Conventionally, functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) as classified by the Rome IV Criteria refer to a group of chronic conditions categorized by gut symptoms that arise via multiple pathophysiological processes, conceptualized as disorders of gut-brain interactions1. Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms in inflammatory bowel disease and gastric or colon cancer also arise through gut-brain interactions (no brain, no pain), so in this sense, FGIDs are not unique. Gut pathology is considered to be absent in the FGIDs, and the underlying aetiology is accepted to be unknown1. However, emerging evidence is challenging the current paradigm there is no pathology and no known aetiology. In particular, a microbial pathogenesis may be more important than has been previously appreciated. While there are 33 adult and 20 paediatric FGIDs classified in Rome IV1, among the most prevalent are the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), characterized by abdominal pain, bowel dysfunction and often bloating and functional dyspepsia (FD), characterized by early satiety, postprandial fullness or epigastric pain2,3. Here we discuss the emerging evidence that microbes and inflammation play an aetiopathogenic role in IBS and FD.

Psychological co-morbidity is common in FGIDs; however, the available evidence confirms that this association is largely not explained by healthcare-seeking behaviour but instead is an intimate characteristic of the disorder in a majority of cases4. Recently, prospective epidemiological studies have suggested that about 50 per cent of patients with an FGID have a brain-gut-driven condition, where psychological symptoms are followed at a later time by the new onset of gut symptoms, suggesting that there may be a more dominant brain to gut pathway5. On the other hand, in the remaining 50 per cent of cases, gut symptoms begin first followed by new-onset psychological alterations, indicating a gut-to-brain-driven disease process rather than a primary brain disorder5. This is further supported by a strong link between immune activation (e.g. through increased tumour necrosis factor alpha levels) and the severity of psychological co-morbidities present in these disorders2,3,5,6. If the gut is key to the onset of many with FGIDs, identifying the disease pathways may permit treatments that target cure rather than present management which is directed at symptom control, as the gut is more accessible than the brain and the gut microenvironment can be locally manipulated.

The IBS aggregates strongly in families suggesting that genes and environment both play a role2. A genetic mutation in the sodium channel gene has been identified in IBS with particular relevance to constipation and may explain about two per cent of cases with IBS7. However, twin data point to the environment being dominant, not only in dyspepsia but also in IBS8. One environmental gut cause of FGIDs is well established, namely food-borne infections, which may affect one in six people annually9. IBS can arise de novo after bacterial enteritis2. While post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS) has been well recognized, post-infectious FD has also been observed10. A meta-analysis concluded that PI-IBS may occur after bacterial, protozoal or parasitic enteritis, and the risk is increased in people with psychological distress and female gender, if antibiotics are used to treat the infection, with protozoal or parasitic disease, and if there is more severe enteritis9. Emerging evidence suggests that PI-IBS may be much more common than is generally appreciated based on cytotoxic lethal binding toxin antibody levels (a marker of previous bacterial enteritis) in IBS with diarrhoea11. A modelling study suggested that based on the attack rate of gastroenteritis and risk of IBS, nearly 10 per cent of the US population will be affected, closely matching the community prevalence of IBS documented in multiple population-based surveys12. It has become apparent incident FD may also arise after bacterial enteritis, and up to one-third of cases develop both IBS and FD; the odds of FD after acute enteritis is over two-fold increased10.

Although the inflammation may heal after acute infection, low-grade chronic intestinal inflammation with immune activation is documented to occur in a subset of FGID cases. In IBS, increased ileocolonic mast cells have been observed in subsets although the literature is mixed and clearly many IBS cases have no detectable increase in mast cells13.

