Abstract

Infectious diseases remain as the major causes of human and animal morbidity and mortality leading to significant healthcare expenditure in India. The country has experienced the outbreaks and epidemics of many infectious diseases. However, enormous successes have been obtained against the control of major epidemic diseases, such as malaria, plague, leprosy and cholera, in the past. The country's vast terrains of extreme geo-climatic differences and uneven population distribution present unique patterns of distribution of viral diseases. Dynamic interplays of biological, socio-cultural and ecological factors, together with novel aspects of human-animal interphase, pose additional challenges with respect to the emergence of infectious diseases. The important challenges faced in the control and prevention of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases range from understanding the impact of factors that are necessary for the emergence, to development of strengthened surveillance systems that can mitigate human suffering and death. In this article, the major emerging and re-emerging viral infections of public health importance have been reviewed that have already been included in the Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme.

Keywords: Avian influenza, CCHF, emerging, India, Nipah virus, re-emerging, respiratory viral infections, rotavirus, viral diseases

Introduction

The emergence of novel human pathogens and re-emergence of several diseases are of particular concerns in the current decade. At a basic level, emerging infections can be defined as those diseases whose incidence has been found to be increased within recent decades or which have threatened to increase in the future. Such emergences are often detection/spread of pathogen in newer areas, recognition of the presence of diseases that have been present in a population albeit as undetected entities, or due to the realization of an infectious aetiology in already established diseases1. Several factors underlie the emergence of such diseases, including increasing population, poverty and malnutrition, increased domestic and global connectivity, economic factors leading to population migration, social practices, prevalence of immunosuppressive diseases, unplanned urbanization, deforestation and change in agricultural practices such as mixed farming2. Genetic alterations in pathogens have also been responsible for such outbreaks, to a significant extent3.

Estimates indicate that about 60 per cent of infectious diseases and 70 per cent of emerging infections of humans are zoonotic in origin, with two-thirds originating in wildlife4. Habitat destruction due to unplanned urbanization has placed humans at increasing contact with animal and arthropod vectors of viral infections. Such interactions have been one of the major causes for increased human susceptibility to infections by novel pathogens, in the absence of specific immunity in these populations.

Respiratory viral infections, arboviral infections and bat-borne viral infections represent three major categories of emerging viral infections in India. Infectious aerosols of the tracheobronchial tree represent efficient means for spread of viral pathogens affecting the respiratory tract. Pandemic influenza H1N1pdm09, highly pathogenic avian influenza (AI) infection (H5N1) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronaviruses (MERS-CoV) represent three pathogens posing severe threat in this category5,6. Arthropod-borne viruses have consistently been the reason of emerging and re-emerging diseases in the Indian subcontinent, including Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF), dengue, chikungunya, Japanese encephalitis and Kyasanur forest disease (KFD). The major arboviral pathogens of humans belong to the three genera of Flavivirus, Alphavirus and Nairovirus. Several bat-borne viruses have also come into prominent notice, best exemplified by Nipah viral disease, severe fever with thrombocytopenia virus (SFTV), as well as Ebola viral disease.

A consistent theme in the infectious disease landscape of the country has been the periods of quiescence of several pathogens following their initial discovery, only to be followed by their reappearance, often in more virulent forms. This is best exemplified by arboviral infections such as chikungunya and Zika. Several parts of the country have witnessed the re-emergence of chikungunya, an arboviral illness characterized by debilitating and prolonged arthralgia, since 20067. Following the initial outbreaks during 1963 and 1973, the illness showed a long period of quiescence before making a re-appearance8. In contrast to the early outbreaks which were caused by Asian strains of the virus, the East African strains of chikungunya virus were responsible for the explosive outbreaks of chikungunya during 20067. Most parts of the country abound with substantial populations of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, which are competent vectors for dengue, chikungunya and Zika viruses, which remain as global threats9,10. Although serological studies conducted in the 1960s showed the circulation of Zika virus in the country11, a detailed understanding of the disease burden and its impact did not come forth till the explosive outbreaks began in Brazil in 201511. Four cases of Zika viral infection were subsequently identified and reported from India (3 from Gujarat and 1 from Tamil Nadu), and no Zika-associated microcephaly cases have been identified in the country, till date (NIV, unpublished data).

There have also been cases of discovery of novel pathogens in the country. The examples include Chandipura virus (CHPV), CCHF virus and KFD virus (KFDV). These viruses were identified during the 1950s-1960s12,13,14, but their pathogenic and public health significance remained unexplored for a long time. Several of these infections take a heavy toll on the animal husbandry and agricultural industry. The economic costs associated with such infections can be heavy as can be inferred from the high costs of medical and intensive care, days of productive work lost, impact on travel and tourism, ban on export of agricultural produce from affected regions, etc. The psychological impact of such outbreaks and their sequelae has also not been systematically evaluated in the country.

The Department of Health Research (DHR), Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India, made a vision in 2013 to establish and strengthen the network of laboratories across the country to create infrastructure for timely identification of viruses causing outbreaks or related to significant morbidity/mortality which are important at public health level. This network of Virus Research and Diagnostic Laboratory (VRDLN) is also intended to provide virological diagnosis to patients attending tertiary health facilities (medical colleges) and thereby help in generating surveillance data on common viral diseases from different parts of the country. The detailed list of VRDLN currently functional in India is available (http://112.133.207.124:82/vdln/vdls.php).

The situation of emerging public health infections in India was last reviewed by Dikid et al1 in 2013. However, the country has witnessed many notable changes with regard to infectious diseases in the past 4-5 years, prompting a re-look into the scenario. The present review attempts to provide an updated review on the topic.

Emerging viral infections identified as public health threats

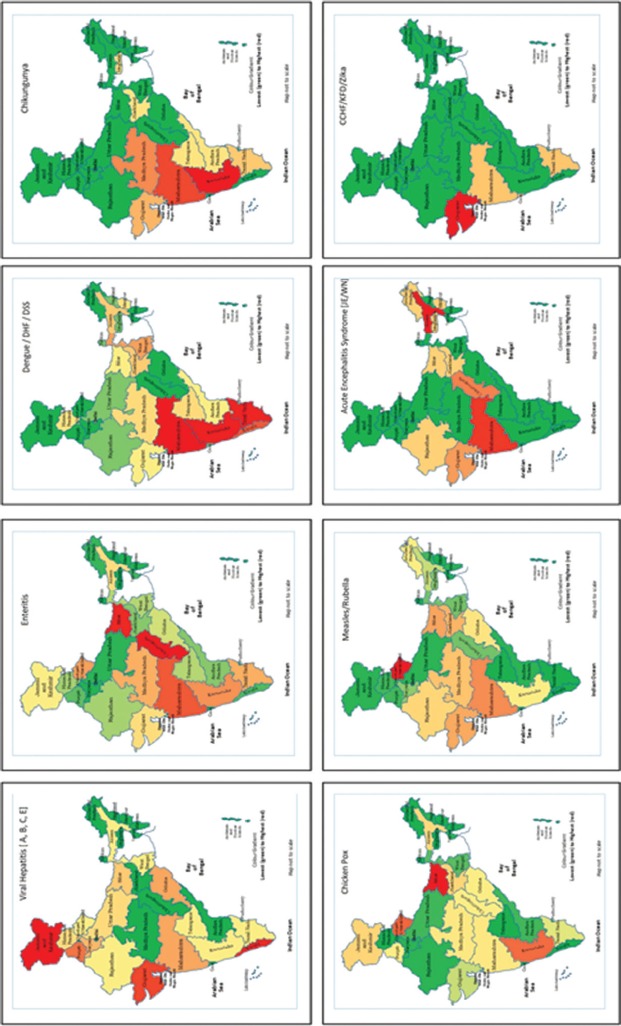

Viral pathogens are known to cause outbreaks that have epidemic and pandemic potential. The Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme (IDSP) is a laboratory-based, IT-enabled system in the country for surveillance of epidemic-prone diseases15. During 2017, the IDSP network reported a total of 1683 outbreaks of such diseases. The analysis of data showed that 71 per cent of these outbreaks were caused by viral pathogens, while 29 per cent were due to non-viral pathogens. Nearly 72,000 individuals were affected in these outbreaks, and amongst them, 60 per cent had a viral aetiology. Data also revealed that febrile rash syndromes (including measles, rubella and chickenpox) contributed 30 per cent of the outbreaks, while gastroenteritis and arboviral diseases contributed 20 and 17 per cent, respectively15 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Disease-wise reported outbreaks in India. CCHF, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever; KFD. Kyasanur forest disease; ARI, acute respiratory infection; JE, Japanese encephalitis; WN, West Nile; DHF, dengue hemorrhagic fever; DSS, Dengue Shock syndrome. Source: Ref. 15.

