Abstract

Context •

Behavioral lifestyle interventions to lower body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) are the standard approach for preventing adolescent-onset type 2 diabetes (T2D). Unfortunately, existing programs have had limited long-term success of lessening insulin resistance, the key physiological risk indicator for T2D. Underlying psychosocial factors, particularly depressive symptoms, have been related to insulin resistance, independent of BMI or body fat. Preliminary evidence indicates that mindfulness-based programs show promise for intervening with depression and T2D; yet, this approach is novel and data in adolescents are scarce.

Objective •

The objectives of this study were (1) to evaluate the benefits, and potential underlying mechanisms, of a mindfulness-based intervention in adolescents at-risk for T2D with depressive symptoms and (2) to consider clinical implementation with this specific, psychologically, and medically at-risk adolescent population.

Design and Setting •

The research team conducted a case study report. The setting was an outpatient therapy clinic and research laboratory at a university.

Participant •

The participant was a 16-y-old female with elevated depressive symptoms, obesity, and insulin resistance, and a family history of T2D.

Intervention and Outcomes •

The intervention was a 6-wk mindfulness-based group program. The key outcomes were patterns of change in trait mindfulness, depression, and insulin resistance in the course of a 1-y follow-up. Secondary outcomes were patterns of change in reported-overeating patterns and cortisol awakening response.

Results •

Compared with her scores at baseline, the participant displayed a pattern of increased trait mindfulness, decreased depressive symptoms, and lessening of insulin resistance immediately following the group program and at 1 y. BMI and body fat were stable. There was a remission in reported-overeating and a pattern of declining cortisol awakening response 1 y later. Participant feedback on the intervention was generally positive but also provided potential modifications to strengthen acceptability and effectiveness.

Conclusions •

The current case results suggest that teaching mindfulness skills to adolescent girls at risk for T2D with depressive symptoms may offer distinctive advantages for treating depression and T2D risk. Clinical implications for increasing the success of implementing mindfulness-based programs in this population include a focus on promotion of social connectedness within the group, implementation of strategies to increase adherence to home practice activities, and the use of facilitation techniques to promote concrete understanding of abstract mindfulness concepts. Future, adequately powered clinical trial data are required to test therapeutic mechanisms and recommended adaptations.

The prevalence of adolescent-onset type 2 diabetes (T2D) has grown significantly in recent decades,1 a trend largely explained by the epidemic rise in pediatric obesity.2 The manifestation of T2D in younger people is particularly concerning because adolescent-onset of the disease appears to be associated with an aggressive disease course and earlier mortality.3 Prevention efforts for T2D traditionally have focused on behavioral interventions to alter diet and physical activity to lower body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) and ameliorate insulin resistance.4 Insulin resistance refers to decreased sensitivity of the hormone insulin to regulate blood sugar and it is the key physiological precursor to T2D.5 Unfortunately, sustained weight loss remains a major challenge for adolescents, calling for alternative, more targeted approaches to T2D prevention.4,6

Emerging data support the notion that depressive symptoms are a prospective risk factor for worsening insulin resistance and T2D.7 Adolescence is a particularly salient time for increasing stress and depressive symptoms, particularly for youth with overweight and obesity.8 More marked stress and depressive symptoms in heavier adolescents have been attributed to psychosocial stressors such as increased peer victimization and social exclusion related to weight.9 There is a positive cross-sectional association between depressive symptoms and insulin resistance,10,11 even after adjusting for body composition. Further, adolescent depressive symptoms predict worsening insulin resistance and the onset of T2D through time, even after accounting for BMI or body fat.12,13 Although the mechanisms remain unclear, possible explanatory pathways include stress-related behaviors such as overeating behaviors and stress-related physiology such as hypercortisolism.14,15 Thus, intervening with depressive symptoms as an antecedent to insulin resistance via reducing stress may offer a novel, targeted approach to the prevention of adolescent-onset T2D that has not been addressed by behavioral interventions.

