Abstract

Background

Food poisoning outbreaks are commonly seen in mass social events where food is prepared under temporary arrangements. This study reports a food poisoning outbreak in a city of western Maharashtra, India, where around 4000 people had consumed food during a religious community lunch and reported sick to the nearby hospital with complaints of diarrhea, abdominal cramps, fever with chills, and vomiting.

Methods

This was a retrospective–prospective study. Investigation of the food poisoning outbreak was conducted to identify the causes and recommend preventive measures. Interview method was used to elicit food history from the affected and non-affected persons. Inspection of the cooking area was conducted to find the likely source of contamination.

Results

A total of 291 patients reported sick after consumption of meal at a religious mass gathering. The range of incubation period was from 10 hours to 40 hours. Predominant features were diarrhea (100%), abdominal cramps (89%), fever with chills (81%), and vomiting (28.5%). Maximum relative risk of 14.89 was seen for green gram (moong dal) with 95% confidence interval of 2.16–102.6. Keeping the incubation period and clinical profile in view, the likely organisms are enteropathogenic Escherichia coli or Salmonella spp.

Conclusion

Maintaining food safety during mass gatherings is a major challenge for public health authorities. The Food Safety and Standards Act (2006) in India brings the food consumed during religious gatherings such as 'prasad' and 'langar' under its purview and comprehensively addresses this issue.

Keywords: Food poisoning, Food handling, Disease outbreak, Food contamination, Epidemiology

The food you eat can be either the safest and powerful form of medicine or the slowest form of poison.

Ann Wigmore

Introduction

Food-borne transmission of pathogenic and toxigenic microorganisms has been a recognized hazard for decades.1 Under the Integrated Disease Surveillance Project (IDSP) in India, food poisoning outbreaks are reported from all over the country.2 Out of the total outbreaks reported to the IDSP, approximately 60% are related to food-borne infections.3 Causes of food-borne illness include bacteria, parasites, viruses, toxins, metals, and prions.4 The symptoms can range from mild and self-limiting vomiting and diarrhea to severe and life-threatening neurological conditions.

Food poisoning is common in settings where meals are prepared for large gatherings such as banquets, messes, religious occasions, and weddings. In Armed Forces also, owing to community kitchen practice, a number of outbreaks involving a varying number of personnel are reported every year.5 After viral hepatitis, food poisoning is the second most common cause of disease outbreaks in the Indian Army.6 Besides being a cause of concern for Unit Commanders and an added burden on health-care facilities, the outbreak points to the existence of conditions that led to such an event.7 Religious community gatherings where food is provided have existed ever since early human communities celebrated important events—much before government regulations on food safety were formalized.8 Safeguarding public health during mass gatherings is a big challenge. The important characteristics of such mass feeding occasions is that certain temporary arrangements are set up for cooking and serving food. In these provisional kitchens, food safety measures from farm to fork are difficult to implement and can lead to occurrence of food poisoning outbreaks. In India, the felt need for a food safety law has been met by promulgation of Food Safety and Standards Act (FSSA) 2006, which applies to all eating establishments, messes, canteens, hospital kitchens, and religious places, where mass feeding takes place.9

In the present study, a food poisoning outbreak was reported from a city in western Maharashtra, India, where a large gathering of around 4000 men, women, and children had consumed lunch in a community kitchen on the occasion of a religious event.

Material and methods

A retrospective–prospective study design was used for the investigation of the outbreak.10 The investigation was carried out using an epidemiological case sheet for each case, based on a standardized questionnaire using one-to-one interview method after obtaining consent of the individual. The questionnaire consisted of personal particulars of the affected (cases) and non-affected (contacts) people, their food history of last 72 h, date and time of onset of symptoms, type and severity of symptoms, and treatment history. Out of the 291 affected persons (cases), 84 could be traced and were interviewed, and 100 non-affected persons (controls) were interviewed. Details about procurement of raw material, transport, storage, cooking, and serving of food were also compiled. Attack rates (ARs) and relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated to identify the incriminating food item. Based on the symptoms and range of incubation period, the likely organisms were identified. Food samples were not available, but stool samples of admitted patients were sent for culture. Inspection of food preparation premises was carried out to find the likely source of contamination.