Majority of the reported outbreaks occurred in the Western part of the country (Fig. 2)15. It is likely that the reported outbreaks represent only a part of the actual disease burden and only the symptomatic and/or geographically clustered cases identified by the health facility would have been covered in the reports. Subclinical and sporadic infections, as well as those not identified by the health facility, are often missed by the surveillance systems. The proportion of reported outbreaks is directly related to the public health infrastructure and surveillance network, with outbreak alerts originating most efficiently from those States with well-functioning public health infrastructure and disease surveillance systems.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of State and district-wise outbreaks of public health priority viral diseases. Abbreviations are as given in Fig. 1. Source: Ref. 15.

The National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme (NVBDCP) undertakes the surveillance for the vector-borne diseases in the country. This Programme focusses on the prevention and control of diseases, which include malaria, dengue, chikungunya, Japanese encephalitis, kala-azar as well as lymphatic filariasis. The epidemiology of these diseases is known to vary with ecology, vector bionomics, as well as economic, socio-cultural and behavioural factors. Regular monitoring and evaluation would be critical to the overall success of the Programme. Arboviral infections, including dengue and chikungunya, have shown an upsurge in recent years, particularly in the urban community of the country16. Climatological factors and favourable environment conferring longevity of the vector mosquitoes, especially of Aedes species, are thought to underlie this. Concerted efforts toward the control of vectors, including mosquitoes with the help of community participation and by enhancing the community awareness, would be critical to curtail the disease transmission.

Impact of mass gatherings and emerging viral infections

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mass gatherings as occasions, which are organized or are spontaneous, that pulls large numbers of pool of people for straining the planning as well as response resources in the community, city or nation hosting that particular event. In addition to religious congregations, these events may be held in the sports, socio-cultural or political contexts17. The religious Kumbh Mela, held every 12 years in Uttar Pradesh in India, is considered as one of the biggest human mass gatherings on earth18. The other examples of religious mass gatherings in India include the Maha Pushkaram festival in Andhra Pradesh (last held in 2015 and attended by 48.1 million people in Andhra Pradesh and 57 million people in Telangana), annual pilgrimage to Sabarimala temple in Pathanamthitta district of Kerala (attended by 45-50 million devotees every year) and Velankanni, the biggest Catholic pilgrimage centre in India (visited by around 3 million people from late August to early September), Mahamaham in Kumbakonam in Tamil Nadu (last held on February 22, 2016, attended by one million people)19. Similar events of other religious denominations attended by comparatively lesser numbers of pilgrims are also observed in India with fervor. Such opportunities create situations for human proximity within very close distances and the challenges they present to the maintenance of sanitation. These gatherings create considerable public health concern. Transmission of respiratory and gastrointestinal infections remains major concerns during such large-scale assemblies. The outbreaks of infectious diseases have occurred during several of these events, best exemplified by the outbreak of cholera at the Kumbh Mela festival in 1817, which spawned the Asiatic cholera pandemic (1817-1824) through the returned, infected pilgrims20. These assume additional importance in the wake of the emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, including that due to viruses. Large numbers of Muslim followers return from the Hajj and Umrah pilgrimage every year, there have been concerns that they might acquire infections with MERS-CoV during the event and subsequently lead to its introduction in India. However, no case of MERS-CoV infection has been detected in the country so far though reports have indicated the spread of influenza through infected, returning pilgrims21. It would seem likely that these large-scale gatherings may provide platforms for exchange of genomic material and thereby evolution of pathogens, including viruses.

Nosocomial transmission and emerging infections

Institutionalized care of vulnerable people with compromised immune systems (e.g. those receiving cancer chemotherapy or undergone the procedure of transplantation either of solid organ or hematopoietic stem cell, diabetics, elderly, pregnant women and pre-term babies) may present opportunities for transmission of viral infections. Use/sharing of contaminated instruments for injections and practices such as body piercing, tattooing and acupuncture may result in heightened risk for transmission of infections, including hepatitis-C virus (HCV), hepatitis-B virus (HBV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Appreciable risks also exist at dental clinics, haemodialysis units, etc. where sterilization/disinfection practices for patient care instruments are not followed stringently. Healthcare staff faces a real risk for the acquisition of several viral infections, including HBV, HCV, HIV, rubella, viral haemorrhagic fevers (CCHF), encephalitic infections such as rabies and Nipah. Hospital-associated transmission of infection was a prominent finding during the outbreaks of Nipah infection in West Bengal22 and Kerala States, in which several healthcare staff fell victims to the infection. The details of emerging/re-emerging viral infections in India and new viruses are provided in Table I.

Table I.

Emerging/re-emerging viral infections in India and new viruses

| Family | Viruses | Probable/mode of transmission | Outbreak potential | Biosafety-risk group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bunyaviridae | Ganjam virus | Tick-borne | Yes* | 2 |

| Bhanja virus | Tick-borne | Yes* | 2 | |

| SFTS virus | Tick-borne | Yes | 4 | |

| Chobar Gorge virus | Tick-borne | No | 2 | |

| EEV | Arthropod-borne | No | 2 | |

| Cat Que virus | Arthropod-borne | Yes* | 2 | |

| Kaisodi virus | Tick-borne | Yes* | 2 | |

| Umbre virus | Arthropod-borne | Yes* | 2 | |

| Oya virus=ingwavuma virus | Arthropod-borne | No | 2 | |

| Chittoor virus | Tick-borne | Yes* | 2 | |

| Thottapalayam virus | Rodent-borne | No | 2 | |

| Nairoviridae | CCHFs virus | Tick-borne, human to human | Yes | 4 |

| Flaviviridae | Yellow fever | Arthropod-borne | Yes | 4 |

| Zika virus | Arthropod-borne, mother to child, sexual route | Yes | 2 | |

| KFD | Tick-borne | Yes | 4 | |

| JE | Arthropod-borne | Yes | 2 | |

| Dengue | Arthropod-borne | Yes | 2 | |

| Bagaza virus | Arthropod-borne | Yes* | 2 | |

| Paramyxoviridae | Influenza - (H3N2) v alias | Air-borne | Yes | 3 |

| Influenza -Avian (H5N1) | Air-borne | Yes | 4 | |

| RSV | Air-borne | Yes | 2 | |

| Quaranfil virus | Tick-borne | Yes* | 2 | |

| Parainfluenza 1-4 | Air-borne | Yes* | 2 | |

| Enterovirus-D68 | Air-borne | Yes | 2 | |

| Paramyxoviridae | Nipah virus | Human to human | Yes | 4 |

| Direct contact/consumption of infected bat/fruit infected with bat | ||||

| Picornaviridae | Human rhinovirus A, B and C | Air-borne | Yes | 2 |

| Hand, foot and mouth disease | Direct contact, faeco-oral route | Yes | 2 | |

| Coxsackie-A21 virus | Faeco-oral route | Yes | 2 | |

| Coxsackie-A10 virus | Faeco-oral route | Yes | 2 | |

| Sapoviruses | Faeco-oral route | Yes | 2 | |

| Rota | Faeco-oral route | Yes | 2 | |

| Polio and non-polio flaccid paralysis | Faeco-oral route | Yes | 3 | |

| Caliciviridae | Noroviruses | Faeco-oral route | Yes | 2 |

| Hepadnaviridae | Hepatitis KIs virus new and vaccine escape mutants of HBV | Blood-borne | Yes | 2 |

| Togaviridae | Rubella virus | Ai-borne | Yes | 2 |

| Chikungunya virus | Arthropod-borne | Yes | 2 | |

| Poxviridae | Buffalopox virus (orthopoxvirus) | Direct contact | Yes | 2 |

| Parvoviridae | Human parvovirus-4 | Parenteral transmission? | Yes | 2 |

| Arenaviridae | LCMV | Rodent-borne | Yes* | 3 |

| Herpesviridae | CMV | Direct contact | Yes | 2 |

| Chickenpox (varicella) VZV | Air-borne, direct contact | Yes | 2 | |

| Rhabdoviridae | Chandipura virus | Arthropod-borne | Yes | 3 |

| Reoviridae | Kammavanpettai virus (orbiviruses) | Tick-borne | No | Unknown |

*May cause epidemic; however, no epidemic has been reported. Unknown: No clear information on the risk assessment available. SFTS, severe fever thrombocytopenia syndrome; EEV, equine encephalosis virus; CCHFs, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fevers; KFD, kyasanur forest disease; JE, Japanese encephalitis; LCMV, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus; CMV, cytomegalovirus; VZV, varicella-zoster virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; HBV, hepatitis-B virus

Source: Refs 5,10,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55

Laboratory accidents/lapses in biosafety practices

Neglect of laboratory biosafety requirements as well as laboratory accidents may also lead to the occurrences of emerging/re-emerging infections. Recently, there was a report on the development of buffalopox (BPX) lesions on the palm of a biomedical researcher following a shrapnel injury, warranting surgical treatment and leading to delayed healing56. Such reports, though infrequent, emphasize the need for stringent adherence to biosafety guidelines to be observed in research involving viral agents with human pathogenic potential.

