Abstract

We report a near-infrared fluorescent probe A for the ratiometric detection of cysteine based on FRET from a coumarin donor to a near-infrared rhodamine acceptor. Upon addition of cysteine, the coumarin fluorescence increased dramatically up to 18-fold and the fluorescence of the rhodamine acceptor decreased moderately by 45% under excitation of the coumarin unit. Probe A has been used to detect cysteine concentration changes in live cells ratiometrically and to visualize fluctuations in cysteine concentrations induced by oxidation stress through treatment with hydrogen peroxide or lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Finally, probe A was successfully applied for the in vivo imaging of Drosophila melanogaster larvae to measure cysteine concentration changes.

Keywords: Drosophila melanogaster larvae, fluorescent probes, mitochondria, near-infrared ratiometric imaging, theoretical computation

Graphical Abstract

See the light: A fluorescent probe based on coumarin as a donor and a near-infrared rhodamine acceptor has been developed for the sensitive ratiometric detection of Cys and visualization of fluctuations in Cys concentrations induced by oxidation stress through treatment with hydrogen peroxide or lipopolysaccharide. The probe was successfully applied for the in vivo imaging of cysteine concentration changes in D. melanogaster larvae.

Introduction

Biothiols, such as cysteine (Cys), homocysteine (Hcy), and glutathione (GSH) exert important roles in redox homeostasis, metabolism, protein synthesis, signal transduction, post-translational modification, and metabolism.[1] Biothiol deficiency is associated with different disorders such as liver damage, lethargy, neurotoxicity, slow growth, hematopoiesis, skin lesions, as well as neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.[1d,e] Many fluorescent probes have been developed to detect biothiols.[1b,2] Most of them are intensity-based probes and suffer from systematic errors caused by variations in the probe concentration, fluctuations of the radiation light, as well as different functioning locations and environments within cells.[2a–d] Ratiometric fluorescent probes have been developed to overcome systematic errors by introducing built-in internal fluorophores and using FRET or through-bond energy-transfer (TBET) strategies.[3] The near-infrared fluorophores have the advantage of unique ratiometric and near-infrared imaging features such as deep-tissue penetration, low cellular and tissue fluorescence background, and reduction of probe photobleaching.[3a,4] However, ratiometric fluorescent probes for cysteine detection with near-infrared emissions are currently limited to a few examples.[5] Herein, we detail a near-infrared fluorescent probe based on the FRET strategy for the ratiometric selective detection of Cys and Hcy over GSH in live cells by employing coumarin as a donor and near-infrared rhodamine as an acceptor with a piperazine-tethered spacer. We chose coumarin and the near-infrared rhodamine derivative because of their excellent optical properties, including outstanding photostability, high absorption coefficients, and high fluorescence quantum yields.[6] Ratiometric fluorescence sensing of Cys and Hcy is achieved by manipulating changes in the π-conjugation of the rhodamine acceptor with a phenyl thioester molecular switch in response to biothiols, since the phenyl thioester rapidly binds to Cys and Hcy through a substitution reaction with the phenyl thioester to form spirolactam ring configurations (Scheme 1). In the absence of Cys or Hcy and when excited at 440 nm, probe A shows two well-defined fluorescence peaks corresponding to the weak fluorescence from the coumarin donor and a strong fluorescence from the rhodamine acceptor, presumably because of highly efficient energy transfer from the coumarin donor to the rhodamine acceptor. The gradual addition of Cys results in a significant decrease in the fluorescence from the rhodamine acceptor and a corresponding increase in the fluorescence from the coumarin donor because the nonfluorescent closed-ring spirolactam structure is formed on the rhodamine acceptor and the reaction with Cys results in a fluorescence quenching of the rhodamine acceptor. This also effectively prevents energy transfer from the coumarin donor to the rhodamine acceptor. The probe displays less-sensitive ratiometric fluorescence responses to Hcy and insignificant responses to glutathione (Scheme 1). The probe has been applied to determine changes in the cysteine concentration in HeLa cells and Drosophila melanogaster larvae.

Scheme 1.