Epidemiological study

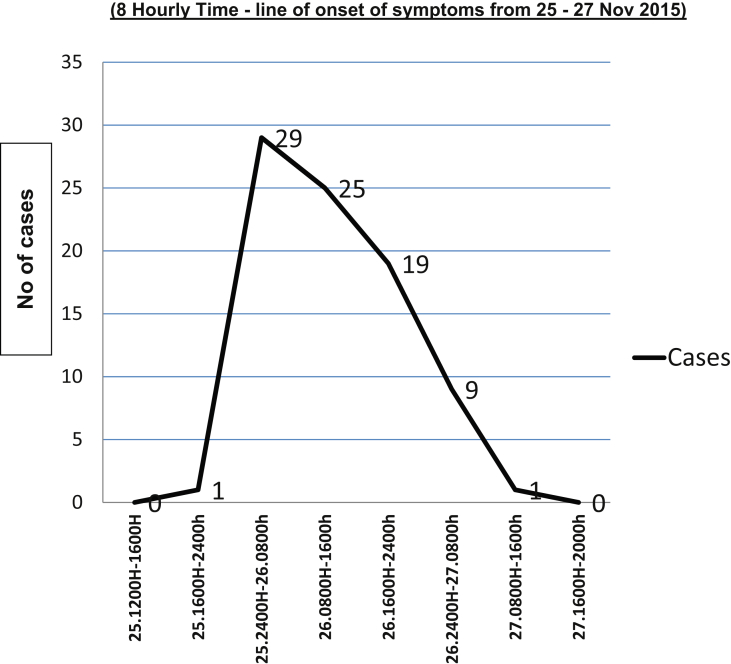

The steps for investigation of a food poisoning outbreak were followed. The first step of verification of diagnosis of food poisoning was arrived at by history taking and clinical examination of the cases that reported to the hospital. The symptoms of diarrhea, abdominal cramps, fever, and vomiting in a large number of cases after consumption of common food at a mass gathering confirmed the diagnosis of food poisoning. The second step of confirmation of an outbreak of food poisoning was assessing the linkage of the cases by time, place, and person with a history of consumption of common food in a community gathering. The number of cases was clearly in excess of expected frequency for this population as was assessed by the weekly trends for last three years available with the local medical authorities. Fig. 1 shows the epidemic curve with a steep-up slope, a more gradual down slope, with a width approximating the average incubation period of the pathogen. This indicates a point source outbreak,11 classically seen in a food poisoning outbreak.

Fig. 1.

Epidemic curve of onset of symptoms in 84 cases interviewed during investigation of food poisoning outbreak (8 hourly time—line of onset of symptoms from 25–27 Nov 2015).

The third step was defining the population at risk. All the people who consumed food at the community gathering on 25 November 2015 were considered as the population at risk. A probable case definition was formed and included any person who reported with gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal cramps, diarrhea, or vomiting) with or without fever, after consuming food during the community lunch.

Rapid search for cases was carried out in the community, and detailed history was taken from admitted patients, treating physicians, and cases in the community. The index case had onset of symptoms at around 2330 h on day 1 and reported to the hospital at 1100 h on day 2 with complaints of diarrhea, abdominal cramps, fever, and vomiting. The last case reported on day 3.

Results

Data analysis

A total of 291 patients reported to the hospital, out of which 120 (41%) were adult males and 171 (59%) were women and children. The predominant features among the 84 cases interviewed were diarrhea (100%), with the number of episodes ranging from 5 to 50, abdominal cramps (89%), fever (81%), and vomiting (28.5%). No case reported with blood or mucus in stools. Table 1 shows the percentage of cases with each symptom.