Some viral pathogens that have gained particular attention in recent years are discussed below:

(i) Enteroviruses (EVs): The EVs are small, non-enveloped, positive-stranded RNA viruses of the family Picornaviridae, which remain as the neglected and re-emerging viral pathogens in our country. Originally classified into four groups based on pathogenetic properties (Coxsackie A viruses, Coxsackie B viruses, polioviruses and echoviruses), these are more accurately classified by molecular typing employing nucleotide sequencing of the VP1 region of their genome21. More than 300 EV types have been described57. The disease spectrum associated with these includes acute flaccid paralysis, meningitis, encephalitis, myocarditis, acute haemorrhagic conjunctivitis, myocarditis, pericarditis, type 1 diabetes mellitus, myositis, respiratory tract infections and exanthems such as the hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD)24. Overlapping clinical presentations of enteroviral infections makes it difficult to arrive at an aetiological diagnosis without laboratory confirmation. Rao24 reported a positivity of 35 per cent for non-polio EV (NPEV) infections amongst children with non-polio acute flaccid paralysis, with 66 serotypes of EVs detected in them. The author also observed that NPEVs, just like rotaviruses, had a significant association with diarrhoea. EVs have also been reported as aetiological agents of acute encephalitis in Uttar Pradesh23,58 and Karnataka States59. The infrequent reports of their detection in clinical cases may reflect a lower prevalence or more probably the inadequacy of the existing surveillance systems in the country. There have been reports of outbreaks of HFMD from several parts of the country60. Coxsackievirus A16 (CV-A16) and CV-A6 have been major and CV-A10, EV-A71 and E-9, infrequent causes of these outbreaks in the southern and eastern parts of India61. Saxena et al62 reported the circulation of three genotypes of EV-A71 in India and also identified as a new genogroup (G) of the same. The authors observed that the genogroups D and G circulate widely in the country, while the sub-genogroup C1 was restricted to one focus in Western India. EV-A71 association has also been reported in cases of acute flaccid paralysis from Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka and Kerala25,26. The exact disease burden associated with EV-A71 infections in India needs detailed investigations

(ii) Reoviruses: Reoviridae includes viruses possessing linear double-stranded RNA genomes. Viruses of four genera, viz. Orbivirus, Rotavirus, Orthoreovirus and Coltivirus, affect animals and humans. Orbiviruses are known to infect humans, ruminants, horses, rodents, bats, marsupials, sloths and birds. These are transmitted by vectors which are included in Culicoides midges, mosquitoes, black flies, sand flies and ticks. Orbiviruses are widely distributed and contain 21 recognized species within multiple serotypes63.

(iii) Herpesviruses including Varicella-Zoster virus (VZV): Herpesviruses are the important aetiological agents of vesicular exanthems and central nervous system (CNS) infections. Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is known to cause vesicular ulcerative lesions in the oral cavity and can also infect the genitalia, liver, lungs, eyes and CNS. A recent report indicated that HSV-1 was a significant pathogen in paediatric cases of acute viral encephalitis64. HSV-2 causes painful genital ulcers and high morbidity and mortality in neonates acquiring it from infected mothers65. VZV, one of the herpes viruses, is the causative agent for varicella (chickenpox), an acute febrile illness (AFI) with diffuse maculopapular vesicular rash and herpes zoster (shingles). Estimates indicate that more than 30 per cent of people over the age of 15 yr in India are susceptible to VZV27. Varicella seroprevalence was 16 per cent in children aged 1-4 yr, 54 per cent in those between the ages of 5 and 14 yr and 72 per cent amongst those aged 15-25 yr66. Varicella occurs in endemic and epidemic forms in the country and carries secondary attack rates of >85 per cent in the exposed individuals67. Conditions of overcrowding and low immunization coverage make ideal grounds for outbreaks of varicella. In southern India, varicella shows a seasonal peak from January to April68. After the recovery from chickenpox infection, the virus remains dormant and reactivation of the virus leads to shingles. It is mostly seen in immunocompromised person and is not transmitted from human to human67.

Current scenario of emerging viral infections

Respiratory viral infections

Acute respiratory diseases claim over four million deaths every year and cause millions of hospitalization in developing countries every year69. Over 200 viral pathogens, belonging to the families Orthomyxoviridae, Paramyxoviridae, Picornaviridae, Coronaviridae, Adenoviridae and Herpesviridae, cause respiratory infections in humans. Influenza, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and adenoviruses remain important respiratory pathogens. Human metapneumovirus has also been recognized worldwide as a pathogen of significance70.

(i) Influenza: Influenza viruses, belonging to Orthomyxoviridae family, are the frequent causes of epidemics and pandemics affecting humans. Influenza pandemics have occurred earlier in 1918 (Swine influenza), 1957 (Asian flu), 1968 (Hong Kong flu), 1977 (Russian flu) and the recent pandemic of 2009 (pandemic influenza A H1N1)71. Influenza virus type A is highly variable, shows continuous antigenic variation and is a major cause of epidemics and pandemics. The surface antigenic glycoproteins undergo two major types of antigenic variation, viz. antigenic shift and antigenic drift. Antigenic shift is the result of major changes in one or both the surface antigens [haemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA)] and causes occasional pandemics. Three mechanisms might be operative in the antigenic shift, leading to emergence of pandemic influenza strains, viz. genetic re-assortment, direct transfer from avian/mammalian host to humans and virus recycling. Antigenic drift results due to minor changes in HA or NA and causes frequent epidemics72. Influenza viruses are continuously evolving and show ubiquitous distribution in the environment, animals and humans.

(ii) Severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV): SARS was first reported in the Guangdong province of China in February 2003 showing human-to-human transmission. The disease caused an estimated 8000 cases and more than 750 deaths in more than 12 countries73. The WHO issued a global alert about the disease on March 13, 200374. Although the cases mostly remained confined to China, a few cases were reported from North and South America, Europe and Asia. No case, however, has been reported fromIndia.

(iii) MERS-CoV: MERS-CoV is a zoonotic viral illness causing respiratory infection which was first reported in Saudi Arabia in 2012 and has since spread to 26 different countries. Over 2207 laboratory-confirmed cases and 787 deaths have occurred due to MERS-CoV infection globally, since 201275. The clinical spectrum of illness associated with MERS-CoV ranges from asymptomatic infections to acute respiratory distress syndrome, resulting in multi-organ failure and death. The case-fatality rates (CFRs) have remained high at 3-4 per 10 cases76. Limited information currently exists about the transmission dynamics of this virus, and definitive treatment and a prophylactic vaccination remain unavailable till date. Evidence for secondary, tertiary and quaternary cases of MERS ensuing from a single infected patient also exists, even in the absence of mutations conferring hyper-virulence77. No case of infection with this virus has been detected in India so far. Bats are thought to be the natural reservoirs of this virus, and many patients developed the illness after contact with camels. India is home to a great diversity of bat species and has substantial camel population. The country also reports heavy passenger traffic from the Middle East, as part of pilgrimage, employment, tourism and trade. These facts call for preparedness and surveillance against this virus in the country.

(iv) Avian influenza (AI): Humans are susceptible to infection with AI and swine influenza viruses, including the AI virus subtypes - A(H5N1), A(H7N9) and A(H9N2). Exposure to infected birds or contaminated environment is thought to underlie human infection with these viruses78. Human cases of AI might occur in future, in view of the ongoing circulation of AI viruses in birds. There have been sporadic reports of human infections with AI and other zoonotic influenza viruses, but sustained human-to-human infection and transmission have been lacking. Although the public health risk from the currently known influenza viruses at the human-animal interface remains the same, the sustained human-to-human transmission of this virus is low.

(v) RSV: RSV is an important pathogen causing acute lower respiratory tract infection (ALRTI) in young children. It can also affect older adults and immunocompromised individuals79. Estimates indicate an annual incidence of approximately 34 million episodes of ALRTI associated with RSV infection in children aged five years or less80. RSV infections also lead to about three million cases of hospitalization and about 66,000-199,000 deaths, with more than 99 per cent of the deaths reported from developing country80. In view of the public health significance, the WHO has started a pilot project for RSV surveillance in its six regions, utilizing the well-established platform of Global Influenza Surveillance and Response Network81. The exact burden and impact of RSV infections in the country need to be studied in depth.

Viral haemorrhagic fevers

(i) CCHF: CCHF was first recognized in 1944 from the West Crimean region, former Soviet Union as a huge outbreak, and the virus was subsequently isolated in 1956 from a human CCHF-positive case82. CCHF virus belongs to the genus Orthonairovirus of the family Nairoviridae. This virus had been detected from almost 30 countries in Africa, South-Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Western Asia. The CCHF viruses clustering is seen in 6-7 different groups (Group I - West African strains; Group II - Central African strains; Group III - South Africa and West Africa, Group IV - the Middle East and Asian strains; Group V - European strains; Group VI - Greek strains). Group IV involves Asia 1 and Asia 2 subgroups83. Phylogenetic analysis based on the S gene segment of CCHF virus had shown that the Indian CCHF virus strains formed a distinct cluster in the Asian-Middle East group IV84. Humans are normally infected by bites from ticks or close contacts with bodily fluids of acute viraemic CCHF-positive cases (showing potential for human to human transmission) and also from blood or tissue from viraemic livestock during handling or slaughtering. The high-risk groups are those who either get exposed to ticks (e.g. farmers, shepherds and veterinarians) and persons (mainly healthcare workers/family members) who come in close contact with the CCHF patients85.