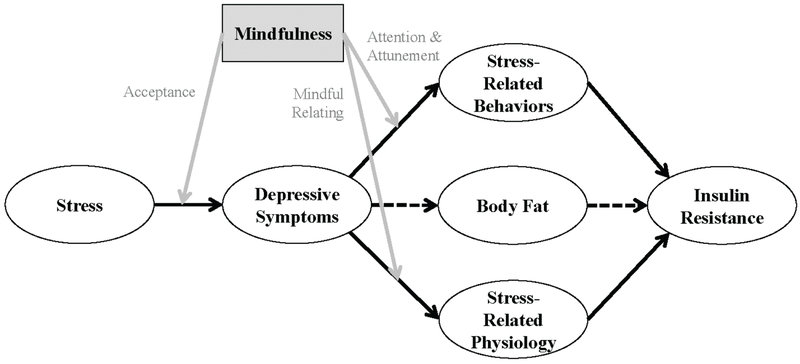

Increasingly, mindfulness-based interventions have attracted interest for their application to T2D prevention and management.16 Mindfulness often is defined as paying attention on purpose to the present moment without judgement.17 Mindfulness-based interventions involve training attention and cultivating nonjudgmental yet discerning awareness of internal and external experience, including developing acceptance of unpleasant, and possibly even distressing, events and sensations.18 By virtue of such changes in one’s orientation to experience, mindfulness training is proposed to decrease stress-related overeating behavior and modify physiological stress response.19 Through increased attention to internal experience and greater acceptance of unpleasant experiences, mindfulness has been theoretically proposed to affect the relationship between stress, depression, and T2D in several ways: (1) lessening the connection between stressful events and depressive symptoms; (2) decreasing stress-related behaviors, such as overeating in response to stress; and (3) lessening the physiological response to stress (Figure 1).19 Correlational research has linked trait mindfulness with these theoretically proposed mechanisms including inverse associations of mindfulness with eating in response to psychological distress, uncontrolled eating, a preference for sweets and fats, binge eating, and buffering physiological stress responses, including cortisol awakening response.20–23 Consistent with this theoretical framework, mindfulness-based interventions have produced greater decreases in depressive symptoms than treatment-as-usual or waitlist conditions in adults with diabetes, albeit with more mixed outcomes for glycemic control.24–27

Figure 1.

Proposed Theoretical Model of the Chain of Psychological and Physiological Antecedents to Increased Insulin Resistance and the Role of Mindfulness in Prevention

In adolescents, mindfulness-based interventions have been evaluated primarily in nontreatment seeking community samples or adolescents at risk for, or with, mental and behavioral health problems.18 A small body of randomized controlled clinical trial studies of mindfulness-based programs have shown efficacy in decreasing depressive and anxiety symptoms in both community samples and adolescents with mixed-psychiatric diagnoses.28–31 Even fewer studies have explored the effects of mindfulness on physical health outcomes in adolescents. However, in a series of trials, a breath awareness training program conducted with adolescents at risk for hypertension was shown to lower blood pressure as compared with an active control comparison condition.32

This current case report describes the experiences of an adolescent girl who participated in a mindfulness-based group intervention, as part of a small, randomized controlled pilot study.33 The pilot study was conducted to determine overall feasibility and acceptability of a mindfulness group intervention in adolescent girls with elevated depressive symptoms, overweight/obesity, and a familial risk of T2D.33 In this parent study, we found that a mindfulness-based group intervention was, overall, both feasible and acceptable for this population and showed similar reductions in depressive symptoms and larger decreases in insulin resistance at posttreatment, on average, as compared with a cognitive behavioral therapy control group program.33 Given the novelty of this approach, we used a case report format to (1) highlight outcomes in the context of theoretical mechanisms that explain the particular fit of mindfulness for targeted prevention of adolescent depression and T2D and (2) discuss the clinical factors for success and barriers to implementation of the program in this psychologically and medically at-risk population.

METHOD

Study Overview

The case study reported in the current project was drawn from a sample of adolescent volunteers taking part in a pilot randomized controlled clinical trial.33 One-year outcomes for this trial have not been previously reported. In addition, this case report represents the first examination of overeating behavior and stress physiology in this sample. Inclusion criteria for the study were (1) female; (2) age 12 to 17 years; (3) overweight or obesity (BMI at the 85th percentile or above for age and sex); (4) parent-reported history of T2D, prediabetes, or gestational diabetes in 1 or more first- or second-degree relatives; (5) good general health; (6) the ability to speak and understand spoken English; or (7) mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms, as indicated by a total score of 16 or higher on the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D). Volunteers were excluded from participating if they (1) had major depressive disorder, or another full-syndrome psychiatric disorder, that necessitated more intensive psychological treatment; (2) had major medical issues such as T2D (evaluated as fasting glucose >126 mg/dL); (3) were using any medications that could affect mood or insulin resistance such as stimulants or antidepressants, or (4) if they were pregnant.

Case Description

Details have been sufficiently modified to protect confidentiality. “Abby” was chosen as a participant for this case study based on her adherence to the study protocol including attendance at all visits and group intervention sessions. Abby was a 16-year-old Caucasian female in the 11th grade, living with her biological parents and 20-year-old brother when she entered the study. At her baseline visit, Abby had a BMI of 42 kg/m2, at the 99th percentile for age and sex. As assessed by self-report of breast development, Abby’s pubertal stage was Tanner 5, indicating that she was in late puberty. At baseline, Abby endorsed overeating episodes twice per month, but she denied binge eating or loss-of-control eating. She reported moderately elevated baseline depressive symptoms, as indicated by a CES-D total score of 27. By interview, she endorsed depressed mood, moderate insomnia, mild feelings of irritability, and mild thoughts of worthlessness. She denied current or past suicidal ideation or behavior. She did not currently meet criteria for a full-syndrome depressive or other psychiatric disorder, but she reported a past history of major depressive disorder occurring at 13 years of age and lasting approximately 4 months. She perceived that this episode had been triggered primarily by feelings of loneliness related to social difficulties, such as a lack of close friendships in middle school and feeling socially isolated.

