Abstract

Purpose

To assess the present evidence regarding the efficiency, safety, and potential risks of pharmacotherapy used for Parkinson’s disease psychosis (PDPsy) treatment.

Patients and methods

We searched the following databases: PubMed, the Cochrane Library, ISI Web of Science, and Embase using the following terms: atypical antipsychotics, pimavanserin, olanzapine, quetiapine, clozapine, Parkinson’s disease and psychosis. We systematically reviewed all randomized placebo-controlled trials comparing an atypical antipsychotic with a placebo.

Results

A total of 13 randomized placebo-controlled trials for a total 1142 cases were identified involving pimavanserin (n=4), clozapine (n=2), olanzapine (n=3), and quetiapine (n=4). For each atypical antipsychotic, a descriptive synthesis and meta-analyses was presented. Pimavanserin was associated with a significant improvement in psychotic symptoms compared to a placebo without worsening motor function. Clozapine was efficacious in alleviating psychotic symptoms and did not exacerbate motor function either. Quetiapine and Olanzapine did not demonstrate significant differences in reducing psychotic symptoms but may aggravate motor function.

Conclusions

There is strong evidence that pimavanserin is effective for the treatment of PDPsy. Clozapine is also recommended but should be used with caution due to its side effects. In the future, more well-designed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are needed to confirm and update the findings reported in this meta-analysis.

Keywords: clinical trials systematic review/meta-analysis, psychosis, Parkinson’s disease/Parkinsonism

Introduction

Since the first description of Parkinson’s disease (PD) by James Parkinson in 1817, this disease has gained global attention.1 Parkinson’s disease is known as a chronic and progressive neurodegenerative disorder, and is marked by motor dysfunction and non-motor symptoms including psychosis.2 So far, more than 10 million people worldwide are affected by Parkinson’s disease.3

Up to 60% of patients with Parkinson’s disease may ultimately develop Parkinson’s disease psychosis (PDPsy) and psychotic symptoms are common in drug treated patients with PD.4,5 There are no standardized diagnostic criteria for PDPsy, according to the report of a working group published in 2007.6 The symptoms of PDPsy have obvious characteristics including delusions and hallucinations.5 While the recognition of PDPsy is still a great challenge for clinicians,7 PDPsy has a huge impact on the quality of life and on caregiver burden. Since PDPsy disturbs the activities of daily living, the management of PDPsy is of great significance for maintaining the quality of life in PD patients and decreasing the burden of on the caregivers.8 Consequently, antipsychotics are often used for the treatment of PDPsy.

Treatment of PDPsy may be difficult due to the modest efficacy of antipsychotics and the risk of worsening motor function.9 There are several steps involved in the treatment of PDPsy. Reducing or eliminating dopaminergic drugs and other contributing medications is usually the first step but is always ineffective and is also accompanied with a worsened motor function.10 When the reduction of antiparkinsonian drugs does not improve the psychotic symptoms, antipsychotic medications should be considered.11 Recently, accessible antipsychotic drugs such as pimavanserin, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine have become of common use for the treatment of PDPsy. However, their use is often limited by the resulting adverse drug reactions. In the past years, several efforts have been made to improve the available treatment for PDPsy. Lutz et al12 suggested an orienting indication-specific therapeutic reference range of 15–141 ng/mL among PD patients with dopamimetic psychosis, which demonstrated that clozapine treatment for patients with dopamimetic psychosis in Parkinson’s disease seemed to be safe and calculable. However, therapeutic drug monitoring was also recommended due to its adverse effects such as sedation, hypotension, agranulocytosis, metabolic syndrome, hypersalivation, and myocarditis.

Even though three meta-analyses have been published comparing antipsychotics with placebo in the past 10 years, most were small series and presented conflicting results.13–15 In addition, the data extraction method in our study is different compared to previous studies. Therefore, we systemically searched and analyzed the available literature to evaluate the efficiency, safety, and potential advantages of antipsychotics versus placebo for PDPsy.

Methods

A prospective unpublished protocol of objectives, data searches, inclusion and exclusion criteria, outcomes of interest, and statistical methods was prepared a priori in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis recommendations for study reporting.16

Data search

A literature search was performed in May 2017 without any limitations in terms of regions, publication types, races, or languages. We searched the following electronic databases: PubMed, the Cochrane Library, ISI Web of Science, and Embase using the following combination of terms in the [Title/Abstract]: atypical antipsychotics, pimavanserin, olanzapine, quetiapine, clozapine, Parkinson’s disease, psychosis. We systematically reviewed all the randomized controlled trials comparing an antipsychotic with a placebo for the treatment of PDPsy. The Related Articles function was also used to reveal additional studies, and the computerized search was supplemented with manual searches of the reference lists of all relevant studies, unpublished experiments, review articles, and conference abstracts. When several reports describing the same population were published, the most recent or complete report was included.17

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All available randomized placebo-controlled trials comparing atypical antipsychotics with a placebo in all age groups were included. Studies were excluded if they belonged to one of the following groups: editorials, letters to the editor, review articles, case reports, experimental studies, and animal active comparator.

Data extraction and outcomes of interest

Data from the included studies were independently extracted by two reviewers (Zhang and Yang) and checked by a third reviewer (Wen). Any inconsistencies were reviewed and resolved by the adjudicating senior authors (Z Liu and Wang). We extracted from each study for the following: study design, antipsychotic, duration (weeks), age (mean ± SD), male%, number of participants, dosage, outcomes, discontinuation rates. The outcomes were the Assessment of Positive Symptoms - Hallucinations and Delusions scales (SAPS-H+D), The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) Part II (Activities of Daily Living) and Part III (Motor Examination), Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI), Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), Unified Parkinson’s disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), Mini Mental Test Examination (MMSE), Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).