-

Since its first detection in the country in 201186, many nosocomial and sporadic outbreaks of CCHF have been investigated in Gujarat and the adjoining Rajasthan State28,87. A nation-wide survey by the ICMR-National Institute of Virology (ICMR-NIV), Pune, revealed wide seropositivity amongst sheep, goat and cattle population across the country88. Since 2011 till December 2018, almost 81 cases have been diagnosed positive for CCHF (NIV, unpublished data).

The clinical manifestations typically develop after incubation period of 1-3 (maximum 9) days after exposure to tick bite; while in infections acquired through direct contact with viraemic livestock or CCHF-positive patients, it may extend to 5-6 (maximum 13) days. The clinical features include abrupt onset of high-grade fever, severe headache, malaise, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and sore throat. The disease typically progresses through the stages of incubation period, pre-haemorrhagic, haemorrhagic period and then convalescence89. Molecular assays such as conventional reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and qualitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) have been used to detect CCHF RNA and for laboratory diagnosis. Several serological tests including enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) have also been developed to detect CCHF-specific IgM and IgG antibodies. The isolation and propagation of CCHF virus require a high-containment [biosafety level (BSL)-4] laboratory. No specific treatment is available for CCHF disease and treatment includes supportive medications and maintenance of fluid-electrolyte balance, timely monitoring and replacement of platelets in case of severe thrombocytopenia along with administration of fresh-frozen plasma and erythrocyte preparations to maintain the blood volume in case of circulatory failure. The antiviral drug ribavirin has shown promise in some studies89; however, its use remains controversial. The WHO has recently declared CCHF as the highest priority disease globally, needing urgent research and development90. Serious alertness and cohesive work under the 'One Health Programme' is required to cope up with the threat of this dreadful zoonotic disease.

-

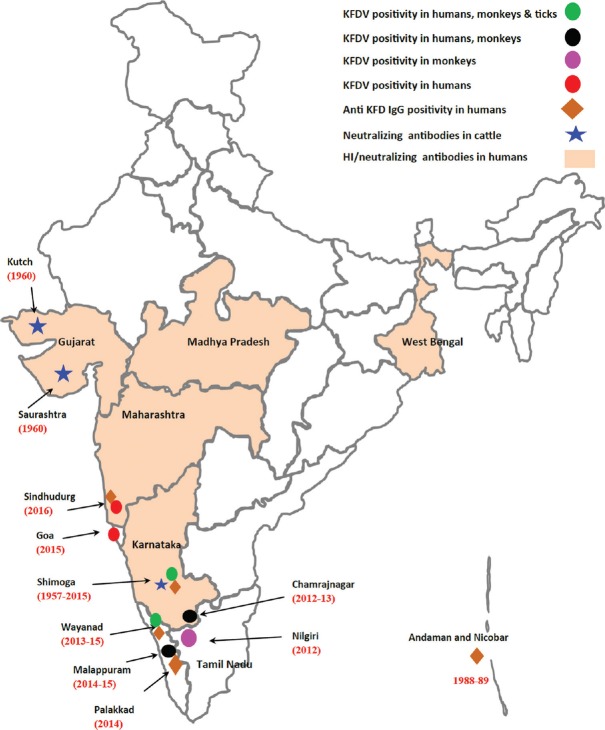

(ii) KFDV: The KFDV belongs to genus Flavivirus and family Flaviviridae. The virus was identified for the first time in 1957, during investigations of a febrile illness affecting monkeys (including the species Semnopithecus entellus and Macaca radiata) and also humans14. KFDV is usually maintained in nature by enzootic cycles which occur between small mammals and ticks. Monkeys acquire the infection through bites of infected Haemaphysalis spinigera ticks, develop disease and pass on the infection to ticks that feed on them subsequently. In monkeys, the illness manifests as a severe febrile illness. Ticks dropping off from the bodies of monkeys that die of the illness create hotspots of infection which further spread the virus. Since 1957, the disease has occurred in sporadic and epidemic form in many parts of Karnataka State in India. However, since 2012, KFD infections (involving monkeys and humans) have also been reported from States of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Goa and Maharashtra29. With widespread distribution across the Western Ghats, KFDV has emerged as an important disease of public health importance in the past few years91,92 (Fig. 3). After an incubation period of 3-8 days following the tick bite, the illness manifests with high-grade fever with or without chills, frontal headache and body ache, lasting for 5-12 days. The CFR is generally around 3-5 per cent and the convalescence is often prolonged. In some infected individuals, the illness is biphasic, starting after a febrile period of 1-2 wk. The fever mostly lasts from 2 to 12 days and is mainly started with headache and CNS manifestations are usually apparent. Neck stiffness, psychological disturbances, coarse tremors, giddiness and abnormalities in reflexes are often noted.

Laboratory diagnosis generally relies on the detection of KFDV RNA in serum/blood samples by conventional RT-PCR or qRT-PCR. ELISA tests are also used to diagnose KFDV-specific IgM and IgG antibodies. Isolation and propagation of KFDV require a BSL-4 laboratory. A formalin-inactivated, chick embryo fibroblast-derived KFD vaccine is currently employed for prophylaxis in the affected areas. The vaccine was found to be immunogenic, safe and potent. However, no specific treatment is available for KFD till date and management is mostly supportive93.

-

(iii) Rift valley fever (RVF) virus: RVF belongs to genus Phlebovirus. First time, this virus was identified in 1931 during an investigation of an epidemic amongst the sheep farm in the Rift Valley of Kenya94. Since then, many outbreaks have been reported in Sub-Saharan Africa. RVF is primarily a disease for animals with zoonotic potential to cause infection in humans. It is transmitted to humans either through contact of blood or fluids of infected animals as well as bite from infected mosquitoes (Aedes or Culex species). Till date, human is considered as dead end and no human-to-human transmission is reported in RVF. This disease is known in two forms: mild and severe. Incubation period is 2-6 days. Milder form generally presents with flu-like symptoms, fever, myalgia, arthralgia, vomiting, malaise, etc95.

Majority of cases are relatively mild; still a small percentage of patients develop severe forms of disease including: ocular (eye) disease (in 0.5-2%) with blurred vision, lesions in eyes involving macula leading to loss of vision. These symptoms start after 1-3 wk of initial mild symptoms; meningoencephalitis form (in less than 1%) that usually occurs after 1-4 wk of onset of initial RFV symptoms presenting with severe headache, memory loss, disorientation, lethargy, convulsions, hallucinations leading to coma and neurological complications; and haemorrhagic fever form (in <1%) in whom haemorrhagic symptoms generally appear 2-4 days after disease onset. Bleeding manifestation includes haematemesis, melaena, purpuric rash or ecchymosis, bleeding in gums, epistaxis, menorrhagia and bleeding from venepuncture site. CFR in bleeding cases is almost 50 per cent95.

Laboratory diagnosis is mainly through qRT-PCR and IgM ELISA assay. Till date, there is no specific vaccine or drug available for RVF treatment.

-

(iv) Yellow fever (YF) virus: YF is a viral haemorrhagic fever disease transmitted by infected Aedes mosquitoes and the virus belongs to family Filoviridae. This disease is endemic in tropical areas of Africa and Central and South America. YF presents with acute-onset jaundice with constitutional symptoms such as fever, headache, myalgia, nausea, vomiting and fatigue. The cases with severe symptoms may land up in liver and multi-organ failure and CFR may be up to 50 per cent in such cases96.

Laboratory diagnosis is mainly through qRT-PCR and IgM ELISA assay. Plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) may be needed due to cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses. An extremely effective vaccine is available against YF. A single dose of YF vaccine is sufficient to provide life-long immunity within 10 days after vaccination (80-100% effective) while 99 per cent immunity within 30 days. A booster dose of the vaccine is not needed. There is currently no specific anti-viral drug available for the treatment of YF, and hence, vaccination against YF is mainstay of prevention96.

Fig. 3.

Kyasanur forest disease positivity in human, ticks and monkeys recorded in different States of India during recent past. Source: Ref. 92.

Gastroenteritis viruses

(i) Rotavirus: Rotavirus is double-stranded RNA virus belonging to the family Reoviridae. It is one of the major causes of severe and dehydrating diarrhoea amongst children aged less than five years. In India, rotavirus is responsible for almost 22 per cent deaths, 30 per cent hospitalizations and 8.3 per cent outpatient visits each year30. Two rotavirus vaccines, namely Rotarix and RotaTeq, have been licensed for prophylaxis of rotavirus diarrhoea. The WHO has recommended both these vaccines to be included in childhood immunization programmes97. A study conducted in Pune highlighted the burden of rotavirus disease and changing profile of circulating rotavirus strains, highlighting the emergence of G9P(4) re-assortant strains98. Surveillance of rotaviral infections will help in early identification of the rare and emerging strains of rotaviruses. Thus, monitoring of rotavirus disease and strains is essential to assess the impact of rotavirus vaccines and circulating rotavirus strains in the country.