Fluorescent probe A and its structural responses to biothiols.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis

The synthetic route to probe A is shown in Scheme 2. 7-(Diethylamino)coumarin-3-carboxylic acid (2) was coordinated to 4’-piperazinoacetophenone (1) through an amide bond, thereby affording compound 3. A near-infrared rhodamine derivative bearing a coumarin donor (5) was prepared by condensation of 3 with 2-(4-diethylamino-2-hydroxybenzoyl)benzoic acid (4) in sulfuric acid at high temperature.[7] Our approach effectively overcomes a challenging separation issue by preparing a highly polar near-infrared rhodamine derivative bearing a piperazine residue.[6] Probe A was prepared by introducing the biothiol-sensing switch of a phenyl thioester into the rhodamine acceptor by coupling 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzenethiol (6) with dye intermediate 5. We chose dye 5 to develop the ratiometric fluorescent probe A for cysteine because it has a much greater fluorescence quantum yield than other near-infrared coumarin hybrid dyes.[8] Probe A was characterized by NMR spectroscopy and high-resolution mass spectrometry (Figures S1–S5 in the Supporting Information).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis route to probe A.

Optical responses of probe A to cysteine

Probe A shows two strong well-defined absorption peaks at 420.7 and 606.9 nm, which correspond to the absorption wavelengths of the coumarin donor and the rhodamine acceptor, respectively (Figure 1 A). The gradual addition of Cys leads to a gradual decrease in the absorbance of the rhodamine acceptor and almost no change in the absorbance of the coumarin donor because of the formation of a closed spirolactam ring on the rhodamine acceptor, which significantly reduces the π-conjugation in the rhodamine moiety. The probe displays two well-defined fluorescence peaks, with a strong fluorescence for the rhodamine acceptor at 645 nm and a weak fluorescence peak for the coumarin donor at 467 nm in the absence of Cys (Figure 1 B) because of the highly efficient energy transfer from the coumarin donor to the rhodamine acceptor. The efficiency of this energy transfer was calculated to be 95.1 %. The probe shows a large pseudo-Stokes shift of 224 nm, that is, the difference between the coumarin absorption and the rhodamine fluorescence peaks. Upon gradual addition of Cys, the fluorescence of the rhodamine acceptor gradually decreases while there is a concomitant gradual increase in the fluorescence of the coumarin donor. This sensitive ratiometric change in the fluorescence response of the probe to Cys arises from a suppressed energy transfer from the coumarin donor to the rhodamine acceptor as a result of the formation of a closed spirolactam ring on the rhodamine acceptor after it reacts with Cys (Scheme 1). The fluorescence intensity ratios of rhodamine to coumarin increase from 0.235 to 4.237, with a final enhancement factor of 18-fold upon addition of Cys. The probe shows similar ratiometric responses to Hcy, with much smaller changes in the absorbance and a decrease in the fluorescence of the rhodamine acceptor, as well as an increase in the fluorescence of the coumarin donor (Figure S6). This observation was further confirmed by the fluorescence spectra of the probe in the absence and presence of Cys and Hcy under excitation of the rhodamine acceptor at 560 nm (Figures S7 and S8). Probe A also exhibits insignificant responses to GSH, since the reaction of the probe with GSH retains the same thioester bond without changing the π-conjugation of the rhodamine acceptor and affecting the efficiency of the energy transfer from the coumarin donor to the rhodamine acceptor. The reaction products of the probe with Cys, Hcy, and GSH were confirmed by mass spectrometry (Figures S9–S11).

Figure 1.

A) Absorption and B) fluorescence spectra of 5 μm probe A in the absence and presence of various concentrations of Cys in pH 7.4 buffer containing 30% ethanol under excitation at 440 nm.

Theoretical calculations

We also examined the electronic properties of probe A and its reaction products with Cys and GSH through theoretical calculations, using an exchange correlation (xc) functional DFT/ TPSSH[9] and with atoms defined at the split-valence triple-ζ plus polarization function (TZVP[10]) implemented, using the Gaussian 16[11] suite of programs. Interestingly, reasonable agreement between theoretical and experimental data were obtained; for probe A, calculated (expt.) at 552 (607), 393 (421); A-1 at 393 (421); A-3 at 563, 393 nm. These values are within the expected error range of 0.20–0.25 eV.[12] Full details are available in the Supporting Information (Figures S12–S23). The isolated nature of the transitions can be observed in the difference density illustrations shown in Figure 2. In probe A, the ES2 transition at 552 nm has a 95.9% contribution from the rhodamine moiety, and at 393 nm, that is, ES8, 88.4% is contributed from a transition localized on the coumarin sector. A-1 has only one transition with a significant oscillator strength, and this was localized on the coumarin moiety with a 96.4% contribution. For A-3, ES2 (Figure 2) is localized on the rhodamine moiety at 95.2%, but for ES10, 17.3% is due to a transition from the coumarin to the rhodamine moiety, while 5.2% is from an LCAO on rhodamine to coumarin, and 74.4% is localized solely on the coumarin. The results of the calculations confirm that for probe A, excitation at 440 nm (Figure 1), which leads to fluorescence from the rhodamine moiety, does not occur as a consequence of orbital transmission through bonds.

