Abstract

TGFβ superfamily includes the transforming growth factor βs (TGFβs), bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), growth and differentiation factors (GDFs) and Activin/Inhibin families of ligands. Among the 33 members of TGFβ superfamily ligands, many act on multiple types of cells within the heart, including cardiomyocytes, cardiac fibroblasts/myofibroblasts, coronary endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and immune cells (e.g. monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils). In this review, we highlight recent discoveries on TGFβs, BMPs, and GDFs in different cardiac residential cellular components, in association with functional impacts in heart development, injury repair, and dysfunction. Specifically, we will review the roles of TGFβs, BMPs, and GDFs in cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, contractility, metabolism, angiogenesis, and regeneration.

Keywords: TGFβ, BMP, GDF, cardiac fibrosis, contractility, hypertrophy, regeneration, angiogenesis, metabolism

Introduction

TGFβ superfamily members, especially transforming growth factor βs (TGFβs), bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), growth and differentiation factors (GDFs) are central regulators of cellular processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation and migration in multiple cellular components of the cardiovascular system. As a result, TGFβ superfamily members control tissue and organ function during embryonic heart development and adult injury responses and partake in the pathogenesis of multiple cardiovascular diseases (Table 1).

Table 1.

The cardiac expression and functions of TGFβ, BMP, and GDF ligands in development and adult disease conditions

| Ligands | Cardiac expression | Knockout mouse phenotype in development | Involvement in adult mouse heart pathological condition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGFβ | TGFβ1 | Expressed in the heart | Perinatal mortality; excessive inflammation in the heart and lung [6,7] | Upregulated promptly after infarction and during hypertrophy [11]; suppression of inflammation [6,7]; activation of myofibroblast [115]; required for zebrafish heart regeneration [19] |

| TGFβ2 | Expressed in the heart | Perinatal mortality; defects in cardiac outflow tract, valves, septum and ventricles [5] | Upregulated promptly after infarction [11] | |

| TGFβ3 | Expressed in the heart | Viable, no cardiac abnormality | Upregulated in the later stage at infarct site [11] | |

| BMP | BMP2 | Expressed in the heart | Early embryonic lethality [181] | Upregulated in the injury border zone [36]; participation in Tbx20OE-induced cardiomyocyte proliferation post-MI [93] |

| BMP4 | Expressed in the heart | Early embryonic lethality [35] | Upregulated following pressure-overload, infarction [37], and hormonal stress [182] | |

| BMP7 | Expressed in the heart | Viable, no obvious cardiac abnormality [183] | Downregulated in pathological hypertrophy [38]; BMP7 treatment attenuated cardiac dysfunction and reduced cardiac fibrosis [38] | |

| BMP10 | Expressed in the heart | Embryonic lethal, dramatic reduction of cardiomyocyte proliferation [184] | Expression in the right atrium of adult mouse [184,185]; BMP10OE disrupted postnatal cardiac hypertrophic growth [186] | |

| BMP5 | Transiently expressed in the heart | Viable, no obvious cardiac abnormality [187] | Unknown | |

| BMP6 | Released by the liver into circulation | Viable, no obvious cardiac abnormality [188] | Unknown | |

| BMP9 | Released by the liver into circulation | Viable, no obvious cardiac abnormality [189] | Unknown | |

| GDF | GDF8 (Myostatin) | skeletal muscle and heart | Viable, excessive skeletal muscle, no cardiac abnormality [1] | Control of heart mass in the presence of various stimuli [39,40] |

| GDF11 | Expressed in the heart | No cardiac abnormality, embryonic lethality because of defects in kidney, GI tract, palate [190,191] | Downregulated in aged/infarcted hearts; antagonism against aging-related hypertrophy [41,42]; promotion of cardiac progenitor cells after injury [42,46] | |

| GDF15 | Low expression in the heart | Viable, no obvious cardiac abnormality [192] | Induced post-MI; prevention of rupture post-MI by blocking excessive polymorph nuclear leukocytes recruitment [43] |

TGFβ family and the downstream signaling pathways

There are three TGFβ ligands, TGFβ1, β2, and β3, all of which are expressed in the heart and upregulated in cardiac disease conditions [1–4]. TGFβ1 differs from TGFβ2 in its temporal–spatial expression pattern during heart development [4], and may have distinct functions [5]. TGFβ1 knockout causes excessive inflammatory responses in the heart and lung leading to lethality [6,7]. TGFβ2 knockout does not phenotypically recapitulate TGFβ1-knockout mice, instead, it causes broad organ defects due to impaired epithelial–mesenchymal-transition (EMT) processes [5]. TGFβ3-knockout mice do not have a cardiac phenotype, rather they showed palatal fusion defects resulting in cleft palate [8]. Nevertheless, in adult mouse, the functional differences among TGFβ1, β2, and β3 are not well documented [1,2,9,10].

Following cardiac ischemic injury, TGFβ1 and β2 are upregulated early, while TGFβ3 exhibits a delayed and sustained induction [11]. During myocardial hypertrophic growth, levels of the three TGFβ ligands also increase significantly in the myocardium [3]. The secreted TGFβ, in the propeptide form, is stored in the latent complexes at the extracellular matrix (ECM) and released by an activation process mediated by integrins, proteases and matrix proteins [12–14]. In the healthy heart, TGFβ is released by cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells [10,15]. During injury repair, it is also secreted by myofibroblasts and infiltrating immune cells [16,17].

TGFβ ligands bind to type II receptors (TGFβRII) and type I receptors (TGFβRI) to initiate Smad2/Smad3-dependent and -independent (e.g. TAK1, MAPK, and Akt) signaling and the subsequent transcriptional outcomes. The major TGFβ type I receptor, Alk5, is expressed in cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, coronary smooth muscle cells and epicardial cells in the heart of mammals and zebrafish, and transduces TGFβ ligand-elicited effects in processes such as epicardial EMT and myocyte regeneration [18–20]. TGFβ also binds to Alk1 to activate the SMAD1/5/8 signaling pathway; this TGFβ–Alk1–SMAD1/5/8 pathway promotes endothelial cell proliferation, migration and angiogenesis [21,22]. TGFβ is also the major regulator of myocyte–fibroblast interactions. Locally released TGFβ acts on cardiac fibroblasts to induce fibroblast-to-myofibroblast conversion and promote ECM synthesis [23,24]. It is noteworthy that TGFβ ligands display multi-faceted effects on immune cells. They help recruit neutrophils [25], but also repress pro-inflammatory activities of macrophages and promote macrophage polarization to modulate cardiac inflammatory responses [26].

BMP family and the downstream signaling pathway

BMPs were first discovered as inducers of ectopic bone and cartilage formation and named after these functions. BMP2–4 were cloned soon afterwards and found to share homology with TGFβ protein [27,28]. Since then, more than 20 BMPs have been identified. Many BMPs (e.g. BMP2, BMP4, and BMP10) are directly expressed in myocardium and coronary vessels; others (e.g. BMP6 and BMP9) are secreted from liver into the circulation [29,30]. Beyond their roles in bone/cartilage induction, the essential functions of BMPs in cardiac development and cardiomyogenesis in vitro have been well documented [31–35]. Upon cardiac injury, BMP ligands are differentially regulated [36–38]. For example, BMP4 levels are elevated in pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy, acute infarction, and chronic ischemic heart disease [37]. Conversely, BMP7 levels are reduced during pressure overload-induced hypertrophy [38].

BMP ligands bind to type II and type I receptor complexes to initiate Smad1/Smad5/Smad8-dependent or -independent (e.g. MAPK and p38) signaling and subsequent transcriptional regulation. BMP-responsive type I receptors include the BMP receptor type IA (BMP-RIa, also known as Alk3), type IB (BMP-RIb, also known as Alk6), Activin receptor type 1 (ACVR1, also known as Alk2), and Activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ACVRL1, also known as Alk1). The type II receptors include BMP receptor type II (BMPRII), Activin receptor type 2A (ActRIIA), and type 2B (ActRIIB). These types I and II receptors allow for more than 11 types of receptor complex combinations that contribute to the functional diversity of BMP ligands.

GDF subfamily and downstream molecular signaling pathways

Several GDFs, e.g. myostatin (GDF8), GDF11, and GDF15, are expressed in the heart and play distinct functions [39–43]. Myostatin is primarily expressed in the skeletal muscle and best known as the major negative regulator of skeletal muscle growth and hypertrophy. Interestingly, myostatin is also present in fetal and adult hearts [44], especially under pathological conditions, such as infarction, hypertrophy, and heart failure [45]. GDF11 levels decline with age and it is associated with aging-related cardiac diseases [41,42], although its therapeutic effects remain controversial [46–48]. GDF15 is another heart-derived hormone that is elevated in cardiac pathological conditions and exhibits cardiac protective functions [43,49,50].

