Abstract

Background:

Parent/caregiver or child/youth self-report and pill counts are commonly used methods for assessing adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) among children and youth with HIV. The purpose of this study was to compare these different methods with one another and with viral load.

Methods:

Randomly selected parent/caregiver and child/youth dyads were interviewed using several adherence self-report measures and an announced pill count was performed. Adherence assessment methods were compared with one another and their relative validity was assessed by comparison with the child’s viral load close to the time of the interview or pill count, adjusting for primary caregiver, child age, and child disclosure of the diagnosis.

Results:

There were 151 evaluable participants. Adherence rate by pill count was ≥ 90% in 52% of participants, was significantly associated with log(RNA) viral load (p=0.032), and had significant agreement with viral load < 400 copies/mL. However, pill count data were incomplete for 26% of participants. With similar proportions considered adherent, a variety of self-report adherence assessment methods also were associated with log(RNA) viral load including: “no dose missed within the past one month” (p=0.054 child/youth interview, p=0.004 parent/caregiver interview), and no barrier to adherence identified (p=0.085 child/youth interview, p=0.015 parent/caregiver interview). Within-rater and inter-rater agreement was high among self-report methods. Three day recall of missed doses was not associated with viral load.

Conclusion:

Findings demonstrate the validity of adherence assessment strategies that allow the parent/caregiver or child/youth to report on adherence over a longer period of time and to identify adherence barriers. Adherence assessed by announced pill count was robustly associated with viral load, but there was incomplete data for many participants.

Keywords: HIV, children, antiretroviral therapy, adherence

INTRODUCTION

While major improvements in the care of children with perinatally acquired HIV disease in the United States and other developed countries have resulted in greatly improved survival1, non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) is well-established as a major cause of clinical failure, and intermittent non-adherence is a particular problem. Studies in adults have demonstrated greater than 95% adherence to the regimen is necessary for durable suppression of viral load2. With large numbers of babies born worldwide with perinatally-transmitted HIV infection3 and the global effort underway to increase access to ART for HIV-infected children, pediatricians and other child health care providers will continue to be called upon to assess and support adherence to ART in children and youth with HIV.

Assessment of adherence in this population is challenging and potentially labor intensive. A number of methods have been utilized to assess adherence4. Parent/caregiver and child/youth interview or self-report are the most feasible methods in the clinical care setting, but they are potentially subject to the interviewee over-estimating adherent behavior to satisfy clinicians. A variety of self-report strategies with differing periods of recall have been utilized with varying results. Few studies have compared different self-report methods with one another, and many have not evaluated or have failed to demonstrate an association between self-report of adherence and viral load. The pill count method to estimate adherence involves a comparison between the amount of medication remaining in the child’s prescription bottle and the amount that should be remaining based on the amount and dosage of the initial prescription and the length of time since the patient began using the bottle. This method provides a measure of adherence over time, but may be inaccurate due to inadequate documentation of the date the bottle was first utilized versus filled, use of multiple medication bottles containing the same formulation, or ‘pill dumping’ (the parent or child may remove unused pills from the bottle in an effort to falsely increase the apparent level of adherence). There are few published studies evaluating the pill count method, all with small sample sizes limiting analyses5,6,7. Other adherence assessment methods, including pharmacy medication refill records and electronic monitoring, are less practical in the clinical care setting. In this report, we examined the use of an announced pill count as well as a variety of adherence self-report methods among perinatally HIV-infected children and youth and their caregivers, evaluating the correlation of each of these methods with viral load and with one another. We hypothesized self-report methods would categorize a higher proportion of participants as adherent than the pill count method, and that the pill count method would most robustly correlate with viral load.

METHODS

Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (PACTG) protocol P1042S was a sub-study of PACTG protocol P219C, a multi-center cohort study that enrolled and followed both HIV-infected and uninfected perinatally-exposed children in the U.S. since September 2000. P219C was a revision of PACTG 219 which was initiated in 19931. For sub-study P1042S, 159 perinatally infected children and youth (aged 8 to <19 years) were randomly selected and agreed to participate from those P219C participants who were prescribed ART and had English or Spanish as their primary language. The study was approved by institutional review boards at all participating sites. Assent or written informed consent was obtained from youth participants. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all youth younger than the age of consent.

Socio-demographic data, ART use, HIV immunologic status, and previous and current diagnoses were collected in P219C at regular intervals by abstracting from the participant’s medical record. The present analyses included HIV-1 viral load obtained within a six month window closest to the time of the particular adherence assessment method. Viral load measurements less than 400 copies/mL or below the limits of detection were assigned a value of 400.

Measures

Unless otherwise specified, all measures were administered in scripted interview format in the respondent’s primary language, English or Spanish, by a research staff member.

