Abstract

Purpose

The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is a National Institutes of Health initiative designed to improve patient-reported outcomes using state-of-the-art psychometric methods. The aim of this study is to describe qualitative efforts to identify and refine items from psychological well-being subdomains for future testing, psychometric evaluation, and inclusion within PROMIS.

Method

Seventy-two items from eight existing measures of positive affect, life satisfaction, meaning & purpose, and general self-efficacy were reviewed, and 48 new items were identified or written where content was lacking. Cognitive interviews were conducted in patients with cancer (n = 20; 5 interviews per item) to evaluate comprehensibility, clarity, and response options of candidate items.

Results

A Lexile analysis confirmed that all items were written at the sixth grade reading level or below. A majority of patients demonstrated good understanding and logic for all items; however, nine items were identified as “moderately difficult” or “difficult” to answer. Patients reported a strong preference for confidence versus frequency response options for general self-efficacy items.

Conclusions

Altogether, 108 items were sufficiently comprehensible and clear (34 positive affect, 10 life satisfaction, 44 meaning & purpose, 20 general self-efficacy). Future research will examine the psychometric properties of the proposed item banks for further refinement and validation as PROMIS measures.

Keywords: Qualitative, Measure development, Well-being, Meaning, Positive affect, Life satisfaction, Self-efficacy, PROMIS, Cognitive interviews, Cancer

Introduction

The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®; http://nihpromis.org) is an NIH Roadmap initiative designed to improve patient-reported outcomes using state-of-the-art psychometric methods [1, 2]. The main goal of PROMIS® is to develop and evaluate a set of publicly available, efficient and flexible measurements of patient-reported outcomes for use by clinicians and patients in diverse research and clinical settings [1]. Despite the conceptual breadth of PROMIS®, in the initial wave of instrument development efforts, measures of psychological well-being for adults with acute and chronic health conditions were not included in the measurement framework. Many patient-reported measures of health status (e.g., pain, fatigue, depression) are conceptualized as a lack of symptoms rather than the presence of well-being. Thus, development of PROMIS® item banks for psychological well-being will address an important gap in the measurement framework and allow for precise measurement of emotional health rather than merely the absence of symptoms.

Informed by models of psychological well-being [3–11], we identified four cross-cutting subdomains: (1) positive affect—feelings that reflect a level of pleasurable engagement with the environment such as happiness, joy, excitement, enthusiasm, and contentment [12]; (2) life satisfaction—a person’s cognitive evaluation of life experiences and whether s/he likes her/his life or not [13]; (3) meaning and purpose—the extent to which a person feels her/his life matters or makes sense [14]; (4) general self-efficacy—a person’s belief in her/his capacity to manage functioning and have control over meaningful events [15]. Consensus on these subdomains was sought through a modified Delphi process and guided by a review of the literature, feedback from experts in the area of psychological well-being, follow-up semi-structured interviews with a subset of these experts, and discussion within the project team and among content expert consultants [16]. Importantly, each of these well-being subdomains represents key indicators of positive emotional health and has important linkages to other health outcomes [13, 14, 16]. This qualitative study aimed to identify and refine items from these related but distinct psychological well-being subdomains with a mixed cancer sample for future testing, psychometric evaluation, and inclusion within PROMIS®. Patients with a history of cancer provide an ideal sample for exploring psychological well-being themes since cancer can be a catalyst for reflection, psychosocial growth, and meaning [17, 18].

Methods

Participants and procedures

Items from existing measures of positive affect, life satisfaction, meaning & purpose, and general self-efficacy [16, 18] were reviewed for reading level, clarity, simplicity, and translatability. Items were excluded if they were > 6th grade reading level, double-barreled, colloquial or idiomatic, or had intellectual property restrictions. Translatability review was used to identify potential conceptual or linguistic difficulties in items and to suggest alternate wording more suitable for a culturally diverse population. In cases where content was lacking (e.g., missing or under-represented component(s) of a psychological well-being subdomain), new items were written by study investigators (JS, DC) and content experts (CP, LG, MFS, TM) to ensure adequate breadth of the well-being subdomains. Any inconsistencies in investigator recommendations were resolved through consensus. To minimize respondent burden, response options were standardized to a limited set of options. Four study forms of 30 items each were created from the 120 candidate items. All forms included items from each of the four psychological well-being subdomains.