GDF ligands induce signaling through a diverse array of receptors. Myostatin (GDF8) binds to the ActRIIA/B and recruits Alk3/Alk4/Alk5 to activate Smad2/Smad3-dependent inhibition of Akt–mTOR signaling [44,45,51]. GDF11 is highly homologous to myostatin, utilizes the same receptor complexes, and induces similar transcriptional outcomes as myostatin [41,52], but is more potent [53]. GDF15 activates Smad2/Smad3, but the receptors utilized remain elusive [50]. Recently, a GDF15 has been revealed to bind with a distant member of TGFβ superfamily receptor, GDNF family receptor α-like (GFRAL) which is predominantly expressed in the brain [54,55]. GDF15 binds to GFRAL and its co-receptor RET to activate Erk, Akt, and PLCγ pathways in neurons, leading to reduction in energy intake and weight loss [54–57]. It remains unclear whether similar mechanisms are employed in the heart.

In the heart, TGFβ superfamily ligands act on multiple cell types, including cardiomyocytes, cardiac fibroblasts, coronary endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, cardiac residential immune cells, and stem/progenitor cells, via autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine mechanisms. In this review, we aim to highlight recent discoveries on TGFβ superfamily members in different cellular components within the heart that lead to functional impacts in cardiac dysfunction and regeneration (Fig. 1). A detailed hierarchical classification of TGFβ ligands, receptors, and key signaling proteins can be found in several recent reviews [58–61].

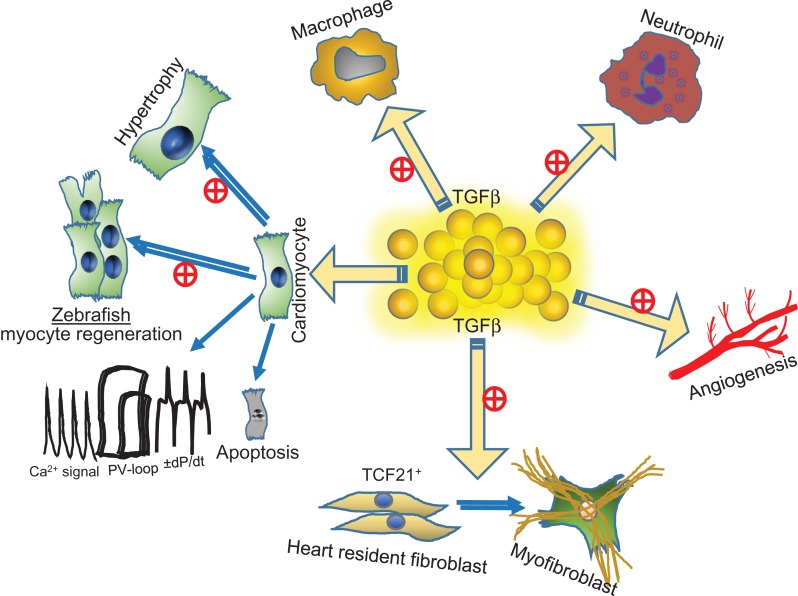

Figure 1.

The effects of TGFβ on multiple cell types within the heart TGFβ significantly promotes cardiac fibroblast-to-myofibrolast transition and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, enhances cardiomyocyte regeneration in zebrafish, increases cardiomyocyte apoptosis, and promotes angiogenesis in the embryonic stage. TGFβ also modulates Ca2+ signal and contractility at the cellular and organ levels, but the effects are divergent. Additionally, TGFβ modulates macrophage and neutrophil functions.

Roles of TGFβ, BMP, and GDF Signaling Pathways in Cardiac Pathophysiology

Cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, survival, and metabolism

Earlier studies using mouse genetic models with cardiomyocyte-specific TGFβ ligand deficiency demonstrated that myocyte-released TGFβ acts on multiple cell types within the cardiac microenvironment and modulates cell–cell interactions, therefore stimulating a collection of outcomes including cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, and worsening of ventricular function [62,63]. In recent years, cardiomyocyte-specific manipulations of intracellular mediators further elucidated the myocyte-intrinsic functions of TGFβ signaling. Inducible cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of TgfβRII reduced fibrosis, decreased hypertrophy, and improved function, but depletion of TgfβRI failed to do so. Mechanistically, TGFβRII deficiency reduced Smad2/3 and TAK1 activation in both myocyte and interstitial cells, but TGFβRI depletion only inhibited myocyte Smad activation without reducing interstitial Smad2/3 activation and did not reduce TAK1 activation in either cell type. These findings suggest that myocyte-to-interstitial cell signaling plays critical roles and highlight the non-Smad pathway mediated by TAK1 as a major component in maladaptive hypertrophic and ventricular dysfunction [64]. TGFβ signaling has also been shown to modulate cell death. TGFβ stimulation enhances cardiomyocyte apoptosis via Smad4 and AP1 signaling [65,66], whereas TGFβ treatment was also found to protect cardiomyocyte from apoptosis and necrosis in response to ischemia reperfusion in vitro and in vivo [67,68], suggesting that myocyte-secreted TGFβ1 modulates the microenvironment to reduce cell death. Genetic studies using non-inducible models also showed that TGFβ signaling homeostasis is crucial for heart development and functional maintenance. Overexpression of SMAD4 reduced cardiomyocyte hypertrophic responses to α-adrenergic stimulation [69]. Cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of Smad4 or Smad7 induces maladaptive hypertrophy and dysfunction, one associated with enhanced MEK–ERK signaling [70,71], the other associated with enhanced Smad2/Smad3 signaling [72] (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

TGFβ family members exhibit distinct effects on heart hypertrophy TGFβ binds to its own receptors RII and RI, activates TAK1, SMAD2/3, and p38, and moderately promotes cardiac hypertrophy. Several GDFs antagonize heart hypertrophy at the physiological range of concentration. GDF8 exhibits anti-hypertrophy effect in the heart by multiple mechanisms. It inhibits the pro-hypotrophic PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, but also suppresses AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-mediated glycolysis, ATP production in the heart. GDF11 shows similar effect as GDF8, but its mechanism is not as well studied as GDF8. GDF15, by modulating SMAD2/3 and PI3K/Akt signaling, exhibits anti-hypertrophy function.

Besides stimulating fibroblast activity, myocytes also direct immune cell activity through TGFβ signaling. Cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of either TgfβRI or TgfβRII protected the heart against early-onset rupture related-mortality by dramatically reducing neutrophil recruitment and enhancing protective cytokine production [25]. Consistent with these findings, cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of Smad7 caused elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages [71].

Several BMP and GDF ligands also modulate myocyte functions. Recombinant BMP7 treatment attenuated cardiac dysfunction and reduced cardiac fibrosis and ventricular remodeling under pressure overload [38]. GDF8/myostatin inhibits cardiac hypertrophy upon physiological and pathological stimuli, besides its inhibitory effects on skeletal muscles [39,40,73]. Genetic inactivation of Gdf8 enhances the hypertrophic response to both α- and β-adrenergic stimulation due to increased p38, Akt phosphorylation and enhanced Ca2+ transients, respectively [39,40]. GDF8 also controls cardiomyocyte metabolism and loss of Gdf8 shifts cardiomyocytes towards glycolytic metabolism via AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) [45]. Another GDF ligand, GDF11, has been associated with aging. GDF11 expression decreases in the blood and hearts of aged mice, and in infarcted hearts. Using heterochronic parabiosis, a surgery approach that creates shared circulation between a young and an old mouse, GDF11 is identified as a systematic factor in the young blood antagonizing cardiac hypertrophy in old mice and the protective effects have been attributed to reduced phosphorylation of Forkhead transcription factors such as FoxO2 and FoxO3α [42]. This is further supported by subsequent finding that circulating GDF11 declines with age in multiple species, including mouse, rat, horse, and sheep, that administration of GDF11 decreased heart mass in both young and old mice [41], and that delivery of GDF11 mRNA in aged mouse heart after MI enhanced myocardial regeneration through increasing Sca-1+ stem cells [46]. But the conception of GDF11 as a ‘youth factor’ that rejuvenates the aged heart has also been challenged when recombinant GDF11 failed to reduce cardiac hypertrophy or improve contractile function in aged mice, and failed to extend lifespan in a murine genetic model of premature aging [48,74,75].

GDF15 surges in pathological situations [49], such as myocardial infarction [43,49] and pressure overload [50]. GDF15 reduces pressure overload-induced hypertrophy [50]. GDF15 also protects cardiomyocyte from apoptosis and protects heart from rupture, through either activating PI3K/Akt or inhibiting polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltration [43].

Cardiomyocyte contractility and TGFβ/BMP/GDF effects on ion channels

It’s not surprising, considering the heart is enriched in ion channels controlling electrophysiological function, that the multipotent TGFβ1 regulates ion channels. In cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes, serum deprivation eliminates spontaneous beating, but supplementation of TGFβ1 was sufficient to restore spontaneous beating [76]. However, in the presence of serum, TGFβ1 reduced spontaneous beating by ~20% in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes [77], suggesting that a precise control of TGFβ1 levels is required for the homeostasis of cardiac contractility. There is also evidence for an alteration in sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) structure and Ca2+ handling, specifically an increase in inositol trisphosphate (IP3) receptor-mediated calcium release. TGFβ1 increased the mRNA levels of Na+/Ca2+-exchanger in cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes [78]. This effect could be blocked by PKC and MAPK inhibitors, which suggests a non-Smad mechanism downstream of TGFβ signaling. In adult cardiomyocytes, sustained exposure to TGFβ1 (for 3–4 h) caused myocyte dysfunction, as measured by slower contraction and relaxation during field electrical stimulation [79]. This TGFβ1 treatment was associated with an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) and an upregulation of NADPH oxidase, and the contractile dysfunction could be partially prevented by ROS scavenging or NADPH oxidase inhibition.