Abby reported a close relationship with her father, but periodic mild arguments with her mother and brother, which were not highly distressing but did lessen the perceived closeness in those relationships. She reported above-average academic achievement. She was enrolled in simultaneous coursework at a public high school and local college, which she perceived as stressful academically, but rewarding socially in that it offered the opportunity to interact with more mature peers. Despite having a best friend, she described difficulties making friends and had few same-age peers. She was involved in a number of extracurricular and volunteer activities, including art programs, childcare, and church.

Procedure

All procedures were conducted at Colorado State University (Fort Collins, CO, USA). The intervention was delivered in an outpatient psychotherapy clinic, and assessments were conducted in a research laboratory. Prior to initiating the mindfulness group, parental guardian informed consent and adolescent assent were obtained; a family health history interview was administered with the parent; and baseline measures were assessed. Abby then participated in a 6-session weekly mindfulness-based group program. Her measures were re-evaluated immediately on conclusion of the group, and again, 1 year later.

Learning to BREATHE.

Learning to BREATHE (L2B) is a manualized mindfulness-based group program designed as a universal prevention curriculum for the socioemotional health of middle and high school aged adolescents.34 We modified the intervention minimally. We provided a brief rationale for the use of mindfulness for T2D prevention, standardized the number and length of sessions as 6 weekly 1-hour group meetings, and designated the specific modules for delivery in each session. Content of the 1-hour sessions focus on a theme for each of the 6 weeks of the program that correspond to the letters in the word BREATHE: (1) Body: body awareness; (2) Reflection: understanding and working with thoughts; (3) Emotions: understanding and working with feelings; (4) Attention: integrating awareness of thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations; (5) Tenderness: reducing harmful self-judgments; and (6) Healthy Habits of Mind: integrating mindful awareness into daily life, and the last E standing for Empowerment, the overall goal of the program.34 The curriculum includes core mindfulness practices such as the body scan, mindfulness of thoughts, mindfulness of emotions, a loving kindness practice, and mindful, gentle movement or yoga woven together with psychoeducation and interactive, group activities.34 To promote continued practice and engagement with the content in between group sessions, each group member was asked to complete homework. Homework assignments included the combination of making time for a brief (5- to 10-min) formal mindfulness practice at least once during the week and engaging in informal mindfulness practices that could be integrated into many parts of an adolescent’s daily life (eg, dot stickers as a reminder to take a mindful breath). To facilitate home practice, each group member was provided with a home practice workbook, a yoga mat and meditation cushion, and audio recordings of guided mindfulness practices. The program was cofacilitated by a licensed clinical child psychologist and a graduate student matriculated in marriage and family therapy. Facilitators participated in a 2-day training workshop on L2B and received weekly facilitation feedback by the curriculum developer, Dr Patricia Broderick. They also maintained a personal mindfulness practice throughout program delivery.

Psychological Interview and Survey Measures.

The mindful attention awareness scale (MAAS)35 was administered to measure trait mindfulness at each time point. A total score is calculated as the sum of all 15 items, with higher scores reflecting greater mindfulness. The schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children (K-SADS)36 was conducted with Abby at baseline to evaluate current and past diagnostic psychopathology. At 6-week and 1-year follow-ups, only the K-SADS depressive episode module was administered. Abby also completed the 20-item CES-D as a continuous measure of depressive symptoms.37 The CES-D total score is calculated as the sum of all items, with higher scores reflecting more elevated depressive symptoms. The 14-item perceived stress scale (PSS)38 was used to assess subjective stress. The total score is calculated as the sum of all items, with higher scores reflecting greater levels of perceived stress. Abby completed the questionnaire on eating and weight patterns-revised (QEWP-R)39 to assess several types of overeating episodes: “overeating,” referring to reported intake of too much food without a sense of loss-of-control; “binge eating,” referring to reported overeating of an unambiguously large amount of food (eg, 1 large pizza) with a lack of control over what or how much is consumed; and “loss-of-control eating,” defined as the subjective feeling of losing control over eating any type or amount of food (eg, 2 cookies or 20 cookies).39

A brief rating form was administered at the outset of all sessions to track weekly mood and to monitor suicidal ideation. In addition, a 14-item program acceptability questionnaire was administered at the conclusion of the program to assess overall experience with the group, the facilitators, other group members, and the content of the curriculum.

Biological Measures.

