Abstract

Cancer is one of the leading causes of mortality in China, and poses a threat to public health due to its increasing incidence and mortality rates. Concurrent cancer is defined as one or more organs in the same individual having ≥2 primary malignancies occurring simultaneously or successively; however, concurrent cases are rare and poorly studied. The present study recruited a Chinese family presenting multiple cases of concurrent cancer and performed whole exome sequencing in one unaffected and two affected individuals to identify the causative mutations. DNA was extracted from peripheral blood and tumor tissue samples. Following an exome capture and quality test, the qualified library was sequenced as 100 bp paired-end reads on an Ion Torrent platform. Clean data were obtained by filtering out the low-quality reads. Subsequently, bioinformatics analyses were performed using the clean data. After mapping and annotating in 1000 Genomes Project database, the existing SNP database and the Cancer Gene Census (CGC) database, it was revealed that the NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase core subunit S7 gene was a candidate gene with somatic mutations, and a subset of 16 genes were candidate genes with germline mutations. The findings of the present study may improve the understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of concurrent cancer.

Keywords: whole exome sequencing, concurrent cancer, somatic mutations, NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase core subunit S7 gene, germline mutations

Introduction

Cancer is a disease that poses a threat to human health worldwide, and it has become a major public health concern in China (1,2). Typically, cancer can be caused by the accumulation of molecular alterations in genes that control cell survival, growth, proliferation and differentiation within the nascent tumor (3). Currently, the molecular profile of cancer can be effectively assessed using gene sequencing technologies and advanced analytical approaches (4). Advances in technology provide unprecedented speed and resolution to find causative mutations in the patient's genome that underlie cancer development and progression, ranging from point mutations to chromosomal translocations (4,5). In particular, there are somatic alterations that are unique to tumor cell genomes and specific inherited or ‘germline’ genomic alterations that are known to confer increased susceptibility to cancer development (4,5). Concurrent cancers are rare, and can increase the economic burden on a family and society. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the development and progression of concurrent cancers remain unclear.

Next generation sequencing (NGS), also known as high-throughput parallel sequencing technology, provides an unbiased way to examine the molecular pathogenesis of diseases and expands the impact of genomic analyses in biomedical research (6,7). Furthermore, NGS has been widely used in scientific research, and for the clinical diagnosis and treatment of cancer (8–11). The exome represents only ~2% of the human genome, but contains ~85% of known disease-associated variants, making whole exome sequencing (WES) a significant alternative to whole genome sequencing (WGS) (12,13). Compared with WGS, WES has significant advantages, including reduced costs, faster data analysis and easier data management (13). Therefore, investigating the molecular alterations in concurrent cancers using WES technology is a more cost-effective approach.

In the present study, WES technology was used to identify causative variants in a Chinese family in which two members were diagnosed with concurrent cancer. Following filtering of the raw data and exhaustive annotations, it was identified that NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase core subunit S7 (NDUFS7) was a candidate gene with somatic mutations (g.1391151G>A and g.1393289G>C), and a subset of 16 genes were candidate genes with germline alterations in patients with concurrent cancer. The results of the present study may improve the current understanding of the molecular mechanism of concurrent cancer and provide a basis for further studies.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

In the present study, patients with concurrent cancer were identified using the following criteria: i) Each tumor had confirmed evidence of malignancy; ii) each tumor was distinct; and iii) the probability that one tumor had metastasized from the other was excluded based on pathological and immunohistochemical analysis (14). The present study examined peripheral blood samples and tumor tissues from two patients with concurrent cancer in one family. Tumor tissues (>200 mg) were obtained during resection, placed in cryopreservation tubes and immediately placed in liquid nitrogen or −80°C freezer. A peripheral blood sample (5 ml) from an unaffected family member was also collected (Table I). All patients were recruited at the Second People's Hospital of Yichang (Hubei, China) between December 2014 and January 2017. The experiments were performed with the understanding of each patient, and all patients signed a written informed consent. The present study was performed in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association of The Declaration of Helsinki (15). The present study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Yichang Second People's Hospital, Three Gorges University.

Table I.

Sample information.

| Family member | Age, years | Sex | Sample ID | Sample type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| II-1 | 68 | Female | BT15061701HNDQ | Breast tumor tissue |