A cardiomyocyte-specific Tgfβ1 overexpressing mouse, in which the atria, but not the ventricles, were heavily fibrotic, displayed a modestly increased susceptibility to atrial fibrillation [80]. However, this effect was ascribed to conduction alterations within the atrial tissue, and not to alterations in sinoatrial or atrioventricular node activity. Nor was alteration in cardiomyocyte action potentials identified when measured by intracellular microelectrodes. Avila et al. [81] found that 3 days of TGFβ1 treatment reduced L-type voltage gated Ca2+ channel expression in neonatal rat atrial cardiomyocytes, but they did not observe any effect on L-type or T-type Ca2+ channel expression in ventricular cardiomyocytes. In a follow up study, Ramos-Mondragón et al. [82] also found that TGFβ1 reduces Na+ and K+ currents in cultured atrial cardiomyocytes. TGFβ1 increased inward Na+ current density (INa), but reduced transient outward K+ current density (Ito) on cultured adult rat ventricular cardiomyocytes in a whole-cell voltage-clamp study [83]. TGFβ1 treatment also significantly increased the mRNA level of Na+ channel SCN5A (Nav1.5), but reduced the expression of K+ channels KCNIP2 (Kchip2) and KCND2 (Kv4.2) [83]. This increase in SCN5A mRNA was blocked by PI3K inhibitor LY29004, once again suggesting a non-Smad pathway-mediated modulation of cardiomyocyte ion channel function. These ion channel alterations may play a role in promoting arrhythmias during heart disease, but more studies in disease models or patient samples are needed to complement these cell culture experiments.

Minimal work has been done on potential roles of BMP and GDF in cardiac electrophysiology. A study using Alk3null/flox;cGATA6-Cre mice to specifically knockout BMPR1a in cardiomyocytes of the atrioventricular canal found abnormal atrioventricular node function [84]. Some of these mutant mice showed electrical bypass tracts and abnormal conduction across the ventricles, and these were correlated with disorganized or fibrotic AV nodes. Thus, a defect in BMP signaling during development can impair the formation of the cardiac conduction system.

Taken together, these results clearly showed that TGFβ-induced signaling, and potentially BMP signaling, modulates the electrical properties of the heart, and of cardiomyocytes themselves, predominantly through non-Smad pathways, including PKC, MAPK, and PI3K–Akt. However, in the case of TGFβ, the effects and mechanisms appear distinct between the atria and ventricles, and between adult and neonatal cardiomyocytes. More work is needed to unravel the roles of TGFβ and BMP-stimulated pathways in electrical properties of the heart and elucidate how TGFβ and BMP-mediated alterations may contribute to arrhythmias and other complications during heart disease.

Cardiomyocyte regeneration

Adult human cardiomyocytes regenerate at a very low rate. Taking advantage of radioactive carbon-14 (14C), Bergmann et al. [85,86] found that cardiomyocyte renewal in human hearts is highest in early childhood, and gradually declines to 1% at age 25 and 0.45% at age 75. Cardiomyocyte renewal is stimulated by injury, as indicated by genetic fate mapping in mouse models whereby de novo cardiomyocyte generation increased after myocardial infarction or pressure overload-induced injuries [87]. Nevertheless, this very low rate of cardiomyocyte regeneration makes it impossible for the mammalian heart to heal itself following injuries. Progress in the understanding of cardiomyocyte renewal and its cellular sources has highlighted TGFβ and BMP pathways as potential targets to enhance the regenerative capacity.

TGFβ and BMP pathways are among the vital pathways required for zebrafish heart regeneration [88,89]. The zebrafish heart has been a valuable inspiration and a model to emulate in that it is able to fully regenerate following injury [90]. Genetic fate mapping studies have shown that the newly formed cardiomyocytes are generated from resident cardiomyocytes, which undergo dedifferentiation followed by proliferation and a subsequent re-differentiation process. TGFβ ligands are induced following injury in the zebrafish heart and inhibition of TGFβRI (Alk5) abolished zebrafish heart regeneration [19]. TGFβ promotes transient scar formation, and cardiomyocyte regeneration fails if transient scar formation is impaired in zebrafish [19]. During the transition from scar formation to scar resorption, the expression levels of TGFβ1, β2, and β3 are elevated and activate the downstream Smad2/Smad3 in the injury zone [19]. SB431542 treatment that blocked TGFβ signaling abolished zebrafish heart regeneration [19,88]. Another study also showed that SB431542 decreased cardiomyocyte proliferation in a zebrafish model of ventricular resection [88]. BMP signaling is involved in cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation. The BMP ligands Bmp2b and Bmp7, receptor BMPRIA (Alk3a) and target gene product Id2b are dramatically increased in the injury border zone [89]. Furthermore, genetic ablation or chemical inhibition of BMP signaling diminishes cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and myocardial regeneration, and overexpression of the BMP ligand bmp2b is sufficient to enhance cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and myocardial regeneration [89].

As for mouse heart regeneration post injury, the effects of TGFβ superfamily members are more variable. Pharmacological inhibition of TGFβRI by a small molecule A83-01 in the adult heart post injury accelerates cardiac repair by dramatically increasing Nkx2.5+ cardiomyocytes or Nkx2.5+/Sca1+ cardiac progenitors [91,92], whereas activation of BMP2–pSmad1/5/8 signaling, together with activation of PI3K–Akt, Yap, and β-catenin pathways, are associated with augmented proliferation of cardiomyocytes in a model of cardiomyocyte-specific overexpression of Tbx20 [93,94]. Dedifferentiation of resident cardiomyocytes, characterized by the disassembly of sarcomeric structures, electrical uncoupling, and re-expression of cell cycle regulators, facilitated zebrafish cardiomyocyte renewal after injury [89,95,96]. Rodent cardiomyocyte regeneration from dedifferentiation has also been explored in a few studies [97,98]. However, it is not clear whether TGFβ superfamily members are involved in this essential cellular process in the mammalian heart.

An alternative approach to target heart diseases is to take advantage of exogenous sources of cardiomyocytes, which employ embryonic stem cell (ESC), induced-pluripotent stem cell (iPSC), and directly reprograming technique for de novo cardiomyocyte generation [99,100]. TGFβ family signaling is critically involved in ES cell-derived cardiomyocyte differentiation. SMAD gene cluster expression persists throughout the differentiation stages, with continuous expression of SMAD1, SMAD2, and SMAD4 genes and a delayed expression of SMAD3 [101]. Functional studies further demonstrate that TGFβ–Smad signaling is a barrier during reprogramming. TGFβRI inhibitor A83-01 greatly increased the efficiency of Mesp1-induced cardiac differentiation in ES cells [102]. Similarly, a compound named 1,4-dihydropyridine, identified in a molecule screening, induces ESC-based cardiomyocyte differentiation specifically via degradation of TGFβRII [103]. Similar findings hold true in other types of in vitro cardiomyocyte differentiation processes [104,105].

TGFβ family signaling is also one of the major hurdles for direct reprogramming of cardiac fibroblasts to cardiomyocytes. Direct reprogramming of cardiac fibroblasts to cardiomyocytes has been achieved using a cocktail of transcriptional factors GATA4, HAND2, MEF2C, and TBX5 [106]. Injection of these transcriptional factors or the corresponding mRNAs into the ischemic zone following infarction converts cardiac fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes and improves heart function [104]. However, the reprogramming efficiency is less than ideal. Several efforts that succeeded in enhancing the efficiency involve the inhibition of TGFβ signaling. A combination of TGFβ inhibitor SB431542 and WNT inhibitor XAV939, in the presence of Gata4, Mef2c, and Tbx5 factors (GMT), significantly boosts the efficiency for the reprogramming of cardiac fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes and improves cardiac functional preservation after infarction in vivo [104]. Inhibition of TGFβ signaling also promotes epicardial differentiation. TGFβ inhibitors (either A83-01, SB505123, or SB431542) dramatically enhanced the expansion of human iPSC-derived epicardial cells and increased the expression of the epicardial marker WT1 [105]. This is also in line with the reports that pharmacological inhibition of TGFβRI with A83-01 increased Nkx2.5+/Sca1+ cardiomyocytes after injury [91,92]. This evidence demonstrates that suppression of TGFβ signaling is a key step for efficient reprogramming or differentiation to cardiomyocytes [107].

In contrast to TGFβ, BMPs, especially BMP4, act in concert with other growth factors such as Activin A and FGF2 to promote pluripotent stem cell differentiation in vitro [108–111]. In human ES cell differentiation, BMP4 is critical in the growth factor cocktail to promote the generation of the KDR+/c-Kit− population of cardiomyocyte-like cells [108]. It was also shown that mouse ES cell-derived cardiac mesoderm/cardiomyocyte formation is determined by coordinated action of BMP4 and Activin/Nodal [109]. Indeed, recently developed protocols using BMP4 or BMP plus FGF2 under hypoxic conditions achieved great efficiency of cardiac differentiation from human ESC and iPSC [112,113]. However, it is important to recognize that sustained BMP signaling can have profound inhibitory effects on contracting cardiomyocytes [109], which indicates that temporal control of these growth factors is crucial for cardiogenesis.

