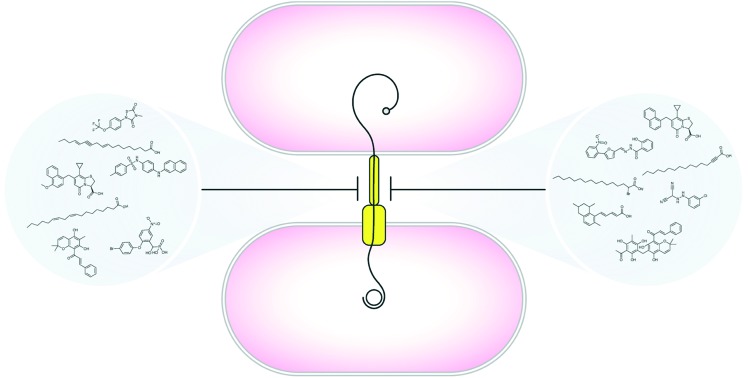

The search for new ammunition to combat antibiotic resistance has uncovered diverse inhibitors of the bacterial type IV secretion system.

The search for new ammunition to combat antibiotic resistance has uncovered diverse inhibitors of the bacterial type IV secretion system.

Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance is a mounting global health crisis that threatens a resurgence of life-threatening bacterial infections. Despite intensive drug discovery efforts, the rate of antimicrobial resistance outpaces the discovery of new antibiotic agents. One of the major mechanisms driving the rapid propagation of antibiotic resistance is bacterial conjugation mediated by the versatile type IV secretion system (T4SS). The search for therapeutic compounds that prevent the spread of antibiotic resistance via T4SS-dependent mechanisms has identified several promising molecular scaffolds that disrupt resistance determinant dissemination. In this brief review, we highlight the progress and potential of conjugation inhibitors and anti-virulence compounds that target diverse T4SS machineries. These studies provide a solid foundation for the future development of potent, dual-purpose molecular scaffolds that can be used as biochemical tools to probe type IV secretion mechanisms and target bacterial conjugation in clinical settings to prevent the dissemination of antibiotic resistance throughout microbial populations.

Introduction

The battle against antibiotic resistance is one of the greatest challenges facing global healthcare. Common bacterial pathogens are becoming increasingly resistant to existing antimicrobial therapeutics due to strong selective pressures that establish recalcitrant bacterial populations.1–5 Unfortunately, the rapid increase in antibiotic resistance has significantly outpaced the development of new antibiotic agents leading to an accelerated public health crisis.6 As a result of our diminishing capacity to control bacterial infections, antibiotic-resistant pathogens are projected to cause an estimated 10 million deaths per year globally by 2050,5,7,8 signaling the end of the antibiotic era.

Ineffective clinical stewardship and the overuse of broad-spectrum antimicrobials in animal husbandry and agricultural practices has significantly impacted and reshaped the ecology of microbiota in humans and livestock leading to dysbiosis of the healthy microbiome.1,9–12 Detrimental effects on resident microbiota induced by antibiotic therapy have been linked to a decreased ability to resist invading pathogens, disruption of immune system development, and multiple metabolic diseases.9–12 The spread of plasmids conferring resistance to multiple classes of antibiotics has been especially well-studied in human pathogens. For example, prolonged use of antibiotics has led to alarming rates of antibiotic resistance among global Escherichia coli populations – in 2014, more than 50% of E. coli isolates exhibited resistance to third generation cephalosporins and rapidly mounting resistance to fluoroquinolones and third generation carbapenems.13,14 The ability of antibiotic resistance plasmids to be mobilized across species and genera boundaries is demonstrated by the emergence and spread of blaCTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) genes encoding cephalosporinases that circumvent the action of existing β-lactam antibiotics.15–18 These genes have been rapidly disseminated via both narrow and broad host-range plasmids within Enterobacteriaceae and among opportunistic pathogens including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, and other ESKAPE bacteria (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumonia and Enterobacter species).3,19 Moreover, antibiotic resistance genes are frequently co-localized on self-transmissible plasmids, further promoting the accelerated emergence of multidrug- and pan-resistant bacteria.20

One of the major mechanisms driving the spread of antibiotic resistance is conjugation, a process by which DNA is transferred between bacterial cells through a type IV secretion system (T4SS).21–27 Thus, while current antibiotic therapies largely target essential cellular functions or inhibit bacterial growth, inhibiting T4SS mechanisms represents an attractive alternative strategy to address the mounting threat of antibiotic resistance.14,28–34 In this brief review, we highlight recent advances in the development of specific conjugation inhibitors and versatile small molecules that hinder antibiotic resistance gene dissemination by disarming T4SS machinery.

T4SS architectural diversity

The T4SS superfamily is a diverse group of versatile cargo transport systems harbored by both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.21,23,25–27,35 In contrast to other bacterial secretion systems, T4SSs have the capacity to transport a variety of molecular substrates to target prokaryotic or eukaryotic cells.23,27,34–36 For example, many bacterial pathogens deploy T4SSs to deliver nucleoprotein complexes and monomeric protein virulence determinants directly to mammalian cells during infection.22,23,34 T4SS activity has also been implicated in the formation of biofilms that can render microbial populations impervious to antibiotic intervention, environmental insults, and host defense mechanisms.34,37,38

T4SSs can be divided into three broad subfamilies: (i) DNA conjugation machineries, (ii) DNA-uptake/release systems that exchange nucleic acid with the extracellular milieu, and (iii) effector translocator systems that transport molecular cargo to target cells22,25,27,39 (Fig. 1). The T4SS nanomachine is composed of conserved core complex subunits, as well as species-specific components that afford apparatus specialization and facilitate occupation of specific intra- and extracellular niches.25,26,35,40,41 Accordingly, recent work has unveiled remarkable architectural diversity among paradigmatic conjugation systems and structurally complex effector translocator systems employed by divergent bacteria.22,24,25,42–46 Historically, T4SS machineries have been classified into two major phylogenetic lineages based on similarity to either the virB/virD4 system of Agrobacterium tumefaciens [IVA (T4ASS)] or the tra/trb conjugation system found within Legionella pneumophila and Coxiella burnetii [IVB (T4BSS)].22,27,34,35,47,48 Recent work has focused on characterizing a third T4SS lineage (the type IVC group) found predominately in Gram-positive streptococci.49

Fig. 1. T4SS-dependent mechanisms in diverse bacterial species. A. Conjugative T4SSs unilaterally transfer nucleoprotein complexes into recipient cells. During conjugation, DNA is covalently attached to the relaxase which is translocated to recipient cells through the T4SS apparatus. In recipient cells, transferred DNA is re-circularized and replicated by endogenous cell machinery. B. ComB-mediated uptake of exogenous DNA by H. pylori (left) and DNA release into the extracellular environment for genetic exchange and biofilm formation by Neisseria (right). C. Xanthomonas citri uses T4SS activity to translocate protein toxins into competitor bacterial cells. D. Effector translocator T4SSs are used by various pathogens to deliver diverse effector proteins or nucleoprotein complexes into target eukaryotic cells. Bordetella pertussis delivers pertussis toxin (PT) to the extracellular space via contact-independent secretion mechanisms. T4SS cargo is injected directly into the target host cell by multiple intra- and extracellular bacteria in a contact-dependent manner. This figure was modified from Grohmann et al. (ref. 34).