Study procedures were approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board and eligible participants were identified via electronic medical record review and approached in-clinic at the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center or contacted by phone after approval was obtained from patients’ providers. Eligibility criteria included the following: (1) able to read and understand English, (2) able to provide informed consent, (3) at least 18 years of age, (4) currently or previously diagnosed with breast, colorectal, lung, or prostate cancer (the four most common cancer types among adults), and (5) a life expectancy of at least 6 months. Interested participants were consented and completed cognitive interviews in-person at a private office suite at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine or by phone. Interview guides (and probes) were adapted from existing interview guides used in other PROMIS® and similar measure development work [19, 20]. Consistent with PROMIS® guidelines for the cognitive interview phase of item development [21], we recruited a purposive sample so that one patient in each group of five had limited educational attainment (i.e., high school or below), and two patients in each group of five were racial or ethnic minorities. We also sought to balance group assignment to interview study form by gender, treatment status (on vs. off), cancer type, and cancer stage. Upon completion of the interviews, participants were compensated $30 for their time.

Study measures

Participants reviewed items from the NIH Toolbox’s Positive Affect, General Life Satisfaction, Meaning & Purpose, and General Self-Efficacy Item Banks [16, 22]. The Positive Affect Item Bank included 34 items previously adapted from among the PANAS-X [23], Affectometer 2 [24], and the FACIT-Sp [25]. The Life Satisfaction Item Bank included 10 items previously adapted from the Satisfaction with Life Scale [13] and Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale [26]. The General Self-Efficacy Item Bank included items previously adapted from the General Self-Efficacy Scale [15] with parallel item content (10 items each) for both frequency (“never” to “very often”) and newly written confidence response options (“I am not at all confident” to “I am very confident”). The Meaning & Purpose Item Bank included 18 items previously adapted from the Life Engagement Test [27], Meaning in Life Questionnaire-X [14], and the FACIT-Sp [25] and also included 38 newly written items to develop a more robust meaning and purpose item bank for the NIH PROMIS®.

Analysis

Each of the 120 candidate items was reviewed by five patients (30 items per patient) to evaluate comprehensibility (“Can you say this question in your own words?” “How did you choose your answer?”), clarity (“Was this question easy or hard to answer?” “Can you think of an easier way to word this question?”), and preference for response options (“How easy is it to tell the difference between each response group?” “Which group of responses is easiest/hardest to understand?” “Which group of responses do you prefer and why?”). Participant responses were coded by the study coordinator (MAS) for understanding and logic (1 = “understanding and/or logic is poor/different/wrong” to 3 = “understanding and/or logic is full/good”) and for ease of answering (1 = “difficult to answer” to 3 = “easy to answer”). Coding decisions were reviewed, discussed, and modified, as needed, by the study principal investigator (JS) and co-investigator (DC). Participant preferences for response options were summarized as percentages. Measurement science (JS, EH, DC) and content experts (CP, LG, MFS, TM) reviewed cognitive interview results and provided recommendations for reducing redundancy, maximizing clarity, and enhancing conceptual breadth.

Results

During the translatability review, ten items were identified as potentially problematic and were re-written prior to cognitive interviewing to be less idiomatic or ambiguous. A Lexile® analysis of candidate items found that all items were written at the sixth grade reading level or below. Twenty patients (M = 62.0 years old, SD = 10.8) completed cognitive interviews. Additional sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are available in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographic and clinical characteristics

| N=20 | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 10 | 50 |

| Male | 10 | 50 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic origin | 1 | 5 |

| Non-hispanic origin | 19 | 95 |

| Race | ||

| White | 12 | 60 |

| Black/African America | 7 | 35 |

| Other | 1 | 5 |

| Education | ||

| High school degree/GED or less | 6 | 30 |

| Some college | 6 | 30 |

| College degree | 5 | 25 |

| Graduate degree | 3 | 15 |

| Tract income level | ||

| Low (median family income % is < 50%) | 3 | 15 |

| Moderate (median family income % is > = 50% and < 80%) | 6 | 30 |

| Middle (median family income % is > = 80% and < 120%) | 4 | 20 |

| Upper (median family income % is > = 120%) | 7 | 35 |

| Cancer type | ||

| Breast | 5 | 25 |

| Prostate | 5 | 25 |

| Colorectal | 5 | 25 |

| Lung | 5 | 25 |

| Cancer stage | ||

| Early (Stages 0-II) | 9 | 45 |

| Advanced (Stages III-IV) | 11 | 55 |

| Treatment status | ||

| On treatment | 10 | 50 |

| Off treatment | 10 | 50 |

A majority of patients (at least 3 out of 5 in every “set”) indicated good understanding and logic for all candidate items (See Table 2 for sample responses). However, nine (6 meaning & purpose) items were identified by a majority of patients as “moderately difficult” or “difficult” to answer (e.g., “I realize my life has a central theme”). In terms of general self-efficacy response options, patients reported a preference for confidence (55%) vs. frequency (30%) options.

Table 2.

