Abstract

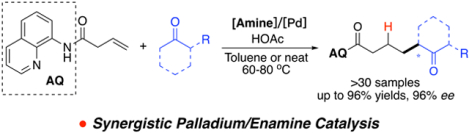

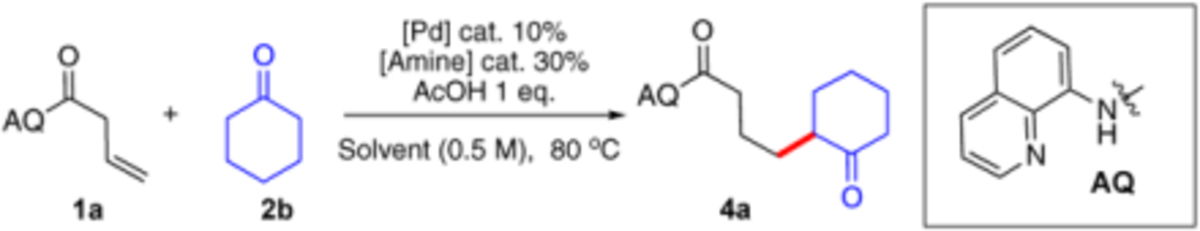

Synergistic palladium and enamine catalysis were explored to promote ketone addition to unactivated olefin. Secondary amine-based organocatalyst was identified as the optimal co-catalyst for the directed Pd-catalyzed alkene activation. Furthermore, asymmetric hydrocarbon functionalization of unactivated alkenes was also achieved with good to excellent yield (up to 96% yields) and stereoselectivity (up to 96% ee). This strategy presented an efficient approach to prepare α−branched ketone derivatives under mild conditions.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

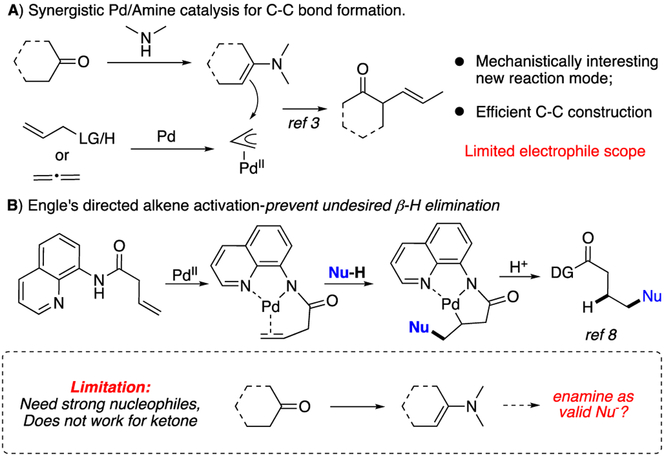

Synergistic metal/organo catalysis has flourished over the past decade, enabling a combination of the orthogonal reactivity between transition metal chemistry and organocatalysis.1 In particular, combining palladium and enamine chemistry offered a powerful toolbox for C-C bonds construction.2 A general reaction pattern is employing enamine as a nucleophile to react with a Pd-activated carbon electrophile. One type of this well-explored electrophile is π-allyl complex, which is often generated in-situ via Pd addition/oxidation toward allyl or allene moieties (Scheme 1A).3 Although this protocol represents an efficient approach for a C-C bond construction, it suffers from several limitations, including limited substrate scope and lack of effective stereochemistry control.4 This is mainly due to A) the requirement of a pre-functionalized alkene to form Pd π-allyl complex and B) problematic reversible β-H elimination involved. Therefore, developing new reaction partners that can facilitate transformations under this dual-catalysis mode will not only offer practical synthetic utility but also foster mechanistic insight to further advance this intriguing reaction pattern.

Scheme 1.