(ii) Sapovirus: Sapovirus is responsible for acute gastroenteritis (AGE) in humans as well as animals. These are of public health importance due to sporadic outbreaks reported in people of all age groups worldwide. In 1976, in the United Kingdom (UK), sapovirus particles were discovered in human stool samples for the first time99 and eventually identified as a new gastroenteritis pathogen due to its worldwide distribution100. Sapovirus belongs to the genus Sapovirus of family Caliciviridae. There are 14 genogroups of sapoviruses. The four genogroups of human sapovirus infection are GI, GII, GIV and GV. GIV1 strains are detected and reported from Canada, Japan, United States, Europe in 200731. The first detection of sapovirus in India was in 2000 from Vellore101. During the investigation of a food-borne outbreak in Delhi, Norovirus (NoV) belonging to GII genogroup was identified102. During a paediatric gastroenteritis outbreak investigation in Vellore in south India in 2007, sapovirus infections accounted for 16.7 per cent of cases103. In India, sapovirus has also been detected in asymptomatic children. It seems probable that sapovirus infections might contribute significantly to the burden of diarrhoeal diseases in India. Limited information exists on the sequence diversity of sapoviruses in India, and molecular epidemiological studies need to be performed to understand the dynamics of sapovirus infections in the country.

(iii) Novovirus: NoV is RNA virus of the family Caliciviridae. Human NoV, erst Norwalk virus, was first detected in the stool specimen of a gastroenteritis outbreak in Norwalk. It was the first viral agent reported as a cause of AGE104. These are the leading cause for AGE outbreaks reported amongst all the age groups worldwide after rotavirus32,105. There are five genotypes of NoV (GI-GV), of which GI, GII and GIV are responsible for human AGE cases. NoV was reported amongst AGE cases in western India106. NoV positivity was found to be 6.3-12.6 per cent with a prominence of GII genotype (96.6%)107, suggesting it to be the second most common cause of non-bacterial gastroenteritis after rotavirus in western India. Of the 59 human Caliciviridae strains from India, 61 per cent were NoV with predominance of GII genotype (15%), which were detected using two-step multiplex RT-PCR108. In India, NoV infections are common cause of childhood AGE cases. The replacement of strains had made a cautionary and pointed out the need for strain-specific vaccines.

Acute febrile illness (AFI) and acute-undifferentiated fever (AUF)

Increasing number of cases of febrile illnesses, in which a definitive aetiology is not detectable, leading to their classification as fever of unknown origin (FUO), has been a concern in the tropical countries. Locally endemic infections such as malaria, dengue, leptospirosis, rickettsial infections, Japanese encephalitis33 and influenza could probably be responsible for AUF cases. Unavailability of diagnostic facilities, challenges in collection, transport and testing of the right type of specimen(s) at the right time often impact accurate laboratory diagnosis of these conditions. Bacteriological tests often reveal infections with Salmonella sp., Leptospira sp., Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus also as the underlying cause of FUO. Despite a battery of tests for a variety of pathogens, an aetiological agent is often not detected in as much as one-third to one-fourth of patients with FUO109.

Acute encephalitis syndrome (AES) and acute encephalopathy

-

(i) Nipah virus (NiV) disease: For the first time, NiV was identified during an outbreak of acute febrile encephalitis cases amongst pig handlers that occurred in Kampung Sungai Nipah, Malaysia, in 1998110. NiV, along with Hendra virus, belongs to the Henipavirus and is a pathogenic paramyxovirus which causes acute-onset encephalitis, leading to deaths in humans. The reservoir for NiV is known to be Pteropus bats (flying foxes) and transmission to humans usually occurs through contact of positive NiV cases through their infectious secretions or an intermediate animal host such as pigs. Human-to-human spread of the virus has also been described110. Outbreaks of NiV in pigs have been reported from Malaysia and Singapore. Subsequently, human disease has been reported from Malaysia, Singapore, India and Bangladesh110. Evidence of the virus without clinical disease has also been found in fruit bats in Cambodia, Thailand and Madagascar. The outbreaks of human cases of NiV have been reported in Siliguri (2001) and Nadia (2007) districts of West Bengal111. A focal outbreak that led to 18 laboratory-confirmed cases and amongst them 16 deaths in Kozhikode and Malappuram districts of Kerala State in south India in May 2018 has been the latest report of this deadly disease112.

NiV disease in human has average incubation period of 4-14 days with maximum incubation period of 21 days. The virus causes multi-organ vasculitis and the pathology is seen mostly in the CNS and the respiratory system. The virus causes acute febrile encephalitis with symptoms including fever, headache, drowsiness, dizziness and coma. Thrombocytopenia, leucopenia and elevated aspartate aminotransferase and alanine transaminase levels have also been reported from NiV-infected cases. NiV infection in pigs is known as porcine respiratory and encephalitis syndrome and barking pig syndrome. Infections by NiV in humans and animals are confirmed by virus isolation, RNA as well as anti-Nipah IgM and IgG antibodies detection. BSL-4 facilities are mandatory for isolation as well as virus propagation. There are no vaccines available for NiV for human use. Studies in small-animal models of NiV infection suggest that monoclonal antibodies therapy may be promising113.

The circulation of NiV has been confirmed in Pteropus giganteus bat populations of West Bengal and Assam States of India34 (Fig. 4). Large colonies/roosts of this bat species were observed in proximity of human settlements. This indicated that the north-eastern region of India could be one of the hot spots for spillover of NiV infection from bat to human population.

(ii) Thottapalayam virus (TPMV): In India, TPMV was isolated for the first time from the Asian house shrew (Suncus murinus) from Vellore, in 1964114. TPMV belongs to the family Hantaviridae and the genus Orthohantavirus. Serological and electron microscopic studies confirmed its resemblance to Hantaviruses (HTNV). The house shrew naturally harbours this virus. It is known to cause transient viraemia with shedding of virus from oropharyngeal secretions of the house shrew. Delayed excretion and presence of virus in urine, faeces and persistence in tissues, particularly lung, have also been recorded.

-

(iii) Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV): LCMV is a rodent-borne disease that causes a wide range of human infections from meningoencephalitis to congenital birth defects. It is also known to cause severe disseminated illness reported from organ transplant immunocompromised patients35. Isolation of this virus was done from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of a menigoencephalitis case in 1933 for the first time115. In 1955, first congenital LCMV was reported in England following which multiple cases were reported throughout Europe and the United States116. In pregnancy, LCMV may cause foetal death or induce/spontaneous abortion and the surviving foetuses can be visually impaired or with brain dysfunction117. Rodents, especially house mouse, are the main reservoirs of LCMV and exposure to their secretions, and excreta leads to transmission to humans. Congenital LCMV does not occur unless pregnant women contracts with primary LCMV infection during pregnancy35.

In India, the incidence of LCMV was observed to be 0.76 per cent in mice. The presence of LCMV in rat and mice of southern and north India was analyzed and found to be 2.85 per cent117,118. Extensive surveys need to be done in the areas of the country, showing abundance of rodents to understand circulation of LCMV and to assess its epidemic potential.

(iv) Human parvovirus-4 (PARV4): It is a single-stranded DNA virus, first identified in 2005 from a hepatitis-B-positive patient who was intravenous drug user (IDU)119. PARV4 belongs to family Parvoviridae. The other viruses of significance in this family are parvovirus B19, human bocaviruses 1-4 and adeno-associated viruses 1-536. There are three genotypes of PARV4. Among these, genotypes 1 and 2 are predominantly found in Europe, North America as well as Asia, while genotype 3 is found mainly in Africa. PARV4 infection and its widespread presence in diverse tissue samples have been recently detected120. Transmission of PARV4 to humans occurs amongst IDU and is strongly linked to acquisition of both HCV and HIV infection as reported in Europe and North America36. The presence of PARV4 in two per cent plasma samples from voluntary blood donors has been reported from North America121. These viruses were found resistant to traditional methods for viral inactivation employed mainly for plasma-derived products. A high prevalence of PARV4 infection (35%) among those with HIV infection (with or without HCV co-infection) has been reported from Iran122. High PARV4 levels were observed in CSF in children suspected to have encephalitis from southern India suggesting an acute infection123. The incidence of PARV4 in humans in India is limited, thus, the clinical significance of PARV4 remains unclear.

