Abstract

This article comments on:

Larissa Chacon Dória, Cynthia Meijs, Diego Sotto Podadera, Marcelino del Arco, Erik Smets, Sylvain Delzon and Frederic Lens. 2018. Embolism resistance in stems of herbaceous Brassicaceae and Asteraceae is linked to differences in woodiness and precipitation. Annals of Botany 124(1): 1–14.

The challenge of understanding how plants adapt to dry environments has fascinated and frustrated scientists for hundreds of years. Major advances towards answering this challenge have been made recently with the identification of water transport physiology as a primary determinant of mortality and adaptation of trees to water availability (Choat et al., 2018). One limitation, however, is that much of this formative work has focused on woody species, which is one reason why a study by Dória et al. in this issue of AoB is of particular importance. In their paper, the authors capitalize on the mysterious preponderance of evolutionary transitions from herbaceous to woody forms in island habitats, to examine the implications of woodiness in terms of the resilience of the water transport system. From the idyllic workshop of the Canary Islands the authors illustrate strong correlations between woodiness, xylem vulnerability to dysfunction, and species distribution. These observations have broad implications in terms of the classical theory of drought avoidance and tolerance in plant species.

It is generally considered that plants can adapt to dry environments either by avoiding stress through rapid growth and maturation that enables them to complete their reproductive cycle before the onset of water deficit, or by tolerating periods of water deficit through tissue hardiness (Ludlow, 1989). Although this qualitative framework has been useful in understanding diversity in adaptation to dry environments, it does not provide any quantitative power in terms of predicting the functional properties of plant species along environmental gradients. Progress towards a more predictive model of species distribution along rainfall gradients has been catalysed by evidence of a strong connection between the sensitivity of the xylem water transport pipeline to cavitation under water stress, and plant mortality during water shortage (Brodribb and Cochard, 2009). Within woody plants this linkage underpins strong correlations between species vulnerability to xylem cavitation under water stress and native distribution (Brodribb and Hill, 1999, Larter et al., 2017, Blackman et al., 2010). One might expect therefore, that patterns of evolution in xylem vulnerability should provide new insights into the adaptive pathways leading drought-resilient or drought-avoiding species to evolve during radiations into dry environments.

The evolution of resilient xylem has been studied extensively in woody plants and appears to be associated with increased mechanical investment in the water transport system. This was originally proposed in a seminal paper (Hacke et al., 2001) where it was hypothesised that the increasing buckling stresses associated with housing a water column under high tension (caused by water deficit) should lead to a relationship between wood density and vulnerability to cavitation. Subsequently this qualitiative relationship has been refined, identifying the specific cell wall and membrane properties that resist air being dragged into the xylem causing cavitation and blockage of the pipeline (Jansen et al., 2009). However, the paper by Dória et al. in this issue throws an interesting new perspective on the evolution of resilience, suggesting an important role of stem lignification during adaptation to dry soils. The species used in this study are all secondarily woody plants, meaning that their colonizing ancestors in the Canary Islands were herbaceous (Böhle et al., 1996). The absence of large herbivores and selection for outbreeding has apparently led to the interesting scenario where woodiness has been favoured over herbaceousness during the evolution of the Canary Islands flora. This creates an ideal environment to examine the de novo evolution of drought resistance, because unlike other study systems such as conifers which have woody ancestors, the ancestral state in the Canary Island system is herbaceous. The interesting finding by Dória et al. is that the amount of lignified tissue in the stem, rather than specific reinforcement of the xylem vessel membranes or walls, explains most of the variation in xylem resilience. This correlation, although intuitively sensible in the sense that the more robust stems are more resistant to cavitation, is hard to explain in terms of mechanism. Clearly we still have some work to do to understand the exact process that provokes cavitation during stress, and the ways that plants go about modifying their structure to resist cavitation.