PACTG Adherence Module 1:

The respondent was the person self-identified as primarily responsible for the youth’s adherence to the ART regimen. Youth respondents had to be aware of their diagnosis by name to serve as the respondent or be present for this interview because HIV is discussed by name. The questionnaire and instructions for administration are publicly available and described previously8,9,10. The questionnaire begins with identification of ART medications and then asks the respondent about missed doses for each medication during the prior three days, asking about each day in reverse order beginning with the day before. Participants were classified as adherent if the respondent indicated no doses of any ART medication were missed during the 3 days of report.

P1042S Child/Adolescent Questionnaire.

The Child/Adolescent Questionnaire was administered to the child/youth in private. It was designed for P1042S to elicit information about medication adherence, barriers to adherence, and responsibility for health-care tasks. The items were selected from questionnaires already employed in the PACTG and the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group10,11,12,13,14. HIV is not specifically mentioned in the script, thus youth who were not aware of their diagnosis by name were included. Respondents reported on the approximate time since they last missed a dose of ART medication (within the last week, 1 to 2 weeks ago, 3 to 4 weeks ago, 1 to 3 months ago, more than 3 months ago, or never).

The questionnaire also included 20 questions pertaining to barriers to adherence. Each of these items asked the interviewee how often a particular situation (for example: too much medication, timing of medication dosing did not fit patient’s schedule, etc.) was perceived as a barrier to the youth’s medication adherence in the past month. A binary outcome was used based on responses to these questions, where each participant was categorized as having: either no barrier to adherence if the rater responded “never or rarely” to each item, or at least one barrier to adherence if the rater chose a response other than “never or rarely” to at least one of the cited potential barriers.

An additional section, focusing on responsibility for various tasks related to medication adherence, was adapted from the Diabetes Family Responsibility Questionnaire15. The section contained four tasks required for medication adherence: remembering to take morning medication, remembering to take evening medication, making sure medications are taken just as prescribed (for example, with food or on an empty stomach), and making sure there is enough medication to last until the next clinic visit. Respondents chose among categorical responses describing degree of responsibility for each task. These were coded at analysis so that higher scores indicated increasing responsibility of the youth.

P1042S Parent/Caregiver Questionnaire.

The Parent/Caregiver Questionnaire was an analogous version of the Child/Adolescent Questionnaire containing the same items with minor rewording to accommodate the perspective of the parent/caregiver. Adherence related questions requested information about the youth’s adherence; questions about physical and emotional well-being requested information regarding the parent/caregiver’s functioning rather than that of the youth.

Pill Count.

A pill count was scheduled 4 to 8 weeks after enrollment in P1042S and approximately 30 days after ART medications were due to be refilled, with the goal of assessing adherence during the prior month. The pill count was performed by study staff outside of the presence of participants. Liquid formulations were measured in mL and Nelfinavir powder was measured in scoops. The percentage of pills taken or volume of medication consumed for the whole regimen over the 30-day interval was computed by dividing the actual number of pills or volume presumably administered by the expected number of pills or volume for the whole regimen, multiplied by 100%. Values greater than 110% were considered invalid and not included in analyses. Values greater than 100% but less than 110% were adjusted to 100% for analysis. This methodology was originally described by Naar-King et al.5 and Steele et al.6 and adapted by the PACTG.

Statistical Analysis

Fisher’s exact tests or Pearson’s chi-square tests, whichever were appropriate, were used to determine whether participants who had pill count data differed from those without pill count data with respect to selected participant characteristics. These tests also were used to compare P1042S participants and non-participating eligible subjects in PACTG 219C with respect to these characteristics. Kappa statistics and their corresponding 95% confidence limits were used to determine agreement between viral load detectability and binary representations of all measures of adherence considered, agreement between each of the binary representations of self-report adherence measures and pill count adherence, as well as inter-rater and within-rater agreement in reporting adherence and barriers to adherence. Corresponding associations between any of these binary outcomes were assessed using Fisher’s exact test, and multivariate logistic regression was used to further explore associations.

HIV RNA values less than or equal to 400 copies/mL were truncated to 400 copies/mL to account for variations in the lower limit of various viral load assays. Hence, viral load data was left-censored with the censoring value of 400. Due to the censored nature of the log transformed viral load data, multivariate censored regression was used to determine associations between log(RNA) and binary representations of each of the measures of adherence considered, adjusting for age of child/youth at study entry, primary caregiver (whether biological parent or not) and child knowledge of HIV diagnosis by name. Since the distribution of data for percentage of pills taken was highly skewed, Spearman’s rank correlation was used to determine associations between log(RNA) and pill count adherence rates.

RESULTS

Study Population

Among 420 potential P1042S participants randomly selected from P219C participants, 159 agreed to participate and were enrolled. Of the 261 potential participants who were not enrolled, 99 declined to enroll, 91 were deemed ineligible and 62 were never approached due to closure of the study to accrual, and no information was available for 9. Of those 99 who declined to enroll, 47% volunteered a reason which in most cases could be categorized as inadequate time or logistical concerns. Among the 159 participants who were enrolled in the study, 151 were considered evaluable. The other eight participants were considered non-evaluable and their data excluded from analyses because they became ineligible between screening and enrollment, withdrew consent prior to study completion, were unable to comply with study requirements, or there was a randomization error.

