Statement of the problem

Chronic pain is an enormous public health issue with up to 30% of adults in Western countries having chronic pain.1 Unfortunately, 79% of patients with chronic pain are dissatisfied with their pain care.2 Healthcare communities may struggle with providing ethical treatment in the context of the opioid crisis first observed in the USA and now seen across Europe, Canada, and Australia.3 In contrast, inequalities in the global under-treatment of pain have been documented across the developing world, leading to decreased quality of life and poor economic consequences.4 Furthermore, worldwide, sustainable healthcare models, regardless of payer type or insurance status, have not been identified for the ethical treatment of persons with chronic pain.5 A cultural transformation in the way that we treat people with chronic pain should include them having equal access to pain management without consideration of public vs private provision of healthcare. Patients should have access to the most current evidence-based care by experienced pain clinicians, if required, rather than having treatment directed by managed care companies, public policies, and policy makers, and without judgement from the media, co-workers, family, and friends.

A central value of medicine is to ameliorate suffering in patients through the principles of non-maleficence, beneficence, justice, and respect for patient autonomy.6 Most patients with chronic pain believe that they have the inalienable right to have their suffering adequately controlled through relief of their pains.7 Even though some authors have argued that pains can be alleviated using modalities that are readily available,8 most pain clinicians recognise that chronic pain is challenging to treat even under the best of circumstances. As pain clinicians we have a moral duty to speak frankly about ethical dilemmas, so as not to contribute to patient suffering or public health problems. Mindful awareness of the shared ethical practices of caring for persons with chronic pain should inform our core ethical values as healthcare providers.

Database searches (PubMed, PsychINFO, EMBASE, and SCOPUS) using the terms ‘chronic pain and ethics’, ‘ethical decision-making and chronic pain’, ‘shared decision-making and chronic pain’, and ‘bioethics and chronic pain’ identified only two recent books on ethical dilemmas exclusively faced in pain management. These were Ethical Issues in Chronic Pain Management by Michael E. Schatman9 and The Bioethics of Pain Management: Beyond Opioids by Daniel S. Goldberg.8 This limited literature on pain bioethics reflects the complexity of treating persons with chronic pain and offers little guidance to individual healthcare providers or members of interprofessional teams. A robust conversation is needed, about pain ethics in general and, more specifically, use of pain-related shared decision-making (SDM). Kaldjian's framework10, 11, 12 for SDM is recommended because it incorporates the ethical principle of respect for patient autonomy within patient-centred care.

Pain, suffering, and ethics

Each person's pain is very real and deeply personal.13 Pain is fundamental to life, a life without pain is not conducive to human flourishing.2 Patients often struggle with the overwhelming nature of pain impacting most valued life domains, including work, family, spirituality, and recreation. Chronic pain leads to a decline in quality of life resulting in dysfunction that may be described as human suffering. Pain symptoms are frequently associated with suffering, but suffering is not confined to the experience of pain. No direct correlation has been identified with the amount of pain and the amount of suffering.

Healthcare disciplines are held to high standards of ethical practice through codes of conduct. Ethics is the study of moral duties including the principles and values of conduct of individuals or groups.14 Clinical ethics is the application of ethical principles, guidelines, and theories to clinical situations and settings.15 Clinical ethical guidelines are shared among individuals within each healthcare discipline. Commonly, ethical clinical guidelines mandate that treatment decisions be in the best interest of each patient, reminding us that we are expected to place the good of the patient over benefits for the healthcare provider.16 Pain ethics are a specific subset of clinical ethics applicable to all healthcare professionals as equal partners. Pain ethical guidelines should become the standard of practice for both individual clinicians and multidisciplinary teams.

Shared decision-making

Respect for patient autonomy is the foundation of ethical decision-making for most healthcare disciplines. SDM explicitly considers patient autonomy when choosing treatment. According to Légaré and colleagues,17 both partners (i.e. the patient and the healthcare professional) need the best scientific evidence to explore within the context of the patient's values, goals, expectations, and the clinician's recommendations. The provider is responsible for providing unbiased access to the scientific evidence void of jargon and in keeping with the patient's health. Patient responsibilities include identifying personal values and adhering to the treatment plans. Patients are also responsible for the health choices that are made before and after treatment. Giordano18 notes that with SDM ‘perhaps the best that can be expected is that the patient assumes responsibility for their values, goals, intentions, and co-participatory role in the medical relationship’.