-

(v) Human cytomegalovirus (CMV): CMV, also known as human herpesvirus-5, is a highly host-specific virus belonging to Herpesviridae family37. In 1956, CMV was isolated by Smith124 from submaxillary gland of a dead infant for the first time. The virus is of public health importance as it is known to responsible for high morbidity and mortality in new-borns as well as immunocompromised patients. It is probably one of the most common infections amongst healthy individual characterized by a self-limiting infection. Besides contact with seropositive mothers (passage through genital tract, breast milk, etc.), blood transfusion is also known as one of the most important mode of perinatal/post-natal spread of CMV to neonates. Distribution of CMV is seen globally and predominantly in developing countries125.

Foetus can be infected after a primary or a recurrent infection in pregnant women. Infections in utero are associated with intrauterine death or congenital foetal abnormalities and intrauterine growth retardation along with developmental delays, blindness and deafness as sequelae126,127. Infections are usually subclinical and can be confirmed only by laboratory testing. CMV is a common congenital infection worldwide with estimated incidence of 0.2-2.2 per cent and seroprevalence of 45-100 per cent128. Seroprevalence in India is about 80-90 per cent129. In a recent seroprevalence study in western India, 83 per cent seropositivity for CMV IgG and 9.46 per cent seropositivity for CMV IgM have been observed in antenatal women129. In India, due to scarcity of data regarding birth defects, it is difficult to extrapolate the true incidence of recurrent CMV.

(vi) CHPV: CHPV is a single-stranded, negative sense, RNA arbovirus of the genus Vesiculovirus and family Rhabdoviridae. CHPV was first discovered by Bhatt and Rodrigues130 in 1966 during investigations of febrile illness in Chandipura region of Maharashtra. Epidemics of CHPV-associated AES were reported in young children from Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat and Nagpur38. Apart from India, CHPV is prevalent in West Africa since 1975, which had been isolated from hedgehog and phlebotomine sand flies131. Phlebotomine sand flies are the main vectors for CHPV transmission. CHPV is also known to infect mosquitoes, mainly Ae. aegypti; it survives in the salivary gland of the mosquito for 4-5 days and is then transmitted to other vertebrates. Adults are unaffected by CHPV, while CFRs in infected children can range from 56 to 75 per cent. Despite the progress made in understanding the virus and development of diagnostics, antivirals and control strategies, CHPV is a known public health problem in certain parts of Maharashtra and in Andhra Pradesh132. Although the case fatality rates could be reduced, a substantial section of population in these regions remains at risk. The factors responsible for the amplification of this virus in natural reservoirs need to be investigated in detail.

Fig. 4.

Geographic location of bat collection (indicated by arrows) and Tioman virus positivity in Pteropus giganteus bat (indicated by black dot), North-East India. Source: Adapted from Ref. 34.

Other emerging and re-emerging viruses

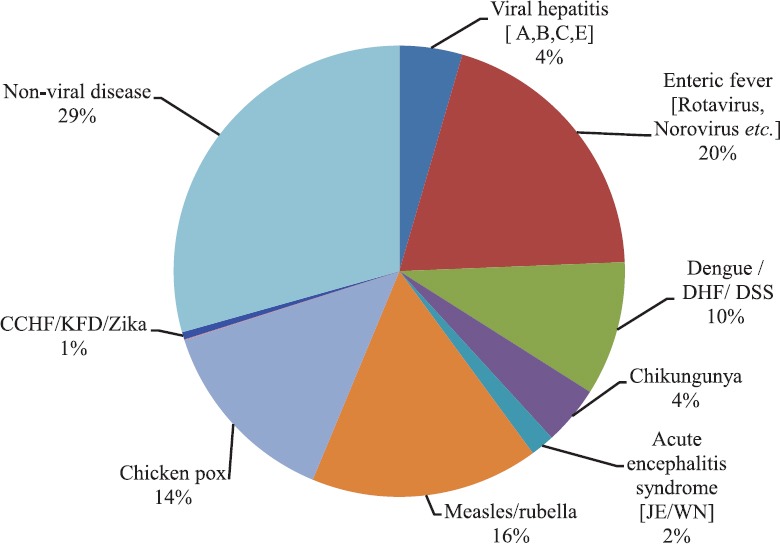

(i) Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV): SFTSV is a tick-borne virus and belongs to the genus Phlebovirus and family Bunyaviridae (Fig. 5) reported from China, Japan and South Korea133,134. The clinical spectrum of illness associated with this virus includes fever, thrombocytopenia, leucocytopenia, gastrointestinal and muscular symptoms, neurological abnormalities, coagulopathy and haemophagocytic syndrome. SFTSV has been detected in Haemaphysalis ticks134; however, this virus has also been detected in bats135; hence, it is difficult to comment upon the likely vectors for its transmission to humans or other animals. The seroprevalence of SFTV is reported from domesticated animals, including sheep, goats, cattle, pigs, dogs and chickens136.

(ii) Malsoor virus: Malsoor virus is a novel phlebovirus, belonging to family Phenuiviridae. It was isolated from bats in India and found phylogenetically related to SFTSV135. The potential of Malsoor virus to cause disease in humans remains unknown. In India, bats often live near human habitats and the potential spillover of viral pathogens from them to humans is a matter of concern.

(iii) Chobar Gorge virus (CGV): The tick-borne Orbivirus species which includes Chenuda virus, CGV, Wad Medani virus and Great Island virus39. CGV was isolated from Ornithodoros spp136. CGV is divided into two serotypes: serotype-1 from ticks collected from a limestone cave in Nepal while Fomede virus (FV) was isolated from bat species in caves in Guinea in 1978. Serological evidence was found in horses, sheep, cattle, buffalo and humans137. The virus has a genomic structure similar to the other tick-borne orbiviruses and consists of seven structural and three non-structural proteins. However, no human disease has been attributed to it so far39.

(iv) Equine encephalosis virus (EEV): EEV is an arthropod-borne Orbivirus (Family Reoviridae) and causes febrile non-contagious disease in equids138. In 1967, EEV was isolated from horses in South Africa for the first time. The infection presents as an acute illness involving lack of appetite and oedema40. The disease results in 60-70 per cent morbidity in equids, but deaths are rare139. Two species of the midges belonging to Culicoides species are known to be the vectors for EEV138. Recently, complete genome of EEV has been obtained from a dead horse from India with next-generation sequencing methods, thus confirming its presence in the country41.

(v) Buffalopox virus (BPXV) from human and buffaloes in India: Poxviruses are the largest and complex viruses belonging to genus Orthopoxvirus (OPXV) under the subfamily Chordopoxvirinae (infecting vertebrates) of poxviruses140. The OPXVs include variola virus (VARV), vaccinia virus (VACV), monkeypox virus, cowpox virus (CPXV), camelpox virus (CMLV), horse pox virus, rabbitpox virus, buffalopox virus, Cantagalo virus and Aracatuba viruses. OPXV genomes typically measure about 200 Kb and contain conserved coding regions in centre essential for viral replication as well as for virus assembly with variable terminal ends which determine host range and pathogenicity141. All OPXVs are immunologically related to each other, causing cross-reactivity and cross-protection142. The practice of vaccination with VACV began in the 20th century, and in 1979, human smallpox (VARV) was successfully eradicated143.

Fig. 5.

Place of first isolation of Bunyaviruses in India. Source: Adapted from Ref. 46.

BPXV is a double-stranded, enveloped DNA virus in the genus OPXV and family Poxviridae42. BPX is a highly contagious and one of the known and important zoonotic viral disease144 affecting humans and livestock species such as buffaloes and cow. This disease causes considerable financial loss to the dairy industry in terms of reduction in milk production and draught capacity145. In buffaloes and cows, this disease affects udder, teats, inguinal region, ears and eyes, and in the generalized form, it affects the hindquarters146. In humans, the disease is characterized by erythematous pocks on arms, face and neck, along with fever, axillary lymphadenopathy and malaise147. Till date, BPX has been reported frequently from different States of India as well as in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Indonesia and Egypt147. The first report of a zoonotic human case of BPX was reported in 1934148. Nosocomial infection of BPXV in human beings has also been reported in Pakistan149.

Despite the successful smallpox eradication programme, a possibility exists that VARV and VACV-related viruses may re-emerge in human and animal population, posing a public health threat. Hence, a deeper understanding of the evolutionary biology and host specificity of OPXVs becomes important. Measures for prevention of BPX warrant high priority, considering its increasing incidence, the potential economic loss to the dairy sector as well as the zoonotic impact on humans.

Conclusion

India, being a country of extreme geo-climatic diversity, faces a constant threat of emerging and re-emerging viral infections of public health importance (Tables I and II). There is a need for strengthening disease surveillance in the country focusing on the epidemiology and disease burden. There is also a pressing need to gain detailed insights into disease biomics, including vector biology and environmental factors influencing the diseases. It is also important to strengthen the emergency preparedness for these diseases and response by focusing on 'one health' approach.

Table II.