Quality assessment and statistical analysis

The methodological quality of the randomized placebo-controlled trials was assessed by the Cochrane risk of bias tool.18 Randomization, treatment agents, the blindness in detail were demonstrated in accordance with the primary trials. All the meta-analyses were implemented using Review Manager 5.0 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). Basically, reviewers used weighted a mean difference (WMD) to compare the continuous outcomes. All outcomes were reported with a 95% confidence interval (CI). For studies that presented continuous outcomes such as means and range values, the standard deviations were calculated with the technique described by Hozo et al19 When standard deviations (SDs) were not mentioned in the articles, they were derived from other available data or the reviewers contacted the authors to gain the necessary statistics.20 When the meta-analyses of the continuous outcomes was conducted, we use the differences in the changes from the baseline (also called a change score) as the primary outcomes.21

The statistical heterogeneity among the studies was evaluated using a χ2 test with the significance set at p<0.10. Meanwhile, the heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic with I2>50% indicating high heterogeneity. If heterogeneity between the studies was noted, the random-effects model was used. Otherwise, the fixed-effects model was used.18 As for high quality studies, sensitivity analyses were performed. Funnel plots were used to screen for any evaluating potential publication bias.22

Results

Study characteristics

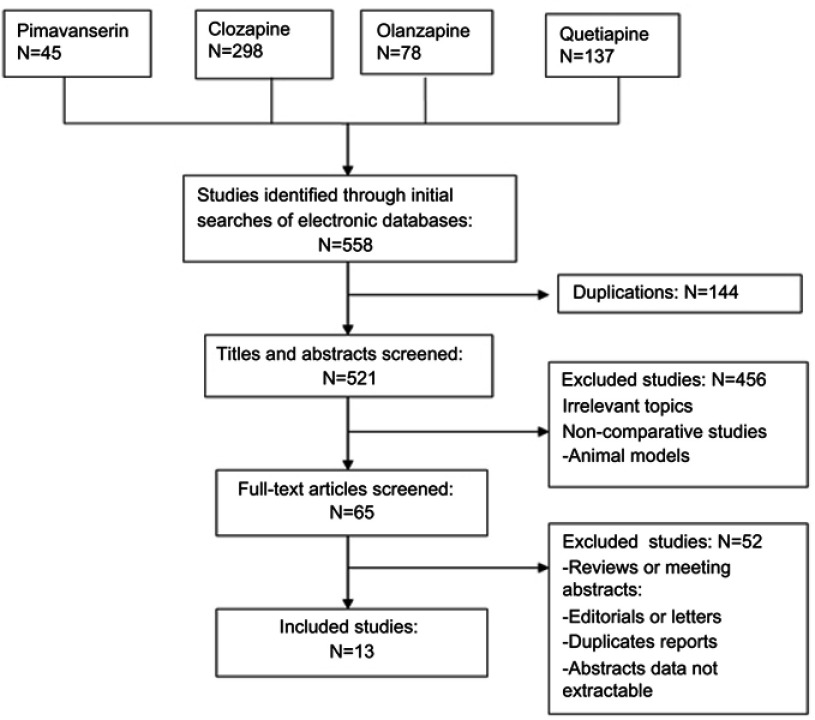

Thirteen randomized placebo-controlled trials including a total of 1142 cases fulfilled the predefined inclusion criteria and were included in Figure 1. Eleven publications were full-text articles,23–33 and two were unpublished trials.34,35 The agreement between the two reviewers was 92% for the study selection and 85% for the quality assessment of the trials.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of studies identified, included, excluded.

The characteristics of the included studies are outlined in Table 1. Four trials compared pimavanserin23,25 and quetiapine26–29 intervention with a placebo. The number of trials comparing clozapine30,33 and olanzapine24,31,32 versus a placebo were, respectively, two and three.

Table 1.

Characteristics of randomized placebo-controlled trials included in the meta-analysis

| Study | Level of evidence design | Antipsychotic | Duration (weeks) | Age (mean ± SD) & male% | Total | Dose | Outcomes | Discontinuation rates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

NCT00477672 200935 (United States, India, Europe) |

Randomised Double-blind Placebo-controlled |

Pim | 6 | 69.3±8.71 & 63.7% | 298 200 101 99 98 |

Intervention: 1.Pimavanserin tartrate (ACP-103) 10 mg, tablet, once daily by mouth 2. Pimavanserin tartrate (ACP-103) 40 mg, tablet, once daily by mouth Control: Placebo tablet, once daily by mouth, |

Antipsychotic efficacy: SAPS-H+D Motor symptoms: UPDRS Part II and Part III |

Pim: 16% Pla: 7.1% |

|

NCT00658567 200934 (United States. Europe) |

Randomised Double-blind Placebo-controlled |

Pim | 6 | 72.0±7.82 & 63.6% | 123 83 42 41 40 |

Intervention: 1.Pimavanserin tartrate (ACP-103) 10 mg, tablet, once daily by mouth 2. Pimavanserin tartrate (ACP-103) 20 mg, tablet, once daily by mouth Control: Placebo tablet, once daily by mouth |