Combining organo and Pd catalysis for alkene functionalization

The intrinsic reactivity of C-C double bonds allows alkene to own a privileged position in the organic synthesis.5 Lewis acid catalyzed nucleophilic addition of alkenes have become a powerful synthetic approach for C-C and C-X bond construction.6 However, palladium is considered as a weak π-acid towards alkene activation, therefore, a strong nucleophile is required to attack the Pd-activated alkene.7 Moreover, the resulting Pd-C intermediate could undergo fast β-H elimination, giving alkene products and other potential undesired side reactions. To overcome this problem, in 2016, Engle and coworkers first reported the application of bidentate directing group (DG) strategy to enhance the reactivity of Pd, allowing un-activated alkene to be readily attacked by soft carbon nucleophiles.8 More importantly, with a more sterically constrained Pd intermediate, the β-H elimination was successfully inhibited (Scheme 1B). This seminal work highlighted the advantage of applying the bidentate DGs in A) improve the reactivity of Pd(II) cation and B) secure olefin hydrocarbofunctionalization through protodemetallation. Although a wide range of carbon nucleophiles, including 1,3-dicarbonyls, aryl carbonyls, and electron-rich arenes, have been successfully applied for this transformation, ketones and aldehydes remained problematic. Also, only few examples have been reported for enantioselective addition to unactivated alkene using this strategy.9 Inspired by these findings, we envisioned that the combination of Pd-catalyzed directed alkene activation with enamine addition could offer a valid strategy to further extend reaction scope to ketone derivatives. More importantly, the adoption of a chiral amine catalysts will provide an effective stereochemistry control to achieve asymmetric α-alkylation of a ketone.

It is important to note here that as we were working on this idea independently, one paper with similar design from the Gong group was published, in which they reported the alkylation of substituted cyclic ketones through enamine activation.10, The desired α-alkylation was obtained in good yields and ee. We herein report our efforts on this novel transformation with alternative reaction conditions. We are able to extend the substrate scope to various of acetophenones, as well as β-keto-esters. It is our hope to offer another perspective on how we achieved this transformation from a different approach.

Results and discussion

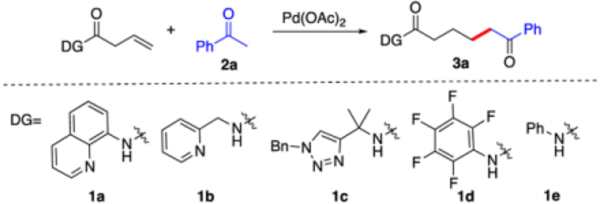

Considering that the directing group is crucial for increasing the reactivity of Pd catalyst, we first screened some common used directing groups (1a-1e) under Engle’s condition (HOAc, MeCN, 120 °C). The results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Screening directing groupsa

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| DGs | Conditions | Conv.b | Yieldb |

| 1a-1e | MeCN, 120 °C | <5% | <5% |

| 1a | L-Proline 20%, MeCN, 120 °C | 70% | 60% |

| 1b-1e | L-Proline 20%, MeCN, 120 °C | <10% | <10% |

| 1a | Pyrrolidine 20%, Tol, 80 °C | 100% | 99%(94%c) |

Reaction conditions: 1a (1 eq.), 2a (3 eq.), Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol%), [amine] cat. (20 mol%), AcOH (1 eq.), solvent (0.5 M), 36 hours.

Conversion and yield were determined by 1H NMR using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as internal standard.

Isolated yield.

As expected, without the addition of amine, no desired product was observed in all the cases, which highlighted the challenge of applying acetophenone as a nucleophile toward Pd-activated alkene. Fortunately, when L-proline was applied as the co-catalyst with 8-aminoquinoline (AQ) as the directing group, the reaction successfully gave the desired addition product 3a in 60% NMR yield. Interestingly, other directing groups could not promote this transformation even with the addition of proline, emphasizing the unique roles of AQ in this reaction. After a series of conditions screening, pyrrolidine was identified as the optimal co-catalyst with toluene as the solvent. The reaction proceeded smoothly at 80 °C with nearly quantitative yield.