| BT15061702HNDQ | Rectal tumor tissue | |||

| BT15082203HNDE | Peripheral blood | |||

| II-5 | 61 | Male | BT15061703HNDQ | Liver tumor tissue |

| BT15061704HNDQ | Lymphoma tissue | |||

| BT15082201HNDE | Peripheral blood | |||

| II-3 | 63 | Male | BT15082202HNDE | Peripheral blood |

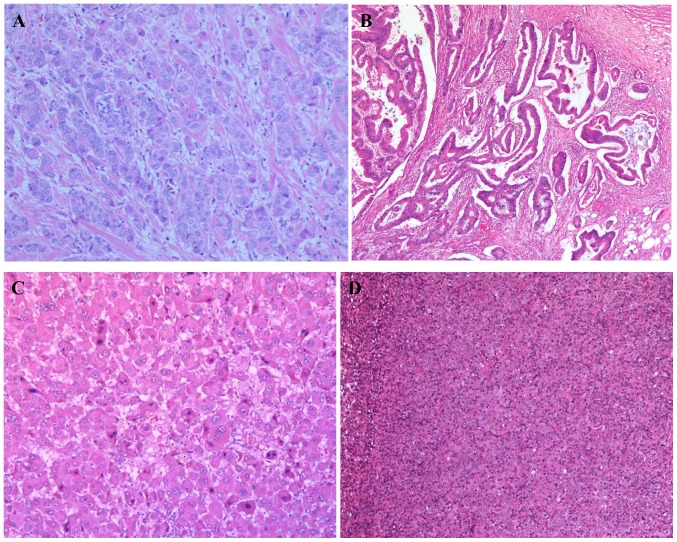

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of tumor tissues

Each tissue sample was fixed in 10% formaldehyde overnight at 4°C prior to embedding (FFPE) in paraffin. The FFPE tissue blocks were cut in 4 µm sections on a microtome at room temperature and then fixed onto standard glass histological slides. Each section was dewaxed in xylene, rehydrated through graded ethanol and underwent H&E staining at room temperature. Each section was incubated with hematoxylin for 5–10 min followed by eosin for 1 min. A coverslip was then added to each slide with Pertex mounting medium. The stained slides were scanned on an Olympus light microscope at magnifications of ×100 or ×200. All specimens were anonymized prior to receipt. All H&E stained sections were examined by two pathologists.

DNA extraction, library preparation and sequencing

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood and tumor tissue samples using a QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen GmbH) according to the manufacturer's protocol. To construct a library, we performed exome capture using an Agilent SureSelect Human All ExonV5 kit (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) following the manufacturer's protocol. A total of 0.5 µg DNA per sample was used as input material for the DNA library preparations. Genomic DNA samples were fragmented by sonication to a size of ~350 bp (duty factor 10%, peak incident power 175, cycles per burst 200, treatment time 180 sec, bath temperature 4–8°C). Next, DNA fragments were end polished, A-tailed and ligated with the full-length adapter for sequencing, followed by further polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification using KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (Roche Diagnostics). The primers were based on the P5 and P7 flow cell sequences, and were suitable for the amplification of libraries prepared with full-length adapters. The primer sequences were as follows: P5: 5′-AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATC-3′; P7: 5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGA-3′. Thermocycling conditions: Initial denaturation at 98°C for 45 sec, denaturation at 98°C for 15 sec, annealing at 60°C for 30 sec, extension at 72°C for 30 sec, library amplification with 3 cycles, a final extension at 72°C for 1 min and hold at 4°C. Subsequently, PCR products were purified by the AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter, Inc.), libraries were analyzed for size distribution by Agilent2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) and quantified by quantitative PCR (3 nM) using KAPA Library Quantification kits (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The primers were the same as for the amplification procedure. The thermocycling conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec and combined annealing/extension at 60°C for 45 sec. A total of 6 pre-diluted DNA standards and appropriately diluted NGS libraries were amplified at the same time. The average Cq value for each DNA standard was plotted against its known concentration to generate a standard curve. The standard curve was used to convert the average Cq values for diluted libraries to concentration, from which the working concentration of each library was calculated. After the quality test, the qualified library was sequenced as 100 bp paired-end reads on an Ion Torrent platform (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Bioinformatics analysis

Firstly, clean data were obtained following filtering of the low-quality reads, including reads with adapter sequences, reads with proportion of N >10% and reads with low-quality base numbers >5. The Burrows-Wheeler transform methods were adopted to map these reads to the human reference genome University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) hg19 (16,17). Subsequently, the Picard and Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK; version 3.2) methods were adopted for duplicate removal, local realignment and base quality recalibration, as previously described (18,19). Finally, the GATK Unified Genotyper software (version 3.0; Broad Institute) was used for SNV annotation. The value of QualByDepth (QD) describes the quality of variation per unit depth, and the higher the QD, the higher the reliability of the variation in general (20). QD >2.0 was set for ‘good’ SNV (FILTER=Pass), which could distinguish well between reliable and unreliable variations.

Variants were annotated using the ANNOVAR software tool (21). Annotations for function (exonic, intronic and untranslated region), reference genes, exonic function (synonymous, non-synonymous, stop-gain, frameshift and unknown), amino acid changes, 1,000 Genomes Project database (22), single nucleotide polymorphism database (dbsnp 138; ftp://ftp-trace.ncbi.nih.gov/snp/organisms/) and the Cancer Gene Census (CGC) database (23) were performed. Varscan2 (VarScan.v2.3.9; http://varscan.sourceforge.net/) (24) was used to identify somatic mutations in four paired tumor tissue and peripheral blood samples from the two patients with concurrent cancer.