Figure 2.

Illustrations of the current density difference as isosurfaces of the probes A, A-1, and A-3, as indicated for the excited states (ES) and the calculated (and experimental) wavelengths. The composition of specific ES, together with percentage contributions, are indicated. Drawings of the numbered LCAOs are available in the Supporting Information. Red areas indicate values for a different density of –5.000 e−5 and blue areas are for 5.000 e−5, see image scale at the top of the illustration.

Kinetic and thermodynamic study

Probe A responds quickly to Cys and Hcy; the fluorescence ratio values of the rhodamine acceptor to the coumarin donor plateaus within 20 minutes in the presence of 30 equivalents of Cys or Hcy (Figure 3 A). The pseudo-first-order rate constants (k) for Cys and Hcy were determined as 0.08572±0.00622 min−1 and 0.07364±0.00630 min−1, respectively (Figure S24). The reaction rate constant for Hcy is lower than that of Cys due to the facile formation of a five-membered ring intermediate by Cys attack being more favored than the intra-molecular attack by an amino group and formation of a six-membered ring compound with Hcy. The fluorescence ratio values of the rhodamine acceptor to the coumarin donor show a linear relationship with Cys concentrations from 25 to 150 μm at 20 min, with a detection limit of 1.5×10−6m (Figure 3B, Figure S25B). Furthermore, the detection limit of Hcy is calculated to be 1.3×10−5 m (Figure S25 A), which is much higher than that of Cys, thus indicating that probe A could serve as a ratiometric fluorescent tool to selectively detect Cys over other biothiols.

Figure 3.

A) Reaction time responses of 5 μm probe A to 30 equiv Cys and Hcy in pH 7.4 buffer containing 30% ethanol under excitation at 440 nm. B) Linear relationship of the fluorescence intensity ratio of the rhodamine/ coumarin fluorescence to Cys concentration in pH 7.4 buffer containing 30% ethanol under excitation at 440 nm for 20 min.

Selectivity, photostability, and pH effects

We also investigated the selectivity of the probe to Cys or Hcy in the presence of different biological species, such as amino acids (Figure S26), anions (Figure S27), and cations (Figure S28). The results suggest that the probe displays high selectivity to Cys and Hcy over other species. We further evaluated the photostability of fluorescent probe A in a time-dependent fluorescence experiment. The fluorescence ratio between the coumarin donor and rhodamine acceptor exhibited only a very small change after illumination at 400 nm for 2 h, with a decrease of less than 8% compared to the initial intensity (Figure S29). The fluorescence intensity of the rhodamine acceptor showed a less than 5% decrease after 2h excitation at 560 nm (Figure S30). Thus, probe A is highly resistant to photo-bleaching and has good photostability. We also studied the effect of the pH value on cysteine sensing in physiological ranges. The results presented in Figures S31 and S32 indicate that there are small and insignificant changes in the probe fluorescence and, more importantly, the fluorescence responses of the probe to cysteine are not significantly affected by the pH value between 5.0 and 8.5. Therefore, probe A can accurately sense cysteine within this pH range from 5.0 to 8.5.

Cell viability and confocal fluorescence imaging of HeLa cells

We further investigated the cytotoxicity of the probe to HeLa cells by standard MTT assays. The cell viability is more than 90% on treatment with 50 μm probe A (Figure S33), thus affirming that probe A displays low cytotoxicity toward HeLa cells.