Antipsychotic efficacy: SAPS-H+D Motor symptoms: UPDRS Part II and Part III |

Pim: 12% Pla: 20% |

| Meltzer et al 201025 | Randomised Double-blind Placebo-controlled |

Pim | 4 | 70.9±1.12 & 76.7% | 60 29 31 |

Intervention: Pimavanserin 20 mg (day 1) with possible increases to 40- or 60-mg daily doses on days 8 and 15 Control: Placebo tablet, once daily by mouth |

Antipsychotic efficacy: SAPS-H+D Motor symptoms: UPDRS Part II and Part III |

Pim: 31% Pla: 22% |

| Cummings et al 201423 | Randomised Double-blind Placebo-controlled |

Pim | 6 | 72.7±7.25 & 63.3% | 199 105 94 |

Intervention: Pimavanserin 40 mg, tablet, once daily by mouth Control: Placebo tablet, once daily by mouth |

Antipsychotic efficacy: SAPS-H+D Motor symptoms: UPDRS Part II and Part III |

Pim: 15% Pla: 7.4% |

| Pollak et al 200430 | Randomised Double-blind Placebo-controlled |

Clo | 4 | Clo:71.2±7.4 Pla: 72.8±8.2 & 53.3% |

60 32 28 |

Intervention: Clozapine 6.25 mg orally daily, titrated to maximum 50-mg daily dose Control: Placebo tablet, once daily by mouth |

Efficacy outcomes: CGI Positive PANSS Safety outcomes: UPDRS MMSE |

Clo: 0% Pla: 3.5% |

| The Parkinson Study Group 199933 | Randomised Double-blind Placebo-controlled |

Clo | 4 | Clo:70.8±8.6 Pla: 71.9±8.1 & 56.6% |

60 30 30 |

Intervention: Clozapine 6.25 mg orally daily, titrated to maximum 50-mg daily dose Control: Placebo tablet, once daily by mouth |

CGI BPRS UPDRS MMSE |

Clo: 0% Pla: 0% |

| Breier et al 2002 (USA)32 | Randomised Double-blind Placebo-controlled |

Ola | 4 | Ola:73.5±8.7 Pla: 71.7±6.8 & 69.9% |

83 41 42 |

Intervention: Olanzapine 2.5 mg orally daily, titrated to maximum 15 mg daily dose Control: Placebo tablet, once daily by mouth |

CGI BPRS UPDRS MMSE |

0% |

| Breier et al 2002 (Europe)32 | Randomised Double-blind Placebo-controlled |

Ola | 4 | Ola:70.9±6.3 Pla: 70.5±8.2 & 66.2% |

77 4928 |

Intervention: Olanzapine 2.5 mg orally daily, titrated to maximum 15 mg daily dose Control: Placebo tablet, once daily by mouth |

CGI BPRS UPDRS MMSE |

0% |

| Ondo et al 200231 | Randomised Double-blind Placebo-controlled |

Ola | 9 | 71.0±7.1 & 63.3% | 30 16 11 |

Intervention: Olanzapine 2.5–10 mg orally daily, Control: Placebo tablet, once daily by mouth |

UPDRS item 2 (thought disorder) MMSE |

13.3% |

| Nichols et al 201324 | Randomised Double-blind Placebo-controlled |

Ola | 4 | Ola(2.5):70.7±8.1 Ola(5):72.4±4.8 Pla: 71.3±6.5 |

23 14 6 8 9 |

Intervention: 1. Olanzapine 2.5 mg, tablet, once daily by mouth at bedtime 2. Olanzapine 5 mg, tablet, once daily by mouth at bedtime Control: Placebo tablet, once daily by mouth |

BPRS CGI |

Ola(2.5):66% Ola(5):38% Pla: 22% |

| Ondo et al 200529 | Randomised Double-blind Placebo-controlled |

Que | 12 | Que:74.0±7.0 Pla: 71.0±5.0 & 54.84% |

31 21 10 |

Intervention: Quetiapine 50 mg orally twice daily for 3 weeks, titrated up to 100 mg orally twice daily over another 3 weeks Control: Placebo tablet, twice daily by mouth |

BPRS Question 12 (BPRS) UPDRS |

Que:19% Pla:20% |

| Rabey et al 200728 | Randomised Double-blind Placebo-controlled |

Que | 12 | Que:75.5±8.1 Pla: 74.5±8.7 & 56.89% |

58 30 28 |

Intervention: Quetiapine 12.5 mg orally at bedtime, titrated to until symptoms cleared or side effects limited treatment Control: Placebo tablet, once daily by mouth |

BPRS UPDRS CGI |

Que:50% Pla:35.7% |

| Shotbolt et al 200926 | Randomised Double-blind Placebo-controlled |

Que | 12 | Que: 74.0±8.0 Pla:7 0.0±8.0 & 66.67% |

24 11 13 |

Intervention: Quetiapine 25 mg for week 1, 25 mg twice for week 2,50 mg twice for week 3, with an optional further increase to 50 mg am, 100 mg nocte if clinically indicated Control: Placebo tablet, daily by mouth |

BPRS UPDRS |

0% |

| Fernandez et al 200927 | Randomised Double-blind Placebo-controlled |

Que | 8 | Que: 64.6±8.0 Pla:71.5±7.46 & 66.67% |

16 8 8 |

Intervention: Olanzapine 25–150 mg orally daily, Control: Placebo tablet, daily by mouth |

BPRS CGI UPDRS |

Que:50% Pla:12.5% |

Abbreviations: Pim, Pimavanserin; Pla, Placebo; Clo, clozapine; Ola, Olanzapine; Que, Quetiapine; CGI, clinical global impression scale; PANSS, positive and negative syndrome scale; UPDRS, unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale; MMSE, mini mental test examination; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ;SAPS-H+D, the Assessment of Positive Symptoms - Hallucinations and Delusions scales; UPDRS Part II, the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Activities of Daily Living; UPDRS Part III,the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Motor Examination.