Pain research exploring SDM is limited. In 2014, Jones and colleagues19 reported that SDM was challenging and few healthcare providers were consistently engaging patients with back pain in SDM. Wiering and colleagues20 observed physiotherapists in the UK and found that SDM was underutilised by 76% of physiotherapists studied. They also found that, even when treatment expectations are not discussed, patients continue to form expectations regarding possible treatment outcomes. A study by van den Beukel and colleagues21 indicated that 80% of patients who participated in SDM showed improvement in chronic abdominal adhesion pain whether they elected to undergo surgery or declined the surgical option.

Kaldjian's framework for Shared decision-making

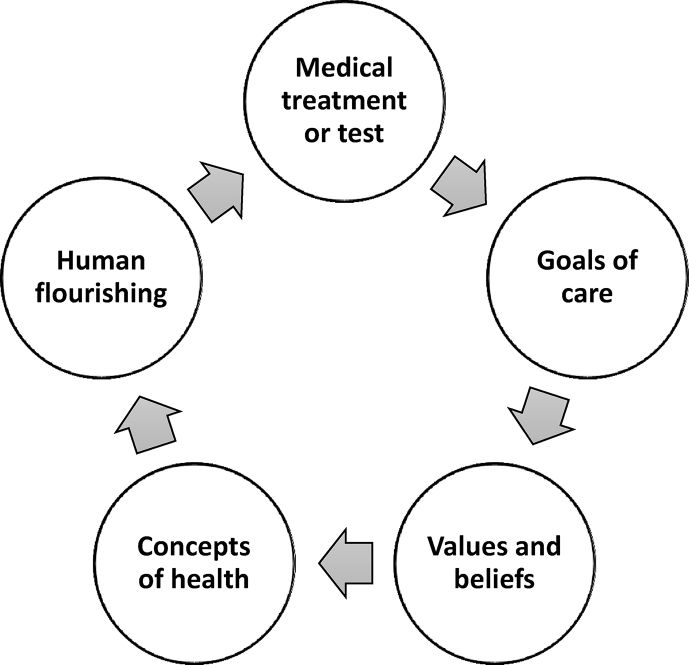

SDM studies described above examined components of SDM without presenting a theoretical model for understanding SDM across medical settings, healthcare disciplines, patient populations, variable cultural diversity, public vs private payer status, and social demands. Kaldjian10, 11, 12 summarises SDM as purpose-oriented dialogue that permits patients and healthcare providers to have forthright conversations about medical facts alongside beliefs and values that hold meaning for the individual patient. Shared healthcare decisions benefit from intentionally working toward specific ends or goals. Goals connect treatments and tests to the patient's ideal goal of human flourishing. This framework also allows clinicians to foster the development of healthy behaviours, self-care regimens, and active coping strategies.

Fig. 1.

Kaldjian's shared decision-making landscape.

SDM can be taught and learned while students are engaged in professional training. Educators and mentors are expected to model ethical SDM while providing treatment to patients. Implementation of the SDM framework should enhance a team's ability to provide cohesive ethical treatment for each patient in keeping with the goals of care, collective ethics, practice-based conscientiousness, social commitments, and the diversity of spiritual beliefs. Goals of care conversations may also contribute to developing the therapeutic alliance that is fundamental to the treatment of persons with chronic pain. The five core elements of SDM include:

-

1.

Medical treatments and tests: decisions about which treatments and tests to recommend are based upon patient specific goals of care. Rather than offering all patients the same tests and procedures, decisions about interventions should include consideration of the patient's personal values and beliefs. Persons having chronic pain are likely to have become familiar with some of the tests and procedures that aid in the diagnosis or treatment of pain. It would not be uncommon for the patient with low back pain to have repeat MRIs looking for changes within the spine. However, findings on MRIs are not directly correlated with having or not having pain.22 The clinician could reject the patient's request which diminishes respect for patient autonomy. Or the clinician could explore the patient's beliefs, values, and interpretation that are embodied in the request for another MRI. If the patient's goal is to be able to go hiking this summer, would another MRI aid in that valued life goal? Or would physical therapy be more in keeping with the stated goal? In the end, the purpose of linking treatment decisions to the patient's goal is to find the best fit between the available treatment resources and the patient's actual need for those resources.