At each time point, salivary cortisol awaking response was assessed as an index of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity.40 Cortisol awaking response was estimated as the increase in salivary cortisol from waking to 15 minutes after waking. Fasting venous blood samples were collected to determine the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR) from fasting insulin and glucose concentrations.41 Serum insulin was analyzed at the University of Colorado Denver’s Clinical and Translational Research Center core laboratory with radioimmunoassay (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). An automated device (2300 STAT Plus Glucose Lactate Analyser, YSI Inc, Yellow Springs, OH, USA) was used to evaluate glucose immediately. Height and fasting weight were measured to compute BMI (kg/m2) and age-adjusted BMI indices according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 standards. Percent body fat was determined with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (Hologic, Discovery, QDR Series, Bedford, MA, USA).

RESULTS

Intervention Course

Eight female adolescents (5 Caucasian, 3 Latina) participated in Abby’s L2B group. Abby attended all 6 sessions, presenting in the group as forthcoming, thoughtful, and engaged in activities and in the session content. She was friendly, and she interacted with her peers prior to the start of sessions and during small group activities. Abby commented during the group sessions and on the postprogram acceptability survey that the mindfulness practices in a group setting felt “awkward” for her. Yet, she was one of the most vocal participants and by session 5, indicated feeling connected to the group.

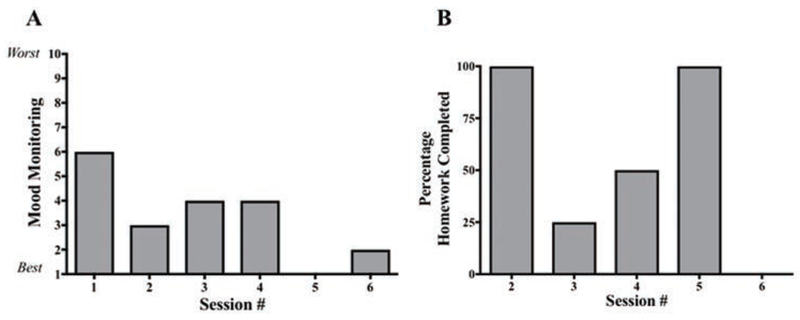

At the beginning of each session, Abby completed a mood monitoring form that used a 10-point scale to assess mood from 1 (best it has ever been) to 10 (worst it has ever been). She rated herself 6, 3, 4, 4, 1, and 1, for weeks 1 through 6, respectively (Figure 2A). Abby was inconsistent in completion of home practice; she completed 100% of assignments, 25%, 50%, 100%, and 0% in weeks 2 through 6, respectively (Figure 2B). In a program acceptability survey administered after the program, she stated that it was “extremely easy” for her to access the homework, but that she did not frequently complete homework because she “forgot a lot.” Abby reported informal mindfulness practice far more frequently than formal guided meditations or mindful movement exercises. Also on the program acceptability survey, Abby indicated that her mood was “happier” and that she felt “healthier” following the program. She enjoyed the group “very much” and found the group leaders “very helpful” and “very supportive.” Abby indicated that she felt only “a little comfortable” to open up and talk about tough topics during the group. The one recommendation that she made for changing the group program was to add beginning ice-breaker activities in the initial sessions to get to know other group members prior to starting mindfulness-based instruction and practices.

Figure 2.

Mood Ratings (Panel A) and Percentage Homework Completion (Panel B) by Session

Dispositional Mindfulness, Depressive Symptoms, and Perceived Stress

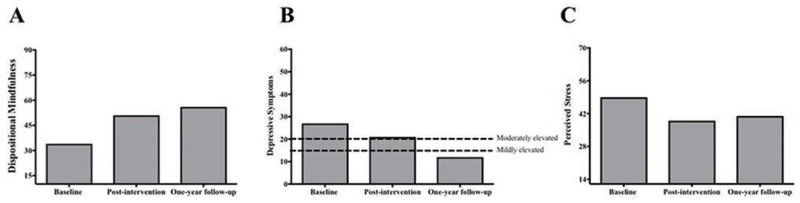

Figure 3 summarizes observed changes in the psychological outcomes of MAAS dispositional mindfulness, CES-D depressive symptoms, and PSS perceived stress. Abby had an increase in trait mindfulness following L2B. At baseline, she had a MAAS total sum score of 34 (range, 15 to 90). After L2B, her MAAS total score increased by 50% to 51%. This increase was sustained, even slightly improving, to 56 1 year later.

Figure 3.