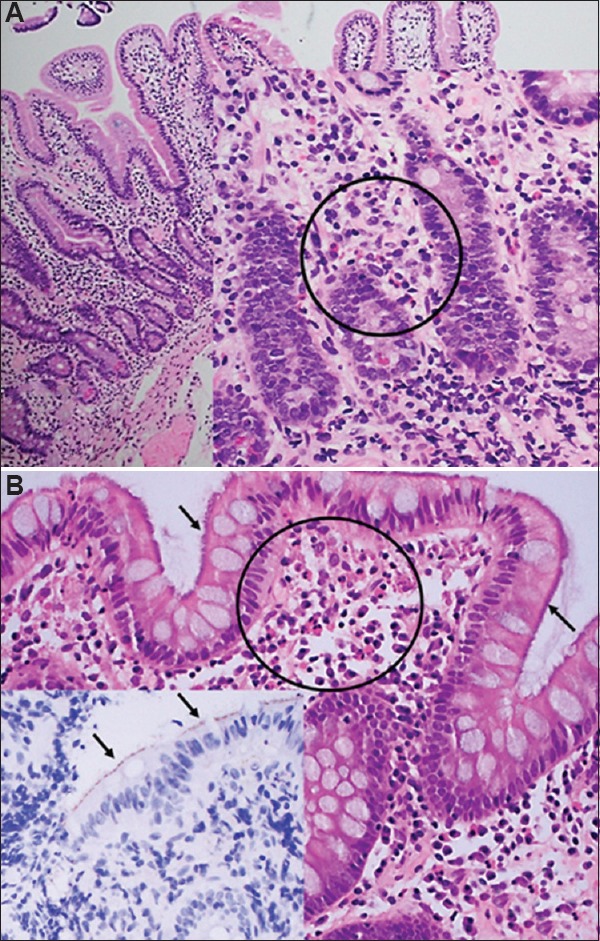

In FD, duodenal eosinophilia (typically more than 22 eosinophils per 5 high-power fields in the second portion of the duodenum being the diagnostic cut-off) has been consistently documented to be associated with early satiety and postprandial fullness13 (Figure). Further, circulating small intestinal homing T-cells have been observed in IBS and FD, implicating ongoing low-grade intestinal inflammation in the disease process13. It has therefore, been postulated that the extent of initial acute intestinal inflammation after infection may sensitize the intestine and determine the disease phenotype; enteritis localized to the upper small intestine may be more likely to lead to FD, while more distal enteritis or enterocolitis may lead to IBS2. After intestinal infection, tropical sprue may develop based on small intestinal biopsy evaluation, and it is possible that some cases of PI-IBS actually arise from a subtle malabsorption syndrome; the prevalence of tropical sprue in IBS is currently unknown14.

Figure.

Abnormal histopathology on haematoxylin and eosin staining of duodenum and colon biopsies in functional gastrointestinal disorders: (A) Duodenal biopsy showing eosinophilia in functional dyspepsia (×20). Haematoxylin and eosin stain showing clusters of eosinophils, circled (×40). (B) Biopsy of sigmoid colon with spirochaetosis, hazy blue ‘fringe’ (arrows) and clusters of subepithelial eosinophils (circled) in an irritable bowel syndrome case (×40). Haematoxylin and eosin stain inset (×40) showing immunocytochemistry for Spirochaetes on surface of epithelium (arrows).

What are the intestinal microenvironmental abnormalities that can lead to chronic gut symptoms either after acute infection or following other insults? One candidate is the presence of abnormal amounts of colonic bacteria in the small intestine presumably because local intestinal stasis arises, termed (vaguely) small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). Conventionally, SIBO has been diagnosed based on culture of duodenal aspirates (a difficult technique to perform without specimen contamination) with a cut-off of more than 105 coliforms on culture15. However, it has been argued that more than 103 coliforms in the duodenum are abnormal in health and this should be the cut-off applied for SIBO15. An alternative approach has used lactulose or glucose hydrogen breath testing to indirectly identify increased coliforms in the upper small intestine, where an early rise in hydrogen excretion indicates bacterial breakdown of the sugar substrate (rather than a hydrogen rise later as normally occurs when the substrate reaches the caecum)15. However, breath testing is influenced by transit time which can be altered in IBS2,15. Simply investigating for SIBO fails to consider all other components of the intestinal microbiome so whether SIBO is really a cause of IBS is unclear.