-

2.

Goals of care: respect for patient autonomy helps to prioritise goals of care with each patient and, if desired, the patient's loved ones. Selecting goals of care is dependent upon having insight into the patient's target goal or end, which is usually a patient's preferred form of human flourishing. Pain relief is often identified as a valuable goal or end for patients with chronic pain. Improved quality of life, gaining an understanding of what is causing the pain, returning to work, and finishing one's education are typical goals of care identified when people have chronic pain. Once goals of care are identified, SDM can be implemented to discuss which treatments will be most effective in achieving the targeted goal. For a person with chronic pain who wants to understand more about what's causing the pain, additional tests and imaging may be offered; however, for the person with chronic pain who wants to return to work, pain psychology may be helpful as behavioural pacing is helpful for building endurance.

-

3.

Personal values and beliefs: these constructs are markers for what is important to the patient (e.g. persons, activities, and intentions that hold the deepest meaning). Because these constructs represent core features, patients may readily articulate them during the medical appointment. Healthcare decisions should highlight these enduring beliefs and values. Values and beliefs cannot be separated from goals of care without diminishing the relationship between the patient and the healthcare provider. Acceptance of discomfort may be warranted if the discomfort is in service of living a valued life. Different treatments for persons with different values and goals can increase patient satisfaction while increasing the likelihood that the treatment will be successful.

-

4.

Concepts of health: health literacy and beliefs vary based upon culturally-determined expectations and experiences. Thus, health means different things to each person (e.g. returning to horseback riding or being able to work to feed a family in the context of chronic pain). Within the SDM model, health is dependent upon physical functioning, psychosocial dimensions (i.e. emotional, spiritual, and social features), capacity to make independent decisions, and demonstrating the ability to engage in health behaviours. Understanding the patient's view of health may also inform the patient's willingness to accept side-effects of treatments or a less than 100% recovery.10, 11, 12 Concepts of health may change over time; therefore, health perceptions should be re-evaluated as diseases progress, burdens of suffering increase, or quality of life improves. This model allows providers and patients to continuously revisit the goals of care to determine whether the treatments and treatment plans are having the desired impact on the patient's valued outcomes and quality of life.

-

5.

Human flourishing: positive physical and emotional aspects of well-being are linked to human flourishing.19 One can only imagine the difficulty of aspiring to flourishing while suffering from chronic pain. For persons with chronic pain, suffering may be ameliorated through post-traumatic growth, resiliency, response shift, reorientation to personal values, and making meaning out of the experience. Patients and healthcare providers may find that holding different beliefs in what constitutes flourishing can lead to disagreements that may be resolved by co-examining the principles of respect for autonomy and beneficence.4 Kaldjian's iterative model of purpose-oriented SDM10, 11, 12 illuminates a vision of flourishing while also promoting acceptance of chronic pain. Biomedical tests, facts, and knowledge are not sufficient for a patient to move toward flourishing in the context of chronic pain.4 However, when goals, values, convictions, and priorities are identified, together patient and healthcare provider can determine which goals could be worth achieving and which burdens might be worth bearing.11

Conclusions

Kaldjian's framework10, 11, 12 for SDM provides a structured approach for investigating the complex ethical dilemmas experienced when treating patients with chronic pain. It offers insights into making difficult treatment decisions with persons who have chronic pain rather than for them. This framework is steeped in ethical principles that have guided patient care since the inception of medicine. The strength of this model results from developing goals of care which hold meaning for both the person with pain and the healthcare provider. By sharing the decisions with our patients, we are more likely to develop a therapeutic alliance where both parties are invested in the identified goals of care.

Pain clinicians have a moral duty to resolve pain ethical dilemmas thoughtfully to bring about reduced suffering and enhanced human flourishing in collaboration with patients. This duty includes providing adequate training for all levels of healthcare trainees. Public policy should reflect our professional values of offering just, safe, and compassionate care to our patients. Persons with chronic pain should have the inalienable right to healthcare systems that are respectful of dignity. Research agendas should focus on the ethical dilemmas associated with the treatment of persons with chronic pains. Use of structured approaches, such as Kaldjian's framework10, 11, 12 for SDM, provide the scaffolding necessary to focus our research questions, aid in the development of meaningful research goals, and allow us to develop predictive models for ethical behaviours.