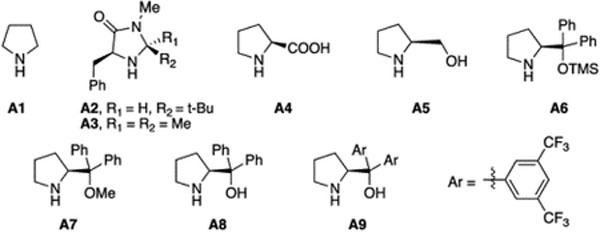

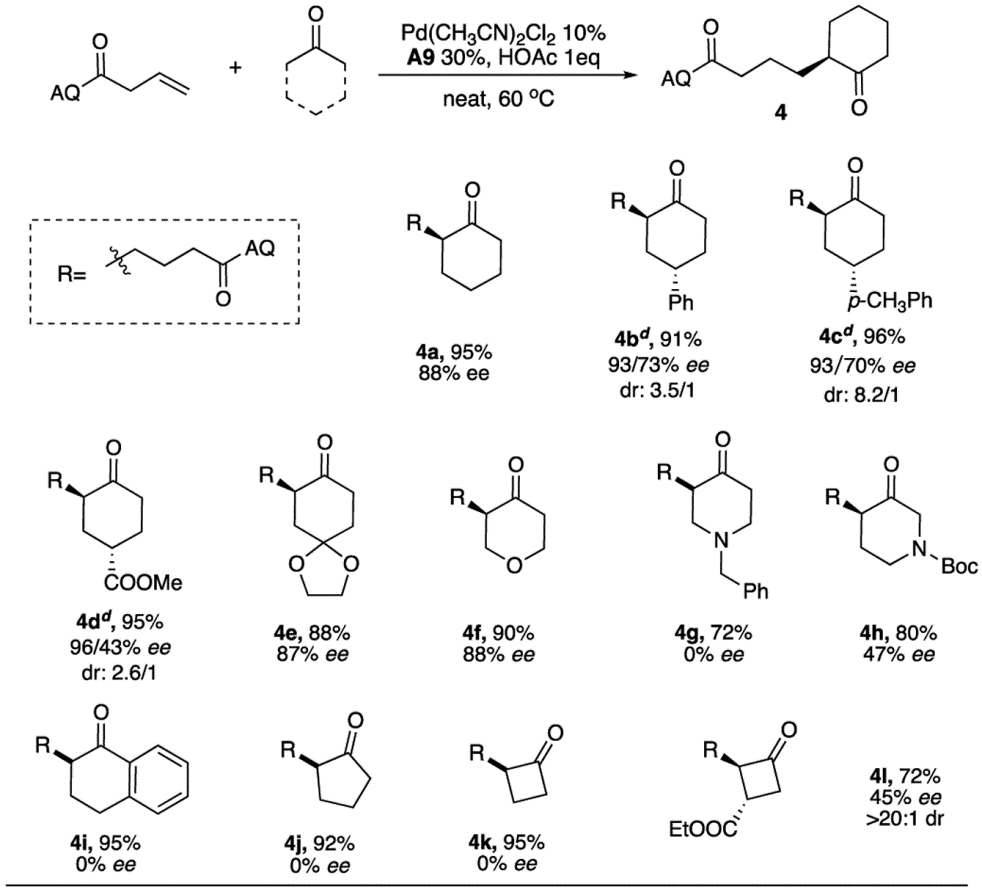

Inspired by this result, we then turned our attention into more challenging asymmetric addition with the assistant of chiral amines. Representative conditions screened are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Optimization of amines for palladium/enamine catalysisa

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | [Pd] | [Amine] | Sol. | Conv.b | Yieldb | ee%c |