Adolescent Participant’s Dispositional Mindfulness (Panel A), Depressive Symptoms (Panel B), and Perceived Stress (Panel C) at Baseline, an Immediate Postintervention Following Learning to BREATHE, and 1-year Follow-up

Abby’s CES-D total sum score was 27 at baseline (range, 0 to 60), 21 directly after L2B, and 12 (a decrease of 56%) at 1 year. Her 1-year reported-depressive symptoms were below a CES-D cut-point of 16 or 20, which has been proposed to be indicative of elevated depressive symptoms.42 Likewise, by interview assessment, she reported mild-to-moderate symptoms of depressed mood at baseline and postintervention, and she had no elevated symptoms at 1 year. She did not develop major depressive disorder at any point during the 1-year follow-up. Similar results were observed for perceived stress. Abby showed a decrease in self-reported stress on the PSS, starting with a total score of 49 at baseline, 39 at postintervention, and then 41, a decrease of 11% from baseline, at 1-year follow-up.

Stress-related Mechanisms: Overeating Behavior and Stress Physiology

Abby’s eating behavior fluctuated from baseline to 1 year. At baseline, she reported overeating episodes only; she did not report binge eating or loss-of-control eating. Just following L2B, she continued to report overeating episodes, and she also reported binge eating. At 1 year, she reported no episodes of overeating, binge eating, or loss-of-control eating. She did not meet criteria for binge eating disorder at any time point.

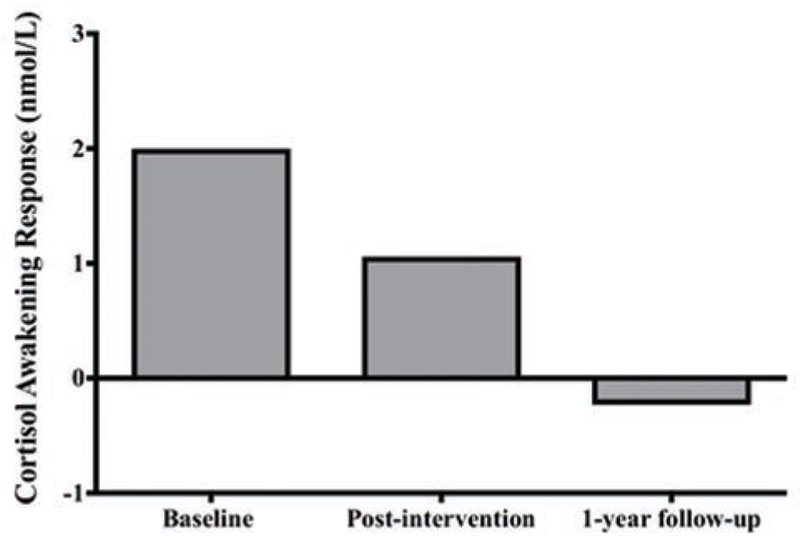

The trajectory of her cortisol awakening response followed a decreasing pattern (Figure 4). At baseline, Abby’s cortisol awakening response was 2.00 nmol/L, decreasing to 1.06 nmol/L after L2B, and to −0.23 nmol/L at 1-year follow-up.

Figure 4.

Adolescent Participant’s Cortisol Awakening Response at Baseline, an Immediate Postintervention Following Learning to BREATHE, and 1-year Follow-up

Insulin Resistance

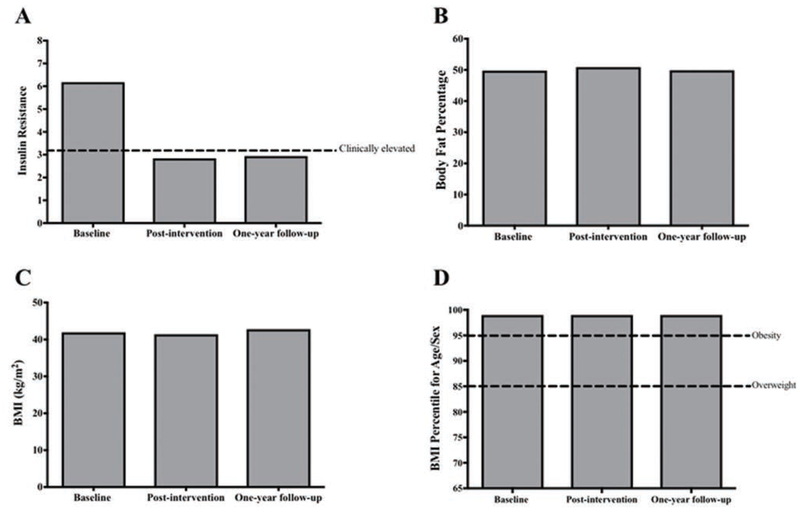

At baseline, Abby had severe insulin resistance, indicated by a HOMA-IR value of 6.18, well above a suggested clinically elevated cut-point of 3.16 for adolescents.41 Following completion of L2B, HOMA-IR was 2.84 and at 1 year was 2.94, below the recommended cut point for elevated insulin resistance in adolescents (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Adolescent Participant’s Insulin Resistance (Panel A), Body Fat Percentage (Panel B), Body Mass Index (BMI; kg/m2) (Panel C), and BMI Percentile (Panel D) at Baseline, an Immediate Postintervention Following Learning to BREATHE, and 1-year Follow-up

Body Composition

Abby’s percentage body fat remained stable with time (Figure 5B). Her BMI was also stable with values of 42 kg/m2 at baseline, 41 kg/m2 after L2B, and 42 kg/m2 at 1 year (Figure 5C). Likewise, she maintained a BMI at the 99th percentile throughout the follow-up (Figure 5D).