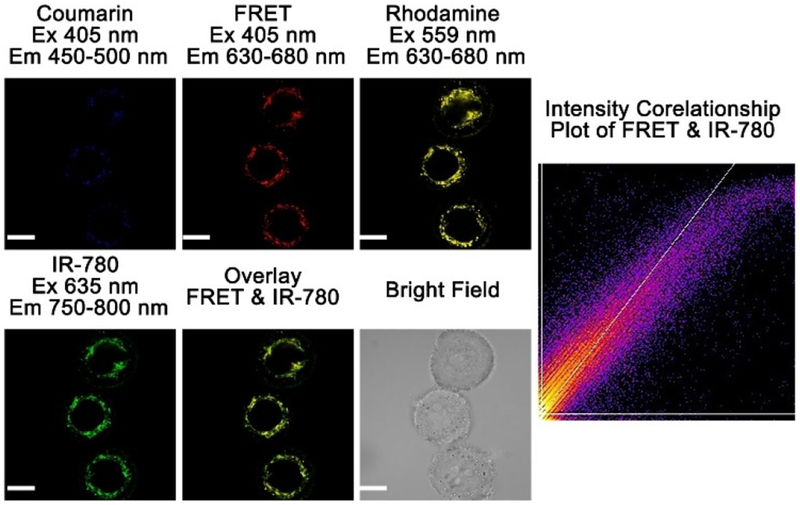

As probe A is positively charged, we suspected that it may target mitochondria through electrostatic interactions with negative electric potentials across the inner mitochondrial membranes. To test this hypothesis, we carried out intracellular colocalization experiments by co-staining HeLa cells with the probe and a mitochondria-targeting cyanine dye (IR-780). Strong cellular fluorescence of the probe’s rhodamine acceptor was observed under excitation at 405 nm and 559 nm, and weak fluorescence of the probe’s coumarin donor was observed under excitation at 405 nm (Figure 4). The weak fluorescence of the donor is due to the low intracellular Cys concentration in live cells. The Pearson colocalization coefficient of the probe with a cyanine dye (IR-780) is high at 0.94, which indicates that probe A stays in the mitochondria with the cyanine dye IR-780.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence imaging of HeLa cells with 5 μm probe A under excitation at 405 nm or 559 nm, and with 10 μm cyanine dye (IR-780) under excitation at 635 nm. Scale bar: 20 μm.

We investigated whether the probe can detect Cys in live cells by incubating HeLa cells with 10 μm of the probe at 37°C for 30 min. Both the blue fluorescence from the coumarin donor and the near-infrared fluorescence (red and yellow channels) were observed (Figure 5). However, when HeLa cells were incubated with different concentrations of Cys from 100 to 500 μm under the coexistence of endogenous Cys, followed by further incubation of the cells with probe A, the cellular blue fluorescence of the coumarin donor significantly increased proportionally with the increased Cys concentration, while the near-infrared fluorescence from the rhodamine acceptor decreased significantly. In addition, overlapped images of the fluorescence in the blue and red channels show significant color changes from pink to blue when the Cys concentration is increased from 100 μm to 500 μm. Ratiometric images of the probe (where coumarin fluorescence is divided by the rhodamine fluorescence) show considerable color changes from bluish red to white before and after cysteine treatment, respectively (Figure S34). These findings suggest that exogenous cysteine transported to mitochondria further reacts with the probe in mitochondria, thereby resulting in a closed spirolactam ring structure in the rhodamine acceptor and leading to an increase in the coumarin fluorescence and decrease in the rhodamine fluorescence under cysteine treatment. The cellular fluorescence responses of the probe to Cys are similar to the fluorescence responses in aqueous solution (Figure 1). We also conducted a control experiment by pre-treating HeLa cells with 1.0 mm NEM (N-ethylmaleimide) to remove intracellular endogenous biothiols, before the cells were incubated with the probe. A slight decrease in the blue fluorescence of the probe’s coumarin donor was observed with a significant increase in the near-infrared fluorescence of the probe’s rhodamine acceptor in the red and yellow channels. This indicates that NEM treatment causes a decrease in the biothiol concentration through an addition reaction of NEM with a mercapto group on the endogenous biothiols (Figure 5). We also investigated whether probe A could detect Hcy in HeLa cells. Similar results to sensing cysteine in HeLa cells were obtained (Figure S34), which is in agreement with the fluorescence responses of the probe to Hcy in buffer solutions (Figure 3).

Figure 5.