In Gram-negative bacteria, conjugation machinery consists of bi-membrane spanning macromolecular complexes involved in contact-dependent substrate transfer to recipient cells.27,34,35 The prototypical T4ASS produced by Agrobacterium tumefaciens integrates 11 proteins encoded by the so-called mating pair formation (MPF) genes (termed virB1 through virB11), and the type IV coupling protein (T4CP) VirD4.22,27,34,35,40,50 T4SS architecture is generally consistent across most conjugative systems and includes a periplasmic core complex, an inner membrane-associated platform, hexameric ATPases that drive apparatus biogenesis, and a pilus conduit that assembles to enhance nucleic acid and protein substrate transport to target cells25–27,34,40 (Fig. 2). The process of DNA conjugation is initiated by assembly of the relaxasome [encoded by mobility (MOB) genes] at the origin of transfer (oriT) region of the conjugative plasmid.27,51,52 The ubiquitous ‘relaxase’ enzyme of the relaxasome provides two essential functions required for unilateral DNA transfer – (i) catalysis of a single-stranded break at the nic site within the oriT and the subsequent covalent attachment of the nicked 5′-phosphate; and (ii) recruitment of the nucleoprotein complex to the T4SS channel via interactions with the coupling protein.27,51–54 The mechanism underlying DNA processing by relaxase enzymes is identical in Gram-positive and Gram-negative systems.55,56

Fig. 2. Proposed model of conjugative T4SS architecture in Gram-negative bacteria. Three-dimensional representation (A) and cut-away view (B) of the R388 conjugative T4SS harbored by E. coli. Schematic diagram of the system architecture includes outer membrane (OM) and inner membrane (IM) complexes, as well as inner membrane-associated ATPases (green and tan barrels), and a central pilus that is predicted to span the periplasm (purple spheres). C. The conjugative pilus comprised of VirB2 (purple spheres) and decorated by VirB5 (pilus tip) assembles and extends from the bacterial cell surface to interact with target cells during conjugation events.

Recent work has unveiled the structure and architecture of several Gram-negative T4SS subassemblies and intact conjugation systems. The outer membrane core complex present in Gram-negative systems is formed by VirB7, VirB9, and VirB10.24,25,27,39,57 Biochemical and genetic analyses indicate that the VirB7-VirB9-VirB10 core complex is absent from Gram-positive conjugation systems.27,34 In Gram-negative systems, the inner membrane complex is comprised of VirB4, VirB3, VirB6, VirB8 and a portion of VirB10.26,27,35 The outer and inner membrane subassemblies are connected via a stalk region; however, the composition of the stalk remains unresolved.25–27 The conjugative pilus is assembled into a helical filament comprised of the major pilin VirB2 and decorated by the minor component VirB5.27,58 Formation of the pilus is essential for efficient DNA transfer, and pili are hypothesized to serve as an attachment appendage or conduit through which nucleoprotein complexes are delivered to recipient cells.27,59,60 In some instances, conjugative pili can retract to bring donor and recipient cells into close proximity leading to the formation of cell–cell junctions that promote DNA transfer.27,61,62 To date, a conjugative pilus-like structure has not been observed in Gram-positive T4SS architectures;55,63 thus, the mechanism by which Gram-positive T4SSs establish target cell attachment to trigger mating pair formation is unknown. Apparatus assembly and secretion of T4SS substrates is powered by several ATPases, including VirB4, VirB11, and VirD4.27,34,64,65

The Enterococcus sex pheromone-responsive plasmid pCF10 (conferring resistance to tetracycline)55 and the self-transmissible Inc18 group plasmid pIP50166 (conferring resistance to chloramphenicol and the macrolide/lincosamide/streptogramin group antibiotics)56 originally isolated from Streptococcus agalactiae have served as model systems for understanding T4SS-dependent DNA transfer mechanisms in Gram-positive organisms.55,67,68 In addition to relaxase proteins, motor ATPases, peptidoglycan hydrolases, cell surface adhesins, and channel protein complexes are detected in Gram-positive T4SS machineries.34,55,56 In contrast to prototypical Gram-negative conjugation systems that employ a conjugation-associated pilus to mediate donor-recipient cell contact, Enterococcal pCF10 transfer is sex pheromone-responsive.67,69 Upon detection of specific, small peptide pheromones secreted by potential recipient cells, E. faecalis initiates pCF10 transfer to target cells.69 In contrast, pIP501 can self-transfer to multiple Gram-positive bacteria including Streptococci, Staphylococci, Enterococci, and Listeria as well as Gram-negative E. coli.55,56

Although the T4BSS has an overall similar architecture to the T4ASS, the elaborate T4BSS is comprised of approximately 27 proteins including components that are related to I-type conjugation systems.34 One of the most well-characterized T4BSS, the Legionella pneumophila dot/icm system, consists of a core secretion complex containing DotC, DotD, DotF, DotG and DotH which span both the inner and outer membranes.43,45,70 Similar to the T4ASS, the T4BSS consists of an inner membrane complex and cytoplasmic apparatus formed by DotB, DotL, DotM and DotO, along with a number of chaperone proteins (IcmS, IcmW, and DotK).43,47,71–73 Although protein-sequence level homology between T4ASS and T4BSS components is limited, there is clear structural and functional similarities between system architectures.25,42–45 For example, both systems produce symmetrical core complex structures comprised of functionally analogous proteins (e.g., VirB7/DotC and VirB10/DotG),24,25,42–45 and employ T4CP-like proteins and associated ATPases which are thought to have evolved from SpoIIIE/FtsK-like translocases.46,74 In addition to mediating the delivery of several hundred effector proteins to target cells, the dot/icm system has the capacity to mobilize broad host range IncQ plasmids, and many of the dot/icm genes are closely related to the tra/trb genes of the IncI conjugal plasmids colIb-P9 and R64.34,75 Thus, the architectural and structural similarities among conjugative systems and T4A/T4B effector translocator systems could be exploited to manipulate T4SS machinery as a means of targeting both antibiotic resistance and virulence mechanisms.28,34,42,43,47,50,71

