To the Editor:

Recently, a novel syndrome of combined immunodeficiency, allergy, and “auto”inflammation caused by mutations in the ARPC1B gene has been reported.1–4 Analysis of patient-derived hematopoietic cells has shown a defect in actin polymerization, which resulted in a wide range of clinical manifestations and immunologic-hematologic features. We report on the immunologic, cellular, and molecular phenotypes in 14 patients with biallelic ARPC1B mutations and variable clinical presentations (Fig 1, A and B; see Fig E1, A, and Table E1 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org; for case descriptions, see this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org), helping to delineate the broad spectrum of this novel disease and presenting unreported insights into cell-intrinsic defects involving regulatory T (Treg) cells and natural killer (NK) cells, potential players in the immune dysregulation and susceptibility to viral infections observed in these patients. The disease-causing variants are diverse and scattered throughout the gene (Fig E1, B; Table E1). Patient (P) 4, P12, and P14 have Nepalese ancestry and share the same variant, suggesting a founder mutation. In all patient samples tested, ARPC1B protein was undetectable by Western blotting and we identified an increased—although variable—expression of the ARPC1A isoform (see Fig E2 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org).

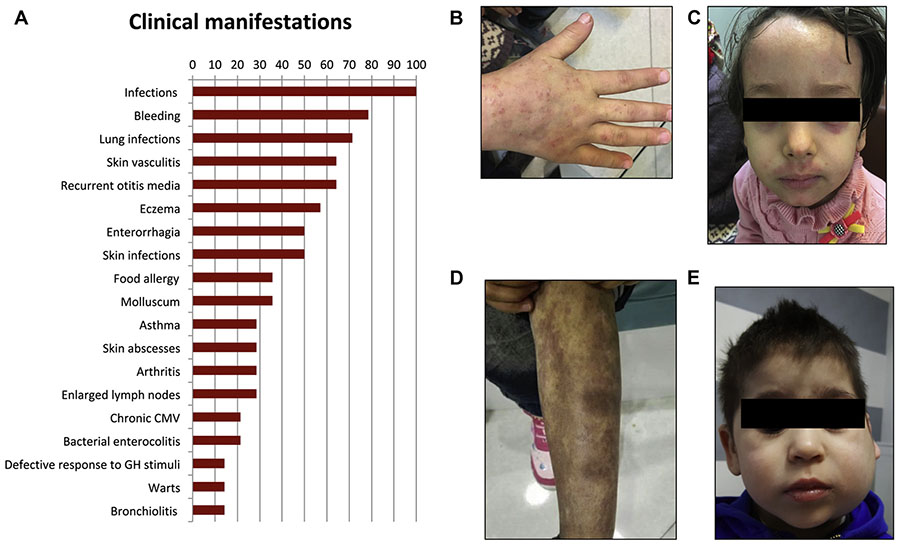

FIG 1.

Clinical features, imaging, and histology of relevant tissues in affected patients. A, Frequencies of clinical manifestations in ARPC1B-deficient patients (detailed in Table E8). B-D, Diffuse warts, eczema, and skin vasculitis in P7. E, Sialadenitis and lymph node enlargement in P3. CMV, cytomegalovirus; GH, growth hormone.

The disease is characterized by a very early clinical onset (mean, 2 months; range, 1–6 months) (see Table E2 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Presenting symptoms included skin rash, infections, and gastrointestinal bleeding. Most patients (79%) (Fig 1, A) suffered from recurrent or severe bleeding episodes, most frequently represented by enterorrhagia. Platelet counts were reduced (see Table E3 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org), with normal volume in most cases. An increased rate and/or abnormal severity of respiratory tract infections (including pneumonia, bronchopneumonia, and bronchiolitis), and skin infections (including abscesses, erysipelas, extensive warts [Fig 1, B], and molluscum contagiosum), were observed in 71% and 50% of the patients, respectively, whereas severe, protracted bacterial gastrointestinal infections have been diagnosed in a minority of individuals (see Tables E2 and E4 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org).

As summarized in Fig 1, A, and Table E5 (in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org), common manifestations of immune dysregulation included moderate-to-severe eczema, which was observed in 57% of cases (Fig 1, C), associated with food allergy (anaphylactic reactions) and asthma. Cutaneous vasculitis was noted in 69% of patients, presenting as a maculopapular rash, erythema nodosum, or vasculitic purpura (Fig 1, D). In all cases investigated with a skin biopsy, leukocytoclastic vasculitis was diagnosed. Arthritis was present in 23% of patients. One child presented with 23 episodes of macrophage activation syndrome, followed by the appearance of enlarged lymph nodes, splenomegaly, and episodes of sialadenitis (Fig 1, E). Autoantibodies were absent in most patients. Growth failure was noted in all patients (Table E2), with growth hormone tests found to be impaired when performed (P2 and P3), compatible with a partial growth hormone deficiency, and no catch-up growth after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) (P2, P3, and P6).