WES generated a large volume of data, and several filtering criteria were applied to the dataset. Firstly, the sequencing quality score of a given base, Q, was defined by the following equation: Q=−10log10(e) where e was the estimated probability of the base call being wrong. A quality score of 20 represented an error rate of 1 in 100, with a corresponding call accuracy of 99%. Variants with a low-quality score (<20) were removed. Secondly, 1,000 Genomes Pilot Project database stores data from normal people. Minor allele frequency (MAF) is the percentage of alleles that are relatively rare in a population. Every variation at every location has a MAF value. MAF=1% is generally used as the boundary line for judging a correlation with disease, but the value is not absolute. Importantly, the threshold has to be analyzed in combination with the incidence of diseases. Concurrent cancers are rare; therefore, the variants with a reported MAF of >0.005 were filtered out. Then, synonymous changes were removed, and only the protein-altering variants were analyzed.

Results

Description of the pedigree

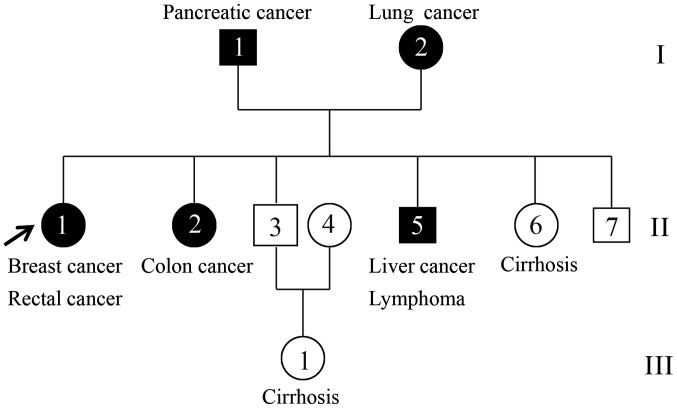

The patients with concurrent cancer were from Hubei, China. In total, two affected individuals (II-1 and II-5) and one unaffected individual (II-3) were recruited (Fig. 1). The proband (II-1) was a 68-year-old female who presented breast cancer at pathological tumor-node-metastasis (pTNM) stage pT2N2M0 and rectal cancer at stage IIIA (pTNM stage, pT4N0M0) according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines and the pTNM staging system (25–27). The younger brother (II-5) of the proband was a 61-year-old patient with concurrent cancer who suffered from liver cancer (pT3N0M0) and lymphoma at stage IIIA (28,29). The two concurrent cancer cases in the family were histologically confirmed at the hospital (30), and their tumor tissue and peripheral blood samples were collected for WES (Fig. 2). Additionally, peripheral blood was collected from one healthy family member (II-3), a 63-year-old male, and its exome was also sequenced in the present study.

Figure 1.

Pedigree chart of the family. Circles and boxes represent females and males, respectively. Black squares or circles represent patients diagnosed with cancer, whereas white squares or circles represent individuals without cancer. Samples from family members II-1, II-3 and II-5 were collected for whole-exome sequencing.

Figure 2.

Images of the hematoxylin and eosin stained sections of tumor tissues from patients II-1 and II-5. (A) Breast cancer tissue from patient II-1 at stage pT2N2M0. Magnification, ×100. (B) Rectal cancer tissue from patient II-1 at stage pT4N0M0. Magnification, ×100. (C) Liver cancer tissue from patient II-5 at stage pT3N0M0. Magnification, ×200. (D) Lymphoma tissue from patient II-5 at stage IIIA. Magnification, ×100. P, pathological; T, tumor; N, node; M, metastasis.