DISCUSSION

Results in Theoretical Context

Consistent with prior research and the guiding theoretical model, Abby’s response from participation in L2B illustrates a successful case example, in many ways, of a manualized mindfulness-based curriculum for the targeted prevention of T2D for adolescents at risk for this increasingly prevalent chronic disease. Prior to participating in the program, Abby had several characteristics related to high risk for continued progression toward worsening insulin resistance and eventual T2D onset, including obesity, elevated insulin resistance, and a family history of T2D. Moreover, she had a history of clinical depression in early adolescence and currently was experiencing moderately elevated depressive symptoms.

The L2B mindfulness-based intervention was designed to reduce stress and lessen depressive symptoms to ameliorate insulin resistance, regardless of changes in body weight or body fat. L2B is not, by design, a weight loss program. Consistent with these targeted outcomes, Abby showed improvements in trait mindfulness and decreases in depressive symptoms and perceived stress, which were maintained in the course of the 1 year following the program. Abby’s BMI and adiposity remained stable, but her initially, clinically elevated insulin resistance decreased notably to a degree that may be considered in the high end of the normal range. Abby was in the late stages of puberty, making it unlikely that this effect could be entirely accounted for by the resolution of pubertal insulin resistance.

Abby’s pattern of improved insulin resistance, without BMI or adiposity change, is consistent with the theoretical foundation and past empirical research suggesting that depressive symptoms may influence insulin resistance and T2D risk unique from energy balance.11–13 Although specific mechanisms for Abby’s improvements cannot be identified in this case report design, we hypothesize that the theoretically proposed effects of mindfulness on stress-related behavior and physiology might be at play.14 L2B encourages adolescents to relate to unpleasant experiences with acceptance rather than avoidance. In later sessions, Abby commented on a change that she was witnessing in her ability to recognize her experience and to remain calm by practicing mindfulness in situations that previously would have been distressing. These skills may have led to the qualitative reductions she experienced in perceived stress and depressive symptoms. Abby’s underlying stress physiology could have also been impacted by her perceived reductions in reactivity to stress. Her cortisol awakening response decreased directly after L2B and 1-year later, as compared with baseline.

Further, L2B trains adolescents to attend to physical sensations through breath awareness and recognition of how emotions manifest in the body.34 This training may increase adolescents’ ability to distinguish physiological cues triggered by hunger from those triggered by emotion. Abby reported periodic overeating initially and binge eating just after L2B. Yet, by 1 year, she endorsed neither, which may be attributable to enhanced, mindful attention to stress-related overeating patterns and ultimately, the longer-term remission of overeating and binge eating. This pattern is consistent with data suggesting that mindfulness inversely relates to overeating patterns in adolescents, including binge eating and eating in the absence of physiological hunger.21

Clinical Implications

This case report highlights important considerations for the successful implementation of mindfulness-based groups with adolescents at risk for T2D, namely using a socially connected, supportive group format, making abstract concepts relatable, and supporting adherence to home practice. One notable aspect of this case is that Abby struggled with social relationships, which is highly consistent with previous literature suggesting that adolescents with overweight or obesity are frequently more likely to be peripheral to social networks and to experience social isolation and victimization.43 The support of a group in which members share the same health-related risk increases the potential for change in health-related behaviors.44 Thus, increasing positive social connection is arguably an important component of preventive interventions for T2D in adolescents. Abby’s initial subjective discomfort that she reported experiencing in the group setting indicates that thoughtful facilitation of mindfulness-based programs is necessary to foster social connections among participants in the group. Based on Abby’s experience and her program feedback, we learned the importance of ensuring adequate time for rapport-building among group members. Concretely, this intention can be supported by initial icebreakers as well as incorporating designated sharing time throughout later sessions within adolescent dyads and/or smaller groups. Further, facilitators can emphasize common experience among group members to promote connection and possibly support self-compassion.

Researchers have wondered about adolescent’s capacity to understand mindfulness as an intervention, given that the training elements have internal and abstract features. Qualitatively, we learned that group facilitators’ ability to elicit recognition of internal experience and to connect session content to an adolescent’s personal life was of utmost importance. L2B focuses activities and discussions on situations that adolescents often encounter in daily life such as peer relationships and stressors related to school. Abby frequently responded to facilitators’ queries with answers indicating that she was reflecting on her personal experience. For example, she reported relating the content about mindfulness of emotions to her interpersonal relationships, to become more aware of situations when she might otherwise be emotionally reactive. To encourage open sharing of such experiences, facilitators acknowledged that much of the benefits of the program come from sharing real-life experiences, which may require sitting with some discomfort. Further, facilitators of Abby’s group frequently asked the question, “What was that like?” and “How is that different from the way you usually experience (a given situation)?” We believe, that although the L2B curriculum provides a strong framework for activities and effective talking points for reflecting after activities, the facilitator’s ability to skillfully move through content while allowing for time to discuss and reflect on internal processes was key to successful outcomes for Abby.