Alterations of the intestinal microbiome are linked to several chronic human diseases although cause and effect is not yet well established16. Rather than the Koch paradigm of 'one organism, one disease', current research has focussed on identifying gut dysbiosis in disease including IBS and more recently FD. Most of the microbiome work in IBS has concentrated on dysbiosis in stool; a major limitation as it seems more likely that the mucosal-associated microbiome (MAM) will be key to any gut microenvironmental dysfunction or systemic immune activation13. Studies of the colonic MAM have described changes in IBS, but a consistent microbial signature has not been identified17. In FD, our work has shown that the duodenal microbiome differs from that in health18.

Supporting the microbial hypothesis for IBS and FD, the non-absorbable antibiotic rifaximin has been shown to improve symptoms in those with IBS-diarrhoea or mixed bowel habit, but the gain over placebo while consistent in the phase III trials is modest19. Further, the mechanism of action is unknown although rifaximin may modestly decrease stool microbial richness. A trial in Gulf War Veterans did not show any benefit of rifaximin on SIBO20. In one randomized trial, rifaximin was found superior to placebo in improving symptoms of FD although the mechanism of action was uncertain21. Postulating correcting colonic dysbiosis may improve IBS; faecal microbial transplant (FMT) has been trialed. The largest trial to date in 52 patients observed despite altering the stool microbiome with FMT, greater symptom improvement on placebo occurred versus the active intervention. Further research in IBS subgroups is needed before drawing definitive conclusions22.

Focusing on changes in intestinal ecology alone in FGIDs may be limiting and misleading. We know that chronic peptic ulceration and gastric cancer are caused by a single organism, Helicobacter pylori, even though the gastric microbiome is greatly perturbed in the presence of this chronic infection23. We, for example, have identified a chronic colonic bacterial infection, colonic spirochetosis, in two per cent of individuals in Sweden24 (Figure). Further, the bacteria are associated with subtle colonic pathology previously missed (increased colonic eosinophils) but now confirmed in two independent studies24,25, and with an over 3-fold increased risk of IBS with diarrhoea, an association overlooked in previous studies which mistakenly concluded colonic spirochetosis as a commensal24,25. If colonic spirochetosis proves to be a cause of IBS and diarrhoea, then cure of this subset may be achievable, a hypothesis we are actively pursuing. Blastocystis is another candidate organism that may account for a small subset with IBS, but randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm multiple observational reports; on the other hand, Dientamoeba fragilis is probably a commensal26.