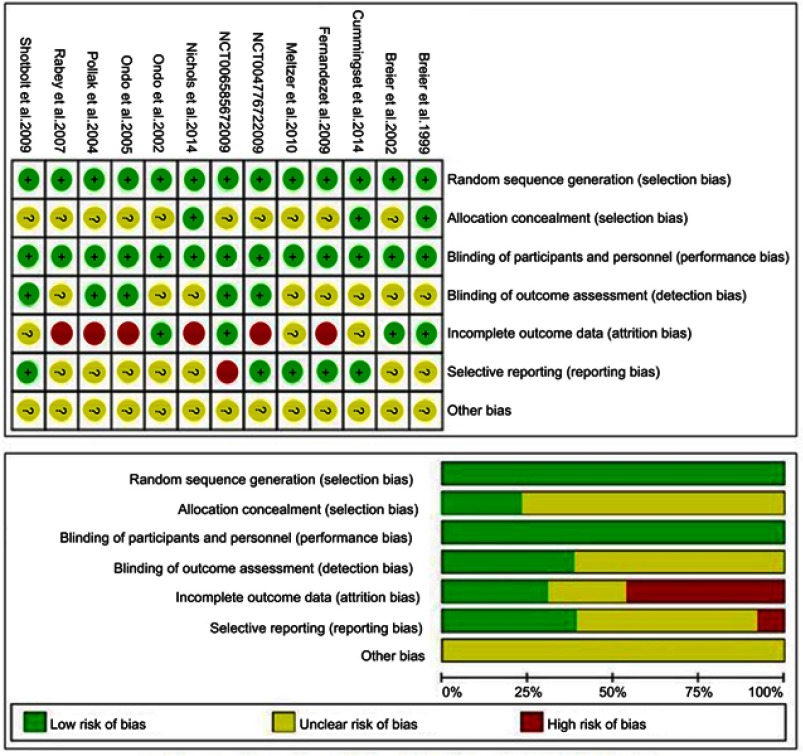

Methodological quality of the included studies

The summary of the risk of bias of each individual study is presented in Figure 2. The quality of the included studies was generally moderate-to-high on the GRADE assessment. True randomization and double blinding were used in all of the trials. Only two studies provided information about the allocation concealment. For the method used for the handling of missing data and the intention-to-treat analyses were not clearly mentioned in some studies.

Figure 2.

Summary of risk of bias for each individual trial. “?”: unclear risk of bias; “+”: low risk of bias; “−”: high risk of bias.

Main findings

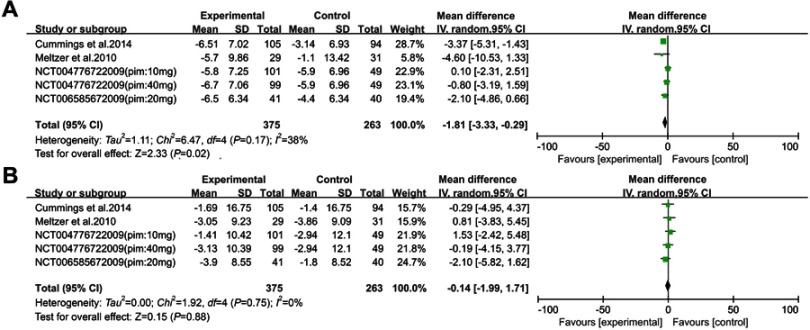

Pimavanserin

Two studies23,25 and two unpublished experiments34,35 assessing pimavanserin (including 417 drug-treated and 263 placebo-treated PDPsy patients) (Figure 3) et he inclusion criteria. In one study,35 the researchers divided the patients into two experimental groups (pimavanserin 10 mg and pimavanserin 40 mg). Hence, we regarded this trial as two independent studies and the number of the studies divided was half of the initial study. Pimavanserin decreased the SAPS-H+D scores compared to placebo [WMD =−1.81, 95% CI: −3.33 to −0.29, p=0.020, I2=38%, N=5]. Moreover, pimavanserin was superior to a placebo in reducing the SAPS-H (WMD =−2.08, 95% CI: −3.31 to −0.85, p<0.001, I2=0%, N=2) and SAPS-D scores (WMD =−1.28, 95% CI: −2.24 to −0.31, p=0.010, I2=0%, N=2). There were no significant differences in the UPDRS-II+III scores (WMD =−0.14, 95% CI: −1.99 to 1.71, p=0.88, I2=0%, N=5) between pimavanserin and the placebo groups.

Figure 3.

Forest plot and meta-analysis of pimavanserin in SAPS H+D (A), UPDRS-II+III (B).