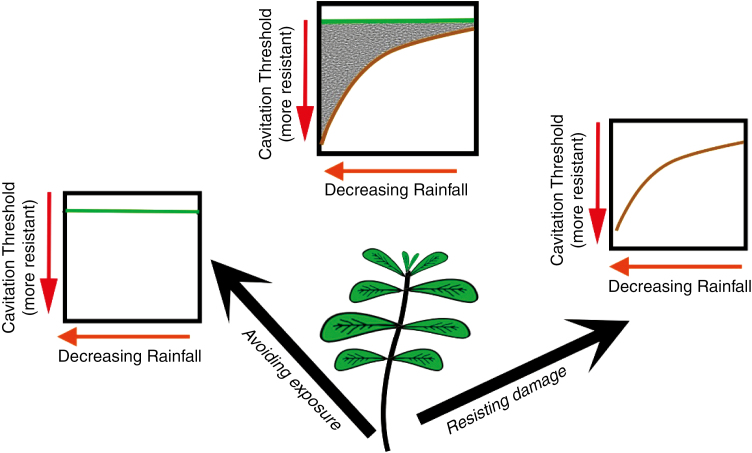

There remains much to discover in regard to the physiological capacity of plants to evolve increased drought resilience. In particular the hydraulic behaviour of plants categorized as ‘avoiding’ or ‘escaping’ drought remains largely unknown. This is a significant knowledge gap because all the species upon which we depend for grain and forage production fall into this ecological class. It is likely that a strategic spectrum exists between the ecological extremes of resisting damage during water deficit and avoiding exposure to water deficit (Fig. 1). For example, grasses could all be considered ‘drought evasive’ when viewed relative to conifers, yet within grasses there exists a spectrum of drought tolerance that is associated with xylem vulnerability (Volaire et al., 2018). Movement beyond nominal ecological division of plant strategies and towards a quantitative drought resistance framework built around meaningful traits is needed to understand the physiological prerequisites and evolutionary pathways leading to success in dry environments.

Fig. 1.

Two contrasting hydraulic strategies can confer success in dry environments. Best understood is evolution to resist damage to the hydraulic system, leading to a cavitation threshold that occurs at a lower (drier) water potential (brown line in right plot). Alternatively, plants can avoid water stress by only being metabolically active during wet events, meaning that there would be no relationship between xylem vulnerability to cavitation and water availability (green line, left plot). In reality, there seems to exist a spectrum of responses (centre graph),suggesting that adiversity of hydraulic ‘strategies’ can co-exist.

Literature cited

- Blackman CJ, Brodribb TJ, Jordan GJ. 2010. Leaf hydraulic vulnerability is related to conduit dimensions and drought resistance across a diverse range of woody angiosperms. New Phytologist, 188: 1113–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhle U-R, Hilger HH, Martin WF. 1996. Island colonization and evolution of the insular woody habit in Echium L. (Boraginaceae). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 93: 11740–11745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodribb TJ, Cochard H. 2009. Hydraulic failure defines the recovery and point of death in water-stressed conifers. Plant Physiology, 149: 575–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodribb TJ, Hill RS. 1999. The importance of xylem constraints in the distribution of conifer species. New Phytologist, 143: 365–372. [Google Scholar]

- Choat B, Brodribb TJ, Brodersen CR, Duursma RA, López R, Medlyn BE. 2018. Triggers of tree mortality under drought. Nature, 558: 531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dória LC, Meijs C, Podadera DS, Del Arco M, Smets E, Delzon S, Lens F. 2018. Embolism resistance in stems of herbaceous Brassicaceae and Asteraceae is linked to differences in woodiness and precipitation. Annals of Botany, 124: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacke U, Sperry JS, Pockman WT, Davis SD, McCulloch A. 2001. Trends in wood density and structure are linked to the prevention of xylem implosion by negative pressure. Oecologia, 126: 457–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen S, Choat B, Pletsers A. 2009. Morphological variation of intervessel pit membranes and implications to xylem function in angiosperms. American Journal of Botany, 96: 409–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larter M, Pfautsch S, Domec JC, Trueba S, Nagalingum N, Delzon S. 2017. Aridity drove the evolution of extreme embolism resistance and the radiation of conifer genus Callitris. New Phytologist, 215: 97–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow M. 1989. Strategies of response to water stress. In: Kreeb KH, Richter H, Hinckley TM eds. Structural and functional responses to environmental stresses: water shortage. The Hague: SPB Academic Publishing BV, 269–281. [Google Scholar]

- Volaire F, Lens F, Cochard H, Xu H, Chacon-Doria L, Bristiel P, Balachowski J, Rowe N, Violle C, Picon-Cochard C. 2018. Embolism and mechanical resistances play a key role in dehydration tolerance of a perennial grass Dactylis glomerata L. Annals of Botany, 122: 325–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]