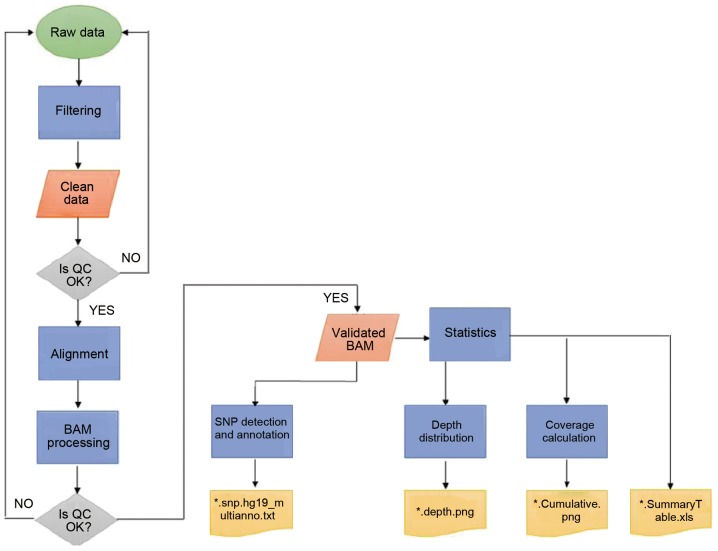

WES

To study the molecular pathogenesis of concurrent cancer, the exomes of two affected individuals (II-1 and II-5) and one unaffected individual (II-3) were sequenced. Large volumes of raw data were generated and further analyzed (Fig. 3). Quality scores across all bases were >20, which ensured the reliability of following analyses (31). Clean data were achieved by applying the aforementioned filtering processes. Following mapping to the human reference genome UCSC hg19 (17), local realignment and base quality recalibration, valid exome sequences with an average of 58X depth for each targeted base and ≥82.08% of the exonic positions covered >10X were obtained (Table II). The ratio of transition/transversion in seven samples of one unaffected (II-3) and two affected individuals (II-1 and II-5) ranged between 2.2 and 2.4 (Table III).

Figure 3.

Workflow for data analysis. BAM, binary alignment map; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; QC, quality control.

Table II.

Mean coverage and the percentage of exonic positions with coverage >10X.

| Sample | Mean coverage | Coverage >10X (%) |

|---|---|---|

| BT15061701HNDQ | 55.79X | 82.08 |

| BT15061702HNDQ | 67.14X | 90.42 |

| BT15082203HNDE | 50.01X | 93.65 |

| BT15061703HNDQ | 57.28X | 87.11 |

| BT15061704HNDQ | 75.05X | 87.97 |

| BT15082201HNDE | 51.42X | 92.75 |

| BT15082202HNDE | 52.29X | 92.66 |

Table III.

Ratio of transition/transversion in seven samples.

| Sample | Transition | Tranversion | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| BT15061701HNDQ | 266339 | 117292 | 2.270735 |

| BT15061702HNDQ | 175790 | 71318 | 2.464876 |

| BT15082203HNDE | 99653 | 43257 | 2.303743 |

| BT15061703HNDQ | 194071 | 80041 | 2.424645 |

| BT15061704HNDQ | 259392 | 111664 | 2.322969 |

| BT15082201HNDE | 68142 | 28732 | 2.371641 |

| BT15082202HNDE | 69564 | 29347 | 2.370396 |

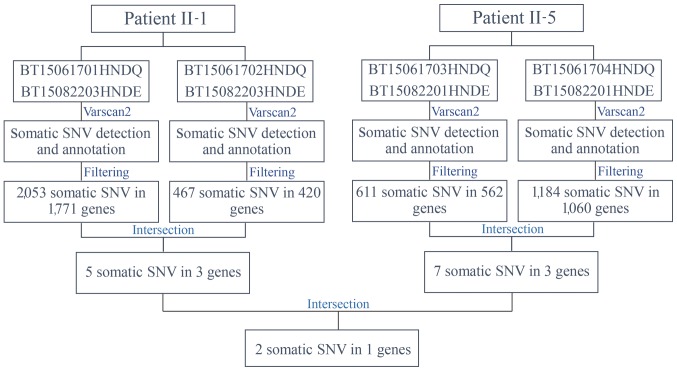

Somatic mutations

Varscan2 (32) was used to identify somatic mutations in four paired tumor tissue and peripheral blood samples from the two patients with concurrent cancer: i) BT15061701HNDQ and BT15082203HNDE; ii) BT15061702HNDQ and BT15082203HNDE; iii) BT15061703HNDQ and BT15082201HNDE; and iv) BT15061704HNDQ and BT15082201HNDE (Fig. 4). Subsequent to detection and annotation of somatic SNV, the present study focused on missense variants in the exonic regions or splice sites. Furthermore, variants with a reported frequency >0.005 in the 1,000 Genomes Pilot Project data were removed (22). As a result, 2,053 somatic mutations in 1,771 genes in breast tumor tissues, and 467 somatic mutations in 420 genes in rectal tumor tissues, from patient II-1 were detected. Further analysis for intersection revealed that five somatic mutations in three genes occurred simultaneously in the two types of tumor tissues from patient II-1 (Table IV). Similarly, seven somatic mutations in three genes occurred simultaneously in the two types of tumor tissues from patient II-5 (Table V). Among these, NDUFS7 emerged as a candidate gene with somatic mutations (g.1391151G>A and g.1393289G>C) in two patients with concurrent cancer (Table VI). NDUFS7 (g.1391151G>A and g.1393289G>C) is homozygous in breast cancer and liver cancer, while it is heterozygous in rectal cancer and lymphoma.

Figure 4.

Workflow for the identification of somatic mutations. SNV, single nucleotide variation.

Table IV.