Known future threat of emerging viral infections in India

| Virus | Probable/mode of transmission | Outbreak potential | Biosafety-risk group |

|---|---|---|---|

| MERS-CoV | Air-borne | Yes | 3 |

| Ebola virus | Direct contact | Yes | 4 |

| Avian influenza (H7N9) | Direct contact | Yes | 3 |

| Air-borne | |||

| Rare, limited person-to-person spread | |||

| Avian influenza (H9N2) human infection China | Direct contact | Yes | 3 |

| Air-borne | |||

| Rare limited person-to-person spread | |||

| Yellow fever virus | Arthropod-borne | Yes | 2 |

| Usutu virus-like-JE (mosquito-borne) | Arthropod-borne | Yes | 2 |

| Tilapia novel orthomyxo-like virus, causes hepatitis | Indirect transmission by fomites | Unknown | Unknown |

| Cyclovirus | Faeco-oral | Yes* | Unknown |

| Banna Reo virus encephalitis - (China) like-JE | Arthropod-borne | Yes | Unknown |

| Canine parvovirus causes dog gastroenteritis | Direct or indirect contact | Yes* | Unknown |

Acknowledgment:

Authors acknowledge the encouragement and support given by Dr Balram Bhargava, Secretary, Department of Health Research and Director General, Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi. We also acknowledge Dr Prachi Pardeshi from BSL-4 facility, ICMR-National Institute of Virology, Pune, for help she extended for this review.

Footnotes

Financial support & sponsorship: None.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Dikid T, Jain SK, Sharma A, Kumar A, Narain JP. Emerging & re-emerging infections in India: An overview. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138:19–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mani RS, Ravi V, Desai A, Madhusudana SN. Emerging viral infections in India. Proc Natl Acad Sci India Sect B Biol Sci. 2012;82:5–21. doi: 10.1007/s40011-011-0001-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarma N. Emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases in South East Asia. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:451–5. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_389_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization, South-East Asia Region, Western Pacific Region. Asia Pacific strategy for emerging diseases: 2010. New Delhi, Manila: WHO, South-East Asia Region, Western Pacific Region; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tran TH, Nguyen TL, Nguyen TD, Luong TS, Pham PM, Nguyen V, et al. Avian Influenza A (H5N1) in 10 patients in Vietnam. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1179–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gopalakrishnan R, Sureshkumar D, Thirunarayan MA, Ramasubramanian V. Melioidosis: An emerging infection in India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2013;61:612–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arankalle VA, Shrivastava S, Cherian S, Gunjikar RS, Walimbe AM, Jadhav SM. Genetic divergence of Chikungunya viruses in India (1963-2006) with special reference to the 2005-2006 explosive epidemic. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(Pt 7):1967–76. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82714-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jupp P, McIntosh B. Chikungunya virus disease. In: Monath TP, editor. The arboviruses: epidemiology and ecology. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, Inc; 1988. pp. 137–57. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halstead SB. Dengue. Lancet. 2007;370:1644–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61687-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paixão ES, Teixeira MG, Rodrigues LC. Zika, chikungunya and dengue: The causes and threats of new and re-emerging arboviral diseases. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3:e000530. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhardwaj S, Gokhale MD, Mourya DT. Zika virus: Current concerns in India. Indian J Med Res. 2017;146:572–5. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1160_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatt PN, Rodrigues FM. Chandipura: A new arbovirus isolated in India from patients with febrile illness. Indian J Med Res. 1967;55:1295–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casals J. Antigenic similarity between the virus causing Crimean hemorrhagic fever and Congo virus. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1969;131:233–6. doi: 10.3181/00379727-131-33847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nichter M. Kyasanur forest disease: An ethnography of a disease of development. Med Anthropol. 1987;1:406–23. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India. [accessed on June 5, 2018]. Available from: http://idsp.nic.in/index4.php?lang=1&level=0&linkid=406&lid=3689 .

- 16.Cecilia D. Current status of dengue and chikungunya in India. WHO South East Asia J Public Health. 2014;3:22–6. doi: 10.4103/2224-3151.206879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Communicable disease alert and response for mass gatherings. Key considerations. Geneva: WHO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.David S, Roy N. Public health perspectives from the biggest human mass gathering on earth: Kumbh Mela, India. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;47:42–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meena V. Temples of South India. Kanyakumari: Hari Kumari Arts; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hays JN. Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History. Santa Barbara, CA and Oxford: ABC-CLIO; 2005. p. 527. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koul PA, Mir H, Saha S, Chadha MS, Potdar V, Widdowson MA, et al. Respiratory viruses in returning Hajj & Umrah pilgrims with acute respiratory illness Kashmir, north India in 2014-2015. Indian J Med Res. 2018;148:329–33. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_890_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harit AK, Ichhpujani RL, Gupta S, Gill KS, Lal S, Ganguly NK, et al. Nipah/Hendra virus outbreak in Siliguri, West Bengal, India in 2001. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:553–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar A, Shukla D, Kumar R, Idris MZ, Misra UK, Dhole TN. Molecular epidemiological study of enteroviruses associated with encephalitis in children from India. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3509–12. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01483-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rao CD. Non-polio enteroviruses, the neglected and emerging human pathogens: Are we waiting for the sizzling enterovirus volcano to erupt? Proc Indian Natn Sci Acad. 2015;81:447–62. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deshpande JM, Nadkarni SS, Francis PP. Enterovirus 71 isolated from a case of acute flaccid paralysis in India represents a new genotype. Curr Sci. 2003;84:1350–3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rao CD, Yergolkar P, Shankarappa KS. Antigenic diversity of enteroviruses associated with nonpolio acute flaccid paralysis, India, 2007-2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:1833–40. doi: 10.3201/eid1811.111457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arunkumar G, Vandana KE, Sathiakumar N. Prevalence of measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella susceptibility among health science students in a university in India. Am J Ind Med. 2013;56:58–64. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yadav PD, Patil DY, Shete AM, Kokate P, Goyal P, Jadhav S, et al. Nosocomial infection of CCHF among health care workers in Rajasthan, India. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:624. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1971-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Awate P, Yadav P, Patil D, Aich A, Kumar V, Kore P, et al. Outbreak of Kyasanur forest disease (Monkey fever) in Sindhudurg, Maharashtra state, India, 2016. J Infect. 2016;72:759–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tate JE, Chitambar S, Esposito DH, Sarkar R, Gladstone B, Ramani S, et al. Disease and economic burden of rotavirus diarrhoea in India. Vaccine. 2009;27(Suppl 5):F18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.08.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Svraka S, Vennema H, van der Veer B, Hedlund KO, Thorhagen M, Siebenga J, et al. Epidemiology and genotype analysis of emerging Sapovirus-associated infections across Europe. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2191–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02427-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng WX, Ye XH, Yang XM, Li YN, Jin M, Jin Y, et al. Epidemiological study of human calicivirus infection in children with gastroenteritis in Lanzhou from 2001 to 2007. Arch Virol. 2010;155:553–5. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0592-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kulkarni R, Sapkal GN, Kaushal H, Mourya DT. Japanese encephalitis: A brief review on Indian perspectives. Open Virol J. 2018;12:121–30. doi: 10.2174/1874357901812010121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yadav P, Sudeep A, Gokhale M, Pawar S, Shete A, Patil D, et al. Circulation of Nipah virus in Pteropus giganteus bats in northeast region of India, 2015. Indian J Med Res. 2018;147:318–20. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1488_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonthius DJ. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: A prenatal and postnatal threat. Adv Pediatr. 2009;56:75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.yapd.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matthews PC, Malik A, Simmons R, Sharp C, Simmonds P, Klenerman P. PARV4: An emerging tetraparvovirus. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004036. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chakravarti A, Kashyap B, Matlani M. Cytomegalovirus infection: An Indian perspective. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2009;27:3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gurav YK, Tandale BV, Jadi RS, Gunjikar RS, Tikute SS, Jamgaonkar AV, et al. Chandipura virus encephalitis outbreak among children in Nagpur division, Maharashtra, 2007. Indian J Med Res. 2010;132:395–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Belaganahalli MN, Maan S, Maan NS, Brownlie J, Tesh R, Attoui H, et al. Genetic characterization of the tick-borne orbiviruses. Viruses. 2015;7:2185–209. doi: 10.3390/v7052185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Howell PG, Guthrie AJ, Coetzer JAW. Infectious diseases of livestock. Oxford University Press: Cape Town; 2004. pp. 1247–51. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yadav PD, Albariño CG, Nyayanit DA, Guerrero L, Jenks MH, Sarkale P, et al. Equine encephalosis virus in India, 2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:898–901. doi: 10.3201/eid2405.171844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh RK, Hosamani M, Balamurugan V, Satheesh CC, Shingal KR, Tatwarti SB, et al. An outbreak of Buffalopox in buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) dairy herds in Aurangabad, India. Rev Sci Tech. 2006;25:981–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sudeep AB, Jadi RS, Mishra AC. Ganjam virus. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130:514–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsuno K, Weisend C, Travassos da Rosa APA, Anzick SL, Dahlstrom E, Porcella SF, et al. Characterization of the Bhanja serogroup viruses (Bunyaviridae): A novel species of the genus Phlebovirus and its relationship with other emerging tick-borne phleboviruses. J Virol. 2013;87:3719–28. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02845-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yadav PD, Nyayanit DA, Shete AM, Jain S, Majumdar TP, Chaubal GY, et al. Complete genome sequencing of Kaisodi virus isolated from ticks in India belonging to Phlebovirus genus, family phenuiviridae. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2019;10:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yadav PD, Chaubal GY, Shete AM, Mourya DT. A mini-review of bunyaviruses recorded in India. Indian J Med Res. 2017;145:601–10. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1871_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rogers DJ, Wilson AJ, Hay SI, Graham AJ. The global distribution of yellow fever and dengue. Adv Parasitol. 2006;62:181–220. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(05)62006-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sudeep AB, Bondre VP, Mavale MS, Ghodke YS, George RP, Aher RV, et al. Preliminary findings on Bagaza virus (Flavivirus: Flaviviridae) growth kinetics, transmission potential & transovarial transmission in three species of mosquitoes. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138:257–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karron RA, Black RE. Determining the burden of respiratory syncytial virus disease: The known and the unknown. Rancet. 2017;390:917–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31476-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Presti RM, Zhao G, Beatty WL, Mihindukulasuriya KA, da Rosa APAT, Popov VL, et al. Quaranfil, Johnston Atoll, and Lake Chad viruses are novel members of the family Orthomyxoviridae. J Virol. 2009;83:11599–606. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00677-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rao S, Messacar K, Torok MR, Rick AM, Holzberg J, Montano A, et al. Enterovirus D68 in critically ill children: A comparison with pandemic H1N1 influenza. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17:1023–31. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Briese T, Renwick N, Venter M, Jarman RG, Ghosh D, Köndgen S, et al. Global distribution of novel rhinovirus genotype. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:944–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1406.080271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Munivenkatappa A, Yadav PD, Nyayanit DA, Majumdar TD, Sangal L, Jain S, et al. Molecular diversity of coxsackievirus A10 circulating in the Southern and Northern region of India [2009-17] Infect Genet Evol. 2018;66:101–10. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Purdy MA. Hepatitis B virus S gene escape mutants. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2007;1:62–70. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.33445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yadav PD, Shete AM, Nyayanit DA, Albarino CG, Jain S, Guerrero LW, et al. Identification and characterization of novel mosquito-borne (Kammavanpettai virus) and tick-borne (Wad Medani) reoviruses isolated in India. J Gen Virol. 2018;99:991–1000. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.001102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Riyesh T, Karuppusamy S, Bera BC, Barua S, Virmani N, Yadav S, et al. Laboratory-acquired Buffalopox virus infection, India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:324–6. doi: 10.3201/eid2002.130358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. ICTV Virus Taxonomy: The online (10th) report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Genus Enterovirus. [accessed on June 23, 2018]. Available from: https://talk.ictvonline.org/ictv-reports/ictv_online_report/positive-sense-rna-viruses/picornavirales/w/picornaviridae/681/genus-enterovirus .