Table 1.

Frequency of symptoms among cases interviewed (n = 84).

| Signs and symptoms | No. of cases | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Diarrhea | 84 | 100.0 |

| Abdominal cramps | 75 | 89.3 |

| Fever | 68 | 80.9 |

| Fever with chills | 58 | 69.0 |

| Vomiting | 24 | 28.5 |

The time of onset of symptoms in the index case was at 2330 h on day 1, after consumption of lunch at 1330 h, and the last case reported to the hospital at 0800 h on day 3. The range of incubation period was from 10 h to 40 h. Median incubation period was 17 h.

The lunch menu comprised of green gram (moong dal), mixed vegetable curry, peas cottage cheese curry (matar paneer), rice, rice porridge (kheer), bread (chapati), and salad. The lunch started at 1230 h and continued up to 1530 h. Maximum cases that reported with food poisoning had consumed food during the second half of the lunch, between 1330 h and 1530 h. Persons who had consumed lunch early from 1230 h to 1330 h were largely not affected. The ARs were calculated for each food item. RR with 95% CI for each food item is shown in Table 2. The maximum RR of 14.89 was seen for green gram (moong dal), with 95% CI of 2.16–102.6.

Table 2.

Food-specific attack rates of subjectsa.

| Food items | Ate food item |

Did not eat food item |

AR % | RR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Ill | Attack rate (%) | Total | Ill | Attack rate (%) | |||

| Rice | 172 | 78 | 45.3 | 12 | 6 | 50.0 | −10.37 | 0.90 (0.50–1.6) |

| Salad | 168 | 78 | 46.4 | 16 | 6 | 37.5 | 19.18 | 1.24 (0.74–2.7) |

| Moong dal | 156 | 83 | 53.2 | 28 | 1 | 4.1 | 92.29 | 14.89 (2.16–02.6) |

| Kheer | 174 | 80 | 45.9 | 10 | 4 | 40 | 12.85 | 1.14 (0.52–2.4) |

| Matar paneer | 128 | 62 | 48.4 | 56 | 22 | 39.3 | 18.80 | 1.23 (0.85–1.78) |

| Mix Vegetables | 173 | 73 | 42.2 | 11 | 11 | 100 | −136.96 | 0.42 (0.35–0.50) |

| Chapati | 183 | 83 | 45.3 | 1 | 1 | 100 | −120.75 | 0.90 (0.22–3.6) |

| Water | 142 | 64 | 45.0 | 42 | 20 | 47.6 | −5.77 | 0.94 (0.65–1.3) |

AR, attack rate; CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

Affected n = 84; Not affected n = 100.

Causative organism

Keeping the incubation period and clinical profile in view, the likely organisms are Salmonella spp and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Stool samples from admitted patients were sent for culture, and reports showed growth of Escherichia coli but no growth of Salmonella, Shigella, and Vibrio group of organisms at 48 h and 72 h incubation period. Microscopic examination of stools showed 12–14 pus cells/high power field (HPF).

Source of infection

Contamination of food items can occur during cooking, storage, or distribution of food by the food handlers or in the vessels used during these processes. The food samples were not available for culture. The medical examination of food handlers and laboratory investigation of stool sample were conducted. There were no positive findings.

Environmental study

The food preparation for the community lunch started at 0600 h on day 1. Food was prepared and stored in large vessels for consumption throughout the day. The maximum temperature on day 1 at the study place was 35 °C. The food was cooked in an open space with no protection against flies, rats, and other animals. Cooked food was stored in large vessels and served to the people attending the lunch. There was a possibility of contamination of food items during the course of cooking or storage. In a study by Jadhav et al.,12 the circumstantial inquiry of the manner in which the chicken was handled through the various stages of storage and preparation afforded ample opportunity for growth of organisms.