Selected demographic and clinical characteristics of the 151 evaluable participants are shown in Table 1. The majority of participants (86%) self-identified as African-American or Hispanic. More than half of the youth (61%) were 12 years and older. All but nine (6%) were receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens including two or more drug classes, with 4 (3%) prescribed a regimen including a fusion inhibitor. Most (63%) of the primary caregivers had completed high school, some college, or were college graduates. Among the youth, 27% had repeated a grade in school, and 40% required special help or special education classes in school. Seventy percent of youth were aware of their diagnosis. The participants in P1042S were not significantly different from those in P219C, except that a somewhat higher proportion of participants in P1042S had a viral load less than 400 copies/mL (59% vs 48%, p=.04). and a higher proportion of participants in P1042S were on 3 or more ART drugs from 2 or more classses (94% vs 79%, p<0.01).

Table 1:

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants (N=151)

| |

||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | (%) |

| Female | 68 | (45%) |

| Age | ||

| 8 - < 12 Years | 60 | (40%) |

| 12 - < 16 Years | 75 | (50%) |

| 16 - < 19 Years | 16 | (10%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White/Others | 22 | (14%) |

| African-American | 87 | (58%) |

| Hispanic | 42 | (28%) |

| Spanish Primary Language | 22 | (15%) |

| Primary Caregiver | ||

| Biological Parent | 63 | (42%) |

| Relative | 39 | (26%) |

| Other Adult | 48 | (31%) |

| Shelter/Home | 1 | (1%) |

| Education Level of Primary Caregiver | ||

| Grade 1–11 | 41 | (27%) |

| High School Graduate | 39 | (26%) |

| Some College/Technical School | 42 | (28%) |

| College Graduate or Higher | 13 | (9%) |

| Other/Not reported | 16 | (10%) |

| Disclosure of Diagnosis to the Child/Youth | ||

| Child Aware of Diagnosis | 105 | (70%) |

| Child Not Aware of Diagnosis | 41 | (27%) |

| Not Reported | 5 | (3%) |

| CD4 Percent | ||

| 15% or less | 13 | (9%) |

| 15–25% | 36 | (25%) |

| 25% or more | 95 | (66%) |

| Missing | 7 | (−) |

| HIV-1 Viral Load (copies/ml) | ||

| 400 copies or less | 85 | (59%) |

| 400–10,000 copies | 19 | (13%) |

| 10,000 100,000 copies | 31 | (22%) |

| > 100,000 copies | 8 | (6%) |

| Missing | 8 | (−) |

Self-Report Adherence Assessments

Of the 151 participants, 146 (97%) completed the PACTG Adherence Module 1, providing a 3 day recall of adherence. Parents/caregivers completed 52% of the modules and children/youth completed 47%; the respondent for one interview (<1%) was not specified. Nineteen participants (13%) reported missing at least one dose during the prior 3 days. Most (87%) respondents stated that the youth had missed no doses during the prior 3 days, and thus were classified as adherent. The responsibility scale was consistent with the choice of respondent interviewed.

The Child/Adolescent Questionnaire was completed by 132 youth. Nineteen (14%) questionnaires were not completed or were considered invalid by study staff, most commonly due to insufficient time, subject refusal, or poor comprehension of the questions. The results indicated 60 (45%) youth missed a dose within the past 1 month, 13 (10%) within the past 1–3 months, 18 (14%) greater than 3 months ago, and 41 (31%) had never missed a dose. Of the 132 completing the questionnaire, 132 (100%) completed the section pertaining to barriers to adherence. Eighty-nine (67%) cited at least one barrier to adherence within the past month (Table 2).

Table 2:

Reported Barriers to Adherence

| Barriers to Adherence | Child/Adolescent Report N=132 Number (%) | Parent/Caregiver Report N =138 Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| At least one barrier to adherence | 89 (67%) | 77 (56%)* |

| At least one logistic issuea | 81 (61%) | 64 (46%)* |

| At least one regimen issueb | 38 (29%)* | 20 (14%)* |

| At least one child factorc | 46 (35%)* | 34 (25%) |

| At least one disclosure issued | 16 (12%)* | 20(14%) |

| Child mental statee | 11 (8%) | - |

| Caregiver mental statee | - | 5 (4%) |

“couldn’t get medications- drugstore did not have supply”; “didn’t refill”; “forgot”; “scheduling interferes with lifestyle”; “multiple caregivers”; “were away from home”; “were busy with other things”; “had a change in daily routine”; “fell asleep or slept through dose time”; “ran out of pills”

“taste, can’t get it down, spits up”; “side effects, toxicity”; “had too many pills to take”; “wanted to avoid side effects”; “felt like the medication was toxic or harmful”; “had problems taking pills as directed, for example on an empty stomach”

“child refuses”; “child had intercurrent illness”; “child felt sick or ill”; “child felt good”

“concerns about disclosure” (Parent/Caregiver report only); “did not want others to notice medication”

“felt depressed or overwhelmed”

One-tailed P-value <.05 for association with Log (RNA) viral load by multivariate censored regression adjusted for age at study entry, primary caregiver (biological parent vs. others) and child knowledge of HIV diagnosis by name. Age at study entry was a significant covariate (positive association) in all multivariate models.