Fluorescence imaging of HeLa cells with 10 μm probe A in the absence and presence of different concentrations of Cys or under treatment with NEM. Scale bar: 50 μm.

We further studied concentration changes of Cys on HeLa cells that were oxidatively stress-induced by applying different concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (Figure 6). Gradual increases in the concentration of hydrogen peroxide from 20 to 100 μm led to a significant decrease in the cellular blue fluorescence from the coumarin donor, and a considerable increase in the cellular near-infrared fluorescence of the rhodamine acceptor in the red and yellow channels under excitation at 405 and 559 nm. Additionally, ratiometric images of the blue channel over the red channel also show significant color changes from bluish pink to an extremely weak blue. This is due to decreases in the cysteine concentration under oxidative stress when the hydrogen peroxide concentration is increased from 20 to 100 μm. Hydrogen peroxide converts the mercapto group on cysteine into a disulfide group through oxidation, resulting in a decrease in the concentration of endogenous cysteine in live cells. As a result, the coumarin fluorescence decreases in the blue channel while the near-infrared rhodamine fluorescence in the red channel increases under oxidative stress on treatment with hydrogen peroxide (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Fluorescence imaging of HeLa cells with 10 μm probe A before and after treatment with hydrogen peroxide. Scale bar: 50 μm. Ratiometric images were obtained by using ImageJ.

The decreases in the endogenous Cys concentration under oxidative stress in the presence of nitric oxide can lead to the effective oxidization of biothiols. Moreover, we studied changes in the intracellular Cys concentration under the stimulus of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), as it was reported that lipopolysaccharide treatment can generate nitric oxide and create oxidative stress in live cells to oxidize biothiols.[13] LPS treatment of HeLa cells results in a decrease in the coumarin fluorescence and an increase in the rhodamine fluorescence as a result of a decrease in the endogenous cysteine concentration due to the oxidation of cysteine by nitric oxide. Ratiometric images of the blue channel over the red channel show dramatic color changes from reddish blue to weak blue before and after LPS treatment (Figure 7). These results convincingly demonstrate that the probe possesses high cell permeability and is capable of detecting intracellular Cys changes ratiometrically with visible and near-infrared channels (Figures 5–7).

Figure 7.

Fluorescence imaging of HeLa cells with 10 μm probe A before and after treatment with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Scale bars: 50 μm. Ratiometric images were obtained by using ImageJ.

In vivo experiments with D. melanogaster first-instar larvae

Finally, we conducted fluorescence imaging of live Drosophila melanogaster first-instar larvae in the absence and presence of different concentrations of cysteine (Figure 8). D. melanogaster does not have a fluorescence background and it possesses a very low cysteine concentration: probe A reveals very weak fluorescence from the coumarin donor and highly intense fluorescence from the rhodamine acceptor. The probe locates in the epidermis and tracheae (Figure 8). However, gradual increases in the incubation concentrations of Cys with the larvae result in increases in the coumarin fluorescence and decreases in the fluorescence from the rhodamine acceptor because intake cysteine into the larvae further reacted with the probe, thereby resulting in a closed nonfluorescent spirolactam ring of the rhodamine acceptor and preventing effective FRET from the coumarin donor to the rhodamine acceptor (Figure 8). Ratiometric images (ratio of blue channel to red channel) of the larvae incubated with probe A and increasing cysteine concentrations show dramatic pseudocolor changes from reddish blue to reddish white (Figure S41), thus indicating that increases in the cysteine concentrations lead to the increases in the coumarin fluorescence and decreases in the rhodamine fluorescence. The coumarin fluorescence of the probe in the blue channel decreases and the rhodamine near-infrared fluorescence in the red and yellow channel increases after the larvae were first incubated with cysteine and the probe, and then further treated with hydrogen peroxide (Figure S42). This suggests that treatment with hydrogen peroxide also reduces the cysteine concentration in the larvae. These results indicate that probe A can be successfully applied to live tissues to detect Cys concentrations.

Figure 8.

Fluorescence imaging of D. melanogaster first-instar larvae with 20 μm probe A in the absence and presence of different concentrations of cysteine. Scale bar: 200 μm.