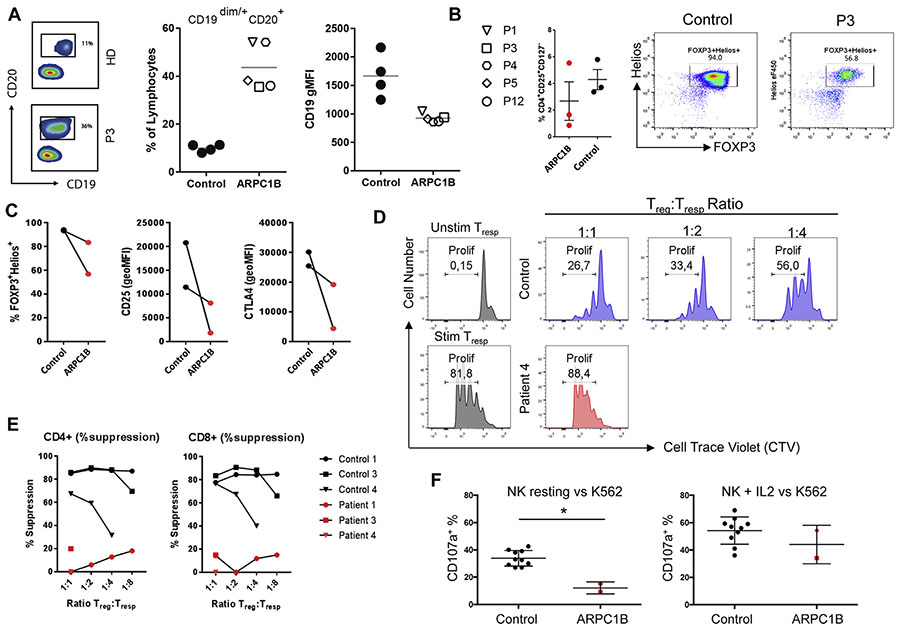

Immunophenotyping showed an increased number of circulating CD19+ B cells, a reduced absolute count of CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ T cells, and in 1 patient an expansion of γδ T cells, possibly driven by cytomegalovirus infection (Fig 2, A; see Table E6 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). In vivo immunoglobulin levels were abnormal, with markedly increased IgA and IgE in almost all cases (Table E6). In contrast to Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome or DOCK8 deficiency,5 the humoral response to polysaccharide vaccine was normal in most cases (see Table E7 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). The T-cell subset distribution was abnormal, with low percentages of naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (see Fig E3, A and B, in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). In vitro T-cell proliferation in response to combination of anti-CD3+ 1 anti-CD28+, cytokines (IL-15, IL-2), and mitogens was largely normal, whereas response to low-dose CD3 and antigens was defective in some cases (Table E7). The TCR repertoire was persistently oligoclonal in 2 of 7 tested patients and transiently oligoclonal in 1 patient (Fig E3, C; Table E6). The proportion and phenotype of Treg cells was variable (Fig 2, B; see Fig E4, A, in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org); however, In vitro expanded Treg cells showed decreased expression of all Treg-cell markers including FOXP3, Helios, CD25, and CTLA-4 (Fig 2, C; Fig E4, B). Treg-cell suppressor activity against CD4+ (Fig 2, D and E) and CD8+ T allogeneic responder cells was defective (Fig E4, C). An increase in the CD3-CD56brightCD16neg NK-cell subpopulation (27% in P2, 24% in P3, and 21% in P4) was noted when tested (P2, P3, and P4) (see Fig E5 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org; data not shown). Impaired NK-cell degranulation in the presence of K562 cells was observed and similarly to patients6 with Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome IL-2 restored degranulation and killing to normal levels (Fig 2, F; data not shown).

FIG 2.

Immune cell abnormalities. A, Representative plots of the altered B-lymphocyte staining (left panel), B-lymphocyte percentage (middle panel), and CD19 expression (geometric mean fluorescence intensity, right panel) in ARPC1B-deficient patients. For CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets (naive, memory, and effector-memory populations), see Fig E1. B, Treg-cell subset analysis with a representative dot plot showing percentage of Treg cells (CD4+CD25RAposCD127neg), and Treg FOXP3 and Helios expression. C, FOXP3 and Helios expression of In vitro expanded Treg cells from patient and control (lines connect each patient with their own healthy relative used as control). D, FACS plots showing the proliferation of allogeneic T-responder cells (Tresp) measured by cell-trace violet (CTV) dilution. The stimulated and unstimulated Tresp without Treg cells are shown in blue. Treg cells from controls (in gray) and patients (in red) were cultured at different ratios with Tresp cells while stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28. E, Quantification of CD4 and CD8 Tresp-cell suppression by Treg cells. F, NK cells of patients were functionally evaluated against the K562 cell line by CD107A expression experiments. Resting NK cells (left panel) and IL-2–stimulated cells (right panel) were evaluated and compared with 10 healthy controls. All controls are represented by healthy adults. Bars indicate means ± SD, and a star indicates statistical significance as assessed by Mann-Whitney test (P < .05). Stim, Stimulated; unstim, unstimulated.