The Parent/Caregiver Questionnaire was completed by 138 caregivers. Twelve participants did not complete the measure due to insufficient time or a missed study visit, and one questionnaire was considered invalid due to respondent inattentiveness. The results of the Parent/Caregiver Questionnaire indicated 50 (36%) of the youth had missed a dose of ART medication within the past month, 20 (15%) within the past 1–3 months, 17 (12%) more than 3 months ago, and 51 (37%) had never missed a medication dose. All respondents completed the section pertaining to barriers to the child/youth adhering to medications with 77 (56%) citing at least one barrier to adherence in the past month. The categories of barriers cited were similar to those cited by the youth (Table 2).

Pill Count Adherence Assessments

A subset of 120 participants (79%) completed a pill count, and all but 2 (<2%) pill counts were completed within 7 weeks of self-report adherence measures. Pill counts were not performed for 31 (21%) participants for the following reasons: non-return of medication bottle (10), missed visit (8), prescribed drug holiday (3), participant refusal (5), not following instructions (2), caregiver illness (1), child/youth death (1), or study withdrawal (1). Data for an additional eight participants were considered invalid; three had missing data for at least one drug in the regimen and five had a calculated percentage of pills taken greater than 110%. Thus, an evaluable pill count was available for 112 (74%) participants. There were no significant differences between these 112 and the 39 participants with missing or invalid pill count data with respect to ART regimen or the participant characteristics listed in Table 1.

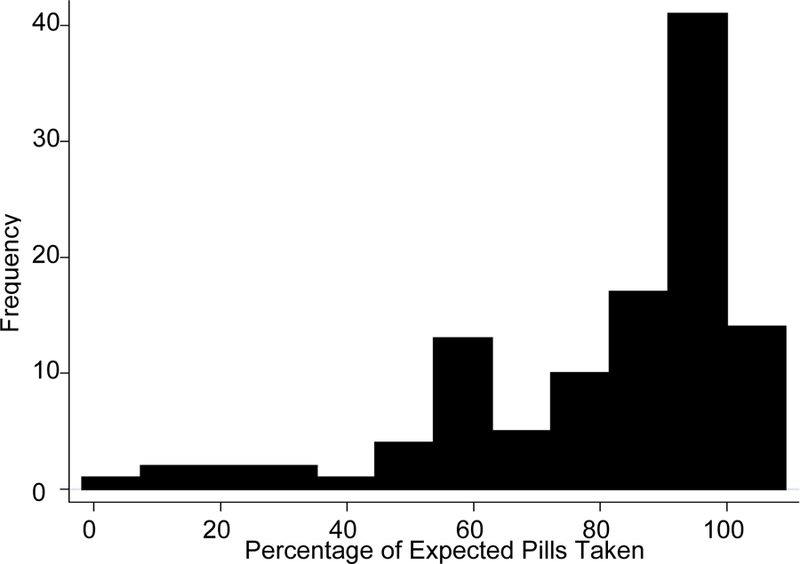

Figure 1 shows the distribution of percentage of expected pills taken for the interval based upon pill count. The median percentage of pills taken was 90% and the inter-quartile range was 26%. Fifty-eight (52%) participants were at least 90% adherent based upon the pill count assessment, 73 (65%) were at least 80% adherent, and 86 (77%) were at least 70% adherent.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Pill Count Adherence Rates (N = 112)

Agreement Between Adherence Assessment Methods and Viral Load

Associations between log(RNA) viral load and different adherence assessment methods adjusted for age at study entry, primary caregiver (biological parent or not) and child knowledge of HIV diagnosis were evaluated and are shown in Table 3. There was no significant association between log(RNA) and 3 day recall provided by the PACTG Adherence Module 1. Correlations between various responses on the Parent/Caregiver and Child/Adolescent Questionnaires were noted, but the most robust negative association was with no missed dose during the past month and no barrier to adherence cited by the parent/caregivers. Negative correlations between these responses and viral load for the children/youth were of borderline significance, with a positive association between log(RNA) and older age at enrollment noted on multivariate analysis. A number of barrier categories cited by both parent/caregiver or child/youth were associated with log(RNA) viral load (Table 2). Similarly, there was a positive association between age of the child/youth and log(RNA) noted on multivariate analysis. Various cutoffs for pill count adherence rate also were associated with log(RNA), but the most robust association was with a pill count adherence rate ≥ 90%. A significant negative association between log(RNA) viral load and pill count adherence rate was also noted, indicating participants with higher pill count adherence rates had lower viral loads (Spearman’s correlation coefficient with Log(RNA) = −0.192, lower-tailed p-value = 0.023).