Somatic mutations identified in the two types of tumor tissues from patient II-1.

| Gene | Nucleotide mutation | Mutation type | Amino acid alteration |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDHAL6B | g.59500155G>A | Missense variant | NM_033195:exon1:c.G1016A:p.S339N |

| g.59500166A>G | Missense variant | NM_033195:exon1:c.A1027G:p.I343V | |

| CDC27 | g.45234707T>A | Missense variant | NM_001293091:exon5:c.A336T:p.L112F |

| NDUFS7 | g.1391151G>A | Missense variant | NM_024407:exon6:c.G442A:p.V148I |

| g.1393289G>C | Missense variant | NM_024407:exon7:c.G504C:p.R168S |

CDC27, cell division cycle 27; LDHAL6B, lactate dehydrogenase A like 6B; NDUFS7, NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase core subunit S7.

Table V.

Somatic mutations identified in the two types of tumor tissues from patient II-5.

| Gene | Nucleotide mutation | Mutation type | Amino acid alteration |

|---|---|---|---|

| NDUFS8 | g.67803789A>G | Missense variant | NM_002496:exon6:c.A442G:p.T148A |

| g.67803790C>T | Missense variant | NM_002496:exon6:c.C443T:p.T148I | |

| g.67803810T>A | Missense variant | NM_002496:exon6:c.T463A:p.F155I | |

| g.67803812C>G | Missense variant | NM_002496:exon6:c.C465G:p.F155L | |

| SDHB | g.17350532C>G | Missense variant | NM_003000:exon6:c.G578C:p.S193T |

| NDUFS7 | g.1391151G>A | Missense variant | NM_024407:exon6:c.G442A:p.V148I |

| g.1393289G>C | Missense variant | NM_024407:exon7:c.G504C:p.R168S |

NDUFS7, NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase core subunit S7; NDUFS8, NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase core subunit S8; SDHB, succinate dehydrogenase complex iron sulfur subunit B.

Table VI.

NDUFS7 is a candidate gene with somatic mutations in the two patients with concurrent cancer.

| Gene | Nucleotide mutation | Mutation type | Amino acid alteration |

|---|---|---|---|

| NDUFS7 | g.1391151G>A | Missense variant | NM_024407:exon6:c.G442A:p.V148I |

| g.1393289G>C | Missense variant | NM_024407:exon7:c.G504C:p.R168S |

NDUFS7, NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase core subunit S7.

Germline mutations

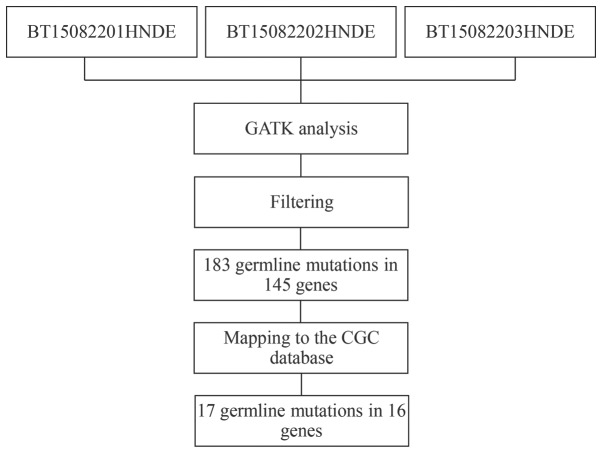

To further investigate the molecular pathogenesis of concurrent cancer, germline mutations were analyzed using GATK methods (Fig. 5). Variants in peripheral blood samples that were shared by the two affected individuals (BT15082201HNDE and BT15082203HNDE), but were not present in the unaffected individual (BT15082202HNDE) were selected. Similarly, the present study focused only on missense variants in the exonic region or splice site, and filtered out variants with a reported frequency >0.005 in the 1,000 Genomes Pilot Project data. As a result, 183 missense SNVs were detected in 145 candidate genes. Subsequently, these candidate SNVs were further mapped to the CGC database to examine probable germline mutations and genes (33). Finally, 17 SNVs in 16 genes emerged as candidate germline mutations in patients with concurrent cancer (Table VII).

Figure 5.

Workflow for the identification of germline mutations. Variants in peripheral blood samples that were shared by the two affected individuals (BT15082201HNDE and BT15082203HNDE), but were not present in the unaffected individual (BT15082202HNDE) were selected. CGC, Cancer Gene Census; GATK, Genome Analysis Toolkit.

Table VII.