- 58.Sapkal GN, Bondre VP, Fulmali PV, Patil P, Gopalkrishna V, Dadhania V, et al. Enteroviruses in patients with acute encephalitis, Uttar Pradesh, India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:295–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1502.080865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lewthwaite P, Perera D, Ooi MH, Last A, Kumar R, Desai A, et al. Enterovirus 75 encephalitis in children, Southern India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1780–2. doi: 10.3201/eid1611.100672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sarma N. Hand, foot, and mouth disease: Current scenario and Indian perspective. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:165–75. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.107631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gopalkrishna V, Patil PR, Patil GP, Chitambar SD. Circulation of multiple enterovirus serotypes causing hand, foot and mouth disease in India. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:420–5. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.036400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saxena VK, Sane S, Nadkarni SS, Sharma DK, Deshpande JM. Genetic diversity of enterovirus A71, India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:123–6. doi: 10.3201/eid2101.140743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Attoui H, Mohd Jaafar F. Zoonotic and emerging orbivirus infections. Rev Sci Tech. 2015;34:353–61. doi: 10.20506/rst.34.2.2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kumar R, Kumar P, Singh MK, Agarwal D, Jamir B, Khare S, et al. Epidemiological profile of acute viral encephalitis. Indian J Pediatr. 2018;85:358–63. doi: 10.1007/s12098-017-2481-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Looker KJ, Magaret AS, Turner KM, Vickerman P, Gottlieb SL, Newman LM. Global estimates of prevalent and incident herpes simplex virus type 2 infections in 2012. PLoS One. 2015;10:e114989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee BW. Review of varicella zoster seroepidemiology in India and Southeast Asia. Trop Med Int Health. 1998;3:886–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine Preventable Diseases: Varicella. [accessed on January 15, 2019]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/varicella.html .

- 68.Lopez A, Marin M. Strategies for the control and investigation of Varicella Outbreaks manual. 2008. [accessed on June 12, 2018]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/outbreaks/manual.html .

- 69.Rao BL. Epidemiology and control of influenza. Natl Med J India. 2003;16:143–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.National Institute of Virology Commemorative Compendium. Respiratory viral diseases. Golden Jubilee Publication; 2004. p. 201. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Paules C, Subbarao K. Influenza. Lancet. 2017;390:697–708. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moghadami M. A narrative review of influenza: A seasonal and pandemic disease. Iran J Med Sci. 2017;42:2–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.World Health Organization. Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003. [accessed on June 12, 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/table2004_04_21/en/

- 74.World Health Organization. The operational response to SARS. [accessed on April 11, 2019]. Available from: https://www.who.int/csr/sars/goarn2003_4_16/en/

- 75.World Health Organization. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) [accessed on June 12, 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/

- 76.World Health Organization. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) [accessed on April 11, 2019]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/

- 77.Cowling BJ, Park M, Fang VJ, Wu P, Leung GM, Wu JT. Preliminary epidemiological assessment of MERS-CoV outbreak in South Korea, May to June 2015. Euro Surveill Bull Eur Sur Mal Transm Eur Commun Dis Bull. 2015;20:7–13. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2015.20.25.21163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.World Health Organization. Influenza (Avian and other zoonotic) [accessed on April 11, 2019]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(avian-and-other-zoonotic)

- 79.Karron RA, Black RE. Determining the burden of respiratory syncytial virus disease: The known and the unknown. Lancet. 2017;390:917–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31476-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nair H, Nokes DJ, Gessner BD, Dherani M, Madhi SA, Singleton RJ, et al. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1545–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60206-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.World Health Organization. Influenza: WHO Global RSV surveillance pilot - objectives. [accessed on April 11, 2019]. Available from: https://www.who.int/influenza/rsv/rsv_objectives/en/

- 82.Jauréguiberry S, Tattevin P, Tarantola A, Legay F, Tall A, Nabeth P, et al. Imported Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4905–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4905-4907.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chamberlain J, Cook N, Lloyd G, Mioulet V, Tolley H, Hewson R. Co-evolutionary patterns of variation in small and large RNA segments of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:3337–41. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81213-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Anagnostou V, Papa A. Evolution of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9:948–54. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Centers for Disease Control. Management of patients with suspected viral hemorrhagic fever. MMWR Suppl. 1988;37:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mishra AC, Mehta M, Mourya DT, Gandhi S. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in India. Lancet. 2011;378:372. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60680-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yadav PD, Gurav YK, Mistry M, Shete AM, Sarkale P, Deoshatwar AR, et al. Emergence of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Amreli district of Gujarat state, India, June to July 2013. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;18:97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mourya DT, Yadav PD, Shete AM, Sathe PS, Sarkale PC, Pattnaik B, et al. Cross-sectional serosurvey of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus IgG in livestock, India, 2013-2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1837–9. doi: 10.3201/eid2110.141961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Appannanavar SB, Mishra B. An update on crimean congo hemorrhagic fever. J Glob Infect Dis. 2011;3:285–92. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.83537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.World Research and Development Blueprint. 2018 Annual review of diseases prioritized under the Research and Development Blueprint: Informal Consultation. Geneva: WHO; 2018. [accessed on April 11, 2019]. Available from: http://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/2018prioritization-report.pdf?ua=1 . [Google Scholar]

- 91.Munivenkatappa A, Sahay RR, Yadav PD, Viswanathan R, Mourya DT. Clinical & epidemiological significance of Kyasanur forest disease. Indian J Med Res. 2018;148:145–50. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_688_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mourya D, Yadav P, Patil D. Highly infectious tick-borne viral diseases: Kyasanur forest disease and Crimean-Congo hemorrh agic fev er in India. WHO South East Asia J Public Health. 2014;3:8–21. doi: 10.4103/2224-3151.206890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kiran SK, Pasi A, Kumar S, Kasabi GS, Gujjarappa P, Shrivastava A, et al. Kyasanur forest disease outbreak and vaccination strategy, Shimoga district, India, 2013-2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:146–9. doi: 10.3201/eid2101.141227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]