In conclusion, acute and chronic infections, and alterations in the gut microbial environment may be important in the pathogenesis of IBS and FD. Currently, FGIDs are diagnosed by applying symptom criteria (Rome IV)1, but we speculate that lumping Rome criteria positive cases together in clinical trials is misleading as demonstrated by the small benefit over placebo of all currently FDA-approved therapies for IBS (around 10%); identical symptom complexes may arise from very different gut-brain or brain-gut disease processes, including probably through microbial-driven pathways2,3. Peptic ulcer is not primarily a disease of stress or abnormal gut-brain interactions or a disturbed microbiome; most commonly, it is a bacterial disease. If microbes also play a causal or initiating role in FGIDs such as IBS or FD as seems increasingly likely, the term functional is a misnomer and will be discarded.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Schmulson MJ, Drossman DA. What is new in Rome IV. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:151–63. doi: 10.5056/jnm16214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford AC, Lacy BE, Talley NJ. Irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2566–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1607547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talley NJ, Ford AC. Functional dyspepsia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:896. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1515497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Boyce PM. Does psychological distress modulate functional gastrointestinal symptoms and health care seeking? A prospective, community cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:789–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones MP, Tack J, Van Oudenhove L, Walker MM, Holtmann G, Koloski NA, et al. Mood and anxiety disorders precede development of functional gastrointestinal disorders in patients but not in the population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1014–20.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liebregts T, Adam B, Bredack C, Röth A, Heinzel S, Lester S, et al. Immune activation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:913–20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beyder A, Mazzone A, Strege PR, Tester DJ, Saito YA, Bernard CE, et al. Loss-of-function of the voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.5 (channelopathies) in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1659–68. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lembo A, Zaman M, Jones M, Talley NJ. Influence of genetics on irritable bowel syndrome, gastro-oesophageal reflux and dyspepsia: A twin study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1343–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klem F, Wadhwa A, Prokop LJ, Sundt WJ, Farrugia G, Camilleri M, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes of irritable bowel syndrome after infectious enteritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1042–1054.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pike BL, Porter CK, Sorrell TJ, Riddle MS. Acute gastroenteritis and the risk of functional dyspepsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1558–63. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pimentel M, Morales W, Rezaie A, Marsh E, Lembo A, Mirocha J, et al. Development and validation of a biomarker for diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome in human subjects. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah ED, Riddle MS, Chang C, Pimentel M. Estimating the contribution of acute gastroenteritis to the overall prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;18:200–4. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2012.18.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burns G, Carroll G, Mathe A, Horvat J, Foster P, Walker MM, et al. Evidence for local and systemic immune activation in functional dyspepsia and the irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0377-0. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0377-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghoshal UC, Gwee KA. Post-infectious IBS, tropical sprue and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: The missing link. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:435–41. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rezaie A, Buresi M, Lembo A, Lin H, McCallum R, Rao S, et al. Hydrogen and methane-based breath testing in gastrointestinal disorders: The North American Consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:775–84. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinha R, Ahsan H, Blaser M, Caporaso JG, Carmical JR, Chan AT, et al. Next steps in studying the human microbiome and health in prospective studies, Bethesda, MD, May 16-17, 2017. Microbiome. 2018;6:210. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0596-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menees S, Chey W. The gut microbiome and irritable bowel syndrome. F1000Res. 2018;7 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.14592.1. pii: F1000 Faculty Rev-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhong L, Shanahan ER, Raj A, Koloski NA, Fletcher L, Morrison M, et al. Dyspepsia and the microbiome: Time to focus on the small intestine. Gut. 2017;66:1168–9. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ford AC, Harris LA, Lacy BE, Quigley EMM, Moayyedi P. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics and antibiotics in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48:1044–60. doi: 10.1111/apt.15001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuteja AK, Talley NJ, Stoddard GJ, Verne GN. Double-blind placebo-controlled study of rifaximin and lactulose hydrogen breath test in gulf war veterans with irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:838–45. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan VP, Liu KS, Lam FY, Hung IF, Yuen MF, Leung WK, et al. Randomised clinical trial: Rifaximin versus placebo for the treatment of functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:767–76. doi: 10.1111/apt.13945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halkjær SI, Christensen AH, Lo BZS, Browne PD, Günther S, Hansen LH, et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation alters gut microbiota in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: Results from a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Gut. 2018;67:2107–15. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker MM, Talley NJ. Review article: Bacteria and pathogenesis of disease in the upper gastrointestinal tract – Beyond the era of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:767–79. doi: 10.1111/apt.12666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walker MM, Talley NJ, Inganäs L, Engstrand L, Jones MP, Nyhlin H, et al. Colonic spirochetosis is associated with colonic eosinophilia and irritable bowel syndrome in a general population in Sweden. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:277–83. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodsall TM, Talley NJ, Rassam L, Wood NK, Zala A, Jones M, et al. Unique pathology of colonic spirochaetosis characterised by mucosal eosinophilia is linked to diarrhoea and IBS. Gut. 2017;66:978–9. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rostami A, Riahi SM, Haghighi A, Saber V, Armon B, Seyyedtabaei SJ, et al. The role of Blastocystis sp. and Dientamoeba fragilis in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasitol Res. 2017;116:2361–71. doi: 10.1007/s00436-017-5535-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]