Uptake and release of microbial DNA

Conjugation has been widely recognized as the driving force behind cell contact-dependent spread of antibiotic resistance determinants throughout microbial populations.14,29,40,76,77 In some specialized cases, the acquisition of antibiotic resistance can be achieved through contact-independent DNA uptake and release.34 For example, the gastric bacterium Helicobacter pylori exhibits extraordinary genome plasticity that is attributed to natural transformation via the comB T4SS (Fig. 1B). DNA import is facilitated by a specialized uptake apparatus encoded by two operons, comB2-B4 and comB6-10.78–80 To date, the comB T4SS has been observed in all tested strains of H. pylori. The comB T4SS integrates homologs to the majority of vir T4SS components, lacking only VirB1, VirB5 and VirB11, which are hypothesized to serve specialized roles in contact-dependent DNA conjugation.34,81,82 A two-step model for comB-mediated DNA uptake has been proposed. First, exogenous double-stranded DNA is imported across the outer membrane by the T4SS into the periplasm, followed by delivery of the DNA substrate to the ComEC channel for transport across the inner membrane.34,64,79,81 Interestingly, some comB genes may be required for H. pylori colonization of the gastric mucosa.81

Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a cause of human sexually transmitted genitourinary infections, harbors the horizontally acquired gonococcal genetic island (GGI) that encodes a F plasmid-like T4SS responsible for the secretion of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) into the surrounding environment34,37,38 (Fig. 1B). Exported ssDNA is crucial for Neisseria biofilm development and can be effectively taken up by other gonococci via natural transformation, thereby significantly contributing to genetic diversity.34,83–85 Similar to the F plasmid T4SS, the GGI-encoded T4SS is composed of a mating pair formation complex, pilin subunits, and DNA mobilization elements.37,38,83 However, in contrast to DNA conjugation systems, the GGI system transports ssDNA into the extracellular milieu in a contact-independent manner.37,38

T4SS-dependent Interactions with the host

T4SS mechanisms contribute to the pathogenesis of diseases caused by several mammalian pathogens including Helicobacter pylori, Brucella, Bartonella, Coxiella, Rickettsia, Legionella pneumophila, and phytopathogens such as Agrobacterium tumefaciens.22,23 Here, we will highlight how T4SS activity contributes to (i) gastric pathogenesis induced by H. pylori, and (ii) intracellular survival of L. pneumophila.

Helicobacter pylori

H. pylori is a bacterial pathogen that is the strongest known risk factor for the development of gastric cancer.86 Highly virulent strains elaborate the cag T4SS (Fig. 1D), which is encoded by a strain-specific, 40 kilobase cag pathogenicity island (cag PAI). The cag T4SS is used to translocate the oncogenic bacterial protein CagA,87–89 as well as fragments of peptidoglycan,90 directly into the cytoplasm of gastric epithelial cells. Upon translocation, CagA is rapidly tyrosine phosphorylated by Src and Abl host cell kinases, which allows the oncoprotein to interact with a number of cell signaling pathways.34,91 Interactions between CagA and various host signaling proteins triggers alterations in gastric cell polarity, adhesion, and proliferation, resulting in numerous cellular responses that drive chronic inflammation and gastric carcinogenesis.87,91–94 In concert with CagA injection, peptidoglycan delivery stimulates the cytoplasmic sensor nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 1 (Nod1) leading to the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-8.90 Recent evidence demonstrates that the cag T4SS also mediates translocation of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) biosynthesis metabolite heptose-1,7-bisphosphate to host cells.95,96 Additional consequences of cag T4SS activity include NF-κB activation97,98 and activation of the endosomal pattern recognition receptor TLR9.99 To date, CagA is the only identified protein that is secreted by the H. pylori cag T4SS.89,100

Each strain of H. pylori harbors up to four T4SSs with the putative ability to translocate DNA to target cells, including the cag T4SS; the comB T4SS which is required for DNA uptake during natural transformation and DNA exchange with the extracellular milieu; and two less well-characterized T4SSs, tfs3 and tfs4, which are postulated to function in horizontal DNA transfer between bacteria.81,82,101 Accordingly, the ability of H. pylori to persistently colonize the gastric epithelium has been linked to an extensive DNA exchange occurring between various strains of H. pylori during mixed infections.34,78,81 Recent work suggests that H. pylori secretes chromosomally-derived DNA into gastric cells via cag T4SS activity,99 thus representing only the third example of trans-kingdom DNA transfer.23,36,99,102–104 Similar to the A. tumefaciens vir T4SS, the cag T4SS is comprised of a core complex that is assembled prior to host cell contact, as well as a cell surface-associated pilus that is assembled at the host–pathogen interface.42,44,105,106 Formation of cag T4SS-associated pilus structures requires several cag PAI-encoded genes.105–108 These structures are thought to be an extracellular portion of the cag T4SS, analogous to the F pilus in conjugative T4SSs. CagA appears to be localized to the pilus tip, and H. pylori that fail to assemble pilus structures are unable to translocate CagA, suggesting that cag T4SS pili facilitate effector delivery.34,81,109–111 In contrast to H. pylori, the delivery of A. tumefaciens T-DNA to plant cells does not require biogenesis of the vir T4SS-associated T-pilus.36,112,113

Legionella pneumophila

Multiple intracellular pathogens rely on T4SS activity to create a hospitable replicative niche within target host cells. In order to subvert host defense mechanisms, L. pneumophila, a Gram-negative intracellular bacterium that can infect human alveolar macrophages, employs the dot/icm T4BSS to translocate hundreds of diverse effector proteins into host cells34,75,114 (Fig. 1D). Translocated substrates interfere with the function of colonized immune cells, leading to the development of a severe pneumonia referred to as Legionnaires' disease.75,114 Secreted dot/icm effector proteins target multiple cellular pathways and are pivotal in the conversion of phagosomes into a protected replicative niche referred to as the Legionella-containing vacuole (LCV).34,47,48,71,75 Formation of the LCV also allows for L. pneumophila to secrete additional dot/icm effector proteins to manipulate host cell phosphorylation patterns, interfere with signal transduction pathways, and disrupt membrane trafficking systems.75 For example, interaction between effector proteins and GTPase Rab1 has been observed following fusion of the LCV with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), allowing L. pneumophila to manipulate intracellular vesicle sorting cascades.72,114 Other effector proteins, including LegK1 and LnaB, have been reported to prevent cellular apoptosis by dysregulating NF-κB activation, thereby promoting persistent infection34,47,72,115 Collectively, L. pneumophila employs dot/icm T4SS activity to generate a specialized intracellular compartment that escapes endocytic maturation processes and enables stealth bacterial multiplication.34,75