TGFβ/BMP/GDF signaling in cardiac fibroblasts and myofibroblasts

Under cardiac pathological conditions, the renin–angiotensin system is hyperactive and releases stress hormones, such as angiotensin II (AngII) and endothelin 1 (ET1). Almost simultaneously, due to mechanical forces and hormone stress, TGFβ expression surges in the heart, leading to cardiac fibrosis [114,115]. The major contributors to the fibrotic process are myofibroblasts, marked by expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)-positive stress fibers. They are primarily derived from cardiac resident fibroblasts in response to TGFβ stimulation [23,24], secreting ECM in the heart upon injury [116,117]. Myofibroblasts physically bind to the ECM through integrins, forming structural support of the injured heart and maintaining tension to facilitate reparative fibrosis [118]. It was previously believed that the resident endothelial, immune/myeloid and smooth muscle cells all contribute to myofibroblast generation [115], but recent findings demonstrated that cardiac resident TCF21+ fibroblasts are the only major source for myofibroblasts in the heart following injury [119,120].

TGFβ induces myofibroblast differentiation through both Smad-dependent and independent pathways (Fig. 3). TGFβ induces the Smad3-dependent pathway to promote the expression of α-SMA and ECM components, such as of Col1α, Col3α, Col5α, Col6α, and Fibronectin [121,122]. Fibroblast-specific deletion of TGFβRI/II or Smad3 impaired myofibroblast differentiation, diminished fibroblast-derived ECM production, and dramatically reduced cardiac fibrosis [122,123]. Whole body knockout of Smad3 caused a similar decrease in α-SMA expression and ECM production, but interestingly increased myofibroblast infiltration into the scar area after myocardial infarction [121]. In contrast to Smad3, Smad2 has been shown to be dispensable for this TGFβ-induced function [122]. TGFβ induced Smad-independent signaling also modulates myofibroblast function. TGFβ induces p38 to promote the expression of transient receptor potential cation channel 6 (TRPC6), a mediator of the Ca2+–Calcineurin–NFAT pathway, to promote myofibroblast differentiation and wound healing [123]. TGFβ also induces myofibroblast differentiation through modulation of mRNA stability that involves the RNA binding protein muscleblind-like1 (MBNL1) [124]. Additionally, TGFβ protects myofibroblast from apoptosis during infarction by activation of both Smad2/Smad3 and AKT pathways [125].

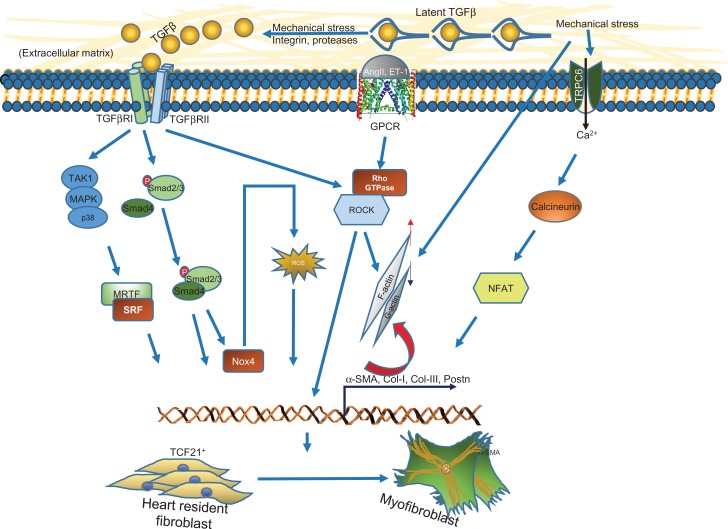

Figure 3.

TGFβ stimulates cardiac resident fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition Stress-induced TGFβ release from the latent complex leads to the activation of membrane-bounds TGFβ receptor complexes, which induces Smad2/Smad3 and multiple non-Smad signaling pathways, including TAK1, MAPK/p38, and Rho-GTPase/Rock for activation of myofibroblast specific genes, such as α-SMA, Col-I, Col-III, Postn. Smad2/Smad3 also induce the expression of Nox4, which generates ROS to maintain myofibroblast phenotypes. Additionally, GPCRs activated by angiotensin or endothelin activate the Rho-GTPase/Rock to promote myofibroblast formation. Mechanical force directly activates TRPC6 channel to induce fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition via Ca2+/Calcineurin/NFAT pathway.

TGFβ actively controls matrix composition and turnover. It not only promotes myofibroblast secretion and deposition of ECM components, but also increases the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), enzymes that degrade and remodel the ECM, as well as multiple members of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP), which antagonize MMPs [126,127].

These key functions of TGFβ in fibrosis inspired the use of inhibitors that target TGFβ ligand or its receptor Alk5 for reducing fibrosis-related malfunction of the heart. These inhibitors reduced injury-induced fibrotic contraction dysfunction [128,129]. However, they also caused severe problems, such as increased inflammatory lesions and worsened vascular remodeling, and failed to ameliorate myocyte hypertrophy, which altogether led to soaring mortality [62,117,130,131]. At early phase post-infarction, TGFβ reduces myocardial damage by repressing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) to prevent excessive inflammation [132]. Global inhibition of TGFβ at the early stage post-infarction worsened cardiac remodeling, leading to approximately 100% mortality [62,63]. However, local blockade of TGFβ signaling by cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of either TGFβRI or TGFβRII protected the heart against early-onset rupture related-mortality [25,64]. This cardiomyocyte-specific blockade of TGFβ signaling reduced neutrophil recruitment and enhanced the secretion of protective cytokines, including thrombospondin 4, interleukin-33, and GDF15 [25].

BMP family members have divergent roles in fibroblast biology and cardiac fibrosis. BMP4 is increased in both TAC and AngII-induced cardiac fibrosis [133]. Isolated cardiac fibroblasts incubated with BMP4 differentiated into myofibroblasts as demonstrated by increased expression of α-SMA and collagen. This myofibroblast differentiation could be blocked by the NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin or the antioxidant Tempol, demonstrating a role for oxidative stress in the process. In contrast, BMP7 antagonizes TGFβ effects through Smad1/5 signaling. BMP7 inhibits TGFβ-induced myofibroblast differentiation in vitro and attenuates cardiac fibrosis in vivo [134]. Recombinant BMP7 treatment also attenuated cardiac dysfunction and ventricular remodeling [38].

Additionally, perivascular progenitor cells that are glioma associated oncogene-1 (Gli1)-positive transdifferentiate into α-SMA+ myofibroblasts that contribute to both interstitial and perivascular fibrosis following cardiac chronic injury. Genetic ablation experiments further suggest a significant contribution of these Gli1+ cells to cardiac fibrosis [135]. Whether TGFβ is important in this particular transdifferentiation remains unknown.

TGFβ/BMP/GDF signaling in coronary vessel cell types: endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and pericytes of the heart

There is significant evidence supporting the idea that angiogenesis occurs in the heart following various injuries. Rebuilding the injured heart requires the appropriate density of vessels to carry nutrients and oxygen for cardiomyocytes. Vascular morphogenesis and homeostasis are tightly regulated by the growth factors VEGF, FGF, angiopoietin, ephrin, and Dll4 [136–139]. Unfortunately, despite the demonstrated safety of gene therapy and recombinant protein therapy of vascular growth factors, they have failed in clinical trials during phases II and III [140]. One of the reasons is that they formed leaky angiomas instead of functional capillary vessels in the heart [141]. Broader and novel insight of cardiovascular vasculogenesis is needed for truly regenerative therapies.

Cumulative evidence has shown that TGFβ superfamily factors, especially BMPs, e.g. BMP2, 4, 6, 7, and 9, also play essential roles for regulating vascular growth and homeostasis, including angiogenesis and arteriogenesis, mainly from studies of heart development [142–145]. Coronary vessel formation in the heart involves three elaborate processes, vasculogenesis (formation of primitive vascular structure from endothelial precursor cells), angiogenesis (generation of new microvessels from endothelial proliferation and migration via intussusception or sprouting), and arteriogenesis (maturation of arteries by recruitment of supporting smooth muscle cells and pericytes). A primitive vascular plexus in the myocardium is formed by E13 in mouse [146], but the developmental process of vascularization in the heart continues to as late as 3 weeks postnatal [147] or even into adulthood [148]. It is worth noting that hypoxia is the major driving force in embryonic vasculogenesis [149]. TGFβ acts in synergy with hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) to promote VEGF gene expression in human endothelial cells [150], but whether TGFβ participates in hypoxia-induced angiogenesis during heart development remains largely unclarified. Mice that are null of either TGFβRI (Alk5), activin receptor-like kinase 1 (Acvrl1 or Alk1) or endoglin (Eng) genes show embryonic lethality due to major defects in angiogenesis and heart development. Mice with TGFβ1 or TGFβRII deficiency die at E14.5 with failed vascular plexus formation in the heart [151]. In an embryonic chick epicardial explant study, both TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 inhibit endothelial induction, but promote smooth muscle cell formation [152]. These limited data indicate that TGFβ1 controls early coronary development in a delicate spatiotemporal way. Unfortunately, no research has investigated TGFβ specifically during the later stage when coronary arteriogenesis occurs [148].