Table 3:

Associations between Adherence Measures and Log(RNA) Viral Load

| Proportion Categorized as Adherent | Univariate Censored Reg’n Lower-tailed P-value | Multivariatea Censored Reg’n Lower-tailed P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Dose Missed on Three Day Recallb (PACTG Adherence Module 1) |

127/146 (87%) | 0.602 | 0.564 |

| No Dose Missed Within the Past One Monthb (Child/Adolescent Questionnaire) |

72/132 (55%) | 0.024 | 0.054 |

| No Dose Missed Within the Past One Monthb (Parent/Caregiver Questionnaire) |

88/138 (64%) | 0.006 | 0.004 |

| No Barrier to Adherenceb (Child/Adolescent Questionnaire) |

43/132 (33%) | 0.074 | 0.085 |

| No Barrier to Adherenceb (Parent/Caregiver Questionnaire) |

61/138 (44%) | 0.017 | 0.015 |

| Pill Count Adherence Rate ≥ 90%c | 58/112 (52%) | 0.020 | 0.032 |

adjusted for age of child/youth at study entry, primary caregiver (biological parent vs. others) and child knowledge of HIV diagnosis by name

age at study entry was a significant covariate (positive association)

age at study entry was a marginally significant covariate (positive association)

Considering viral load as a binary variable greater than or less than 400 copies/mL, there was significant but weak agreement with pill count adherence rate ≥ 90% (Kappa = 0.24 (95% CI: 0.06, 0.42)) with sensitivity 64% and specificity 62%. When non-completion of pill counts, incomplete pill counts or invalid pill counts were included in the non-adherent group, the results remained unchanged. There was no significant association between viral load as a binary variable with any of the self-report assessment methods. However, caregiver-reported non-adherence within the past month [Kappa=0.16, 95% CI:(0.002, 0.31)] and caregiver-reported barrier to adherence [Kappa=0.16, 95% CI:(0.004, 0.32)] showed significant, although weak, agreement with viral load as a binary variable.

Correlation and Agreement Among Adherence Assessment Methods

Utilizing multivariate logistic regression to adjust for respondent on the PACTG Adherence Module 1, we found participants who reported missing a dose on three day recall were also more likely to report missing a dose within the past month on the Child/Adolescent (p=0.002) and the Parent/Caregiver (p<0.001) Questionnaires. Of the 125 caregiver/child pairs completing both a Child/Adolescent and Parent/Caregiver Questionnaire, 98 pairs (78%) were concordant and 27 (22%) were discordant reporting missing a dose within the month prior to the study visit. There was significant inter-rater agreement, with Kappa = 0.56 (95% CI: 0.41, 0.70). Ninety-three (74%) pairs were concordant and 32 (26%) were discordant identifying at least one barrier to adherence. There was significant inter-rater agreement, with Kappa = 0.48 (95% CI: 0.32, 0.63). In addition, there was significant within-rater correlation between missing a dose within the past month and identifying at least one barrier to adherence for both the Child/Adolescent (Kappa= 0.49 (95% CI: 0.36, 0.62)) and the Parent/Caregiver (Kappa= 0.51 (95% CI: 0.38, 0.64)) Questionnaires.

We assessed agreement between each of the self-report measures and pill count as a binary measure with cutoffs of ≥80% and ≥90%. There was agreement between no missed dose as reported on the Child/Adolescent Questionnaire and pill count adherence rate ≥ 80%, but the agreement was weak (Kappa = 0.182) with high sensitivity (86%) and low specificity (36%). When pill count adherence rates were considered as a continuous measure, we found an association between missing a dose based on the Child/Adolescent Questionnaire and pill count adherence rate (Wilcoxon one-tailed p value = 0.043).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this report is the largest evaluation utilizing pill counts as an adherence assessment strategy among HIV-infected children and youth. As the study was designed to be interwoven with routine clinical care, participants were intended to be representative of children and youth with HIV in the U.S. receiving care in a clinical setting rather than those enrolled in a clinical trial. We found 52% of participants had a pill count adherence rate ≥ 90%. This was associated with viral load as a continuous measure and it also had significant agreement with viral load as a binary measure (greater than or less than 400 copies/ml). However, the use of pill counts in this setting proved logistically challenging, with evaluable data for only 74% of participants. The feasibility challenge is similar to the findings of Naar-King et al.5 and Steele et al.6 who reported pill counts were feasible, but pill count adherence rates were considerably higher than electronic monitoring adherence rates. Although data collection tools were adapted in our study for various formulations of antiretroviral medications, site study staff reported challenges with accurate measurement when medications were in liquid or powder form. It is important to note, pill counts were announced or scheduled with participants in advance. In studies with adults, unannounced pill counts conducted in the home were reported to be more robustly associated with biological outcomes16. Although challenging within the context of routine clinical care of HIV-infected children and youth with HIV, further evaluation of the use of pill counts as an adherence assessment strategy in the interventional trial and home visit settings is warranted.