Development of T4SS inhibitors

Recent advances have provided critical architectural and structural information for several T4SS nanomachines.25,42,43,58,74 Coupled to our deepening knowledge of mechanisms underlying the movement of T4SS cargo to recipient cells, we are positioned to develop effective therapeutics that disarm T4SS activity. Multiple studies have pursued potential conjugation inhibitors that preclude the spread of antibiotic resistance determinants14,28,29 (Table 1). Recent work focused on the isolation of plant-derived bioactive compounds identified two compounds, rottlerin [5,7-dihydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-6-(2,4,6-trihydroxy-3-methyl-5-acetylbenzyl)-8-cinnamoyl-1,2-chromene] and the red compound (8-cinnamoyl-5,7-dihydroxy-2,2,6-trimethylchromene), that inhibited conjugal transfer of several plasmids without perturbing Gram-negative bacterial growth.116 Although the inhibitor mechanism(s) of action have not been elucidated, the planar structure of the compounds suggests a potential interaction with DNA replication machinery.116

Table 1. Representative T4SS inhibitors and their characteristics.

| T4SS inhibitor structure | Inhibitor group (compound name) | Screening assay | Mechanism of action | Organism range | Ref. |

|

Plant-derived bioactive compound (rottlerin) | Bioassay-guided fractionation of medicinal plant extracts | Unknown | Gram-positive bacteria including MRSA; E. coli pKM101, TP114, pUB307 and R6K conjugative systems | 116 |

|

Plant-derived bioactive compound (red compound) | Bioassay-guided fractionation of medicinal plant extracts | Unknown | Gram-positive bacteria including MRSA; Escherichia coli pKM101, TP114, pUB307 and R6K conjugative systems | 116 |

|

Salicylidene acylhydrazide derivatives (B81-2) | Target-based HTS in a whole cell assay | Prevents VirB8 dimerization; inhibits TraE | Brucella abortus; Escherichia coli pKM101 system | 33, 117 and 118 |

|

Heterocyclic 2-pyridones (KSK85) | Targeted, phenotypic cell-based screen of heterocyclic 2-pyridones | Disrupts T4SS apparatus biogenesis (unknown mechanism) | Helicobacter pylori, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Escherichia coli pKM101 and R1-16 conjugative systems | 28 |

|

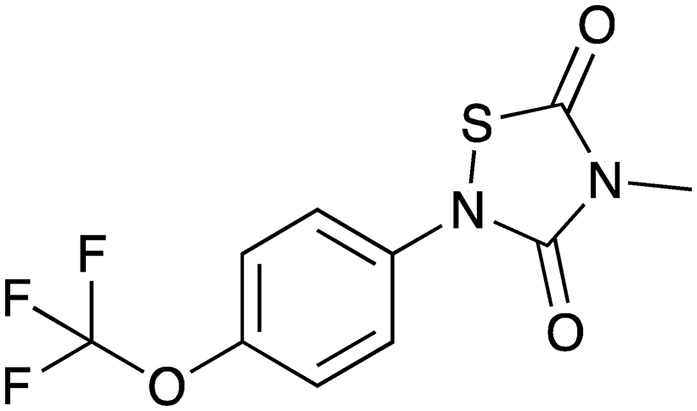

Thiadiazolidine-3,5-diones (CHIR-1) | HTS using in vitro ATPase activity; cell-based assays | Inhibits VirB11 ATPase activity | Helicobacter pylori VirB11 homolog (HP0525) | 120 |

|

8-Amino imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazine derivatives (compound 11) | Virtual HTS; docking studies; in vitro ATPase assays | Inhibits VirB11 ATPase activity | Helicobacter pylori VirB11 homolog (HP0525) | 121 |

|

Unsaturated fatty acids (2-hexadecynoic acid) | Luminescence-based high-throughput conjugation (HTC) assays | Inhibits TrwD ATPase activity | Escherichia, Salmonella, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter spp.; IncF, IncW, IncH, IncI, IncL/M, IncX conjugative plasmids | 30, 31, 122 and 123 |

|

Heterocyclic 2-pyridones (C10) | Targeted, phenotypic cell-based screen of heterocyclic 2-pyridones | Unknown | Helicobacter pylori, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Escherichia coli pKM101 and R1-16 conjugative systems | 28 |

|

Fungal polyketides (tanzawaic acid A) | Target-based HTS in a whole cell assay | Unknown | Escherichia coli IncW, IncFI, IncFII, IncI, IncL/M, IncX, IncH conjugative plasmids | 128 |

|

Tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor (RWJ-60475) | Live cell reporter assay (fusion protein-based) | Inhibits host cell receptor tyrosine kinase CD45 | Legionella pneumophila | 135 |

|

Oxidative phosphorylation inhibitor (CCCP) | Live cell reporter assay (fusion protein-based) | Disrupts the proton motive force (PMF) | Legionella pneumophila | 136 |

Several studies have taken high-throughput screening approaches to target conserved components of T4SS machinery. One potential molecular target of various small molecule inhibitors, VirB8, is an essential T4SS component required for apparatus assembly.32,33,117 A high-throughput screening strategy focused on Brucella VirB8 identified salicylidene acylhydrazide derivatives that inhibited protein dimerization.33,117 Subsequent studies determined that the identified acylhydrazide compounds could also bind the VirB8 homolog TraE from the pKM101 system to disrupt protein–protein interactions and inhibit conjugation.118 However, although some of the small molecules exhibited low KD values in in vitro VirB8 binding assays, the compounds were unable to prevent conjugal transfer of the unrelated RP4 system, suggesting that acylhydrazide derivatives lack broad-spectrum activity against diverse T4SSs.118 Alternative approaches have been employed to develop inhibitors targeting the VirB8 homolog TraM within Gram-positive conjugation machinery.119 Antibodies directed against TraM produced from the conjugative plasmid pIP501 mediated in vitro opsonophagocytic killing of clinical E. faecalis and S. aureus strains harboring a T4SS.119 Additionally, rodent immunization with TraM or administration of anti-TraM antisera conferred protection against E. faecalis and S. aureus bacteremia.119