GFP labeled-BMP signaling reporter (BRE::gfp) mice exhibit dynamic mosaic BMP expression in various angiogenic sprouting plexuses and the endocardium in the developing mouse heart [145]. Interestingly, proliferating endothelial cells were almost exclusively GFP− (low level of BMP–Smad1/5/8 signaling), but neighboring non-proliferating endothelial cells are GFP+ in the developing heart [144]. It was further elucidated based on Smad1/5/8 signaling that tip-cells (low signaling) rather than stalk-cells (high signaling) were selected for vessel branching [142,153]. During cardiogenesis, BMPs crosstalk with several key signaling molecules, such as Notch, Wnt, and FGF to tightly control the development and homeostasis of the epicardium, endocardium, outflow tract, and valve [154–157]. Nevertheless, not many vasculogenesis/angiogenesis-focused studies have directly targeted TGFβ superfamily during the later stage of embryonic heart development or in adult heart [148].

A wealth of evidence in vasculogenesis/angiogenesis of the vascular system outside the heart has shown that BMP signaling has either pro-angiogenic or anti-angiogenic functions, depending on the ligand-receptor combination and cellular targets [143,158]. For example, BMP9, a circulating BMP, suppresses both FGF-induced and VEGF-induced angiogenesis in vitro via Alk1 receptor, and even inhibits lymphatic vessel formation [159–161]. On the contrary, low concentration of BMP9 promotes proliferation and migration in multiple types of endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo [162]. BMP2, 4, 6, and 7 induce endothelial cell proliferation, migration and angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo [143]. In zebrafish embryo, BMP2b and BMP6 promote sprouting in concert with Notch signaling [163]. It is worth noting that excessive BMP signaling is associated with vascular inflammation, endothelium calcification and atherosclerosis [164,165]. Therefore, the precise control of autocrine and paracrine BMP signaling is a prerequisite to produce beneficial outcomes for the heart.

The majority of coronary smooth muscle cells and pericytes are formed via EMT from the epicardium [166,167], which is derived from proepicardium [168]. TGFβ is a potent inducer of the vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) fate [169]. Smad3, in synergy with SRF and δEF1 (also known as ZEB-1), activates smooth muscle-specific genes following TGFβ stimulation [170]. TGFβ also inhibits proliferation and migration of VSMCs [171–173]. Interestingly, TGFβ-induced differentiation of VSMCs from precursor cells is more robust when in contact with endothelial cells, as indicated by co-culture experiments [174]. In contrast to TGFβ, BMP2 stimulates VSMC migration, as shown by a transwell migration assay [175]. BMP2 also inhibits VSMC proliferation, an effect similar to TGFβ [175]. BMP7 also inhibits VSMC proliferation, and promotes VSMC fate maintenance in culture [176]. Both BMP4 and TGFβ have been shown to maintain VSMC-specific gene transcription through the processing of miR-21, downstream of Smad activation [177].

Pericytes in the retina and kidney have been shown to differentiate into myofibroblasts in response to TGFβ [178,179]. However, despite a few studies showing that pericytes may be a potential source of fibrosis in the heart [135,180], it is unknown whether TGFβ induces pericyte activation in the heart or coronary blood vessels. Future studies are needed to investigate this intriguing possibility.

Perspectives

TGFβ superfamily pathways exert diverse functions during cardiac dysfunction in a context-dependent manner. A global manipulation of TGFβ pathway components often produces divergent effects in different target cell types. The development of tissue-specific Cre lines has significantly improved the understanding of tissue-specific functions of TGFβ superfamily pathways and elucidated many of the confounding outcomes from global manipulation of TGFβ pathway components. Recent findings suggest that targeting TGFβ-induced Smad3 signaling in myofibroblasts is a promising strategy to treat cardiac fibrosis and improve cardiac function in mouse chronic injury models. It remains challenging, however, to target and manipulate TGFβ signaling in a myofibroblast-specific manner for the development of translatable approaches. Another important question is the role of BMPs during cardiac dysfunction. The functions of many BMP ligands have been characterized in the context of cardiovascular development, but their roles in the adult cardiac diseases remain poorly understood. Much progress is needed in defining their functions during cardiac remodeling and dysfunction.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr Bridget Samuels (University of Southern California) for review and editing of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the grants from the Postdoctoral fellowship from American Heart Association (#15POST25710243 to J.W.; #15POST22730019 to O.J.), the Beginning Grant-in-Aid from American Heart Association (#16BGIA26540000 to J.X.), and the Start-up Fund from the Provost at USC (to J.X.).