We compared various self-report adherence assessment measures with respect to their association with viral load. The most widely used self-report measure, the PACTG Adherence Questionnaire assessing three day recall of missed doses, categorized a much higher proportion of participants as fully adherent than other methods and was not associated with viral load. The absence of an association with viral load is not consistent with the report of Williams et al9 of a large sample of 2,088 participants interviewed with the same instrument in the PACTG 219C study, from which this sample was recruited. The discrepancy may be related to the smaller sample size in this study and the inclusion of younger children in the Williams sample. There was limited agreement between adherence and viral load detectability in the Williams et al9 report, with many participants considered adherent with detectable viral load and some non-adherent participants with undetectable viral load. A study using the same instrument in a clinical trial population of 125 children classified 70% as adherent and also found an association with viral load, but did not assess agreement8. Two studies outside of the clinical trial setting6,17 found results similar to our own, with the 3 day recall method not associated with viral load and overestimating adherence when compared with pill count, pharmacy refill, or electronic monitoring.

A number of factors may contribute to the limitations of the three day recall assessment strategy. Social desirability bias may be particularly important when an adherence interview focuses on the most recent period or on an undesirable behavior such as missed doses18. Alternative adherence assessment methods, focused on a 24 hour recall of activities rather than specific questions regarding missed doses, have been reported with encouraging results19,5,20. In addition to the challenge of socially desirable responding, families may improve their adherence behavior during the few days immediately preceding a medical visit. This phenomenon has been reported among HIV-infected adults21. Lastly, this assessment, conducted on a twice yearly basis with PACTG 219C study participants, may have become routine with participants and warranted less attention than the other assessment methods which were unique to the sub-study and otherwise unfamiliar. The report by Williams et al9 found self-reported adherence with this method increased with the number of prior adherence interviews. While the three day recall was inferior to other self-report strategies in our study, it is useful for those admitting non-adherence using this method. We found good within-rater agreement between this measure and other measures for non-adherers.

A clinically useful finding of our study is that caregiver report adherence assessment methods that incorporate questions to address adherence over a longer period as well as questions focused on barriers to adherence were as robustly associated with viral load as pill count. These measures classified a similar proportion of participants as adherent and demonstrated good within-rater agreement and inter-rater agreement for child/caregiver dyads. A number of prior studies support the utility of focusing on adherence over a longer period.22,23,19 Our finding that identification of at least one barrier to adherence was robustly associated with higher viral load is particularly useful as the care team can work with the family to address the barrier identified and thereby improve adherence. Prior reports20,24 found the identification of barriers on a 24-hour recall phone interview to be marginally related to viral load and that poor adherence measured by pharmacy refill records was associated with the number of barriers reported.

The degree of responsibility for medication dosing (caregiver vs. youth) may affect the validity of self-report measures. Prior studies have found poor agreement between youth report of their medication adherence and the report of their adult caregivers25,26 and discrepancies between child-caregiver adherence reports were associated with poorer adherence assessed by electronic monitoring27. However, we found robust inter-rater agreement among child/caregiver dyads for last dose missed and for barrier identification. In fact, a higher proportion of children/youth respondents versus caregiver respondents reported doses missed or a barrier to adherence, thus the proportion categorized as adherent by the various methods based upon the child/youth responses was lower (see Table 3). The degree of responsibility measure was not utilized with the PACTG Adherence Questionnaire as a means to identify the person primarily responsible for medication adherence for interview. Use of a formal responsibility measure with this instrument may improve validity.

While our study has a number of strengths including a comparison of a number of feasible adherence measures with each other and with viral load, some limitations may have affected analyses. Logistical constraints to obtaining pill counts limited evaluation of this assessment method, and may have reduced our power to observe associations and correlations. In addition, the study design necessitated the pill count was performed somewhat later than the adherence questionnaires. While there was strong agreement among self-report measures, agreement between pill count and self-report measures was limited. We performed a sensitivity analysis which repeated selected analyses to include participants missing pill count data for possible adherence-related reasons (for example child or caregiver refusal) and classified them as non-adherent. This analysis did not appreciably change our findings. While all but one of the adherence measures evaluated was robustly associated with viral load as a continuous variable, pill count alone was associated with the clinically important viral load threshold of < 400 copies/mL. The majority of children/youth participating in this study were heavily ART experienced and ART was prescribed based upon the best clinical judgment of their physician. Consequently, a viral load < 400 copies/mL may not have been a realistic goal of current therapy for a number of study participants. This problem has been noted in a study of adolescents with HIV19 and in a meta-analysis of studies of adults with HIV28. In addition, pill sharing within the household is possible, and ART utilization by other family members was not measured.