Sample cognitive interview responses

| Content | Item stem | Response options | Patients’ comments about items (patients’ Age/Sex) | Example of… |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive affect | I felt attentive | Not at all A little bit Somewhat Quite a bit Very much | “Same as question 22 (I felt cheerful). I have a wonderful life. I’m blessed to be here. I try to be cheerful and happy.” (69/M) | Poor understanding and logic |

| Life satisfaction | In most ways, my life is close to perfect | Strongly disagree Disagree Slightly disagree Neither agree nor disagree Slightly agree Agree Strongly agree | “Hard because of the word ‘perfect’. I don’t know how to answer it. What is perfection?” (59/F) | Difficult to answer |

| Meaning & purpose | I believe there is an ultimate meaning of life | Strongly disagree Disagree Neither agree nor disagree Agree Strongly agree | “What exactly is an ‘ultimate meaning of life’? I have ethical and moral standards, but I don’t know if that’s an ultimate meaning. This one was very hard; I had no answer for it.” (70/M) | Partial understanding; difficult to answer |

| Self-efficacy | I can handle whatever comes my way | Never Almost Never Sometimes Fairly Often Very Often | “I have a circle of people to help me. I can think of cancer being the worst thing that came my way. I rely on people.” (81/F) | Full understanding and good logic |

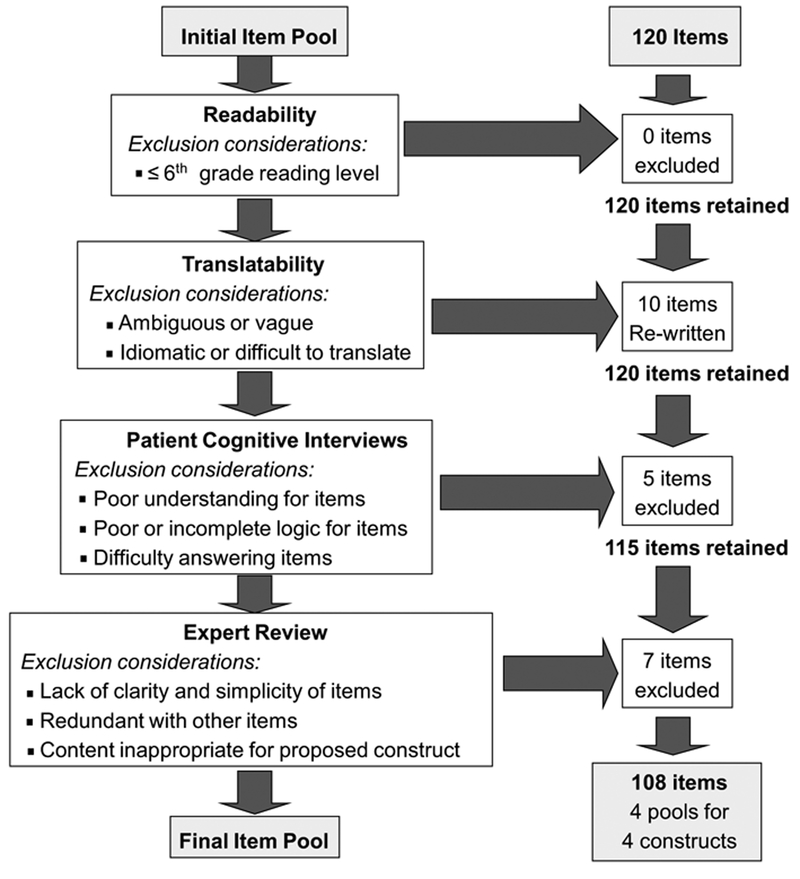

Based on cognitive interview data and expert review, 12 items were omitted from further consideration (all from the meaning & purpose item pool). Five of those items were excluded as a result of cognitive interview feedback which revealed that patients had poor understanding, incomplete logic, and/or difficulty answering the items. The remaining 7 items were excluded after expert review which highlighted a lack of clarity or simplicity (2 items), redundancy with other items (3 items), and content that was beyond the scope of the proposed construct (2 items). In addition, 3 items that were considered “moderately difficult” or “difficult” to answer (2 general self-efficacy items and 1 life satisfaction item) were retained for further testing given their inclusion in existing legacy measures [13, 15]. Figure 1 provides a summary of the development and refinement of the PROMIS® item banks for psychological well-being based on the qualitative review process.

Fig. 1.

Exclusion considerations and results

Conclusions

Altogether, 108 items were identified for the next phase of testing. These included 34 positive affect, 10 general life satisfaction, 18 meaning and purpose, and 10 general self-efficacy items from the NIH Toolbox. Within this process, confidence response options were written for the 10 general self-efficacy items to better reflect patient preferences and align with self-efficacy theory [28]. For the meaning and purpose items, additional content was identified and written to enhance conceptual breadth of this important subdomain of psychological well-being.