References

- 1. McPherron AC, Lawler AM, Lee SJ. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-beta superfamily member. Nature 1997, 387: 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dewald O, Ren G, Duerr GD, Zoerlein M, Klemm C, Gersch C, Tincey S, et al. Of mice and dogs: species-specific differences in the inflammatory response following myocardial infarction. Am J Pathol 2004, 164: 665–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li JM, Brooks G. Differential protein expression and subcellular distribution of TGFbeta1, beta2 and beta3 in cardiomyocytes during pressure overload-induced hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1997, 29: 2213–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Millan FA, Denhez F, Kondaiah P, Akhurst RJ. Embryonic gene expression patterns of TGF beta 1, beta 2 and beta 3 suggest different developmental functions in vivo. Development 1991, 111: 131–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sanford LP, Ormsby I, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Sariola H, Friedman R, Boivin GP, Cardell EL, et al. TGFbeta2 knockout mice have multiple developmental defects that are non-overlapping with other TGFbeta knockout phenotypes. Development 1997, 124: 2659–2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kulkarni AB, Huh CG, Becker D, Geiser A, Lyght M, Flanders KC, Roberts AB, et al. Transforming growth factor beta 1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993, 90: 770–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shull MM, Ormsby I, Kier AB, Pawlowski S, Diebold RJ, Yin M, Allen R, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature 1992, 359: 693–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Proetzel G, Pawlowski SA, Wiles MV, Yin M, Boivin GP, Howles PN, Ding J, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta 3 is required for secondary palate fusion. Nat Genet 1995, 11: 409–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frangogiannis NG. The role of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta in the infarcted myocardium. J Thorac Dis 2017, 9: S52–S63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bujak M, Frangogiannis NG. The role of TGF-beta signaling in myocardial infarction and cardiac remodeling. Cardiovasc Res 2007, 74: 184–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deten A, Holzl A, Leicht M, Barth W, Zimmer HG. Changes in extracellular matrix and in transforming growth factor beta isoforms after coronary artery ligation in rats. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2001, 33: 1191–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Annes JP, Munger JS, Rifkin DB. Making sense of latent TGFbeta activation. J Cell Sci 2003, 116: 217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Robertson IB, Horiguchi M, Zilberberg L, Dabovic B, Hadjiolova K, Rifkin DB. Latent TGF-beta-binding proteins. Matrix Biol 2015, 47: 44–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Munger JS, Sheppard D. Cross talk among TGF-beta signaling pathways, integrins, and the extracellular matrix. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2011, 3: a005017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Euler G. Good and bad sides of TGFbeta-signaling in myocardial infarction. Front Physiol 2015, 6: 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lindahl GE, Chambers RC, Papakrivopoulou J, Dawson SJ, Jacobsen MC, Bishop JE, Laurent GJ. Activation of fibroblast procollagen alpha 1(I) transcription by mechanical strain is transforming growth factor-beta-dependent and involves increased binding of CCAAT-binding factor (CBF/NF-Y) at the proximal promoter. J Biol Chem 2002, 277: 6153–6161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wipff PJ, Rifkin DB, Meister JJ, Hinz B. Myofibroblast contraction activates latent TGF-beta1 from the extracellular matrix. J Cell Biol 2007, 179: 1311–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sridurongrit S, Larsson J, Schwartz R, Ruiz-Lozano P, Kaartinen V. Signaling via the TGF-beta type I receptor Alk5 in heart development. Dev Biol 2008, 322: 208–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chablais F, Jazwinska A. The regenerative capacity of the zebrafish heart is dependent on TGFbeta signaling. Development 2012, 139: 1921–1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. DeLaughter DM, Christodoulou DC, Robinson JY, Seidman CE, Baldwin HS, Seidman JG, Barnett JV. Spatial transcriptional profile of the chick and mouse endocardial cushions identify novel regulators of endocardial EMT in vitro. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2013, 59: 196–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Han C, Choe SW, Kim YH, Acharya AP, Keselowsky BG, Sorg BS, Lee YJ, et al. VEGF neutralization can prevent and normalize arteriovenous malformations in an animal model for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia 2. Angiogenesis 2014, 17: 823–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Park SO, Wankhede M, Lee YJ, Choi EJ, Fliess N, Choe SW, Oh SH, et al. Real-time imaging of de novo arteriovenous malformation in a mouse model of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J Clin Invest 2009, 119: 3487–3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moore-Morris T, Guimaraes-Camboa N, Banerjee I, Zambon AC, Kisseleva T, Velayoudon A, Stallcup WB, et al. Resident fibroblast lineages mediate pressure overload-induced cardiac fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2014, 124: 2921–2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pinto AR, Ilinykh A, Ivey MJ, Kuwabara JT, D’Antoni ML, Debuque R, Chandran A, et al. Revisiting cardiac cellular composition. Circ Res 2016, 118: 400–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rainer PP, Hao S, Vanhoutte D, Lee DI, Koitabashi N, Molkentin JD, Kass DA. Cardiomyocyte-specific transforming growth factor beta suppression blocks neutrophil infiltration, augments multiple cytoprotective cascades, and reduces early mortality after myocardial infarction. Circ Res 2014, 114: 1246–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Edgley AJ, Krum H, Kelly DJ. Targeting fibrosis for the treatment of heart failure: a role for transforming growth factor-beta. Cardiovasc Ther 2012, 30: e30–e40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang EA, Rosen V, Cordes P, Hewick RM, Kriz MJ, Luxenberg DP, Sibley BS, et al. Purification and characterization of other distinct bone-inducing factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1988, 85: 9484–9488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang EA, Rosen V, D’Alessandro JS, Bauduy M, Cordes P, Harada T, Israel DI, et al. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein induces bone formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990, 87: 2220–2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wei Z, Salmon RM, Upton PD, Morrell NW, Li W. Regulation of bone morphogenetic protein 9 (BMP9) by redox-dependent proteolysis. J Biol Chem 2014, 289: 31150–31159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Andriopoulos B Jr., Corradini E, Xia Y, Faasse SA, Chen S, Grgurevic L, Knutson MD, et al. BMP6 is a key endogenous regulator of hepcidin expression and iron metabolism. Nat Genet 2009, 41: 482–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brand T. Heart development: molecular insights into cardiac specification and early morphogenesis. Dev Biol 2003, 258: 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Klaus A, Muller M, Schulz H, Saga Y, Martin JF, Birchmeier W. Wnt/beta-catenin and Bmp signals control distinct sets of transcription factors in cardiac progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012, 109: 10921–10926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ben-Haim N, Lu C, Guzman-Ayala M, Pescatore L, Mesnard D, Bischofberger M, Naef F, et al. The nodal precursor acting via activin receptors induces mesoderm by maintaining a source of its convertases and BMP4. Dev Cell 2006, 11: 313–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arnold SJ, Robertson EJ. Making a commitment: cell lineage allocation and axis patterning in the early mouse embryo. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2009, 10: 91–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Winnier G, Blessing M, Labosky PA, Hogan BL. Bone morphogenetic protein-4 is required for mesoderm formation and patterning in the mouse. Genes Dev 1995, 9: 2105–2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chang SA, Lee EJ, Kang HJ, Zhang SY, Kim JH, Li L, Youn SW, et al. Impact of myocardial infarct proteins and oscillating pressure on the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells: effect of acute myocardial infarction on stem cell differentiation. Stem Cells 2008, 26: 1901–1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wu X, Sagave J, Rutkovskiy A, Haugen F, Baysa A, Nygard S, Czibik G, et al. Expression of bone morphogenetic protein 4 and its receptors in the remodeling heart. Life Sci 2014, 97: 145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Merino D, Villar AV, Garcia R, Tramullas M, Ruiz L, Ribas C, Cabezudo S, et al. BMP-7 attenuates left ventricular remodelling under pressure overload and facilitates reverse remodelling and functional recovery. Cardiovasc Res 2016, 110: 331–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rodgers BD, Interlichia JP, Garikipati DK, Mamidi R, Chandra M, Nelson OL, Murry CE, et al. Myostatin represses physiological hypertrophy of the heart and excitation-contraction coupling. J Physiol 2009, 587: 4873–4886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Morissette MR, Cook SA, Foo S, McKoy G, Ashida N, Novikov M, Scherrer-Crosbie M, et al. Myostatin regulates cardiomyocyte growth through modulation of Akt signaling. Circ Res 2006, 99: 15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Poggioli T, Vujic A, Yang P, Macias-Trevino C, Uygur A, Loffredo FS, Pancoast JR, et al. Circulating growth differentiation factor 11/8 levels decline with age. Circ Res 2016, 118: 29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Loffredo FS, Steinhauser ML, Jay SM, Gannon J, Pancoast JR, Yalamanchi P, Sinha M, et al. Growth differentiation factor 11 is a circulating factor that reverses age-related cardiac hypertrophy. Cell 2013, 153: 828–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kempf T, Zarbock A, Widera C, Butz S, Stadtmann A, Rossaint J, Bolomini-Vittori M, et al. GDF-15 is an inhibitor of leukocyte integrin activation required for survival after myocardial infarction in mice. Nat Med 2011, 17: 581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sharma M, Kambadur R, Matthews KG, Somers WG, Devlin GP, Conaglen JV, Fowke PJ, et al. Myostatin, a transforming growth factor-beta superfamily member, is expressed in heart muscle and is upregulated in cardiomyocytes after infarct. J Cell Physiol 1999, 180: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Biesemann N, Mendler L, Wietelmann A, Hermann S, Schafers M, Kruger M, Boettger T, et al. Myostatin regulates energy homeostasis in the heart and prevents heart failure. Circ Res 2014, 115: 296–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Du GQ, Shao ZB, Wu J, Yin WJ, Li SH, Wu J, Weisel RD, et al. Targeted myocardial delivery of GDF11 gene rejuvenates the aged mouse heart and enhances myocardial regeneration after ischemia-reperfusion injury. Basic Res Cardiol 2017, 112: 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Harper SC, Brack A, MacDonnell S, Franti M, Olwin BB, Bailey BA, Rudnicki MA, et al. Is growth differentiation factor 11 a realistic therapeutic for aging-dependent muscle defects? Circ Res 2016, 118: 1143–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Smith SC, Zhang X, Zhang X, Gross P, Starosta T, Mohsin S, Franti M, et al. GDF11 does not rescue aging-related pathological hypertrophy. Circ Res 2015, 117: 926–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kempf T, Eden M, Strelau J, Naguib M, Willenbockel C, Tongers J, Heineke J, et al. The transforming growth factor-beta superfamily member growth-differentiation factor-15 protects the heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ Res 2006, 98: 351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Xu J, Kimball TR, Lorenz