Recent investigations employed phenotypic screening approaches to identify synthetic chemical scaffolds that prevent assembly and function of phylogenetically diverse T4SS machineries. One study aimed at developing chemical probes to study T4SS apparatus biogenesis identified heterocyclic 2-pyridones that impacted the assembly and function of multiple systems.28 Two of the identified heterocyclic small molecules (referred to as C10 and KSK85) blocked H. pylori cag T4SS activity, disrupted inter-bacterial DNA transfer by plasmids pKM101 (IncN) and R1-16 (IncF) in E. coli, and attenuated the vir T4SS-mediated delivery of A. tumefaciens T-DNA in a plant model of infection.28 Whereas C10 inhibited T4SS activity without perturbing apparatus assembly, KSK85 disrupted cag T4SS pilus biogenesis.28 The ability of KSK85 to target assembly of additional pilus systems unrelated to the cag T4SS has not yet been evaluated. In addition, the moderate potency of identified heterocyclic 2-pyridone inhibitors indicates that scaffold optimization will be important for the future development of compounds that effectively prevent conjugation in the clinical setting. Nevertheless, targeting T4SS apparatus biogenesis and conjugative pilus assembly is a promising strategy to avert the spread of antibiotic resistance determinants.

Novel whole-cell, luminescence-based screening approaches have led to the development of specific unsaturated fatty acids that prevented conjugation of IncF and IncW group plasmids.30 This innovative screening method was used in concert with a library comprised of more than 12 000 diverse natural compounds to identify dehydrocrepnynic acid (DHCA) as a potent conjugation inhibitor. By exploiting DHCA as a chemical template, synthetic compounds that target specific conjugation systems were developed. Interestingly, this method was used to develop synthetic 2-hexadecynoic acid (2-HDA) and other 2-alkynoic fatty acids (2-AFAs) that robustly blocked conjugation by a range of conjugative T4SSs in various bacteria, including IncF, IncW, and IncH group plasmids that are widely harbored by Enterobacteriaceae.31 In addition, synthetic 2-AFAs exerted moderate inhibitory effects against IncI, IncL/M, and IncX group conjugation systems.31 Strikingly, because plasmid maintenance exerts a high energetic and fitness cost on host bacterial cells, 2-HDA could selectively eliminate de-repressed IncF conjugal transfer systems from bacterial populations without perturbing dissemination of IncN and IncP group plasmids.29–31

T4SS activity is driven by several ATPases that power apparatus assembly, DNA unwinding, and cargo translocation.21,27,34 Multiple groups have reported the development of small molecule inhibitors that target the VirB11 homolog HP0525 associated with the H. pylori cag T4SS.120,121 Traditional high throughput screening assays120 and virtual molecular docking studies121 identified thiadiazolidine-3,5-diones and 8-amino imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazine derivatives as potent inhibitors of purified HP0525 ATPase activity. Other studies aimed at developing specific chemical scaffolds that target TrwD, the VirB11 homolog in plasmid R388, revealed that unsaturated fatty acids (oleic and linoleic acid), 2-HDA, 2-octadecynoic acid (2-ODA), and 2,6-hexadecadiynoic acid (2,6-HDA) inhibited ATPase activity in vitro.122 Additionally, a recent study identified the palmitate analog 2-bromopalmitic acid as a compound that effectively reduces TrwD ATPase activity and bacterial conjugation.123 TrwD/VirB11 contributes to both conjugative pilus assembly and DNA export, and is hypothesized to serve as a molecular switch that dynamically controls substrate transport and apparatus biogenesis.27,124 Thus, this traffic ATPase represents an attractive target for the development of potent compounds that disrupt T4SS-mediated dissemination of antibiotic resistance determinants and injection of microbial cargo into host cells.

Although lipid-based inhibitors can selectively block DNA conjugation, fatty acid scaffolds exhibit multiple in vivo liabilities that must be overcome. For example, triple-bonded fatty acids (e.g., 2-HDA and 2-ODA) exhibit host cell toxicity,125,126 and unsaturated fatty acids (e.g., oleic and linoleic acid) contain double bonds that are susceptible to oxidation.127 Additional groups of bioactive compounds that target IncW- and IncFII-encoded T4SSs, including the fungal polyketides tanzawaic acids A and B (TZA-A and TZA-B, respectively), were subsequently identified as promising conjugation inhibitors.128 In comparison to synthetic unsaturated fatty acid-based inhibitors, TZAs exhibited lower toxicity in eukaryotic cell culture.128

Biological mechanisms to disarm bacterial conjugation

In addition to the identification of chemical scaffolds that prevent various bacterial conjugation processes, ancient biological systems are being explored as potential conjugation inhibitors. For example, conjugative pili serve as receptors for ‘male-specific’ bacteriophages that bind the pilus to gain access to the bacterial cell cytoplasm for phage replication.129,130 The g3p phage coat protein of the filamentous bacteriophage M13 exhibits a high affinity for F-type pilus systems.29,131 Exogenous addition of the g3p N-terminal domain to bacteria harboring F-plasmid systems led to a significant decrease in conjugation frequency in liquid culture.131 Filamentous phage can also impact the formation of bacterial biofilms by interfering with mating pair formation, offering additional promise for the development of phage-based therapies that could augment the efficacy of existing antibiotics.132 Likewise, recent work has explored the potential of re-purposing bacteriophage to transmit Crispr-Cas9 as a means to disarm bacterial populations harboring antibiotic resistance plasmids.133 Finally, eukaryotic immunity proteins have been explored as an approach to prevent conjugation. In E. coli, expression of stable, intracellular single-chain Fv antibodies (termed intrabodies) directed towards the relaxase TrwB protected transgenic recipient cells from transfer of conjugative plasmid R388.29,134 However, the clinical application of intrabody-mediated immunity to conjugation is limited due to the inherent specificity of individual intrabodies and the requirement of a transgenic recipient cell population.29

Conclusions and outlook

The mounting spread of antibiotic resistance is an accelerating and significant challenge to our global healthcare system. Recent strategies to combat antibiotic resistant microbes have focused on preventing the spread of resistance determinants through the discovery of novel anti-conjugation compounds. T4SS-mediated conjugation is the predominant mechanism driving the rapid dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes; thus, the T4SS is an ideal target for developing therapeutics that counter antibiotic resistance. Innovation driving the future development of therapeutic lead compounds that target specific T4SSs will undoubtedly require a multidisciplinary approach that integrates concepts from chemical biology, bacteriology, structural biology, pharmacology, and synthetic chemistry. As new therapeutic countermeasures must be designed to disarm antibiotic resistant pathogens, the discovery of molecular scaffolds that inhibit T4SS function will offer a path to precision antimicrobials that extend the usefulness of current antibiotic agents and prevent further spread of resistance determinants.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We thank all investigators working in the field of T4SS biology and the development of T4SS inhibitors. We apologize if their work is not cited due to the scope of the review presenting the most recent advances in T4SS inhibitor development. We thank Jamie K. Norris for assistance with figure design and production. Our work on T4SS mechanisms and bacterial antibiotic resistance is supported by startup funds from the University of Kentucky College of Food, Agriculture, and Environment (to CLS) and pilot awards from the University of Kentucky Center for Molecular Medicine (NIH P30 GM110787 to CLS).