Abby’s difficulty with adherence to formal mindfulness practice outside of group sessions is an issue reported previously.45 We explored use of technology (eg, loaning tablets) to ensure access to practice recordings, but tools to increase accessibility and adherence require refinement and further testing. Possible directions include using text reminders more effective mobile applications. Further, parents were not engaged as part of the L2B intervention, yet we believe there may be benefit to having parents understand the home practice elements to encourage accountability and creation of a home environment that encourages these practices.

CONCLUSIONS

The current case report illustrates that there may be merit in intervening with adolescents at risk for T2D in a different way than solely diet and exercise-based programs. Not only did Abby see an increase in her trait mindfulness and a decrease in her insulin resistance, but she also endorsed that the program helped her feel generally healthier and happier. Although larger randomized controlled trials are necessary to pinpoint specific therapeutic mechanisms through which mindfulness-based interventions alleviate depressive symptoms and insulin resistance in adolescents at risk for T2D with depressive symptoms, we hope the implications from Abby’s experience can guide clinicians and clinical scientists as they continue to explore this approach.

We believe that a mindfulness-based intervention component may be an important addition to prevention for adolescents at risk for T2D whose stress and depressive symptoms contribute to insulin resistance. Yet there remain barriers to implementation. Adolescents are difficult to engage in prevention efforts, specifically because of multiple demands on time, requirements on families to invest in the process, and peer influence. Future research should evaluate the best venue for reaching adolescents who may benefit the most from coordinated prevention efforts for depression and T2D. Further, although we believe that the small, all-female group was conducive to fostering social connections and allowing participants comfort in sharing their experience, further research is needed to determine optimal conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by grant R00HD069516 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Footnotes

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Stephanie L. Dalager, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Shelly Annameier, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Colorado State University.

Stephanie M. Bruggink, Department of Human Development, and Family Studies, Colorado State University.

Bernadette Pivarunas, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Colorado State University.

J. Douglas Coatsworth, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Colorado State University.

Arlene A. Schmid, Department of Occupational Therapy, Colorado State University.

Christopher Bell, Department of Health and Exercise Science, Colorado State University.

Patricia Broderick, Bennett Pierce Prevention Research Center, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania.

Kirk Warren Brown, Department of Psychology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia.

Jordan Quaglia, Department of Psychology, Virginia Commonwealth University, and in the Department of Contemplative Psychology, Naropa University, Boulder Colorado.