Candidate germline mutations in the two patients with concurrent cancer.

| Gene | Nucleotide mutation | Mutation type | Amino acid alteration |

|---|---|---|---|

| PGLYRP4 | g.153314126C>T | Missense variant | NM_020393:exon6:c.G602A:p.R201Q |

| PEAR1 | g.156876633C>A | Missense variant | NM_001080471:exon6:c.C605A:p.T202N |

| COL6A3 | g.238243350C>T | Missense variant | NM_057166:exon38:c.G7327A:p.A2443T |

| KIF1A | g.241659323C>T | Missense variant | NM_004321:exon43:c.G4586A:p.R1529Q |

| ZNF717 | g.75786450G>A | Missense variant | NM_001128223:exon5:c.C2324T:p.T775M |

| g.75788434G>T | Missense variant | NM_001128223:exon5:c.C340A:p.Q114K | |

| ZNF141 | g.338156T>A | Missense variant | NM_003441:exon3:c.T163A:p.C55S |

| SSPO | g.149523309C>A | Missense variant | NM_198455:exon101:c.C14392A:p.P4798T |

| EPPK1 | g.144940706C>T | Missense variant | NM_031308:exon2:c.G6716A:p.R2239H |

| ZDHHC21 | g.14619085C>T | Missense variant | NM_178566:exon10:c.G677A:p.R226Q |

| CNTRL | g.123886324C>T | Missense variant | NM_007018:exon11:c.C1766T:p.T589M |

| ASCC1 | g.73973043C>T | Missense variant | NM_001198798:exon2:c.G14A:p.R5H |

| OR8U1 | g.56143823G>A | Missense variant | NM_001005204:exon1:c.G724A:p.G242S |

| PABPC3 | g.25671688G>C | Missense variant | NM_030979:exon1:c.G1352C:p.G451A |

| NPIPB6 | g.28354223G>A | Missense variant | NM_001282524:exon7:c.C983T:p.P328L |

| RAB36 | g.23488846G>A | Missense variant | NM_004914:exon2:c.G241A:p.D81N |

| CCDC117 | g.29169761T>G | Missense variant | NM_001284264:exon2:c.T234G:p.D78E |

ASCC1, activating signal cointegrator 1 complex subunit 1; CCDC117, coiled-coil domain containing 117; CNTRL, centriolin; COL6A3, collagen type VI α3 chain; EPPK1, epiplakin 1; KIF1A, kinesin family member 1A; NPIPB6, nuclear pore complex interacting protein family member B6; OR8U1, olfactory receptor family 8 subfamily U member 1; PABPC3, poly(A) binding protein cytoplasmic 3; PEAR1, platelet endothelial aggregation receptor 1; PGLYRP4, peptidoglycan recognition protein 4; RAB36, RAB36 member RAS oncogene family; SSPO, SCO-spondin; ZDHHC21, zinc finger DHHC-type containing 21; ZNF141, zinc finger protein 141; ZNF717, zinc finger protein 717.

The present study investigated the molecular alterations in concurrent cancer. By sequencing the exomes of two affected individuals and one unaffected individual in a Chinese family with concurrent cancer, the present study identified NDUFS7 as a candidate gene with somatic mutations (g.1391151G>A and g.1393289G>C), and 17 SNVs in 16 genes as candidate germline mutations. The present results provided insights into the causative alterations of concurrent cancer at the molecular level.

Discussion

It is an ongoing aim of cancer research to understand the causative mutations underlying cancer development and progression. Somatic mutations can occur in any non-germ cell of the body following conception, whereas germline mutations are inherited from the parents (4,5). During the past decades, comprehensive efforts have been made by scientists to improve the resolution and reduce the cost of sequencing methods. The genomic landscapes of common forms of human cancer have been identified (34–36). However, the molecular mechanisms of concurrent cancers remain unknown. Currently, there are no specific approaches to treat concurrent cancer. Patients with concurrent cancer are treated just like other common forms of human cancers.

Tumors evolve from benign to malignant lesions by acquiring a series of mutations over time. Somatic mutations that occur in tumor cell genomes serve a vital role in cancer development, including the initiation of tumorigenesis. In common solid tumors, including those derived from breast, colon, brain or pancreas, an average of 33–66 genes may display subtle somatic mutations that would be expected to alter the protein products (5). Of these mutations, ~95% are single-base substitutions, of which 90.7% result in missense changes, 7.6% result in nonsense changes and 1.7% result in alterations of splice sites or untranslated regions adjacent to the start and stop codons (5). In the present study, NDUFS7 emerged as a candidate gene with somatic mutations in cases of concurrent cancer. The NDUFS7 gene encodes a protein that is a subunit of complex I in the mitochondrial respiratory chain (37). Mutations in this gene cause Leigh syndrome due to mitochondrial complex I deficiency (38,39). Leigh syndrome is a severe neurological disorder that causes bilaterally symmetrical necrotic lesions in subcortical brain regions (38,39). To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first one that identified NDUFS7 as a somatic mutation gene in concurrent cancer. Further studies are required to verify how these somatic mutations in the NDUFS7 gene may cause functional alterations associated with the development of cancer.