| 1d | Pd(OAc)2 | n/a | MeCN | <5% | <5% | - |

| 2 | Pd(OAc)2 | A1 | Tol | 100% | 95% | - |

| 3 | Pd(OAc)2 | A2 or A3 | Tol | <20% | <20% | 0 |

| 4 | Pd(OAc)2 | A4 | Tol | 62% | 54% | 11% |

| 5 | Pd(CH3CN)2Cl2 | A4 | Tol | 79% | 77% | 15% |

| 6 | Pd(CH3CN)2Cl2 | A5 | Tol | 100% | 90% | 33% |

| 7 | Pd(CH3CN)2Cl2 | A6 | Tol | 100% | 91% | 63% |

| 8 | Pd(CH3CN)2Cl2 | A7 | Tol | 100% | 57% | <5% |

| 9 | Pd(CH3CN)2Cl2 | A8 | Tol | 100% | 96% | 65% |

| 10 | Pd(CH3CN)2Cl2 | A9 | Tol | 100% | 97% | 71% |

| 11e | Pd(CH3CN)2Cl2 | A9 | Tol | 100% | 97% | <5% |

| 12f | Pd(CH3CN)2Cl2 | A9 | Tol | 60% | 55% | 93% |

| 13f | Pd(CH3CN)2Cl2 | A9 | neat | 100% | 99% (95%)g | 88% |

| ||||||

Reaction conditions: [Pd] cat. (10 mol%), [amine] cat. (30 mol%), AcOH (1 eq.), solvent (0.5 M), under 80 °C, 24 hours.

Conversion and yield were determined by 1H NMR using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as internal standard.

ee value was determined by HPLC.

120 °C, 36 hours.

72 h.

60 °C, 24 hours.

Isolated yield.

As expected, treating 1a with cyclohexanone 2b under Pd/pyrrolidine conditions gave 4a in 95% yield, as expected (entry 2). Various chiral amine catalysts were then tested for stereoselectivity. The Macmillan catalysts were ineffective in this system, which might due to the lack of reactivity towards ketone.11 L-Proline gave a decreased conversion and yield with 11% ee of 4a. Clearly, a tight transition state with Pd and amine is crucial for good stereoselectivity. To avoid competitive OAc binding, Pd(CH3CN)2Cl2 was then employed. An increasing ee (15%) was obtained with L-proline as co-catalyst (entry 5). Finally, with Jorgensen catalyst A9, product 4a was obtained in 97% yield with 71% ee (entry 10). It is important to note that prolinol A8 gave the product in 65% ee, while the OMe protected ligand A7 gave almost no stereoselectivity (<5% ee). This result clearly suggested the importance of the hydroxyl group in promoting the stereoselectivity of the transformation. This is likely due to the coordination of OH with Pd intermediate, which not only accelerates the overall reaction rate by rendering the enamine addition into an intramolecular fashion, but also provides a good stereochemistry control. One challenge that prevents further improvement of the enantioselectivity is the racemization of product 4a. Extending reaction time resulted in a decreased ee value under the reaction conditions (entry 11). To further fine-tuning the reaction, we conducted the reaction at lower temperature (60 °C). Lower conversion (60%) and yield (55%) were observed, though higher ee was received (93%). To increase the reaction rate at a lower temperature, the neat condition was applied. The reaction gave 100% conversion and 95% isolated yield with 88% ee of 4a. Notably, under Gong’s conditions, only 60% ee was obtained, though with 93% yield. With this optimal condition revealed, the reaction scope was evaluated. Substrates 3 from methyl-ketone is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

|

Reaction conditions: Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol%), pyrrolidine (20 mol%), AcOH (1 eq.), solvent (0.5 M), 36 hours.

Isolated yield.

In general, over 90% yields were obtained with almost all tested acetophenone derivatives. Both EDG (3b–3d) and EWG (3e and 3f) modified ketones gave excellent yields. Slightly reduced yields were obtained with the ortho-substituted substrate (3j 89%, 3k, 82%) due to steric hindrance. Interestingly, aryl halide substrates (3g, 3h, and 3i) worked very well for this transformation without observation of Pd catalyzed oxidative addition of C-X bond, revealing an orthogonal reactivity compared with typical Pd(0) involved coupling reactions. With 4’-Iodoacetophenone 3j, modest yield was observed, due to the formation of heck type by-product in the presence of more active C-I bond. Finally, amino acid modified derivative (3o) was also suitable for this reaction, suggesting the potential application of this method in bio-compatible compound preparation. Internal alkene derivatives, (Z) and (E)-N-(quinolin-8-yl)hex-3-enamide, were unreactive. Moreover, compound 3a was synthesized in a gram scale, which indicated its practical synthetic value.