Additionally, as pimavanserin prolongs the QT interval, the use of pimavanserin should be avoided in patients with a known QT prolongation or in combination with other drugs known to prolong the QT interval. Pimavanserin should also be avoided in patients with a history of cardiac arrhythmias, as well as other circumstances resulting in similar outcomes. Besides, elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis using antipsychotic drugs are also at an increased risk of death.36

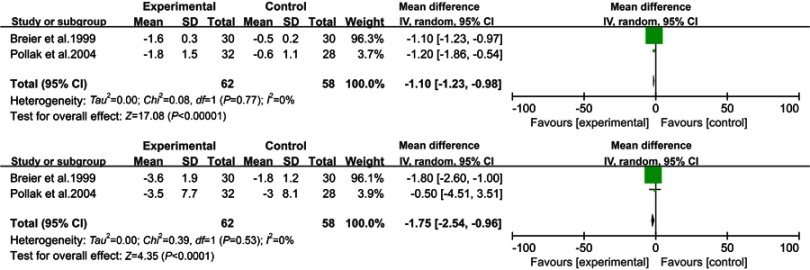

Clozapine

Two studies30,33 reporting the effects of clozapine versus a placebo (Figure 4) and involving 130 patients were included in the review. Clozapine was associated with significant differences in the rates of CGI (WMD =−1.10, 95% CI: −1.23 to −0.98, p<0.001, I2=0%, N=2) and UPDRS Motor (WMD =−1.75, 95% CI: −2.54 to −0.96, p<0.001, I2=0%, N=2).On the other hand, the results of the UPDRS (WMD =−1.79, 95% CI: −4.57 to 1.00, p=0.21, I2=43%, N=2) and MMSE (WMD =0.11, 95% CI: −0.12 to 0.33, p=0.36, I2=0%, N=2) showed no significant differences between the clozapine group and placebo.

Figure 4.

Forest plot and meta-analysis of clozapine in CGI (A), UPDRS Motor (B).

Based on the three trials included in this study, the adverse effects of clozapine include sedation, hypotension, agranulocytosis and metabolic syndrome.

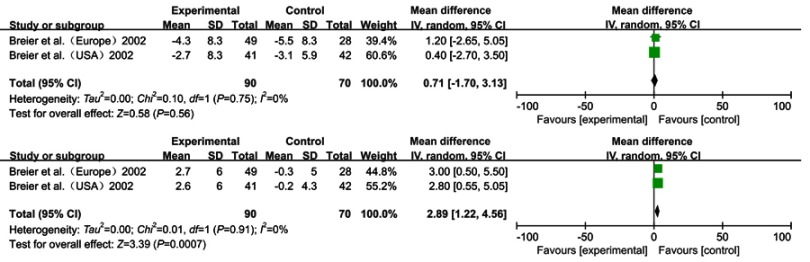

Olanzapine

Although three studies24,31,32 met the inclusion criteria, we only extracted and summarized the data from two trials in one study32 because of the non-standardized assessment scales and the incomplete outcome data of the third study (Figure 5). Breier32 studied the effects of olanzapine versus a placebo. One study was performed in the United States, while the one in Europe. Therefore, we considered those studies as two separate studies. The study reported the UPDRS, UPDRS ADL and UPDRS Motor for the 160 included patients, in which olanzapine demonstrated some differences compared to the placebo (respectively, WMD =5.81, 95% CI: 2.85 to 8.76, p<0.001, I2=0%, N=2; WMD =2.92, 95% CI: 1.53 to 4.31, p<0.001, I2=0%, N=2; WMD =2.89, 95% CI: 1.22 to 4.56, p<0.001, I2=0%, N=2). There were no significant differences in BPRS and MMSE (WMD =0.71, 95% CI: −0.17 to 3.13, p=0.56, I2=0%, N=2; WMD =−0.78, 95% CI: −1.77 to 0.20, p=0.12, I2=0%, N=2).

Figure 5.

Forest plot and meta-analysis of olzapine in BPRS (A), UPDRS Motor (B).

According to this study, analysis of the adverse events showed rather different outcomes between the two studies. In the United States, the patients in the olanzapine group showed significantly higher reported incidences of extrapyramidal syndrome (especially bradykinesia), hallucinations and increased salivation. However, in the European study, there was no significant difference between olanzapine and placebo.

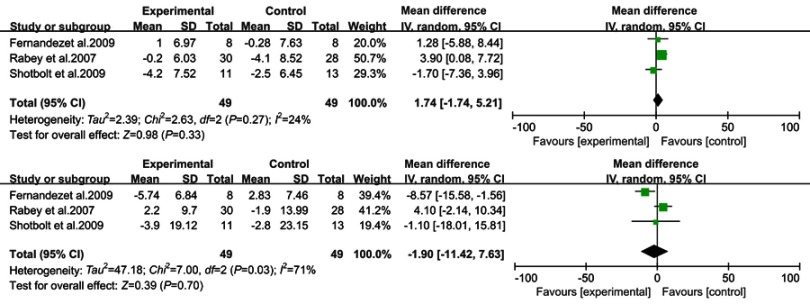

Quetiapine

Data from the Fernandez,27 Rabey28 and Shotbolt26 trials were combined in a meta-analysis (Figure 6). Based on the present meta-analysis quetiapine did not appear to significantly improve the psychotic symptoms in PDPsy. There were no significant differences in BPRS (WMD =1.74, 95% CI: −1.74 to 5.21, p=0.33, I2=24%, N=3) and UPDRS (WMD =−1.90, 95% CI: −11.42 to 7.63, p=0.70, I2=0%, N=3).

Figure 6.

Forest plot and meta-analysis of quetiapine in BPRS (A), UPDRS (B).