Conclusion

We have developed a fluorescent probe A based on coumarin as a donor and a near-infrared rhodamine acceptor for the sensitive ratiometric detection of Cys. The probe offers ratiometric detection of the Cys concentration and fluctuation in live cells with a self-calibration capability under oxidative stress through treatment with hydrogen peroxide and LPS, and can be utilized for the visualization of cysteine changes in D. melanogaster larvae in the visible and near-infrared channels.

Experimental Section

Instruments and chemicals:

A 400 MHz Inova NMR spectrometer was employed to record 1H NMR spectra at 400 MHz and 13C NMR spectra at 100 MHz. Chemical shifts of intermediates and probes were determined by using solvent residual peaks as internal standards (1H: δ = 7.26 for CDCl3, δ = 2.50 for [D6]DMSO; 13C: δ = 77.3 for CDCl3). High-resolution mass spectra were recorded on an electrospray ionization mass spectrometer. Absorption spectra were obtained using a PerkinElmer Lambda 35 UV/Vis spectrometer, and conventional fluorescence spectra were obtained using a Jobin Yvon Fluoromax-4 spectrofluorometer. IR spectra were obtained using a PerkinElmer FT-IR Spectrometer. The MTT assay was performed on a BioTek ELx800 absorbance microplate reader. An Olympus IX81 inverted microscope was used for cellular imaging. All reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification.

Optical measurement method:

The UV/Vis absorption spectra of probe A in the presence of thiols, for the first-order kinetic plot, and to establish selectivity, photostability, and linear ratio relationship measurements were obtained in the range 300 to 800 nm with increments of 1 nm. The corresponding fluorescence spectra were collected at an excitation wavelength of either 400 nm for donor or 560 nm for acceptor excitation. The concentration of the probe in each sample was 5 μm. Cresyl violet (Φf=0.56 in EtOH) was used as the reference standard to determine the fluorescence quantum yields of probe A in ethanol and buffer solutions. Quinine sulfate (Φf=0.546 in 1 n H2SO4) was used as the reference standard to determine the fluorescence quantum yield of probe A after reaction with thiols. All samples and references were freshly prepared under similar conditions. The fluorescence quantum yields were calculated using Equation (1):

| (1) |

The subscripts “st” and “X” stand for standard and test, respectively, Φ is the fluorescence quantum yield, “Grad” means the gradient from the plot of integrated fluorescence intensity versus absorbance, and η is the refractive index of the solvent.

Cell culture and MTT cytotoxicity assay:

HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Fisher Scientific) at 37°C in a humid atmosphere containing 5% CO2. HeLa cells were subcultured at 80% confluence using 0.25% trypsin (w/v) (Fisher Scientific) every other day. A standard MTT assay was applied to determine the cytotoxicity of probe A. In detail, the cells were seeded in 96-well plates at an initial density of 4000 cells per well, with 100 μL DMEM medium per well. After seeding for 24 h in the 96-well plate, the medium was replaced by different concentrations of probe A (0, 5, 10, 15, 25, 50 μm solutions in fresh culture medium, 100 μL/well) for 48 h. After that, the cells were incubated for 4 h with the tetrazolium salt dye 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide at a final concentration of 500 μg mL−1, whereupon metabolically active cells reduced the dye to the water-insoluble purple formazan dye. The dark purple crystals were dissolved with DMSO and the cell viability rate determined by measuring the absorbance at 490 nm (BioTek ELx800). The cell viability rate was calculated by Vrate = (A–AB)/(AC–AB) × 100%, where A is the absorbance of the experimental group, AC is the absorbance of the control group (cell medium used as control), and AB is the absorbance of the blank group (no cells). Data were illustrated graphically, with each data point calculated from an average of three wells.

Cell confocal fluorescence microscopy imaging:

Cells were seeded in confocal glass-bottom dishes with 105 cells per dish and cultured for 24 h. Probe A was added to each dish and cultured for 30 min. Cells were then washed with PBS (pH 7.4) twice, and 1 mL of PBS was then added before imaging. The fluorescence of probe A was determined based on excitation with a 405 nm or 559 nm laser, with emission spectra recorded at 450–500 or 630–680 nm, respectively. The fluorescence of the cyanine dye IR-780 channel was determined under excitation at 635 nm and its emission collected between 750 and 800 nm. A confocal fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX 81) was used to take images of the HeLa cell and an Olympus FV10-ASW 3.1 viewer, ImageJ, and Image Pro 6 were used to process the image data.