JN, Brown DA, Bauskin AR, Klevitsky R, Hewett TE, et al. GDF15/MIC-1 functions as a protective and antihypertrophic factor released from the myocardium in association with SMAD protein activation. Circ Res 2006, 98: 342–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lach-Trifilieff E, Minetti GC, Sheppard K, Ibebunjo C, Feige JN, Hartmann S, Brachat S, et al. An antibody blocking activin type II receptors induces strong skeletal muscle hypertrophy and protects from atrophy. Mol Cell Biol 2014, 34: 606–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Oh SP, Yeo CY, Lee Y, Schrewe H, Whitman M, Li E. Activin type IIA and IIB receptors mediate Gdf11 signaling in axial vertebral patterning. Genes Dev 2002, 16: 2749–2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Walker RG, Czepnik M, Goebel EJ, McCoy JC, Vujic A, Cho M, Oh J, et al. Structural basis for potency differences between GDF8 and GDF11. BMC Biol 2017, 15: 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Emmerson PJ, Wang F, Du Y, Liu Q, Pickard RT, Gonciarz MD, Coskun T, et al. The metabolic effects of GDF15 are mediated by the orphan receptor GFRAL. Nat Med 2017, 23: 1215–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hsu JY, Crawley S, Chen M, Ayupova DA, Lindhout DA, Higbee J, Kutach A, et al. Non-homeostatic body weight regulation through a brainstem-restricted receptor for GDF15. Nature 2017, 550: 255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mullican SE, Lin-Schmidt X, Chin CN, Chavez JA, Furman JL, Armstrong AA, Beck SC, et al. GFRAL is the receptor for GDF15 and the ligand promotes weight loss in mice and nonhuman primates. Nat Med 2017, 23: 1150–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Saarma M, Goldman A. Obesity: receptors identified for a weight regulator. Nature 2017, 550: 195–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Weiss A, Attisano L. The TGFbeta superfamily signaling pathway. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol 2013, 2: 47–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature 2003, 425: 577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gordon KJ, Blobe GC. Role of transforming growth factor-beta superfamily signaling pathways in human disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008, 1782: 197–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wakefield LM, Hill CS. Beyond TGFbeta: roles of other TGFbeta superfamily members in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2013, 13: 328–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Frantz S, Hu K, Adamek A, Wolf J, Sallam A, Maier SK, Lonning S, et al. Transforming growth factor beta inhibition increases mortality and left ventricular dilatation after myocardial infarction. Basic Res Cardiol 2008, 103: 485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ikeuchi M, Tsutsui H, Shiomi T, Matsusaka H, Matsushima S, Wen J, Kubota T, et al. Inhibition of TGF-beta signaling exacerbates early cardiac dysfunction but prevents late remodeling after infarction. Cardiovasc Res 2004, 64: 526–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Koitabashi N, Danner T, Zaiman AL, Pinto YM, Rowell J, Mankowski J, Zhang D, et al. Pivotal role of cardiomyocyte TGF-beta signaling in the murine pathological response to sustained pressure overload. J Clin Invest 2011, 121: 2301–2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Schneiders D, Heger J, Best P, Michael Piper H, Taimor G. SMAD proteins are involved in apoptosis induction in ventricular cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res 2005, 67: 87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Heger J, Warga B, Meyering B, Abdallah Y, Schluter KD, Piper HM, Euler G. TGFbeta receptor activation enhances cardiac apoptosis via SMAD activation and concomitant NO release. J Cell Physiol 2011, 226: 2683–2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Dandapat A, Hu CP, Li D, Liu Y, Chen H, Hermonat PL, Mehta JL. Overexpression of TGFbeta1 by adeno-associated virus type-2 vector protects myocardium from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Gene Ther 2008, 15: 415–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yang BC, Zander DS, Mehta JL. Hypoxia-reoxygenation-induced apoptosis in cultured adult rat myocytes and the protective effect of platelets and transforming growth factor-beta(1). J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1999, 291: 733–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Heger J, Peters SC, Piper HM, Euler G. SMAD-proteins as a molecular switch from hypertrophy to apoptosis induction in adult ventricular cardiomyocytes. J Cell Physiol 2009, 220: 515–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Chen Q, Chen H, Zheng D, Kuang C, Fang H, Zou B, Zhu W, et al. Smad7 is required for the development and function of the heart. J Biol Chem 2009, 284: 292–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wei LH, Huang XR, Zhang Y, Li YQ, Chen HY, Heuchel R, Yan BP, et al. Deficiency of Smad7 enhances cardiac remodeling induced by angiotensin II infusion in a mouse model of hypertension. PLoS One 2013, 8: e70195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wang J, Xu N, Feng X, Hou N, Zhang J, Cheng X, Chen Y, et al. Targeted disruption of Smad4 in cardiomyocytes results in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Circ Res 2005, 97: 821–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Heineke J, Auger-Messier M, Xu J, Sargent M, York A, Welle S, Molkentin JD. Genetic deletion of myostatin from the heart prevents skeletal muscle atrophy in heart failure. Circulation 2010, 121: 419–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Zimmers TA, Jiang Y, Wang M, Liang TW, Rupert JE, Au ED, Marino FE, et al. Exogenous GDF11 induces cardiac and skeletal muscle dysfunction and wasting. Basic Res Cardiol 2017, 112: 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Freitas-Rodriguez S, Rodriguez F, Folgueras AR. GDF11 administration does not extend lifespan in a mouse model of premature aging. Oncotarget 2016, 7: 55951–55956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Neylon CB, Bryant SM, Little PJ, Bobik A. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 regulates the expression of ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ oscillations in cardiac myocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1994, 204: 678–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kimura H, Takemura H, Imoto K, Ohshika H, Mochizuki Y. Upregulation of expression of sarcoplasmic reticulum by TGF-beta 1 in cultured rat cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol 1997, 272: H2639–H2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Carrillo C, Cafferata EG, Genovese J, O’Reilly M, Roberts AB, Santa-Coloma TA. TGF-beta1 up-regulates the mRNA for the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 1998, 44: 543–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Huntgeburth M, Tiemann K, Shahverdyan R, Schluter KD, Schreckenberg R, Gross ML, Modersheim S, et al. Transforming growth factor beta(1) oppositely regulates the hypertrophic and contractile response to beta-adrenergic stimulation in the heart. PLoS One 2011, 6: e26628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Verheule S, Sato T, Everett T, Engle SK, Otten D, Rubart-von der Lohe M, Nakajima HO, et al. Increased vulnerability to atrial fibrillation in transgenic mice with selective atrial fibrosis caused by overexpression of TGF-beta1. Circ Res 2004, 94: 1458–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Avila G, Medina IM, Jiménez E, Elizondo G, Aguilar CI. Transforming growth factor-beta1 decreases cardiac muscle L-type Ca2+ current and charge movement by acting on the Cav1.2 mRNA. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007, 292: 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Ramos-Mondragón R, Vega AV, Avila G. Long-term modulation of Na+ and K+ channels by TGF-beta1 in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. Pflugers Arch 2011, 461: 235–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kaur K, Zarzoso M, Ponce-Balbuena D, Guerrero-Serna G, Hou L, Musa H, Jalife J. TGF-beta1, released by myofibroblasts, differentially regulates transcription and function of sodium and potassium channels in adult rat ventricular myocytes. PLoS One 2013, 8: e55391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Stroud DM, Gaussin V, Burch JB, Yu C, Mishina Y, Schneider MD, Fishman GI, et al. Abnormal conduction and morphology in the atrioventricular node of mice with atrioventricular canal targeted deletion of Alk3/Bmpr1a receptor. Circulation 2007, 116: 2535–2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Bergmann O, Bhardwaj RD, Bernard S, Zdunek S, Barnabe-Heider F, Walsh S, Zupicich J, et al. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science 2009, 324: 98–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Bergmann O, Zdunek S, Felker A, Salehpour M, Alkass K, Bernard S, Sjostrom SL, et al. Dynamics of cell generation and turnover in the human heart. Cell 2015, 161: 1566–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Hsieh PC, Segers VF, Davis ME, MacGillivray C, Gannon J, Molkentin JD, Robbins J, et al. Evidence from a genetic fate-mapping study that stem cells refresh adult mammalian cardiomyocytes after injury. Nat Med 2007, 13: 970–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Choi WY, Gemberling M, Wang J, Holdway JE, Shen MC, Karlstrom RO, Poss KD. In vivo monitoring of cardiomyocyte proliferation to identify chemical modifiers of heart regeneration. Development 2013, 140: 660–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Wu CC, Kruse F, Vasudevarao MD, Junker JP, Zebrowski DC, Fischer K, Noel ES, et al. Spatially resolved genome-wide transcriptional profiling identifies BMP signaling as essential regulator of zebrafish cardiomyocyte regeneration. Dev Cell 2016, 36: 36–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Sehring IM, Jahn C, Weidinger G. Zebrafish fin and heart: what’s special about regeneration? Curr Opin Genet Dev 2016, 40: 48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Chen WP, Liu YH, Ho YJ, Wu SM. Pharmacological inhibition of TGFbeta receptor improves Nkx2.5 cardiomyoblast-mediated regeneration. Cardiovasc Res 2015, 105: 44–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ho YS, Tsai WH, Lin FC, Huang WP, Lin LC, Wu SM, Liu YR, et al. Cardioprotective actions of TGFbetaRI inhibition through stimulating autocrine/paracrine of Survivin and inhibiting Wnt in cardiac progenitors. Stem Cells 2016, 34: 445–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Chakraborty S, Sengupta A, Yutzey KE. Tbx20 promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation and persistence of fetal characteristics in adult mouse hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2013, 62: 203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Xiang FL, Guo M, Yutzey KE. Overexpression of Tbx20 in adult cardiomyocytes promotes proliferation and improves cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2016, 133: 1081–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Kikuchi K. Dedifferentiation, transdifferentiation, and proliferation: mechanisms underlying cardiac muscle regeneration in zebrafish. Curr Pathobiol Rep 2015, 3: 81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Jopling C, Sleep E, Raya M, Marti M, Raya A, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Zebrafish heart regeneration occurs by cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation. Nature 2010, 464: 606–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Zhang Y, Li TS, Lee ST, Wawrowsky KA, Cheng K, Galang G, Malliaras K, et al. Dedifferentiation and proliferation of mammalian cardiomyocytes. PLoS One 2010, 5: e12559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Wang WE, Li L, Xia X, Fu W, Liao Q, Lan C, Yang D, et al. Dedifferentiation, proliferation, and redifferentiation of adult mammalian cardiomyocytes after ischemic injury. Circulation 2017, 136: 834–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Laflamme MA, Chen KY, Naumova AV, Muskheli V, Fugate JA, Dupras SK, Reinecke H, et al. Cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells in pro-survival factors enhance function of infarcted rat hearts. Nat Biotechnol 2007, 25: 1015–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. van Laake LW, Passier R, Doevendans PA, Mummery CL. Human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes and cardiac repair in rodents. Circ Res 2008, 102: 1008–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Zeidler S, Meckbach C, Tacke R, Raad FS, Roa A, Uchida S, Zimmermann WH, et al. Computational detection of stage-specific transcription factor clusters during heart development. Front Genet 2016, 7: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Chan SS, Hagen HR, Swanson SA, Stewart R, Boll KA, Aho J, Thomson JA, et al. Development of bipotent cardiac/skeletal myogenic progenitors from MESP1+ mesoderm. Stem Cell Reports 2016, 6: 26–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Willems E, Cabral-Teixeira J, Schade D, Cai W, Reeves P, Bushway PJ, Lanier M, et al. Small molecule-mediated TGF-beta type II receptor degradation promotes cardiomyogenesis in embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 11: 242–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Mohamed TM, Stone NR, Berry EC, Radzinsky E, Huang Y, Pratt K, Ang YS, et al. Chemical enhancement of in vitro and in vivo direct cardiac reprogramming. Circulation 2017, 135: 978–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Bao X, Lian X, Hacker TA, Schmuck EG, Qian T, Bhute VJ, Han T, et al. Long-term self-renewing human epicardial cells generated from pluripotent stem cells under defined xeno-free conditions. Nat Biomed Eng 2016, 1: 0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Ebrahimi B. In vivo reprogramming for heart regeneration: a glance at efficiency, environmental impacts, challenges and future directions. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2017, 108: 61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Fonoudi H, Ansari H, Abbasalizadeh S, Larijani MR, Kiani S, Hashemizadeh S, Zarchi AS, et al. A universal and robust integrated platform for the scalable production of human cardiomyocytes from pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Transl Med 2015, 4: 1482–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Yang L, Soonpaa MH, Adler ED, Roepke TK, Kattman SJ, Kennedy M, Henckaerts E, et al. Human cardiovascular progenitor cells develop from a KDR+ embryonic-stem-cell-derived population. Nature 2008, 453: 524–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Kattman SJ, Witty AD, Gagliardi M, Dubois NC, Niapour M, Hotta A, Ellis J, et al. Stage-specific optimization of activin/nodal and BMP signaling promotes cardiac differentiation of mouse and human pluripotent stem cell lines. Cell Stem Cell 2011, 8: 228–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Zhang J, Klos M, Wilson GF, Herman AM, Lian X, Raval KK, Barron MR, et al. Extracellular matrix promotes highly efficient cardiac differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells: the matrix sandwich method. Circ Res 2012, 111: 1125–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Burridge PW, Keller G, Gold JD, Wu JC. Production of de novo cardiomyocytes: human pluripotent stem cell differentiation and direct reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 10: 16–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Burridge PW, Thompson S, Millrod MA, Weinberg S, Yuan X, Peters A, Mahairaki V, et al. A universal system for highly efficient cardiac differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells that eliminates interline variability. PLoS One 2011, 6: e18293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Elliott DA, Braam SR, Koutsis K, Ng ES, Jenny R, Lagerqvist EL, Biben C, et al. NKX2-5(eGFP/w) hESCs for isolation of human cardiac progenitors and cardiomyocytes. Nat Methods 2011, 8: 1037–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Schultz Jel J, Witt SA, Glascock BJ, Nieman ML, Reiser PJ, Nix SL, Kimball TR, et al. TGF-beta1 mediates the hypertrophic cardiomyocyte growth induced by angiotensin II. J Clin Invest 2002, 109: 787–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Davis J, Molkentin JD. Myofibroblasts: trust your heart and let fate decide. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2014, 70: 9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C, Brown RA. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2002, 3: 349–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Galli A, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast: one function, multiple origins. Am J Pathol 2007, 170: 1807–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Stempien-Otero A, Kim DH, Davis J. Molecular networks underlying myofibroblast fate and fibrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2016, 97: 153–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Kanisicak O, Khalil H, Ivey MJ, Karch J, Maliken BD, Correll RN, Brody MJ, et al. Genetic lineage tracing defines myofibroblast origin and function in the injured heart. Nat Commun 2016, 7: 12260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Tallquist MD, Molkentin JD. Redefining the identity of cardiac fibroblasts. Nat Rev Cardiol 2017, 14: 484–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Dobaczewski M, Bujak M, Li N, Gonzalez-Quesada C, Mendoza LH, Wang XF, Frangogiannis NG. Smad3 signaling critically regulates fibroblast phenotype and function in healing myocardial infarction. Circ Res 2010, 107: 418–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Khalil H, Kanisicak O, Prasad V, Correll RN, Fu X, Schips T, Vagnozzi RJ, et al. Fibroblast-specific TGF-beta-Smad2/3 signaling underlies cardiac fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2017, 127: 3770–3783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Davis J, Burr AR, Davis GF, Birnbaumer L, Molkentin JD. A TRPC6-dependent pathway for myofibroblast transdifferentiation and wound healing in vivo. Dev Cell 2012, 23: 705–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Davis J, Salomonis N, Ghearing N, Lin SC, Kwong JQ, Mohan A, Swanson MS, et al. MBNL1-mediated regulation of differentiation RNAs promotes myofibroblast transformation and the fibrotic response. Nat Commun 2015, 6: 10084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Vivar R, Humeres C, Ayala P, Olmedo I, Catalan M, Garcia L, Lavandero S, et al. TGF-beta1 prevents simulated ischemia/reperfusion-induced cardiac fibroblast apoptosis by activation of both canonical and non-canonical signaling pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1832: 754–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Chua CC, Chua BH, Zhao ZY, Krebs C, Diglio C, Perrin E. Effect of growth factors on collagen metabolism in cultured human heart fibroblasts. Connect Tissue Res 1991, 26: 271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Stawowy P, Margeta C, Kallisch H, Seidah NG, Chretien M, Fleck E, Graf K. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase MT1-MMP/MMP-2 in cardiac fibroblasts by TGF-beta1 involves furin-convertase. Cardiovasc Res 2004, 63: 87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Tan SM, Zhang Y, Connelly KA, Gilbert RE, Kelly DJ. Targeted inhibition of activin receptor-like kinase 5 signaling attenuates cardiac dysfunction following myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2010, 298: H1415–H1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Leask A. Getting to the heart of the matter: new insights into cardiac fibrosis. Circ Res 2015, 116: 1269–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Kuwahara F, Kai H, Tokuda K, Kai M, Takeshita A, Egashira K, Imaizumi T. Transforming growth factor-beta function blocking prevents myocardial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction in pressure-overloaded rats. Circulation 2002, 106: 130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Engebretsen KV, Skardal K, Bjornstad S, Marstein HS, Skrbic B, Sjaastad I, Christensen G, et al. Attenuated development of cardiac fibrosis in left ventricular pressure overload by SM16, an orally active inhibitor of ALK5. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2014, 76: 148–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Lefer AM, Tsao P, Aoki N, Palladino MA Jr. Mediation of cardioprotection by transforming growth factor-beta. Science 1990, 249: 61–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Sun B, Huo R, Sheng Y, Li Y, Xie X, Chen C, Liu HB, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein-4 mediates cardiac hypertrophy, apoptosis, and fibrosis in experimentally pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension 2013, 61: 352–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Chen X, Xu J, Jiang B, Liu D. Bone morphogenetic protein-7 antagonizes myocardial fibrosis induced by atrial fibrillation by restraining transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta)/Smads signaling. Med Sci Monit 2016, 22: 3457–3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Kramann R, Schneider RK, DiRocco DP, Machado F, Fleig S, Bondzie PA, Henderson JM, et al. Perivascular Gli1+ progenitors are key contributors to injury-induced organ fibrosis. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 16: 51–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Markkanen JE, Rissanen TT, Kivela A, Yla-Herttuala S. Growth factor-induced therapeutic angiogenesis and arteriogenesis in the heart—gene therapy. Cardiovasc Res 2005, 65: 656–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Heil M, Eitenmuller I, Schmitz-Rixen T, Schaper W. Arteriogenesis versus angiogenesis: similarities and differences. J Cell Mol Med 2006, 10: 45–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Lahteenvuo JE, Lahteenvuo MT, Kivela A, Rosenlew C, Falkevall A, Klar J, Heikura T, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-B induces myocardium-specific angiogenesis and arteriogenesis via vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1- and neuropilin receptor-1-dependent mechanisms. Circulation 2009, 119: 845–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Carmeliet P. Mechanisms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Nat Med 2000, 6: 389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Gupta R, Tongers J, Losordo DW. Human studies of angiogenic gene therapy. Circ Res 2009, 105: 724–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Carmeliet P. VEGF gene therapy: stimulating angiogenesis or angioma-genesis? Nat Med 2000, 6: 1102–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Beets K, Huylebroeck D, Moya IM, Umans L, Zwijsen A. Robustness in angiogenesis: notch and BMP shaping waves. Trends Genet 2013, 29: 140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Morrell NW, Bloch DB, ten Dijke P, Goumans MJ, Hata A, Smith J, Yu PB, et al. Targeting BMP signalling in cardiovascular disease and anaemia. Nat Rev Cardiol 2016, 13: 106–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Mouillesseaux KP, Wiley DS, Saunders LM, Wylie LA, Kushner EJ, Chong DC, Citrin KM, et al. Notch regulates BMP responsiveness and lateral branching in vessel networks via SMAD6. Nat Commun 2016, 7: 13247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Beets K, Staring MW, Criem N, Maas E, Schellinx N, de Sousa Lopes SM, Umans L, et al. BMP-SMAD signalling output is highly regionalized in cardiovascular and lymphatic endothelial networks. BMC Dev Biol 2016, 16: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Morabito CJ, Kattan J, Bristow J. Mechanisms of embryonic coronary artery development. Curr Opin Cardiol 2002, 17: 235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Luttun A, Carmeliet P. De novo vasculogenesis in the heart. Cardiovasc Res 2003, 58: 378–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Smart N, Dube KN, Riley PR. Coronary vessel development and insight towards neovascular therapy. Int J Exp Pathol 2009, 90: 262–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Patterson AJ, Zhang L. Hypoxia and fetal heart development. Curr Mol Med 2010, 10: 653–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Sanchez-Elsner T, Botella LM, Velasco B, Corbi A, Attisano L, Bernabeu C. Synergistic cooperation between hypoxia and transforming growth factor-beta pathways on human vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression. J Biol Chem 2001, 276: 38527–38535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]