Lauren B. Shomaker, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Colorado State University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dabelea D, Mayer-Davis EJ, Saydah S, et al. Prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among children and adolescents from 2001 to 2009. JAMA. 2014;311(17):1778–1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017(288):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nadeau KJ, Anderson BJ, Berg EG, et al. Youth-onset type 2 diabetes consensus report: Current status, challenges, and priorities. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(9):1635–1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeBoer MD. Obesity, systemic inflammation, and increased risk for cardiovascular disease and diabetes among adolescents: A need for screening tools to target interventions. Nutrition. 2013;29(2):379–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reaven GM. Banting lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37(12):1595–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alberga AS, Sigal RJ, Goldfield G, Prud’homme D, Kenny GP. Overweight and obese teenagers: why is adolescence a critical period? Pediatr Obes. 2012;7(4):261–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holt RI, de Groot M, Golden SH. Diabetes and depression. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14(6):491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodman E, Whitaker RC. A prospective study of the role of depression in the development and persistence of adolescent obesity. Pediatrics. 2002;110(3):497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latner JD, Schwartz MB. Weight bias in a child’s world In: Brownell KD, Puhl RM, Schwartz MB, Rudd L, eds. Weight bias: Nature, consequences, and remedies. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hannon TS, Li Z, Tu W, et al. Depressive symptoms are associated with fasting insulin resistance in obese youth. Pediatr Obes. 2014;9(5):e103–e107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shomaker LB, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Young-Hyman D, et al. Psychological symptoms and insulin sensitivity in adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes. 2010;11(6):417–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shomaker LB, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Stern EA, et al. Longitudinal study of depressive symptoms and progression of insulin resistance in youth at risk for adult obesity. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(11):2458–2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suglia SF, Demmer RT, Wahi R, Keyes KM, Koenen KC. Depressive symptoms during adolescence and young adulthood and the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183(4):269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golden SH. A review of the evidence for a neuroendocrine link between stress, depression and diabetes mellitus. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2007;3(4):252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joseph JJ, Golden SH. Cortisol dysregulation: The bidirectional link between stress, depression, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2017;1391(1):20–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.William H, Simmons LA, Tanabe P. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in advanced nursing practice: A nonpharmacologic approach to health promotion, chronic disease management, and symptom control. J Holistic Nursing. 2015;33(3):247–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kabat-Zinn J Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life. New York, NY: Hyperion; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kallapiran K, Koo S, Kirubakaran R, Hancock K. Effectiveness of mindfulness in improving mental health symptoms of children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2015;20:182–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godsey J The role of mindfulness based interventions in the treatment of obesity and eating disorders: An integrative review. Complement Ther Med. 2013;21(4):430–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daubenmier J, Hayden D, Chang V, Epel E. It’s not what you think, it’s how you relate to it: dispositional mindfulness moderates the relationship between psychological distress and the cortisol awakening response. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;48:11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pivarunas B, Kelly NR, Pickworth CK, et al. Mindfulness and eating behavior in adolescent girls at risk for type 2 diabetes. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48(6):563–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pidgeon A, Lacota K, Champion J. The moderating effects of mindfulness on psychological distress and emotional eating behaviour. Austr Psychol. 2013;48:262–269. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jordan CH, Wang W, Donatoni LR. Mindful eating: Trait and state mindfulness predicts healthier eating behavior. Pers Ind Diff. 2014;68:107–111. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abbott RA, Whear R, Rodgers LR, et al. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness based cognitive therapy in vascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Psychosom Res. 2014;76(5):341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartmann M, Kopf S, Kircher C, et al. Sustained effects of a mindfulness-based stress-reduction intervention in type 2 diabetic patients: Design and first results of a randomized controlled trial (the Heidelberger Diabetes and Stress-study). Diabetes Care. 2012;35(5):945–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tovote KA, Schroevers MJ, Snippe E, et al. Long-term effects of individual mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and cognitive behavior therapy for depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes: a randomized trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(3):186–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Son J, Nyklicek I, Pop VJ, Blonk MC, Erdtsieck RJ, Pouwer F. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for people with diabetes and emotional problems: Longterm follow-up findings from the DiaMind randomized controlled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77(1):81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biegel GM, Brown KW, Shapiro SL, Schubert CM. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for the treatment of adolescent psychiatric outpatients: A randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(5):855–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bluth K, Campo RA, Pruteanu-Malinici S, Reams A, Mullarkey M, Broderick PC. A school-based mindfulness pilot study for ethnically diverse at-risk adolescents. Mindfulness (N Y). 2016;7(1):90–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sibinga EM, Webb L, Ghazarian SR, Ellen JM. School-based mindfulness instruction: An RCT. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan L, Martin G. Taming the adolescent mind: preliminary report of a mindfulness-based psychological intervention for adolescents with clinical heterogeneous mental health diagnoses. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;18(2):300–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barnes VA, Orme-Johnson DW. Prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease in adolescents and adults through the Transcendental Meditation(R) Program: A research review update. Curr Hypertens Rev. 2012;8(3):227–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shomaker LB, Bruggink S, Pivarunas B, et al. Pilot randomized controlled trial of a mindfulness-based group intervention in adolescent girls at risk for type 2 diabetes with depressive symptoms. Complement Ther Med. 2017;32:66–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Broderick P Learning to BREATHE: A Mindfulness Curriculum for Adolescents to Cultivate Emotion Regulation, Attention, and Performance. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(4):822–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolesc. 1991;20(2):149–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spitzer R, Yanovski SZ, Marcus M. The Questionnaire of Eating and Weight Patterns-Revised. New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pruessner JC, Wolf OT, Hellhammer DH, et al. Free cortisol levels after awakening: A reliable biological marker for the assessment of adrenocortical activity. Life Sci. 1997;61(26):2539–2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keskin M, Kurtoglu S, Kendirci M, Atabek ME, Yazici C. Homeostasis model assessment is more reliable than the fasting glucose/insulin ratio and quantitative insulin sensitivity check index for assessing insulin resistance among obese children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):e500–e503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stockings E, Degenhardt L, Lee YY, et al. Symptom screening scales for detecting major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis of reliability, validity and diagnostic utility. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:447–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strauss RS, Pollack HA. Social marginalization of overweight children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(8):746–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sorkin DH, Mavandadi S, Rook KS, et al. Dyadic collaboration in shared health behavior change: the effects of a randomized trial to test a lifestyle intervention for high-risk Latinas. Health Psychol. 2014;33(6):566–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bluth K, Gaylord SA, Campo RA, Mullarkey MC, Hobbs L. Making friends with yourself: A mixed methods pilot study of a mindful self-compassion program for adolescents. Mindfulness (N Y). 2016;7(2):479–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]