i36.8078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Compare D, Coccoli P, Rocco A, Nardone OM, De Maria S, Carteni M, Nardone G. Gut-liver axis: The impact of gut microbiota on non alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;22:471–476. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rafiei R, Bemanian M, Rafiei F, Bahrami M, Fooladi L, Ebrahimi G, Hemmat A, Torabi Z. Liver disease symptoms in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Rom J Intern Med. 2018;56:85–89. doi: 10.1515/rjim-2017-0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sabaté JM, Jouët P, Harnois F, Mechler C, Msika S, Grossin M, Coffin B. High prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with morbid obesity: A contributor to severe hepatic steatosis. Obes Surg. 2008;18:371–377. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.King T. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and irritable bowel syndrome. JAMA. 2004;292:2213–2214. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.18.2213-a. 2213; author reply. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wigg AJ, Roberts-Thomson IC, Dymock RB, McCarthy PJ, Grose RH, Cummins AG. The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, intestinal permeability, endotoxaemia, and tumour necrosis factor alpha in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Gut. 2001;48:206–211. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ghoshal UC, Baba CS, Ghoshal U, Alexander G, Misra A, Saraswat VA, Choudhuri G. Low-grade small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is common in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis on quantitative jejunal aspirate culture. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2017;36:390–399. doi: 10.1007/s12664-017-0797-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boulangé CL, Neves AL, Chilloux J, Nicholson JK, Dumas ME. Impact of the gut microbiota on inflammation, obesity, and metabolic disease. Genome Med. 2016;8:42. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0303-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shanab AA, Scully P, Crosbie O, Buckley M, O'Mahony L, Shanahan F, Gazareen S, Murphy E, Quigley EM. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Association with toll-like receptor 4 expression and plasma levels of interleukin 8. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1524–1534. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1447-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fukunishi S, Sujishi T, Takeshita A, Ohama H, Tsuchimoto Y, Asai A, Tsuda Y, Higuchi K. Lipopolysaccharides accelerate hepatic steatosis in the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Zucker rats. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2014;54:39–44. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.13-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferolla SM, Armiliato GN, Couto CA, Ferrari TC. The role of intestinal bacteria overgrowth in obesity-related nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutrients. 2014;6:5583–5599. doi: 10.3390/nu6125583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.D'Mello C, Ronaghan N, Zaheer R, Dicay M, Le T, MacNaughton WK, Surrette MG, Swain MG. Probiotics improve inflammation-associated sickness behavior by altering communication between the peripheral immune system and the brain. J Neurosci. 2015;35:10821–10830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0575-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mutlu E, Keshavarzian A, Engen P, Forsyth CB, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet P. Intestinal dysbiosis: A possible mechanism of alcohol-induced endotoxemia and alcoholic steatohepatitis in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1836–1846. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01022.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li F, Duan K, Wang C, McClain C, Feng W. Probiotics and alcoholic liver disease: Treatment and potential mechanisms. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:5491465. doi: 10.1155/2016/5491465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leavy O. Innate immunity: New PAMP discovered. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:402–403. doi: 10.1038/nri3872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ruiz AG, Casafont F, Crespo J, Cayón A, Mayorga M, Estebanez A, Fernadez-Escalante JC, Pons-Romero F. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein plasma levels and liver TNF-alpha gene expression in obese patients: Evidence for the potential role of endotoxin in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Obes Surg. 2007;17:1374–1380. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu J, Zhuang ZJ, Bian DX, Ma XJ, Xun YH, Yang WJ, Luo Y, Liu YL, Jia L, Wang Y, et al. Toll-like receptor-4 signalling in the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease induced by high-fat and high-fructose diet in mice. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;41:482–488. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leoni S, Tovoli F, Napoli L, Serio I, Ferri S, Bolondi L. Current guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review with comparative analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3361–3373. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i30.3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nobili V, Carpino G, Alisi A, Franchitto A, Alpini G, De Vito R, Onori P, Alvaro D, Gaudio E. Hepatic progenitor cells activation, fibrosis, and adipokines production in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2012;56:2142–2153. doi: 10.1002/hep.25742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yoon HJ, Cha BS. Pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:800–811. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v6.i11.800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Temple JL, Cordero P, Li J, Nguyen V, Oben JA. A guide to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in childhood and adolescence. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:947. doi: 10.3390/ijms17060947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Berardis S, Sokal E. Pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: An increasing public health issue. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173:131–139. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-2157-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yu Q, Jiang Z, Zhang L. Bile acid regulation: A novel therapeutic strategy in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;190:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chow MD, Lee YH, Guo GL. The role of bile acids in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Mol Aspects Med. 2017;56:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chávez-Talavera O, Tailleux A, Lefebvre P, Staels B. Bile acid control of metabolism and inflammation in obesity, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1679–1694.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Park MY, Kim SJ, Ko EK, Ahn SH, Seo H, Sung MK. Gut microbiota-associated bile acid deconjugation accelerates hepatic steatosis in ob/ob mice. J Appl Microbiol. 2016;121:800–810. doi: 10.1111/jam.13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Janssen AWF, Houben T, Katiraei S, Dijk W, Boutens L, van der Bolt N, Wang Z, Brown JM, Hazen SL, Mandard S, et al. Modulation of the gut microbiota impacts nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A potential role for bile acids. J Lipid Res. 2017;58:1399–1416. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M075713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Puri P, Daita K, Joyce A, Mirshahi F, Santhekadur PK, Cazanave S, Luketic VA, Siddiqui MS, Boyett S, Min HK, et al. The presence and severity of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is associated with specific changes in circulating bile acids. Hepatology. 2017 Jul 11; doi: 10.1002/hep.29359. (Epub ahead of print) Doi: 10.1002/hep.29359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang L, Xie C, Nichols RG, Chan SH, Jiang C, Hao R, Smith PB, Cai J, Simons MN, Hatzakis E, et al. Farnesoid X receptor signaling shapes the gut microbiota and controls hepatic lipid metabolism. mSystems. 2016;1:e00070–16. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00070-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sepe V, Distrutti E, Fiorucci S, Zampella A. Farnesoid X receptor modulators 2014-present: A patent review. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2018;28:351–364. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2018.1459569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cruz-Ramón V, Chinchilla-López P, Ramírez-Pérez O, Méndez-Sánchez N. Bile acids in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: New concepts and therapeutic advances. Ann Hepatol. 2017;16(Suppl 1: S3-S105):S58–S67. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.5498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Belei O, Olariu L, Dobrescu A, Marcovici T, Marginean O. The relationship between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth among overweight and obese children and adolescents. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2017;30:1161–1168. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2017-0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alves CC, Waitzberg DL, de Andrade LS, Dos Santos Aguiar L, Reis MB, Guanabara CC, Júnior OA, Ribeiro DA, Sala P. Prebiotic and synbiotic modifications of beta oxidation and lipogenic gene expression after experimental hypercholesterolemia in rat liver. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2010. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xu RY, Wan YP, Fang QY, Lu W, Cai W. Supplementation with probiotics modifies gut flora and attenuates liver fat accumulation in rat nonalcoholic fatty liver disease model. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2012;50:72–77. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.11-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Raso GM, Simeoli R, Iacono A, Santoro A, Amero P, Paciello O, Russo R, D'Agostino G, Di Costanzo M, Canani RB, et al. Effects of a Lactobacillus paracasei B21060 based synbiotic on steatosis, insulin signaling and toll-like receptor expression in rats fed a high-fat diet. J Nutr Biochem. 2014;25:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nobili V, Putignani L, Mosca A, Chierico FD, Vernocchi P, Alisi A, Stronati L, Cucchiara S, Toscano M, Drago L. Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli in the gut microbiome of children with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Which strains act as health players? Arch Med Sci. 2018;14:81–87. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.62150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bakker GJ, Nieuwdorp M. Fecal microbiota transplantation: Therapeutic potential for a multitude of diseases beyond Clostridium difficile. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5 doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.BAD-0008-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.de Groot PF, Frissen MN, de Clercq NC, Nieuwdorp M. Fecal microbiota transplantation in metabolic syndrome: History, present and future. Gut Microbes. 2017;8:253–267. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2017.1293224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Woodhouse CA, Patel VC, Singanayagam A, Shawcross DL. Review article: The gut microbiome as a therapeutic target in the pathogenesis and treatment of chronic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:192–202. doi: 10.1111/apt.14397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhou D, Pan Q, Shen F, Cao HX, Ding WJ, Chen YW, Fan JG. Total fecal microbiota transplantation alleviates high-fat diet-induced steatohepatitis in mice via beneficial regulation of gut microbiota. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1529. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01751-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Le Roy T, Llopis M, Lepage P, Bruneau A, Rabot S, Bevilacqua C, Martin P, Philippe C, Walker F, Bado A, et al. Intestinal microbiota determines development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Gut. 2013;62:1787–1794. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gutiérrez-Rodelo C, Roura-Guiberna A, Olivares-Reyes JA. Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance: An update. Gac Med Mex. 2017;153:214–228. (In Spanish) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Manco M. Insulin resistance and NAFLD: A dangerous liaison beyond the genetics. Children (Basel) 2017;4:E74. doi: 10.3390/children4080074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Montandon SA, Jornayvaz FR. Effects of antidiabetic drugs on gut microbiota composition. Genes (Basel) 2017;8:E250. doi: 10.3390/genes8100250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sumida Y, Seko Y, Yoneda M, Japan Study Group of NAFLD (JSG-NAFLD) Novel antidiabetic medications for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hepatol Res. 2017;47:266–280. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pernicova I, Korbonits M. Metformin-mode of action and clinical implications for diabetes and cancer. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10:143–156. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Napolitano A, Miller S, Nicholls AW, Baker D, Van Horn S, Thomas E, Rajpal D, Spivak A, Brown JR, Nunez DJ. Novel gut-based pharmacology of metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100778. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Brunkwall L, Orho-Melander M. The gut microbiome as a target for prevention and treatment of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes: From current human evidence to future possibilities. Diabetologia. 2017;60:943–951. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4278-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shin NR, Lee JC, Lee HY, Kim MS, Whon TW, Lee MS, Bae JW. An increase in the Akkermansia spp. population induced by metformin treatment improves glucose homeostasis in diet-induced obese mice. Gut. 2014;63:727–735. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lee H, Ko G. Effect of metformin on metabolic improvement and gut microbiota. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:5935–5943. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01357-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Do HJ, Lee YS, Ha MJ, Cho Y, Yi H, Hwang YJ, Hwang GS, Shin MJ. Beneficial effects of voglibose administration on body weight and lipid metabolism via gastrointestinal bile acid modification. Endocr J. 2016;63:691–702. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ15-0747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shin NR, Bose S, Wang JH, Ansari A, Lim SK, Chin YW, Choi HS, Kim H. Flos lonicera combined with metformin ameliorates hepatosteatosis and glucose intolerance in association with gut microbiota modulation. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2271. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kishida Y, Okubo H, Ohno H, Oki K, Yoneda M. Effect of miglitol on the suppression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis development and improvement of the gut environment in a rodent model. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:1180–1191. doi: 10.1007/s00535-017-1331-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhang X, Zhao Y, Xu J, Xue Z, Zhang M, Pang X, Zhang X, Zhao L. Modulation of gut microbiota by berberine and metformin during the treatment of high-fat diet-induced obesity in rats. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14405. doi: 10.1038/srep14405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bai J, Zhu Y, Dong Y. Response of gut microbiota and inflammatory status to bitter melon (Momordica charantia L.) in high fat diet induced obese rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;194:717–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wang L, Li P, Tang Z, Yan X, Feng B. Structural modulation of the gut microbiota and the relationship with body weight: Compared evaluation of liraglutide and saxagliptin treatment. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33251. doi: 10.1038/srep33251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yan X, Feng B, Li P, Tang Z, Wang L. Microflora disturbance during progression of glucose intolerance and effect of sitagliptin: An animal study. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:2093171. doi: 10.1155/2016/2093171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wu H, Esteve E, Tremaroli V, Khan MT, Caesar R, Mannerås-Holm L, Ståhlman M, Olsson LM, Serino M, Planas-Fèlix M, et al. Metformin alters the gut microbiome of individuals with treatment-naive type 2 diabetes, contributing to the therapeutic effects of the drug. Nat Med. 2017;23:850–858. doi: 10.1038/nm.4345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.de la Cuesta-Zuluaga J, Mueller NT, Corrales-Agudelo V, Velásquez-Mejía EP, Carmona JA, Abad JM, Escobar JS. Metformin is associated with higher relative abundance of mucin-degrading akkermansia muciniphila and several short-chain fatty acid-producing microbiota in the gut. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:54–62. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Forslund K, Hildebrand F, Nielsen T, Falony G, Le Chatelier E, Sunagawa S, Prifti E, Vieira-Silva S, Gudmundsdottir V, Pedersen HK, et al. Disentangling type 2 diabetes and metformin treatment signatures in the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2015;528:262–266. doi: 10.1038/nature15766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhang X, Fang Z, Zhang C, Xia H, Jie Z, Han X, Chen Y, Ji L. Effects of acarbose on the gut microbiota of prediabetic patients: A randomized, double-blind, controlled crossover trial. Diabetes Ther. 2017;8:293–307. doi: 10.1007/s13300-017-0226-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.