CONCLUSIONS

For pediatricians managing children with chronic illness, these findings highlight the validity of adherence assessment strategies that allow the parent/caregiver or child/youth to report on adherence over a longer period of time and/or identify adherence barriers. These self-report strategies may be incorporated easily into the clinical care setting. Furthermore, the identification of barriers to adherence provides an opportunity for medical personnel to address specific difficulties and thus improve adherence. While validated by viral load association and agreement, the feasibility challenges with announced pill counts as an adherence assessment strategy will likely preclude wide use of this method outside of interventional trials. Regardless of the adherence assessment method utilized, the proportion of participants categorized as adherent was far lower than necessary for long term optimal health outcomes and underscores the adherence challenges caring for perinatally HIV-infected children and youth.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the children and families for their participation in PACTG 1042S, and the individuals and institutions involved in the conduct of P1042S. The study was funded by the United States National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. These institutions were involved in the design, data collection and conduct of protocol P1042S, but were not involved in the present analysis, the interpretation of the data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit for publication. This work was supported by the Statistical and Data Analysis Center (SDAC) of the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group at Harvard School of Public Health, under the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases cooperative agreement No. 5 U01 AI41110.

The following institutions and individuals participated in PACTG Protocol 1042S, by order of enrollment: Children’s Hospital Boston: K. McIntosh, B. Kammerer, S. Burchett; University of Maryland School of Medicine: S. Allison, V. Tepper, C. Hilyard: State University of New York at Stony Brook School of Medicine: S. Nachman, J. Perillo, M. Kelly, D. Ferraro: St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children: J. Foster, J. Chen, D. Conway, R. Laguerre; Children’s Memorial Hospital: R. Yogev, E. Chadwick, K. Malee; Jacobi Medical Center: A. Wiznia, Y. Iacovella, M. Burey, R. Auguste; University of California San Francisco School of Medicine: D. Wara, M. Muskat, N.Tilton; St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital: P. Garvie, D. Hopper, M. Donohoe, S. Carr; Tulane Medical School - Charity Hospital Medical Center of Louisiana at New Orleans: R. Van Dyke, P. Sirois, C. Borne, S. Bradford, K. Jacobs, A. Ranftle; Children’s Hospital - University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center: R. McEvoy, S. Paul, E. Barr, M. Abzug; University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, New Jersey Medical School: J. Oleske, L. Bettica, L. Monti, J. Johnson; Texas Children’s Hospital: M. Paul, C. Jackson, L. Noroski, T. Aldape; Baystate Medical Center: B. Stechenberg, D. Fisher, S. McQuiston, M. Toye; University of Miami Miller School of Medicine: G. Scott, C. Mitchell, E. Willen, L. Taybo; University of California San Diego: S. Spector, S. Nichols, State University of New York Downstate Medical Center: H. Moallem, S. Bewley, L. Gogate; San Juan City Hospital: E. Jimenez, J. Gandia, D. Miranda; Duke University School of Medicine: O. Johnson, J. Simonetti, K. Whitfield, F. Wiley; Harlem Hospital Center: E. Abrams, M. Frere, D. Calo, S. Champion; University of Puerto Rico: I. Febo, R. Santos, N. Scalley, L. Lugo; Children’s National Medical Center: D. Dobbins, M. Lyon, V. Amos, H. Spiegel; Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center: E. Stuard, A. Cintron; Johns Hopkins University: N. Hutton, B. Griffith; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine: T. Belhorn, J. McKeeman; New York University School of Medicine: W. Borkowsky, S, Deygoo, E. Frank, S. Akleh; Yale University School of Medicine: W. Andiman, M. Westerveld; State University of New York Upstate Medical University: R. Silverman, J. Schueler-Finlayson; Los Angeles County/University of Southern California Medical Center: A. Stek, A. Kovacs; University of Alabama at Birmingham: R. Pass, J. Ackerson, H. Charlton, M. Crain; Medical College of Georgia School of Medicine: C. Mani; North Broward Hospital District, Children’s Diagnostic & Treatment Center: A. Puga, J. Blood, A. Inman; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia: S. Douglas, R. Rutstein, C. Vincent, G. Koutsoubis; Long Beach Memorial Medical Center: A. Deveikis, R. Seay, S. Marks; J. Batra; ; Howard University Hospital: S. Rana, O. Adeyiga, R. Rigor-Mator, S. Wilson; Children’s Hospital and Research Center Oakland: A. Petru T. Courville; Phoenix Children’s Hospital: J. Piatt, M. Lavoie

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure of Authors: no disclosures

REFERENCES

- 1.Gortmaker SL, Hughes M, Cervia J, et al. Effect of combination therapy including protease inhibitors on mortality among children and adolescents infected with HIV-1. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 1522–1528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller LD, Hayes RD. Adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy: synthesis of the literature and clinical implications. AIDS Read 2000;10:177–185 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (2006). Antiretroviral therapy of HIV infection in infants and children in resource-limited settings: towards universal access, recommendations for a public health approach 2006. Available at:www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines. Accessed October 1, 2007. [PubMed]