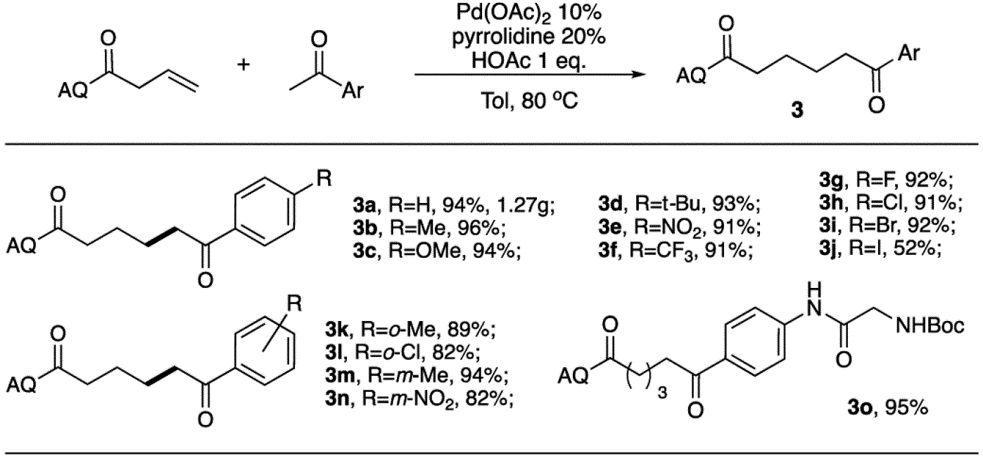

Exploration of asymmetric reaction performance with cyclic ketones was also performed and summarized in Table 4. Comparing with non-substituted cyclohexanone (4a), 4-substituted cyclohexanone derivatives (4b-4d) required a higher temperature (80 °C) to achieve the full conversion due to increased hindrance. Interestingly, in these cases problematic racemization was also inhibited, providing higher enantioselectivity. On the other hand, modest dr value were observed. Ketal derivative (4e) was also tolerated under this acidic condition without deprotection, excellent yield and ee were obtained. Next, both O and N containing cyclohexanone (4f-4h) were tested. 4-oxotetrahydropyran (4f) provided 90% yield and 88% ee, while 4-oxopiperidine (4g) failed to observe any enantioselectivity possibly because of a quick epimerization. By switching to Boc protection, 3-oxopiperidine (4h) was achieved with modest ee, resulting from resonance of amide group to lock the conformation. 1-Tetralone (4i) showed excellent yields with 0% ee due to the more acidic α-proton. Smaller cyclic ketones such as cyclopentanone (4j) and cyclobutanone (4k) gave excellent yields with no ee, which is likely due to the presence of more acidic α-proton, which caused quick racemization of the formed product. As a result, introduction of an ester on cyclobutanone (4l) to increase steric bulkiness not only resulted in moderate enantioselectivity (45% ee) but also delivered excellent dr value (> 20:1).

Table 4.

|

Reaction conditions: Pd(MeCN)2Cl2. (10 mol%), A9 (30 mol%), AcOH (1 eq.), 24 hours.

Isolated yield.

The dr and ee was determined by HPLC.

80 °C.