In vivo experiments with D. melanogaster first-instar larvae:

In order to test the probe in D. melanogaster, a nine-well glass viewing dish was used. The larvae were treated in four different ways: 1) Larvae were submerged in 500 μL distilled water for 4h and washed three times in 500 μL distilled water for the negative control. 2) Larvae were incubated with 20 μm probe for 2 h and washed three times with 500 μL distilled water. 3) larvae were submerged in 500 μL 1 mm cysteine for 2 h, washed three times with 500 μL distilled water, and incubated for an additional 2 h in distilled water. 4) Larvae were submerged in 500 μL of 50 pM, 100 pM, 200 μm, or 1 mM cysteine for 2 h, washed three times in 500 μL distilled water, incubated for an additional 2 h with 20 μm probe, and then washed three times in 500 μL distilled water. For each sample, ten freshly hatched first-instar larvae were used. After the incubation, the larvae were transferred with water onto a microscope slide and then covered with a cover slip. The larvae were then immediately analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy (Olympus IX 81). The confocal microscopy conditions of the channels were identical to those utilized for the HeLa cells images.

Synthesis of 3-(4-(4-acetylphenyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)-7-(diethylamino)-2H-chromen-2-one (3):

A mixture of 1-(4-(piperazin-1-yl)phenyl)ethan-1-one (312 mg, 3 mmol), 7-(diethylamino)-2-oxo-2H-chromene-3-carboxylic acid (861 mg, 3.3 mmol), BOP reagent (1.46 g, 3.3 mmol), and trimethylamine (1 mL) in 20 mL anhydrous CH2Cl2 was stirred for 8 h at room temperature (Scheme 2). The mixture was then washed with water and then brine, dried with anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was purified by flash column chromatography under gradient elution with hexanes/ethyl acetate (1:1) to yield compound 3 as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.89-7.78 (m, 3H), 7.27 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1 H), 6.83 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2 H), 6.56 (dd, J = 6.6, 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 6.46-6.40 (m, 1 H), 3.85 (s, 2H), 3.52 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 2H), 3.39 (q, J = 5.2 Hz, 8H), 2.48 (s, 3H), 1.21-1.13 ppm (m, 6H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 196.63, 165.27, 159.32, 157.46, 153.89, 151.93, 145.81, 130.55, 128.19, 115.79, 113.99, 109.63, 107.89, 97.04, 47.23, 45.26, 42.25, 26.52, 12.75 ppm. LCMS(ESI): calcd for C26H29N3O4: 447.2 [M]+; found: 448.1 [M+H]+.

Synthesis of N-(4-(2-carboxyphenyl)-2-(4-(4-(7-(diethylamino)-2-oxo-2H-chromene-3-carbonyl)piperazin-1-yl)phenyl)-7H-chromen-7-ylidene)-N-ethylethanaminium (5):

After compounds 3 (447 mg, 1 mmol) and 4 (313 mg, 1 mmol) had been added to methanesulfonic acid (6 mL), the reaction mixture was stirred at 100 °C for 6h under argon (Scheme 2). The mixture was then added to 20 mL water and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3×100 mL). The organic layers were collected, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The mixture was purified by flash column chromatography using CH2Cl2/menthol (40:1) to yield compound 5[6] as a blue solid.

Synthesis of fluorescent probe A:

Compound 5 (75.3 mg, 0.1 mmol), compound 6 (26.9 mg, 0.11 mmol), EDC (21 mg, 0.11 mmol), and DMAP (13.4 mg, 0.11 mmol) were added to anhydrous CH2Cl2 (20 mL) and stirred for 8 h at room temperature. The mixture was then washed with water, then brine, dried with anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and then evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was purified by flash column chromatography using a mixture of CH2Cl2/methanol (30:1) as eluent to give probe A as a blue solid (Scheme 2). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 8.24–8.09 (m, 3H), 7.93–7.84 (m, 2H), 7.86–7.73 (m, 2 H), 7.71–7.63 (m, 3H), 7.46 (s, 1 H), 7.33–7.25 (m, 2H), 7.13–6.94 (m, 4H), 6.59 (dd, J = 6.7, 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 6.46 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1 H), 3.87 (s, 2 H), 3.77–3.51 (m, 9H), 3.42 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 4H), 1.31 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 6H), 1.21 ppm (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 188.70, 166.97, 165.53, 159.50, 159.38, 158.22, 157.54, 155.05, 154.92, 152.07, 145.99, 135.71, 134.88, 133.74, 132.87, 132.53, 131.61, 131.20, 130.25, 129.25, 127.62, 117.32, 115.51, 114.87, 114.39, 109.73, 109.49, 107.98, 97.14, 46.27, 45.28, 42.20, 12.82, 12.76 ppm. LCMS(ESI): calcd for C52H47F6N4O5S: 953.31659 [M]+; found: 953.31607.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R15GM114751 (to H.Y.L.). Superior, a high-performance computing infrastructure at Michigan Technological University, was used to obtain results presented in this publication.