Truly we are at a critical time for defining pain ethics. We have both the opportunity and the ethical mandate to create a cultural transformation in the treatment of chronic pain and suffering in our patients. To quote William Penn, ‘Right is right, even if everyone is against it, and wrong is wrong, even if everyone is for it.’ Mindful awareness of the ethical practices for treating persons with chronic pain will enhance human flourishing and mitigate suffering. Values of patients and values of pain clinicians are more alike than they are different. As clinicians and scholars, we should use our knowledge of right and wrong to create a universal pain ethic based upon mutual values, principles, virtues, and actions for the good of our patients.

Declaration of interest

The author declares that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dansie E.J., Turk D.C. Assessment of patients with chronic pain. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:19–25. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geurts J.W., Willems P.C., Lockwood C., van Kleef M., Kleijnen J., Dirksen C. Patient expectations for management of chronic non-cancer pain: a systematic review. Health Expect. 2017;20:1201–1217. doi: 10.1111/hex.12527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yan E.G., Kuo D.J. I just need an opiate refill to get me through this weekend. J Med Ethics. 2019;4:219–224. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2018-105099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King N.B., Fraser V. Untreated pain, narcotics regulation, and global health ideologies. PLOS Med. 2013;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurwitz E.L., Randhawa K., Torre P. The global spine care initiative: a systematic review of community-based burden of spinal disorders in rural populations and in low- and middle-income communities. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(Suppl 6):776–785. doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-5393-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassell E.J. Oxford University Press; New York: 2004. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brennan F., Carr D.B., Cousins M. Pain management: a fundamental human right. Pain Med. 2007;105:205–221. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000268145.52345.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg D.S. Taylor & Francis; New York: 2014. The bioethics of pain management: beyond opioids. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schatman M.E., editor. Ethical issues in chronic pain management. Informa Healthcare; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaldjian L.C. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2014. Practicing medicine and ethics: integrating wisdom, conscience, and goals of care. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaldjian L.C. Concepts of health, ethics, and shared decision making. Commun Med. 2017;14:83–95. doi: 10.1558/cam.32845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaldjian L.C. In support of goals-of-care discussions in shared decision making – an extended response to the rejoinders. Commun Med. 2017;143:287–298. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pellegrino E.D. A clinical ethics of chronic pain management: basis, reason, and responsibilities. In: Giordano J., editor. Maldynia: multidisciplinary perspectives on the illness of chronic pain. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2010. pp. 213–219. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark P.G., Cott C., Drinka T.J. Theory and practice in interprofessional ethics: a framework for understanding ethical issues in health care teams. J Interprof Care. 2007;216:591–603. doi: 10.1080/13561820701653227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor R.M. Ethical principles and concepts in medicine. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;118:1–9. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53501-6.00001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engel J., Prentice D. The ethics of interprofessional collaboration. Nurs Ethics. 2013;20:426–435. doi: 10.1177/0969733012468466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Légaré F., Turcotte S., Stacey D., Ratté S., Kryworuchko J., Graham I.D. Patients’ perceptions of sharing in decisions: a systematic review of interventions to enhance shared decision making in routine clinical practice. Patient. 2012;5:1–19. doi: 10.2165/11592180-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giordano J. Changing the practice of pain medicine writ large and small through identifying problems and establishing goals. Pain Physician. 2006;9:283–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones L.E., Roberts L.C., Little P.S., Mullee M.A., Cleland J.A., Cooper C. Shared decision-making in back pain consultations: an illusion or reality? Eur Spine J. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00586-014-3187-0. S13–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiering B., de Boer D., Krol M., Wieberneit-Tolman H., Delnoij D. Entertaining accurate treatment expectations while suffering from chronic pain: an exploration of treatment expectations and the relationship with patient-provider communication. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:706–715. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3497-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van den Beukel B.A.W., Stommel M.W.J., van Leuven S. A shared decision approach to chronic abdominal pain based on Cine-MRI: a prospective cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:1229–1237. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nanapragasam A., Lim C.K., Maskell G. Patient involvement and shared decision-making in the management of back pain: a proposed multidisciplinary team mode. Clin Radiol. 2019;74:76–77. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2018.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]