Discussion

It is a common practice during religious festivals in our country to organize mass feeding in form of prasad, for which food is cooked on mass scale and served to the public. Preparation and storage of food under such makeshift arrangements is often unhygienic, leading to local outbreaks of food-borne infections.10 In the present study, a food poisoning outbreak occurred in a community kitchen where a large gathering had consumed a common meal. A study in South India by Prasad et al.13 reports an outbreak of food poisoning after a religious function in a rural setting where all patients had attended Sri Ram Navami function organized in a nearby temple and had ingested panakam (prasad). In another study report, Salmonella and its preformed toxins resulted in illness among 400 students from adjoining schools during celebration of Saraswati puja in a school in Kamrup district of Assam after consumption of khichri and prasad and presented with fever, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain.14

In our study, there was predominance of lower gastrointestinal tract symptoms such as diarrhea and abdominal cramps, which eliminates Staphylococcus enterotoxins as one of the likely contaminants. Absence of blood in stools reduces the possibility of Shigella and E. coli O157. Profuse diarrhea with rice water stools and severe dehydration, pathognomonic of Vibrio cholera, was also absent. Considering the incubation period of 10–40 h and symptoms of diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and fever, the likely organisms were Salmonella spp and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Another organism presenting with similar features is Campylobacter jejuni, but it has a longer incubation period of 1–10 days.

Out of all the items served, moong dal, although not typical of Salmonella food poisoning, was found to be the incriminated food. However, the same could not be confirmed on culture because the samples of food items were not available. Also, the stool samples of the patients did not show growth of Salmonella. Water samples from different sites were checked for residual chlorine and bacteriological examination and were found satisfactory. Availability of potable water both for drinking and cooking is an important factor for prevention of food-borne illnesses. As the food was prepared early in the morning and kept in the open for a long time, it is likely to have gotten contaminated during this time. Keeping food for prolonged periods of 6–8 h at a temperature range between 5°C and 60°C (danger zone)15 can lead to rapid microbial growth and contamination of food. In a study of food poisoning outbreak by Mustafa et al.,16 raita was prepared in the morning at 0800 h by mixing curd with cucumber procured from the local market and stored in a steel container at room temperature until midday, when it was served. Lack of proper storage or reheating facilities during interim arrangements in such large gatherings is a weak link in food safety chain. Such examples have been reported from developed countries such as the USA too where in July 2007, more than 600 visitors to an annual food festival called “Taste of Chicago” fell ill with Salmonella infection linked to a hummus dish sold by a Chicago restaurant.17

Recommendations

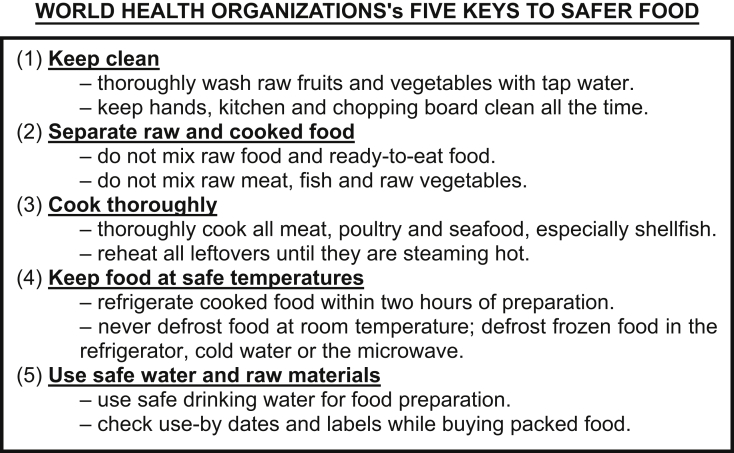

Prevention of food poisoning during mass gatherings involves stringent hygiene standards and safe surroundings while preparing food. Food warmers should be used to store the cooked food above 70°C to prevent growth of microorganisms. Consumption of uncooked foods such as salads, fruits, and raw milk should ideally be avoided. Food samples of food items prepared should be preserved for 72 h in deep freezers to aid in investigation in case of any food poisoning outbreaks. The World Health Organization's (WHO) Five Keys to Safer Food explains the basic principles that each individual should know all over the world to prevent food-borne diseases.18 These are summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

WHO Five Keys to Safer Food. WHO, World Health Organization.