Based on our data and the warning of increased risk death in elderly patients with dementia, the use of quetiapine is of great concern.

Risk of bias across studies

According to the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions,18 a funnel plot assessing the possibility of a publication bias may not have enough power to identify the chances of real asymmetry occurring if the number of trials in a systematic review is less than ten.37 Thus, a funnel plot was not included in this meta-analysis because each analysis included no more than ten studies.

Discussion

This is an up-to-date systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the pharmacotherapy used for PDPsy, which included the largest number of randomized placebo-controlled trials. This meta-analysis of 13 randomized placebo-controlled studies for a total of 1142 cases, compared the efficacy and safety of atypical antipsychotics versus placebo. Besides, we used data that were different from those obtained at baseline,21 which was the biggest difference compared to previous studies.13

Even though three meta-analyses comparing antipsychotics with a placebo have been published in the past 10 years, most were small studies size with conflicting results. One study demonstrated that clozapine showed superiority over a placebo in reducing psychotic symptoms, while quetiapine and olanzapine did not significantly improve the psychotic symptoms. Further, all three antipsychotics may exacerbate the motor symptoms.13 In contrast, in another study, clozapine showed a significantly better outcome versus placebo regarding efficacy and motor function, while quetiapine failed to show efficacy. The olanzapine also failed to improve psychotic symptoms and significantly caused more extra pyramidal side effects.

Pimavanserin

Pimavanserin is a 5-HT2A receptor inverse agonist, which has been approved by US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2016 as a novel treatment for patients with the hallucinations and delusions associated with PDPsy.4,38 The 5-HT 2A receptors are constitutively active. Inverse agonists may inhibit the 5-HT2A receptors more effectively than antagonists. It is well known that pimavanserin is a selective 5-HT2A antagonist. Thus, pimavanserin has the highest affinity for 5-HT2A receptors and has a lower affinity for the 5-HT2C receptor, inappreciable binding at dopamine D2 or histamine receptors, which may predict the greater efficacy without motor or sedative side-effects.39

In this study, efficiency was measured by the SAPS hallucination and delusion items, while motor function was assessed by the UPDRS-II+III scores. Pimavanserin significantly reduced the SAPS-H+D scores versus a placebo. Similarly, a reduction in the SAPS-H scores and SAPS-D scores was also observed. No difference in UPDRS-II+III scores was found, and no impairment in motor function was reported. Moreover, since PDPsy has a considerable impact on both patients and care givers, the group taking pimavanserin demonstrated a reduction in a caregiver’s burden and an improvement in the participants’ nighttime sleeping and wakefulness.40

The heterogeneity of these scales was non-significant between the pimavanserin group and the placebo. Although these four studies noted some adverse events such as somnolence, peripheral edema, urinary tract infection, falls, confusion, headache, and hallucinations, there was no significant difference between the two arms. According to the results, we found that pimavanserin may be adequate for use as a first-line treatment for PDPsy because it improves the psychotic symptoms without worsening motor function, which was in accordance with the conclusions and guidelines reported previously.10,15,41 Additionally pimavanserin provided robust proof for clinically significant efficacy. However, further studies are needed to compare pimavanserin with other atypical antipsychotics in larger population. Further, longer studies with different populations are needed, because all of the randomized placebo-controlled trials involving pimavanserin were funded by the manufacturer of the drug and the trials were conducted in very specific patient populations.42

Clozapine

Clozapine was primarily considered as the first treatment for the management of PDPsy and was given a level B recommendation by The American Academy of Neurology (AAN), stating that it should be considered but the side effects must be monitored closely.43,44 Moreover, clozapine has been registered in the Netherlands for its effectiveness in treating PDPsy.42 In our meta-analysis, data from two clozapine versus placebo trials were combined using the CGI, MMSE, UPDRSM and UPDRSM-Motor to measure the efficacy and safety. Clozapine significantly reduced the CGI scores and the UPDRSM-Motor scores but the UPDRSM scores remained similar between the two groups.

The heterogeneity of these scales was 0% between the two studies included, which was statistically significant. Notably, the adverse events cannot be ignored. Severe agranulocytosis and mild leukopenia were observed in patients receiving clozapine, which resulted in frequent blood monitoring.33 Consequently, this therapy can be burdensome and may add logistical challenges to the patients and caregivers. The drop-out rate was low in the two trials.

Based on the results of this meta-analysis, clozapine improved the psychotic symptoms without worsening the motor function. As clozapine has been used for a long period of time, the majority of clinicians and psychiatrists have extensive experience with this drug. In addition, from a safety and economic perspective, clozapine patients should be closely monitored over a long period of time. This requirement can be burdensome on the patients and caregivers due to its fatal side effects.

Quetiapine and olanzapine

Quetiapine and olanzapine did not appear superiority to the placebo in improving the psychotic symptoms. However, quetiapine has less of an impact on the motor symptoms while olanzapine may exacerbate the motor symptoms according to the result of the analysis. Moreover, the overall mean difference for the two studies included crossed the null value. Consequently, any reduction in BPRS and MMSE did not indicate statistically significant results.

The heterogeneity of these scales was 0% in the quetiapine group, while the heterogeneity was, respectively, 74% and 24% in the UPDRS scores and the BPRS scores in the olanzapine group. Mild adverse effects such as somnolence, dizziness, headache, weight gain, and orthostasis were more common in quetiapine groups.22,45 Regardless of the conflicting data from the clinical trials showing that quetiapine is effective in addressing PDPsy, quetiapine is currently the most widely prescribed medication in the United States for the treatment of PDPsy.10,26–29 Therefore, quetiapine and olanzapine should not be considered as first-line agents due to their side effects. AAN gave quetiapine a level C recommendation.43 The AAN and EFNS/MDS-ES do not recommend the use of olanzapine for the treatment of PDPsy.