Germline mutations inherited from the parents can increase susceptibility to cancer development (4,5). An assessment of the components of the germline genome of patients may improve the current understanding of the pathogenesis of various types of cancer. The present study identified a total of 17 germline mutations in 16 candidate genes in peripheral blood samples from patients with concurrent cancer, including the peptidoglycan recognition protein 4, platelet endothelial aggregation receptor 1 (PEAR1), collagen type VI α3 chain, kinesin family member 1A, zinc finger protein 717 (ZNF717), zinc finger protein 141 (ZNF141), SCO-spondin, epiplakin 1, zinc finger DHHC-type containing 21 (ZDHHC21), centriolin, activating signal cointegrator 1 complex subunit 1, olfactory receptor family 8 subfamily U member 1, poly(A) binding protein cytoplasmic 3, nuclear pore complex interacting protein family member B6, RAB36 member RAS oncogene family and coiled-coil domain containing 117 genes. Following mapping to the CGC database, it was identified that mutations in these genes had been previously reported to be involved in cancer progression. For example, mutations in the ZDHHC21 gene have been reported in rectal cancer but not in breast cancer, and mutations in the PEAR1, ZNF717 and ZNF141 genes were detected in liver cancer but not in lymphoma, as assessed by the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer (40–42). Notably, to the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to suggest that mutations in these genes may increase susceptibility to concurrent cancer.

In conclusion, the present study focused on a rare case of a three-generation family in which two members had developed concurrent cancer. Through WES and bioinformatics analysis, probable somatic mutations were identified in the NDUFS7 gene, and germline mutations were identified in 16 candidate genes. Although further studies are required to validate these variants, to the best of our knowledge, the results of the present study are the first to suggest a specific molecular profile associated with concurrent cancer.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded by grants from the Yichang Science and Technology Fund of Hubei Province (grant no. A16-301-27) and the Hubei Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 2017CFB455cfb455).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

XW and SW conceived the study and designed the experiments. YY, HL and LJ performed experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. LZ, AL and FD collected and analyzed the clinical data. XZ and MM performed the histological examination of the two patients with concurrent cancer. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Medical Ethics Committee of Yichang Second People's Hospital, and with the Declaration of Helsinki (15). Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the present study.