Biographies

Elizabeth Boudaher

Carrie L. Shaffer

References

- Chang Q., Wang W., Regev-Yochay G., Lipsitch M., Hanage W. P. Evol. Appl. 2015;8:240–247. doi: 10.1111/eva.12185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giske C. G., Monnet D. L., Cars O., Carmeli Y., R. ReAct-Action on Antibiotic Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:813–821. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01169-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher H. W., Talbot G. H., Bradley J. S., Edwards J. E., Gilbert D., Rice L. B., Scheld M., Spellberg B., Bartlett J. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;48:1–12. doi: 10.1086/595011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kraker M. E., Davey P. G., Grundmann H., BURDEN study group PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kraker M. E., Stewardson A. J., Harbarth S. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infectious Diseases Society of America Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010;50:1081–1083. doi: 10.1086/652237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hede K. Nature. 2014;509:S2–S3. doi: 10.1038/509S2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould I. M., Bal A. M. Virulence. 2013;4:185–191. doi: 10.4161/viru.22507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gunzburg J., Ghozlane A., Ducher A., Le Chatelier E., Duval X., Ruppe E., Armand-Lefevre L., Sablier-Gallis F., Burdet C., Alavoine L., Chachaty E., Augustin V., Varastet M., Levenez F., Kennedy S., Pons N., Mentre F., Andremont A. J. Infect. Dis. 2018;217:628–636. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francino M. P. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1543. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira T., David P. H. C., Pothier J. Drug Dev. Res. 2018;80:86–97. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond F., Ouameur A. A., Deraspe M., Iqbal N., Gingras H., Dridi B., Leprohon P., Plante P. L., Giroux R., Berube E., Frenette J., Boudreau D. K., Simard J. L., Chabot I., Domingo M. C., Trottier S., Boissinot M., Huletsky A., Roy P. H., Ouellette M., Bergeron M. G., Corbeil J. ISME J. 2016;10:707–720. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance 2014, 2014.