Study limitations

The present systematic review and meta-analysis has the following limitations that must be taken into consideration. Above all, the main limitation is that although all the included studies were randomized placebo-controlled trials, the sample size was small. Besides, inadequate blinding and random sequence generation tend to increase the risk of bias. In addition, all studies included into the analyses had relatively short times to follow-up, between 4 and 12 weeks which may influence the final outcomes. Meanwhile, the rating scales used in the studies were different, hence the comparability is limited. Therefore, randomized placebo-controlled trials with longer durations, larger sample sizes, and more specific patient populations are warranted in the near future.

Conclusion

PDPsy is frequent, burdensome, and distressing in patients with PD, which also posing a major challenge to the clinical management due to lack of effective therapies.23 This meta-analysis indicated that pimavanserin is effective in the treatment of PDPsy. Clozapine is also recommended but should be used with caution due to its side effects. Quetiapine and olanzapine should not be considered as first-line medications for PDPsy. Nevertheless, despite our precise methodology, intrinsic defects such as small size and incomplete data limited us from reaching definitive conclusions. In addition, PDPsy has significant impact on the quality of life of both patients and their family and therefore researches studying the burden caused by the disease are needed. Finally, looking to the future, more well-designed RCTs having the potential to enhance our knowledge of PDPsy are needed to confirm and re-update the findings of this analysis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Zhuoyuan Zhong and Xinxiang Fan for their advice and suggestions. This study was supported by the Guangdong Province Natural Science Foundation (2016A030313319 and 2017A030313490); The Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (2016B010125001) and Guangzhou City (201510010030); Grant [2013]163 from the Key Laboratory of Malignant Tumor Molecular Mechanism and Translational Medicine of Guangzhou Bureau of Science and Information Technology; and Grant KLB09001 from the Key Laboratory of Malignant Tumor Gene Regulation and Target Therapy of Guangdong Higher Education Institutes.