Conclusion

Food is an integral part of all social events. Such events expose masses to risk of food-borne infections as the food is prepared under temporary arrangements. The application of WHO Five Keys to Safer Food can prevent such occurrences. The Food Safety and Standards Authority (FSSA) in India is a forward-looking act aimed at food safety at all levels. It brings the food consumed during religious gatherings such as ‘prasad’ and ‘langar’ under its purview and comprehensively addresses this issue.

The Armed Forces of our country have comprehensive documents on food safety in the form of Army, Air Force, and Navy Orders on “Prevention of Food and Water Borne Diseases” and “Food Poisoning”, which give detailed guidelines on these subjects. It is a challenge for public health authorities to ensure that these principles are followed so that food-borne illnesses can be prevented.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Egan M.B., Raats M.M., Grubb S.M. A review of food safety and food hygiene training studies in the commercial sector. Food Control. 2007;18:1180–1190. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Food-borne diseases. NCDC. CD Alert. 2009;13:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Focusing on food borne infections as an important cause of morbidity and mortality in India. NCDC Newsletter. 2013;2:4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newell D.G., Koopmans M., Verhoef L. Food-borne diseases—the challenges of 20 years ago still persist while new ones continue to emerge. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010 May 30;139(Suppl 1):S3–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.vol. 2. 2003. Directorate general armed Forces medical services. Food poisoning. New Delhi; pp. 640–647. (Manual of Health for the Armed Forces). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kushwaha A.S., Aggarwal S.K., Sharma L.R., Singh M., Nimonkar R. Accidental outbreak of non-bacterial food poisoning. Med J Armed Forces India. 2008;64:346–349. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(08)80018-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kunwar R., Singh H., Mangla V., Hiremath R. Outbreak investigation: Salmonella food poisoning. Med J Armed Forces India. 2013;69:388–391. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newslow D., Schmidt R.H., Rodrick G.E. Hazard analysis critical control point (HACCP) Food Safety Handbook. 2005 Mar 11:363–379. [Google Scholar]

- 9.FSSAI A. and rule . Akalank Publication PG; 2011. Akalank's Food Safety and Standards Act, Rule and Regulation; p. 293. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelsey J.I., Thompson W.D., Evans A.S. 1986. Case Control Studies. Methods in Observational Epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flint J.A., Van Duynhoven Y.T., Angulo F.J. Estimating the burden of acute gastroenteritis, foodborne disease, and pathogens commonly transmitted by food: an international review. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:698–704. doi: 10.1086/432064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jadhav S.L., Sinha A.K., Banerjee A., Chawla P.S. An outbreak of food poisoning in a military establishment. Med J Armed Forces India. 2007;63:130–133. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(07)80055-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prasad V.G., Malhotra M.V., Yadav K., Nagaraj K. Epidemiological investigation of an outbreak of food poisoning at a religious gathering in South India. Indian J Appl Res. 2015 May 5;5:50–53. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma J., Malakar M., Gupta S., Dhandar A.R. Food Poisoning: a cause for anxiety in Lakhimpur district of Assam. Ann Biol Res. 2014;5:46–49. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCabe-Sellers B.J., Beattie S.E. Food safety: emerging trends in foodborne illness surveillance and prevention. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004 Nov 30;104:1708–1717. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mustafa M.S., Jain S., Agarwal V.K. Food poisoning outbreak in a military establishment. Med J Armed Forces India. 2009;65:240–243. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(09)80013-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abubakar I., Gautret P., Brunette G.W. Global perspectives for prevention of infectious diseases associated with mass gatherings. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012 Jan;12:66–74. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burden of Foodborne Diseases in the South-East Asia Region. WHO; 2016. [Google Scholar]