- Graf F. E., Palm M., Warringer J., Farewell A. Drug Dev. Res. 2018;80:19–23. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez A., Gil E., Cartelle M., Perez A., Beceiro A., Mallo S., Tomas M. M., Perez-Llarena F. J., Villanueva R., Bou G. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007;59:841–847. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrea M. M., Arena F., Pallecchi L., Rossolini G. M. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2013;303:305–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitout J. D. Drugs. 2010;70:313–333. doi: 10.2165/11533040-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitout J. D., Laupland K. B. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2008;8:159–166. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santajit S., Indrawattana N. BioMed Res. Int. 2016;2016:2475067. doi: 10.1155/2016/2475067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2227–2238. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01707-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallden K., Rivera-Calzada A., Waksman G. Cell. Microbiol. 2010;12:1203–1212. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Martinez C. E., Christie P. J. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2009;73:775–808. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00023-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascales E., Christie P. J. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2003;1:137–149. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fronzes R., Schafer E., Wang L., Saibil H. R., Orlova E. V., Waksman G. Science. 2009;323:266–268. doi: 10.1126/science.1166101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low H. H., Gubellini F., Rivera-Calzada A., Braun N., Connery S., Dujeancourt A., Lu F., Redzej A., Fronzes R., Orlova E. V., Waksman G. Nature. 2014;508:550–553. doi: 10.1038/nature13081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waksman G., Fronzes R. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010;35:691–698. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waksman G. EMBO Rep. 2019;20:e47012. doi: 10.15252/embr.201847012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer C. L., Good J. A., Kumar S., Krishnan K. S., Gaddy J. A., Loh J. T., Chappell J., Almqvist F., Cover T. L., Hadjifrangiskou M. mBio. 2016;7:e00221-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00221-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabezon E., de la Cruz F., Arechaga I. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2329. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lopez R., Machón C., Longshaw C. M., Martin S., Molin S., Zechner E. L., Espinosa M., Lanka E., de la Cruz F. Microbiology. 2005;151:3517–3526. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getino M., Sanabria-Ríos D. J., Fernández-López R., Campos-Gómez J., Sánchez-López J. M., Fernández A., Carballeira N. M., de la Cruz F. mBio. 2015;6:e01032-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01032-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron C. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2006;84:890–899. doi: 10.1139/o06-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschos A., den Hartigh A., Smith M. A., Atluri V. L., Sivanesan D., Tsolis R. M., Baron C. Infect. Immun. 2011;79:1033–1043. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00993-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grohmann E., Christie P. J., Waksman G., Backert S. Mol. Microbiol. 2018;107:455–471. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie P. J., Atmakuri K., Krishnamoorthy V., Jakubowski S., Cascales E. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;59:451–485. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascales E., Christie P. J. Science. 2004;304:1170–1173. doi: 10.1126/science.1095211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan M. M., Heilers J. H., van der Does C., Dillard J. P. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2017;413:323–345. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-75241-9_13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton H. L., Dominguez N. M., Schwartz K. J., Hackett K. T., Dillard J. P. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;55:1704–1721. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Calzada A., Fronzes R., Savva C. G., Chandran V., Lian P. W., Laeremans T., Pardon E., Steyaert J., Remaut H., Waksman G., Orlova E. V. EMBO J. 2013;32:1195–1204. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fronzes R., Christie P. J., Waksman G. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:703–714. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo H. J., Waksman G. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:1919–1926. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.7.1919-1926.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y. W., Shaffer C. L., Rettberg L. A., Ghosal D., Jensen G. J. Cell Rep. 2018;23:673–681. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosal D., Chang Y. W., Jeong K. C., Vogel J. P., Jensen G. J. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:726–732. doi: 10.15252/embr.201643598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick-Cheng A. E., Pyburn T. M., Voss B. J., McDonald W. H., Ohi M. D., Cover T. L. mBio. 2016;7:e02001–e02015. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02001-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubori T., Koike M., Bui X. T., Higaki S., Aizawa S., Nagai H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:11804–11809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404506111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak M. J., Kim J. D., Kim H., Kim C., Bowman J. W., Kim S., Joo K., Lee J., Jin K. S., Kim Y. G., Lee N. K., Jung J. U., Oh B. H. Nat. Microbiol. 2017;2:17114. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voth D. E., Broederdorf L. J., Graham J. G. Future Microbiol. 2012;7:241–257. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin T., Zhou H., Ren H., Liu W. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:388. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Rong C., Chen C., Gao G. F. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhas M., Crook D. W., Hood D. W. Cell. Microbiol. 2008;10:2377–2386. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabezon E., Ripoll-Rozada J., Pena A., de la Cruz F., Arechaga I. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2015;39:81–95. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz F., Frost L. S., Meyer R. J., Zechner E. L. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2010;34:18–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smillie C., Garcillan-Barcia M. P., Francia M. V., Rocha E. P., de la Cruz F. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010;74:434–452. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00020-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcillan-Barcia M. P., Francia M. V., de la Cruz F. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009;33:657–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goessweiner-Mohr N., Arends K., Keller W., Grohmann E. Microbiol. Spectrum. 2014;2:PLA-S0004-2013. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0004-2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grohmann E., Muth G., Espinosa M. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003;67:277–301. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.2.277-301.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran Darbari V., Waksman G. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015;84:603–629. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062911-102821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa T. R. D., Ilangovan A., Ukleja M., Redzej A., Santini J. M., Smith T. K., Egelman E. H., Waksman G. Cell. 2016;166:1436–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo H. J., Yuan Q., Beck M. R., Baron C., Waksman G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:15947–15952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2535211100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Q., Carle A., Gao C., Sivanesan D., Aly K. A., Hoppner C., Krall L., Domke N., Baron C. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:26349–26359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke M., Maddera L., Harris R. L., Silverman P. M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:17978–17981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806786105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babic A., Lindner A. B., Vulic M., Stewart E. J., Radman M. Science. 2008;319:1533–1536. doi: 10.1126/science.1153498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatty M., Laverde Gomez J. A., Christie P. J. Res. Microbiol. 2013;164:620–639. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llosa M., Gomis-Rüth F. X., Coll M., de la Cruz F. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;45:1–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tato I., Zunzunegui S., de la Cruz F., Cabezon E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:8156–8161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503402102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantl S., Behnke D., Alonso J. C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4783–4790. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.16.4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowicz B. K., Shi K., Gu Z. Y., Ohlendorf D. H., Earhart C. A., Dunny G. M. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;62:958–969. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francia M. V., Varsaki A., Garcillan-Barcia M. P., Latorre A., Drainas C., de la Cruz F. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2004;28:79–100. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Zhang X., Manias D., Yeo H. J., Dunny G. M., Christie P. J. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:3632–3645. doi: 10.1128/JB.01999-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong K. C., Ghosal D., Chang Y. W., Jensen G. J., Vogel J. P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017;114:8077–8082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1621438114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano N., Kubori T., Kinoshita M., Imada K., Nagai H. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001129. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubori T., Nagai H. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2016;29:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amyot W. M., deJesus D., Isberg R. R. Infect. Immun. 2013;81:3239–3252. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00552-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redzej A., Ukleja M., Connery S., Trokter M., Felisberto-Rodrigues C., Cryar A., Thalassinos K., Hayward R. D., Orlova E. V., Waksman G. EMBO J. 2017;36:3080–3095. doi: 10.15252/embj.201796629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai H., Kubori T. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:136. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmini J., de la Cruz F., Rocha E. P. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:315–331. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmini J., Neron B., Abby S. S., Garcillan-Barcia M. P., de la Cruz F., Rocha E. P. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:5715–5727. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stingl K., Muller S., Scheidgen-Kleyboldt G., Clausen M., Maier B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:1184–1189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909955107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnholz A., Hoefler C., Odenbreit S., Fischer W., Hofreuter D., Haas R. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:882–893. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.3.882-893.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger N. J., Knuver M. T., Zawilak-Pawlik A., Appel B., Stingl K. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005626. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Gonzalez E., Backert S. J. Gastroenterol. 2014;49:594–604. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-0938-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer S., Holsten L., Weiss E., Benghezal M., Fischer W., Haas R. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45623. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler P. L., Chan Y. A., Hackett K. T., Turner N., Hamilton H. L., Cloud-Hansen K. A., Dillard J. P. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:1666–1679. doi: 10.1128/JB.02098-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawley T. D., Klimke W. A., Gubbins M. J., Frost L. S. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003;224:1–15. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey M. E., Bender T., Klimowicz A. K., Hackett K. T., Yamamoto A., Jolicoeur A., Callaghan M. M., Wassarman K. M., van der Does C., Dillard J. P. Mol. Microbiol. 2015;97:1168–1185. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amieva M., Peek, Jr. R. M. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:64–78. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odenbreit S., Puls J., Sedlmaier B., Gerland E., Fischer W., Haas R. Science. 2000;287:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourzac K. M., Guillemin K. Cell. Microbiol. 2005;7:911–919. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer W. Rev. Geophys. 2011;278:1203–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Viala J., Chaput C., Boneca I. G., Cardona A., Girardin S. E., Moran A. P., Athman R., Memet S., Huerre M. R., Coyle A. J., DiStefano P. S., Sansonetti P. J., Labigne A., Bertin J., Philpott D. J., Ferrero R. L. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:1166–1174. doi: 10.1038/ni1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller D., Tegtmeyer N., Brandt S., Yamaoka Y., De Poire E., Sgouras D., Wessler S., Torres J., Smolka A., Backert S. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:1553–1566. doi: 10.1172/JCI61143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selbach M., Moese S., Hauck C. R., Meyer T. F., Backert S. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:6775–6778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100754200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegtmeyer N., Wessler S., Backert S. Rev. Geophys. 2011;278:1190–1202. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahi M., Azuma T., Ito S., Ito Y., Suto H., Nagai Y., Tsubokawa M., Tohyama Y., Maeda S., Omata M., Suzuki T., Sasakawa C. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:593–602. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.4.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gall A., Gaudet R. G., Gray-Owen S. D., Salama N. R. mBio. 2017;8:e01168-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01168-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann S., Pfannkuch L., Al-Zeer M. A., Bartfeld S., Koch M., Liu J., Rechner C., Soerensen M., Sokolova O., Zamyatina A., Kosma P., Maurer A. P., Glowinski F., Pleissner K. P., Schmid M., Brinkmann V., Karlas A., Naumann M., Rother M., Machuy N., Meyer T. F. Cell Rep. 2017;20:2384–2395. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt S., Kwok T., Hartig R., Konig W., Backert S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:9300–9305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409873102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb A., Yang X. D., Tsang Y. H., Li J. D., Higashi H., Hatakeyama M., Peek R. M., Blanke S. R., Chen L. F. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:1242–1249. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga M. G., Shaffer C. L., Sierra J. C., Suarez G., Piazuelo M. B., Whitaker M. E., Romero-Gallo J., Krishna U. S., Delgado A., Gomez M. A., Good J. A., Almqvist F., Skaar E. P., Correa P., Wilson K. T., Hadjifrangiskou M., Peek R. M. Oncogene. 2016;35:6262–6269. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backert S., Tegtmeyer N., Fischer W. Future Microbiol. 2015;10:955–965. doi: 10.2217/fmb.15.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer W., Windhager L., Rohrer S., Zeiller M., Karnholz A., Hoffmann R., Zimmer R., Haas R. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:6089–6101. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atmakuri K., Ding Z., Christie P. J. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;49:1699–1713. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelvin S. B. Front. Plant Sci. 2012;3:52. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder G., Schuelein R., Quebatte M., Dehio C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:14643–14648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019074108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer C. L., Gaddy J. A., Loh J. T., Johnson E. M., Hill S., Hennig E. E., McClain M. S., McDonald W. H., Cover T. L. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002237. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E. M., Gaddy J. A., Voss B. J., Hennig E. E., Cover T. L. Infect. Immun. 2014;82:3457–3470. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01640-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrozo R. M., Cooke C. L., Hansen L. M., Lam A. M., Gaddy J. A., Johnson E. M., Cariaga T. A., Suarez G., Peek, Jr. R. M., Cover T. L., Solnick J. V. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003189. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde M., Puls J., Buhrdorf R., Fischer W., Haas R. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;49:219–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick-Cheng A. E., Pyburn T. M., Voss B. J., McDonald W. H., Ohi M. D., Cover T. L. mBio. 2016;7:e02001–e02015. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02001-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backert S., Tegtmeyer N. Toxins. 2017;9:E115. doi: 10.3390/toxins9040115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegtmeyer N., Wessler S., Necchi V., Rohde M., Harrer A., Rau T. T., Asche C. I., Boehm M., Loessner H., Figueiredo C., Naumann M., Palmisano R., Solcia E., Ricci V., Backert S., Cell Host Microbe, 2017, 22 , 552 –560 , , e555 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski S. J., Kerr J. E., Garza I., Krishnamoorthy V., Bayliss R., Waksman G., Christie P. J. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;71:779–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garza I., Christie P. J. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:3022–3034. doi: 10.1128/JB.00287-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Valero L., Rusniok C., Carson D., Mondino S., Pérez-Cobas A. E., Rolando M., Pasricha S., Reuter S., Demirtas J., Crumbach J., Descorps-Declere S., Hartland E. L., Jarraud S., Dougan G., Schroeder G. N., Frankel G., Buchrieser C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019;116:2265–2273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1808016116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchrieser C. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:182. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyedemi B. O., Shinde V., Shinde K., Kakalou D., Stapleton P. D., Gibbons S. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2016;5:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. A., Coincon M., Paschos A., Jolicoeur B., Lavallee P., Sygusch J., Baron C. Chem. Biol. 2012;19:1041–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casu B., Smart J., Hancock M. A., Smith M., Sygusch J., Baron C. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:23817–23829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.753327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laverde D., Probst I., Romero-Saavedra F., Kropec A., Wobser D., Keller W., Grohmann E., Huebner J. J. Infect. Dis. 2017;215:1836–1845. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilleringmann M., Pansegrau W., Doyle M., Kaufman S., MacKichan M. L., Gianfaldoni C., Ruggiero P., Covacci A. Microbiology. 2006;152:2919–2930. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28984-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer J. R., Walldén K., Pesnot T., Campbell F., Gane P. J., Simone M., Koss H., Buelens F., Boyle T. P., Selwood D. L., Waksman G., Tabor A. B. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014;22:6459–6470. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripoll-Rozada J., Garcia-Cazorla Y., Getino M., Machon C., Sanabria-Rios D., de la Cruz F., Cabezon E., Arechaga I. Mol. Microbiol. 2016;100:912–921. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Cazorla Y., Getino M., Sanabria-Rios D. J., Carballeira N. M., de la Cruz F., Arechaga I., Cabezon E. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:16923–16930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atmakuri K., Cascales E., Christie P. J. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;54:1199–1211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04345.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konthikamee W., Gilbertson J. R., Langkamp H., Gershon H. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1982;22:805–809. doi: 10.1128/aac.22.5.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon H., Shanks L. Can. J. Microbiol. 1978;24:593–597. doi: 10.1139/m78-096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niki E., Yoshida Y., Saito Y., Noguchi N. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;338:668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getino M., Fernandez-Lopez R., Palencia-Gandara C., Campos-Gomez J., Sanchez-Lopez J. M., Martinez M., Fernandez A., de la Cruz F. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X., Li Z., Lai M., Shu S., Du Y., Zhou Z. H., Sun R. Nature. 2017;541:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature20589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchak J., Anthony K. G., Frost L. S. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;43:195–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A., Jimenez J., Derr J., Vera P., Manapat M. L., Esvelt K. M., Villanueva L., Liu D. R., Chen I. A. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19991. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May T., Tsuruta K., Okabe S. ISME J. 2011;5:771–775. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikard D., Euler C. W., Jiang W., Nussenzweig P. M., Goldberg G. W., Duportet X., Fischetti V. A., Marraffini L. A. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:1146–1150. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcillan-Barcia M. P., Jurado P., Gonzalez-Perez B., Moncalian G., Fernandez L. A., de la Cruz F. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;63:404–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier X., Gabay J. E., Reyes M., Zhu J. W., Weiss A., Shuman H. A. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000501. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ablasser A., Goldeck M., Cavlar T., Deimling T., Witte G., Rohl I., Hopfner K. P., Ludwig J., Hornung V. Nature. 2013;498:380–384. doi: 10.1038/nature12306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]