- 4.Simoni JM, Montgomery A, Martin E, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for pediatric HIV infeciton: A qualitative systematic review with recommendations for research and clinical management. Pediatrics 2007;119(6): Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/119/6/e1371. Accessed October 21, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naar-King S, Frey M, Harris M, Arfken C. Measuring adherence to treatment of paediatric HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care 2005; 17: 345–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steele RG, Anderson B, Rindel B, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive children: examination of the role of caregiver health beliefs. AIDS Care 2001;13:617–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eley B, Nuttall J, Davies MA, et al. Initial experience of a public sector antiretroviral treatment programme for HIV-infected children and their infected parents. S Afr Med J 2004;94:643–646 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Dyke RB, Lee S, Johnson GM, et al. Reported adherence as a determinant of response to highly active antiretroviral therapy in children who have human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pediatrics 2002;109(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/109/4/e61. Accessed October 21, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams PL, Storm D, Montepiedra G, et al. Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral medications in children and adolescents with HIV infection. Pediatrics 2006;118(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/118/6/e1745. Accessed October 21, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group. PACTG Pediatric Adherence Questionnaire, Modules 1 & 2 Available at: www.fstrf.org/qol/peds/pedadhere.html. Accessed October 1, 2007.

- 11.Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG Adherence Instruments. AIDS Care 2000; 12: 255–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gortmaker SL, Lenderking WR, Clark C, et al. Development and use of a pediatric quality of life questionnaire in AIDS clinical trials: Reliability and validity of the General Health Assessment for Children (GHAC). In: Dennis Drotar, editor. Assessing pediatric health-related quality of life and functional status: Implications for research, practice and policy Mahwah, New Jersey, Lawrence Feldbaum, Associates, 1998; 219–235 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Storm DS, Boland MG, Gortmaker SL, et al. Protease inhibitor combination therapy, severity of illness, and quality of life among children with perinatally acquired HIV-1 infection. Pediatrics 2005;115(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/115/2/e173. Accessed October 21, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee GM, Gortmaker SL, McIntosh K, Hughes MD, Oleske JM, for the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 219C Team. Quality of life in HIV-infected children. Pediatrics 2006; 117: 273–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson BH, Auslander WF, Jung KC, Miller JP, Santiago JV Assessing family sharing of diabetes responsibilities. J Pediatr Psychol 1990;5: 477–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berg KM, Arnsten JH. Practical and conceptual challenges in measuring antiretroviral adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006; 43 (Suppl 1): S79–S87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farley J, Hines S, Musk A, Ferrus S, Tepper V. Assessment of adherence to antiviral therapy in HIV-infected children using the Medication Event Monitoring System, pharmacy refill, provider assessment, caregiver self-report, and appointment keeping. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2003;33:211–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson SB. Chronic disease of childhood: Assessing compliance with complex medical regimens. In: Krasnegor MA, Epstein L, Johnson SB, Yaffe SJ, eds. Developmental aspects of health compliance behavior Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1993:15–184 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiener L, Riekert K, Ryder C, Wood LV. Assessing medication adherence in adolescents with HIV when electronic monitoring is not feasible. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2004;18:527–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marhefka SL, Tepper VJ, Farley J et al. Brief report: assessing adherence to pediatric antiretroviral regimens using the 24-hour recall interview. J Pediatr Psychol 2006; 31:989–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Podsadecki TJ, Vrijens BC, Tousset EP. White coat compliance patterns make therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) a potentially unreliable tool for assessing long-term drug exposure. Presented at: 13th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, 2006; Denver, CO. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reddington C, Cohen J, Baldillo A, et al. Adherence to medication regimens among children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2000;19:1148–1153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibb DM, Goodall RL, Giacomet V, et al. Adherence to prescribed antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children in the PENTA 5 trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2003;22:56–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marhefka SL, Farley JJ, Rodriguez JR, et al. Clinical assessment of medication adherence among HIV-infected children: examination of the Treatment Interview Protocol (TIP). AIDS Care 2004;16:323–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dolezal C, Mellins C, Brackis-Cott E, Abrams E. The reliability of reports of medical adherence from children with HIV and their adult caregivers. J Pediatr Psychol 2003; 28:355–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mellins CA, Backis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Abrams EJ. The role of psychosocial and family factors in adherence to antiretroviral treatment in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004; 23: 1035–1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin S, Elliott-Desorbo DK, Wolters PL, et al. Patient, Caregiver and Regimen Characteristics Associated With Adherence to Highly Active Antiretroviral Pediatr Infect Dis J 2007;26(1):61–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nieuwkerk PT and Oort FJ. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection and virologic treatment response: A meta-analysis. Jnl Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005; 38:445–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]