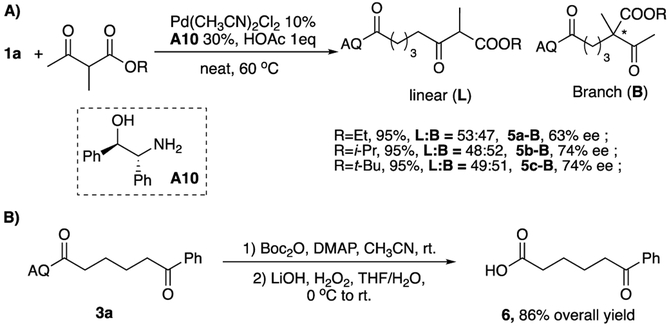

In addition to cyclic ketones, other carbonyl substrates were also explored (Scheme 2A). First, aldehyde was tested and proved not suitable for this transformation due to the undesired rapid aldol condensation side reaction. Other readily available ketone derivatives such as 1,3-diketones and β-keto-esters were also tested. In particular, we chose α-substituted 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds for further study because it could form product with a quaternary stereocenter to prevent racemization. After the extensive screening of catalysts (see details in SI), primary amine A10 was identified as an effective catalyst in promoting condensation of β-keto-ester with AQ-modified olefin (Table 5A). Although all ketone esters (5a, 5b, and 5c) showed excellent yield (95%), a regioselectivity issue (linear vs branch selectivity) was revealed as well, due to the formation of two possible enamine intermediates. All of these three substrates gave similar regioselectivity ratio (from 53:47 to 48:52). With the increasing size of substituted group R, the enantioselectivity would be increased from 63% to 74% ee. We also demonstrated that AQ directing group could be removed by a Boc protection-basic hydrolysis sequence, yielding the ε- keto acids 6 with 86% yield over two steps (Table 5B).12

Scheme 2.

Substrate scope of compound 5 and the removal of AQ

Conclusions

In summary, we reported a synergistic palladium/enamine catalyzed asymmetric addition of ketone to non-activated alkene under mild conditions. Using this protocol, asymmetric α-alkylation of ketone derivatives were successfully achieved by combining the chiral enamine formation and directed Pd-catalyzed alkene activation, which offered an efficient and cooperative catalysis system. Furthermore, this study revealed a novel approach towards α-branched ketones derivatives, highlighting its valuable synthetic utility.

Experimental

General procedure to synthesize 3a-3n:

An oven-dried vial was charged with Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol%, 0.02 mmol), HOAc (1 equiv., 0.2 mmol), ketone (3 equiv., 0.6 mmol) and pyrrolidine (20 mol%, 0.04 mmol). The vial was placed under vacuum and charged with Ar. Alkene (1a) (1 equiv., 0.2 mmol), and toluene (1M, 0.2 mL) was added into the vial sequentially under Ar atmosphere. The reaction was run under 80 °C and monitored by TLC. Once the reaction completed, the solvent was removed under vacuum, and the resulting crude mixture was loaded on a silica gel column directly and purified by flash chromatography to give desired product.

General procedure to synthesize 4a-4l:

An oven-dried vial was charged with Pd(MeCN)2Cl2 (10 mol%, 0.02 mmol), HOAc (1 equiv., 0.2 mmol), ketone (4 equiv., 0.8 mmol) and A9 (30 mol%, 0.06 mmol). The vial was placed under vacuum and charged with Ar. Alkene (1a) (1 equiv., 0.2 mmol) was added into the vial sequentially under Ar atmosphere. The reaction was run under 60 °C and monitored by TLC. Once the reaction completed, the crude mixture was loaded on a silica gel column directly and purified by flash chromatography to give desired product.

General procedure to synthesize 5a-5c:

An oven-dried vial was charged with Pd(MeCN)2Cl2 (10 mol%, 0.02 mmol), HOAc (1 equiv., 0.2 mmol), ketone ester (3 equiv., 0.6 mmol) and A10 (30 mol %, 0.6 mmol). The vial was placed under vacuum and charged with Ar. Alkene (1a) (1 equiv., 0.2 mmol) was added into the vial sequentially under Ar atmosphere. The reaction was run under 60 °C and monitored by TLC. Once the reaction completed, the crude mixture was loaded on a silica gel column directly and purified by flash chromatography to give desired product.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the NSF (CHE-1665122), NIH (1R01GM120240– 01) and NSFC (21228204) for financial support.