As a result of the qualitative review process, the item pool for psychological well-being was refined in preparation for quantitative testing. Importantly, all items were sufficiently comprehensible and free of ambiguity. Perhaps not surprisingly and relative to other psychological well-being items, meaning and purpose items were more difficult to answer. At the construct level, meaning and purpose can sometimes be nebulous with ambiguous conceptual boundaries, resulting in challenges to identify clear and comprehensible items that adequately reflect this important construct [29]. This resulted in “pruning” of the meaning and purpose item pool to identify the optimal candidates for additional testing. Future research will examine the psychometric properties of the proposed psychological well-being item sets using a general population sample for further refinement and validation as potential PROMIS® measures.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Helena Correia, the Director of Translations for the Department of Medical Social Sciences at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, for her work conducting the translatability review in support of this manuscript.

Funding Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the NIH under Award Number K07CA158008.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no significant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical approval All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review board of Northwestern University and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed consent Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

References

- 1.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. (2010). The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 6311, 1179–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia SF, Cella D, Clauser SB, et al. (2007). Standardizing patient-reported outcomes assessment in cancer clinical trials: A patient-reported outcomes measurement information system initiative. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2532, 5106–5112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryff CD (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Exploration on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 576, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peterson C, & Seligman MEP (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jahoda M (1958). Current concepts of positive mental health. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Offer D, & Sabshin M (1966). Normality: Theoretical and clinical concepts of mental health. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coan RW (1974). The optimal personality; An empirical and theoretical analysis. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coan RW (1977). Hero, artist, sage, or saint?: A survey of views on what is variously called mental health, normality, maturity, self-actualization, and human fulfillment. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Compton WC (2001). Toward a tripartite factor structure of mental health: Subjective well-being, personal growth, and religiosity. The Journal of psychology, 1355, 486–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee Duckworth A, Steen TA, & Seligman ME (2005). Positive psychology in clinical practice. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 629–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menninger WC, Hall BH, Alumbaugh GK, & Brosin HW (1967). A psychiatrist for a troubled world: Selected papers of William C. Menninger, M.D New York: Viking Press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pressman SD, & Cohen S (2005). Does positive affect influence health? Psychological Bulletin, 1316, 925–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, & Griffin S (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 491, 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steger MF, Frazier P, Oishi S, & Kaler M (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 531, 80–93. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwarzer R, & Jerusalem M (1995). Generalized self efficacy scale In Weinman J, Wright S & Johnston M (Eds.), Measures in health psychology (pp. 35–37). Windsor: NFER-Nelson. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salsman J, Lai J-S, Hendrie H, et al. (2014). Assessing psychological well-being: Self-report instruments for the NIH Tool-box. Quality of Life Research, 231, 205–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park CL, & Folkman S (1997). Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Review of General Psychology, 12, 115–144. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai JS, Garcia SF, Salsman JM, Rosenbloom S, & Cella D (2012). The psychosocial impact of cancer: Evidence in support of independent general positive and negative components. Quality of Life Research, 212, 195–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ravens-Sieberer U, Devine J, Bevans K, et al. (2014). Subjective well-being measures for children were developed within the PROMIS project: Presentation of first results. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 672, 207–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Victorson D, Choi S, Judson MA, & Cella D (2013). Development and testing of item response theory-based item banks and short forms for eye, skin and lung problems in sarcoidosis. Quality of Life Research, 244, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.PROMIS Health Organization and PROMIS Cooperative Group (2013). PROMIS® instrument development and validation: Scientific standards version 2.0. (Revised May 2013). http://www.nihpromis.org/Documents/PROMISStandards_Vers2.0_Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kupst MJ, Butt Z, Stoney CM, et al. (2015). Assessment of stress and self-efficacy for the NIH Toolbox for Neurological and Behavioral Function. Anxiety Stress Coping, 285, 531–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watson D, & Clark LA (1994). The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule—expanded form. http://www2.psychology.uiowa.edu/faculty/Clark/PANAS-X.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kammann R, & Flett R (1983). Affectometer 2: A scale to measure current level of general happiness. Australian Journal of Psychology, 352, 259–265. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, & Cella D (2002). Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: The functional assessment of chronic illness therapy–spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-Sp). Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 241, 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huebner ES (1991). Initial development of the student’s life satisfaction scale. School Psychology International, 123, 231–240. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheier M, Wrosch C, Baum A, et al. (2006). The life engagement test: Assessing purpose in life. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 293, 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bandura A (1994). Self-efficacy In Ramachaudran VS (ed.) Encyclopedia of human behavior. Vol 4, (pp. 71–81). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 29.George LS, & Park CL (2016). Meaning in life as comprehension, purpose, and mattering: Toward integration and new research questions. Review of General Psychology, 203, 205. [Google Scholar]