Most patients received antibiotic prophylaxis (71%). One patient with recurrent oral candidiasis remained on antifungal prophylaxis. “Auto”inflammatory manifestations appear to respond to steroids, mofetil mycophenolate, and sirolimus. The response to TNF-blocking agents was unsatisfactory. To date, 5 patients have been treated with HSCT. Two patients have a medium/long-term follow-up of 1 and 6 years, respectively, and are in good health and off all medication (P2 and P6). The other 3 patients (P3, P9, and P12) have only recently been transplanted, and they are alive and well, with resolution of all “auto”inflammatory features.

In conclusion, our cohort delineates a more detailed and larger spectrum of ARPC1B deficiency phenotypes compared with previous reports. The clinical defect appears to be characterized by recurrent bacterial and viral infections, extensive eczema, allergies, thrombocytopenia, and skin vasculitis, together with bleeding often manifested as early onset gastric hemorrhage and hemorrhagic colitis. The eczematous skin phenotype can be explained by immune-mediated allergic responses and the anaphylactic reactions can be avoided by elimination of food allergens from the diet. The defective Treg-cell function is suggested to be involved in both the exaggerated TH2 responses and IgE reactivity against allergens.7 Defects in cytoskeleton rearrangement, altered immunologic synapses formation, and reduced chemotaxis have been recently identified in ARPC1B-deficient patients’ T cells,4 suggesting that they may play a role in the susceptibility to infections. In addition, patients’ NK cells show a peculiar phenotypic profile and an impaired functionality including both migration defects and NK-cell dysfunction, which may well contribute to the predisposition to viral infections seen in ARPC1B-deficient patients. The neutrophil and macrophage abnormalities may explain the susceptibility of the patients to bacterial infections1 in the presence of normal antibody levels. Although careful monitoring, antimicrobial prophylaxis, and adequate treatment are mandatory to prevent and counter infections, the immunodysregulation contributing to vasculitis and arthritis requires immunosuppression. The unique and variable combination of clinical features makes ARPC1B deficiency a complex disease entity for which HSCT is considered a curative treatment option.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The study was partly supported by grants of the Italian Ministero della Salute (Programma di rete, NET-2011–02350069), the European Commission (ERARE-3-JTC 2015 EUROCID) and Fondazione Telethon (TIGET Core grant C6). L.D.N. is supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md, and also supported in part by a US National Institutes of Health, National Human Genome Research Institute/National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grant to the Baylor Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics (UM1 HG006542) and by NIHNHGRI/NHLBI grant UM1HG006542 to the Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics. J.S.O. is supported by NIH grant R01AI120989. The study was partly supported by a grant of the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung to the University of Ulm (PID NET3; 01GM1517B). This study was supported by a starting grant from the University Hospital Ulm to A.B., as well as by a grant for the Center of Immunodeficiencies Amsterdam (CIDA).

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kuijpers TW, Tool ATJ, van der Bijl I, de Boer M, van Houdt M, de Cuyper IM, et al. Combined immunodeficiency with severe inflammation and allergy caused by ARPC1B deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;140:273–7.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahr WH, Pluthero FG, Elkadri A, Warner N, Drobac M, Chen CH, et al. Loss of the Arp2/3 complex component ARPC1B causes platelet abnormalities and predisposes to inflammatory disease. Nat Commun 2017;8:14816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Somech R, Lev A, Lee YN, Simon AJ, Barel O, Schiby G, et al. Disruption of thrombocyte and T lymphocyte development by a mutation in ARPC1B. J Immunol 2017;199:4036–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brigida I, Zoccolillo M, Cicalese MP, Pfajfer L, Barzaghi F, Scala S, et al. T cell defects in patients with ARPC1B germline mutations account for their combined immunodeficiency. Blood 2018;132:2362–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su HC, Jing H, Angelus P, Freeman AF. Insights into immunity from clinical and basic science studies of DOCK8 immunodeficiency syndrome. Immunol Rev 2019;287:9–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gismondi A, Cifaldi L, Mazza C, Giliani S, Parolini S, Morrone S, et al. Impaired natural and CD16-mediated NK cell cytotoxicity in patients with WAS and XLT: ability of IL-2 to correct NK cell functional defect. Blood 2004;104:436–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanzi G, Moratto D, Vairo D, Masneri S, Delmonte O, Paganini T, et al. A novel primary human immunodeficiency due to deficiency in the WASP-interacting protein WIP. J Exp Med 2012;209:29–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.