Footnotes

Footnotes relating to the title and/or authors should appear here. Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare

Notes and references

- 1.For a collection of recent review:; (a) Park Y, Park J and Jun C, Acc. Chem. Res, 2008, 41, 222–234; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shao Z and H Zhang, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2009, 38, 2745–2755; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Du Z and Shao Z, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2013, 42, 1337–1378; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chen D, Han Z, Zhou X and Gong L, Acc. Chem. Res, 2014, 47, 2365–2377; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kim D, Park W and Jun C, Chem. Rev, 2017, 117, 8977–9015; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Zhong C and Shi X, Eur. J. Org. Chem, 2010, 16, 2999–3025; [Google Scholar]; (g) Allena AE and MacMillan DWC, Chem. Sci, 2012, 3, 633–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Afewerki S and Cordova A, Chem. Rev, 2016, 116, 13512–13570; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cheong PH-Y, Legault CY, Um JM, Çeleb-Ölçüm N and Houk KN, Chem. Rev, 2011, 111, 5042–5137; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Seayad J and List B, Org. Biomol. Chem, 2005, 3, 719–724; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ibrahem I, Ma G, Afewerki S and Cordova A, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2013, 52, 878–882; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhao G, Ullah F, Deiana L, Lin S, Zhang Q, Sun J, Ibrahem I, Dziedzic P and Cordova A, Chem. Eur. J, 2010, 16, 1585–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Ibrahem I and Cordova A, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2006, 45, 1952–1956; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vignola N and List B, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2004, 126, 450–451; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bihelovic F, Matovic R, Vulovic B and Saicic RN, Org. Lett, 2007, 9, 5063–5066; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Li M, Datta S, Barber DM and Dixon DJ, Org. Lett, 2012, 14, 6350–6353; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhou H, Wang Y, Zhang L, Cai M and Luo S, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2017, 139, 3631–3634; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Zhou X, Su Y, Wang P and Gong L, Acta. Chim. Sinica, 2018, 76, 857–861; [Google Scholar]; (g) Wang P, Lin H, Zhai Y, Han Z and Gong L, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2014, 53, 12218–12221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Zhao X, Liu D, Guo H, Liu Y and Zhang WJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2011, 133, 19354–19357; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cattopadhyay K, Recio A III and Tunge JA, Org. Biomol. Chem, 2012, 10, 6826–6829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Basavaiah D, Rao AJ and Satyanarayana T, Chem. Rev, 2003, 103, 811–892; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Furstner A, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2009, 39, 3012–3043; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zeni G and Larock RC, Chem. Rev, 2004, 104, 2285–2310; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Beccalli EM, Broggini G, Martinelli M and Sottocornola S, Chem. Rev, 2007, 107, 5318–5365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Chianese AR, Lee SJ and Gagne MR, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2007, 46, 4042–4059; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hahn C, Chem. Eur. J 2004, 10, 5888–5899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Kimura M, Horino Y, Mukai R, Tanaka S and Tamaru Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2001, 123, 10401–10402; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Braun M and Meier T, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2006, 45, 6952–6955; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hayashi T and Hegedus LS, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1977, 99, 7093–7094; [Google Scholar]; (d) Kende AS, Roth B and Sanfilippo PJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1982, 104, 1784–1785; [Google Scholar]; (e) Pei T and Widenhoefer RA, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2001, 123, 11290–11291; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Pei T, Wang X and Widenhoefer RA, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2003, 125, 648–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Yang KS, Gurak JA Jr., Liu Z and Engle KM, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2016, 138, 14705–14712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For nitrogen-containing nucleophiles, see:; (b) Gurak JA Jr., Yang KS, Liu Z and Engle KM, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2016, 138, 5805–5808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.For examples of enantioselective addition to unactivated alkene using AQ directing group strategy, see:; (a) Wang H, Bai Z, Jiao T, Deng Z, Tong H, He G, Peng Q and Chen G, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2018, 140, 3542–3546; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nimmagadda SK, Liu M, Karunananda MK, Gao D, Apolinar O, Chen JS, Liu P and Engle KM, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2019, 58, 3923–3927; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liu Z, Li X, Zeng T and Engle KM, ACS Catal, 2019, 9, 3260–3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen H, Zhang L, Chen S, Feng J, Zhang B, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Wu Y and Gong L, ACS Catal, 2019, 9, 791–797. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Allen AE and MacMillan DWC, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2010, 132, 4986–4987; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Allen AE and MacMillan DWC, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2011, 133, 4260–4263; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Brochu MP, Brown SP and MacMillan DWC, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2004, 126, 4108–4109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng Y and Chen G, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2010, 49, 958–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.