Abbreviation list

AAN, The American Academy of Neurology; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; PDPsy, Parkinson’s disease psychosis; RCTs, Randomized controlled trials; PD, Parkinson’s disease; WMD, Weighted mean difference; CI, Confidence interval; SD, Standard deviation; Pim, Pimavanserin; Pla, Placebo; Clo, clozapine; Ola, Olanzapine; Que, Quetiapine; CGI, clinical global impression scale; PANSS, positive and negative syndrome scale; UPDRS, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale; UPDRSM, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Motor; MMSE, mini mental test examination; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; SAPS-H+D, the Assessment of Positive Symptoms - Hallucinations and Delusions scales; UPDRS Part II, the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Activities of Daily Living; UPDRS Part III, the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Motor Examination.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Palacios-Sanchez L, Torres Nupan M, Botero-Meneses JS. James Parkinson and his essay on “shaking palsy”, two hundred years later. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2017;75:671–672. doi: 10.1590/0004-282X20170108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Lau LML, Breteler MMB. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:525–535. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70471-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorsey ER, Constantinescu R, Thompson JP, et al. Projected number of people with Parkinson disease in the most populous nations, 2005 through 2030. Neurology. 2007;68:384–386. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247740.47667.03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markham A. Pimavanserin: first global approval. Drugs. 2016;76:1053–1057. doi: 10.1007/s40265-016-0597-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman JH. Parkinson disease psychosis: update. Behav Neurol. 2013;27:469–477. doi: 10.3233/BEN-129016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ravina B, Marder K, Fernandez HH, et al. Diagnostic criteria for psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: report of an NINDS, NIMH work group. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1061–1068. doi: 10.1002/mds.21382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruz MP. Pimavanserin (Nuplazid): a treatment for hallucinations and delusions associated with Parkinson’s disease. P T. 2017;42:368–371. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hermanowicz N, Edwards K. Parkinson’s disease psychosis: symptoms, management, and economic burden. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21:s199–s206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldman JG, Vaughan CL, Goetz CG. An update expert opinion on management and research strategies in Parkinson’s disease psychosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:2009–2024. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2011.587122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hermanowicz N, Alva G, Pagan F, et al. The emerging role of pimavanserin in the management of Parkinson’s disease psychosis. J Managed Care Specialty Pharm. 2017;23:S2–S8. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.6-b.s2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Divac N, Stojanovic R, Savic Vujovic K. The efficacy and safety of antipsychotic medications in the treatment of psychosis in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Behav Neurol. 2016;2016:4938154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lutz UC, Sirfy A, Wiatr G, et al. Clozapine serum concentrations in dopamimetic psychosis in Parkinson’s disease and related disorders. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70:1471–1476. doi: 10.1007/s00228-014-1772-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jethwa KD, Onalaja OA. Antipsychotics for the management of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. B J Psych Open. 2015;1:27–33. doi: 10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.000927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frieling H, Hillemacher T, Ziegenbein M, Neundorfer B, Bleich S. Treating dopamimetic psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: structured review and meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;17:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yasue I, Matsunaga S, Kishi T, Fujita K, Iwata N. Serotonin 2A receptor inverse agonist as a treatment for Parkinson’s disease psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of serotonin 2A receptor negative modulators. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016;50:733–740. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan X, Lin T, Xu K, et al. Laparoendoscopic single-site nephrectomy compared with conventional laparoscopic nephrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Eur Urol. 2012;62:601–612. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sterne JAC, Egger M, Moher D. [homepage on the Internet]. Addressing reporting biases In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. New York: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2009. (Updated March 2011). Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. Accessed October 23, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiebe N, Vandermeer B, Platt RW, Klassen TP, Moher D, Barrowman NJ. A systematic review identifies a lack of standardization in methods for handling missing variance data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:342–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Da Costa BR, Nuesch E, Rutjes AW, et al. Combining follow-up and change data is valid in meta-analyses of continuous outcomes: a meta-epidemiological study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:847–855. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuan M, Sperry L, Malhado-Chang N, et al. Atypical antipsychotic therapy in Parkinson’s disease psychosis: a retrospective study. Brain Behav. 2017;7:e00639. doi: 10.1002/brb3.639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cummings J, Isaacson S, Mills R, et al. Pimavanserin for patients with Parkinson’s disease psychosis: a randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:533–540. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62106-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nichols MJ, Hartlein JM, Eicken MG, Racette BA, Black KJ. A fixed-dose randomized controlled trial of olanzapine for psychosis in Parkinson disease. F1000 Res. 2013;2:150. doi: 10.12688/f1000research [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meltzer HY, Mills R, Revell S, et al. Pimavanserin, a serotonin(2A) receptor inverse agonist, for the treatment of parkinson’s disease psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:881–892. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shotbolt P, Samuel M, Fox C, David AS. A randomized controlled trial of quetiapine for psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:327–332. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s5335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandez HH, Okun MS, Rodriguez RL, et al. Quetiapine improves visual hallucinations in Parkinson disease but not through normalization of sleep architecture: results from a double-blind clinical-polysomnography study. Int J Neurosci. 2009;119:2196–2205. doi: 10.3109/00207450903222758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rabey JM, Prokhorov T, Miniovitz A, Dobronevsky E, Klein C. Effect of quetiapine in psychotic Parkinson’s disease patients: a double-blind labeled study of 3 months’ duration. Mov Disord. 2007;22:313–318. doi: 10.1002/mds.21116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ondo WG, Tintner R, Voung KD, Lai D, Ringholz G. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, unforced titration parallel trial of quetiapine for dopaminergic-induced hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2005;20:958–963. doi: 10.1002/mds.20474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pollak P, Tison F, Rascol O, et al. Clozapine in drug induced psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, placebo controlled study with open follow up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:689–695. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.029868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ondo WG, Levy JK, Vuong KD, Hunter C, Jankovic J. Olanzapine treatment for dopaminergic-induced hallucinations. Mov Disord. 2002;17:1031–1035. doi: 10.1002/mds.10217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breier A, Sutton VK, Feldman PD, et al. Olanzapine in the treatment of dopamimetic-induced psychosis in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:438–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parkinson Study G. Low-dose clozapine for the treatment of drug-induced psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:757–763. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903113401003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.NCT00658567. A study of safety and efficacy of pimavanserin (ACP-103) in patients with Parkinson’s disease psychosis; 2009. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00658567.Accessed July 10, 2019.

- 35.NCT00477672. A study of the safety and efficacy of pimavanserin (acp-103) in patients with Parkinson’s disease phychosis; 2009. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00477672. Accessed July 10, 2019.

- 36.Acadia Pharmaceuticals Inc. Prescribing Information for NuplazidTM (Pimavanserin) Tablets, for Oral Use; 2016. Available from: http://www.acadia-pharm.com/product/. Accessed 10 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maneeton B, Putthisri S, Maneeton N, et al. Quetiapine monotherapy versus placebo in the treatment of children and adolescents with bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:1023–1032. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S121517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathis MV, Muoio BM, Andreason P, et al. The US Food and Drug Administration’s Perspective on the New Antipsychotic Pimavanserin. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16r11119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fox SH. Pimavanserin as treatment for Parkinson’s disease psychosis. Lancet. 2014;383:494–496. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62157-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cummingsa J, Millsc R, Williamsc H, Chi-Burrisc K, Dhalld R, Ballarde C. Antipsychotic efficacy and motor tolerability in a phase III placebo-controlled study of pimavanserin in patients with Parkinson’s Disease psychosis (Acp-103-020). J Neurol Sci. 2013;333(Supplement 1):119–e120. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.07.401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Combs BL, Cox AG. Update on the treatment of Parkinson’s disease psychosis: role of pimavanserin. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:737–744. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S108948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duits JH, Ongering MS, Martens HJM, Schulte PFJ. [Pimavanserin: a new treatment for the Parkinson’s disease psychosis]. Tijdschr Psychiatr. 2017;59:528–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyasaki JM, Shannon K, Voon V, et al. Practice Parameter: evaluation and treatment of depression, psychosis, and dementia in Parkinson disease (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2006;66:996–1002. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000215428.46057.3d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bozymski KM, Lowe DK, Pasternak KM, Gatesman TL, Crouse EL. Pimavanserin: a novel antipsychotic for Parkinson’s Disease psychosis. Ann Pharmacother. 2017;51:479–487. doi: 10.1177/1060028017693029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldman JG, Holden S. Treatment of psychosis and dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2014;16:281. doi: 10.1007/s11940-013-0281-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]