Patient consent for publication

Informed consent for the publication of the present study was obtained from all participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Chen WQ, Zheng RS, Zeng HM, Zhang SW, Zhao P, He J. Trend analysis and projection of cancer incidence in China between 1989 and 2008. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2012;34:517–524. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3766.2012.07.010. (In Chinese) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeng HM, Zheng RS, Zhang SW, Zhao P, He J, Chen WQ. Trend analysis of cancer mortality in China between 1989 and 2008. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2012;34:525–531. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3766.2012.07.011. (In Chinese) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siravegna G, Marsoni S, Siena S, Bardelli A. Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:531–548. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mardis ER. Genome sequencing and cancer. Curr Opinion Genetics Dev. 2012;22:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA, Jr, Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339:1546–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mardis ER. New strategies and emerging technologies for massively parallel sequencing: Applications in medical research. Genome Med. 2009;1:40. doi: 10.1186/gm40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mardis ER. A decade's perspective on DNA sequencing technology. Nature. 2011;470:198–203. doi: 10.1038/nature09796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esteban-Jurado C, Vila-Casadesus M, Garre P, Lozano JJ, Pristoupilova A, Beltran S, Muñoz J, Ocaña T, Balaguer F, López-Cerón M, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies rare pathogenic variants in new predisposition genes for familial colorectal cancer. Genet Med. 2015;17:131–142. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gulbahce N, Magbanua MJM, Chin R, Agarwal MR, Luo X, Liu J, Hayden DM, Mao Q, Ciotlos S, Li Z, et al. Quantitative whole genome sequencing of circulating tumor cells enables personalized combination therapy of metastatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77:4530–4541. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabour L, Sabour M, Ghorbian S. Clinical applications of next-generation sequencing in cancer diagnosis. Pathol Oncol Res. 2017;23:225–234. doi: 10.1007/s12253-016-0124-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sunami K, Takahashi H, Tsuchihara K, Takeda M, Suzuki T, Naito Y, Sakai K, Dosaka-Akita H, Ishioka C, Kodera Y, et al. Clinical practice guidance for next-generation sequencing in cancer diagnosis and treatment (Edition 1.0) Cancer Sci. 2018;109:2980–2985. doi: 10.1111/cas.13730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Dijk EL, Auger H, Jaszczyszyn Y, Thermes C. Ten years of next-generation sequencing technology. Trends Genet. 2014;30:418–426. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabbani B, Tekin M, Mahdieh N. The promise of whole-exome sequencing in medical genetics. J Hum Genet. 2014;59:5–15. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2013.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swaroop VS, Winawer SJ, Kurtz RC, Lipkin M. Multiple primary malignant tumors. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:779–783. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90440-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gandevia B, Tovell A. Declaration of Helsinki. Med J Aust. 1964;2:320–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyer LR, Zweig AS, Hinrichs AS, Karolchik D, Kuhn RM, Wong M, Sloan CA, Rosenbloom KR, Roe G, Rhead B, et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: Extensions and updates 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D64–D69. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, DePristo MA. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, Garimella KV, Maguire JR, Hartl C, Philippakis AA, del Angel G, Rivas MA, Hanna M, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van der Auwera GA, Carneiro MO, Hartl C, Poplin R, Del Angel G, Levy-Moonshine A, Jordan T, Shakir K, Roazen D, Thibault J, et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2013;43:11.10.1–33. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1110s43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.1000 Genomes Project Consortium. Abecasis GR, Altshuler D, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Gibbs RA, Hurles ME, McVean GA. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sondka Z, Bamford S, Cole CG, Ward SA, Dunham I, Forbes SA. The COSMIC Cancer Gene Census: Describing genetic dysfunction across all human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18:696–705. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0060-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koboldt DC, Chen K, Wylie T, Larson DE, McLellan MD, Mardis ER, Weinstock GM, Wilson RK, Ding L. VarScan: Variant detection in massively parallel sequencing of individual and pooled samples. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2283–2285. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, editors. 8th. Springer; New York, NY: 2017. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gradishar WJ, Anderson BO, Balassanian R, Blair SL, Burstein HJ, Cyr A, Elias AD, Farrar WB, Forero A, Giordano SH, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Breast cancer, Version 1.2017. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:433–451. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benson AB, III, Venook AP, Bekaii-Saab T, Chan E, Chen YJ, Cooper HS, Engstrom PF, Enzinger PC, Fenton MJ, Fuchs CS, et al. Rectal cancer, Version 2.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13:719–228. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benson AB, III, D'Angelica MI, Abbott DE, Abrams TA, Alberts SR, Saenz DA, Are C, Brown DB, Chang DT, Covey AM, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Hepatobiliary cancers, Version 1.2017. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:563–573. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wierda WG, Zelenetz AD, Gordon LI, Abramson JS, Advani RH, Andreadis CB, Bartlett N, Byrd JC, Caimi P, Fayad LE, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma, Version 1.2017. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:293–311. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feldman AT, Wolfe D. Tissue processing and hematoxylin and eosin staining. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1180:31–43. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1050-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.1000 Genomes Project Consortium. Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, DePristo MA, Durbin RM, Handsaker RE, Kang HM, Marth GT, McVean GA. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cibulskis K, Lawrence MS, Carter SL, Sivachenko A, Jaffe D, Sougnez C, Gabriel S, Meyerson M, Lander ES, Getz G. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forbes SA, Bindal N, Bamford S, Cole C, Kok CY, Beare D, Jia M, Shepherd R, Leung K, Menzies A, et al. COSMIC: Mining complete cancer genomes in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D945–D950. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahn SM, Jang SJ, Shim JH, Kim D, Hong SM, Sung CO, Baek D, Haq F, Ansari AA, Lee SY, et al. Genomic portrait of resectable hepatocellular carcinomas: Implications of RB1 and FGF19 aberrations for patient stratification. Hepatology. 2014;60:1972–1982. doi: 10.1002/hep.27198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reddy A, Zhang J, Davis NS, Moffitt AB, Love CL, Waldrop A, Leppa S, Pasanen A, Meriranta L, Karjalainen-Lindsberg M L, et al. Genetic and functional drivers of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cell. 2017;171:481–494.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Triepels RH, van den Heuvel LP, Loeffen JL, Buskens CA, Smeets RJ, Rubio Gozalbo ME, Budde SM, Mariman EC, Wijburg FA, Barth PG, et al. Leigh syndrome associated with a mutation in the NDUFS7 (PSST) nuclear encoded subunit of complex I. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:787–790. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199906)45:6<787::AID-ANA13>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lebon S, Minai L, Chretien D, Corcos J, Serre V, Kadhom N, Steffann J, Pauchard JY, Munnich A, Bonnefont JP, Rötig A. A novel mutation of the NDUFS7 gene leads to activation of a cryptic exon and impaired assembly of mitochondrial complex I in a patient with Leigh syndrome. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;92:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lebon S, Rodriguez D, Bridoux D, Zerrad A, Rotig A, Munnich A, Legrand A, Slama A. A novel mutation in the human complex I NDUFS7 subunit associated with Leigh syndrome. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;90:379–382. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen H, Sun X, Ge W, Qian Y, Bai R, Zheng S. A seven-gene signature predicts overall survival of patients with colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;8:95054–95065. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duan M, Hao J, Cui S, Worthley DL, Zhang S, Wang Z, Shi J, Liu L, Wang X, Ke A, et al. Diverse modes of clonal evolution in HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma revealed by single-cell genome sequencing. Cell Res. 2018;28:359–373. doi: 10.1038/cr.2018.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Varrault A, Ciani E, Apiou F, Bilanges B, Hoffmann A, Pantaloni C, Bockaert J, Spengler D, Journot L. hZAC encodes a zinc finger protein with antiproliferative properties and maps to a chromosomal region frequently lost in cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8835–8840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.