Footnotes

Supporting information and the ORCID identification number for one of the authors of this article can be found under: https://doi.org/10.1002/cbic.201900071.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].a) Yue YK, Huo FJ, Ning P, Zhang YB, Chao JB, Meng XM, Yin CX, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 3181–3185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lim CS, Masanta G, Kim HJ, Han JH, Kim HM, Cho BR, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 11132–11135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Liu J, Sun YQ, Huo YY, Zhang HX, Wang LF, Zhang P, Song D, Shi YW, Guo W, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 574–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Zhang S, Ong CN, Shen HM, Cancer Lett. 2004, 208, 143–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Townsend DM, Tew KD, Tapiero H, Biomed. Pharmacother. 2004, 58, 47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Zhang JJ, Wang JX, Liu JT, Ning LL, Zhu XY, Yu BF, Y Liu X, Yao XJ, Zhang HX, Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 4856–4863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yuan L, Lin WY, Zheng KB, Zhu SS, Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 1462–1473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Chen X, Zhou Y, Peng XJ, Yoon J, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 2120–2135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Jung HS, Chen XQ, Kim JS, Yoon J, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6019–6031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Yang XP, Liu WY, Tang J, Li P, Weng HB, Ye Y, Xian M, Tang B, Zhao YF, Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 11387–11390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Liu Y, Yu DH, Ding SS, Xiao Q, Guo J, Feng GQ, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 17543–17550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Xue SH, Ding SS, Zhai QS, Zhang HY, Feng GQ, Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 68, 316–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Huang YL, Zhou Q, Feng Y, Zhang W, Fang GS, Fang M, Chen M, Xu CZ, Meng XM, Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 10495–10498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) He LW, Yang XL, Xu KX, Y Lin W, Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 9567–9573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Niu WF, Guo L, Li YH, Shuang SM, Dong C, Wong MS, Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 1908–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ren TB, Zhang QL, Su DD, Zhang XX, Yuan L, Zhang XB, Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 5461–5466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Lv HM, Yang XF, Zhong YG, Guo Y, Li Z, Li H, Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 1800–1807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Qi SJ, Liu WM, Zhang PP, Wu JS, Zhang HY, Ren HH, Ge JC, Wang PF, Sensors Actuators B 2018, 270, 459–465. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cheng D, Pan Y, Wang L, Zeng ZB, Yuan L, Zhang XB, Chang YT, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 285–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Wang JB, Xia S, Bi JH, Zhang YB, Fang MX, Luck RL, Zeng YB, Chen TH, Lee HM, Liu HY, J. Mate. Chem. B 2019, 7, 198–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang YB, Bi JH, Xia S, Mazi W, Wan SL, Mikesell L, Luck RL, Y Liu H, Molecules 2018, 23, 2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Niu GL, Zhang PP, Liu WM, Wang MQ, Zhang HY, Wu JS, Zhang LP, Wang PF, Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 1922–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fang MX, Adhikari R, Bi JH, Mazi W, Dorh N, Wang JB, Conner N, Ainsley J, Karabencheva-Christova TG, Luo FT, Tiwari A, Y Liu H, J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 9579–9590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tao JM, Perdew JP, Staroverov VN, Scuseria GE, Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 146401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Schäfer A, Horn H, Ahlrichs R, J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 97, 2571–2577. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Farkas O, Foresman JB, Fox DJ, Gaussian, Inc, Wallingford CT, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Adamo C, Jacquemin D, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 845–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Vegesna GK, Sripathi SR, Zhang JT, Zhu SL, He WL, Luo FT, Jahng WJ, Frost M, Liu HY, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 4107–4112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.